Gauging the Media Discourse and the Roots of Islamophobia Awareness in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Origins and Definition of Islamophobia

2.2. Spanish Media Discourses on Islam and Muslims

3. Hypotheses and RQs

4. Materials and Methods

5. Findings

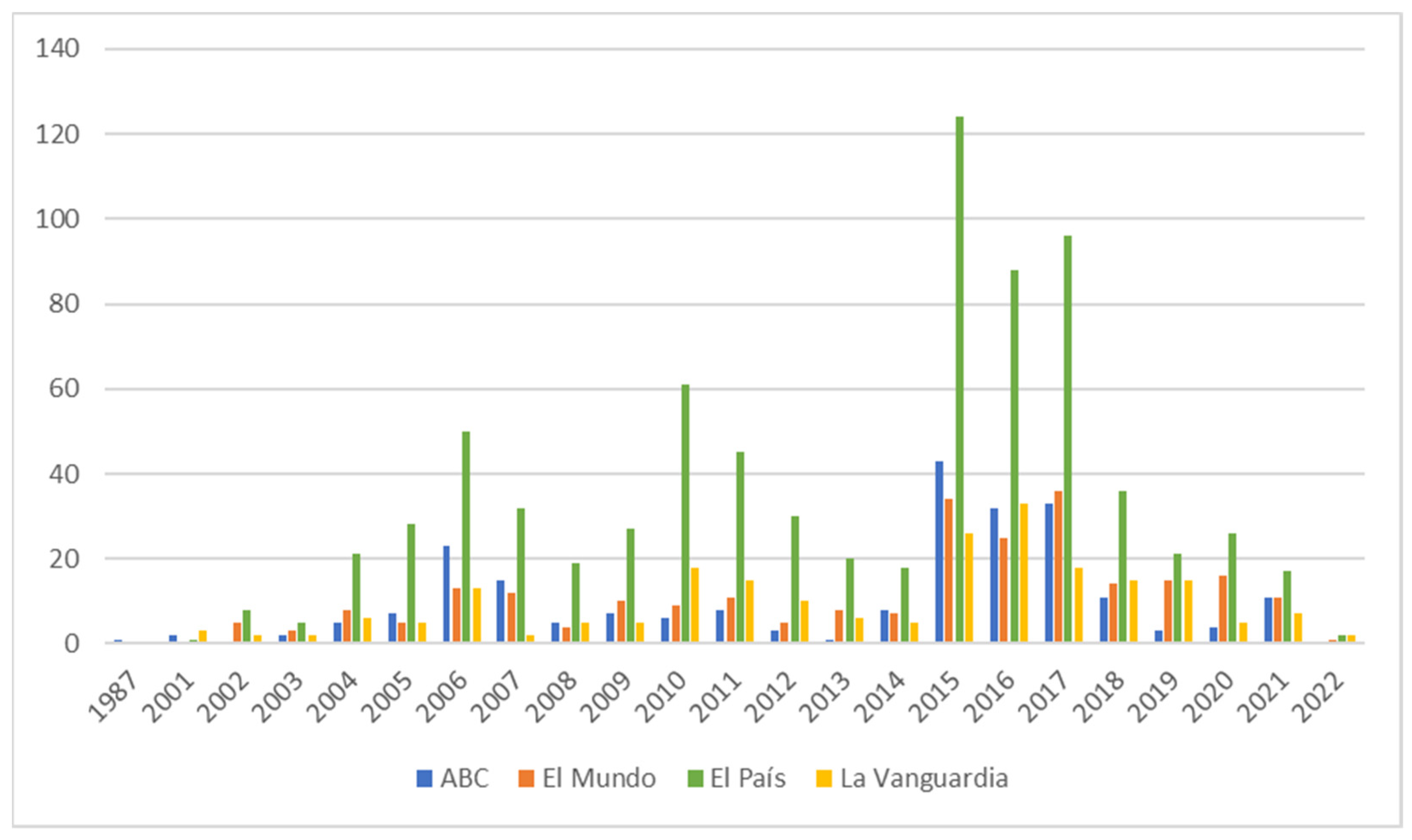

5.1. Media Attention to Islamophobia

5.2. Timeline

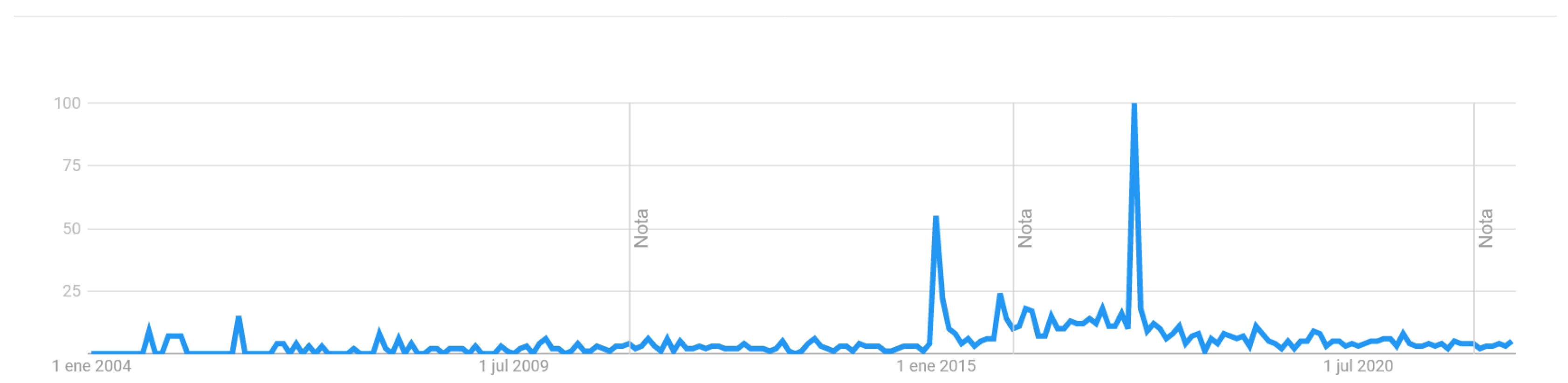

5.3. Public Interest in Islamophobia

5.4. What the Legacy Newspapers Tell Us about Islamophobia and Related Terms

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aatar, Fátima, Oumaya Amghar, Santiago Bonilla, Mónica Carrión, and Elisabetta Ciuccarelli. 2021. Proximidad, clave para un mejor periodismo inclusivo. Informe 2020. Barcelona: Observatorio de la Islamofobia en los Medios. Available online: https://www.iemed.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ObservatorioIslamofobia_2020.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Ainz-Galende, Alexandra, Antonia Lozano-Díaz, and Juan S. Fernández-Prados. 2021. I Am Niqabi: From Existential Unease to Cyber-Fundamentalism. Societies 11: 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainz-Galende, Alexandra, and Rubén Rodríguez-Puertas. 2021. Islam Is Not Bad, Muslims Are: I’m Done with Islam. Religions 12: 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Chris. 2020. Reconfiguring Islamophobia: A Radical Rethinking of a Contested Concept. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allievi, Stefano. 2022. Islamic knowledge in Europe. In Routledge Handbook of Islam in the West. Edited by Roberto Tottoli. London: Routledge, pp. 301–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ameli, Saied Reza, and Arzu Merali. 2019. A multidimensional model of understanding Islamophobia: A comparative practical analysis of the US, Canada, UK and France. In The Routledge International Handbook of Islamophobia. Edited by Irene Zempi and Imran Awan. London: Routledge, pp. 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio-Gómez, Rosa. 2020. Resultados Encuesta Sobre Intolerancia y Discriminación Hacia las Personas Musulmanas en España. Madrid: Observatorio Español del Racismo y la Xenofobia. Available online: https://www.inclusion.gob.es/oberaxe/ficheros/documentos/Resultado_encuesta_musulmanes_11112020.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Arcila-Calderón, Carlos, David Blanco-Herrero, and María Belén Valdez-Apolo. 2020. Rechazo y discurso de odio en Twitter: Análisis de contenido de los tuits sobre migrantes y refugiados en español. Reis: Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 172: 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armañanzas, Emiliana, and Javier Díaz-Noci. 1996. Periodismo y Argumentación: Géneros de Opinión. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, Imran. 2014. Islamophobia and Twitter: A typology of online hate against Muslims on social media. Policy & Internet 6: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangstad, Sindre. 2022. Western Islamophobia: The origins of a concept. In Routledge Handbook of Islam in the West. Edited by Roberto Tottoli. London: Routledge, pp. 463–75. [Google Scholar]

- Barba del Horno, Mikel. 2021. Los menores extranjeros no acompañados como problema: Sistema de intervención y construcción social de una alteridad extrema. Aposta. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 91: 47–66. Available online: http://apostadigital.com/revistav3/hemeroteca/mikelbarba2.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Bayrakli, Enes, and Farid Hafez. 2021. European Islamophobia Report 2020. Vienna: Leopold Weiss Institute. Available online: https://www.islamophobiareport.com/EIR_2020.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Beck, Laura. 2012. ‘Moros en la costa’: Islam in Spanish visual and media culture. Historia Actual Online 29: 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, David Andreas, Marko Valenta, and Zan Strabac. 2021. A comparative analysis of changes in anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim attitudes in Europe: 1990–2017. Comparative Migration Studies 9: 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Mike, Inaki Garcia-Blanco, and Kerry Moore. 2015. Press Coverage of the Refugee and Migrant Crisis in the EU: A Content Analysis of five European Countries. Cardiff: School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Boll, Jessica R. 2020. Selling Spain: Tourism, Tensions, and Islam in Iberia. Journal of Intercultural Communication 53: 42–55. Available online: http://immi.se/oldwebsite/20-2-53/PDFs/Boll-SellingSpain-53-4.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bosilkov, Ivo, and Dimitra Drakaki. 2018. Victims or intruders? Framing the migrant crisis in Greece and Macedonia. Journal of Migration and Identity Studies 12: 26–45. Available online: http://www.e-migration.ro/jims/Vol12_No1_2018/JIMS_Vol12_No1_2018_pp_26_45_BOSILKOV.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Bracke, Sarah, and Luis Manuel Hernández-Aguilar. 2021. Thinking Europe’s ‘Muslim Question’: On Trojan Horses and the Problematization of Muslims. Critical Research on Religion 10: 200–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-López, Fernando. 2011. Towards a definition of Islamophobia: Approximations of the early twentieth century. Ethnic and Racial Studies 34: 556–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, Solène, and Claire Cosquer. 2022. Sociologie de la Race. Malakoff: Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Barbero, Carla, and Ángel Carrasco-Campos. 2020. Portraits of Muslim women in the Spanish press: The burkini and burqa ban affair. Communication & Society 33: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Barbero, Carla, and Pilar Sánchez-García. 2018. Islamofobia en la prensa escrita: De la sección de opinión a la opinión pública. Historia y Comunicación Social 23: 509–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canel, María José. 1999. El País, ABC y El Mundo. Tres manchetas, tres enfoques de las noticias. Zer 6: 97–117. Available online: https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/Zer/article/view/17383/15162 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Cervi, Laura, Santiago Tejedor, and Monica Gracia. 2021. What Kind of Islamophobia? Representation of Muslims and Islam in Italian and Spanish Media. Religions 12: 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Jennifer E. 2022. ‘It’s Not a Race, It’s a Religion’: Denial of Anti-Muslim Racism in Online Discourses. Social Sciences 11: 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civila, Sabina, Luis M. Romero-Rodríguez, and Amparo Civila. 2020. The Demonization of Islam through Social Media: A Case Study of #Stopislam in Instagram. Publications 8: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, Alfonso, and Leen d’Haenens. 2020. The construction of the Arab-Islamic issue in foreign news: Spanish newspaper coverage of the Egyptian revolution. Communications 45: 765–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral, Alfonso, Cayetano Fernández, and Antonio Prieto-Andrés. 2023. Islamophobia and Far-Right Parties in Spain: The Vox discourse on Twitter. In Islamophobia as a Form of Radicalisation: Perspectives on Media, Academia and Socio-Political Scapes from Europe and Canada. Edited by Abdelwahed Mekki-Berrada and Leen d’Haenens. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 161–76. [Google Scholar]

- Corral, Alfonso, Cayetano Fernández, and Carmela García. 2020. ‘Framing’ e islamofobia. La cobertura de la revolución egipcia en la prensa española de referencia (2011–2013). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 77: 373–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, Adela. 2017. Aporofobia, el rechazo al pobre: Un desafío para la democracia. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck, David, Stefan Mertens, and Leen d’Haenens. 2022a. Cross-Country Comparisons of the Media Impact on Anti-Immigrant Attitudes. Leuven: KU Leuven, HumMingBird Project 870661–H2020. Available online: https://hummingbird-h2020.eu/images/projectoutput/wp7-3.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- De Coninck, David, Willem Joris, María Duque, Seth J. Schwartz, and Leen d’Haenens. 2022b. Comparative perspectives on the link between news media consumption and attitudes towards immigrants: Evidence from Europe, the United States, and Colombia. International Journal of Communication 16: 4380–403. Available online: https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/download/19641/3889 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Durán, Rafael. 2019. El encuadre del islam y los musulmanes: La cobertura periodística en España. Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos 16: 156–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, Rafael. 2020. Análisis experimental de efectos. Medios y actitudes hacia lo islámico. Revista de Estudios Políticos 190: 165–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejiofor, Promise Frank. 2023. Decolonising Islamophobia. Ethnic and Racial Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, Farah, and Omar Khan. 2017. Islamophobia: Still a Challenge for Us All. London: Runnymede Trust. Available online: https://assets.website-files.com/61488f992b58e687f1108c7c/61bcd30e26cca7688f7a5808_Islamophobia%20Report%202018%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Fernández, Cayetano, and Alfonso Corral. 2016. La representación mediática del inmigrante magrebí durante la crisis económica (2010–2011). Migraciones Internacionales 8: 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Benumeya, Daniel. 2021. El racismo y la islamofobia en el mercado discursivo de la izquierda española. Política y Sociedad 58: 70118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Benumeya, Daniel. 2023. The Consent of the Oppressed: An Analysis of Internalized Racism and Islamophobia among Muslims in Spain. Sociological Perspectives, OnlineFirst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Alcantud, José Antonio. 2002. Lo moro. Las Lógicas de la Derrota y la Formación del Estereotipo Islámico. Barcelona: Anthropos. [Google Scholar]

- González-Baquero, William, Javier J. Amores, and Carlos Arcila-Calderón. 2023. The Conversation around Islam on Twitter: Topic Modeling and Sentiment Analysis of Tweets about the Muslim Community in Spain since 2015. Religions 14: 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2012. The Multiple Faces of Islamophobia. Islamophobia Studies Journal 1: 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, Kai. 2016. Discurso islamófobo en los medios de comunicación. Afkar/Ideas 50: 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hajjat, Abdellali, and Marwan Mohammed. 2023. Islamophobia in France: The Construction of the “Muslim Problem”. Athens: The University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Fred. 1999. ‘Islamophobia’ reconsidered. Ethnic and Racial Studies 22: 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Aguilar, Luis Manuel. 2023. Islamophobia in Germany, Still a Debate? In Islamophobia as a Form of Radicalisation: Perspectives on Media, Academia and Socio-Political Scapes from Europe and Canada. Edited by Abdelwahed Mekki-Berrada and Leen d’Haenens. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Khader, Bichara. 2016. Reflexiones sobre la islamofobia ‘ordinaria’. Afkar/Ideas 50: 16–18. Available online: https://www.iemed.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Reflexiones-sobre-la-islamofobia-%E2%80%98ordinaria.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Lean, Nathan C. 2019. The debate over the utility and precision of the term “Islamophobia”. In The Routledge International Handbook of Islamophobia. Edited by Irene Zempi and Imran Awan. London: Routledge, pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley-Highfield, Mark. 2022. Islam in Mexico and Central America. In Routledge Handbook of Islam in the West. Edited by Roberto Tottoli. London: Routledge, pp. 167–83. [Google Scholar]

- López, Pablo, Miguel Otero, Miquel Pardo, and Miguel Vicente. 2010. La imagen del Mundo Árabe y Musulmán en la Prensa Española. Sevilla: Fundación Tres Culturas. Available online: http://tresculturas.org/tresculturas/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Informe-CICAM-1.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- López-Bargados, Alberto. 2016. La amenaza yihadista en España: Viejos y nuevos orientalismos. Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos 21: 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mamdani, Mahmood. 2004. Good Muslim, Bad Muslim. America, the Cold War and the Roots of Terror. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Corrales, Eloy. 2004. Maurofobia/islamofobia y maurofilia/islamofilia en la España del siglo XXI. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals 66–67: 39–51. Available online: https://www.cidob.org/es/content/download/58347/1515088/version/1/file/martin_cast.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Martínez-Lirola, María. 2022. Critical analysis of the main discourses of the Spanish press about the rescue of the ship Aquarius. Communication & Society 35: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Muñoz, Gema. 2007. Musulmanes en Europa, entre Islam e Islamofobia. In Musulmanes en la Unión Europea: Discriminación e Islamofobia. Edited by Casa Árabe-Instituto Internacional de Estudios Árabes y del Mundo Musulmán. Madrid: Casa Árabe, pp. 7–9. Available online: https://www.inclusion.gob.es/oberaxe/ficheros/documentos/MusulmanesUE_DiscriminacionIslamofobia.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Martín-Muñoz, Gema. 2010. Unconscious Islamophobia. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 8: 21–28. Available online: https://www.okcir.com/product/journal-article-unconscious-islamophobia-by-gema-martin-munoz/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Massoumi, Narzanin, Thomas Mills, and David Miller. 2017. What Is Islamophobia? Racism, Social Movements and the State. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo-Dieste, José Luis. 2017. “Moros Vienen”. Historia y Política de un Estereotipo. Melilla: Instituto de las Culturas Ciudad de Melilla. [Google Scholar]

- Meer, Nasar, and Tariq Modood. 2019. Islamophobia as the racialisation of Muslims. In The Routledge International Handbook of Islamophobia. Edited by Irene Zempi and Imran Awan. London: Routledge, pp. 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mekki-Berrada, Abdelwahed. 2018. Femmes et subjectivations musulmanes: Prolégomènes. Anthropologie et Sociétés 42: 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekki-Berrada, Abdelwahed, and Leen d’Haenens. 2023. From Media and Pseudo-Scholarly Islamophobia in Post 9/11 Moral Panic to ‘Meta-Solidarity’. In Islamophobia as a Form of Radicalisation: Perspectives on Media, Academia and Socio-Political Scapes from Europe and Canada. Edited by Abdelwahed Mekki-Berrada and Leen d’Haenens. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 247–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Interior. 2021. Informe Sobre la Evolución de los Delitos de odio en España. Madrid: Ministerio del Interior. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/pdf/archivos-y-documentacion/documentacion-y-publicaciones/publicaciones-descargables/publicaciones-periodicas/informe-sobre-la-violencia-contra-la-mujer/Informe_evolucion_delitos_odio_Espana_2020_126200207.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Mohamed-Osman, Mohamed Nawab. 2019. Understanding Islamophobia in Southeast Asia. In The Routledge International Handbook of Islamophobia. Edited by Irene Zempi and Imran Awan. London: Routledge, pp. 286–98. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Espinosa, Pastora. 2000. Los géneros periodísticos informativos en la actualidad internacional. Ámbitos 5: 169–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mercado, José Manuel. 2021. Framing the Afghanistan war in Spanish headlines: An analysis with supervised learning algorithms. IC-Revista Científica de Información y Comunicación 18: 351–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, George, and Scott Poynting. 2012. Global Islamophobia Muslims and Moral Panic in the West. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Alcaraz, Antonia. 2017. “Los malos a mí no me llaman por mi nombre, me dicen moro todo el día”: Una aproximación etnográfica sobre alteridad e identidad en alumnado inmigrante musulmán. EMPIRIA. Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales 38: 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olmos-Alcaraz, Antonia, and Malia Politzer. 2020. ’Dibujando islamofobia’: Islam y prensa en España a propósito un análisis de los atentados a Charlie Hebdo. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico 26: 253–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Alcaraz, Antonia, and Malia Politzer. 2022. Racismo, islamofobia y framing: Los atentados a Charlie Hebdo en la prensa española. Tonos Digital. 42. Available online: http://www.tonosdigital.es/ojs/index.php/tonos/article/view/2949/1296 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Orduña-Malea, Enrique. 2019. Google Trends: Analítica de búsquedas al servicio del investigador, del profesional y del curioso. Anuario ThinkEPI 13: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahib, Mohammed. 2022. La construcción del otro y de la inmigración ilegal en España. Población y Desarrollo 55: 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouassini, Anwar. 2021. The silent inquisition: Islamophobic microaggressions and Spanish Moroccan identity negotiations in contemporary Madrid. Social Compass 69: 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2019. European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/10/Pew-Research-Center-Value-of-Europe-report-FINAL-UPDATED.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Piquer-Martí, Sara. 2015. La islamofobia en la prensa escrita española: Aproximación al discurso periodístico de El País y La Razón. Dirāsāt Hispānicas 2: 137–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, Junaid. 2007. The Story of Islamophobia. Souls 9: 148–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, Ramón. 2000. Medios de Comunicación y Poder en España: Prensa, Radio, Televisión y Mundo Editorial. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Rodinson, Maxime. 1989. La fascinación del Islam. Madrid: Ediciones Júcar. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo, Pedro, Laura Amate, Houssien El Ourriachi, Pilar Garrido, and Lurdes Vidal. 2021. Islam, Personas Musulmanas y Periodismo: Una Guía para Medios de Comunicación. Madrid: Fundación Al Fanar para el Conocimiento Árabe. Available online: https://www.fundacionalfanar.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Islam-personas-musulmanas-y-periodismo.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Rosón-Lorente, Javier. 2012. Discrepancias en torno al uso del término islamofobia. In La Islamofobia a Debate: La Genealogía del Miedo al Islam y la Construcción de los Discursos Antiislámicos. Edited by Gema Martín-Muñoz and Ramón Grosfoguel. Madrid: Casa Árabe, pp. 167–89. [Google Scholar]

- Runnymede Trust. 1997. Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All. London: Runnymede Trust. Available online: https://assets.website-files.com/61488f992b58e687f1108c7c/617bfd6cf1456219c2c4bc5c_islamophobia.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Sahagún, Felipe. 2018. La islamofobia en los medios españoles. Cuadernos de Periodistas 36: 69–82. Available online: https://www.cuadernosdeperiodistas.com/la-islamofobia-en-los-medios-espanoles/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward W. 1985. Orientalism Reconsidered. Cultural Critique 1: 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyid, Salman. 2014. A measure of Islamophobia. Islamophobia Studies Journal 2: 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyid, Salman. 2018a. Islamophobia and the Europeanness of the other Europe. Patterns of Prejudice 52: 420–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyid, Salman. 2018b. Topographies of Hate: Islamophobia in Cyberia. Journal of Cyber-Space Studies 2: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealy, Thomas. 2021. Islamophobia: With or without Islam? Religions 12: 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavkhelidze, Tatia. 2021. Historical Origins of European Islamophobia: The Nexus of Islamist Terrorism, Colonialism and the Holy Wars Reconsidered. Journal of the Contemporary Study of Islam 2: 142–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Delgado, Virtudes, and Ángeles Ramírez-Fernández. 2018. La antropología de los contextos musulmanes desde España: Inmigración, islamización e islamofobia. Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares 73: 295–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unión de Comunidades Islámicas de España. 2022. Estudio demográfico de la población musulmana. Madrid: Observatorio Andalusí. Available online: https://ucide.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/estademograf21-Espanol.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Valenzuela, Javier. 2013. ¿Y si resulta que los árabes también son humanos? In Hello Everybody. Imágenes de Oriente Medio. Joris Luyendijk. Barcelona: Península, pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Van-Gorp, Baldwin. 2005. Where is the frame? Victims and intruders in the Belgian press coverage of the asylum issue. European Journal of Communication 20: 484–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidgen, Bertie, Taha Yasseri, and Helen Margetts. 2022. Islamophobes are not all the same! A study of far-right actors on Twitter. Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism 17: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, Farshad. 2014. La cultura de la posmodernidad y la Primavera Árabe. In El Periodismo en las Transiciones Políticas. De la Revolución Portuguesa y la Transición Española a la Primavera Árabe. Edited by Jaume Guillamet and Francesc Salgado. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, pp. 323–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Medina, Rocío, Pilar Garrido-Clemente, and Jorge Sánchez-Martínez. 2021. Análisis del discurso de odio sobre la islamofobia en Twitter y su repercusión social en el caso de la campaña «Quítale las etiquetas al velo». Anàlisi: Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura 65: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Barrero, Ricard. 2006. The Muslim Community and Spanish Tradition: Maurophobia as a Fact and Impartiality as a Desideratum. In Multiculturalism, Muslims and Citizenship: A European Approach. Edited by Tariq Modood, Anna Triandafyllidou and Ricard Zapata-Barrero. London: Routledge, pp. 143–62. [Google Scholar]

| Terms | Thesaurus Result Score |

|---|---|

| Racismo | 0.23 |

| Terrorismo | 0.20 |

| Violencia | 0.19 |

| Odio | 0.18 |

| Antisemitismo | 0.17 |

| Xenofobia | 0.16 |

| Guerra | 0.13 |

| Discriminación; islam | 0.12 |

| Delito; ataque | 0.11 |

| Intolerancia; extremismo; musulmán; sentimiento | 0.10 |

| Atentado; debate; política; exclusión; derecha | 0.09 |

| Amenaza; agresión; problema; islamismo; presencia | 0.08 |

| Category | Terms | Combined Frequency in 3 Right-Wing Newspapers | Frequency in Left-Wing Newspaper | Share of the Frequencies in Left-Wing Newspaper (in %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimisation | Odio | 436 | 361 | 45 |

| Discriminación | 157 | 154 | 50 | |

| Racismo | 272 | 281 | 51 | |

| Antisemitismo | 169 | 191 | 53 | |

| Intolerancia | 84 | 112 | 57 | |

| Xenofobia | 123 | 157 | 56 | |

| Exclusión | 37 | 50 | 57 | |

| Threat | Guerra | 665 | 421 | 39 |

| Ataque | 432 | 346 | 44 | |

| Amenaza | 352 | 286 | 45 | |

| Atentado | 699 | 595 | 46 | |

| Agresión | 104 | 94 | 47 | |

| Islamismo | 157 | 153 | 49 | |

| Violencia | 322 | 339 | 51 | |

| Delito | 175 | 184 | 51 | |

| Terrorismo | 533 | 594 | 53 | |

| Politics | Política | 532 | 431 | 45 |

| Debate | 326 | 299 | 48 | |

| Derecha | 380 | 394 | 51 | |

| Extremismo | 68 | 72 | 51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corral, A.; De Coninck, D.; Mertens, S.; d’Haenens, L. Gauging the Media Discourse and the Roots of Islamophobia Awareness in Spain. Religions 2023, 14, 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081019

Corral A, De Coninck D, Mertens S, d’Haenens L. Gauging the Media Discourse and the Roots of Islamophobia Awareness in Spain. Religions. 2023; 14(8):1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081019

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorral, Alfonso, David De Coninck, Stefan Mertens, and Leen d’Haenens. 2023. "Gauging the Media Discourse and the Roots of Islamophobia Awareness in Spain" Religions 14, no. 8: 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081019

APA StyleCorral, A., De Coninck, D., Mertens, S., & d’Haenens, L. (2023). Gauging the Media Discourse and the Roots of Islamophobia Awareness in Spain. Religions, 14(8), 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081019