What Is Phenomenological Thomism? Its Principles and an Application: The Anthropological Square

Abstract

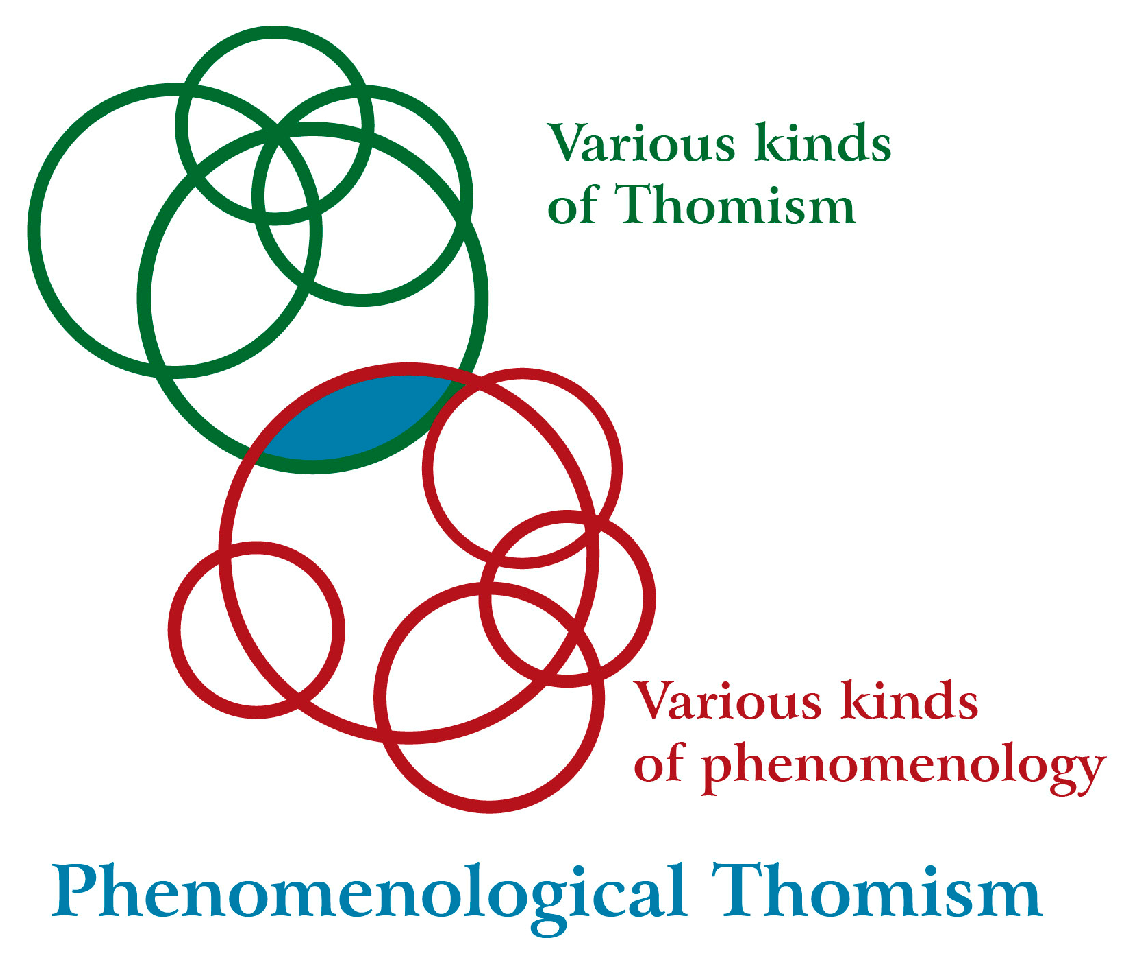

1. Introduction: What Does “Phenomenological Thomism” Refer to?

2. Thomism and Phenomenology

3. Thesis: Phenomenological Thomism as a Sui Generis Category

4. Not-Thomism or Not-Phenomenology

5. An Intermediate View

6. Why Both Phenomenology and Thomism?

7. Key Characteristics of Phenomenological Thomism

- (1)

- Firstly, it draws from the philosophical method or the conclusions of realistic phenomenology and from the Scholastic method, as well as from teachings of Thomas Aquinas, who, in turn, drew on the classical philosophical and theological authorities of his times.

- (2)

- Secondly, in Phenomenological Thomism, this drawing is based the principle of the integrality of knowledge available from various relevant sciences.

- (3)

- Thirdly, Phenomenological Thomism preserves the autonomous right of each discipline to offer its data according to the best method accepted within it. The validity of the method and results of a particular study is to be verified according to the rules accepted by the specialists in the relevant discipline or disciplines, as opposed to one discipline dictating to another which of their methods or results are valid and which are dismissible.

- (4)

- Fourthly, the rule of autonomy pertains specifically to theology with its depositum fidei and certitudo fidei principles, since theology offers unique sets of truths about the world absent from all other academic disciplines. In the case of theology, the principle of autonomy means that its truths are offered as the results achieved by the relevant expert in the field. In recognition of points (1) and (3), a Phenomenological Thomist will—in an attempt to collect data from theology—adhere to the leading authorities of Christianity, today categorised as the Fathers and the Doctors of the Church, as well as the Magisterial documents of the Church. However, when not relevant, theological data need not be implemented into a phenomenological–Thomistic study.

- (5)

- Fifthly, the rule of autonomy does not dismiss the idea of a meta-discipline—philosophy—whose special role is to integrate as well as compare and investigate the premises, conclusions, assumptions, and methods of other disciplines. As such, philosophy plays a unifying and dialogical role among the sciences. In doing so, it returns to its medieval role of aliarum omnium rectrix et regulatrix, a leader or regulator of all other sciences (though not in the sense of dictating what they must claim), and the philosopher, to his duty of ordering knowledge: sapientis est ordinare (Thomas Aquinas, Sententia libri Metaphysicae, prooemium). Clearly, the idea of integrality of knowledge faces the complexity of various monotheistic and polytheistic religions’ narrations about God; nonetheless, in its original, Central European form, Phenomenological Thomism relies on the Catholic theology taught at most academic centres in Europe. In being rectrix et regulatrix aliarum, philosophy—in the form practiced by a Phenomenological Thomist—does not invalidate the premises of theology or any other science but respects their expertise and orders their claims in relation to one another, as was practiced by Edith Stein, such as in relation to the science of evolution and the biblical claims about human creation.

- (6)

- Sixthly, such construed Phenomenological Thomism leads to the amplification of reason (Italian ampliato, German Erweiterung), desired by some leading theologians (Francis 2017; Benedict XVI 2007) and philosophers (Husserl 1954; MacIntyre 2007) of our times. The need for an integral outlook at the sciences has been at the heart of phenomenologists’ concerns, specifically in Husserl’s 1936 work Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie. Phenomenological Thomism continues this tradition of attempting to integrate knowledge available from the various academic disciplines by the application of both the leading methods of phenomenological inquiry (transcendental and eidetic reductions) and the Thomistic approach, yet in dialogue with the outcomes of the relevant sciences, including the exact sciences.

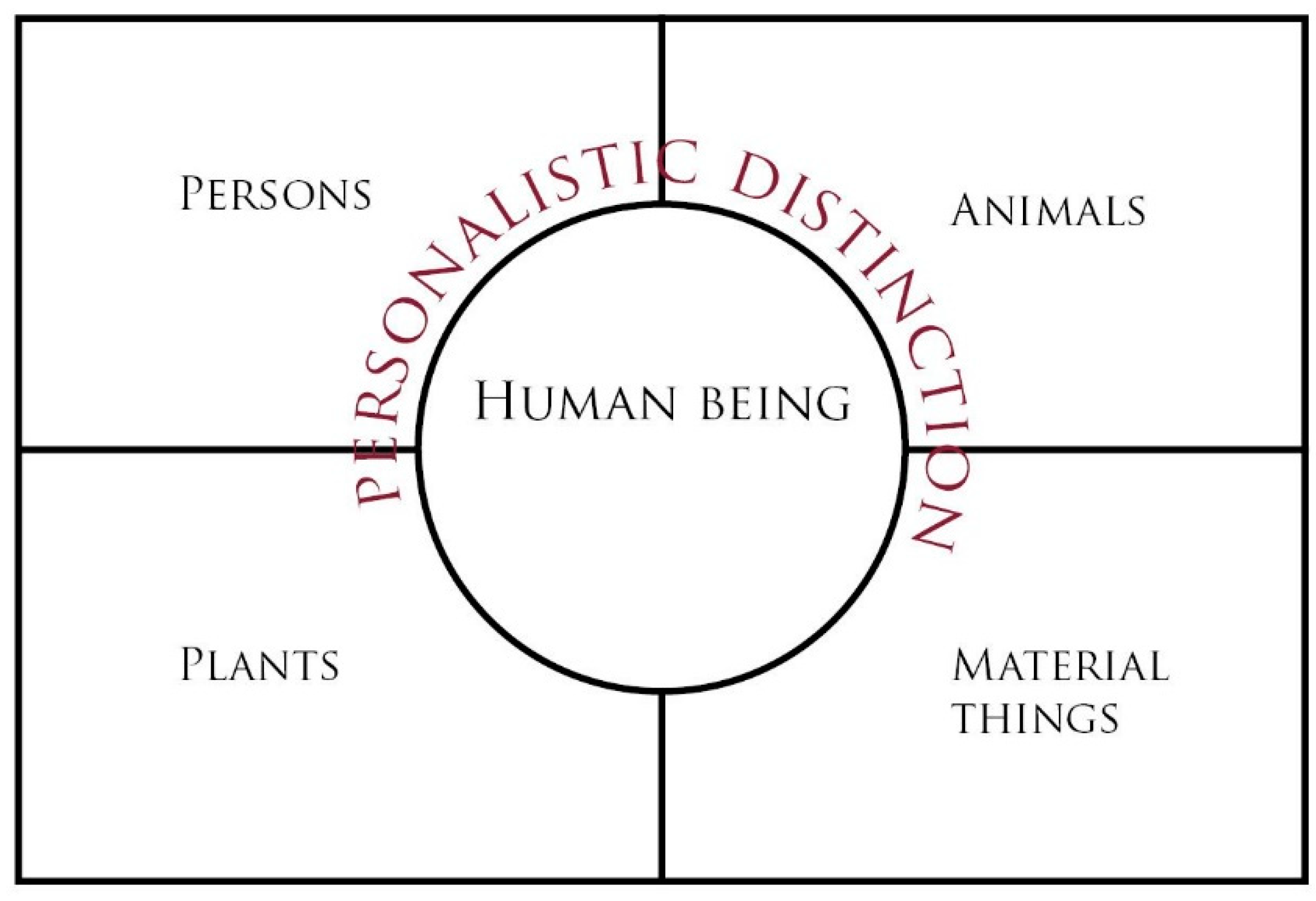

8. Edith Stein’s Application: The Anthropological Square

9. Was Phenomenological Thomism Short-Lived?

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrzejczuk, Artur. 2016. Tomizm fenomenolugizujący Antoniego B. Stępnia. Recenzja. Rocznik Tomistyczny 5: 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Baseheart, Mary Catherine. 1960. The Encounter of Husserl’s Phenomenology and the Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas in Selected Writings of Edith Stein. Unpublished Doctoral thesis, Notre Dame University, Notre Dame, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI. 2007. To the participants in the First European Meeting of University Lecturers. June 23. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2007/june/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20070623_european-univ.html (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Berkman, Joyce Lucy. 2019. Phenomenology and Christian Philosophy: Edith Stein’s Three Turns. Wrocławski Przegląd Teologiczny 27: 201–24. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, Simon. 1994. Oksfordzki Słownik Filozoficzny. Edited by Jan Woleński. Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, pp. 296–97. [Google Scholar]

- Borden-Sharkey, Sarah. 2012. The Meaning of Being in Thomas Aquinas and Edith Stein. In Thomas Aquinas: Teacher and Scholar. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Brent, James. 2023. Natural Theology. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002, 14 April 2023. Available online: https://iep.utm.edu/theo-nat/#H5 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- De Santis, Daniele, Burt C. Hopkins, and Claudio Majolino. 2021. The Routledge Handbook of Phenomenology and Phenomenological Reseach. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Durfee, Harold A. 1983. Ultimate Meaning and Presuppositionless Philosophy. Ultimate Reality and Meaning 6: 224–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis. 2017. Veritatis Gaudium. Proem, 4c. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_constitutions/documents/papa-francesco_costituzione-ap_20171208_veritatis-gaudium.html (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Geiger, Louis-Bertrand. 2022. Fenomenologia i tomizm. In Geiger, “Fenomenologia i tomizm” oraz inne pisma filozoficzne. Translated by D. Radziejowski. Cracow: Societas Vistulana, pp. 67–72. First published 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Gelber, Lucy. 1991. Einleitung der Herausgeber. In Einführung in die Philosophie. Edited by Lucy Gelber and Linssen Michael. Freiburg: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Gerl-Falkovitz, Hanna Barbara. 2000. Einleitung. In Selbstbildnis in Briefen. Edited by Edith Stein. Freiburg im Breisgau: Maria Amata Neyer, Herder, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, Gerald. 2015. Exemplars and Essences: Thomas Aquinas and Edith Stein. In Intersubjectivity, Humanity, Being: Edith Stein’s Phenomenology and Christian Philosophy. Edited by Mette Lebech and John Haydn Gurmin. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Gogacz, Mieczysław. 1984. Recenzja ‘W kierunku Boga’ w redakcji Bogdana Bejzego i wydaniu w Warszawie w 1982. Studia Philosophiae Christianae 20: 191–92, Translated by the author of the article. [Google Scholar]

- Gricoski, Thomas. 2020. Being Unfolded: Edith Stein on the Meaning of Being. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero van der Meijden, Jadwiga Helena. 2019. Person and Dignity in Edith Stein’s Writings: Investigated in Comparison to the Writings of the Doctors of the Church and the Magisterial Documents of the Catholic Church. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero van der Meijden, Jadwiga Helena. 2020. Symbol tragedii. Kryteria orzekania eminens doctrina w procedurach nadawania tytułu doktora Kościoła a dorobek Edyty Stein. In Dialog o człowieku w drodze do prawdy: Jan Paweł II, Edyta Stein, Roman Ingarden. Wrocław: Wrocławski Wydział Teologiczny, p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, Edmund. 1954. Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, Edmund. 2021. Ideen zu Einer Reinen Phänomenologie und Phänomenologischen Philosophie. Hamburg: Meiner Felix Verlag, p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Ingarden, Roman. 1971. O badaniach filozoficznych Edith Stein. Znak 4: 399, Translated by the author of the article. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul II. 1986. The General Audience of April 16, 1986. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/es/audiences/1986/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_19860416.html (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Kerr, Fergus. 2002. After Aquinas. Versions of Thomism. Oxford, Carlton and Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kunicka, Małgorzata. 2017. Tomistyczno-fenomenologiczna koncepcja personalizmu Karola Wojtyły wobec kryzysu wartości i współczesnych potrzeb edukacyjnych. Kultura—Media—Teologia 30: 174–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lebech, Mette. 2013. Edith Stein’s Thomism. Maynooth Philosophical Papers 7: 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembeck, Karl-Heinz. 1999. Wiara w wiedzy? O aporetycznej strukturze późnej filozofii Edyty Stein. In Tajemnica osoby ludzkiej. Antropologia Edyty Stein. Edited and Translated by Jerzy Machnacz. Wrocław: TUM, pp. 125–40. [Google Scholar]

- Machnacz, Jerzy. 1998. Misja Edyty Stein dla współczesnego człowieka. W Drodze 12: 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Machnacz, Jerzy. 1999. Stanowisko Edyty Stein w sporze wewnątrzfenomenologicznym. In Tajemnica osoby ludzkiej. Antropologia Edyty Stein. Edited by Jerzy Machnacz. Wrocław: TUM, pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Machnacz, Jerzy. 2008. ESGA—Edyty Stein dzieła wszystkie. Rys historyczno-merytoryczny. Wrocławski Przegląd Teologiczny 16: 207–23. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, Alasdair. 2007. Edith Stein. Philosophical Prologue. Lanham and Boulder: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, Dermon, and Joseph Cohen. 2012. The Husserl Dictionary. London and New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Olejniczak, Marek. 2010. Wolność miłości. Ontologia osoby ludzkiej w koncepcjach Edyty Stein i Karola Wojtyły. Tarnów: Fundacja Jana Pawła II, pp. 113–15. [Google Scholar]

- Orzechowski, Wojciech. 2018. Obrona Edyty Stein koncepcji filozofii wobec krytyki Josefa Stallmacha i Karla-Heinza Lembecka. Śląskie Studia Historyczno-Teologiczne 51: 315–28. [Google Scholar]

- Reed-Downing, Teresa. 1990. Husserl’s Presuppositionless Philosophy. Research in Phenomenology 20: 136–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, Paweł. 2023. “Wielka ontologia”. Analiza “Bytu wiecznego a bytu skończonego”. In Pisma Edyty Stein. Studia i Analizy. Edited by Jadwiga Guerrero van der Meijden. Wrocław: Ośrodk Pamięć i Przyszłość, p. 255, forthcoming in September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski, Robert. 2000. Introduction to Phenomenology. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge Univeristiy Press, pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stallmach, Josef. 1999. Dzieło Edyty Stein w polu napięcia między wiedzą i wiarą. In Tajemnica osoby ludzkiej. Antropologia Edyty Stein. Edited and Translated by Jerzy Machnacz. Wrocław: TUM, pp. 113–24. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 1962. Welt und Person. Beitrag zum Christlichen Wahrheitsstreben. Edited by L. Gelber and R. Leuven. Louvain and Freiburg: Herder, pp. ix–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2000. Selbstbildnis in Briefen I. Erster Teil 1916–1933. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2003. Kreuzeswissenschaft. Studie über Johannes vom Kreuz. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2004a. Der Aufbau der Menschlichen Person. Vorlesung zum Philosophischen Anthropologie. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2004b. ESGA 8: Einführung in die Philosophie. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2005a. ESGA 10: Potenz und Akt. Studien zu einer Philosophie des Seins. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2005b. ESGA 15: Was is der Mensch? Theologische Anthropologie. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2005c. Selbstbildnis in Briefen III. Briefe an Roman Ingarden. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder, p. 153, Translated by the author of the article. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2006a. ESGA 11/12: Endliches und ewiges Sein. Versuch eines Aufstiegs zum Sinn des Seins. Anhang: Martin Heideggers Existenzphilosophie. Die Seelenburg. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2006b. ESGA 7: Eine Untersuchung über den Staat. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2008. Zum Problem der Einfühlung. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2010. ESGA 6: Beiträge zur philosophischen Begründung der Psychologie und der Geisteswissenschaften. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2013. ESGA 17: Wege der Gotteserkenntnis. Studie zu Dionysius Areopagita und Übersetzung seiner Werke. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2014a. Was ist Philosophie? Ein Gespräch zwischen Edmund Husserl und Thomas von Aquino. In ‘Freiheit und Gnade’ und weitere Beiträge zu Phänomenologie und Ontologie. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder, pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2014b. Husserls Phänomenologie und die Philosophie des hl. Thomas von Aquino. In ‘Freiheit und Gnade’ und weitere Beiträge zu Phänomenologie und Ontologie. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder, pp. 119–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2014c. Die weltanschauliche Bedeutung der Phänomenologie. In ‘Freiheit und Gnade’ und weitere Beiträge zu Phänomenologie und Ontologie. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder, pp. 143–58. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2014d. Erkenntinis, Wahrheit, Sein. In ‘Freiheit und Gnade’ und weitere Beiträge zu Phänomenologie und Ontologie. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder, pp. 168–75. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Edith. 2014e. Freiheit und Gnade. In ‘Freiheit und Gnade’ und weitere Beiträge zu Phänomenologie und Ontologie. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder, pp. 8–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stepa, Jan. 1933. Des hl. Thomas von Aquino Untersuchungen über dies Wahrheit (Quaestiones disputate de veritate) in deutscher Übertragung von Edith Stein. Band I—Przekład opatrzony objaśnieniami metodą analizy fenomenologicznej. Ruch Filozoficzny 36: 296–97. [Google Scholar]

- Stępień, Antoni B. 1999. Studia i szkoce filozoficzne. Volume 1. Edited by A. Gut and R. Kryński. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Stępień, Antoni B. 2001. Studia i szkoce filozoficzne. Volume 2. Edited by A. Gut and R. Kryński. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Stępień, Antoni B. 2015. Studia i szkoce filozoficzne. Volume 3. Edited by A. Gut and R. Kryński. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Szanto, Thomas, and Dermot Moran. 2020. Edith Stein, “The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy”, Spring 2020 ed. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford: The Metaphysics Research Lab. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/stein/ (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Tatarkiewicz, Władysław. 1933. Postawa estetyczna, literacka i poetycka. SPAU 38: 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Volek, Peter, ed. 2016. Husserl und Thomas von Aquin bei Edith Stein. Nordhausen: Traugott Bautz, pp. 74–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 2002. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G. E. Anscombe. Malden, Oxford and West Sussex: Blackwell, pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtyła, Karol. 1961. Personalizm tomistyczny. Znak 83: 664–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, Dan. 2003. Husserl’s Phenomenology. Cracow: Stanford University Press, pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerrero van der Meijden, J.H. What Is Phenomenological Thomism? Its Principles and an Application: The Anthropological Square. Religions 2023, 14, 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070938

Guerrero van der Meijden JH. What Is Phenomenological Thomism? Its Principles and an Application: The Anthropological Square. Religions. 2023; 14(7):938. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070938

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerrero van der Meijden, Jadwiga Helena. 2023. "What Is Phenomenological Thomism? Its Principles and an Application: The Anthropological Square" Religions 14, no. 7: 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070938

APA StyleGuerrero van der Meijden, J. H. (2023). What Is Phenomenological Thomism? Its Principles and an Application: The Anthropological Square. Religions, 14(7), 938. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070938