Nominatissima urbs Granate: The Cultural Clash between Islam and Christianity after the Capitulation of the Nasrid Kingdom and Its Repercussions on the Arts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Capitulation of Granada and Rome: The Basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, Blessed Amadeo and San Pietro in Montorio

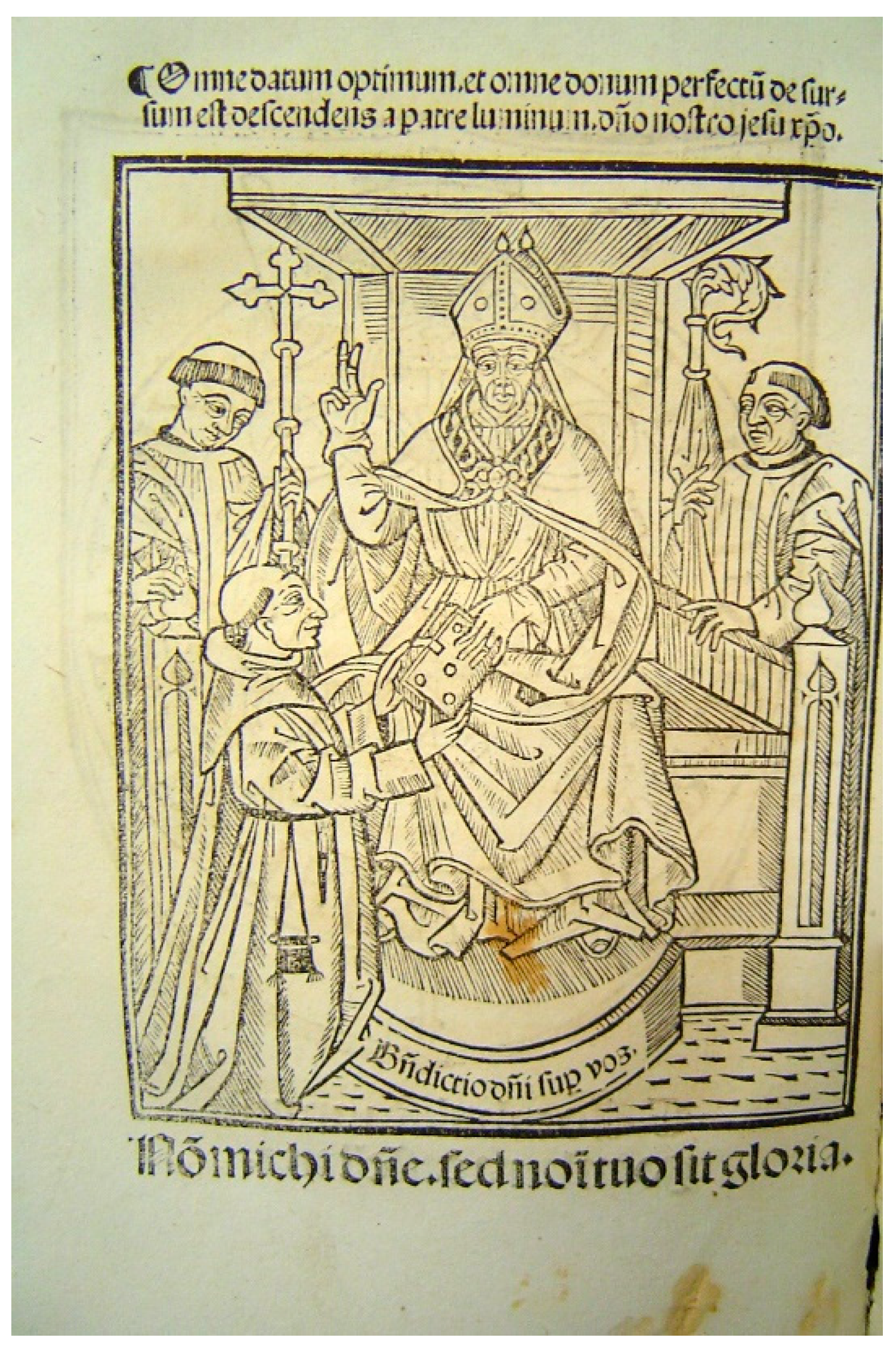

3. Hernando de Talavera, Pedro de Alcala and the Christianization of Granada

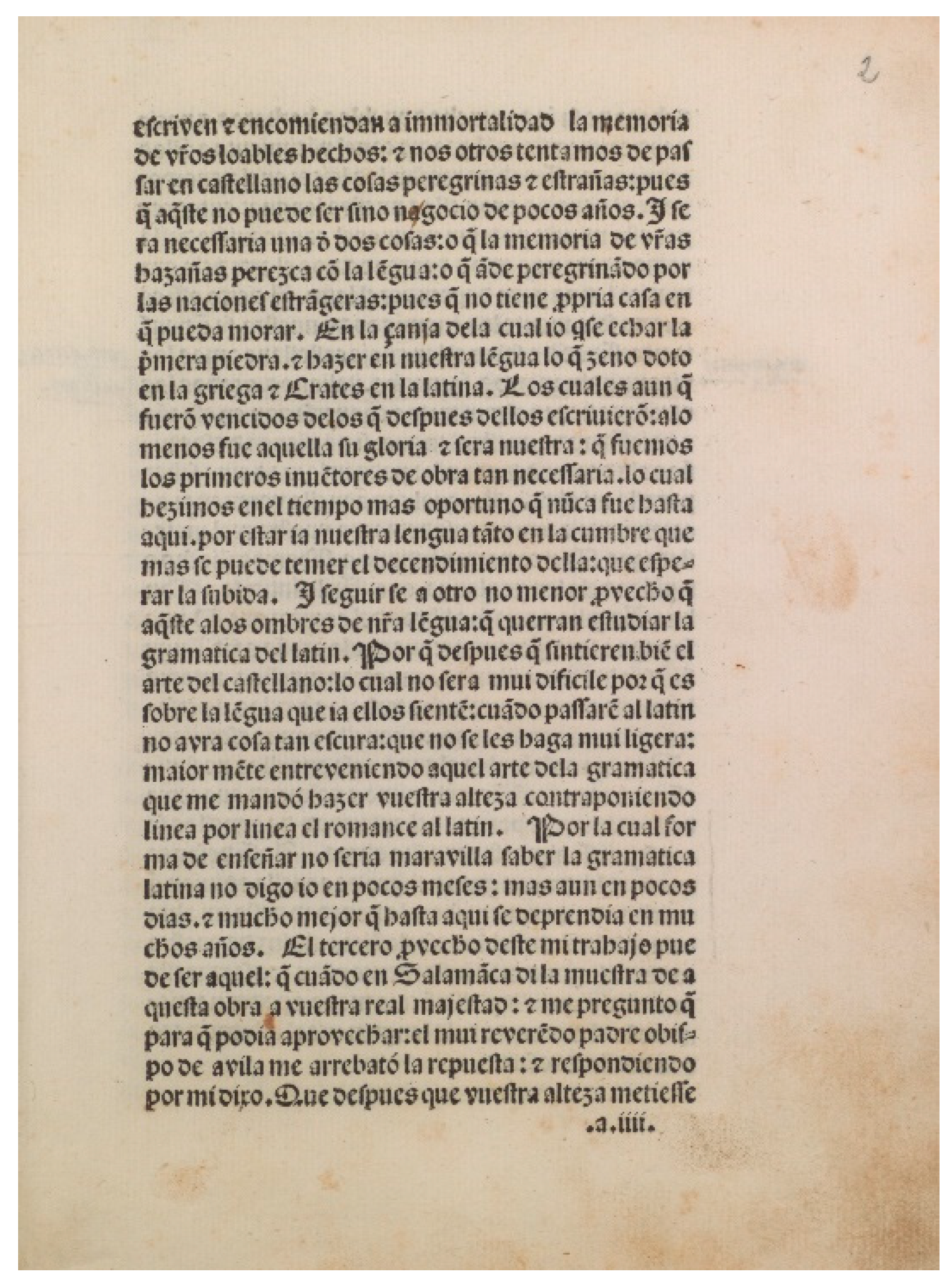

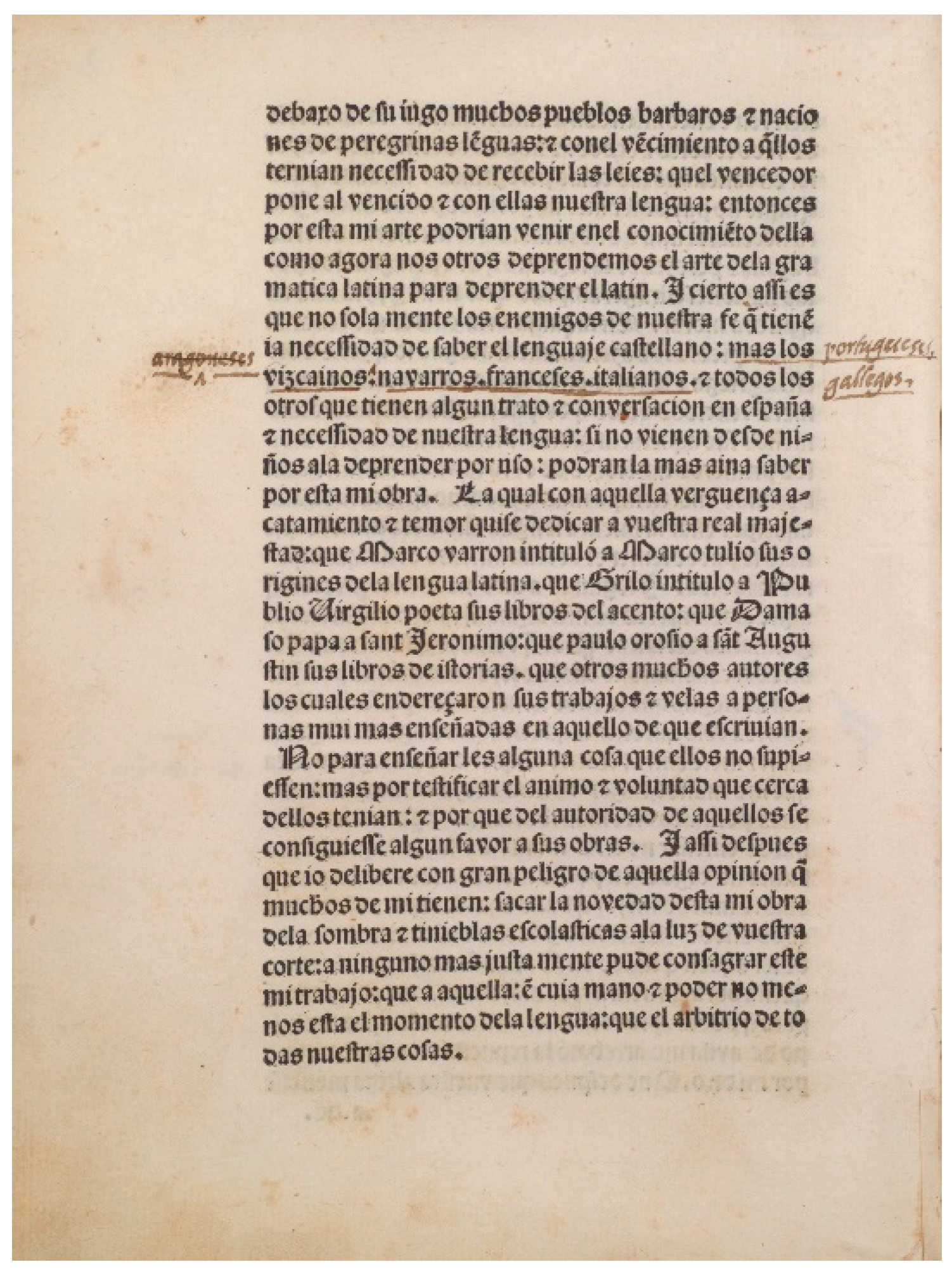

El tercero elemento provecho deste mi trabajo puede ser aquel que, cuando en Salamanca di la muestra de aquesta obra a vuestra real Majestad, y me preguntó que para qué podía aprovechar, el mui reverendo padre Obispo de Ávila me arrebató la respuesta; y, respondiendo por mí, dixo que después de vuestra Alteza metiesse debaxo de su iugo muchos pueblos bárbaros y naciones de peregrinas lenguas, y con el vencimiento aquellos ternían necessidad de recebir las leies qu’el vencedor pone al vencido, y con ellas nuestra lengua, entonces por esta mi arte, podrían venir en el conocimiento della como agora nosotros deprendemos el arte de la gramática latina para deprender el latín.

[The third benefit of this work may be this: when in Salamanca I showed your royal Majesty a sample of this work, you asked of what purpose it could be; the Reverend Father Archbishop of Ávila snatched my response, and answering for me he said that after your Highness has put under her yoke many barbarous peoples and nations of alien languages, with defeat they would have to receive the laws that the conqueror imposes on the on the conquered, and with them our language; then, through this my art they would be able to come into the knowledge of it, as now we depend on the art of Latin grammar to learn Latin].

In the time of Don Hernando de Talavera, the first archbishop that the Catholic Monarchs established in this city, there were religious teachers [alfaquís] and religious leaders [mustis] who received salaries from the archbishop in exchange for providing him with information related to Islam and what went against its precepts. Informed in this way by persons who knew a good deal about Islamic jurisprudence and the books that contained it, the archbishop permitted during his tenure that the zambra be performed with all of this instruments, as it was because of the festive celebrations and weddings of the natives that it was performed. The zambra and its corresponding instruments were also used to honor the Holy Sacraments of the Corpus Christi processions, each trade guild having its own banner (…). And when His Holiness said mass in person there was a zambra in the choir with the clerics. At the moments when the organ would normally be played, because they didn’t have one, they responded with the zambra and its instruments. And some words of Arabic were even spoken in mass: when the archbishop said, Dominus bobispon, people responded with, Ybara figun. I remember this as if it were yesterday, in the year 1502.

4. The Offices of the Capitulation of Granada

¡o que si viese vuestra muy excelente devotion el officio de vuestra dedition de Granada! que no le publico ni comunico hasta que le vea ni ge lo enbio porque no le debe ver sin que yo sea presente para le dar razon de cada cosa y cosa contenida en él.

[If only you, most devout lady, could see the Office of your Capture of Granada! I do not want to publish it nor make it known until I see you, now do I want to send it to you, for you should not see it without me being present so that I can explain to you each and every thing contained in it].

Regis christianissimi atque victoriosissimi: qui velut alter imperator Eracleus, fide catholica flagrans: vexillum sancte crucis in cunctis urbibus regni Granate primum, et hodie in capite earum supra altissima eius urbis Menia: cum honore maximo fecit exaltari. Regis clarissimi, pulcri aspectus et optime fortunati: qui similis inclito Godofredo Gallie comiti, ac primo regi Iherosolimorum: cum magno religionis fervore illustrissimo Iohanne primogenito suo carissimo, ac nobili Hyspaniarum cardinali Petro videlicet de Mendoca: ecclesie presule Tolletane multisque prelatis, ac militarium ordinum magistris: suorumque regnorum ac dominorum non paucis magnatibus, ducibus: marchionibus, et comitibus: aliisque baronibus constipatus: nostram Iherososolimam (sic): urben (sic) videlicet Granatam, sumo ac immortali Deo et corone regni sui: triumphaliter et victoriosissime hodierna die vendicavit.

[To the most Christian and victorious king, who, like the second emperor Heracles, was ardent in the Catholic faith. He raised the banner of the holy cross first in all the cities of the kingdom of Granada, and nowadays, with the greatest honor, at the head of them all, on the most illustrious city of Menia. You, most illustrious, comely, and blessed king, who resembles the renown Godfrey, Count of Gaul and first king of Jerusalem: with great religious fervor, the illustrious John, his most beloved son, and the noble Cardinal of Spain, namely, Pedro de Mendoza, the ecclesiastical prefect of Toledo and of many prelates, and masters of the military orders, and of their kingdoms and lords, which includes not a few magnates, dukes, marquises and counts, and other barons—he seized our Jerusalem, that is, the city of Granada, and claimed it triumphantly and most victoriously on behalf of the immortal God, the crown of his kingdom].

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | On the criticisms and misunderstandings of this cultural panorama: (Gómez Moreno 2015). |

| 2 | Complete transcript at (Besozzi 1750), pp. 76–78. |

| 3 | For a global understanding of the figure of Jerome, we refer to the following studies: (Ladero Quesada 2008; Iannuzzi 2009; Martínez Medina and Biersack 2011; Vega García-Ferrer 2021). |

| 4 | For a general overview of the constitution of the new Church of Granada, especially in its first part (“La Granada que quisieron los Reyes Católicos: ¿Talavera o Cisneros?”), see (García Oro 2004). For the relationship between the two archbishops and their different visions of evangelization, see (Folgado García 2016, 2018). |

| 5 | For an overview of the evangelization process carried out by Talavera, see (Folgado García 2011). For an overview of the evangelization of Granada and its subsequent influence on the evangelization of the Americas: (García-Arenal 1992; García-Arenal and Rodríguez Mediano 2013, pp. 35–94). |

| 6 | For a presentation, see (Framiñán de Miguel 2005). Regarding the date of writing, Nicasio Salvador supports Miguel Ángel Ladero’s theory, as opposed to others, that the letter must have been written between 1500 and 1501: (Salvador Miguel 2016, p. 164, note 101). Although Talavera’s model of evangelization attempted to bring the Christian faith closer to the Islamic population of Granada, this model was no longer common since Cisneros intervened and promoted forced conversion starting in 1499. (Ladero Quesada 2002; Carrasco García 2007). |

| 7 | To understand the importance of the text in the evangelization of Granada: (Folgado García 2014, 2015). |

| 8 | There is another later edition entitled: Arte (…) enmendada y añadida y segundamente imprimida (Art (…) amended and added and secondly printed) (de Alcalá 1506). This copy is in a smaller format than previous ones: its basic content does not vary with respect to the object of our study. Both texts are taken into account in the edition of (de Lagarde 1883). These are, on the other hand, the first printed texts in Arabic, according to Romero’s assessment, (Romero de Lecea 1973, p. 360). |

| 9 | In his biography the Breve suma de la Santa Vida del Religiosísimo y muy Bienaventurado Fr. Hernando de Talavera (Brief sum of the Holy Life of the Most Religious and Blessed Fr. Hernando de Talavera) [=Breve suma] we can read: “Hizo buscar de diversas partes sacerdotes así religiosos como clérigos que supiesen la lengua arábiga para que los enseñasen y oyesen sus confesiones. Trabajaba porque sus clérigos y los de su casa aprendiesen la lengua arábiga y así hizo en su casa pública escuela de arábigo donde la enseñasen y él con toda su ciencia, edad, esperiencia y dignidad se abajaba a aprender y oír los primeros nominativos y así aprendió algunos bocablos pero con muchas ocupaciones no tanto como para predicar como hubiere menester. Pero lo que aprendió no fue tan poco que no supiese decir y entender muchos bocablos que hacía para lo subtancial que quería que creyesen; y porque todos los sacerdotes y sacristanes que residen con los dichos nuevamente convertidos aprendiesen y supiesen dicha lengua hizo hacer arte para la aprender y vocabulario arábigo y hecho mandolo imprimir y mandolos dar a todos los dichos clérigos eclesiásticos. Decía que daría de buena voluntad un ojo por saber la dicha lengua para enseñar a la dicha gente y que tanbién diera una mano sino por no dejar de celebrar” (Jerónimo s/d, ff. 33−34) [“He sought out religious priests as well as clerics who knew the Arabic language from various places in order to instruct them and hear their confessions. He worked so that his clerics and those in their households would learn the Arabic language and so he created in his own residence a public school of Arabic where it would be taught, and he with all his science, age, experience and he was too busy to be able to learn the necessary in order to preach. But what he learned was not so little that he would not be able to come up with and also understand the necessary words in order to convey the gist of what he wanted them to believe; in order that all the priests and sacristans who lived amidst the new converts could learn and know said language, he had an art composed to learn Arabic and acquire vocabulary, and when it was done he had it printed and gave it to all the aforementioned clergyman in the Church. He said that he would willingly give an eye to know said language in order to teach this people and that he would also give a hand if it would not prevent him from celebrating mass”]. The concern for the evangelization of Granada caused Talavera himself to have the Catholic Monarchs seek throughout their kingdoms for priests that could assist with the Christianization of Granada. The monarchs sent letters to various dioceses requesting priests in this way: “Acordamos de escribir a todos los Prelados e Yglesias de nuestro reino, que luego quieran enbiar personas idóneas, que entiendan en ello a lo menos por tiempo de un año” (de Azcona 1958, p. 51) [“We agree to write to all the Prelates and Churches of our kingdom, that they might be willing to send suitable people, that would apply themselves to it at least for a year”]. |

| 10 | Except for the text composed by Juan Maldonado (1485–1554)—Deditio Urbis Granatae—for the Church of Burgos, which is now lost (Castillo-Ferreira 2016, p. 308). |

| 11 | A transcript is available at (Rodríguez Carrajo 1963). |

| 12 | It has been studied and transcribed in (de Azcona 1992). We also refer to the following studies, transcriptions and translations: (Martínez Medina et al. 2003; Vega García-Ferrer 2004). |

| 13 | It is reproduced in (Martínez Medina et al. 2003, pp. 135–266). |

| 14 | Chapter Archives of Santiago, CF 50. We have recently published the text of the Jacobean Office: Folgado García and Ruiz Torres (2020), and in this article, we make, for the first time, a presentation of it. |

| 15 | “ac nobili Hyspaniarum cardinali Petro videlicet de Mendoca: ecclesie presule Tolletane multisque prelatis, ac militarium ordinum magistris: suorumque regnorum ac dominorum non paucis magnatibus, ducibus: marchionibus, et comitibus: aliisque baronibus constipatus” (Folgado García and Ruiz Torres 2020, p. 183). |

| 16 | In Lectio II, after citing the titles of the Catholic Monarchs and stating that he was Innotentio octavo pontifice maximo Petri sedem tenente, mention is made of Cardinal Medoza: Sanctae toletanae Ecclesiae reverendissimo Patre Pedro de Mendoza, tituli Sanctae Crucis in Ierusalem, Presbitero Cardinali Hispaniae. |

References

Primary Source

de Madrid, Jerónimo. s/d. Vida de fray Hernando de Talavera [BNE, ms. 2042, ff. 9-57].de Talavera, Hernando. s/d. In festo deditionis nominatissime urbis Granate. AGS, PR, 25-41.Reço antiguo de la fiesta de Granada. s/d. Capitular Archives of Santiago, CF 50.Secondary Source

- Albalá Pelegrín, Marta. 2017. Humanism and Spanish Literary Patronage at the Roman Curia: The Role of the Cardinal of Santa Croce, Bernardino López de Carvajal (1456–1523). Royal Studies Journal 4: 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadeu, Beato. 2014. Nova Apocalipse. Edited by Domingos Lucas Dias, Sabastião Tavares de Pinho and Arnaldo do Espíritu Santo. Coimbra: Imprena da Universidade de Coimbra. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, Francis. 1885. History of the Reign of King Henry VII. London: Cambridge University Press Warehouse. [Google Scholar]

- Baloup, Daniel, and Raúl González Arévalo, eds. 2017. La guerra de Granada en su contexto internacional. Toulouse: Presses Universitaries du Midi. [Google Scholar]

- Besozzi, Raimondo. 1750. La storia della basilica di Santa Croce in Gerusalemme dedicata alla santità di nostro signore papa Benedetto decimoquarto. Roma: Generoso Salomoni alla Piaza di S. Ignazio. [Google Scholar]

- Breviarium Almae Ecclesiae Compostellanae. 1569. Salamanca: Matthias Gastius, [BNE, R/26294].

- Breviarium Compostellanum. 1497. Lisboa: Nicolás de Sajonia, [BNE, Inc/874].

- Castillo-Ferreira, Mercedes. 2016. Chant, Liturgy and Reform. In Companion to Music in the Age of the Catholic Monarchs. Edited by Tessa Knighton. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 282–322. [Google Scholar]

- Cantatore, Flavia. 2007. San Pietro in Montorio: La Chiesa dei Re Cattolici a Roma. Roma: Quasar. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco García, Gonzalo. 2007. Huellas de la sociedad musulmana granadina: La conversión del Albayzín (1499–1500). En la España Medieval 30: 151–205. [Google Scholar]

- de Alcalá, Pedro. 1505. Vocabulista aravigo en letra castellana. Granada: Juan Varela de Salamanca, [BCT, nº 77.30; BNE, R/16065, R/2158]. [Google Scholar]

- de Alcalá, Pedro. 1506. Arte (…) enmendada y añadida y segundamente imprimida. Granada: Juan Varela de Salamanca, [BNE, R/2306]. [Google Scholar]

- de Azcona, Tarsicio. 1958. El tipo ideal de obispo en la Iglesia española antes de la rebelión luterana. Hispania Sacra 9: 21–64. [Google Scholar]

- de Azcona, Tarsicio. 1992. El Oficio litúrgico de Fr. Hernando de Talavera para celebrar la conquista de Granada. Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia 1: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lagarde, Paul. 1883. Petri Hispani de Lingua Arabica Libri Duo. Gottinga: Aedibus Dieterichianis Arnoldi Hoyer. [Google Scholar]

- de Nebrija, Antonio, and Magalí Armillas-Tiseyra. 2016. On Language and Empire: The Prologue to Grammar of the Castilian Language (1492). Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 131: 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nebrija, Helio Antonio. 1492. Gramática de la Lengua Castellana. Bologna: Library of the Royal College of Spain (Bologna), Cód. 132. [Google Scholar]

- de Talavera, Hernando. 1500. Memorial dirigido a los vecinos del Albaicín. Cámara de Castilla: General Archive of Simancas (=AGS), leg. 8, f. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Córdova Miralles, Álvaro. 2005. Imagen de los Reyes Católicos en la Roma pontificia. En la España Medieval 28: 259–354. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Córdova Miralles, Álvaro. 2014. La emergencia de Fernando el Católico en la Curia papal: Identidad y propaganda de un príncipe aragonés en el espacio italiano (1469–1492). In La imagen de Fernando el Católico en la Historia, la Literatura y el Arte. Edited by Aurora Egido and José Enrique Laplana Gil. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico (CSIC), pp. 29–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Guerrero, Eduardo. 2019. From de “Pastor Angelicus” to the “Rex Magnus”: Messianism and Prophecy during the Iberian Expansion in America. Rivista Storica Italiana 131: 968–91. [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg, Jack. 2005. Bramantes’s Tempietto and the Spanish Crown. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 50: 151–205. [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg, Jack. 2014. Bramantes’s Tempietto, the Roman Renaissance, and the Spanish Crown. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg, Jack. 2020. El legado del Tempietto de Bramante. In Arte y globalización en el mundo hispánico de los siglos XV al XVII. Edited by Manuel Parada López de Corselas and Laura María Palacios Méndez. Granada: Universidad de Granada, pp. 115–35. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado García, Jesús R. 2011. La iniciación cristiana en la conversión de los moriscos granadinos (1492–1507). Iacobvs 29–30: 173–90. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado García, Jesús R. 2014. Las lenguas romances y la evangelización granadina. La aportación de Hernando de Talavera y la liturgia en arábigo de Pedro de Alcalá. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. III. Historia Medieval 27: 229–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado García, Jesús R. 2015. Un intento de diálogo en la Granada Nazarí: El Arte para ligeramente saber la lengua arábiga de Pedro de Alcalá. Hispania Sacra 135: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado García, Jesús R. 2016. Fray Francisco Ximénez de Cisneros y Fray Hernando de Talavera, dos religiosos, dos arzobispos y confesores regios en el Reino de Granada. Toletana 34: 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado García, Jesús R. 2018. La acción de Jiménez de Cisneros y Talavera ante la conversión de los moriscos granadinos. In F. Ximénez de Cisneros. Reforma, conversión y evangelización. Edited by José María Magaz and José María Prim Goicoechea. Madrid: Ediciones de la Universidad Eclesiástica de San Dámaso, pp. 191–227. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado García, Jesús R., and Santiago Ruiz Torres. 2020. Un Oficio Compostelano de la Toma de Granada: In officium diei festi deditiones Granate. In Arte y Globalización en el mundo hispánico de los siglos XV al XVII. Edited by Manuel Parada López de Corselas and Laura Palacios Méndez. Granada: Editorial Universitaria de Granada, pp. 173–91. [Google Scholar]

- Folgado García, Jesús R. 2023. Fray Hernando de Talavera y sus implicaciones en la Guerra de Sucesión, la contienda contra el Reino de Portugal y la Toma de Granada. In Seguridad y fronteras. Liber amicorum Enrique Martínez Ruiz. Edited by István Szászdi León-Borja. Madrid: Marcial Pons, pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Framiñán de Miguel, María Jesús. 2005. Manuales para el adoctrinamiento de los neoconversos en el siglo XVI. Criticón 93: 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- García-Arenal, Mercedes. 1992. Moriscos e indios. Para un estudio comparado de métodos de conquista y evangelización. Chronica Nova 20: 153–75. [Google Scholar]

- García-Arenal, Mercedes. 2014. Granada as a New Jerusalem: The Conversion of a City. In Space and Conversion in Global Perspective. Edited by Giuseppe Marcocci, Aliocha Maldavsky, Wietse de Boer and Ilaria Pavan. Leiden: Brill, pp. 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- García-Arenal, Mercedes, and Fernando Rodríguez Mediano. 2013. The Orient in Spain. Converted Muslims, The Forged Lead Books of Granada, and the Rise of Orientalism. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- García Oro, José. 2004. La Iglesia en el Reino de Granada durante el siglo XVI. Reyes y obispos en la edificación de una nueva Iglesia hispana. Granada: Ave María. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido Atienza, Miguel. 1910. Las capitulaciones para la entrega de Granada. Granada: Paulino Ventura. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Claire. 2018. A Grammar of Conquest: The Spanish and Arabic Reorganization of Granada after 1492. Past and Present 239: 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Claire. 2020. In Good Faith: Arabic Translation and Translators in Early Modern Spain. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Moreno, Ángel. 2015. Burckhardt y la forja de un imaginario. España, la nación sin Renacimiento. eHumanista: Journal of Iberian Studies 29: 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Dorothee. 2009. Instrumentos de propaganda política borgoñona al servicio de los Reyes católicos: Los relieves de la Guerra de Granada en la sillería de la catedral de Toledo. In El intercambio artístico entre los reinos hispanos y las cortes europeas en la Baja Edad Media. Edited by Concepción Cosmen Alonso, María Victoria Herráez Ortega and María Pellón Gómez-Calcerrada. León: Universidad de León, pp. 203–15. [Google Scholar]

- Iannuzzi, Isabella. 2009. El poder de la palabra en el siglo XV: Fray Hernando de Talavera. Salamanca: Junta de Castilla y León. [Google Scholar]

- Ladero Quesada, Miguel Ángel. 2002. Los bautismos de los musulmanes granadinos en 1500. In Actas del VIII Simposio Internacional de Mudejarismo. Teruel: CEM, pp. 481–542. [Google Scholar]

- Ladero Quesada, Miguel Ángel. 2008. Fray Hernando de Talavera en 1492: De la Corte a la Misión. Chronica Nova 34: 249–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro Pulido, Manuel. 2019. El beato Amadeo da Silva Meneses e introducción al Apocalypsis Noua: Redención y escatología en el siglo XV. Revue d’histoire ecclésiastique 114: 686–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Medina, Francisco Javier, and Martín Biersack. 2011. Fray Hernando de Talavera, primer arzobispo de Granada. Hombre de iglesia, estado y letras. Granada: Editorial de la Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Medina, Francisco Javier, Pilar Ramos López, Elisa Varela Rodríguez, and Hermenegildo de la Campa, eds. 2003. Oficio de la Toma de Granada. Granada: Diputación Provincial. [Google Scholar]

- Moroni Romano, Gaetano. 1861. Carvaial Bernardino, Cardinale. In Dizionario di erudizione storico-ecclesiatica. Venezia: Tipografía Emiliana, vol. X, pp. 134–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mujica Pinilla, Ramón. 1992. Ángeles apócrifos en la América Virreinal. Lima: Fondo de Cultura Económica—Instituto de Estudios Tradicionales. [Google Scholar]

- Mujica Pinilla, Ramón. 2007. Apuntes sobre moros y turcos en el imaginario andino virreinal. Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia 16: 169–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez Muley, Francisco. 2007. A Memorandum for the President of the Royal Audiencia and Chancery Court of the City and Kingdom of Granada. Edited by Vicent Barletta. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parada López de Corselas, Manuel, and Santiago Martín Sandoval. 2014. Un conjunto artístico de glorificación en un espacio litúrgico: El cardenal Mendoza y la catedral de Toledo. In Curso de Arquitectura Litúrgica. La arquitectura al servicio de la liturgia. Edited by Jesús R. Folgado García. Madrid: Fundación San Juan, pp. 103–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda, Felipe. 2002. “Ad vivum?” o como narrar en imágenes la historia de la Guerra de Granada. Reales Sitios: Revista de Patrimonio Nacional 154: 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda Espeso, Felipe. 2003. Relieves toledanos de la guerra de Granada: Reflexiones sobre el procedimiento narrativo y sus fuentes clásicas. In Correspondencia e integración de las Artes: XIV Congreso nacional de Historia del Arte: Málaga, del 18–21 de Septiembre. Edited by Isidoro Coloma, María Teresa Sauret Guerrero, Belén Calderón Roca and Raúl Luque Ramírez. Málaga: Universidad de Málaga, vol. 1, pp. 345–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda Espeso, Felipe. 2009. Pedro González de Mendoza, de Toledo a Roma. El patronazgo de Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. Entre la arqueología y la filología. In Le rôle des cardinaux dans la diffusion des formes nouvelles à la Rennaisance. Edited by Frédérique Lemerle, Yves Pauwels and Gennaro Toscano. Villeneuve d’Ascq: IRHIS, pp. 217–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, Pilar. 2003. Historia política en música. In El Oficio de la Toma de Granada. Edited by Francisco Javier Martínez Medina, Pilar Ramos López, Elisa Varela Rodríguez and Hermenegildo de la Campa. Granada: Diputación Provincial, pp. 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Giovanni. 2017. La Guerra de Granada en la correspondencia diplomática de los embajadores de Ferrar en Nápoles (1482–1491). In La guerra de Granada en su contexto internacional. Edited by Daniel Baloup and Raúl González Arévalo. Toulouse: Presses universitaries du Midi, pp. 197–232. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Carrajo, Manuel. 1963. «Oficio de la exaltación de la fe» de Fr. Diego de Muros. Estudios Revista trimestral publicada por los padres de la Orden de la Merced 61: 325–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Valencia, Vicente. 1970. Isabel la Católica en la opinión de españoles y extranjeros. Tomo III, Apéndices. Valladolid: Instituto Isabel La Católica de Historia Eclesiástica. [Google Scholar]

- Romero de Lecea, Carlos. 1973. Hernando de Talavera y el tránsito en España del manuscrito al impreso. In Studia Hieronymiana. VI Centenario de la Orden de San Jerónimo. Madrid: Orden Jerónima, vol. I, pp. 317–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti, Edoardo. 2018. Nemo crucis titulos tam convenienter habebat quam tu. Entre profecía y devoción: Símbolos e imágenes en el programa religioso y político de Bernardo López de Carvajal. In Visiones imperiales y profecía; Roma, España, Nuevo Mundo. Edited by Stefania Pastore and Mercedes García-Arenal. Madrid: Abada, pp. 178–218. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador Miguel, Nicasio. 2016. Cisneros en Granada y la quema de libros islámicos. In La Biblia políglota complutense en su contexto. Edited by Antonio Alvar Ezquerra. Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá, pp. 153–84. [Google Scholar]

- St. Pius, V. 1568. Bull Quod a nobis. Rome, July 9. [Google Scholar]

- Toesca, Ilaria. 1967. A majolica inscription in Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. In Essays Presented to Rudolf Wittkower on His Sixty-Fifth Birthday. Edited by Douglas Fraser and Howard Hibbard. London: Phaidon Press, vol. 2, pp. 102–05. [Google Scholar]

- Vega García-Ferrer, María Julieta. 2004. Isabel la Católica y Granada. La Misa y el Oficio de Fray Hernando de Talavera. Granada: Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía. [Google Scholar]

- Vega García-Ferrer, María Julieta, ed. 2021. Fray Hernando de Talavera. Biografías antiguas. Granada: Nuevo Inicio. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara Ciordia, Javier. 2019. «Agustinismo político» y los espejos de los príncipes. Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia 28: 221–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Folgado García, J.R. Nominatissima urbs Granate: The Cultural Clash between Islam and Christianity after the Capitulation of the Nasrid Kingdom and Its Repercussions on the Arts. Religions 2023, 14, 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070873

Folgado García JR. Nominatissima urbs Granate: The Cultural Clash between Islam and Christianity after the Capitulation of the Nasrid Kingdom and Its Repercussions on the Arts. Religions. 2023; 14(7):873. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070873

Chicago/Turabian StyleFolgado García, Jesús R. 2023. "Nominatissima urbs Granate: The Cultural Clash between Islam and Christianity after the Capitulation of the Nasrid Kingdom and Its Repercussions on the Arts" Religions 14, no. 7: 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070873

APA StyleFolgado García, J. R. (2023). Nominatissima urbs Granate: The Cultural Clash between Islam and Christianity after the Capitulation of the Nasrid Kingdom and Its Repercussions on the Arts. Religions, 14(7), 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070873