Children’s and Adults’ Perceptions of Religious and Secular Interventions for Incarcerated Individuals in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Redemption, Incarceration, and Religion

1.2. The Importance of a Developmental Perspective

1.3. The Current Study

2. Results

2.1. Preliminary Analyses

2.2. Attitudes toward the Incarcerated Individual

2.3. Views Regarding Incarceration’s Effectiveness

2.4. Beliefs in Incarcerated Individuals’ Unchanging Essences

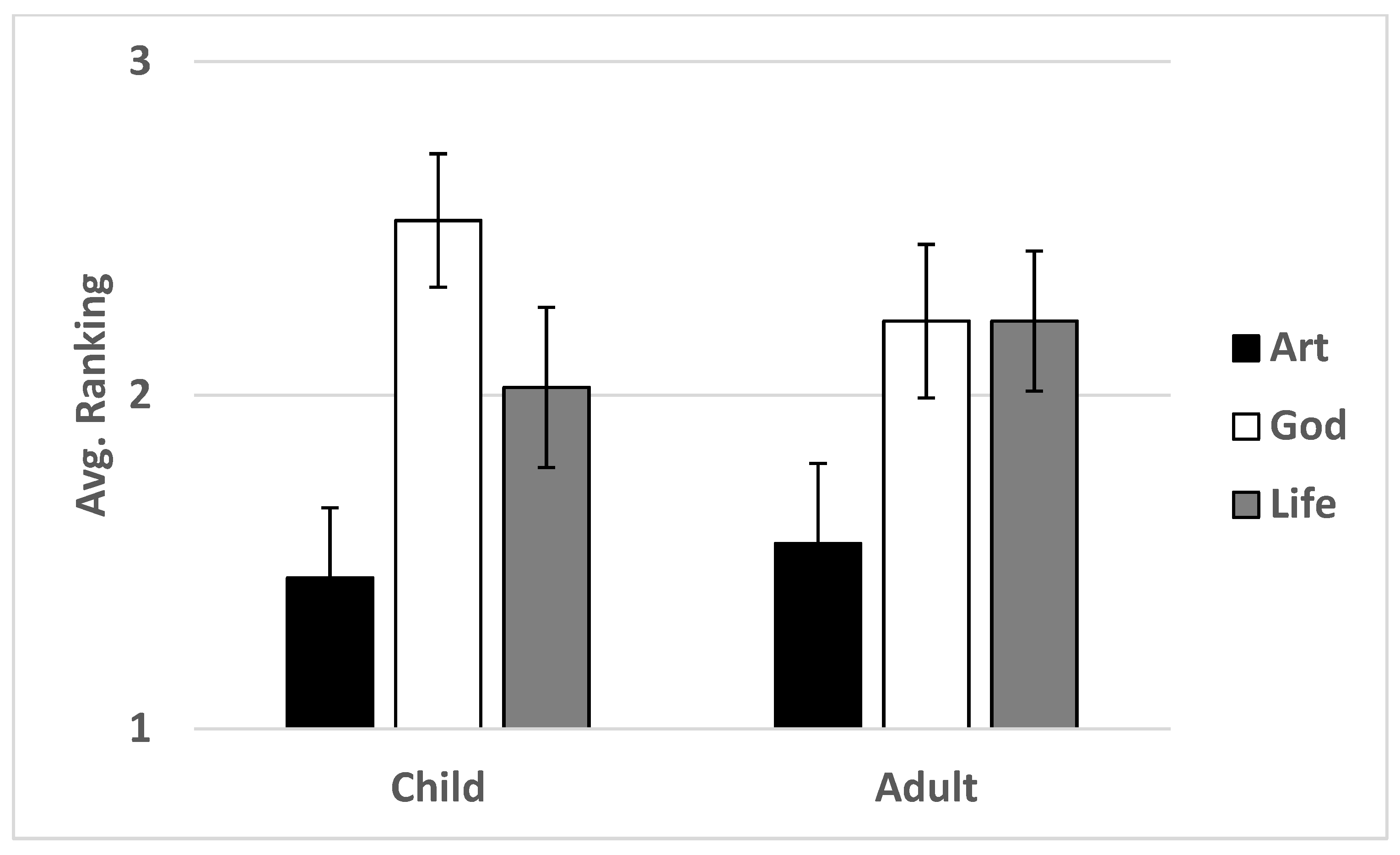

2.5. Rankings of Best/Worst Person

3. Discussion

3.1. Theoretical and Translational Implications

3.2. Limitations and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Procedure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, Michelle. 2012. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blagden, Nicholas, Belinda Winder, and Rebecca Lievesley. 2020. ‘The resurrection after the old has gone and the new has come’: Understanding narratives of forgiveness, redemption and resurrection in Christian individuals serving time in custody for a sexual offence. Psychology, Crime & Law 26: 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Paul. 2012. Religion, morality, evolution. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 179–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boddie, Stephanie C., and Cary Funk. 2012. Religion in Prisons: A 50-State Survey of Prison Chaplains. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/religion-prisons-50-state-survey-prison-chaplains (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Boseovski, Janet J. 2010. Evidence for “rose-colored glasses”: An examination of the positivity bias in young children’s personality judgments. Child Development Perspectives 4: 212–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregant, Jessica, Alex Shaw, and Katherine D. Kinzler. 2016. Intuitive jurisprudence: Early reasoning about the functions of punishment. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 13: 693–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Thom. 2012. Punishment. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Iannuzzi, Jazmin L., Stephanie McKee, and Will M. Gervais. 2018. Atheist horns and religious halos: Mental representations of atheists and theists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 147: 292–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, E. Ann. 2022. Prisoners in 2021—Statistical Tables. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/p21st.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Diesendruck, Gil, and Tali Lindenbaum. 2009. Self-protective optimsim: Children’s biased beliefs about the stability of traits. Social Development 18: 946–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesendruck, Gil, Dana Birnbaum, Inas Deeb, and Gili Segall. 2013. Learning what is essential: Relative and absolute changes in children’s beliefs about the heritability of ethnicity. Journal of Cognition and Development 14: 546–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlea, James P., and Larisa Heiphetz. 2020. Children’s and adults’ understanding of punishment and the criminal justice system. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 87: 103913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlea, James P., and Larisa Heiphetz. 2021. Children’s and adults’ views of punishment as a path to redemption. Child Development 92: e398–e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, William L. 2022. The cycle of life and story: Redemptive autobiographical narratives and prosocial behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology 43: 213–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, William L., and Jessica L. Tracy. 2013. Sobering stories: Narratives of self-redemption predict behavioral change and improved health among recovering alcoholics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104: 576–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durose, Matthew R., and Leonardo Antenangeli. 2021. Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 34 States in 2012: A 5-Year Follow-Up Period (2012–2017). Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/recidivism-prisoners-released-34-states-2012-5-year-follow-period-2012-2017 (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Eberhardt, Jennifer L., Phillip A. Goff, Valerie J. Purdie, and Paul G. Davies. 2004. Seeing black: Race, crime, and visual processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87: 876–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rachel. 2020. Redemption and reproach: Religion and carceral control in action among women in prison. Criminology 58: 747–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G. 1992. Are religious people nice people? Evidence from the National Survey of Black Americans. Social Forces 71: 411–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Edward O., and Jennifer E. Cossyleon. 2017. “I went through it so you don’t have to”: Faith-based community organizing for the formerly incarcerated. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 662–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, Susan A. 2003. The Essential Child: Origins of Essentialism in Everyday Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, Susan A., Gail D. Heyman, and Cristine H. Legare. 2007. Developmental changes in the coherence of essentialist beliefs about psychological characteristics. Child Development 78: 757–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervais, Will M., Dimitris Xygalatas, Ryan T. McKay, Michiel van Elk, Emma Buchtel, Mark Aveyard, Sarah R. Schiavone, Ilan Dar-Nimrod, Annika M. Svedholm-Hakkinen, Tapani Riekki, and et al. 2017. Global evidence of extreme intuitive moral prejudice against atheists. Nature Human Behavior 1: 0151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiphetz, Larisa. 2020. The development and consequences of moral essentialism. Advances in Child Development and Behavior 59: 165–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiphetz, Larisa, and Liane L. Young. 2019. Children’s and adults’ affectionate generosity toward members of different religious groups. American Behavioral Scientist 63: 1910–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiphetz, Larisa, Elizabeth S. Spelke, and Liane L. Young. 2015. In the name of God: How children and adults judge agents who act for religious versus secular reasons. Cognition 144: 134–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiphetz, Larisa, Elizabeth S. Spelke, Paul L. Harris, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2014. What do different beliefs tell us? An examination of factual, opinion-based, and religious beliefs. Cognitive Development 30: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiphetz, Larisa, Jonathan D. Lane, Adam Waytz, and Liane L. Young. 2018. My mind, your mind, and God’s mind: How children and adults conceive of different agents’ moral beliefs. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 36: 467–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hough, Mike, Ben Radford, Jonathan Jackson, and Julian R. Roberts. 2013. Attitudes to Sentencing and Trust in Justice: Exploring Trends from the Crime Survey for England and Wales. Available online: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/50440/1/Jackson_Attitudes_sentencing_trust_2013.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Humanists International. 2022. Report Reveals the Impact of the Precarious State of Secularism Globally. Available online: https://humanists.international/2022/12/secularism-in-the-balance/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Imhoff, Roland, and Rainer Banse. 2009. Ongoing victim suffering increases prejudice: The case of secondary anti-Semitism. Psychological Science 20: 1443–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Byron R. 2004. Religious programs and recidivism among former inmates in prison fellowship programs: A long-term follow-up study. Justice Quarterly 21: 329–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Megan K., Wade C. Rowatt, and Jordan P. LaBouff. 2012. Religiosity and prejudice revisited: In-group favoritism, out-group derogation, or both? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 4: 154–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Kristen M., Kelly Hope, and Naftali Raz. 2009. Life span adult faces: Norms for age, familiarity, memorability, mood, and picture quality. Experimental Aging Research 35: 268–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Jonathan D., Henry M. Wellman, and E. Margaret Evans. 2010. Children’s understanding of ordinary and extraordinary minds. Child Development 81: 1475–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latessa, Edward J., Shelley L. Johnson, and Deborah Koetzle. 2020. What Works (and Doesn’t) in Reducing Recidivism. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Young-eun, Ayse Payir, and Larisa Heiphetz. forthcoming. Benevolent God concepts and past kind behaviors induce generosity toward outgroups. Social Cognition.

- Lockhart, Kristi L., Nobuko Nakashima, Kayoko Inagaki, and Frank C. Keil. 2008. From ugly duckling to swan? Japanese and American beliefs about the stability and origins of traits. Cognitive Development 23: 155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Gretchen E., Patricia Gurin, and Biren A. Nagda. 2002. Education and understanding structural causes for group inequalities. Political Psychology 19: 305–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, Lindsay C., and Jodi A. Quas. 2009. Children’s suggestibility: Areas of consensus and controversy. In The Evaluation of Child Sexual abuse Allegations: A Comprehensive Guide to Assessment and Testimony. Edited by Kathryn Kuehnle and Mary Connell. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 267–97. [Google Scholar]

- Manza, Jeff, and Christopher Uggen. 2008. Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, Dan. 2006. The Redemptive Self: Stories Americans Live by. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mears, Daniel P., and Joshua C. Cochran. 2014. Prisoner Reentry in the Era of Mass Incarceration. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Medin, Douglas L., and Andrew Ortony. 1989. Psychological essentialism. In Similarity and Analogical Reasoning. Edited by Stella Vosniadou and Andrew Ortony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 179–95. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci, Larry, and Elliot Turiel. 1993. God’s word, religious rules, and their relation to Christian and Jewish children’s concepts of morality. Child Development 64: 1475–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Thomas P., and Michael Perreyclear. 2002. Prison religion in action and its influence on offender rehabilitation. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 35: 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogletree, Aaron M., and Rosemary Blieszner. 2022. Dark times and second chances: Perceived growth from adversity. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 94: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Kristina R., and Alex Shaw. 2011. ‘No fair, copycat!’: What children’s response to plagiarism tells us about their understanding of ideas. Developmental Science 14: 431–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pager, Devah. 2007. Marked: Race, Crime, and Finding Work in an Era of Mass Incarceration. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pasek, Micahel H., Crystal Shackleford, Julia M. Smith, Allon Vishkin, Anne Lehner, and Jeremy Ginges. 2020. God values the lives of my out-group more than I do: Evidence from Fiji and Israel. Social Psychological and Personality Science 11: 1032–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2015. Religious Landscape Study. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Pew Research Center. 2017. A Growing Share of Americans Say It’s Not Necessary to Believe in God to Be Moral. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/10/16/a-growing-share-of-americans-say-its-not-necessary-to-believe-in-god-to-be-moral/ (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Preston, Jesse L., and Ryan S. Ritter. 2013. Different effects of religion and God on prosociality with the ingroup and outgroup. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39: 1471–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purzycki, Benjamin G., Anne C. Pisor, Coren Apicella, Quentin Atkinson, Emma Cohen, Joseph Henrich, Richard McElreath, Rita A. McNamara, Ara Norenzayan, Aiyana K. Willard, and et al. 2018. The cognitive and cultural foundations of moral behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior 39: 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, Marajorie, and Tara M. Mandalaywala. 2017. The development and developmental consequences of social essentialism. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews 8: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richert, Rebekah A., Nicholas J. Shaman, Anondah R. Saide, and Kirsten A. Lesage. 2016. Folding your hands helps God hear you: Prayer and anthropomorphism in parents and children. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion 27: 140–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, Myron, and Marjorie Taylor. 1992. Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds? In Language, Interaction and Social Cognition. Edited by Gun R. Semin and Klaus Fiedler. Sauzend Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rowatt, Wade C., Lewis M. Franklin, and Marla Cotton. 2005. Patterns and personality correlates of implicit and explicit attitudes toward Christians and Muslims. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 44: 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, Julian M., and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2021. Toward an understanding of structural racism: Implications for criminal justice. Science 374: 286–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttenberg, Danya. 2022. On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbah, Cosmas E. 2018. Sin and redemption in Christianity and Islam. In Theological Issues in Christian-Muslim Dialogue. Edited by Charles Tieszen. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, Ryan D., and John F. Frana. 2009. Spirituality and religion, emotional coping, and criminal desistance: A qualitative study of men undergoing change. Sociological Spectrum 29: 718–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotter, Erica B., and Deborah E. Ward. 2015. Finding the silver lining: The relative roles of redemptive narratives and cognitive reappraisal in individuals’ emotional distress after the end of a romantic relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 32: 737–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, Mahesh, Elizabeth Kaplan, and Audun Dahl. 2019. Reasoning about the scope of religious norms: Evidence from Hindu and Muslim children in India. Child Development 90: E783–E802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, Tom R., and Yuen J. Huo. 2002. Trust in the Law: Encouraging Public Cooperation with the Police and Courts. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Uenal, Fatih, Robin Bergh, Jim Sidanius, Andreas Zick, Sasha Kimel, and Jonas Kunst. 2021. The nature of Islamophobia: A test of a tripartite view in five countries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 47: 275–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburd, David, David P. Farrington, Charlotte Gill, Mimi Ajzenstadt, Trevor Bennett, Kate Bowers, Michael S. Caudy, Katy Holloway, Shane Johnson, Friedrich Losel, and et al. 2017. What works in crime prevention and rehabilitation: An assessment of systematic reviews. Criminology & Public Policy 16: 415–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, Bruce. 2018. Homeward: Life in the Year after Prison. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Andrew L., and Samuel L. Perry. 2020. Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, Tatha. 2002. Original Sin: Origins, Developments, Contemporary Meanings. Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolle, Redeate G., Abby McLaughlin, and Larisa Heiphetz. 2021. The role of theory of mind and wishful thinking in children’s moralizing concepts of the Abrahamic God. Journal of Cognition and Development 22: 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Mark C., John Gartner, Thomas O’Connor, David Larson, and Kevin N. Wright. 1995. Long-term recidivism among federal inmates trained as volunteer prison ministers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 22: 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cohen, A.; Dunlea, J.P.; Solomon, L.H. Children’s and Adults’ Perceptions of Religious and Secular Interventions for Incarcerated Individuals in the United States. Religions 2023, 14, 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070821

Cohen A, Dunlea JP, Solomon LH. Children’s and Adults’ Perceptions of Religious and Secular Interventions for Incarcerated Individuals in the United States. Religions. 2023; 14(7):821. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070821

Chicago/Turabian StyleCohen, Aaron, James P. Dunlea, and Larisa Heiphetz Solomon. 2023. "Children’s and Adults’ Perceptions of Religious and Secular Interventions for Incarcerated Individuals in the United States" Religions 14, no. 7: 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070821

APA StyleCohen, A., Dunlea, J. P., & Solomon, L. H. (2023). Children’s and Adults’ Perceptions of Religious and Secular Interventions for Incarcerated Individuals in the United States. Religions, 14(7), 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070821