Secondary Traumatic Stress, Religious Coping, and Medical Mistrust among African American Clergy and Religious Leaders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. STS in Religious Leaders

3. ACEs, Trauma, and STS in African American Communities

4. Barriers and Mistrust toward Healthcare

5. The African American Church

6. Religious Coping

7. The Present Study

8. Method

8.1. Participants

8.2. Procedure

9. Measures

9.1. ACEs

9.2. BCEs

9.3. Anxiety Symptoms

9.4. Depression Symptoms

9.5. PTSD Symptoms

9.6. STS Symptoms

9.7. Negative Religious Coping

9.8. Negative Religious Interaction

9.9. Medical Mistrust

10. Results

10.1. Descriptive Statistics

10.2. Correlation Analyses

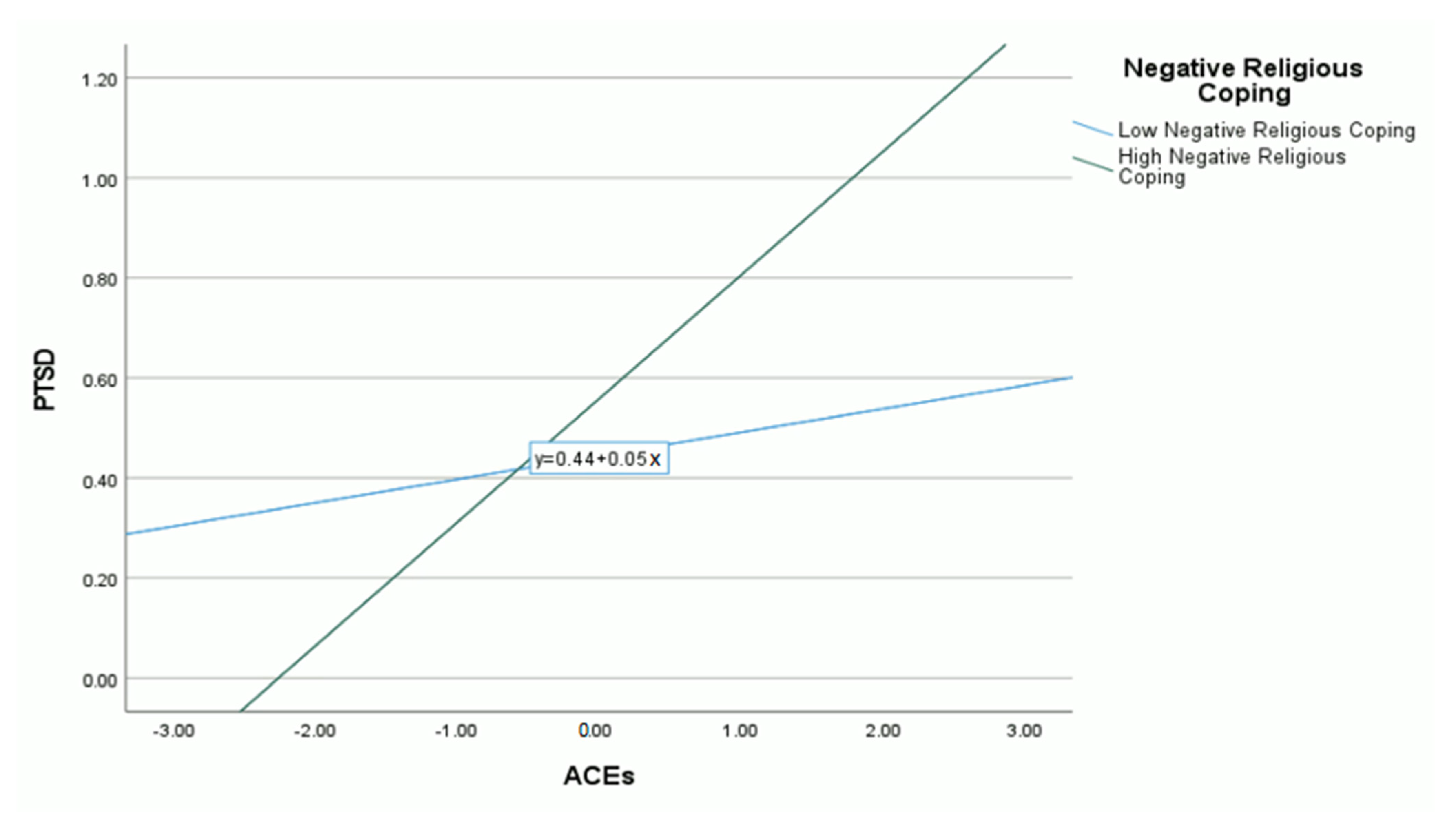

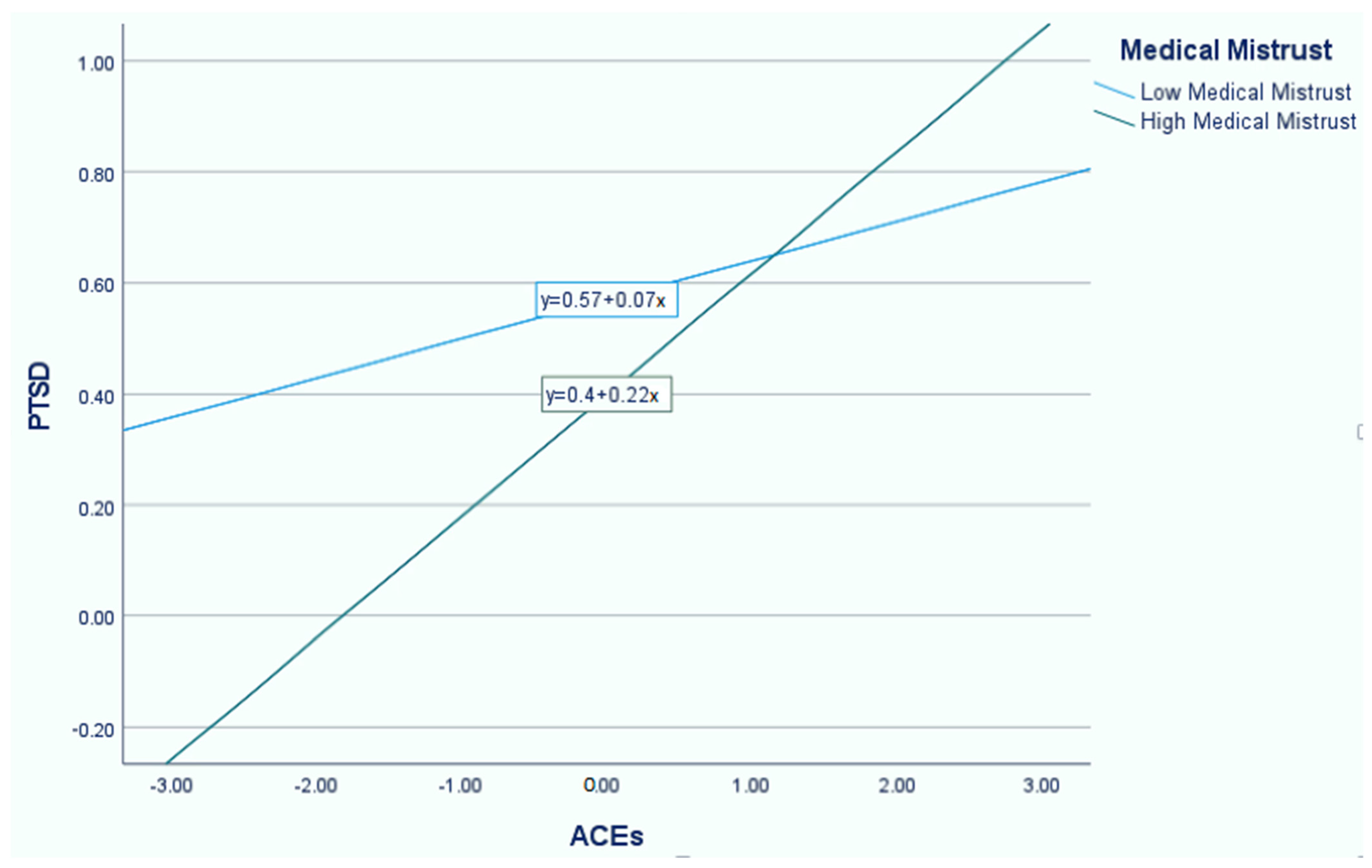

10.3. Moderating Effect of Negative Religious Coping and Medical Mistrust

10.4. Effect of Negative Religious Interaction on STS

11. Discussion

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adofoli, Grace, and Sarah E. Ullman. 2014. An Exploratory Study of Trauma and Religious Factors in Predicting Drinking Outcomes in African American Sexual Assault Survivors. Feminist Criminology 9: 208–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, Margarita, Lisa R. Fortuna, Julia Y. Lin, Frances L. Norris, Shan Gao, David T. Takeuchi, James S. Jackson, Patrick E. Shrout, and Anne Valentine. 2013. Prevalence, risk, and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder across ethnic and racial minority groups in the US. Medical Care 51: 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Katrina, Mary Putt, Chanita H. Halbert, David Grande, Jerome Sanford Schwartz, Kaijun Liao, Noora Marcus, Mirar B. Demeter, and Judy A. Shea. 2013. Prior Experiences of Racial Discrimination and Racial Differences in Health Care System Distrust. Medical Care 51: 144–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, Moses Kumi, Joseph Osafo, and Isaac Agyapong. 2014. The role of Pentecostal clergy in mental health-care delivery in Ghana. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 601–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnaani, Anu, and Brittany Hall-Clark. 2017. Recent developments in understanding ethnocultural and race differences in trauma exposure and PTSD. Current Opinion in Psychology 14: 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assini-Meytin, Luciana C., Rebecca L. Fix, Kerry M. Green, Reshmi Nair, and Elizabeth J. Letourneau. 2021. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Mental Health, and Risk Behaviors in Adulthood: Exploring Sex, Racial, and Ethnic Group Differences in a Nationally Representative Sample. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 15: 833–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Nehami. 2014. Professionals’ double exposure in the shared traumatic reality of wartime: Contributions to professional growth and stress. British Journal of Social Work 44: 2113–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, Carlos I. Pérez, Nicholas J. Sibrava, Laura Kohn-Wood, Andri S. Bjornsson, Caron Zlotnick, Risa Weisberg, and Martin B. Keller. 2014. Posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans: A two year follow-up study. Psychiatry Research 220: 376–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, Christina, Jennifer Jones, Narangerel Gombojav, Jeff Linkenbach, and Robert Sege. 2019. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample. JAMA Pediatrics 173: e193007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, Brian E. 2007. Prevalence of Secondary Traumatic Stress among Social Workers. Social Work 52: 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant-Davis, Thema, Sarah E. Ullman, Yuying Tsong, and Robyn Gobin. 2011. Surviving the storm: The role of social support and religious coping in sexual assault recovery of African American women. Violence against Women 17: 1601–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant-Davis, Thema, Sarah Ullman, Yuying Tsong, Gera Anderson, Pamela Counts, Shaquita Tillman, Cecile Bhang, and Anthea Gray. 2015. Healing Pathways: Longitudinal Effects of Religious Coping and Social Support on PTSD Symptoms in African American Sexual Assault Survivors. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 16: 114–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, Diane J. 2009. Pastoral burnout and the impact of personal spiritual renewal, rest-taking, and support system practices. Pastoral Psychology 58: 273–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Ga-Young. 2011. Secondary Traumatic Stress of Service Providers who Practice with Survivors of Family or Sexual Violence: A National Survey of Social Workers. Smith College Studies in Social Work 81: 101–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Lisa A., Debra L. Roter, Rachel L. Johnson, Daniel E. Ford, Donald M. Steinwachs, and Neil R. Powe. 2003. Patient-Centered Communication, Ratings of Care, and Concordance of Patient and Physician Race. Annals of internal medicine 139: 907–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, AliceAnn, Jacob R. Miller, Aaron Cheung, Lynneth Kirsten Novilla, Rozalyn Glade, M. Lelinneth B. Novilla, Brianna M. Magnusson, Barbara L. Leavitt, Michael D. Barnes, and Carl L. Hanson. 2019. ACEs and counter-ACEs: How positive and negative childhood experiences influence adult health. Child Abuse & Neglect 96: 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, Adolfo G., and Kerth O’Brien. 2019. Racial centrality may be linked to mistrust in healthcare institutions for African Americans. Journal of Health Psychology 24: 2022–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, Adolfo G., Kerth O’Brien, and Somnath Saha. 2016. African American experiences in healthcare: “I always feel like I’m getting skipped over”. Health Psychology 35: 987–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, Joseph M., Lisseth Rojas-Flores, Wesley H. McCormick, Josephine Hwang Koo, Laura Cadavid, Francis Alexis Pineda, Elisabet Le Roux, and Tommy Givens. 2019. Spiritual struggles and ministry-related quality of life among faith leaders in Colombia. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 11: 148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Maxine, and Maxine Johnson. 2020. Exploring Black Clergy Perspectives on Religious/Spiritual Related Domestic Violence: First Steps in Facing those Who Wield the Sword Abusively. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 30: 950–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luna, Joseph E., and David C. Wang. 2021. Child Traumatic Stress and the Sacred: Neurobiologically Informed Interventions for Therapists and Parents. Religions 12: 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHaven, Mark J., Irby B. Hunter, Laura Wilder, James W. Walton, and Jarett Berry. 2004. Health programs in faith-based organizations: Are they effective? American Journal of Public Health 94: 1030–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, Benjamin R. 2010. The impact of behaviors upon burnout among parish- based clergy. The Journal of Religion and Health 49: 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doom, Jenalee R., Deborah Seok, Angela J. Narayan, and Kathryn R. Fox. 2021. Adverse and Benevolent Childhood Experiences Predict Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Adversity and Resilience Science 2: 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, Vincent J., Robert F. Anda, Dale Nordenberg, David F. Williamson, Alison M. Spitz, Valerie Edwards, and James S. Marks. 1998. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14: 245–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. 1999. Religious Support. In Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. Kalamazoo: Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group, pp. 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Figley, Charles R., ed. 1995. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella, Kevin, Peter Franks, Mark P. Doescher, and Barry G. Saver. 2002. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: Findings from a national sample. Medical Care 40: 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannelly, Kevin J., Rabbi Stephen B. Roberts, and Andrew J. Weaver. 2005. Correlates of Compassion Fatigue and Burnout in Chaplains and Other Clergy who Responded to the September 11th Attacks in New York City. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling: Advancing Theory and Professional Practice Through Scholarly and Reflective Publications 59: 213–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie J., Stephen H. Louden, and Christopher J. F. Rutledge. 2004. Burnout among Roman Catholic parochial clergy in England and Wales: Myth or reality? Review of Religious Research 46: 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmon, Moses V., and James T. Roberson. 2004. Churches, Academic Institutions, and Public Health: Partnerships to Eliminate Health Disparities. North Carolina Medical Journal 65: 368–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Stephanie, Susan Furr, Claudia Flowers, and Mary Thomas Burke. 2001. Research and Theory Religion and Spirituality in Coping With Stress. Counseling and Values 46: 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Allana, and Christopher D. Gjesfjeld. 2013. Clergy: A partner in rural mental health? Journal of Rural Mental Health 37: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, Wizdom Powell, Derrick Matthews, and Giselle Corbie-Smith. 2010a. Psychosocial Factors Associated With Routine Health Examination Scheduling and Receipt Among African American Men. Journal of the National Medical Association 102: 276–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, Wizdom Powell, Derrick Matthews, Dinushika Mohottige, Amma Agyemang, and Giselle Corbie-Smith. 2010b. Masculinity, Medical Mistrust, and Preventive Health Services Delays Among Community-Dwelling African-American Men. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25: 1300–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankerson, Sidney H., and Myrna M. Weissman. 2012. Church-Based Health Programs for Mental Disorders Among African Americans: A Review. Psychiatric Services 63: 243–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, Krystal. 2015. Black Churches’ capacity to respond to the mental health needs of African Americans. Social Work & Christianity 42: 296–312. [Google Scholar]

- Hendron, Jill Anne, Pauline Irving, and Brian Taylor. 2011. The Unseen Cost: A Discussion of the Secondary Traumatization Experience of the Clergy. Pastoral Psychology 61: 221–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holaday, Margot, Trey Lackey, Michelle Boucher, and Reba Glidewell. 2001. Secondary stress, burnout and the clergy. American Journal of Pastoral Counselling 4: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, Jodi M., Ann Rothschild, Fatima Mirza, and Monique Shapiro. 2013. Risk for Burnout and Compassion Fatigue and Potential for Compassion Satisfaction Among Clergy: Implications for Social Work and Religious Organizations. Journal of Social Service Research 39: 455–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, G. Eric, Laurence J. Kirmayer, Morton Weinfeld, and Jean-Claude Lasry. 2005. Religious Practice and Psychological Distress: The Importance of Gender, Ethnicity and Immigrant Status. Transcultural Psychiatry 42: 657–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Bernice Roberts, Christopher Clomus Mathis, and Angela K. Woods. 2007. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: Healthcare for diverse populations. Journal of Cultural Diversity 14: 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, Kurt, and Robert L Spitzer. 2002. The PHQ-9: A New Depression Diagnostic and Severity Measure. Psychiatric Annals 32: 509–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasater, Thomas M., Diane M. Becker, Martha N. Hill, and Kim M. Gans. 1997. Synthesis of findings and issues from religious-based cardiovascular disease prevention trials. Annals of Epidemiology 7: S46–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVeist, Thomas A., Lydia A. Isaac, and Karen Patricia Williams. 2009. Mistrust of Health Care Organizations Is Associated with Underutilization of Health Services. Health Services Research 44: 2093–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Luona, Karen Stamm, and Peggy Christidis. 2018. How diverse is the psychology workforce? Monitor on Psychology 49: 19. Available online: http://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/02/datapoint (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Lowe, Gabriel B., David C. Wang, and Eu Gene Chin. 2022. Experiential Avoidance Mediates the Relationship between Prayer Type and Mental Health before and through the COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 13: 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, Wesley H., Timothy D. Carroll, Brook M. Sims, and Joseph Currier. 2017. Adverse childhood experiences, religious/spiritual struggles, and mental health symptoms: Examination of mediation models. Mental Health Religion & Culture 20: 1042–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, Melissa T., Derek C. Ford, Katie A. Ports, and Angie S. Guinn. 2018. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences From the 2011–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 States. JAMA Pediatrics 172: 1038–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosley-Johnson, Elise, Jennifer A. Campbell, Emma Garacci, Rebekah J. Walker, and Leonard E. Egede. 2021. Stress that Endures: Influence of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Daily Life Stress and Physical Health in Adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders 284: 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Angela J., Alicia F. Lieberman, and Ann S. Masten. 2021. Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Clinical Psychology Review 85: 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, Angela J., Luisa M. Rivera, Rosemary E. Bernstein, William W. Harris, and Alicia F. Lieberman. 2018. Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: A pilot study of the benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse & Neglect 78: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neighbors, Harold W., Marc A. Musick, and David R. Williams. 1998. The African American Minister as a Source of Help for Serious Personal Crises: Bridge or Barrier to Mental Health Care? Health Education & Behavior 25: 759–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth, Margaret Feuille, and Donna Burdzy. 2011. The Brief RCOPE: Current Psychometric Status of a Short Measure of Religious Coping. Religions 2: 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L., Cheryl L. Holt, Daisy Le, Juliette Christie, and Beverly Rosa Williams. 2018. Positive and negative religious coping styles as prospective predictors of well-being in African Americans. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10: 318–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Jennifer Shepard. 2009. Variations in Pastors’ Perceptions of the Etiology of Depression By Race and Religious Affiliation. Community Mental Health Journal 45: 355–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, Jennifer Shepard. 2014. The influence of secular and theological education on pastors’ depression intervention decisions. Journal of Religion & Health 53: 1398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Jennifer Shepard, and Krystal Hays. 2016. A spectrum of belief: A qualitative exploration of candid discussions of clergy on mental health and healing. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 19: 600–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, Monica E., Angela Odoms-Young, Michael T. Quinn, Rita Gorawara-Bhat, Shannon C. Wilson, and Marshall H. Chin. 2010. Race and shared decision-making: Perspectives of African-Americans with diabetes. Social Science & Medicine 71: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, Chintha Kumari, Rakesh Pandey, and Abhay Kumar Srivastava. 2018. Role of Religion and Spirituality in Stress Management Among Nurses. Psychological Studies 63: 187–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, Darryl P. 2014. The Black Church, Values, and Secular Counseling: Implications for Counselor Education and Practice. Counseling and Values 59: 208–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Wizdom, Jennifer Richmond, Dinushika Mohottige, Irene Yen, Allison Joslyn, and Giselle Corbie-Smith. 2019. Medical Mistrust, Racism, and Delays in Preventive Health Screening Among African-American Men. Behavioral Medicine 45: 102–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, Annabel, Michelle Bovin, Derek Smolenski, Brian Marx, Rachel Kimerling, Michael Jenkins-Guarnieri, Danny Kaloupek, Paula P. Schnurr, Anica Pless Kaiser, Yani E. Leyva, and et al. 2016. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and Evaluation Within a Veteran Primary Care Sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine 31: 1206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A. L., S. E. Gilman, J. Breslau, N. Breslau, and K. C. Koenen. 2011. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine 41: 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolfsson, Lisa, and Inga Tidefors. 2009. “Shepherd my sheep”: Clerical readiness to meet psychological and existential needs from victims of sexual abuse. Pastoral Psychology 58: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, Robert L., Kurt Kroenke, Janet B. W. Williams, and Bernd Löwe. 2006. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine 166: 1092–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J. Louis, Bruce E. Winston, and Mihai C. Bocarnea. 2012. Predicting the Level of Pastors’ Risk of Termination/Exit from the Church. Pastoral Psychology 61: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoont, Michele R., David B. Nelson, Maureen Murdoch, Nina A. Sayer, Sean Nugent, Thomas Rector, and Joseph Westermeyer. 2015. Are there racial/ethnic disparities in VA PTSD treatment retention? Depression and Anxiety 32: 415–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamm, Beth Hudnall. 1995. Professional Quality of Life Scale (PROQOL) [Database Record]. Washington, DC: APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar]

- Streets, Frederick. 2015. Social work and a trauma-informed ministry and pastoral care: A collaborative agenda. Social Work & Christianity 42: 470–87. [Google Scholar]

- St. Vil, Noelle M., Bushra Sabri, Vania Nwokolo, Kamila A. Alexander, and Jacquelyn C. Campbell. 2016. A Qualitative Study of Survival Strategies Used by Low-Income Black Women Who Experience Intimate Partner Violence. Social Work 62: 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Rabbi Bonita E., Andrew J. Weaver, Kevin J. Flannelly, and Rabbi David J. Zucker. 2006. Compassion fatigue and burnout among rabbis working as chaplains. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling 60: 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Robert Joseph, Linda M. Chatters, and Jeff Levin. 2004. Religion in the Lives of African Americans: Social, Psychological, and Health Perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Hannah E., Rachel Wamser-Nanney, and Kathryn H. Howell. 2021. Relationships Between Childhood Interpersonal Trauma, Religious Coping, Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms, and Resilience. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP11296–NP11314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, David C., Daniel Strosky, and Alexis Fletes. 2014. Secondary and vicarious trauma: Implications for faith and clinical practice. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 33: 281–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Philip S., Patricia A. Berglund, and Ronald C. Kessler. 2003. Patterns and Correlates of Contacting Clergy for Mental Disorders in the United States. Health Services Research 38: 647–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitt-Glover, Melicia C., Patricia E. Hogan, Wei Lang, and Daniel P. Heil. 2008. Pilot Study of a Faith-Based Physical Activity Program Among Sedentary Blacks. Preventing Chronic Disease 5: A51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, David R., and Selina A. Mohammed. 2009. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, David R., and Tara R. Earl. 2007. Commentary: Race and mental health more questions than answers. International Journal of Epidemiology 36: 758–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, LaVerne, Robyn Gorman, and Sidney Hankerson. 2014. Implementing a mental health ministry committee in faith-based organizations: The promoting emotional wellness and spirituality program. Social Work in Health Care 53: 414–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Terrie M. 2008. Black Pain: It Just Looks Like We’re Not Hurting. New York: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield, Harrold L. 1988. The historical and changing role of the Black church: The social and political implications. The Western Journal of Black Studies 12: 127–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Zachary B., David C. Wang, Collin Lee, Haleigh Barnes, Tania Abouezzeddine, and Jamie Aten. 2021. Social support, religious coping, and traumatic stress among Hurricane Katrina survivors of southern Mississippi: A sequential mediational model. Traumatology 27: 336–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombe, Cheryl L. 2010. Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qualitative Health Research 20: 668–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhan, Joshua, David C. Wang, Andrea Canada, and Jonathan Schwartz. 2021. Growth after Trauma: The Role of Self-Compassion following Hurricane Harvey. Trauma Care 1: 119–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| ACEs | 2.27 | 2.35 |

| BCEs | 9.30 | 0.91 |

| Anxiety Symptoms | 5.72 | 7.22 |

| Depression Symptoms | 3.81 | 4.43 |

| STS Symptoms | 23.03 | 5.35 |

| PTSD Symptoms | 0.52 | 1.00 |

| Negative Religious Coping | 6.91 | 5.14 |

| Negative Religious Interaction | 3.54 | 1.56 |

| Medical Mistrust | 18.45 | 3.82 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ACEs | - | ||||||

| 2. BCEs | −0.347 ** | - | |||||

| 3. STS | 0.104 | −0.165 | - | ||||

| 4. Anxiety | 0.200 * | −0.096 | 0.553 ** | - | |||

| 5. Depression | 0.236 * | −0.064 | 0.484 * | 0.692 ** | - | ||

| 6. PTSD | 0.369 ** | −0.018 | 0.480 * | 0.188 | 0.297 ** | - | |

| 7. Negative religious coping | 0.106 | −0.148 | 0.070 | 0.149 | 0.195 | 0.065 | - |

| 8. Negative religious interaction | −0.033 | −0.150 | 0.630 ** | 0.031 | 0.076 | 0.072 | 0.283 ** |

| Coeff. | SE | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | i1 | 0.502 | 0.093 | 5.386 | 0.000 |

| ACEs (X) | b1 | 0.147 | 0.042 | 3.533 | 0.001 |

| Negative religious coping (M) | b2 | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.609 | 0.544 |

| Moderation effect (X x M) | b3 | 0.020 | 0.009 | 2.091 | 0.039 |

| R2 = 0.174, MSE = 0.844 | |||||

| F(3, 94) = 6.681, p < 0.001 | |||||

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Wondered whether God abandoned me. | 1.32 | 1.08 |

| Felt punished by God for my lack of devotion. | 1.26 | 1.02 |

| Wondered what I did for God to punish me. | 1.05 | 1.03 |

| Questioned God’s love for me. | 0.79 | 1.04 |

| Wondered whether my church had abandoned me. | 0.80 | 0.94 |

| Decided the devil made this happen. | 1.13 | 0.98 |

| Questioned the power of God. | 0.55 | 0.95 |

| Coeff. | SE | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | i1 | 0.484 | 0.093 | 5.208 | 0.000 |

| ACEs (X) | b1 | 0.145 | 0.042 | 3.424 | 0.001 |

| Medical mistrust (M) | b2 | −0.023 | 0.026 | −0.893 | 0.374 |

| Moderation effect (X x M) | b3 | 0.020 | 0.009 | 2.471 | 0.015 |

| R2 = 0.190, MSE = 0.830 | |||||

| F(3, 94) = 7.362, p < 0.001 | |||||

| Coeff. | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Religious Interaction | 2.034 | 3.720 | 0.001 |

| R = 0.630, R2 = 0.397 | |||

| F(1, 21) = 13.835 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roggenbaum, L.; Wang, D.C.; Dryjanska, L.; Holmes, E.; Lewis, B.A.; Brown, E.M. Secondary Traumatic Stress, Religious Coping, and Medical Mistrust among African American Clergy and Religious Leaders. Religions 2023, 14, 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060793

Roggenbaum L, Wang DC, Dryjanska L, Holmes E, Lewis BA, Brown EM. Secondary Traumatic Stress, Religious Coping, and Medical Mistrust among African American Clergy and Religious Leaders. Religions. 2023; 14(6):793. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060793

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoggenbaum, Laura, David C. Wang, Laura Dryjanska, Erica Holmes, Blaire A. Lewis, and Eric M. Brown. 2023. "Secondary Traumatic Stress, Religious Coping, and Medical Mistrust among African American Clergy and Religious Leaders" Religions 14, no. 6: 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060793

APA StyleRoggenbaum, L., Wang, D. C., Dryjanska, L., Holmes, E., Lewis, B. A., & Brown, E. M. (2023). Secondary Traumatic Stress, Religious Coping, and Medical Mistrust among African American Clergy and Religious Leaders. Religions, 14(6), 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060793