Abstract

Although many Hindu communities today foreground women as religious authorities, some lineages officially recognize only men as gurus and renouncers. If official models of religious authority are gendered masculine, what space do women have to embody holiness? This article investigates this question with reference to women in the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), a transnational religious organization that has developed prominent communities in India and abroad. Amidst an ongoing disagreement about whether women can be gurus in the organization, this article considers how devotee women are cultivating spaces of religious authority in their temple communities and online media forums through embodying Krishna bhakti as a form of vernacular holiness. This includes the development of personal websites and the use of YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok to produce media content that ranges from overtly devout recordings of temple lectures to subtle signals towards Krishna bhakti in the aesthetic style of social media influencers. Case studies discuss women affiliated with ISKCON communities in India and the US.

1. Introduction

Many Hindu communities today foreground women as religious authorities, in both formal institutional roles and as lived embodiments of sacred attainment. Major organizations such as the Mata Amritanandamayi Math (MAM) and Siddha Yoga are led by female gurus. In the former, Amma is an individual charismatic teacher who breaks both gender and caste hierarchies in her embodiment of holiness. In the latter, Gurumayi Chidvilasananda was imbued with authority over the Siddha Yoga lineage from Swami Muktananda, her male teacher and founder of the organization. Other female gurus have been central figures of holiness in Hindu traditions over the past century or inhabit regional followings (Pechilis 2004; Lucia 2014). Albeit often with resistance from the embedded patriarchy of the institutions they seek to represent, women have even been breaking boundaries and gaining more visibility in the traditionally male-dominated world of sadhus.

But what about those Hindu communities in which women are prohibited from becoming gurus and those in which sannyāsa, monastic renunciation, is both valued as the highest religious lifestyle and explicitly off limits to women? If official models of religious authority are gendered masculine, what space do women have to partake in holiness? This article investigates this question with reference to women in the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), a socially conservative, transnational Hindu community founded by Bengali sannyāsin A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami in New York in 1966. Centered on the devotional worship of Krishna, the organization has developed prominent communities throughout India and has opened temples or centers in almost every country globally. The early generation of American converts shares international authority with a range of leaders, and central nodes of ISKCON’s development over the past decades have been in urban India and among Indian diasporas. The organization has grown more flexible in its social codes in the twenty-first century, enabling various forms of dress beyond the traditional sari and dhoti for men and supporting members’ lay lifestyles as valid religious pathways alongside temple-based monastic life, generally lessening an early, stark division between inside and outside cultures (Rochford 2007; Karapanagiotis 2021). However, a brahmanically informed discourse of culture grounds the group in the idealization of a Sanskritic patriarchy embedded in texts such as the Laws of Manu.1 Consequently, after years of debate and marked internal disagreement, the organization was compelled to renew its prohibition of women gurus.

As ISKCON devotees are engaged in internal conversations about who can embody religious attainment for fellow members, they also represent their religious practice to broader audiences, including online. Gaur Gopal das, for instance, is one of several brahmacārī monks who have become known as motivational speakers in urban India. He has garnered almost seven million reported Instagram followers who partake of his life advice in short videos drawn from his lectures, pivoting well beyond ISKCON to address broad Hindu publics.2 In this fluid social context, mediating between a conservative religious institution and viewers outside, the roles women can occupy are also in flux, as are the spaces for conveying holiness themselves. Popular female teachers and influencers are developing prominent social media profiles that broadcast their messages to wider audiences and infuse the social media spaces of Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok with their models of ideal practice. It is in these fluid, decentralized spaces that lived models of holiness and authority reside, irrespective of institutional laws. Accordingly, I will situate my analysis in relation to female devotees’ engagement in online influencer culture.

Social media networks enable individuals to control their own public representations of religion and portrayals of personal attainment, within and beyond religious organizations.3 Here, expressions of religiosity mix with the aesthetics and vocabulary of social media influencers to fashion a new media space for representing holiness. ISKCON networks are internationally connected, although they also reflect local norms and ideals of religious practice. To convey this broad range, I will center my research on several case studies of prominent ISKCON-affiliated women in India and the US. I will highlight devotee women affiliated with the Indian temple communities on India’s East and West coasts, in Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, and Mumbai, Maharashtra, centering on their public profiles and use of social media. ISKCON is an inherently transnational community, with interconnected authority networks, and both the organization and influencer culture have strong ties to the US as well. Accordingly, I will expand my gaze to consider influencer roles inhabited by several ISKCON-affiliated women on America’s East and West coasts. I will stretch my analysis to include a younger generation of social media influencers whose profiles stretch beyond the explicitly religious but, in my assessment, are also buoyed by it. This range of figures spans the world of explicitly devout religious media to mainstream wellness-oriented influencer culture. In its midst, I will draw out formations of holiness communicated by these markedly different women who convey a broad range of possibilities in their varied representations of religious attainment.

2. Structures and Embodiments of Holiness in ISKCON

Devotee women’s influence operates against the backdrop of an institutional bar on recognizing women’s authority as formal gurus. To appreciate the significance of how women can exercise authority or model “holiness” in informal forums, I will begin by laying out the context of this debate and its implications. ISKCON temple communities are highly institutionalized groups grounded in the interpretations of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava tradition given by the organization’s founding guru, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, known by the honorific title Śrila Prabhupada. In his organization’s international spread, Bhaktivedanta did open some traditionally male roles to his female disciples. Joining ISKCON is, in many ways, a Sanskritizing process, as members of the community become deeply conversant in the Sanskrit śāstras, Purāṇic literature, and brahmanically oriented norms at the basis of the community’s often-cited scriptural corpus. Due to the ritual innovations that Bhaktivedanta adopted from his guru, Bhaktisiddhanta, in forming the society, one can even ritually become a brahmin. Two levels of initiation are available for devout ISKCON members: hari nāma, in which one formally receives a japa mālā (prayer beads) and commits to the lifestyle regulations of the group, and dīkṣā, known widely as “brahmin initiation” within ISKCON, in which one commits to a higher level of dedication and regulated behavior and obtains the ability to perform the ritual activities traditionally accorded to brahmin males. Except for the upanayana thread, brahmin initiation is available to dedicated devotee women as well as men in ISKCON internationally.

Bhaktivedanta also developed the template for his organization’s continuing authority structure between its founding in 1966 and his death in 1977. Before his passing, he instituted a multi-tiered authority system centralized in shared temple governance by an international Governing Body Commission (GBC) and an interconnected group of appointed successor gurus empowered with delivering initiation into the sādhana (personal religious practice) and lineage of ISKCON. These leadership roles were explicitly assigned to male followers, originally all of non-Indian ethnicity. From an initial number of eleven gurus in 1977, today, 96 initiating gurus exist in the international organization, spanning continents, ethnicities, languages, and āśramas, or vocations. The organization has increasingly expanded in India and among Indian-origin diaspora communities in South Africa, Fiji, Mauritius, the US, and the UK. It retains a prominently multiethnic leadership, however, and prominent gurus are from a range of ethnic backgrounds, including Ukrainian, Nigerian, and Japanese, as well as Black and White American and Indian. Despite these ethnic differences, devotees are folded into the organization’s social categorizations of āśramas, or stage-of-life categories drawn from the brahmanical social ideal of varṇāśrama dharma. While most ISKCON gurus are sannyāsins, a growing number are gṛhasthas, pious laypeople, the initial tier of renunciation in the interpretation of varṇāśrama dharma followed by ISKCON communities.4

Although the category of caste (or varna) is markedly fluid and not tied to birth among ISKCON interpretations of varṇāśrama dharma in determining who is qualified to teach or initiate disciples into the lineage, biological sex remains a fixed category. Official models of holiness are embodied in the male sannyāsin, the highest order of renunciation. While holiness is a concept that has no direct transition in Indic languages, the English word does figure into ideas of conveying religious respect in ISKCON. Men who have taken the order of renunciation known as sannyasa are often referred to with the prefix His Holiness (HH), an English approximation of Śrī Śrī, which harks back to the Victorian British linguistic influence on modern religious institutions. Other esteemed senior members of the community—women and men—may be referred to as “Your Grace”. Additionally, in ISKCON, as well as in conservative Indian society broadly, marriage is strongly compelled, particularly for women. While in India and abroad, there are prominent elder women who have adopted the vānaprastha lifestyle, a classical Sanskritic precursor to sannyāsa, everyday women’s domains of religious attainment are funneled through a societal ideal of patriarchal marriage. Although there are numerous women within ISKCON who embody religious authority and holiness for many devotees, their role is not formalized through the central institution.

The male authority structure set in place by Bhaktivedanta has been largely preserved, with notable exceptions of occasional female GBC members and temple presidents in the Global North. The lack of an official sanction of women as gurus or central models of religious attainment has led to heated debates throughout the global ISKCON community for decades, even garnering international news coverage5. In 2003, the GBC’s Executive Committee appointed a group known as the Śastric Advisory Council (SAC) to research the precedents and scope for “female diksha-gurus,” the technical term for those who bestow initiation and are officially recognized by ISKCON in their Gauḍīya linage. Reflecting ISKCON’s grounding in a Gaudiya Hindu scriptural corpus and the teachings of Bhaktivedanta Swami, they consulted textual sources ranging from core Vaisnava texts such as the Bengali Caitanya Caritāmṛta to broader Hindu scriptural sources, including the Laws of Manu, which Bhaktivedanta quoted in his discussion of ideal gender norms for ISKCON. Although there have been premodern precedents for female gurus in Gaudiya communities, ISKCON interpretations are tightly tied to Bhaktivedanta’s words6. As “founder-ācārya,” the term employed by Bhaktivedanta to describe his seminal institutional and religious role, his translations and personal writings continue to hold inviolable status for determining ISKCON’s orthodoxy. In 2022, after more than two decades of debate, the GBC finally declared support for the possibility of female diksha gurus within ISKCON. This decision took into consideration historical examples of female gurus in Gauḍīya texts and memory, as well as an earlier conclusion of “orthoprax” legitimacy by the SAC.7 However, it was not these conclusions, nor the widespread enthusiasm for the inclusion of women as gurus in the global society, that tipped the final decision. Rather, the conclusion rested heavily on a brief recorded conversation with Bhaktivedanta about the matter, in response to a question put forward by the scholar of Hindu studies Joseph O’Connell. The conclusion: there can be female gurus but “not so many”.8 This abiding weight placed on Bhaktivedanta’s interpretations and specific choice of language, in even the most informal circumstances, guides official ISKCON policy through the bureaucratic arms of the GBC. Through their decisions, mediated through ISKCON’s online news forums and temple communities’ publications, interpretations are enforced and disseminated throughout ISKCON temples and centers worldwide.

During a brief trial period in 2021, a handful of elder women in ISKCON were put forward as the pioneer female gurus in the institution, with jurisdiction to initiate disciples in North America and Australia—regions that had affirmed support for the decision.But in 2022, a sustained resistance from several groups related to ISKCON’s Indian Bureau compelled a divided GBC to place a moratorium on women accepting disciples.9 This speaks to underlying tensions about differing gender norms between the Global North and South in the international organization. Yet, curiously, in the multiethnic, international landscape of ISKCON, some of the most influential advocates and detractors of women’s religious leadership have been white Western men residing in India. Further, this institutional resistance is also curious given the prominence of women teachers in many other Indian Hindu communities and the support from other contemporary Indian Gauḍīyas.10

This resistance to female religious authority is made more complex by the place accorded to female identity in Gauḍīya notions of religious perfection. Early Gauḍīya texts abound with fertile resources for complicating any straightforward patriarchal notion of gender and religious identity. In hagiographies and sādhana, religious practice, developed in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, followers aspired to emulate the gopīs, or cowherd maidens of Vrindavan, as ideal practitioners of Krishna bhakti. This emulation was not merely symbolic but rather grounded in the assertion that each jīva possesses a siddha rūpa, or perfected form, that, for Gauḍīyas, culminates in the form of the gopīs. Through the attainment of Krishna bhakti and transcendence from the world of saṁsāra, the formative generations of respected Gauḍīya practitioners, many of them in male lineages of religious authority, are often affiliated with their perfected forms as these divine women (Holdrege 2015; Stewart 2010). The practices surrounding siddha deha, or the revelation of one’s perfected form, became controversial in the reforms of early twentieth-century Gauḍīyas, particularly Bhaktisiddhanta, who removed the practice from standard institutional rituals. But the embodiment of the ultimate perfection for a devotee in the female form underlies Gauḍīya sādhana and many devotees’ ultimate aspirations. While traditionalist discourses assert a distinction between spiritual and social identities, thus bracketing these aspirations from a discussion of gender roles in everyday practice, these models of perfection are celebrated in the iconography of ISKCON temples and foregrounded in Gauḍīya ethical narratives.

Even barring this perspective, however, discourse and bureaucratic resolutions often do not reflect everyday experiences of mentorship and religious authority. The formal role of diksha guru is distinct from a less institutionalized role accorded to one who bestows religious guidance, sometimes deemed siksha guru, or teaching guru, in ISKCON’s Sanskritic terminology. Since siksha gurus are not formalized or legislated, their identities can extend beyond the formal requirements of diksha gurus, including male sex and shared religious lineage. Those in ISKCON who affirm women’s religious guidance in their lives have sometimes turned to this category to provide language to describe that relationship. It is here that women embody holiness for devotees in practice. This form of embodied religious attainment and the ability to guide others resonates with Joyce Flueckiger’s usage of the term vernacular to describe the “fluidity, flexibility, and innovation” of local South Asian religious practice that exists alongside discourses of orthopraxy—the former “shaped and voiced by individuals in specific contexts and in specific relationships” who change over time as their social contexts shift (Flueckiger 2006, p. 2). Antoinette DeNapoli has further built on this application to highlight the realm of vernacular religion as that “lived in dynamic and fluid ways, and in local, everyday contexts… through use of local idioms, metaphors, and categories of religious experience” (DeNapoli 2014, p. 28).

Models for women’s vernacular holiness are not in opposition to Sanskritic or brahmanical orthodoxy but rather often exist in conversation with it. Alongside the feminine connotations of śakti and goddess-centered traditions, female-centered holiness has also long resided in the concepts of satī and pativratā, ideals for the devoted and virtuous wife elaborated in both the Sanskritic religious narratives and ritual traditions. These models situate women within a patriarchal framework but also provide potent spaces for invoking authority and commanding respect if deployed strategically11. This is underscored in numerous popular stories, including the narrative of Savitri and Satyavan found in the Mahabharata, as well as in the ritual culture of vows, vratas, such as the North Indian Karva Chauth vrata. Such established models for feminine holiness often render the devout and virtuous woman as devi, or the divine feminine, asserting a power in such a woman’s actions that can even turn the tides of the natural world, compel the dead to once again live, and shift the fortunes of her and her family. These ideals underlie ISKCON’s communities alongside Gauḍīya-specific religious aspirations, which also celebrate historic female religious teachers and exemplars of practice in a devotional context.12

In this article, I build on this usage of vernacular religion by Flueckiger and DeNapoli to employ two different applications of the term holiness. Reflecting the dual nature of religious authority in ISKCON—official and vernacular—I use holiness as both a signifier of seniority and official authority within the organization (a title, His Holiness, available only to male renouncers) but also as a more expansive concept of religious attainment. In Krishna bhakti networks, this lived religious attainment centers on the ability to teach the path to devotion and self-realization (terms common in devotee circles), embodying and passing on the community’s ideals. With this background in mind, I now turn to ask: How do devotee women embody vernacular holiness and teach that path to others, irrespective of whether they can claim the title of guru or formal renouncer? How are they fashioning roles as religious authorities in community spaces and beyond them? While titled holiness is often out of reach, what vernacular forms of religious attainment do they embody?

3. Ask Mataji: Vernacular Religious Guidance in Visakhapatnam

Although the formal roles of guru and sannyasin are not available to them, women in Indian ISKCON communities do occupy positions of religious authority. Individual women have attained prominence as popular public speakers and siksha gurus. A particularly notable figure is Nitaisevini Mataji, whose YouTube channel posts videos of her religious lectures and updates on her travels to 132,000 subscribers.13 Born in Mumbai into a Gujarati business family, she became acquainted with ISKCON after her family later moved to Hyderabad. Like many ISKCON devotees of Gujarati heritage, prior to joining her family, she followed the Pushtimarga (an early modern Krishna bhakti community that developed in North India parallel to the Gauḍīyas), and, thus, she was already oriented towards Krishna devotion. Nitaisevini’s lectures reflect an impressive range of fluency in Bengali, Hindi, Gujarati, Telugu, and English and can be found on YouTube and through ISKCON Desire Tree, a digital archive that uploads media content from Indian temples.14 Like many religious teachers in Indian ISKCON promotional material, Nitaisevini’s public profile notes both her religious identity and educational attainment. Although her legal name is not given in media productions, her devotional name (bestowed at initiation by the diksha guru) is often prefixed with Dr., and her online biographies note that she completed a PhD in Education from Andhra University. Within ISKCON, she is centrally known, alongside her husband Samba Das, for developing the ISKCON temple in Visakhapatnam from 1999. With Samba as temple president, the pair currently lead the community from the temple’s location on Beach Rd. in the Sagar Nagar neighborhood, directly across from the scenic coastline of the Bay of Bengal. She is known simply as “Mataji” among many devotees in Visakhapatnam, a title that conveys a respect accorded to elder women generally but also points to her centrality as the presiding matriarch of the community.

Mataji’s religious and professional attainment both contribute to her influencer status in ISKCON networks and beyond. Her training in education set the foundation for opening the Divine Touch School, a Montessori-inspired preschool and early grade school for children between the ages of 2–10 (through Class V) founded in 2011. Originally connected to ISKCON, the school operates independently today, with Mataji as its principal. Within ISKCON’s religious networks, Mataji is a disciple of Jayapataka Swami, a prominent sannyāsi of white American origin who has been a leader of ISKCON in Mayapur, West Bengal, for decades. Alongside the pilgrimage city of Vrindavan, Mayapur is a central pilgrimage site for ISKCON devotees globally. Jayapataka Swami is also notably one of the several ISKCON gurus who advocated for women to become diksha gurus, following the initial GBC resolution reached in 2019 at a meeting in the Vaisnava pilgrimage town of Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh—a site that underscores respect for tradition.15 Beyond her prominence in Visakhapatnam, Mataji’s visibility as a religious leader is highlighted by her membership in the ISKCON Leadership Sanga (ILS), a group based in Mayapur that seeks to curate “ISKCON’s premier gathering of present and future leaders from around the globe”.16 She was one of several women to speak at the organization’s February 2023 conference. Her topic, “How to Be an Effective Srimad Bhagavatam Speaker,” referred to the standard daily lecture held at ISKCON temples every morning that is centered on a rotating verse from the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, a Sanskrit text that is a central scripture for ISKCON’s Gauḍīya lineage. Throughout most temples globally, apart from temples in the Global North, the daily Bhagavatam lecture is generally delivered by a male devotee, including, notably, at the site of the leadership forum in Mayapur.

In her talk at the ILS conference, held in a conference room in the Mayapur temple complex, Mataji advocated for the importance of both hearing and transmitting religious teachings. Speaking in English, she referenced the classic Gaudiya processes of bhakti, śravana, kīrtana, and smaraṇa, or hearing, reciting, and remembering: “If we don’t remember Krishna, we become a re-member of this material world…our going back home, back to Godhead is largely dependent on our receiving the blessings of the Vaisnava ācāryas. And Srila Prabhupada wants us to preach… [he] said ‘ISKCON means chant Hare Krishna, preach Hare Krishna’”.17 These references underscore accepted community notions of the centrality of preaching, or conveying religious teachings, to one’s personal progress in bhakti. She connects that to continuing the Vaisnava lineage, or paramparā, through receiving blessings of the ācāryas. In ISKCON religious aesthetics, this lineage is often represented as a line of male gurus. However, in popular conceptions of how Krishna bhakti is achieved, official status seems eclipsed in relation to personal devotional attainment. Mataji drew an example from her childhood to underscore this:

I remember when I was a young girl and when somebody’s getting married or something, our only service was to stand by the gate and sprinkle rosewater on people. But I remember when we keep doing that sprinkling of rose water, it gets sprinkled back on us. And after some time, we smell of rose. So, when we start speaking about Bhagavatam and we start connecting people to Krishna, we get connected to Krishna so strongly. If we give Krishna, then we get Krishna.

By contrast, she also warned that if devotees are not “qualified speakers” and fail to make their audiences “qualified” to convey the teachings further, “then the whole paramparā will be vanished”. She nuanced this warning with a passing reference to her South Indian upbringing: “I have seen in South India there were some amazing-amazing, big-big gurus, but after they left their legacy is not continued. Because they did not produce or they did not make qualified students”.19 Through these comparative examples, Mataji explicitly includes herself and other devotee women in the audience as partakers in the lineage through their ability to both model and teach Krishna bhakti.

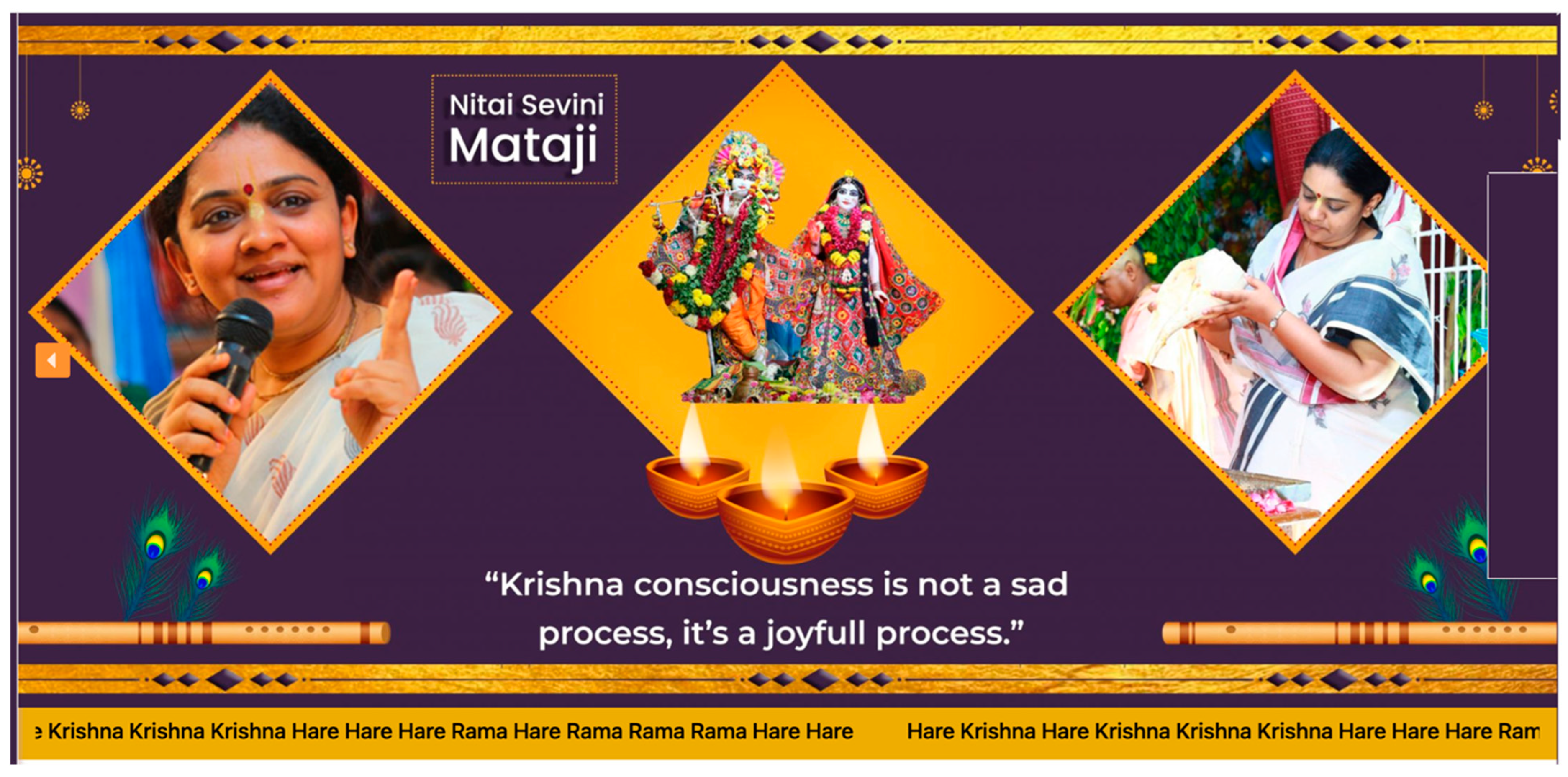

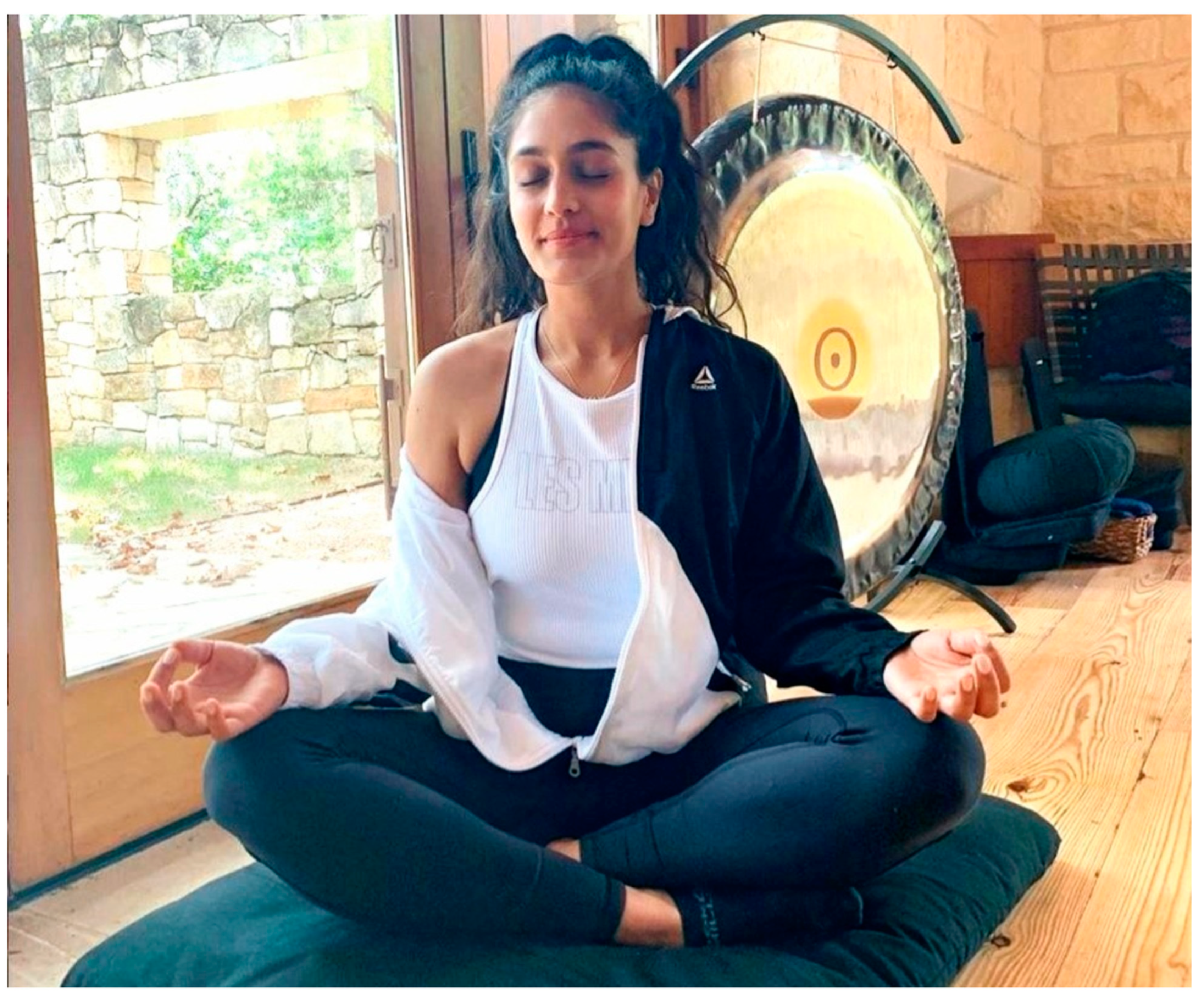

Mataji’s visibility as a religious teacher is most evident in her online presence, where her modeling of vernacular holiness is developed. Mataji’s polished personal website shares images of her that reflect mainstream devotional Hindu guru aesthetics.20 Not unlike the aesthetics of websites highlighting prominent female gurus, such as Amma in Kerala,21 Mataji’s website conveys the confluence of religious messaging and refined web development teams (see Figure 1). In cover images and a rotating gallery of photos, she is shown sharing insights with audiences, smiling benevolently, and concentrated with hands folded in prayer.

Figure 1.

Nitaisevini Mataji’s website homepage. Copyright 2021 by Nitai Sevini Mataji. Used with permission.

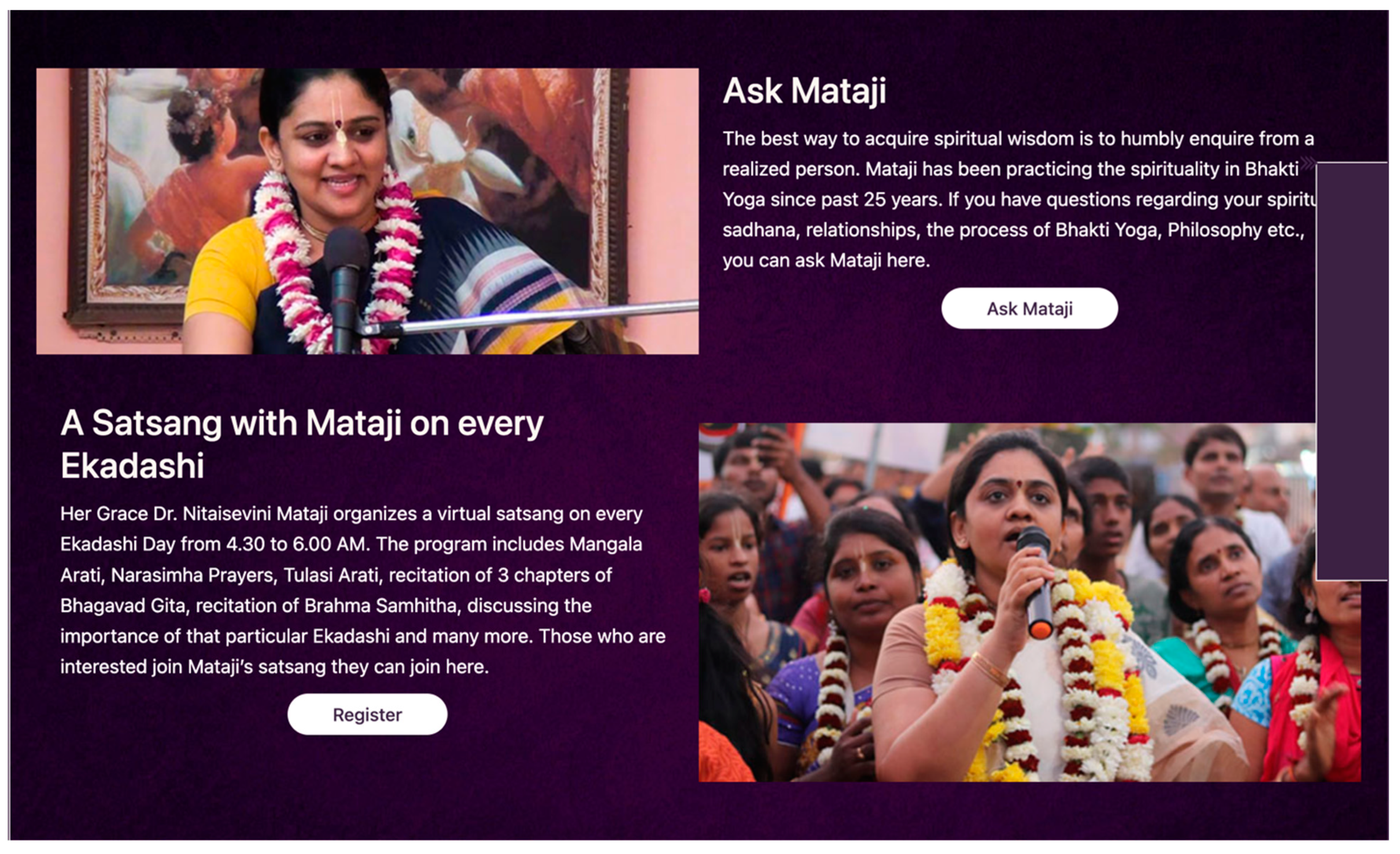

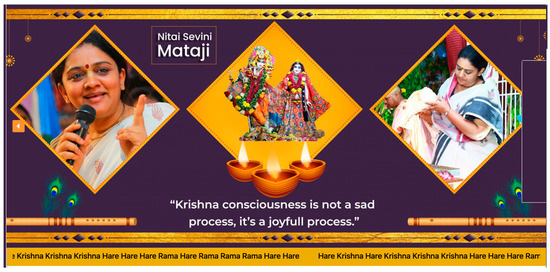

Her homepage also links to her Facebook feed and displays new content almost daily. This includes links to videos of her lectures and select quotes set against images of her speaking to a crowd or performing devotional temple worship. Amidst links to her recent workshops and motivational public talks, visitors can attend a virtual satsang that she leads every fortnight, on the Ekadashi day, according to the Hindu ritual calendar (Figure 2). This satsang takes online participants through the maṅgala ārati, early morning chants conducted in ISKCON temple settings, along with the recitation of several chapters from the Bhagavad Gita and other Sanskritic texts. A prominent link on the homepage also prompts visitors to “Ask Mataji,” explaining that “the best way to acquire spiritual wisdom is to humbly enquire from a realized person. Mataji has been practicing the spiritual in Bhakti Yoga since past 25 years”.22 A link takes seekers to an online portal to pose their questions, including on the suggested topics of spiritual sadhana, relationships, or the process of bhakti yoga. In these virtual forums, Mataji is the central model of holiness portrayed. She explicitly references bhakti yoga, and her media products are connected to the official umbrella of ISKCON Visakhapatnam, but she is the visible model of both religious attainment and the ability to convey that to others.

Figure 2.

Mataji’s website. Copyright 2021 by Nitai Sevini Mataji. Used with permission.

In addition to this centralized website, Mataji’s influence expands throughout YouTube and Instagram. On several occasions over the past few years, including her birthday and Guru Purnima, the annual celebration of the guru for Gaudiya communities, a montage of her images with devotional music has appeared in homage to her. Produced by devotees in Visakhapatnam and posted on her social media feeds, these videos are “dedicated to our dearest Siksha Guru”.23 This active role of guru—as model and teacher—is further highlighted on her Instagram account, @nitaisevini, which shows a recent temple tour that she took with her husband in January 2023 to Singapore, Malaysia, and Australia, including images of religious lectures she delivered to predominantly Indian diaspora audiences. Mataji’s visibility marks a new and exceptional area of growth for devotee women in India, buoyed by the accessibility of online spaces to fashion public identities that can extend beyond individual temple communities and garner wider followings.

However, while Mataji has come to occupy a prominent influencer position online and in an international network of ISKCON communities, she embodies this role not as a diksha guru but alongside affirming patriarchal social and religious ethics. Among her most-watched YouTube videos, garnering hundreds of thousands of views, are Bhagavatam lectures in Hindi that discuss ideals for women and married couples.24 In one, entitled “Ideal Women,” delivered (virtually) to a girls forum in Bikaner, Rajasthan, in June 2021, she begins by reciting a verse selected for the occasion (1.10.16) and reading Bhaktivedanta’s translation and published commentary.25 The verse and commentary highlight the quality encompassed in the Sanskrit word vrīḍā, “shyness or bashfulness,” and describe this as an ideal feminine characteristic. Drawing from the Hindi commentary, the vernacular term Mataji uses is lajjā, translated often as modesty but also shame. In unpacking the implications of this ideal for women, Mataji criticizes the modern industrialized economy for creating socio-economic conditions that threaten a traditional joint-family structure and the fabric of Indian culture (bhāratīya samskriti). While she notes śastric examples of women working outside the home in a premodern context, she disparages forms of modern work that separate people geographically from the family home and immediate neighborhood, due to dangers of “free mixing” with members of the opposite sex. She also discusses marriage at length, celebrating a model of receiving blessings from parents before marrying and critiquing a social situation in which women seek “independence” or “freedom” from their natal and marital family.26 Additionally, in a discussing a common problem devotee women face in India—a husband not interested in joining ISKCON and abiding by its lifestyle prescriptions, including vegetarianism—she advocates that women should not try to prescribe his behavior but to influence through performing one’s household duties with love. She advocates using one’s home as a “training ground” or a series of “tests” to refine your character (cāritra) and develop the qualities of humility, submission, and devotion needed to enter Goloka Vrindavan—Krishna’s divine abode, the ultimate Gauḍīya spiritual destination.

In her public role as the wife of a temple president and an advocate of traditionalist gender roles, Mataji thus solidly reflects ISKCON’s conversative ideals within contemporary Indian society. Yet, her visibility as a teacher and model of religious attainment conveys a vernacular model of holiness—one that is augmented by her expansive social media presence and popularity among ISKCON communities in India and abroad. Mataji’s vernacular holiness is grounded in an affirmation of the auspiciousness of performing traditionalist feminine roles in a Hindu Indian context. However, she posits those roles as a vehicle for devotional progress toward the goal of Krishna bhakti, as well as the basis on which to develop personal qualities held as ideals for all devotees. They are useful inasmuch as they can transport one to ideal religious destination. Indeed, on her website and YouTube channel, lectures on Krishna līlā and broad-based exhortations to increase introspection and refrain from criticizing others—relevant to audiences of all genders in her impressive multilingual range—dominate her popular persona as a religious teacher.

4. Chetana Festival Programs: Guiding Young Women, Modeling Holiness in Mumbai

Such a prominent public role as influencer is not the norm for most women within ISKCON communities. However, spaces for modeling and teaching vernacular holiness exist in the core structures of these communities. Turning to ISKCON’s temple communities in Western India, perhaps the most salient space for this is in the local pastoral care structure known as the Counselling System. As the core religious infrastructure for the thousands of devotees spread throughout the Mumbai metropolitan area and beyond, the Counselling System pairs younger devotees with, generally, elder couples who can guide them in their religious practice and any personal or societal issues they may encounter. As many devotees in Mumbai join ISKCON from Hindu and Jain backgrounds that are often less religiously conservative, this guidance often centers on how to adopt the mandates of ISKCON membership, including two hours of daily mantra meditation, vegetarianism, abstinence from intoxicants, including alcohol and caffeine, and—for many—the avoidance of secular forms of entertainment in favor of religiously centered events. As I witnessed during my research, the guidance of women counsellors was often central to the daily lives of many younger devotees—women and men.27

Among four Mumbai-area ISKCON temples, women in Mumbai’s Chowpatty temple community also organize city-wide events including drama festivals and “values-based” extracurricular programs for high school students throughout the city. Young women and girls affiliated with the Chowpatty temple have even taken center stage as actors in the community’s annual public Drama Festivals, in which they have embodied not only female figures in the Krishna bhakti religious worldview, including Radha and the cowherd maiden gopīs, but also the male deity Krishna and related male deities.28 Albeit a subtle form of religious authority, the space of performance does confer authority to pass down sacred narrative traditions as an embodied way of knowing. In the analysis of Vasudha Narayanan, women’s dance and performance in Hindu religious contexts engender both sights of piety and sites of power (Narayanan 2003). These embodiments also provide a striking contrast to the all-male Krishna līlā groups that have traditionally embodied religious presence for devout audiences in Vrindavan and elsewhere in North India.

In tandem with these sites of embodied vernacular holiness, the Chowpatty temple hosts monthly programs oriented towards girls and young women in the community called the Chetana Festival of Joy. Chetana (lit: “consciousness”) programs parallel the monthly Prerna (lit: “inspiration”) festival, aimed at young boys and men, and both are organized through the temple’s ISKCON Youth Services (IYS), an administrative division run by resident brahmacārīs and laypeople on the temple staff. Although many IYS programs are targeted to young men, including college-based missionizing programs, Chetana is an exclusively all-women space. The Chetana program organizers describe these events as a “protective buffer” between young girls of the congregation and secularized modern lifestyles in Mumbai, which the temple community codes as “Westernized” and distracting from a life of Krishna consciousness. They are deliberately held on Saturday nights to channel girls’ weekend activities away from parties and secular pursuits. However, they draw in their mostly teenage audiences by centering their program themes on subjects relating to popular entertainment and local youth cultures. Accordingly, programs address current events and respond to skepticism towards religion and piety that young devotees navigate among their peers. They also showcase ideals for women’s holiness in the temple community, as they are led by devout women who embody religious attainment and guide others towards ideal conduct through their public lectures.

Chetana programs begin with a kīrtana, devotional singing, led by a small group of young female devotee musicians. This is the first opportunity to imbue the space with an aura of holiness, demarcating the program as a space of devout focus and reflection through the reverberation of the sacred sound of communal mantra chanting. After the audience is settled, a play or skit is written and performed by teenage girls in the congregation. The skits are short, original productions, including homespun costumes, and they are developed collaboratively to match the themes of the speaker’s lecture that day. The main event of the lecture, generally lasting an hour, is delivered by a senior female devotee in the congregation.

The Chetana program can provide many things for young women, from causal socializing and something to do on a Saturday night, to guidance on one’s sādhana and practice of bhakti, to—most explicitly—directions towards a life in line with the conservative norms of the community amidst their urban context. The programs convey the clearly stated agenda of instilling traditionalist values and piety in the audience through connecting Gauḍīya bhakti ideals to contemporary concerns. Recent titles include “Spiritual Romance,” “Femininity vs. Feminism,” “Harness Your True Potential,” “Your Success GPS,” and “‘Booster Shots’-The Science of (H)A-BIT”. Lectures seek to head off competing ideologies in their young religious aspirants (such as feminism or the ideal of romantic love) and give attention to one’s individual mental and emotional wellness. In form, they reproduce the standard model of an ISKCON temple lecture, interweaving an eclectic mix of religious teachings, personal anecdotes, and instructive stories drawn from Hindu scriptural texts as well as popular culture. In the interpretations of the Gauḍīya tradition emphasized in the Bhaktivedanta-Radhanath line, core theological concepts about karma and reincarnation, a theistic worldview centering around Krishna, and the process of bhakti are discussed alongside a strong focus on personal character, centering on the values of humility, selfless action for others, and personal responsibility. The surrounding context of Mumbai also filters into the lecture’s eclectic teachings, as speakers often illustrate a point by referring to the Mumbai Local train system—the main form of commuter transportation for millions of city residents—or life in the city’s varied neighborhoods, and the formal English of the lectures is peppered with joking Hindi asides and references from Bollywood films.

The Chetana programs are held in a temple lecture hall or the main temple room when there is no overlap with the boys’ Prerna program. Although, as they pivoted to online spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic, this enabled an expansion of audiences through an increased posting of Chetana lectures to YouTube. This social media integration expands what had traditionally been a temple-based live program to the space of online religious influencer culture, as Chetana lectures sit alongside suggested videos by prominent Hindu gurus in YouTube feeds. Throughout 2021, Chetana programs were broadcast live on Facebook Watch and available for later viewing. While senior women still delivered the lectures, in these online events, teenage girls took the helm, moderating even more than in previous temple-based events, as well as centering the female-led kīrtana. This foregrounds the faces and words of these girls, enabling them to take roles usually occupied by senior male devotees in temple contexts. While Chetana programs resumed a regular in-person form in 2022, many programs continue to be broadcast on Facebook Watch, garnering between one and four thousand views per program. In the vast world of online religious programming, this suggests that their scope remains within a largely local Mumbai-based ISKCON viewership. Nonetheless, this online availability changes the process through which viewers access this content and opens it to a wider public audience.

One regular Chetana speaker is Dr. Sandhya Subramanian, known in ISKCON by her devotional name of Sita.29 Promotional material for the Chetana programs emphasizes both the religious and professional qualifications of the speaker. Sita’s devotional name appears above her title of Dr., with her legal name and degrees attained (B.D.S. Ms in Psychotherapy and Counselling) below. With her qualifications established, speakers like Sita inhabit the vyāsāsana during their lectures, a symbolic act of embodying religious authority. In ISKCON temples, the vyāsāsana is a raised seat with bolster cushions, perched in front of the temple room, positioning the speaker within view of the deities on the altar and towards the audience. Evoking the name of the preeminent Hindu sage, Vyāsa, who is said to have compiled the Vedas and formalized major canonical Hindu texts, this seat represents the authority of speaking religious truth, connecting the speaker who sits on it to a lineage of gurus of the past. As noted above, outside of Western countries, women do not regularly sit on the vyāsāsana to give public lectures to the temple community, except during visits of an elder female devotee from abroad. This gendered relegation is reinforced by a widespread discourse that gender equality is a modern, corrupting influence from the West and threatens ISKCON’s attempts to instantiate “Vedic” or traditionalist Hindu culture in its adherents. The Chetana class is a prominent exception in this ISKCON temple, then, in which women occupy the vyāsāsana and invoke their religious lineage to model and communicate guidance to their audience.

Although this may be seen as a circumscribed place of religious authority in relation to a broader, male-authority-dominated community, it is a palpable embodiment of holiness for the women who deliver these religious lectures. This is underscored by the rituals surrounding lecture delivery in ISKCON contexts, beginning with the recitation of praṇāma mantras, or invocation prayers. Therein, the speaker repeats a series of Sanskrit verses that offer respects to Gauḍīya teachers of the past and to one’s own guru, with the purpose of imbuing the speaker with the authority of the lineage to convey the teachings of Krishna. Beginning with celebrating one’s guru for opening one’s eyes with the light of knowledge, the prayers go on to offer respect to one’s personal guru and all other preceptors on the path of bhakti. Following the style and cadence of Radhanath Swami that has become popularized among his followers, many speakers linger on these prayers, taking care to feel the import of their invocation of past gurus and ācāryas (lineage heads) to imbue their words with religious truth. In Chetana lectures by Sita, she provides a particularly vivid example of this. A space of sacrality is created as she folds her hands together in the namaskar gesture, closing her eyes and slowly intoning the verses with focused concentration (Figure 3). At times, speakers employ a harmonium, with an accompanying mṛdaṅga drum and kartals, brass cymbals, and draw out each key to match the focused, prayerful invocation of each praṇāma verse. The melodic cadence of the Sanskrit verses themselves demarcate the space for the communication of religious guidance. Speakers conclude the prayers with the Hare Krsna mahā-mantra, which, for devotees, imbues the space with a transformative spiritual energy.

Figure 3.

Sita recites the praṇāma mantras on the vyāsāsana, Chetana lecture at ISKCON Chowpatty, 8 February 2020. Copyright by Radha Gopinath Media–ISKCON Desire Tree. Used with permission.

Alongside owning their place on the vyāsāsana, humility is prized according to the etiquette of this temple’s culture, and this is expressed by many of the speakers in their modeling of religious attainment. In a recent lecture, another popular speaker, Kalindi, reflected on this by the caveat: “I’m not a very expert speaker but whatever I have heard from my Guru Mahārāja and from other devotees, I will try to reconcile and speak something on this topic”.30 Although self-effacement, this also communicates a commitment to convey the teachings of her lineage, alongside an acknowledgement of personal humanity in its imperfection.

What does imperfection have to do with holiness? The ideals invoked by those sitting on the vyāsāsana are mediated through their diverse personalities and approaches to religious guidance. In contrast to Sita’s model of holiness as formal composure, other speakers, such as Radharani, offer an off-the-cuff directness and the no-nonsense approach of a personal pep talk.

In a Chetana lecture entitled “Who’s Responsible?,” Radharani disarmingly unpacks an issue of everyday psychology and behavior, discussing how we respond to challenging events (Figure 4). With a generous but seasoned tone conveying “you can’t get anything past me,” she encourages her audience to steer clear of adopting the identity of a victim and blaming others. Rather, she advocates for being proactive in one’s ability to respond (“being response-able”) in a way that does not generate more karma and instead moves one towards higher states of life:

So, what do we do? Do we just sit and say: ‘this is my karma; I must accept it.’ No. We are not fatalistic, but we are proactive. We think ‘whatever I need to do, I have to do’… whatever we can change, we try to change… but there will be situations that are beyond our control. Then what do we do? That is where our response comes into the picture. We blame or we tolerate. There is a saying: the greatness of a person can be estimated by how one tolerates provoking situations. You have to travel by Bombay trains to appreciate this, right?

Figure 4.

Radharani in her engaging, no-nonsense lecture style, discusses the theme “And They Lived Happily Ever After…” in a Chetana lecture, ISKCON Chowpatty, 15 December 2018. Copyright by Radha Gopinath Media–ISKCON Desire Tree. Used with permission.

Imparting a saying drawn from Bhaktivedanta’s writings and frequently employed by Radhanath Swami, her guru and leader of the Chowpatty community, she frames the religious topic of karma in a local context. Alongside her straightforward life advice, Radharani, too, models humility even from her position of authority on the vyāsāsana. At the outside of her lecture, she gives a caveat: “I will be saying we and you in the lecture… but don’t take it personally. Some of these things may not apply…When I speak, I generally speak for myself. I generally take a topic because I need to work on myself… and speaking to you all makes me more conscious about not making these mistakes in my life…”31 However, this display of self-effacement is a facet of the religious attainment Radharani wishes to convey. It models the ideals of “Vaisnava etiquette” that the training devotees undergo when they join the temple community, and humility is also distinguished as a sign of authentic advancement on the path of Krishna bhakti. In that sense, imparting one’s imperfections rather than perfections alongside a commitment to improve them has itself become a model of vernacular holiness.

Within Mumbai’s ISKCON communities, devotee women have come to occupy a prominent role in educational programs, as a backbone of religious missionizing. Women teachers are prominent not only in all-women spaces such as Chetana or only in relation to primary education—a traditionalist role for women in ISKCON circles, as in conservative groups broadly. Beyond this, devotee women have also become central in formulating and leading ISKCON’s adult religious education classes. This includes courses on temple sites, such as Chowpatty’s afternoon scripture and lifestyle courses, offered for both children and adults. Even through the female-specific forum of Chetana, the use of social media enables their religious messages to have a greater sphere of influence, leading to a widening of representation of women as religious teachers via Facebook and YouTube.

Within the Indian Hindu context, these models of vernacular holiness remain ensconced in the content of ISKCON’s Gaudiya philosophy and traditionalist aesthetics, including the visibility of saris, a bindi for married women, and the tilaka clay forehead mark, denoting status as a devout Vaiṣṇava. Invoking traditionalist feminine roles even as they present as authorities can function not as a deflection of influence but as a gendered modality of it—even a condition of it—within religious Hindu contexts. In the traditionalist model of a holy householder, wearing a sari or bindi and visual presence alongside one’s husband in public forums code women’s visibility as influencers within the rubrics of these legitimating signals. However, the sphere of these symbols is also complicated by combination with the list of professional degrees alongside one’s devotional title and by occupying the vyāsāsana, embodying religious authority in its most central and symbolic space within the temple context. These symbols have resonance as markers of tradition, even in modern Visakhapatnam and Mumbai. What about ISKCON influencers outside of India? How might one cultivate vernacular holiness if both Hinduism and its markers of holiness are not recognizable in mainstream social media cultures?

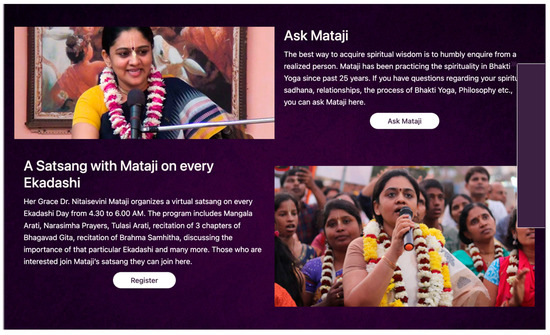

5. Urban Devi: American Vernacular Holiness

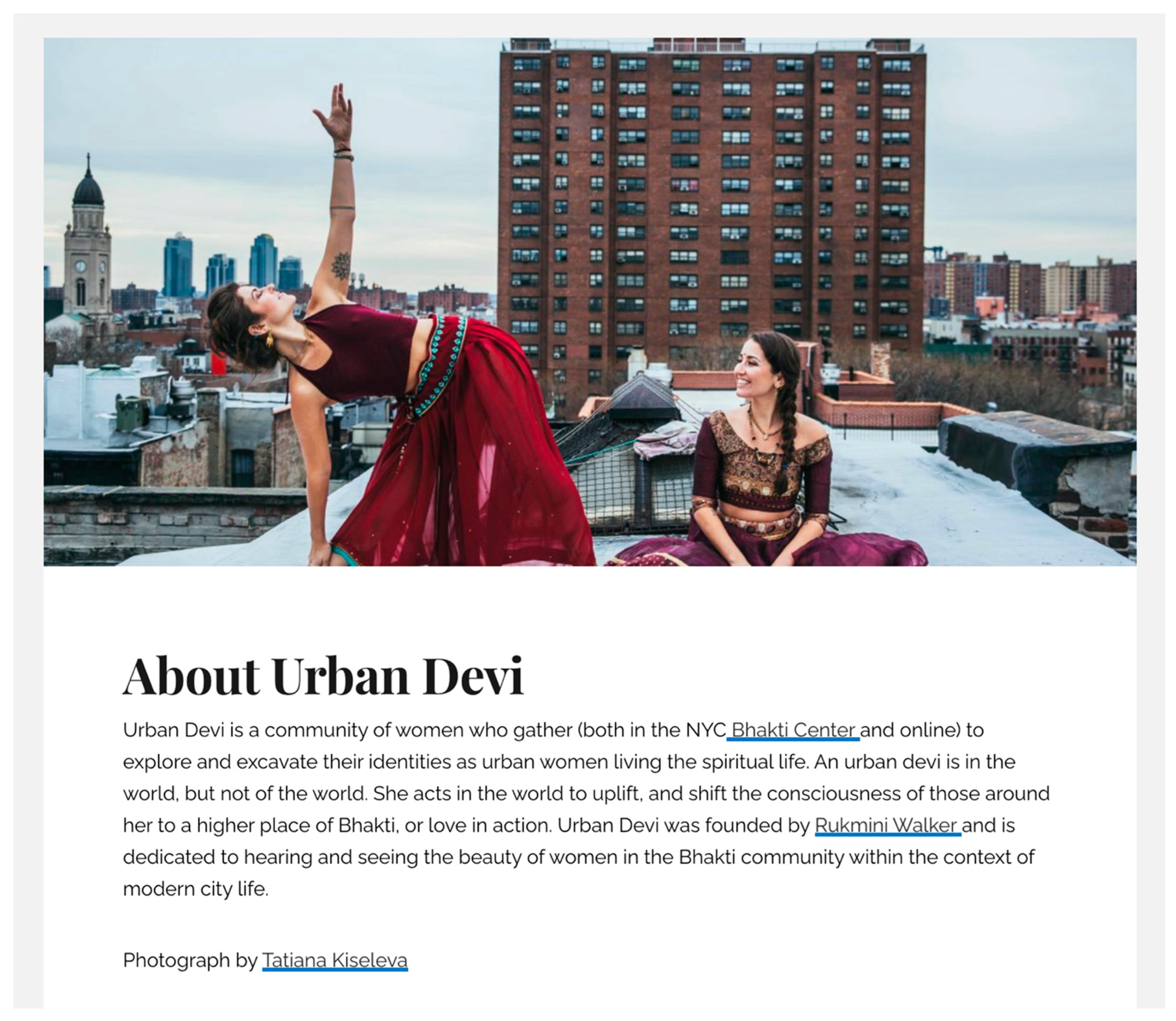

When considering holy women in ISKCON as influencers in the US, the first location one might look is Urban Devi—the inspiration for this article’s title—which is described on its website as: “a community of women who gather (both in the NYC Bhakti Center and online) to explore and excavate their identities as urban women living the spiritual life”.32 The founder of this group is Rukmini Walker, one of the first disciples of Bhaktivedanta Swami, who has been a revered teacher in ISKCON circles in the US and abroad for decades.33 Born Wendy Weiser in a white American Jewish family in the Chicago suburbs, Rukmini was initiated into ISKCON at the age of 16 and has remained a steadfast member since. Instrumental in developing the Montreal temple in the late 1960s, Rukmini later served in the Boston, New York, and Los Angeles temples as a pujari and spent extensive periods in India before coming to reside in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area with her husband, Anuttama Dasa, who is the international director of ISKCON Communications and a prominent member of the GBC. As a marker of her exceptional seniority within the organization, she is one of only a handful of women who have delivered the Bhagavatam lecture in ISKCON’s Vrindavan and Mayapur temples (and only then as recently as 2019). Rukmini has been siksha guru to many devotees for decades, and she is a central example of someone who would easily attract disciples were ISKCON to allow female diksha gurus. In that sense, her influencer status far precedes her engagement with online media.

Over the past years, however, her Urban Devi moniker has developed into a hub for devotees—many of them women—of all ages in the mid-Atlantic East Coast. In connecting Urban Devi with the Bhakti Center, an experimental ISKCON center in New York that pairs hatha yoga classes and a vegan restaurant with classes on bhakti yoga, Rukmini pitches her Urban Devi newsletters and events to appeal both to existing devotees and to those coming to Krishna bhakti from a background of interest in yoga or spirituality broadly. Resonant with the Chetana programs in Mumbai, but for a different audience, Rukmini emphasizes the urban context of her audience, underscored by the subheading of the website and related media products: conscious and contemporary. She fashions the ideal of this collective as follows: “An urban devi is in the world, but not of the world. She acts in the world to uplift and shift the consciousness of those around her to a higher place of Bhakti, or love in action”. (Figure 5)34 Toward this end, Rukmini leads monthly online sangas and more frequent virtual events in between, often welcoming other devotee women as guest speakers.

Figure 5.

The “About Us” section on the Urban Devi website. Copyright 2023 Urban Devi.

Sanga topics convey a form of religious attainment that is explicitly tied to Krishna bhakti—underscored by reference to Vaisnava festival days and the goal of Krishna consciousness. The range of topics discussed also conveys vernacular ideals of attainment that resonate with a broader focus on mental health and wellness. Recent speakers at this virtual sanga have discussed how to have healthy relationships, as well as strategies used by a licensed psychotherapist “with a holistic approach to mental health care” and advice from an herbalist on “bringing our consciousness of light into [the] dark spaces” of the winter season. An established, elder female devotee within ISKCON who has also been an active member of interfaith circles in the Washington, DC area since the 1990s, Rukmini has cultivated a model of religious attainment that is ensconced in ISKCON’s notions of holiness but also recognizable in broader interreligious and wellness registers.

Amidst this range, however, Rukmini’s influencing is solidly positioned in her own religious lineage. Her media products pivot towards a broad audience but center on the religious focus of bhakti. They do not explicitly invoke an institutional affiliation—and, indeed, the choice to align with the Bhakti Center and not an ISKCON temple notably expands Urban Devi’s scope beyond conventional missionizing initiatives. However, the visual culture of her website, the identities of most of her guests, and her own explicit identification as a practicing devotee and disciple of Bhaktivedanta connect her social media presence to an institutional base. This has been reiterated recently in several posts from February 2023, for instance, that conveyed elder ISKCON members’ calls to reinstate female diksha gurus. Regardless of the outcome of this institutional decision, Rukmini is already a revered teacher and model of devotion—a holy woman—for many devotees in the US and abroad. Beyond these developing spaces for explicit devotional influence online, another, more tenuous realm of Krishna bhakti in the social media influencer space is developing—one which challenges the boundaries of what holiness can constitute in an implicitly secular media space.

6. Recipes for Bhakti? Hints of Holiness in an Instagram Influencer

Radhi Devlukia-Shetty today inhabits a solid space within the South Asian American social mediascape. Both Radhi and her husband, Jay Shetty, have garnered prominent media profiles as entrepreneurs and influencers. Based in Los Angeles, Radhi is mostly known for her Instagram and TikTok presence, described in promotional material as a “Plant-Based Recipe Developer and Fitness & Well-being Enthusiast”. Developing media content that relates to vegan recipes, she draws on an Ayurvedic Health Counsellor degree from the California College of Ayurveda. Since 2021, she has leveraged increasing visibility in the online media space through daily videos and cooking segments bolstered by her production team. As of March 2023, according to her official social media profile numbers, she has garnered two million followers on Instagram and over 137 thousand followers on TikTok. Shetty meanwhile has become known as a self-help author and podcast host, most recently with a recurring segment on the Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Shetty’s book Think Like a Monk, published by Simon and Schuster, became a New York Times bestseller in 2020 and is on display at major bookstores in the US and UK at the time of this article’s composition. This power couple’s joint ventures of Sama Tea and JOYO sparkling tea, plugged on their social media pages and available for sale at Erewhon natural foods market in Los Angeles and online, help to “inspire and enhance both your body and mind” and “ignite the spark within”.35

Radhi’s TikTok account speaks to intersecting transnational networks of friends and culture. Both Radhi (born Roshni) and Shetty were born and raised in the northern suburbs of London and are both of Indian Hindu ancestry. What may not be immediately apparent to consumers regarding their online media presence is that they met through ISKCON and shared discipleship under Radhanath Swami, the resident guru at the ISKCON Chowpatty Mumbai temple. Both were drawn to the ISKCON in their college days and met through the Bhaktivedanta Manor, ISKCON’s sprawling Tudor style mansion near their family homes. The overwhelming majority of Radhi’s TikToks and Instagram posts do not reference religion, but some do engage with experiences of navigating Indian and Western cultures. These include cameos in formal South Asian attire and Bollywood-inspired soundtracks, choreographed dances with artist, friend, and fellow Londoner of South Asian descent Aadil Abedi, as well as comedic cultural critique. Frequent posts include voiceover skits with husband Jay Shetty, recipes for vegan salads, and product placements for JOYO sparkling tea. Thus, the media space Devlukia creates links geographic and cultural regions through her reference to American, British, and South Asian diaspora audiences but centers on a mainstream wellness-inflected entrepreneurial profile.

While Devlukia’s posts do not include overt mentions of religious practices, subtle traces of religious guidance are baked into her recipes. The dietary restrictions of ISKCON (shared by many Hindu and Jain communities) include vegetarianism, as well as the avoidance of garlic and onion, and Radhi’s recipes implicitly abide by these rules.36 Additionally, a quick reference to a ritual world beyond the recipe is hinted at the end, with her exhortations to say a prayer of gratitude before eating. This could easily be read in the world of wellness culture as a prayer directed towards “the universe” or generic affirmation, but for those who know, it can be read as a nod to the devotional practice of offering food to Krishna before consuming it, thus sanctifying it and rendering it blessed, prasadam. While no overt religious or ritual terminology is used, the brief reference to prayer imbues an otherwise secular mediascape with a hint of holiness.

Lightly peppered amidst entertainment and wellness-oriented content is the occasional subtle direction towards spirituality, with an implicit direction towards ISKCON-affiliated writers. Of note is the TikTok post entitled “5 Books that Changed My Life,” in which Radhi walks the audience through a translation of the Bhagavad Gita, a central scripture for ISKCON devotees and its parent Gaudiya Hindu tradition. In an approachable and nonchalant tone, she notes: “my mum actually gave me this book when I went to university and told me that if I ever felt confused, lost, or sad, I should just open up any page and it will give me some sort of solace”.37 Her next recommendations highlight contemporary ISKCON sannyasi authors, including Radhanath Swami’s autobiography The Journey Home and The Living Name: Chanting with Absorption by Sacinandana Swami, which Radhi credits with “changing her entire meditation practice” from “meditating pretty mechanically to feeling a genuine love and deeper connection with each chapter that I read”.

This content is exceptional in comparison to the broader, wellness-oriented messages that are much more characteristic of Radhi’s media profile. Many posts are aimed at the physical and emotional health of her audiences, including broad-based, affirmational advice or specific instructions on “how to drink water the right way,” drawing general principles from Ayurvedic teachings. Some affirmational posts do touch on self-reflection in a deeper mode, such as this monologue delivered in an Instagram reel:

How content am I feeling? And the way that I measured that is based on how much I want what other people have. And that was a really hard thing to get my mind around, because I was so used to constantly desiring what other people have… I had to differentiate that it’s not that I want to be them, it’s not that I want to even be doing the things that they are doing. What I was craving was that joy they are getting out of their success. And so as soon as I felt that in my life, I started desiring other people’s lives less. And that honestly has been my barometer of success.

Religious teachings were more overt in Radhi’s earlier online presence, particularly through her website. This content, created between 2020 and 2021, imparts a devout Vaiṣṇava image in aesthetics and written content. The photo montage on the homepage centers on Radhi dressed in a sari and tilak, embracing a cow, and explains her “conscious cooking philosophy”:

In the Vedic culture, it is believed that the mood, mindset, and energy of the person cooking is infused into the food and absorbed by the person eating it. So cooking with love and devotion and saying a little prayer before serving the food is such a sweet loving practice that has the ability to nourish not only the body, but the mind and soul too.

Further down the homepage, she invokes the words of Radhanath Swami, described as her spiritual teacher: “knowledge or skills are worthless unless they are shared and so this is just my little way of sharing what I’m learning with you all”.40

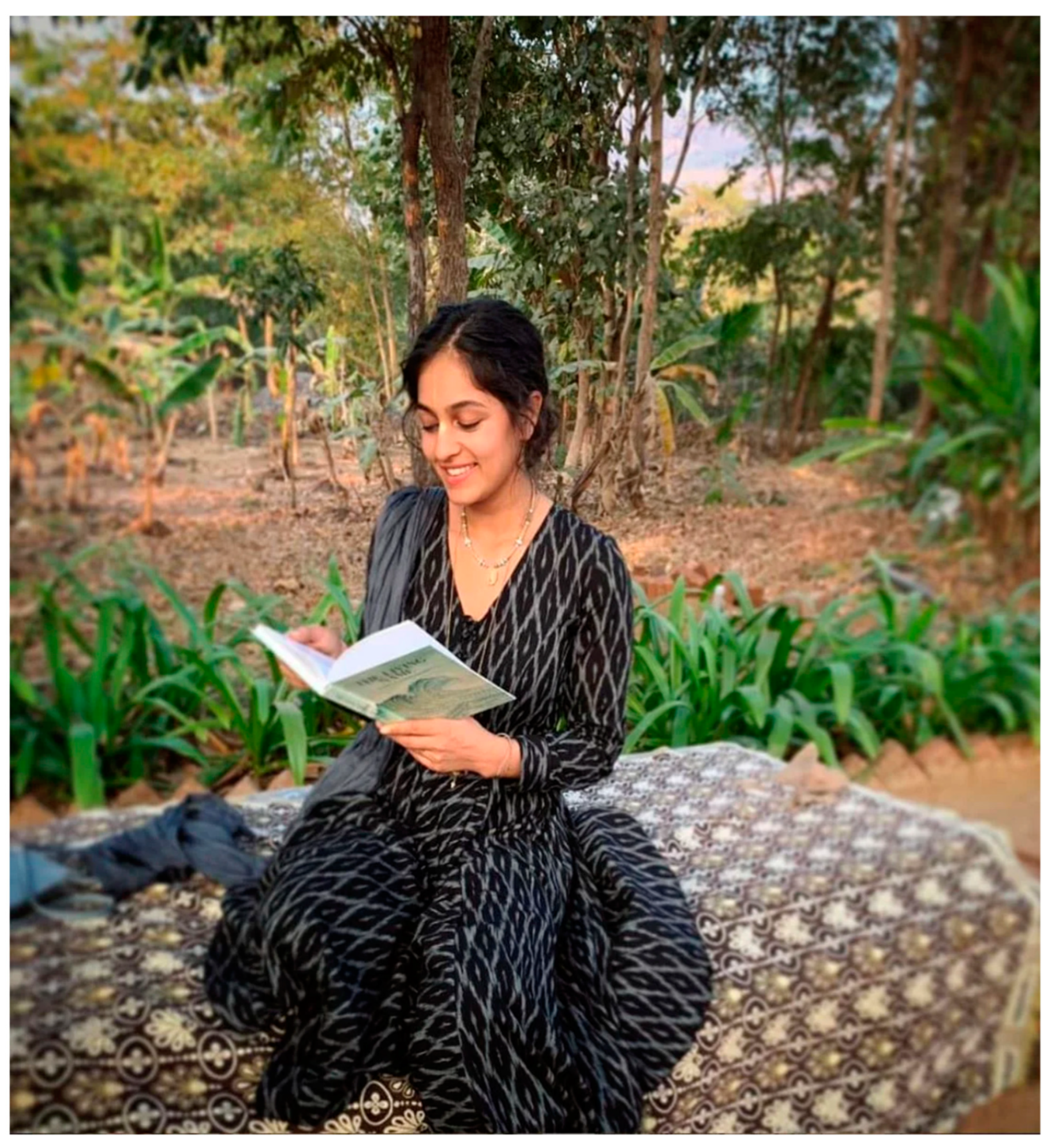

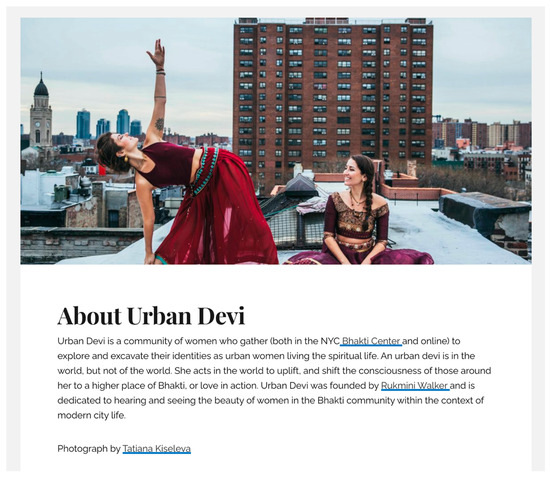

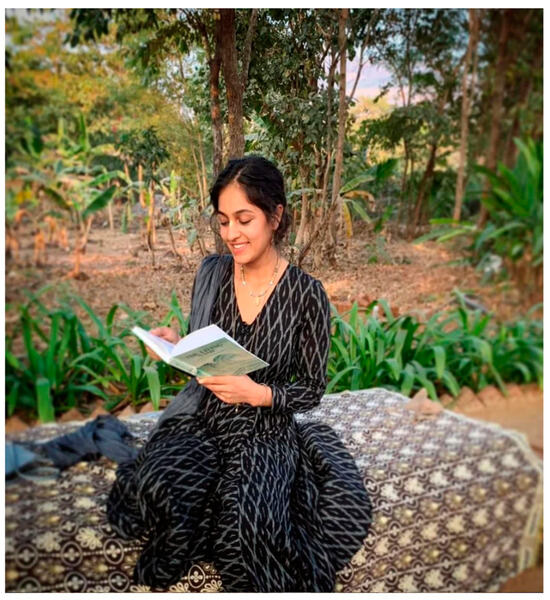

In a subsection of her website entitled “Nourish Your Soul,” overt religious influence is also conveyed. The aesthetics of those articles also provide a visual roadmap of the range of Radhi’s public profile: as a Krishna devotee, Ayurvedic recipe and lifestyle guide, and, most prominently, wellness-oriented influencer. In this section, she foregrounds references to Bhagavad Gita verses and discusses her personal spiritual journey.41 She describes a particularly devout period following college, during which she visited the temple daily for the maṅgala ārati service (generally held at 4:30 am) and performed her sādhana with the monks and other laypeople there before going to work. Finally, she describes the transformative experience of meeting her guru Radhanath Swami.42 At the bottom of this page, Radhi is shown gazing down at her copy of the Bhagavad Gita, attired in a long dress and dupatta scarf, with tilaka and tulāsi beads, a necklace worn by Krishna devotees that signals pious commitment (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Radhi Devlukia-Shetty, pictured reading the Bhagavad Gita on her “My Spiritual Journey” webpage, personal website. Copyright 2020 by Radhi.

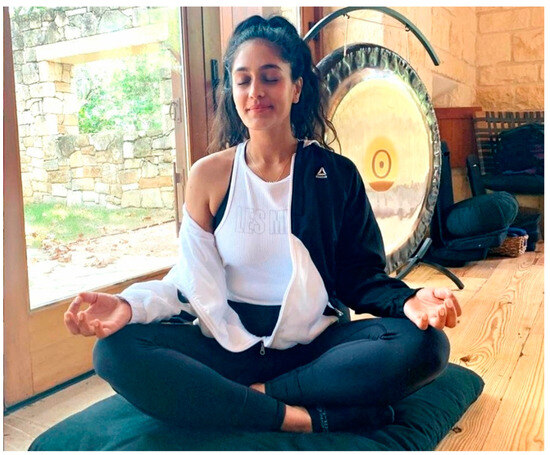

This image contrasts with the mainstream social media influencer aesthetics that she embodies on Instagram and TikTok. The link between these two realms seems symbolically made in one further article on her website, “FAQ about Meditation”.43 There, Radhi conveys a straightforward presentation of ISKCON’s mantra meditation practices, japa, including a word-by-word analysis of the Hare Krishna mantra. In japa, devotees audibly recite the mantra, counting beads with one’s right hand on a mala, which, by convention, is placed within a cloth bag. This distinguishes ISKCON’s japa practice visually from mindfulness-oriented meditation. Incongruously, though, the accompanying image of Radhi bears no overt characteristics of japa and instead reproduces the aesthetics of a stock photo of meditation in a Western mindfulness idiom. She is pictured seated with crossed legs in exercise gear, including leggings and a Les Mills tank top, with hands resting on her knees, eyes closed, and a subtle smile (Figure 7). A casual viewer would find this indistinguishable from an image that might appear on a mainstream healthcare website. However, far from a generic appeal to meditation as a vague practice for health and wellness, I read this image as engaging in a savvy form of online influencing. By echoing well-established aesthetics of Western wellness culture, Radhi is crafting an identity as a social media influencer that imbues these with reference to an actual religious tradition of which she is a practicing initiate. Although not at the forefront of her current Instagram and TikTok persona, these hints of vernacular holiness underlie her online presence.

Figure 7.

Radhi pictured in meditation, “FAQs about Meditation” webpage, personal website. Copyright 2020 by Radhi.

Radhi’s wellness orientation and religious grounding are more visibly aligned in her Komi webpage, a Los Angeles-based platform pitched toward influencers and celebrities as “the ultimate creator hub”. Although centered on her business ventures and collaborations (including the Radhi Weekender bag by the leather-alternative bag company Samara), videos teaching breathwork for anxiety, and vegan recipes, this landing page also includes a “Mantra Meditation Playlist” featuring contemporary music by ISKCON-affiliated artists, including Jahnavi Harrison, Gaura Vani (notably, the son of Rukmini Walker), and The Hanumen. This personalized display subtly weaves together a lifestyle image that pairs mainstays of wellness business empires—such as diet recommendations and minimalist accessories—with devotional compositions grounded in ISKCON’s bhakti networks.

Toggling worlds of religious practice and popular media cultures is an ever-evolving endeavor. In a recent cover story for Vogue India, Radhi is featured alongside her husband, Jay Shetty, to promote his book 8 Rules of Love. This round of publicity connects his public persona as a former monk and religious aspirant to the world of self-help and relationship advice.44 In an exceptional style choice for Vogue India, Radhi is featured with a subtle bindi and clothed neck to toe in a peplum cut jacket and voluminous embroidered skirt, showing markedly less skin than the publication’s typical cover model. In the cover story, their shared background in seva at an ashram is asserted as a “sense of purpose [that] still builds their common ground as a couple,” and Shetty’s wisdom is linked back to “copious study of the Vedas during his days as a monk”.45 Although these brief references to their religious context sit amidst an overall discussion of relationship advice, perhaps the embedded character of such religiosity is an ultimate sign of an influencer’s success. These markers of identity as Krishna devotees do not contradict their public influencer profiles. Rather, they preside at their foundation as pointers towards a world of religious practice poised for deeper examination by their viewers at large.

TikTok and Vogue are certainly not conventional spaces for Hindu religiosity. But in tying together the diverse women featured in this article, marked differences in public profiles nuance their portrayals of religious attainment and strategies for conveying knowledge through evolving online networks. Albeit articulated in various languages and aesthetic registers, a shared grounding in ISKCON connects their contemporary social media profiles. And a thread of vernacular holiness—as the palpable embodiment of an everyday practice of Krishna bhakti—provides new avenues for considering women’s lived religious authority and its scope, even in proximity to an institutional context in which it is officially restrained.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the existing affiliation information and to resolve spelling errors in Notes. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Notes

| 1 | A standard iteration of this approach can be found in the UK-based, ISKCON-affiliated Heart of Hinduism religious educational group, as summarized in their discussion of “Women’s Dharma,” which draws from statements of Bhaktivedanta, including his frequent reference to the Laws of Manu: https://iskconeducationalservices.org/HoH/practice/dharma/womens-dharma/ (accessed on 1 April 2023). |

| 2 | Gaur Gopal’s Instagram account (@gaurgopaldas) has accrued 6.7 million followers as of March 2023, and Gauranga Das (@officialgaurangadas), whose 741,000 followers can listen to talks, read quotes, and follow guided meditations through his Instagram profile. |

| 3 | See (Zavos et al. 2012) and (Brosius 2014) for considerations of this in comparative Hindu communities and Karaganagiotis 2021 for a recent consideration of media usage in ISKCON. |

| 4 | List of Initiating Gurus in ISKCON, GBC.org, https://gbc.iskcon.org/list-of-initiating-gurus-in-iskcon/ (accessed on 26 March 2023). |

| 5 | Jordan Blumetti, “‘It’s latent misogyny’: Hare Krishnas divided over whether to allow female gurus,” The Guardian, 4 June 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/04/hare-krishna-india-hinduism-florida-women (accessed on 28 March 2023). |

| 6 | See (Broo 2003) for a historic context of Gaudiya notions of the guru. |

| 7 | “Female Diksa Gurus in ISKCON,” GBC ISKCON.org, https://gbc.iskcon.org/female-diksa-guru/ (accessed on 31 January 2022). A summary of the Sastric Advisory Committee (SAC) and its research papers, as commissioned by the GBC, is available on the GBC’s website. |

| 8 | ISKCON News Staff, “GBC Amends and Affirms Law Allowing Vaisnavis to Initiate,” ISKCONNews.org, 22 December 2021, https://iskconnews.org/gbc-amends-and-affirms-law-allowing-vaisnavis-to-initiate/ (accessed on 24 January 2022). |

| 9 | ISKCON News Staff, GBC Pauses Vaishnavi Diksa Gurus, Again,” ISKCON News.org, 23 December 2022, https://iskconnews.org/gbc-pauses-vaishnavi-diksa-gurus-again/ (accessed on 28 March 2023). |

| 10 | Satyanarayana Dasa, head of the Jiva Institute of Vedic Studies in Vrindavana, weighed in on this discussion in a 2021 blog post that presented a scripturally grounded argument in favor of Gaudiya women gurus. “Female Guru,” Jiva: The Institute of Vedic Studies, https://www.jiva.org/female-guru/ (accessed on 13 March 2023). |

| 11 | See Sarkar (2001) for a historical treatment of how these ideals have developed in modern Indian contexts. |

| 12 | Thanks to both of my anonymous reviewers, whose suggestions added important framing to this section. |

| 13 | Nitaisevini Mataji (Official) YouTube page, https://www.youtube.com/c/NitaiSeviniMatajiOfficial (accessed on 30 March 2023). |

| 14 | Her Grace Nitaisevini Mataji, ISKCON Desire Tree personal page, https://audio.iskcondesiretree.com/index.php?q=f&f=%2F04_-_ISKCON_Matajis%2FHer_Grace_Nitaisevini_Mataji (accessed on 30 March 2023). The biographical information mentioned above can also be found at this site and on her YouTube page. |

| 15 | ISKCON News, “Vaishnavi Diksha Gurus in ISKCON,” YouTube video. 13 June 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-yXOU3clZ0s (accessed on 30 March 2023). This video celebrated this decision, renewed following further meetings in 2020, and was released strategically to communicate that this decision had the sanction of senior male sannyasi GBC leaders and gurus, with a focus on support in Indian leaders, including also the Indian-origin gurus Bhakti Charu Swmai and Gopal Krishna Goswami. |

| 16 | “ISKCON Leadership Sanga 2023 Announcement,” https://ilsglobal.org/about-ils/ (accessed on 31 March 2023). |

| 17 | “ILS Speakers 2023,” https://ilsglobal.org/sessions/ (accessed on 31 March 2023). The processes of bhakti Nitaisevini refers to are derived from the Bhagavata Purana 7.24. |

| 18 | See note 17 above. |

| 19 | See note 17 above. |

| 20 | Homepage, Nitaisevini Mataji.com, https://nitaisevinimataji.com/ (accessed on 30 March 2023). |

| 21 | For comparison, see https://amma.org/ (accessed on 5 June 2023). |

| 22 | Homepage, Nitaisevini Mataji.com, https://nitaisevinimataji.com/ (accessed on 30 March 2023). |

| 23 | Nitaisevini Mataji (Official), “Nitaisevini Mataji Guru Purnima iskcon vizag,” YouTube video. 7 September 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_XS80S_l67k (accessed on 30 March 2023). |

| 24 | Her most-watched YouTube video is “Ideal Grihastha Life (Hindi),” garnering almost one million views as of March 2023. |

| 25 | Nitaisevini Mataji, “Ideal Women (Hindi) by Dr. Nitaisevini Mataji (only for Matajis),” 11 May 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWWAHgteOMY (accessed on 30 March 2023). |

| 26 | In making these points, Mataji intersperses the English words freedom and independence into her Hindi discourse and draws on the critical approach to these concepts (and the project of women’s liberation and feminism broadly) that Bhaktivedanta developed in his writings. |

| 27 | This is detailed in my forthcoming book, Bringing Krishna Back: Global and Local Networks in a Mumbai ISKCON Temple, to be published by Oxford University Press. |

| 28 | One of several examples of this over the past few years is the play Bhatrol, performed at the Mumbai Drama Festival and posted on the RG Media YouTube page in 2020. |

| 29 | All initiated devotees receive a ‘spiritual name’ chosen by the guru and bestowed at the time of harināma initiation, or the formal vows in which devotees dedicate themselves to chanting the Hare Krishna mantra on the prescribed 16 rounds of their japa mala, prayer beads, and commit to ISKCON’s four regulative principles, of vegetarianism and abstaining from intoxicants, extramarital sex, and gambling. |

| 30 | Kalindi Mataji, “Overcoming Hopelessness,” 13 July 2019, Radha Gopinath Media–ISKCON Desire Tree, YouTube (accessed on 30 March 2023). |

| 31 | Radharani Mataji, “Chetana Festival-Who’s Responsible,” Radha Gopinath Media–ISKCON Desire Tree, YouTube video. 15 June 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MWfJOpgLRzA (accessed on 16 March 2023). |

| 32 | “About Urban Devi,” https://www.urbandevi.com/about-urban-devi/ (accessed on 15 March 2023). |

| 33 | Rukmini goes by her spiritual name paired with her (married) surname in online forums. |

| 34 | See note 32 above. |

| 35 | “Meet Jay and Radhi,” Juni for a Happy Mind website, https://drinkjuni.com/pages/meet-the-founders (accessed on 30 May 2023). |

| 36 | This explanation is spelled out in an article on her website, “Living That Nong (No Onion No Garlic) Life!” https://www.radhidevlukia.co/post/living-that-nong-no-onion-no-garlic-life (accessed on 15 March 2023). |

| 37 | Radhi Devlukia, “5 Books that Changed My Life,” TikTok, https://www.tiktok.com/t/ZTR7AgD8J/ (accessed on 15 March 2023). This was actually posted by Shetty on 13 March 2022 but features Devlukia and remains in her top video feed on TikTok. |

| 38 | Radhi Devlukia, Instagram Post, 13 February 2023. |

| 39 | Radhi Devlukia, “About Me,” Radhi.com, https://www.radhidevlukia.co/about (accessed on 15 March 2023). |

| 40 | Please see note 39. |

| 41 | Radhi Devlukia, “From One Soul to Another,” Radhi.com, https://www.radhidevlukia.co/post/from-one-soul-to-another-we-are-more-alike-than-different (accessed on 15 March 2023). |

| 42 | Radhi Devlukia, “My Spiritual Journey,” Radhi.com, https://www.radhidevlukia.co/post/my-spiritual-journey (accessed on 15 March 2023). |

| 43 | Radhi Devlukia, “FAQ about Meditation,” Radhi.com, https://www.radhidevlukia.co/post/faq-about-meditation (accessed on 15 March 2023). |

| 44 | “Love, actually” Vogue India cover, photographed by Avani Rai, March 2023, https://www.vogue.in/culture-and-living/content/arguments-arent-really-about-the-things-we-think-theyre-about-says-jay-shetty-in-his-new-book-8-rules-of-love (accessed on 1 April 2023). |

| 45 | Akanksha Kamath, 28 March 2023, “‘Arguments aren’t really about the things we think they’re about,’ says Jay Shetty in his new book 8 Rules of Love,” https://www.vogue.in/culture-and-living/content/arguments-arent-really-about-the-things-we-think-theyre-about-says-jay-shetty-in-his-new-book-8-rules-of-love (accessed on 1 April 2023). |

References

- Broo, Mans. 2003. As Good as God: The Guru in Gaudiya Vaisnavism. Turku: Abo Akademi University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brosius, Christiane. 2014. India’s Middle Class: New Forms of Urban Leisure, Consumption and Prosperity. Delhi: Routledge India. [Google Scholar]

- DeNapoli, Antoinette E. 2014. Real Sadhus Sing to God: Gender, Asceticism, and Vernacular Religion in Rajasthan. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flueckiger, Joyce Burkhalter. 2006. In Amma’s Healing Room: Gender and Vernacular Islam in South India. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holdrege, Barbara A. 2015. Bhakti and Embodiment: Fashioning Divine Bodies and Devotional Bodies in Krishna Bhakti. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Karapanagiotis, Nicole. 2021. Branding Bhakti: Krishna Consciousness and the Makeover of a Movement. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lucia, Amanda. 2014. Reflections of Amma: Devotees in a Global Embrace. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, Vasudha. 2003. “Embodied Cosmologies: Sights of Piety, Sites of Power,” 2002 Presidential Address. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 71: 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechilis, Karen, ed. 2004. The Graceful Guru: Hindu Female Gurus in India and the United States. New York and Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rochford, E. Burke. 2007. Hare Krishna Transformed. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, Tanika. 2001. Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press and Permanent Black. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Tony K. 2010. The Final Word: The Caitanya Caritāmṛta and the Grammar of Religious Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]