1. Introduction

Religion plays a significant role in constructing and contesting identities, especially as Indigenous

1 religious traditions are being reimagined and reinvented in an increasingly globalized world. This article examines the revitalization of ancient Greek religion in modern Greece and the ways that it blurs the boundaries between religiosity and non-religiosity. The ethnographic example discussed reveals tensions within modern Greek society related to tensions highlighted by Indigenous movements worldwide. At the same time, the scholarly study of such a movement poses certain challenges as it encourages us to re-evaluate the very limits and boundaries of defining religion through a Christian-centric lens. For this reason, I was thrilled to contribute to this special issue on transreligiosity as this movement defies several boundaries and classifications. While I have outlined several of these tensions here for context, I have focused more on their approach to mythology as an example of defying the boundaries between science and religion.

The group I have discussed here is the Supreme Council of Ethnikoi Hellenes (Ύπατο Συμβούλιο των Ελλήνων Εθνικών (Υ.Σ.Ε.Ε.), hereafter referred to as YSEE). YSEE was founded in 1997 as an umbrella organization and was one of the founders of the World Congress of Ethnic Religions (WCER, later renamed the European Congress of Ethic Religions or ECER). YSEE has been present in the USA (since 2007), founded by the Greek diaspora, and has several locations within Greece, with a total of a few hundred members. The larger Pagan

2 movement in Greece is far from homogeneous as it has multiple and often conflicting approaches to Greek religious tradition, including groups with right-wing ideological leanings or more eclectic ones that incorporate elements from other Paganisms. Having had more success toward legal recognition of the Hellenic Ethnic Religion, YSEE claims to be the only “official” authority on Greek religion. Finally, they maintain transnational relationships with other similar movements through their participation in the biennial congress of the European Congress of Ethnic Religions (ECER), which was hosted in Athens in 2004. Members of YSEE also participated in a joint panel on “Reclaiming the Indigenous Ethnic Religions of Europe” at the 2018 gathering of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Toronto, Canada.

This article is the result of long-term fieldwork with this group. I am a cultural anthropologist who is a native speaker of Greek and have been following YSEE and their publications for over 20 years due to my interest in religious revitalizations and Indigenous religions in general. While studying and working in the United States, I have been in touch with YSEE leaders and members since 2000 during short annual visits to Greece and have developed close friendships with some of them. These relationships have been vital in providing insight into their perspective and struggles. During these short periods of fieldwork, I observed their rituals and attended numerous other events organized by the group that are open to the public. I have also conducted a small number of interviews with long-standing members of the group, mainly priests and priestesses. When not in Greece, I follow their activities on social media and attended several virtual events during the COVID-19 pandemic. For my 2014 publication, primarily on their public discourse, I consulted one of the group’s leaders who offered valuable feedback.

During my visits in 2015 and 2016, I discussed with members of YSEE a recent development that makes this research very timely. The Greek government introduced legislation that allows small religious associations an avenue to gain statutory status and to create their own worship spaces. YSEE had already gathered the supporting evidence and, in 2016, submitted their petition to the government, which was rejected because they identified the religion as “Hellenic Ethnic Religion”. According to the court decision, this would be confusing since the public knows Orthodox Christianity as the “only” Greek religion. YSEE members were not dissuaded and filed a petition to reverse this decision through legal means. This time they solicited the help of scholars of religion, specifically scholars who have researched other Native Faith movements, including myself. I provided an expert statement that provided clarification on the use of the term “ethnic” from a scholarly perspective, which was submitted as supporting evidence. In it, I explained that the use of the term ethnic is encountered in the literature when discussing religions that are associated with a particular ethnic group or culture, as opposed to world religions that spread across multiple ethnic groups. In April of 2017, while waiting for the appeal court decision, the Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Matters gave “Hellenic Ethnic Religion” the status of a “known religion” in Greece and the right to have a worship space and perform legal weddings. Since then, they have increased their educational activities, including mythological workshops for children and ancient Greek language and philosophy classes for adults, some of which I have attended. In recent years, they have also invited me to participate in their rituals as an offering bearer, which has given me a more intimate perspective on the ritual process and preparation.

Ethnikoi Hellenes, by contesting mainstream narratives that tie Greek identity to Orthodox Christianity, are striving for the reconstitution of the religious tradition that they perceive as their authentic, autochthonous tradition, tied to a particular place and ethnic identity. The movement has emerged as part of a global trend since the 1980s, with similar movements classified as “Indigenous” or Native Faith in the scholarly literature to describe religious movements that imagine a future rooted in their ancestral traditions (

Aitamurto and Simpson 2013;

Lesiv 2013;

Rountree 2015;

Stasulane 2019). European Pagans themselves prefer the term “Indigenous” or “ethnic” religions. This is an argument that has been articulated by European Pagans themselves (

ECER 2018), while it was implicitly acknowledged at the 2009 Parliament of the World’s Religions meeting in Melbourne, when European ethnic traditions were included in the same category as other Indigenous religions (

Corban Arthen 2010;

Rassias n.d.).

As I have argued elsewhere (

Fotiou 2014), I consider this movement to be a religious revitalization movement, according to Anthony Wallace’s definition, as a “deliberate, organized, conscious effort by members of a group to create a new and more satisfying culture” (

Wallace 1956, p. 279). Revitalization movements

3 occur during times of stress for individual members of the culture and when there is widespread disillusionment or disappointment with existing cultural beliefs. They are common in areas that have been colonized, although recent work (

Harkin 2004) has proposed a reassessment of the colonialism hypothesis to include potential oppression by internal forces or potential unresolved internal conflicts. Ethnikoi Hellenes argue that Greeks still suffer from the disorientation that resulted from Christianization and the loss of the Indigenous identity and worldview. Thus, this revitalization might also point to long-standing internal conflicts in the Greek culture that have never been adequately addressed or resolved (such as the relationship between Christianity and the pre-Christian religion or the relationship of the Orthodox Church to the Greek state that is receiving increasing criticism). Such movements have been called “nativistic” in earlier scholarly literature and have been described as selectively reviving cultural elements, particularly ones that distinguish a society from others (

Linton 1943). The Greek movement emphasizes not only the differences between the Hellenic Ethnic Religion and Orthodox Christianity but also between Indigenous religions and monotheistic religions in general.

One of the tensions that blur boundaries in this ethnographic example is that between the Indigenous and the global or cosmopolitan. Native Faith movements have a fundamental difference from Neo-Pagan movements in North America as they claim roots in local history and landscape, and are concerned with a distinct ethnic identity. However, not all espouse nationalist discourse. Unlike other Indigenous movements that might make claims for sovereignty, YSEE, despite its fierce critique of hegemonic religious discourse in Greece, does not make such claims. In fact, with their willingness to utilize the tools that being a member of the European Union puts at their disposal (such as the European courts) they embrace a more cosmopolitan view, while being rooted in a specific ancestral tradition. One of its leaders has published books on the French revolution and they embrace its liberal ideals such as liberty, equality and fraternity.

Several case studies of European Native Faith movements (

Asprem 2008;

Blain and Wallis 2004;

Butler 2005;

Fonneland 2017;

Harvey 2020;

Howell 2008;

Ivakhiv 2005;

Lesiv 2013;

McKay 2009;

Rountree 2014;

Szilárdi 2009;

Strmiska 2012;

Simpson 2000;

Shnirelman 2007) have shown the ubiquity and diversity of these movements.

Strmiska’s (

2012) typology of eclectic versus reconstructionist movements is often employed in the study of Pagan movements and, though the typology can be useful, its usefulness is limited by the fact that existing ethnographic examples often defy these categorizations by combining elements from both. Reconstructionist movements seek to revive pre-Christian religious traditions tied to a specific region and have often been associated with ethnic nationalism and even racial supremacy, although several ethnographic examples—including the Greek one—defy this association. Ethnikoi Hellenes reject the Orthodox Church’s intolerance, while the rise of the extreme right, impelled by the financial crisis (

Dalakoglou 2013), propels the group to distinguish themselves from right-wing discourse. This “dissonance” has been discussed in the literature for other movements (

Charbonneau 2007), and the ethnographic evidence reveals tensions between nationalism and multiculturalism within the Greek movement.

The relationship between religion and ethnic identity is often taken for granted, as the concept of ethnodoxy

4 illustrates (

Karpov et al. 2012). Anthony Giddens has warned of the fact that social identities are different in different historical projects and thinks that one may speak of identity as “a symbolic construction”, which helps people find their own place in time and preserve continuity (

Giddens 1991). Ethnikoi Hellenes challenge the affiliation to the prevailing religion in Greece and propose an alternative way of constructing Greek identity and of relating to the divine. The discussion in this article is part of my larger project of researching how Ethnikoi Hellenes seek meaning and achieve belonging in a “world that is constantly calling into question canonized myths of origin” (

El-Ghadban 2009). Their engagement with geomythology, as discussed here, is part of establishing the indigeneity of Hellenic Ethnic Religion.

Indigeneity as a concept has generated much debate in anthropology (

Kuper 2003;

Asch et al. 2004), especially regarding its ambiguous character (

Friedman 2008). It is used primarily in discussion concerning settler societies (

Salmond 2012) with some references to Europe (

Kvaale 2011), and its use vs. that of the term autochthony has been discussed (

Gausset et al. 2011). The transnational and political dimensions of the concept have also been addressed in the literature (

Gomes 2013). Indigeneity is often associated with blood or ethnic purity (

Snook 2013), while some scholars have noted a shift to a more “cultural” discourse (

Singh 2011) and others point out that dichotomized discourse (Indigenous/non-Indigenous) is limiting in terms of revealing the complicated configurations of identity that play out in ethnography (

Norget 2010). This article contributes to this latter conversation and explores how the concept of indigeneity is strategically utilized beyond what would fit the traditional definition of “Indigenous” as well as on a relational understanding of indigeneity (

Rose 2009). As others have pointed out, indigeneity can be more about a way of being in the world as well as ways of relating to nature (

Glauser 2011). Indeed, Ethnikoi Hellenes utilize the concept in this manner to emphasize an identity vis a vis the hegemonic religious culture in Greece and to protest the marginalization of certain ways of being in the world.

Another identifiable tension is that between the old and new. New religions are those religions that are found, from the perspective of the dominant religion, to be “unacceptably different” (

Melton 2004). The Greek revitalization movement exists at this contradicting space, labeled as “new” by Orthodox Christianity, and mainstream society, at the same time, claiming a longer history in the region, blurring the distinction between old and new. While the movement is not syncretic and is based on written scholarly and primary sources, at the same time, it is adapted to contemporary life, emphasizing philosophical virtues that can inform everyday life. Similar movements are often discussed in the literature as being simultaneously old and new, pre-modern and postmodern, and influenced by the multiple uncertainties wrought by globalization and the continuous circulation of religious ideas and practices from afar. Three edited volumes that span the last couple of decades have attempted to address this paradox and the multiple layers of complexity of these movements (

Strmiska 2005;

Aitamurto and Simpson 2013;

Rountree 2015). Rountree rightly pointed to the extreme diversity of such phenomena, many of which claim to respond to a global ecological crisis. However, my research indicates that the Greek case is much more complex, and the crisis in question is perceived to be

cultural and is attributed to Greece’s particular historical and cultural circumstances. For example, while some Pagans in other European countries might be more inclined toward syncretism due to a less conflicted recent history with Christianity (

Butler 2005), so far, most Ethnikoi Hellenes see their worldview as incompatible with that of monotheistic religions.

Based on the ethnographic evidence, part of which I have presented later in this article, this movement does not fit in the scholarly frameworks of new religious movements such as Neo-Paganism or the New Age movement. For example Brian Morris outlined the basic principles of Neo-Paganism as a worldview as follows: “radical polytheism, an ecological and feminist emphasis, decentralized politics, the celebration of ritual, a stress on personal experience, and the embrace of esotericism—the notion that divinity is within the human personality” (

Morris 2006, p. 272). Besides polytheism and the celebration of ritual, which are central in most Indigenous religions, the remainder are not present in the Greek movement. In addition, this movement challenges scholarly models of new religious movements since, although it espouses cosmopolitan ideals at the same time, it is not syncretic and does not approach religion as a path to self-transformation (

Lewis and Melton 1992, p. 19;

Morris 2006)—as many New Age exponents do—but as a way to societal transformation. In addition, they have only revived aspects of the religion and worldview for which there is clear scholarly evidence, and they refuse to revive practices such as the oracles or mysteries that some New Age or more syncretic religions were quick to revive, of which YSEE members are quite critical. Their rationale is that society needs to be transformed first and populated by virtuous individuals before these rituals can be revived.

Ethnikoi Hellenes simultaneously root themselves in a deep “traditional” past while looking to the European Union, that they perceive to be inspired by enlightenment and liberal ideals, to defend their claims. Their discourse reveals that they feel that Europe is closer to ancient Greek ideals than Orthodox Christianity, which they claim is a religion that came from the “desert”. Moreover, they challenge the sovereignty of the Greek state, which they argue is under the thumb of the Greek Orthodox Church as well as bound by imposed austerity measures. Similar arguments regarding weakened states have been made in the scholarly literature (

Brown 2010;

Sassen 2008). As a solution to this perceived cultural crisis—which, in their view, has preceded and contributed to the current financial crisis—Ethnikoi Hellenes envision a new form of citizenship inspired by ancient Greek ideals and their worldview. In their discourse they often argue that, unlike Orthodox Christianity, Hellenic Ethnic Religion’s ontology and theology were more relevant and closer to modern life and modern science. In fact, their discourse echoes recent calls within scholarly discourse to “decolonize the mind” (

Clammer 2008), “unsettling colonial logics and institutions” (

Bonilla 2015).

What ethnic religious movements are trying to achieve is important on multiple fronts. First, they are reimagining citizenship and they envision citizens of their respective nations that are politically, philosophically and spiritually engaged with the society at large. In this case, ethnic religions provide a framework that challenges state-sponsored monotheistic narratives. I would argue that what Ethnikoi Hellenes are attempting to do is akin to what Indigenous activist communities have carried out in former colonies—they forge visions for the future by reconfiguring dominant narratives of the past (

Bonilla 2015). While Indigenous activists in Latin American have reconfigured histories of colonialism and slavery, Ethnikoi Hellenes do the same with the official state narrative that wants Orthodox Christianity seamlessly blending with and organically continuing ancient Greek tradition. By focusing on the violent predominance of Christianity in Greece, a legacy that still pervades modern Greek society, they attempt to do what Yarimar Bonilla calls “unsettling colonial logics and institutions” (

Bonilla 2015). Secondly, they are redefining religion itself, challenging boundaries between religion and science and the association of Indigenous religions with “irrationality”. They approach Greek tradition holistically—as a worldview according to their discourse—encompassing not only religion, but philosophy and science. More importantly, they find this worldview to be more compatible with contemporary reality. They do this by pointing out the inconsistencies and irrationalities of monotheistic religions, which they consider responsible for the widespread “cultural” crisis facing humanity.

This latter point will be the focus of this article. After establishing the ethnographic context, I will discuss the ways that the Greek revitalization movement blurs boundaries between science and religion, thus exhibiting transreligiosity, as was introduced and discussed by

Panagiotopoulos and Roussou (

2022). I will demonstrate that this is an “engaged religion” not only meant to transform society but to approach the divine through philosophy and science.

2. Ethnographic Context

Governments and mainstream religions are often hostile towards new religious movements (

Clarke 2006) and Greece is no exception. The Orthodox Church has been, and continues to be, a conservative force in Greek society, often exhibiting fundamentalist characteristics in order to maintain its position in a society that is becoming increasingly more secular and modernized (

Sakellariou 2022). As a result, they promote a narrative of organic continuity between ancient Greece and Orthodox Christianity, while treating most other religions as threats to the national identity (

Fotiou 2014). While the freedom of religion in Greece is guaranteed by law, the constitution also recognizes Orthodox Christianity as the prevailing religion of Greece, a fact that creates an apparent legal conflict (

Kyriazopoulos 2001). The only other officially recognized religions are Islam and Judaism, although there is still prejudice among the public against these religions (

U.S. Department of State 2022). The recent so-called refugee crisis has exacerbated this (

Sakellariou 2019). While the Greek Constitution prohibits proselytizing by other religions, no such restrictions are imposed on the Orthodox Church. The church also enjoys certain privileges not available to other religious organizations such as being largely exempt from paying taxes. In addition, the Orthodox clergy’s salaries and pensions have been paid by the Greek state since the 1980s. The Orthodox Church is the only authority that can advise the state on decisions regarding which religions are legitimate and which are merely “cults” or “heresies”, in other words, which religions deserve to have rights, which may create a conflict of interest. Christian Orthodox instruction is part of the curriculum in primary and secondary education, whose mandatory nature for Orthodox students and the cumbersome process for parents who want their children to be relieved from it, has been challenged in European courts (

Fokas 2019).

While some European countries are moving towards official recognition of their respective pre-Christian religious traditions (

Beckford 2010;

Fonneland 2017), this is not the case in Greece. Until recently, religions without official recognition were forced to register as non-profit organizations and were obliged to pay a “business tax”, which several Pagan groups protested (

YSEE 2012). However, in 2014, a new law, 4301/2014, provided an avenue for the establishment of “religious legal persons” in Greece. Following the now clearly outlined legal process, YSEE obtained the license to establish an official place of worship in 2017 (

U.S. Department of State 2018), which means that they are recognized as a “known religion” by the state. This gives them the authority to perform religious weddings and naming rituals, which are recognized by the state. The first such wedding was performed in their temple in downtown Athens in January of 2022. The religion is still not among the officially recognized religions, despite the fact that the legal case reached the Supreme Court of Greece. They have been unsuccessful in obtaining this designation, due to a disagreement about their chosen name for the religion—Hellenic Ethnic Religion—which the court deemed would “confuse” Greek citizens (due to the fact that the word

εθνικός in modern Greek is also used to mean “national”. Within this context, Ethnikoi Hellenes, although predominantly from the middle class, face marginalization and ridicule to the point that they often conceal their religious affiliations from their coworkers and sometimes family and friends. Added to this are misconceptions (an example being an older rumor of Pagans engaging in orgies), which further increase the chances of ridicule. For a long time, contemporary Ethnikoi Hellenes’ status was one of invisibility, whether imposed or voluntary; although, more recently, they have utilized several media outlets to promote visibility, and ultimately, acceptance (i.e.,

Zacharis 2019).

YSEE rents a space called Ekatevolos (Εκατηβόλος) in downtown Athens where they hold weekly lectures, philosophy seminars, ancient Greek language classes and monthly rituals based on the ancient Attic calendar. The space acquired the status of official temple of the Hellenic Ethnic Religion in 2017. Events promote an inquisitive approach, which privileges dialogue, diversity and self-study. They view this is a process of recovering their original tradition, a familiar argument of some Indigenous movements in parts of the “Global South” (

Pantoja 2014). The Greek case is unique compared to other revitalization movements that might have emerged out of oral traditions, in that there are numerous surviving ancient texts that they can refer to, and many members can read the original ancient Greek. However, they do not aim for an uncritical regurgitation of tradition and are critical of academic sources that they perceive as not understanding the emic perspective of worshipers. They have adapted rituals to modern circumstances for practical reasons, and they recognize that culture is dynamic and ever changing—anything different would be a sterile reproduction and not worthy of a “living” religion. What they protest, however, is the violence through which cultural change happened and the erasure of that violence from formal education today. Members of YSEE have mentioned to me in conversations that an official apology for those crimes from the church would be very welcome.

The aforementioned concept of “ethnic religion” is at the center of YSEE’s long legal battle, on which they are not willing to compromise. According to the scholarly literature, “ethnic religion” establishes the link between religion, language and ethnic identity (

Hammond and Warner 1993;

Aitamurto and Simpson 2013). In the modern Greek language, εθνικός means both “ethnic” and “national”, which prompted the court to reject the group’s petition as it was argued that the national religion of Greece was Orthodox Christianity and the recognition of the group under this name would confuse Greek citizens. For their appeal to the Supreme Court the group solicited the assistance of scholars of religion to testify on the appropriateness of the term “ethnic”. In the meantime, the Greek Ministry of Education and Religious Matters gave the “Hellenic Ethnic Religion” the status of a “known religion” in Greece. This is significant because it is reshaping the religious discourse and landscape in Greece. It also challenges some of the scholarly literature that considers Greek Orthodoxy as an “ethnic religion” (

Kivisto and Croll 2012). Importantly, it brings to the fore the key areas of contention in contemporary Greece around conceptions of identity and “tradition”.

This ethnographic example shows that the processes of religious revitalization and the construction of identity and “tradition” are ambiguous and have multiple tensions. I propose that, through this process of revitalization, “tradition”, “culture” and “religion” are reconstituted neither as something wholly ancient nor wholly new, but as something more representative of the numerous manifestations of Greek identity in existence today. One of these manifestations is the contemporary view of Greek identity through the mirror of European enlightenment, during which, Greek culture was rediscovered and reinvented, only to be reintroduced to modern Greece. In fact, some Ethnikoi Hellenes have recently argued that what is needed today is a “new enlightenment”. Their events and educational activities described in the next section aim to facilitate this proposed enlightenment.

3. Bridging Science and Religion through Geomythology

In this section, I will discuss the transreligious elements in this group. What makes this movement unique among other Native Faith movements is the centrality of “logos” to their theology. They refer to Hellenic religion as “natural” and therefore “impossible to destroy”. In their website’s section on worldview (Κοσμοθέαση), they state that “Our ‘dogma’ includes: the obligation we all have to speak and act

logically as a mark of respect for

Universal Reason, our honest relationship with all living beings, tolerance towards all views that are expressed

logically, education through life experience, respect for measure, and the continuous study of the Cosmos and Humanity” (

YSEE n.d.a, my emphasis). In recent years, they have begun to hold theological seminars in their space (as well as online during the COVID-19 pandemic) and discussion often revolves around worldview: the particular way ancient Greeks saw and interpreted the world. This worldview emphasizes reason and this conclusion results from close study of ancient texts that are discussed in these seminars. They argue that “logos” was given to humans from the gods in order for them to make sense of the world. Importantly, gods are not conceived as supernatural beings outside of the world, but as integral parts of the world, and are therefore “natural”.

This emphasis on reason not only differentiates the Hellenic Ethnic Religion from Christianity but also allows them to approach ancient sources in a particular way. This has been exemplified by their engagement with geomythology in recent years. Geomythology is a field of study that concerns myths and legends from different cultures, focusing particularly on those myths that record significant geological events such as volcanic eruptions, tsunamis and earthquakes. The term was coined by Dorothy Vitaliano in 1968 (

Vitaliano 1968) who argued that some of these events must have been so traumatic or significant that they inspired people to explain them through myths. Geomythology, according to Vitaliano, attempts “to explain certain specific myths and legends in terms of actual geologic events that may have been witnessed by various groups of people” (

Vitaliano 1973, p. 1). She differentiated between two types of geomyths, the first being etiological, which were invented after a geological event to explain its aftereffects without having witnessed the geological event that caused them. The second type of geomyth includes euhemeristic fables (the word comes from Euhemerus, the ancient Greek mythographer who was the first to have used a rationalistic approach to myth). These latter legends embody “the more or less distorted memory of real occurrences, usually catastrophic” (

Vitaliano 1973, p. 272). Several scholars, including some Indigenous scholars, have argued for a closer study of myths with the goal of identifying references to actual geological or historical events that can help correct scientific results or provide alternative hypotheses to be tested (

Deloria 1997;

Swanson 2008). Some have even argued that geomythology, despite being oriented toward the past, might be able to supply resources for solutions to current environmental challenges (

Burbery 2021).

While some have argued that studying myths could help set future scientific agendas to produce new and plural knowledges (

King et al. 2018), Ethnikoi Hellenes have engaged with the scholarly literature on geomythology to connect religion to the landscape and to bridge religion and science. Geomythology connects people to the land, highlighting “sacred sites” that they have a special relationship to. For modern Ethnikoi Hellenes, it additionally highlights the fact that myths can contain knowledge that is rational and not in conflict with science. The way that YSEE challenges several boundaries is evident in their engagement with geomythology which forms part of their myth workshops for children; these were held once a month before the COVID-19 pandemic. They argue that myth is “tradition” handed down from generation to generation and that tradition is therefore “sacred logos”. Myth also reflects a people’s way of life and values. Geomythology combines geology with mythology and attempts to interpret myths through a geological lens, thus transgressing boundaries between science and religion and exhibiting transreligiosity.

They argue that much of Greek mythology relates to geological events in the Aegean Sea; therefore, it contains important geological information that ties the religion to the landscape. Significant changes in the landscape from era to era were preserved in the narratives of myths that Ethnikoi Hellenes consider as “natural”, that is, they are the narrated actions of the “Gods in the World”. Through geomythology, one can learn about floods, volcanoes and even human intervention on the environment. They have used the examples of the myths regarding the labors of Heracles to teach children about geomythology. The geomythological interpretation is based on published academic works by geologists, that several group members engage with in order to gain a better understanding of Greek mythology.

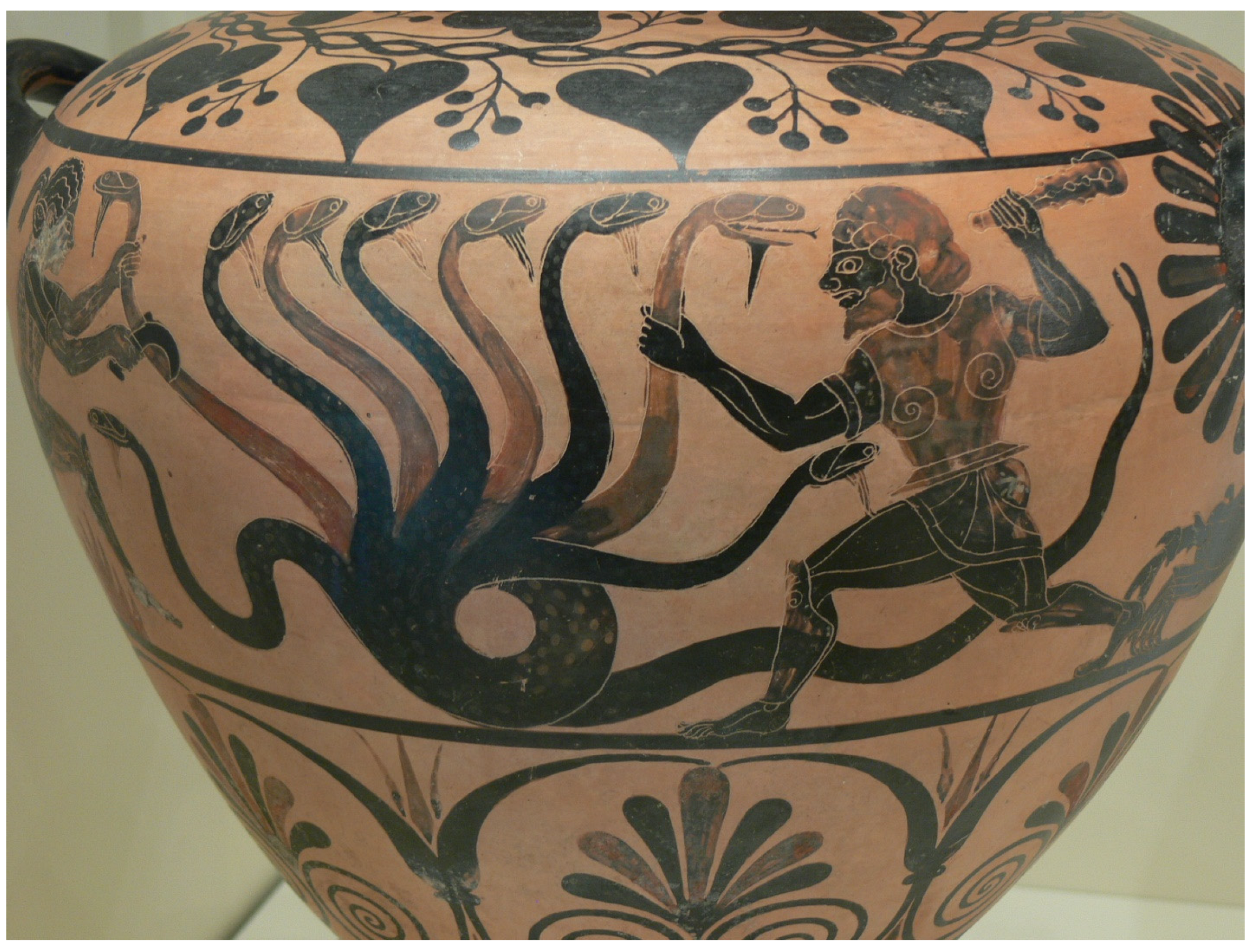

I will discuss one example of such a myth from the scholarly literature here. The Lernean Hydra was a fearsome monster who lived in the swamp of lake Lerna, near the east coast of Peloponnesus. It had a gigantic serpentine body, with several appendages, with a head at each end (

Figure 1). While the number of the heads of the Lernean Hydra varies in different accounts, all of them agree that the Hydra had one central head that was immortal. The monster’s breath was poisonous and it would often spit out fire, which destroyed everything in the Argolic plain, including crops, trees, animals and people. The surrounding swamp was covered in a poisonous mist. When one chopped off one of Hydra’s heads, two new heads would spring back. The Greek hero Heracles, who is associated with the sun in Greek mythology, was tasked with killing the monster. Assisted by the Goddess Athena and his nephew, Iolaus, he used fire to cauterize the stump of each chopped head with a firebrand, which prevented more heads from appearing. When it was time for the immortal head to be cut off, Heracles took a golden sword that Athena gave him, and using the same technique, the two heroes managed to kill the monster.

Through the lens of geomythology, the myth coincides with the hydrogeological conditions of the area. Specifically, it has been argued that it relates to the conditions of the karstic springs of lake Lerna, which was located south of Argos. A karstic spring is a spring (outflow of groundwater) that is part of a karst hydrological system (karst is a topography formed from the dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite and gypsum). It is characterized by underground drainage systems with sinkholes and caves. The myth reflects the annual as well as the long-term changes in the springs’ discharge. The heads of the monster could be the springs, some of which discharged water seasonally, while the immortal head could be the central spring which discharged water all year round. According to a Greek geologist:

“Hercules trying to exterminate Lernean Hydra started by decapitating, one by one, the beast’s heads. The decapitation of each head, which represents a spring’s discharge at a karstic point, may become possible by the placement of a rock at the point where the water discharges in order to prevent its exit or to force it to follow another route. It is known, among geologists, that the karstified rock body, through which the underground water circulates on its way to the spring, represents a complex system of underground, intercommunicating ducts. In addition, the tectonic discontinuities, even if the karstification is not very intense, are also permeable. Therefore, if someone places a rock in front of the mouth of a karstic spring, the water will come out from two other or more points. That is the reason why in the place of a Hydra’s head that Hercules cut, two others would sprout”.

The central spring never stopped discharging water, which created bogs in the area, and as a result, infectious disease was spread. Humans managed to rid themselves of the harmful consequences of the bog by using fire, burning the plant life in the area and drying the swamp out. According to Mariolakos, after the climatic stabilization (6000 BP) and the cultural development of Greek society, the main issue, besides water supply, was the protection against droughts and floods. This issue was addressed by the use of advanced geotechnical methods and hydraulic works (

Mariolakos 2018). This is one example of a myth that might contain information about actual geological events.

This approach to myth, far from being reductionistic, attempts to bridge science and religion by adding another layer of meaning to myths that are important to an ethnic group. In a sense, it sacralizes science while finding rationality behind mythical narratives. From the perspective of the worshipers, finding scientific meaning in myth demonstrates the fact that ethnic religion is “natural” as well as “rational” and therefore not in conflict with science. Admittedly, this is a qualitatively different conceptualization of rationality, and one that does not perceive religion and science as incompatible, but as different ways of approaching the same subject. Although Western scholarship seems to trace rationality to ancient Greece, at the same time potentially fetishizing it, the Ethnikoi Hellenes’ approach seems to be closer to Indigenous conceptualizations that are open to alternative ways of being in the world that can coexist and potentially inform each other.

Heracles features predominantly in the activities designed by YSEE for children. Since 2017, YSEE has participated in the Athens Science Festival with mythology workshops designed specifically for children (

Figure 2). The festival is an annual event geared toward engaging the public with scientific knowledge and has proven very successful. These workshops follow the format that was previously used successfully in similar workshops that were held on a monthly basis before the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, the workshop focused on the Heraclean myths and they used this text for the promotion of the event: “With Heracles as our fellow traveler and the science of geomythology as our guide, we travel to the places of the myth and learn about the environmental changes associated with his labors. Geomythology is the academic discipline that emerged from the intersection of geology and mythology. It deals with the interpretation of natural myths in relation to the natural environment and the climatic conditions of prehistoric times. Our aim is to bring children in contact with the natural environment and its changes in prehistory through the science of geomythology”. Such activities have also used mythology to discuss natural features such as celestial bodies, the solar system and constellations through the myths that gave these bodies their names. In the 2022 festival, they also included a hands-on activity entitled “Deciphering Mycenaean Scripture” in which children learned to write their name according to the Linear B syllabary and carved it in clay.

Based on the ethnographic evidence, the Hellenic Ethnic Religion movement emphasizes resonance to ancestral traditions and a connection to the land, thus exhibiting “indigenizing” tendencies, as discussed by

Johnson (

2002). Johnson added that the term Indigenous religion “connotes the religion of peoples that is the natural growth of a particular land, an organic, biological relation between a group and a place” (

Johnson 2002, p. 309). When asked what a geomythological approach offers to Ethnikoi Hellenes today, one of the members of YSEE, a geologist, said: “Geomythology initially connects certain myths to the natural environment and its alterations”. This reveals the “natural” background of these myths. In addition, many myths bear the particular characteristics of a place, proving their autochthony. When the wider mythological environment can be dated, their age can be proven. This timeless consistency shows the absence of introduced foreign elements in this older tradition of the Indigenous populations of the wider Aegean space. This can also extend to religion on many levels”. In sum, these geomyths prove the autochthony of the religion, since its mythology is intimately connected to the landscape. These indigenizing tendencies, as demonstrated earlier, coexist organically with more universalizing tendencies and find common ground with other Indigenous movements that share similar worldviews.

In addition, and more importantly for the argument in this article, the fact that the stories in these myths have a “natural” vs. a supernatural basis means that they can provide information that can be useful to scientific inquiry and interpretation. This way, the boundaries between religion and science are blurred, revealing the transreligious nature of this movement. Indigenous lifeways or worldviews share a vision that honors relationships between human and non-human persons, but also important sacred sites in a group’s geomythology. By focusing on worldview and by proposing a different ecological and environmental ethic, these lifeways can potentially help avert the global environmental crisis.

4. Conclusions

I have presented several tensions within the Hellenic Ethnic Religion movement that transgress boundaries and exhibit transreligiosity. First, it blurs the distinction between old and new by highlighting perceptions of tradition as being simultaneously old and new. As discussed, Ethnikoi Hellenes challenge official religious discourse by utilizing a discourse of indigeneity to claim legitimacy by connecting to an ancestral past. They practice Hellenic Religion as a living religion and are critical of scholarly discourse that treats it as a dead tradition. They argue that the religion is not revitalized but has rather “resurfaced” in recent years because of increased freedom and democratic ideals since the fall of the last dictatorship in Greece. They claim that the religion was kept alive underground by certain families who still practiced it, mainly in Italy, during the Ottoman occupation. Importantly, at this historical time, ancient concepts and ideas are deemed more relevant to contemporary life and challenges.

Secondly, the revitalization of ancient Greek religion also embodies transreligiosity by combining openness to universal ideals with the fundamental connection to one’s cultural roots. While it is not syncretic, at the same time, it celebrates the diversity of Indigenous traditions and their right to exist. The history of the group indicates this very clearly. One of its founders was researching and engaging with global social movements before he was directed to looking at his own tradition by Native Americans. This shows a trend towards looking outward, while having a strong foundation in one’s own tradition. Their discourse often discusses the cultural diversity that was threatened by the spread of world religions—referring mostly to monotheistic religions with universal appeal that are not associated with a particular ethnic group. They argue that cultural diversity, where ethnic religions exist without attempting to impose their worldview on others, is more natural and therefore desirable. At the same time, they do not approach tradition as being bounded or contained, but are open to new elements as long as they are not forced upon people. By emphasizing indigeneity, and in solidarity with Indigenous movements across the globe, they unite in a common struggle against what they perceive as the relentless expansion of monotheism threatening religious and cultural diversity. The sense of solidarity expressed among these religious movements could be interpreted as a response to rapid globalization, but a closer look reveals that it is the expression of long-term historical tensions that are finally taking organized form. These tensions between dominant cultures and Indigenous cultures seek to be relieved through the recognition or “dignified reconstitution” of Indigenous religious traditions in their respective countries. As these religious movements claim their place in the religious landscape, transreligiosity will become the norm rather than a marginal phenomenon.

Finally, by making “logos” or reason central to their theology, they are “flipping the discourse” on religion: they challenge the association of Indigenous religions with irrationality, while pointing out the inconsistencies and irrationalities of monotheistic religions, which they consider responsible for the widespread “cultural” crisis facing humanity. This discourse, by blurring the boundaries between religion, science and philosophy, challenges the compartmentalization of these spheres and reframes their relevance for modern Greek citizens. In fact, they often support their argument for cultural diversity by comparing it to biological diversity. Additionally, through the lens of geomythology, they interpret important geological events without encountering a conflict between myth and scientific discoveries. Thus, they deem Indigenous religions—which, in their view, are “natural religions”—as more adept at assisting humans in solving current crises.

It is often argued that the engagement of the West with the “other” is on the basis that the other is exotic, mysterious and irrational. Several current religious trends (including my previous research on shamanic tourism) indeed reveal a yearning for finding solutions in the “other”, whether that be the exotic Amazonian “other” or the “other” located in the past of one’s own culture. What the ethnographic example presented here shows is that assuming the irrationality of the “other” is no longer valid. The ways that geomythology has been approached by Indigenous scholars encourages us to examine knowledge such as that provided in myth not merely as symbolic and irrational, but as a legitimate source of knowledge that could be useful today (

Deloria 1997). For Ethnikoi Hellenes, a geomythological approach provides vindication for the rationality inherent in myth, as well as a direct link to their past and a meaningful connection to the landscape.