Abstract

There are many studies that deal with the role of media and the motives for their creation. The present article explores the background behind the development of Ultra-Orthodox journalism. It examines the establishment of Ultra-Orthodox daily newspapers in Israel at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first by analyzing semistructured texts and ideas. The historical background and the way this journalism developed in general and specifically during those years reflect a strong social and censorial orientation. This study concludes that these newspapers can be seen as social definers that help preserve a community through censorship aimed at the general and other Ultra-Orthodox media. It helps communities and individuals self-define and can delineate an additional role for mass media as a social definer. The contention herein is that the establishment of Ultra-Orthodox newspapers in Israel serves as a mode for social definition; a definition that is arrived at by being part of the circle of the newspaper’s readers, and the newspaper, in turn, defines itself by its censor board.

1. Introduction

“Tell me what you read andI’ll tell you who you are”(Oscar Wilde)“That is true enough, but I’d knowyou better if you told me what you reread.”(François Mauriac)

Many actions are motivated by a need for self-definition (Ryan and Deci 2017). Different studies have pointed to the various ways that individuals define themselves. Religion and religiousness, for instance, can serve as a means of self-definition (Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005; Ysseldyk et al. 2010; Hogg et al. 2010). Other studies have examined selective exposure to media as a possible expression of self-definition (Hart et al. 2009; Velasquez et al. 2019). Later studies have contended that it is rather difficult to prove that selective exposure is a result of self-definition as it is possible that people tend to claim that they consume media selectively based on how they wish to be externally defined. Yet, the exposure may be less selective than claimed (Hart et al. 2020). One way or another, it would appear that people choose to present their media consumption as choices that openly define them.

In this study, we combine the earlier conclusions regarding the tight connections among self-determination and selective exposure to media, the selective publication of media consumption, and religion. We contend, for the first time, that in some cases entire media outlets were established and still exist because of human and societal needs for self-determination, both as an individual and as part of a community.

By its very definition, communication conveys messages from an addresser to an addressee (Nöth 2013). In practice, in our present world, communication has other roles apart from the classical ones: preserving communities, defining communities, defining the members of communities, and writing rules of belonging to and identification with the community. The consumers of those means of communication, in turn, use them more as tools for social and intracommunal self-definition than as ways to report the events in the outside world.

A central part of this study relies on the connection between the media and censorship and its implication in the context of social-communal statements. Censorship is mainly described as a means of avoiding content that is uncomfortable or harmful to the establishment (Antasapalio 2020) and a social tool that could be used by a community to shield itself by building defensive walls (Friedman 2019) and—as it would be proven further on—to define itself. It is utilized by different communities to sustain their existence and to protect them from the dangers that lie in wait in the outside world, including those that come from other communities that may blur its definition as a unique entity.

We focused on Ultra-Orthodox daily newspapers in Israel from the last two decades of the twentieth century and the first two of the twenty-first century analyzing the circumstances that led to their establishment and their connection to self and community definition. We draw a historical-developmental model of the printed Ultra-Orthodox daily press against the backdrop of the community’s development and censorial evolution. We chose to explore this subject because of the heightened communalism that has been noted within the Ultra-Orthodox sector (Brown 2017) and the Ultra-Orthodox media’s extensive use of internal censorship (Neriya-Ben Shahar 2008, 2014).

2. The Roles of Communication

The structural-functional theory is a widely accepted sociological approach that describes the structure of a society and its systems, including its mass communication. According to this theory, every system that operates in a society has a functional role in preserving the social structure and that is the reason for its existence. Mass media are needed and have their functional roles (McQuail and Deuze 2020). Some arbitrary typologies examples from a variety of media roles suggested by scholars throughout the years: Lasswell defined the roles of mass media and specified three such roles: surveillance of the environment; correlation of parts of the society; and cultural transmission and socialization (Lasswell 1948). That is to say, the various media are not just tools to inform but also serve as socializing agents, which teach and prepare the individual to be part of a community. Wright and Page (1959) added a fourth role: entertainment—when communication is used for entertainment to help relieve stress and allow one to escape from the daily grind. McQuail added a fifth role: persuasion—rallying the masses around in connection with particular agendas: idealistic enlistment, soliciting donations, and/or enlistment for national interests. This role is especially prominent in times of security concerns (McQuail 1984, 2010; McQuail and Deuze 2020). We contend that communication has an additional social function and that there is yet another motive for the establishment and preservation of media.

3. The Ultra-Orthodox Community: Definition and Central Characteristics

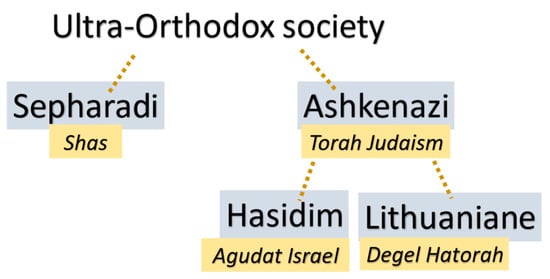

Ultra-Orthodox society is divided into many subgroups representing different social and ideological shades. The primary divisions are Hasidim, Lithuanians (non-Hasidic Ashkenazim), and Sephardim (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ultra-Orthodox groups and their political parties in Israel in 2020.

The split between the Lithuanians and the Hasidim began to develop in Eastern Europe in the eighteenth century and that between Ashkenazim and the Sephardim came about as the result of the various countries of origin in the Diaspora (Zicherman 2014). The Lithuanian ideal is primarily Torah study, whereas the Hasidic ideals are strict conservatism regarding issues of gender segregation, sexuality, and traditional attire. The Lithuanians are characterized by a relative openness to modernity, which is evident in their modern dress. (Gottlieb 2007; Gal 2015; Leshem 2011; Sivan and Kaplan 2003; Kaplan and Stadler 2012; Brown 2017). The Hasidim are affiliated with the political party of Agudat Israel whereas the Lithuanians are represented by Degel Hatora. The Sephardim are characterized by a “soft Ultra-Orthodoxy,” which means a relative closeness to the general conservative population in Israel and less of a tendency to cling to the radical Ultra-Orthodox point of view (Leon 2009, 2016). The Sephardim are represented by Shas.

The significant differences in lifestyles among the three groups are expressed primarily in five ways:

- Areas of residence: Hasidim often live in a community made up exclusively of members of their own group, and their involvement in the community is intense. The community has an array of educational institutions, committees for visiting the sick, local medical help for the sick, arrangements for mutual aid, and more. Lithuanian and Sephardim tend to live in mixed cities with other groups and among the secular population (Gal 2015);

- The spiritual emphasis: Hasidim emphasize prayer, rituals, and the use of the mikvah, whereas Lithuanians and Sephardim emphasize Torah learning (Leshem 2011);

- The perception of the leader: The Hasidim call the head of the community Rebbe (our lord, our teacher, and our rabbi), and his role is to mediate among the Hasidim themselves and between each individual and God. The Lithuanian and Sephardi leaders are called ‘Rabbi’ and are spiritual leaders and religious arbiters (Brown 2017);

- Clothing: Hasidic men wear similar to what they wore in Eastern Europe: a long black coat and a special hat (which varies from group to group), and they grow long peot (curls on the sides of their faces) and beards. In contrast, the Lithuanians and Sephardim dress in Western-style attire. Until their wedding, most Lithuanians and Sephardim shave their beards; after the wedding, many of them grow a well-kept beard (Deutsch and Casper 2021);

- Language: the Lithuanians and Sephardim speak Hebrew among themselves whereas Hasidim speak Yiddish among themselves and use Hebrew primarily for conversation with the outside world (Zicherman 2014). Ultra-Orthodox Jewish society is defined as being committed to abiding by Jewish law as it was developed and informed by authorities ordained in Jewish tradition according to the Ultra-Orthodox interpretation (Friedman 1991). Although it is often described as a diverse, dynamic, and changing community comprising several distinct groups (Shomron 2022), certain beliefs and ways of life are shared by all of its members. These include strict adherence to religious principles, observance of God’s commandments as they are interpreted in the Talmud and in later rabbinical literature according to the Ultra-Orthodox interpretation (Friedman and Hakak 2015; Shomron 2022), and perception of Jewish law as pertaining to all aspects of life (Engelman et al. 2020; Haller et al. 2023). It has been suggested that Orthodoxy, and its Ultra-Orthodox offshoots, are movements based on a conservative reaction to the modernization and secularization crises as well as to the increasing prominence of liberal religious groups, most of all Reform Judaism, which have opposed traditional Jewish society since the turn of the nineteenth century (Katz 1992). As noted, Ultra-Orthodoxy has been characterized foremost among them by strict religiosity and a solid commitment to Torah study (Katz 1992, 1997; Friedman 1991). One highly prominent attribute that sets the Ultra-Orthodox apart from other religious sectors in Judaism is the attitude toward Zionism. Whereas other religious sectors such as Dati-Leumi (a social and religious group in Israel that advocates the religious Zionist ideology, including leading an observant lifestyle alongside active integration into Israeli society) and Haredi-Leumi (who are a group from among the national religious population, characterized by conservatism and high halachic strictness compared to others within the national religious population) are Zionist by definition, the Ultra-Orthodox define themselves as non-Zionist and tend to avoid military service (Brown 2017). As of 2020, the Ultra-Orthodox community in Israel numbered approximately 1,175,000 people, representing 12.6% of the total population. Its natural growth rate is approximately 4% per year, as opposed to only 1.9% among the general population (Malach and Kahner 2020).

The prominent characteristics of Ultra-Orthodox society are the struggle to preserve its character as a minority with a distinct identity and its traditional and isolationist approach, and its rejection of modern norms (Amran 2015). In Hebrew, Ultra-Orthodox Jews are referred to as “Haredim” or tremblers, which one of the proposals for its origin claims to come from the Book of Isaiah (66:5) “Hear the word of the Lord, you who tremble at his word.” This personal and communal trembling is intended to abide by God’s will and the most common fear that is present all the time is from losing the traditional Jewish way of life (Friedman 1991). From the very definition of the community’s Hebrew name, one can infer this community’s most basic concern: the fear of losing its unique traditional identity. Of course, the community goal is not based only on a negative act of “protection from the other” but also on the positive act of “living according to”. Thus, the listed actions such as segregation are not only out of fear but also out of convenience. Among the motifs of this characterizing trepidation is the fact that many from among the Ultra-Orthodox population will only reside in neighborhoods where the Ultra-Orthodox character is preserved. This choice facilitates the upbringing of children culturally sheltered in a socially Orthodox environment and minimizes outside influences. According to Kaplan and Stadler (2012), this isolation is characterized not only geographically but also in the field of communication. Since the 1980s, there has been a trend toward strengthening the Ultra-Orthodox community in various ways, particularly in attempts to increase its presence in Israeli society’s spheres of activity (Zicherman 2017).

The definition of ‘Ultra-Orthodox’ is somewhat of a challenge owing to its amorphous nature. It is difficult to draw the boundaries of Ultra-Orthodoxy clearly and to determine those who are included and those who are not. The importance of this definition is not limited to theory or academics. In Israeli reality, where belonging to the Ultra-Orthodox population also involves governmental (drafting into the IDF), bureaucratic, institutional (Orthodox educational institutions and admission to Ultra-Orthodox campuses in academic institutions), political (parties and municipal coalitions), and social (community membership including all of the community institutions), the question of “Who is Ultra-Orthodox?” is of practical importance.

The Central Bureau of Statistics—the main source of demographic data in Israel—offers four different methods for identifying members of the Ultra-Orthodox population in Israel (Gal 2015):

- Identification by geographic distribution based on voting patterns for Ultra-Orthodox parties;

- Identification by type of education: when the individual filling CV or any other governmental form includes studying in an Ultra-Orthodox yeshiva (“Haredi Yeshiva Gdola”) registered in the Committee of Yeshivas in Israel;

- Identification by self-definition in a social survey: this is a subjective definition by replying to a question about the level of religiosity, where one of the options is “Ultra-Orthodox”;

- Identification by type of education: according to the governmental administrative files, students in educational institutions under Ultra-Orthodox supervision.

Orthodox Jewish law (halakha) grants a great deal of power to the community in that the individual cannot adequately fulfill the commandments without some form of community membership (e.g., prayer with a quorum of ten men). This point, which is inherent in many aspects of the Orthodox Jewish religion, strengthens the role and importance of the community (Leshem 2011). Naturally, community communication is important as it connects all parts of the community into a collective. Mass communication in such a community can play a major role in the formation of the collective (Friedman 2019).

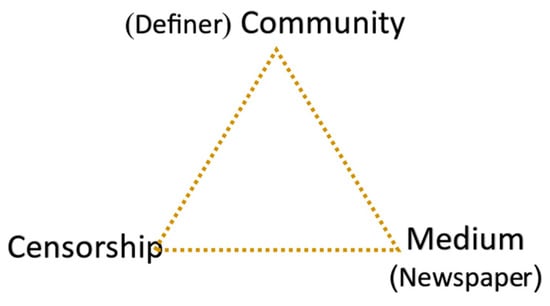

The body of research conducted on Ultra-Orthodoxy media and journalism and knowledge about the roles of the Ultra-Orthodox media is still insufficient (Kaplan 2001). Previous studies tended to deal with specific phenomena such as unique Ultra-Orthodox media such as pashkevilim (Rosenberg and Rashi 2015); specific challenging times such as the COVID-19 outbreak (Shomron 2022; Shomron and David 2022); and the conflict in Ultra-Orthodox society regarding the increased use of new media (Campbell 2011; David and Baden 2020; Neriya-Ben Shahar 2020). This research, which presumably for the first time, deals with the bases of the Ultra-Orthodox Media by trying to point out the role of its existence (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The community creates a medium to define its members. The community controls the media using censorship by the medium. The medium defines the community and its purpose through censorship.

4. The Ideological Basis for the Creation of Ultra-Orthodox Journalism

As can be found among national minorities and immigrants, sectoral journalism is a worldwide phenomenon that owes its existence to such factors as audience convenience and its feeling of exclusion with respect to the mainstream media, which does not answer to the needs of those populations (Rigoni 2005). Studies point to the connection between the feeling of exclusion of a population and the tendency to create alternative media (Waltz 2005). The existence of sectoral journalism also has an economic aspect (Dewenter et al. 2016). In the end, the financial commitment of the members of the sector determines the survival of the medium. The minorities’ feeling of isolation and lack of assimilation into the majority culture is responsible for the high rate of dying of sectorial journalism (Elias and Seltzer Shorer 2007; Rigoni 2005; Wang 1995).

We suggest that the Ultra-Orthodox media differs significantly from other sectoral media in their base, creation, and development. Moreover, from their beginnings in the nineteenth century and their growth and development alongside that of general journalism, the rabbinical establishment has been overwhelmingly opposed to it.

The reasons behind the rabbis’ objections to secular journalism varied:

- The wasting of time that should be devoted to Torah study—the Ultra-Orthodox believe in using time for studying Torah and spiritual activities and consider most of the functions of communication to be illegitimate and unnecessary. The social roles of cultural transmission and socialization might, but should not, be supplied by the media, but rather by religious practice and activity (Hakohen 1925);

- The negative influences of media content—the secular media publicizes opinions and ideas quickly and with minimum oversight, which is a danger to a conservative and faithful society (Wolfson 2003). From the Ultra-Orthodox point of view, secular journalism, from its inception, was seen as a form that mocks and degrades everything holy and that reports and indirectly encourages the worst of sins (Letters of the Hakohen 1925; Leibovitz 1954), among them the lack of modesty (Kanievsky 1980) and the hate of observant Jews and their rabbis (Sela 2011).

After the rabbis lost the battle against their students’ use of media, they changed course and created alternative Jewish Ultra-Orthodox media, which are different in some perspectives from both the general and the non-Orthodox Jewish media. Generally, journalism springs out of a positive outlook on media and a wish to provide a better and more focused media experience (Dewenter et al. 2016), but the Ultra-Orthodox media were created out of a built-in disdain for media in general, and the secular media in particular (as will be specified later). The Ultra-Orthodox media were created in the face of profound negative feelings toward the media as an alternative and a filter against the dangers of the general media (Friedman 2019). Moreover, whereas “regular” niche media mostly (at least in the early decades of the 21st century) grow from the bottom up, from out in the field, in the Ultra-Orthodox case, the instruction comes from the “top”—from the spiritual leadership backed up by the Jewish sources.

Despite this ideological background, the creation of Ultra-Orthodox journalism did not proceed without opposition. Many rabbis and community leaders actively opposed the new Ultra-Orthodox newspapers, among them the Amshinov Grand Rabbi (Wolfson 2003); Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan, also known by the name of his book Hafez Haim (Zechor Lemiriam); the Sfat Emet Gur Grand Rabbi (Wolfson 2003); and the Nikolsburg Grand Rabbi (Israel Saba 1964). Today as well, there is opposition in the Ultra-Orthodox streets to Ultra-Orthodox journalism, which appears from time to time in different forms, one of the more prominent ones being the street posters or “pashkevils”.

5. The Creation of Ultra-Orthodox Journalism as a Means of Preserving the Community

As noted, it has been suggested that Orthodox and Ultra-Orthodox journalism is a reactionary response to non-Orthodox Jewish journalism (Keren-Kertz 2017). Some studies have identified Shomer Tzion Haneman (Altona 1846–1856) as the first Ultra-Orthodox newspaper (Keren-Kertz 2017).1 Its editor, Rabbi Ettlinger, noted his clear intention “to strengthen the interest of Orthodox Judaism” in the subtitle.2 Despite the Orthodox identity of the editor and the clear definition of its goals, the newspaper, which was also created owing to a censorial need, was attacked by various rabbis and other members of the Ultra-Orthodox establishment. These opponents were convinced that journalism, which symbolized one of the signs of modernity, would lead Orthodoxy down a slippery slope (ibid).

Despite the opposition to Ultra-Orthodox journalism in particular and any journalism in general, the former continued to develop. The Ultra-Orthodox Jews of Hungary began to publish; The Jews of Hungary (1868) and Sheves Achim (1872–1880) were founded as a reaction to what was seen as a takeover of the Jewish Communities’ Congress in 1868 in Budapest by the Neologs (those Jews who sought to reform the religion) (ibid). In Krakow, Machzikai Hadas—the True Orthodox Jewish Newspaper established in 1879 was characterized by a sophisticated Hebrew and was intended not for the founder’s home crowd—the followers of the Belz Grand Rabbi and Rabbi Shimon Sofer—but rather for the enlightened traditional Ashkenazi Jew. The newspaper attacked the Enlightenment Shomer Yisrael and published positive reports about the activities of the branches of the Ultra-Orthodox Machzikai Hadas. On the one hand, the paper adopted innovations from the Enlightenment and non-Jewish newspapers, but, on the other, it attacked others (such as boys’ schools which incorporated general studies along with religious ones) (ibid).

The ideological journals associated with the beginning of the Enlightenment (Haskalah) that began to appear during the eighteenth century were designed to spread ideology and attract supporters. The appearance of this kind of journalism was a clear sign of the effect of modernity on Jewish society (Bartal 1992), which used journalism as a means of communication and as a tool to convey messages, opinions, ideology, and different outlooks within Jewish society (Limor 1996; Kutz 2013).

Those journals threatened the preservation of the traditional community and Ultra-Orthodox ideology (Cohen 2017). The innovative trends of the Haskalah movement, the organized labor (the “Bund”) movement, and the secular Zionist movement all threatened traditional Jewry, which in turn felt that it was forced to defend itself. The different leaders of the various groups, each one in his way and occasionally working together, came to a strategic conclusion that the best way to face the challenges of the times was through modern tools such as journalism (Kaplan and Stadler 2012). The source of this strategy can be found in the biblical story of Benaya Ben Yehoyada, King Solomon’s biblical hero, about whom Scripture says, “And he stole the spear from the hand of the Egyptian, and he smote him with his spear” (II Samuel:23, 21; I Chronicles:11, 23). The actual meaning is that one must use the enemy’s weapon against him, for that is the only way to defeat him. This was the approach of the prominent Ultra-Orthodox leaders and journalists behind the creation of Ultra-Orthodox journalism—the Gur Grand Rabbi (Mintz 1950), Rabbi Shmuel Levin (2012) and Leibovitz (2014), the editor of Hamodia (Druck 1990), the editor of Yated Ne’eman (Friedman 1992, the editor of Hamevaser (2019), and the editor of Hapeles (2012).

Ultra-Orthodox journalists and leaders talked about the early days of Ultra-Orthodox journalism and the reason for it, which they agreed was a reaction to the “ravages of time and Zeitgeist.” “To fight against freedom (i.e., the departure from Jewish law and tradition) with the weapon of freedom itself, that is, with newspapers and literature” (Mintz 1950). For all the years of their existence, the individuals behind the Ultra-Orthodox newspapers have preserved this sense of being essential and accepting of reality. Editorials in these newspapers continue to be in a clear apologetic style as a justification for their existence to this day (see, e.g., Hamodia (Druck 1990), Yeted Ne’eman (Friedman 1992, Hamevaser (2009), Hapeles (2012; Levin 2012; Leibovitz 2014)). These editorials are centered on ideological and sociological (preserving the community) justifications for the newspapers’ existence. Since the media are frequently attacked by the rabbinical leadership, the argument in favor of the media as tools for conveying information about what is happening in the world or as means for transmitting messages from the leadership to the masses will never be acknowledged. From its beginnings until today, the ideological justification for the existence of Ultra-Orthodox journalism has been the same: a defense system to counter the threats against the Ultra-Orthodox community’s integrity and traditional way of life (Hamevaser 2009): “To guard the Torah and Judaism” (Leibovitz 2014). The most conspicuous expression of this spirit of defense against the outside world is each newspaper’s strict and independent censorial board (Figure 2).

6. Methodology

The research methods in this study included content analysis, narrative analysis, and production analysis spread over two dimensions—historical research and contemporary research. The first was based on a narrative analysis through a review of the literature concerning the foundation and the development of Ultra-Orthodox journalism. Each of the printed daily newspapers that were established during the era of the research published an editorial article regarding the reasons and motivation for its establishment. Those articles were collected. The dates of the article’s publicity were usually in the first month of the newspaper’s establishment. Another article was always published years later—on the newspaper’s anniversary. Those two articles from each newspaper were sampled (the specific date of each article is elaborated on in the bibliography). The study was aided by historical text analyses: religious, public, and journalistic texts dealing with the motives and reasons for the establishment of the Ultra-Orthodox press despite the Ultra-Orthodox leadership’s opposition to any sort of media. The studies’ analyses used in this research are elaborated on in the bibliography section.

The second part of the study examined the daily Ultra-Orthodox press printed in Israel between the years 1980 and 2020. The methods included systematic literature analyses, which involve identification, evaluation, and systematic interpretation of literature relevant to research areas and questions (Kitcharoen 2004), and interviews. Systematic literature analysis has five steps: (a) defining the scope of the corpus; (b) conceptualizing the topic; (c) locating the relevant literature; (d) analyzing and synthesizing the literature; and (e) determining the research agenda (Vom Brocke et al. 2009). Identification of the relevant literature for the study was accomplished by a search for editorials in all three daily Ultra-Orthodox newspapers (Yated Neeman, Hamevaser, and Hapeles) dating from the times they were founded, detailing the circumstances of their establishment, their purpose, and their stated objectives. In all, six such texts were analyzed: two for each newspaper. The first text was an editorial from the period of the newspaper’s establishment and the second was an editorial that was published years later (usually to mark the newspaper’s anniversary), which provided a retrospective on the circumstances that motivated its establishment. The specific dates of those articles’ publicity are elaborated on in the bibliography section. These articles were chosen because they provided declarations of the intentions of the founding fathers of Ultra-Orthodox journalism. In addition, various texts were collected, and interviews and articles were published in various media in which the establishment of Ultra-Orthodox media was discussed and explained by their founders or industry personnel.

To complete the research picture, a production analysis was implemented, part of which was carried out through participant observation over several years among a large and diverse part of the Ultra-Orthodox media and through semi-structured interviews with members of the interpretive community of Ultra-Orthodox media. Many empirical and successful studies in the social sciences have been based principally on information collected through indepth interviews (Aberbach and Rockman 2002). Such interviews are important while providing new directions for further research, with complete transparency both towards the research and towards the interviewees (Berry 2002).

The interviews were all conducted in an ethical manner. The interviewees were asked to sign an informed-consent document, and the interviews, which were carried out respectfully, were directed toward significant and authentic issues, were never intentionally intrusive, and did not confront the interviewee with facts or the interviewer’s way of thinking. Temporary suspension of disbelief is an interview technique by which the interviewer accepts the interviewee’s version and places doubts, contradictory information, or personal positions regarding the subject in ‘parentheses’ (Lieblich and Wiseman 2009).

The interviewees were chosen both from a range of individuals involved in Ultra-Orthodox media and from among different media and Ultra-Orthodox society experts, the latter to provide an external point of view. The guidelines for the selection of the interviewees were to find those who were behind the establishment of the Ultra-Orthodox daily newspapers or at least those who were knowledgeable regarding the process of the establishment of the newspapers. A total of fifteen Ultra-Orthodox media personnel were interviewed from a range of positions in Ultra-Orthodox media, including publishers, editors, and journalists. The interviewees had various community affiliations so that there was at least one representative of each subcommunity surveyed in this study. The age range of the interviewees (twelve men and three women) was between 32 and 83.

The interviews were semistructured. A separate questionnaire was prepared in advance for each interviewee adapted to his/her expertise, understanding, and knowledge. Interviewees were encouraged to expand the scope of the interview to contribute toward completing the research mosaic. The questionnaire revolved around the motivations for establishing the newspaper and developing Ultra-Orthodox media in general. The questions focused on the background and circumstances of the founding of the newspaper and the reasons for the communal diversity of the Ultra-Orthodox press.

7. Findings

The study’s findings, proven mostly by the interviews and backed-up by the text analysis and the historical facts, delineate a triangle of influence: newspapers, community, and censorship. The Ultra-Orthodox newspaper was created in response to an immediate social-communal need. As the historical part of the study proved that the roots of Ultra-Orthodox journalism were in the middle of the nineteenth century, the founders of Ultra-Orthodox journalism identified a threat of disintegration in the traditional European Jewish community owing to the infiltration of the general media and its significant influence. The solution to the situation was to create an Ultra-Orthodox newspaper to preserve the community, and its primary means for doing so was and is censorship (both externally—the general media—and internally—media outlets belonging to other communities with different agendas).

The evolution of Ultra-Orthodox media against the backdrop of censorship is supported on two legs: historical and contemporary. Historically, the conception and birth of Ultra-Orthodox journalism were engendered by a perceived need to censor general media outlets to protect and preserve the community. From a contemporary perspective, as was proven by the text analysis of over the four decades on which this study focused, notable development took place in connection with the Ultra-Orthodox media, owing primarily to the necessity to control the information that reaches the Ultra-Orthodox community and the need for censorship as a community definer of the different factions within it.

8. The Ultra-Orthodox Media Development Model

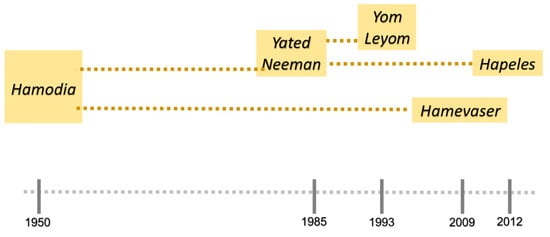

The findings of the present study draw a historical-developmental model as it appears mostly from the interviews but is strongly backed up by the text analysis and the historical facts (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The development of the Ultra-Orthodox daily newspaper on a time scale.

Initially, an Ultra-Orthodox newspaper caters to a large part of the community. A subcommunity eventually feels a need for a more distinct self-definition and reacts by creating a new newspaper. The members of that subcommunity abandon the old newspaper (usually owing to a lack of representation of its particular self-definition, which is reflected in the existing newspaper’s censorial board). The group creates a new newspaper with a new independent editorial and, more importantly, a new censorial line. The new newspaper adjusts its output according to the ideological boundaries of the subcommunity that created it, which in turn defines itself by the social codes that are introduced by the new newspaper. The old newspaper, which was forsaken by those who left it, changes its censorial line, being more stringent in some issues (to deny the claims of the dissenters) and more lenient in others, and it too fixes itself to the ideological boundaries of the community members that remained its consumers. At this point, a group from within that aligns with the new publication feels that the editorial and censorial line of the new paper does not represent its values and leaves to create still another new newspaper with different editorial and censorial lines, and so on. The result is a new subcommunity defined by the creation of a new publication. This mechanism can be seen in the main sub-communities of Ultra-Orthodox society. Though it should be restricted by applying to the fact that a subcommunity can redefine itself without having a newspaper as its social definer.

During the period under study, one can see two simultaneous processes occurring in tandem (Table 1): the first is the dwindling of circulation, increasing focus on speaking to a more limited audience, and the escalating censorship in accordance with the more targeted audience of each publication, and the second is the continual strengthening of the censorial filter and its scope. The two processes are intertwined and feed each other.

Table 1.

The Daily Ultra-Orthodox Newspapers Printed in Israel in 2022.

The reduction of the target audience of each one of the publications; until the 1980s, the oldest Ultra-Orthodox newspaper in Israel, Hamodia (created in 1948), catered to all the Ultra-Orthodox factions. In 1986 Yeted Ne’eman was founded for the Lithuanian and Sephardi factions and Hamodia was left with a target audience limited to the Hasidic community and shrunk to a third of its original size. Hamevaser, founded in 2009, then split the Hasidic community in two: those who were politically organized under the Shomrei Emunim faction, who moved to Hamevaser, and those who politically aligned with the Gur Hasidic sect, which remained Hamodia’s target audience (approximately a sixth of the original target audience).

A similar process occurred with Yated Ne’eman, created in 1986 by the leaders of the Lithuanian faction who objected to Hamodia’s policy regarding the coverage of the Chabad movement’s activities. Chabad is a Hasidic sect whose messianic activities garnered much opposition among the Lithuanian circles at the time. Hamodia covered its activities despite the opposition of the Lithuanians, who did not have control of the publication’s editorial line. The Lithuanian leaders felt that Hamodia no longer defined them and that they had to create another publication within the Ultra-Orthodox community (Levi 1988). Yeted Ne’eman’s role was to censor activities and opinions that opposed the Lithuanian rabbis’ line. Its censorship board was different from that of Hamodia, stringent on matters of ideology, its approach to Zionism, the attitude toward students of Torah (Friedman 1992), and the value of Torah study, and more lenient in matters of modesty, gender, and attitude toward women.

From the start, Yeted Ne’eman’s readership was more limited than Hamodia’s at its inception—consisting solely of the Lithuanian and Sephardic sects. Subsequently, it also experienced splits and a reduction in its target audience owing to censorship or exclusion. In 1993, Yom Leyom (later Haderech) was created for the Sephardic faction, and in 2012 the members of the Bnei Torah faction broke off and founded Hapeles. Yated Ne’eman was left with only a small readership, the main sect of Lithuanians, who are aligned with the Degel Hatorah political party.

The parallel process of refining guidelines and deepening censorship coincided with the communal fractions described above. Hamodia became more conservative in connection with issues of technology (e.g., blurring a computer in the background of a picture depicting a city council meeting in the Ultra-Orthodox city of Elad [20 December 2018]), women, sexuality, relations between men and women, and modesty (e.g., in an advertisement for diapers (17 February 2016) the infant was wearing pants over the diaper, while in other Ultra-Orthodox papers, the baby was not wearing pants). Women were no longer mentioned by their first names, only by their first initials (e.g., former Minister Tzipi Livni would appear as “T. Livni”). The split between the Hasidic communities, which caused them to splinter from Hamodia and create Hamevaser, led the dissenters to form a new censorial line, despite their affiliation with the Hasidic audience of Hamodia and their official subjection to the same codes of ethics and Jewish law.

A unique phenomenon of censorial expansion occurred alongside the split and creation of Hamevaser within the old Hamodia of all places, which stopped referring to the Gur sect, the group that controls the publication and whose members make up the publication’s core readership, by name.

Yeted Ne’eman, which follows a bold line of censoring specific Hasidic approaches, has not been immune to censorial changes. Indeed, as opposed to Hamodia, it is less strict in matters of gender, for instance, publishing women’s first names; but it censors notice, and stories that pertain to the central tenants of Lithuanian ideology, such as the activities of the Chabad sect, which is seen as heretical; members of the Ultra-Orthodox community in academia; and hostility toward Torah scholars and students (Friedman 1992). Later, when the Sephardic faction split from the Lithuanians (which was reflected in the creation of the Yom Leyom (1993) and Haderech (2017)), stories that pertained to Sephardim, its rabbis, and the political party Shas were censored. The split within the Lithuanian faction and the creation of Hapeles (2012) by the Jerusalem Faction, which is extreme in its opinions regarding opposition to the State of Israel and compulsory military service for yeshiva students, led to a change in both publications’ editorial lines: Yated Ne’eman stopped censoring stories about Chabad and the representatives of the Ultra-Orthodox Sephardim, Shas, and began, instead, to censor events and Lithuanian rabbis who supported extreme actions against the state. At Hapeles, the editor changed the censorial line that he followed as the editor of Yated Ne’eman and stopped censoring communities that now became its political allies (Gur), and instead censored the Lithuanian mainstream and its moderate line regarding state institutions.

The young Hamevaser and Hapeles newspapers were created out of a will to focus on their target audience rather than to appeal to the whole target audience of the newspaper from which they broke off. They did so by expanding censorship. Hapeles censors activities that it sees as too liberal or as cooperation with bodies that are not Ultra-Orthodox or are associated with the state. Hamevaser, which was founded owing to claims of political censorship of its people in Hamodia, censors stories about inter-sect politics that may harm the readership’s interests, on the one hand, and, on the other, allows the publication of stories that would be censored by Hamodia owing to its overconservatism (regarding matters of Zionism, women, politics, and more) (Table 1).

9. The Motive for the Creation of an Ultra-Orthodox Newspaper—The Communal Factor

“Our community needs its own newspaper that can express our different opinion” (Levi 1988) declared the leaders of the Lithuanian community on the eve of founding the newspaper Yad Na’am when they felt that the old “informer” did not allow them to do so. Three of the four printed Ultra-Orthodox dailies in Israel were established during the research period (Yeded Na’aman, Hamevaser, and Hapeles) and all of them were established against this background: a community that felt that it was not reflected in the existing newspapers and thought that it needed a new independent tool. The interviewees in this study and the editorials articles in the newspapers tended to see a direct connection between communal and censorial reasons for the establishment of the newspaper.

“Now the Bnei Torah [people of the Torah—Lithuanaian sector. E.F.] have their own expression […] It’s a newspaper like the other newspapers, but no! It’s the Bnei Torah newspaper. It’s different. Very unique, even rare. […] Yeded Na’eman doesn’t want to be seen as the other newspapers […] Undoubtedly, the information will be formatted in such a way that it can be put on the table of the people of the Torah.”(Friedman 1992)

The developmental model that this study outlines alongside the historical review of the development of Ultra-Orthodox media indicates a strong motive of social-community self-determination as the basis for establishing a new Ultra-Orthodox media. It can be said that censorship defines the media—both as belonging to the Ultra-Orthodox sector and its reputation among the target audience. The findings show that the establishment of the Ultra-Orthodox publications over the past four decades has always been carried out under an ideological-spiritual guise but, in practice, it has always been due to a lack of satisfaction with the existing censorship board and the wish to modify it. It is easy to discern the pattern of the creation of the Ultra-Orthodox daily publications during this period. In the beginning, there is a paper that caters to the broader community, including several subgroups; later on, a certain subcommunity becomes dissatisfied with the censorship in the publication with which they affiliate, and after that, they split off and create a new newspaper. The new publication is indeed subject to the basic rules of the accepted Ultra-Orthodox censorship but free to adopt further specifically directed rules (stringent and lenient compared to the parallel outlets) concerning censorial categories that are not included in the core guidelines of Ultra-Orthodox censorship. The creation of the media outlet constitutes a censorial instrument, which in turn is used as a social definer. The Ultra-Orthodox individual subscribes to the new publication out of a need for the social definition that comes from the censorial line of the new newspaper rather than out of a need for one of the roles that past studies assigned to communication; the information that is reported in the newspapers would get to him by other means (internet, social media, and word of mouth—a widespread practice in Ultra-Orthodox society).

With all the importance that the Ultra-Orthodox community sees in internal differentiation, in independent self-determination, and in establishing a press that will serve these needs, there is still the fear of dangerous conflicts that might be followed by communal conflicts. This is how the editor of the Hamevaser (2021) described the arguments against the establishment of the newspaper:

There were those who wanted to say that the establishment of the newspaper could cause the separation of hearts, God forbid. However, after some time, in hindsight, the complete opposite became clear. Hamevaser was a vessel holding blessing and peace, but goodness and kindness came out of the establishment of the newspaper, and this had far-reaching implications for the strengthening and love of Israel.

As the interviewees explained, there is always the fear that the ruling hegemony in the community will attack the creation of a new newspaper as a divisive move and as one that will cause fratricidal conflicts. The role of the new newspaper is to define the new independence of its community but without engendering new hostilities and disputes. The sources on which this research is based considered the role of the censor to be the first and the community’s uniqueness as the main reason for the establishment and existence of the Ultra-orthodox newspaper. The model of Ultra-Orthodox media development was outlined alongside the historical review of the development of Ultra-Orthodox media indicating a strong motive of social-community self-determination for establishing a new Ultra-Orthodox medium. It can be said that censorship defines the media—both as belonging to the Ultra-Orthodox sector and its name, character, and reputation among the target audience.

10. Discussion and Conclusions

Previous research has proven that religion is also a social determinant (Ysseldyk et al. 2010). As the finding of this study has shown—in Ultra-Orthodox society there are reciprocal relationships in which the relationship is symbiotic—the social definer also helps preserve the religion (Brown 2017). The social definition in Ultra-Orthodox society has become a very important tool in the community’s self-preservation. Owing to its importance, this tool has become a means to an end and has value in Ultra-Orthodox society. Many practices and social phenomena were created and preserved to preserve the communal uniqueness outwardly and inwardly: the clothing styles, the various educational institutions, and the synagogues.

The perception of Ultra-Orthodox differentiation is necessary for the community’s self-preservation facing the threats that other communities launch alongside the modern era. The Ultra-Orthodox society’s use of the media as tools to strengthen differentiation can be characterized by Bourdieu’s theory of differentiation, which sees the social role of culture and art in marking social differences and setting boundaries between groups within the framework of status and prestige struggles between social sectors (Regev 2011). Dimaggio’s theoretical model (DiMaggio 1987), according to which the greater the degree of social heterogeneity, the more differentiated the artistic sorting system, definitely characterizes Ultra-Orthodox society and media in which the correlation between the multiplicity of communal shades and those of the media can be discerned. The study by Katz-Gro and Shavit (1998) revealed that in Israel another dimension of inequality is added owing to a religious lifestyle that affects cultural consumption. This conclusion is consistent with what emerges from this study according to which Ultra-Orthodox society differentiates the different types of newspapers according to the community-religious division and not according to other divisions (ramat haim, elitism, etc.). This case study confirms the theory of differentiation as a marker of social boundaries, which is also reflected in the field of communication.

This conclusion sharpens the understanding of the importance of communication research beyond its discipline and its impact on other fields in the social sciences since the study found that communication tools are used for additional functions apart from the communication research method or the functions of communication as they are subscribed in the research literature.

The present research defines for the first time the role that the media plays in the self-definition of an individual toward himself and his place in society and the community. It may be considered theoretical, but it has practical aspects; through it, many phenomena in the world of communication will be explained. First of all, the question of the future of the printed press. (Limor 2012). Why do new printed newspapers continue to be published even in the online age? The claim that emerges from this study is that as long as there are communities that need self-determination through the printed newspaper, the printed press will continue to exist. This study also defines for the first time the use made of censorship as a community and social-definition tool. Censorship is not just used to prevent publication that may harm the common good or its values. It also shapes the values of the community and its members and eradicates their differences in the public sphere.

The methodological limitations of this research were: first, the research field was limited to the Ultra-Orthodox daily printed newspapers and no other printed newspapers or other media were included in the study. Second, the contextualization of the findings, mostly in the realm of content and producers, as the study does not explore or test the audiences. Thus, while the study could illuminate the objectives and beliefs of the interviewees (producers), it does not reveal the experiences of the audience (society). Its theoretical limitations were focused on the sociological aspect of the media as a community definer and did not deal with the part of censorship and its part in the same phenomena. Another theoretical limitation is the theological background concerning all the issues this study dealt with. Although the research was among a very religious community in which the theological aspects extremely have influence, due to obvious limitations, the theological background and its consequences will be dealt with in the other paper to come.

The current study points to a phenomenon that is probably not unique to the Ultra-Orthodox media, even if it is very prominent there. Future studies should examine this phenomenon—the media as a definer in other means of communication—contemporary and historical, and try to point out this phenomenon in other societies and at different times.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, E.F.; writing—review and editing, T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Although the first Hebrew newspaper Pri Etz Haim dealt with Torah and can be considered Ultra-Orthodox. |

| 2 | It was Rabbi Ettlinger who first used the term “Orthodoxy” to denote this group (Tzimerman 1996). |

References

- Aberbach, Joel D., and Bert A. Rockman. 2002. Conducting and Coding Elite Interviews. Political Science & Politics 35: 673–76. [Google Scholar]

- Amran, Meirav. 2015. Media for Spreading Faith as Signs of Continuity and Permutation in the Haredi Society. Kesher 47: 114–26. [Google Scholar]

- Antasapalio, George. 2020. Censorship. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/censorship (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Bartal, Yackov. 1992. “Forerunner and informer to a Jewish man”: The Jewish press as a channel of innovation. Cathedra 71: 176–65. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, Jeffery M. 2002. Validity and Reliability Issues in Elite Interviewing. Political Science & Politics 35: 679–82. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Benny. 2017. The Ultra-Orthodox: A Guide to Their Beliefs and Sectors. Jerusalem: Am-Oved and the Israel Democracy Institute (Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidy. 2011. Religion and the Internet in the Israeli Orthodox Context. Israel Affairs 17: 364–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Yoel. 2017. The media challenge to Haredi rabbinic authority in Israel. ESSACHESS-Journal for Communication Studies 10: 113–28. [Google Scholar]

- David, Yossi, and Christian Baden. 2020. Reframing Community Boundaries: The Erosive Power of New Media Spaces in Authoritarian Societies. Information, Communication & Society 23: 110–27. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, Nathaniel, and Michael Casper. 2021. A Fortress in Brooklyn: Race, Real Estate, and the Making of Hasidic Williamsburg. New-Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dewenter, Ralf, Ulrich Heimeshoff, and Tobias Thomas. 2016. Media Coverage and Car Manufacturers’ Sales. Dusseldorf: Dusseldorf Institute for Competition Economics, p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P. 1987. Classification in art. American Sociological Review 52: 440–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druck, Moshe Akiva. 1990. Bless the One Who Kept Us Alive and Preserved Us Until This Time. Hamodia 11: 12021. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, N., and M. Seltzer Shorer. 2007. To Surf Without Borders: Online Journalism of Immigrants from the USSR in Israel. In Journalism Dot Com Online Journalism in Israel. Edited by T. Schwartz Altschuler. Jerusalem and Be’er Sheva: The Israeli Institute of Democracy and the Borda Center for New Media, pp. 147–76. [Google Scholar]

- Engelman, Joel, Glen Milstein, Irvin Sam Schonfeld, and Joshua B. Grubbs. 2020. Leaving a covenantal religion: Orthodox Jewish disaffiliation from an immigration psychology perspective. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 23: 153–72. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Efi. 2019. Euphemisms and Clean Language–Oversight and Reality Building Systems in Haredi Media: Characteristics and Patterns. Master’s Thesis, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Israel. 1992. Why a Haredi Newspaper? In Yearbook of the Editors and Journalists in Journals in Israel 5752–5753. Tel Aviv: The Israeli Union for Periodic Journalism, pp. 165–69. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Israela, and Yochay Hakak. 2015. Jewish Revenge: Haredi Action in the Zionist Sphere. Jewish Film & New Media 3: 48–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Menachem. 1991. Haredi Judaism–Sources and Central Characteristics. Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, pp. 6–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Reuven. 2015. The Ultra-Orthodox in Israeli Society–Update, 2014. Haifa: Shmuel Ne’eman Institute and The Technion. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, D. 2007. The Poverty and Market Behavior of Ultra-Orthodox Society. Policy Studies 4. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/4024/ (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Hakohen, Rabbi Israel Meir. 1925. Zechor Lemiriam. Piotrkow: C. H. Falman Printing. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, Rachel, Louis W. C. Tavecchio, Geert Jan. J. M. Stams, and Levi Van Dam. 2023. Educate the Child According to His Own Way: A Jewish Ultra-Orthodox Version of Independent Self-Construal. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, William Dolores Albarracín, Alice. H. Eagly, Inge Brechan, Matthew J. Lindberg, and Lisa Merrill. 2009. Feeling Validated Versus Being Correct: A Meta-Analysis of Selective Exposure to Information. Psychological Bulletin 135: 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, William, Kyle Richardson, Gregory K. Tortoriello, and Alison Earl. 2020. ‘You Are What You Read:’ Is Selective Exposure a Way People Tell Us Who They Are? British Journal of Psychology 111: 417–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, Michael A., Janice R. Adelman, and Robert D. Blagg. 2010. Religion in the face of uncertainty: An uncertainty-identity theory account of religiousness. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel Saba. 1964. Netanya: Sanz Yeshiva Library. p. 956. Available online: https://hebrewbooks.org/13418 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Kanievsky, Rabbi Yackov Iarael. 1980. Kraina Digrata. Bnei Brak: Netzach Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, K. 2001. Media in the Israeli Haredi Society. Kesher 30: 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Kimy, and Natan Stadler. 2012. The Changing Face of Haredi Society–From Survival to Presence, Strengthening and Self Confidence. In From Survival to Consolidation: Permutation in the Haredi Society and Study. Edited by K. Kaplan and Natan Stadler. Jerusalem: Van Leer Institute Press and Hakibbutz Hameuchad. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Yackov. 1992. Halacha in Trouble: Roadblocks on the Road to Orthodox Formation. Jerusalem: Magnes. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Yackov. 1997. The Tear That Did Not Heal: The Orthodox Departure from the Hungarian and German Communities. Jerusalem: Zalman Shazar Center. [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Gro, Tali, and Yossi Shavit. 1998. Lifestyle and Classes in Israel. Israeli Socieologey A: 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Keren-Kertz, Menachem. 2017. The End of Orthodoxy in Galizia at the Turn of the 20th Century through the Eyes of the Haredi Newspapers Machzikai Hadas and Kol Machzikai Hadas. Kesher 49: 126–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kitcharoen, Krisana. 2004. The Importance-Performance Analysis of Service Quality in Administrative Departments of Private Universities in Thailand. ABAC Journal 24. [Google Scholar]

- Kutz, Gideon. 2013. News and History. In Studies in the Jewish and Hebrew Journalism and Communications History. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: Zionist Press and Tel Aviv University. [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell, Harold D. 1948. The Structure and Function of Communication in Society. New York: Cooper Square Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Leibovitz, Rabbi Baruch Dov. 1954. Birchat Shmuel, B. New York: Balshan Press, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Leibovitz, H. 2014. Two Years Since It Came Out: Rabbi Elyasiv Published a Letter of Support for the Hapeles. Bechadrei Charedim. Available online: https://bit.ly/2A0phDq (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Levin, Rabbi Shmuel. 2012. Recorded preaching on YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCzjePZc8PM (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Leon, Nissim. 2009. Gentle Ultra-Orthodoxy: Religious Renewal in Oriental Jewry in Israel. Jerusalem: Ben-Tzvi Institute (Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Leon, Nissim. 2016. The Ethnic Structuring of “Sephardim” in Haredi Society in Israel. Jewish Social Studies 22: 130–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshem, Yuval. 2011. Ultra-Orthodox Women Who Divorced Due to a Violent Partner: The Experience of Violence and Divorce Process. Graduate Degree thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, Amnon. 1988. The Haredim. Jerusalem: Keter. [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich, A., and H. Wiseman. 2009. Ethical Considerations in Narrative Research—Issues, Thoughts and Reflections. In Issues in Narrative Research: Quality Tests, Ethics. Edited by A. Lieblich, E. Shachar, M. Kromer-Nevo and M. Lavi-Ajae. Be’er Sheva: Ben Gurion University of the Negev. [Google Scholar]

- Limor, Y. 1996. The Raging Waves of Pirate Radio in Israel. Kesher 19: 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Limor, Y. 2012. Will Journalism Die? Globes. Available online: https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1000782751 (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Malach, G., and L. Kahner. 2020. Haredi Society Yearbook. Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute. Available online: https://www.idi.org.il/media/15500/haredi-2020.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- McQuail, Denis. 1984. With the benefit of hindsight: Reflections on uses and gratifications research. Critical Studies in Media Communication 1: 177–93. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail, Denis. 2010. McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory. London: Sage, pp. 492–500. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail, Denis, and Mark Deuze. 2020. McQuail’s Media and Mass Communication Theory. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, Binyamin. 1950. Our Rabbi from Gur. Tel Aviv: Shaarim. [Google Scholar]

- Neriya-Ben Shahar, Rebeca. 2008. Haredi Women and Mass Communication in Israel: Exposure Patterns and Reading Methods. Ph.D. dissertation, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Neriya-Ben Shahar, Rebeca. 2014. Gender, Religion, and New Technology: Outlooks, Stances, Opinions, Behavior Patterns, and Internet Use Among Haredi Women Who Work in a Computerized Workplace. Migamot 49: 272–306. [Google Scholar]

- Neriya-Ben Shahar, Rebeca. 2020. ‘Mobile Internet Is Worse Than the Internet; It Can Destroy Our Community’: Old Order Amish and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish Women’s Responses to Cellphone and Smartphone Use. The Information Society 36: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nöth, Winfried. 2013. Human communication from the semiotic perspective. In Theories of Information, Communication and Knowledge: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 97–119. [Google Scholar]

- Regev, Moti. 2011. Sociology of Culture: A General Introduction. Raanana: The Open University. [Google Scholar]

- Rigoni, Isabelle. 2005. Challenging Notions and Practices: The Muslim Media in Britain and France. Journal of Ethic and Migration Studies 31: 80–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, Hananel, and Tsuriel Rashi. 2015. Pashkevilim in Campaigns against New Media: What Can Pashkevilim Accomplish that Newspapers Cannot? In Digital Judaism: Jewish Negotiations with Digital Media and Culture. Edited by H. A. Campbell. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 169–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2017. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York and London: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Sela, Neta. 2011. Ultra-Orthodox Wikileaks: Gur Sect Going Mad. Zman Yerushalayim. Available online: https://www.makorrishon.co.il/nrg/online/54/ART2/222/611.html (accessed on 25 December 2022).

- Shomron, Baruch. 2022. The “Ambassadorial” Journalist: Twitter as a Performative Platform for Ultra-Orthodox Journalists during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Contemporary Jewry 42: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shomron, Baruch, and Yossi David. 2022. Protecting the Community: How Digital Media Promotes Safer Behavior during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Authoritarian Communities: A Case Study of the Ultra-Orthodox Community in Israel. New Media & Society, 14614448211063621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A., and K. Kaplan, eds. 2003. Israeli Haredim: Integration without Assimilation? Tel Aviv and Jerusalem: Van Lear Institute and Hakibutz Hamiuhad. [Google Scholar]

- Tzimerman, Akiva. 1996. The Trustworthy Guardian of Zion: The Religious Jewish Platform in Mid-19th Century Germany. Kesher 19: 131–34. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez, Alcides, Gretchen Montgomery, and Jeffrey A. Hall. 2019. Ethnic minorities’ social media political use: How ingroup identification, selective exposure, and collective efficacy shape social media political expression. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 24: 147–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vom Brocke, Jan, Alexander Simons, Bjoren Niehaves, Bjorn Niehaves, Ralf Plattfaut, and Anne Cleven. 2009. Reconstructing the Giant: On the Importance of Rigour in Documenting the Literature Search Process. Paper presented at the ECIS 17th European Conference on Information Systems, Verona, Italy, June 8–10; pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz, M. 2005. Alternative and Activist Media. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. 1995. History of Overseas Chinese Publications. In Proceedings of the 1995 International Conference on the Chinese Language Press and Communication of Culture. Wuhan: Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press, pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson, Yechzkel. 2003. “Journalism”: The Jewish and Hassidic Leaders on Journalism and Its Effects. The Hassidic World 100: 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Charles Robert, and Chester H. Page. 1959. Mass Communication: A Sociological Perspective. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Ysseldyk, Renate, Kimberly Matheson, and Hymie Anisman. 2010. Religiosity as Identity: Toward an Understanding of Religion from a Social Identity Perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicherman, Hayim. 2014. Black blue-White: A Journey into the Haredi Society in Israel. Rishon Le Zion: Yediot Acharonot and Chemed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Zicherman, Hayim. 2017. Israeli Ultra-Orthodoxy in Three Systems. Culture and Politics 17: 131–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2005. Religiousness and spirituality. Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 54: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).