1. Introduction

Theories of religious change have been caught between two opposing paradigms: secularization theory and religious economy theory. In its strongest form, secularization theory argues that religion erodes as modernization proceeds (

Berger 1967;

Wilson 1982), though the metrics of modernization vary by secularization theorist (

Bruce 1999;

Norris and Inglehart 2004). Religious economy theory, on the other hand, contends that religious deregulation leads to increased religious pluralism and, in turn, higher levels of religious activity (

Stark and Iannaccone 1994;

Stark and Finke 2000). For reasons to be discussed, however, neither of these theories can make sense of the religious change with which this work is concerned. Anomalous cases do not create cause for abandonment of the theories that fail to explain them, but rather present an opportunity for theoretical complication and improvement. With a focus on symbolic threat dynamics, I here provide a new theoretical approach to understanding religious change.

Theories of religious change have not adequately considered the impact cultural threats have on identity formation and, likewise, group threat theories have paid scant attention to processes of religious change. In this article, I contribute to both literatures by integrating the effects of cultural threat into a theoretical discussion of religious change. Central to this integration is the understanding that salient symbolic traits of a group’s identity (which could fall into religious, racial, cultural, and linguistic categories) emerge in the face of a cultural threat. While the potential utility of symbolic threat has been considered in discussions of religious identification (e.g.,

Stark and Finke 2000;

Bebbington 2012), this factor has yet to be systematically incorporated into any theory of religious change. Furthermore, speculation concerning the connection between symbolic threat and religious change has mostly revolved around situations of religious revival, whereas this article uses this dynamic to explain a case of religious decline.

This work will use the contextual particularities of East and West Germany to inform the more general discussion of how threat relates to processes of identity formation. In this article, secularity will be understood as a central facet of the East German character. Throughout the reign of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), pushing a secular worldview upon East German consciousness was an important objective for the communist regime (

Stolz et al. 2020). Mediated by the deeply atheistic history of East Germany, secularization is here presented as a reaction of eastern identification that repeatedly emerges among East Germans who perceive cultural threats from outsider groups. The case of East Germany demands theoretical complication of this kind, for it has demonstrated exceptional patterns of religious decline.

The secularization of East Germany shortly after German reunification presents an empirical “puzzle” to sociologists of religion, for neither secularization theory nor religious economy theory can explain this period of religious change. With the fall of the Soviet Union and consequent deregulation of religion, a religious revival was observed among the vast majority of Eastern Bloc nations in the 1990s (see

Table 1). These spikes in religiosity that came along with religious deregulation clearly align with the claims of religious economy theory. Anomalous to this pattern, however, East Germany became increasingly secular in the years following reunification (

Pollack 2002; see also

Table 1), and has since become the least religious society in the world (

Froese and Pfaff 2005;

Smith 2012).

1 This curious religious decline is also no triumph for proponents of secularization theory, for the steep drops in religiosity within the mere six years presented in

Table 1 certainly do not correspond to the extent of modernization that took place within this timeframe.

2 As others have noted (

Froese and Pfaff 2005), the claims of secularization theory are also incongruous with the religious revival of other Eastern Bloc nations. Furthermore, secularization theory falls short of an explanation for the combination of differences between East and West Germany, namely that the latter is more religious (

Smith 2012;

Müller et al. 2016) and modernized (

Uhlig 2008) than the former.

In this article, I find the connection between symbolic threat and identity formation to be a useful mechanism to make sense of religious change. Central facets of the GDR identity, such as socialist voting (

Grix 2000), eastern consumerism (

Blum 2000), and secularity (

Froese and Pfaff 2001), emerged at a time when the eastern identity was perceived to be threatened by the nature of Germany’s reunification process. I connect this mechanism of eastern identification in the 1990s to a more recent symbolic threat, namely the growing fear of Germany’s migrant population. Although secularity is commonly associated with left-wing ideology, this article finds a dramatic reduction in religious activity among the East German right-wing, which in recent years, has become virtually identical to the left-wing by all tested metrics of religiosity. This article explores the role that fear of foreign domination may play in this reactive formation of the secular identity. Previous research has not connected this process of reactive identification to the recent secularization of the political right. To my knowledge, this is the first article to find a period of right-wing secularization in any context.

3To make sense of these changes, I first describe the mechanisms of group threat theory upon which my core argument relies. Next, I discuss the sharp religious decline during the reign of the GDR in light of the various forms of religious persecution that took place throughout the regime’s existence. From here, I document religious changes in formerly Soviet-occupied countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and present East Germany’s exceptionalism (i.e., its continued secularization) as a reaction to the cultural threat of western-led reunification. In the following section, I connect this same mechanism of reactive secular identification to the more recent threat of migrant arrivals. To empirically illustrate these dynamics, I test the ways in which political ideology and xenophobia relate to religiosity in East and West Germany. I find recent spikes in secular identification among the right-wing, as well as a strong relationship between secularity and fear of foreign domination. Finally, I discuss the potential extension of this social logic to other contexts, and emphasize the ways in which cultural vulnerability and, in turn, reactivity could pervade country and subject.

2. Reactive Identification

The connection between symbolic threat dynamics and religious change relies on the contention that symbolic threat can lead to increases in salient collective characteristics among culturally threatened groups. The logic of this theoretical claim is similar to that of competitive threat theory, which contends that threat contributes to the development of prejudice and in-group identification (

Blumer 1958;

Tajfel 1982). Competitive threat theories are primarily concerned with conflict over scarce resources between competing groups, as well as the relative size of the threatening “outgroup” (

Blalock 1967;

Quillan 1996). In addition to materialist matters (e.g., unemployment, economic competition, etc.), a great deal of research has also been sensitive to the ways in which boundary making and collective identification connect to ideational dimensions, such as race, religion, nationhood, language, and culture (

Wimmer 2008;

Sarjoon et al. 2016;

Lubbers and Coenders 2017;

Gorman and Seguin 2018;

Lam et al. 2023).

The concept of symbolic threat by itself is thus hardly a novel one. It is the connection between threat dynamics and theories of religious change that has been largely overlooked, however. Past research has focused on the relationship between symbolic threat and identity formation (e.g.,

Glaeser 2000;

Gorman and Seguin 2018), though this article analyzes these dynamics over time and integrates them into a discussion of religious change. Central to the linking of these seemingly disparate theoretical domains is the impact that the “outsider” has on the formation of identity among members of the threatened group.

When the dominant group senses that the subordinate group has improved its economic or symbolic position (and thus, challenges the position of the dominant group), they react defensively and develop feelings of prejudice (

Blumer 1958;

Quillan 1995; see also

Stipisic 2022). When this perception is formed, they view members of the threatening group not on the basis of their respective individualities, but rather on the abstract image of their group membership. In turn, members of the dominant group develop a collective perception of themselves in relation to the subordinate group, for it is the relative position of the latter that defines the boundaries of the former. Threat thus plays a role in the process of identity formation, for such formation is often done in light of the encroachment of the other.

Glaeser (

2000, p. 399), for example, likens the construction of identity to “a ping-pong of identifications between self and other.” This reactive process of identity formation among members of the threatened group necessarily depends upon their relationship with the otherized group. Reactions to threat vary with context, for such reactivity depends upon the overarching historical and cultural particularities through which it is mediated.

In this article, secularity will be understood as an East German in-group attribute that emerges in reaction to perceived ideational threat. I propose that a focus on symbolic threat dynamics can help make sense of East Germany’s exceptional patterns of religious decline. By analyzing this pattern over time, I here demonstrate how secularization repeatedly surfaces among East Germans, who feel a sense of cultural “infiltration” from outsider groups. To understand the nature of this reactive identification, it is crucial to be cognizant of the historical and cultural idiosyncrasies at hand.

3. Religion, Materialism, and the GDR

From its founding until its collapse, the GDR was committed to promoting scientific materialism through atheist proselytizing. When the GDR was founded in 1949, over 90 percent of the population belonged to the church. By the time of its dissolution in 1990, this figure had dropped to just under 30 percent (

Institut für Demoskopie 1990;

Pollack 2002). In an effort to popularize the socialist personality, the GDR attempted to expedite the “withering away” of religion through several means (e.g., citizens with open religious convictions faced occupational and educational discrimination, pastors and congregations were often harassed by state officials, historic churches were demolished, religious organizations and charities were eradicated, religious instruction was removed from classrooms, etc.). Under the GDR, such persecution was justified by the belief that religion was inherently inimical to the advancement of socialist objectives and wholly incompatible with the

Wissenschaftliche Weltanschauung (scientific worldview), a term which was printed on nearly every GDR document.

The GDR’s framing of an ideological juxtaposition between science and religion is, perhaps, best exemplified by the

Jugendweihe (ceremony of youth). The

Jugendweihe is a ceremony that originated in the mid-nineteenth-century, was abolished in 1950, and then reintroduced by the GDR in 1954 (

Besier 1999). Although it has taken on several meanings since its inception, the

Jugendweihe was an atheistic and socialist ceremony which 14-year-olds participated in throughout the reign of the GDR. Participants swore an oath of loyalty to the socialist State and science as opposed to regressive, irrational modes of thought. Preparatory classes for the

Jugendweihe involved readings that emphasized pride in GDR culture, and presented scientific explanations as superior to religious teaching. Participation in the ceremony was treated as a prerequisite for educational opportunities and coveted employment.

It is thus no surprise that

Jugendweihe participation skyrocketed shortly after its reintroduction (see

Figure 1). In 1955, only 17.7 percent of adolescents participated, though just five years later, this figure shot up to 87.8 percent. By 1980, 97.5 percent of GDR youth took part in the ceremony (

Droit 2014). The

Jugendweihe was meticulously organized to be in competition with religious ritual, as it took place on Sunday mornings in spring, and its structure mirrored that of religious confirmation (e.g., the ritual included music, lectures of morality, etc.). It appears that the GDR was successful in their efforts of conversion, as the sharp rise in

Jugendweihe participation was accompanied by an equally staggering decline in religious confirmations. As can be seen in

Figure 1, participation in religious confirmation decreased by 45.7 percent between 1955 and 1960.

The Church, of course, did not take kindly to the reintroduction of the

Jugendweihe nor any of the State’s attempts to eliminate the religious imagination. Consequently, Church-State relations became particularly fractious in the 1950s and 60s. The State harassed pastors and congregations, published defamatory articles on religious leaders, supervised the Church’s regional papers (which required State approval prior to publication), demolished historic churches, and significantly reduced church subsidies (

Ramet 1992). This is not to suggest that the extremity of Church-State tension did not vary throughout the reign of the GDR. With the 1978 Church in Socialism agreement, for example, the Union of Protestant Churches committed to political indifference in exchange for greater Church autonomy. This degree of independence granted dissidents a space for non-compliance, evidenced by the formation of about 100 independent peace groups (nearly all of which were sheltered by a church) (

Pfaff 2001).

Open discussion and dissident organization, however, were nothing but vexations for the GDR, which banned church periodicals and physically interfered with protests. This dissidence was, perhaps, most pronounced in the Saxon city of Leipzig. The Monday demonstrations in Leipzig were arguably the most influential (certainly the most well-known) of protests that occurred during the Peaceful Revolution of 1989. The Nikolaikirche, a twelfth-century church in Leipzig, provided a space for dissidents to escape the reluctant conformity demanded of them in non-autonomous spaces. It is also worth noting that the Monday demonstrations, at which hundreds of thousands of protestors famously chanted Wir sind das Volk (we are the people), took place right after evening peace prayers.

As is well-known, the fall of the GDR shortly followed the Peaceful Revolution of 1989. The new elections in March of 1990 resulted in a coalition government led by Lothar de Maiziere and, in October of the same year, the country was reunified. Fourteen pastors served as members of the transitional parliament; and four as members of de Maiziere’s cabinet. Several Holy Days became recognized as State holidays, and nearly all State pressures against the Church were removed (

Ramet 1992). With democratization and reunification came a host of societal and political changes, including the deregulation of religion.

4. Perceived Threat of West German Domination

Proponents of religious economy theory (

Stark and Iannaccone 1994;

Stark and Finke 2000) may expect this distancing from GDR culture to be reflected in the change of religious demographics. However, the continued secularization of East Germany in the years following religious deregulation are not cooperative with this postulate. Proponents of secularization theory (

Bruce 1999;

Norris and Inglehart 2004) can explain East Germany no better, for the dramatic religious decline between 1990 and 1996 does not correspond to the extent to which East Germany modernized within this short six-year timeframe. Furthermore, the contentions of secularization theory are incongruous with the religious revival of the other post-communist countries during this time. As others have observed (

Froese and Pfaff 2005), East Germany is clearly an anomalous case, for unlike other Eastern Bloc nations, it cannot be explained by the prevailing theoretical paradigms of religious change. To better understand this anomaly and, in turn, improve upon these theories, focus must be directed toward the peculiarities of East German conditions.

While citizens of the other Soviet-occupied countries retained their national identities after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the GDR was subsumed under their western counterpart’s Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). East Germans were no longer citizens of their former GDR, though a sense of two national identities would persist. Although over 90 percent of East Germans were in favor of reunification (

Howard 1995), the unification process was abrupt, western-led, and perceived as a “colonization” of East German society. Unlike West Germans, East Germans were hurled into a new situation in which they had to learn and adapt to their new society and national identity. A division within technical unity was palpable throughout all of Germany, particularly in the eastern regions. In a 1993 poll, for example, only 6 percent of East Germans and 14 percent of West Germans viewed East-West relations in a positive light, with 68 percent of East Germans blaming the West for said polarization. By 1997, 67 percent of East Germans claimed that they feel more East German than German (

Hogwood 2000).

East Germans were symbolically ostracized, as they were (and, to an extent, still are) often the recipients of cultural teasing (e.g., attacks made against their accents, level of intelligence, etc.). In his ethnographic work on eastern and western Berlin police officers,

Glaeser (

2000) observes how West Germans would rarely view East Germans as equals, often characterizing eastern society as an inferior state from which the West had nothing to learn. From the West German perspective, East-West relations were “something like that between adults and children, where adults do not consult with their children on serious matters until they have grown up to become adults themselves” (

Glaeser 2000, p. 329).

As for materialist concerns, it became more difficult for East Germans to find employment, as many of their formerly legitimate qualifications were deemed obsolete with reunification. This was a particularly troubling development for East Germany, which had an unemployment rate that nearly doubled that of West Germany (

Grix 2000). In 1990, over 70 percent of East Germans had a positive opinion about the economy, though this percentage shrank to slightly below 20 percent by 1996 (

Grix 2000). In 1995, nearly three-quarters of East Germans agreed that former GDR citizens are treated like second-class citizens in unified Germany (

Howard 1995). This dissatisfaction became so prevalent that nearly half of East Germans in 1996 even saw GDR times as “good times” where “everyone was equal and we were all in work” (

Hogwood 2000, p. 59).

In reaction to the sudden, western-led changes of the 1990s, the phenomena known as

Ostalgie (the term’s compounds being

Ost (east) and

Nostalgie (nostalgia)) and

Trotzidentität (identity of contrariness) surfaced in political and cultural ways. Between 1990 and 1998, for example, sympathy toward socialist views more than tripled among East Germans (

Froese and Pfaff 2005). The Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), a descendant party of the GDR, benefited from this socialist sympathy, as the vast majority of their support came from East German states (

Statistisches Bundesamt 2017a). Eastern forms of defensiveness were not limited to economic assessments and protest voting, but also operated in symbolic domains. For example, research on consumer trends in the former GDR show that old products of eastern origin became increasingly popular in the mid-to-late 1990s (

Blum 2000). This was not a mere fad, as 45 percent of East Germans claimed to deliberately purchase eastern products as often as possible (

Howard 1995). A similar form of this eastern contrariness can be observed in the post-reunification revival of the

Jugendweihe. With reunification, the ceremony was no longer required for certain employment and educational opportunities.

Jugendweihe participation thus dipped immediately after the fall of the GDR, though it surprisingly rose after a few years of experience in unified Germany, with over 60 percent of East Germans voluntarily participating in the ceremony by 1999 (

Saunders 2002).

With these indications in mind, it appears as if it was the collapse of the GDR that led to its symbolic return. Politically and culturally, a reactive connection with the GDR identity materialized throughout East Germany shortly after reunification. Identity formation depends upon the nature of the threat imposed by the otherized group (

Blumer 1958;

Glaeser 2000;

Wimmer 2008). In reaction to the threat of western domination of the East, central facets of the eastern identity, such as socialist sympathy, eastern consumerism, and

Jugendweihe participation were expressed in a voluntary manner. Among such reactions of eastern contrariness was the secular identity, as indicated by the sharp decreases in church attendance, belief in God, and self-assessment of religiosity in the years following reunification (recall

Table 1). Relatedly,

Pollack (

2002) finds that East Germans’ trust in the Church declined rapidly in the 1990s, and suggests that this decline could be attributed to the common perception of the Church as either being or becoming a western institution. Literature in social psychology indicates that, in reaction to threat, groups seek a sense of social order (

Kay et al. 2009); a process which can involve identifying with salient collective traits. As demonstrated by the examples here provided, this reach for restoring normalcy and tradition could be observed culturally, politically, and religiously in the years following the collapse of the GDR. It is in this light of

Ostalgie and

Trotzidentität which the secularization of the 1990s will be understood.

4 5. Perceived Threat of Migrant Arrivals

More recently, a new cultural interaction has led to the materialization of a similar, though distinct form of eastern reactivity. Sharp increases in Germany’s migrant population have brought immigration and asylum seeking to the center of political discussion in Germany. Between Chancellor Angela Merkel’s 2005 victory and the 2017 federal election, 14,534,644 immigrants and asylum seekers have arrived to Germany, resulting in a net migration of 3,887,599. In 2015 alone, 2,136,954 immigrants and refugees (net migration of 1,139,402) arrived to the country (

Statistisches Bundesamt 2019a). Out of all first-time asylum applicants in European Union (EU) Member States, 61 percent registered in Germany in the first quarter of 2016 (

Juran and Broer 2017). Over 20 million residents; that being approximately one-fourth of the German population, reported having a migrant background in 2018 (

Statistisches Bundesamt 2019b).

Similar to the speed and extent of the country’s demographic changes, citizen opinion on (particularly Muslim) immigration has dramatically changed. In 2016, 41.4 percent of German respondents rather or entirely agreed that entry of Muslims into Germany should be prohibited; a percentage which has nearly doubled since the 2011 edition of the survey was conducted. Within the same timeframe, 50 percent of Germans reported that they feel like a foreigner in their own country; a figure that has increased by 19.8 percent in just 5 years (

Decker et al. 2016). Out of all religious groups, Germans view Muslims the most negatively, with anti-Muslim sentiment most prevalent in the eastern regions of the country (

Pickel and Yendell 2014;

Pickel 2018). The majority of East Germans perceive Islam as a threat to Germany, and just over 10 percent agree that Islam is compatible with German society (

Pickel 2018). According to all measurements, anti-Islamic views are on the rise in Germany, and are particularly strong in the East.

Perhaps the most notable manifestation of this reaction to migrant arrivals is the emergence of the

Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) or “Alternative for Germany”, a far-right populist party founded in 2013. Some of the section headings in the party’s manifesto include “German as Predominant Culture Instead of Multiculturalism”, “Islam and Its Tense Relationship with Our Value System”, “Islam Does Not Belong to Germany”, “Tolerate Criticism of Islam”, “No Public Body Status for Islamic Organizations”, and “No Full-Body Veiling in Public Spaces” (

AfD 2017). Consistent with the manifesto’s content, past research has found limiting the arrival of Muslim immigrants to be the chief concern of AfD supporters (

Stier et al. 2017;

Pickel 2018). Ideological prioritizing of this kind is also characteristic of the Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident (PEGIDA), a movement which, like the AfD, advocates for the limiting of Muslim influence in Germany. Supporters of PEGIDA reference immigration control, nationalism, and Islam among their top reasons for joining the movement, with over 80 percent of them fearing the loss of their national identity (

Daphi et al. 2015).

This nativism has been no more palpable than in the former GDR states, particularly in the state of Saxony. Saxony has long been a symbol of pride in German heritage and, as has been touched upon, was home to some of the most notable demonstrations of the Peaceful Revolution of 1989. In recent years, however,

Wir sind das Volk has taken on a jingoist meaning, as it is now often found on the signs held at anti-immigrant demonstrations. Within just six months after their founding, PEGIDA held 252 rallies, with protestors totaling to approximately 240,000. Of these some 240,000 protestors, 80 percent of them protested in Saxony (

Virchow 2016). Like PEGIDA support, AfD support is primarily concentrated in the eastern regions of the country (

Statistisches Bundesamt 2017b). Between the 2013 and 2017 federal elections, all of the highest upsurges in electoral support for the AfD occurred in East German states: Saxony (20.2% increase), Thuringia (16.5% increase), Saxony-Anhalt (15.4% increase), Brandenburg (14.2% increase), and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (13.0% increase) (

Lees 2018). While the AfD/PEGIDA message has not gained much traction in the western regions of Germany, it has considerably resonated with East German sensibilities. Notably, church commitment is negatively correlated with AfD support (

Huber and Yendell 2019) and non-religious voters are substantially more likely to vote for the AfD than mainstream political parties, such as the Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party (

Arzheimer and Berning 2019).

5 Secularization: A Recurring Reaction to Symbolic Threat

Among those concerned with the preservation of such symbolic dimensions of their identity, we may again be witnessing a reaction of eastern identification in the face of cultural threat. Not unlike the eastern secularity that surfaced shortly after the western-led process of reunification, a considerable number of East Germans may now be responding to what they perceive as the newest form of cultural “infiltration”, namely the recent spike in migrant arrivals. This more recent cultural contrariness, I posit, may be associated with the intensification of the eastern personality. When a group perceives a threat, said group will pursue order and normalcy through a process of reactive identification. Many among the right-wing perceive the arrival of immigrants as a threat to their identity (

Stier et al. 2017;

Yendell and Pickel 2019) and thus, it may be the case that yet another culturally defensive reaction (mediated by the overarching secular history of East Germany) of secularity is emerging. Although other researchers have noted the religious decline of the 1990s (

Froese and Pfaff 2005), the literature has yet to explore the more recent secularization of the political right. Both reactive secularities, I contend, revolve around the mechanism of defending the eastern identity in the face of cultural threat.

Related research has surfaced in recent years, though it would be an overstatement to claim that the literature has achieved scholarly consensus.

Inglehart and Norris (

2016) find a positive association between religiosity and right-wing populist support, others have found religiosity to have little effect on radical right voting (

Arzheimer and Carter 2009;

Montgomery and Winter 2015), while other research claims that the relationship is further complicated when religious orthodoxy is brought into the scope of analysis (

Immerzeel et al. 2013). Although the relationship between

secularity and right-wing ideology has received some attention, the change in this relationship (i.e.,

secularization) over time has been repeatedly overlooked. Thus, the current theoretical backgrounds are severely limited, leaving changes in the given political landscape(s) unconsidered. To advance toward more lucid determinations, future inquiry should be cognizant of the potentially catalytic contextual factors pertinent to their research, how these factors have changed over time, and in turn, affected the given relationship(s) under examination.

Right-wing populist support is a telling phenomenon which provides indications of social logics relevant to the present discussion, though it does not entirely encompass the symbolic variant of group threat with which this work is concerned. The cultural defensiveness that materializes with the detection of a cultural threat, is not only a political, but also an

emotional reaction which may operate within, but also outside of AfD voting and right-wing ideology in general. This reactive emotionality and identification have more to do with pure antipathy toward and fear of the otherized group than it does with party support and/or policy position. The conceptual demarcation here is in accordance with a characterization from

Quillan (

1995, p. 587), who notes that “prejudice is characterized by irrationality (a faulty generalization) and emotional evaluation (antipathy).” Thus, in addition to considering religious change among the right-wing, this work taps into this emotionality by examining fear of foreign domination as it relates to the secular identity.

In the years following increases in migrant arrivals, xenophobic attitudes are on the rise in Germany (

Decker et al. 2016), and are particularly prevalent among East Germans (

Yendell and Pickel 2019), as well as right-wing groups (

Daphi et al. 2015;

Stier et al. 2017). Similar to the

Ostalgie of the 1990s, it is possible that the more recent perceived threat of migrant arrivals has led to a defensive reaction of secular identification among the right-wing and culturally vulnerable in the East. Assuming this is indeed the case, I expect to find a significant religious decline among the East German right-wing between 1999 and 2017. If secularity is a part of the eastern reactivity I have here described, then a positive relationship between fear of foreign domination and the secular identity will be found in the context of East Germany.

6. Methods

To test these expectations, I rely on data from EVS and ALLBUS. Notably, I am unable to fully establish construct validity with the available data, though this analysis still provides empirical indications that align with my theoretical contentions. I use the 1999 and 2017 datasets from EVS to examine religious change by political ideology.

6 The association between xenophobia and religiosity is measured with the ALLBUS 2018 dataset, as it contains a metric that most precisely captures the fear of foreign domination with which this work is concerned.

6.1. Dependent Variables

Religiosity is the dependent variable in the current study. I measure religiosity with binary indicators of church attendance, belief in God, and self-assessment of religiosity. Each dimension of religiosity is analyzed separately to capture their respective nuances (e.g., religious behavior, belief system, self-identification, etc.). When using the EVS datasets, respondents are coded as attending church if they report attending “once a month” or more frequently. When asked if they believe in God, respondents are given “yes” or “no” as response options. For self-assessed religiosity, respondents are coded as religious if they consider themselves to be “a religious person”, as opposed to responses that earn an irreligious categorization: “not a religious person” and “a convinced atheist.” When using the ALLBUS dataset, respondents are considered to attend church if they report attending “1 to 3 times a month” or more. The following responses are categorized as believing in God: “I believe in God now and I always have” or “I believe in God now, but I didn’t used to.” For self-assessed religiosity, respondents are considered religious if they describe themselves as “extremely religious”, “very religious”, or “somewhat religious”.

7 6.2. Independent Variables

Political ideology and fear of foreign domination are the focal independent variables. “Left-wing”, “moderate”, and “right-wing” are the three categories representing political ideology. In each dataset, this categorization is determined by self-identification on a scale ranging from 1 to 10, with 1 representing the farthest left; and 10 the farthest right. Respondents who place themselves between 1 and 4 are coded as politically left-wing; 5 as political centrists, and between 6 and 10 as politically right-wing.

8 Respondents are considered to exhibit fear of foreign domination if they “tend to” or “completely” agree that “because of its many resident foreigners, Germany is dominated by foreign influences to a dangerous degree”.

9 Fear of foreign domination is coded as a binary variable.

6.3. Control Variables

I control for age (measured continuously), sex (1 = male), level of education (using each dataset’s categorizations of “lower”, “medium”, and “higher”, which correspond to lower than upper secondary education, upper secondary education, and higher education, respectively), and monthly income (using EVS’s categorizations of “lower”, “medium”, and “higher”, which in 1999, correspond to the categories “under 3000 Marks”, “3000–4999 Marks”, and “over 4999 Marks”, respectively. In EVS 2017, the monthly income brackets I control for are the following: 2200 Euro or less, 2201–4250 Euro, and over 4250 Euro). ALLBUS 2018 and EVS 2017 use slightly different income brackets. When using the ALLBUS dataset, I divide income level into the following three categories: under 2250 Euro a month, 2250–3999 Euro a month, and over 3999 Euro a month.

6.4. Analytic Strategy

In the following analyses, East and West Germany are analyzed separately.

10 This comparison assists in conjecturing as to whether the expected relationships are connected to the overarching secular history of the GDR, or alternatively, if they simply exist throughout all of Germany. Furthermore, both secularity and anti-immigrant attitudes are more prevalent in East Germany than they are in West Germany. Thus, the two regions must be divided in this analysis to address any potential issues pertaining to a regional confounder. In West Germany, I do not expect to find a period of right-wing secularization, nor a strong relationship between secularity and fear of foreign domination, for western forms of cultural reactivity are not mediated by an atheistic history. I thus suspect these findings to be particular to the eastern regions of the country.

Using the EVS datasets, I report the percent change in religiosity among each political ideology category between 1999 and 2017. To test whether the association between religiosity and political ideology changes over time, I use multivariate models that account for controls, append the EVS 1999 and 2017 datasets, and interact time with political ideology. Specifically, I estimate logistic regression models to predict religiosity and interact a binary indicator of survey year with the categorical measure of political ideology. Following the guidance of

Ai and Norton (

2003), I do not interpret the coefficient of the interaction term, but instead assess the interaction using predicted probabilities and marginal effects. The relevant marginal effects, calculated as the difference in the predicted probability of religiosity between the left- and right-wing within each year (and differences across years), are presented.

Negative views of immigrants are, of course, not entirely subsumed under the political right. To provide further indicative support of my theoretical claims, it is thus important to examine not only right-wing ideology, but more particularly, fear of foreign domination in order to understand the cultural reactivity in the East. Using the ALLBUS 2018 dataset, I estimate additional multivariate logistic regression models (in both the East and West) to predict religiosity, with fear of foreign domination as the focal independent variable. The estimates are presented as odds ratios. I then test whether the association between fear of foreign domination and religiosity are significantly different by region. To do so, I interact a binary indicator of region (i.e., East or West Germany) with fear of foreign domination and assess the interaction using predicted probabilities and marginal effects (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A).

7. Results

Table 2 shows that the right-wing in East Germany have demonstrated sharp drops in religiosity by all of the tested metrics. The same degree of religious change cannot be observed among the politically moderate and left-wing, which demonstrate slight decreases and increases in religiosity, respectively. With this period of religious change, the right-wing has become as secular as moderate and left-wing respondents. In fact, the right-wing reports the lowest rates of church attendance among the three ideological categories. This pattern appears to only pertain to East Germany, for secularization is not particular to the right-wing in West Germany. To be clear, it is not the case that East Germany, including respondents of all ideologies, has dramatically secularized between 1999 and 2017, as religiosity rates have remained relatively static within this timeframe (data available upon request). Rather, the period of secularization shown is particular to the East German right-wing, who are more likely to exhibit fear of foreign domination than their left-wing and moderate counterparts (

Yendell and Pickel 2019).

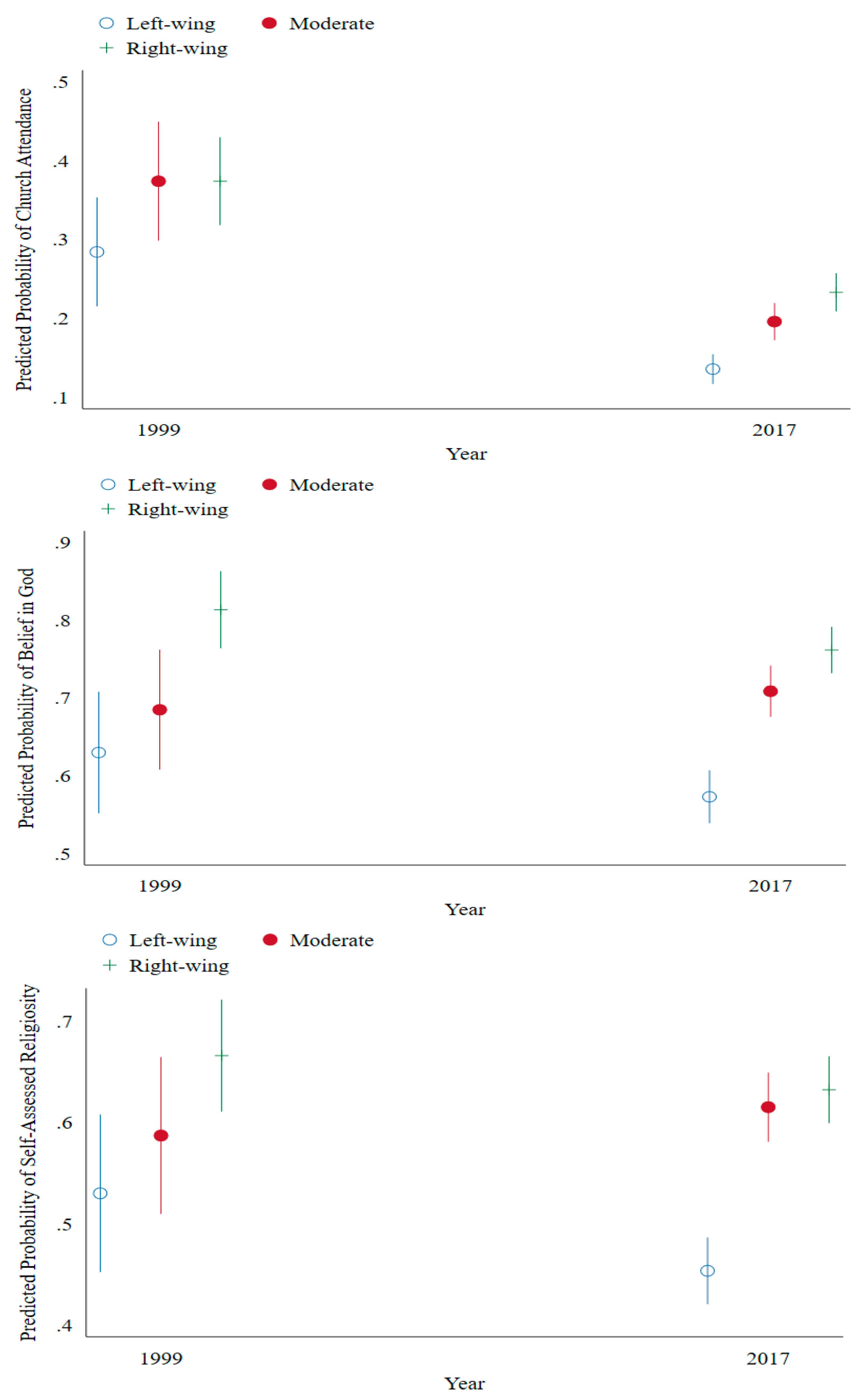

In

Figure 2, a significant reduction in religious activity among right-wing respondents can be observed between 1999 and 2017 in East Germany. In 1999, right-wing respondents in East Germany are, by all metrics, more likely to be religious than are left-wing respondents (

p < 0.001). These relationships are stronger and more significant in the East than they are in the West (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Given the atheist proselytization that took place during the reign of the GDR, a perceived incompatibility between religious thought and left-wing ideology was likely not uncommon among East Germans in the years following reunification. This perception of mutual-exclusivity was, perhaps, not as pronounced in the historically less regulated West. In 2017 East Germany, however, the political right has become virtually identical to the political left by every measure of religiosity (see

Figure 2). Indeed, political ideology is no longer a predictor of religiosity in the way that it was in 1999. The results indicate that this phenomenon is particular to the East, as the religious differences between left- and right-wing respondents remain significant in West Germany (

p < 0.001) (see

Figure 3 and

Table 3). In East Germany, I find a significant reduction in the religious disparity between the left- and right-wing in terms of church attendance (

p < 0.001), belief in God (

p < 0.05), and self-assessment of religiosity (

p < 0.01). By no metric of religiosity are these changes significant in West Germany. In the years following increases in migrant arrivals, the secular identity has become more common among the political right in East Germany. This phenomenon is particular to the right-wing, as respondents of the other political orientations do not come close to mirroring this degree of secularization.

In accordance with EVS data, data from ALLBUS show that political ideology does not predict religiosity in East Germany. Unlike data from EVS, however,

Table 4 shows that the relationship between political ideology and religiosity is insignificant in West Germany. While there are no longer significant religious differences across the political aisle, fear of foreign domination holds a strong inverse relationship with church attendance (

p < 0.001), belief in God (

p < 0.01), and self-assessment of religiosity (

p < 0.01) in East Germany (see

Table 4). It is clear that this relationship is more palpable in the East, as the associations do not achieve statistical significance and vary in direction in the West. These results demonstrate that it is not a confounding right-wing ideology in general, but more specifically a fear of foreign domination that predicts the secular identity in East Germany.

While it is a cultural rather than socioeconomic threat with which this work is concerned, it is important not to overlook the role of variables related to deprivation. East Germany is not as economically stable as West Germany and thus, one could reasonably suspect forms of cultural identification in the East to be linked to economic intimidation. As for the reactive secularity under examination, however, the data do not reflect this anticipation. In relation to the tested metrics of religiosity, level of education and income are inconsistent in direction and do not once achieve statistical significance in East Germany. There is no evidence to suggest that socio-economic variables link to the reactive process of secular identification in this analysis. This finding may suggest that this phenomenon is more likely a matter of cultural competition, rather than of economic worry.

8. Discussion

Although the prevailing theories of religious change cannot explain the case of East Germany, I have here suggested that a focus on symbolic group threat may help make sense of this empirical puzzle. The impact cultural threat can have on identity formation has been largely ignored in discussions of religious change. While symbolic threat theorists have been cognizant of the relationship between cultural threat and identity formation, my article examines these dynamics over time and integrates them into a discussion of religious change. When a group perceives a cultural threat, increases in central characteristics of the identity of said group (which may be relevant to a wide array of sociological subfields) can be observed.

This article has outlined how, against the prevailing theoretical expectations, East Germany became increasingly secular after the process of reunification and consequent deregulation of religion. To understand this exceptionalism, I theorize that this period of secularization is connected to the Ostalgie/Trotzidentität phenomena which surfaced in reaction to the threat of West German domination. I then contend that a similar mechanism of reactive identification has recently surfaced on the right in the face of a new cultural threat, namely the fear of Germany’s migrant population. Between 1999 and 2017, the data show that sharp drops in religiosity have occurred among the political right in East Germany. This is the first article to produce a finding on right-wing secularization in any context.

These decreases are particular to the East German right-wing, as they cannot be observed among left-wing and moderate respondents. Nor is this pattern found in the context of West Germany. Differences between East and West Germany, I argue, could be understood in light of their respective overarching religious histories. Secularity, for example, was inextricable to the character of the GDR in a way that it was not to that of the Bonn Republic (i.e., the former West Germany). This article also demonstrates that secularity and fear of foreign domination are closely related in the East, whereas the associations are not at all noteworthy in the West. It appears that the eastern trait of secularity repeatedly emerges among those who perceive cultural threats, such as reunification in the 1990s and liberal immigration law in recent years.

Given the cultural and economic differences between East and West Germany, both materialist and symbolic threats are worthy of consideration. Within the process of secular contrariness, however, the results provide little reason to suspect that this reactivity is in connection with materialist concern. Neither education nor income play a role in the reactive secularity under examination. This finding may indicate that it is not economic vulnerability, but rather fear of cultural denigration that plays a role in the materialization of the reactive identity. Further study on this matter is warranted, however, as previous findings concerning the associations between conditional variables and forms of cultural reactivity (e.g., anti-immigrant behavior, far-right violence, right-wing populist voting, etc.) have been mixed (

Koopmans and Olzak 2004;

Lengfeld 2017;

Patana 2020).

Although it is the intricacies of only one country that I have here examined, I encourage other researchers not to overlook the importance of thorough historical, political, and cultural investigation of a specific context. The nature of the reactive identity will depend upon the contextual factors (e.g., salient collective characteristics, religious history, etc.) in which it is engulfed. In-depth analyses of certain conditions, particularly when they deviate from prevailing theory and expectation, can inform our theoretical development by identifying catalytic factors, which would go undetected with broader (though, more cursory) analyses. It is important for detailed examination of this kind to be in conversation with broader comparative approaches, for such collaboration can help inform future criteria used in the process of selecting which variables to examine. As

Voas and Chaves (

2016: 1549) note, religious differences between countries “are a matter of history and culture, and explaining them always requires a combination of the general and the particular”.

Territorial shifts, immigration policy, and religiosity are certainly not the only factors that could be tested within the theoretical framework I provide. When a certain population perceives a threat to their identity (and that threat could, though need not be foreign influence), a reaction of collective identification (the form of which is mediated by the cultural characteristics of the given national history) may emerge. Religious change (and likely other changes of sociological interest) among the respective population could be understood in light of their relation to, and the unraveling of, the cultural and historical idiosyncrasies of the given context. Future research could identify one of the many contexts in which a nativist or culturally defensive population exists, select an aspect that is central to this population’s national character, and observe how this trait changes before and after exposure to the perceived threat. The variables selected for analysis should vary by context, for it is a mechanistic focus on cultural vulnerability and, in turn, reactivity, which could provide potential avenues for replication.

The emphasis on contextual particularity is especially crucial when attempting to explain anomalous cases. In the case of East Germany, the prevailing theoretical paradigms of religious change fall short of an explanation and thus, an opportunity for theoretical improvement presents itself. Drawing on the peculiarities of East Germany, I have found a focus on symbolic threat and subsequent identity formation to be a useful point of departure. Little work has been done to understand the historical and cultural dynamics of secularization (for more discussion on this limitation, see

Gorski 2000). To adequately elucidate the dynamics of cultural identification, researchers must be sensitive to the complexities of the historical and political conditions relevant to their analyses. Historicization of this kind can assist in analyzing important changes in light of culturally vulnerable reactions which are, by necessity, filtered by the overarching national character of the given context.