Abstract

In 1967, Robert Bellah argued that America’s “founding myth”, what he called American civil religion, helps bind American society together by providing its citizens with a sense of origin, direction, and meaning. For evidence, Bellah primarily turned to the inaugural speeches of American presidents. This paper draws on semantic network analysis to empirically examine the inaugural addresses of Presidents Trump and Biden, looking for evidence of what some would consider aspects of American civil religion. As some believe American civil religion to be no more than a thinly veiled form of nationalism, it also considers the importance of words associated with nationalism. It finds that both Trump and Biden employed the language of nationalism and American civil religion in their respective addresses, and while it found no differences in their use of nationalist discourse, it did find that American civil religion figures more prominently in Biden’s address than in Trump’s.

1. Introduction

In 1967, Robert Bellah published an article that he later remarked no one would let him forget (Bellah and Hammond 1980, p. 3). In it, he argues that America’s “founding myth”, what he calls American civil religion, helps bind American society together by providing its citizens with “a set of beliefs, symbols, and rituals” that connect them to the divine order of things and gives them a sense of origin, direction, and meaning (Bellah 1967, p. 4). According to Bellah, this civil religion holds that God has chosen the United States to be a city on a hill, a light to the nations, and a witness to God’s (and America’s) greatness (Bellah 1967, 1975). This chosenness, however, comes with conditions. It is contingent on Americans, individually and collectively, carrying “out God’s will on earth”. It is a covenant between God and the U.S.; God will keep God’s promises as long as Americans uphold their end of the bargain (Gorski 2017a). Not only do Americans need to act appropriately in their private lives, but they are also expected to protect the weak, check the powerful, and put the interests of others ahead of their own. In short, American civil religion combines private piety with prophetic witness. Bellah appears more attracted to the civil religion’s prophetic aspect and, in particular, how “dissenters had often drawn upon the ‘Judeo-Christian’ prophetic tradition to critique power and inequality in U.S. society” (Danielson 2019, p. 1).

Like other “religious traditions”, American civil religion has its sacred texts (e.g., the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution), symbols (e.g., the American flag, the Statue of Liberty, and the Liberty Bell), rites (e.g., 4 July, Memorial Day, and Thanksgiving), and places (e.g., Washington and Lincoln monuments) (Gardella 2014). However, if one were to ask random Americans if they followed, or were even aware of, American civil religion, they would almost certainly say no. Nevertheless, many, if not most, would probably recognize the general outlines of American civil religion because it is part and parcel of the culture in which they were raised and socialized. By interacting with its rituals and symbols over time, they have become familiar with its stories, practices, and beliefs (Christenson and Wimberley 1978; Smith 2003; Smith et al. 1998; Wimberley 1976). Consider, for example, Thanksgiving. Although it receives little attention in most civil religion treatments, it is, in many ways, the quintessential American civil religion ritual (Reagan 1982). It is the American exodus story. Like the ancient Israelites, many of whom did not descend from the families who fled from Pharaoh’s wrath but later affiliated with those who had (Friedman 2017), most Americans do not descend from the Pilgrims. However, just as the Exodus story was embraced by those who chose to worship Yahweh, the Thanksgiving story has been adopted by many who count themselves as Americans1.

For evidence, Bellah turns to America’s founding documents, speeches by key individuals (e.g., Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address), and, particularly, presidential inaugural addresses2. For instance, he notes that in John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address, Kennedy refers to “God” three times: twice at the beginning and once at the end, and he argues that understanding why and how Kennedy does this can tell us a lot “about American civil religion” (Bellah 1967, p. 2). Bellah recognizes that some will say that we should not make too much of Kennedy’s references to God. Their presence simply reflects religion’s “ceremonial significance” in American life, which obtains a quadrennial “sentimental nod” that placates “the more unenlightened members of the community” (Bellah 1967, p. 2). Bellah contends, however, that Kennedy’s references to God help frame the entire address and provide “a religious dimension for the whole fabric of American life, including the political sphere… [reaffirming], among other things, the religious legitimation of the highest political authority” (Bellah 1967, pp. 3–4).

Bellah takes pains to argue that American civil religion is not Christianity in disguise but rather a separate phenomenon that exists alongside America’s established religious traditions. As such, one can be a good Christian and still embrace the American civil religion narrative. Bellah believes that it is not coincidental that in their inaugural addresses, while all presidents referred to God3, none ever referred to Jesus Christ4. Why? Pointing to Kennedy’s address, he argues that:

[Kennedy] did not because these are matters of his own private religious belief and of his relation to his own particular church; they are not matters relevant in any direct way to the conduct of his public office. Others with different religious views and commitments to different churches or denominations are equally qualified participants in the political process. The principle of separation of church and state guarantees the freedom of religious belief and association, but at the same time, clearly segregates the religious sphere, which is considered to be essentially private, from the political one.(Bellah 1967, p. 3.)

Bellah’s thesis generated considerable debate over defining civil religion, how to quantify it, and whether it is simply religious nationalism in disguise (Bellah and Hammond 1980; Danielson 2019; Christenson and Wimberley 1978; Gehrig 1981; Richey and Jones 1974; Wimberley 1976). Although this paper considers some of these debates below, its purpose is to empirically examine Presidents Trump’s and Biden’s inaugural addresses, looking for evidence of what some would consider aspects of American civil religion. In particular, it assesses the prominence of references to God and other terms associated with America’s civil religion in their inaugural addresses. It focuses on inaugural addresses as they served as Bellah’s primary focus in his initial article. For its analysis, this paper draws on a form of computational text mining known as semantic network analysis, which is similar to social network analysis5, except that the nodes are words, terms, or concepts, and the ties between them capture some form of co-occurrence in a particular unit of text, such as a paragraph, sentence, saying, or tweet (Diesner 2015; Diesner and Carley 2011; Drieger 2013; Everton and Cunningham 2020; Hoffman et al. 2018; Rule et al. 2015). As its name suggests, semantic network analysis seeks to uncover the underlying semantic structure of a text or texts (Diesner and Carley 2011; Drieger 2013) so that “higher-level units of meaning” or topics can be identified from the patterns of ties between terms, such as identifying a text’s overall structure and which words play a more central role (Hoffman et al. 2018)6. For example, centrality measures help identify those that (semantically) lie close to other words, those that help bind the text together, and those that appear frequently with other frequently appearing words. Words that score high across multiple centrality measures can be seen as playing a vital role in a text’s narrative.

This paper proceeds as follows: It begins by offering a brief review of American civil religion. This is necessarily short and far from exhaustive to allow room for the following analysis. Numerous papers and books explore these issues in greater detail for those who are interested (see, e.g., Bellah and Hammond 1980; Christenson and Wimberley 1978; Coleman 1970; Demerath and Williams 1985; Edwards and Valenzano 2016; Gardella 2014; Gehrig 1981; Gorski 2017a, 2020; Lüchau 2009; Wimberley 1976). The following section discusses the data and methods used in our analysis. The texts of presidential inaugural addresses are easy to access, but like most statistical methods, semantic network analysis requires analysts to make certain decisions, such as which terms and concepts to retain and what constitutes a tie between them. The paper then turns to analyzing the semantic networks generated from the addresses. It begins by examining the network’s overall structure (e.g., size, density, centralization) before exploring the centrality of terms that some might associate with the American civil religion thesis, as well as those simply reflecting nationalist sentiments. It concludes with a brief summary and suggestions for how analysts can further explore civil religion in general and its presence in presidential discourse in particular.

2. Civil Religion and Its Discontents

Jean-Jacque Rousseau first coined the term “civil religion” when he proposed its establishment to further his idea of a “social contract” (Rousseau 1997): “He intended it to denote a constructed religion, a form of deism that would instill in citizens a love of country and a motivation to civic duty” (Demerath and Williams 1985, p. 155). Bellah understands American civil religion differently. Influenced by Durkheim ([1912] 1995), he sees it as more bottom-up than top-down, as “voluntary rather than compulsory” (Gorski 2017a, p. 16). He argues that it was born in the settling of the new world, forged in the American Revolution, and refined during the war between the states (Bellah 1975). Philip Gorski (2017a) expands Bellah’s argument considerably, examining the development of the civil religious tradition from the perspective of a diverse set of individuals, such as Hannah Arendt, John Calhoun, W.E.B. Du Bois, Jerry Falwell, Billy Graham, H.L. Mencken, and Reinhold Niebuhr. Interestingly, Matthew Sutton (2014) believes the success of the civil religious tradition can be traced back to when President Roosevelt and his advisors consciously sought to craft a Judeo-Christian civil religion that transcended confessional and ethnic divisions and reinforced the idea of a shared morality that underlies American citizenship7. President-elect Dwight Eisenhower consciously or unconsciously reflected this vision when he famously quipped, “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is” (quoted in Weiss 2016, p. 146)8.

In his original essay, Bellah viewed it as a potentially unifying factor and source for democratic renewal. A few years later, he was less optimistic. The heady days of the civil rights movement and the optimism of the Kennedy Administration (“the best and the brightest”) had given way to the bane of the Vietnam War and the embarrassment of Watergate, leading him to conclude that American civil religion had become “an empty and broken shell” (Bellah 1975, p. 142). He believed that it had lost its “power to motivate support for shared national goals” (Compton 2019, p. 2)9. Bellah eventually dropped using the term altogether (Bortolini 2012).

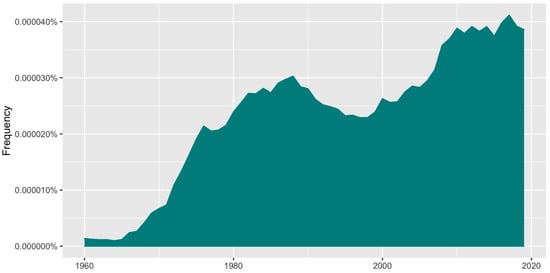

Bellah’s abandonment of civil religion did not prevent others from drawing on the concept because they found it valuable and important (Weiss and Bungert 2019). Figure 1, for instance, plots the relative frequency of the phrase “American civil religion” in English language books in the U.S. from 1960 to 201910. It captures the spike of interest in the term in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s following the publication of Bellah’s initial essay. It suggests that a slight decline in its usage occurred between the late 1980s and 1990s before a resurgence began around 2000, which appears to continue to the present day.

Figure 1.

Relative frequency of “American Civil Religion” in English language books, 1960–2019.

Not all who write about civil religion are fans. Some dismiss it as simply a thinly veiled version of (or excuse for) religious nationalism (Danielson 2019; Long 1974; Marvin and Ingle 1996)11. Danielson (2019), for instance, believes that Bellah’s contention that American civil religion facilitated the “reform and renewal” of the American experiment is “historically inaccurate”. She contends that although “there is indeed a dominant language of American nationalism and one that has largely reflected the culture of the Anglo-Protestant majority… it was far from universal and often rested upon the exclusion and repression of alternative and oppositional identities and solidarities”. She believes scholars should abandon the concept of civil religion in favor of nationalism because it is “a far more slippery concept that elides questions of power, identity, and belonging that nationalism places at the center of inquiry” (Danielson 2019, p. 1).

Gorski (2017a) disagrees. He argues that religious nationalism in general, and Christian nationalism in particular, differs from American civil religion in that it is tied to the idea of blood, which is not only seen as a sign of ethnic purity but also harbors allusions to bloody conquests and sacrifices in war12. Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry draw a similar distinction between religious (Christian) nationalism and American civil religion:

While civil religion has held that “Providence”, the “Creator”, or “Nature’s God” demands our exemplary fairness, beneficence, and faithful stewardship if we are to retain our blessed inheritance, the Christian nationalist tradition… views God’s demand more in terms of allegiance to our national—almost ethnic—Christian identity. Christian nationalism is rarely concerned with instituting explicitly “Christ-like” policies or even policies reflecting New Testament ethics at all. Rather, Christian nationalists view God’s expectations of America as akin to his commands to Old Testament Israel. Like Israel, then, America should fear God’s wrath for unfaithfulness while assuming God’s blessing—or even mandate—for subduing the continent by force if necessary.(Whitehead and Perry 2020, p. 11)13

Others question whether there is something one could call “civil religion” (Wilson 1974). For instance, Roderick Hart (1977) argues that it is better understood as “civic piety” as it lacks what, in his mind, are essential elements of religion. Similarly, Jones and Richey (1974) offer up five different understandings of civil religion: folk religion, religious nationalism, democratic faith, Protestant civic piety, and transcendent universal religion of the nation, locating Bellah with the last of these.

Be that as it may, Robert Wuthnow (1988a, 1988b) argues that American civil religion evolved into two related but distinct strands: one, a conservative or “priestly” strand, focuses more on America’s greatness, while a second, its liberal or “prophetic” strand, the strand that Bellah embraced, emphasizes America’s obligation to live up to its highest ideals14: “The conservative vision offers divine sanction to America, legitimates its form of government and economy, explains its privileged place in the world, and justifies a uniquely American standard of luxury and morality. The liberal vision raises questions about the American way of life, scrutinizes its political and economic policies in light of transcendent concerns, and challenges Americans to act on behalf of all humanity rather than their interests alone. Each side inevitably sees itself as the champion of higher principles and the critic of current conditions” (Wuthnow 1988a, p. 99). President Ronald Reagan perhaps articulated the priestly strand as well as anyone. Consider, for example, his 1982 Thanksgiving Proclamation:

I’ve always thought that a providential hand had something to do with the founding of this country. God had His reasons for placing this land between two great oceans to be found by a certain kind of people; that whatever corner of the world they came from, there would be in their hearts a fervent love of freedom and a special kind of courage, the courage to uproot themselves and their families, travel great distances to a foreign shore, and build there a new world of peace and freedom… Today we have more to be thankful for than our pilgrim mothers and fathers who huddled on the edge of the New World that first Thanksgiving Day could ever dream. We should be grateful not only for our blessings, but for the courage and strength of our ancestors which enable us to enjoy the lives we do today.(Reagan 1982, p. 62.)

In contrast, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. may have best captured the essence of the prophetic strand in his “I Have A Dream” speech (see Chappell 2004):

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; “and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together”. This is our hope, and this is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day. And this will be the day—this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning: “My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing/Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride/From every mountainside, let freedom ring!” And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.(King [1963] 1986, pp. 219–20)

More recently, Gorski (2017a) argued that American civil religion lies between two poles: radical secularism and religious nationalism. The former reflects a “blend of cultural elitism and militant atheism that envisions the U.S. as part of an Enlightenment project threatened by the ignorant rubes who still cling to traditional religion”. It draws mainly on secular Western philosophy, libertarian liberalism, and notions of a total separation between church and state (Gorski 2017a, p. 2). In contrast, religious nationalism in the U.S. is a “blend of apocalyptic religion and imperial zeal that envisions the U.S. as a righteous nation charged with the divine commission to rid the world of evil and usher in the Second Coming”. It reflects themes in the Judeo-Christian tradition, particularly the Bible’s conquest narratives and apocalyptic books (Gorski 2017a, p. 2). Gorski contends that American civil religion differs from these extremes in that it is informed by both the Judeo-Christian tradition and secular Western philosophy, in particular, the prophetic strand found in the Hebrew and Christian scriptures and the political philosophy of civic republicanism. The prophetic strand “stresses the covenants formed between God and his people in the Pentateuch and then deepened and reaffirmed in the books of the prophets with the interrelated concepts of covenant and judgment” (Gorski 2017a, p. 19). Civic republicanism assumes that self-governing communities and a republic (i.e., a representative government) are natural outgrowths of our “social” and “political” dispositions (Gorski 2017a, p. 24). The prophetic strand to which Gorski refers is associated primarily with the prophets of the Hebrew Bible, in particular, books such as Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Amos (Brueggemann 1978), and not apocalyptic texts, such as Daniel and Revelation, which are mined in some Christian circles to date Jesus’s return (e.g., LaHaye and Jenkins 1995; Lindsey and Carlson 1990). Civic republicanism is associated with civil society, civic virtue, and mixed government. It sees self-government as a “positive good rather than a necessary evil” and holds that political history is cyclical (i.e., progress, corruption, and renewal) rather than linear (ever-increasing progress) (Gorski 2017a, pp. 26, 96).

Gorski penned his original analysis of American civil religion before Donald Trump’s inauguration in 2017. However, it is notable that in his preface to the paperback edition of the book (Gorski 2019) and in an earlier article (Gorski 2017b), both of which Gorski wrote after Trump’s inauguration, he argues that Trump “preaches” more of a secular nationalism than a religious one:

It is shorn of the Scriptural citations and allusions that still adorned the rhetoric of recent Presidents, Republicans, and Democrats alike, from Reagan to Obama. All it retains from Christianity are faint echoes of a deep story: tropes of pollution and purification, invasion and resistance, apocalypse and salvation, corruption and renewal. These tropes have long since become stock elements of our popular culture. So much so, in fact, that one could probably internalize them without any formal exposure to Christian teachings.(Gorski 2017b, p. 348.)

Here, Gorski echoes some of Bonikowski and DiMaggio’s (2016) findings regarding American “nationalisms”. Bonikowski and DiMaggio identify four types of nationalism (creedal, disengaged, restrictive, and ardent), and they find that “ardent nationalists” and “white evangelicals” are practically indistinguishable from one another in terms of their political and social values.

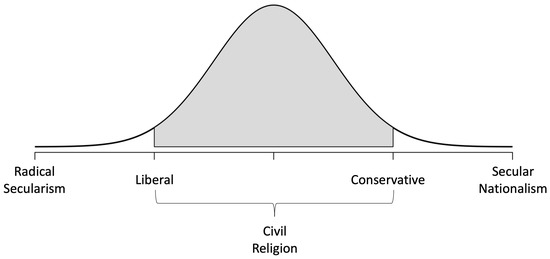

This suggests that, at least currently, rather than lying between radical secularism and religious nationalism, American civil religion lies between radical secularism and a “Trumpian” secular nationalism. Figure 2 combines Wuthnow’s and Gorski’s understanding of American civil religion, lying between radical secularism and secular nationalism, with civil religion’s liberal version closer to radical secularism and its conservative version closer to secular nationalism.

Figure 2.

Radical secularism, secular nationalism, and America’s two civil religions.

How central will nationalist and civil religion references appear in their inaugural addresses? Whitehead, Perry, and Baker (Baker et al. 2020; Whitehead et al. 2018; Whitehead and Perry 2020) showed that holding beliefs associated with Christian nationalism strongly predicts whether someone voted for Trump. Moreover, Kristin Kobes Du Mez (2020, pp. 4, 6–7) documented how white evangelicals, one of Trump’s largest voting blocks, have long been primed to support someone who embodied a “rugged, aggressive, militant masculinity” and embraced “patriarchal authority, gender difference, and Christian nationalism”. Nevertheless, Trump may have intuited that winning the presidential election meant he needed to appeal to nationalists beyond the ranks of the white evangelicals. If so, we should find evidence of the secular nationalism identified by Gorski in Trump’s inaugural address. It is also likely that Trump’s address will show little love for American civil religion and, in fact, may seek to repudiate it if Sutton (2014) is correct that its purpose, at least since Roosevelt, is to transcend confessional and ethnic divisions. Add to this the fact that as Trump only marginally identifies as a Presbyterian and appears uncomfortable, or at least unfamiliar, with religious discourse, one might expect to find a minimal amount of religious language in his inaugural address.

In contrast, Biden’s winning coalition was more culturally and racially diverse than Trump’s, suggesting that he would have been motivated to draw on civil religion (at least, Roosevelt’s version) to shore up a broad, but hardly unified, confessional and ethnic coalition. Moreover, because Biden is a practicing Roman Catholic, he is perhaps more comfortable than Trump in using religious language. Thus, we should not be surprised to discover that American civil religious discourse is more central to Biden’s address, even though the Democratic Party is the more secular of the two major parties (Bolce and De Maio 2002; Margolis 2018). Finally, although Biden’s supporters are less likely to embrace nationalistic tendencies than Trump’s (although some do), presidential inaugural addresses are a quadrennial national ritual. Thus, we should also expect to find some nods to national pride in Biden’s address, but they will almost certainly be fewer and less central than in Trump’s.

3. Data and Methods

The primary data used in this analysis are the presidential inaugural speeches of Trump and Biden. However, the first inaugural speeches of Kennedy, Reagan, and Obama are included to provide additional context. The paper includes Kennedy’s as it served as one of Bellah’s primary examples, Reagan’s because he exemplifies American civil religion’s “priestly” strand, and Obama’s because it was a 2008 speech of his during the presidential campaign that inspired Gorski to pen his monograph on American civil religion15. As noted earlier, it employs semantic network analysis to analyze the addresses. Here, the weight of a tie between two words reflects the number of joint appearances of words i and j in the same sentence16. To eliminate isolated and disconnected clusters of words, this paper limits its analysis to each network’s main component, the largest set of nodes (words) that can reach one another directly or indirectly. It is the largest connected cluster of words in each inaugural address. Defining ties in terms of co-occurrence within individual paragraphs was considered. However, because some presidents spoke in longer paragraphs than others, doing so would create a “centrality” bias for terms that appear in longer paragraphs17. Using sentences is not a perfect solution as it is possible that some presidents spoke in longer sentences than others, but using sentences minimizes this potential bias.

The following analysis begins by calculating and comparing commonly used topographical measures for each network: density, average degree, compactness, clustering coefficient, centralization, diameter, average path length, and size. Density, average degree, compactness, and clustering coefficient all measure a network’s interconnectedness. Density is the standard measure and equals the total number of ties divided by the total possible number of ties. It is, however, inversely associated with network size because as actors join a network, the number of possible ties increases exponentially. Thus, when comparing networks of different sizes, analysts often turn to average degree (de Nooy et al. 2011), which equals each actor’s average number of ties in the network. Cohesion and compactness calculate the extent to which each node can reach every other node in a network (Borgatti et al. 2013). Cohesion equals the proportion of all pairs of actors that can either directly (e.g., a friend) or indirectly (e.g., a friend of a friend) reach one another. However, as cohesion always equals 1.00 in main components (because each node can reach every other node), we focus on compactness, which weights the cohesion score by the average (path) distance between all pairs of actors. Finally, the clustering coefficient (Watts 1999; Watts and Strogatz 1998), which has historically been known as ego network density (Davis 1967; Marsden 1987), first calculates the density of ties between each actor’s neighbors (i.e., those words to which an actor has ties) and then averages those density scores across all actors.

The paper estimates network spread with measures of centralization, diameter, and average path length. Degree centralization is the standard measure of network spread, but betweenness centralization is also calculated. Both use variation in actor centrality scores (in this case, degree and betweenness centrality; see definitions below) to measure the level of centralization. More variation yields higher centralization scores. Diameter equals the longest, shortest path (geodesic) between all connected pairs of nodes, while average path length equals the average length of all geodesics between all connected pairs of nodes. Larger diameters and average path lengths indicate greater network spread; however, as they are a function of network size, we need to interpret results carefully, especially when comparing different-sized networks. Finally, size equals the number of unique words (nodes) in each network.

Next, the paper draws on four standard centrality measures to identify keywords appearing in the addresses: degree, closeness, betweenness, and eigenvector. Within the context of semantic networks, degree helps identify terms that frequently occur with other terms. It is not identical to word counts as it equals the number of ties a word has to other words, which is, in part, a function of sentence length (e.g., words that appear in longer sentences will have more ties than those that appear in shorter sentences). Nevertheless, the two often correlate highly with one another. Words that score high in closeness may not have the most ties, but on average, they lie closer (in terms of path length) to other words in the network. Betweenness centrality captures the extent to which a node lies on the shortest path between all other pairs of nodes in a network. In standard network analysis, it is often seen as capturing a node’s brokerage potential; here, words with high betweenness centrality scores are probably best seen as those that help hold the network (i.e., its “narrative”) together. Eigenvector centrality is similar to degree except that it weights each node’s score by the number of its neighbors’ ties. It identifies relatively well-connected nodes tied to other well-connected nodes. As such, it can sometimes highlight nodes that other centrality measures ignore. For this particular analysis, we can see it as identifying words of high importance (i.e., status) for both texts. Finally, we can interpret words that score high in all four measures as telling us which concepts genuinely play a central role in the inaugural addresses of Presidents Trump and Biden.

4. Results and Analysis

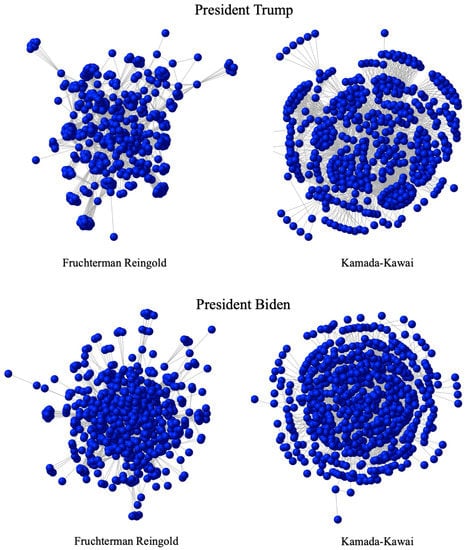

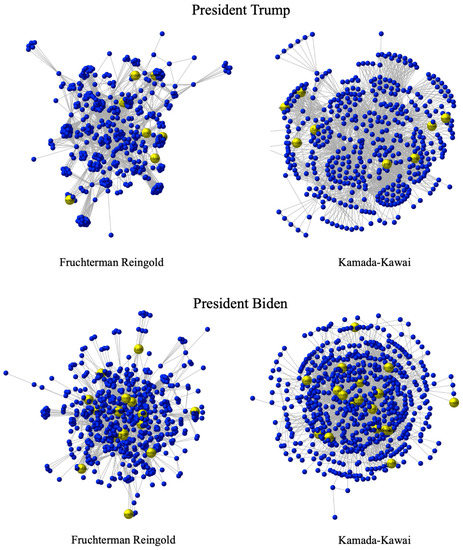

Figure 3 presents the semantic networks of Presidents Trump (top) and Biden (bottom)18. Two standard layout algorithms were used to visualize the networks: Fruchterman Reingold (Fruchterman and Reingold 1991) and Kamada-Kawai (Kamada and Kawai 1989)19. The paper uses two because although layout algorithms locate nodes that share a tie (or ties to similar others) close to one another in network graphs, how they do so can differ (e.g., the amount of “pull” of a shared tie varies across algorithms). Thus, visualizing networks using multiple layout algorithms can help tease out different aspects of a network. This is perhaps seen best in the Kamada–Kawai visualizations. Both exhibit what some might call a core-periphery structure. In both visualizations, Biden’s address appears denser and more compact. However, this may reflect that his speech was somewhat longer, resulting in a larger semantic network that the layout algorithms had to “squeeze” into the same size of visual space.

Figure 3.

Semantic networks of Trump and Biden inaugural addresses.

Topographical metrics can help sort questions such as these out. These are presented in Table 1, which also includes the corresponding metrics for Kennedy’s, Reagan’s, and Obama’s first inaugural speeches. One could argue that structurally, Trump’s inaugural address resembles Obama’s more closely than Biden’s, while Biden’s most closely resembles Reagan’s. Neither is similar to Kennedy’s, which is highly interconnected and relatively centralized compared to the others (except for betweenness centralization). Focusing on Biden and Trump’s addresses, Biden’s contains more unique words (615) than Trump’s (452), but Trump’s is more compact and interconnected. It scores higher in terms of density (0.038 vs. 0.021), average degree (17.350 vs. 13.080), compactness (0.391 vs. 0.350), and clustering coefficient (0.886 vs. 0.807). Thus, although in Figure 3, Biden’s appears more interconnected, this is primarily a function of its size. Trump’s semantic network is also more centralized (0.175 vs. 0.126; 0.146 vs. 0.092) and less disbursed, as measured by both the network diameter (5 vs. 7) and average path length (2.811 vs. 3.127). This is also due somewhat to the comparative sizes of the two networks (i.e., as noted above, diameter and average path length are, in part, a function of size). However, it also suggests that Trump’s address revolved around a central theme more than Biden’s. This is unsurprising as his 2016 campaign focused on “making America great again” by protecting the American people from unfair and sometimes dangerous foreign competition.

Table 1.

Topographic metrics of selected presidential inaugural addresses.

Consider, for example, Table 2, which presents the top ten ranked words by degree, closeness, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality. “American”, “America”, “country”, “people”, “nation”, and “great” consistently rank in the top ten in terms of degree, closeness, and betweenness centrality. Only with eigenvector do we see an exception to this, where words such as “many”, “citizens”, “factories”, and “children” appear in the top ten. They do so mainly because all are located in the address’s longest sentence, one that taps into the economic anxiety that some believe helped Trump win the 2016 election and was a central theme of his campaign (Porter 2016):

Table 2.

President Trump’s first inaugural address top 10 ranked words by centrality.

But for too many of our citizens, a different reality exists: Mothers and children trapped in poverty in our inner cities; rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation; an education system, flush with cash, but which leaves our young and beautiful students deprived of knowledge; and the crime and gangs and drugs that have stolen too many lives and robbed our country of so much unrealized potential.

The sentence’s length not only increases the number of ties for each word in the sentence but also increases the number of ties of the words to which they have ties. As such, they are well-connected words with ties to other well-connected words, the very type of connectivity that eigenvector centrality captures. Interestingly, possibly the most memorable line of Trump’s inaugural address occurs just after this sentence: “This American carnage stops right here and stops right now”. Notably, no words one might associate with American civil religion appear in any of the four rankings20, a result consistent with Gorski’s (2017b) contention that Trump advocates a form of secular nationalism that shows little interest in or is perhaps antagonistic towards the American civil religious tradition. After examining the top-ranked words in Biden’s address, we will consider this fact in greater detail below.

Table 3 presents the top ten ranked terms in President Biden’s address for the four centrality measures. As with Trump’s, many are associated with national pride. In fact, some of the top-ranked terms in Trump’s address are also top-ranked in Biden’s: “nation”, “America”, and “American”. Several others, however, are unique to Biden’s, such as “days”, “here”, “centuries”, “work”, “through”, “what”, “know”, and “history”. Notably, “story” is one of the top-ranked words in terms of eigenvector centrality. Biden uses it to refer to “the American story”, a “story of hope, not fear… of unity, not division… of light, not darkness…”, a story “of decency and dignity… of greatness and goodness”, one that inspires Americans to strive for “truth and justice” and be a “beacon to the world”. He also compares it to the song “American Anthem”, which calls on Americans to “give their best” to their country in what Biden calls the “unfolding story of our nation”. Biden’s use of the term ties it to notions of hope and light, decency and greatness, justice and truth, recurring themes in American civil religion discussions.

Table 3.

President Biden’s first inaugural address top 10 ranked words by centrality.

We can gain a better sense of how the two addresses compare in their use of nationalist terms by attending to the normalized rankings (in parentheses) of “nationalist” terms in both21, which are presented in Table 4. Trump’s address includes 22 such words (4.9% of the total), while Biden’s contains just 17 (2.8% of the total). The table separates the words ranked in the top ten percent (i.e., words with normalized rankings of 10 or less) for each of the four centrality measures. At a glance, we can see that far more nationalist terms appear in the top 10 percent of Trump’s address than in Biden’s. Moreover, across all four centrality measures, the mean and median rankings of nationalist terms are higher (i.e., the scores are lower) in Trump’s address than in Biden’s. Nevertheless, t-tests comparing means and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests comparing medians do not indicate statistically significant differences between the rankings22. As such, although there appear to be substantive differences between the two addresses in their use of nationalist terms, we cannot conclude with any statistical certainty that there are (McCloskey 1995; Ziliak and McCloskey 2008).

Table 4.

Normalized rankings of nationalist terms in Trump and Biden inaugural addresses.

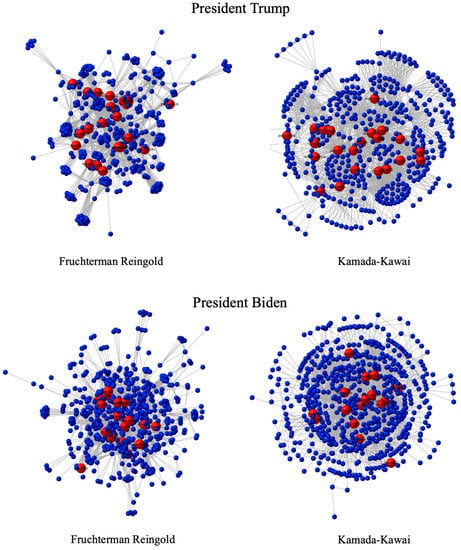

Figure 4 captures these results visually. Like Figure 3, it plots the semantic networks of Presidents Trump (top) and Biden (bottom) using the Fruchterman Reingold and Kamada–Kawai algorithms. However, it differs in that terms associated with nationalism are larger and colored red. As we can see, nationalist words appear more frequently in Trump’s smaller network, but it is difficult to visually discern the relative centrality of the terms in the two networks.

Figure 4.

Semantic networks of Trump and Biden inaugural addresses; nationalist terms in red.

Table 5 explores the centrality of words one might associate with American civil religion. It presents their normalized rankings across the four centrality measures, breaking out, as in Table 4, words ranking in the top ten. As the table indicates, although Biden and Trump used some of the same words (“bible”, “bless”, “god”, “souls”)23, Biden used far more (18) than Trump (8), and Biden’s are consistently ranked higher. Several (“story”, “justice”, “anthem”, “sacred”, “prayers”, “faith”, “god”, “hallowed”, “soul”), in fact, rank in the top ten, while none of Trump’s do (although “flag” comes close in terms of closeness centrality). In addition, for all four centrality measures, the mean and median rankings of American civil religion terms are higher in Biden’s address than in Trump’s. However, unlike the earlier comparison of nationalist terms, t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests find statistically significant differences between the rankings. Specifically, they indicate that the rankings differ statistically for degree, closeness, and eigenvector centrality24. Only for betweenness are there no statistically significant differences in the rankings. In this regard, however, this reflects that the betweenness scores for most civil religion terms equaled zero in both addresses.

Table 5.

Normalized rankings of nationalist terms in Trump and Biden inaugural addresses.

Nevertheless, a glance at the table shows that far more civil religion terms rank higher in Biden’s address than in Trump’s, even for betweenness. As such, unlike the nationalist terms presented in Table 4, the differences in Table 5 are substantial and statistically significant. Here again, we see evidence that while Trump has little interest in and is perhaps hostile toward the American civil religious tradition, Biden is not. Like President Roosevelt (and maybe Robert Bellah), Biden sought to draw on American civil religion’s prophetic strand to transcend America’s confessional and ethnic divisions, which have become increasingly polarized in recent years (Mason 2018).

Figure 5 visually captures these results. Like Figure 4, it plots the semantic networks of Presidents Trump (top) and Biden (bottom) using the same two layout algorithms, but here, words associated with American civil religion are larger and colored yellow. As with the results presented in Table 5, the figure clearly shows that Biden employs the rhetoric of American civil religion far more than Trump.

Figure 5.

Semantic networks of Trump and Biden inaugural addresses; American civil religion terms in yellow.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Although this paper focused primarily on comparing two inaugural addresses, one could easily expand what was undertaken here to include the inaugural addresses of other presidents, although doing so would necessarily entail dropping some of the detailed analysis contained here. Tracing the evolution of presidential inaugural addresses from Washington to the present could prove enlightening. Such an analysis could be broken down into eras, considering the effect that wars, economic conditions, and other exogenous factors have had on what presidents have emphasized and what they have not25. Of course, there is no need to limit future analyses to just inaugural addresses. Bellah may have focused on them in his first essay, but he later expanded his investigation to include the speeches and writings of other prominent Americans, such as John Winthrop, Benjamin Franklin, Herman Melville, and James Baldwin (Bellah 1975). Furthermore, as we saw, Gorski (2017a) considers the speeches and writings of various individuals.

It is also important to emphasize that although both Trump and Biden used discourse consistent with American civil religion in their inaugural addresses, American civil religious discourse was not the focus of their speeches. This was especially true for Trump. None of the words he used associated with American civil religion ranked in the top ten percent on any of the four centrality measures. Their average (normalized) ranking ranged from 45.88 percent for degree centrality to 78.96 percent for betweenness. Although for Biden, several words did rank in the top ten percent, far more did not. Their average (normalized) ranking ranged from 29.42 percent for degree centrality to 65.09 for betweenness. This certainly is not surprising, however. Bellah notes that Kennedy’s use of “God” in his inaugural address plays a peripheral role. In particular, he argues that it serves as a “frame” for Kennedy’s more “concrete remarks” (Bellah 1967, p. 2), and this is perhaps one way to understand how Trump and Biden use American civil religion language. The analysis here, of course, focuses on more words than just “God”. At least for Biden, they are sprinkled throughout his address, with some, as we have seen, figuring quite prominently. Thus, at least for Biden, rather than serving so much as a “frame”, they appear to set the underlying tone of his address. Their allusions to American civil religion’s stories, values, events, and nature seem to hover in the background, while other, more concrete aspects of his address come to the fore. The same probably cannot be said of Trump’s address, however. They are so few and far between that, at best, they serve as a frame for the rest of Trump’s speech.

Does the above analysis “prove” Bellah’s thesis? Of course not. No amount of empirical data can do that. Some will interpret the prevalence of certain beliefs, practices, and discourse as supporting Bellah’s thesis (Gorski 2017a); others will see them as merely confirming the pervasiveness of religious nationalism in the United States (Danielson 2019). However, the analysis does show that language that some would consider consistent with American civil religion can be found in the inaugural addresses of both Biden and Trump. However, the level at which Biden and Trump employ American civil religious language differs. Biden not only used far more terms associated with American civil religion, but they played a much more central role. If Gorski (2017a) is correct that American civil religion can help rebuild “the vital center” and recover what was once a vibrant civil society, then the central role that American civil religion played in Biden’s inaugural address can be seen as a positive. However, one cannot help but wonder whether Bellah and others are right that American civil religion has lost its power to bring together disparate aspects of American society. American civil religion may be a throwback to an earlier time in American history, a set of beliefs, symbols, and practices that hold little or no sway in our current era, neither on the secular left nor the secular right (see Figure 2). The results presented here are certainly consistent with such a conclusion.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All Presidential inaugural addresses are available through the R package quanteda (Benoit et al. 2018).

Acknowledgments

I thank Daniel Cunningham and Brendan Knapp for their help in writing the R scripts for analyzing the inaugural addresses.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This helps explain why when historians highlight some of the negative aspects of Thanksgiving (e.g., Deloria 2019; Ritschel 2020; Turner 2020), they are often greeted with hostility (e.g., Wallace 2019). |

| 2 | Bellah developed his argument in more detail in later essays and books (see, e.g., Bellah 1970, 1975; Bellah and Hammond 1980). |

| 3 | The one exception is Washington’s second inaugural address, which was unusually short (only 135 words). |

| 4 | The same cannot be said of presidential Christmas addresses, however. As Domke and Coe (2008) note, since 1970, many of these addresses have included the word “Jesus” in them. |

| 5 | In fact, the paper applies social network analytic methods in its analysis. |

| 6 | It shares similarities with topic modeling approaches, such as latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), which seek to identify latent topics within a collection of texts (Blei et al. 2003; McFarland et al. 2013; Mohr and Bogdanov 2013). |

| 7 | I am grateful to the anonymous reviewer who pointed this out. |

| 8 | David Weiss believes that “no other president before or since has so succinctly, if unwittingly, captured the essence of American civil religion and the role of the president in its leadership” (Weiss 2016, p. 146). |

| 9 | Compton (2019) argues that if it is true that American civil religion has lost its power, it is partly because the formal religious institutions that once transmitted and supported it (e.g., the National Council of Churches) have collapsed. |

| 10 | The data are derived from Google’s Ngram Viewer, which charts the relative frequency of any word or group of words between 1500 and 2019 in Google’s corpus of digitized English, Chinese, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Russian, and Spanish books. Scholars are increasingly using Ngrams to study religion, culture, and other aspects of human behavior (see, e.g., Finke and McClure 2017; Michel et al. 2011; Putnam and Garrett 2020; Shiller 2019). The data were downloaded and plotted with smoothing using the R package, ngramr (Carmody 2020). |

| 11 | By itself, nationalism is (or can be) a neutral term. It is the idea that states are to be ruled in the name of a nation rather than dynastic succession (e.g., kingdoms), a particular civilization (e.g., empires), or God (e.g., theocracies). As such, it opposes foreign rule or any type of outside interference that disregards the interests of the national majority (Wimmer 2021; Wimmer and Feinstein 2010; Wimmer and Min 2006). However, when nationalism insists on aligning itself with a single cultural identity (e.g., ethnic, religious), it often holds up a snapshot of a particular moment of a nation’s history as the ideal picture of its identity; this leads some observers to argue that while identity politics is the politics of minority groups, nationalism is the identity politics of the majority tribe (Miller 2022). |

| 12 | Gorski does believe that Bellah did not draw “a clear enough line” between the two, however (Gorski 2017a, pp. 16–17). |

| 13 | It is useful to compare the survey questions that Whitehead et al. (2018, p. 155) use for measuring Christian nationalism with those Wimberley (1976, p. 343) use to capture American civil religion. Only Whitehead, Perry, and Baker’s fifth question might be considered to be tapping into the same dimension that Wimberley sought to capture. |

| 14 | For a similar argument, see Murphy (2008). |

| 15 | Gorski notes that the speech drew on imagery from the Hebrew Bible, spoke about founding covenants, referred to America’s original sins (e.g., slavery), and held up notions of a Promised Land at which America had yet to arrive: “I immediately recognized this blend of civic and religious motifs. The late Robert Bellah had famously described it as ‘the American civil religion’ and, more generally, as America’s ‘founding myth’” (Gorski 2017a, p. xvii). |

| 16 | Before generating the co-occurrence matrices, commonly used words (e.g., at, which, for) were removed. |

| 17 | Why? As each word would have a tie to every other word in a paragraph, words that appear in longer paragraphs would have more ties and thus be more central than words that appear in shorter paragraphs. |

| 18 | Labels are hidden because when they are included, they overlap and are unreadable. |

| 19 | Unless otherwise noted, igraph (Csárdi and Nepusz 2006) was used to generate visualizations and calculate metrics. |

| 20 | Scholars disagree on which words/terms are associated with American civil religion and which ones are associated with nationalism. For instance, where Bellah (1967) sees references to civil religion, Danielson (2019) sees markers of nationalism. The terms identified in this paper draw from the works of other scholars who have explored one or both sets of concepts (e.g., Baker et al. 2020; Bonikowski and DiMaggio 2016; Christenson and Wimberley 1978; Whitehead et al. 2018; Whitehead and Perry 2020; Wimberley 1976). |

| 21 | Normalized rankings are used because the size of Biden’s and Trump’s semantic networks differ. A word’s ranking is calculated by dividing its raw ranking by the number of words in the network (size) and multiplying the result by 100 in order to place the rankings on a scale from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating higher rankings. |

| 22 | The results are available upon request. |

| 23 | Trump also uses the word “justice” but only in reference to Chief Justice Roberts. |

| 24 | See notes 22 above. |

| 25 | Rule et al. (2015) conducted a similar analysis of the presidential state of the union addresses. |

References

- Baker, Joseph O., Samuel L. Perry, and Andrew L. Whitehead. 2020. Keep America Christian (and White): Christian Nationalism, Fear of Ethnoracial Outsiders, and Intention to Vote for Donald Trump in the 2020 Presidential Election. Sociology of Religion 81: 272–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellah, Robert N. 1967. Civil Religion in America. Daedalus 96: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N. 1970. Beyond Belief: Essays on Religion in a Post-Traditional World. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N. 1975. The Broken Covenant: American Civil Religion in Time of Trail. New York: Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N., and Philip E. Hammond. 1980. Varieties of Civil Religion. San Francisco: Harper and Row, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, Kenneth, Kohei Watanabe, Haiyan Wang, Paul Nulty, Adam Obeng, Stefan Müller, and Akitaka Matsuo. 2018. quanteda: An R Package for the Quantitative Analysis of Textual Data. Journal of Open Source Software 3: 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, David M., Andrew Y. Ng, and Michael I. Jordan. 2003. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 3: 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Bolce, Louis, and Gerald De Maio. 2002. Our Secularist Democratic Party. In The Public Interest. Washington, DC: National Affairs, Inc., pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bonikowski, Bart, and Paul DiMaggio. 2016. Varieties of American Popular Nationalism. American Sociological Review 81: 949–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, Stephen P., Martin G. Everett, and Jeffrey C. Johnson. 2013. Analyzing Social Networks. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini, Matteo. 2012. The Trap of Intellectual Success: Robert N. Bellah, the American Civil Religion Debate, and the Sociology of Knowledge. Theory and Society 41: 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueggemann, Walter. 1978. The Prophetic Imagination. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carmody, Sean. 2020. ngramr: R Package to Query the Google Ngram Viewer. Available online: https://github.com/seancarmody/ngramr.https://github.com/seancarmody/ngramr (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Chappell, David L. 2004. A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson, James A., and Ronald C. Wimberley. 1978. Who Is Civil Religious? Sociological Analysis 39: 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, John A. 1970. Civil Religion. Sociological Analysis 31: 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, John W. 2019. Why the Covenant Worked: On the Institutional Foundations of the American Civil Religion. Religions 10: 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csárdi, Gábor, and Tamás Nepusz. 2006. The igraph Software Package for Complex Network Research. InterJournal Complex Systems 1695: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson, Leilah. 2019. Civil Religion as Myth, Not History. Religions 10: 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, James A. 1967. Clustering and Structural Balance in Graphs. Human Relations 20: 181–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nooy, Wouter, Andrej Mrvar, and Vladimir Batagelj. 2011. Exploratory Social Network Analysis with Pajek, Revised and Expanded ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria, Philip. 2019. The Invention of Thanksgiving: Massacres, Myths, and the Making of the Great November Holiday. The New Yorker. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/11/25/the-invention-of-thanksgiving (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Demerath, Nicholas Jay, and Rhys H. Williams. 1985. Civil Religion in an Uncivil Society. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 480: 154–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesner, Jana. 2015. Words and Networks: How Reliable Are Network Data Constructed From Text Data? In Roles, Trust, and Reputation in Social Media Knowledge Markets: Theory and Methods. Edited by Elisa Bertino and Sorin Adam Matai. New York: Springer, pp. 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Diesner, Jana, and Kathleen M. Carley. 2011. Semantic Networks. In Encyclopedia of Social Networks. Edited by George A. Barnett. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, pp. 767–69. [Google Scholar]

- Domke, David S., and Kevin Coe. 2008. The God Strategy: How Religion Became a Political Weapon in America. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drieger, Philipp. 2013. Semantic Network Analysis as a Method for Visual Text Analysis. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 79: 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Mez, Kristin Kobes. 2020. Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1995. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Translated by Karen E. Fields. New York: The Free Press. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Jason A., and Joseph M. Valenzano, III, eds. 2016. The Rhetoric of American Civil Religion: Symbols, Sinners, and Saints. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Everton, Sean F., and Daniel T. Cunningham. 2020. The Quest for the Gist of Jesus: The Jesus Seminar, Dale Allison, and Improper Linear Models. Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 18: 156–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, Roger, and Jennifer M. McClure. 2017. Reviewing Millions of Books: Charting Cultural and Religious Trends with Google’s Ngram Viewer. In Faithful Measures: New Methods in the Measurement of Religion. Edited by Christopher D. Bader and Roger Finke. New York: New York University Press, pp. 287–316. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Richard Elliott. 2017. The Exodus: How It Happened and Why It Matters. New York: HarperOne. [Google Scholar]

- Fruchterman, Thomas M. J., and Edward M. Reingold. 1991. Graph Drawing by Force-Directed Replacement. Software—Practice and Experience 21: 1129–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardella, Peter. 2014. American Civil Religion: What Americans Hold Sacred. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig, Gail. 1981. The American Civil Religion Debate: A Source for Theory Construction. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 20: 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, Philip S. 2017a. American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, Philip S. 2017b. Why Evangelicals Voted for Trump: A Critical Cultural Sociology. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 5: 338–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, Philip S. 2019. Preface to the Paperback Edition. In American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present, Paperback ed. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, Philip S. 2020. American Babylon: Christianity and Democracy before and after Trump. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Roderick P. 1977. The Political Pulpit. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Mark Anthony, Jean-Philippe Cointet, Philipp Brandt, Newton Key, and Peter Bearman. 2018. The (Protestant) Bible, the (Printed) Sermon, and the Word(s): The Semantic Structure of the Conformist and Dissenting Bible, 1660–1780. Poetics 68: 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Donald C., and Russell B. Richey. 1974. The Civil Religion Debate. In American Civil Religion. Edited by Russell B. Richey and Donald C. Jones. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kamada, Tomihisa, and Satoru Kawai. 1989. An Algorithm for Drawing General Undirected Graphs. Information Processing Letters 31: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1986. I Have a Dream. In A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. Edited by James M. Washington. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, pp. 217–20. First published 1963. [Google Scholar]

- LaHaye, Tim, and Jerry B. Jenkins. 1995. Left Behind. Carol Stream: Tyndale House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey, Hal, and Carole C. Carlson. 1990. The Late Great Planet Earth. New York: Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Charles H. 1974. Civil Rights—Civil Religion: Visible People and Invisible Religion. In American Civil Religion. Edited by Russell B. Richey and Donald C. Jones. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, pp. 211–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lüchau, Peter. 2009. Toward a Contextualized Concept of Civil Religion. Social Compass 56: 371–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Michele F. 2018. From Politics to the Pews: How Partisanship and Political Environment Shape Religious Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, Peter V. 1987. Core Discussion Networks of Americans. American Sociological Review 52: 122–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, Carolyn, and David W. Ingle. 1996. Blood Sacrifice and the Nation: Revisiting Civil Religion. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 64: 767–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, Lilliana. 2018. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, Deirdre. 1995. The Insignificance of Statistical Significance. Scientific American 272: 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, Daniel A., Daniel Ramage, Jason Chuang, Jeffrey Heer, Christopher D. Manning, and Daniel Jurafsky. 2013. Differentiating Language Usage Through Topic Models. Poetics 41: 607–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, Jean-Baptiste, Yuan Kui Shen, Aviva Presser Aiden, Adrian Veres, Matthew K. Gray, Joseph P. Pickett, Dale Hoiberg, Dan Clancy, Peter Norvig, Jon Orwant, and et al. 2011. Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books. Science 331: 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, David D. 2022. The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, John W., and Petko Bogdanov. 2013. Introduction—Topic Models: What They Are and Why They Matter. Poetics 41: 545–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, John M. 2008. Power and Authority in a Postmodern Presidency. In The Prospect of Presidential Rhetoric. Edited by James Arnt Aune and Martin J. Medhurst. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, pp. 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Eduardo. 2016. Where Were Trump’s Votes? Where the Jobs Weren’t. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/13/business/economy/jobs-economy-voters.html (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Putnam, Robert D., and Shaylyn Romney Garrett. 2020. The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Reagan, Ronald. 1982. President’s Proclamation. New York Times, November 21, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Richey, Russell B., and Donald C. Jones, eds. 1974. American Civil Religion. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Ritschel, Chelsea. 2020. Thanksgiving: Why Some Americans Don’t Celebrate the Controversial Holiday. Independent. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/thanksgiving-day-meaning-america-what-b1761971.html (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1997. The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings. Translated by Victor Gourevitch. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rule, Alix, Jean-Philippe Cointet, and Peter S. Bearman. 2015. Lexical Shifts, Substantive Changes, and Continuity in State of the Union Discourse, 1790–2014. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112: 10837–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiller, Robert J. 2019. Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian S. 2003. Moral, Believing Animals: Human Personhood and Culture. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian S., Michael O. Emerson, Sally Gallagher, Paul Kennedy, and David Sikkink. 1998. American Evangelicalism: Embattled and Thriving. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Matthew Avery. 2014. American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism. Cambridge: Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, John G. 2020. They Knew We Were Pilgrims: Plymouth Colony and the Contest for American Liberty. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Danielle. 2019. Trump Vows Not to Change the Name of Thanksgiving Despite Cries From the ‘Radical Left’. Fox News. Available online: https://www.foxnews.com/politics/trump-thanksgiving-name-change-sunrise-florida-rally-liberal-left (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Watts, Duncan J. 1999. Small Worlds: The Dynamics of Networks Between Order and Randomness. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, Duncan J., and Steven H. Strogatz. 1998. Collective Dynamics of ‘Small World’ Networks. Nature 393: 409–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, David. 2016. Civil Religion or Mere Religion? The Debate Over Presidential Religious Rhetoric. In The Rhetoric of American Civil Religion: Symbols, Sinners, and Saints. Edited by Jason A. Edwards and Joseph M. Valenzano, III. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 143–64. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Jana, and Heike Bungert. 2019. The Relevance of the Concept of Civil Religion from a (West) German Perspective. Religions 10: 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, Andrew L., and Samuel L. Perry. 2020. Taking America Back for God. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Andrew L., Samuel L. Perry, and Joseph O. Baker. 2018. Make America Christian Again: Christian Nationalism and Voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election. Sociology of Religion 79: 147–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, John H. 1974. A Historian’s Approach to Civil Religion. In American Civil Religion. Edited by Russell B. Richey and Donald C. Jones. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wimberley, Ronald C. 1976. Testing the Civil Religion Hypothesis. Sociological Analysis 37: 341–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2021. Domains of Diffusion: How Culture and Institutions Travel around the World and with What Consequences. American Journal of Sociology 126: 1389–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Brian Min. 2006. From Empire to Nation-State: Explaining Wars in the Modern World, 1816–2001. American Sociological Review 71: 867–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Yuval Feinstein. 2010. The Rise of the Nation-State across the World, 1816 to 2001. American Sociological Review 75: 764–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuthnow, Robert. 1988a. Divided We Fall: America’s Two Civil Religions. The Christian Century, April 20, 395–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow, Robert. 1988b. The Restructuring of American Religion: Society and Faith Since World War II. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ziliak, Stephen T., and Deirdre N. McCloskey. 2008. The Cult of Statistical Significance. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).