1. Introduction

In its present form, Exodus 12:1–13:16 is dominated by a complex network of legal stipulations devoted to the festival(s) of Pesaḥ and Maṣṣot, as well as the sacrifice of the firstborn. However, even a superficial reading of the text reveals that these stipulations cannot be judged as the work of a single author. Rather, the existence of several repetitions and contradictory statements suggests that we are dealing with a composite text that contains different, and in part competing, literary voices. As a rule of thumb, one can make a basic distinction between priestly and non-priestly portions of the text. While Exod. 12:1–20, 28, 40–51 are unanimously ascribed to P, there is at least a broad consensus that the bulk of material in Exod. 12:21–27, 29–39; 13:1–16 constitutes the non-priestly stratum of the text, which, moreover, betrays an undeniable influence of Deuteronomistic phraseology (see e.g.,

Noth 1988, pp. 65–80;

Gertz 2000, pp. 29–73;

Dozeman 2009, pp. 258–98).

At first glance, the juxtaposition of priestly and non-priestly texts in Exod. 12:1–13:16 seems to call for an explanation along the lines of the Documentary Hypothesis, since it seems to suggest the existence of two formerly independent sources (a priestly and a non-priestly one) that both contained stipulations on Pesaḥ and the festival of Maṣṣot. However, even one of the most prominent advocates of the documentary approach, Julius Wellhausen, observed that the literary evidence in the section in question is far too complex to be explained sufficiently by such a simplistic model (

Wellhausen 1963, pp. 72–75). On the one hand, neither the priestly nor the non-priestly text is literarily consistent, but each seems to comprise various layers. On the other hand, there are several clear interconnections between the priestly and the non-priestly layers which suggest that they react to each other and must therefore be interpreted in conjunction. Thus, the complex literary evidence in Exod. 12:1–13:16 goes beyond the limits of the static documentary approach and points instead to a highly dynamic process of editorial reworking (

Fortschreibung).

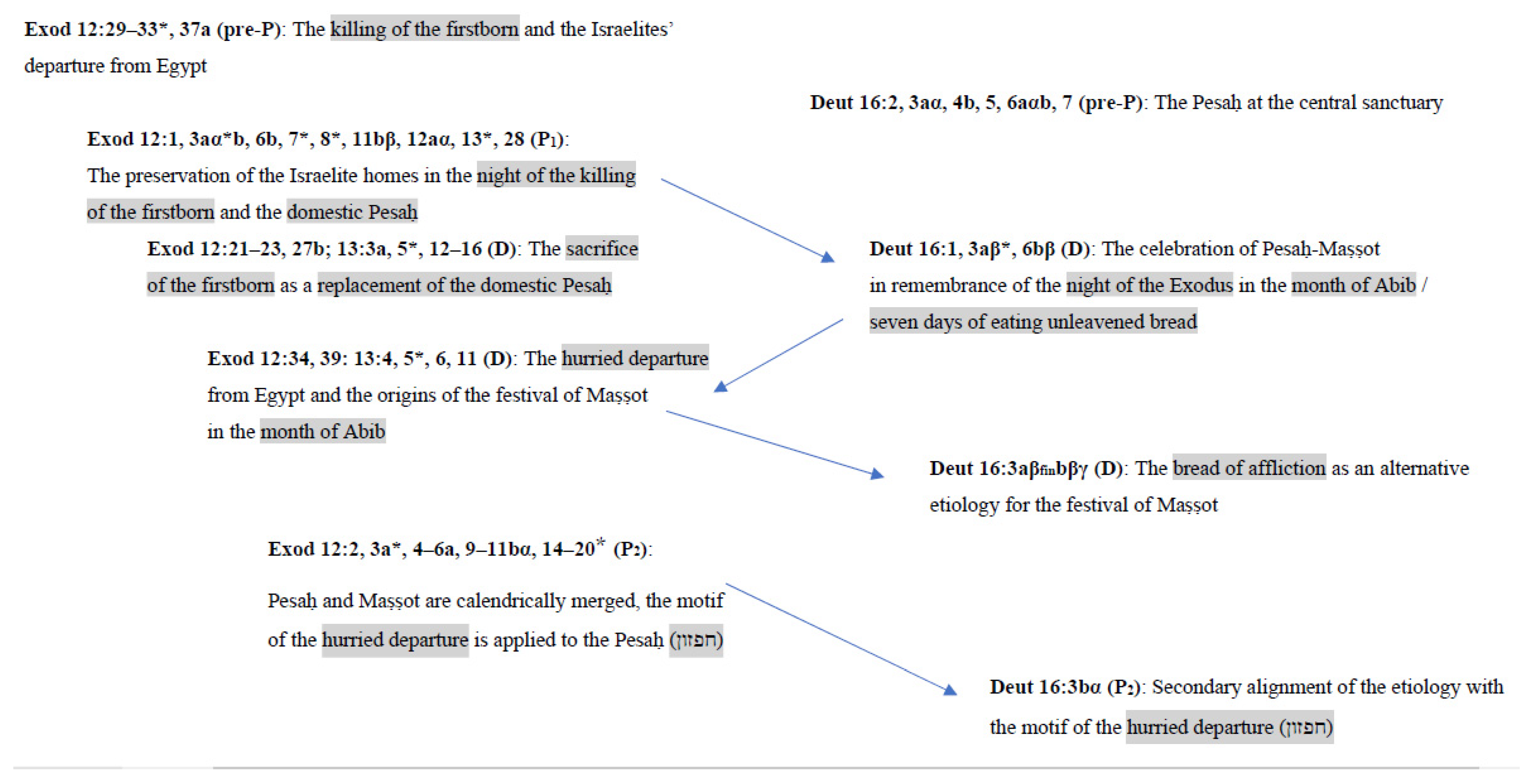

As I will argue in the following analysis, we are in fact dealing with four major stages of development: a pre-priestly core narrative (pre-P), an early priestly editorial stage (P

1), a late Deuteronomistic editorial stage (D), and a late priestly editorial stage (P

2) already post-dating the Holiness legislation from Lev. 17–26. Each stage builds on the preceding ones and thus revises and complements the given form of the festival and sacrificial ordinances. This process of reworking, which at times shows striking similarities to the Midrashic exegesis of later times (

Gesundheit 2012), not only led to a progressive fusion of Pesaḥ and Maṣṣot into a single festival but also spawned a set of etiologies which seek to deduce specific aspects of the festive rites from the Israelites’ situation at the time of the exodus. In what follows, I will focus specifically on the emergence and redactional transformation of these etiologies, which have so far received considerably less attention than the halakhic issues dealt with by most studies. To trace the main lines of the editorial process, I will start with the earliest reconstructable stage, namely, the pre-priestly text. At this particular stage, the text only comprised a brief account on the death of the Egyptian firstborn and the Israelites’ departure without any connection with festive or sacrificial rites.

2. In the Beginning There Were No Festivals: The Pre-Priestly Account of the Death of the Egyptian Firstborn

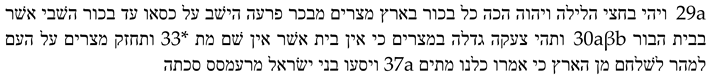

The literary core of Exod. 12:1–13:16, around which all of the legal material has been successively arranged, consists of the following brief pre-priestly narrative in Exod. 12:29a, 30aβb, 33*, 37a (see

Berner 2010, pp. 267–76;

Germany 2017, pp. 52–54).

29a At midnight YHWH struck down all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh who sat on his throne to the firstborn of the prisoner who was in the dungeon. 30aβb And there was a loud cry in Egypt, for there was not a house without someone dead. 33* The Egyptians urged the people to hasten from the land, for they said, “We shall all be dead.” 37a And the Israelites journeyed from Rameses in the direction of Succoth.

The pre-priestly text marks the conclusion of the plague narrative and prepares for the account of the miracle at the sea (Exod. 14:5–30*), which originally formed the immediate conclusion of the itinerary notice in 12:37a. Despite previous attempts to claim at least parts of the non-priestly stipulations on the Pesaḥ (12:21–27) or the festival of Maṣṣot (12:34, 39; 13:3–10) for the same pre-priestly level, there is compelling evidence that both passages belong to later editorial layers of the text. As I will argue below in

Section 4 and

Section 5, they are part of the late Deuteronomistic stage (D) and thus already presuppose the early priestly text in 12:1–13*, 28 (P

1). As a result, it was the early priestly layer which introduced the first festival stipulations into the context of the exodus narrative.

3. An Apotropaic Blood Rite and a Domestic Sacrificial Meal: The Pesaḥ in the Early Priestly Text

There is a strong scholarly consensus that the earliest priestly text only referred to the Pesaḥ (Exod. 12:1–13, 28), while the passage on the festival of Maṣṣot (12:14–20) represents a secondary appendix (

Laaf 1970, pp. 109–10;

Albertz 2012, p. 190). However, Exod. 12:1–13 cannot be ascribed to P

1 in its entirety, but also shows clear traces of literary growth that calls for further redaction-critical differentiation. The main criterion for separating the original core of the Pesaḥ stipulations (P

1) from its later expansions is the repeated shift between the second- and third-person plural. As can easily be demonstrated, the passages formulated in the third-person plural provide the literary scaffolding of the section, into which the phrases employing the second-person plural were later inserted. Based on this basic distinction, Exod. 12:1, 3aα*b, 6b, 7*, 8*, 11bβ, 12aα, 13* emerge as the earliest layer of the priestly Pesaḥ stipulations (P

1) (

Weimar 1995;

Berner 2010, pp. 278–93).

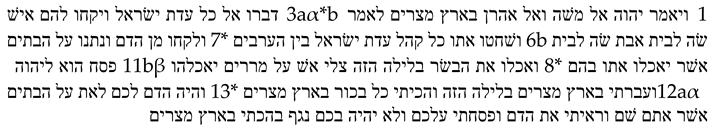

1 And YHWH said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt: 3aα*b Tell the whole congregation of Israel that they shall take a lamb for each family, a lamb for each household. 6b And they shall slaughter it at twilight 7* and shall take some of the blood and put it on the houses in which they eat it. 8* They shall eat the flesh that same night; they shall eat it roasted over the fire with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. 11bβ It is a Pesaḥ for YHWH. 12aα And I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and I will strike down every firstborn in the land of Egypt. 13* Then the blood shall be a sign for you on the houses where you live: when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and no plague shall hit you when I strike the land of Egypt.

The Pesaḥ stipulations in Exod. 12:1–13* (P

1) represent the earliest reference to this festival in the book of Exodus. The text can be divided into two parts. While the first part in Exod. 12:1–11* prescribes the slaughtering of a lamb, the performance of an apotropaic rite with the blood of the animal as well as a sacrificial meal, the second part in Exod. 12:12–13* establishes an etiological connection between the ritual performance and the final plague: the blood smeared on the houses of the Israelites serves as a sign for YHWH that allows him to identify the dwelling places of his people and thus spare their firstborn. However, the connection between the two parts of the text is not only realized on a thematic level but also on a lexical level. While part one concludes in Exod. 12:11bβ with the identification of the sacrificial rite as “a Pesaḥ for YHWH” (פסח הוא ליהוה), the author purposefully picks up the root פסח at the conclusion of the second part (Exod. 12:13: “I will pass over you”) and thus indicates an organic connection between the ritual and the exemption of the Israelites’ houses from YHWH’s subsequent destructive action (on the etymology of the term פסח see, e.g.,

Laaf 1970, pp. 142–47;

Otto 1996, pp. 659–82). According to the early priestly view, the Pesaḥ is thus celebrated in remembrance of the fact that YHWH had spared his people when killing the firstborn of Egypt.

Since the priestly Pesaḥ etiology is explicitly tied to the killing of the Egyptian firstborn announced in Exod. 12:12–13*, it is all the more striking that P

1 lacks an account of this decisive event. Instead, only the execution of the ritual prescriptions from Exod. 12:1–11* is briefly recounted in Exod. 12:28 P

1. This peculiar gap in the priestly text underscores that the priestly author has not created an independent account but has supplemented the pre-priestly core narrative (Exod. 12:29–33*) with his etiology of the Pesaḥ (

Van Seters 1994;

Kratz 2000, p. 244;

Berner 2010, pp. 278–93;

Albertz 2012, pp. 197–202;

Utzschneider and Oswald 2013, pp. 280–85; differently, e.g.,

Gertz 2000, pp. 87–88). The reference to the Egyptian houses in Exod. 12:30b (pre-P) could be used as a link to introduce the priestly concept of Pesaḥ as a domestic celebration in the Israelites’ homes, which was in turn connected with the plague narrative through the apotropaic blood rite. While the priestly concept of Pesaḥ seems to reflect the situation of diaspora communities in early post-exilic times (

Albertz 2012, pp. 206–9), it also contains an open contradiction to the festival calendar in Deut. 16, according to which the Pesaḥ represents one of the three annual pilgrimage festivals and is thus inseparably tied to the central sanctuary (see below,

Section 8). It is therefore not surprising that the earliest Pesaḥ etiology in Exod. 12:1–13*, 28 (P

1) triggered a response by late Deuteronomistic circles (D).

4. A One-Time Event: The Late Deuteronomistic Rejection of the Priestly Etiology of a Domestic Pesaḥ

While the non-priestly origin of the Pesaḥ stipulations in Exod. 12:21–27 is not called into question, the literary relationship between the respective passage and the priestly text remains a much-debated issue. Although some scholars ascribe the text to the pre-priestly stratum of Exod. 12 (

Utzschneider and Oswald 2013, pp. 280–85;

Jeon 2013, pp. 159–67), there is no compelling evidence to support this view. On the contrary, there are several strong arguments which suggest that Exod. 12:21–27 in fact represents a post-priestly addition that has been inserted purposefully into the framework of the earlier priestly Pesaḥ stipulations in Exod. 12:1–13*, 28 (P

1) (

Berner 2010, pp. 286–93;

Albertz 2012, pp. 197–202; cf. already

Wellhausen 1963, p. 75). To begin with, Moses’ command to slaughter “the Pesaḥ” in Exod. 12:21 evidently presupposes the introduction of the term “Pesaḥ” in Exod. 12:11bβ (P

1). Moreover, the announcement of YHWH striking the Egyptians in Exod. 12:23 fails to mention one decisive detail, namely, that the action will be directed against the Egyptian firstborn. Again, the earlier announcement from the priestly text (Exod. 12:13 P

1) is evidently presupposed. Yet, while some basic elements of the priestly text were deemed unnecessary to be repeated in Exod. 12:21–27, the text at the same time provides a more elaborate account of certain details. Thus, it specifies the performance of the apotropaic blood rite and introduces the mediating figure of “the destroyer” who executes the divine judgment against the Egyptians (

Norin 1977, pp. 175–76). This tendency toward expanding on certain details from the priestly text is another piece of evidence which supports the idea that Exod. 12:21–27 should be regarded as a post-priestly insertion.

The post-priestly origin of Exod. 12:21–27 is further supported by the fact that, in its reference to the elders and its portrayal of the people’s pious reaction, the text shows close ties to the late Deuteronomistic portions of Moses’ call story (Exod. 3:18; 4:29b, 31 D). Therefore, Exod. 12:21–27 should also be assigned to the same editorial stage (D). However, this applies only to the earliest literary stratum of the passage, which has apparently been reworked by later hands. The most obvious trace of this editorial process is the fact that the reaction of the people in Exod. 12:27b appears to be out of place. Their bowing down and worshipping makes little sense after the directions in Exod. 12:24–27a, which prescribe the observance of the rite of Pesaḥ after entering the promised land and which order the instruction of the children on the rite’s meaning. Rather, Exod. 12:27b connects smoothly to the announcement of divine deliverance in Exod. 12:23 and reports the people’s spontaneous reaction. As a result, only Exod. 12:21–23, 27b constitute the original late Deuteronomistic stratum, while Exod. 12:24, 25–27a were only subsequently added to the text (

Noth 1988, p. 76;

Gertz 2000, pp. 72–73; differently, e.g.,

Gesundheit 2012, pp. 66–67).

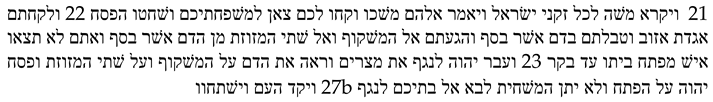

21 Then Moses called all the elders of Israel and said to them, “Go, select lambs for your families, and slaughter the Pesaḥ. 22 Take a bunch of hyssop, dip it in the blood that is in the basin, and touch the lintel and the two doorposts with the blood in the basin. None of you shall go outside the door of your house until morning. 23 For YHWH will pass through to strike down the Egyptians; when he sees the blood on the lintel and on the two doorposts, YHWH will pass over that door and will not allow the destroyer to enter your houses to strike you down.” 27b And the people bowed down and worshiped.

By placing Exod. 12:21–23, 27b in the framework of the priestly text (Exod. 12:1–13*, 28 P1), the late Deuteronomistic editor created the impression that Moses now communicates the previous Pesaḥ stipulations to the elders. However, a closer look reveals that the interpolation provides anything but a verbatim repetition of the priestly text. In contrast to Exod. 12:1–13* (P1), Exod. 12:21–23 (D) focuses exclusively on the apotropaic blood rite, which is described in considerably more detail. At the same time, all references to the Pesaḥ meal are purposefully omitted. In this way, the late Deuteronomistic editor rejects the main idea of the early priestly Pesaḥ etiology, namely, that the preservation of the Israelite homes on the night of the killing of the firstborn established the annual practice of a domestic Pesaḥ meal. As already indicated above, the reasons for this rejection of the priestly concept lie with its incompatibility with the festival calendar of Deut. 16, where the Pesaḥ is presented as a pilgrimage feast tied to the central sanctuary. According to the Deuteronomistic view, a domestic celebration of the Pesaḥ was illegitimate, which is why the late Deuteronomistic author of Exod. 12:21–23, 27b revoked the early priestly Pesaḥ etiology from Exod. 12:1–13*. According to his reading, the Pesaḥ sacrifice in Egypt was a one-time event that served the single purpose of performing the apotropaic blood rite and thus facilitated the preservation of the Israelite homes. It does, therefore, not establish a continuous festival practice, but it is instead subsumed among YHWH’s salvific deeds on behalf of his people. It is precisely this latter aspect which is highlighted by the pious reaction of the Israelites in Exod. 12:27b (cf. Exod. 4:31 D).

To sum up, the main purpose of the late Deuteronomistic interpolation in Exod. 12:21, 23, 27b is to reject the early priestly festival etiology, which derives the domestic Pesaḥ meal from the preservation of the Israelites’ homes during the night of the killing of the firstborn. However, a closer look at the continuation of the late Deuteronomistic layer in Exod. 13 shows that the editor did not content himself with rejecting the priestly concept but, in fact, replaced it with a positive alternative. According to this view, the final plague no longer offered the etiological foundation for the Pesaḥ but is instead connected with the sacrifice of the firstborn.

5. Redefining the Etiological Link: The Late Deuteronomistic Connection between the Final Plague and the Sacrifice of the Firstborn

The late Deuteronomistic passage Exod. 13:3–16 contains a long speech of Moses, which can be divided into two different thematic parts (

Gertz 2000, p. 67;

Zahn 2004, pp. 36–55;

Albertz 2012, pp. 201–2). While the first part in Exod. 13:3–10 is devoted to the festival of Maṣṣot, the second part in Exod. 13:11–16 deals with the sacrifice of the firstborn. However, tensions in the introductory verses of the speech (Exod. 13:3–5) show that the connection between the two parts is not original but was only created gradually through the editorial expansion of a core text. In contrast to what one might assume at first glance, this literary core did not consist of the first section on the festival of Maṣṣot, but rather of the second section on the sacrifice of the firstborn. The following three observations support this claim. Firstly, Exod. 13:3a employs a unique exodus formula (lit. “by strength of hand”) which is taken up again in the final verse of the catechesis concluding the second part (Exod. 13:16). Secondly, Exod. 13:3a refers to the exodus in retrospect (“YHWH brought you out”), whereas Exod. 13:4 abruptly introduces the month of Abib as the time of the exodus, which is apparently still perceived as an unfinished process (“today, in the month of Abib, you are going out”). Since the two perspectives contradict each other and Exod. 13:4 is literarily dependent on the introduction of the speech in Exod. 13:3a, the only possible explanation is that Exod. 13:4 is a later interpolation (

Levin 1993, p. 339;

Gesundheit 2012, pp. 212–16).

This coincides with a third observation related to Exod. 13:5. While the present form of the verse explicitly repeats the reference to the exodus in the month of Abib from Exod. 13:4 and thus prepares for the stipulations concerning the festival of Maṣṣot in Exod. 13:6–10, it is also apparent that the specific terminology employed in Exod. 13:5 lacks a genuine connection with this festival. Rather, the command “to observe this practice” (ועבדת את העבדה הזאת) suggests a ritual point of reference (

Gesundheit 2012, p. 208) and therefore fits much better with the sacrifice of the firstborn than with the custom of eating unleavened bread. In sum, the overall evidence clearly suggests that the introduction of the Mosaic speech in Exod. 13:3a, 5* originally prepared for the stipulations concerning the sacrifice of the firstborn in Exod. 13:12–16, while the passages relating to the festival of Maṣṣot (Exod. 13:3b, 4, 5*, 6–10, together with the transitional verse Exod. 13:11) were added by a later hand. For reasons of clarity, both stages of development are presented together here:

[13:7–10: Additional stipulations concerning the festival of Maṣṣot]

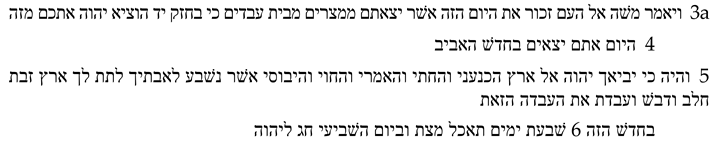

3a Moses said to the people, “Remember this day on which you came out of Egypt, out of the house of slavery, because YHWH brought you out from there by strength of hand.

4 Today, in the month of Abib, you are going out.

5 When YHWH brings you into the land of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites, which he swore to your ancestors to give you, a land flowing with milk and honey, you shall observe this practice

in this month. 6 Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread, and on the seventh day there shall be a festival to YHWH.

[13:7–10: Additional stipulations concerning the festival of Maṣṣot]

11 “When YHWH has brought you into the land of the Canaanites, as he swore to you and your ancestors, and has given it to you,

12 you shall set apart to YHWH all that first opens the womb. All the firstborn of your livestock that are males shall be YHWH’s. 13 But every firstborn donkey you shall redeem with a sheep; if you do not redeem it, you must break its neck. Every firstborn male among your children you shall redeem. 14 When in the future your child asks you, ‘What does this mean?’ you shall answer, ‘By strength of hand YHWH brought us out of Egypt, from the house of slavery. 15 When Pharaoh stubbornly refused to let us go, YHWH killed all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, from human firstborn to the firstborn of animals. Therefore, I sacrifice to YHWH every male that first opens the womb, but every firstborn of my sons I redeem.’ 16 It shall serve as a sign on your hand and as an emblem on your forehead that by strength of hand YHWH brought us out of Egypt.”

Several observations show that the section in Exod. 13:3a, 5*, 12–16 (D) is strongly influenced by Deuteronomistic thought. While already the introductory reference to the inhabitants of the land points to a Deuteronomistic milieu (cf., e.g., Exod. 3:8, 17; 23:23; 34:11; Deut. 7:1; 20:17; Josh 3:10), the concluding catechesis in Exod. 13:14–16 even seems to be based on a specific literary Vorlage (see

Gertz 2000, pp. 57–61;

Berner 2010, pp. 314–16). It combines the key elements of the catechesis from Deut. 6:20–24 with the motif of carrying the words of the law as a sign and emblem on one’s hand and between one’s eyes (Deut. 6:8), which the author of Exod. 13:16 no longer employs in a literal, but in a spiritualized sense: the observance of the commandment to sacrifice all male firstborn, but to redeem every human firstborn with an animal, shall be like a sign and an emblem that recalls YHWH’s killing of every firstborn in the land of Egypt to bring about the exodus of his people. While the obligation to sacrifice all male firstborn animals is also expressed in Deut. 15:19, the Deuteronomic law code makes no reference to the treatment of firstborn sons. The explicit exclusion of the human firstborn, which repeals the commandment from Exod. 22:28b, seems to be a genuine innovation of the late Deuteronomistic author of Exod. 13:12–16, which is essentially connected to the etiological reference point. When killing all firstborn in the land of Egypt, YHWH articulated his unequivocal claim for every firstborn, animals and humans alike. At the same time, the exemption of the Israelite sons seems to serve as a precedent for the exceptional treatment of the male firstborn, namely, their redemption through an animal sacrifice.

The above observations suggest that the first late Deuteronomistic editor has radically reinterpreted the account of the killing of the Egyptian firstborn and the preservation of the Israelite homes. He not only rejected the priestly Pesaḥ etiology by reducing the Egyptian Pesaḥ to an apotropaic blood rite without a domestic meal (Exod. 12:21–23, 27b D) but also replaced it with an alternative etiology that seeks to establish the sacrifice of the firstborn (Exod. 13:3a, 5*, 12–16 D). At this particular stage of the literary development of Exod. 12–13, the text contained no festival etiology whatsoever, since the priestly Pesaḥ etiology had been suppressed and the festival of Maṣṣot was not yet in view. The latter festival would only be introduced at a later stage of the late Deuteronomistic text, which will be dealt with in the following section.

6. Remembering the Hurried Departure from Egypt: The Late Deuteronomistic Etiology of the Festival of Maṣṣot

As argued in the previous section, Moses’ speech in Exod. 13:3a, 5* originally introduced the stipulations concerning the sacrifice of the firstborn in Exod. 13:12–16 and was only connected with the festival of Maṣṣot at a later editorial stage of the text. The late Deuteronomistic editor who reworked the speech accordingly added the reference to the month of Abib in Exod. 13:4, as well as the corresponding section at the end of Exod. 13:5 (“in this month”). By means of these additions, the command to “observe this practice” (Exod. 13:5*) is detached from its original reference point, i.e., the sacrifice of the firstborn (Exod. 13:12–16). In its expanded form, Exod. 13:5 now serves as an introduction to the new injunction in Exod. 13:6, which was added by the same hand: “Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread, and on the seventh day there shall be a festival to YHWH.”

While the custom of eating unleavened bread for a period of seven days (Exod. 13:6a) is a common element attested in all festival calendars of the Hebrew Bible (Exod. 23:15; Deut. 16:3a; Lev. 23:6; Num. 28:17), only Exod. 13:6 prescribes the celebration of a pilgrimage festival (חג) on the seventh day. The latter aspect seems to be a genuine innovation of the late Deuteronomistic Maṣṣot etiology in Exod. 13:4, 5*, 6, which thus differentiates between the period of eating unleavened bread (seven days) and the time spent at the central sanctuary (the seventh day). Interestingly, the course of events envisaged in the festival calendar of Deuteronomy (Deut. 16:1–7*), where only the first day of the Maṣṣot week is to be spent at the central sanctuary (

Gesundheit 2012, pp. 133–36), is thus turned upside down (On the relationship between Exod. 13 and Deut. 16, see

Section 8 below).

This notable reversal of the course of events may reflect (and perhaps, at least in part, be caused by) the narrative logic of the Maṣṣot etiology in Exod. 13. According to Exod. 13:3a, 4–6 (D), the Israelites are about to depart from Egypt when they receive the instruction that, after the conquest of the land, they are to commemorate the situation of the exodus by eating unleavened bread. Thus, the distinction between the first six days of the Maṣṣot week and the temple festival on the seventh day allows future generations to recollect more easily that the Israelites were still on the move when they were forced to eat unleavened bread. The respective situation is illustrated in Exod. 12:34, 39. These verses narrate that the Israelites, having to leave Egypt in haste, carried their unleavened dough with them, which they baked into cakes of unleavened bread after pitching camp at Succoth (Exod. 12:37a). Exod. 12:34, 39 provide the narrative basis for the Maṣṣot etiology in Exod. 13:3a, 4–6 and therefore represent an indispensable element of the same late Deuteronomistic layer.

In contrast to the etiologies of the Pesaḥ (Exod. 12:1–13* P1) and the sacrifice of the firstborn (Exod. 13:12–16 D), the Maṣṣot etiology betrays a new logic, since it is no longer connected to the killing of the firstborn and the preservation of the Israelite homes. Rather, the custom of eating unleavened bread is derived from a historical coincidence, namely, that the Israelites’ hurried departure from Egypt did not leave sufficient time for the dough to leaven. Therefore, the respective custom does not commemorate YHWH’s decisive intervention on behalf of his people, but rather the experience of hastily leaving the country of oppression. It was only through the hand of later editors that this unique feature of the late Deuteronomistic Maṣṣot etiology would be incorporated within the Pesaḥ etiology and that the custom of eating unleavened bread would be explicitly connected with an act of divine deliverance. This development must be seen in the larger context of a progressive amalgamation of the two formerly independent festivals that is reflected in the late priestly portions of Exod. 12–13, which will be discussed in the following section.

7. Toward a Single Celebration: The Merging of Pesaḥ and Maṣṣot in the Late Priestly Portions of Exodus 12–13

By complementing the early priestly passage on the Pesaḥ (Exod. 12:1–13* P1) with the first etiology of the festival of Maṣṣot (Exod. 12:34, 39; 13:3a, 4, 5, 6 D), the late Deuteronomistic editor created a textual sequence in which both festivals were connected for the first time in the literary history of Exod. 12–13. However, it is crucial to bear in mind that, at this stage of development, there was still no organic connection between the two festivals. On the contrary, the late Deuteronomistic editors claimed that the domestic celebration of the Pesaḥ advocated by P1 was a one-time event (Exod. 12:21–23, 27b D) and should, unlike the festival of Maṣṣot (Exod. 13:3a, 4, 5, 6 D), not be repeated after the conquest of the land. However, in the long term, this distinct late Deuteronomistic position concerning Pesaḥ and Maṣṣot would not prevail. It was suppressed in the process of an extensive reworking of the text through late priestly editors (P2), who not only reenacted the early priestly Pesaḥ etiology but also merged the two festivals into a single celebration.

One of the key elements of the late priestly reworking of the text was the introduction of a comprehensive calendrical system (Exod. 12:2 P

2) that precisely defined the sequence of the events. While the late Deuteronomistic text only provided the vague reference to the month of Abib as the time of the Israelites’ exodus (Exod. 13:4 D), the late priestly editors provided an exact set of dates in the first month that include both the Pesaḥ and the seven days of eating unleavened bread. The sequence starts with the singling out of the sacrificial animal on the tenth day (Exod. 12:3aβb P

2), continues with the sacrifice and the domestic meal on the fourteenth day (Exod. 12:6a P

2), and ends with the eating of unleavened bread until the twenty-first day (Exod. 12:18 P

2). While the overall timeframe from the fourteenth to the twenty-first day as well as the specific obligations connected with the seven-day period of eating unleavened bread are fully congruent with the festival calendar in Lev. 23 and have obviously been derived from there (

Nihan 2007, pp. 564–65), the late priestly editors of Exod. 12 nevertheless deviated from their literary

Vorlage in one important aspect. In contrast to Lev. 23:5–6, where the Pesaḥ sacrifice on the fourteenth day and the beginning of the Maṣṣot week on the fifteenth day are consecutive but distinct events, the late priestly editors of Exod. 12 gave up this distinction and merged the two festivals into one celebration. Now, the period of eating unleavened bread already commences on the eve of Pesaḥ, i.e., on the fourteenth day (Exod. 12:18 P

2).

The far-reaching fusion of the two formerly independent festivals in the late priestly portions of Exod. 12 has not only affected the chronology, but it has also given rise to a completely new etiological foundation of the events. While the late Deuteronomistic author of Exod. 12:34, 39; 13:3a, 4–6 (D) had derived the custom of eating unleavened bread from the Israelites’ hurried departure from Egypt, it is now brought into connection with the remembrance of “this day”, i.e., the time of the killing of the firstborn on the fourteenth day of the first month (Exod. 12:14, 17 P

2). In this way, the observation of the festival of Maṣṣot is etiologically linked with the time and events that were originally connected with Pesaḥ in the early priestly portions of the text (Exod. 12:1–13* P

1). Conversely, the late priestly editors have created a new Pesaḥ etiology which is based on the key motif of the late Deuteronomistic etiology of the festival of Maṣṣot, namely, the hurried departure from Egypt (see

Van Seters 1994, p. 109). In another play on words with the term פסח, Exod. 12:11abα, P

2 orders that the Israelites shall consume the Pesaḥ meal “in great haste” (בחפזון) and fully equipped for travel (

Jacob 1997, p. 319). Thus, the creation of this artificial etiology gives another example of the effort the late priestly editors made to merge the festivals of Pesaḥ and Maṣṣot as organically as possible.

The observations made so far only illuminate the basic lines of development in the complex redaction history of Exod. 12–13. They thus provide a first impression of the highly dynamic and creative evolution of the legal material in Exod. 12–13 and the different attempts to establish an etiological connection with the events recounted in the exodus narrative. However, the repercussions of this redactional process are not limited to the immediate context of Exod. 12–13 but can also be traced in the festival calendars of Exod. 23 and Deut. 16, which will be discussed briefly in the final section of this article.

8. Editorial Links between Exod. 12–13 and the Festival Calendars in Exodus 23 and Deuteronomy 16

Among the festival calendars of the Hebrew Bible, the version contained in the Covenant Code (Exod. 23:14–19) is not only the briefest but also the earliest one (

Levinson 1997, pp. 53–97). Exod. 23:14–16 forms the core of the calendar which consists of a superscription and a successive list of the three annual pilgrimage festivals. The original pattern of the list is still fully preserved in Exod. 23:16, where the second and the third festival are dealt with. By contrast, Exod. 23:15 not only provides a much more elaborate description of the first festival (Maṣṣot), but in so doing also breaks the syntactic structure of the list by disconnecting its continuation in Exod. 23:16. Apparently, Exod. 23:15 has received later editorial expansions that disturbed the original structure of the festival calendar. In the following presentation of the text, the editorial portions have been indented.

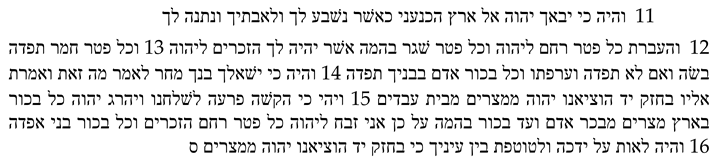

14 Three times in the year you shall hold a festival for me: 15 [You shall observe] the festival of Maṣṣot

as I commanded you, you shall eat unleavened bread for seven days

at the time of the new light [in the month] of Abib,

for in it you came out of Egypt. No one shall appear before me empty-handed.

16 And the festival of harvest, of the first fruits of your labor, of what you sow in the field. And the festival of ingathering at the end of the year, when you gather in from the field the fruit of your labor.

The redaction-critical analysis of the text shows that the original version of the festival calendar contained no reference to the liberation from Egypt or any other event. The etiological connection between the time of the festival of Maṣṣot and the exodus was only established by a later redactor, who no longer understood (or cared for) the original astronomical meaning of the phrase למועד חדש האביב (“at the time of the new light of Abib”) (see

Auerbach 1958, p. 7) and took it as a general reference to the month of the exodus. The development is closely reminiscent of the late Deuteronomistic Maṣṣot etiology in Exod. 13:3a, 4–6 (D), where the term חדשׁ has also lost its precise astronomical connotation and is employed to denote the month of Abib in a rather unspecific manner. However, not only do both texts share a similar tendency, but they also seem to be explicitly connected on a literary level. In Exod. 23:15a, the secondary instruction of eating unleavened bread for a period of seven days is introduced by an explicit reference to a preceding divine command, which can only refer to the late Deuteronomistic Maṣṣot etiology from Exod. 13. Thus, it becomes apparent that the editor who expanded the section on the festival of Maṣṣot in Exod. 23:15a was already inspired by Exod. 13:3a, 4–6 (D). Both the etiological connection of the festival with the exodus and the reference to the seven-day period are based on Exod. 13:4, 6 and have been transferred from there into the Covenant Code’s festival calendar.

A comparable tendency toward a secondary historicization of the festival of Maṣṣot is also characteristic of Deuteronomy’s festival calendar in Deut. 16:1–8. However, the situation here is more difficult, since the editorial history of the text is considerably more complex. Apparently, the earliest version of the text referred to the Pesaḥ alone, whereas the portions dealing with the festival of Maṣṣot and establishing an etiological link with the exodus are the result of a successive editorial expansion. The following reconstruction is based in large part on the excellent observations of Shimon Gesundheit (

Gesundheit 2012, pp. 97–149; differently, e.g.,

Gertz 1996;

Veijola 2000;

Kratz 2022).

![Religions 14 00605 i007]()

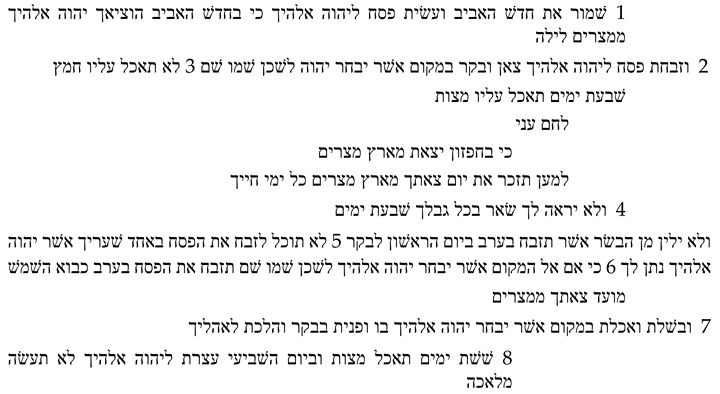

1 Observe the month of Abib by keeping the Pesaḥ for YHWH your God, for in the month of Abib YHWH your God brought you out of Egypt by night.

2 You shall offer the Pesaḥ sacrifice for YHWH your God, from the flock and the herd, at the place that YHWH will choose as a dwelling for his name. 3 You must not eat with it anything leavened.

For seven days you shall eat unleavened bread with it

—the bread of affliction—

because you came out of the land of Egypt in great haste,

so that all the days of your life you may remember the day of your departure from the land of Egypt.

4 No leaven shall be seen with you in all your territory for seven days;

and none of the meat of what you slaughter on the evening of the first day shall remain until morning. 5 You are not permitted to offer the Pesaḥ sacrifice within any of your towns that YHWH your God is giving you. 6 But at the place that YHWH your God will choose as a dwelling for his name, only there shall you offer the Pesaḥ sacrifice, in the evening at sunset,

the time of day when you departed from Egypt.

7 You shall cook it and eat it at the place that YHWH your God will choose; the next morning you may go back to your tents.

8 For six days you shall continue to eat unleavened bread,

and on the seventh day there shall be a solemn assembly

for YHWH your God, when you shall do no work.

According to the above reconstruction, the earliest literary layer of the text consisted of Deut. 16:2, 3aα, 4b, 5, 6aαb, 7. The text introduced the Pesaḥ as a sacrifice at the central sanctuary but did not refer to the festival of Maṣṣot or provide any link to the exodus. Both aspects are only attested in the secondary portions of the text and were apparently introduced in a gradual process of successive expansions. Moreover, the different stages of this process are correlated with the literary development of Exod. 12–13, which further complicates the redaction-critical reconstruction (see

Figure 1). To begin with, there is an obvious connection between the references to the Israelites’ exodus at night in Deut. 16:1, 6bβ and the early priestly Pesaḥ etiology in Exod. 12:1–13*, 28 (P

1). This is most easily explained by assuming that Deut. 16:1, 6bβ already presuppose the early priestly text, where the connection between the Pesaḥ and the exodus was established for the first time. If this assumption is correct, Deut. 16:1, 6bβ should be seen in conjunction with the late Deuteronomistic addition in Exod. 12:21–21, 27b (D). As argued above, the latter verses represent a critical reaction to the early priestly text and revoke its attempt to establish the custom of a domestic celebration of the Pesaḥ. Against this background, Deut. 16:1, 6bβ create an analogous etiology for the celebration of the Pesaḥ at the central sanctuary, which only adopts the general motif of the nighttime departure, whereas the specific ritual elements of the early priestly text, i.e., the blood rite and the domestic meal, are consequently dismissed.

At the same time, one must not overlook that Deut. 16:1 is not focused on the Pesaḥ alone. The introductory words of the verse (“observe the month of Abib”) obviously rephrase the command from Exod. 23:15* (“You shall observe the festival of Maṣṣot at the time of the new light of Abib”), which is why Deut. 16:1 introduces a comprehensive perspective on Pesaḥ and Maṣṣot. As Shimon Gesundheit puts it,

“the imperative ‘Keep the month of Abib’ appears to constitute a blanket instruction, totally devoid of any specific content. It functions only to bring several different matters under one rubric. One cannot, it seems, understand the editor’s intention in such a general formulation without the rest of the paragraph […], in which the Pesaḥ and the unleavened bread are combined.”

Conversely, this implies that the editor who formulated the etiological references to the nighttime departure from Egypt (Deut. 16:1, 6bβ) either presupposes or is himself responsible for the addition of the secondary reference to the eating of unleavened bread in Deut. 16:3aβ*. Most notably, this earliest reference to the festival of Maṣṣot in the context of Deut. 16 was still lacking an explicit etiological connection. Instead, the custom of eating unleavened bread is introduced on a purely halakhic level. Using the prohibition from Deut. 16:3aα (“you must not eat with it anything leavened”) as a thematic link, the editor supplied Deut. 16:3aβ* as a complementary request (“for seven days you shall eat unleavened bread with it”). To sum up, it is possible to reconstruct a first editorial stage in the development of Deut. 16 which comprised a combined perspective on both festivals and a specific etiological connection of the Pesaḥ with the nighttime departure from Egypt. While the editor was already familiar with the early priestly Pesaḥ etiology from Exod. 12:1–13*, 28 (P

1), there is no evidence to suggest that he was also aware of the late Deuteronomistic Maṣṣot etiology from Exod. 13:3a, 4–6 (D). Rather, it seems that the author of the latter etiology is dependent on Deut. 16:3aβ*, since this verse provides a plausible basis for the more detailed instructions concerning the seven days of eating unleavened bread in Exod. 13:6 (see

Section 6 above).

The complex network of editorial links running back and forth between Exod. 12–13 and Deut. 16 (reminiscent of the “boomerang effect” described by

Zakovitch 1996) continues with the addition of the Maṣṣot etiology in Deut. 16:3aβ

fin[לחם עני]bβγ. It adopts the specific motif of remembering the day of the exodus from Exod. 13:3a, 4 (D) but at the same time defines an entirely new etiological reference point to account for the custom of eating unleavened bread. By introducing the unique term “bread of affliction” as a designation for the

maṣṣot, the author identifies the unleavened bread with the meagre provisions that he assumed the Israelites received in the days of their enslavement in Egypt. According to this view, the custom of eating unleavened bread does not derive from the hurried departure of the Israelites (thus Exod. 12:34, 39; 13:3a, 4–6 D), nor does it have a direct connection with any other exodus event. Instead, the custom serves as an annual reminder of the miserable situation that the Israelite ancestors endured in Egypt (

Gesundheit 2012, pp. 120–24). It is against the background of this negative foil of reliving a tangible aspect of the Egyptian oppression that the Israelites are to remember the day of the exodus which ended that situation once and for all (Deut. 16:3bβγ).

The new etiology for the festival of Maṣṣot introduced in Deut. 16:3aβ

finbβγ is in line with the general tendency of the chapter to highlight the experience of divine liberation from Egyptian oppression as the common basis for Israel’s festive practice (cf. Deut. 16:1, 6bβ, 12). Apparently, the etiology from Exod. 12:34, 39; 13:3a, 4–6 (D), which deduced the custom of eating unleavened bread from a mere coincidence caused by the hurried departure from Egypt, did not fit with this perspective and called for a different solution such as the one provided by Deut. 16:3aβ

fin[לחם עני]bβγ. However, this original editorial logic behind the text did not prevent later editors from introducing the motif of the Israelites leaving Egypt in haste. Deut. 16:3bα marks such a later addition (

Gertz 1996, p. 70), which supplies precisely this motif (“because you came out of the land of Egypt in great haste”). Interestingly, however, the redactor did not refer to the late Deuteronomistic Maṣṣot etiology from Exod. 13 but, instead, employed the specific term “in great haste” (בחפזון) from Exod. 12:11abα (P

2). In other words, the author of Deut. 16:3bα already seems to be familiar with the late priestly editorial stages of Exod. 12, which adopted the motif of the hurried departure from Exod. 12:34, 39 (D) and applied it to the situation of the Pesaḥ meal. Thus, Deut. 16:3bα reflects an even further stage in the same chain of development, reenacting the original logic of the late Deuteronomistic Maṣṣot etiology from Exod. 13 through the use of specific late priestly terminology. As a result, this final example illustrates that the process of mutual redactional alignments between Exod. 12–13 and Deut. 16 was not limited to the late Deuteronomistic stage, but that it continued during the subsequent late priestly stage.