Abstract

The Huayan sutras are important historical references for the Chinese worship of the Rocana Buddha; however, these Huayan sutras provide little help in understanding the worship for the larger Rocana triad (i.e., Rocana Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas) in niche no. 5 at the Feilai Feng complex. The Rocana triad images are primarily linked to the Buddhist texts written by Chinese monks which established the principle for teaching the Huayan ritual during the Tang period. With regard to the iconographic characteristics of the two bodhisattvas of the triad in niche no. 5, the bodhisattva Samantabhadra rides an elephant, while the bodhisattva Manjusri rides a lion. They are associated with Buddhist texts and artistic productions beyond the Huayan school and are possibly related to esoteric Buddhism. Similarly, the crowned Rocana seen in niche no. 5 is likely derived from an older tradition dating to the Tang and Five Dynasties periods. Similar descriptions can be found in esoteric Buddhist texts and images. Nevertheless, niche no. 5 is the earliest extant example of such a Rocana triad, wherein the triad is represented by a central crowned Buddha with a special hand gesture or mudra, who is flanked by two bodhisattvas riding animals. From niche no. 5, one can see the development of the Huayan Rocana triad within the tenth century. The combination of elements seen in this niche also indicates that Buddhist artists were not limited by the boundaries of different schools or teachings when they created a new form of iconography. The specific iconography of niche no. 5 can be linked to the Han-style Buddhist artistic traditions from previous periods, such as the Tang, Five Dynasties/Wuyue Kingdom. Ultimately, the contemporary Northern Song capital, Kaifeng, was likely the most direct influence. The Rocana Buddhist triad at niche no. 5 is reflected in the iconography of the same triad installed at the Huiyin monastery at a later time during the Northern Song Dynasty. In turn, the similarities between the images in niche no. 5 and those from other regions, such as Sichuan, Yunnan, Korea and Japan, reveal the connection between the Huiyin monastery and these other sites.

1. Introduction

Worship of the Rocana Buddha was mainly associated with the three Huayan (Skt. Avatamsaka, the “Flower Garland”) sutras,1 in which Rocana is the superior Buddha of the dharma bodies (Skt. dharmakaya, Ch. Fashen fo 法身佛) and the dharma realm (Skt. dharmadhatu, Ch. Fajie fo 法界佛, meaning the Buddha of Absolute Reality Realm). Rocana is a commonly used abbreviation for Vairocana, the Sanskrit pronunciation. In early Chinese Buddhist texts, Vairocana was translated as Piluzhena 毗盧遮那 or Lushena 盧舍那.2 However, since the Sui and early Tang period, Chinese monks developed these two Chinese words into two separate religious concepts. 毗盧遮那/Vairocana as the dharma-body; Lushena 盧舍那 as an abbreviation of Piluzhena 毗盧遮那, which indicates the reward-body. The dharma-body is abstract and formless. Meanwhile, many of the Buddha’s images are often inscribed as Lushena 盧舍那.

Rocana lives in a pure land, the Lotus World (Ch. Lianhuazang shijie 蓮華藏世界), which attracted numerous devotional Buddhists. In Rocana’s world, two great bodhisattvas are Manjusri (Ch. Wenshu 文殊), an idealization of wisdom, and Samantabhadra (Ch. Puxian 普賢), famous for keeping his promises. For the purpose of Buddhist practice, monk Dushun 杜順 (d. 640) founded the Huayan school in the Tang period (618–907). After that, the belief of Rocana’s Lotus World flourished in China during the Tang dynasty. As a tradition of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, the worldview of the Huayan school’s teaching is based primarily on the three Avatamsaka Sutras, and the main purpose of the teaching is understanding of the origin of the dharma realm, which is the ultimate reality.

During the Song period (960–1279), Huayan teaching experienced a shift. From the fifth to ninth century, belief in Rocana prospered, not only in practice and Buddhist academia, but also in art. Previously, this prosperity had been unfortunately stifled due to the reign of Emperor Wuzong (r. 841–846). Emperor Wuzong is remembered throughout history for his violent religious persecution of Buddhists. In the fifth year of the Huichang reign (845) of the Tang period, the Huayan school declined. From the end of the tenth century onward, its revival relied on the support from the elites and patronage from the Korean royal family. The Korean royal family patronized the Huiyin Monastery 慧因寺 at Hangzhou in the Zhejiang province, which played a key role in Huayan teachings during that time (Figure 1). From texts, we can see productions of Buddhist art expressing Huayan belief created in the Northern Song capital, Kaifeng (in the present-day Henan province), and in Hangzhou (in the present-day Zhejiang province), the Southern Song (1127–1279) capital. These artistic works from the new era, most of which no longer survive, present meanings and forms that differ from Buddhist art related to Huayan teaching before the tenth century.

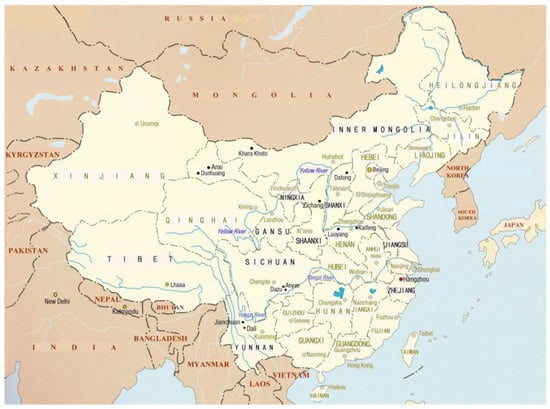

Figure 1.

Map of China with some major Buddhist sites. Drawing by author.

Niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, dated 1022, appears to be the earliest extant Rocana triad to display the key differences in Rocana images by artists after the tenth century. Feilai Feng, the largest extant site of Buddhist art in the Hangzhou area, is notable for its caves and cliff sculptures produced from the tenth century onward in southeast China. More than 200 carvings survive from the Song dynasty, and more than one hundred remain from the Yuan Dynasty.3 From a discussion of niche no. 5, we can understand how Song artists, through their inheritance of traditional forms from the Tang prototypes, created new forms of Rocana images. Niche no. 5 also clarifies the role of the Hangzhou area in Huayan Buddhist art, especially the role of the Huiyin monastery, which was the most important center of Huayan teaching from the eleventh century onward.

Previous scholars discussed the importance of no. 5 in Huayan Buddhist art during the Song. In 1987, Paula Swart wrote a brief article describing several niches from the Song and Yuan periods at Feilai Feng. The first niche she discussed was number 5. Swart noticed the unusual gesture of the Rocana, and his crown, which she thought was probably an esoteric element that had entered the Huayan teaching (). In 1994, Jung Eunwu 鄭恩雨 wrote an article in Korean that introduced Feilai Feng and its images, including niche no. 5. She also paid attention to the mudra of the Rocana figure in number 5, which is similar to that of the Rocana Buddha figures from Dali, Liao kingdom and Southern Song Sichuan (). In 1988, Ishida Hisatoyo 石田尚豐 considered niche no. 5 to be representative of an arrangement and iconography that was popular in the Zhejiang area, influencing paintings of subjects related to the Huayan sutras in Japan during the Kamakura 鐮倉 period (1185–1333) (). Despite these publications, many questions regarding niche no. 5 still have not been resolved, such as why the mudra of the Rocana figure is so different from general Buddhas, how the Rocana inherited the esoteric tradition of wearing a crown, and how the niche influenced Japanese Buddhist art. Examining niche no. 5 can help answer these questions and provide information about the tradition of Rocana triad images and their transmission during the Song period.

The goal of this paper is to use an analysis of the iconography of niche no. 5 to clarify the role of the Huiyin monastery in transmitting Huayan Buddhist art from Hangzhou to other regions. To understand the iconography of niche 5, it is necessary to classify Rocana images. Texts and other artistic works will be used in this analysis. I will also discuss how the artists inherited traditions and carved unique features different from general Buddha figures into niche no. 5. I hope to demonstrate how no. 5 plays an important role in research of the history of Rocana Assembly images.

2. Niche no. 5 and the System of Rocana Images

Niche no. 5, engraved on the east wall of the south entrance of Qinglin cave in approximately 1022, reveals Huayan beliefs through its depiction of a Rocana assembly (Figure 2). The clearly written inscription contains valuable information about the subject, donor, function and the date of the carving. The inscription, carved on the right of niche no. 5, says:

Although the donor, Hu Chengde 胡承德, left nothing in textual records, we know that he must have been a very devoted Buddhist; he commissioned niche no. 5 not for himself or his family or relatives, but on behalf of all sentient beings. He hoped visitors would look upon and pay reverence to these images so that they would be reborn in the Pure Land of the Rocana Buddha. The engraved record reveals Hu’s religious preference for Huayan teaching in this commission.Disciple Hu Chengde 胡承德 reverently commissioned carvers to carve the seventeen figures of Rocana (Lushena 盧舍那) Buddha’s assembly for the four graces (si’en 四恩) [that he received] and [for the behalf of the sentient beings of] the three realms of existence (sanyou 三有). [He] wishes [for] visitors to look upon and revere [them], [and he hopes everyone can be] reborn in the Pure Land together. Recorded on a day in the fourth lunar month of the first year of Qianxing (1022) of the great Song.[弟子胡承德伏為四恩三有, 命石工鐫盧舍那佛會一十七身. 所期來往觀瞻, 同生淨土. 時大宋乾興元年四月日記.]4

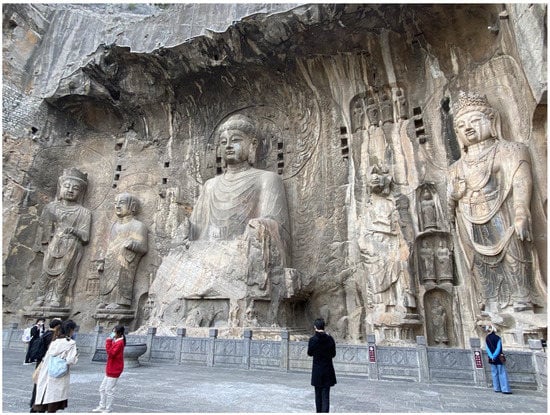

Figure 2.

Rocana Buddha assembly, dated 1022, carved in stone—niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng Grottoes, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. Photo by author.

The number and the main subject of the images in niche no. 5 correspond exactly to its inscription, but the niche itself presents viewers with additional information through the hierarchical arrangement and the identity of each figure. The inscription mentions the subject: seventeen figures of Rocana Buddha’s assembly. In the center of the niche is a Rocana triad surrounded by fourteen secondary attendants, all carved in relatively low relief. Rocana Buddha sits in the middle, flanked by Samantabhadra on the left, riding an elephant, and Manjusri on the right, riding a lion. These three main figures form a triangle and are larger than the others, representing their importance in the group. Behind Samantabhadra and Manjusri stand two guardian kings each. Behind each of these four guardian kings of the four directions stand two bodhisattvas. In the lower left and right corners of the niche are grooms for Samantabhadra’s elephant and Manjusri’s lion. In front of each animal, crouched on either side of the pedestal and located at the bottom of the composition, are the smallest figures in the assembly: two small boys both representing Sudhana. On either side of the lobed outer edge of the niche, carved in even lower relief than the other figures, are two apsaras, one of eight groups of Buddhist guardians. All these figures symbolize a congregation, listening to the preaching by Rocana.

The composition of the Rocana triad of niche no. 5 illustrates a controversial area of study in art history; that is, how to classify Rocana images. In Chinese Buddhist art, although Rocana was not as popular as Amitabha, a number of images are still preserved. Li Jingjie classifies Rocana images in two categories: images of the Buddha of the dharma realm (Ch. Fajie xiang 法界像, meaning the Buddha of the Absolute Reality Realm), and images similar to general Buddhas (). Rocana images of the dharma realm always have images on the surface of their bodies, such as Buddhist figures, worlds and stories from the Huayan sutras. In regard to the Rocana images resembling a general Buddha, Li references inscribed and dated sculptural examples from the Eastern Wei (534–549), Northern Qi (550–577) and Sui (581–618) periods. Some of these early period Rocana sculptures have two attendant bodhisattvas, probably Manjusri and Samantabhadra, forming a triad.

In Chinese Buddhist texts, the Rocana triad is called Huayan sansheng 華嚴三聖 (Three Saints of Huayan). In studying the development of this subject, Kamata Shigeo 鐮田茂雄 () lists some extant images of Rocana, Manjusri and Samantabhadra. The earliest was made in the ninth century. The majority of such images are located in Sichuan province. He includes niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. In Kamata’s list, most of the depictions of the two bodhisattvas ride on animals: Manjusri on a lion and Samantabhadra on an elephant.

Li and Kamata’s research on the classification of Rocana images have their shortcomings; because Li focuses on early images and does not include Rocana images after the seventh century, he makes no mention of the styles of dress seen in the Rocana figure in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, in spite of his reliance on clothing within his classifications of Rocana images. For his part, Kamata does little to differentiate the Sichuan Rocana figures from those at Feilai Feng. All the Rocana figures he lists have two attendant bodhisattvas; while, in niche no. 5, Rocana’s attendant bodhisattvas are actually of two different types, either riding an animal or standing.

Two approaches can be used to classify Rocana images, and niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng can be classified through both approaches. In the first approach, focusing on Rocana only, we find three kinds of images: Buddhas of the dharma realm, Buddhas similar to a general Buddha, and Buddhas wearing a crown and jewels like a bodhisattva. Rocana images of the dharma realm were made mainly between the sixth and twelfth centuries. They were favorite topics for scholars’ research—such as Li Jingjie’s study mentioned above. For the second type, except for the early pieces cited in Li Jingjie’s research, the largest extant inscribed Rocana figure (dated 675, with 17.14 m high) is located in the Great Rocana Image niche (Da Lushena xiangkan 大盧舍那像龕) at Longmen Grottoes of Luoyang, Henan Province (Figure 3). The Rocana figure wearing a crown and jewels in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng belongs to the third type of image in this approach.

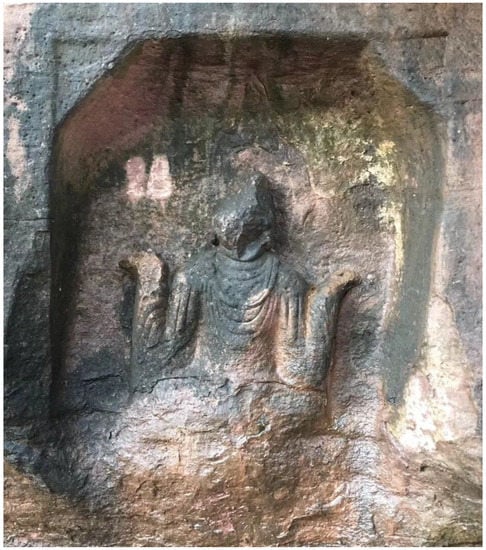

Figure 3.

Rocana Buddha, dated 675, carved in stone—the Great Rocana Image niche at Longmen Grottoes of Luoyang, Henan Province. Photo by author.

The second approach to classifying Rocana images focuses on the attendant bodhisattvas. The first type is the Rocana without any attendants, such as the Buddhas of the dharma realm mentioned above. The second type is the Rocana Buddha flanked by two standing bodhisattvas, such as those of the Great Rocana Image niche at Longmen grottoes, which contains a triad and other attendants.5 The third is a Rocana flanked by two bodhisattvas, riding a lion and an elephant, respectively, such as some images from Sichuan and those in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng.

These two approaches of classification are linked with different religious sources that clarify the textual references for the study of niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. Rocana images of the dharma realm reflect parts of the worlds, stories and figures from the Huayan sutras6 in which the two great bodhisattvas, Manjusri and Samantabhadra, are more important than numerous other bodhisattvas in the Huayan world. Chapter forty-four of the Huayan sutra, translated by Buddhabhadra 佛馱跋陀羅 (359–429), for example, says that when the Buddha preached at Jetavan, a park near Sravasti, Manjusri and Samantabhadra were the two primary bodhisattvas to assist Rocana in the congregation.7 However, other than this, Huayan sutras do not provide any further information about the Rocana triad.

In contrast, Rocana triads are widely discussed in the books and treatises by Chinese monks, especially those of the Huayan school. Huayan sutras themselves make no mention of the animals ridden by Manjusri and Samantabhadra. These unique steeds, as well as Rocana’s crown and jewels, are mainly linked with Buddhist texts outside the Huayan school. The iconographic characteristics of the Rocana triad in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, therefore, can be productively investigated only by examining texts written by Chinese monks from the Huayan school as well as texts originating outside the Huayan school.

3. In the Tradition of Rocana Triad

The development of Huayan Buddhism by eminent Chinese monks from the Huayan school makes it possible for us to propose a theory for the production and installation of the Rocana triad—on which niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng focuses—as it relates to a certain Buddhist ritual. In his article, () summarizes the discussions of the significance, symbol and function of the Rocana triad written by monk Chengguan 澄觀 (738–839), a Huayan patriarch, and Li Tongxuan 李通玄 (635–730), a lay Buddhist master. Kamata suggests that the first person who commissioned a Rocana triad was probably monk Zongmi 宗密 (780–841). Kamata quotes some words from Yuanquejing daochang xiuzheng yi 圓覺經道场修證議 by Zongmi as his proof: “[in the sixth yanchu 嚴處 of seventh gate of the daochang 道场], installing a Vairocana figure on the center, and installing Manjusri and Samantabhadra figures on each side [of the Vairocana, respectively]. These are the Three Saints [Sansheng 三聖].”8

Zongmi’s record may have been regarded as instructions for Buddhists producing and installing Rocana triads during the Tang period. However, we should not view this record as the creation or beginning of worshiping and producing Rocana triads. Monk Fazang 法藏 (643–712), the founder of the Huayan school, mentioned Rocana and the two great bodhisattvas, Manjusri and Samantabhadra, many times in his works (such as in chapter one of Huayanjing tanxuan ji 華嚴經探玄記).9 In addition, in chapter three of the same book, Fazang asserts that Rocana’s attendants are Samantabhadra and other bodhisattvas.10 In chapter seventeen, Fazang states that Manjusri and Samantabhadra are two manifestations of Buddhas from other regions when they want to meet Rocana.11 In chapter one of Huayanjing zhuanji 華嚴經傳記, Fazang claims that when Rocana preached the Huayan sutra, Manjusri and Samantabhadra learned the teaching in person.12 These passages most likely stimulated Buddhist believers to commission Rocana triad images in the second half of the seventh century.

Earlier still, however, Buddhist art provides examples of Rocana triads earlier than Zongmi’s treatise. According to the inscription on the Great Rocana Image niche at Longmen grottoes, it was commissioned by Emperor Gaozong (650–683) and Empress Wu Ze-tian (r. 684–704) and was completed in 675 (). Wu was interested in Huayan sutras and preferred Rocana and the two bodhisattvas. In a preface for the Huayan sutra translated by Siksananda, she says:

Moreover, a stele inscribed with a Rocana triad is now in the collection of Yao Wang Shan museum in the Shaanxi province. The stele was most probably carved during the Sui period (581–618). An even earlier example with a main seated Buddha flanked by two standing bodhisattvas can be seen in the middle cave of Xiaonanhai小南海 (Small Southern Sea) grottoes dated Northern Qi period in Anyang, Henan province. Li Jingjie suggests that the main Buddha is probably a Rocana, based on the carvings of parts of poems from the Huayan sutra on the rock outside this cave (See ). Thus, it is evident that at least by the mid-sixth century, Rocana triad images were being created in China, and probably linked with the study of Huayan Buddhism from that time.Dafangguangfo Huayan jing is the secret canon of Buddhas and the ocean of Buddha-nature. The cause of the vow and act of Samantabhadra and Manjusri act is fulfilled here. Each sentence [of this sutra] contains the boundless dharma realms.[大方廣佛華嚴經者, 斯乃諸佛之密藏, 如來之性海 …… 普賢文殊, 願行之因斯滿。一句之內, 包法界之無邊。]”13

As we have established earlier instances of Manjursi and Samantabhadra’s appearance in Buddhist art, it seems fitting to discuss their most differentiating characteristic among depictions: the animals they ride. Although we cannot find any records about these two bodhisattvas riding their creatures as the attendants of Rocana in Huayan sutras, Buddhist canons outside the Huayan school provide textual references for the basic iconography. In Chinese Buddhist history, Samantabhadra riding an elephant emerged earlier than Manjusri riding a lion. As early as the first half of the fifth century, people could see records of Samantabhadra riding an elephant in Buddhist scriptures. Chapter twenty-eight of the Lotus Sutra, translated by Kumarajiva, says that Samantabhadra rides a white elephant with six teeth.14 At least by the second half of the seventh century, monks from the Huayan tradition accepted this type of Samantabhadra figure. In chapter two of Huayanjing zhuanji, Fazang describes the monk Zhiju 智炬 (ca. sixth cent.), who read Huayan sutra dozens of times, once dreaming of Samantabhadra riding a white elephant.15 In some instances, other esoteric Buddhist scriptures describe Manjusri images riding a white elephant, rather than a lion, as a mode of producing Manjusri images for esoteric Buddhist rituals.16

Probably influenced by the description of scriptures, images of Samantabhadra riding an elephant started to be produced in the fifth century. According to chapter seventeen of Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林 (Jewel forest in dharma garden), a well-known Chinese Buddhist encyclopedia by Tang dynasty monk Daoshi 道世 (ca. seventh cent.), in 460, Empress Dowager Luzhao 路昭太后 of the Liu Song dynasty (420–479) commissioned a figure of Samantabhadra riding a precious chariot and a white elephant. This figure was installed in the Meditation hall (chanfang 禅房) at Zhongxing si 中興寺 (Resurgence monastery).17 Among extant Buddhist art, an early example is a relief sculpture of Samantabhadra riding an elephant on the west wall of the window in cave 9, opened in the second half of the fifth century at Yungang grottoes (). Later, artists carved a large sculpted Samantabhadra of the same type on the rear wall of cave 165. The carving was commissioned by Xi Kangshen 奚康生 (467–521) who was Jingzhou Cishi 涇州刺史 (Governor of Jingzhou) during the period of Emperor Xuanwu (r. 500–515) of the Northern Wei. It is located at the Beishikusi 北石窟寺 (Northern cave temples) in Qingyang county, Gansu province.

By the second half of the seventh century, esoteric Buddhism first introduced Samantabhadra riding an elephant and Manjusri riding a lion as two attendants of a Buddha. Chapter one of Tuoluoni jijing 陀羅尼集經 translated by Indian monk Adiquduo 阿地瞿多 between the years of 653 and 654, instituted a canon for painting the image of the Buddha coming from ushnisha (Foding xiang 佛頂像):

The arrangement and the iconography of the Buddha and the two bodhisattvas in the above record are very similar to those of the Rocana assembly in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng.The Buddha has a golden body and wears a red robe and a seven-precious crown. He sits in a lotus posture on a lotus pedestal. Under his pedestal is a golden wheel and a precious pond, on each corner of which stands a guardian king. Then, on the lower left side of the Buddha, the artist should paint a Manjusri with a white body wearing heavenly clothes, long necklaces and a precious crown, and riding a lion. On the right side of the Buddha should be a Samantabhadra with an appearance similar to that of the Manjusri, but riding a white elephant and holding a sutra case.18

By the second half of the seventh century, Chinese artists accepted Samantabhadra riding an elephant and Manjusri riding a lion as a standard for producing images of these two great bodhisattvas. In caves 331 and 340 of Mogao grottoes at Dunhuang, opened in the second half of the seventh century, we can see the painted images of Samantabhadra riding an elephant and Manjusri riding a lion on the front walls, flanking the main Buddha of each cave (). A sculpted example can be seen in a small niche (niche no. 1325) below the Great Rocana Image niche at Longmen grottoes, representing a seated Buddha flanked by Samantabhadra riding an elephant and Manjusri riding a lion (Figure 4). These three figures display a style characteristic of the second half of the seventh century (). Another sculpted example is preserved in niche no. 4, which contains a Manjusri figure riding a lion commissioned by Wang Chuguang 王楚廣 in 777, in Luohan cave at the Great Buddha Temple in Binxian, Shaanxi (). By the end of the seventh century, seen in the small Longmen niche mentioned above, artists added grooms as attendants to the two bodhisattvas, who usually grasped the reins of the animals, as in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. The best extant early example of this composition is the group of polychrome clay sculptures dated 782 installed in the main hall of the Nanchan si 南禅寺 (Southern Chan monastery) in Wutai shan 五臺山 (Five Peaks mountain), Shanxi province. In this group, Samantabhadra and Manjusri attend the main Buddha, accompanied by their elephant and lion, respectively, and a groom for each of their pets ().

Figure 4.

Manjusri riding a lion with a groom, Ca. eighth century, Tang Dynasty (618–907), carved in stone—niche no. 1325 of Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang, Henan Province. Photo by author.

Apparently, during the Tang period, more and more artists favored depicting Samantabhadra and Manjusri with their animals as a pair flanking a main Buddha. For the Tang examples, no inscribed material has been preserved to substantiate the identities of the main Buddhas. Probably, some of the Buddha figures flanked by the two bodhisattvas on their animals indicate Sakyamuni. On the other hand, because some Rocana figures from the Tang period feature the appearance of a general Buddha similar to Sakyamuni, such as the large Rocana in the Great Rocana Image niche at Longmen, some of the above main Buddhas probably represent Rocana.

By the second half of the eighth century, it became popular to make images of the Rocana assembly with Samantabhadra riding an elephant and Manjusri riding a lion, as well as with grooms, Sudhana and other attendants. A good example of a depiction of such an assembly is cave 155, opened in the ninth century, at Chonglong shan 重龍山 (Double dragon mountain) grottoes in Zizhong of Sichuan province. In this cave, Rocana wears a robe in the tongjian (covering shoulders) mode, similar to that of the Rocana in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. He is flanked by two disciples (who do not appear in niche no. 5). On the sides of Rocana, a Manjusri rides a lion and a Samantabhadra rides an elephant, and each is accompanied by a groom and a little boy. On the side of each of the two great bodhisattvas stands a (lesser) bodhisattva and a guardian king. In total, there are fewer figures than those of niche no. 5.19 The depiction of Manjusri and Samantabhadra similar to Chonglong shan figures flanking a Buddha without a crown can be seen on a Famen Si reliquary, also from about the ninth century ().

Ishida Shoho 石田尚豐 reasonably suggests that the two little boys in the Rocana assembly at Chonglong shan represent Sudhana (). According to chapter sixty-two of the Huayan sutra, translated by Siksananda, Sudhana was a boy from Fucheng 福城 (Blessed City). When Sudhana was born, numerous treasures filled his chamber. In his past lives, he had made offerings to Buddhas and established his good karma without committing any wrongs. People therefore called him Shancai 善財 (Kindness and Assets).20 According to the Huayan sutras, Sudhana once visited and paid homage to fifty-four people, the first being Manjursi, and the last being Samantabhadra. So, in cave 155 of Chonglong shan, the two little boys represent Sudhana in two scenes referencing his visits to each of the two bodhisattvas, probably symbolizing his visit to all of the fifty-four persons. The presence of the two Sudhana figures in cave 155 is so similar to the composition of the Rocana assembly in no. 5 at Feilai Feng that we can only conclude that this is a continuation of the tradition into the first half of the eleventh century.

4. Crowned Rocana/Vairocana

The Rocana figure from niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng wears a crown that links it to esoteric Buddhist art, even though it is thought to be from the Huayan school. None of the extant Huayan Buddhist works from the Tang dynasty, neither in China’s northern regions nor the Sichuan area, depict Rocana figures (flanked by Samantabhadra and Manjusri) wearing crowns, which are the typical iconographic features of bodhisattvas. Probably Tang artists and Buddhists did not choose crowned Rocana as the main Buddha of the Huanyan teaching. However, esoteric Buddhist sutras and commentaries indicate the origin of the Feilai Feng Rocana figure’s crown. Rocana (Vairocana) is the main Buddha in both Esoteric and Huayan Buddhism. Eminent monks from the two teachings explained the meaning of Rocana/Vairocana with a similar concept. In chapter three of Huayanjing tanxuanji, Fazang says:

In Da Piluzhena chengfo shenbian jiachi jing shu 大毗盧遮那成佛神變加持經疏 (a.k.a. Dari jing shu 大日經疏), an important work of esoteric Buddhism, Tang monk Yixing 一行 (ca. 673–727) says that: “Indian pronunciation of Piluzhena (Vairocana) is another name of the sun, meaning the removing of dark and shining everywhere.”22 This is why Rocana/Vairocana also is called Dari rulai 大日如来 (Great Sun Buddha).Today [I] check the Indian version [of the Huayan sutras] again; all of them call [the superior Buddha] Piluzhena 毗盧遮那 (Vairocana). Lushena 盧舍那 (Rocana) could be translated as Light Shining (Guangmingzhao 光明照). Pi 毗 (Vai) is “universally.”[So the name of this Buddha] is called Light Universally Shining (Guangming bianzhao 光明遍照).21

The similar conceptual meanings of Rocana and Vairocana make the crowned Rocana possible to be shared in the two teachings. The origin of the iconography of crowned Rocana is mentioned in the esoteric Dari jing 大日經 (Great Sun sutra), translated by Indian monk Subhakarasimha 善無畏 (637–735) and Yixing in 724. This scripture says that Rocana’s hairstyle (chignon) acts as his crown, which in art has translated to the Buddha’s hair looking like a crown. Chapter four of Dari jing shu by Yixing says that Vairocana looks like a bodhisattva, because he wears a chignon as if he wears a crown.23 Since there appears to be no Rocana Buddha images of the Tang dynasty Huayan school that depict the deity wearing a crown, instead of the crowned Vairocana Buddhas of esoteric Buddhism, these esoteric sutras may have been the textual references for the production of Rocana images for Huayan Buddhism as well.

In addition to textual references, there are also Esoteric artistic references related to the imagery for crowned Rocana images. There are many seated Buddha figures wearing a crown, with Buddha’s robe in the youtan (exposing right chest and arm) mode and wearing bodhisattva’s jewelry, found in Xi’an, Luoyang and Sichuan areas, produced in the period from the second half of the seventh century to the first half of the eighth century. Most of them do not have any surviving inscriptions, but one example of such an inscription is attributed to the Tang dynasty and accompanies a crowned Buddha, preserved in Putiruixiang ku 菩提瑞像窟 (Bodhi (enlightened mind) Auspicious Image cave) at Qianfoya grottoes in Guangyuan, Sichuan. The image portrays Buddha wearing a robe in the youtan mode, a bodhisattva-style crown, necklace and bracelets. According to Luo Shi-ping 羅世平, this figure was probably made during the reign of Emperor Ruizong (r. 710–712) (). The cave’s original inscription says that the main figure is an Auspicious Buddha Image under the Bodhi tree, indicating Sakyamuni was receiving enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. In the same cave, a Five Dynasties inscription claims that in 924, Yueguo furen 越國夫人 (The Lady of Yue Kingdom) commissioned the re-painting and refurbishing of the sculptures in this cave, referring to the main Buddha as “Vairocana” (). Obviously, the new patron re-identified or reassigned the image and gave it a new identity from Sakyamuni to Vairocana, and the Lady of the Yue Kingdom and the artists who refurbished the images probably understood that this was the standard iconography for Rocana/Vairocana figures during the tenth century.24 This appearance of the figure can be linked with the tradition of producing crowned Buddhas in the north and the esoteric texts mentioned above. In other words, it is possible that the artists created Rocana figures related to Huayan teachings that included iconographic characteristics borrowed from esoteric Buddhist art in the Five Dynasties period. Consequently, Song dynasty artists inherited this tradition, and the crowned Rocana from no. 5 at Feilai Feng was the result.

Compared with the previously listed extant Tang examples, the Rocana figure in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng features some unique iconographic characteristics (Figure 5). He wears a crown with three-pointed plaques, similar to that of a bodhisattva, with a ribbon hanging from both sides of the crown and draping over his shoulders. In contrast, the crowns that most Tang Buddha figures wear are broad, resembling those of the two standing bodhisattvas in the Great Rocana niche at Longmen, without any separated plaques and ribbons. I can only find one Buddha figure wearing a three-points-plaqued crown without a ribbon from the stone images of the Guang Zhai monastery in the Tang period capital Chang’an (present-day Xi’an in Shaanxi province).25 That peculiar crown of the Rocana in niche no. 5 probably reflects a tradition of the Huayan school that was not popular in the Tang period. The Feilai Feng Rocana, in addition, wears a Buddha robe in the tongjian mode, recalling that of the Rocana Buddhas of the dharma realm.26 In contrast, Tang crowned Buddha figures usually wear a robe in the youtan mode.

Figure 5.

Seated Rocana Buddha, dated 1022, carved in stone—niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. Photo by author.

The gesture of the Feilai Feng Rocana renders another distinctive aspect: he bends his arms at the elbows, raising his forearms so that they are exposed; his wrists are flexed, and his thumb touches his third-finger while the palm is exposed and faces upward. Both hands form an identical gesture. In extant crowned Buddha figures from the Tang dynasty, this gesture cannot be found; however, these gestures do still exist in general, uncrowned Buddha figures from the Tang dynasty. An example can be seen in Jinguang Qianfo Cliff images in Renshou County, Sichuan Province (Figure 6). However, this gesture for a Buddha figure was not popular in the Tang Dynasty, and there is no such combination of Rocana Buddha flanked by Manjushri riding a lion and Samantabhadra riding an elephant. In view of that, it is unreasonable to say that the artist who carved the Feilai Feng Rocana was contributing, historically, to the Tang style, although he could have been inspired by a Tang tradition.

Figure 6.

Seated Buddha, Ca. eighth–nineth century, Tang Dynasty (618–907), carved in stone—Jinguang Qianfo Cliff images in Renshou County, Sichuan Province. Photo by author.

5. Artistic Sources for Niche no. 5

Now an essential question should be asked: where is the source of the Rocana Assembly in niche no. 5? Kamata suggests that Rocana triad images were transmitted from the Sichuan area to the east during the Five Dynasties and Song periods, and niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng is a result of this influence (). The problem is that, so far, among the extant Tang images in Sichuan, a Rocana Assembly with iconographic characteristics similar to those in niche no. 5 cannot be found. A similar assembly can be found in a Five Dynasties site in Hangzhou. The preceding discussion suggests that Tang crowned Buddha images provide similar iconographic characteristics and the sculptures in Sichuan caves reveal a similar composition to those of the Rocana assembly in niche no. 5. Furthermore, compared with the Northern Song capital Kaifeng, Feilai Feng was clearly not the most important place to produce images from Huayan teaching in the eleventh century. All Tang, Five Dynasties, and Song images, therefore, could be the possible artistic sources for the carving of niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng.

Niche no. 5 reflects some iconographic and stylistic characteristics of Tang Buddhist images. As I mentioned above, Tang images in the north and Sichuan areas feature a crowned Rocana and a composition of Rocana assembly similar to those of niche no. 5. A Tang Buddha figure in Sichuan performs a similar gesture to that of the Rocana of niche no. 5. In addition, having two apsaras carved above a niche, as seen in niche no. 5, was a popular arrangement among Tang dynasty stone images, such as in the stone niches from the Guang Zhai monastery in Tang dynasty Chang’an (See ). As for the four guardian kings carved in niche no. 5, the one standing behind Manjusri on the right holds a pagoda, depicting Vaisravana, the guardian king of the North. In Tang art, guardian king figures often make a pair, one of whom holds a pagoda. This pattern can be seen in the carvings of the late seventh century and early eighth century Longmen grottoes. The rerebrace (armor covering the upper arms) that Vaisravana wears are horizontally striped, resembling the wooden carved Vaisravana figure moved from Tang dynasty Chang’an in the collection of Toji 東寺 (Eastern monastery) in Kyoto, Japan (See ). Additionally, the Rocana and two bodhisattvas in niche no. 5 have slender bodies, a typical style of Tang images. Unquestionably, niche no. 5 contains Tang elements; the artist possibly adopted those elements from Tang works, which could be derived from Tang dynasty Chang’an and Luoyang and imported from ninth or tenth century Sichuan area.

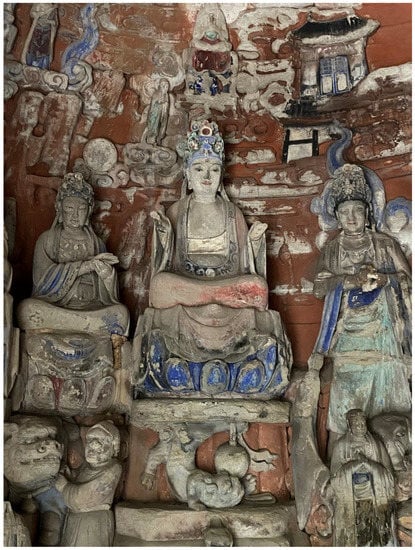

The artist may have also followed the model of Five Dynasties (907–960) Buddhist art, which the Tang dynasty heavily influenced. Consequently, it may be incorrect to attribute the elements seen in niche no. 5 to the Tang Dynasty solely, as artists from the Five Dynasties utilized familiar Tang elements in their work frequently. Those differences that may mark the difference between Tang and the Five Dynasties are also present among art from the Song period. A good example is the pedestal of the Rocana figure in niche no. 5. This Buddha sits on a lotus with double-carved petals pointing upward, supported by a narrow pedestal. The waist of this pedestal has three lobes on either side that flow into a stylized leaf, above the center of which is a round jewel. The top of the pedestal has two levels, composed of three lobes each, with the center lobe larger than those on the sides. The foot of the pedestal is composed of four stepped levels; each has four lobes that gradually become larger toward the bottom. Actually, this stylized carved lotus throne in bas relief is similar to bases of Buddhist figures made in the Wuyue kingdom (893–978), located in southeast China at Hangzhou, such as those in niche no. 16 at Feilai Feng and niche no. 3 at Zixian monastery of Hangzhou (Figure 7). In addition, the Wuyue kingdom had a tradition of producing Manjusri and Samantabhadra images in which they ride animals, as can be seen carved on the top of niche no. 3 at Zixian monastery (). Chapter eighty-one of Xianchun Lin’an zhi 咸淳臨安志 (Gazetteer of Lin’an Written in the Xianchun Reign (1265–1274)) by Qian Yueyou 潛說友 (jinshi 1244) mentions that the Wuyue king (Qian Chu, r. 947–978) commissioned the Wenshu Puxian yuan 文殊普賢院 (Manjusri and Samantabhadra cloister) in 955 in Hangzhou (See ). The images of the two bodhisattvas in this cloister probably shared a similar appearance with those of niche no. 3 at Zixian monastery and niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. The Feilai Feng Samantabhadra wears an inner robe in the youtan mode and bares his right chest and both arms; there is a string tied on his lower chest. This type of inner robe was popular in the bodhisattva images made in the Wuyue kingdom, such as the images of Zixian monastery (). Accordingly, the artist who carved niche no. 5 probably had Tang references transformed by Wuyue artists or artists from the North and inherited some new elements of the tenth century.

Figure 7.

Seated Bodhisattva, ca. tenth century, carved in stone—niche no. 3 at Zixian monastery of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. Photo by author.

In addition, a Rocana Buddha with the special gesture, flanked by Manjushri and Samantabhadra riding their animals, could be found on a painting and a Buddhist site from Five Dynasties. Among the silk scroll paintings removed from the Dunhuang library, there is a Five Dynasty one revealing representations of the Huayan Sutra in the collection of the Guimet Museum in Paris, France. The painting focuses on the Buddha’s Nine Teachings in Seven Places, and one section represents the Rocana Buddha performing the same gestures as seen in the Feilai Feng Rocana.27 On the top of the south wall of the Stone Buddha Cave of Huiri Peak, behind the Jingci Monastery in Hangzhou, are three statues of the Rocana Buddha and his attendants. Among them, the Rocana wears a robe that covers his shoulders, and performs the same gesture to the Feilai Feng Rocana. He has two attendants, Samantabhadra on his elephant and Manjushri on his lion (Figure 8). The head of this Rocana has been damaged, and it is unknown whether he once wore a crown or not. The niche was carved in the middle of the tenth century, shortly after the establishment of Jingci Monastery in 954 CE, and provides us with key information on the development of this special Rocana Assembly during the Five Dynasties ().

Figure 8.

Rocana triad, tenth century—the Stone Buddha Cave at Huiri Peak behind the Jingci Monastery in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. Photo by author.

Northern Song capital Kaifeng, moreover, was also a possible source for the transmission of the Rocana assembly to the Hangzhou area. After 978, when Wuyue king Qian Chu conceded his kingdom to the Northern Song court, Kaifeng became the political, cultural, and Buddhist administrative center for the Hangzhou area. Da Xiangguo si 大相國寺 (Great Assisting the State monastery) was the largest and most important monastery in the capital. Under the imperial patronage, Xiangguo monastery had been largely repaired and rebuilt from 995 to 1001. Many famous artists were involved in the reconstruction by painting the murals there. Sculptures were moved from local areas and installed in its halls (). At that time, Xiangguo monastery collected a number of gems of contemporaneous Buddhist art, showing some orthodox modes of Buddhist art in the early period of the Northern Song. Those works no longer exist, but one can count on their presence having had a certain impact on local regions after 1001. In 1072, when Japanese monk Jojin 成尋 visited the Xiangguo monastery, he recorded that there existed a Rocana hall, on the western tower of which was a Manjusri figure riding on a lion flanked by his attendants, and on the eastern tower was a Samantabhadra figure riding on an elephant flanked by his attendants (). Evidently, the images installed in the Rocana hall and the two towers formed a large-scale Rocana assembly, but their iconographic characteristics remain unknown.

The two woodblock prints in the collection of Seiryo ji 清涼寺 (Cool and refreshing monastery) in Kyoto provide clues to help us figure out the features of the two great bodhisattvas in Xiangguo monastery. In 988, Japanese monk Chonen brought a red sandalwood image of Sakyamuni from China to Japan. Many Buddhist objects were crammed into the body of this Buddha figure, which had been closed in Kaifeng in 985, just before Chonen left on his journey home. Among the objects inside the figure, a woodblock print depicts Manjusri riding his lion and another one represents Samantabhadra riding his elephant (). The two prints can make a pair, with a Sudhana as well as a groom assisting each bodhisattva, respectively. If we put the two prints together, the composition is very similar to those of the two great bodhisattvas in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng.28 According to the inscription, the original picture from which the block was cut was drawn by famous painter Gao Wenjin 高文進 (d. after 1008), one of the artists involved in the artistic production in Xiangguo monastery (). It is possible that the two prints reflect some iconographic characteristics of the two bodhisattvas at Xiangguo monastery. About twenty years after the completion of the Rocana assembly at Xiangguo monastery, niche no. 5 was engraved on Feilai Feng cliff. Presumably, the Rocana assembly of niche no. 5 reflects some of the same types of sculptures from Xiangguo monastery in the capital.29

6. Huiyin Monastery and the Transmission of Rocana Triad

After niche no. 5 was carved at Feilai Feng in 1022, many of the Rocana figures and Rocana triads had been produced in the new mode seen in this niche, i.e., with Rocana wearing a crown and performing the mudrā seated between Manjusri and Samantabhadra riding their lion and elephant. As I mentioned above, Tang dynasty Rocana figures from Rocana triads do not have the same features as the Rocana figure in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. However, we can see some figures resembling the Feilai Feng Rocana in the Sichuan area during the Song period. One can see a seated Vairocana figure flanked by Manjusri with his lion and Samantabhadra with his elephant in Huayan Sansheng ku 華嚴三聖窟 (Huayan Three Saints cave), which was opened in the Southern Song period, at the Huayan dong 華嚴洞 (Huayan cave) grottoes in Anyue county, Sichuan (Figure 9). The differences of the Rocana figure, compared with niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, are as follows: in the cave depiction of the Rocana, his crown is broader; his robe is worn in baoyibodai mode; he wears a broad robe that covers the shoulders, but reveals another robe underneath that is tied above the waist (). Song period cave 3 of Miaogao shan grottoes in Dazu county, Chongqing, has a seated Rocana wearing a crown and flanked by Manjusri riding a lion and a Samantabhadra riding an elephant. Above the Rocana are two apsaras. To the side of each bodhisattva are a groom and a Sudhana figure (). Clearly, some features of the Rocana assembly in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, such as the composition and crowned Buddha, were also in use in Sichuan by the end of the eleventh century.

Figure 9.

Rocana Assembly, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), carved in stone—Huayan Three Saints cave at Huayan Cave Grottoes in Anyue County, Sichuan Province. Photo by author.

A few Buddha figures outside Hangzhou portray a similar mudra to the Rocana figure in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. There is a single Buddha statue without a crown on the Lianfeng Stone Pagoda in Minhou, Fujian, with a similar gesture to the Feilai Feng Rocana, dating from the Song Dynasty (Figure 10). In cave 14 of Dafo wan 大佛灣 (Great Buddha bay) in the Baoding grottoes (dated in Southern Song), Dazu, Chongqing, there are a group of crowned Rocana Buddha figures representing Rocana’s Nine Meetings, with different decorations on their crowns. One of them forms a similar mudra to the Rocana in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, and on his crown is a carved sun (Figure 11) (). Additionally, on the Falun ta 法輪塔 (Dharma Wheel Pagoda) of Xiaofo wan 小佛灣 (Small Buddha bay) at Baoding grottoes, a seated Buddha with a general Buddha’s appearance also forms the mudra resembling that of the Rocana in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. About ten Buddha figures are carved on the same pagoda, and this figure is located on the second stage (). In the Baoding grottoes, another seated Buddha with similar mudra is carved on the third stage of the Jingmu ta 經目塔 (The pagoda of sutra catalog) (Figure 12). Another Rocana Buddha wearing a crown and forming a Zhiquan mudra is carved on the same side above the second stage (). Although it is possible that some of the above figures with a similar mudra to the Feilai Feng Rocana could not be defined as Rocana, their resemblance probably indicates a kind of connection between Hangzhou and Sichuan.

Figure 10.

Seated Buddha, Song (960–1279), carved in stone—Lianfeng Stone Pagoda in Minhou, Fujian Province. Photo by author.

Figure 11.

Rocana Buddha, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)—cave 14 of Dafo wan in Baoding grottoes, Dazu, Chongqing City. Photo by author.

Figure 12.

Seated Buddha, Southern Song (1127–1279), carved in stone—Jingmu pagoda at Baoding grottoes, Dazu, Chongqing City. Photo by author.

Another example is the Vairocana image painted in The Long Roll of Buddhist Images attributed to Zhang Shengwen 張勝溫, a painter of the Dali kingdom (937–1253). The inscription to the side of this Vairocana says that “Namo Dari bianzhao fo” 南無大日遍照佛 (Hail to the Buddha of the Great Sun shining everywhere) (). He sits in a lotus posture on a lotus pedestal and wears a Buddha’s robe in the tongjian mode, on which there are some painted images of the Buddhist world. He does not wear a crown and his ushnisha is visible. He bends his arms and raises his hands to the same level as his shoulders. His mudra and the mode of his robe are identical to those of the Northern Song Rocana figure at Feilai Feng. This scroll is dated between 1173 and 1176, during the Song period, which puts its creation after the creation of the Feilai Feng Rocana.

Hence, if there was any influence between the two regions, probably Hangzhou had an impact on Yunnan. This can be first seen to be, in some respects, influenced by the Song on The Long Roll. In the Buddhist pantheon depicted in The Long Roll, there are sixteen luohans, a subject popular from the tenth century onward.30 In this painting, each of the Six Chan Patriarchs sits on a chair, portraying a custom that began in the tenth century in China. We can see some Buddha figures sitting on a chair from the Tang or pre-Tang period. This tradition came from India but is limited to Buddha figures, as Chinese people did not sit on chairs until the tenth century. The presence of chairs in historical paintings of monks is a quick test to the home and customs of the artist. Among the extant paintings from the Song period, one can easily find a figure sitting on a chair, such as a set of paintings depicting The Ten Kings of the Hell from the workshop of Lu Xinzhong 陸信忠 at Ningbo (in Zhejiang province), dated to the thirteenth century.31 Some portraits of Buddhist monks by Song artists also reveal the same custom, as a portrait of Tang priest Amogha 不空 (743–774) attributed to the Northern Song painter Zhang Sigong 張思恭, but probably painted in the Southern Song period, in the collection of Kozanji, Kyoto (). This representation cannot be found from the extant Tang period art. When The Long Roll was painted, the artist most likely adopted references from Southern Song, probably directly from the capital Hangzhou.

The preceding discussion still cannot suggest a direct influence from niche no. 5 to the works in Sichuan and Yuannan. A Huayan center, the Huiyin monastery, that most likely contained the similar iconography, could be found in the Hangzhou area during the Song period. In 927, the Wuyue king Qian Liu (r. 893–931) commissioned the construction of the Huiyin monastery, a Chan monastery, in Hangzhou (). In the early period of the Yuanyou reign (1086–1094), the Korean Buddhist Controller Uichon 義天 went to Kaifeng. He asked the Song court to teach him about Huayan and help him bring those teachings to Korea. In 1088, the Huiyin monastery in Hangzhou was known to be the monastery where the Korean monk could study Huayan. At the same time, the court changed the Huiyin monastery from a Chan institution to be a Ten-direction Teaching Cloister (Shifang jiaoyuan 十方教院) belonging to the Huayan school (). From that time onward, Huiyin monastery was the most important place for the study of Huayan teachings. In 1101, the Korean king sent an envoy to commission a hall for Huayan sutras at the Huiyin monastery, and to commission the installation of a Rocana figure flanked by Samantabhadra and Manjusri in the same hall (See ).

The Huiyin monastery continued to play a key role in Huayan teaching during the Southern Song period; in particular, it had a close relationship with the Southern Song imperial family. Emperor Ningzong (r. 1195–1224), for example, wrote a name plaque of Huayanjing ge 華嚴經閣 (Pavilion of Huayan sutras) for the monks of Huiyin. During the Baoqing reign (1225–1227) of Emperor Lizong (r. 1225–1264), the court established Sheyu dian 神御殿 for the benefit of Emperor Ningzong and Lengyan zhushengqi chantang 愣嚴祝聖期懺堂 in the monastery. Meanwhile, the court commanded to place the coffin of Princess Chengguo 成國公主, an imperial aunt, at Huiyin to make offerings. In the Chunyou reign (1241–1252), Emperor Lizong (r. 1225–1264) commanded that Guangguo yuan 廣果院 (Extending Fruit cloister) belong to the Huiyin monastery (). These records represent a strong patronage from the Southern Song imperial family, keeping the essential status of Huiyin as the chief leading monastery of Huayan teaching.

Because of the impact of the Huiyin monastery, the Rocana triad of the Huiyin monastery could have served as a reference for artists to create their own images in local regions (including Sichuan and Yunnan) during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Huiyin triad no longer exists, but the triad in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng may give us some idea of its appearance, since it represents some typical iconographic characteristics and contemporary style. Based on above comparisons between Feilai Feng images and the images from Sichuan and Yunnan, the similarities suggest a transmission in these three areas. Niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng cannot accurately be regarded as the influencing work for the following examples and traditions; it is more likely a representative example of this transmission. It also reflects the change in the depiction of this subject, at least beginning in the eleventh century, compared with Tang works. The appearance of the Rocana triad in the Huiyin monastery probably had similar iconographic characteristics to those rendered in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. Through examining the influential Huiyin monastery, the similarities of Rocana images between Hangzhou, seen in Feilai Feng figures, and Sichuan and Yunnan are revealed.

Niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng also can help us to examine the transmission of Huayan teaching between Hangzhou and Japan. Many painted Rocana figures in Japanese collections share the similar mudra to that of the Feilai Feng Rocana. Around 1185, the late period of Heian 平安 and early period of Kamakura 鐮倉, Vairocana and Sudhana images related to the Huayan sutras became a popular subject in painting. Ishida Shoho suggests that this phenomenon was probably related to the transmission of Huayan belief from the Song Empire (). In the painting of Kegon kaie zenchishiki zu 華嚴海會善知識圖 (Painting on the good teachers in the sea congregation of Huayan), from the collection of Todaiji 東大寺 in Nara, Vairocana sits on the upper center, depicting a pose and mudra resembling that of the Feilai Feng Rocana figure in niche no. 5, surrounded by virtuous visitors (). Similar to the latter, the Todaiji Vairocana also wears a crown and a Buddha’s robe in tongjian mode with the collar largely opened, showing his necklace. There is one different iconographic characteristic: he has an inner garment with a string tied on his lower chest, and his long hair falls on his shoulders. A similar Vairocana figure can also be found in the painting of Gosho mandara zu 五聖曼荼羅圖 (Painting of five saints Mandala), probably painted in the late Kamakura period 鐮倉 (1192–1333), from the collection of Kozan ji 高山寺 (High Mountain monastery) (). One can see that the iconography of these Vairocana images likely shared a prototype. In his treatise, Kegon bukko zanmaikan hihozo 華嚴佛光三昧觀秘寶藏 (Secret treasure deposit of meditation of Huayan Buddha light), the Japanese monk Myoe 明惠 (d. 1232) from Kozan ji mentioned that Vairocana figure with the mudra similar to that of the Rocana figure in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, associated with the Tang mode. Ishida holds a different perspective: the Todaiji painting demonstrates elements of the Song style, and the artist probably had reference from the Song kingdom (). This assertion is reasonable.

Through the search for the source of the Vairocana images in Japanese paintings, Ishida describes two Chinese works. One is a painting of a Vairocana triad, representing a posture and mudra similar to the Rocana in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng but with his hands in front of his chest, in the collection of Kencho ji 建長寺. On the lower left side is Manjusri riding a lion, and on the lower right is Samantabhadra riding an elephant. The arrangement resembles the three main figures of niche no. 5. This painting was brought by Chinese monk Rankei Doryu 蘭渓道隆 (1213–1278) from the Southern Song to Japan in 1246 (). Another work is niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng, and Ishida suggests that this niche represents a mode of Rocana assembly popular in the Zhejiang area during the Song period. So, he believes that Zhejiang was probably the source for importing the iconography of Huayan painting into Japan during the early period of Kamakura ().

Ishida’s point is convincing, but the specific relationship between Japanese Huayan painting and the niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng still needs clarification. The preceding discussion reveals the essential status of the Huiyin monastery in Huayan teaching in the Song period. The non-extant Vairocana triad figures at the Huiyin monastery probably featured iconography similar to the earlier one in niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. When Japanese monks visited the Southern Song Empire and planned to bring Huayan paintings, as models for their new production, back to Japan, the Huiyin monastery would have been their first choice. Niche no. 5, therefore, can be considered as a bridge to connect Huayan belief and art between Hangzhou—particularly the Huiyin monastery—and Japan.32

Niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng also represents the transmission of Huayan teaching between Hangzhou and Korea. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, houses a Korean Buddhist scroll painting of a transformation tableau of Yuanjue jing, or the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment (圓覺經). The scene depicted in the painting represents the court of the Vairocana Buddha. Flanked by the bodhisattvas Manjusri and Samantabhadra, the central deity Vairocana sits in the lotus position with his hands assuming an unusual mudra similar to No. 5 of Feilai Feng. Representational habits and comparisons with dated works suggest that this painting was produced in the first half of the fourteenth century, and the round patterns on the costumes of the central deities reflect a common Goryeo period attribute. The images found in Hangzhou should be the key to understanding the iconography and references of the Boston Goryeo scroll, which reveals the transmission of Huayan Buddhist art from China to Korea ().

7. Conclusions

The Huayan sutras are important references in Chinese Buddhist history for the worship of the Rocana Buddha; however, they provide little help in understanding the worship for the larger Rocana triad in niche no. 5 at the Feilai Feng complex. The Rocana triad images are primarily linked to the Buddhist texts written by Chinese monks which established the principle for teaching the Huayan ritual during the Tang period.

With regard to the iconographic characteristics of the two bodhisattvas of the triad in niche no. 5, the bodhisattva Samantabhadra rides an elephant while the bodhisattva Manjusri rides a lion. They are probably associated with Buddhist texts and artistic productions that are outside the Huayan school, possibly related to esoteric Buddhism. Similarly, the crowned Rocana, in niche 5, is likely derived from an older tradition dating to the Tang and Five Dynasties periods. Similar descriptions can be found in esoteric Buddhist texts and images.

Nevertheless, niche no. 5 is the earliest extant example of a Rocana triad represented by a central crowned Buddha with a special hand gesture or mudra, probably unfamiliar to Tang artists, and flanked by two bodhisattvas riding animals. From niche no. 5, one can see the development of the Huayan Rocana triad created in the tenth century. This niche also indicates that Buddhist artists, when they created a new form of iconography, were not limited by the boundaries of different schools or teachings. The specific iconography of niche no. 5 can also be linked to the Han-style Buddhist artistic traditions from previous periods, such as the Tang, Five Dynasties/Wuyue Kingdom and the contemporary Northern Song capital, Kaifeng, which was likely the most direct influence.

The Rocana Buddhist triad at niche no. 5 is likely reflective of the iconography of the Rocana triad installed at the Huiyin monastery at a later time during the Northern Song Dynasty. In turn, the similarities between the images in niche no. 5 and those from other regions, such as Sichuan, Yunnan and Japan, most likely reveal the connection between the Huiyin monastery and these other sites.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | There are three translations of this sutra. Indian monk Buddhabhadra 佛馱跋陀羅 (359–429) translated the sutra into sixty chapters in Yangzhou from 418 to 420 during the Eastern Jin period (317–420). During the Tang period (618–907), Khotan monk Siksananda 實叉難陀 (652–710) translated the sutra into eighty chapters from 695 to 699 in the eastern capital Luoyang. In 798, Kashmir monk Prajna 般若 translated the Huayan Sutra into forty chapters. |

| 2 | In the three Huayan sutras, we can see both names of Lushena (Rocana) and Piluzhena (Vairocana) acting as the same superior Buddha of the Lotus World and dharma realm. In the Huayan sutra translated by Buddhabhadra, the Buddha of dharmakaya just has one name: Lushena. In the Huayan sutra translated by Siksananda, we can see this Buddha has two names: Lushena and Piluzhena or Pilushena 毗盧舍那. In the version translated by Prajna, the translator also uses two names: Lushena and Piluzhena. Both Lushena and Piluzhena have the same meaning, and I will discuss them below. |

| 3 | For general information about Buddhist sculptures at Feilai Feng, see (; ). |

| 4 | The inscription can be seen in (). |

| 5 | Kamata, however, suggests that making Rocana triads began in the early period of the ninth century. See (). |

| 6 | Except for the three different versions of Huayan sutra, there are other sutras related to worship Rocana Buddha. See (). |

| 7 | Taisho 9. 676a. |

| 8 | Xuzangjing 128. 365a. |

| 9 | Taisho 35. 107a. |

| 10 | Taisho 35. 154c. |

| 11 | Taisho 35. 420a. |

| 12 | Taisho 51. 153a. |

| 13 | Taisho 10. 1a. |

| 14 | Taisho 9. 61ab. |

| 15 | Taisho 51. 158c. |

| 16 | For example, According to Dasheng miaojixiang pusa mimi bazi tuoluoni xiuxing mantuluo cidi yiguifa 大聖妙吉祥菩薩秘密八字陀羅尼修行曼茶羅次第儀軌法 translated by the Indan monk Jingzhi 淨智 in the Tang, in the second yard of the Mandala, monks should install eight Manjusri images. Each of them rides a lion and faces the main figure in the center of the Mandala. See Taisho 20. 785b. |

| 17 | Taisho 53. 408c. |

| 18 | Taisho 18. 790a. |

| 19 | (). The authors suggest that cave 155 was carved in the Song period. However, the similarity between cave 155 and 93 is clear, and the latter was opened before 854. |

| 20 | Taisho 10. 332abc. |

| 21 | Taisho 35. 146c. |

| 22 | See chapter one of this sutra, in Taisho 39. 579a. |

| 23 | Taisho 39. 622b. |

| 24 | Regarding why The Lady of Yue Kingdom changed the identity of the seated crowned-Buddha figure from Sakyamuni to Vairocana, see (). |

| 25 | See (). Now this stone niche is in the collection of Bunda cho 文化厅 in Tokyo. |

| 26 | Li Jingjie published some Rocana images of dharma realm made in the Northern Zhou, Sui, and Tang periods. Most of these figures wear a robe in tongjian mode. See (). Matsubara Saburo published a Tang bronze standing Buddha of dharma realm in the collection of Musée Guimet, Paris, see (). |

| 27 | (). About the Buddha’s Nine Teachings in Seven Places from Huayan sutra, see (). |

| 28 | (). For a reproduction of the two woodblock prints, see (). |

| 29 | Asian Art Museum of San Francisco collects a stone carved seated Rocana figure, which expresses the style from the Liao Kingdom (907–1124). This Buddha figure performs the similar mudra to that of the niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. Removed from the North, the figure probably represents the iconographic characteristics similar to Northern Song Buddhist art. See (). |

| 30 | About the Long Roll, see (). |

| 31 | A few sets of Ten Kings paintings now in the collections of Japan and other countries. Some reproductions can be found in the article by Lothar (). |

| 32 | Niche no. 5 also considered as a bridge to connect Huayan belief and art between Huiyin monastery of Hangzhou and Korea. The Museum of fine Arts in Boston owns the only known example of a transformation tableaux of the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment with typical style of Buddhist painting from Goryeo kingdom (918–1392). According to Yukio Lippit, “Representational habits and comparison with dated works suggest that this painting was produced in the first half of the fourteenth century.” The Rocana Buddha in this painting performs the same type of mudra as niche no. 5 at Feilai Feng. See (). |

References

Primary Sources

Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大藏經 [The Buddhist Canon Newly Compiled during the Taishō Era]. 100 vols. 1924–1935. Takakusu Junjirō高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡边海旭, eds. Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai.Secondary Sources

- Chang, Qing 常青. 1995. Hangzhou Ciyun ling Zixian si moya zaoxiang 杭州慈雲嶺資賢寺摩崖造像 [Images of Niches on the Cliff at Zixian Monastery at Mount Ciyun in Hangzhou]. Wenwu 10: 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Qing. 1998. Binxian dafosi zaoxiang yishu 彬縣大佛寺造像藝術 [Iconic Art of the Great Buddha Temple in Binxian]. Beijing: Xiandai chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Qing. 2013. Form and Reference of the Goryeo Painting of Rocana Assembly from The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Journal of Korea Art & Archaeology 7: 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Qing. 2019. Hangzhou Jingcisi hou Huiri feng Fojiao moya kukan zaoxiang 杭州凈慈寺後慧日峰佛教摩崖窟龕造像 [The Buddhist Cave and Cliff Images at Mount Huiri behind Jingci Monastery in Hangzhou]. Wenbo 2: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Junji 陳俊吉. 2015. Zhongtang zhi Wudai Huayanjingbian de Rufajiepin tu tanjiu 中唐至五代華嚴經變的「入法界品圖」探究 [The research of the painting of entering the Dharma Realm of Avataṃsaka Sutra in the Tang Dynasty to the Five]. Shuhua yishu xuekan 書畫藝術學刊 18: 133–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Huafeng 董華峰. 2013. Cong Putiruixiang dao Piluzhena: Xinyang bianqian yu zaoxiang de chongsheng 從菩提瑞像到毗盧遮那:信仰變遷與造像的重生 [From Auspicious Bodhi Image to Vairocana: The Faith Change and the Statue Rebirth]. Journal of Sichuan University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition) 四川大學學報 (哲學社會科學版) 4: 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dunhuang wenwu yanjiusuo. 1987. Zhongguo shiku-Dunhuang Mogaoku 中國石窟-敦煌莫高窟 [Chinese grottoes-Mogao Grottoes at Dunhuang]. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Richard. 1984. Pu-tai-Maitreya and a Reintroduction to Hangchou’s Fei-lai-feng. Ars Orientalis 14: 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Nianhua. 2002. Feilai Feng zaoxiang 飛來峰造像 [Images of Feilai Feng Peak]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Guangyuanshi wenwu guanlisuo. 1990. Guangyuan Qianfoya shiku diaochaji 廣元千佛崖石窟調查記 [A Survey of the Thousand-Buddha Cliff Grottoes in Guangyuan]. Wenwu 6: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, Gregory, and Leon Hurvitz. 1956. The Buddha of Seiryoji: New Finds and a New Theory. Artibus Asiae 19: 5–6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hising, Yun 星雲. 2013. Encyclopedia of Buddhist Arts 16·Painting 3 世界佛教美術圖說大辭典16·繪畫3. Gaoxiong: Fo Guang Shan Board of Directors. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Angela. 2001. Summit of Treasures: Buddhist Cave Art of Dazu, China. Trumbull: Weatherhill, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Hisatoyo 石田尚豐. 1988. Kegonkyō e 華嚴經繪 [Paintings of the Huayan Sutras]. In Nihon no bijutsu 日本の美術 [Japanese Art], no. 270. Tokyo: Shibundo, pp. 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Zhiqi 蒋之奇 (1031–1104). 1976. Hangzhou Huiyin jiaoyuan Huayan ge ji 杭州慧因教院華嚴閣記 [Record on Huayan Hall of the Huiyin Teaching Cloister in Hangzhou]. In Yucen shan Huiyin Gaoli Huayan jiaosi zhi 玉岑山慧因高麗華嚴教寺志 [Gazetteer on Huiyin Korea Huayan Teaching Monastery in Yucen Mountain] (The Preface of This Book Was Written in 1627). Chapter six. Compiled in Bing Ding 丁丙, ed. Wulin zhanggu congbian 武林掌故叢編 [Collected Books of Anecdotes from Wulin]. Volume 1. Taipei: Tailian Guofeng Chubanshe and Huawen Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Jojin. 1980. San Tendai Godaisan ki 參天臺五臺山記 [Record on Paying Homage at Mt. Tiantai and Mt. Wutai]. In Bussho kankokai 佛書刊行會. Dai Nihon bukkyō zensho 大日本佛教全書 [Comprehensive Collected Books on Buddhism of Great Japan]. Tokyo: Meicho Fukyūkai. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Eunwu 鄭恩雨. 1994. Hangju Biraebong ui Bul’gyo jogak [Buddhist Sculptures at Feilai Feng in Hangzhou]. Misulsa Yeongu 美術史研究 8: 199–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kamata, Shigeo 鐮田茂雄. 2001. Huayan sansheng xiang de xingcheng 華嚴三聖像的形成 [Froming of the three saint images of Huayan], tr., Zengwen Yang 楊曾文. In Fojiao lishi wenhua 佛教歷史文化 [History and culture of Buddhism]. Edited by Zengwen Yang and Fang Guangchang 方廣錩. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe, pp. 362–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ledderose, Lothar. 2000. The Bureaucracy of Hell. In Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. Chapter 7, Bollingen Series 35: 46. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 163–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sherman. 1994. A History of Far Eastern Art, 5th ed. New York: Harry N. Abram, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie 李静傑. 1999. Lushena fajie tuxiang yanjiu 盧舍那法界圖像研究 [Research on the iconographies of Rocana dharma-realm]. Fojiao wenhua zengkan 佛教文化增刊. Beijing: Fojiao Wenhua Qikanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Lin-ts’an 李霖燦. 1982. Nanzhao Dali guo ziliao zonghe yanjiu 南詔大理國資料綜合研究 [A Study of the Nan-Chao and Ta-Li Kingdoms in Light of Art Materials Found in Various Museums]. Taipei: Guoli Gugong Bowuyuan. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhu 李翥. 1976. Yucen shan Huiyin Gaoli Huayan jiaosi zhi 玉岑山慧因高麗華嚴教寺志 [Gazetteer on Huiyin Korea Huayan teaching monastery in Yucen mountain] (the preface of this book was written in 1627). In Wulin zhanggu congbian 武林掌故叢編 [Collected Books of Anecdotes from Wulin]. Edited by Bing Ding 丁丙 (1832–1899). Taipei: Tailian Guofeng Chubanshe and Huawen Shuju, vol. 1, pp. 496–97. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Changjiu 劉長久. 1997. Anyue shiku yishu 安嶽石窟藝術 [Grotto art in Anyue]. Chengdu: Sichuan Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jinglong 劉景龍, and Chaojie Yang 楊超傑. 1999. Longmen shiku neirong zonglu 龍門石窟內容總錄 [Catalogue of Longmen Grottoes]. Beijing: Zhongguo Dabaike Quanshu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Shiping 羅世平. 1990. Qianfoya Lizhou Bigong ji zaoxiang niandai kao 千佛崖利州畢公及造像年代考 [Research on Duke Bi and Images Commissioned (by Him) at Thousand-Buddha Cliff]. Wenwu 6: 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, Saburo 松原三郎. 1995. Chugoku Bukkyo chokoku shiron 中國佛教雕刻史論 [Discussing the History of Chinese Buddhist Sculptures]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, Amy. 2007. Donors of Longmen: Faith, Politics, and Patronage in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Seiichi, and Toshio Nagahiro. 1951. Yun-Kang: The Buddhist Cave-Temples of the Fifth Century A.D. in North China. Volume 6, Plates, Cave Nine. Kyoto: Jimbunkagaku Kenkyusho, Kyoto University. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka, Ryusaku 長岡龍作, and Yinguang Li 李銀廣. 2022. Riben Qingliang si cang Shijia rulai xiang tainei de xinyang yu shijieguan 日本清涼寺藏釋迦如來像胎內的信仰與世界觀 [The Belief and worldview inside the Sakyamuni Buddha figure collected by Seiryo ji in Japan]. Meishu Daguan 2: 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Osaka Shiritsu Bijutsukan. 1980. Sō Gen no bijutsu 宋元の美術 [The Art of Song and Yuan]. Tokyo: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Yueyou 潛說友. 1970. Xianchun Lin’an zhi 咸淳臨安志 [Gazetteer of Lin’an Written in the Xianchun Reign (1265–1274)]. In Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 中國方志叢書 [Series of Chinese Gazetteers]-Huazhong defang 華中地方 [Central China’s Regions], no. 49. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe youxian gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Shanxi sheng kaogu yanjiu suo 陕西省考古研究所, Famensi bowuguan 法門寺博物館, Baojishi wenwuju 寶雞市文物局, and Fufengxian bowuguan 扶風縣博物館. 2007. Famen si kaogu fajue baogao 法門寺考古發掘報告 [The Archaeological Report of Famen Si]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Swart, Paula. 1987. Buddhist Sculptures at Feilai Feng: A Confrontation of Two Traditions. Orientations 18: 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Diana. 1974. Korean, Chinese, Japanese Sculpture. Tokyo, New York and San Francisco: Kodansha International Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xixiang 王熙祥, and Deren Zeng 曾德仁. 1988. Sichuan Zizhong Chonglongshan moya zaoxiang 四川資中重龍山摩崖造像 [The Cliff images at Chonglong mountain in Zizhong, Sichuan]. Wenwu 8: 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Bolu 熊伯履. 1985. Xiangguo si kao 相國寺考 [Reaserch on Xiangguo monastery]. Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yukio, Lippit. 2005. Engaku-kyo henso zu [A transformation tableaux of the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment]. Kokka 1313: 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo fangzhi congshu 中國方志叢書 [Series of Chinese Gazetteers]. 1970. Huazhong difang 華中地方 [Central China’s Regions]. no. 49. Taipei: Chengwen chubanshe youxian gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo Fojiao wenhau yanjiusuo 中国佛教文化研究所. 1991. Shanxi Fojiao caisu 山西佛教彩塑 [Buddhist color clay sculptures from Shanxi]. Hong Kong: Xianggang Baolian Chansi. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo shiku diaosu quanji bianji weiyuanhui 中国石窟雕塑全集编辑委员会. 2000. Zhongguo shiku diaosu quanji-7-Dazu 中國石窟雕塑全集-7-大足 [The collection of the sculptures from Chinese grottoes-7-Dazu]. Chongqing: Chongqing Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).