Liberation Theology Today: Tasks of Criticism in Interpellation to the Present World

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Why Understand Liberation Theology as a Critical Theory?

Liberation theology is a particularly vivid example of how the purpose and the reflexive structure of critical theory operate. Recall that critical theory intentionally and self-consciously reflects on the particular situation in which it is rooted, in order actively to respond to that situation.

3. Two Processes of Defeat

3.1. The Historical Process of Defeat

3.2. The Disappearance of the Alternative and the Socio-Ontological Defeat

Under conditions of ontological insecurity (…) [i]n the face of an expanding revolutionary crisis, the conventional uses of Christianity were made irrelevant, opening Catholicism itself to being adapted in ways that allowed actors to strategically contend with an increasingly hostile political climate.

Capitalism has enveloped society, absorbing all the conditions of production and reproduction. It is as if the walls of the factory had come crumbling down and the logics that previously functioned in that enclosure had been generalized across the entire time-space continuum.

4. Present and Future of Liberation Theology

4.1. Signs of the Times: New Subjects, Same Struggles

[The] connection between Christianity and progressive politics is not new, although it is often misrecognized […]. The potential of this connection, you could say, is now dormant; but perhaps the present cultural and socio-political crisis we find ourselves in—climate change denial, increased wealth disparity, the rise of the political right, and class, gender, and racial discord—will prove an opportunity for its reemergence.

To understand the social order as artifact is to grasp simultaneously the possibility of acting upon it, (…) To understand the social order also means that social action can take place on the basis of knowledge rather than illusion or ignorance.

The absolute ruling of the market’s logic means cuts in social expenditure and exclusion of the ‘incompetent’ (the poor) and of those who are not necessary any more in the current process of accumulation of capital. […] The sufferings and deaths of the poor, to the extent that they are considered the other side of the coin in the ‘redeeming progress’, are interpreted as necessary sacrifices for this same progress.

4.2. Adornian Optics on the Future of Liberation Theology

Philosophy, which once seemed obsolete, lives on because the moment to realize it was missed. The summary judgment that it had merely interpreted the world (…) becomes a defeatism of reason after the attempt to change the world miscarried (…). Theory cannot prolong the moment its critique depended on. A practice indefinitely delayed is no longer the forum for appeals against self-satisfied speculation […] philosophy is obliged ruthlessly to criticize itself.

If the transition to praxis has so far failed, that should not lead to a desperate escape towards immediate action, but rather to a more ruthless reflection on the relationship between the activity of thought and the objective shaping of reality, on the configuration of praxis and its mediations; that is (…) the task of critical theory.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this article, when speaking of liberation theology, reference will be made to Latin American liberation theology. |

| 2 | It is noteworthy that, during this period, there was a departure from the previously demonstrated support for the reformist proposals of the liberationists by the moderate bishops in Medellín: “The key to this shift at Sucre was the majority of moderate bishops. The moderates had backed the progressive bishops at Medellin. Afterwards, however, some of them began to suspect that they had been hoodwinked by the progressive organizers of Medellin, who appeared to have railroaded their agenda through. More importantly, many moderate bishops became disturbed by the radical consequences that Medellin produced among clergy and laity, especially Christians for Socialism, and so began to back away from Medellin” (Smith 1991, p. 191). |

| 3 | The sense of study is that of criticism. To study reality means to criticise reality: to uncover the antagonisms and contradictions on which reality is based and that reproduce it, discovering the conditions of the “damaged life”(Adorno 2020; Maiso 2022). That is, to unravel the power that shapes society in interrelated discourses and social constructs (Althaus-Reid 2007; Mau 2023). |

| 4 | “Society stays alive, not despite its antagonism, but by means of it” (Adorno 2007, p. 320). “Bourgeois society, as an ‘antagonistic totality’, was only able to maintain itself qua its contradictions” (Bobka and Braunstein 2022, p. 38). |

References

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2007. Negative Dialectics. Translated by Ernst Basch Ashton. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2008. Lectures on Negative Dialectics: Fragments of a Lecture Course 1965/1966. Edited by Rolf Tiedemann. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2012. Messages in a Bottle. In Mapping Ideology. Edited by Slavoj Žižek. London: Verso, pp. 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2017. An Introduction to Dialectics. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2020. Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar Ramírez, Joel D., and Stephan De Beer. 2020. A Practical Theology of Liberation: Mimetic Theory, Liberation Theology and Practical Theology. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 76: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaus-Reid, Marcella. 2003. The Queer God. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Althaus-Reid, Marcella. 2004. From Feminist Theology to Indecent Theology: Readings on Poverty, Sexual Identity and God. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Althaus-Reid, Marcella. 2007. Demythologising Liberation Theology: Reflections on Power, Poverty and Sexuality. In The Cambridge Companion to Liberation Theology, 2nd ed. Edited by Christopher Rowland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 123–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaus-Reid, Marcella. 2010. Indecent Theology: Theological Perversions in Sex, Gender and Politics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Andelson, Robert V., and James M. Dawsey. 1992. From Wasteland to Promised Land: Liberation Theology for a Post-Marxist World. Maryknoll and London: Orbis Books and Shepheard-Walwyn. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Hugo. 1976. Teología desde la praxis de la liberación: Ensayo teológico desde la América dependiente, 2nd ed. Salamanca: Ed. Sígueme. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, Paulo A. N. 2017. Theology Facing Religious Diversity: The Perspective of Latin American Pluralist Theology. Religions 8: 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, Charlotte. 2022. Adorno, the New Reading of Marx, and Methodologies of Critique. In Adorno and Marx: Negative Dialectics and the Critique of Political Economy. Edited by Werner Bonefeld and Chris O’Kane. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Daniel M. 2001. Liberation Theology after the End of History: The Refusal to Cease Suffering. Radical Orthodoxy Series; London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman, Phillip. 1984. The Religious Roots of Rebellion: Christians in Central American Revolutions. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman, Phillip. 1987. Liberation Theology: Essential Facts about the Revolutionary Movement in Latin America and Beyond. London: Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Bingemer, María Clara, and Luiz Carlos Susín. 2016. Caminos de Liberación: Alegrías y Esperanzas Para El Futuro. Madrid: Concilium, p. 364. [Google Scholar]

- Bobka, Nico, and Dirk Braunstein. 2022. Adorno and the Critique of Political Economy. In Adorno and Marx: Negative Dialectics and the Critique of Political Economy. Edited by Werner Bonefeld and Chris O’Kane. Translated by Lars Fischer. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Boff, Clodovis. 1980. Teología de lo político: Sus mediaciones. Verdad e imagen 61. Salamanca: Ed. Sígueme. [Google Scholar]

- Boff, Leonardo. 2006. Ecología: Grito de la Tierra, grito de los pobres. Madrid: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Boff, Leonardo, and Clodovis Boff. 1985. Libertad y liberación, 2nd ed. Salamanca: Ediciones Sígueme. [Google Scholar]

- CELAM. 1979. Puebla: La evangelización en el presente y en el futuro de América Latina. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos. [Google Scholar]

- CELAM. 2007. Documento conclusivo: V Conferencia General del Episcopado Latinoamericano y del Caribe: Aparecida. Lima: CELAM. [Google Scholar]

- CELAM. 2018. 50 Años. Segunda Conferencia General Del Episcopado Latinoamericano. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. [Google Scholar]

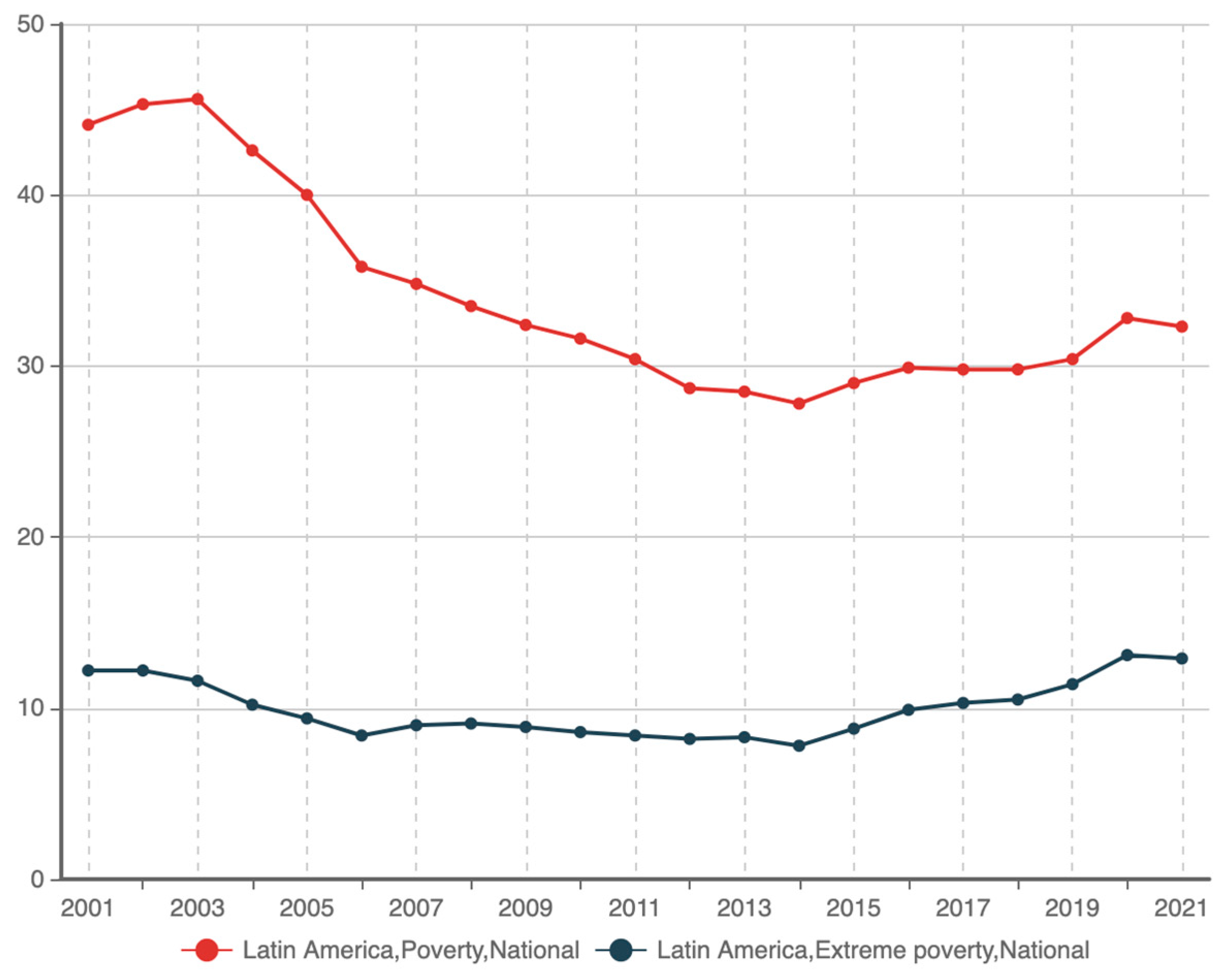

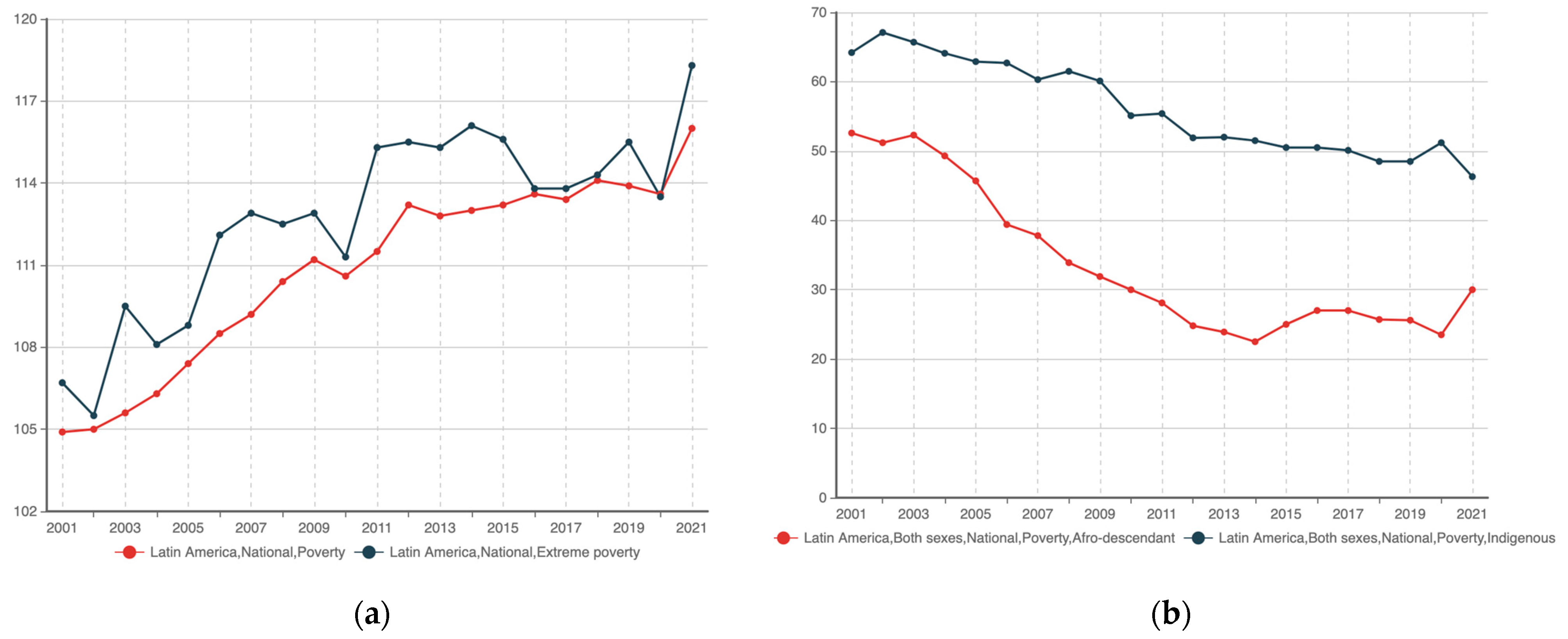

- CEPAL. 2022. CEPALSTATS. Statistical Databases and Publications. 2022. Available online: https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/dashboard.html?lang=en (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Coelho, Allan Da Silva. 2022. Teología y pensamiento crítico. Interview by Luis Martínez Andrade. Jacobin. Available online: https://jacobinlat.com/2022/11/09/existe-una-dimension-teologica-en-el-pensamiento-critico/?fbclid=IwAR3Pgw8HD0bNnlUiVSQB9MfnN_wnbiSFV-9tYEvEQIrLMVybNqjOVL5T9hU (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Comblin, José. 1993. La Iglesia Latinoamericana Desde Puebla a Santo Domingo. In Cambio Social y Pensameniento Cristiano En América Latina. Edited by José Comblin, José Ignacio González Faus and Jon Sobrino. Colección Estructuras y Procesos. Madrid: Trotta, pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Comblin, José, José Ignacio González Faus, and Jon Sobrino, eds. 1993. Cambio Social y Pensameniento Cristiano En América Latina. Colección Estructuras y Procesos. Madrid: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau, Madeleine. 2003. Not Blaming the Pope: The Roots of the Crisis in Brazilian Base Communities. Journal of Church and State 45: 349–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousineau, Madeleine. 2022. The Alleged Decline of Liberation Theology: Natural Death or Attempted Assassination? Religions 13: 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, Debora, and Ivone Gebara. 2022. Esperança Feminista, 1st ed. Rio de Janeiro: Rosa dos Tempos. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique. 1979. De Medellín a Puebla: Una Década de Sangre y Esperanza, 1968–1979, 1st ed.Colección Religión y Cambio Social. México: Edicol: Centro de Estudios Ecuménicos. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique. 2014a. Para una ética de la liberación latinoamericana. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Mexico: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique. 2014b. Para una ética de la liberación latinoamericana. Vol. 2. 2 vols. Mexico: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique. 2017a. Filosofías del Sur: Descolonización y Transmodernidad. Ciudad de México: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique. 2017b. Las metáforas teológicas de Marx. Mexico: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique. 2021. La Filosofía de la Liberación y la Escuela de Frankfurt. In Filosofía de la Liberación: Una antología. Inter Pares. Ciudad de México: Edicionesakal México, pp. 943–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ellacuría, Ignacio. 1991. Veinte Años de Historia En El Salvador (1969–1989): Escritos Políticos, 1st ed. 3 vols. Estructuras y Procesos. San Salvador: UCA Editores, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ellacuría, Ignacio, and Jon Sobrino, eds. 1994a. Mysterium liberationis. Conceptos fundamentales de la Teología de la Liberación. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Estructura y procesos. Madrid: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Ellacuría, Ignacio, and Jon Sobrino, eds. 1994b. Mysterium liberationis: Conceptos fundamentales de la Teología de la Liberación. Vol. 2. 2 vols. Estructura y procesos. Madrid: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Filgueira, Carlos H., and Andrés Peri. 2004. América Latina: Los rostros de la pobreza y sus causas determinantes. Santiago de Chile: Naciones Unidas, CEPAL. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books. Winchester and Washington, DC: Zero Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2006. The End of History and the Last Man: With a New Afterword, 1st ed. [Nachdr.]. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gebara, Ivone. 1999. Longing for Running Water: Ecofeminism and Liberation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gebara, Ivone. 2002. Out of the Depths: Women’s Experience of Evil and Salvation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geffré, Claude, and Gustavo Gutiérrez, eds. 1974. Praxis de liberación y fe cristiana. El testimonio de los teólogos latinoamericanos. Madrid: Concilium. Revista internacional de teología, p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Joy. 1996. Liberation Theology as Critical Theory: The Notion of the “Privileged Perspective”. Philosophy & Social Criticism 22: 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouzoulis, Giorgos. 2023. What Do Indebted Employees Do? Financialisation and the Decline of Industrial Action. Industrial Relations Journal 54: 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, John. 2009. False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism, New ed. London: Granta. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Gustavo. 1972. Teología de La Liberación: Perspectivas. Verdad e Imagen 30. Salamanca: Ediciones Sígueme. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Gustavo. 1988. A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, David. 1989. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Oxford and Cambridge: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, David. 2019. Spaces of Global Capitalism. London and New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, Michael. 2012. An Introduction to the Three Volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital. New York: Monthly Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkelammert, Franz J. 1995. Cultura de la esperanza y sociedad sin exclusión. Colección economía-teología. San José: Ed. DEI [u.a.]. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkelammert, Franz J. 2018. Totalitarismo Del Mercado: El Mercado Capitalista Como Ser Supremo. Akal/Inter Pares. Serie Poscolonial. Ciudad de México: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkelammert, Franz J. 2021. La crítica de las ideologías frente a la crítica de la religión volver a Marx trascendiéndolo, 1st ed. Ciudad de Buenos Aires: CLACSO. [Google Scholar]

- Horkheimer, Max. 2000. Teoría tradicional y teoría política. Edited by Jacobo Muñoz. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Horkheimer, Max, and Th W. Adorno. 2007. Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Translated by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr. Cultural Memory in the Present. Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, Fredric. 2007. Late Marxism: Adorno, or, The Persistence of the Dialectic. Radical Thinkers 18. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Lamola, Malesela. 2018. Marx, the Praxis of Liberation Theology, and the Bane of Religious Epistemology. Religions 9: 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lernoux, Penny. 1982. Cry of the People: The Struggle for Human Rights in Latin America--The Catholic Church in Conflict with U.S. Policy. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lernoux, Penny. 1990. People of God: The Struggle for World Catholicism. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- López Trujillo, Alfonso. 1980. De Medellín a Puebla. Bibloteca de Autores Cristianos 417. Madrid: Editorial Católica. [Google Scholar]

- Löwy, Michael. 1996. The War of Gods: Religion and Politics in Latin America. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Löwy, Michael. 2008. ‘Liberation-Theology Marxism’. In Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism. Edited by Jacques Bidet and Eustache Kouvélakis. Historical Materialism, v. 16. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 225–32. [Google Scholar]

- Maiso, Jordi. 2022. Desde la vida dañada: La teoría crítica de Theodor W. Adorno. Tres Cantos and Madrid: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1981. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Ben Fowkes. 3 vols. Penguin Classics. New York: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. 2010. Marx and Engels Collected Work. Marx and Engels 1845–47. 50 vols. London: Lawrence & Wishart Electric Book, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mau, Søren. 2023. Mute Compulsion a Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Álvarez, Carlos. 2016. La Teología de La Liberación En Contexto Posmoderno En América Latina y El Caribe. Perspectiva Teológica 48: 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Álvarez, Carlos, and Stefanie Knauss. 2019. Teologías Queer: Devenir El Cuerpo Queer de Cristo. Madrid: Concilium. Revista internacional de teología, p. 383. [Google Scholar]

- Neut Aguayo, Sebastián, and Verónica Soto Pimentel. 2014. Marx y Horkheimer En Una Obra Clave de La Teología de La Liberación: La Teología de Lo Político de C. Boff. Veritas 31: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, Ivan. 2004. The Future of Liberation Theology: An Argument and Manifesto. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Ratzinger, Joseph. 1986. Instrucción sobre algunos aspectos de la teología de la liberación: Instrucciones sobre libertad cristiana y liberación. Madrid: Biblioteca Autores Cristianos. [Google Scholar]

- Ratzinger, Joseph, and Vittorio Messori. 1985. Rapporto Sulla Fede. Interviste Verità; 1. Cinisello Balsamo, Milano: Edizioni paoline. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, Jean-Pierre. 2017. The Bible, Religious Storytelling, and Revolution: The Case of Solentiname, Nicaragua. Critical Research on Religion 5: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Jean-Pierre. 2020. Elective Affinities between Sandinismo (as Socialist Idea) and Liberation Theology in the Nicaraguan Revolution. Critical Research on Religion 8: 153–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannone, Juan Carlos. 2009. La Filosofía de La Liberación: Historia, Características, Vigencia Actual. Teología y Vida 50: 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannone, Juan Carlos. 2019a. Influjo de Gaudium et Spes En La Problemática de La Evangelización de La Cultura En América Latina. Evangelización, Liberación y Cultura Popular. Stromata 40: 87–103. Available online: https://revistas.bibdigital.uccor.edu.ar/index.php/STRO/article/view/2628 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Scannone, Juan Carlos. 2019b. La Teología de La Liberación. Caracterización, Corrientes, Etapas. Stromata 38: 3–40. Available online: https://revistas.bibdigital.uccor.edu.ar/index.php/STRO/article/view/2553 (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 2008. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, 1st ed. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Thought. [Google Scholar]

- Second Vatican Council. 1965. Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World: Gaudium et Spes. Boston: Pauline Books&Media. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian. 1991. The Emergence of Liberation Theology: Radical Religion and Social Movement Theory. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrino, Jon. 1991. Jesucristo Liberador: Lectura Histórico-Teológica de Jesús de Nazaret. Colección Estructuras y Procesos. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrino, Jon. 2007a. Fuera de Los Pobres No Hay Salvación: Pequeños Ensayos Utópico-Proféticos. Estructuras y Procesos. Serie Religión. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Sobrino, Jon. 2007b. La fe en Jesucristo: Ensayo desde las víctimas. Madrid: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Jung Mo. 2007. Desire, Market and Religion. Reclaiming Liberation Theology. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Jung Mo. 2011. Greed, Desire and Theology. The Ecumenical Review 63: 251–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Jung Mo. 2015. El Pobre Después de La Teología de La Liberación. Concilium. Revista Internacional de Teología 361: 79–90. Available online: https://www.revistaconcilium.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/pdf/361.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Sung, Jung Mo. 2018a. Idolatria do dinheiro e direitos humanos: Uma crítica teológica do novo mito do capitalismo. São Paulo: Paulus. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Jung Mo. 2018b. Religion, Human Rights, and Neo-Liberalism in a Post-Humanist Era. The Ecumenical Review 70: 118–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Charles. 2004. Modern Social Imaginaries. Public Planet Books. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Traverso, Enzo. 2021. Left-Wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory. Paperback edition. New Directions in Critical Theory. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trigo, Pedro. 2005. ¿Ha Muerto La Teología de La Liberación? La Realidad Actual y Sus Causas (I). Revista Latinoamericana de Teología 22: 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Denys. 2007. Marxism, Liberation Theology and the Way of Negation. In The Cambridge Companion to Liberation Theology, 2nd ed. Edited by Christopher Rowland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 229–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Threatened/Defamed | Arrested | Tortured | Killed | Kidnapped/Disappeared | Exiled/Expelled | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bishops | 60 | 35 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Priests | 118 | 485 | 46 | 41 | 11 | 253 |

| Religious | 18 | 44 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 26 |

| Laity | 12 | 371 | 18 | 33 | 21 | 6 |

| TOTAL | 208 | 935 | 73 | 79 | 37 | 288 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Recio Huetos, J. Liberation Theology Today: Tasks of Criticism in Interpellation to the Present World. Religions 2023, 14, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040557

Recio Huetos J. Liberation Theology Today: Tasks of Criticism in Interpellation to the Present World. Religions. 2023; 14(4):557. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040557

Chicago/Turabian StyleRecio Huetos, Javier. 2023. "Liberation Theology Today: Tasks of Criticism in Interpellation to the Present World" Religions 14, no. 4: 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040557

APA StyleRecio Huetos, J. (2023). Liberation Theology Today: Tasks of Criticism in Interpellation to the Present World. Religions, 14(4), 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040557