1. Introduction

Religious disaffiliation—the process of leaving the religion in which one was raised—is becoming increasingly more common in the United States. This is reflected in the 2012 General Social Survey, where 75% of American adults who claim no religious affiliation report having been raised in a religion (

Fenelon and Danielsen 2016). In addition, during the twenty-year timespan between 1991 and 2011, the percentage of religiously unaffiliated Americans has doubled (

Smith et al. 2011). Consequently, religious disaffiliation has become an important topic to study, with researchers attempting to understand the trends and causes associated with leaving religion.

It has been documented in the literature that among those who disaffiliate from religion, LGBTQ+

1 individuals disaffiliate at a higher rate than heterosexual individuals (

Scheitle and Wolf 2017;

Woodell and Schwadel 2020). In a study focusing only on Christian denominations,

Scheitle and Wolf (

2017) found that bisexual people were significantly more likely than heterosexuals to disaffiliate from religion. Similarly, in a large study examining over 13,000 participants,

Woodell and Schwadel (

2020) describe that individuals with same-sex attraction were more likely to disaffiliate from religion. Additionally, in a sample of 373 lesbian, gay, and bisexual respondents,

Sherry et al. (

2010) found that over 40% reported rejecting religion/god, while the rate of identifying as “not at all” religious in the general population around that same time was reported as 23% (

Shannon-Missal 2013).

One possible reason for the disproportionate rate of disaffiliation in the LGBTQ+ population compared to the general population is that many mainstream religions express views and stances that are anti-LGBTQ+, forbidding lifestyles and behaviors associated with being a member of the LGBTQ+ community. Because LGBTQ+ people are often raised in environments where they are exposed to stigmatizing, non-affirming, and even hateful messages, they may experience conflict between their LGBTQ+ identity and their religious identity, leading many to disaffiliate from religion (

Beagan and Hattie 2014;

Dehlin et al. 2014;

Hattie and Beagan 2013).

A religious population that has not been well-studied in the field of LGBTQ+ religious disaffiliation is the Orthodox Jewish community, primarily due to the insularity of the population. Orthodox Jewish people live in communities that are often separated from secular ways of life, with multiple areas such as dress and food having well-defined religious rules. Importantly, there is a shared consensus among religious Jews that, to be considered Orthodox, minimally, one must follow the laws of Shabbos

2, Kosher

3, and family purity

4 (

Greenberg 1983).

Despite these commonalities, Orthodox Judaism has its own spectrum, with ultra-Orthodoxy or Haredism (i.e., Hasidic, Chabad, and Yeshivish) on one end and Modern Orthodoxy on the other end. Individuals in Haredi communities generally insulate from secular society and its way of life, with many Hasidim, in particular, having inadequate mastery of the English language, lacking in basic education, and having limited vocational skills (

Berger 2015;

Partlan et al. 2017), most often due to the prioritization of religious study over traditional secular study. In contrast, those in Modern Orthodox communities balance religious Orthodoxy and secular modernity.

In general, Orthodox Jewish communities traditionally do not welcome LGBTQ+ people. Homosexuality is strictly prohibited according to religious law, and some have even described real-life situations where parents of LGBTQ+ children performed mourning rituals on their child coming out as gay (

Itzhaky and Kissil 2015). In a 2015 study interviewing 22 closeted gay Orthodox Jewish men, many described feelings of guilt, shame, and self-hatred, not only about being gay, but also about lying to their families about their sexual identity. Many men in this sample also reported contemplating or attempting suicide. Due to both the insular nature of the community and the attitudes against LGBTQ+ people, many individuals reported keeping their identity a secret to avoid not only social consequences but also financial difficulties that would result from losing family and community support (

Itzhaky and Kissil 2015). Thus, in order to explore the perspectives on homosexuality further, it is useful to distinguish the doctrine as understood and practiced by the two major streams of Orthodox Judaism—Haredi/ultra-Orthodox and Modern Orthodox groups.

In ultra-Orthodox or Haredi Judaism, separation from the secular world creates an insular environment with limited exposure to secular ideas, such as those that acknowledge LGBTQ+ identities. According to Haredi religious doctrine, the rules dictated by the

Torah, the law of God, are considered immutable and expected to be followed strictly (

Goldberg and Rayner 1989). As such, ultra-Orthodox religious doctrine rejects homosexuality in accordance with Levitical laws that explicitly prohibit homosexual intercourse between men. In fact, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, the most important Jewish legal authority of the twentieth century, firmly upheld homosexual intercourse as forbidden, based on the principle that an underlying homosexual natural inclination is not possible, rather only the acts that constitute the

practice of homosexuality (see

Irshai 2018).

In recent years, however, in response to pressures from the outside world, the Modern Orthodox movement has progressed towards acknowledging and accepting LGBTQ+ identities and individuals. Although the Modern Orthodox sect, like the Haredi or ultra-Orthodox, recognizes homosexual activity as strictly banned by the Torah, there has recently been a shift to promote the inclusion and engagement of gay individuals in the religious community. A representative viewpoint comes from Rabbi Yuval Sherlo, one of many Modern Orthodox rabbis who recognizes the concept of a homosexual nature or identity, and advises against excluding homosexual individuals from participation in the community and synagogue (

Schweidel 2006, as cited in

Slomowitz and Feit 2015). Additionally, social pressure to integrate contemporary scientific knowledge with respect to sexual orientation and gender identity (

Slomowitz and Feit 2015) prompted the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA) to reverse their position in which they formerly accepted conversion therapies. Though this is among the first steps by some members of the Modern Orthodox community and its leadership to acknowledge LGBTQ+ individuals, in many circles they have nonetheless not yet been fully integrated.

Despite these differences between Haredi and Modern Orthodox perspectives in relating to the LGBTQ+ community, it is important to emphasize that both communities prohibit homosexual intercourse. As such, disaffiliation from either community for reasons pertaining to homosexuality or homosexual activity may be comparable. However, increased exposure of Modern Orthodox individuals to the secular world may provide the much-needed language for LGBTQ+ community members to understand or classify their identities.

The possibility of delayed LGBTQ+ identification due to the lack of discussion, language, and exposure of LGBTQ+ people and topics in Orthodox Jewish communities is worthy of note. It has been documented in previous qualitative research that being exposed to and discussing the narrative of LGBTQ+ people is important to the development and naming of a transgender identity (

Cashore and Tuason 2009;

Devor 2004;

Gagné and Tewksbury 1999;

Levitt and Ippolito 2014) and a bisexual identity (

Cashore and Tuason 2009). Conversely, when LGBTQ+ people are not exposed to others who are similar and can give them a language to describe themselves, it has been reported that they feel isolated, unable to recognize/name their own experiences, and a sense of confusion around identity (

Cashore and Tuason 2009;

Devor 2004;

Gagné and Tewksbury 1999;

Levitt and Ippolito 2014). However, the language that does exist around same-sex attraction and gender diversity is often stigmatizing and conveys deviance, which contributes to feelings of alienation, stress, and loneliness (

Gagné and Tewksbury 1999). In the context of ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities, where discussion of LGBTQ+ people and access to the outside world is limited, there may be individuals within the community who later identify as LGBTQ+ when outside the community, but prior to disaffiliation would only feel a sense of stigma, isolation, and stress without recognizing and naming an LGBTQ+ identity.

Taken together, these findings suggest that sexual identity and Orthodox Judaism’s lack of acceptance of homosexuality could be contributors to disaffiliation for Orthodox Jewish LGBTQ+ people. However, in the current research literature, there is a lack of documented evidence investigating the reported reasons for disaffiliation within the LGBTQ+ subpopulation of the Orthodox Jewish community.

In line with this, the goal of the current study was to analyze the open-ended responses of participants drawn from a larger study (N = 387) who identified as LGBTQ+ (N = 119) to questions related to the causes and initial triggers for their disaffiliation from Orthodox Judaism and to determine if attributions for leaving involved their sexual identity and/or the religion’s negative views on homosexuality. We believe this study can enhance the literature by helping to clarify the relationship of LGBTQ+ identity to disaffiliation, specifically in an understudied population of Orthodox Jewish people. Furthermore, our study will help expand on the extent to which LGBTQ+ identity contributes to the decision of an individual to disaffiliate from their religion, with a focus on whether LGBTQ+ identity is a deciding factor, or whether certain demographics such as age and gender determine the likelihood that LGBTQ+ identity is reported as a reason for disaffiliation.

3. Results

In our sample, a total of 119 survey respondents identified their sexual orientation as falling under the LGBTQ+ umbrella. While most respondents chose one of the available multiple-choice options, gay, bisexual, queer, asexual, some individuals chose a combination of responses (designated as multiple), and others entered a custom response into the Other field, and thus were designated as Other. Individuals who provided open-ended responses that were uncategorizable (i.e., “Cannot recall”), were removed from this analysis, resulting in a total sample size of 117. See

Table 2 for complete demographic information for this sample.

Overall, participants were significantly more likely not to cite sexual identity and/or negative religious views on homosexuality as a cause or initial trigger for disaffiliation, x2(1) = 72.6, p < 0.001. Specifically, of the total 117 LGBTQ+ respondents in this sample, only 18 individuals (15.38%) provided responses indicating that either the initial trigger that started their disaffiliation journey or the cause of their disaffiliation included their sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality.

In order to examine whether the composition of this small subgroup of individuals (those who did attribute their disaffiliation to sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality) was significantly different from the rest of the LGBTQ+ group (those who did not attribute their disaffiliation to sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality) by gender, community identity, and specific sexual orientation, chi-squared tests of independence were conducted for each factor by response type. Response type in all cases was coded as yes/no, where “yes” referred to those individuals who identified sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality as a cause or initial trigger of their disaffiliation, and “no” indicated that sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality was not indicated as a factor in disaffiliation.

Chi-square tests of independence determined that gender (x2(2) = 0.236, p = 0.889), community identity (x2(5) = 6.92, p = 0.227), and sexual orientation (x2(5) = 7.09, p = 0.214) were all independent of response status, indicating that the composition of the 18-person “yes” subgroup was not significantly different from the rest of the sample along these three factors.

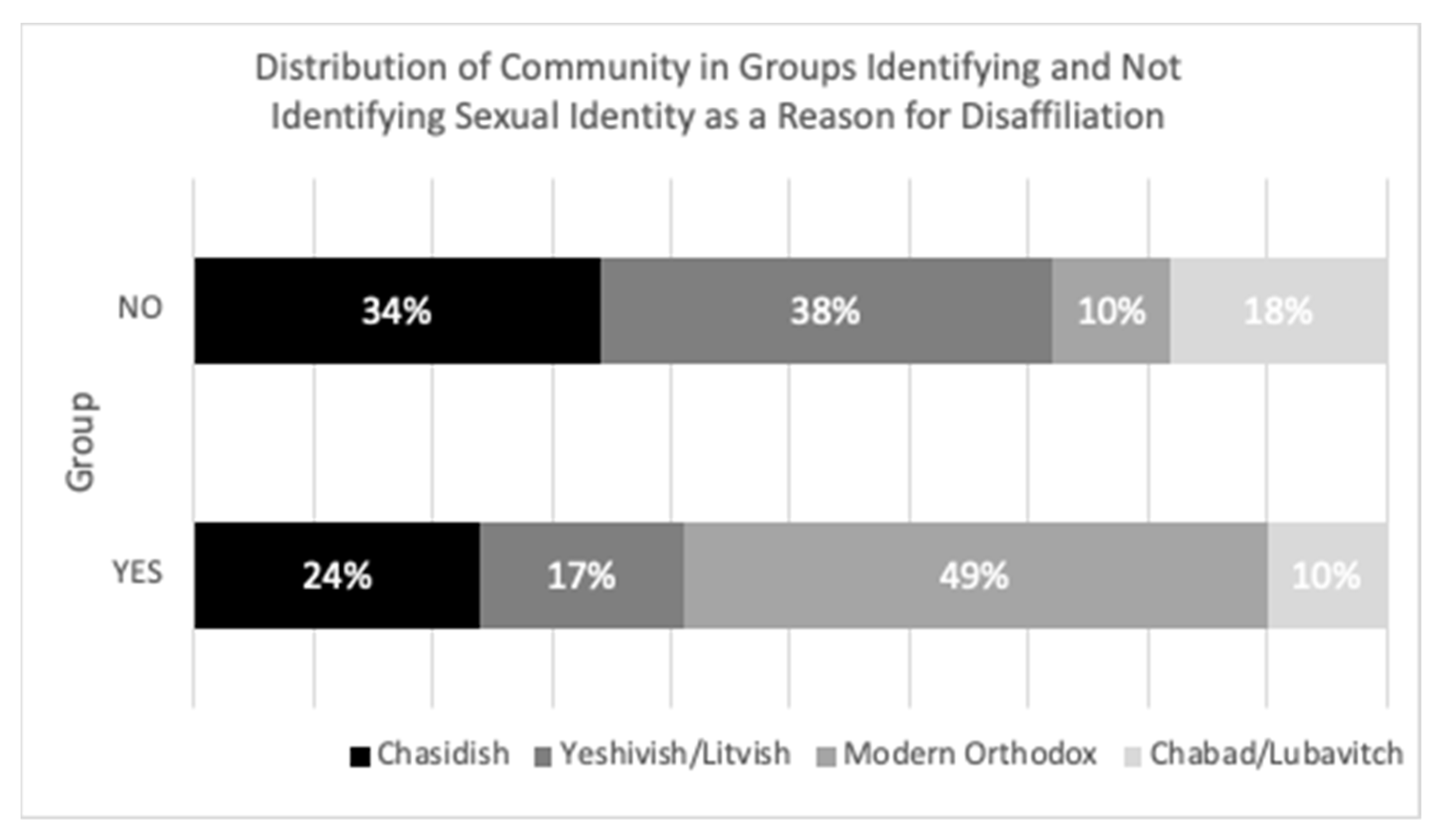

While not significant, it is interesting to note that there was an increase in the proportion of Modern Orthodox individuals and a decrease in the proportion of all other community identities in the group identifying sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality as a contributor to disaffiliation compared to the group that did not report that factor as a contributor (

Figure 1: top). When looking at the proportion of each community group that reported sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality as contributors to disaffiliation, the community with the largest proportion of individuals identifying this factor as a contributor is the Modern Orthodox group (

Figure 1: bottom).

For those individuals who did not cite sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality as contributors to disaffiliation, we examined the most frequently reported causes and triggers. This sample reported triggers and causes of disaffiliation similar to those reported in the larger study of 387 disaffiliates, which included 268 individuals who did not identify as LGBTQ+.

Figure 2 displays the proportion of LGBTQ+ individuals citing each of a variety of categories as triggers and causes of their disaffiliation.

4. Discussion

The purpose of our investigation was to determine whether there was a relationship between sexual identity and/or Orthodoxy’s negative views on homosexuality and disaffiliation from Orthodox Judaism in a sample of LGBTQ+ individuals. Only 15.38% of our sample of individuals identifying as LGBTQ+ listed their sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality as a cause for their disaffiliation. The relative absence of sexual identity and/or religious views on homosexuality as a reason for disaffiliation in LGBTQ+ respondents’ narratives was unexpected, as research in this field consistently reports that LGBTQ+ people disaffiliate at a higher rate than non-LGBTQ+ individuals (

Scheitle and Wolf 2017;

Woodell and Schwadel 2020), which may indicate that the circumstances around identifying as LGBTQ+ are related to disaffiliation. Thus, though it may be that our finding suggests that Orthodox Jewish LGBTQ+ individuals follow a different disaffiliation path than other religions, there may be an alternative explanation for this surprising result.

A particularly interesting finding emerging from our data is that, of the community identities reported in the sample, individuals who identified as Modern Orthodox were more likely than other groups in our sample (i.e., Hasidic, Chabad, and Yeshivish) to attribute their disaffiliation to sexual identity and/or Orthodox Judaism’s negative views on homosexuality. In contrast to ultra-Orthodoxy or Haredism—communities that, to varying degrees, insulate from modern secular society and its way of life—Modern Orthodoxy includes communities and individuals that synthesize or balance religious Orthodoxy and secular modernity. Relative to ultra-Orthodoxy or Haredism, Modern Orthodoxy is far less religiously stringent and much more integrated into modern society and culture (e.g., comprehensive basic and tertiary secular education, autonomous or self-selected marriage, greater degree of gender equality, lower birth rates, less stringent dress code, and greater acceptance of science), covering a wider range of religious practices and religious ways of life. Furthermore, Modern Orthodox individuals appear to be more accepting of homosexuality in general. In a 2013 poll, only 38% of Modern Orthodox individuals asserted that homosexuality should be discouraged, as compared to 70% of Haredi individuals (

Pew Research Center 2013;

Slomowitz and Feit 2015).

The lack of language surrounding sexual identity in ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities may have contributed to our findings. This may be due to the fact that there is little secular education and sex education in these communities, including discussions of LGBTQ+ people and related topics (

Claude Klein 1994;

Partlan et al. 2017). Additionally, many models of homosexual identity formation identify a series of important developmental milestones, including becoming aware of same-sex attractions, questioning sexual orientations, and self-identifying as LGBTQ+ (

Cass 1979;

Devor 2004;

Hall et al. 2021;

Savin-Williams 2011), all of which may be impacted by growing up within these communities. Previous research has noted how important exposure (i.e., media), language, and community are to LGBTQ+ identity formation (

Cashore and Tuason 2009;

Gagné and Tewksbury 1999;

Gomillion and Giuliano 2011;

Levitt and Ippolito 2014), and that often LGBTQ+ people, especially transgender individuals, lack language that accurately describes their internal sense of sex and gender, which results in negative feelings of stress, isolation, and discord, but often without a label for their identity. Lack of exposure or awareness of the existence of a particular group renders an individual unable to identify themselves as belonging to that group (

Lofland 2002). Thus, we believe that part of why we found such a surprisingly low proportion of respondents attributing their LGBTQ+ identity to their decision to disaffiliate is that, due to a lack of exposure to and language around LGBTQ+ people, these respondents were unable to recognize and name an LGBTQ+ identity until after their disaffiliation. This explanation may also account for a greater attribution of sexual identity to disaffiliation among the Modern Orthodox, a religious subgroup with greater general exposure to the secular world than ultra-Orthodox groups.

In summary, the small percentage of our sample who did attribute sexual identity to their disaffiliation was comprised of more Modern Orthodox individuals, as opposed to the other community identities in our sample. This finding may align with the explanation that lack of exposure to LGBTQ+ concepts and language hinders one’s ability to identify as LGBTQ+ while still in the community, as Modern Orthodox Jewish individuals, compared to the other, more insular groups, have greater exposure and access to the secular world, including LGBTQ+ language and concepts. Though one might question why individuals from a Modern Orthodox society that is more exposed to a secular world might still disaffiliate due to their sexual identity, it is important to note that homosexuality is still forbidden and many LGBTQ+ individuals are not accepted, even in this less insular community.

Our study had a few limitations. While our sample was large, it may not be entirely representative. The majority of our sample was drawn from the United States, and specifically New York State, which may not be generalizable to the entire population of Orthodox Jewish sexual minorities. Additionally, our study questionnaire was administered online and presented in English, thus targeting only English-speaking individuals with internet access. This is a relevant limitation to note because many ultra-Orthodox Jewish people, more specifically Hasidic or ex-Hasidic individuals, are not native English speakers and may not receive educational instruction in English nor have access to the internet (

Partlan et al. 2017). Another limitation is the possibility of bias in retrospective data collection. There may be a variety of reasons for which an individual may restructure their narrative in retrospect to center their disaffiliation on some factor other than their sexual identity. One possibility, for example, may be to avoid the negative connotation of being “pushed out” or feeling ostracized by the community, in favor of a narrative in which disaffiliates have the ability to reject the community instead of the other way around.

Further studies should attempt to incorporate a larger transgender and gender variant population, as our sample contained only seven individuals who identified as transgender or gender non-conforming, and transgender and non-binary people’s disaffiliation and experiences may not mirror those of cisgender sexual minorities. Furthermore, in order to help clarify the nuances of LGBTQ+ identity and how it relates to disaffiliation, we suggest that future research examine questions of whether respondents identified as LGBTQ+ before or after disaffiliating, if they were openly LGBTQ+ before disaffiliating, if they were familiar with LGBTQ+ language and concepts while still in the community, and to what degree they were exposed to anti-LGBTQ+ attitudes in the community. This kind of information may provide insight into potential moderators of the sexual identity–disaffiliation relationship in Orthodox Judaism.