1. Introduction

Faith activities are held in a certain time and space, and exert their influence on reality through space–time units. In the past few decades, many achievements have been made in the spatial study of religions, and scholars have applied multidisciplinary methods to solve such problems. However, most of these studies focus on specific religious sites, such as temples, ancestral halls, memorials, and other spaces. The religious activities held in people’s daily lives and secular spaces are seldom addressed due to the lack of consideration of everyday spatial practices. However, the cognition of the divinity of the gods is often formed, strengthened, and transmitted through daily practice.

Here, we attempt to provide a special case study of the spatial study of religions through the analysis of the sacrificial activities of one of the auspicious gods in Chinese folk belief—Xishen (喜神, the God of Happiness)—and to establish a link between people’s cognition of their belief and spatial orientation. The main purpose of this paper is to discuss the presence of religion in a secular context.

Xishen is one of the secular gods widely known and believed in by Chinese people. He has no clear image or specific birthday, and there is no place of worship dedicated to Him. Although He has no specific religious space, there are clear directions and time requirements for the worship of Xishen. In the almanac of the Chinese lunar calendar, “the Direction of Xishen” (喜神方, Xishen Fang) is marked every day in a prominent position, reminding people to make daily offerings and direct wishes to Him. During the Spring Festival and important celebrations such as weddings, the starting and ending times and orientations of important activities in the ceremony are also arranged around the direction of Xishen.

The worship of Xishen is not constrained by a specific religious space; the orientation and timing of worship are determined based on the subjects themselves, who participate in the religious activities. The direction of Xishen in the almanac is not fixed, and this fluidity also gives flexibility and adjustability to the relationship between people and Him. Xishen is not in a static and sacred religious space. He can come to people through activities such as “Welcoming Xishen” (迎喜神), the “Xishen Fang Pageant” (游喜神方), that involves celebrating in the direction where Xishen is located to ask for blessings, and “Allaying Xishen” (送喜神, meaning to send off Xishen after the worship). Taking the spatial orientation that people can perceive and measure as a guide, we can say that this is close to daily life; it also shortens the spiritual distance with people and is closely related to people’s practical activities.

In the relevant practice of “the Direction of Xishen”, it can be seen that under the influence of this awareness, people make obvious active choices and have preferences regarding the direction in their living space. This is not necessarily based on having (in other words, understanding and mastering) knowledge, but is rather an intuitive choice to welcome “good luck” and avoid “ill luck”. This choice is not only based on the actual practicalities of running a living space or personal career, and sometimes even disrupts or delays people’s plans, but it can satisfy their expectations of the direction of good luck. Through some methods that can show their concern about “the Direction of Xishen”, people believe that they bring happiness into their living space and lives. The good and ill luck metaphors in traditional thought directly affect people’s attitudes towards their living space and their choice of travel orientation and sacrificial orientation. At the very least, when they know the direction of Xishen, people often choose to carry out worship in this direction and regard the people or things they encounter from this direction as being auspicious.

This research focuses on the folk belief in Xishen, and attempts to examine the importance of space in the Chinese folk belief system and why it appeared through the two-way dimension of diachronic retrospective and synchronic analysis. We will address the following three topics:

How does Xishen belief express the unique religious concept of the Chinese people?

How is “the Direction of Xishen” rooted in natural and historical factors, and finally formed in the unique framework of the relationship between humans and God in Chinese folklore?

How is “the Direction of Xishen” reconstructed and generalized as an integral part of contemporary values and implemented in the level of individual spatial perception and physical experience of the public, participating in shaping collective memory and identity.

The topic of folk religion in China has long been a concern for scholars from various disciplines at home and abroad. Wu Bing’an believes that “in the economic and social life, there are many phenomena of faith…they are customs and practices of folk thinking concepts that have been continuously inherited and mutated from the original beliefs of human primitive thinking. These customs and conventions of thinking concepts have been believed by people, and even become an important factor that dominates people’s material and spiritual life.” (

Wu 1985, p. 238). He summarized the differences between folk beliefs and religions, starting from “whether there is a fixed belief organization?”, “whether it forms a complete belief system?”, “whether there is direct utilitarianism?”, “whether there is obvious diversity?”, and six other aspects, and clearly expresses the view that folk beliefs cannot be equated with traditional religions (

Wu 1985). Anthropologist Li Yiyuan summarized the content of folk beliefs by way of examples: “Including ancestor worship, god worship… agricultural rituals, divination, etc., and even the space-time cosmology is also part of our religious concepts.” (

Li 2004, p. 116). He believed that Chinese folk beliefs are “diffused religions”, and that the beliefs, rituals, and religious activities are closely mixed with daily life and diffused as a part of daily life (

Li 2004). Religious scholar Jin Ze believed that “in China, folk religion is not only a historical phenomenon but a ‘living’ culture as well” (

Jin 2006). Folk belief is rooted in the folk; it is a phenomenon that has existed for a long time, and has a strong mass basis; its importance cannot be ignored in the development of Chinese society and culture. He believed that the state should think about what strategies to adopt to manage folk beliefs at the level of social control and make them play an active role.

Adam Y. Chau focused on the folk cultural revivalism phenomenon during the reform era (from the early 1980s onward) of the People’s Republic of China with a critical view. (

Chau 2006) In his research, Chau tried to answer “how it is possible that popular religion has revived in the past twenty or so years.” The section about the “Modalities of ‘Doing Religion’ in Chinese Culture” in his research provides a very practical and effective conceptual tool for the study of Chinese folk religion. His case study has shown that “to survive and thrive, temple associations and temple bosses have to negotiate with different local state agencies and accommodate official rent-seeking so as to secure different kinds of official endorsement and protection.” (

Chau 2005). Chen Chunsheng focused on the folk beliefs in rural South China during the Ming and Qing Dynasties in

Faith and Order. In this research, he presented the changes in the complex relationship between the local and the central government, folk beliefs, and rural social systems. Chen pointed out that the reason why the custom of folk beliefs will endure is that it is rooted in the daily life of ordinary people. It comes from relatively “non-institutionalized” families and communities, so it is therefore difficult to be monopolized by a few people from the upper classes; it has been able to survive many dynastic changes and still be able to recover after being hit (

Chen 2019).

These researchers accurately summarize the characteristics of Chinese folk beliefs: routine, popular, and non-institutionalized. However, it should be noted that the social culture formed in the long-term historical process contains complex and interactive relationships between local and central, folk and official factors. It reminds us that, while paying attention to the characteristics of folk beliefs, the influence of other cultural elements of society on folk beliefs cannot be ignored. This can be seen in people’s admiration for the southerly orientation of Xishen.

The earliest international research on Chinese folk religions was from the group of European missionaries who entered China in the 19th century. Among them, French missionary Henri Doré not only preached in the rural areas of Shanghai, Anhui, and Jiangsu for more than 30 years, but also went deep into the local fields to carefully observe and record the daily life of ordinary people. His large number of ethnographic materials finally completed the 18-volume French version of the masterpiece

Recherches sur les superstitions en Chine. Japanese scholar Watanabe suggested that folk religion is a religion compiled in the context of people’s lives and used in life. Folk religion serves the overall purpose of life. Watanabe divided the folk religious concepts of the Han people into gods, ghosts, and ancestors, and further explained that the gods of the Han people have their own ranks and positions, that constitute a bureaucratic central government, and the temples in the world are the residences of the gods: external institutions through which they “respond to the various demands of the people, monitor their behavior, and determine their good and ill luck.” (

Watanabe and Zhou 1998, p. 19).

Many scholars have noticed the secularity, practicality, and bureaucratization of Chinese folk religion, but they generally pay little attention to the space concept shown in religion and the relationship between orientation and luck. In fact, in the practical field of folk beliefs, grasping the appropriate space and time is the primary prerequisite for the smooth holding of religious rituals, which is particularly evident in the worship of the Xishen. This shows that the spatial study of folk religion and the ideas about people’s concept of space-time can provide necessary materials for the study of Chinese folk beliefs and supplement new perspectives and research approaches.

Besides, the spatial study has reference significance for this research. Sociologists have long ignored spatial issues. Anthony Giddens pointed out that, “neither time nor space have been incorporated into the center of social theory; rather, they are ordinarily treated more as ‘environments’ in which social conduct is enacted.” (

Giddens 1979, p. 202). Traditional social research usually regarded space as an external static “container” of social activities and did not pay attention to theoretical issues related to space. Georg Simmel compared space to language in

Sociology: Inquiries into the Construction of Social Forms. He believed that “space remains always the form, in itself ineffectual, in whose modifications the real energies are indeed revealed, but only in the way language expresses thought processes that proceed certainly

in words but not

through words.” (

Simmel et al. 2009, pp. 543–44).

Researchers sometimes underestimate the meaning and function of space itself, ignoring the facts that specific spaces and orientations are the embodiment of certain ways of religious thinking. By showing how “the Direction of Xishen” participates in folk history and contemporary practice, this research attempts to confirm that space is not just a physical space that carries people’s belief practices, but can itself can offer valuable information about people’s beliefs and culture.

2. The Invisibility of Xishen: The Faith in Xishen in Traditional Space—Time Knowledge

People in ancient times believed that good and ill luck were dominated by the gods. Many scholars think that Xishen (God of Happiness) does not have a fixed and unified image because happiness cannot be expressed in a concrete, specific way. We know that Caishen (财神) is the god of wealth, and people always turn to Shouxing (寿星) to pray for longevity. These gods are all created to achieve some specific goals. However, nobody can define “happiness” or give it a definition.

Émile Durkheim suggested that “all known religious beliefs display a common feature: They presuppose a classification of the real or ideal things that men conceive of into two classes—two opposite genera—that are widely designated by two distinct terms, which the words profane and sacred translate fairly well.” (

Durkheim and Fields 1995, p. 34). The relation between profane and sacred is “absolute” heterogeneity, which means they are as “two worlds with nothing in common” (

Durkheim and Fields 1995, p. 36). He used the opposition of dichotomy to construct his “religious life”. Therefore, in the real world, the sacred and the profane are not easily separated. It is impossible to achieve a comprehensive and accurate understanding of Chinese native gods and people’s religious views if we start from the dichotomy of “profane and sacred” attitudes. From this point of view, before entering into the analysis of the related beliefs and practices of “the Direction of Xishen”, it is necessary for us to have a preliminary understanding of Xishen itself.

2.1. Xishen with Diverse Images and Identities in Different Regions

Chinese people have been influenced by Confucianism for a long time and attach importance to real life under the domination of secular reasons. Therefore, their beliefs in gods are often for utilitarian purposes. In other words, their sacrificial activities are often performed in order to seek help from gods in real life, rather than for some sacred purpose. Therefore, most of the auspicious gods in China have a clear role related to worldly happiness. For example, Caishen is in charge of wealth, Wenquxing (文曲星) is in charge of schoolwork, Yuelao (月老) is in charge of marriage and love, etc. These auspicious gods not only have a specific scope of influence but also usually have a relatively clear and fixed image, as well as certain temples dedicated to their worship.

Xishen is different. The earliest records about Xishen appear in the 112th volume of the Taoist classic

Taiping Jing, that says “…Tao control the universe and Xishen comes to help people govern countries, make people live longer, and repulse the enemy from Si-yi.”

1 (

Chen [1445] 2003, p. 419) Some scholars believe that

Taiping Jing appeared in the Han Dynasty, and the oldest version of this classic that can be found so far is the

正统道藏本, from the early Tang Dynasty. Despite being a cultural icon for many years, people have not formed a classic image of Him, and there is no particularly unified or clear statement on his “responsibilities”. For example, the people of Shahe Town, Shanxi Province (山西省砂河镇), believed that the ancient Chinese monarch, King Zhou of Shang (商纣王), was Xishen. (

Zhang 2016) He was primarily in charge of marriage, so they made sacrifices to King Zhou during their wedding ceremonies. (

Xu [1621] 2017) However, in the area of Jiangsu Province, people think that a person named Ge Cheng (葛成) was Xishen. Ge Cheng was a textile worker who rose up and died because he was dissatisfied with the harsh taxes imposed by local officials. He was regarded by the local people as a hero who eliminated violence and brought peace. After his death, he became the protector of his hometown (

Zheng [1679] 1932). In Chengdu, Sichuan Province, the “Xishen Fang Pageant” (游喜神方, meaning to celebrate the direction where Xishen is located to pray for blessings) event, which is held every year during the New Year, is centered on the sacrificial activities of Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮) from the Three Kingdoms period, focusing on his loyalty to his lord. Some people in the northern provinces of China believe that Xishen is a bearded fairy who is primarily responsible for blessing people’s homes and lives. Additionally, in some places, the portraits of people’s ancestors were also called Xishen at a certain period of time, and they believed that worshipping Xishen during festivals could play a role in ensuring the prosperity of the entire family.

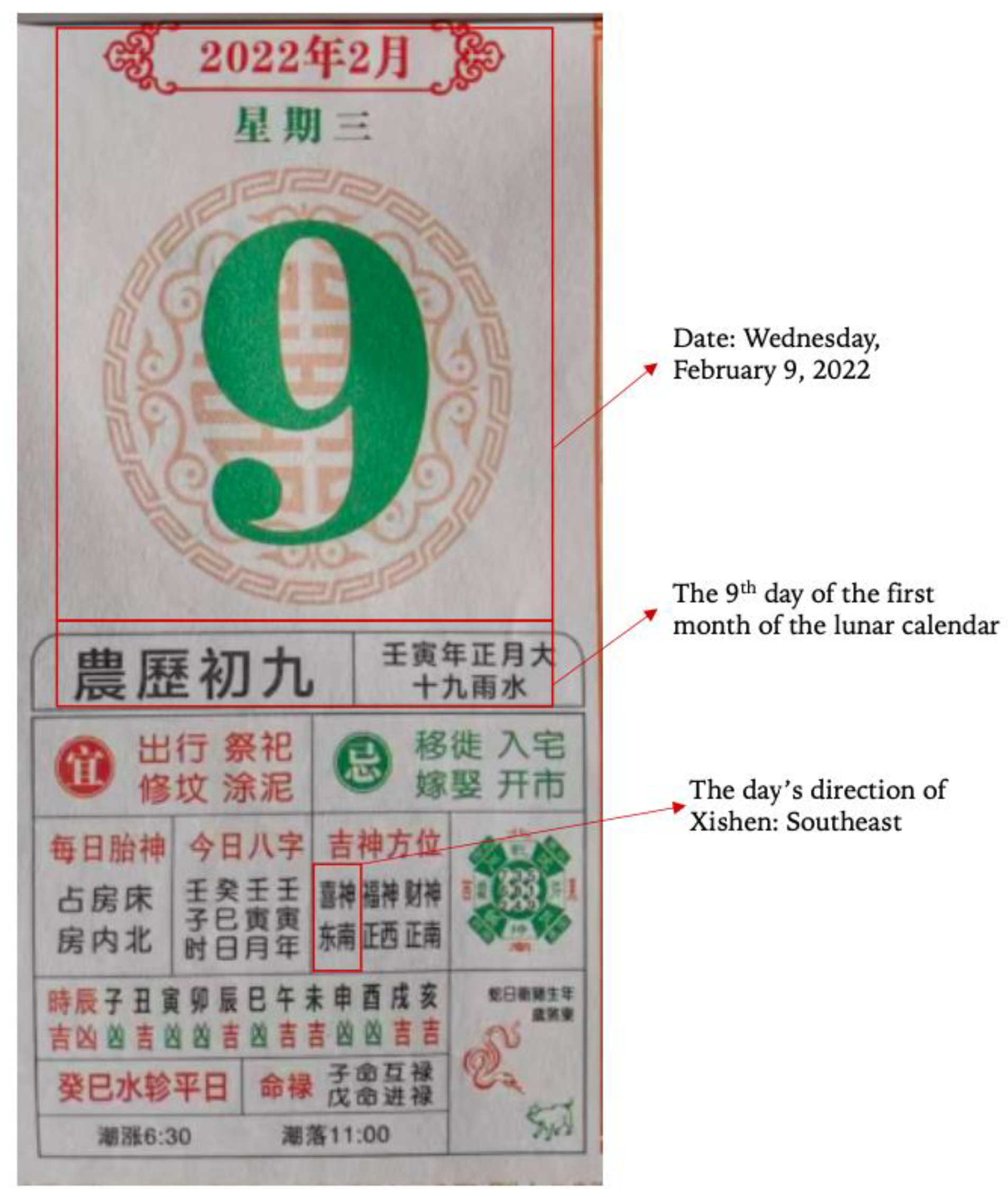

Although the images used to refer to Xishen are not uniform in various places, and the functions and personalities of Xishen are different, they still have two common characteristics: first, they are all incarnations of auspiciousness and happiness, which means that they are “good” gods that people like to see and hear; second, all have spatial and temporal orientations, which is also the point of this article. To be precise, Xishen, which does not have a unified and fixed image, can be identified and marked by the public precisely because of its definite spatial and temporal characteristics. Additionally, because of its uniqueness in space, it has gained lasting influence and popularity among people everywhere. Specifically, the most intuitive manifestation of Xishen’s spatial characteristics is the tagging of the “Direction of Xishen” in the lunar calendar. As is shown in

Figure 1:

2.2. Auspicious Directions: The Identification of “Direction of Xishen” in Traditional Knowledge

We found that many scholars have paid attention to the far-reaching influence of traditional spatial concepts on Chinese folk life and religious culture. Arthur F Wright believes China has “the longest tradition of city cosmology the world has ever known” (

Wright 1977, p. 73). In

The Cosmology of the Chinese City, Wright wrote that “all civilizations have traditions for choosing sites of fortune for a city and symbol systems for relating the city and its various parts to the gods and the forces of nature… Throughout the long record of Chinese city building, we can find ancient and elaborate symbolism for the location and design of cities persisting in the midst of secular change.” (

Wright 1977, p. 33). We can see early religious influence in China’s urban spatial layout. Wright systematically discussed the relationship between ancient Chinese urban forms and cosmic patterns. He believed that, after a long historical accumulation, this symbolic spatial knowledge about belief and power had a great influence on later urban construction. The French scholar Marcel Granet, who studies ancient Chinese religions and songs, believes that the “Ba La” (八腊, meaning eight kinds of gods) rituals in the pre-Qin period (about 221 BC) contained all the basic rules of the social order, and that these laws are expressed in ritual. Those present were divided into two groups, with one group taking the side of the Master of the Ceremony and the other that of the guests. The position of the guests was fixed by an orientation whose influence, it was believed, connected each group with the opposing forces of the universe—heaven and earth, sun and moon, yang and yin—that decide the rotation and opposition of the seasons. (

Granet 1932, p. 172) Marcel Granet observed that the concept of yin and yang dominates traditional Chinese thinking. In religious ceremonies, this idea manifests itself in the fact that the people attending the ceremony are divided into two different groups, and the two groups are placed in two different directions. Such phenomena should arouse our attention, especially when conducting spatial research on Chinese folk religion. As such, we can ask: Why should the position of the participants in religious ceremonies be specified? What do the different orientations mean? Only by knowing the answers to these questions can we understand why Xishen can obtain people’s stable worship and belief by virtue of a specific orientation, and how these characteristics of Him reflect people’s religious belief concepts.

I Ching can be translated as “

Book of Changes”. Wilhelm and Baynes note that “its origin goes back to mythical antiquity… Nearly all that is greatest and most significant in the three thousand years of Chinese cultural history has either taken its inspiration from this book, or has exerted an influence on the interpretation of its text.” (

Wilhelm and Baynes 1967, p. xlvii). In

Zhouyi Qianzaodu (周易·乾凿度), which analyzes and explains the content of

I Ching, it is written: “I(易) begins with Tai Chi (太极), Tai Chi divides into two, so it gives birth to heaven and earth. In the midst of heaven and earth have four seasons: spring, autumn, winter, and summer. Each of the four seasons has the distinction of yin and yang, rigidity and softness, so Bagua (八卦, The Eight Diagrams) is born. After the order of Bagua was established, the Tao (道, law) of heaven and earth is established. And then the images of thunder, wind, water, fire, mountain, and lake are fixed.”

2 (

Zheng 1756 [its publishing time was around the middle of the 2nd century AD]) This passage briefly introduces the concept of yin and yang through the fact that everything in the world changes and grows.

Traditional knowledge of the occurrence and development of all things is developed from this. In this structure, time and space are integrated and inseparable; there is also a close connection between objectively existing things and events that people face in their social life. This can be seen below.

The north is the upper part of the modern plane map, but in the directions of the Inner-World Arrangement, the south and the southern part, which represent summer and sun, and mean the yang’s process of “birth-development-prosperity”, are always marked upper. In its primary meaning, yin is “the cloudy,” “the overcast,” and yang means “banners waving in the sun”. Correspondingly, the change and development process of yin is usually shown at the bottom of the diagram. In the process of occurrence and development, the two poles of yin and yang change from rise to fall and are inseparable from each other. This system’s logic has been described by Joseph Needham thus:

“The key-word in Chinese thought is Order and above all Pattern (and, if I may whisper it for the first time, Organism). The symbolic correlations or correspondences all formed part of one colossal pattern. Things behaved in particular ways not necessarily because of prior actions or impulsions of other things, but because their position in the ever-moving cyclical universe was such that they were endowed with intrinsic natures which made that behavior inevitable for them… They were thus parts in existential dependence upon the whole world-organism.”

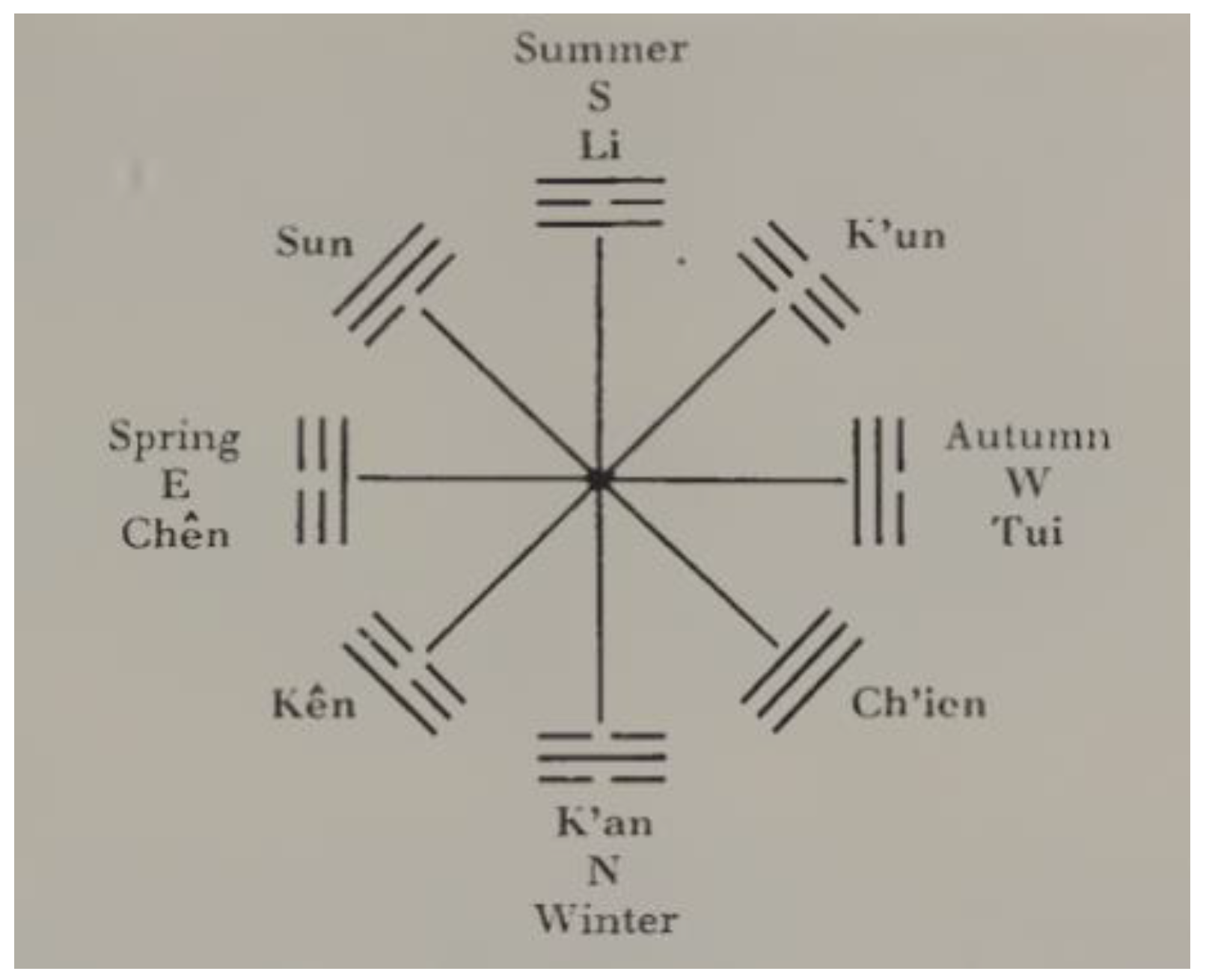

Take one part of

Figure 2 as an example: the “Li” hexagram means that the yang energy has reached the extreme. In this state, all things are active and thriving. This represents the south in the orientation, the summer in the four seasons, the noon in the day, and the “fire” in the eight elements, etc. Therefore, the “southeast–south–southwest” and yang orientations in space are considered to be closely related to auspiciousness and happiness.

Xishen, which brings auspiciousness and happiness to people, is also inextricably linked with the direction of the south. On the first day of the Lunar New Year, the residents of Chengdu march towards the south of the city to welcome Xishen in an event known as the “Xishen Fang Pageant”. This can be seen through historical documents and field investigations, although there are different opinions on the worship of Xishen in different places. However, during the Chinese New Year, offering sacrifices in the direction of Xishen, or welcoming and walking directly in His direction, are widespread belief activities conducted by people. Additionally, the people of Shahe Town will check the almanac on the first few days of the new year, and only when the almanac marks “Xishen in the southeast” will they arrange the ceremony of “Welcoming Xishen”.

In their daily lives, people also pray to Xishen and make wishes. The reason why everyone wants to know the auspicious time of the day and the direction of Xishen relates to their hope that everything will go smoothly in their daily lives. This kind of belief and worship is carried out for utilitarian purposes, rather than out of pure reverence for Him.

The order of the world begins with the calibration of time and space, which includes the distinction and expression of orientation, the precise division of time, and even the formulation of the laws of space and time. In such ritual activities, Xishen, which has no unified image or fixed temple, has an orderly spatial expression in the folk belief system as well as a real and sensible set of belief practices. With the determination of this spatial orientation as an anchor, the time and space of worship activities are unified, and a collective cultural expression system can be constructed for value pursuit and life vision.

4. Folk Beliefs at the Human Scale—Cases Analysis of the Sacrificial Activities of “The Direction of Xishen”

The Bagua knowledge formed from I Ching is a complex, mysterious, and highly technical practical cultural system. For a long time, geomancers have been the authoritative interpreters, disseminators, and practitioners of it. For ordinary people with low literacy levels and busy livelihoods, it is impractical to master these kinds of knowledge. However, this does not mean that ordinary people are clueless about it. On the contrary, they will simplify the knowledge and combine it with their social life and religious etiquette, gradually turning it into a cultural custom to meet the needs of their daily life. For example, grassroots society projects Bagua knowledge into the custom of worshipping Xishen during their marriage ceremony, and the customs of “Welcoming Xishen” (迎喜神), “Xishen Fang Pageant” (游喜神方, meaning to celebrate towards the direction where Xishen is located to ask for blessings), and “Allaying Xishen” (送喜神, meaning to sendoff Xishen after the worship) during the New Year’s Festival. In these practices, complex knowledge becomes useful local knowledge. Therefore, it participates in regional group cultural integration in the construction of meaning in individual life.

In the spatial study of religions, scholars have focused on the importance of the human body. Some scholars think that the physical experience of the body, the interaction between space and the human body, is central to the meaning of religious space (

Kilde 2013). Cognitive philosophers George Lakoff and Mark Johnson stressed the pervasiveness of metaphor in our everyday experience and thought processes, and wrote, “these spatial orientations arise from the fact that we have bodies of the sort we have and that they function as they do in their physical environment” (

Lakoff and Johnson 1980, p. 14). People establish their religious identities through figurative performances, activities, and behaviors in their daily life, and use their body to produce sacred spaces.

“The Direction of Xishen” is not a fixed and certain religious area. It takes people as the coordinates, starting from the time and space where the individual is located, and is carried through religious activities, such as offering sacrifices or praying for blessings, and is presented in the real space of social life. Additionally, from the perspective of different customs in different places, the activities conducted in “the Direction of Xishen” are not always the same. It is inseparable from “local knowledge”.

4.1. Traditional Customs of “Welcoming Xishen” in Shahe Town, Northern Shanxi

Shahe Town belongs to Fanshi County, Xinzhou City, Shanxi Province. It is located in the middle of Fanshi County and the northern part of Shanxi Province, with a permanent population of more than 40,000. There are abundant underground mineral deposits in Shahe Town, including gold, silver, copper, iron, etc. According to the local people, the name Shahe Town is related to the Hutuo River that flows through the town. Shahe Town is rich in folk belief resources, including mainstream Buddhist and Taoist temples, and small temples of folk or local gods, such as the Caishen Temple and the Dragon King Temple. At the same time, Shahe Town has always retained the traditional custom of “welcoming Xishen” during the New Year.

ZXQ was born in Shahe Town in 1932. According to her recollection, every year after the Lunar New Year in Shahe Town, everyone would go to welcome Xishen:

“Every year, the Xiansheng (先生, referring to a local fortune teller, usually a Taoist clergyman) gave us the direction of Xishen and date to welcome Him. When that day comed, the whole family went to welcome Xishen. This was what our ancestors have done for generations. When it was time to welcome Xishen, we put on new clothes and bring five-color paper, offerings, and incense. Following the direction given by the Xiansheng, we went to the open space near the river beach to kowtow to Xishen, placed offerings, burned incense, and prayed to Xishen to bless the family with a smooth year.

At that time, I was very happy to go out to welcome Xishen, because every household went there at the same time, and I was able to meet many friends and relatives. Since I moved to Xinzhou City, I have never welcomed Xishen. I remember that after liberation, people said that ‘Welcoming Xishen’ was a superstitious activity, so they were not allowed to do it.”

ZXQ left Shahe Town very early due to work. Her younger sister ZFY and her niece ZGZ have always lived in Shahe Town. For them, the tradition of “Welcoming Xishen” during the Chinese New Year has never stopped and continues to this day:

“I remember when I was a child, the old said that during the New Year, you cannot do anything before finishing the ‘Welcoming Xishen’. Nothing can be done without welcoming Xishen. Because of that, we welcome Xishen at home every year, it can bring good luck.”

(ZGZ)

“We always welcome Xishen every Chinese New Year, and it was the same when my son took me to the city to celebrate the New Year. On that day, I placed some tributes at home in the direction of Xishen, this is our way to welcome Xishen.”

(ZFY)

In the middle of the last century, and due to the practical needs of economy, politics, and culture, Chinese society used to believe that traditional cultures such as folk beliefs, Feng Shui, and Bagua were backward products of the old society. The customs of “Welcoming Xishen” did disappear in the public space for a time, just as ZXQ recalled. ZXQ left her hometown very early, so she doesn’t know much about what happened afterward. According to the interviews with other people, we can know that, although the activities of “welcoming Xishen” are no longer held collectively and openly, it has not disappeared, and gradually transformed into a private family ritual.

4It shows that although knowledge about directions and folk beliefs is not always respected as mainstream culture, and modern people are gradually changing traditional spatial conditions and lifestyles, folk beliefs are actually a kind of “collective unconsciousness” that still exists. It affects people’s understanding of the space they live in and affects people’s psychological feelings and practical activities in life. From what ZGZ and ZFY said, we can understand that people still have reverence for the auspicious orientation represented by “the Direction of Xishen”, and they will also adopt certain sacrificial behaviors. This also reflects a certain extent that the traditional knowledge of time and space of Xishen has always existed in the collective memory of the Chinese people, and it still influences people’s thoughts and practices today.

With the further emancipation of the mind at the end of the 20th century, folk multiculturalism gradually revived, and the activity of welcoming Xishen has once again returned to the stage of social life. Zhang Yaru from Zhejiang Normal University recorded the activities performed to welcome Xishen in Shahe Township in recent years. According to her research, in Shahe Town, the “Welcoming Xishen” activity is held in the first few days of the new year whenever Xishen is in the southeast. People leave their homes and start their activities according to the tagging of the “Direction of Xishen” in the lunar calendar. The local people believe that, during the Chinese New Year, the Celestial Bureaucracy will convene a meeting of the gods and, after the meeting, Xishen will return to their people from the southeast. Therefore, each family will see their own house as the starting point, holding three sticks of incense, Huangbiao paper (黄裱纸), and firecrackers, and walk towards the southeast. “Welcoming Xishen” is a ritual activity that every household will spontaneously participate in. If there are sick family members or young children who cannot go out, their relatives will take their underwear outside to symbolize that they also participated in this activity (

Zhang 2016).

From the above records, we can see that people usually walk in the southeast direction to welcome Xishen. This is because He and other gods came back from the southeast, which means that the Celestial Bureaucracy—the highest power center of the gods in Chinese folk mythology—is located in the southeast of Shahe Town. Shahe Town is located in the northern part of Shanxi Province. As we mentioned before, since the Zhou Dynasty established political power in Luoyi, the Bagua culture formed during that period naturally placed the center of the world in this place. Luoyi is located to the southeast of Shahe Town, and the activity of welcoming Xishen in Shahe Town also proves the people’s preference for the southerly direction and the origin of the location of Xishen.

Zhang Yaru also mentioned in her research that Shahe Town is located at the junction of the Mongolian race and Han ethnic groups, and many local people travel there for business. Therefore, besides its residents, they also take their main conveyances together to join in the “Welcoming Xishen” activities. People prefer to choose to ride a bicycle or drive a car to welcome Xishen. This is related to the means of livelihood of the locals. People doing business need to travel to and from various towns, and their journey can be dangerous. People hope to bring some good luck to their journey by bringing the conveyances to these activities (

Zhang 2016).

Here, the “happiness” represented by Xishen has more meaning than a safe journey. In a previous interview, one participant believed that offering sacrifices to Xishen would make her less tired from heavy housework. In the following section, we show that the activities of the “Xishen Fang Pageant” in Chengdu became a way of worshipping and pursuing loyalty. It can be said that the “abstractness” of Xishen makes Him a kind of catch-all god who can accommodate everyone’s various wishes. Though the preference for “the Direction of Xishen” stems from some historical factors., in the specific practices, this direction has become a kind of intermediary, and its significance is in expressing the real relationship between man and god in a specific place and the everyday demands of the people.

4.2. Modern Folk Activities of “Xishen Fang Pageant” in Wuhou Temple (武侯祠)

In Chengdu City, the worship of Xishen used to be held in Taoist temples such as Qingyang Temple. Welcoming Xishen was once considered a traditional religious activity in the Spring Festival celebrations of Taoists. The activity of welcoming Xishen in Taoist temples is held on the first day of the first lunar month, and preparations start on the last day of the previous year. This series of activities is primarily led by the leader of the Taoist temple.

On the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, the staff in the Taoist temple start preparing incense cases, tributes, etc., setting up incense cases outside the Taoist temple according to the direction of Xishen, and offer Xishen tablets (on weekdays, Xishen tablets and other Taoist gods’ tablets are placed in fixed positions in the temple). On the first day of the first lunar month, everyone will welcome Xishen together. They will go to light incense in front of the incense table enshrining Xishen, insert it into the incense burner, and perform three worships and nine knocks. The leader will hold up the tablet of Xishen and put it back into the temple, and ask everyone loudly: “Has Xishen come back?”. Everyone replied: “He is back!” After everyone paid New Year’s greetings to each other, the ceremony of “Welcoming Xishen” was considered to be done.

With the changes of the times, the activity of welcoming Xishen has gradually changed from a special Taoist religious activity to a folk activity when citizens celebrate the New Year. Citizens spontaneously travel in the direction of Xishen on the first day of the first lunar month and organize some activities to worship Xishen, hoping to receive good luck in the new year.

This is very similar to the “Welcoming Xishen” activity mentioned above. The difference is that “Welcoming Xishen” focuses on worshiping in the direction of Xishen, while Chengdu residents place more emphasis on the dynamic process of the pageant. The process of moving towards the direction of Xishen is also a good opportunity for small vendors in the city to hold kirmess to sell goods during the Chinese New Year, and for citizens to go shopping and have fun. With this, the “Xishen Fang Pageant” has become a popular activity for Chengdu citizens during the Chinese New Year.

Yu Jiajia from the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics recorded the annual “Xishen Fang Pageant” at Wuhou Temple in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. Wuhou Temple is a place to commemorate Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮), the prime minister of the Shu Han (蜀汉) Dynasty in ancient China. This activity is a sacrificial activity in which Chengdu residents go to Wuhou Temple on the first day of the first lunar month every year. In recent years, it has been promoted by the local government, and it is also reported on by a large number of media professionals every year (

Yu 2021).

Yu’s research show that, since the 1980s, as the organization and holding space of the New Year’s Festival temple fair has shifted from the traditional Taoist temples to Wuhou Temple; the image of Xishen recognized and accepted by the public has also been transformed from the vulgar god into “Zhuge Liang”, a historical figure known for his loyalty. The change of the space carrier represents the change of the core of spiritual thought from Taoism to Confucianism. At the same time, the “Xishen Fang Pageant” endowed the space of Wuhou Temple with more divinity and functions. Luo Kaiyu focused on the “Xishen Fang Pageant” customs of the Chengdu people. He introduced the literature records on Chengdu’s New Year ‘s celebrations since the end of the Qing Dynasty and recorded the folk customs of the “Xishen Fang Pageant” at Wuhou Temple in recent years. According to his investigation, Chengdu people have always had the custom of going to various temples to worship gods to pray for good luck during the New Year. Among them, the sacrificial activities held in Wuhou Temple were the most lively and grand. The “Xishen Fang Pageant” activities, which were held in Wuhou Temple and regarded Zhuge Liang as Xishen, started in 1998. From then on, the “Xishen Fang Pageant” has primarily become a sacrificial activity to Zhuge Liang (

Luo 2005).

Different from the previous cases, the government encouraged the masses to participate in the “Xishen Fang Pageant” held in Wuhou Temple, which is a kind of “contemporary transformation” of the activities of worshiping Xishen. Different from the traditional relationship between man and god, official power is now added to form a new shaping of social relationships. Endowing Xishen with the spirit of “loyalty” will help to enhance people’s sense of identity with mainstream values. This does not only enhance the value of local cultural symbols but also promotes the inheritance and development of traditional folk customs. This also reminds us that, in spatial study, in addition to the specific physical space, we must also pay attention to the development of symbolic cultural space. This is especially important in contemporary times, when various cultural forces interact in society. Although some folk customs still follow traditional steps and models, the cultural connotations and meanings they expressed have changed with the times.

4.3. “Allaying Xishen” after the Wedding Ceremony

In 2019, we held a conversation with a Taoist priest called Tian from Xuanmiao Taoist Temple. He believes that although there are great differences in regional cultures, people generally don’t allay Xishen because they think it may send their happiness away.

5However, according to many records, the ritual of “Allaying Xishen” is always held after the wedding ceremony in some areas. Usually, at the wedding, Xishen is welcomed to bless the couple a happy married life. But in the early morning of the day after the wedding, married people will hold a ceremony to allay Xishen. After that, the married couple commence normal social activities. In some places, it is said that people who have not allay Xishen after their wedding ceremony cannot go to other people’s weddings.

In some ethnic minority areas in southern China, the ceremony of “Allaying Xishen” is as follows:

Early in the morning of the second day of the wedding, the matchmaker will urge the bride to allay Xishen. The bridegroom and his family will place a table in the main hall with two stools on both sides. On the table, there is a pot of cut fat pork and a jug of wine. The pork was half cooked. Four matchmakers sit on benches on either side. The matchmakers from the bride’s side will sing a folk ditty to allay Xishen. The main idea of ditty is: the master is optimistic about the good day, so that the two young people can get married…wish them a happy life and an early birth to a precious son. The singing time is very long and sometimes can take more than an hour.

It is generally believed that a wedding banquet with a large number of guests and a lively ceremony will inevitably attract evil things such as monsters and ghosts from the vicinity to attend. Therefore, the “Allaying Xishen” ceremony needs to be held to drive away these demons and ghosts while sending Xishen back to heaven.

5. Epilogue

The sociologist of religion Peter L. Berger believes that religion “has played a strategic part in the human enterprise of world-building.” (

Berger 1990, p. 37). It means the projection of the human order into the totality of existence, which envisions the entire universe as meaningful to human beings. The belief in Xishen may not be ascribed to a systematic religion, but the Bagua knowledge behind it contains a unique interpretation system for the concept of “harmony between heaven and man” and other cosmic concepts. This is an attempt to give meaning to life in the world and to interpret the value of life through the order of the universe. The research of spatial elements in the belief in Xishen allows us to perceive the cultural ecology of folk beliefs, social customs, and secular rationality. As we stated in the first part of this article, to a certain extent, there is a symbiotic relationship between Chinese religious belief and secular life, and the dichotomy between the sacred and the secular may not necessarily apply to Chinese society. Although Bagua knowledge is mystical knowledge, it also provides a set of cultural symbol schema for understanding real life. Additionally, as a cultural interpretation system, it provides a place for individual life to settle.

In fact, the spatial study of Chinese folk religion should not leave the discourse environment of the integration of time and space as our ancestors thought that time, space, body, and mind are related and inseparable. “The Direction of Xishen” has become a religious spatial practice by opening up the connection between religious space and secular life, behind which lies the shaping of social relations. “Welcoming”, “allaying”, and the pageant, activities closely related to the human body, are all specific ways of presenting the spatial practice of “the Direction of Xishen”. Folk religion has an inseparable connection with the masses in the specific practice process and gains lasting vitality from this process.

Space exists naturally, and human construction behaviors make space meaningful. On the one hand, the judgment and choice of good or ill orientation do reflect the function and meaning that human subjective concepts give to natural space; on the other hand, it is the objective existence of natural space that influences people’s productive life and shows a cultural expression in society. This makes space and directions not only a tangible concept but also a spiritual space full of symbolic meanings influenced by social culture and folk beliefs. Through these cultural traditions, certain regular patterns and norms are formed. They guide and constrain people’s daily behavior and ritual behavior.

This article takes the worship of Xishen as the analysis object, and describes and explains the Chinese people’s concept of space and the relationship between man and gods in folk beliefs. This article tries to show that the determination and selection of the “Direction of Xishen” contain rich cultural significance and shows the spatial concept that takes the south as the location representing auspiciousness and good luck. It shows the integration of “time-space-man” into traditional Chinese culture.

The worship of Xishen has the inheritance of time and universality in space in social life. At the same time, it has also developed unique ritual practices and belief systems in different regions, shaping different collective memories and behavioral norms. Although the current cultural practice of “the Direction of Xishen” is different from the previous folk belief ceremonies in terms of form and connotation, it has been passed down to this day and still plays an important role in festival celebrations and wedding ceremonies. These phenomena also convey the theme that “traditional folk beliefs and customs represented by the worship of Xishen still play an important role in our daily life”.