Abstract

The diversity of multicultural, multi-religious, and multi-ethnic groups and communities within Britain has created cohesion and integration challenges for different community groups and authorities to adapt to the current diverse society. More recently, there has been an increased focus on Muslim segregation in Britain in official reports and reviews. Those documents mentioned the Muslims’ segregation (directly or indirectly) for various reasons, and some recommendations have aimed to improve “community cohesion” in general and Muslims’ “integration” in particular. However, community participation in the design or planning of regeneration and development projects has yet to be focused on, although these documents recommended promoting community cohesion and integration through these projects. Community participation in architecture—in its broader sense—is a crucial aspect that contributes towards fulfilling the tasks of serving communities with different religious and ethnic backgrounds. Muslims’ religious and cultural practices have been problematised in urban spaces and perceived as leading to social and spatial segregation. This paper intends to explore how secular urban spaces are used and perceived by Muslims through their religious and cultural practices. Therefore, the article aspires to inform the community participation in urban projects and demonstrates the role that Muslims’ inclusion in designing urban projects has in promoting cohesion and integration. The Ellesmere Green project in Burngreave, Sheffield, UK, is an empirical example of exploring this locally through semi-structured interviews with community members, leaders, and local authorities’ officials. The findings demonstrate that sacred and secular spaces are interconnected in Muslims’ everyday lives, and the boundaries between them are blurry. The data also show that having the ability to manifest their religious and cultural practices in secular urban spaces does not suggest the desire for segregation, nor does it reduce Muslims’ willingness to have social and spatial interactions with non-Muslims.

1. Introduction

British society is becoming increasingly diverse ethnically, culturally, and religiously. This diversity has occurred due to centuries of immigration to Britain for many reasons, including colonialism, job market needs, and refuge from armed conflicts worldwide. As part of the challenges from this diversity, Muslims have been repeatedly problematised, highlighted, and targeted as a community that requires further attention. This is due to the complexity of their composition, ethnic and religious practices on the one hand, and several notable incidents linked to Muslims in Britain and around the world, including riots and terrorism affairs on the other hand.

British authorities considered necessary steps towards encouraging cohesion and integration amongst diverse community groups by introducing several policies and action plans based on numerous studies, such as the after riots reports in Cantle (2001), the Commission of Integration and Cohesion report (2007), The Casey review (2016), and the Green Paper: integrated communities (2018). Starting from 2007, the government has emphasised the notion of integration rather than community cohesion in its discourse across the recently released integration documents, the Casey review, and the Integrated Communities: Green paper. Thus, this paper is written in the context of the current national and local agendas that aim to promote cohesion and integration amongst communities through regeneration and development projects. The Muslim community record in this aspect is not well explored for several reasons. One is the mischaracterisation of the Muslims’ religious and cultural practices in the secular urban realm. Muslim religious practices are linked to the Mosque, a dress code, and sometimes even the physical appearance (the racialisation of religion). Muslims are often studied based on their faith, not their day-to-day life practices, such as socialising, shopping, and playing. Many Muslims perform these “secular” practices in “secular” spaces from a religious and cultural stance. Therefore, it is essential to understand that Muslims are not just a faith group but also community members with other activities performed outside their “sacred” spaces linked to their religion. This paper aims to show the interconnectivity of Muslims’ religious and cultural practices with secular spaces and how the British public may perceive this. This is elaborated through the case study of the Ellesmere Green project in Burngreave, Sheffield, UK, as part of the first author’s PhD project. Interviews were conducted with community members of different ages, genders, and occupations. The empirical piece of this paper utilises qualitative research methodology through semi-structured interviews with community members, leaders, and local authority officials. Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted with the local Muslims and local authority officials to investigate Muslims’ participation in architecture and urban projects in Britain through the lens of the Ellesmere Green project in Burngreave as a case study. This will provide an understanding of the Muslim community’s practices when engaging them in an urban project to promote cohesion and integration.

The main body of this paper is structured into two key sections: the literature review, the case study, and the conclusion. The literature review section included the main subjects: 1. Muslim segregation and its relation to sacred and secular spaces (including three sub-chapters: Muslims’ social segregation, spatial segregation, and governmental efforts); 2. the role of community participation in promoting community cohesion and integration (including two sub-chapters: community participation, cohesion, and integration in architecture and the social role of participation). However, the case study of the Ellesmere Green project in Burngreave, Sheffield, UK, is an example of Muslims’ engagement with an urban, secular space, where participants were selected from different ages, genders, and nationalities. This empirical part of this paper utilises the qualitative data collected using semi-structured interviews with community members, leaders, and local authority officials, as part of an ongoing PhD research project carried out by the first author under the supervision of the co-author and a co-supervisor. Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted for the primary research with the local Muslims and local authority officials to investigate Muslims’ participation in architecture and urban projects in Britain through the lens of the Ellesmere Green project in Burngreave as a case study. Through this case study, this paper focuses on the spatial implications of the Muslims’ cultural and religious practices in accordance with the local and national community cohesion and integration policies.

2. Muslims’ Segregation and Its Relation to Sacred and Secular Spaces

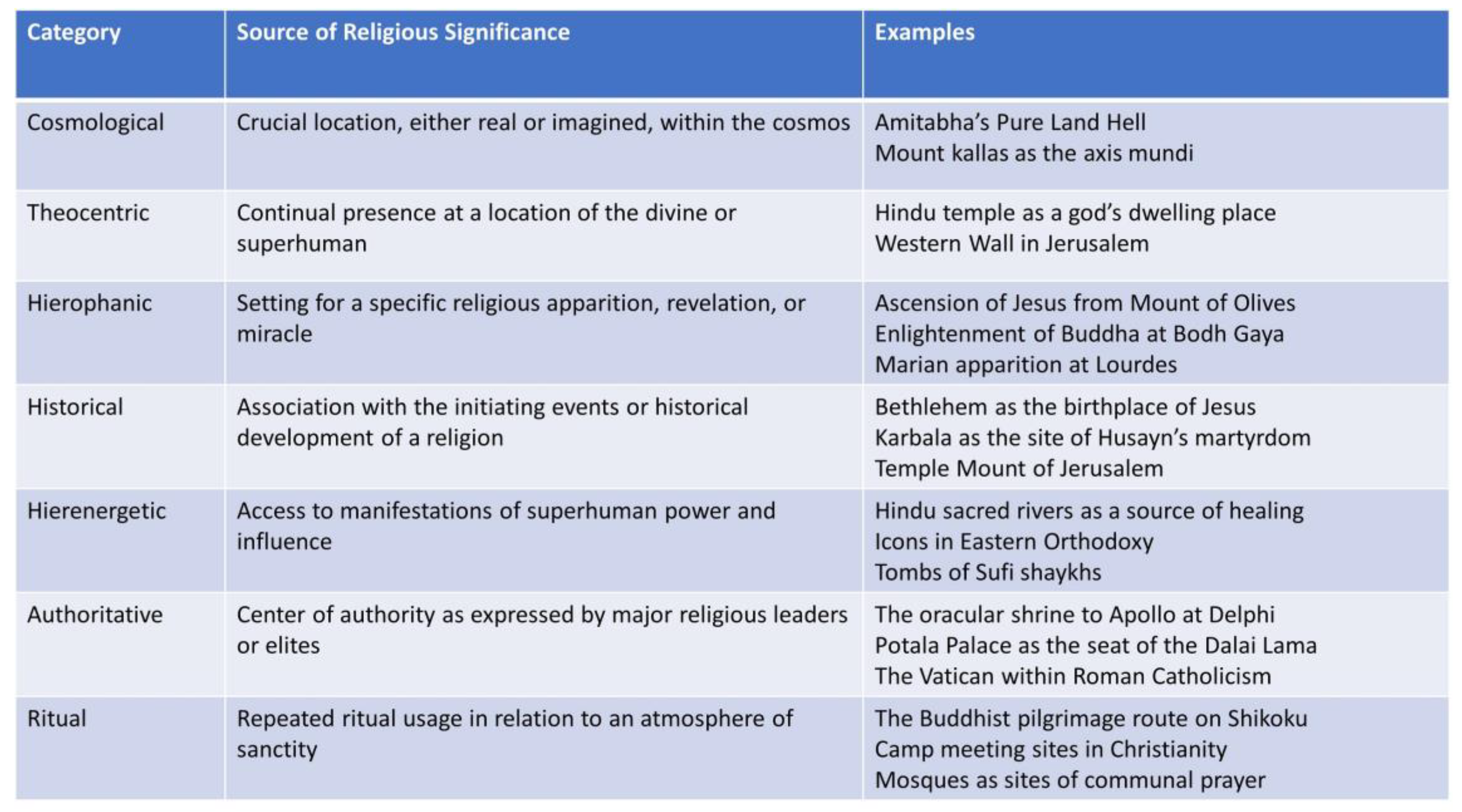

Religion followers determine the sacrality or secularity of the space per the space concerning the manifestation of their religious beliefs and practices (Stump 2008). There are many categorisations of sacred space depending on its scale of it and the nature and frequency of religious practices in any given space (please see the table below by Stump 2008) (See Figure 1). However, in the case of Muslims, spaces and places where worship activities (e.g., prayer and pilgrimage) are performed, such as mosques and the holy cities of Mecca and Madinah (In Saudi Arabia), are considered sacred. In more local and ritual terms, mosques are the most locally manifested space for Muslims’ explicit religious practices in the western world. Nonetheless, secular spaces are also used by Muslims in their everyday lives, which may influence the urban realm significantly in a setting where Muslims are not the majority Muslim setting, such as the case of Muslims in Britain with Halal shops and restaurants and shops selling Islamic clothing and items. In the following parts, we demonstrate the spatial implications of Muslims’ religious and cultural practices in Britain and what constructs the boundaries between sacred and secular spaces from the Muslims’ perspective. However, it is worth exploring the social context of Muslims and the broader community and understanding its impact on the urban space.

Figure 1.

Categories of sacred spaces (Stump 2008).

2.1. Muslims’ Social Segregation

The word “Muslim” became problematic in Western countries for many reasons, from different terror attacks taking place in the name of Islam to the claimed integration challenges. Numerous events that occurred in Britain and elsewhere drove the attention of the British public to the Muslim community and furthered the discussion of their integration and compatibility with British society. In particular, the event later known as “Rushdie’s Affair” (1989) and the Northern cities and towns riots (2001) are considered the main turning points that have led to questions about the Muslim community in Britain (European Council of Religious Leaders (ECRL) 2007). Moreover, domestic terrorist attacks such as the 7/7 London bombing, the murder of Lee Rigby, and the Manchester Arena terror attack have played a significant role in shaping the wider society’s perception of Muslims in Britain. In addition, Muslims in Britain are primarily problematised for being a menace to British values and as having a different, incompatible culture and religion (Mehan et al. 2022a; Fuad 2012).

The notion of “visibility” in Islam translates to the sensorial and material power of the Islamic self, fashioned into its self-presentation in urban space (Kozlowski et al. 2020). For example, it is thought that Muslim-run schools are causing cultural backwardness (Modood 2003), and religious practices and forms of dress code, such as the Hijab (headscarf) and Niqab (Burka), are regarded as elements that are in contradiction with the British values (Casey 2016). Thus, the manifestation of Muslims’ religious and cultural practices in secular settings is seen by the British public as a threat to their security and cultural values and unsettling to the secularity of public spaces.

Furthermore, the challenge of loyalty around categorising identity through Islamic values or by Britishness is another matter that has been raised. Although most Muslims claim that there is no inconsistency between being a Muslim and a British citizen simultaneously (Fuad 2012), dominant perceptions position these two identities as incompatible (Sartawi and Sammut 2012).

Islamic culture promotes the sense of a worldwide community—Umma—among ordinary Muslims. On the other hand, the everyday experiences that Muslims face as a minority in Britain have led Muslims to consider themselves an excluded group. Thus, they perceive that the sense of belonging and recognition are pillars of constructing solid social interactions with the broader community and, therefore, encourage community cohesion and integration.

Samad (2010) explored this in Bradford (A northern city in Britain), where he investigated Muslims’ perceptions regarding their neighbourhood and the wider local community. The study was conducted with UK-born and non-Muslim participants and newly arrived Muslims and non-Muslims (Samad 2010). Although Muslims showed a good sense of pride towards the locality—mainly UK-born Muslims—and casual social interactions with other communities (particularly in public places), there are still numerous issues that are obstructing them from achieving a sense of belonging, such as discrimination, deprivation, and exclusion (Samad 2010). Another study led by the Communities and Local Government (CLG) (2009) on the Pakistani Muslim community in England shows that Muslims are critical of the current debate about integration and cohesion. They feel that they are ignored most of the time unless a public crisis arises, and they think promoting integration should be reciprocal with the broader community (Communities and Local Government (CLG) 2009)). This demonstrates the degree of compatibility and connection of the Muslim faith with the secular environment, which rejects the idea of being perceived as a threat to British secular values. Therefore, despite their exclusion and cultural and religious diversity, Muslims’ everyday lives are “informed by faith-based practices and ethics of living together” (Mansouri et al. 2016). Therefore, Muslims in Britain consider that their social relations with the broader community are primarily derived from their day-to-day experiences and their everyday interactions with others in the secular setting. In short, Muslims’ and the wider community’s perceptions of each other are grounded in various factors. The gap in their social interrelationship is expanding and leading Muslims to be socially segregated, interactively limited, and less involved in different community activities. However, Muslims tend to show a greater aspiration for diversity and social interactions with other ethnoreligious groups. This also emanates from their religious belief that suggests Muslims should coexist with other groups. Projecting the Muslims’ social exclusion on the built environment explains the appearance of spatially segregated Muslim communities and reflects the concentration of Muslims’ particular religious, social, and cultural practices.

2.2. Muslims’ Spatial Segregation

The lack of social interactions between Muslims and the wider community shaped the segregated urban public sphere and led to the emergence of concentrations based on ethnicities and religious orientations.

This primarily concerns Muslims’ concentrations in several cities and towns around the country, usually referred to as “parallel lives” or “segregated communities”, and this has been addressed regularly, specifically after the 2001 riots in some Northern cities and towns.

Muslims cluster together for different reasons leading to various consequences. These fragments resulted from choice-based segregation (self-segregation), where Muslims prefer to be surrounded by people from the same ethnic or faith group to feel safer and away from racism. Consequently, such neighbourhoods manifest a unique urban realm that reflects the Muslims’ presence and sometimes dominance in the area, including Mosques, Halal shops and restaurants, cultural centres, usage of different languages in shop frontages, etc. This also helps the Muslim community to exhibit their identity and protect their sacred spaces when escaping racial discrimination and harassment.

However, according to Amin (2002), Muslims are forced to be self-segregated through the fear of racial harassment and the White communities moving from inner cities to new estates in the suburbs. This led to the production of other self-segregated White-dominant residential areas, which displaced to avoid contact with other ethnic groups (Amin 2002). As a result, the abandoned homes in towns and cities were occupied afterward by ethnic minorities seeking settlement and security in same-ethnic community groups (Amin 2002). Thus, self-segregation is not limited to Muslims; it is also a matter of White communities. In some cases, these Muslim-concentrated neighbourhoods resulted from intentional segregation previously led by discriminative approaches in employment and housing (Community Cohesion Review Team (CCRC) 2001).

On the other hand, Varady (2008) claims that Muslims’ clustering is voluntary and associated with their religious and cultural practices, such as areas close to Mosques, Halal shops, and cultural facilities. He sees that their refusal of secularity and Britishness encourages them to be surrounded by an Islamic environment, leading them out of the social and economic mainstream (Varady 2008). This interpretation eliminates the causes of Muslims’ exposure to racism, discrimination, or deprivation—particularly in housing policies—addressed in previous reports and studies. It also neglects the willingness of the Muslim community to protect their sacred spaces and their ability to manifest their religious and cultural practices in secular spaces without being perceived as a threat to secularity. For Hoelzchen (2021), religious infrastructures such as mosques promise the continuity of one’s past with one’s present and future. They are generative of specific moral states and imaginaries at individual and collective levels (Hoelzchen 2021).

From a political and economic perspective, Skirmuntt (2013) concluded that residential segregation might be linked to limited political participation and driven by the economic status of the households (Skirmuntt 2013). However, Varady (2008) perceives that Muslims in their spatial concentrations are encouraged by their religious and cultural traditions to produce fundamentalism and violence towards Muslim members—women in particular—and the wider community. He considers Muslims living in segregated areas as fundamentalists and sees them as having an incompatible culture at odds with and threatening to the majority society (Varady 2008). This is an inaccurate judgment as the examples and acts utilised to validate this view are personally motivated and have no relations with being surrounded by people from the same faith group (a Muslim man murdering his daughter for dating a Christian man and another one killing his daughter for marrying a man without his approval). Nevertheless, forced marriage and crimes of honour are present in some traditions among the Muslim community in Britain (Conway 1999). This does not exclude the fact that the comfort of Muslims being concentrated geographically increases perceptions of their foreignness attributes in relation to the broader community through the practice of their original cultural traditions and religious practices.

To summarise, Muslims’ spatial clusters occur through self or forced segregation reasons or a combination of both; however, in any case, Muslims’ relation to different secular and sacred spaces and places is—to various degrees—linked to their religious and cultural activities. Alternatively, as Stump (2008) stated, “the relationships between religious systems and secular space, expressions of territoriality serve as how adherents integrate their religious beliefs and practices into the spatial structures of their daily lives”. It also demonstrates the blurred boundaries between the sacred and secular spaces in Muslims’ everyday lives. Muslim spatial segregation may be of little benefit to some of its members. It is significantly and undoubtedly harmful to the overall British society, however. This mobilised authorities to investigate this issue through reports and reviews, which were the basis of later policies and action plans. In the next part, we discuss the government’s efforts to encourage a better social and spatial interrelationship between Muslims and the broader community.

2.3. The Governmental Efforts

British authorities are concerned about promoting a better atmosphere for diverse communities and enhancing their social relations to form a healthier society. Therefore, successive British governments developed numerous policies based on reviews and reports to boost the social and spatial interrelationship between Muslim communities and the wider community (Community Cohesion Review Team (CCRC) 2001). These documents addressed the challenges facing various communities and suggested recommendations to be applied at the local level with a national vision. However, from an architectural perspective, there is general recognition of the need for more community involvement in regeneration projects through community cohesion and integration reports. The critical issues detected throughout community cohesion reports since 2001 can be summarised mainly in the communities’ urban and ethnic division; the lack of engagement and participation of community members in decision-making; and the absence of common identity, shared values, and social interactions (Denham 2002). From an architectural lens, recommendations and action plans for different projects were proposed more broadly and superficially. These included creating public spaces and the necessity of different communities’ involvement in regeneration and development projects. For example, the Our Shared Future document released by the Commission of Integration and Cohesion (CIC) in 2007 recommended that “On regeneration, the key to creating these open and shared spaces is to ensure that they are designed in consultation with all sections of the local community, engendering a sense of ownership and belonging. But all too often there is a split between ‘bricks and mortar’ thinking, and strategies for the impact this will have on local people”. It also referred to the findings of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation Report (2007) as part of the Youth Foundation for the Commission by stating that the report “found that regeneration strategies that fail to consider local attachments to existing places may undermine existing networks within local communities. Those public spaces that look good but fail to provide adequate amenities or connections to existing social and economic networks will result in sterile places people do not use” (Commission of Integration and Cohesion (CIC) 2007). The integrated Communities: Green paper published in 2018 also highlighted the importance of community participation. “Local communities should be actively involved in the plan-making process, so that there is a clear understanding and shared vision of the residential environment and facilities they wish to see. Local planning authorities should also seek to involve all community sections in the planning decisions that will affect them and should support and facilitate neighbourhood planning” (The integrated Communities: Green paper, 2018). These objectives might apply to overly homogeneous communities with at least one common aspect other than the locality, such as ethnicity or religion. However, it is challenging when it involves a heterogeneous community at multiple levels. In addition, these are vague recommendations with an unclear mechanism to be considered by national or local authorities.

3. The Role of Community Participation in Promoting Community Cohesion and Integration

As a field that encompasses economic, cultural, and social aspects, architecture plays an important role in bringing diverse communities together and fostering a shared atmosphere. Bento (2012) asserts that good-quality architecture improves the relationship between citizens and their environment and contributes effectively to social cohesion (EFAP 2012). This role consists of the built environment as a platform for social interactions through shared spaces. In addition, the role of the community participation process when proposing and designing these spaces. However, the built environment is an outcome that should be produced through the participation of its users, so it is relatively linked to effective procedures throughout the process (Dempsey 2008). From the Muslims’ perspective, religious and cultural practices significantly impact the space, whether it is sacred to them or a common secular urban space. The two types of space are interconnected from Muslims’ perspective and not mutually exclusive.

3.1. Community Participation, Cohesion, and Integration in Architecture

The concept of community participation was initiated about five decades ago following community movements in Asia and Africa during the colonisation period (Aigbavboa and Thwala 2011). It appeared in the US and Europe after citizen movements against poverty and exclusion. Many community organisers and activists began to challenge planners to enable grassroots participation, such as Davidoff (1965) and Alinsky (1972) (Yabes 2000). Hence, community participation is considered a method to tackle exclusion and empower disadvantaged community groups (Mehan et al. 2022b; Razavivand Fard and Mehan 2018). This applies to the current situation of Muslim communities in Britain, regardless of the causes and reasons behind their disadvantageous status and exclusion.

In general, the notion of community participation signifies community members’ influence and control over the developments and decisions that impact their daily lives (Repellino et al. 2016). In this setting, community participation in architecture includes involving communities in planning and designing development and regeneration projects to solve their problems and/or improve their built environment (Aigbavboa and Thwala 2011). They cannot be forced to participate, but they should be allowed to do so (Harvey et al. 2002). It is the engagement of people other than designers and architects in development projects; this includes clients, users, and the wider public (Jenkins et al. 2009), which can be performed locally or at a grassroots level (Tirivangasi et al. 2016).

Community participation became a practice in Britain through John Turner’s publications (e.g., Housing by People (1977) and Building Community (1988)) and through Walter Segal’s self-build method during what was known at the time as the “Self-Help” era (Downs 2017). Turner began to develop his ideas about community participation by prioritising households’ participation in designing houses over the state’s housing provision. This was to create places that meet households’ socioeconomic and cultural needs rather than responding to housing demands (Jenkins et al. 2009). Using prefabricated timber frames, Segal aided Turner’s ideas in practice and promoted people’s participation from design to self-build housing (Jenkins et al. 2009). More recently, as part of the community cohesion and integration discourses in Britain, governments have regularly raised the need for people’s involvement in development and regeneration projects that may affect communities’ well-being. Although there were no specific recommendations in this context targeting particular communities, Muslims were at the centre of all reports leading to these conclusions (UK Government 2018). Thus, if any community needs involvement the most, Muslims should be the community that requires excessive attention. It could, however, be just a task for the developer to complete. It may be utilised as a tool to obtain legitimacy and share responsibility for any failure in development (Raco 2000).

3.2. The Social Role of Participation

Involving community members in planning and decision-making processes should make them collaborate to find solutions to socio-spatial problems, unite them to improve the overall quality of their environments, and, most importantly, promote a sense of belonging and community by bringing people together (Dede 2012). This reflects the steps needed in the present case of Muslim communities in Britain, where social and spatial segregation exists in many cities and towns across the country. From a social perspective, participation generates social interactions among diverse community groups during the process of participation itself. It allows people to create space for these social connections. Burns et al. (2004) argued that community participation has a fundamental social role in improving social cohesion and community sustainability by valuing the importance of diverse groups working together to develop knowledge and skills and tackle exclusion (Burns et al. 2004). It also empowers community members in general and disadvantaged groups in particular by sharing their sense of belonging and reinforcing their social interrelationships throughout the process resulting in an effective development program (Aigbavboa and Thwala (2011)). Nonetheless, the implication process of community participation represents a mechanism that encourages connections among community members regardless of physical outcomes. However, this can only be achieved by including different social, religious, and cultural groups (Mehan 2020; Wilson et al. 2015).

From the perspective of Muslims in Britain, considering the interconnectedness of sacred and secular spaces, their participation needs to be informed by their faith-based perception. Mansouri et al. (2016) claim that the daily activities of Muslims, from shopping for halal food products to celebrating religious festivities in secular urban spaces, promote a combination of the secular and the sacred through incorporating performative practices into the creation of places (Mansouri et al. 2016). Therefore, the design of any place and its facilities should consider the minority’s cultural or religious requirements, such as space for prayer and washing facilities or the number of rooms in the case of Muslims (Commission for Architecture and Built Environment (CABE) 2008).

As a practical example of what has been discussed theoretically above, the next section will focus on the case of the Ellesmere Green Project in Burngreave, an urban local improvement project completed in one of the most deprived and Muslim-concentrated areas of Sheffield in 2013.

4. The Ellesmere Green Project in Burngreave, Sheffield

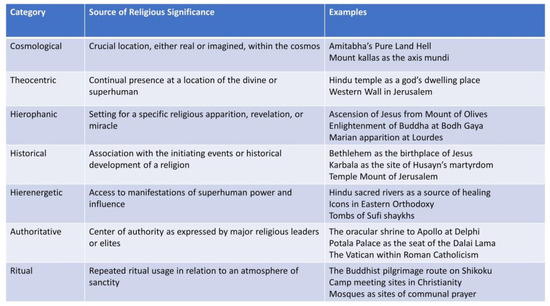

Burngreave is one of the most deprived areas in Sheffield, where Muslims are at their highest presence in the city, with over 60% of the population in the area being Muslims, originating from various countries (2021 Census). Between 2004 and 2007, there was a proposal to improve Ellesmere Green (green space and its surroundings at the heart of the area) in parallel with the Burngreave New Deal for Communities that aimed to enhance the appearance of the area and aspired to promote a stronger community (BNDfC website). The project consisted of improving the central green space and renovating the shops’ frontages, and after an extended consultation process, the project was finally completed in 2013 (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Ellesmere Green © Authors (2021).

As part of the PhD research of the first author at the University of Sheffield under the supervision of the co-author and guidance of the co-supervisor, twenty interviews were carried out with local Muslims and local authority officials to investigate Muslims’ participation in architecture and urban projects in Britain through the lens of the Ellesmere Green project in Burngreave as a case study. Ten interviews were conducted with community members and business owners, four with official and unofficial community leaders, and six with local authorities’ officials, including Sheffield city council, South Yorkshire police, and the National Health Service (NHS). In addition, Muslim participants were selected from various nationalities, including Yemen, Libya, Jamaica, Algeria, Tunisia, and Somalia. However, only those relevant participants and responses are taken on board in this paper. Moreover, participants from the local community members were mainly males. However, some women in the area suggested that councillor Safiya was the right person to represent the women’s perspective.

4.1. Muslims in Burngreave

Muslims who were interviewed said they settled in Burngreave in order to be around multiculturalism for a variety of reasons. This includes seeking safety and escaping racism, being close to people from the same ethnic and (or) religious background, and being surrounded by an Islamic environment that meets their religious and social needs, such as mosques, Halal shops, and restaurants. When residents (selected from different ages, genders, and occupations) were asked about why they or their parents moved to Burngreave, below were some of their responses:

“The community, Muslims, and the community in general, as well as mosques” “…more Islamic, and not just that, the mixture. If you go to other areas, you will find racism, and they may damage your car. For example, I lived in Gleadless (a predominantly White working-class area). The latest tram, I think, was around 8:00; after 8:00, we would be in danger there. If households there see that you are a foreigner from Africa or Pakistani, they will vandalise your house. Burngreave was a refuge for Muslims”(a 40-year-old community member and business owner)

“…for work, second, to be comfortable, in a way where I don’t have to worry about making friends, neighbours, shopping, butchers, all this kind of stuff. Everything I need is within touching distance”(a 32-year-old community member and business owner)

Thus, safety and the Islamic environment—mosques, Halal shops and restaurants—were critical drivers for Muslims moving to Burngreave, which later became a Muslim-concentrated area with multi-ethnic backgrounds. This may have unintentionally encouraged the local Muslim community to be isolated from the wider community and eventually segregated spatially.

Nonetheless, respondents were willing to interact with other community groups in the area and outside Burngreave to be part of the wider community, which contradicts the notion of the choice-based self-segregation and demonstrates that their ability to perform their daily religious, cultural, and social activities in the public urban spaces, is the primary driver of their choice to live in areas such as Burngreave, and not the desire of being isolated. This was clear in some of the community members’ answers when asked about activities in the area and not asked about their relationship with other faith or ethnic groups.

“...however, I do feel something should be done where we can invite all the communities together; for example, in Burngreave, I don’t see any of the White ethnic groups; I would like to see more of that, where they can integrate with our culture as well, and we get to understand their culture. For example, when the vaccine was given out, I saw a long queue, mostly White ethnic groups, which I never normally see in Burngreave. I like to see more of it to break that racism barrier and all the groups. It would be nice to see just humans being humans”(a 19-year-old community member)

“After I opened the business, our community and other communities used to come to this restaurant, and we tried to clarify to them why we came to this country and that we are part of you.”

“…Non-Muslims in general. Polish, English, Slovakians”(a 40-year-old community member and business owner)

Likewise, when council officers who worked on the project were interviewed (two of them were White), they mentioned the excellent relationship they developed in the area, especially with businesses, since they were the most consulted people, according to these officials. At the time, the developing council officer in charge of the Ellesmere Green project said, “I had a really good relationship with the local traders… I found that the people were very friendly, to be quite honest, everybody that I met was very friendly…”. A former local official also stated, “what we got was that people were fantastically open, generous, and welcoming. Really thrilled that we’ve come to speak to them. Deeply polite, but without the language of official understanding or architectural understanding -it’s been in my head for 40 years- to communicate. People would welcome us, shop owners, even if they were busy, give us a cup of coffee, or often give us gifts, CDs or the Quran. It was a deeply moving experience for me.”

These testimonies provide a clear message from the Muslim community regarding their readiness and willingness to engage with the broader community despite the occasional language barrier through practices that fundamentally emanate from their religious beliefs, such as generosity. This reinforces the idea that Muslims’ daily routines in what are perceived as secular spaces are approached with a religious attitude. Despite this, Muslim community members distrust the local authorities as a whole, suggesting a concern about exclusion. On the other hand, local authorities’ officials recognise this and work to strengthen their relationship with local Muslims. An obvious example of these efforts is the “Race equality commission in Sheffield” (2022), commissioned by the Sheffield city council and chaired by Professor Kevin Hylton, which was apparent to nearly every local official.

“The council definitely wants to be transparent and open and include anybody that wants to come along”(The principal development officer at the Council)

“I think, in terms of Sheffield City Council, I think that within the officers, there’s a genuine desire to bring benefit to everybody. I think there’s a lack of understanding how to do that”(former local official)

Thus, the acknowledgement is present. However, further efforts are sought to build trust and an understanding of different communities’ practices and challenges, especially among these authoritarian bodies. The following segment illustrates an example of the Muslim community’s participation in secular urban projects and how the local authorities handled the process.

4.2. The Muslim Community’s Participation in the Ellesmere Green Project

The Ellesmere Green project passed through different phases before it was accomplished, from an idea in 2004 to an accomplished project in 2013. It is published on the Sheffield city council website that a consultation process with the local community was recorded between 2006 and 2007 and summarised by Sheffield City Council in the Ellesmere Green proposals: Design and access statement (2006–2007). This involved a series of surveys, consultations, meetings, and interviews with business owners, community members, and leaders (See Figure 3a,b).

Figure 3.

(a) The Old Ellesmere Green (2012). (b) The Current Ellesmere Green. ©Burngreave Messenger Issue 101, August 2012).

However, the process did not regard the religious or cultural affiliation of the community groups in the area (considering the predominance of the 42.3% of Muslims in Burngreave at the time); it referred to them according to their ethnic background instead by stating all non-White community members as BAEM (Black and Ethnic Minorities). In addition, the majority of people who engaged with the proposed project were White, with 54% and 62% in the second and third phases of the process, except the business owners, who were mainly from the BAEM community, particularly Muslims. This seems disproportionate in an area where BAEM represents over 63% of the total population. In July 2012, a further public consultation was carried out by distributing questionnaires to community buildings, such as Sorby House and the local library, for residents to fill out. However, there is no accessible record found—so far—of the details of the community participation between 2007 and 2012, except some press declarations from the council development officer affirming that some changes to the original proposals had been made following this consultation (Burngreave Messenger issue 101, August 2012).

When interviewed, the developing officer responsible for the project at the time confirmed that the project was launched in 2012 and had little if any knowledge of the previous round of public consultation between 2004 and 2007, as it was held as part of the Burngreave New Deal for Communities between 2004 and 2007. However, different methods were used at the time to engage with the local community in 2012. These included contacting local community organisations and activists, talking to businesses in the surrounding area, and organising activities and public meetings.

“We printed 1000s of leaflets and invited people to come along. They were dropping in the café. All the community organisations that represented anybody in the area were invited ““We talked to local members. We talked to the local key stakeholders in order to organise our thoughts in terms of Ellesmere Green….” “We did 1000s of leaflets about this fun day in 2012. Come and give your views about what you want to do, and organise a lot of activities; I also organised the public meetings…”(The development officer at the time of the project)

However, none of the local Muslims interviewed—including business owners— took part in this, although some shop owners confirmed that there were consultation meetings and knew people who attended them.

“No, I was away, but they (the council) have spoken to my uncle and few people….”(a 53-year-old community member)

“Yeah, some people, but I wasn’t there, I was abroad. Some people went, well. Everybody put their issues, and everybody who’s put their story away or put their comments, they got nothing back”(a 58-year-old community member and business owner)

Furthermore, others denied that they were consulted or knew anyone who was consulted, which is probably due to the lack of precise representation amongst the local community organisations on the one hand and the minimal turnout to the organised consultation meetings and activities on the other.

“No, they didn’t contact me”(a 40-year-old community member and business owner)

“No, I wasn’t aware of the consultation”(The chair of the ISRAAC community centre)

In addition, Emily Haimeed (Burngreave Messenger journalist) visited the area in July 2012 and talked to some regular users of the green space. She found that many of them needed to be made aware of the changes that were still on paper before the works started in the summer of 2013 (Burngreave Messenger August 2012 Issue 101).

The development officer also confirmed that it is an uneasy task to engage the community in Burngreave, despite organising events in the area and extra measures that were taken at the time, including printing leaflets in different languages. The local councillor, Safiya, had a similar view that people in the area do not engage in any public activities.

“One thing I found is that, and maybe this isn’t dissimilar to other areas, but Muslims, it is very difficult to engage people, very difficult.”(Development officer at Sheffield city council)

“The community needs to complain a lot. They need to ring; they need to attend public meetings…”Cllr Safiya (Local councillor for Burngreave ward)

Nevertheless, involving Muslim communities in such projects can be challenging for developers and local authorities. Among the reasons for this are the disproportionate representation of diversity within the Muslim community during participation, on the one hand, and the particularity of Muslim religious and cultural practices that require special attention to include them (Nawratek and Mehan 2020). For example, Al-Rahman Mosque and Cultural Centre are across the road from the green space. The Imam was there during the time of the public consultation and had not been part of the process, despite the Mosque’s use of the space as an Eid (Islamic festive) praying site for the early years of the project completion. In fact, elderly Muslims used the space as a socialising space between the daily prayers before and after entering the Mosque.

“We used to pray even the Eid prayer in the green space” “It was a great idea, a park for the elderly where they sit, relax, and drink tea, excellent.”

“…it became one of the nicest places, where the elderly can sit and chat after the prayers, and before they go home”(a 53-year-old community member)

Therefore, the rightful representativeness of the Muslim community is different from the traditional local “secular” community organisations’ representativeness and is more attached to their religious practices.

Though initially welcomed by the local Muslim community, Ellesmere green is now seen as a haven for drug addicts and anti-social behaviour by many. It is thought to cause more damage to the local community than gain, particularly at social and economic levels. This also affects women’s presence, as they avoid frequenting the area, fearing the unexpected behaviours of these drug addicts. Thus, the project perimeter turned from space to bring communities together into a setting where certain community groups, such as women and children, were excluded. Moreover, this space’s geographical and religious attachment to the local Muslims’ outlook amplifies their frustration.

“Initially it (the green space) was pleasing; it looked like a nice place...”(a 19-year-old community member)

“People used to sit there in the summertime, now there is not any sitting within the space at all. It is impossible to sit there.”

“our kids can’t play there, parents can’t sit there, women can’t go there, it became a den for the drug addicts”(a 53-year-old community member)

In contrast, some community members sympathise with these individuals and perceive them as victims of the authorities’ negligence and mental health issues. Again, these were presented and perceived concerning the Islamic faith and Muslim customs. For Muslims, drug use is not just a criminal issue but also anti-religious behaviour that has long-lasting consequences on current and future religious and societal identity.

“I tell them (drug addicts) how it is bad, and obviously, they do understand, but I always try my best to teach them about my religion, and some do listen, some don’t, but in my opinion, all they need is help, and I feel the local authorities have neglected them”(a 19-year-old community member)

“People who are feeling down, lost, unwanted…. because I used to be a drug addict myself, and an alcoholic. So, I know how to talk to those people”(a 58-year-old community member and business owner)

In summary, the Muslim participatory attitude towards designing a secular urban project is akin to their approach to building a mosque or any explicitly religious space. Mostly driven and informed by their cultural and religious practices at the local level. On the other hand, it is unclear whether this is due to the local authority’s resistance to approaching secular spaces from the community’s religious perspective. This may be simply because of the lack of understanding of the interconnectivity between secular and sacred spaces in Muslims’ everyday life practices.

5. Conclusions

Within Britain, community cohesion and integration are narrowly constructed. As Phillips (2006) suggests, “much of the discourse surrounding the development of ‘parallel lives’ within multi-ethnic Britain has privileged discussions about ethnicity and cultural difference at the expense of racialised inequalities in power and status. Given the ambiguous, contradictory, and contested nature of multicultural Britain, the success of this vision of community cohesion would seem to be predicated on what has been referred to as the “containment of cultural differences,” especially those differences perceived as incompatible with white/non-Muslim Britishness” (Phillips 2006, p. 38). While successive governments have made recommendations regarding tackling this issue, it is still necessary to implement integrated approaches by taking advantage of development and regeneration projects to address segregation.

The findings of the case study part on the Ellesmere Green project suggest that despite the validity of the Council’s efforts to engage the local Muslim community in re-designing, several issues arose after the project’s completion, leading to further frustrations amongst the community. Especially when considering that the project aimed to transform Burngreave into a welcoming area that attracts different community groups and improves their daily life experience. While factors such as safety and the Islamic environment—including Mosques, Halal shops and restaurants—were critical drivers for Muslims to move to Burngreave, respondents were willing to interact with other community groups in the area and outside Burngreave to be part of the wider community, which contradicts the notion of self-segregation. In examining the participation of Muslims in regeneration and development projects, the findings painted a mixed picture for local authorities regarding the interconnectedness of sacred and secular spaces from the everyday lives of Muslims and the issue of adequate representation. Religion for Muslims is more than a faith; it is a tool that generates their social, cultural, and religious practices. Thus, engaging Muslims requires a robust approach that maximises the manifestation of their views regardless of the nature of the sacristy or secularity of the space they and/or local authorities intend to improve. At present, many perceive Ellesmere Green as a home for drug addicts and anti-social behaviours. For many local Muslims, it is an extension of their social and religious practices taken away from their space, deepening their feeling of loss of belonging and ownership.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.T., A.M. and K.N.; methodology, F.T.; software, F.T.; validation, F.T., K.N. and A.M.; formal analysis, F.T.; investigation, F.T.; resources, F.T., A.M. and K.N.; data curation, F.T.; writing—original draft preparation, F.T., K.N. and A.M. writing—review and editing, F.T., K.N. and A.M.; visualization, F.T.; supervision, K.N. and A.M.; project administration, A.M. funding acquisition, no external funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Jessica Stuckemeyer affiliated with Texas Tech University for her invaluable help and support throughout the proofreading of the draft.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aigbavboa, C. O., and Wellington Didibhuku Thwala. 2011. Community participation for housing development. Paper presented at 6th Built Environment Conference Community Participation for Housing Development, Sydney, Johannesburg, South Africa, July 31–August 2; pp. 418–28. [Google Scholar]

- Alinsky, Saul. 1972. Rules for Radicals. New York: Vantage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, Ash. 2002. Ethnicity and the multicultural city: Living with diversity. Environment and Planning A 34: 959–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, João Ferreira. 2012. Survey on Architectural Policies in Europe. European Forum for Architectural Policies. Ordem dos Arquitectos. Available online: http://www.efap-fepa.org/docs/EFAP_Survey_Book_2012.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Burns, Danny, Frances Heywood, Marilyn Taylor, Pete Wilde, and Mandy Wilson. 2004. Making Community Participation Meaningful. Bristol: The Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cantle, Ted. 2001. Community Cohesion: A Report of the Independent Review Team. London: Home Office London. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Louise. 2016. The Casey Review: A Review into Opportunity and Integration (Issue December). London: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Architecture and Built Environment (CABE). 2008. Inclusion by Design: Equality, Diversity and the Built Environment. Available online: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/inclusion-by-design.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Communities and Local Government (CLG). 2009. The Pakistani Muslim community in England Understanding Muslim Ethnic Communities. Available online: http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/communities/pdf/1170952.pdf%5Cnpapers3://publication/uuid/309E40AE-E48B-4DD8-8486-939E088E5890 (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Conway, P. 1999. Forced marriage. Airline Business 1999: 54. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff, Paul. 1965. Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 31: 331–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, Okan Murat. 2012. A new approach for participative urban design: An urban design study of Cumhuriyet urban square in Yozgat Turkey. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning 5: 122–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, Nicola. 2008. Does the quality of the built environment affect social cohesion? Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers Urban Design and Planning 161: 105–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, John. 2002. Building Cohesive Communities: A Report of the Ministerial Group on Public Order and Community Cohesion. London: Home Office Publisher, p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, Eleanor. 2017. The Uses and Usefulness of Participation. London: The Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London. [Google Scholar]

- EFAP. 2012. European Forum for Architectural Policies, Survey on Architectural Policies in Europe. Available online: http://www.efap-fepa.org/docs/EFAP_Survey_Book_2012.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- European Council of Religious Leaders (ECRL). 2007. Historical Sketch of Muslims in Britain (Issue February). Oslo: European Council of Religious Leaders. [Google Scholar]

- Fuad, Ai Fatimah Nur. 2012. Muslims in Britain: Questioning Islamic and national identity. Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies 2: 215–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey Peter, Sohrab Bhagri, and Bob Reed. 2002. Emergency Sanitation. Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough. Loaghbourough: WEDC. [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzchen, Yanti M. 2021. Mosques as religious infrastructure: Muslim selfhood, moral imaginaries and everyday sociality. Central Asian Survey 41: 368–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Paul, Joanne Milner, and Tim Sharpe. 2009. A brief historical review of community technical aid and community architecture. In Architecture, Participation and Society. Oxfordshire: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski, Marek, Asma Mehan, and Krzysztof Nawratek. 2020. Kuala Lumpur: Community, Infrastructure and Urban Inclusivity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, Fethi, Michele Lobo, and Amelia Johns. 2016. Grounding Religiosity in Urban Space: Insights from multicultural Melbourne. Australian Geographer 47: 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehan, Asma. 2020. Radical Inclusivity. In Vademecum: 77 Minor Terms for Writing Urban Spaces. Edited by Klaske Maria Havik, Kris Pint, Svava Riesto and Henriette Steiner. Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, pp. 126–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mehan, Asma, Krzysztof Nawratek, and Farouq Tahar. 2022. Beyond Community Inclusivity through Spatial Interventions. Writingplace 6: 136–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mehan, Asma, Krzysztof Nawratek, Faith Ng’eno, and Carolina Lima. 2022. Questioning Hegemony Within White Academia. Field 8: 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Modood, Tariq. 2003. Muslims and the Politics of Difference. Political Quarterly 74: 100–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawratek, Krzysztof, and Asma Mehan. 2020. De-colonizing public spaces in Malaysia: Dating in Kuala Lumpur. Cultural Geography 27: 615–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Deborah. 2006. Parallel Lives? Challenging Discourses of British Muslim Self-Segregation. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24: 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, Mike. 2000. Assessing community participation in local economic development—Lessons for the new urban policy. Political Geography 19: 573–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavivand Fard, Haniyeh, and Asma Mehan. 2018. Adaptive reuse of abondoned buildings for refugees: Lessons from European context. Suspended Living in Temporary Space: Emergencies in the Mediterranean Region, Lettera Ventidue Edizioni 5: 188. [Google Scholar]

- Repellino, Maria Paola, Laura Martini, and Asma Mehan. 2016. Growing Environment Culture Through Urban Design Processes 城市设计促进环境文化. Nanfang Jianzhu 2: 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Samad, Yunas. 2010. Muslims and Community Cohesion in Bradford. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Sartawi, Mohammed, and Gordon Sammut. 2012. Negotiating British Muslim identity: Everyday concerns of practicing Muslims in London. Culture and Psychology 18: 559–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirmuntt, Mariana. 2013. Ethnic Segregation and Collective Political Action in Urban England; Colchester: Department of Government, University of Essex, pp. 1–31.

- Stump, Roger W. 2008. The Geography of Religion [Electronic Resource]: Faith, Place, and Space. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Tirivangasi, Happy Mathew, Shingirai Stanley Mugambiwa, and Kemeridge Malatji. 2016. Lessons from post-apartheid South Africa for a violence imbued protest culture. Paper presented at the International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives (IPADA), Makopane, South Africa, July 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government. 2018. Integrated Communities’ Strategy Green Paper; London: UK Government.

- Varady, David. 2008. Muslim residential clustering and political radicalism. Housing Studies 23: 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Kayom, Sengendo Hannington, and M. Stephen. 2015. The Role of Community Participation in Planning Processes of Emerging Urban Centres. A study of Paidha Town in Northern Uganda. International Refereed Journal of Engineering and Science (IRJES) 4: 2319–183. [Google Scholar]

- Yabes, Ruth. 2000. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning. Landscape and Urban Planning 50: 270–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).