The Journey through the Netherworld and the Death of the Sun God: A Novel Reading of Exodus 7–15 in Light of the Book of Gates

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Theory of Parody

3. The Sun God’s Nocturnal Journey through the Underworld

The New Kingdom Netherworld Books describe the solar progress through the twelve hours of the night: the sinking into the western horizon, the topography of the different areas, the deities that populate those dark and fitfully illumined regions, the solar combat with the chaos serpent Apep, the punishment of enemies and the damned, and finally, the triumphant appearance of the solar deity in the eastern horizon.

3.1. The Book of Gates

bꜢ.k n pt ḫnty Ꜣḫtšwt.k Ꜥpp(tj) štꜢytḫꜢt.k n tꜢ jmj ḥrtdj.n n.s rꜤwjwd.tj r.s rꜤwsrq.k ḥtp.k ẖꜢt.k jmyt dwꜢtYour soul belongs to heaven, Foremost of the horizon,And it is your shadow which traverses the Shetitwhile your corpse belongs to the Earth, you who are in heaven.We restore Ra to it (the heaven),since you are separated from it, Ra.You breathe when you rest (in) your corpse, which is in the Underworld.10

Znjt(w) tp.k ꜤꜢpp znjt(w) qꜣbwnn tknw.k m wjꜣ rꜥwnn hꜣj.k r dpt-nṯrYour head is cut off, Apep, the coils chopped up.You [Apep] will not come near to the barque of Ra,You will not come near to the god’s ship.

sḫdw.k jwty ꜤḥꜤ.kḥkꜣw.k jwty gmj.k.ṯ(w)You are upside down, so that you cannot rise (again),You are bewitched so that you cannot find yourself.

nṯrw pw jmyw wjꜢḫsfyw ꜤꜢpp m nwtꜤpp.sn r dwꜢtmtsn ḫsfw ꜤꜢpp ḥr rꜤw m jmnttdwꜢtyw mꜢꜤ(w) nṯr pndwꜢtyw mꜢꜤ(w) nṯr pnThese are the gods who are in the barque,Who ward off Apep in heaven,When they proceed to the Netherworld.They are those who ward off Apep from Ra in the West,Those of the Underworld who guide this god.

3.2. Important Characters in the Book of Gates

3.2.1. The Sun God and Apep

jryw mꜢꜤt jw.sn tp tꜢꜤḥꜤw ḥr nṯr.snnjstw.sn r sḫnt tꜢr ḥwt Ꜥnḫw m mꜢꜤtWho have practiced maat when they were (still) on earth,who have fought for their god –they are summoned to the resting place of the Earth,to the temple of Him who lives on maat.

3.2.2. Sia

3.2.3. Heka

3.2.4. Mehen

jy.tj rꜤw jꜤr.k n dwꜢthmw n.k Ꜥq.k ḏsrw m mḥnWelcome, Ra, when you approach the Netherworld,Jubilation to you when you enter the protection of Mehen.

The primary function of the god Mehen in religious belief is depicted in the New Kingdom Netherworld literature. According to the Book of Amduat, the Book of Gates, and the Book of Night, Mehen ostensibly is an immense coiled serpent who stands on the night-bark of Ra, and he guides the passage of the sun-god in his Netherworld journey. Primarily, though, he encompasses Ra in his many coils, and protects him from all outside evil.

3.3. Summary

4. Examining Exodus 7–15 in Light of the Book of Gates

4.1. The Serpent Contest

4.1.1. Pharaoh and the Sun God

4.1.2. Egyptian Magicians and Heka

4.1.3. Aaron’s Devouring Snake and Apep the Devourer

4.1.4. The Egyptian Snakes and Mehen

n (j)Ꜥr.k rꜤw r ḫfty.kn (j)Ꜥr ḫfty.k rꜤwḫpr ḏsrw.k jmy mḥnꜤꜢpp ḥsbw m nsf.fYou do not approach, Ra, your enemy,and your enemy does not approach (you), Ra.Your safety is established, you who are in Mehen,while Apep is smashed in his blood.

4.1.5. The Hard Heart of Pharaoh and Sia

4.2. The Ten Plagues

Pharaoh should have realized that he was on the path to destruction. If his own magicians started matching such destructive signs, the result would certainly be harmful for Egypt. But once more Pharaoh did not act with common sense or reason. Again he was obstinate and would not listen to Moses and Aaron (v. 22), and he did not take even this to heart (v. 23).41

Rendsburg (1988, p. 7) defends this view, pointing out that the Hebrew verb חשׁך, which was used in P8, is collocated elsewhere in HB with שׁמשׁ. “Accordingly,” he notes, “this interpretation of the eighth plague, with the locusts darkening Ra, would not have been lost on the ancient Hebrew reader.”43 Rendsburg then points to a relevant Egyptian text (i.e., the Prophecy of Neferti (the 12th Dynasty)) that further sheds light on P8. According to the Egyptian text, as found in Rendsburg’s work (Rendsburg 2015, p. 254), the chief lector priest, Neferti, makes a dooming prophecy against Egypt, as follows: ỉtn ḥbs nn psd.f mꜢꜢ rḫyt nn Ꜥnḫ.tw ḥbsw šnꜤ (“the sun-disc is covered, it does not shine for people to see; no one can live, when the clouds cover”). Taking these factors into account, Rendsburg concludes that this rare phrase is “a metaphor for Ra, and by extension, the land of Egypt.” If so, then P8 is a direct attack on the supreme deity of Egypt. However, a different but non-mutually exclusive interpretation is also possible. As previously mentioned, Sia is sometimes described as being in the eye of the sun god, granting him an all-seeing ability. Hence, informed readers would have understood the covering motif as YHWH’s pulling double duty: assaulting both Ra and Sia. At this point, the audience would have also sensed that serious destruction would soon fall upon Egypt.From the Egyptian [language] we learn that “eye of the land” means nothing else but the sun, which was conceived by the Egyptians as the “eye of Re”. The Hebrews may have deemed it on religious grounds to be better, and probably also considered it on poetic grounds to be finer, to transfer the mythological conception of the eye from Re to the earth and designate the sun as עין הארץ “the eye of the land” which means the “eye of the world”, since ארץ signified for the Hebrews, as tꜣ = land did for the Egyptians, both “land” and “world”. That עין הארץ actually refers to the sun is best shown by Ex. 10, 15, where it is said that the locusts “cover עין הארץ את ‘the eye of the whole land’ so that the land was darkened”.

4.3. The Parting of the Sea

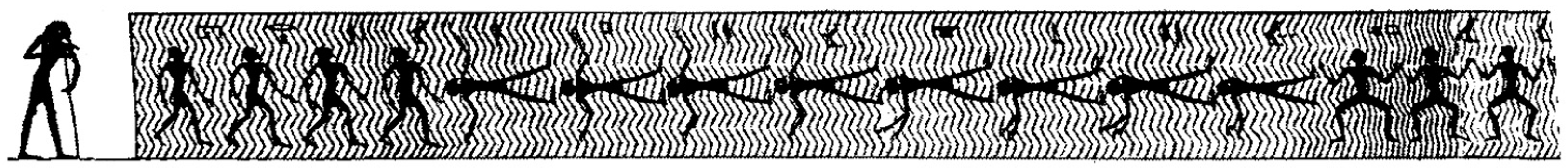

j mḥyw jmyw mwnbyw jmyw nwymꜢw rꜤw ntj Ꜥp.fm wjꜢ.f ꜤꜢ štꜢwjw.f wḏ.f sḫrw nṯrwjw.f jrj.f mḫrw Ꜣḫwjhy ꜤḥꜤw nnywm.ṯn rꜤw wḏ.f sḫrw.ṯnOh, you who float, who are in the water,those who swim, who are in the flood,look (on) Ra who passes byin his barque, with great mysteries.He cares for the godsand he provides for the Akh-spirits.Hail, stand up, you weary ones—look, Ra, he cares for you.

4.4. Twelve Miracles and Twelve Hourly Divisions

4.5. Summary

5. Two Related Issues

5.1. The Historical Point(s) of Contact between the Author of MM1–3 and BG

5.1.1. Proto-Israelite Period

5.1.2. Monarchic Israelite Period

5.1.3. Exilic or Post-Exilic Period

5.1.4. Summary

5.2. The Unexpected Association, Not Identification, of YHWH with Apep

In ancient Egypt, politics and religion are indissolubly interwoven. In its textual and pictorial records, warfare, for instance, is mostly presented in terms of religious ideology: the king is always triumphant over his enemies on behalf of the gods; enemies are always in rebellion against the established order—both political and cosmic order (Ma-at)—maintained by the king with the help of the gods. An enemy of the king is automatically an enemy of the gods and can for that reason easily be seen as an exponent of the chaotic forces threatening, time and again, the nightly fare of the gods through the netherworld. The most dangerous chaotic power here is, since the Coffin Texts, personified as the serpentine figure of Apophis [i.e., Apep], blocking the course of Re’s Solar Bark and thus blocking, in fact, the regeneration of creation in general.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Here, I follow James K. Hoffmeier’s view that the Hebrew term ים־סוף may have been derived from the Ramesside-period Egyptian term pꜢ ṯwfy—one of the lakes or bodies of water east of the Nile Delta. See Hoffmeier (2005, pp. 47–110). For the argument in favor of “Red Sea,” see Snaith (1965, pp. 395–98); Batto (1983, pp. 27–35). |

| 2 | Garrett (2014, pp. 269–72) argues similarly. |

| 3 | To be clear, I am not arguing that BG is the only or the most definitive source that stands behind MM1–3. |

| 4 | See Section 5 of this article. |

| 5 | It has been proven that parody is properly understood as a literary technique; thus, employing a theory of parody to analyze biblical literature can shed further light on that literature. See Yee (1988, pp. 565–86); Band (1990, pp. 177–95); Kynes (2011, pp. 276–310); Giorgetti (2017). |

| 6 | In order to make his parody recognizable, the parodist chooses as the original text one that both he and his intended audience are familiar with. Otherwise, the parody would not be recognizable to its readers. See Hutcheon (1985, p. 19). |

| 7 | For the most frequently found signals for parody, see Rose (1993, pp. 37–38). |

| 8 | For an excellent overview of NB, see Darnell and Darnell (2018, pp. 1–60; Pinch (2002, pp. 24–26); Hornung (1999, pp. 26–111). |

| 9 | This might have been the reason why the author of MM1–3 chose BG over the Book of the Hidden Chamber (i.e., BH; Amduat) even though they both contain similar contents. |

| 10 | Hornung and Abt (2014, pp. 214–15). For the translation, I follow the cited work with minor alterations. This work provides the vignettes and accompanying descriptions engraved on the alabaster sarcophagus of Seti I. For the corresponding text found in the different tombs during the New Kingdom, see Hornung (1979–1980, pp. 1:227–28). |

| 11 | For the Scenes, see Hornung (1979–1980, pp. 1:19, 54, 84, 107, 109). |

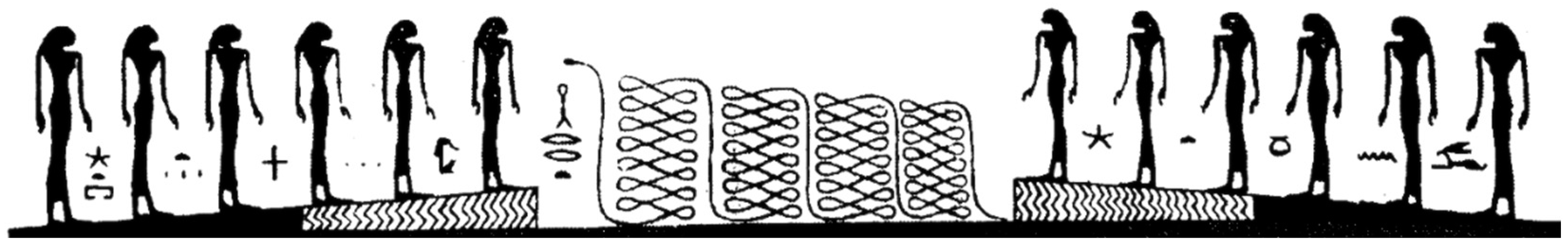

| 12 | Hornung and Abt (2014, p. 348). This portion of the image has been cropped and digitally retouched for clarity (Reprinted by permission). |

| 13 | Hornung (1982, pp. 213–14) remarks, “So the Egyptians could view maat as a substance, a material element upon which the whole world lives, which is the nourishment of the living and the dead, of gods and of men.” |

| 14 | Hence, Graves-Brown (2018, p. 5) notes that “Heka can be translated as the extra-ordinary or divine power of transformation.” |

| 15 | The Book of the Heavenly Cow, pp. 218–19. For an English translation, see Simpson (2003, pp. 289–98). |

| 16 | The hieroglyph “Mehen” sometimes appears with the “god” determinative, suggesting that Mehen was understood as a deity. See Reemes (2015, pp. 97–98). |

| 17 | Reemes (2015, p. 68) succinctly remarks, “In the New Kingdom specifically, the deceased king is received into the West, like the setting sun, by placement in a tomb which has become a veritable model of the underworld and, like the nocturnal sun, the royal mummy is conceived of as protected within the coils of Mehen, represented around the edges of sarcophagi as an ouroboros or ouroboroid serpent.” For this reason, Pinch (2002, p. 25) notes that the purpose of NB is to maintain the cosmos and aid the Egyptian Pharaoh’s transition to the afterlife through his identification with the sun god. |

| 18 | Depending on the sections of BG, Mehen either drapes over or encircles (i.e., ouroboros) the sun god. However, both poses convey the same meaning: that of divine protection. Schweizer (2010, p. 131). |

| 19 | See the annotation to the 6th Scene in BG in the upper register. Hornung and Abt (2014, p. 37; Hornung 1979–1980, p. 2:23). |

| 20 | In this article, I will interact with the received form of the text (i.e., the Masoretic Text, as set out in Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia). |

| 21 | Rendsburg (2006, pp. 201–2) succinctly remarks, “Unlike other cultures in the ancient Near East, where kings were considered human (serving as human agents of the gods, but human nevertheless), in Egypt, the Pharaoh was considered divine.” Cf. O’Connor and Silverman (1995). |

| 22 | Davies (2020, p. 482) notes that Aaron’s staff in this miracle “marks him out as the holder of special power and authority.” |

| 23 | For a thorough treatment of the association of YHWH with Apep, see Section 5.2 of this article. |

| 24 | Boorer (2016, p. 247) avers, “Although the Egyptian gods are not specifically mentioned, this is implicit since the magicians who perform or attempt to perform the signs by their secret arts are, as priests, religious functionaries in a culture, as throughout the ancient world, where the divine realm was taken as given.” |

| 25 | Dozeman (2009, p. 212) correctly comments, “Magic sustained the order of creation by warding off elements of chaos.” |

| 26 | The examples are as follows: (1) the papyrus of Khonsu-Renep (ca. 1085–945 BCE) and (2) a coffin from the 21st Dynasty belonging to Iwesemhesetmut (1189–1077 BCE). See Piankoff and Rambova (1957, pp. 59, 119); Ritner (1993, p. 224 n. 1041); Graves-Brown (2018, p. 123). |

| 27 | In BG, the sun god sometimes carries a magical wand for extra protection. Brier and Hobbs (2008, pp. 23–27, 227). |

| 28 | Davies (2020, p. 484) notes, “Aaron’s ‘staff,’ still in the form of a snake, swallows up all the magician’s ‘staffs’, presumably also still in the form of snakes.” I concur with this interpretation. |

| 29 | It is also noteworthy that although the Egyptian magicians recited magical formulae to perform their miracle, M1 is completely silent about Aaron’s use of incantations. Such a difference implies that Aaron is superior to the Egyptian magicians in terms of magical power. See Rendsburg (2015, p. 254). |

| 30 | For the importance of the staff in the context of the Exodus, see Chabas (1880, pp. 34–48); Currid (2013, pp. 111–19); Trimm (2014, p. 102; 2019, pp. 119–200) |

| 31 | Currid (1997, p. 87) remarks, “Finally, the argument that the crocodile was more in keeping with Egyptian culture than was the serpent is fallacious. The cobra, horned viper, and other snake species permeated the land of Egypt, and the figure of the serpent was attested in many more myths, spells, incantations, and narratives than was the crocodile. The venomous snake was truly the symbol or emblem of ancient Egypt.” |

| 32 | Noegel (1996, p. 48) also remarks, “I do feel that a latent polemic lurks behind the use of the word פתן, especially when used, as it is in 7:15, in conjunction with Egyptian magic.” |

| 33 | In Ugarit, tunannu was also a personification of chaos. (Cf. KTU 1.3 III 35–40) |

| 34 | Ritner writes, “Consumption entails the absorption of an object and the acquisition of its benefits or traits. Alternatively, the act can serve a principally hostile function, whereby ‘to devour’ signifies ‘to destroy’—though even here the concept of acquiring power may be retained.” |

| 35 | Four Hebrew words are employed to describe the hardness of Pharaoh’s heart: כבד, חזק, קשׁה, and הפך. For YHWH’s hardening of Pharaoh’s heart in MM1–3, see 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 12:27; 14:4, 5, 8, 17. For Pharaoh’s hardening of his own heart, see 7:13, 14, 22, 23; 8:11, 15, 28; 9:7, 34, 35; 13:15. |

| 36 | See also Shupak (2004, pp. 391–92). Grossman (2014, p. 605) aptly remarks, “Pharaoh’s heart is hardened in all the plagues, whether or not by his own choice, and the heart is therefore one of the major motifs of the narrative.” |

| 37 | Propp (1999–2006, p. 1:323) also takes the strong heart in a positive sense. See also Trimm (2014, pp. 203–6). |

| 38 | Significantly, BG employs the strong heart motif three times in a positive way, and one instance appears in connection with the successful procession of the solar barque. According to the texts in the 26th Scene in the middle register in Hour 5, Ra encourages the four gods who tow his barque toward his Osirian corpse to have strong hearts: wꜢš n jbw.ṯn wn.ṯn wꜢt nfrt r qrrwt štꜢ(wt) ḫrt (“and your hearts be strong, so that you open the perfect path to the caverns with secret content”). Hornung and Abt (2014, p. 159 ) (the italics are mine); 1979–80, p. 1:164). As seen, the strong heart motif is directly associated with the successful procession of the sun barque through the Netherworld. For other examples of the positive conception of one’s strong heart in BG, see the text in the 53rd Scene in the lower register in Hour 8 (Hornung and Abt 2014, p. 292; Hornung 1979–1980, p. 1:289) and the text in the 56th Scene in the upper register in Hour 9 (Hornung and Abt 2014, p. 313; Hornung 1979–1980, p. 1:307). |

| 39 | According to this reading, YHWH did not intervene in Pharaoh’s decision; rather, Pharaoh made his own decision, and YHWH fully accepted it. |

| 40 | See Exod 7:14, 22; 8:15, 19, 32; 9:7, 12, 34, 35; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8, 17. |

| 41 | In this regard, MM1–3 portrays Pharaoh, who was supposed to maintain the maat of Egypt, as the Apep-like figure who destroyed the maat by bringing more chaos down upon Egypt. In doing so, the Israelite author subverts the typical expectations of BG, turning Egyptian hubris on its head. Cf. Day (1985, pp. 88–101). |

| 42 | Based on the close parallels of wording between P8 and P9, Davies (2020, p. 627) notes that it is proper to view PP8–10 “as a ‘triptych’ which together take the narrative forwards to its climax in the death of the firstborn.” |

| 43 | Rendsburg (2015, p. 248) points to Targum Onqulos, where it inserts the word שׁמשׁא (“sun”) in the phrase of interest, thereby yielding עין שׁמשׁא דכל ארעא (“the eye of the sun of the whole earth”). |

| 44 | For the structural paradigm of M2, see Grossman (2014, pp. 588–610). |

| 45 | For a relevant Egyptian text featuring the three days of darkness brought down upon Egypt (i.e., Setne Khamwas and Si-Osire) as an omen, see Rendsburg (2015, pp. 248–49). |

| 46 | For a brief treatment of the possible connection between the Egyptian funerary literature (i.e., the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts) featuring the motif of the eradication of the firstborn and P10, see Rendsburg (2015, p. 249–50). |

| 47 | Such an epic battle occurs in Hour 7 of BC but in Hours 10 and 11 of BG. |

| 48 | Although the crossing of the Reed Sea appears in two different genres (i.e., Exod 14 (i.e., prose) and 15 (i.e., a poem)), the two accounts are closely connected with each other via thematic and linguistic elements. Thematically, (1) the pursuit of the Egyptian army (Exod 15:9), (2) the parting of the Reed Sea (15:8, 10), and (3) the deaths of the Egyptians by drowning (15:10) are depicted in both accounts. Linguistically, Trimm (2014, p. 9 n. 32) observes the following lexical links between the prose and poetic accounts: ישׁע (14:14, 30; 15:2), לחם (14:14, 25; 15:3), כסה (14:28; 15:5, 10), רוח (14:21; 15:8, 10), רדף (14:4, 8–9, 23; 15:9), רכב (14:25; 15:4), and שׁלישׁ (14:7; 15:4). In addition to these connections, Berman (2016, pp. 93–112) argues for the coherency of the prose and poem accounts in Exod 13:17–15:19, demonstrating the likelihood that the two accounts are modeled after the Kadesh Poem of Ramesses II. Hence, these two accounts are compatible. See Craigie (1969, pp. 83–84); Propp (1999–2006, p. 1:533); Boorer (2016, p. 270, n. 148). |

| 49 | Hornung and Abt (2014, p. 120). This portion of the image has been cropped and digitally retouched for clarity (reprinted by permission). |

| 50 | Hornung and Abt (2014, pp. 138–39). This portion of the image has been cropped and digitally retouched for clarity (reprinted by permission). |

| 51 | A vignette in the 13th Scene in the lower register in Hour 3 (Hornung and Abt 2014, p. 82; Hornung 1979–1980, p. 2:92) also portrays Apep as a multi-coiled and long serpent. |

| 52 | This observation is significant because BG portrays Apep, his minions, and “the Removing One” as the only snakes who holistically possess the three qualities: (1) long, (2) multi-coiled, and (3) posing in the same gesture. |

| 53 | It has often been observed that the priestly account of the sea miracle in Exod 14 also uses various terminology concerning creation from Gen 1:1–2:4. See Ska (2006, p. 156); Römer (2009, pp. 167–68); Knauf (2010, p. 77). |

| 54 | Gunkel (2006, p. 293 n. 8); Tromp (1969, pp. 25–26); Holladay (1969, p. 124); Hyatt (1971, p. 165); Sarna (1991, p. 80); Noegel (2017, pp. 120–21); Wakeman (1973, pp. 86–87); Trimm (2014, p. 171); Cho (2019, p. 103); Oancea (2021, pp. 179–80). Commenting on the usage of ארץ in M3, Davies (2020, p. 334) notes that based on the Ugaritic literature, “ʾrṣ certainly can mean ‘the underworld’ … and passages like this one at least show the influence of such a usage.” Römer (2014, p. 145) also avers, “[T]he priestly depiction of the parting of the sea is deliberately constructed as a myth.” For the synonymous use of ארץ with שׁאול in the Pentateuch, see Num 16:32, 34; 26:10; Deut 11:6. |

| 55 | Thus, Russell (2007, p. 11) translates Exod 15:12b as follows: “The underworld swallowed them.” |

| 56 | Hornung and Abt (2014, p. 318). This portion of the image has been cropped and digitally retouched for clarity (reprinted by permission). |

| 57 | Granted, each miracle described in MM1–3 does not exactly correspond to an event that appears in each hour of BG. However, as mentioned from the outset, one should not neglect the fact that the parodist can change and alter the form and content of the precursor to make his parody fit his agenda. As Giorgetti (2017, pp. 75–76) correctly notes, “Parody usually works on an implicit and allusive level, providing signals to an intended audience as to its true ‘target.’ Thus, any intertextual references or allusions found within a parody are likely to be somewhat ambivalent or indeterminate, without the proper knowledge of the audience (or discursive community) of which the implicit message was meant to be deciphered.” Hence, one should not expect to see exact parallels in the parody discourse in terms of form and content. |

| 58 | This article also contributes to the scholarly discussion on the identity of “all the Egyptians deities” (כל אלהי מצרים) whom YHWH sets as targets as he prepares for the slaughter of the Egyptian firstborn and the splitting of the Reed Sea (Exod 12:12). According to the information gathered in this article, the sun god and his protective deities (i.e., Sia, Heka, and Mehen) are possible candidates. For a brief discussion of this issue, see Trimm (2014, pp. 175–99); Hawkins (2021, pp. 94–103). |

| 59 | My approach requires that the Israelite author would have been familiar with the myth depicted in BG. This issue is valid because BG is found in the tombs of the pharaohs and on papyri. See Hornung (1999, pp. 55–56). |

| 60 | Carr (2007, p. 39) remarks, “In recent years, at least for pentateuchal specialists, that consensus is not a thing of the past.” |

| 61 | Dozeman (2009, pp. 35–43). Davies (2020, p. 106) notes that Exodus is composed of four main elements: two non-P narratives, the P narrative, and the Song of Moses. |

| 62 | On the Persian setting of P, see further in Vink (1969, p. 61); Knauf (2000, pp. 104–5); Nihan (2007, p. 383). |

| 63 | Concerning the non-Egyptian names, Ward (1994, pp. 62–63) succinctly avers, “[T]here is every probability that native Egyptians did not give foreign names to their children. Therefore, when we find persons with non-Egyptian person names, we can generally be sure that either those persons themselves or their recent ancestors were foreign.” |

| 64 | For further discussion of the relationship between the oral domain and ancient Egyptian myths, see Baines (1991, pp. 81–105; 1996, pp. 361–77); Hollis (2001, pp. 612–15). |

| 65 | |

| 66 | Cf. Kendall (2007, p. 42) notes, “It is worth noting in this connection that in most of the New Kingdom representations of Mehen, he is shown not as a coiled serpent but as one in the pose of an ‘S’, turned sideways, with his body forming an arch over the standing figure of Re, and his forepart and head reared up again before the god. It can be no coincidence that this same S-shaped form is that of the track of play on the Senet board!” |

| 67 | Rothöhler (1999, p. 10) correctly argues that ancient Egyptian board games, including Senet, normally had religious symbolism; hence, “[o]ne cannot examine the subject of Egyptian board games without taking into account this background.” For the role of board games in understanding antiquity, see Crist et al. (2016, pp. 167–73). |

| 68 | As some scholars point out, it is possible that the Pentateuch or proto-Pentateuch could have originated in Egypt and then reached the remaining Jewish communities in the Persian empire. See Reindl (1977, pp. 49–60); Knoppers and Levinson (2007, p. 5). |

| 69 | Römer (2003, p. 22) further suggests, “In this way Exodus 7–12 can be understood as a dialogue with Egyptian culture.” |

| 70 | In addition, what Grabbe (2014, p. 81) suggests is worth quoting for our study: “We also know of many Egyptian connections with Israel and Judah at later times, from the time of the monarchy to the Persian and Hellenistic periods (cf. Isa 19:19–25; Jer 42–44), which could have been sufficient to give rise to the story in the biblical text.” |

| 71 | For Egyptian influence on the other parts of HB, see Johnston (2008, pp. 178–94); Hays (2022, pp. 1–17); Lee (2022, pp. 56–81; 2023, pp. 1–17). Hays (2008, p. 40) avers, “[S]cribes at the royal courts of Samaria and Jerusalem were no doubt quite familiar with the cultures of the surrounding nations. Then as now, commerce and diplomacy were powerful drivers of international contacts, and there is no doubt that the Judean court in the monarchic era had contact with Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Syro-Palestinian seacoast.” |

| 72 | Manassa (2013, p. 57) writes that in Egyptian historical documents, “subtle allusions can cast foreign leaders as Apep—such equations are never made outright, but created through cosmic symbolism.” |

| 73 | Trimm (2014, p. 172) suggests, “It might even be said that he [i.e., YHWH] took on the role of chaos/Yam/Mot/Tiamat/serpent in the theomachy myths, bringing chaos to Egypt and challenging Pharaoh to restore order to Egypt like Baal/Marduk/Seth.” |

| 74 | As Marzouk (2015, p. 23) (and many others) has correctly observed, unlike the typical Chaoskampf in the ancient Near East, YHWH “does not enter into combat with the sea, but rather uses the sea as an instrument for the destruction of the Egyptians.” See also Cross (1973, p. 131); Trimm (2014, pp. 166–73). |

References

- Adams, Judith E., and Chrissie W. Alsop. 2008. Imaging in Egyptian Mummies. In Egyptian Mummies and Modern Science. Edited by A. Rosalie David. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, James P. 2014. Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Bernhard W. 1959. Understanding the Old Testament. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Bernhard W. 1994a. From Creation to New Creation: Old Testament Perspectives. Minneapolis: Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Bernhard W. 1994b. The Slaying of the Fleeing, Twisting Serpent: Isaiah 27:1 in Context. 1994. In Uncovering Ancient Stones: Essays in Memory of H. Neil Richardson. Edited by Lewis M. Hopfe. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Assem, Rehab. 2012. The God Ḥw—A Brief Study. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 41: 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 2014. From Akhenaten to Moses: Ancient Egypt and Religious Change. Cairo: AUC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 2018. Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ataç, Mehmet-Ali. 2018. Art and Immortality in the Ancient Near East. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck, Richard E. 1991. Ancient Near Eastern Mythography as It Relates to Historiography in the Hebrew Bible: Genesis 3 and the Cosmic Battle. In The Future of Biblical Archaeology: Reassessing Methodologies and Assumptions. Edited by James K. Joffmeier and Alan Millard. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 328–57. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 1991. Egyptian Myth and Discourse: Myth, Gods, and the Early Written and Iconographic Record. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 50: 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, John. 1996. Myth and Literature. In Ancient Egyptian Literature: History and Forms. Edited by Antonio Loprieno. New York: E. J. Brill, pp. 361–77. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 2007. Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Band, Arnold J. 1990. Swallowing Jonah: The Eclipse of Parody. Prooftexts 10: 177–95. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, George A. 1893. Tiamat. Journal of the American Oriental Society 18: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batto, Bernard F. 1983. The Reed Sea: Requiescat in Pace. JBL 102: 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batto, Bernard F. 2015. Mythic Dimensions of the Exodus Tradition. In Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture and Geoscience. Edited by Thomas Levy, Thomas Schneider and William H. C. Propp. New York: Springer, pp. 187–96. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, Joshua. 2016. The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II and the Exodus Sea Account (Exodus 13:17–15:19). In “Did I Not Bring Israel Out of Egypt?”: Biblical, Archaeological, and Egyptological Perspectives on the Exodus Narratives. BBRSup 13. Edited by James K. Hoffmeier, Alan R. Millard and Gary A. Rendsburg. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Boorer, Suzanne. 2016. The Vision of the Priestly Narrative: Its Genre and Hermeneutics of Time. AIIL 27. Atlanta: SBL. [Google Scholar]

- Boylan, Patrick. 1922. Thoth, the Hermes of Egypt: A Study of Some Aspects of Theological Thought in Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brier, Bob, and Hoyt Hobbs. 2008. Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians, 2nd ed. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, Eugene. 2012. Exodus. Edited by H. Wayne House and William D. Barrick. EEC. Bellingham: Lexham Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, David M. 2007. The Rise of Torah. In The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance. Edited by Gary N. Knoppers and Bernard M. Levinson. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chabas, François J. 1880. L’Usage des Bâtons de Main chez les Hébreux et dans L’ancienne Égypte. AMG 1: 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, Robert B. 1996. Divine Hardening in the Old Testament. BibSac 153: 410–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Paul K.-K. 2019. Myth, History, and Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crist, Walter, Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi, and Alex de Voogt. 2016. Ancient Egyptians at Play: Board Games Across Borders. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Craigie, Peter C. 1969. The Conquest and Early Hebrew Poetry. TB 20: 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, Frank M. 1973. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of Religion of Israel. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Currid, John D. 1997. Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Baker. [Google Scholar]

- Currid, John D. 2013. Against the Gods: The Polemical Theology of the Old Testament. Wheaton: Crossway. [Google Scholar]

- Darnell, John C. 2004. The Enigmatic Netherworld Books of the Solar Osirian Unity: Cryptographic Compositions in the Tombs of Tutankhamun, Ramesses VI, and Ramesses IX. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Darnell, John C., and Colleen M. Darnell. 2018. The Ancient Egyptian Netherworld Books. WAW 39. Atlanta: SBL. [Google Scholar]

- David, A. Rosalie. 2008a. Egyptian Mummies: An Overview. In Egyptian Mummies and Modern Science. Edited by A. Rosalie David. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- David, A. Rosalie. 2008b. The Ancient Egyptian Medical System. In Egyptian Mummies and Modern Science. Edited by A. Rosalie David. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 181–94. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Graham I. 2020. Exodus 1–18: A Critical and Exegetical Commentary. ICC. New York: T. & T. Clark, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Day, John. 1985. God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea: Echoes of a Canaanite Myth in the Old Testament. UCOP 35. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delcor, Mathias. 1993. Remarques sur la datation du Ps 20 comparée à celle du psaume araméen apparenté dans le papyrus Amherst 63. In Mesopotamica— Ugaritica—Biblica: Festschrift für Kurt Bergerhof zur Vollendung seines 70. Lebensjahres am 7. Mai 1992. Edited by Manfried Dietrich and Oswald Loretz. AOAT 232. Kevelaer: Butzon und Bercker, Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukrichener, pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dell, Katharine J. 2017. Job: An Introduction and Study Guide Where Shall Wisdom be Found? London: T. & T. Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Dentith, Simon. 2000. Parody. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dieleman, Jacco. 2019. Egypt. In Guide to the Study of Ancient Magic. Edited by David Frankfurter. Leiden: Brill, pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dozeman, Thomas B. 1996. God at War: Power in the Exodus Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dozeman, Thomas B. 2006. The Commission of Moses and the Book of Genesis. In A Farewell to the Yahwist? The Composition of the Pentateuch in Recent European Interpretation. SBLSS 34. Edited by Thomas B. Dozeman and Konrad Schmid. Atlanta: SBL, pp. 107–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dozeman, Thomas B. 2009. Exodus. ECC. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Dunand, Françoise, and Christiane Zivie. 2004. Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fretheim, Terence E. 2005. God and World in the Old Testament: A Relational Theology of Creation. Nashville: Abingdon. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Duane A. 2014. A Commentary on Exodus. KEL. Grand Rapids: Kregel. [Google Scholar]

- Garthoff, B. W. B. 1988. Merneptah’s Israel Stela, A Curious Case of Rites de Passage? In Funerary Symbols and Religion: Essays Dedicated to Professor M.S.H.G. Heerma van Voss. Edited by Jacques H. Kamsta, Hellmuth Milde and Kees Wagtendonk. Kampen: J. H. Kok, pp. 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgetti, Andrew D. 2017. Building a Parody: Genesis 11:1–9, Ancient Near Eastern Building Account, and Production-Oriented Intertextuality. Ph.D. dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gottwald, Norman. 1959. Alight to the Nations. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Grabbe, Lester L. 2014. Exodus and History. In The Book of Exodus: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation. VTSup 164. Edited by Thomas Dozeman, Craig A. Evans and Joel N. Lohr. Leiden: Brill, pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, Fritz. 1994. La Magie Dans L’Antiquité GréCo-Romaine: Idéologie et Pratique. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Graves-Brown, Carolyn. 2018. Daemons & Spirits in Ancient Egypt. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greidanus, Sidney. 2018. From Chaos to Cosmos: Creation to New Creation. Wheaton: Crossway. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Jonathan. 2014. The Structural Paradigm of the Ten Plagues Narrative and the Hardening of Pharaoh’s Heart. VT 64: 588–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunkel, Hermann. 1964. The Legends of Genesis. New York: Schocken. [Google Scholar]

- Gunkel, Hermann. 2006. Creation and Chaos in the Primeval Era and the Eschaton: A Religio-Historical Study of Genesis 1 and Revelation 12. Translated by K. William Whitney Jr.. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, George. 1990. Egyptian Myths (The Legendary Past). Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Ralph K. 2021. Discovering Exodus: Content, Interpretation, Reception. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, Christopher B. 2008. Echoes of the Ancient Near East? Intertextuality and the Comparative Study of the Old Testament. In The Word Leaps the Gap: Essays on Scripture and Theology in Honor of Richard B. Hays. Edited by J. Ross Wagner, C. Kavin Rowe and A. Katherine Grieb. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 20–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, Christopher B. 2022. A Hidden God: Isaiah 45’s Amun Polemic and Message to Egypt. VT 72: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeier, James K. 2005. Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holladay, William L. 1969. ʾEreṣ—‘Underworld’: Two More Suggestions. VT 19: 123–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, Glenn S. 2009. Gods in the Desert: Religions of the Ancient Near East. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Hollis, Susan T. 2001. Oral Tradition. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Edited by Donald B. Redford. Oxford: Oxford University, vol. 2, pp. 612–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hooke, S. H. 1963. Middle Eastern Mythology. Mineola: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 1979–1980. Das Buch von den Pforten des Jenseits: Nach den Versionen des Neuen Reiches. AH 7 and 8. Geneva: Éditions de Belles Lettres, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 1982. Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many. Translated by John Baines. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 1999. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 2002. Exploring the Beyond: The Tomb of a Pharaoh, the Amduat, the Litany of Re. In The Quest for Immortality: Treasures of Ancient Egypt. Edited by Erik Hornung and Betsy Bryan. New York: National Gallery of Art, pp. 24–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik, and Theodor Abt. 2014. The Egyptian Book of Gates. Zurich: Living Human Heritage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Huehnergard, John. 1987. Ugaritic Vocabulary in Syllabic Transcription. HSS 32. Atlanta: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon, Linda. 1985. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. New York: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt, J. P. 1971. Exodus. NCBC. London: Oliphants. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Gordon H. 2008. Genesis 1 and Ancient Egyptian Creation Myths. BibSac 165: 178–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, Leon R. 2021. Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, Othmar, and Christoph Uehlinger. 1998. Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel. Translated by Thomas H. Trapp. Minneapolis: Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Barry J. 2018. Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, T. 2007. Mehen: The Ancient Egyptian Game of the Serpent. In Ancient Board Games in Perspective: Papers from the 1990 British Museum Colloquium, with Additional Contributions. Edited by Irving L. Finkel. London: The British Museum Press, pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kister, Menahem. 2019. Psalm 20 and Papyrus Amherst 63: A Window to the Dynamic Nature of Poetic Texts. VT 70: 426–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloos, Carola. 1986. Yhwh’s Combat with the Sea: A Canaanite Tradition in the Religion of Ancient Israel. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Knauf, Ernst A. 2000. Die Priesterschrift und die Geschichten der Deuteronomisten. In The Future of the Deuteronomistic History. BETL 147. Edited by Thomas Römer. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 101–18. [Google Scholar]

- Knauf, Ernst A. 2010. Zur priesterschrifdichen Rezeption der Schilfmeer-Geschichte in Ex 14. In Schriftauslegung in der Schrift. Edited by Reinhard G. Kratz, Thomas Krüger and Konrad Schmid. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Knoppers, Gary N., and Bernard M. Levinson. 2007. How, When, Where, and Why Did the Pentateuch Become the Torah? In The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance. Edited by Gary N. Knoppers and Bernard M. Levinson. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kynes, Will. 2011. Beat your Parodies into Swords, and Your Parodied Books into Spears: A New Paradigm for Parody in the Hebrew Bible. BibInt 19: 276–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sanghwan. 2022. Moses, the Lifter of the Sky: A Novel Reading of Exodus 17:8–16 in Light of the Heliopolitan Cosmogony. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 47: 56–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sanghwan. 2023. Killing Pharaohs in Exodus: The Anonymity of the Egyptian Kings, the Deconstruction of Their Individuality, and the Egyptian Practice of Damnatio Memoriae. Religions 14: 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesko, Barbara S. 1994. Rank, Roles, and Rights. In Pharaoh’s Workers: The Villagers of Deir El Medina. Edited by Leonard H. Lesko. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, Shirley P. 1982. Familiar Mysteries: The Truth in Myth. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luft, Ulrich H. 2001. Religion. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Edited by Donald B. Redford. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 3, pp. 139–45. [Google Scholar]

- Manassa, Colleen. 2003. The Great Karnak Inscription of Merneptah: Grand Strategy in the 13th Century BC. YES 5. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manassa, Colleen. 2007. The Late Egyptian Underworld: Sarcophagi and Related Texts from the Nectanebid Period. ÄAT 72. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Manassa, Colleen. 2010. Defining Historical Fiction in New Kingdom Egypt. In Opening the Tablet Box: Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Benjamin R. Foster. CHANE 42. Edited by Sarah C. Melville and Alice L. Slotsky. Leiden: Brill, pp. 245–69. [Google Scholar]

- Manassa, Colleen. 2013. Imagining the Past: Historical Fiction in New Kingdom Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marzouk, Safwat. 2015. Egypt as a Monster in the Book of Ezekiel. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, L. Michael. 2020. Exodus Old and New: A Biblical Theology of Redemption. ESBT. Downers Grove: InterVarsity. [Google Scholar]

- Morson, Gary S. 1989. Parody, History and Metaparody. In Rethinking Bakhtin: Extensions and Challenges. Edited by Gary S. Morson and Caryl Emerson. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, Candidia R., and Jeffrey Stackert. 2012. The Devastation of Darkness: Disability in Exodus 10: 21–23, 27, and Intensification in the Plagues. The Journal of Religion 92: 362–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, Bunyan D. 1962. Song of the Vineyard: A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Nihan, Christophe. 2007. From Priestly Torah to Pentateuch: A Study in the Composition of the Book of Leviticus. FAT 2.25. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Noegel, Scott B. 1996. Moses and Magic: Notes on the Book of Exodus. Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 24: 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Noegel, Scott B. 2017. God of Heaven and Sheol: The ‘Unearthing’ of Creation. Hebrew Studies 58: 119–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, Constantin. 2021. Water and Death as Metaphor in Jonah’s Psalm. Revue Biblique 128: 173–89. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, D., and D. P. Silverman, eds. 1995. Ancient Egyptian Kingship. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ortlund, Eric N. 2010. Theophany and Chaoskampf: The Interpretation of Theophanic Imagery in the Baal Epic, Isaiah, and the Twelve. GUS 5. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piankoff, Alexander, and Natacha Rambova. 1957. Mythological Papyri: Egyptian Religious Texts and Representations I. Bollingen Series XL; New York: Pantheon Books, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Piccione, Peter A. 1990. Mehen, Mysteries, and Resurrection from the Coiled Serpent. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 27: 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinch, Geraldine. 1994. Magic in Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinch, Geraldine. 2002. Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Propp, William. 1999–2006. Exodus. AB. New York: Doubleday, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Quirke, Stephen. 1992. Ancient Egyptian Religion. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reemes, Dana M. 2015. The Egyptian Ouroboros: An Iconological and Theological Study. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Reindl, Joseph. 1977. Der Finger Gottes und die Macht der Götter. Ein Problem des ägyptischen Diasporajudentums und sein literarischer Niederschlag. In Dienst der Vermittlung: Festschrift Priesterseminar Erfurt. ETS 37. Edited by Wilhelm Ernst, Konrad Feiereis and Fritz Hoffmann. Leipzig: St. Benno Verlag, pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rendsburg, Gary A. 1988. The Egyptian Sun-God Ra in the Pentateuch. Henoch 10: 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rendsburg, Gary A. 2006. Moses as Equal to Pharaoh. In Text, Artifact, and Image: Revealing Ancient Israelite Religion. BJS 346. Edited by Gary M. Beckman and Theodore J. Lewis. Providence: Brown University Press, pp. 201–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rendsburg, Gary A. 2015. Moses the Magician. In Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture and Geoscience. Edited by Thomas Levy, Thomas Schneider and William H. C. Propp. New York: Springer, pp. 243–58. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Barbara A. 2016. The Theology of Hathor of Dendera: Aural and Visual Scribal Techniques in the Per-Wer Sanctuary. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rikala, Mia. 2007. Once More with Feeling: Seth the Divine Trickster. Studia Orientalia Electronica 101: 219–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ritner, Robert K. 1993. The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice. SAOC 54. Chicago: Oriental Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Römer, Thomas. 2003. Competing Magicians in Exodus 7–9: Interpreting Magic in the Priestly Theology. In Magic in the Biblical World: From the Rod of Aaron to the Ring of Solomon. Edited by Todd Klutz. London: T. & T. Clark International, pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Römer, Thomas. 2008. Moses Outside the Torah and the Construction of a Diaspora Identity. Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 8: 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römer, Thomas. 2009. The Exodus Narrative according to the Priestly Document. In The Strata of the Priestly Writings: Contemporary Debate and Future Directions. ATANT 95. Edited by Sarah Shectman and Joel S. Baden. Zurich: Theologischer Verlag Zurich, pp. 157–74. [Google Scholar]

- Römer, Thomas. 2014. From the Call of Moses to the Parting of the Sea: Reflections of the Priestly Version of the Exodus Narrative. In The Book of Exodus: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation. VTSup 164. Edited by Thomas Dozeman, Craig A. Evans and Joel N. Lohr. Leiden: Brill, pp. 121–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Margaret A. 1993. Parody: Ancient, Modern, and Post-Modern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Margaret A. 2011. Pictorial Irony, Parody, and Pastiche: Comic Interpictoriality in the Arts of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Bielefeld: Aisthesis Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Rothöhler, B. 1999. Mehen, God of the Boardgames. JBGS 2: 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Brian D. 2007. The Song of the Sea: The Date of Composition and Influence of Exodus 15:1–21. SBL 101. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Sarna, Nahum M. 1991. Exodus. JPS Torah Commentary. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, Andreas. 2010. The Sungod’s Journey through the Netherworld: Reading the Ancient Egyptian Amduat. Edited by David Lorton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shupak, Nili. 1985. Some Idioms Connected with the Concept of ‘Heart’ in Egypt and the Bible. In Pharaonic Egypt: The Bible and Christianity. Edited by Sarah Israelit-Groll. Jerusalem: Magnes, pp. 202–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shupak, Nili. 2004. ḤZQ, KBD, QŠH LĒB: The Hardening of pharaoh’s Heart in Exodus 4:1–15:21—Seen Negatively in the Bible but Favorably in Egyptian Sources. In Egypt, Israel, and the Ancient Mediterranean World: Studies in Honor of Donald B. Redford. PÄ 20. Edited by Gary N. Knoppers and Antoine Hirsch. Leiden: Brill, pp. 389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Shupak, Nili. 2005. The Instruction of Amenemope and Proverbs 22:17–24:22 from the Perspective of Contemporary Research. In Searching Out the Wisdom of the Ancients: Essays Offered to Michael V. Fox on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 203–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shupak, Nili. 2015. The Contribution of Egyptian Wisdom to the Study of Biblical Wisdom Literature. In Was There a Wisdom Tradition: New Prospects in Israelite Wisdom Studies. Edited by Mark R. Sneed and Mark R Sneed. Atlanta: SBL. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, William K., ed. 2003. The Literature of Ancient Egypt, 3rd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ska, Jean-Louis. 2006. Introduction to Reading the Pentateuch. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Smelik, Klaas A. D. 1985. The Origins of Psalm 20. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 31: 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, Norman H. 1965. ים־סוף (ymswp): The Sea of Reeds: The Red Sea. VT 15: 395–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, Brad C. 2015. Egyptian Texts relating to the Exodus: Discussions of Exodus Parallels. In Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture and Geoscience. Edited by Thomas Levy, Thomas Schneider and William H. C. Propp. New York: Springer, pp. 259–81. [Google Scholar]

- Stannish, Steven M. 2007. The Topography of Magic in the Modern Western and Ancient Egyptian Minds. Journal for the Academic Study of Magic 4: 64–89. [Google Scholar]

- Te Velde, Herman. 1970. The God Heka in Egyptian Theology. In Jaarbericht van het Voorasiatisch-Egyptisch Genootshap. Ex Oriente Lux 21. Leiden: Brill, pp. 175–86. [Google Scholar]

- Teeter, Emily. 2011. Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Török, László. 1997. The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Töyräänvuori, Joanna. 2013. The Northwest Semitic Conflict Myth and Egyptian Sources from the Middle and New Kingdoms. In Creation and Chaos: A Reconsideration of Herman Gunkel’s Chaoskampf Hypothesis. Edited by JoAnn Scurlock and Richard H. Beal. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 112–26. [Google Scholar]

- Trimm, Charlie. 2014. “YHWH Fights for Them!”: The Divine Warrior in the Exodus Narrative. GBS 58. Piscataway: Gorgias. [Google Scholar]

- Trimm, Charlie. 2019. God’s Staff and Moses’ Hand(s): The Battle against the Amalekites as a Turning Point in the Role of the Divine Warrior. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 44: 119–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, Nicholas J. 1969. Primitive Conceptions of Death and the Nether World in the Old Testament. BO 21. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Vink, Jacobus G. 1969. The Date and Origin of the Priestly Code in the Old Testament. In The Priestly Code and Seven Other Studies. OTS 15. Edited by Jacobus G. Vink. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman, Mary K. 1973. God’s Battle with the Monster: A Study in Biblical Imagery. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, William A. 1994. Foreigners Living in the Village. In Pharaoh’s Workers: The Village of Deir el Medina. Edited by Leonard H. Lesko. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, Nicolas. 1996. Myths of Power: A Study of Royal Myth and Ideology in Ugaritic and Biblical Tradition. UBL 13. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, Nicolas. 1998. Arms and the King: The Earliest Allusions to the Chaoskampf Motif and Their Implications for the Interpretation of the Ugaritic and Biblical Traditions. In “Und Mose schrieb dieses Lied auf”: Studien zum Alten Testament und zum Alten Orient; Festschrift für Oswald Loretz zur Vollendung seines 70. Lebensjahres mit Beiträgen von Freunden, Schülern und Kollegen. AOAT 250. Edited by Manfried Dietrich and Ingo Kottsieper. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 833–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yahuda, A. S. 1933. The Language of the Pentateuch in its Relation to Egyptian. London: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, Gale A. 1988. The Anatomy of Biblical Parody: The Dirge Form in 2 Samuel 1 and Isaiah 14. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 50: 565–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zevit, Ziony. 1990. The Common Origin of the Aramaicized Prayer to Horus and of Psalm 20. Journal of the American Oriental Society 110: 213–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivie, Alain. 1982. Tombes rupestres de la falaise du Bubasteion à Saqqarah, campagnes 1980–1981. Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Egypte Le Caire 68: 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zivie, Alain. 2010. The ‘Sage’ of ‘Aper-El’s Funerary Treasure. In Offerings to the Discerning Eye: An Egyptological Medley in Honor of Jack A. Josephson. CHANE 38. Edited by Sue H. D’Auria. Leiden: Brill, pp. 349–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zivie, Alain. 2018. Pharaoh’s Man, ‘Abdiel: The Vizier with a Semitic Name. Biblical Archaeology Review 44: 22–31, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S. The Journey through the Netherworld and the Death of the Sun God: A Novel Reading of Exodus 7–15 in Light of the Book of Gates. Religions 2023, 14, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030343

Lee S. The Journey through the Netherworld and the Death of the Sun God: A Novel Reading of Exodus 7–15 in Light of the Book of Gates. Religions. 2023; 14(3):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030343

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sanghwan. 2023. "The Journey through the Netherworld and the Death of the Sun God: A Novel Reading of Exodus 7–15 in Light of the Book of Gates" Religions 14, no. 3: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030343

APA StyleLee, S. (2023). The Journey through the Netherworld and the Death of the Sun God: A Novel Reading of Exodus 7–15 in Light of the Book of Gates. Religions, 14(3), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030343