1. Introduction

This study is a quantitative study of Chinese temples in Johor through the construction of the Malaysian Historical Geographical Information System (MHGIS) in an attempt to map out the Chinese religion and beliefs in the region in order to achieve a deeper understanding of the history and cultural changes of the local Chinese community. Johor is one of the states of Malaysia, located at the southernmost tip of the Malay Peninsula, across the waters from Singapore. In the 19th century, the rulers of Johor introduced Kangchu System

1 to attract a large number of Chinese laborers to the region to cultivate pepper and gambier, which led to the emergence of a number of Chinese settlements in the region (

Onn 2017, p. 8). Then, Chinese immigrants built temples throughout Johor, carrying on a religious culture of Chinese origin. As Johor is geographically close to Singapore, they are inextricably linked in terms of historical development, to the extent that some scholars regard the area where Johor, Singapore and the Indonesian Riau Islands are located as the Golden Triangle of the Malay Peninsula (

Pek et al. 2019). However, most religious studies have focused on Singapore, while research on the Chinese in Johor is still relatively scarce. In terms of systematic and comprehensive research, David K. Y. Chng, Kenneth Dean, and Hue Guan Thye have all conducted large-scale field surveys and collected inscriptions from Chinese organizations all over Singapore (

Dean and Hue 2016). Of the major local studies on the Chinese in Johor in recent years is the “Collaborative Project for the Collection of Teochew Historical Materials on Johor “(搜集柔佛潮州史料合作计划) led by the Southern University College in 2001. In the following years, the Southern University College also launched the “Johor Hakka History Collection Project” (柔佛客家人史料搜集计划) and the “Johor Hainanese History Collection Project” (柔佛海南人史料搜集计划) in 2004 and 2006, and conducted a large number of field surveys and oral history records. These projects have made great contributions to the study of Chinese in Johor. However, the focus of these major projects was not on the study of temples and beliefs but on the collection of information on dialect groups. These studies can be considered cutting-edge projects in Johor research, but there is still much room for improvement in terms of coverage and the collection of inscriptions. Even though the study of Chinese temples and beliefs in Johor has gained increasing attention from Malaysian scholars in recent decades, most of the studies are case studies of prominent individual temples in the region or focus on a particular belief,

2 while the study of Chinese temples and beliefs in Johor as a whole lacks a holistic and systematic approach.

In the 1980s, scholars of Chinese studies at home and abroad, such as Jao Tsung-I, Seiji Imahori, Chen Jing he, Chen Yu Song, Chen Tie Fan, and Wolfgang Franke, realized that in order to understand the changes in the Chinese community in Singapore and Malaysia, the temples and other cultural organisations such as dialect association, clan houses and cemeteries where the Chinese were active were essential. These scholars have conducted fieldwork in both Singapore and Malaysia and have collected many inscribed documents and artefacts of Chinese temples, which have been collated and published to enrich the study of local Chinese temples (

Jao 1969;

Takeo 1969,

1971;

Chen and Chen 1974;

Chen 1997). Among them, Wolfgang Franke and Chen Tieh Fan published three volumes of Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Malaysia in the 1980s, which included artefacts from their visits to major Chinese cultural sites in 13 states in Malaysia, with Chinese temples making up the majority of the collection, making it the first major work to outline the distribution network of Chinese temples in Malaysia in a comprehensive manner (

Franke and Chen 1982,

1983,

1985). However, while Franke and Chen have collected a wealth of information on temples, but in South Malaysia, they have focused more on Malacca, which has many ancient temples, and recorded only eight Chinese temples in Johor (

Franke and Chen 1982, pp. 145–84). Because large numbers of Chinese immigrants settled in Johor from the time of the Kangchu system, the number of Chinese temples built to the end of the last century ought to have exceeded single digits, hence Franke and Chen’s research does not completely give a true picture of Chinese religion and culture in Johor. Unfortunately, after the 1980s, there were no scholars left to conduct such a comprehensive survey, which is collecting and collating historical documents and artefacts in a systematic way of all the Chinese temples in Johor.

Although research on Johorian Chinese temples and beliefs has increased, the number of temples studied is small, or the focus is on a certain region, or focus on a particular belief study as stated above, which precludes a better understanding of the overall situation, as well as the evolution of the cultural and spiritual outlook of the local Chinese community. To address this gap, this research team will follow the footsteps of Franke and Chen and conduct fieldwork on Chinese temples in various states of peninsular Malaysia between January 2020 and September 2022 exploring more Johorian temples and searching and collating temple inscriptions. The research was not confined to centuries-old temples, but was a comprehensive search of all the Chinese temples no matter large and small that exist in Johor today, collecting, collating, and analysing temple data, and then inputting them into the Malaysian Historical Geographic Information System (MHGIS) to present the overall development and distribution of Chinese temples and beliefs in Johor via modern digital technology.

The Malaysian Historical Geographical Information System (MHGIS) was created by Dr Hue Guan Thye, Director of the Centre for Research on Southeast Asian Chinese Documents at Xiamen University Malaysia. Since Roger Tomlinson first proposed the technical term “Geographical Information System (GIS)” in 1963, GIS technology has made tremendous progress and changes after more than half a century of development. With the development of computer technology and software, various fields have begun to use GIS systems to improve their work. Since the 1980s, the expansion of GIS in the field of historical research has led to the emergence and rapid development of Historical GIS. At present, historical GIS has become the main tool of “digital humanities” research, and it is also a more cutting-edge research method in historical research nowadays. In addition to continuing to emphasize basic work, HGIS has produced various types of information, increased specialization, and begun to explore the use of various quantitative analysis tools on the basis of auxiliary cartography (

Zhao 2019).

Malaysia is a vast country with many Chinese settlements and Chinese historical units. As mentioned earlier, with the efforts of many scholar, some units have been included in their writings. However, there are still huge Chinese units left behind, waiting to be unearthed by researchers. To present the location of these temples, a written map may be sufficient for Chinese studies in a region, but to expand the research perspective to a district or even a state, it has many disadvantages in terms of accuracy, visualization, research perspective, and searchability. For this reason, the academic community is in urgent need of new tools to escape from such a dilemma. Following the successful experience of Kenneth Dean and Hue Guan Thye in SHGIS, Hue Guan Thye would like to use his experience in Singapore to bring the HGIS system into Chinese research in Malaysia, using the advantages of computers and software to solve the current problem. He is using the Singapore Historical GIS (SHGIS) as the basis for his research and extended the collection of data on overseas Chinese cultural sites to Malaysia. In contrast to the compilation and publication of temple inscriptions collected by Wolfgang Franke and others, the HGIS allows for the speedy quantitative analysis of temple data, further broadening the horizons of temple research.

MHGIS has advantages over the traditional written map in terms of ease of use, sustainability, and presentation capabilities, and has greater potential for spatial knowledge production. Previously, Dr Hue’s team had successfully used the temple data from Singapore and Malaysia to trace the development of the United Temples in Singapore and the temple network of the Malaccan leader, and deepened the understanding of the connection and influence between temples and the Chinese community (

Hue and Klan 2022;

Hue et al. 2022). The research team’s 3-year fieldwork in Johor adds to the data available in the MHGIS making a scholarly contribution and filling in research gaps as much as previous research findings. In the future, the team will continue to deepen and enrich the functions and data of MHGIS. The team plans to add historical maps from different time periods so that audiences can have a more visual view of the historical development of a region. The team also plans to continue to add Chinese units such as temples, associations, cemeteries, and schools in other states in the future to further improve Chinese studies in Malaysia.

3 2. Research Method

This study is a quantitative analysis and presentation of Chinese temple data in Johor using historical anthropological theories and methods. Historical anthropology is a new research approach and methodology in recent years, which is dedicated to the search for long-neglected folk historical data through the official document through fieldwork, and to explore the historical development of a place or region from a bottom-up perspective of society (

Zheng et al. 2012, p. 160). This research method is widely known as historical anthropology, as it combines the documentary interpretation of history with the fieldwork of anthropology. Historical anthropology focuses on going back to the historical site to obtain information, sorting out and analysing the contents of artefacts and inscriptions left behind by various cultural bodies, in order to gain a more objective and realistic picture of the historical developments in the area. Therefore, as mentioned above, in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the Chinese temple network and belief culture in Johor, Dr Hue Guan Thye visited 10 districts in Johor over the past three years to collect artefacts from local Chinese temples and explore lesser-known temples scattered around the region.

The fieldwork in Johor was conducted on temples of Chinese belief or temples established by the Chinese, and the scope of the search included cities, villages, towns, fishing villages and houses. Dr Hue Guan Thye started his research in Johor Bahru, the capital of Johor, and expanded to the northern districts of Johor Bahru, eventually covering all 10 districts of Johor. Dr Hue first photographed the temples in order to record the architecture and interior layout of the temples, and then photographed the inscriptions. When photographing inscriptions, he not only focused on the artefacts as a whole, but also on details such as the year of the artefacts and the person who donated them. When members of the temple council were present, he interviewed them to gain their perspective. In addition to interviews, he also gathered valuable documents from the council such as minutes of meetings, financial reports or land deeds as well as temple publications. The relevant materials are stored as photographs on a hard disk.

After collecting the data from the fieldwork, the research team collated and summarised the photos already stored on the hard disk together with other information obtained from the temple authorities such as publications and interview information. In the initial collation, the team will identify and classify each temple by region, postal address, district and city, the main deity, year of foundation, and artefacts, and will input the data into an Excel spreadsheet. In addition, the team also coded the data so that each data item could be filtered more quickly and various quantitative analyses could be done more quickly. For example, in the list of main deity items, “Tua Pek Gong” (大伯公) is coded MD01, MD02 for “Mazu” (妈祖), MD03 for “Guanyin” (观音) … and so on. This is to digitally classify the contents of the temples according to the different parameters so that the information can be easily compiled into the Malaysian Historical GIS. After that, the research team will input the data into the MHGIS system step by step. We plan to first input the coordinates of the temples to present the specific location of Johor temples through the map in order to have a higher and more comprehensive perspective on the distribution of Johor temples. Up to this stage, the initial stage of data compilation has been completed. The team first used the map to view the distribution characteristics of the temples in Johor. Through the systematic visualization of the distribution map, the team was able to realize that different faith cultures have their own distribution characteristics in different districts, and in doing so, identified specific questions. For example, after inputting the data into the map, we were able to find that the number of temples along the coast and rivers is much higher than the number of temples in the inland areas. This led us to further explore the reasons for this phenomenon, before concluding in our paper that there is a strong correlation between Chinese settlements and the Kangchu system, which further dialogues with and validates earlier findings in the academy. In addition, we also discovered through MHGIS that the Buddhist deity “Gautama Buddha” is found in large numbers in the southern part of Johor, especially in Johor Bahru. The presentation of the map inspired us to discuss this unique phenomenon further in the paper. Having identified a specific research question, the research team focused on the study of the region, the main deity, and the chronology as the basis for the discussion in this thesis. These three elements can better reflect the state of faith in Johor over time, as well as the state of faith in specific districts and cities in Johor.

Now, the research team has been able to use the Johor data to conduct preliminary statistical and quantitative computations. Since MHGIS is in its preliminary stage, the research team still has to use Excel’s “filter” function to compile statistics on different aspects of the temples, focusing more on the regional distribution of the temples, the main deity, and the year of founding, as these three parameters better reflect the beliefs over time, as well as the beliefs in specific districts and cities. The study begins with the overall temple data. The study first focuses on the overall number of temples. The research team counted the number of temples in each county and calculated the percentage of temples in order to visualise the percentage of temples in each county.

The team then counted the year of establishment of each temple; starting from 1800 and setting a break in the counting of temples at 50-year intervals. Finally, the team counted the number of main deities in each temple. The main deity was one of the main focuses of the study, as the main deity worshipped is the most direct indicator of the beliefs of a particular temple, and with sufficient data accumulated, it can also reflect the beliefs of the area. The team used the filtering function to count over a hundred main deities and converted all the data into totals and percentages so that the weight could be more visually derived. Based on this, the team also counted and calculated the exact number of main deities in each prefecture to find out if there were cases where a particular main deity had a larger number in a particular area. A cross-tabulation of the main deities of the temples and the year in which the temples were established was also carried out to discover, where possible, the temporal scope and trends of active belief or interest in particular main deities. These cross-tabulations of temple areas, main deities, and year of the establishment will provide a more multi-dimensional picture of Chinese temples and beliefs in Johor, and may even reflect the spiritual aspirations and needs of the Malaysian Chinese community as a whole. In addition, in the “Discussion” section, the results of the data will be compared, analysed and discussed in order to develop new ideas and findings that will further improve, deepen and even overturn the general perception of Chinese temples and beliefs in Johor.

3. Study Results

During this three-year period, Dr Hue visited 943 Chinese temples in Johor, covering all 10 districts and cities of Johor. 20,489 photographs were taken of these temples, and 20,964 pieces of temple artefacts and paper documents were collected, which is an unprecedented number alone. Detailed figures are given in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Prior to this, Wolfgang Franke and Chen Tie Fan were arguably the scholars who had conducted the most extensive fieldwork on Chinese temples in Malaysia. However, the number of Chinese temples in Johor that they visited at that time was extremely limited.

Table 3 shows that only eight Chinese temples in Johor were included in their work, which did not include temples in Kluang, Kulai, Muar and Tangkak. In total, they only discovered 19 artefacts in the Chinese temple in Johor. This is minuscule compared to the over 2000 texts from plaques, couplets and various inscriptions collected by Dry Hue Guan Thye in over 900 temples. In particular, the team’s collection of temple materials has been extended from artefacts to include various paper materials and newspaper clippings, which were recorded with high-definition digital cameras. Once the information has been collated and coded, it will be shared with the public through the Malaysian Historical GIS database.

The lack of technology and good transportation in the 1970s hampered Franke and Chen in their search for cultural units and inscriptions. As

Table 4 shows, Franke and Chen visited 397 Chinese cultural units in Malaysia over a period of ten years and collected over 1300 inscriptions. Today, using modern photographic technology, advanced electronic mapping, and digital humanities systems, the research team has been able to compile many more documents in Johor alone. It is no exaggeration to say that the research team has made an unprecedented breakthrough in the number of Chinese temples in Johor, and has done much to fill in the research gaps in this field. For example, the team has included 2 temples not recorded in the

Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Malaysia, namely, the Ling San Temple in Johor Bahru and the Tian Zun Gong, which were established in 1844 and 1856 respectively (see

Table 5). They also predate the Johor Ancient Temple (柔佛古庙), which was founded in the 1860s and is widely recognized by the local Chinese community as the first Chinese temple in Johor. Moreover, since Franke and Chen’s work was published in the 1980s, more than 40 years ago, we can further extend the horizon by including new temples that have emerged since then. This not only allows us to use the temple database to trace the local Chinese beliefs back to the mid-19th century, but also to look at the network of temples in the present-day Chinese community in Johor and compare them against each other.

3.1. Data on The Regional Distribution of Johor Temples

The next section presents the quantitative results of Chinese temples in Johor in terms of regional distribution, year of establishment and main deities worshipped. In terms of the regional distribution of the 943 temples, we found 345 Chinese temples in Johor Bahru, which has the highest percentage (36.6%) among the 10 districts in Johor, while Batu Pahat came second with 141 Chinese temples, or 14.95%, followed by Muar, Pontian, Segamat and Kluang (see

Table 6). More than half of the temples are located in Johor Bahru and Batu Pahat, with over 30% of the temples concentrated in Johor Bahru, reflecting the dominance of Chinese temples in Johor.

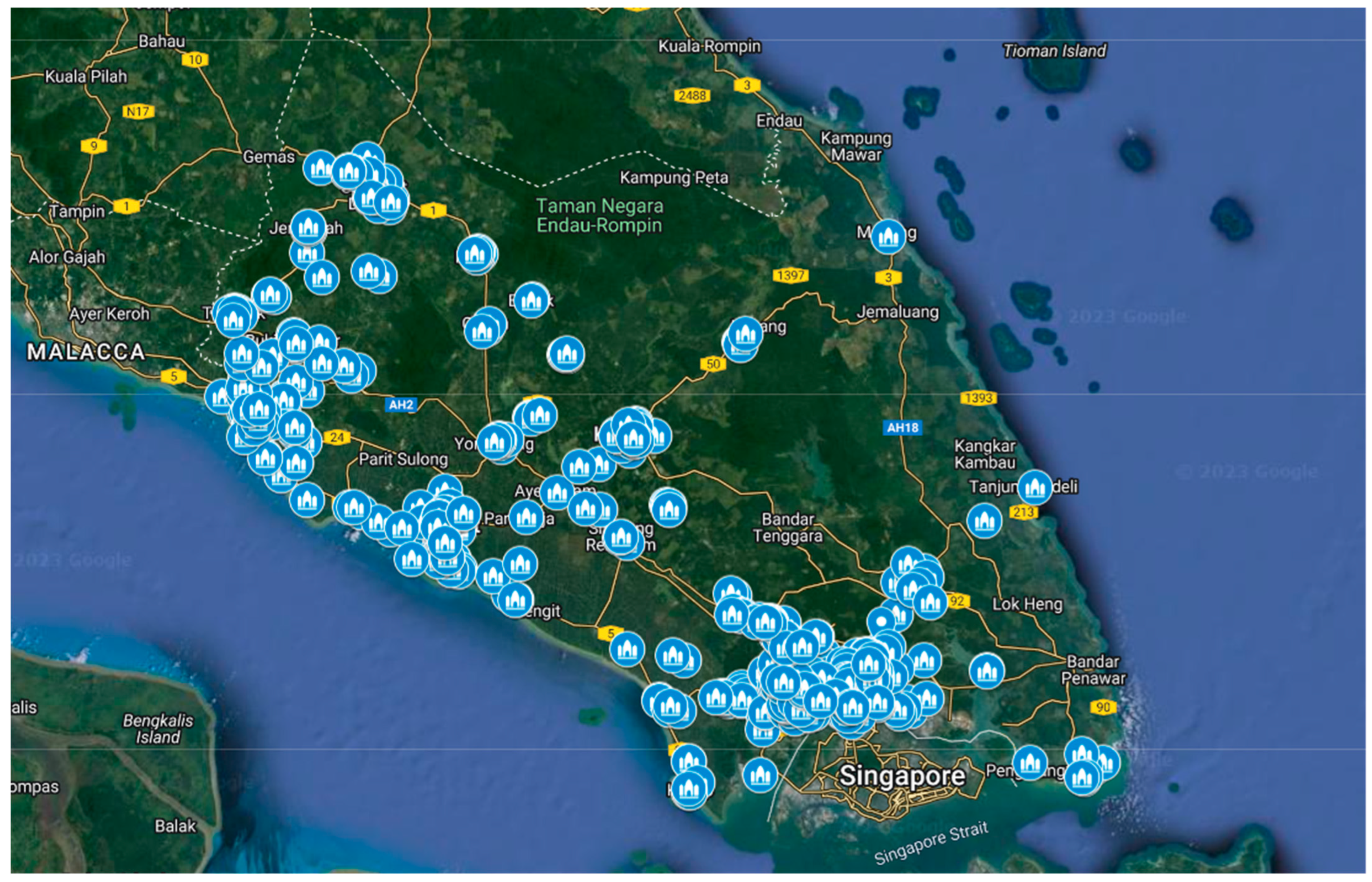

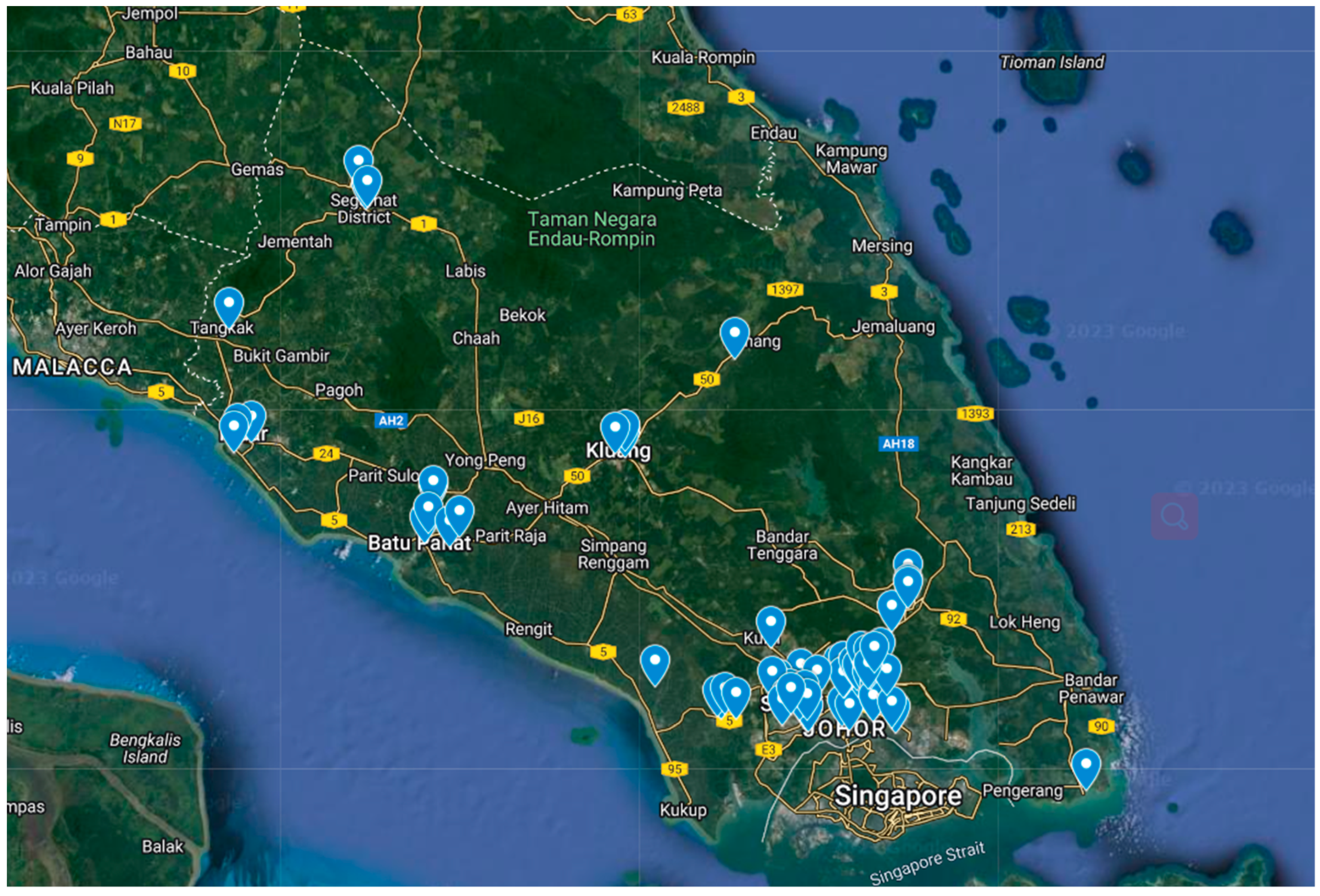

Johor can be roughly divided into four major regions, namely northern Johor, central Johor, southern Johor, and east coast Johor. As can be seen from

Figure 1, a large number of Johor temples are concentrated in the west coast. As shown in

Table 6, Johor Bahru in southern Johor, Batu Pahat in central Johor, and Muar in northern Johor have the most temples, with the sum of the three (597) exceeding 60% of all temples in Johor, far exceeding the number of temples in other districts and cities. From the data presented, it can be deduced that temples in southern, central, and northern Johor are concentrated in these three districts (Johor Bahru, Muar and Batu Pahat) respectively. This is due to their proximity to the coast and the implementation of the Kangchu system, which attracted Chinese immigrants to settle in these areas, resulting in more Chinese and more temples than in the other districts. districts. Due to the limitation of shipping technology at that time, the location of the Kangkar (港脚) was usually beside the river and not far from the coastline, so the Chinese population in these areas was relatively large. According to statistic data, in 1921, the Chinese population statistics of Muar, Johor Bahru, and Batu Pahat were the district with the largest Chinese population. Until 1947 after World War II, although the position of these three had changed, which Johor Bahru have the most Chinese population, but they still occupied the top three positions among the other district (

Natan 1921;

Tufo 1947). Therefore, the number of Chinese temples in these three places is naturally more than in the other district. Of the three main regions, Johor Bahru has the most temples at over 50%, northern and central Johor each account for 25% and 20% respectively, while east coast Johor has the fewest at only 5%.

4 Kota Tinggi was the third lowest with only 52 temples, or 5.51%. The temples are concentrated along the coast or rivers, which is evidence that the early development of Johor was inextricably linked to rivers and the Kangchu system.

5 The Chinese population in the east coast of Johor is small, and so the number of temples is much smaller.

6 This shows that the number of temples is closely related to the size of the local Chinese community.

3.2. Data on The Year of Establishment of Johor Temples

Regarding the year of establishment of the temples, the research team found that only 215 out of 943, or 22.8% of the temples in Johor could show the exact year of establishment, while the remaining 728 or 77.2% could not give a definite answer. This is because beliefs came before temples; when the Chinese migrated south, they brought with their idols from their homeland for worship and spiritual support (

Lew 2014). However, the first immigrants lacked funds to build temples, and hence enshrined the idols in their homes or in simple wooden sheds, and only built temples later when they had the means.

7 The temples are supposed to date from the time the beliefs spread and the deity was first worshipped, but the history of most temples was passed down by word of mouth with few written records of their creation. With the passage of time, the early pioneers are no longer with us, leaving the current temple leaders unable to pinpoint the exact year of their establishment. Moreover, many temples have changed over time, relocating, wars, falling into disrepair, or merging with other temples. In the process, valuable records were lost. Without written records of a temple’s origin, it will no longer be possible to trace its history as it is gradually forgotten by later generations. This highlights the urgent need to record these fading inscriptions.

Due to the lack of records and artifacts, the research team could not establish the date of origin of nearly 80% of Johor temples. Nonetheless, with reliable data on 215 temple’s dates of establishment, the research team was able to trace the development of temple activity in the area.

Table 7 shows that the number of Chinese temples in Johor grew sharply in the 21st century. Few temples were built in the 19th century, accounting for less than 10% of the current total. However, the creation of local temples is a growing trend. Temple construction peaked during the 1950–1999 period, accounting for 47.58% of the current total. In the 21st century, the trend continued unabated, with 52 new temples built in the first twenty years, accounting for a quarter of the total. An average of 2.6 temples were constructed each year from 2000–2020, much higher than the annual average of 1.98 from 1950–1999.

Although the above figures represent only a small portion of the total, they track the growth of the Chinese community in Johor. The temples mark the presence of an immigrant community that brought their gods and beliefs with them.

Table 7 shows that before 1850, there were few Chinese temples in Johor; however, between 1850 and 1899, many temples sprang up. This was the period of development of Johor’s Kangchu system, but due to the inconvenience of transportation, the development of Johor was mainly located near the rivers, leaving a large amount of land in Johor’s hinterland undeveloped. Later in the 20th century, with the maturity of the Kangchu system and the establishment of the Federated Malaysian States Railways after the 1890s, a large area of land in the hinterland of Johor was developed by land transportation, which broke through the problem of the Kangchu system being limited by rivers and made the number of developable areas increase dramatically. According to calculations, more than half of Johor’s territory had the potential for agricultural development due to the land and agricultural areas near the original rivers that became potential areas in the early days of the land transportation linking the major towns in the 1920s

8 (

Pek 2015, p. 70). These new areas of development potential were coupled with the rapid development of the rubber industry in the hinterland in the mid-20th century, and Johor entered the era of the decline of the Kangchu system and the rise of rubber plantation (

Onn and Wu 2009, p. 110). After the rubber industry was established, the Chinese population in Johor increased from 35.1% in 1911 to 42.96% in 1931 (

Yu 1951, pp. 58–59). The rise of the rubber industry led to the arrival of a large number of Chinese immigrants and the explosive growth of the Chinese population.

This growing trend peaked in the 1950–1999 time period with the number of newly established temples appearing in each district. This was due to the fact that Malaya became independent in 1957, and the political stability and economic growth which followed translated into wealth to build new temples.

9 Although the proportion of Chinese in Johor has steadily declined since independence, as in the country as a whole, it is still growing in absolute numbers (

Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal 2022). In addition, the Malaysian government is open and pluralistic and does not restrict temple development. These factors have contributed to the increasing number of temples in Johor since. From

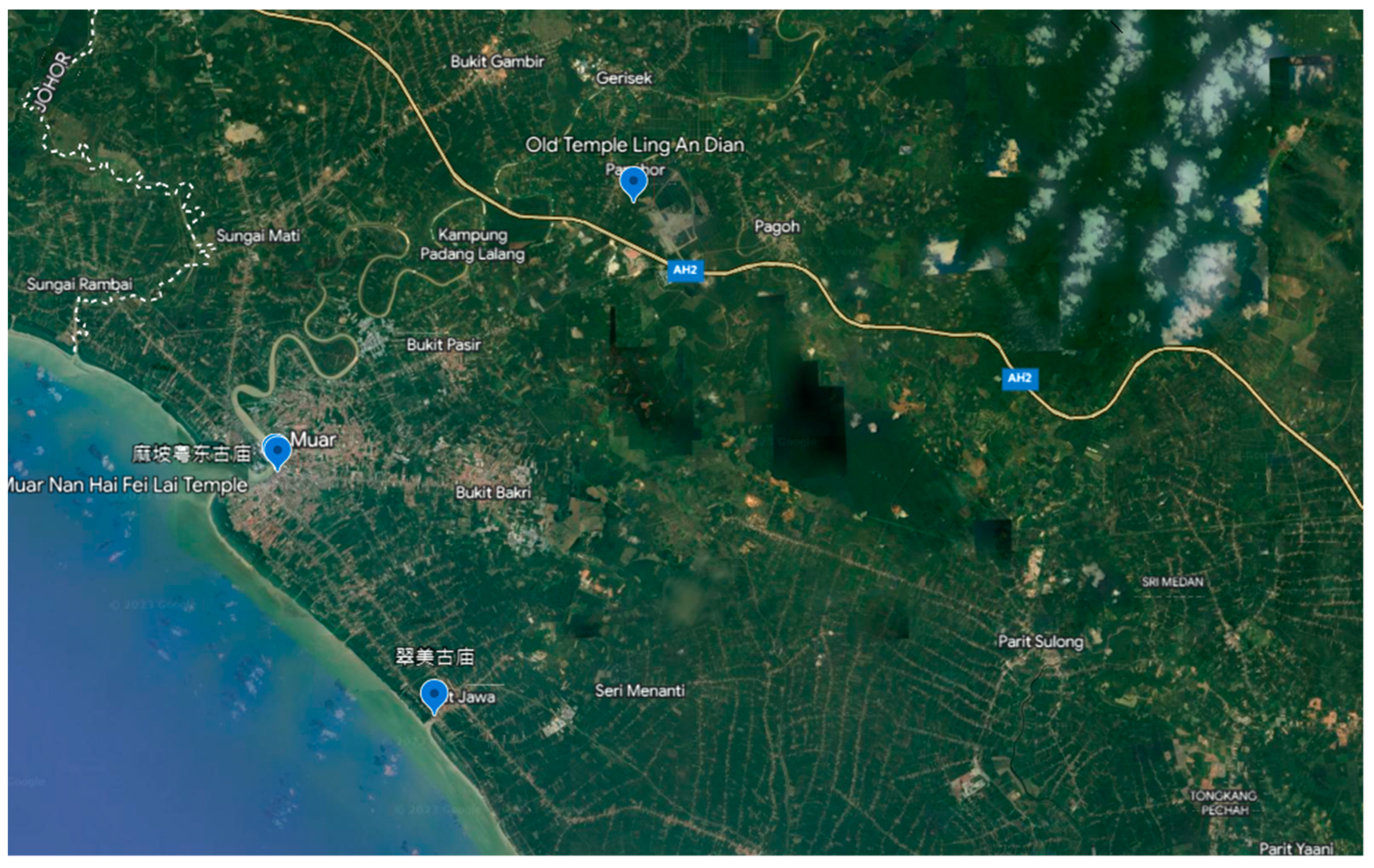

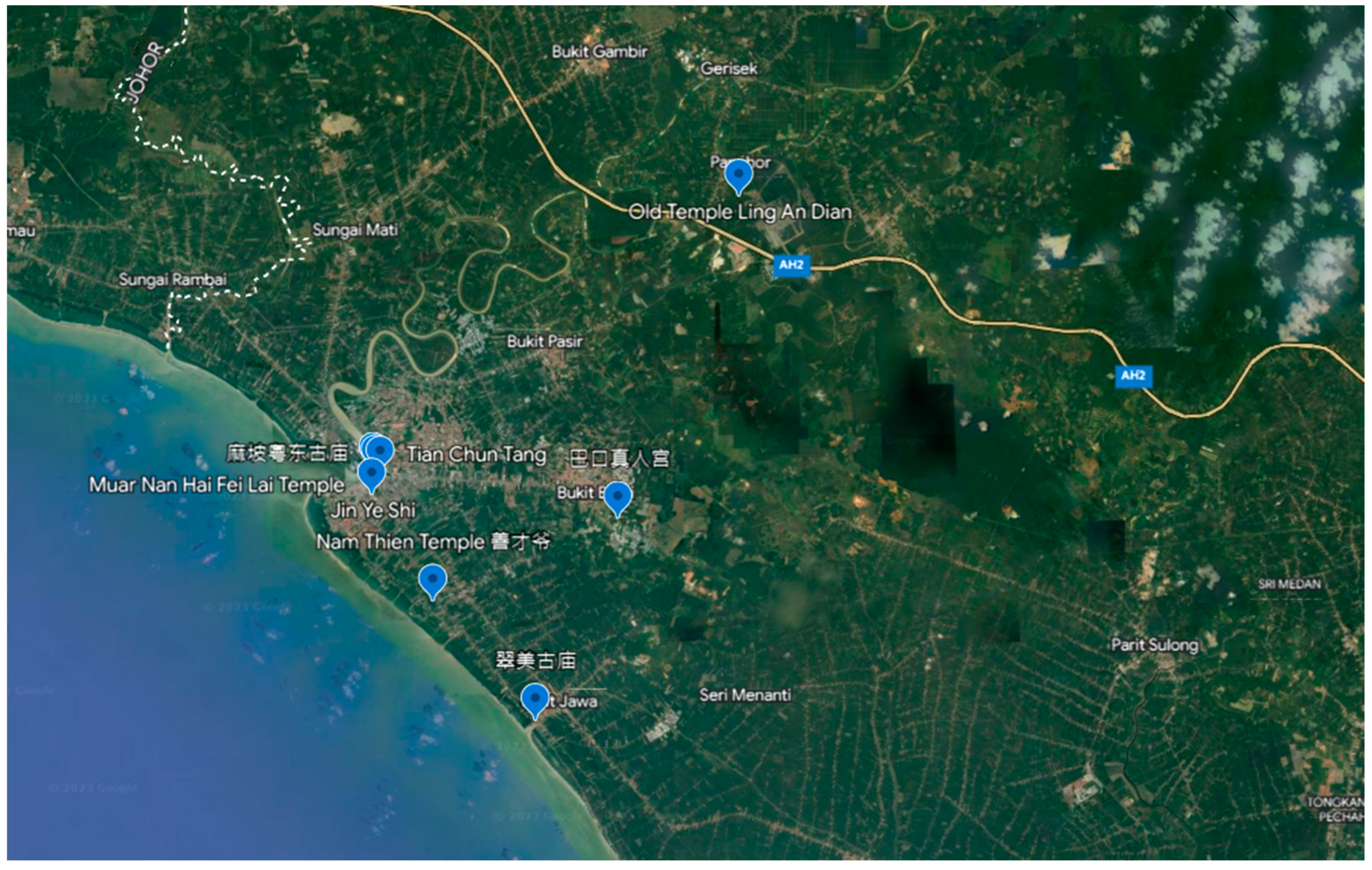

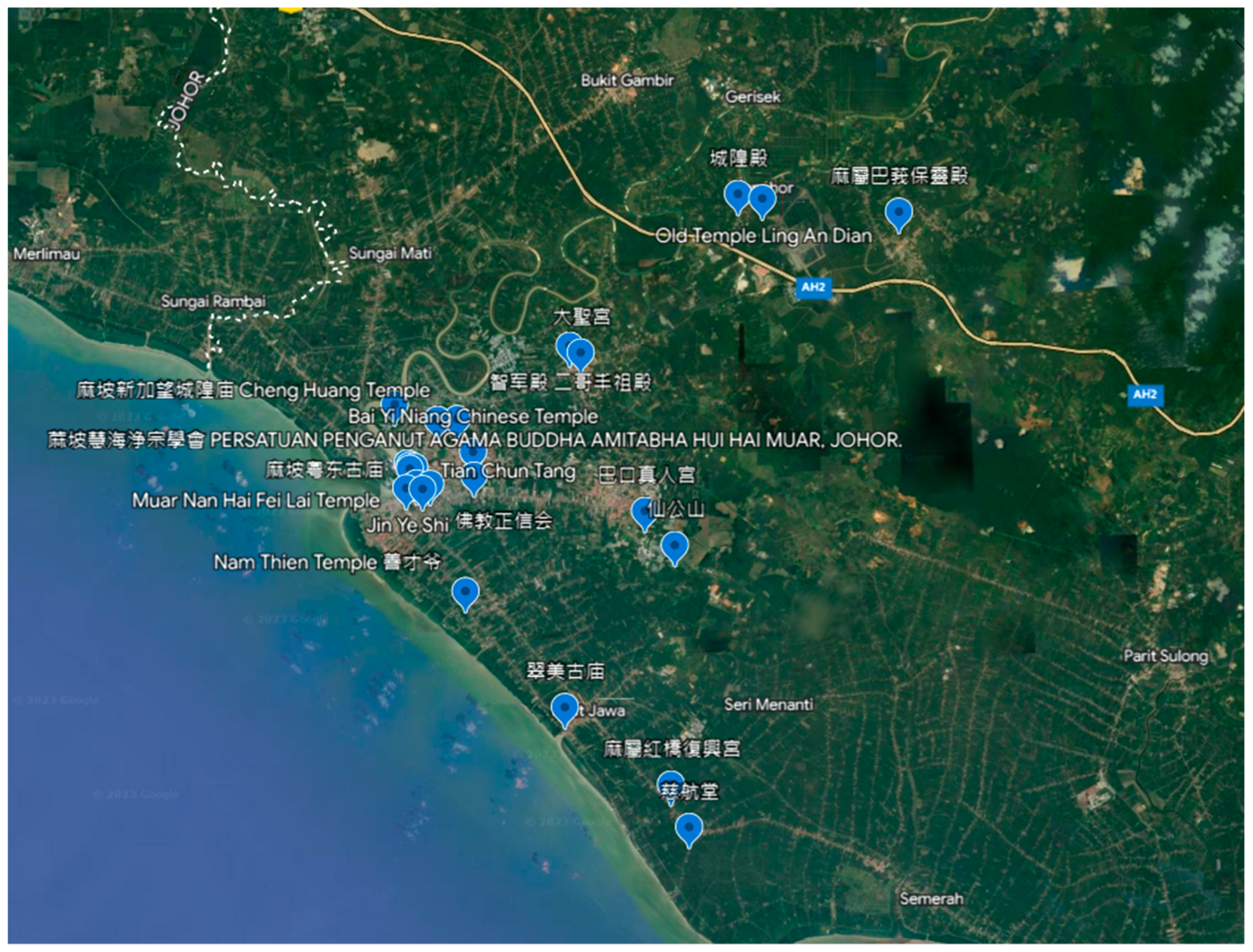

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, the map clearly shows that the number of temple in Muar is increasing.

Table 7 and

Table 8 show that even in the 21st century, the demand for temples has continued to grow. The number of new temples built in this 20-year period alone (52) exceeds the total number built between 1900 and 1949 (40).

According to

Table 8, most of the Chinese temples established in the new century are concentrated in the Johor Bahru area. The Johor Chinese were the first to build temples in Johor Bahru, including the Ling San Temple founded in 1844, and the Johor Ancient Temple, which is considered an icon of Chinese culture in Johor (

Ang 2014). At the same time, Johor Bahru, as the state capital, is developing faster than other districts. It is also a key development area for the government because of its proximity to Singapore. The Iskandar Development Region is the most vibrant area in Johor, with major projects such as Forest City (

Oriental Daily News 2022). As a result, the Chinese here have more wealth to build temples and faith is growing faster than in other districts.

It is worth noting that temples founded in the 21st century are mostly Daoist, which is considered more occult than orthodox Buddhist temples. For example, Nan Sheng Gong (南圣宫) (2002), Xin Ying Tang (金英堂) (2002) and Siang Hock Kong (善福宫) (2019) in Johor Bahru are dedicated to Daoist deities such as the Da Ye Bo (大爷伯), Jin Ying Zu Shi (金英祖师)and Da Er Ye Bo (大二爷伯) respectively. Some temples such as Xin Ying Tang, even have mediums, allowing Jin Ying Zu Shi to possess them and communicate with followers. Data shows that only 10 or 19.23% of the 52 temples established in the 21st century are dedicated to Buddhist deities such as Sa, Guanyin, or Maitreya Buddha as the main deity while over 80% are dedicated to Daoist deities. This shows that the Daoist faith in Johor, and indeed across Malaysia, is not on the decline as is often believed. On the contrary, more are springing up. More data on this will be presented in the next session on the main deities of Johor temples.

3.3. The Main Deities Worshipped in Johor Temples

In terms of the main deity, 758 or 80.38% out of the 943 Chinese temples in Johor were clearly identified after the first visit to the temple. For the other 185 temples or 19.62%, the information was not comprehensive enough to accurately determine the main deity and the secondary deity. Most of the Chinese temples in Malaysia are dedicated to a variety of deities under the Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism deity systems.

10 Generally, Chinese temples are dedicated to one deity as their main deity, representing the highest and most important deity in the temple, followed by other secondary deities. However, the research team found through fieldwork that some Chinese temples have the possibility of worshipping two or more main deities; some temples also worship many deities in a common arrangement, and some temples have the possibility of changing or even disputing the main deity of the temple. Therefore, in the preliminary field survey, a significant percentage of Chinese temples in Johor could not be directly identified with their main deities at first sight.

Of the 758 temples where the main deities could be identified, the researchers found that there were temples dedicated to two or more main deities. For example, the Panchor Ling An Dian (班卒靈安殿) in Muar is dedicated to both Lao Bo Ye Gong (老伯爷公) and Lords of the Three Mountains (三山国王), with both acting as main deities, while the Xuan Tian Gong (玄天宫) in Pontian is dedicated to Da Er Ye Bo (大二爷伯), Xuan Tian Shang Di (玄天上帝) and Wen Wu Cai Shen (文武财神), with all three acting as main deities. Both temples worship have more than one main deity. However, temples with multiple main deities are the exception. As shown in

Table 9, as many as 751, or 99.1% of Johor temples have only one main deity, 4, or 0.5% have two main deities, and 3 or 0.4% have multiple main deities.

Of all the temples where the main deities can be identified, 132 deities can be counted as being worshipped by the Johor Chinese community as the main deities of their temples. Among these deities, Guanyin and Gautama Buddha from Buddhism, as well as Tua Pek Kong and Guan Di from Taoism, are the most prominent main deities.

Table 10 shows that more than 5% of the temples are dedicated to each of these four deities as the main deity. If these temples are summed up, there are as many as 288, or 37.45%, which is the largest category. Thirteen other deities, such as Mazu, the Lord of Fazhu (法主公) and the Xuan Tian Shang Di, were then worshipped as the main deity in 1–4.9% of temples each. The total of these temples was 254 or 33.03%, which was the second largest category. Finally, up to 115 deities received only 1–2 or less than 1% of the temples for each category, and the combined total of these temples was 227 or 29.52%, falling into the last category.

The above statistics clearly speak to the diversity and complexity of the religious needs of the Chinese in Malaysia. Of the more than 700 Johorian temples where the main deity can be identified, 132 deities are worshipped, with an average of only six temples being dedicated to the same main deity. This is a significant difference between Christianity and Islam, which believe in God or Allah as the only god. However, just because there are many gods and goddesses serving as the main deity of a temple does not mean that they all occupy an important place in the Chinese faith.

Table 10 shows that as many as 70% of the temples are dedicated to one of 17 deities, with Tua Pek Kong, Guanyin, Guandi and Gautama Buddha serving as the main deities in the largest number of temples. Less than 30% of the temples are dedicated to gods from the other 115 deities. This shows that although Chinese traditional religion is polytheist, some of the more popular deities, such as Guanyin and Guandi, are more likely to secure emotional recognition, although there are temples with lesser-known deities serving as the main deity. The latter are not small in number, indicating the co-existence of major and minor deities.

Although the 132 deities can be identified as either Buddhist or Daoist, the majority of Buddhist temples are dedicated to Daoist deities (574 or 74.64%) while three temples serve Indian deities or Christ.

Table 11 shows that the Taoists have the largest number of deities with 112 compared to only 18 for the Buddhists. This suggests that although most Chinese Malaysians call themselves Buddhists

11, the Johor temples show that their faith is really more Daoist than orthodox Buddhist in nature.

Moreover, the temples cannot be categorised as Buddhist or Daoist simply from the main deity they worship. This is because the traditional belief of the Chinese in Malaysia is a syncretism of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism (

Tang 2015, p. 36). Some temples dedicated to Buddhist deities such as Guanyin may also serve Daoist deities such as Guandi, Nezha San Tai Zi (哪吒三太子) and Mazu as secondary deities. Some temples dedicated to Buddhist or Daoist deities, also incorporate elements of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism such as the Dejiao (德教), the Zhen Kong Jiao (真空教), and the Shan Tang (善堂) which are Chinese folk religious groups (

Tan 2020, pp. 96–110). Therefore, due to porous boundaries between Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist faith, the temples defy identification, and it is probably best to regard them as sanctuaries of Chinese folk religion (

Wee 1975;

Yuan 2017).

Moreover, by looking at the spatial distribution of the deities, we get a clearer picture of beliefs in Johor.

Table 12,

Table 13 and

Table 14 show the distribution of the 20 best-known deities. Despite regional differences, the deities worshipped do not vary much. Tua Pek Kong, Guanyin, Guandi and Gautama Buddha have huge followings and are the most popular in Johor as well as the whole country.

In seven Johor districts, Tua Pek Kong has the most temples, namely, 90 temples or 11.7% of the total. Tua Pek Kong is sometimes called Dato’ Kong (拿督公) or Fu De Zheng Shen (福德正神), and although there are differences between the three, the lines are blurred. The only thing that remains the same is that these deities are localised and worshipped as guardians of the community or people in business as a god of wealth (

Chiou 1995, p. 361;

Soo 2021, p. 13). Therefore, each community is likely to have a slightly different Tua Pek Kong or Dato’ Kong to bless the local residents to have a safe journey in and out or to bless the worshippers to get rich and prosperous. The multiple functions and meanings of the beliefs of the Tua Pek Kong are also the reason why they are more common in the Chinese community in Malaysia.

As for Buddhist deities, Gautama Buddha and Guanyin are the most prominent, with 80 temples dedicated to Gautama Buddha or 10.4% of all temples, placing him second only to Tua Pek Kong. However, in terms of geographical distribution, Gautama Buddha is less popular and widespread than Tua Pek Kong or even Guanyin.

Table 12 and

Figure 6 shows that most of the temples dedicated to Gautama Buddha are concentrated in Johor Bahru, accounting for 51 out of 80, or 63.75 percent. In other districts, he is the second most popular only in Kota Tinggi, and in some districts such as Batu Pahat and Tangkak is not as common as Guandi, Guanyin, and Mazu. On the other hand, Guanyin is the second most worshipped in six districts, and the first in Segamat, although she is not as popular as Gautama Buddha in terms of numbers. Therefore, it can be inferred that Guanyin is the most popular in Johor after Tua Pek Kong.

The difference between Guanyin and Gautama Buddha, both Buddhist deities, is due to the fact that many Chinese temples with a Daoist flavour worship Guanyin as the main deity. For example, the Jin Yin Dong Tian (金液洞天仙公宮) in Tangkak and the Wu Ji Sheng Mu Sheng Dian (无极圣母圣殿) in Segamat both worship Guanyin as the main deity, but they also worship Daoist deities such as Nezha and the Jade Emperor as secondary deities. These Daoist flavored temples are less likely to worship Gautama Buddha as the main deity; he is worshipped as the main deity in orthodox Buddhist temples or associations. Johor Bahru, as the capital of Johor, is the economic and cultural center of the southern part of the Malay Peninsula. Hence, some of the larger and more organized orthodox Buddhist associations have chosen to establish themselves there. Some of the more notable ones include the Johor State Branch of the Malaysian Buddhist Association, the Fo Guang Shan Johor Bahru Buddhist Centre, the Johor Jaya Kadhampa Buddhist Association, the JB Manjusri Buddha Association, and the Skudai Taman Universiti Buddha Association, to name but a few. In Johor, folk religion is still dominant, which explains why Gautama Buddha is less popular than Guanyin and can only be found more in Johor Bahru.

Finally, the data allows us to trace of the origin of a deity through its dialect. With the exception of the Tua Pek Kong, who is a local deity, most of the deities can be traced back to China. Of the 132 deities, 26 came with Hokkien immigrants, including Nezha, Lord of Fazhu, and Hong Xian Da Di (洪仙大帝), while the Hainanese and Teochew people brought five each, followed by two Cantonese deities and one each of the Hakka and Hokchiu people. The deities’ background shows that they originate from southern China, matching the dialects in Malaysia. The Hokkiens have always been the majority, and their pantheon is more diverse and complex, thus giving their deities a numerical advantage.

12 However, most temples have since crossed dialect lines, making it difficult for the data to reflect the beliefs of each dialect group (

Li 2018, pp. 333–35).

Apart from dialect-specific deities, the others are universal deities, such as Guanyin, Mazu, Guandi, and the Jade Emperor, which are worshipped by all dialect groups from the time of their arrival. Of the 17 most popular ones in Johor, 10 became universal, making them more common. Of course, there are some obscure deities, whose origins are unclear such as the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors (三皇五帝), Shi Yuan Lu Xian Chang (士元卢仙长), the Wan Tian Zhu Shuai (万天主帅), and the Yan Shi Tong Tian Emperor (严氏通天皇). Pending further investigation, the attributes of these deities are classified as ‘unknown’.

4. Discussion

Some characteristics of Chinese faith in Johor can be summarized from the research results of the previous sections, such as the higher concentration of Chinese temples in Johor Bahru, the continuous establishment of new temples, and the dominance of Chinese folk beliefs in the Chinese religion in Johor. Combined with the above findings, the overall development of the Chinese faith in Johor shows at least two trends. Firstly, the number of new temples established by the Chinese in Johor is on a steady increase, and the number of Chinese temples will become even larger in the future, moving towards greater diversity and plurality. During the two hundred years of history, some temples have been eliminated and have not survived. However, according to our team’s analysis and understanding of the situation of Chinese temples in Johor, the number of Chinese temples in Johor is increasing rather than decreasing, and the local Chinese faith is blossoming.

Dr Hue Guan Thye visited the Chinese temples in Johor during the most severe period of the epidemic, but during this period there were still many temples that withstood the difficulties and continued to operate, which is why nearly 900 temples were excavated. There were also new temples and organisations established during this period, such as Sheng Fu Gong (圣福宫) which was established in 2020, and the Simpang Renggam De Jiao Che Lu Khor (新邦令金德教会紫濡阁) which was established at the year 2022. Dr Hue also visited eight temples in Johor studied by Franke and Chen in the 1980s and had their inscriptions photographed, collated, and stored in the digital humanities system, reflecting that the fact that these temples are still standing in Johor after 40 years. Combined with the above trend of new temples coming up, the demand for new temples has continued despite the closures of some temples due to poor management, and even in the 21st century, the data shows that the momentum has not slowed down. It can be deduced that the number of temples in Johor is on the increase and will not change in the near future. The data shows that after years of modernization, traditional temples are still thriving, unbroken by the tide of time and showing unprecedented vitality.

Secondly, since the 19th century, nothing big has changed in Chinese religion in Johor; it remains dominated by folk beliefs, and most of the temples or religious organisations practice a mix of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism. In the early days, Chinese temples were called “Miao” (庙), “Palace” (宫), “Dian” (殿) and “Kwan” (观). From the mid to late 20th century onwards, orthodox Buddhism became active in the Malaysian Chinese community. In the late 1940s, Buddhists began to unite to fight for the rights to Buddhism, such as the fight for Wesak Day as a national holiday and the establishment of the Malaysian Buddhist Association (

Tang 2004;

Bai 2008;

Wu 1993). In response to the need for religious teachers, Buddhists at the time initiated the establishment of Buddhist colleges. From 1959, when it was proposed by the Minister of Buddhism, to 1971, it was officially registered, the Institute has been in existence for almost fifty years (

Shi and Ching 2020). From time onwards, various Buddhist organisations such as the Buddhist Association, and the Buddhist Hall were established. However, these associations, although better organised than traditional Chinese temples, formed a minority. Most temples or religious groups established in the 21st century still bear the traditional Chinese nomenclature “Miao”, “Palace” and “Dian”, rather than the Buddhist “Tang” (堂), “Si” (寺), and “Yuan” (院). Moreover, there are many main deities, with most being familiar with Daoist deities such as Nezha, Guandi, Ma Zu, and Tua Pek Kong from traditional Chinese folk religion while temples dedicated to purely Buddhist deities are still in the minority. Although orthodox Buddhism has been actively spreading, it has yet to change the mindset of the majority of Chinese who practise folk beliefs and customs. Besides, the spread of orthodox Buddhism is limited to Johor Bahru, which can be considered a Buddhist stronghold. Buddhism is geographically limited and not as widespread as folk beliefs.

Johor Bahru occupies an important place in the state of Johor. From the 19th century onwards, the city boasts the most temples in the state and dominated the local Chinese faith. Because of the large number of temples in the city, the deities worshipped here to make up the biggest group in the pantheon. Gautama Buddha is the principal deity in Johor Bahru and although he is less popular elsewhere than in Guanyin and Guandi, the number of temples in Johor Bahru makes Gautama Buddha the second most popular principal deity in the state after Tua Pek Kong. Conversely, the most popular main deity in Kulai is the Monkey God (齐天大圣), with 4 temples which account for 9.31% of the city. However, as the number of Kulai temples represents only 5.37% of all Johor, Monkey God only accounts for 2.47% (19 temples) of principal deities in the state.

Judging from the current trend, Johor Bahru will continue to influence the development of the Chinese faith in Johor. New temples built in the 21st century are still concentrated in Johor Bahru, i.e., 30 temples or 57.69% of the total of 52 temples. In contrast, Batu Pahat, which has the second highest number of temples, is more evenly divided in terms of main deities. Its eight temples were built since the turn of the 21st century, which cannot match with Johor Bahru. Based on current statistics, Johor Bahru will continue to play an important role in the future in terms of Chinese religion in Johor, and as the regional centre of the temple network. The orthodox Buddhist faith, with Johor Bahru as its home base, will gain a foothold in the state and even see a gradual increase in numbers. This is due to the economic development of Johor Bahru. From ancient times the development of temples has often been linked to the economic development of the area. Since independence, Johor’s economic development favoured the south over the north (

Oriental Daily News 2012). The development of commerce can often be seen in the number of commercial guilds. Johor Bahru, the capital of Johor, saw a proliferation of business associations in the post-war period. According to the statistics, a total of 61 chambers of commerce were formed after the establishment of Malaysia in 1963, and after the completion of the Senai Airport and the port of Pasir Gudang in 1974, a surprising number of 39 new chambers of commerce were formed until 2003, when there were 79 units (

Wu 2003, p. 67). The booming economy in turn led to growth in population and income which made it easier to raise funds for temples.

13 It is easy to see why more temples are being built in Johor Bahru.

Table 15 shows that, of the seven Buddhist temples or associations dedicated to Gautama Buddha as the main deity found in the 21st century, four are in Johor Bahru. There are two temples where Guanyin is the main deity in Johor Bahru but these belong to Buddhist groups, not temples of folk belief.

14 Both temples are purely Buddhist without Daoist or Chinese folk beliefs. Johor Bahru is clearly the centre of Buddhism in Johor, a trend that is likely to continue. However, this only means that Buddhist associations will grow in Johor Bahru, not that they will overtake other Chinese folk religions as the mainstream of Chinese belief. Even in Johor Bahru, which has the highest percentage of Buddhist temples (30%), the remaining 70% are Daoist or Confucianist-Buddhist-Daoist fusion temples and religious associations. Even in the 21st century, two-thirds of new temples are Daoist rather than Buddhist.

The above findings about Chinese beliefs in Johor echo those of previous researchers. There is an early consensus among Malaysian and Singapore scholars that although the local Chinese call themselves “Buddhists”, the meaning of Buddhism is more accurately a combination of Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, and Chinese folk beliefs (

Lai and Wong 1998;

Tang 2004,

2015;

Tan 2009;

Wee 1975;

Yuan 2017). Government statistics show only five religious categories, namely, Muslim, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, and Others (

Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal 2022).

15 This figure is at odds with the data obtained in this study; although both the believers and the government use the label “Buddhists”, their beliefs should be better described as folk beliefs. It follows that the Chinese themselves do not feel the need or sense to define themselves as Buddhists or as believers in “Chinese Religion” (

Tan 2020, pp. 139–40). They are more tolerant and accepting of religious pluralism. As for Johor, Johor Bahru’s status as the centre of Chinese belief in the state is not a surprise. The more significant finding, however, is that the most popular deity in Johor is not those from China, but the indigenized Tua Pek Kong. Some of the Tua Pek Kong are Malay Dato’ Gongs, while others are local Chinese sages or Fu De Zheng Shen from China. Tua Pek Kong is a blend of indigenous elements, and serves as a protector of the community, blessing the locals with safe travel and good weather. The other important deities in Johor are Gautama Buddha, Guanyin, Mazu, and Guandi. Only a few dialect-specific deities, such as the Hokkien Lord of Fazhu and Hong Xian Da Di occupy a certain number of temples as main deities. Even so, they are less widely received as pan-Chinese gods, suggesting that gods who transcend dialect lines are more durable as segregation along dialects weakens.

Furthermore, data shows that the traditional Chinese temple culture is not in decline. Even in the 21st century, the Chinese in Johor are still building temples, most of which are of Chinese folk belief, as seen in Johor Bahru. Among the temples in Johor, this study found that between the Daoist and Buddhist temples, there are religious groups that do not belong to either, but which mix Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism. In Johor state, there are seven Zhen Kong Jiao temples, nine Shan Tang, and sixteen De Jiao associations. These are new groups originating in China in the 20th century, which distinguish themselves from Daoism and Buddhism, but worship Buddhist and Daoist gods and teach people to do good (

Xianggang Dejiao Zijingge Congshu Liutongchu 2012). Their beliefs are a blend of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism and can only be regarded as Chinese folk religion.

Most of these groups spread in the 1950s after Malaya’s independence, and Johor was a key foothold. The first large-scale temples of Zhen Kong Jiao in South Malaysia and Singapore were built in Johor Kluang, namely Zhen Kong Dao Tang (真空道堂), and the faith has since spread to other parts of the region. The Muar-based Bao De Shan Tang (报德善堂) is a branch of the Singapore Bao De Shan Tang. These temples are connected to the Chinese network in Malaysia and Singapore. As for the De Jiao Hui, it is found in all parts of Johor, with associations in eight districts and cities, seven of which are located in Johor Baru. Of the 16 Johorian De Jiao Hui, nine can be dated (date of establishment), and six were founded in the 21st century. The Kluang Simpang Renggam Dejiao Che Lu Khor founded in 2022 is evidence of the group’s spread. The emergence of groups such as the Zhen Kong, the Shan Tang and the De Jiao Hui shows that faith in Johor is more complex than one might think. The beliefs and temples are neither Buddhist nor Daoist, but a mixture of Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism and that is grounded in Chinese culture.

5. Conclusions

This study of Chinese temples in Johor is the first attempt to build a Malaysian historical GIS. Through the study of more than 900 temples, the research team surpassed in number of previous studies in the state, and used the data to map the development and status of local Chinese faith networks. The study not only confirms the syncretic nature of Chinese religion fusing Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism, but also disproves the common assumption that temple culture is on the decline. In fact, the number of new temples is on the rise, with the majority dedicated to Daoist deities. Daoist temples dominate the religious landscape, but there are also orthodox Buddhists and temples which are not strictly Daoist or Buddhist, such as the Dejiao, the Zhen Kong Jiao and the Shan Tang. The situation of Chinese temples and beliefs in Johor is a microcosm of the Chinese community in Malaysia, and its inherent religious and belief characteristics can be reflected nationwide.

This study not only analyses data on Chinese temples in Johor, but uses Historical Geographic Information System (HGIS) to provide a new understanding and method of Chinese temples and beliefs through the study of underlying communities. When the historical data of the temples is successfully input into the digital humanities system through field research and transformed into statistical data, the HGIS will be able to show the spread of beliefs, community networks, and their development. Future scholars will be able to use the system to study temples from a more macro perspective, further enriching research in related areas and deepening the understanding of religious life in the state.

Due to the large number of temples covered in this study, gaps in data are unavoidable such as the year of establishment of the temple and the principal deity worshipped. Given time limitation, the data presented and discussed here gives only a general outline, and are by no means 100% accurate. Historical anthropological fieldwork is not quick and easy, but requires repeat site visits to check for errors and conduct further surveys to ensure rigour and accuracy.