Abstract

The grounds of religious diversity and pluralism have mainly been sought out from without, i.e., from outside the human mind. A striking example is Hick’s idea of the one ultimate reality, which is posited to embrace all the semi-ultimate realities appearing in individual religions. However, the present inquiry adopts a different strategy for coping with the above-mentioned issue. Specifically, in this inquiry, I attempt to find a substantial clue to religious diversity and pluralism from within, i.e., from the intentionality of the mind. This idea, as a descriptive and explanatory hypothesis, consists of the following theses: (I) As suggested by the Husserlian phenomenology interpreted by Sokolowski, there are at least two forms of directedness of the mind: filled and empty intentionalities. (II) In connection with them, two distinct types of religious spirituality emerge: the intentionality of transcendental filling (ITF) and that of transcendental emptying (ITE). (III) The diversity of religion that gives rise to pluralism is, at least in part, due to the different ways in which those two forms of religious minds are combined. With these considerations, we reach a new philosophical foundation of the issue in question, and also obtain a possible theoretical basis for securing an adequate method of religious—and particularly interreligious—studies.

1. Introduction

Viewed from the global perspective in the 21st century, it appears to be a truism that there are many different religions, although we do not completely agree with the definition of the term “religion.” This diversity of religion seems to support religious pluralism. The latter, in order to be suitably maintained, has to presuppose the former, but not the other way around. However, things are not that simple. We note that, from the perspective of the contemporary philosophy of religion or theology of religion, religious pluralism is considered to be a particular normative stance on how one—as far as he or she has a religious worldview, including atheism or, even, anti-religionism—should see and treat other faiths. Regarding this issue, we already know that there are, in addition to pluralism, other salient positions, such as exclusivism and inclusivism. Roughly speaking, if we adopt pluralism, we ought to acknowledge other religions, i.e., the existence, meaning, and even truth of other faiths. If we maintain inclusivism, we ought to accept the validity of other faiths at least partially and try to include them in our own faith; if we espouse exclusivism, we ought not to admit other religions and should rather stick to the absoluteness of our own faith. In this regard, there seems to be a notional, ideological difference between religious diversity and pluralism. Notice that both inclusivism and exclusivism do not deny the existence of other religious belief systems and, thus, the diversity of religion itself. What they reject is the meaning and/or truth of such religions. This point reveals that it is not clear whether the diversity of religion actually upholds religious pluralism. However, is that really so? My answer will be “no.” There is, certainly, a gap between religious diversity and pluralism, but this does not mean that they are significantly distinct. In that respect, to bridge the gap between the two is to uncover the very close connection between them. It is also to secure the grounds of religious diversity that give rise to religious pluralism. Looked at this way, if a proper philosophical treatment is given to the diversity of religion, it will be able to reinforce religious pluralism.

Regarding the philosophical treatment mentioned above, we observe that there has been a serious philosophical attempt. As is well known, it is John Hick who has, in light of Kantian philosophy, conducted the demanding task in various ways.1 As this is not the place to scrutinize Hick’s philosophy of religion, we, for the sake of argument, briefly sketch the Hickean position on the above issue as follows: (i) There are, in fact, many different religions; (ii) We can, at least hypothetically, postulate the one ultimate reality called “the Real”, which is supposed to embrace all the supreme truths and realities appearing in particular faiths; (iii) As far as all the individual religious traditions are paths towards the one ultimate reality, and each of those paths helps us to shift from a self-centered worldview to a reality-centered one, we ought to acknowledge the existence, meaning, and even some truth of those faiths.2

Hickean theory is philosophically impressive and religiously thrilling, particularly when we approve of the idea of the Real. However, what if we do not accept the notion? In that case, does the justification of religious diversity and pluralism collapse? I do not think so. In order to see what this answer means, we pinpoint the crucial feature of the Hickean approach in this way: namely, it is to seek out the foundations of religious diversity and pluralism from without, i.e., in terms of super-transcendent reality. That would be, after all, the source of the merits and demerits of the Hickean approach. Now, I wish to suggest that this is not the only strategy for wrestling with the issue. Hence, I advance the proposal that we can find the grounds of religious diversity and pluralism from within, i.e., from the intentionality of the conscious mind.

To elaborate on this view, I choose and discuss some ideas about the intentionality of the mind presented in contemporary phenomenology and the philosophy of mind. In that procedure, my theoretical choice is unavoidably selective and limited. However, the decisive criterion for selecting an idea for the present inquiry is whether and how the idea can directly help to construct a theory of the intentionality of the religious mind that can vindicate the connection between religious diversity and pluralism; the selected idea should be clear, explanatory, and neutral in dealing with the varieties of religious phenomena. Thus, if an idea is not markedly construed as sustaining our issue, we cannot adopt the idea, even if it is philosophically or religiously momentous. From this standpoint, I opt for the following: the concept of intentionality as directedness; a content theory about the structure of intentional states; the view that there are different types of directedness, i.e., intentionalities of mind, symbol, and language; Searlean thought of the background of intentional states; Robert Sokolowski’s conceptions of filled and empty intentionalities, based on the Husserlian notion of appresentation; and some crucial interreligious insights into filling and emptying. As we shall see, these ideas constitute the skeletons of the intentionality of the religious mind characterized by transcendental filling and emptying.

On the basis of such ideas, three theses are presented: (I) As suggested by the Husserlian phenomenology interpreted by Sokolowski, there are two distinct types of directedness of the mind: filled and empty intentionalities. (II) In connection with them, two distinct types of religious directedness emerge: the intentionality of transcendental filling (hereafter “ITF”) and that of transcendental emptying (hereafter “ITE”). (III) The diversity of religion that gives rise to religious pluralism is, at least in part, due to the different ways in which those two religious intentionalities are combined and intertwined. Here, the eight aspects of ITF and ITE and their combinations are claimed to be the vital theoretical framework that can properly handle religious diversity and pluralism.

In the following, we begin with an analysis of the intentionality of the mind (Section 2), and proceed to put forward those three theses (Section 3). Special emphasis is placed on the exposition of theses (II) and (III). We will find out how these thoughts freshly resolve the problem of religious diversity and pluralism, and also see their potential theoretical implications.

2. The Ideas of Intentionality

2.1. The Concept of Intentionality

We begin by examining the notion of intentionality. Just as a mind in general can be characterized and defined by intentionality, so can a religious mind. What, then, is intentionality? In a word, it is directedness, aboutness, of-ness, directionality, or semanticity. Intentionality highlights the fact that “all experience is experience of something” (Allen 2005a, p. 184). That the mind has intentionality means that the mind is directed upon, or is about, something, i.e., an object or state of affairs in the world. That something, occasionally called the “intentional object,” may or may not actually exist in the world. Here, an object usually refers to an actual particular entity or, in Aristotle’s term, substance; and a state of affairs designates an actual or possible fact that is typically combined by entity and property. Meanwhile, an object is sometimes taken to be purely schematic, so we sometimes speak about, for example, “the object of thinking”, which indicates what that thinking is about. Thus, when the mind is directed upon an object, the object can be understood narrowly (that is, as a particular thing in the world) or widely (that is, as a variable or place-holder for an actual or possible entity or state of affairs).

Suppose that you are seeing a flower in the fields. Your seeing is an intentional mental act in which your mind is directed at the flower. In addition, suppose that you are imagining Santa Claus. There, your mind is about a non-existent entity called “Santa Claus.” Being able to represent absent or non-existent entities in the world is, even on the empirical level, a vital feature of intentionality. What about loving God? What about thinking of Being or Nothingness? In these cases, items such as a flower, Santa Claus, God, Being, and Nothingness can represent the objects of thinking. Due to intentionality, a subject (or a self) cognizes, and relates to, an object (or the other, i.e., something other than the self).

In the meantime, we should not, particularly when using the English language, confuse the ordinary sense of the term “intentional” with the technical sense of it. The former indicates “having a purpose in mind” or, simply, “purposeful.” This way of understanding the term “intentional” is not illegitimate. Some scholars in religious studies use the word in that way (Swidler 2016, p. 20). By contrast, what we mean by the term, in this paper, signifies “being directed upon an object or state of affairs.” Thus, when we encounter some philosophical parlance, such as “we intend an object,” we need to see and determine its correct meaning. Intention as having a purpose in mind is a particular form of the intentionality or directedness of the mind in general (Searle 1983, p. 3).

To repeat, the intentionality of the mind denotes the property, function, and faculty of the mind in which referring, representing, cognizing, and acting are possible. In this respect, to have a proper theory of intentionality means to understand and explain those activities adequately. In that way, intentionality has an enormous elucidatory and explanatory power. This is why, both in phenomenological and analytical traditions of philosophy, there are lots of opinions, ideas, and doctrines about it. Nonetheless, here we ask, is there any substantial and systematic theory of intentionality that uniquely concern religious mind and spirituality? It is hard to give a definite answer to the question. Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, hints at some possibilities and aspects of religious spirituality, but he does not try to provide a concrete account of the intentionality of religious mind. Max Scheler, facing Husserl’s phenomenology in his own way, furnishes “an essential phenomenology of religion”, in which the essences of the divine, of revelation, and of religious act are greatly pursued (Scheler [1960] 2017, p. 161); however, he does not give us a tangible intentionalistic account of the diversity of religion. John Searle, a robust theorist of intentionality who defends a form of biological naturalism, presents us with a perspicuous view of the intentionality of the mind, a theory far more free from the obscurantism permeated in traditional phenomenology; but he never theorizes about what is going on in the religious mind. It is indeed unfortunate that, in spite of its immense theoretical potentiality, we have not had such a definitive theory of religious spirituality based on the language of intentionality. The notion of intentionality is not problematic, but we still lack a perspicuous, systematic, self-contained theory of intentionality that can cope with the varieties and diversities of religion.

2.2. The Relevance of Intentionality to Religious Mind

2.2.1. The Structure of Intentionality

This is not a place to explicate all of the aspects and characteristics of the intentionality of the mind. Therefore, in the following, I focus on laying out two important facets of intentionality that are directly relevant to our issue. One is about the structure of intentional states, whereas the other is about different sorts of intentionality.

We begin by asking, what components does an intentional mental state consist of? This question has to do with the structure of intentionality. Regarding that issue, there are two models: object theory and content theory (Sajama and Kamppinen 1987, pp. 5–10). The former asserts that the intentionality of the mind has two components, i.e., the subject and the object, whereas the latter contends that it has three components, i.e., the subject, the content, and the object. Object theory highlights the direct cognitive relation between the mind (human) and the world (environment). By contrast, content theory postulates that there is a cognitive intermediary between a subject and an object, which may be called “content.” Such content is regarded to include concepts, thoughts, ideas, or images (Smith 1989, p. 9).

Positing the content of an intentional state is somewhat controversial, because it has some theoretical disadvantages. For example, in that theoretical scheme, the relation between the mind and the world is, either implicitly or explicitly, indirect. This may insinuate that there is something mysterious in the mind, and it may lead us to wonder how content is formed in the mind and whether it is, in fact, intramental or extramental.

Nevertheless, the postulation of intentional content has its own theoretical merits. First, content cognitively connects the subject to the object. Suppose that you are seeing a tree. In this case, the subject of that intentional state is you, the object is the tree, and the content is the concepts or true propositions associated with that tree, e.g., a tall plant that has a hard trunk, branches, and leaves. Without grasping such content, you cannot see a thing as a tree. Note that knowledge about religious symbols and objects depends on possessing the concepts of such symbols and objects. If you do not have any concept of God in your mind, then even if you see a God, you may not see them as a God. Thus, the subject cognizes the object through the content. This is the notion of content as a cognitive mediator. Second, in content theory, the difficulty linked to the puzzle about representing non-existent entities is diminished. This is because, even if there are no non-existent entities in the world, they could be deemed to exist in the mind, not as objects, but as contents. In this case, we will need to say that the mind is directed at the content in the mind. That is not a standard view on the issue, but it could still be a solution.

Perhaps the most important advantage of content theory is that it can handle a crucial aspect of the religious mind. This is the notion of content as a cognitive sediment, resultant, or remnant. In religious contexts, we are often told that, for one to attain the religious goal, one must purify one’s body and mind. In our philosophical parlance, purifying the mind indicates emptying one’s mind of secular intentional content, which is taken as mental sediment or remnant. We cannot eliminate objects and facts in themselves, but we can, likely with the aid of special religious training, such as prayer, contemplation, and meditation, dispose of (at least, “some”) mental content, which is understood to be concepts, ideas, or representations of objects and states of affairs. In this way, intentional mental content is closely related to religious practices. That is why we adopt content theory when it comes to identifying the religious mind.

Let us go one step further now. Intentional states are not isolated; while forming the networks of those states, they function together. Those intentional states, as networks, are ultimately based upon some background (Searle 1983, pp. 141–45).3 The background of intentional states includes “a set of skills, stances, preintentional assumptions and presuppositions, practices, and habits” (Searle 1983, p. 154). It also involves psychological histories and bodily capacities. We can call the background of intentionality “the bedrock of the mind.” Interestingly enough, this line of thought appears in various ways. In psychological science, for example, consider the theory of the unconscious put forth by Sigmund Freud. It states that all conscious activities and behavior are governed by the unconscious. In religious contexts, consider the Mind-Only School of Buddhism or Yogācāra School, which propounds the idea that there is, in the mind, an eighth consciousness (Ālaya-vijñāna), called “storehouse consciousness”, wherein all the informational seeds or contents of conscious activities are somehow saved and constitute one’s karma. The point I wish to make is that the notion of content in the theory of intentionality is, together with that of background, closely connected to the proper understanding and explication of the nature of the religious mind in a profound way. This is why we take content theory seriously.

2.2.2. Kinds of Intentionality: Intentionalities of Mind, Symbol, and Language

In pinning down the essential features of the religious mind, we need to make clear another vital idea, which is that there are several different sorts or types of intentionality. Let us see what this means and what roles it plays in religious contexts. The point is that, aside from the mind, both symbols and languages have intentionality in the sense that they are about, refer to, or represent objects and states of affairs in the world. When it comes to symbols and languages, it is worth noting that there are empty signs and names that are supposed to refer to non-existent entities. Some extreme atheists, reductive materialists, or eliminativists would claim that all religious symbols and expressions are mere empty names that lack real referents. However, what they fail to see is that such symbols and languages help us understand and enter the new levels of reality and of soul (Tillich [1955] 1987, p. 48). We may call this the constitutive function of symbols and languages.4 This does not mean that they literally create those worlds. What it means is that they play the role of the window or entrance to taking new ways of looking at the world. It is very important to see this point clearly, and those ways of seeing the world are, religiously or non-religiously, dependent on using languages (Lindbeck [1984] 2009, pp. 32–37; Kiem 2021, pp. 176–81). Furthermore, some symbols and linguistic expressions indicate core doctrinal statements in individual religions, such as “God creates the world” and “All is suffering.” In this way, although intentionalities of symbols and languages are conventional and derivative, they are fundamental to human life, including religious forms of life. They become the hallmarks of human cultures and civilizations.

The ideas presented above cause us to take a fresh look at the familiar but unnoticed fact: When a human being uses a language, some double or multiple intentionalities are obtained. Suppose that you are seeing a picture of Buddha or Jesus on the wall while uttering the word “Buddha” or “Jesus.” In this case, your mind is, at first, directed upon a picture at the physical level, i.e., a physical shape in the frame, and the linguistic expression being used by you refers to a certain being. While seeing the picture and uttering the word, your mind may finally be directed upon the historical Buddha or Jesus, and ultimately, toward Buddhahood or Godhood itself. Multiple intentionalities of the mind, pictures, and language are, alongside the diversities of meaning and reality, interwoven in this way.

It should be noted that symbols and languages are representations, in the sense that they are conventional proxies that stand in for the real or possible entities and events in the world.5 They are considered a means to an end. Nonetheless, in some specific levels of the mind, they become an initial yet authentic part of the supposed extra-linguistic realities and worlds. For example, consider mantras in Hinduism and Buddhism. Symbols and languages are, basically, representations. In religious contexts, however, they are more than that; they set up the fundamental frames of religious worldviews.

3. Two Forms of Religious Minds: The Intentionality of Transcendental Filling and the Intentionality of Transcendental Emptying

It is time to be more specific. Three vital tasks are to be conducted: introducing the Husserlian idea of filled and empty intentionalities; finding out how they give rise to two types of intentionalities of religious spirituality; and, finally, explaining the way in which they bring about religious diversity and pluralism. Recall that our claim is that the human mind itself has some seeds for the diversity of religion. I shall call those seeds “the intentionalities of transcendental emptying and filling.” To spell them out is to show the philosophically colored husks of the religious soul. However, it aims to illuminate, I hope, the most general and structural features of it. In this regard, we are attempting to carry out a phenomenological description and analysis of religious experiences.

3.1. Husserlian Ideas of Filled and Empty Intentionalities

To present the point, let us start with a notable phenomenological insight into the nature of perceiving. Suppose that you are seeing the front side of a sacred statue in a church or a temple. We say that your mind is directed at an object, i.e., a statue. That is correct, but a more fine-grained phenomenological treatment is still possible. To this end, we now say that, in that case, your mind is directed upon the presence of the front side of the statue. Note that, as long as the statue is not totally transparent, you cannot see the back side of the statue; the back side is absent to you. Meanwhile, if you move around the statue, your mind becomes directed upon the presence of the back side of the statue, but its front side becomes absent to you. Does this mean that you are seeing two different objects? No. Whether it comes from the previous experiences or some innate ideas in the mind, you know that both the front side that may be present to you and its back side that may be absent to you belong to the same object.6

On the basis of such observations, Husserlian phenomenology provides us with a remarkable insight: When we have intentional experiences of an object, whether they are perceptual or intellectual, we experience something more than what is directly and immediately presented to us (Zahavi 2019, p. 11). We may dub this insight “Husserl’s idea of appresentation.” Husserl writes: “An appresentation occurs even in external experience, since the strictly seen front of a physical thing always and necessarily appresents a rear aspect and prescribes for it more or less determinate content” (Husserl [1931] 1960, p. 109).7 Concerning the statue example above, we eventually find that while your mind is directed upon the presence of the front side of the statue, your mind is also directed upon the absence of the back side of the statue, although you are not explicitly aware of it. We may call the former “filled intentionality” and the latter “empty intentionality,” and as far as we know that those two intentionalities are being directed upon the same object, some “identifying intentionality” is also posited (Sokolowski 2000, p. 40).

For the sake of argument, we focus on filled and empty intentionalities. Sokolowski has impressively clarified them in accordance with contemporary phenomenology. He writes: “Presence and absence are the objective correlates to filled and empty intentions. An empty intention is an intention that targets something that is not there, something absent, something not present to the one who intends. A filled intention is one that targets something that is there, in its bodily presence, before the one who intends” (Sokolowski 2000, p. 33). Here, the terms “intention” and “intend” should be read not as “(one’s) having a purpose in mind”, but instead as “(the mind’s) being directed upon an object or state of affairs.” He adds that, when intentional mental acts are being exercised, filled and empty intentionalities operate together; the mind co-intends both the presence and absence associated with an object (Sokolowski 1978, p. 22; 2000, pp. 17–18).

It should be noted that Sokolowski stresses the status and characteristics of empty intentionality that concerns the absent, and possibly absence itself. He writes that “Presence has always been a theme in philosophy, but absence has not been given its due. In fact, absence is usually neglected and evaded: we tend to think that everything we are aware of must be actually present to us; we seem incapable of thinking that we can truly intend what is absent. We shy away from absence even though it is all around us and preoccupies us all the time” (Sokolowski 2000, p. 36). Existentialists’ sagas about being and nothingness may have had their thematic origins in the notion of empty intentionality. This issue deserves notice. However, while keeping Sokolowski’s philosophical diagnosis in mind, our task is to uncover the idea that there may be some distinct forms of religious spirituality and religiosity associated with presence (being) and absence (nothingness). Sokolowski himself did not proceed to put forward this idea, but we will suggest and theorize it.

3.2. Religious Minds: The Intentionality of Transcendental Filling and the Intentionality of Transcendental Emptying

Now, to put it more precisely, how do filled and empty intentionalities generate the religious mind? Despite its complex appearance, this question may not be difficult to answer. This is because it is a matter of whether the object of an intentional state is empirical or transcendent. It is therefore suggested that, just as there are two forms of worldly intentionality, there are also two types of religious intentionality. I call these the “intentionality of transcendental filling (ITF)” and the “intentionality of transcendental emptying (ITE).” The former is a type of religious mind concerned with presence or being, while the latter is another type of religious mind, involved in absence or nothingness. They are “transcendental” in that: (1) the objects of those intentionalities are, at least to a certain extent, transcendent; and (2) such intentionalities prescribe one’s experiences and determine the direction and extent of one’s ontological commitment.8

Before going into the explication of such transcendental intentionalities, it would be interesting to take a brief glance at the widespread methodological maxim in religious pursuits connected to the terms “filling” and “emptying.” In attaining religious goals, most religious traditions, from shamanic rituals to those featured in world religions, teach us to empty our mind and fill it with something sacred, i.e., something that is ultimately religious (Johnston 1978; Habito 2004). This must be a right maxim that any religious persons need to follow. I do appreciate that idea.

The difficulty involved here is that the meaning of the maxim is, despite being seemingly clear and straightforward, not easy to pin down. It is metaphorically outstanding but theoretically naïve. Making matters worse, there is an unexpected danger in that some vagueness about that maxim may break the connection and continuity between the ordinary, natural mind and the transcendental, religious mind.9 As a result, the latter is often regarded as merely nonsensical or simply mysterious.

How can we resolve this matter? One proposal is that the religious ideas of filling and emptying can be refined by the notions of filled and empty intentionalities characterized above. Thus, we take religious filling to imply that one’s mind is directed upon presence as the ultimate, and we also take religious emptying to mean that one’s mind is directed upon absence as the ultimate. However, one should not reify absence or nothingness here. So, the meaning of the thesis may be that one sees everything as nothingness or impermanence. We will discuss this issue soon. At any rate, in just that way, some cryptic aspects of the religious mind can be diminished. Moreover, the traditional religious discourses on emptying and filling can be newly supported by a philosophical theory of intentionality. At this moment, we see how a Husserlian idea of intentionality is connected to building a theory of religious intentionality.

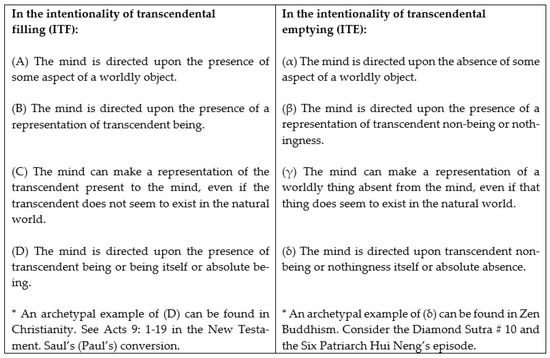

In the following, I shall try to make clear the vital features of ITF and ITE in a quasi-procedural manner. They are the theoretical results of the phenomenological induction that “are based on, but not fully in, the empirical historical data” (Allen 2005b, p. 18). The scheme of ITF and ITE is a descriptive and explanatory hypothesis that concerns the varieties of religious phenomena. Figure 1, below, is a pragmatic device in which we can compare ITF and ITE. Each one is made up of four phases or moments.10 Although they are not necessarily consequential or cumulative, one may call them the beginning stage, normal operation stage, transformation stage, and completion stage. Some brief comments will be added to each of them.

Figure 1.

Compare ITF and ITE.

3.2.1. The Intentionality of Transcendental Filling (ITF)

ITF has many characteristics, phases, and moments. I describe them using four propositions (A), (B), (C), and (D).

(A) “The mind is directed upon the presence of some aspect of a worldly object.” ITF starts with filled intentionality. (B), (C), and (D) work on the basis of (A), but it is not the case that all their qualities are reduced to (A). (A) is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for (B), (C), and (D). The reason we posit this first lies in showing the connection and continuity between the ordinary, natural mind and the religious, transcendental mind. In this scheme, the religious mind is not something entirely different from the ordinary mind. However, the mind associated with (A) is largely filled with worldly ideas, thoughts, and dispositions.

(B) “The mind is directed upon the presence of a representation of transcendent being.” Recall that symbols and languages have their own peculiar intentionalities. In (B), the mind is directed upon the presence of pictures, symbols, or linguistic expressions that are supposed to refer to transcendent beings. Representations of this sort become the objects of intentional mental states. In fact, this is a typical form of the religious mind. Many, or probably “most,” religious activities operate not on the level of the actual presence of a transcendent object, but on the level of its representational presence. As has already been pointed out, multiple intentionalities of the mind, symbols, and language are involved in (B). In this way, the mind in (B) is partially filled with religious objects and ideas.

(C) “The mind can make a representation of the transcendent present to the mind, even if the transcendent does not seem to exist in the natural world.” Note that the workings of the mind associated with (C) are based upon what we call the “act,” “content” and “background” of intentional states. In the end, (C) brings about a distinctive form of religiosity centered on presence, existence, or being. It is the familiar type of religiosity that is common to many individual religions. (C) is, to some extent, ontic in that the representational presence of a transcendent being counts as the ultimate ontological principle of the universe. In the meantime, it is partly methodological in that intentionality of this sort paves the way to (D). To achieve that aim, some special methods, such as prayer and contemplation, are adopted.

There is a weighty theoretical issue regarding the nature of presence in (A), (B), and (C). That is, when (A) concerns the presence of some aspect of an object, that presence is partly due to the knowing subject. Therefore, it contains an epistemic presence (slightly insinuating a commitment to the principle of esse est percipi). However, the character of presence changes in (B), (C), and (D). In (C), making a representation of the transcendent present to the mind (this may be, according to the terminology of phenomenology, called “presentification (Vergegenwärtigung)”) is both ontic and epistemic. Presence begins to be the ontological principle of the universe. Here, the mind is largely filled with something religious. An additional puzzle is: how does epistemic presence associated with perception transit to the ontological, metaphysical presence? This is a difficult matter, but there are several answers. One example is the Platonistic metaphysics and epistemology that starts with sense-experiences about the changeable and impermanent and, finally, ends with pure intellectual intuitions about the unchangeable and permanent.

(D) “The mind is directed upon the presence of transcendent being or being itself or absolute being.” This is the peak of ITF. It indicates a direct contact with a transcendent being, and it involves some mysticism. This is one central type of religious mind that comprises a complete form of spirituality and religiosity. It turns out that theistic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Muslim, relate to (D). Presence in (D) would be pure presence, freed from all absences. In relation to this, consider, for example, Paul Tillich’s idea of God as being itself, which includes, as its partial moments, several forms of non-being.11 In (D), the mind is largely or totally filled with something transcendent and sacred. The transition from (A) to (D) may be possible via the transcendent being’s special act, such as grace. Naturalistic philosophers and scholars would doubt or deny that transition because it makes excessive ontological commitments too easily. In this respect, one may remain in ITF, characterized by (A), (B), and (C), and thus be content with the naturalistic accounts of the religious. That may be reasonable. However, as far as religiosity is concerned, I do not deny the possibility of (D), and I am open to it.12

An archetypal example of (D) can be found in Christianity, i.e., in Acts 9: 1-19 in the New Testament. It says that: Saul (Paul), a strong opponent of Jesus, persecutes the followers of Jesus. On the way to Damascus, where he can arrest more people who believe in Jesus, he faces the presence of Jesus, a bright light from the sky, and the voice of Jesus states: “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9: 4), “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting” (Acts 9: 5), “Now get up and go into the city, and you will be told what you must do (Acts 9: 6).” Since then, his name, life purpose, and way of life radically changed, and he became a sincere disciple of Jesus and an actual founder of Christianity. What is it like to have an intentional mental state in which one directly encounters Jesus or God? Whatever the answer may be, there we see Saint Paul’s religious transformation, which is called a “metanoia.” The mind is totally filled with transcendent being.

3.2.2. The Intentionality of Transcendental Emptying (ITE)

ITE also has many characteristics, phases, and moments. I characterize them with four propositions (α), (β), (γ), and (δ).

(α) “The mind is directed upon the absence of some aspect of a worldly object.” ITE starts with empty intentionality. Recall that, in our perceptual experiences, we co-intend the presence and absence of some aspects of an object, and that these are the results of the interplay between filled and empty intentionalities.13 The workings of the latter and their correlates, i.e., absences, are quite implicit, and it is unfamiliar not only to us, but also to the theorists of intentionality. In this regard, it makes sense to say that absence or nothingness can be better grasped not by intellect but as is suggested by Heidegger, by some moods or emotions. Meanwhile, absence, nonexistence, or nothingness is frequently associated with negative psychological feelings and images, such as a sense of futility, transiency, nihilism, darkness, evil, death, etc. That is understandable, but it is not the essence of ITE. Rather, as shown in Zen Buddhism, it can possess something very positive, either methodologically or substantially. For example, its gist can be put as follows: Everything is impermanent. However, impermanence itself is also impermanent. We can therefore return to, and retrieve, those impermanent things with a new way of seeing.

(β) “The mind is directed upon the presence of a representation of transcendent non-being or nothingness.” Just as there are symbols, pictures, and languages that represent the presence of transcendent beings, there are also symbols, pictures, and languages that represent transcendent non-being or nothingness. Here, the mind is directed according to mere representations. Without such representations, however, we cannot see how that nothingness could manifest. What is of importance is that they are a means to realize a religious end. Thus, they should be discarded after achieving the religious goal. In (β), the mind is partially empty in a religious way.

(γ) “The mind can make a representation of a worldly thing absent from the mind, even if that thing does seem to exist in the natural world.” Here, too, the operations of the mind linked to (γ) are connected to intentional acts, content and background, taken as the bedrock of the mind. Finally, (γ) generates a very peculiar form of religiosity that is centered on absence, non-being, or nothingness. It is partly ontological in that absence or nothingness counts as the ultimate principle of the universe. Absence in (α) is, similarly to presence in (A), partially epistemic; but absence in (β), (γ), and (δ) becomes ontic, as well as epistemic, in that pure absence is considered as the ultimate ground and principle that explains the apparent existence of the world. However, as mentioned above, we should not reify absence as a thing or entity. The articulation of absolute pure absence or nothingness itself is difficult and operose. Meanwhile, ITE is also partly methodological in that it paves the way to the complete realization of (δ). To achieve that aim, some special methods, e.g., several distinct types of meditations, are adopted. In (γ), the mind is largely empty in a religious way.

(δ) “The mind is directed upon transcendent non-being or nothingness itself or absolute absence.” This is the peak of ITE. It is a complete realization of absolute pure absence or nothingness itself. Mahāyāna Buddhism, Zen Buddhism, and Taoism are good examples connected to ITE. In particular, Nāgārjuna’s idea of emptiness as dependent arising (Pratītyasamutpāda) provides us with a paradigm of such religiosity. We can also refer to the philosophical efforts of the Kyoto School, which aimed to uncover such a religious mind. Compared to ITF, it is, certainly, a different form of spirituality and religiosity. Here, the mind is directed upon absolute pure absence, freed from all the inessential, impermanent presences. Some mysticism is also involved. In (δ), the mind can be totally empty in a religious way.

We can find an archetypal example of ITE in Buddhism, i.e., the Sixth Patriarch Hui Neng in Chinese Zen Buddhism. It is reported that when Hui Neng was a poor woodman who was taking care of his mother, he once heard a passage in the Diamond Sutra, a main sutra in Mahāyāna Buddhism and then left his beloved mother to become a monk. The sutra says that “A disciple should develop a mind which does not rely on anything” (The Diamond Sutra, # 10, Johnson 2019, Tr.). What is it like to have a mind “which is in no way dependent upon sights, sounds, smells, tastes, sensory sensations or any mental conceptions” (The Diamond Sutra # 10)? I take it that in that case, the mind is directed upon pure non-being, nothingness itself, or absolute absence. The mind of this sort constitutes a distinct religious spirituality and, even, religiosity.

3.3. Two Types of Religious Minds and the Problems of Religious Diversity and Pluralism

Finally, we come to the last stage of argumentation. With the notions of ITF and ITE, some might be tempted to maintain that all religions are divided into two types, i.e., religions of presence, accompanied by transcendental filling, and those of absence, followed by transcendental emptying, and that the former contains Abrahamic religions, whereas the latter contains Buddhism and Taoism. That view makes sense, but it is a hasty judgement. Transcendental filling and emptying as the formal frames of the religious mind are different forms of spirituality and religiosity. However, actual individual religions are combinations of them.14 One should not fail to see this point. The crux of the matter is that the ways in which ITF and ITE are combined are many and varied. In this way, the diversity of religion is described, elucidated and explained by the scheme of ITF and ITE. Of course, a religion is formed by many factors. The mind is one of them. However, in that mind, whether the mind is individual or collective, there are already some seeds for the diversity of religion.

Consider the following two examples. Christianity is, certainly, a presence-centered religion, and ITF plays a major role in fulfilling its religious end, i.e., salvation by God. However, Christianity also has some features of emptying, particularly in the methodological dimension (Corrigan 2015). Thus, to live with God, one must totally empty oneself of all secular ideas, values, and possessions. This is, in my view, to exercise ITE as a critical religious means. Meanwhile, in Christianity, we also find some special form of emptying in the dimension of the transcendent. Consider the doctrine of kenosis (Cobb and Ives 1990). God emptied Himself of the features of Godhead and became Jesus; further, Jesus emptied himself of the features of God and became a human. In this way, Christianity includes those two types of ITF and ITE in a unique way.

What about Buddhism? Buddhism counts as an absence-centered religion, particularly when we consider Mahāyāna Buddhism and Zen Buddhism. As I have already pointed out, we humans have an inherent natural preference for presence or being. Therefore, we are not even aware that our mind is directed upon absence as well as presence. Perhaps that may have been the profound reason that Buddhism was not regarded as a real religion. However, there is ITE construed as the mind’s being directed upon absolute pure absence or nothingness itself. This plays a crucial role in fulfilling the aim of Buddhism, i.e., enlightenment or the realization of Śūnyatā. Here, emptying is considered to be both the means and the end. However, in Buddhism, ITE and ITF are intertwined, substantially or methodologically. It is surprising that a sect of Buddhism, “Pure Land Buddhism”, emphasizes the presence or being of the future Buddha. Moreover, many Buddhists, when reciting the mantras, bow to the Buddha statue, the historical Buddha, and Buddhahood. Their minds are, more often than not, directed upon the existence or presence of the Buddha. Nonetheless, Buddhism appears to be, foundationally, an absence-centered faith (Waldenfels 1976). Here, we also see some unique combinations of ITE and ITF.

From this consideration, we reach the following thesis: (III) The diversity of religion that gives rise to religious pluralism is, at least in part, due to the different ways in which those two religious intentionalities are combined and intertwined. However, why is this thesis counted as supporting religious pluralism as a normative stance on other faiths? I suggest two modest reasons for this: First, there are no logical reasons or ontological criteria for judging that a specific combination of ITF and ITE has sheer primacy or superiority over others. It seems that human’s preference for the actual or the present could be something biological, psychological, or cultural, but not, in itself, something purely religious. Second, as far as one can operate both ITF and ITE in their own mind, some embryos of the religious other seem to already exist there. This may be a reason why religious conversion can sometimes be made easily. What about dual or multiple religious belonging? These are extreme cases. In any case, the point is that it is, at least, ethically appropriate to see and respect some different religious seeds in one’s own mind as they are.

4. Concluding Remarks

Recall that there is a gap between religious diversity as a factual phenomenon and religious pluralism as a normative stance. I have attempted to bridge the gap between them, chiefly by means of presenting some bare bones of the essential frameworks of religious minds, called ITF and ITE. That task has been carried out by utilizing the notion of the intentionality of the mind. From the traditional viewpoint, a defining feature of directedness lies in its capability of representing non-existent entities. When one relates this idea to the matter of religion, does it imply that transcendent religious objects appearing in individual religions are, after all, non-existent entities? I will not directly answer this question. A Husserlian view of intentionality could respond to that matter as follows: Those transcendent religious objects may exist, and they can be present or absent to us. In addition, the fact that those objects are not present to us does not necessarily mean that they do not exist at all. To some, this would be a surprising, elegant answer. However, can one also infer that the fact that those objects are present to us does not necessarily mean that they really exist? This can be an unexpected, perplexing matter. By contrast, my suggestion is that there are at least two different types of intentionalities of religious spirituality that anyone could have. Due to some accidental structural features of the human mind, although there are other possibilities, it may primarily exercise just two essential types of the religious mind, i.e., transcendental filling and emptying, which are, respectively, concerned with presence and absence. The point is that the diversity of religion is partly due to many differences, in which they are combined, and also that religious pluralism has something to do with recognizing clearly those different seeds in the mind.

Thus, the results of this inquiry provide us with some serious tasks to be conducted. Of them, I mention two. One is that those results require us to conduct research that can explicate exactly how and in what ways those transcendental religious minds have appeared, and also have been combined, in the real history of religion. This is a new research agenda that necessitates the aid of comparative philosophy and religion. The other is that those results prompt us to refine an adequate, substantial method of religious, and particularly “interreligious,” studies. Despite its good intentions to understand the religious other rightly, those studies often lack a new rigorous method. Some ideas of ITF and ITE can be helpful here. For example, researchers can operate ITF and ITE in their own ways. It could help them to experience religious diversity and appreciate the pluralistic standpoint, at least in a simulated way. Of course, such a method requires a systematic treatment and theorization. I leave these matters for further research. For now, suffice it to say that the sources and grounds of religious diversity and pluralism lie, at least in part, in our mind. To some, this inquiry may appear to be unduly general and extensive. That is a sensible worry, but if we stick to it too much, we will never be able to proceed. We challenge that worry. It is sometimes necessary to do so to command a clear purview about crisscrossing, complicated matters.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Hick’s idea of the one ultimate reality was markedly appeared in his 1973 book, especially in chapters 8, 9 and 10. Since then, he continued to refine and develop that idea. (Cf. Hick 1973, 1985; [1989] 2004, chps. 14, 15, and 16) Note that Hick used several different terms to refer to that reality, such as “the Transcendent,” “the Ultimate,” “Ultimate Reality,” “the Supreme Principle,” “the Divine,” “the One,” “the Eternal,” “the Eternal One,” and “the Real” (Hick [1989] 2004, p. 10). It is important to see that Hick preferred to use the term “the Real” to encompass both theistic and non-theistic religions. |

| 2 | It deserves notice that there can be several forms or degrees of religious pluralism, from the weakest to the strongest. I characterize these as follows: (a) From a sociocultural point of view, without making explicit truth claims or ontological commitments, one can simply accept that there are many different religions and religious worldviews realized in their distinct teachings, ethics, rituals, practices, or institutions. This would be a form of cultural pluralism about religion, and it is in accordance with naturalistic approaches to religion. (b) From a philosophical perspective, particularly with the idea of truth, one can affirm that all the established individual religions having their own doctrines and creeds are, if they are true, equivalently true. The character of this pluralism is determined by how one takes the meaning of the term “true” or “truth” in religious contexts. (c) From a religious viewpoint, one can acknowledge that there could really be many different ultimate realities propounded by individual religions, even though we do not fully know what such realities are like. This is, perhaps, the strongest form of pluralism, which may be called, as suggested by David Griffin, “deep religious pluralism” (Griffin 2005, p. 29). I think that Hick, while adopting pluralism (b), either modifies pluralism (c) or deliberately goes beyond it. Either way, when it comes to grounding religious pluralism, Hick seems to take it one step further. Whereas I accept and assume the possibility of pluralism (c) in a straightforward manner, and try to show that the grounds of religious diversity and pluralism may lie partly in the human, i.e., the human mind and body. |

| 3 | This idea of Searle’s is, to some extent, similar to what Husserlians call the (internal or external) horizon of intentional experience. According to Searle, there are two types of the background of intentionality: biological (or “deep”) and cultural (or “local”) backgrounds (Searle 1983, pp. 143–44). Could this imply that there are also two types of religiousness, i.e., religiosity rooted in the biological and religiosity grounded on the cultural? This consideration, when combined by the ideas of ITF and ITE, will generate some stimulating speculations about the origin and nature of religion. They could be quite different from the purely naturalistic, evolutionary accounts of religion. |

| 4 | Following Steinbock’s suggestion, we may call it “verticality” associated with experiencing the meanings of religious symbols and languages. See note 10. |

| 5 | Husserl maintains that the intentionality of language, i.e., what Husserl calls “signitive intentions”, are empty (See Husserl [1901] 1970, p. 233). In that regard, empty names in our languages turn out to be doubly empty. Meanwhile, Searle presents the view that the intentionality of language is secondary, derivative, or “observer-dependent” (Searle 1998, pp. 93–94). We can take in Husserl’s and Searle’s positions, but still emphasize, à la Wittgenstein and Heidegger, the crucial importance of having a language in our lives. |

| 6 | This issue is delineated by Husserl as follows: When we perceive an object, “it [the object] is not given wholly and entirely as that which it itself is. It is only given ‘from the front’, only ‘perspectivally foreshortened and projected’ etc. While many of its properties are illustrated in the nuclear content of the percept, (…) many others are not present in the percept in such illustrated form: the elements of the invisible rear side, the interior etc., are no doubt subsidiarily intended in more or less definite fashion, symbolically suggested by what is primarily apparent, but not themselves part of the intuitive, i.e. of the perceptual or imaginative content, of the percept” (Husserl [1901] 1970, p. 220). Husserl develops this insight into the idea of appresentation (Appräsentation). |

| 7 | Alfred Schutz illuminates this idea in the following way: “The appresenting member ‘wakens’ or ‘calls forth’ or ‘evokes’ the appresented one. The latter may be a physical event, fact, or object which, however, is not perceivable to the subject in immediacy, or something spiritual or immaterial” (Schutz 1962, p. 297). The issue of how Husserl’s idea of appresentation can be utilized in religious inquiries has been pursued in an interesting way. For example, see Barber (2017). (I think that Jean-Luc Marion’s idea of saturated phenomena can also be interpreted as a philosophical and theological development of Husserl’s notion of appresentation. Note that the momentous example of saturated phenomena is, according to Marion, revelation). |

| 8 | This is not to equate the religious with the transcendental. Condition (1) comes from the medieval understanding of the transcendental, and condition (2) is basically taken from Kant’s notion of transcendentality that concerns the conditions of possibility of experience and cognition. It should be acknowledged that religion has, as delineated by Ninian Smart, many dimensions, such as experiential, mystic, doctrinal, ethical, ritual and social dimensions (Smart [1999] 2000). Nonetheless, the transcendental characters of religion presented in conditions (1) and (2) pervade, explicitly or implicitly, all those dimensions in various ways. For example, suppose that you give a good luck charm to your beloved friend. It does not necessarily have to do with a particular religion. Yet your mind and actions associated with that specific entity still display an embryonic or elementary form of religious transcendence and transcendentality. The intended meaning of the charm goes beyond what is physically given. This way, I take the notion of transcendence to be “going beyond what is directly given.” This is a minimal, formal understanding of that notion. I assume that all individual religions have some commonality based on the notion of transcendence thus considered. However, the point I wish to emphasize with regard to ITF and ITE is that there seem to be many distinct ways and types of such transcendence, and this leads to the idea that the religiosity of presence (being) and that of absence (nothingness) are not the same. I think that the terms “religion” and “transcendence” are, borrowing from Wittgenstein’s jargon, family-resemblance concepts. A merit of this view is that, in comparison with the uniformist or absolutist view, it can help us to embrace and understand the diversity of religion more widely and appropriately. |

| 9 | I take it that Tillich strongly defends the continuity between the ordinary, natural mind and the religious, transcendental mind when he states that “Religion is not a special function of man’s spiritual life, but it is the dimension of depth in all of its function” (Tillich 1959, pp. 5–6). In general, Zen Buddhism also stresses that continuity. There we are told that the ordinary mind is the Way. |

| 10 | Those phases or moments combined with ITF reflect what Steinbock calls the “vertical character of religious experience.” Vertical experiences are meant to be higher-level uplifting experiences attached to morality, ethicality, religiosity, and mysticism. It is “a distinctive kind of experiencing that is ‘absolute,’ immediate, spontaneous, beyond our calculation or control, creative, each time ‘full,’ not partial, not mixed with absence, not given as lacking” (Steinbock 2007, p. 146). The archetypal example of it is, according to Steinbock, epiphany. In my view, verticality nicely accords with ITF appearing in Abrahamic religions. But it is not certain whether and how it can cope with ITE. (Notice the term “absence” in the quotation above.) ITE surely seems to have some vertical character. However, verticality contained in ITE appears to be different from that of ITF. Steinbock mentions the possibility of different types of verticality, but we do not yet know exactly what they are like. Pinning down this issue will help us to refine the theory of ITF and ITE. |

| 11 | It is not surprising that Tillich, as a Christian theologian, defends a being-centered religiosity. He states that “[B]eing ‘embraces’ itself and nonbeing. Being has nonbeing ‘within’ itself as that which is eternally present and eternally overcome in the process of the divine life” (Tillich 1952, p. 34). He maintains that there are several forms of nonbeing, such as ontic, spiritual, and moral nonbeing, and that they are finally subjugated by being itself, i.e., God. Here, we can ask, is it legitimate to judge that Tillich fails to see some unique religiosity of nonbeing or nothingness? This could be a serious issue that requires meticulous consideration. If one adopts a traditional exclusivist theology, the answer will be “no.” However, if one espouses a pluralistic interreligious position, it could be “yes.” I think that there can be a third answer to the question. |

| 12 | After all, thanks to this point, the theory of ITF (and ITE) can distance itself from anti-realism about religion and religiosity, such as idealism, constructivism, conventionalism, or correlationalism. |

| 13 | The principle of co-intending works in empirical cognition. However, it is not certain whether it can also work in trans-empirical cognition. This seems to be an unfathomable philosophical issue. See note 14. |

| 14 | In the western philosophical and religious traditions, it is, probably, Meister Eckhart who appraised this combinatorial feature of religiosity most sharply and forcefully. Perhaps that is the reason why his theological ideas were, from time to time, considered to be heretical. Interestingly, Daisetsu T. Suzuki considered him as “an extraordinary Christian” (Suzuki [1957] 2002, p. 2, my emphasis). Even some recent scholars have regarded him as a Buddhist Christian. I am not sure how much importance this interpretative issue could have, but I repeatedly emphasize the subtleties and complexities of the two distinct forms of religious mind (ITF and ITE). |

References

- Allen, Douglas. 2005a. Phenomenology of Religion. In The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. Edited by John Hinnells. London: Routledge, pp. 182–207. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Douglas. 2005b. Major Contributions of Philosophical Phenomenology and Hermeneutics to the Study of Religion. In How to do Comparative Religion? Edited by René Gothóni. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, Michael. 2017. Religion and the Appresentative Mindset. Open Theology 3: 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, John, Jr., and Christopher Ives, eds. 1990. The Emptying God: A Buddhist-Jewish-Christian Conversation. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, John. 2015. Emptiness: Feeling Christian in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, David. 2005. Religious Pluralism: Generic, Identist, and Deep. In Deep Religious Pluralism. Edited by David Ray Griffin. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Habito, Ruben. 2004. Living Zen, Loving God. Boston: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hick, John. 1973. God and the Universe of Faiths. Oxford: Oneworld Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hick, John. 1985. Problems of Religious Pluralism. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hick, John. 2004. An Interpretation of Religion, 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. First published 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, Edmund. 1970. Logical Investigations, Volume II. Translated by John Niemeyer Findlay. New York: Humanities Press. First published 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, Edmund. 1960. Cartesian Meditations: An Introduction to Phenomenology. Translated by Dorion Cairns. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. First published 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Alex. 2019. Diamond Sutra—A New Translation. Available online: https://diamond-sutra.com/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Johnston, William. 1978. The Inner Eye of Love: Mysticism and Religion. Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Co Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kiem, Youngjin. 2021. Naturalism, Wittgensteinian Grammar and Interreligious Exploration. Neue Zeitschrift für Systematische Theologie und Religionsphilosophie 63: 163–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindbeck, George. 2009. The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. First published 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sajama, Seppo, and Matti Kamppinen. 1987. A Historical Introduction to Phenomenology. London: Croom Helm. [Google Scholar]

- Scheler, Max. 2017. On the Eternal in Man. Translated by Bernard Noble. New York: Routledge. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, Alfred. 1962. Symbol, Reality, and Society. In Collective Papers I: The Problem of Social Reality. Edited by Maurice Natanson. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, John. 1983. Intentionality: An Essay in the Philosophy of Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, John. 1998. Mind, Language and Society. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, Ninian. 2000. Worldviews: Crosscultural Explorations of Human Beliefs, 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. First published 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W. David. 1989. The Circles of Acquaintance: Perception, Consciousness, and Empathy. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski, Robert. 1978. Presence and Absence: A Philosophical Investigation of Language and Being. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski, Robert. 2000. Introduction to Phenomenology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbock, Anthony. 2007. Phenomenology and Mysticism: The Verticality of Religious Experience. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Daisetsu. 2002. Mysticism: Christian and Buddhist: The Eastern and Western Way. London: Routledge. First published 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Swidler, Leonard. 2016. The Age of Global Dialogue. Eugene: Pickwick Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tillich, Paul. 1952. The Courage to Be. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tillich, Paul. 1959. Theory of Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tillich, Paul. 1987. The Nature of Religious Language. In The Essential Tillich: An Anthology of the Writings of Paul Tillich. Edited by Frank Forrester Church. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. First published 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Waldenfels, Hans. 1976. Absolute Nothingness: Foundations for a Buddhist-Christian Dialogue. Translated by James Wallace Heisig. New York: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, Dan. 2019. Phenomenology. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).