Abstract

This article explores the process of creeping radicalization within the Georgian Orthodox Church and its implications for building societal resilience in the country. In doing so, it aims to fill the gap in the literature on the role of dominant religious organizations in resilience building in Georgia and in the broader post-Soviet region. Our analysis ascribes a mostly negative impact to the Georgian Orthodox Church on the country’s societal resilience. We identify two possible mechanisms with which the Georgian Orthodox Church undermines societal resilience in Georgia: (1) by decreasing general trust in society and (2) by inspiring anti-Western narratives, which undermine the basis of Georgia’s national identity.

1. Introduction

This article seeks to unpack the controversial role played by the Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC) in the Georgian resilience-building process. We argue that the GOC acts as a spoiler of societal resilience in Georgia. Our main hypothesis suggests that the GOC undermines societal resilience in two major ways: by weakening social trust and undermining Georgia’s pro-European drive. While the focus of this article is on Georgia, the results can perhaps be extrapolated to include other regional post-Soviet states, since the challenges identified in the article are to a certain extent identical in various parts of the former Soviet Union.

The subject of this article lies at the intersection of two broad topics of political science—religion and resilience—and intends to contribute to both strands of the literature. There is a rich body of literature on different aspects of religion and religiosity in Georgia and the South Caucasus. A publication edited by Jödicke (2017) skillfully connects geopolitical and religious issues and analyzes the role of religion in the South Caucasus from the perspective of soft power and external influences. Filetti (2013) explores “the relationship between religiosity and democratic values” in Azerbaijan and Georgia, and Charles (2010) unpacks “the determinants of trust in religious institutions” in the three South Caucasus countries. A number of studies focus more narrowly on various aspects of the GOC: the impact of the GOC on European integration (Kakachia 2014) and liberal-democratic norms (Minesashvili 2015, 2017), the connection between the GOC and nationalism (Zedania 2011) as well as attitudes and trends within the GOC itself (Gavashelishvili 2012; Kakabadze 2021). The academic literature on resilience building in Georgia and the South Caucasus region is more modest. There have been only a few studies so far analyzing aspects of resilience building in Georgia and the broader region. Most of them have a narrow focus on the role of external actors in the resilience-building process (Kakachia et al. 2021; Forker and Lebanidze 2022; Mikhelidze 2018; Lavrelashvili 2018). A few other studies focus on the pandemic (Valiyev and Valehli 2022; Kandelaki and Lebanidze 2022) and social (Babayev and Abushov 2022) resilience in the South Caucasus region.

While the literature on resilience and religion in the South Caucasus has been on the rise, so far there have been virtually no studies about the interconnectedness or any kind of causal relationship between the two social phenomena.1 This is where this article comes in to fill the research gap. By looking at the interconnectedness between the two phenomena, we intend to unpack the impact of the Georgian Orthodox Church, which is the dominant religious community in Georgia, on the resilience-building process in the country.

Before we proceed with the empirical analysis, it is important to provide a few conceptual clarifications. First, we need to unpack the meaning of resilience, which is widely considered as an essentially contested concept (Grove 2018; Chandler and Coaffee 2016). Resilience entered the political and social sciences a few decades ago and has, since then, managed to establish itself as a key attribute of successful governance. Resilience building is not just academic slang, however; it also dominates many policy areas and has become a central element of governance for the majority of institutional actors and developmental organizations, such as the EU, NATO, the UN, and USAID. Yet, to this day, resilience remains a fuzzy and somewhat overused term. One of the pioneering authors on the subject of resilience in political sciences, David Chandler, defines resilience as “the internal capacity of societies to cope with crises, with the emphasis on the development of self-organization and internal capacities and capabilities rather than the external provision of aid, resources or policy solutions” (Chandler 2015, p. 13).

Interestingly, academic definitions of resilience are quite close to how policy actors define it in their strategic documents. For instance, according to the European Commission (EC), resilience “refers to capacity of societies, communities and individuals to manage opportunities and risks in a peaceful and stable manner, and to build, maintain or restore livelihoods in the face of major pressures” (EU Commission 2017).

Both definitions include two key components of resilience—proper crisis and risk management (“bouncing back”) and capability of self-organization and self-development (“moving forward”). Another challenging task is how to operationalize resilience. Stollenwerk et al. (2021) provide a parsimonious analytical framework for deciphering sources of resilience in countries neighboring the EU. They identify three sources that are necessary for strong societal resilience: social trust, legitimacy of governance actors, and effective design of governance institutions (ibid.). Based on this taxonomy, we can identify two causal mechanisms through which certain dynamics or phenomena can impact resilience: (1) by interacting with risks and crises that society faces (the “bouncing back” dimension) and (2) by interacting with sources of resilience (the “moving forward” dimension) (cf. Kakachia et al. 2021). The two mechanisms can be interconnected but can also function in parallel to each other.

Finally, we need to also define how we understand (religious) radicalization. Radicalization, like resilience, is a fuzzy concept, and different scholars, international institutions, and governmental agencies define it in various ways (Kundnani 2012; Schmid 2013). Some interpretations connect radicalization to adoption of radical political or religious views that lead to “legitimization of political violence” (Jensen 2007, in Schmid 2013, p. 17) and “the rejection of democratic principles” and “utilization of violence (…) to achieve political goals” (Ashour 2009, p. 4) or “the use of undemocratic methods (means) that may harm the functioning of the democratic legal order” (AIVD 2005, p. 13). From these various interpretations, this article utilizes a broader understanding of radicalization, one that does not only include acts of physical violence but also non-physical aggression, such as verbal abuse or hate speech directed against liberal-democratic order and also against actors who promote democracy and rule of law in Georgia.

Now that we have clarified the key terms, the next part of the article will first provide an overview of recent trends towards illiberal radicalization within the GOC and then analyze to what extent these dynamics have strengthened or weakened the risks and sources of societal resilience in Georgia.

2. Materials and Methods

In terms of methodology, this article draws on qualitative research methods. Content analysis of primary and secondary sources was used to trace the evolution of radicalization trends within the Georgian Orthodox Church. We systematically analyzed official statements, speeches, and interviews by the Catholicos-Patriarch and other high-ranking representatives of the GOC. The timeline of the data selected for the analysis covers the years 2010–2021. Texts (speeches and interviews) were sampled based on the public prominence and position of the actors. The sources analyzed included both Georgian (“Civil Georgia”, “Agenda”, “GIP”, Liberali, etc.) and international (Eurasian Daily Monitor, Caucasus Analytical Digest, “D.RaD”, etc.) sources. To obtain statistical information for the article, we consulted public opinion surveys from the International Republican Institute, Caucasus Barometer, and World Values Survey.

For the review of the academic literature, we consulted scholarly articles across a variety of disciplines, from international relations to religious and radicalization studies and the literature on resilience building from various fields of study.

In terms of research design, we employed a positivist explanatory framework. While we have avoided explicit use of causal hypotheses, we assumed implicit causal linkage between radicalization processes within the GOC and the degree of societal resilience. We analyzed causality between the two phenomena by examining the probable impact of radicalization within the GOC on sources of resilience as a main causal mechanism.

3. Radicalization of the GOC and Its Impact on Sources of Resilience in Georgia

3.1. GOC—From Pragmatic Balancer to Radicalized Actor

Since Georgia regained its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the Georgian Orthodox Church has established itself as perhaps the most influential social institution in the country. To this day, the GOC remains one of the most popular institutions in the country, outperforming most other public and private institutions and actors. Its relationship with the Georgian state is based on the Concordat, a constitutional agreement made between the two in 2002. This agreement gives the Church tax exemption and provides substantial state support, either financially or in terms of acquiring land and buildings (Ghavtadze et al. 2020, pp. 58–65). However, even though this agreement grants major privileges to the GOC in comparison to other religious communities, it still does not per se imply discrimination. This relationship can be described as close to the concept of a cooperative model of secularism where (in contrast to liberal secularism) state support of a particular religion is a common practice.

The high standing of the GOC is linked to the personality of Georgia’s long-serving Catholicos-Patriarch Ilia II, who has been in charge of the GOC since 1977. To this day, Ilia II remains the most popular personality in the country. In the 2022 public opinion survey conducted by the International Republican Institute (IRI), a staggering 88% of Georgians held favorable views of him (IRI 2022, p. 26). The second most favorable person—the acting mayor of Tbilisi—received only 55% (ibid.). The constantly high figures of popularity of the Patriarch are in contrast to the popularity of the GOC itself, which is also high (68%) but has been declining slightly lately and was recently overtaken in popularity by the Georgian army (74%) (IRI 2022, p. 27). The unique position of the GOC is often reflected in the state’s approach and policies. As a good illustration of this, one could mention the statement of the Prime Minister of Georgia in 2017 that “secularism” in the classical sense was misplaced in Georgia and that the relationship between the state and the Church in Georgia was a “unique model” (Civil Georgia 2017).

The high level of authority of the GOC has always been valued by Georgia’s political class. Ruling elites in Georgia have always tried to capitalize politically on close relations with the Church. Eduard Shevardnadze, Georgia’s second and president, ensured the signing of the constitutional agreement (the Concordat) with the GOC, which granted the Church numerous privileges. Shevardnadze’s successor, Mikhail Saakashvili, and his United National Movement (UNM), while pushing for a liberal-secular reform agenda, continued cozying up to the GOC. State funding for the GOC during Saakashvili’s presidency in 2004–2013 increased by almost 12 times, from GEL 1.64 million in 2004 up to GEL 25 million in 2013 (Metreveli 2016, p. 10). The Georgian Dream (GD) government, which has been in power since 2012, has further increased the state funding of the GOC and continued granting the Church numerous privileges and various assets of wealth (OC Media 2019b).

The unique maneuvering skills and pragmatic balancing of Patriarch Ilia II were also the main reasons behind the GOC’s ascent as the dominant institution in the country. On the one hand, the GOC had been a vocal opponent of the proliferation of liberal values, especially of LGBTQ rights, and has often ended up promoting social-conservative and illiberal narratives. In doing so, the Church positioned itself as a “defender of traditional values” (Kakabadze 2021, p. 15). However, the GOC’s radical conservative image was balanced by the Patriarch’s moderating impact. Ilia II many times expressed his support for Georgia’s European integration to neutralize the anti-Western narratives promoted by numerous influential clergymen. He argued on various occasions that “everything should be done to allow Georgia to become part of European democratic structures” (Agenda.ge 2016) and that the GOC would “do its best to make this idea [of European integration] come true” (Agenda.ge 2014).

Ilia II also skillfully maneuvered in the domestic political arena. While Georgian politics has always been messy and shaped by a high degree of political radicalization and societal polarization, the Patriarch managed to avoid the involvement of the Church in partisan politics and has established himself as a neutral arbiter of last resort. For instance, he acted as a key mediator in one of the worst contemporary political crises, the government’s massive crackdown on opposition protests in November 2008 (Civil Georgia 2008; VOA 2009). The Patriarch met with opposition leaders and the government several times and asked protesters to de-escalate. The involvement of the Patriarch in the process, with his high authority, led to temporal de-escalation and ended up with the then-president Mikhail Saakashvili’s re-election in a snap election (Metreveli 2016, p. 10).

In sum, pragmatic balancing between contrasting poles has been the hallmark of Ilia II’s reign as Patriarch of Georgia. The Georgian Patriarch has managed to balance skillfully between pro-Western and radical conservative narratives in the international arena and between government and opposition in the domestic arena. In so doing, he has turned the GOC into an indispensable mediator of last resort, which would provide an arena for reconciliation every time the country is struck by political crises between the government and opposition. As Górecki notes, in his speeches, Ilia II “never openly supported any political party, instead calling on the public figures to engage in dialogue and to take responsibility for the state” (Górecki 2020, p. 2).

The last decade, however, has seen a dramatic shift within the GOC. Some influential bishops and the radical branch of the clergy have started actively promoting anti-European and anti-liberal narratives (Civil Georgia 2021), and there is hate speech among the clergy, particularly against the LGBTQI+ community, but hate speech concerning other social and political issues has also increased (Lebanidze and Kakabadze 2021). The hate speech and illiberal propaganda was soon accompanied by an increase in violence organized by the radical right wing and Orthodox groups, with the involvement of radical representatives of the clergy. For instance, Orthodox priests were actively involved in several anti-Pride marches organized by radical-conservative and far-right groups in Tbilisi, which ended up in extreme violence against Pride organizers and journalists (BBC 2013; OC Media 2019a; Civil Georgia 2021). In this regard, a significant milestone was the crackdown on the Pride march on 17 May 2013. After the incident, the Church declared the 17 May as the Day of the Strength of Family Ties and Purity. In the special statement issued by the Georgian Orthodox Church, it says:

Destruction of purity of the family and declaration of unnatural and wrong relations as a natural condition is unacceptable for the majority of the Georgian population, despite their faith. … Church reveals sin and fights against sin itself, its public propaganda, because such attitude angers God and causes big punishment from God, therefore our Church tries to protect the nation from legalization of immorality and from spiritual violence.(Civil Georgia 2014)

What is most problematic though is the tendency among high-ranking clergy to connect the criticism of LGBTQI+ rights with the demonization of the West. Illustrative in this regard is the commentary by Archpriest Theodore Gignadze—famous for holding public meetings with students and giving public talks and lectures—on the anti-discrimination bill adopted by the Georgian Parliament in 2014:

Demonization of the West is often accompanied by pro-Russian narratives. For instance, during an interview with the conservative TV channel Kartuli Arkhi in 2015, Archpriest Gignadze claimed Georgia was ruled by the West:This law is dangerous for Georgia’s future. Where there is no Christ, we have nothing to do there. … On the example of Holland, we can easily see what problems this law implies. 50 years ago, the lifestyle in this country was radically different. Families were patriarchal and traditions were respected. Today propaganda on same-sex marriages and depravity is going on. Pedophilia and incest have almost become the norm. Is it said that the drop can drill a stone. This law will be the beginning of planting poison in humans’ consciousness and these sins will gradually become norms among us.(Kviris Palitra 2014)

I remember the Soviet Union very well, … and now when I look at them, they are not free. If back then they were being ruled from the Kremlin, now they are being ruled from the west, Washington. But with the only difference that we were part of the republic of a common country, with equal rights, while today you are not even a state [meaning Georgia has lower status than any state in the USA].(Tabula 2015)

Anti-Western narratives were also spread after the 2021 anti-Pride march crackdowns organized by far-right groups in Tbilisi, where several priests were also involved (Gegeshidze and Mirziashvili 2021). The march was followed by a massive crackdown on Pride protesters and journalists which left one journalist dead and many injured. In the aftermath of the events, a high-ranking cleric from the GOC, Metropolitan of Vani and Baghdati Diocese, accused the US and the EU embassies of forcing “warped views” and “profligate, obscene and depraved ideals” on Georgian society (Civil Georgia 2021). The Patriarch himself has recently also become more vocal in expressing illiberal opinions against the Pride marches in Tbilisi and LGBTQ rights (BBC 2013; OC Media 2019a).

In parallel to voicing conservative views, the GOC leadership is often transmitting a narrative that is coming from the Kremlin. For example, in 2013, as Ilia II was visiting Russia, he praised Stalin, calling him a leader who was aware of Russia’s importance to the world (Netgazeti 2013). This discourse goes hand-in-hand with Putin’s so-called conservative turn after 2012 (Sharafutdinova 2014). For example, a group that is closely associated with the GOC, Martmadidebel Mshobelta Kavshiri (MMK), which in translation means the Union of Orthodox Parents, is known for its active criticism of the West, accusing it of conspiring against “traditional values”. The late Davit Kvlividze, the conservative hardliner clergyman of the MMK, in a 2016 interview with a local tabloid argued that:

The European Union is dismantling and where are they [the Georgian government] going? Or what kind of historical choice are we talking about, which Georgian king was called the king of Europe? … let us move later, to the nineteenth century, when Georgia joined Russia and Georgians got the European look, from where did they get?—from Petersburg. … Today, talking about this is considered shameful, you say something, somebody will appear and call you a Russian spy, it is interesting to know whose spies they are themselves….(Sakartvelo da Msoflio 2016)

Some analysts link the radicalization turn within the GOC with the 2012–2013 change in power in the country from Mikhail Saakashvili’s United National Movement (UNM) to Bidzina Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream (GD). According to Górecki (2020, p. 4), it “was followed by an increase in aggression on the part of Orthodox priests and believers targeting representatives of minority groups.” Moreover, the Church finds it more difficult to play its traditional role of a neutral arbiter in the Georgian political arena (Lebanidze and Kakabadze 2021).

It is hard to unpack the reasons behind the Church’s recent radicalization trend, but interestingly, it coincided with a period of power transition within the patriarchate of the GOC. The long-serving Patriarch of Georgia Ilia II, who has been in charge of the GOC for 44 years, turned 89 in 2022 (Agenda.ge 2022). In 2017, he appointed Moscow-educated metropolitan Shio Mujiri as a Patriarchal Locum Tenens (OC Media 2017). This increases the chances for the latter to be elected as the new Patriarch, but procedurally, elections still need to take place,2 and in this situation, the power struggle within the Church continues (ibid.).

The GOC has always been a heterogenous organization harboring a multiplicity of opinions. While the majority of clergy came from the more radical-conservative end of the ideological spectrum, some clergymen held more moderate views. However, during the transitional period within the GOC, the radical illiberal voices have become more visible, and the official position of the Church has also become more radicalized on many socio-political issues. It is hard to guess the current balance between the radical-conservative and moderate camps within the GOC, but perhaps the data provided by the Jamestown’s article on the number of supporters granting autocephaly to Ukraine’s Orthodox Church among the GOC’s Holy Synod could give a good estimate (Menabde 2019). According to the article, only six out of thirty-eight standing members of the Holy Synod supported Ukraine’s autocephaly (Menabde 2019).

In sum, we can observe the drifting of the GOC over the last decade away from a role of neutral observer towards a more radical and illiberal actor. While the GOC has always been skeptical about certain liberal-democratic norms such as minority rights, recently, part of its clergy and believer community have turned more radical both in action and the articulation of their normative ideas. In the past, the GOC served as both the social glue in Georgia and a significant marker of national identity of contemporary Georgia (Lebanidze and Kakabadze 2021; Gugushvili et al. 2015). However, over the last decade, the GOC has partially abandoned its “historical position of moral superiority and political neutrality” and has taken the road of creeping radicalization (Lebanidze and Kakabadze 2021).

3.2. The GOC as a Spoiler of Resilience

3.2.1. The GOC and Social Trust

We can think of two mechanisms as to how radicalization of the GOC undermines Georgian societal resilience: (1) by negatively impacting social trust and (2) by inspiring anti-Western narratives which weaken the basis of Georgia’s national identity.

With regard to the first mechanism, it can be argued that the GOC undermines social trust in Georgia by contributing to societal divisions. While the GOC acts as a social glue for its fellowship, it contributes to the isolation of other societal groups and to the creation of social cleavages at a broad societal level. This could have a generally negative impact on social trust, which has been notoriously low in Georgia in contrast to the much higher personal and group-based trust (Table 1). It is certainly not only the GOC that destroys social cohesion in Georgia. Societal fragmentation has become one of the negative hallmarks of Georgia, shaped by the high degree of party-led radicalization and societal polarization. Low social trust can be traced back further to other socio-economic factors such as a negative experience with a top-down neoliberalism, a high degree of inequality and societal stratification, widespread poverty, and unemployment. It is therefore a challenging task to isolate the negative impact of the GOC from other socio-political triggers. However, we can assume that the tribalism and discriminatory policies pursued by influential clergy can have a negative impact on societal divisions and the already low level of generalized social trust in Georgia.

Table 1.

Social trust in Georgia (World Values Survey Association 2021).

We can perhaps also discern negative influences from the GOC on social trust by looking at causal mechanisms for increasing generalized social trust. Börzel and Risse identify two such mechanisms which can contribute to the increase of generalized social trust: “generalization of group-based trust through the inclusiveness of social identities” and “building generalized trust through the impartiality of institutions” (Börzel and Risse 2018, p. 22). In the case of Georgia, it can be argued that the GOC’s actions and narratives undermine the effectiveness of both mechanisms. Regarding the first mechanism, the tribalism of the GOC precludes the inclusiveness of social identities and the creation of a universal civic identity which would extend to all parts of the population. The de facto impunity of GOC clergy also undermines the second mechanism—the impartiality of institutions—and promotes instead divisive social norms such as (the perception of) selective justice. Most importantly, the GOC’s divisive policies make it more difficult to incorporate minority groups in the country’s national resilience-building agenda. This could further widen an already existing “gap in perceptions about Georgia’s national priorities and vulnerabilities among some of Georgia’s minority groups and the rest of the population”, undermining a development of civic-national consciousness and a strong societal resilience, based on a whole-of-society approach (Kakachia et al. 2022, p. 12).

3.2.2. The GOC and Georgia’s National Identity

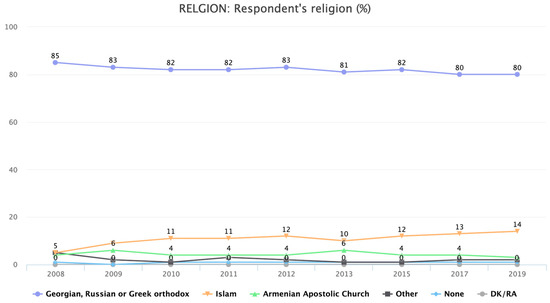

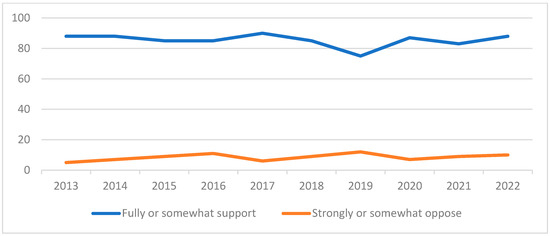

The GOC also undermines the societal resilience of Georgia by weakening the fundamentals of its national identity. Since the end of the Cold War and the regaining of independence from the USSR, the national identity of the new Georgian state was built around two central ideas: the “Return to the European family” and a place in Orthodox Christianity. An absolute majority of Georgian citizens consider themselves to be Orthodox Christians (Figure 1) and support Georgia’s membership in the EU (Figure 2). Both figures have been constantly high with some insignificant variations.3

Figure 1.

Which religion or denomination, if any, do you consider yourself to belong to? (Caucasus Barometer 2019).

Figure 2.

Do you support or oppose Georgia joining the EU? (IRI 2022, p. 68).

Hence, it can be argued that pro-Europeanness and Orthodox Christianity represent the two pillars of Georgia’s national identity and which coexisted harmoniously for three decades, partly due to the flexibility of the GOC. The GOC often resorted to pragmatism to successfully manage “a difficult balance between traditional values on the one hand, and Georgia’s European orientation and path towards western integration on the other” (Lebanidze and Kakabadze 2021).

The GOC’s recent radicalization, however, undermines the fundamentals of Georgia’s identity building. In the long term, this could result in weakening of permissive consensus in the religious section of the population on the country’s European integration and turn it into a constraining dissensus.4 Georgian society is already quite fragmented along political, social, and cultural lines, and European integration is among the very few denominators of national unity. Its weakening could further upset the balance in Georgian society, strengthening group-based tribalism and undermining the creation of a civic identity that transcends narrow ethnic, religious, and other group-based boundaries. All this will certainly further undermine Georgia’s societal resilience, the ability of Georgian society to cope with major crises and disruptions in an effective way.

4. Discussion

In this article we examined how the creeping radicalization of the GOC could undermine Georgia’s societal resilience. We identified two such mechanisms: the weakening of generalized social trust and the damage to the process of civic-national identity building through distancing from the idea of Georgia’s European integration. This can have long-term unintended consequences not only for Georgia’s foreign and domestic policy but also for the GOC itself, which require more exploration both from academic and policy perspectives.

Firstly, further drifting of the Church from the moderate middle ground could have a negative impact on domestic socio-political dynamics in the country. While the GOC acted previously as a mediator of last resort during times of political crisis, it has recently lost this function and has become more of a spoiler of the political process. From this perspective, the causal relationships between illiberal drift within the GOC and the dual process of party-led radicalization and societal polarization represent interesting avenues for future research.

The anti-liberal radicalization of the GOC could also have a negative impact on Georgia’s foreign policy. It could undermine support for European integration and strengthen pro-Russian attitudes among the radical-conservative section of the electorate. If the Church drifts further away from the process of European integration, it will be interesting to study how the conflicting pillars of national identity (Orthodox Christianity versus pro-Europeanness) could affect the electoral preferences of Georgia’s population.

Finally, the radicalization of the GOC may have an irreversible damaging impact on the Church itself. It can be assumed that the current unmatched popularity of the GOC depends to a large extent on the personality of Georgia’s long-serving Patriarch, Ilia II. However, the popularity of the GOC and the number of believers may erode after a transition of power. As Górecki (2020, p. 7) rightly argues, “[e]ach sub-sequent Catholicos-Patriarch, even if he turns out to be an excellent organizer and diplomat, will be a weaker leader than Ilia II.” Therefore, “it cannot be ruled out that it will be unable to maneuver as efficiently (both domestically and in the international arena) as it has done during Ilia II’s leadership” (Górecki 2020, p. 7). Should the new leadership abandon the skillful balancing approach practiced by Ilia II and firmly position the Church against Georgia’s European integration, this could strip from the GOC a significant share of the moderate believers and all of those who believe in the material or ideational benefits of Georgia’s European integration.

Overall, strong societal resilience in Georgia cannot be built by going against but only going with the GOC. For this to happen, a constructive contribution from the GOC is necessary. Despite its many flaws, the GOG remains the most reputable well-followed institution in the country. While it is not to be expected that the GOC will abandon its conservative position on a number of issues, it is important for the Church to reinvent itself as a pillar of stability, to tame its radical-conservative wing and return to its role as a societal balancer and mediator of last resort. This will help the Church to maintain its dominant position, while a silent revolution of changes in values (Inglehart 2015; Inglehart and Norris 2016) slowly takes place in Georgian society and the country, developing a more robust and inclusive societal resilience with the participation of all key societal actors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.; Methodology, B.L.; Software, B.L. and S.K.; Validation, B.L. and S.K.; Formal analysis, B.L. and S.K.; Investigation, B.L. and S.K.; Resources, B.L. and S.K.; Data curation, B.L.; Writing—original draft, B.L. and S.K.; Writing—review & editing, B.L. and S.K.; Visualization, B.L. and S.K.; Supervision, B.L.; Project administration, B.L.; Funding acquisition, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the EU Horizon 2020 project ‘De-Radicalisation in Europe and Beyond: Detect, Resolve, Re-integrate’ (Funding No. 959198), The Glasgow Caledonian University Cowcaddens Rd, Glasgow G4 0BA, United Kingdom.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A few articles touch upon the subject but their main focus is much broader than the resilience–religion nexus (cf. Kakachia et al. 2021). |

| 2 | As a rule, a new Patriarch is elected by the extended council of the Church from among three candidates picked by the Holy Synod, the ruling body of the GOC (OC Media 2017). |

| 3 | Orthodox Christianity and Europeanness are, of course, not the only markers of Georgia’s national identity. However, they are the most significant and all-inclusive categories with a capacity to accommodate all other identity-related aspects, such as history, culture, and traditions. The historical and cultural underpinnings of the GOC’s identity-forming role are obvious. The GOC played an “exceptional historical role (…) in the formation of Georgian statehood and the preservation of Georgian cultural and spiritual identity” (Gegeshidze and Mirziashvili 2021). On the other hand, Georgia’s European identity is too often linked to its history and culture. Georgia’s European integration is usually framed as the country’s return to a European family which has been a historic and cultural place for Georgia for centuries. The link between Georgia’s European identity, history, and culture is underlined in the country’s strategic documents. For instance, according to the National Security Concept of Georgia, “as a Black Sea and Southeast European country, Georgia is part of Europe geographically, politically, and culturally; yet it was cut off from its natural course of development by historical cataclysms” (MFA Georgia 2012, p. 15). The country’s recently adopted Foreign Policy Strategy also sees Georgia’s European integration as a “civilizational choice of Georgia” and “a matter of a broad societal consensus and guaranteed by constitution of Georgia” (MFA Georgia 2019, p. 4). |

| 4 | On permissive consensus and constraining dissensus, see Hooghe and Marks (2009). |

References

- Agenda.ge. 2014. Georgian Church Not Opposed to Country’s European Future. March 5. Available online: https://agenda.ge/en/news/2014/609 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Agenda.ge. 2016. Patriarch Ilia II Says Georgia Should Be Part of European Democratic Structures. February 11. Available online: https://agenda.ge/en/news/2016/359 (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Agenda.ge. 2022. Georgian Patriarch Ilia II Turns 89. January 4. Available online: https://agenda.ge/en/news/2022/18 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- AIVD. 2005. From Dawa to Jihad. The Various Threats from Radical Islam to the Democratic Legal Order. Available online: https://english.aivd.nl/publications/publications/2005/03/30/from-dawa-to-jihad (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Ashour, Omar. 2009. Votes and Violence: Islamists and the Processes of Transformation. International Centre for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence (ICSR). January 4. Available online: https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Votes-and-Violence_-Islamists-and-The-Processes-of-Transformation.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Babayev, Azar, and Kavus Abushov. 2022. The Azerbaijani Resilient Society: Explaining the Multifaceted Aspects of People’s Social Solidarity. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 35: 210–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. 2013. Thousands Protest in Georgia over Gay Rights Rally. May 17. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-22571216 (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Börzel, A. Tanja, and Thomas Risse. 2018. Conceptual Framework. Fostering Resilience in Areas of Limited Statehood and Contested Orders. EU-LISTCO Working Paper, No. 1. Available online: https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/handle/fub188/24759 (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Caucasus Barometer. 2019. Caucasus Barometer Time-Series Dataset Georgia. Available online: https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-ge/RELGION/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Chandler, David. 2015. Rethinking the Conflict-Poverty Nexus: From Securitising Intervention to Resilience. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, David, and Jon Coaffee. 2016. The Routledge Handbook of International Resilience. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, Robia. 2010. Religiosity and Trust in Religious Institutions: Tales from the South Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia). Politics and Religion 3: 228–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civil Georgia. 2008. Georgian Patriarch Calls on Opposition to Stop Hunger Strike. March 20. Available online: https://civil.ge/archives/114564 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Civil Georgia. 2014. Protest against the LGBT ‘Propaganda’ and “the Day of Family Purity” on 17 May (LGBT ‘Propagandis’ Tsinaagmdeg Akcia Da ‘Ojakhis Dge’ 17 Maiss). May 16. Available online: https://old.civil.ge/geo/article.php?id=28191?id=28191 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Civil Georgia. 2017. CSOs: PM Kvirikashvili’s Church Statements ‘Irresponsible’. July 26. Available online: http://www.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=30295 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Civil Georgia. 2021. Orthodox Metropolitan Claims EU, U.S. Embassies Force ‘Immorality’ on Georgia. July 12. Available online: https://civil.ge/archives/431749 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- EU Commission. 2017. A Strategic Approach to Resilience in the EU’s External Action. Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council: JOIN (2017) 21 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52017JC0021 (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Filetti, Andrea. 2013. Religion in South-Caucasus: Encouraging or Inhibiting pro-Democratic Attitudes? Religion and Society in Central and Eastern Europe 6: 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Forker, Diana, and Bidzina Lebanidze, eds. 2022. Ambitious Agenda–Limited Substance? Critical Examinations of the EU’s Resilience Turn in the South Caucasus. Caucasus Analytical Digest (CAD) 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavashelishvili, Elene. 2012. Anti-Modern and Anti-Globalist Tendencies in the Georgian Orthodox Church. Identity Studies in the Caucasus and the Black Sea Region 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gegeshidze, Archil, and Mikheil Mirziashvili. 2021. The Orthodox Church in Georgia’s Changing Society. July 23. Available online: https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/07/23/orthodox-church-in-georgia-s-changing-society-pub-85021 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Ghavtadze, Mariam, Eka Tchitanava, Mariam Jikia, Shota Tutberidze, and Gvanca Lomaia. 2020. Religiisa Da Rtsmenis Tavisufleba Sakartveloshi. Tbilisi: Tolerance and Diversity Institute. Available online: http://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdi-angarishi-religiis_tavisupleba_sakartveloshi_2010-2019.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Górecki, Wojciech. 2020. The Autumn of the (Georgian) Patriarch The Role of the Orthodox Church in Georgia and in Georgian Politics. OSW Commentary 332. Centre for Eastern Studies, May 18. Available online: https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2020-05-18/autumn-georgian-patriarch-role-orthodox-church-georgia-and (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Grove, Kevin. 2018. Resilience. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gugushvili, Alexi, Giorgi Babunashvili, Peter Kabachnik, Ana Kirvalidze, and Nino Rcheulishvili. 2015. Collective Memory, National Identity, and Contemporary Georgian Perspectives on Stalin and the Soviet Past. Tbilisi: Academic Swiss Caucasus Net (ASCN). [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. 2009. A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. British Journal of Political Science 39: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald. 2015. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2016. Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash. Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP16-026; Cambridge: Harvard Kennedy School. [Google Scholar]

- IRI. 2022. Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia. September. Available online: https://www.iri.org/resources/public-opinion-survey-residents-of-georgia-september-2022/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Jödicke, Ansgar, ed. 2017. Religion and Soft Power in the South Caucasus. Routledge Studies in Religion and Politics. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kakabadze, Shota. 2021. Trends of Radicalization in Georgia/3.2 Research Report. D.Rad Report Series on Trends of Radicalization. Tbilisi: Georgian Institute of Politics. Available online: https://dradproject.com/publications/trends-of-radicalisation-in-georgia/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Kakachia, Kornely. 2014. Is Georgia’s Orthodox Church an Obstacle to European Values? PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 322. Washington, DC: PONARS Eurasia. [Google Scholar]

- Kakachia, Kornely, Bidzina Lebanidze, and Salome Kandelaki. 2022. National Resilience Strategy for Georgia: Lessons from NATO, EU and Beyond. December 2. Available online: https://gip.ge/publication-post/national-resilience-strategy-for-georgia-lessons-from-nato-eu-and-beyond/ (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Kakachia, Kornely, Agnieszka Legucka, and Bidzina Lebanidze. 2021. Can the EU’s New Global Strategy Make a Difference? Strengthening Resilience in the Eastern Partnership Countries. Democratization 28: 1338–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandelaki, Salome, and Bidzina Lebanidze. 2022. From Top to Flop: Why Georgia Failed at Pandemic Resilience. Policy Paper No. 28. Tbilisi: Georgian Institute of Politics. [Google Scholar]

- Kundnani, Arun. 2012. Radicalisation: The Journey of a Concept. Race & Class 54: 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kviris Palitra. 2014. What Will Anti-Discriminatory Law Bring (Ras Mogvitans Antidiskriminaciuli Kanoni). May 5. Available online: http://www.kvirispalitra.ge/public/21570-ras-mogvitans-antidiskriminaciuli-kanoni.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Lavrelashvili, Teona. 2018. Resilience-Building in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine: Towards a Tailored Regional Approach from the EU. European View 17: 189–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebanidze, Bidzina, and Shota Kakabadze. 2021. Spoiler or Ambivalent Partner: The GOC and the Fate of Georgia’s European Future. July 26. Available online: https://gip.ge/spoiler-or-ambivalent-partner-the-goc-and-the-fate-of-georgias-european-future/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Menabde, Giorgi. 2019. The Battle for Political Influence in the Georgian Orthodox Church. The Jamestown Foundation, July 16. Available online: https://jamestown.org/program/the-battle-for-political-influence-in-the-georgian-orthodox-church/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Metreveli, Tornike. 2016. An Undisclosed Story of Roses: Church, State, and Nation in Contemporary Georgia. Nationalities Papers 44: 694–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MFA Georgia. 2012. National Security Concept of Georgia. Available online: https://mod.gov.ge/uploads/2018/pdf/NSC-ENG.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- MFA Georgia. 2019. 2019–2022 წლების საქართველოს საგარეო პოლიტიკის სტრატეგია [2019–2022 Foreign Policy Strategy of Georgia]. Available online: https://mfa.gov.ge/getattachment/MainNav/ForeignPolicy/ForeignPolicyStrategy/2019-2022-clebis-saqartvelos-sagareo-politikis-strategia.pdf.aspx (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Mikhelidze, Nona. 2018. EU Global Strategy, Resilience of the East European Societies and The Russian Challenge. In Geopolitics and Security: A New Strategy for the South Caucasus. Edited by Kornely Kakachia, Stefan Meister and Benjamin Fricke. Tbilisi: The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V, Tbilisi: The Georgian Institute of Politics, Tbilisi: The German Council on Foreign Relations, pp. 266–82. [Google Scholar]

- Minesashvili, Salome. 2015. Can the Georgian Orthodox Church Contribute to the Democratization Process? GIP Policy Paper. Tbilisi: Georgian Institute of Politics. [Google Scholar]

- Minesashvili, Salome. 2017. The Georgian Orthodox Church as a Civil Actor: Challenges and Capabilities. Policy Brief, No. 8. Tbilisi: Georgian Institute of Politics. [Google Scholar]

- Netgazeti. 2013. Ilia the Second: I Love Russia Very Much, Stalin Was a Believer (‘Ilia Meore: Ruseti Dzalian Miq’vars, St’alini Morts’mune Iq’o’). July 31. Available online: http://netgazeti.ge/news/24236/ (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- OC Media. 2017. Georgian Patriarch Names ‘Incumbent of the Patriarchal Throne’. November 23. Available online: https://oc-media.org/georgian-patriarch-names-incumbent-of-the-patriarchal-throne/ (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- OC Media. 2019a. Arrests in Tbilisi as Queer Rights Activists and Homophobic Counter Protesters Face-Off. June 14. Available online: https://oc-media.org/queer-rights-activists-confronted-by-conservative-groups-in-tbilisi/ (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- OC Media. 2019b. Georgian Government Allocates $320,000 for New Religious Holiday. May 10. Available online: https://oc-media.org/georgian-government-allocates-320-000-for-new-religious-holiday/ (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Sakartvelo da Msoflio. 2016. What Kind of Historical Choice Is Talk about, Which Georgian King Was Called the King of Europe?! (‘Romel Istoriul Archevanzea Saubari, Romel Kartvel Mefes Erkva Mefe Evropiswa?!’). Sakartvelo da Msoflio. July 6. Available online: http://geworld.ge/ge/8381/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Schmid, Alex P. 2013. Radicalisation, de-Radicalisation, Counter-Radicalisation: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review. ICCT Research Paper 97: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafutdinova, Gulnaz. 2014. The Pussy Riot Affair and Putin’s Démarche from Sovereign Democracy to Sovereign Morality. Nationalities Papers 42: 615–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollenwerk, Eric, Tanja A. Börzel, and Thomas Risse. 2021. Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU’s Neighbourhood: Introduction to the Special Issue. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Tabula. 2015. During the USSR, We Were Equal Republic, Now Not Even a State (‘SSRK-s Dros, Tanabaruflebiani Respublika Vikavit, Dghes Shtatic Ar Vart’). December 29. Available online: https://tabula.ge/ge/news/584945-gignadze-ssrk-s-dros-tanabaruplebiani-respublika (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Valiyev, Anar, and Fikrat Valehli. 2022. COVID-19 and Azerbaijan: Is the System Resilient Enough to Withstand the Perfect Storm? Problems of Post-Communism 69: 103–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOA. 2009. Georgian Orthodox Patriarch Mediating Crisis. October 27. Available online: https://www.voanews.com/a/a-13-2007-11-09-voa48-66526182/553664.html (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- World Values Survey Association. 2021. World Values Survey Wave 6 (2010–2014). Vienna: World Values Survey Association. [Google Scholar]

- Zedania, Giga. 2011. The Rise of Religious Nationalism in Georgia. Identity Studies in the Caucasus and the Black Sea Region 3: 120–28. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).