Abstract

The child is a trust from Allah and the ornament of the worldly life. In the early childhood period, which includes the preschool period, the child asks many questions, wants to understand everything around them, and shows an inexhaustible desire to learn. This research was carried out to examine the opinions of Qur’an course teachers about the religious and moral curiosity of preschool children. A qualitative method was used to ascertain the opinions of 40 participants in 2022. Six themes and 42 codes were determined from the answers provided by the participants to the questions in the semi-structured interview form. A content analysis method with a phenomenology design was used to analyze the data obtained in this study. It was found that children were intensely curious about the religious and moral issues of Allah, the Prophet, angels, death, heaven, hell and prayer; they can ask questions comfortably to satisfy their curiosity, and it was determined that they are excited when asking questions. It was found that teachers reacted positively to satisfy and expand children’s curiosity. In addition, we concluded that family and environmental learning are important factors that increase children’s curiosity, and activities such as drama, games and experiments conducted by teachers increase children’s curiosity.

1. Introduction

It is part of the innate nature of human beings to think, research and question. Thus, they wonder about and have the need to know many things (Demirel and Coşkun 2009). Curiosity is a mechanism that drives learning. In particular, children in early childhood are curious, turn to the things they are interested in, are amazed at each discovery, and constantly question reasons behind certain mechanisms (Hırimyan 2021). Therefore, childhood equals curiosity. Children learn best when they are curious (Engel 2011). Piaget drew attention to the importance of curiosity in children’s cognitive development, and Vygotsky explained that cognitive abilities could be expanded by encouraging childhood curiosity (Pluck and Johnson 2011).

It has been suggested that childhood—even early childhood—is an excellent time for religious preparation in the child, as children have a natural orientation towards religion, with the age of four being considered the golden age of interest in religious life (Selçuk 1991). What is expected from religious educators in this period is that children develop their innate sense of curiosity and have their questions answered at their developmental level. Failure to answer correctly and appropriately the questions asked by children as a manifestation of their sense of curiosity may cause children to show unhealthy religious growth in later stages (Tosun and Çapcıoğlu 2015).

The early childhood period, when children question everything, is when they are most open to learning. If the thinking styles of children can be understood at this stage, it can be ensured that they learn many things based on this (Ünverdi and Murat 2021). The present study examines the opinions of teachers working in the preschool period (4–6 age group) conducting Qur’an Courses affiliated with the Presidency of Religious Affairs in Türkiye regarding the curiosity and questions of children about religious and moral issues. This study will contribute to religious education and training activities applied in early childhood and will be an essential source for similar studies to be carried out in the future.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Curiosity and Learning Relationship

Curiosity is a real source of motivation for children to explore and learn about the outside world. It enables children to gain a wide range of knowledge, skills and experience. It also has an essential function in their cognitive, affective and psychomotor development (Silvia 2008). Learning that starts with curiosity is the main factor in effective and permanent learning because it involves structuring knowledge and executing cognitive processes, and thus reaches a deeper understanding (Loyens and Gijbels 2008; Jirout 2020). For this reason, in educational environments and activities, instead of presenting the information directly with formal methods such as expression, the aim is to actively gain information, such as learning by doing in line with the curiosity of the learner (Jirout et al. 2018). In addition, it is suggested that curiosity will positively affect the child’s general psychology by helping them to acquire positive social behaviors, such as social adaptation and social self-efficacy (Kashdan et al. 2013). Vygotsky emphasized the importance of social interaction, culture, and adult support with his socio-cultural theory; he advocated the idea that curiosity and exploration behavior can be reinforced and expanded with adult and peer support (Vygotsky 2004).

Children in early childhood are curious and surprised at each discovery and attract their parents’ attention by constantly asking questions. This situation sometimes causes parents to experience boredom and react. The questions that cause this situation to emerge are the main building blocks for the individual to make sense of their environment (Akyol et al. 2013). Since the driving force that makes us question and research is our curiosity, inquiries deriving from curiosity always start with a question (İnan 2013). Therefore, it is accepted as the beginning of learning that the child produces questions in their mind depending on their curiosity, and then asks them (Altıparmak 2019).

Children’s curiosity and questioning enable them to gain self-confidence in the learning process and to gain lifelong learning behavior, not only during school years (Yıldız et al. 2018). Depending on their curiosity, not answering the questions asked by children can negatively affect their learning process and desire in their developmental period and lifelong learning behaviors. Erikson (1959) stated, in his psycho-social development theory, that children during the stage of entrepreneurship versus guilt conduct research and examination because of their increasing curiosity. Accordingly, they ask many questions, and he emphasized that children may feel guilty if these questions are not answered appropriately (Can 2015).

2.2. Religious Education in Early Childhood

Early childhood is when the child’s future is shaped significantly, social and moral values are transferred, and the most essential knowledge and skills are acquired (Yavuzer 2010). Considering the meaning of the proverb “The tree bends when it is young”, it is seen that the preschool period is vital for the child’s education. A considerable part of the knowledge, skills, and behaviors that prepare children for their future life is learned during childhood, and these are very influential in forming their character structure and shaping their beliefs and value judgments (Köylü 2004). Early childhood is also a period in which the foundations of religious development are laid (Oruç 2014). The child’s interest in religion develops further with the influence of the environment they live in and their family (Dodurgalı 2010). Through this development, the child’s curiosity about the existence of Allah and their asking questions about Allah are considered indicators of the child’s religious development and positive progress in this sense (Cihandide 2014).

The first years of childhood, the beginning of early childhood, are also known as the period when the first religious inquiries begin, because early childhood is a period of discovery and curiosity at the highest level. Fowler states that the power of this stage, the beginning of the development of imagination, stems from the ability to have strong images and intuitive understanding (Fowler 1995). This stage provides an opportunity for faith development. The child in this period may ask many questions about the abstract concepts he hears from his family and surroundings. Parents and teachers who address these questions should answer them according to the child’s developmental level. Failure to answer these questions appropriately and correctly for the child’s development leads to unhealthy religious development in the child’s future life (Balbay 2021). In particular, if the child is in a fearful environment, this may limit the child’s ability to develop beliefs (Fowler 1995). According to Ibn Khaldun (2017), if the child’s questions are considered absurd, unnecessary, or sinful by his parents or teacher, the child’s sense of curiosity affects his religious development, which may be eroded. His self-confidence may be broken, and his desire to learn may decrease. In addition, if the child’s interest and curiosity in religion at this age are taken as an opportunity, and the child is overloaded with information through the use of easy believing and memorizing skills, this may cause the loss of natural belief in the child (Tosun and Çapcıoğlu 2015).

The issue that is more important than the content of the religious education provided to the child in early childhood is how this education is provided. In this period, carrying out activity-based educational activities that appeal to the child’s emotions is suggested, taking into account their mood and individual characteristics (Tosun and Yıldız 2019). In other words, indirect education is preferred instead of a direct religious education. In addition, since games, toys and children are complementary aspects, indirect education should be enriched by using the power of games and toys in the child’s religious education in this period (Tavukçuoğlu 2002). Extensive talking about the abstract principles of faith to children in this age group means making an effort that extends beyond their level of perception. Piaget stated that children’s cognitive development continues from simple to complex and develops in four stages; of these four stages, he defined the 2–7 age period as the pre-operational period. He divided this into two and named the ages of 2–4 the pre-conceptual period and the ages of 5–7 the intuitive period (Piaget 2002). Vygotsky argued that concept formation exceeds preschool children’s capacity and is possible only during adolescence (Vygotsky 1985). Therefore, subjects such as Allah, angels, and the afterlife, which are abstract topics, should be taught briefly, and not in detail.

Much of what children are taught at an early age concerns behavior. These examples, which correspond to the practical aspects of religion such as being clean, speaking correctly, and praying, show that it is more appropriate first to establish the behavior in the child and then move on to the search for meaning and teaching the principles of faith (Gazali 2004). Kohlberg conceptualized the development of moral thought as a growth and development process. It highlights the development of the ability to mimic a role model as the starting point of the child’s moral development in the preschool period, which he defined as dependent morality (Kohlberg 1969). At this stage, as the immediate vicinity of the child is provided by their parents and teachers, they must teach The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) as a role model, because the Qur’an says: “Indeed, in the Messenger of Allah you have an excellent example for whoever has hope in Allah and the Last Day, and remembers Allah often.” (Qur’an: Ahzab, 33/21). Therefore, children learn what they see and hear from their parents and their environment through imitation (Şenyayla 2021).

2.3. Purpose and Importance of the Research

Vygotsky stated that every child is born with a particular potential, but they can only achieve this potential with the help of the adults around them (Vygotsky 1978). Bronfenbrenner also stated, in his ecological system theory, that the relationships the child establishes with their immediate environment affect their development. Vergote (1978) also explained that the child’s fear and respect towards the sacred manifest his innate sense of religion and interest in faith. The person who will support the child’s interest and curiosity in theology, as well as their desire to know and their curiosity, and who will reveal this potential, are the teachers who offer them religious education during this period. Otherwise, a curriculum that does not trigger curiosity, an educational environment deprived of rich stimuli, and a teacher that does not support this ability will prevent the child from realizing their potential.

It is essential to know what knowledge the Qur’an course teachers, who have significant effects on developing children’s curiosity about religious and moral issues in the preschool period, have about children’s curiosity and what kind of activities they engage in. Therefore, it will be possible to learn about children’s curiosity and support their potential. Although children’s curiosity about religious and moral issues is significant in the process of religious education, there is no independent research on this subject in the literature. For this reason, this study, which was conducted to examine the views of Qur’an course teachers on children’s curiosity about religious and moral issues, will contribute to the literature on early childhood religious education.

The aim of the research is to examine the opinions of the Qur’an course teachers about the religious and moral curiosity of preschool children. The sub-aims of the study are: which activities and situations increase children’s curiosity; how do children display curiosity behaviors; what are the reactions of the Qur’an course teachers to the children’s curiosity and questions; which methods are preferred by Qur’an course teachers to increase the curiosity of children. The main reason for determining these sub-aims in the research is that we want to determine the attitudes and behaviors of teachers toward children who are curious by nature since all answers, attitudes, behaviors, reactions, and especially the education methods of teachers towards children’s questions, will either trigger or dull this curiosity.

3. Methods

A qualitative research method was adopted in this study. A phenomenological analysis was carried out to understand and interpret the research data. A phenomenological approach determines the shared ideas and opinions of the participants who have experience with a certain phenomenon (Patton 2018). The most important feature that distinguishes phenomenology from other approaches is that it is based on the assumption that “common experiences have the essence” (Yıldırım and Şimşek 2016). This research aims to determine the shared views and opinions of Qur’an course teachers with experience of preschool children’s religious and moral curiosity. In addition, the phenomenological method aims to find a universal description of an experience, which includes structural and textural components (Creswell 2021). In addition, phenomenology focuses on phenomena we are aware of, but of which we need a detailed and deep understanding (Yıldırım and Şimşek 2016). The phenomenology pattern used in this study was useful for examining children’s curiosity, of which we are aware but do not have in-depth knowledge.

Semi-structured interviews and a demographic scale were used as the data collection tools in this research. In the demographic information form, participants were asked about their age, educational status, seniority, student group, and the number of students they worked with. Before the semi-structured interview form was created, a literature review was conducted, and similar studies in preschool fields were also used. Then, the opinions of two Qur’an course teachers on the subject were taken. The semi-structured interview form, consisting of open-ended questions, was peer-reviewed by two experts who specialize in qualitative research. In the interview form, six open-ended questions were asked to the participants:

- What are the most common questions asked by children aged 4–6 on religious and moral issues?

- What situations increase the curiosity of children aged 4–6?

- What activities are 4–6-year-old children highly curious about?

- What are the opinions of Qur’an course teachers about the curiosity behaviors of children aged 4–6?

- What are the reactions of Qur’an course teachers to the questions and curiosity of children aged 4–6?

- What methods are preferred by Qur’an course teachers to increase the curiosity of children aged 4–6?

3.1. Study Group

While determining the study group of the research, criterion sampling, one of the purposive sampling methods, was preferred. Criterion sampling entails working with participants who fulfill the characteristics of predetermined criteria. The main point in the criterion sample is that the participants to be selected have sufficient information (Patton 2018). The research was carried out with 40 participants who volunteered and met the conditions, out of the 65 Qur’an course teachers working in the province of Çorum after obtaining ethical and institutional permission.

It was determined that 67.5% (n = 27) of the participants were in permanent employment and 32.5% (n = 13) were contracted. A total of 87.5% (n = 35) of the participants were married. It was revealed that most of the participants, who were all women, were simultaneously mothers and had a relatively ready infrastructure for their profession by taking care of and developing their own children at home. It was observed that 70% (n = 28) of the participants were between the ages of 36–45, 27.5% (n = 11) were between the ages of 26–35, and only one participant was over the age of 46. When the participants were examined in terms of years of working with children aged 4–6, 77.5% (n = 31) had been providing education to these children for 4–6 years; 10% (n = 4) had been providing education to these children for more than six years. A total of 12.5% (n = 5) had recently started this job (1–3 years). This situation reveals that the participants had specific experience in teaching religious education to children aged 4–6. It was observed that 30% (n = 12) of the participants had a two-year theology associate degree after high school, 15% (n = 6) had completed a four-year undergraduate education by studying Ilitam after an associate degree, 35% (n = 14) had graduated from the faculty of theology, and 20% (n = 8) were in postgraduate education. Regarding the certificate programs that the participants had attended on early childhood education, all of them improved themselves by training in various institutions before/after starting their work. In addition, 10% (n = 4) were graduates of the department of child development at the undergraduate level. Furthermore, 77.5% (n = 31) of the participants attended in-service training for the education of early-stage children organized by the institution they work for.

3.2. Analysis of Data

A content analysis method was used in the analysis of the data. Content analysis is a method that allows the data to be shaped in a particular way and with a particular system, depending on previously determined classifications. The primary purpose of content analysis is to reveal the concepts and connections that will explain the data obtained (Kızıltepe 2021). In this regard, the process applied in content analysis is to categorize the data that are similar within the framework of specific themes by coding, evaluating and interpreting them in a way that the reader can understand (Yıldırım and Şimşek 2016). In addition, in the analysis process of this research, the theoretical design of “data being descriptive in a phenomenological perspective, being in a phenomenological reduction and discovering basic meanings with the help of creative variations” (Giorgi 1997) was applied. MAXQDA 22.2.1 program developed by VERBI Software based in Berlin, Germany was used in the analysis of the data. Themes and codes were created through the MAXQDA program, the data obtained from the participants were transferred to the electronic environment, and the word frequencies in the text were determined and presented with visual tools. Thus, the data analysis was rendered more transparent and more systematic, and the results are more understandable with word clouds and graphics.

Four main strategies were used as the validity and reliability criteria of the qualitative findings: “credibility, reliability, transferability, and verifiability” (Yıldırım and Şimşek 2016). In this research, the following was conducted for credibility: The data collection tool was well structured, and an accurate research method was used. Maximum diversity was achieved due to attracting participants with different demographic characteristics. For reliability, we explained when and where the analysis was carried out. The demographic characteristics of the participants were presented and coded before their statements. In both cases, expert examination and evaluation were requested before proceeding to the research’s implementation and analysis phases. For transferability, the recording, note-taking and observation processes were carried out in a natural environment. Some of the findings analyzed are presented to the reader unchanged in the study. We avoided influencing the participants. To prevent the participants from reaching a consensus with the researcher, a semi-structured interview form was preferred.

4. Results

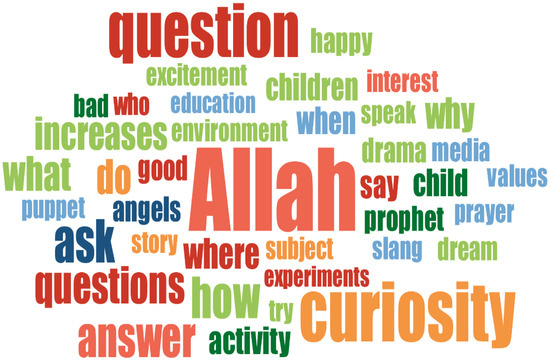

Themes and codes were created according to the answers provided by the participants to the six questions in the semi-structured interview form. In the qualitative analysis, firstly, a word cloud was formed from the opinions of the Qur’an course teachers about preschool children’s religious and moral curiosity. Then, based on the findings, six themes were created, code frequencies were assigned within the themes, and the participants’ opinions were presented. The word cloud formed by the most frequently repeated 40 words among the views of the Qur’an course teachers regarding the religious and moral curiosity of preschool children is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Word cloud consisting of participant views on preschool children’s curiosities on religious and moral issues.

From Figure 1, we can observe that the views of Qur’an course teachers about the curiosity of preschool children in religious and moral issues are generally positive. The most frequently repeated words in the participant’s views are “Allah, curiosity, question, ask, answer, why, where, what, how, who, when, increases, the Prophet, angels, excitement, prayer, happy, interest, drama, puppet, story, activity, good, values”, which are words that have positive connotations about curiosity. In addition, it is seen that words such as “slang, bad, environment, media” have negative connotations. However, not so positive words were also expressed by the participants.

4.1. Questions Asked by Preschool Children on Religious and Moral Issues

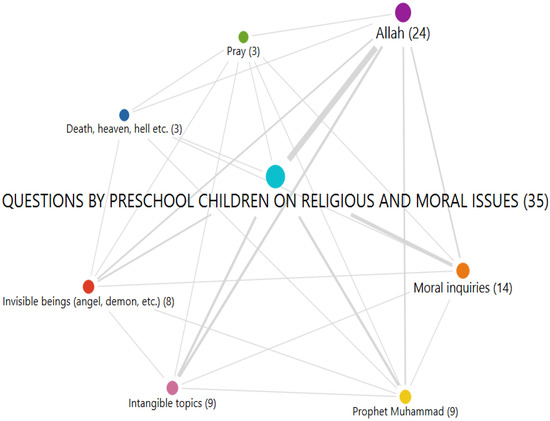

The first theme of the study was determined as the questions that preschool children ask the most about religious and moral issues. These questions are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Questions asked by preschool children on religious and moral issues.

As seen in Figure 2, seven codes were created for the questions asked by the children. When the participants’ opinions about the questions are analyzed, it is seen that all of these codes are related to each other. This relationship between codes shows that the children’s curiosity about one subject triggers their curiosity about other topics. Of these codes, the most frequently repeated and central questions asked about “Allah” were determined as the first code of this theme. Children mostly ask questions about Allah and want to recognize, know and understand him. The participants expressed the children’s questions on this subject as follows. P3: “How big is Allah?” P4: “Where is Allah?” P23: “How does Allah see everyone?” P26: “Why can’t we see Allah? Does Allah live in the clouds?” P26: “How does Allah fill his stomach? What does he eat? How can Allah create everything? Does Allah have siblings or children? Why is Allah invisible?” P37: “Is Allah in the mosque?” To these and similar questions of children, the teachers said that Allah’s existence could be understood by looking at his creations, as is mentioned in the literature. In other words, traces of Allah’s existence can be discerned in his creation, including flowers, insects, stars, planets, people and animals. However, it was stated that some of the children were not convinced by these answers and asked new questions, and even some of them evaluated these answers from very different perspectives. P30: “They are curious about Allah, and when we say that we can see him in a tree or a bird, they ask if He looks like a tree or a bird.” P22: “They ask where Allah is; they do not want to step on the ground when we say everywhere.” P16: When they ask ”Where is Allah” and we answer “Allah is within us”, they ask “Does he eat the food in our stomachs?”

The second code in this theme is named “moral inquiries”. When children see that the opposite to the moral values they learn in the course occurs in their environment, they question this. P1: “They ask us about the slang words he hears on the street, and they ask us, “Muslims don’t do that, right?” P8: “He asks us about his parents’ smoking as a bad behavior question.” P22: “They can ask questions about things such as taking unauthorized items and speaking slang.” The third code of this theme is “abstract topics”. Since preschool children are in the concrete operational stage due to their age, they are more curious about subjects, entities, and objects that seem abstract to them. In the same way, it is possible to evaluate other codes, such as “invisible beings (angel, devil, etc.)” and “death, heaven, hell”, about which children ask a lot of questions in this context. P3: “Generally, they don’t ask what they see; they ask about abstract topics.” P28: “They ask questions such as whether angels are girls or boys, or if they have wings, or if angels smell like chocolate.”P26: “Why is devil bad and the angels good? Why do people die? Do we disappear completely when we die? Is there a way to heaven too, how can we get there?”.

Another subject that children ask questions and want to learn about is The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). They want to learn about the different characteristics of The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). P17: “They are very curious about the Prophet; they ask about his body characteristics, they ask where he is now.” P22: “When will we visit the Prophet?” P23: “Are Allah and the Prophet brothers?” The last code in this theme is children’s questions and curiosity about prayer. Children wonder how their prayers reach Allah, and they question whether their prayers are accepted or not. P4: “The child was praying for his parents to take a dog home and asked why his prayer did not to work.” P26: “A child who always wants to play with a toy he loves in the course and prays for it asks why his prayer was not accepted.” In particular, a teacher stated that he approached the child in such situations with the following answer: “I wonder if your friends might have said the same prayer? And could Allah have answered the prayers in turn?”.

4.2. Situations That Increase the Curiosity of Preschool Children

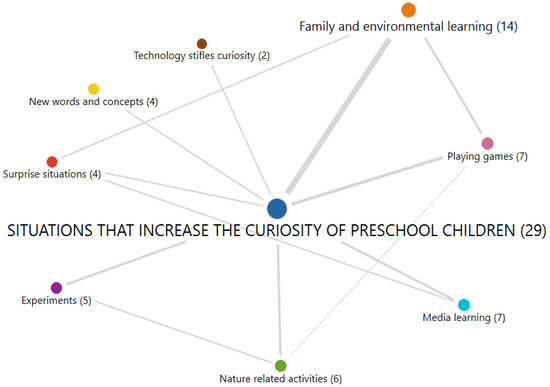

The second theme of the study was determined as situations that increase the curiosity of preschool children. These questions are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Situations that increase the curiosity of preschool children.

As can be seen in Figure 3, eight codes were created for situations that increase children’s curiosity. When the participants’ opinions are analyzed, it is seen that a significant part of these codes is related to each other. Seven codes can be described as positive and one as negative (not raising curiosity, but decreasing curiosity). In particular, the relationship between playing games and family learning, nature activities, and experiments is that the child perceives experiments as games and asks and learns during this fun activity. Thus, it can be interpreted that the games and travel activities in the family also increase their curiosity. The “Family and environmental learning” title, which is the most repeated and prominent among the codes, was determined as the first code of this theme. P1: “Parents always talk about death, heaven, and hell in their speeches. And this comes back to us as a question and curiosity.” P3: “Subjects such as visiting a cemetery, the crying of parents and condolences, increase their curiosity.” P28: “They learn about bad things from the environment such as ‘Allah will turn us into stone’, and so we try to fix them.” In particular, the wrong learning about religious and moral issues expressed by the last participant negatively affects the mind and heart of the child. At this point, religious educators have more work. The code titled media learning can also be evaluated in this context. Media influence seems to be an essential factor that increases the child’s curiosity. P7: “The things they watch on the internet scare them, they tell them, and they ask about them.” P24: “Cartoons influence them in this regard.”

Playing games, performing experiments, and participating in activities with nature have been identified as essential elements in increasing the child’s curiosity. Especially considering the relationship between them, it should be taken into consideration in keeping the child’s religious and moral curiosity alive. P31: “When there are activities such as finger painting, watercolor, puppetry, play, and drama, their curiosity increases.” P40: “The Salavat activity is exciting and effective for them; while doing it, they are happy and enthusiastic with games and fun, and then they ask questions.” P18: “We go through plants and animals; this increases their curiosity. I brought different plants to class, and we talked about them. We talked about their color, growth, variety, scent, and thorns, and then they asked questions about plants and animals.” New words and concepts children hear and surprise situations are essential factors in increasing their curiosity. P27: “When we say we have a surprise, when we say that we will hold celebrations and similar events, this makes them curious and excited.” The only code with negative connotations in this theme is that learning through technology reduces the child’s curiosity. Participants said that the information children reach through the television and the internet reduces their willingness to learn new information and ask questions. P22: “They were not very impressed by the bean experiments. Because they had learned this information through other channels, this situation partially kills their curiosity.”.

4.3. Curiosity Behaviors of Preschool Children

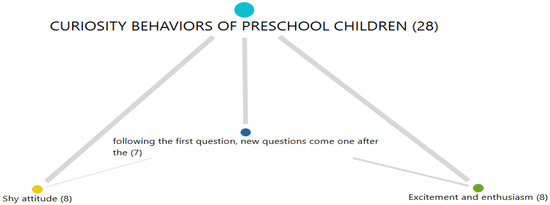

The third theme of the research is the curiosity behaviors of preschool children. In other words, they are the behaviors and attitudes they display when they are curious and want to ask questions. Children’s curiosity behaviors are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Curiosity behaviors of preschool children.

When the curiosity behaviors of the children were examined, it was determined that “excitement and enthusiasm” and “shy attitude” had the same frequency value. Both seem to be related to the code of “following the first question, new questions come one after the other”. This situation shows that, although the children’s excitement, enthusiasm, and shyness are close to each other, almost all of the children ask similar and different questions to the teachers after the first question is asked in the classroom environment. P6: “They run towards us with excitement; their eyes get bigger.” P12: “They can’t stay still.” P17: “They fidget and get excited.” P40: “He asks questions with enthusiasm, and when someone asks, the others get excited and bring the continuation of those questions.” P29: “Sometimes they are hesitant to ask questions, they are afraid of being ridiculed.” P40: “At first, they may hesitate to ask questions, but then they ask questions as they get used to it.” P34: “When a friend asks a question, others ask similar questions. Asking questions also helps shy students who never talk to gain self-confidence in this way.”.

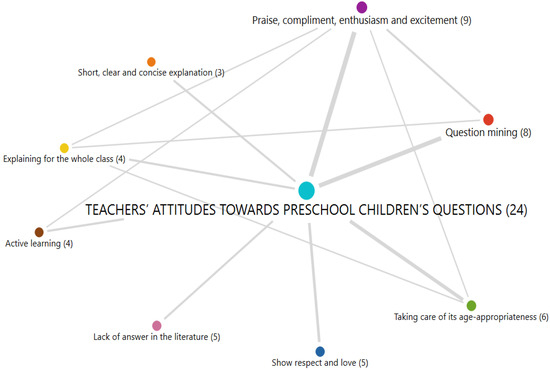

4.4. Teachers’ Attitudes towards Preschool Children’s Questions

The fourth theme of the research is the teachers’ attitudes toward the questions of preschool children. In this theme, when children ask questions, we try to find answers to the questions “how do the teachers react to these questions, how do they answer them, how do they carry out the process”. The teachers’ attitudes toward the children’s questions are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Attitudes of teachers to preschool children’s questions.

In Figure 5, it is seen that a positive attitude is adopted when the instructive attitudes of the children towards their questions are examined. Eight codes were created within this theme. It was determined that there are connections between the participants’ opinions based on these codes. With the “question mining” and “active learning” of the “praise, compliment, enthusiasm, and excitement” code, it is significant that “explaining for the whole class” is also related to “taking care of its age-appropriateness”, because the teacher’s praise, compliments, and enthusiasm in the face of children’s questions contribute to the children asking new questions and realizing active learning in the classroom. In addition, after a child’s question, the teacher explains to the entire class according to the ages and levels of the children, creating a rich learning environment that all children benefit from. P1: “There is a super question; we encourage it by applauding.” P12: “We are jumping with them.” P24: “We try to respond with the same enthusiasm.” P34: “I also answer in a high tone as a great question. I answer his question by making gestures such as the positive hand sign, High five.”.

The teachers stated that they conduct question mining to increase children’s curiosity and awareness of religious and moral issues; that is, they encourage them to think, empathize, and ask questions. P22: “Sometimes I answer a question with a question to make them think. I answer the child who asks if Allah has a hand, do you think it exists? I say to the boy who asks about heaven, how do you imagine heaven? And I make him dream.” P23: “Questions such as “what would happen if was all flowers were only one-color? What would it be like if our nose was on the back of our heads? Raise their curiosity. Brainstorming and a good question increases their curiosity.” Two of the interrelated codes in this theme are that the teachers provide age-appropriate answers and explanations for the entire class. P22: “We are trying to go from the glass to the building, and then to the master, and from there to the existence of the universe and connect everything to the creator.” P7: “It would be wrong to say that there is everything in heaven, this time, they want to die; we do not want to go into those matters.” P8: “Witnessing death around them makes them wonder; I try to change the subject because it is not suitable for their age.” P12: “When a question comes, I don’t answer it immediately. I also receive other questions on the same subject; I expect everyone to meet at a common point and to gather their interests.”.

The teachers stated that they explain the questions to the children straightforwardly and transparently, according to their level. Still, they emphasized that the available information in the literature was insufficient in the face of some queries and that children’s specific answers should be developed for these questions. Other codes in this theme are “short, clear and clear explanation” and “lack of answer in the literature.” P31: “We need to give clear, short, and clear answers to the questions; they get bored when we extend it.” P8: “When we say “Allah is everywhere,” children are afraid even when they go to the toilet; this answer profoundly affects them. How shall we explain?” P30: “Taste, being happy, feeling pain, etc. when we tried to explain the existence of Allah with answers and experiments, some students, who were not satisfied with these answers, said, “Where is Allah? Why is nobody answering?” P16: “When I answered the question “Who created devil” as “Allah created,” I saw that there was a great fear in the eyes of the children.”.

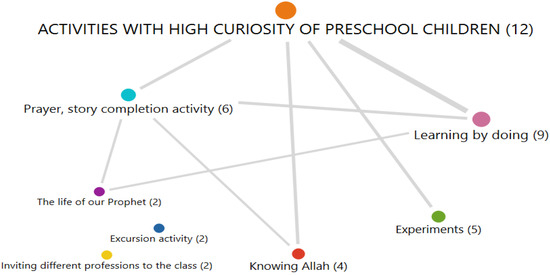

4.5. Activities Creating High Curiosity in Preschool Children

The fifth theme of the research is the activities in which the curiosity of preschool children is high. Seven codes, mostly related to each other, were identified in this theme. In particular, activities based on practice and learning by doing come to the fore. Activities in which the children’s curiosity is high are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Activities in which the preschool children’s curiosity is high.

In Figure 6, the most frequently repeated code among the activities in which children’s curiosity is high is “learning by doing”. It has been stated that the relationship between this code and the codes of “prayer, story completion activity”, “The life of our Prophet,” and “Knowing Allah” stems from activities such as reciting and completing prayers in chorus on these subjects, and doing Salawat together while providing religious education. P8: “Competitions, experiments, riddles, prayer flowers, patience necklaces, boat fasting, etc., are events which increase their curiosity.” P3: “They learn by doing and living; they become cleaning hunters, germ hunting activity...” P2: “Questions come at the end of the stories; their curiosity increases when we ask for some stories to be completed.” P32: “The activity of reading a part of the surah and completing the rest increases their curiosity.” P22: “When we put a mirror in a box and then do an activity, saying that there is the person whom Allah loves most in the mirror, their curiosity increases and they start to ask questions.”.

It has been determined that children’s curiosity is high in activities independent of each other within this theme. These codes include “experiments, excursions and calling occupational groups to the classroom environment”. These codes are activities based on practice in which students actively participate. P26: “They love experiments; I try to answer the questions in this way. Telescope, etc. I use tools. This is how I try to explain the existence of Allah.” P3: “It is effective to examine small creatures such as ants with the lens, they are cautious and ask questions.” P2: “Questions come at the end of the stories; their curiosity increases when we ask for some stories to be completed.” P27: “We did a bean seed experiment, observing the process of growing beans from a seed increases their curiosity.” P12: “We invited a chemist to the course; it was exciting.” P37: “Effectively, different people come to the class. It is very effective if a healthcare professional or a different teacher who can act out a story comes into the classroom.”.

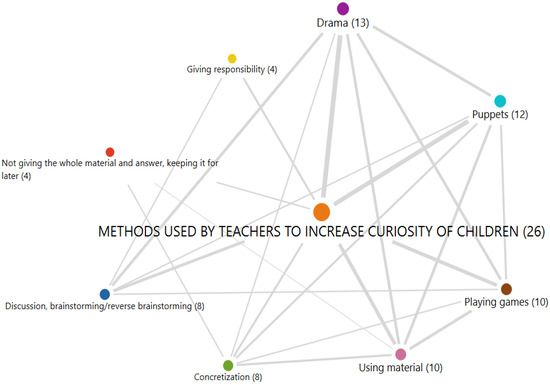

4.6. Methods Used by Teachers to Increase the Curiosity of Preschool Children

The sixth theme of the research is the methods used by the teachers to increase the curiosity of preschool children. This theme investigates which methods the teachers preferred to improve students’ interest and curiosity in religious and moral issues and encourage them to ask questions. In this context, eight codes, mostly related to each other, were created in line with the participants’ opinions. The methods used by the teachers to increase the curiosity of children are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Methods used by teachers to increase the curiosity of preschool children.

As seen in Figure 7, the most preferred method by teachers to increase children’s curiosity is the “drama” method. In connection with this, “puppets, games and materials” are among the most preferred tools. P16: “While teaching the Rabbena prayers, we both read the prayers and show the meaning of the prayer by using body language.” P34: “When I walk with a limp during the disability week, they are more curious and ask questions.” P27: “Methods such as drama, storytelling, puppets, teaching with games, and chair snatching increase their curiosity.” P14: “When I act as a ventriloquist and use the baby doll in prayer and surah lessons, it makes children more curious.” P26: “I use the puppet; we deal with the subject with the wise owl, and they ask him questions.” In particular, setting aside time for children to ask direct questions and planning an activity for this are among the remarkable findings of the research. P26: “We are doing question box and question envelope applications. There are more question-and-answer apps in these free times.”.

Other methods that teachers prefer to increase children’s curiosity are “discussion, brainstorming/reverse brainstorming”, “giving responsibility,” and “not giving the whole material and answer, keeping it for later”. The teachers stated that they create a more effective educational environment when they ask students for their ideas, give responsibility, and provide some answers to the questions to keep interest and curiosity alive and save some for later. P6: “We arouse curiosity by making the opposite of a moral value -if it’s not too absurd, for example, cleaning. We teach by seeing and discussing the consequences of polluting the environment.” P23: “We have empathized, what would you do if it were you, what would happen if there was only one color of the flower, what would it be like if our nose was on the back, etc.” P27: “Sometimes I say I should think about this question for a bit. The child doesn’t forget his question anyway; when he says you asked this question, he immediately remembers and listens to my answer with interest.”.

5. Discussion

Considering that the most frequently repeated words in this study are the words that have positive connotations, such as “Allah, curiosity, question, answer, excitement, happiness, good”, it can be said that children can ask questions, and they are excited and happy when asking them. This is an essential and positive result from the Qur’an courses and teachers providing education to children aged 4–6. Because it is understood from the questions that children frequently ask during this period that their interest in religion peaks at the age of 4–5, it is during this period when the child’s interest and curiosity in religious matters are high; if this interest is not fed and healthy guidance is not provided, the child’s religious interest and desire to learn may decrease and even turn into an attitude of denial towards religion (Tavukçuoğlu 2002). Finding their questions difficult or unnecessary, ignoring them, changing the subject, or silencing them will inhibit children’s desire to learn (Mehmedoğlu 2005). When the child asks questions, the child’s sense of curiosity and attempts to discover must not be turned into a feeling of guilt with negative attitudes. On the contrary, it is essential to encourage the child to ask new and exciting questions with positive attitudes (Heinelt 2003).

The study determined that children’s most frequently asked questions focused on abstract subjects, such as Allah, the Prophet, prayer, invisible beings, death, heaven and hell. In a similar study, it was revealed that the most frequently asked questions by children were questions about the essence and qualities of Allah and the questions that would define the human qualities of the Prophet (Yağcı 2018). In this study, the teachers provided examples of flowers, insects, human bodies, and the universe to the children’s questions about Allah. Although the teachers’ answers that Allah’s existence can be understood by seeing the traces of the act of creation satisfied some students, they did not help others. Therefore, some children have explanation-seeking curiosity, and they do not find the answer sufficient and expect more detailed explanations. These findings revealed a new result that differs from the established literature’s current view that the preschool period is too early to create a concept. In addition, it was determined that the children of this period had difficulty comprehending the expression “Allah is everywhere”, and this knowledge caused them anxiety. Concepts that children are curious about are abstract concepts, such as Allah, the Prophet, heaven, angel, the afterlife and death. Since the mental world of children is not at a level to comprehend these concepts, it is essential to provide enough information to satisfy their curiosity but not to cause confusion in their minds (Doğan and Ege 2012).

Hull (1991) stated that, even if they are in the concrete stage, children participate in conversations about God in line with their level, they make curious attempts to understand God, and often ask questions. The development of the concept of God differs according to age groups in early childhood. However, 3–4-year-olds live in an egocentric world; they cannot see things from other perspectives. Accordingly, God is only their creator in the first place. At the ages of 4 and 5, children tend to ask more questions about God (Yavuz 1983). However, since these children have not yet developed abstract thinking skills, they tend to think of God as someone with a natural body and human feelings. When children reach the ages of 6 and 7, their imagination of God shows anthropomorphic features (Tamminen et al. 2007). It is usual for the child to ask questions about Allah and to imagine Allah having anthropomorphic (identifying Allah with human factors) features in the preschool period (Balbay 2021). Because children are in special preparation for believing in Allah in this period when their curiosity and religious feelings are the most intense (Yavuz 1983), metaphors and similes are essential aids in preschool education. In various studies, it has been observed that children better understand some abstract subjects through metaphors (Kara 2019; Tanık-Önal and Kızılay 2021). Children need help and guidance on the concept of Allah. It would be a correct approach in terms of religious development to focus on his creations rather than abstract narratives about the relationship of events in the universe with Allah and the role of Allah (Selçuk 1991).

One of the topics that children frequently ask about is death, heaven and hell. Children often start to ask questions about death, especially between the ages of 4–6 (Goldman 2009), mostly because of death cases in and around their family or condolence visits, situations that trigger the child’s curiosity about this issue after explaining to the children that death develops as a natural process due to illness, accident or old age. Considering that the age factor is the most critical in perceiving the event of death (Mahon et al. 1999), it is natural that death, which is an entirely abstract concept with features such as finitude, universality, and inevitability (Köylü 2004), is perceived differently according to age groups. While death in children aged 3–5 is perceived as sleep and traveling to a distant place (Nagy 1965), children from the age of five gradually begin to understand that death is a final, universal, and inevitable phenomenon (Mishara 1999). Towards the end of the age of eight, children start to think that their parents will die one day (Vianello et al. 1992). The education about death provided to them is essential to how children perceive death. Of course, the clergy and teachers have a crucial role in the education about death. Köylü and Oruç (2017) state that it would be beneficial to associate the answers to be provided on these issues with moral education. This concept, expressed as the awareness of the afterlife in Islamic sources, has been considered a moral element and value in religious education and described as “shaping behavior by belief” (Gürer 2020). In other words, the event of death should not be considered as glorifying the deceased and bringing them to heaven, but as an opportunity to present moral principles within the framework of the child’s mental health (Köylü and Oruç 2017). Praising heaven as “the deceased go to heaven”, as if they died solely to go there, does not provide sufficient information to the child (Kara 2019).

The study also determined that the children made moral inquiries and asked teachers questions in this direction. When children see that the opposite of the moral values they learned in the course are done around them, they question this. Whether morality and values can be taught to children as knowledge is a topic that has always been considered. According to Windmiller (1980), values cannot be directly instilled; however, essential cognitive organizations develop correctly if opportunities are created for children to see inconsistencies and conflicts in newly formed ideas during their growing up period. This organization and learning orientation in the child’s mental structure initiates the progress in moral development. Another issue that preschool children wonder about is prayer. Children wonder how their prayers reach Allah, and they question whether their prayers are accepted or not.

The situations that increase children’s curiosity were determined to be playing games, media learning, nature-related activities, experiments, and surprise situations followed. Religious awakening and religious feelings in preschool children are activated depending on the family factor. The religious behavior of the child in the family environment feeds the child’s curiosity and interest in religious issues (Cihandide 2014). Considering the relationships between the situations that increase children’s curiosity, the child perceives experiments as games and asks and learns during this fun activity; it can be said that the games and excursions in the family also increase their curiosity. Fusaro and Smith (2018) also stated that preschool children use scientific inquiry skills, such as observation and experiments, to seek and discover information. Çelebi et al. (2016), in their research on preschool children’s views on religious education, stated that children especially learn through activities and enjoy it very much. They explained that children having fun during the religious education process contributes to the flow of quality education. Science-nature activities, such as mountains, seas, various animals and plants, sky, and space, which attract children’s attention, should be used primarily to make them feel the presence of Allah because nature is an excellent source of religious education (Kara 2019).

When what the children did and how they behaved when they were curious about something is examined, the participants’ views were coded as “excitement and enthusiasm” and “shy attitude”. Considering that these two views are related to the code of “following the first question one after the other”, it can be interpreted that almost all of the children—whether they are self-confident or shy—posed similar and different questions to the teachers after the first question was asked in the classroom. When the teachers’ responses to the children’s questions and curiosity behaviors were examined, it was determined that the findings were positive. The participants stated that they met the children’s questions with praise, compliments, enthusiasm and excitement; they tried to learn similar and different questions on the same topic by conducting question mining; they explained topics to the entire class with an active learning method; they stated that they paid attention to the age appropriateness of their answers. In a study on the religious education of preschool children, under the heading of pedagogical methods used by teachers in response to questions asked, attention was drawn to the importance of teachers being able to reach the level children can understand (Kara 2019). In the literature, it is expressed that providing appropriate answers to the development and understanding of children, taking into account the individual differences between them, takes into account their current conditions. It is even stated that it may be necessary to provide different answers to different children who ask the same question (Selçuk 1991).

When we look at the activities in which children’s curiosity is high, actions based on practice and learning by doing come to the fore. The activities that increase children’s curiosity were prayer and story completion, experiments, excursions, inviting guests to the class, etc. It has been stated that activities, such as reciting and completing prayers in chorus and doing Salawat together, increase the interest and curiosity of the students, especially while providing religious education on subjects such as “The life of our Prophet” and “Knowing Allah”. Vergote (1978) showed signs of socialization by moving and raising their hands when worshiping and praying. Prayer is not only a religious activity, but also a relationship. The child’s social environment either encourages or hinders this relationship and religious development. In this regard, the effects of the family, temple, and religious education are supportive (Paloutzian 1996).

To increase the interest and curiosity of children in religious and moral issues and to encourage them to ask questions, the most preferred method by the teachers is the drama method. In connection with this, “puppets, games, and materials” were among the most preferred tools. Learning through play is an integral part of preschool education. Therefore, the play method effectively activates and supports children’s curiosity (Vardi and Demiriz 2019). The preschool period is a period in which play is life itself, and in this period, play is not just an activity for the child but a basic need similar to eating and drinking (Balbay 2021). Various studies show that children’s curiosity increases when new/different activities, methods, and materials are used (Cecil et al. 1985; Vardi and Demiriz 2019). It is accepted that activities, such as effective storytelling, animating religious stories, role-playing, using puppets, memorizing religious texts, making imitations, playing games, and performing art activities, which are applied by their developmental level to develop children’s spiritual imagination, enrich the religious development of children (Ratcliff and Ratcliff 2010).

In addition, in some courses, allocating time for children to ask questions directly and planning an activity “question box” and “question envelope” are among the remarkable findings of the research. Beaty (1988) also drew attention to the importance of preparing educational environments where preschool children can use their curiosity instincts, establish cause–effect relationships, and make predictions since they are curious, extremely willing to research, and have strong imaginations. Answers are important, but questions are more important. The child’s questioning behavior indicates the child’s pursuits and learning curiosity. Suppose the teacher who provides religious education to the child in this period feeds the child’s question sources. In that case, they can reveal the clues about the religious perception created in the child’s mind and illuminate the child’s path (Kara 2019).

Other methods that teachers prefer to use to increase children’s curiosity are “discussion, brainstorming/reverse brainstorming”, “giving responsibility”, and “not giving the whole material and answer, keeping it for later”. The findings point to a relationship between curiosity and children’s question-asking ability. Pluck and Johnson (2011) recommended that teachers trigger children’s curiosity by confronting them with thought-provoking questions. Teachers stated that they create a more effective educational environment when they ask students for their opinions and give responsibility. In addition, one of the methods used by the teachers is that sometimes they do not answer all of the children’s questions and leave some of them for a later time. In this way, the teachers said they wanted to increase the interest and curiosity of the children. The ideal level of uncertainty and curiosity the teacher provides during education can make the students more interested in the subjects (Lamnina and Chase 2019).

6. Conclusions

In this study, which was conducted to examine the views of Qur’an course teachers on the religious and moral curiosity of preschool children, interviews were conducted with 40 participants using a qualitative method. In the sub-dimensions of the research, we included the questions asked by preschool children about religious and moral issues; the situations that arouse their curiosity; activities that increase the children’s curiosity; the children’s curiosity behaviors; the reactions of the Qur’an course teachers about the children’s curiosity and questions; and the methods the Qur’an course teachers prefer to use to increase the curiosity of children. As a result of the findings obtained from the participants, six themes and a total of 42 codes were identified within these themes. In the findings section, the relationships between the codes were shown using code maps, and the participants’ opinions were quoted and analyzed in depth.

The first finding is that the most repeated words within the teachers’ answers to the interviews were “Allah, curiosity, question, answer, excitement, happy”. These words, which have positive associations, show that students can ask questions in the learning environment and are excited and happy when asking questions. It was found that preschool children are intensely curious about Allah, the Prophet, invisible beings (angels, devil, etc.), the afterlife (death, heaven, hell, etc.), and prayer; they can ask questions comfortably to satisfy their curiosity. These results show that students have a much greater interest in questions that can be considered theological rather than moral or behavioral. Research findings contain exciting results in this sense. It was determined that they were excited and happy when asking questions and that their teachers reacted positively to satisfy and expand children’s curiosity. In addition, it was concluded that family and media learning are important factors that increase children’s curiosity. Activities such as drama, games, and teacher experiments increase children’s curiosity.

Considering that most of the 4–6-year-old Qur’an course teachers are graduates of the Faculty of Theology, it can be seen that the sense of curiosity is a skill that needs to be developed, supported, renewed and nurtured in the courses they undertake during their undergraduate education. Therefore, to create this feeling, the teacher candidates should ensure they receive training in the undergraduate curriculum regarding the issues they should pay attention to and the strategies they can apply. Qur’an course teachers, who are influential in determining and developing children’s curiosity, can be made aware of the importance of children’s curiosity in in-service training. Training can be provided that will enable children to raise and support their curiosity in their activities, methods, materials and attitudes in the learning environment. This research has a specific limitation as it was carried out only with Qur’an course teachers in Çorum. Future studies with larger samples may be beneficial in terms of higher generalization levels. In addition, the study group of this research consisted only of teachers. By considering the opinions of children and their families, children’s curiosities can be determined more deeply.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted with the permission of Hitit University Non-Interventional Research Ethics Committee, decree no: 2022/148, 7 June 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before participating in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Akyol, Hayati, Kasım Yıldırım, Seyit Ateş, and Çetin Çetinkaya. 2013. What kinds of questions do we ask for making meaning? Mersin University Journal of The Faculty of Education 9: 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Altıparmak, İrem Günhan. 2019. The Role and Significance of Curiosity in Philosophy for Children. Master’s dissertation, University of Boğaziçi, İstanbul, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Balbay, Emine. 2021. Analyzing abstract conceptual activity examples in preschool religious education. Mecmua-International Journal of Social Sciences 12: 118–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaty, Janice. 1988. Skills for Preschool Teachers. Columbus: Merrill. [Google Scholar]

- Can, Gürhan. 2015. Kişilik Gelişimi. In Eğitim Psikolojisi, Gelişim-Öğrenme-Öğretim, 13th ed. Edited by Binnur Yeşilyaprak. Ankara: Pegem Publishing, pp. 125–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cecil, Lisa Mack, Mary McPhail Gray, Kathy R. Thornburg, and Jean Ispa. 1985. Curiosity exploration play creativity: The early childhood mosaic. Early Child Development and Care 19: 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihandide, Zeynep Nezahat. 2014. Okul Öncesi Din ve Ahlak Eğitimi. İstanbul: Dem Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W. 2021. Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri. Translated by Mesut Bütün, and Selçuk Beşir Demir. Ankara: Siyasal Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Çelebi, Kübra, Merve Şahin, Neslihan Bütün, and Suat Kol. 2016. Preschool children’s opinions towards theology. Kastamonu Education Journal 24: 2279–92. [Google Scholar]

- Demirel, Melek, and Yelkin Diker Coşkun. 2009. Investigation of curiosity levels of university students in terms of some variables. Mehmet Akif Ersoy University Journal of Education Faculty 18: 111–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dodurgalı, Abdurrahman. 2010. Ailede Din Eğitimi. İstanbul: Timaş Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Doğan, Recai, and Remziye Ege. 2012. Din Eğitimi. Ankara: Grafiker Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, Susan. 2011. Children’s need to know: Curiosity in schools. Harvard Educational Review 81: 625–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Erik. 1959. Identity and The Life Cycle. New York: Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, James W. 1995. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and The Quest for Meaning. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Fusaro, Maria, and Maureen C. Smith. 2018. Preschoolers’ inquisitiveness and science-relevant problem solving. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 42: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazali, Ebul Hamid Muhammed. 2004. Ihyau Ulumi’d-Din. Prepared by Sayyid Imran. Cairo: Daru’l-Hadis Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Amedeo. 1997. The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. Journal of Phemomenological Psychology 28: 235–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, Linda. 2009. Great Answers to Dıffıcult Questions about Death, What Children Need to Know. London and Philadelphia: Jessıca Kingsley Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gürer, Banu. 2020. Din Eğitimi ve Öğretimi Açısından Ahiret Bilinci. İstanbul: Çamlıca Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Heinelt, Gottfried. 2003. Psychological basis of child’s development in preschool period. Translated by Şuayip Özdemir. Journal of Academic Researches in Religious Sciences 3: 209–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hırimyan, Melis. 2021. Examination of Curiosity Statements of 9–12 Years Old Students in Context of Content, Expression and Obstacles. Master’s dissertation, University of Bahçeşehir, İstanbul. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, John M. 1991. God-Talk with Young Children: Notes for Parents and Teachers. Birmingham: Credar. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Khaldun, Ebû Zeyd Veliyyüddin Abdurrahman b. Muhammed. 2017. Mukaddime. Prepared by Süleyman Uludağ. İstanbul: Dergâh Publications. [Google Scholar]

- İnan, Ilhan. 2013. The Philosophy of Curiosity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jirout, Jamie J. 2020. Supporting early scientific thinking through curiosity. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirout, Jamie J., Virginia E. Vitiello, and Sharon K. Zumbrunn. 2018. Curiosity in Schools. In The New Science of Curiosity. İsrail: Nova, pp. 243–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, Büşra. 2019. Pedagogical Competencies of Educators/Religious Officials Who Take Part in Religious Education of Preschool Children (4–6 Age Group). Master’s dissertation, University of Uludağ, Bursa, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, Todd B., Ryne A. Sherman, Jessica Yarbro, and David C. Funder. 2013. How are curious people viewed and how do they behave in social situations? From the perspectives of self, friends, parents, and unacquainted observers. Journal of Personality 81: 142–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kızıltepe, Zeynep. 2021. İçerik Analizi Nedir? Nasıl Oluşmuştur? In Nitel Araştırma Yöntem, Teknik, Analiz ve Yaklaşımları. Edited by Fatma Nevra Seggie and Yasemin Bayyurt. Ankara: Anı Publications, pp. 253–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1969. Stage and Sequence: The Cognitive Developmental Approach to Socialization. In Handbook of Socialization Theory and Research. Edited by David A. Goslin. Chicago: Rand McNally, pp. 347–480. [Google Scholar]

- Köylü, Mustafa. 2004. Childhood Religious Belief Development and Religious Education. Journal of Ankara University Faculty of Theology 45: 137–54. [Google Scholar]

- Köylü, Mustafa, and Cemil Oruç. 2017. Çocukluk Dönemi Din Eğitimi. Ankara: Nobel Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lamnina, Marinna, and Catherine C. Chase. 2019. Developing a thirst for knowledge: How uncertainty in the classroom influences curiosity, affect, learning, and transfer. Contemporary Educational Psychology 59: 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyens, Sofie M., and David Gijbels. 2008. Understanding the effects of constructivist learning environments: Introducing a multi-directional approach. Instructional Science 36: 351–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, Margaret M., Ellen Z. Goldberg, and Sarah K. Washington. 1999. Concept of death in a sample of Israeli kibbutz children. Death Studies 23: 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmedoğlu, Yurdagül. 2005. Okul Öncesi Çocuklarda Dini Duygunun Gelişimi ve Eğitimi. Ankara: TDV Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mishara, Brian L. 1999. Conceptions of death and suicide in children ages 6–12 and their implications for suicide prevention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 29: 105–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nagy, Maria H. 1965. The Child’s View of Death. In The Meaning of Death. Edited by Herman Feifel. New York: McGraw-Hill Book. [Google Scholar]

- Oruç, Cemil. 2014. Okul Öncesi Dönemde Çocuğun Din Eğitimi. İstanbul: Dem Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian, Raymond F. 1996. Invitation to the Psychology of Religion. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2018. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Translated by Mesut Bütün, and Selçuk Beşir Demir. Ankara: Pegem Academy Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, Jean. 2002. The Principles of Genetic Epistemology. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Pluck, Graham, and Helen L. Johnson. 2011. Stimulating curiosity to enhance learning. Education Sciences and Psychology 2: 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff, Donald, and Brown Ratcliff. 2010. Child Faith: Experiencing God and Spiritual Growth with Your Children. Oregon: Cascade Books. [Google Scholar]

- Selçuk, Mualla. 1991. Çocuğun Eğitiminde Dini Motifler. Ankara: TDV Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, Paul J. 2008. Interest-the curious emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science 17: 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenyayla, Gencal. 2021. A Prophet’s role model as a grandfather. Journal of Divinity Faculty of Kastamonu University 5: 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tamminen, Kalevi, Renzo Vianello, Jean-Marie Jaspard, and Donald Ratdiff. 2007. The Religious Concepts of Preschoolers. In Handbook of Preschool Religious Education. Edited by Donald Ratcliff. Eugene: Wipf & Stock, pp. 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tanık-Önal, Nagihan, and Esra Kızılay. 2021. How to teach science concepts in early childhood from the perspective of preschool teachers? Research And Experience Journal 6: 157–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tavukçuoğlu, Mustafa. 2002. The principle of wholeness and activity of religious sense in education of preschool child. Journal of Necmettin Erbakan University Faculty of Theology 14: 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, Aybiçe, and Kübra Yıldız. 2019. A comparative analysis on early childhood religious education approaches. Amasya Theology Journal 12: 121–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, Cemal, and Fatma Çapcıoğlu. 2015. Evaluation of Quran courses curriculum (4–6 age group) in the context of religious development theories. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction 5: 705–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünverdi, Mustafa, and Mehmet Murat. 2021. Example of the Prophet Mohammad instead of abstract concepts in the construction of religious belief in children. Antakiyat 4: 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Vardi, Özlem, and Serap Demiriz. 2019. Opinions of preschool teachers about children’s curiosities. e-Kafkas Journal of Education Research 6: 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vergote, Antoine. 1978. Çocuklukta din. Translated by Erdoğan Fırat. Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 22: 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vianello, Renzo, Kalevi Tamminen, and Donald Ratcliff. 1992. The Religious Concepts of Children. In Handbook of Children’s Religious Education. Edited by Donald Ratcliff. Birmingham: Religious Education Press, pp. 403–44. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, Lev S. 1978. Mind in Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, Lev S. 1985. Düşünce ve Dil. Translated by Semih Koray. İstanbul: Sistem Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, Lev S. 2004. Imagination and Creativity in Childhood. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 42: 7–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windmiller, Myra. 1980. Moral Development and Socialization. Boston: Allyn ve Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Yağcı, Samet. 2018. According to Teachers 4–6 Age Group Qur’an Courses of Presidency of Religious Affairs (the Case of Izmir). Master’s dissertation, University of İzmir Katip Çelebi, İzmir, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz, Kerim. 1983. Çocukta Dini Duygu ve Düşüncenin Gelişmesi. Ankara: Presidency of Religious Affairs Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yavuzer, Haluk. 2010. Çocuk Eğitimi El Kitabı, 26th ed. İstanbul: Remzi Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, Ali, and Hasan Şimşek. 2016. Sosyal Bilimlerde Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri. Ankara: Seçkin Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, Rukiyye, İlkay Ulutaş, and Serap Demiriz. 2018. Determining the Learning Interests of 5–6-Year-Old Children Receiving Preschool Education. Paper presented at the International Scientific Research Congress, Mardin, Türkiye, May 9–13. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).