4. Results

The people of the generation that we investigated, born in the 1940s–1950s, were raised and socialised in farming families, more or less humble and integrated into traditional communities. This event will mark these people, as will be seen later, in various aspects, and particularly in the relationships that they maintain with the land and with the natural environment. These families were generally large, with several children, in which the father was the breadwinner, who maintained a disciplinary and authoritarian position, not being close or affectionate. “My father was more rigorous… my mother was not so rigorous”, said one of the people interviewed in Life Stories (hereinafter, LF) (LF: woman with six children. Unfinished primary studies. Suitcase factory employee. Widow. very poor social origin), and another commented “my father was rigid, he was not a close person” (LF: woman with two children, retired primary school teacher, social origin, small agricultural owners). “My father especially”, said another of our informants, “he set a time for me to enter the house, if he went beyond that limit, he would hit me. He was strict, I had to follow the orders he transmitted” (LF: typographer, primary education, retired with three children, poor social origin).

The mother, on the contrary, appears in our interviewees’ stories as a much closer and affectionate figure, who assumed the role of caregiver, educator, and manager of the home: “My mother”, a woman told us, “was less rigorous… she was more affectionate” (LF: woman with two children. Primary education, typist secretary from a retired driving school. Humble social origin). “My mother”, commented a man, “got up later than my father, she made breakfast. If we (the children) had not yet gotten up, she would bring us breakfast to the room and sit next to the bed to talk to us (…). She was very loving, she was a mother” (LF: man with two daughters, technical engineer, retired secondary school teacher. Social origin small agricultural landowners with some day laborers in their care). “My mother was the one who gave us education”, said another of the people interviewed (LF: woman with two children, retired primary school teacher, social origin of small farm owners). The mothers of the people we interviewed in our Life Stories, belonging to the traditional peasant world and of more or less humble social origins, not only performed the role of caregivers and educators of their children and administrators of the home but also worked in the fields, either on their small property, in a self-consumption economy, or working for others, in the case of the poorest families. “Mi madre," commented uno de nuestros entrevistados, “se levantaba más tarde que mi padre, hacía el desayuno. Si nosotros (los hijos) aún no nos habíamos levantado, nos llevaba el desayuno al cuarto y se sentaba al lado de la cama a hablar con nosotros (…) She would go to the farm in the middle of the morning to pick vegetables for the meal” (LF: man with two daughters, technical engineer; retired secondary school teacher. Social origin small agricultural landowners with some day laborers in their care). “My mother had her land, her field," said another of our informants, “she raised her poultry, baked bread, worked in the garden, raised the animals… she cooked, she washed… (LF: retired small businessman. Four children. Primary education. Poor social origin). For this reason, by maintaining closer and more affectionate contact with her children, the figure of the mother remained more alive in the memories of the people we interviewed than that of the father. “I’m going to be frank”, said one of them, “the most important person in my life was my mother” (LF: retired small businessman. Four children, primary education. Poor social origin). The mother was also in charge of transmitting and instilling both religious values and practice in her children. “There was a lot of religious practice in my house. My mother went to mass on Sundays and took us with her”, said one of our interviewees (LF: woman with two children. Primary education, typist secretary from a retired driving school. Humble origin). “Since I was a child, my parents, especially my mother, took us to church”, said another (LF: man, retired primary school teacher with two children).

Our informants, as we said before, grew up in dense families, generally with several siblings, in which they internalised from a very young age values, attitudes, and forms of behaviour that were not transmitted through persuasive, reasoned, and argued speeches, which invited reflection to those who listened to them, but through other means, verbal and non-verbal, such as actions and gestures, images, narrations and descriptions, repeated religious prayers, examples, and expressions. All of which made sense and was assumed and internalised in the dense spaces of interactions in daily life. “Everything my parents transmitted to me was more by example than by word. The example of life conduct”, said one of the people interviewed (LF: man with two daughters, technical engineer; retired secondary school teacher. Social origin of small farm owners). “I learned from the experience of others”, said another, adding with special emphasis, “that they told me (…) Because that’s how I say, people learn, people observe (…) My mind was forming with what I was hearing” (LF: retired small businessman. Four children, primary education. Poor social origin). All these transmissions made sense in the different social settings in which daily life took place. “My mother”, commented one of the people interviewed, “was at home cooking and she asked me what colour the priest’s cape was, and I had to tell her” (LF: retired small businessman. Four children. Primary education. Poor social origin). Having thus received these transmissions, this was how several of the people we interviewed transmitted their life teachings: “I am going to tell you a story that I tell my grandchildren about giving everything to the children”, said one of them to introduce his story (LF: man, retired primary school teacher with two children). “I tell an episode that, frankly, made me feel bad”, said another (LF: man, three children. Retired typographer. Primary studies. Poor social origin). And another commented, “let’s take specific cases, how bread was made, for example; how the beans and peas were planted in the garden, how the gardening was done, the irrigation was done” (LF: retired small businessman. Four children. Primary education. Poor social origin).

Living and interacting with other people within hierarchical and positional structures was how they were transmitted and instilled—through images, actions, gestures, examples, narratives, and expressions first in the family and then in other spheres of life—values, attitudes, and forms of behaviour that signalled to those who received them their position within said structures. These transmissions were therefore related to what the sociologist

Basil Bernstein called “

restricted codes”—that is, inclusive forms of communication, closely linked to the interaction contexts of everyday life, in which

how it is said matters as much or more than

what it says—and that they are fundamentally narrative and descriptive rather than abstract and analytical (

Bernstein 1989, I, 85 ff.). People socialised in this type of codes, therefore, end up conceiving themselves as part of the world, of their world, and not as individuals facing the world (

Bellah 2017, p. 72).

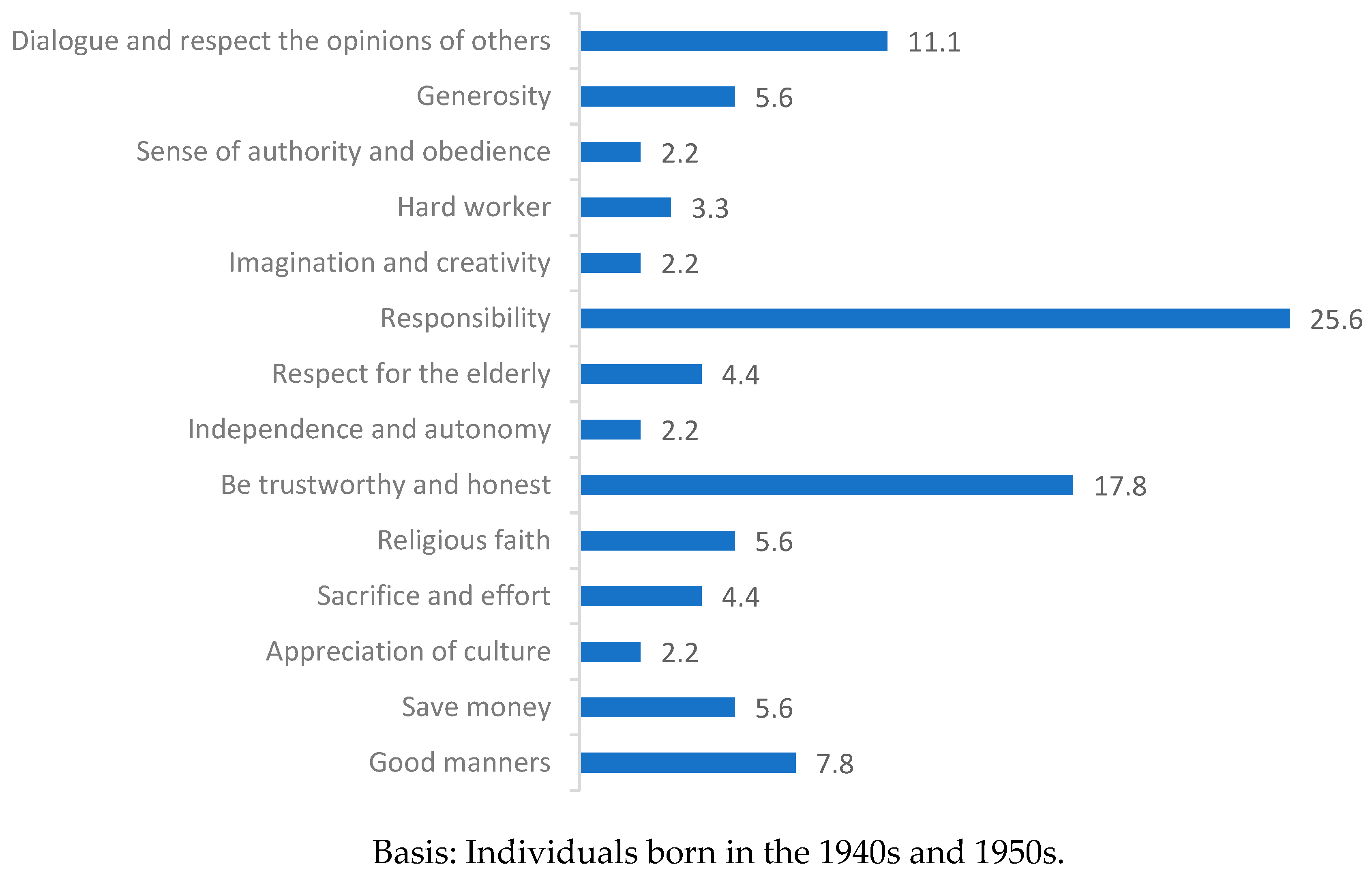

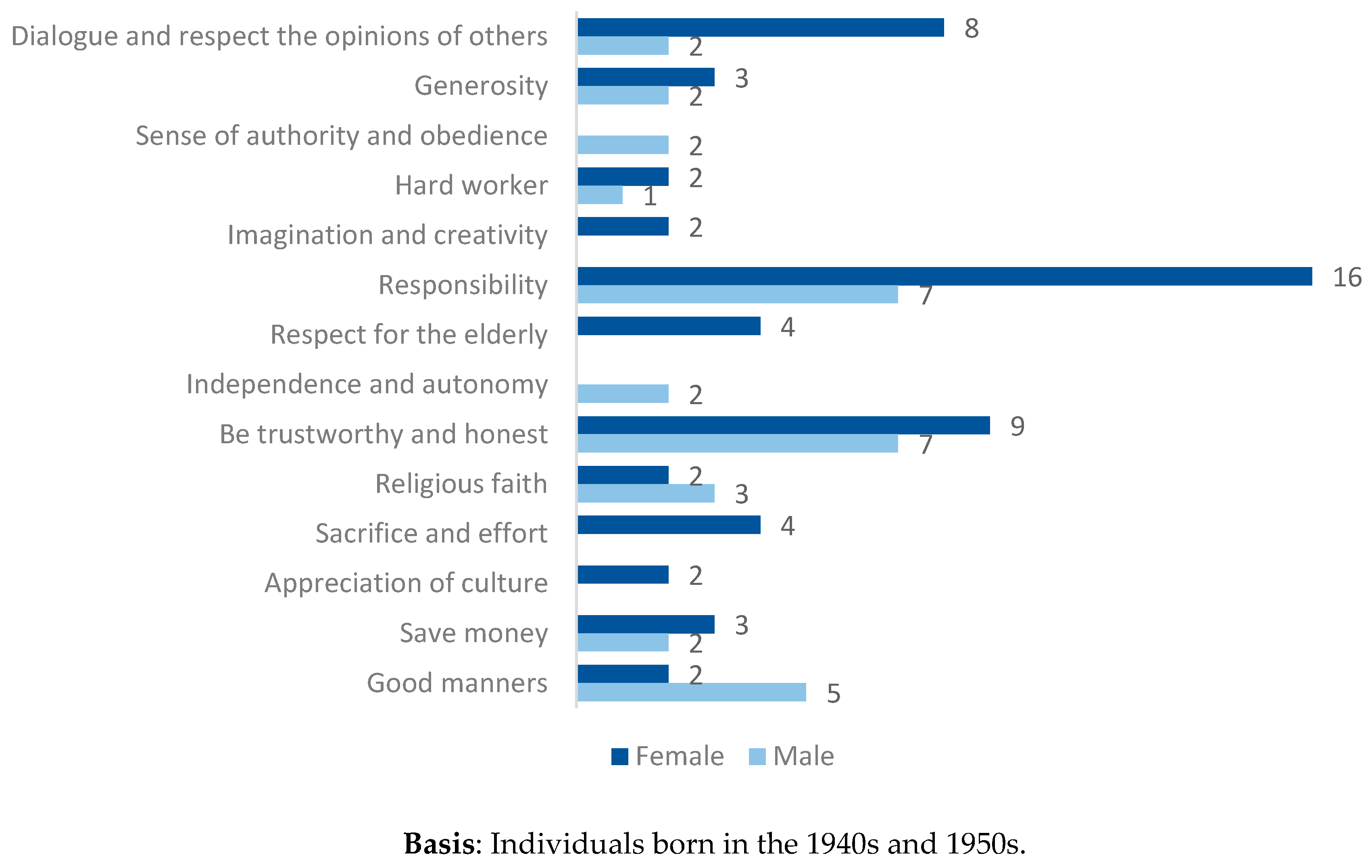

This is how the people we interviewed received and internalised a series of values that appeared again and again in their life stories. These values were those of honesty and trustworthiness, respect, solidarity, justice, responsibility, and work and, also, that of social mobility, linked above all to the work and educational trajectories of peasant families who were a little more comfortable with some land properties who could have certain social aspirations. Responsibility and being trustworthy and honest were, precisely, the most important qualities most people of this generation that we surveyed said that their families transmitted to them (25.6% and 17.8%, respectively, of those surveyed pointed this out. See survey, graph 1). These two qualities were also among the three most important that the majority of people surveyed indicated that they would like to transmit to their children, without differences related to gender being appreciated in both cases (see survey, graph 2) or at the level of education; the most important qualities that their families transmitted to them: χ2 (28) = 39,42, ns; the most important qualities to transmit to children: χ2 (26) = 14,95, ns).

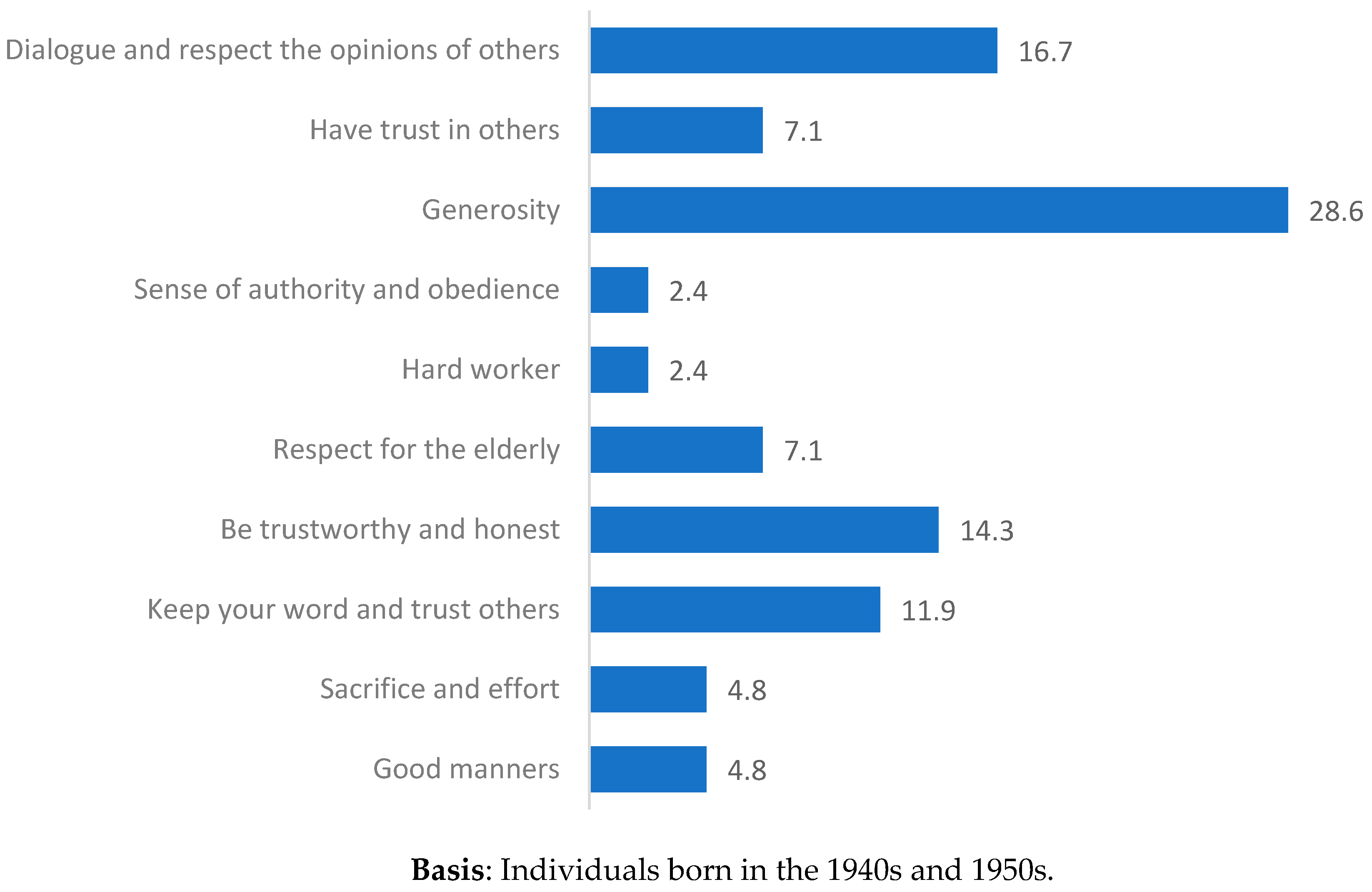

If we exclude this last value, the other values were impregnated with a clearly religious meaning linked to the beliefs and practices of the Catholic religion. “The values that I have transmitted to my children, associated with religious practice, are there”, "commented one of our informants, “the values of honesty, respect, that no one is more than anyone else, although recognizing one’s own merit” (LF: woman, retired primary school teacher, two children. Social origin small agricultural owners). Some of these values appeared among the three most important that the majority of people surveyed from this generation said they received through religion, specifically the value of generosity (28.6% of people surveyed), being honest and trustworthy (14.3%), and having your word and trusting others (11.9%) (see survey, graph 5). Without significant differences being seen regarding the gender and level of education of the people surveyed: gender (χ2 (8) = 7,87, ns); education (χ2 (16) = 18,32, ns).

Religious values, which, as noted before, give meaning to almost all other values, were received by the people we interviewed, and they also wanted to transmit them to their children, not only through words but also through repeated and continued practice. It was a religion of both believing and doing, typical of the popular religiosity (

Taylor 2014, vol. I, p. 112), in which beliefs and practices were closely linked: “There was religious practice in my house”, said one of the women interviewed (LF:

woman with two children. Primary education, retired typist secretary from a driving school. Humble social origin). “Being Catholic or not being Catholic meant nothing to me”, said one of the people interviewed. What meant to me were the doctrines that were practiced at that time. At my mother’s house it was praying the rosary. Before, it was not like today, there was a church that I went to, because my mother forced me” (LF:

retired small businessman. Four children, primary studies. Poor social origin). “At home we prayed almost every day at night”, said another person” (FG:

Male. Humble social origin. Primary education. Three children. Worked for 50 years in a textile company as a laboratory manager. Retired 10 years ago). And another of the people interviewed commented, “since I was a child, my parents, especially my mother, took us to pray the rosary on Sunday afternoon… My mother always took us to the church to participate in the celebrations, not only in mass, there was also the Christmas novena at that time” (LF:

Male, retired primary school teacher. Humble social origin). “My father”, said another of our informants, “taught us to pray and follow our Catholic religious life. He taught us and gave us a very good education. He taught us to do good, to go to the Catholic church. It was the good thing that he left us, and so did my mother” (LF:

woman with six children. Primary education unfinished. Suitcase factory employee. Widow. Very poor social origin).

This close relationship between belief and religious practice, typical of the religiosity of the people we interviewed, was what was later missing in the children. “I also instilled in my children to go to mass”, said one of our informants, “but they are already married, and I know that they don’t always go… They say that they have other occupations and that is why they don’t always go to mass on Sundays.” (…). They are Catholic, only they don’t go to mass as I would like them to, because they say they don’t have time” (LF:

woman with two children. Primary education, retired typing secretary from a driving school. Humble social origin). “It especially hurts me that my children do not follow the religious values that I transmitted to them”, said another of the people interviewed, “although at first they went to mass with me, later they began to make excuses” (LF:

woman, retired primary school teacher, two children. Social origin small agricultural owners). “When they were younger”, said another, also referring to her children, “they started going with me, but then they started to stray a little, but they are Catholics (LF:

retired typographer, primary education. Three children, poor social origin). And another of our informants commented that, although his daughters continue with the religious values that were transmitted to them, “they doubt more”, he said, “than I doubted, mainly in religious practice” (LF:

man with two daughters, technical engineer; retired secondary school teacher. Social origin small agricultural owners with some day laborers in their charge). As can be seen, while religion was a lived and experienced reality for the parents, for the children, it was not lived or experienced in the same way, especially as they grew up. For the former, it was a plausible and taken for granted reality based on which, they interpreted the world, while, for the latter, it was neither plausible nor taken for granted (

Berger 1977, 65 ff.), since they wondered about religion from the possibility of disbelief (

Taylor 2015, vol. II, pp. 47 ff.). The transmitted belief thus gradually languished, as it was not revitalised through daily practice, because the practice involves introduction into a ritual and symbolic world without which the belief loses its previous meaning, as it can no longer be understood by referring to that practice (

Douglas 1988, pp. 64 ff.). Along these lines, as belief is separated from practice and is gradually deinstitutionalised (

Beck 2009, 94 ff), it ceases to be a fundamental constitutive part of one’s own identity, losing the capacity to reconfigure subsequent experiences (

Mannheim 1993, pp. 214–15). Hence, communication between each other, parents and children, becomes more difficult, increasingly distanced in their way of understanding religion and, therefore, also the world.

The religious transmissions that, as we have seen, the members of this generation received at first in the family environment through a close relationship between belief and practice continued later in other areas, such as the parochial. “There I discovered”, said one of the people interviewed, “the value of living in society and sharing common values. Those meetings marked me so much that today I continue to belong to those parish groups” (FG: woman, two children, retired school janitor, with primary education. Very poor social origin). People who studied in seminaries, a means of social promotion for the children of humble families, continued their religious socialisation in these institutions. “Later”, commented one of these people, “I entered the seminary, and naturally I followed the religion, and I maintain it to this day” (LF: Male, retired primary school teacher. Humble social origin). In other cases, said socialisation took place in religious institutions such as Ação Católica. “Ação Católica”, commented one of our informants, “gave me a general culture (LF: woman with primary education. Two children. School janitor Retired. Very poor social origin). School institutions, many of them linked to the Church, were also a means of religious transmission for members of this generation. In one of these religious schools, one of our informants told us that she “prayed every day, especially in the month of Mary” (LF: woman with two children, retired primary school teacher, social origin of small agricultural owners).

People who have been thus socialised in the religious universe understand and judge the world, as will later be seen, through religious beliefs and values, because religion is part of their individual and social conscience (

Berger 1977, p. 104). But religion also provides faith and confidence, reducing the uncertainties and tensions that life can cause, a faith in the existence of someone superior to whom one wishes to bond, seeking protection, security, and trust. “Religion”, said one of our informants, “unites us. Faith has to have someone, I have to have someone who is superior, who I feel is superior (…). I have someone? Yes. I have someone to ask for help (…) Because what is faith? Why do I want to be religious? Because that’s where I’m going to seek for my faith. And then the following happens. How I think; I am aware of any problem, but I have faith that God will help me (LF:

retired small businessman. Four children, primary education. Poor social origin). From this point of view, religious faith involves the externalisation of individual conscience. In effect, the individual needs to project himself onto someone external to himself to find himself, to find a source of meaning that transcends his own subjectivity. This appeal to someone or something that transcends the sphere of the immanent is one of the main characteristics of religious beliefs (

Taylor 2014, vol. I, p. 47). Although this appeal to transcendence has been interpreted as a source of alienation (

Marx 2001), it can nevertheless act in another direction, providing a meaning to existence, both the happiest and joyful and the saddest and most miserable (

Berger 1977, 104 ff.). If, even so, it can be said that religion alienates, it is not because it interferes with a supposed original and natural individuality subject only to its own conscience, corrupting it to the extent that it transcends it (

Marx and Engel 1994, p. 40). If religion alienates, it is, on the contrary, because it constructs worlds of meaning in which human beings project themselves fleeing from chaos and anomie (

Berger 1977, 114 ff.).

Religion acts for the people we interviewed as a source of transcendence, allowing them to find meaning, stability, and order in their lives, permeating the main values that articulate the different spheres of their existence. To do this, individuals need to project themselves beyond themselves, into a higher reality that transcends them. The different values that they repeated over and over again—honesty and trustworthiness, respect, solidarity, justice, responsibility, work, and savings—imbued with a religious sense represent so many spheres of that transcendence.

Raised and educated in families and in peasant communities, the land is, for these people, one of the dimensions of this transcendence, because it provides meaning, order, and stability to the world. Therefore, this care must be respectful of the natural environment from which one benefits and which also benefits us. The relationship with the land thus incorporates many of the values mentioned above: honesty and trustworthiness, respect, solidarity, justice, and responsibility. This idea of caring for the earth so that it produces its fruits through a relationship of interdependence between human beings and their natural environment is presided over by the values of solidarity, honesty, responsibility, and justice, and it was transmitted to our interviewees by the peasant families in which they grew up. “My mother”, said one of these people, “transmitted to me the value of respecting and caring for the earth and nature as well (…) My mother had her land, her field, she raised her birds, her rabbits (…). She baked the bread, took care of the garden, raised the animals, killed them…” (LF: retired small businessman. Four children, primary education. Poor social origin). These values were what our previous interviewee said he put into practice throughout his life. “For about 20 or 30 years I dedicated myself to a small garden on my property, I even went overboard. And that I ended up verifying after a few years (…). I prepare the land and put the seeds, I put the plants. I want them to grow. I don’t want them to lack food or water. They begin to grow (…). I begin to think, my interior and my mind ended up being more humanised. I treat that with affection. That is humanism too (…) And then the fruit, the distribution of the fruit, the pleasure it gives” (LF: retired small businessman. Four children, primary education. Poor social origin).

However, this relationship of exchange between human beings and their natural environment was far from being, as we said before, egalitarian, since it implied the recognition of a certain natural order that is offered to human beings but that they have not created. Hence, the relationship of these people with the land is dominated by a certain attitude of gratitude for what they have received but do not fully deserve. This attitude is reflected in the following testimony, in which one of the people interviewed, raised in a peasant family of small landowners, told of the relationship that his mother had with the land. “My mother”, he said, “would go to the garden mid-morning to pick vegetables for lunch, and when she returned, she almost always said, thank God, look what the garden has given us.” (LF: man with two daughters, technical engineer; retired secondary school teacher. Social origin small agricultural landowners with some day laborers in their care). This attitude towards the land, which reflects the values of solidarity and gratitude, values that the people interviewed internalised in their peasant families of origin, was also what they themselves expressed in their respective life stories. “I helped with the work in the fields until I went to university”, said one of these people, “and I also liked to help the neighbours, for example, picking potatoes. I always liked, and I still like, farm work, I find great satisfaction in it, because it reminds me that nothing can be achieved without the help of God and other people.” (LF: woman with two children, retired primary school teacher, social origin of small farm owners).

When, on the contrary, this relationship of interdependence with the natural environment is broken, it is irreversibly degraded. “We are”, commented one of our informants, “breaking the balance with nature, with the land, we abuse it, and therefore also those who have offered it to us for our own benefit… We are doing this and no one is going to stop it.” (LF: man with two daughters, technical engineer; retired secondary school teacher. Social origin small agricultural landowners with some day laborers in their care).

This way of understanding the relationship with the natural environment and, in particular, with the land as a relationship of unequal interdependence between nature, invested with a certain sacred character, and the human being, grateful for what it offers, is typical of pre-industrial societies. Thus, for example, in the ancient Greek world, agricultural occupations were considered to involve the relationship of the human being with a nature that had sacred attributes and that was subject to divine will, a nature on which the human being depended to ensure his subsistence and which he therefore had to face with the attitude of the warrior (

Vernant and Vidal-Naquet 1988). This way of understanding the relationship with the land was very similar to that of Ancient Rome. Cicero therefore included agriculture among the noblest occupations in societies in which work had the worst consideration (

Arendt 1998;

Vernant 1985). “But among all the occupations through which something is acquired”, he wrote, “the best, the most abundant, the most delicious and typical of good, is agriculture” (Cicero, First Book, chap. XLII, p. 80) (

Cicerón 1995, First Book, chap. XLII, p 80). This way of understanding the relationship with the earth, as something that the Divine Creator offers to human beings so that they can work for their own benefit, was also typical of the medieval world, although interpreted in Christian terms (

Le Goff 1983). And we could still find it much later in thinkers like Thomas Hobbes when he wrote “As for the abundance of materials, it is limited by nature to those goods which God gives us, either freely by making them spring from the earth and the sea–which are the two breasts of our common mother –, either in exchange for work (…). So, abundance will depend, after having been given to us by the favour of God, on the work and industry of men” (

Hobbes 2004, p. 217).

Modern Western thought breaks with this way of thinking with respect to the earth and the natural environment when it no longer conceives this reality as something that the Divine Creator offers to human beings for their sustenance so that he can only intervene in it by bringing to fruition with his effort what was already potentially created. That is why his attitude towards the natural environment is one of admiration and gratitude. This rupture is clearly observable in the thoughts of John Locke: “I think”, he wrote, “that it would be a very modest estimate to say that, of the products of the earth that are useful to man, nine-tenths are the result of work. Well, if we estimate things precisely as they come to us for our use…what they strictly owe to nature and what they owe to our work, we realize that in most of them ninety-nine percent must be attributed to our efforts” (

Locke 2006, pp. 67–69). From this perspective, admiration and gratitude are no longer directed toward nature but toward human work, which, throughout modernity, will become the source of a sacredness and transcendence that previously resided in nature. Human work as a source of productivity will end up being one of the main signs of progress, identified with its capacity to transform nature, not so much for the benefit of the well-being of humanity but, rather, for the industrial system it serves (

Bury 2009, 224 ffs.). And this progress, as is known, knows no limits.

The people we interviewed were much closer, on the contrary, as has been shown, to the conception of nature and the natural environment linked to the premodern mentality than to the latter that began to develop with the thoughts of John Locke. From this perspective, they find in the relationship with their natural environment, through the cycle of repetitions that it imposes, a source of stability and order that makes it possible to face the disorders that ordinary life produces. In this sense, nature, imbued with a sacred character, acts as a transcendent dimension that brings order where chaos would otherwise reign. The perspectives of the people we interviewed, aligned with a mindset that considers nature and the natural environment not as resources to be exploited but as a sacred and intricate extension of human life, is highly resonant with the teachings of the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si that highlights the interconnectedness of all living beings and our collective responsibility to the Earth. As Pope Francis observed, “everything is interrelated and authentic care for our own lives and our relationships with nature is inseparable from fraternity, justice and fidelity to others” (no. 70).

According to Laudato Si, it is not only a question of environmental ethics but also of social ethics, as one cannot think of establishing an ethics of fraternity and friendly dialogue with the environment without social love. As LS no. 231 stated, “Social love is the key to authentic development: ‘In order to make society more human, more worthy of the human person, love in social life—political, economic and cultural—must be given renewed value, becoming the constant and highest norm for all activity’. In this framework, along with the importance of little everyday gestures, social love moves us to devise larger strategies to halt environmental degradation and to encourage a culture of care which permeates all of society.” This reality resonates with the feelings of our interviewees, for whom caring for the environment is not an isolated issue but an integral part of a balanced and ethical life.

Furthermore, the sacred conception of nature, expressed by our interviewees, is parallel to what Pope Francis in the LS described as “the value proper to each creature” (no. 16). Nature, in this sense, is not just a backdrop for human activity but a manifestation of divinity that deserves all our respect and care.

In this context, Pope Francis’ words in Laudato Si were nothing more than a call to action and reflection for all humanity, suggesting that “integral ecology is also made up of simple daily gestures which break with the logic of violence, exploitation and selfishness” (no. 230). “The challenge now is how to translate this deep understanding and these sensitivities into policies and actions that protect the environment and promote a true “culture of care” (no. 231).

In this sense, the people we interviewed not only understand the relationship with their natural environment through their beliefs and religious values, but they also interpret in this way the relationship they establish with the other areas that articulate their existence. In all of them, religion intervenes in the same way, giving a deep meaning to the values they share, those of honesty and trustworthiness, respect, solidarity, justice, and responsibility.

The dense religious universe in which the people we interviewed were socialised, linked to a series of practices and values such as respect, honesty and trustworthiness, solidarity, justice, and responsibility, grant confidence and meaning to the relationships they have established with the nature they inhabit and with other people, even when their lives have been full of uncertainties.

All of this is related to a sense of time that is also stable and organised, such as the superior time of transcendence (

Taylor 2014, vol. I, p. 109) or that of the repetition of the agricultural cycle or that other linked to the tradition of the values transmitted by previous generations or that of a long and continuous working life, which stability is also especially valued (

see survey, graph 6). In this way, they can create islands of security in the middle of the ocean of insecurity in which they often have to live (

Arendt 1999, p. 106), transferring the future to the present and relating the present to the past (

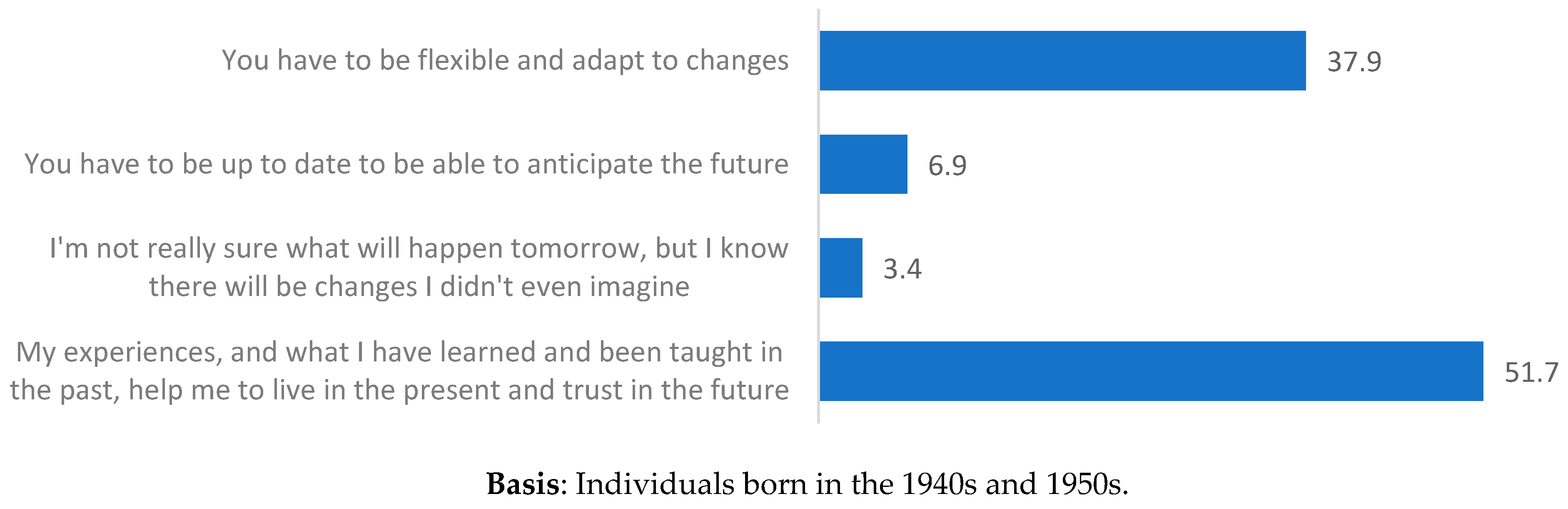

Adam and Groves 2007, p. 47). This is part of the trust they intend to communicate to the following generations. Thus, 51% of the people we surveyed indicated, when asked about the phrase with which they most identify, the one referring to “my experiences, and what I learned and was taught in the past, help me live the present and trust in the future” (

see survey, graph 7).

Religion also gives deep meaning to work. The people we interviewed understand work from a double perspective, both positive and negative. From the negative point of view, work was understood as a destiny that human beings had to carry in this earthly life to provide for themselves. He who does not work should not eat”, said Saint Paul in the Gospel (Second Letter to the Thessalonians, 3). “It was that culture”, said one of the people interviewed, “that we have to work, that we must work. In this world we have to work. He who doesn’t work doesn’t eat. It was this idea. We have to work. It was this” (LF: woman, two children, retired school janitor, primary education. Very poor social origin). However, if the hardships and sacrifices that the work required were more bearable, it was because this activity was associated with the values mentioned above, impregnated with a religious sense. From this perspective, work is a moral duty, without which fulfilment one cannot become an honoured and honest, dignified, and respectable person. “And this”, said one of the people we interviewed, “was what I taught my children. Do everything as God wanted, work, be honest, and try not to steal from the bosses (…). This was the most important thing my parents taught me, to be hard-working, serious, honest, and work and not be watching… and help others… it was what I taught my children, and it was what I did in my work” (LF: woman with six children. Primary studies unfinished. Retired suitcase factory employee. Very poor social origin). “All my work”, said another person, “with a lot of suffering at times—I always continued to see it as a form of personal fulfilment, because if I don’t work, for me it is a very great frustration because I don’t do anything; even if I wasn’t going to create anything, I was at least contributing to something” (LF: female with primary education. Two children. School janitor. Retired. Very poor social origin). One of the aspects of this appreciation of work, with a clear religious influence, is the boundness to social utility. “Later on”, one of our informants told us, “I got to know Ação Católica. I started in pre-adolescence…there I began to develop, to have knowledge of various things, and to understand that, in fact, we human beings have value, and that work is an important thing for the development of society (…) Today I understand that our work has to be seen as help for social development. All jobs have to be seen from this point of view. I try to pass this on to my children; when they complain about their job, I tell them, try to think about what you contribute to the development of society, it may not be the best job, but it is the one you can help with” (LF: female primary education. Two children. Retired School janitor. Very humble social origin).

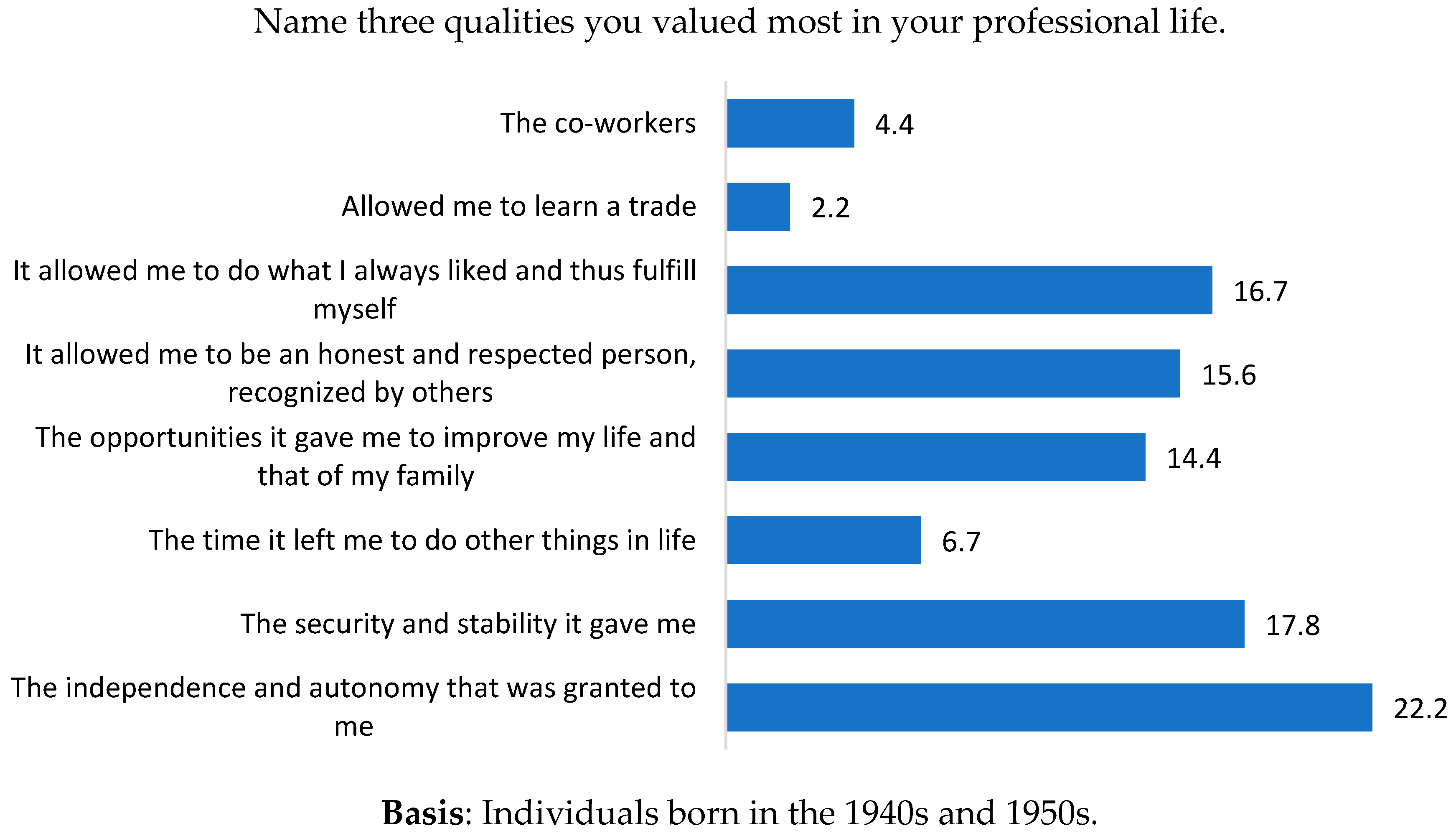

This aspect of work, linked to the values of honesty and respect, also appeared as one of the most prominent values in the survey we carried out (see survey, graph 6).

This sense of work, associated with a moral and social duty with a clear religious background, made the tensions derived from the need and obligation to work, with the sacrifices and hardships that all this entailed, not only much more bearable but also acquired greater meaning. One could thus feel more or less satisfied, being considered a worthy and respectable person. “My father told me”, commented another of the people we interviewed, “that when the boss passed by, not to lower my head, to look him in the face, this way you show that you are doing your duty; and I did it like that… I always thought that, if I was responsible in what I did, I didn’t have to lower my head” (LF: woman primary education. Two children. Retired school janitor. Very poor social origin).

Work, understood in this way as linked to some source of transcendence and permeated with a religious sense that elevated it to a social and moral duty, mitigated the tensions generated by work life, full of hardships and sacrifices. These sacrifices could also be compensated by the expectation, fully secular and linked to immanent ordinary life, of social mobility. But this expectation was, for the people of the humblest social status that we interviewed, more of a wish and a distant hope than a reality. Therefore, it could not nourish the meaning of a working life, which would otherwise fall into anomy (

Durkheim 1995). “When I stopped studying, what was going through my head”, one of these people told us, “many things, I wanted to be equal to someone, but I didn’t have any ability or knowledge (…) what I had to do was take advantage of the job that arose to earn some money for everyday life, and that’s how it was” (LF:

man, three children. Retired typographer. Primary studies. Poor social origin). If, for these people, their work life had any meaning, it was, above all, in relation to the social and moral duties assumed, to which we have previously referred. Those other people we interviewed, who prospered more socially, experiencing processes of social mobility either from a very humble position or from one that was a little more comfortable due to being children of small agricultural owners, give greater meaning to their working life in relation to these processes. This sense, far from lowering that other one linked to the fulfilment of the moral and social duty associated with work, complements it. Thus, the same person who said that “through my work I managed to evolve, but for that I had to dedicate myself a lot to work” (LF:

retired small businessman. Four children. Primary education. Poor social origin) also told us “In my house, unfortunately, we had hardly anything… there were values, respect” (LF:

retired small businessman. Four children. Primary education. Poor social origin).

Work, understood in this way, was not a matter of choice but rather an assumed social destiny, and as such, the free time that can be left to devote oneself to other occupations in life was barely valued (see survey, graph 6).

This sense of existence provided by religion, linked to the belief in some transcendence that also gave meaning to the fulfilment of a series of social and moral duties in different spheres of life, allowing the tensions that these spheres generated to be articulated, is largely absent from the school environment. In fact, the school trajectories of several of the people we interviewed—rather short, finishing before finishing primary school—showed the little hope they had in the school environment. For them, school was a short waystation prior to their premature incorporation into the world of work, in the case of men, or to agricultural and domestic tasks in that of women. “I, unfortunately”, said one of them, “in my house of 10 people, the most educated was me, who was in the 4th grade of primary school (I had not therefore finished primary school, which was made up of 6 grades). At that time there were other values” (LF: retired small businessman. Four children. Primary education. Poor social origin). “Most of my colleagues”, commented another, “who had the same opportunities that we had, had parents who did not know how to read and who did not know how to value the possibilities that the school had. So, I did the third class when I was 9 years old” (LF: woman with six children. Primary education not completed. Suitcase factory employee. Widow. Very poor social origin). “There was no obligation to study, and I didn’t study”, said another of our informants, “and then my mother made me learn sewing” (LF: woman with two children. Primary education, retired typist secretary from a driving school). “Those who finished the fourth year (primary education without completing)”, another told us, “left their studies, because they were already tired of school and wanted to go to work. And I also got to work early. The value of studies had never been instilled in us” (FG: female primary education. Two children. School janitor Retired. Very poor social origin). And in this same direction, another of the people interviewed said that “before April 25 (the date of the Portuguese Carnation Revolution, which started democracy and the modernization of the country) the majority of parents said that their children, starting from the 4th grade (unfinished primary school), had to go to work to help raise the other siblings, because if they continued studying they lost the possibility of helping the family” (FG: woman, retired textile industry worker, with primary studies. Low origin class). “In my house of 10 people, the most cultured was me, who was in the 4th grade of primary school. At that time there were other values” (LS: retired small businessman. Four children. Primary education. Poor social origin). And among these values, as we said, the school value did not have a main place, especially for the children of families with the humblest social status, who did not see the possibility of improving their social position through the meritocratic school route. In fact, in the survey we carried out, when the people surveyed were asked to indicate the three aspects that they valued most of those that were transmitted to them at school, one of the least valued answers was the “importance of a title to work” (see survey, graph 4).

The school universe, disconnected from the fulfilment of social and moral duties and impregnated with a religious sense that gave meaning to other spheres of their lives, therefore provided little hope to the people we interviewed, especially to those of humbler social status, but also created few frustrations. “They did not expect anything they had not obtained”, and thus, “they did not obtain anything they had not expected” (

Bourdieu and Passeron 2001, p. 223). Devoid of those moral references, of those horizons of significance (

Taylor 1996, pp. 43 ff.) linked to the values of

honesty and

trustworthiness,

respect,

solidarity, and

justice, little good was remembered from school, other than moments of liberation in the company of peers. “At school”, said one person, “I still have the memory of some classmates, that we greet when we see each other, but nothing more than that” (LF:

woman with two children. Primary education, retired typist secretary at a driving school. Humble social origin). Friendship with peers is precisely one of the aspects that is most valued by the people of this generation that we surveyed, regardless of gender and their level of education (

see survey, graph 4) (sex: χ

2 (10) = 25,24, ns; education: χ

2 (20) = 23,29, ns).

Furthermore, school was remembered by these people as a disciplinary, rigid, and authoritarian setting that, above all, instilled fear. “Inside the classroom”, said one of the people interviewed, “there was a lot of strictness (…). At that time, they conveyed fear… I felt humiliated (LF: female primary education. Two children. Retired school janitor. Very poor social origin). “At that time”, commented another, “there was respect for the teachers, even fear, because they were rigorous and severe (LF: woman with two children. Primary studies, retired typist secretary from a driving school. Humble social origin).

But even those of our interviewees from slightly more well-off families, who harboured expectations of social mobility that they finally ended up achieving, barely mentioned when referring to their school years any of the values mentioned above other than those referring to their desire to improve socially. “In primary school”, said one of these people, “nothing special was transmitted to me. The most important thing I learned was perhaps the importance of work” (LF: retired primary school teacher. Two children). “There wasn’t much proximity between teachers and students”, said another person. “What there was, was a lot of discipline; Everything was absolutely planned, and whoever did not do what was ordered was punished (…) I told myself, I have to be better than my parents” (LF: woman, retired primary school teacher, two children. Social origin of small agricultural owners). “My father”, commented another person, “wanted me to study so that I could have a better future, and to a certain extent I did” (LF: man with two daughters, technical engineer; retired secondary school teacher. Parents who own farms with some workers). The meritocratic value of social mobility was, therefore, what gave meaning to the school universe, making the disciplinary and authoritarian environment that reigned there more bearable. But this value was, above all, instrumental, a means to an end. Well, what gave coherence to the lives of these people, as they themselves told us, was the fulfilment of the values of honesty, trustworthiness, respect, solidarity, and justice, which, with a religious background, were fundamentally linked to the family, community, and parish worlds and to the work world and which they also tried to transmit to their children. “In society”, said one of these people, “we have the obligation to defend a name, to respect and to be respected (…) My daughters retain many of the values that we have transmitted to them, especially because they are honest people, they are ashamed; those things that are not judged now” (LF: man with two daughters, technical engineer; retired secondary school teacher. Agricultural owner parents with some workers in their care). And another person commented, “the values that I have transmitted to my children, associated with religious practice, are there; the values of honesty, respect…” (LF: woman, retired primary school teacher, two children. Social origin small agricultural owners). Some of these values, particularly those of responsibility, honesty, and trustworthiness, were also quite appreciated by the people of this generation that we surveyed (see survey, graph 2).

Moments of leisure were remembered by the people we interviewed, during the short period of their childhood, as a moment of liberation from the harshness of life. “I remember freedom”, one of these people told us. “With freedom we were like birds (…). We were happy, we didn’t feel tied down” (LF: woman with primary education. Two children. School janitor. Retired. Very poor social origin). “Half a dozen kids would get together”, said another, “we would walk to the river to bathe; there was misery, but we were happy in life (…). It was being with each other, forgetting the discomfort of an empty stomach” (LF: retired typographer, primary education, three children, poor social origin). But when this last person was asked about the reasons for his happiness, in addition to the feeling of liberation from the sorrows of life that leisure provided, the values that gave, and still give, meaning and stability to his world came to light. “There was that, how can I say, there was peace and there was respect, which existed at that time, not so much today. And we had fun with each other” (LF: retired typographer, primary education. Three children, poor social origin). Already in youth, those moments of liberation from childhood were reduced to the rare moments in which one could forget a little about the fatigue produced by daily work and miseries. “I left at 7 in the afternoon, then I had to make food for the next day, and it was not possible. But on the weekend, I would go for a little trip”, said one of our informants (LF: woman with two children. Primary studies, retired typist secretary from a driving school. Humble social origin). And another said, “we went to eat the chicken and the roast on Sundays. And I remember a lot of those good things that I had in life” (LF: woman with six children. Primary education not completed. Suitcase factory employee. Widow. Very poor social origin). Another man commented, “we went to parties; At that time in those parishes around the city there were parties, various parties, and there was a man who played music to dance to, and we asked him for a dedicated record. It was what there was. This way we would forget about the discomfort in our stomach (he said it with a broad smile). That was the way to have fun” (LF: retired typographer, primary education. Three children, poor social origin).

We have shown so far how, for the people of the 1940–1950 generation that we interviewed belonging to the geographical area of

Braga in

Portugal, that religion, in which practice and belief are closely linked, provides meaning to the values that organise and give meaning to the relationships that these people maintain with their natural environment and with other people in the different spheres in which their daily lives unfold. We have also shown how religious beliefs allow these people to face the tensions that arise in their lives. Through the relationship they establish between the sphere of the transcendent and the immanent of their religious life and their ordinary life, they create bridges of stability, trust, and security in the midst of the oceans of precariousness and insecurity in those in which they have had to live (

Arendt 1999, p. 106).

The way that the people we interviewed have of relating to their natural and human environment, of understanding it and of judging it, through their religious beliefs, which gives meaning to their main moral and social values, is the one that their children no longer have, for whom the received belief is no longer in relation to their practice. Their way of understanding and judging the world thus becomes more reflective with respect to received religious beliefs and with less capacity to reconfigure their own experiences and life situations. (See

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).