Justice at the House of Yhw(h): An Early Yahwistic Defixio in Furem

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Elephantine Yahwistic Community

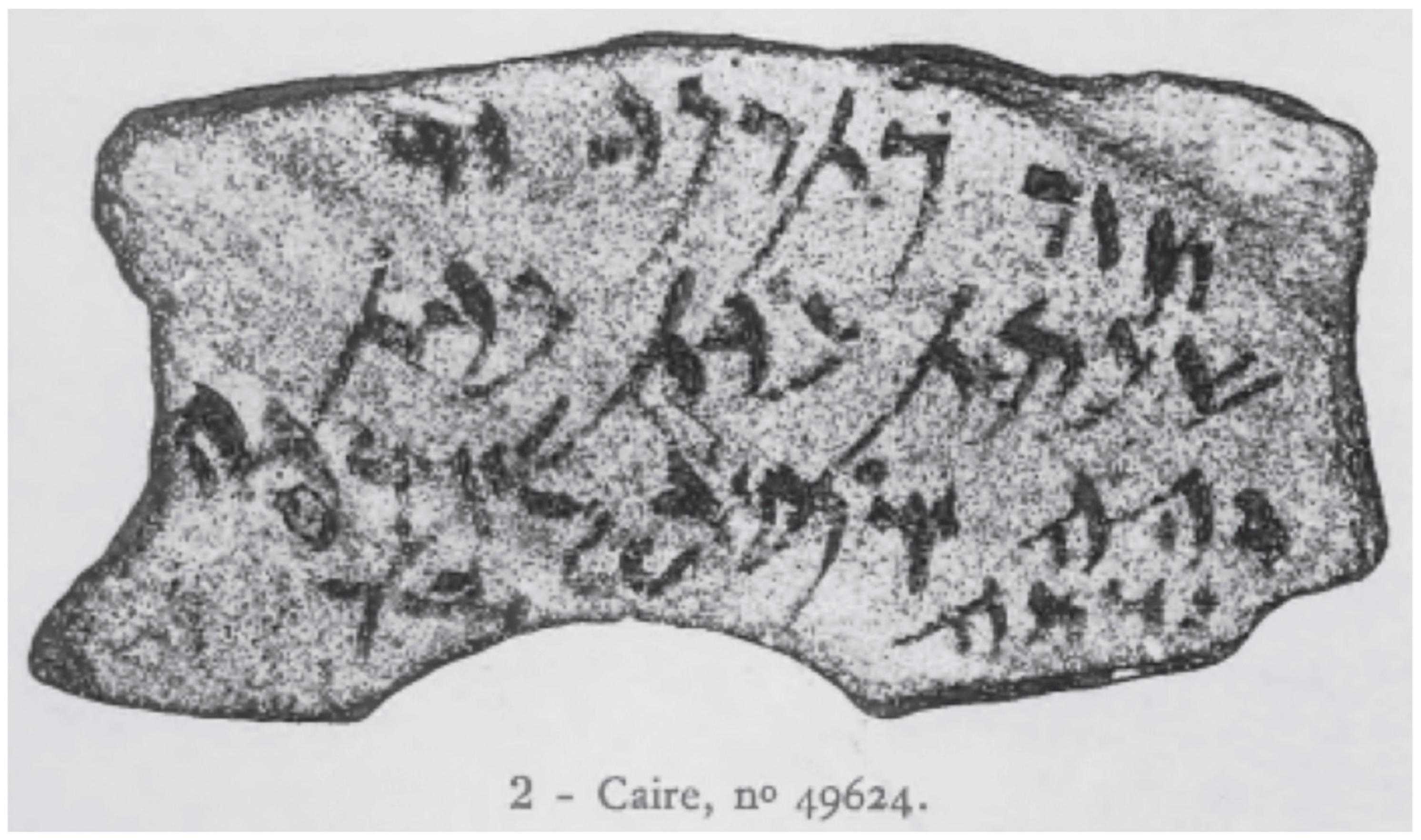

2. The Elephantine Curse Ostracon (Porten and Yardeni 1999, D7.18)

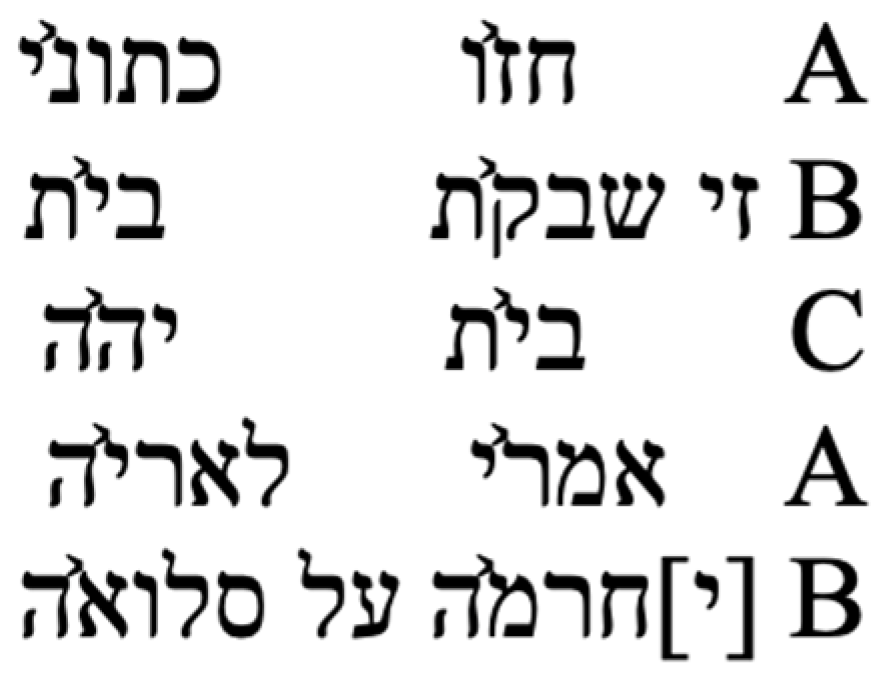

2.1. Text

2.2. Translation

2.3. Epigraphic Analysis

3. Commentary

3.1. Literary Characteristics

3.2. Defixio in Furem

I dedicate (ἀνατίθημι) to the Mother of the Gods the gold pieces that I have lost, all of them, so that the goddess will track them down and bring everything to light and will punish the guilty in accordance with her power and in this way will not be made a laughingstock.

Artemis “dedicates” (ἀνιεροῖ) to Demeter and Kore and all the gods with Demeter, the person who would not return to me the articles of clothing, the cloak, and the stole, that I left behind, although I have asked for them back. Let him bring them in person (ἀνενέγκα[ι] αὐτός) to Demeter even if it is someone else who has my possessions, let him burn, and let nun publicly confess ([πεπρη]μένος ἐξ[αγορεύ]ων) his guilt. But may I be free and innocent of any offense against religion. if I drink and eat with him and come under the same roof with him. For I have been wronged (ἀδίκημαι γάρ), Mistress Demeter.

4. Biblical Parallels

1 There was a man in Mount Ephraim whose name was Mykyhw. 2 He said to his mother, ‘The eleven hundred silver that were taken from you, and you uttered a curse, and even spoke it in my hearing—here, I have the silver. I took it.’ And his mother said, ‘blessed be my son to Yhwh!’ 3 And he returned the eleven hundred silver to his mother, and his mother said, ‘I have consecrated the silver to Yhwh from my hand for my son, to make a graven image and an object of cast metal.’ 4 And he returned the money to his mother, and his mother took two hundred silver, and gave it to the silversmith, and he made it into a graven image and an object of cast metal; and it was in the house of Mykyhw. 5 And the man Mykh had a house of god, and he made an ephod and teraphim, and installed one of his sons, who became his priest.

8 Will man rob God? Yet you are robbing me. But you say, ‘How are we robbing you?’ In your tithes and offerings. 9 You are cursed with a curse, for you are robbing me; the whole nation of you. 10 Bring the full tithes into the storehouse, that there may be food in my house; and thereby put me to the test, says Yhwh Ṣbʾot, if I will not open the windows of heaven for you and pour down for you an overflowing blessing.

2 And he said to me, “What do you see?” I answered, “I see a flying scroll; its length is twenty cubits, and its breadth ten cubits”. 3 Then he said to me, “This is the curse that goes out over the face of the whole land; for everyone who steals shall be cut off henceforth according to it, and everyone who swears falsely shall be cut off henceforth according to it. 4 I will send it forth, says Yhwh Ṣbʾot, and it shall enter the house of the thief, and the house of him who swears falsely by my name; and it shall abide in his house and consume it, both timber and stones.

5. Yhw(h) as a Lion

6. Women in Yahwistic Liturgy

In spite of consistent efforts by (predominately female) Egyptologists from the late 1970s onward, titles and epithets denoting ancient Egyptian women’s work outside the home still are often dismissed as honorific, or treated in an overly sexualized manner, or reduced to servant status. Considered separately, some of these arguments may appear cogent, logical, or even plausible. However, viewed collectively, they have the effect of a concerted effort—conscious or unconscious—to undermine ancient Egyptian women’s agency, as seen in their ability to exercise power in influential positions, in their self-expression through written modes of communication, or in exercising economic autonomy.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The island and its colony/fortress are referred to as Yeb (יב) in the Aramaic and Ἐλεφαντίνη in Greek. This name derives from the word for “elephant”, or “elephant tusk” (ꜣbw) in the Egyptian language although it is not clear what precisely its connection to elephants might have been. |

| 2 | Outside the Bible, Yhw(h) is relatively scantly documented and is not necessarily a specifically Israelite deity (Cf. the Hittie governor of Hamath, Yahu-Bihdi whose name was written with the DINGIR divine determinative). For a recent status Quæstionis on the origins of Yhw(h) see (van Oorschot and Witte 2017). |

| 3 | According to their own description of the temple, it contained stone pillars: at least five carved stone gateways with bronze hinges, a cedarwood roof, and woodwork. |

| 4 | The dictionary definition is “the amalgamation or attempted amalgamation of different religions, cultures, or schools of thought”. (Soanes and Stevenson 2004). |

| 5 | See also (Dupont-Sommer 1947, p. 185). A similar expression was found in Letter 3 from Lachish Letter 3:9 חיהוה. |

| 6 | Lindenberger (2001) proposed that the description of the demise of Vidranga, the (in-)famous governor of Upper Egypt at the time of the destruction of the Yahwistic temple at Elephantine (410 BCE), which is described in the petitions for help in restoring the temple (Porten and Yardeni 1986, A4.7, A4.8) was a quote of a curse-text or a prayer recited by the Yahwists against this man. However, the main problem, which I consider fatal to his argument, is that his entire analysis hinges on interpreting the conjunction zy as introducing direct speech (Lindenberger 2001, p 147). While this is common (=d′/dy) in Talmudic Aramaic and even found in Qumran, the use of zy as a conjunction introducing direct speech is practically non-existent in OfA. It is often still admissible to adopt later forms when none are recorded in OfA but the case of zy is on an entirely different scale. This conjunction is so common, so well-documented, and so central to OfA that the fact it is never used at the time for direct speech is striking (Muraoka and Porten 1998 and Folmer 1995 are very cautious with one possible and very tentative example each of such a theoretical case. (Pat-El 2012) notes that if this occurs in OfA at all, then it is only documented as kzy not zy). Yet, Lindenberger’s entire argument hinges on this conjunction since—in the context of being quoted in a letter—if it does not introduce direct speech, it is by definition not the content of a “curse” or a “prayer”. I think that based on the weight of evidence from OfA sources, which are practically unanimous on this point, the chances that zy here introduces direct speech, or that this is direct speech at all, are nil. Therefore, this cannot be seen as a curse or a prayer. I consider the description of what happened to Vidranga historical, though somewhat poetical and not entirely clear, and that Porten and Yardeni (1986, A3.9) refers back to the (in)famous Vidranga rather than a still living one. |

| 7 | Practically all of the treatment of this ostracon thus far has been limited to the fact that it mentioned Byt Yhh—the “house of Yhw”, with the tunic mentioned being seen as that of a priest or a secular member of the community. |

| 8 | Egyptian museum catalogue numbers: JE 49624, SR 7/21488, and SR 1/12416. The ostracon is currently kept in the Nubian museum in Aswan. |

| 9 | The stylus for this syntagm, Ꜥl Slwʾh, is noticeably sharper, making the letters visibly thinner than the rest of the text. This could be due to a number of reasons such as a different manner of holding the stylus (different hand), a change of stylus, or the sharpening of the stylus mid-writing. |

| 10 | (Grelot 1972, §90), note c, proposed a slight nuance here: “veille (à ou sur)”. See also in an epistolographic context, (Schwiderski 2013, pp. 171–72). |

| 11 | Cf. for example Targum Job 30:18 יזרזנני כתוני אגב כסותי אתבליש חילא בסוגעי. |

| 12 | A tunic is a garment that serves both sexes. See Gen 3: 21 where both sexes are clothed with a tunic. Consider also Tamar wearing a tunic in 2 Sam 13:18–19 as well as the “bride” in Song 5:3. This is also documented in a “Halakhic” text from Qumran known as 4QOrdinancesa: אשה כתונת ילבש ואל אשה בשלמות יכס (4Q159 2–4: 7). |

| 13 | The context of the text starting with “Behold my tunic”, supports the reading of šbqt as a sg. 1c. G-stem verb (“I left”). This cannot be a sg. 2m. “you”, given the sg. 2f address in imperative ʾamry (“say”) in line 3. Neither can this be a (defective) passive sg. 3f. form since the ktwn with the nisbe in line 1 is manifestly masculine (if it were seen as feminine, it would have been written as ktwnty rather than ktwny). There are a couple of cases of gender disagreement involving a ktwn, e.g., Porten and Yardeni (1986, A2 2:11) (Muraoka and Porten 1998, p. 278) but in most cases, the verb or adjective agrees with the noun. |

| 14 | These terms are usually used in discussions concerning the textual transmission of the Hebrew Bible. However, not every case of letter omission should be ascribed to these phenomena. A better term, in some cases, would be haplophony—the omission of a letter because of how it sounds—possibly because of dialectical or diachronic differences rather than copying errors. Cf. 1 Kings 7:48a: וַיַּ֣עַשׂ שְׁלֹמֹ֔ה אֵ֚ת כָּל־הַכֵּלִ֔ים אֲשֶׁ֖ר בֵּ֣ית יְהוָ֑ה. |

| 15 | See also discussion in (Kraeling 1953, pp. 96–97) where he considers the first byt as “a construct before the compound ‘house-of-Yahoh.’ The latter was the designation of the temple as a whole, while the first is ‘the house’ in the narrower sense of the adyton, or ‘Holy of Holies.’”. |

| 16 | There is also no possibility of reading byt as “between” here since this preposition must refer to two objects (=between X and Y) or a plurality (=between the Xs), which is not the case here. The reading of the verb bwt (“to spend the night”) must also be rejected since it cannot fit the grammar of the clause or the context. |

| 17 | At Elephantine, it is mentioned in Porten and Yardeni (1986, A3 3: 1 D4 9: 1). There are well over three hundred mentions of this syntagm. |

| 18 | If this is a list of names, it would be the only clear defective writing of this PN. |

| 19 | The conjunctive waw was proposed by Porten and Yardeni in their edition but neither Aimé-Giron nor Dupont-Sommer considered this to be the case. Both read this as a volitive without a conjunction. The former considered the first word of this line to be ירמה and the latter [י[ח̇רמה. |

| 20 | The reading of a ḥet, as first suggested by Dupont-Sommer, is practically certain here for a number of reasons. The mark below the first trace of ink on the righthand side of this line is not ink but a damage mark and thus cannot be a yod (unless the second stroke is exceptionally low and was entirely lost to damage). This is visible by careful examination of Aimé-Giron’s photo (Figure 1); I was able to confirm it via recent color photos I was privileged enough to examine during a recent trip to Egypt in June 2023. Unfortunately, for geo-political reasons, I was not given the authorization to publish these photos. Regrettably, Yardeni’s sketch of this ostracon in (Porten and Yardeni 1999, D7.18), presents the damage mark as a thick trace of ink which, as can be seen when compared with Figure 1 (and more so with the color photos) is misleading. The trace fits the top of a ḥet as seen in the first letter of ḥzw at the top of the ostracon. Other options, such as a Zain, a nun, or arguably a bet followed by rm (i.e., zrm, nrm, brm) are either non-existent, do not fit the context, or are very late and esotric. |

| 21 | The epigraphic possibility that this might be a different verb where the resh is to be read as a dalet (such as ydmh) has rightly been rejected by previous scholars and cannot fit any interpretation of the context. |

| 22 | I thank Dr. Theo Beers for this reference. |

| 23 | Most recently, Díez Herrera (2023) proposed a non-cultic interpretation of this ostracon, suggesting that similarly to large temples in ancient Mesopotamia, such as Ebabbar, the tunic mentioned might have alluded to the existence of a textile production function at the Elephantine temple. This hypothesis, which the author admits is “not unquestionable”, finds no support in the record. |

| 24 | Curses with attention to poetic charateristics such as meter appear in Greek cruse texts—even to the point of forcing the text to fit the overarching meter (Lamont 2023, pp. 197–98). |

| 25 | Cf. Lev 27:29 כָּל־חֵ֗רֶם אֲשֶׁ֧ר יָחֳרַ֛ם מִן־הָאָדָ֖ם לֹ֣א יִפָּדֶ֑ה (καὶ πᾶν, ὃ ἐὰν ἀνατεθῇ ἀπὸ τῶν ἀνθρώπων, οὐ λυτρωθήσεται) and Ezra 10:8/1 Esd 9:4 רכושׁו כל יחרם והזקנים השׂרים כעצת הימים לשׁלשׁת יבוא לא אשׁר וכל (καὶ ὅσοι ἐὰν μὴ ἀπαντήσωσιν ἐν δυσὶν ἢ τρισὶν ἡμέραις κατὰ τὸ κρίμα τῶν προκαθημένων πρεσβυτέρων, ἀνιερωθήσονται τὰ κτήνη αὐτῶν). |

| 26 | It is impossible to know anything about this priestess’ titles and position in society from the short text of this ostracon and thus what might have been her connection to the role of a qadištu—known from Akkadian sources—or the Hebrew qdšh (e.g., Hos 4:14). For a recent study of these terms, see (DeGrado 2018). |

References

- Aharoni, Yohanan. 1968. Arad: Its Inscriptions and Temple. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 31: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimé-Giron, Noël. 1926. Trois ostraca araméens d’Éléphantine. Annales du Service des Antiquites de l’Égypte 26: 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Audollent, Auguste. 1904. Defixionum tabellae quotquot innotuerunt, tam in graecis Orientis quam in totius Occidentis partibus, praeter atticas in “Corpore inscriptionum atticarum” editas collegit, digessit, commentario instruxit et Facultati litterarum in Universate pariensi proposuit, ad doctoris gradum promovendus. Luteciae Parisiorum: A. Fontemoing. [Google Scholar]

- Ayad, Mariam F., ed. 2022. Women in Ancient Egypt: Revisiting Power, Agency, and Autonomy. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azzoni, Annalisa. 2013. The Private Lives of Women in Persian Egypt. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, Gad. 2021. Khnum Is against Us since Hananiah Has Been in Egypt: Yahwistic Reform and Identity in the Prism of Elephantine: 419–399 BCE. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, Gad. 2023a. The Migration of the Elephantine Yahwists under Amasis II. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 82: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, Gad. 2023b. Interpretatio Ivdaica in the Achaemenid Period. Journal of Ancient Judaism 14: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, Gad, and Reinhard Kratz, eds. Forthcoming. Yahwism under the Achaemenid Empire, Prof. Shaul Shaked in Memoriam. BZAW. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Barnea, Gad. Forthcoming. The impact of Achaemenid Zoroastrianism on the Yahwistic community at Elephantine. In Yahwism under the Achaemenid Empire, Prof. Shaul Shaked in Memoriam. Edited by Gad Barnea and Reinhard G. Kratz. BZAW. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Becking, Bob. 2020. Identity in Persian Egypt: The Fate of the Yehudite Community of Elephantine. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, Collin. 2016. Cult Statuary in the Judean Temple at Yeb. Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period 47: 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGrado, Jessie. 2018. The qdesha in Hosea 4: 14: Putting the (Myth of the) Sacred Prostitute to Bed. Vetus Testamentum 68: 8–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez Herrera, Pablo Antonio. 2023. El Templo de Elefantina y Las Vestiduras Cultuales En El Ostracon Cairo EM 49624. Biblica 1: 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont-Sommer, André. 1946–1947. ‘Maison de Yahvé’ et vêtements sacrés à Éléphantine d’après un ostracon araméen du Musée du Caire. Journal Asiatique 235: 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont-Sommer, André. 1947. « Yahô » et « Yahô-Seba’ôt » sur des ostraca araméens inédits d’Éléphantine. Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres 91: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Jacob N. 1912. Jahu, AŠMbēthēl und ANTbēthēl. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 32: 139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Faraone, Christopher A. 2001. Ancient Greek Love Magic, 1st Harvard pbk. ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone, Christopher A. 2011. Curses, crime detection and conflict resolution at the festival of Demeter Thesmophoros. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 131: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, Christopher A., Brien Garnand, and Carolina López-Ruiz. 2005. Micah’s Mother (Judg. 17: 1–4) and a Curse from Carthage (KAI 89): Canaanite Precedents for Greek and Latin Curses against Thieves? Journal of Near Eastern Studies 64: 161–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, Margaretha L. 1995. The Aramaic Language in the Achaemenid Period: A Study in Linguistic Variation. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters en Dép. Oosterse Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, William Sherwood. 1914. Old Testament Parallels to Tabellae Defixionum. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 30: 111–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granerød, Gard. 2016. Dimensions of Yahwism in the Persian Period: Studies in the Religion and Society of the Judaean Community at Elephantine. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Grelot, Pierre. 1972. Documents araméens d’Égypte. Paris: Éditions du Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Helle, Sophus. 2014. Rhythm and Expression in Akkadian Poetry. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 104: 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, Tawny L. 2022. Papyrus Amherst 63 and the Arameans of Egypt: A Landscape of Cultural Nostalgia. In Elephantine in Context: Studies on the History, Religion and Literature of the Judeans in Persian Period Egypt. Edited by Bernd U. Schipper. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 323–51. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, Othmar, and Christoph Uehlinger. 1998. Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Kraeling, Emil G. 1953. The Brooklyn Museum Aramaic Papyri: New Documents of the Fifth Century B.C. from the Jewish Colony at Elephantine. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kratz, Reinhard Gregor. 2006. The Second Temple of Jeb and of Jerusalem. In Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period. Edited by Oded Lipschits and Manfred Oeming. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 247–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, Jessica L. 2023. In Blood and Ashes: Curse Tablets and Binding Spells in Ancient Greece. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire, André. 2006. New Aramaic Ostraca from Idumea Their Historical Interpretation. In Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period. Edited by Oded Lipschits and Manfred Oeming. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 413–56. [Google Scholar]

- Levene, Dan. 2014. Jewish Aramaic Curse Texts from Late-Antique Mesopotamia: “May These Curses Go out and Flee”. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger, James M. 2001. What ever happened to Vidranga? a Jewish liturgy of cursing from Elephantine. In The World of the Aramaeans III Studies in Language and Literature in Honour of Paul-Eugene Dion. Edited by John W. Wevers, P. M. Michèle Daviau and Michael Weigl. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 134–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lozachmeur, Hélène. 2006. La Collection Clermont-Ganneau: Ostraca, epigraphes sur jarre, etiquettes de bois. Paris: Diffusion de Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Magen, Yitzhak, Haggai Misgav, and Levana Tsfania-Zias. 2000. The Hebrew and Aramaic Inscriptions from Mt. Gerizim. Qadmoniot 33: 125–32. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Anthony. 2022. Naming God in Early Judaism: Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Muraoka, Takamitsu, and Bezalel Porten. 1998. A Grammar of Egyptian Aramaic. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, Joseph. 1970. The Development of the Aramaic Script. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Ornan, Tallay, and Oded Lipschits. 2020. The Lion Stamp Impressions from Judah: Typology, Distribution, Iconography, and Historical Implications. A Preliminary Report. Semitica 62: 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pat-El, Na’ama. 2012. Studies in the Historical Syntax of Aramaic. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porten, Bezalel. 1981. Structure and Chiasm in Aramaic Contracts and Letters. In Chiasmus in Antiquity: Structures, Analyses, Exegesis. Edited by John W. Welch. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg, pp. 169–82. [Google Scholar]

- Porten, Bezalel, and Ada Yardeni. 1986. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Porten, Bezalel, and Ada Yardeni. 1989. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Porten, Bezalel, and Ada Yardeni. 1993. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Porten, Bezalel, and Ada Yardeni. 1999. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmoser, Angela. 2014. Götter, Tempel und Kult der Judäo-Aramäer von Elephantine. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Saari, Sanna. 2020. Lions in Images and Narratives: Judges 14, 1 Kings 13: 11–32 and Daniel 6 in the Light of Near Eastern Iconography. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Schwiderski, Dirk. 2013. Epistolographische Elemente in den neuveröffentlichten aramäischen Ostrakonbriefen aus Elephantine (Sammlung Clermont-Ganneau). In In the Shadow of Bezalel. Aramaic, Biblical, and Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Bezalel Porten. Edited by Alejandro F. Botta. Leiden: Brill, pp. 159–82. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, Francisco Marco. 2021. Magical practice in sanctuary contexts. In Choosing Magic: Contexts, Objects, Meanings. The Archaeology of Instrumental Religion in the Latin West. Edited by Richard Gordon, Francisco Marco Simón and Marina Piranomonte. Rome: De Luca Editori d’Arte, pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Soanes, Catherine, and Angus Stevenson, eds. 2004. Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spronk, Klaas. 2022. Parallel Structures in Judges and the Formation of the Book. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 46.3: 306–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawn, Brent A. 2005. What Is Stronger than a Lion?: Leonine Image and Metaphor in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Fribourg: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- van der Toorn, Karel. 2019. Becoming Diaspora Jews: Behind the Story of Elephantine. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Oorschot, Jürgen, and Markus Witte, eds. 2017. The Origins of Yahwism. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Vance, Donald R. 2000. The Question of Meter in Biblical Hebrew Poetry, 1st ed. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Versnel, Henk S. 1991. Beyond Cursing: The Appeal to Justice in Judicial Prayers. In Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion. Edited by Christopher A. Faraone and Dirk Obbink. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 60–106. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, Albert. 1937. La Religion des Judeo-Arameens d’Elephantine. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barnea, G. Justice at the House of Yhw(h): An Early Yahwistic Defixio in Furem. Religions 2023, 14, 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101324

Barnea G. Justice at the House of Yhw(h): An Early Yahwistic Defixio in Furem. Religions. 2023; 14(10):1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101324

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarnea, Gad. 2023. "Justice at the House of Yhw(h): An Early Yahwistic Defixio in Furem" Religions 14, no. 10: 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101324

APA StyleBarnea, G. (2023). Justice at the House of Yhw(h): An Early Yahwistic Defixio in Furem. Religions, 14(10), 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101324