Abstract

Recent research into Arabic learning at Australian Islamic schools presented evidence of non-Arab Muslim learners’ dissatisfaction with Arabic learning. This article explores the Arabic learning experiences of non-Arab Muslim learners of Arabic (a-MLA) at Australian Islamic schools (AIS). This research gave voice to students and used a basic interpretive qualitative approach. Semi-structured interviews were triangulated using supplementary classroom observations. The data presented draw from the analysis of 40 participants’ interviews. Findings suggest that students expected learning to yield the acquisition of all language macro-skills and a capacity to read with comprehension, but that experiences and outcomes fell short of expectations. This led to disengagement, disruptions, and overall disillusionment and attrition in senior secondary. Students revealed a general dissatisfaction with the way programs were structured and with core aspects of their learning experience. Repetitive lessons focused on reading, translating and grammar study were connected to disruptions. The motivational implications of these negative learning experiences are discussed.

1. Introduction

Muslim communities have been learning Arabic for centuries because the Holy Qur’an is “a Scripture whose verses are made distinct as a Qur’an in Arabic for people who understand” (Sura 41: Verse 3. Haleem 2005, p. 307). Muslims protected the Qur’an as well as promoted and preserved Arabic. For instance, the second Caliph Umar (d. 644 CE) decreed that no one could instruct Qur’an recitation unless they were well-versed in Arabic, and the fourth Caliph Ali Ibn Abi Talib (d. 661 CE) encouraged the codification of Arabic grammar (Selim 2018b). Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328 CE) deemed Arabic learning a religious obligation and believed that language influenced “cognition, mannerisms and religiosity” thus articulating the interconnections between language, culture, identity, and worldview (Selim 2018b, pp. 81–82). It is, therefore, easy to appreciate why many contemporary Muslims living in various parts of the world invest in Arabic learning opportunities for their children.

Many Australian Muslims wanted their children to learn the language of their faith. In fact, like Jews and Christians, Australian Muslims wanted an alternative to secular public education for their children (Clyne 2001). Australian Islamic Schools (AIS) emerged to fill this gap. The first pioneering schools were established in the 1980s (Abdullah 2018). They provided spaces for Muslim children to be educated while learning about Islam and practising it (Ali 2018). These non-governmental providers of mainstream primary and secondary education fall under the umbrella of Australian independent schools.1 They follow state or territory regulations, participate in national testing, and provide annual reports (Independent Schools Australia 2022b, 2022c). State education departments monitor the schools to ensure that standards are maintained, and AIS receive government subsidies (Saeed 2004, p. 56). It is the practice of Islam, the teaching of the Qur’an, and the teaching of Arabic that distinguish AIS (Clyne 2001).

The number of AIS has grown quite rapidly. Jones (2012) explained that in “1997, there were fifteen Islamic schools in Australia” but that by “2008 that number had doubled, with a total of 15,938 students attending Islamic schools” (p. 40). Presently, the annual snapshot published by Independent Schools Australia (2022a), suggests that there are 49 schools and 43,906 students attending them. The growth in school numbers inspired research focused on the sector. Researchers examined the establishment of AIS (Ali 2018); presented sector-relevant frameworks (Abdullah et al. 2015; Abdullah 2018; Brooks and Mutohar 2018); explored Islamic studies (Abdalla 2018; Abdalla et al. 2020, 2022; Selim 2018b) as well as governance (Succarie et al. 2018). However, Selim and Abdalla (2022) explained that “research focused on Arabic language learning in the AIS context remains scarce” (p. 2). The following section will discuss what we have learned about Arabic learning at AIS.

1.1. Arabic at Australian Islamic Schools

Campbell et al. (1993) produced the most substantial report on Arabic learning in Australian schools. In it, they provided some basic information about a few AIS operating in Victoria and New South Wales (NSW) at the time. They mentioned the schools’ names and provided totals of student and teacher numbers. The report also included a few brief statements about why some schools launched their Arabic programs. The Al-Noori Islamic school introduced their Arabic program in 1983 because “a sound understanding of Islam rests on the knowledge of Arabic” (Campbell et al. 1993, p. 4), while the Malek Fahd school, taught Arabic for religious and cultural reasons (Campbell et al. 1993). Beyond the valuable insights into the schools’ motives, Campbell et al. (1993) shed light on some information about the sector in its early years. However, the relevance of this information almost three decades later is greatly reduced.

Great insights emerged in the research Jones (2013) undertook for his PhD. He analysed what was taught in faith units, whether the ‘hidden curriculum’ reflected an Islamic ethos, and addressed the accusations that AIS created ghettos that isolated young Muslims from Australian society (Selim and Abdalla 2022, p. 3). Jones (2013) interviewed teachers and alumni. Though not focused on Arabic, his research highlighted that AIS taught Arabic as the language of the Qur’an (p. 68), that they taught it for 2 h a week from Years 1–10 and that they focused on the script and basic words in primary (Jones 2013). He reported that students “really struggled and got little or nothing out of attending Arabic” (Jones 2013, p. 117). He also noted that most students felt that pursuing Arabic learning in Years 11–12 was pointless. His work suggested that non-Arab students were less satisfied with their learning, which underscored a need for research focused on Arabic learning by non-Arab students enrolled at AIS.

Given research recommendations to focus on non-Arab learners of Arabic in Islamic schools (Selim 2019), and building on Jones’ work, Selim and Abdalla (2022) explored the motivation and engagement of adolescent non-Arab Muslim learners of Arabic (a-MLA) at AIS using the L2 Motivational Self System (Dörnyei 2005, 2009, 2019) as a primary theoretical lens.2 This model proposes two motivational future self-guides (the ideal L2 self and the ought-to L2 self), as well as a third component focused on the language learning experience (L2LE). Students were generally interested in learning Arabic for religious reasons. The research identified seven religious orientations to Arabic learning: enlightenment, sacred text, ritual, obligation, transmission, and afterlife. A pervasive interest in reading and understanding the Qur’an constituted the sacred text orientation. A minority of students had five additional interests: language/culture, travel, friendship, instrumental, and recognition. Students’ motivational orientations were aligned with the ought-to L2 self which captures the motivation to learn due to external pressures or a sense of obligation. However, the ought-to L2 self could not sustain these students’ motivation to learn Arabic. Disengagement was prevalent, and resistance was emergent. A-MLA were influenced by the perceived constraints and affordances of their L2LE, as well as other contextual influences, namely the primacy of English; future and academic planning; discouraging parental attitudes; and countercultures. These findings are significant because they highlight the complications and emerging tensions associated with faith language learning among adolescent non-Arab Muslims. As negative learning experiences were a key contributor to disengagement and resistance among a-MLA, this article will examine their Arabic learning experiences more closely.

1.2. The Theoretical Lens

The study draws on the L2 Motivational Self System (L2MSS) introduced by Dörnyei (2005, 2009, 2019) as a theoretical lens. The L2MSS includes three components: the ‘ideal L2 self’ (IL2S), the ‘ought-to L2 self’ (OL2S), and the L2 learning experience (L2LE).

The first two components are self-guides informed by the theories of ‘possible selves’ (Markus and Nurius 1986) and ‘self-discrepancy’ (Higgins 1987). The IL2S represents the L2 aspects of the ideal self that we aspire to acquire (Dörnyei et al. 2006); and the OL2S represents attributes one believes they ought to possess (e.g., duties, obligations, responsibilities) (Dörnyei 2005). These selves can motivate learners to take action to minimise the discrepancy between the desired future self-image and the learners’ actual self (Dörnyei 2009; Higgins 1987). However, for a self to motivate it needs to be plausible from the learner’s perspective (Macintyre et al. 2009) and in harmony with their social environment (Dörnyei and Al-Hoorie 2017).

Researchers found that the two selves proposed by the L2MSS do not fully capture the realities of some learners, and proposed other possible L2 selves to capture learners’ agency and various contextual influences (Lanvers 2016; Macintyre et al. 2017; Selim and Abdalla 2022; Taylor 2013; Thompson 2017). For adolescents, the influence of contexts and interactions within them on the development and abandonment of possible selves is crucial (Oyserman et al. 2004; Roshandel and Hudley 2018). Therefore, it is acknowledged that motivation emerges from “relations between real persons, with particular social identities, and the unfolding cultural context of activity” (p. 215). Or in the case of a-MLA, several overlapping micro and macro contexts.

The third component of the model is the L2 learning experience (L2LE). The L2LE is conceptualised differently from the two ‘self’ components (Dörnyei 2009). It focuses on the executive motives related to aspects of the immediate learning experience (e.g., the teacher, curriculum, peers, sense of success) (Dörnyei 2010), positive learning history (Dörnyei 2005), and the enjoyable quality of a program (Dörnyei 2014). Dörnyei (2005) conceived of L2LE as a causal dimension concerned with “situation-specific motives related to the immediate learning environment and experience” (p. 106). He argued that research provided “evidence of the pervasive influence of executive motives related to the immediate learning environment and experience” (Dörnyei 2005, p. 106).

Recently, Dörnyei (2019) proposed defining L2LE in terms of learner engagement. In connection with this, it is acknowledged that engagement has internal (cognitive or emotional) and external (behavioural) dimensions (Sinatra et al. 2015). Additionally, the L2LE captures learners’ internal appraisals of past successes and failures (Ryan 2019), and as Csizér and Kálmán (2019) recognised, it can refer to concurrent perceptions and retrospective contemplation (p. 226). Furthermore, as Ushioda (2012) explained, when we explore motivation from an experiential perspective, theories like self-efficacy and attributions become relevant (p. 16).

This research is aligned with the third component of the L2MSS through its focus on Arabic language learning experiences. However, given the exploratory nature of this study, L2LE is defined in the broadest sense so students can describe any facets of L2LE they deem salient. As the L2MSS has some explanatory limitations, particularly in terms of adolescents learning a minority language within an English-dominant context (Selim and Abdalla 2022), the research remains flexible and open to other theories. Additionally, framing students as engaged or disengaged from the researchers’ perspective (Erickson and Shultz 1992) is minimised through a focus on students’ experiences and voices (Thiessen 2007).

1.3. Research Significance

This research contributes to the broader literature on L2 motivation, by examining the motivational impacts of L2 instruction (Csizér 2017) on a cohort of adolescent language learners’ motivation (Boo et al. 2015) to learn a language other than English (Dörnyei and Al-Hoorie 2017; Olsen 2017; Ushioda and Dörnyei 2017). This research adds to work focused on the L2LE (Csizér 2018), which has generally been eclipsed by the first two components of the L2MSS (Csizér 2019). However, unique in this study is its focus on these points with the learning of a faith language. Lepp-Kaethler and Dörnyei (2013) explained factors concerning faith and sacred texts have not been well-explored as motivational sources for language learning (p. 172). It can also be said that the demotivational implications of L2 instruction in connection with a faith language have not been adequately discussed.

This research also contributes to our understanding of Arabic learning and instruction in Australia and comparable multi-cultural English-dominant-Muslim-minority (EDMM) contexts (the UK and the USA).3 The need for expanding and diversifying research on Arabic learning and instruction is recognised (Alhawary 2018; Lo 2019; Ryding 2006, 2018a, 2018b; Selim and Abdalla 2022; Wahba et al. 2018) and has motivated some research focused on non-adult learners of Arabic (Berbeco 2011; Engman 2015; Labanieh 2019; Ramezanzadeh 2015, 2021; Selim and Abdalla 2022; Soliman and Khalil 2022; Temples 2010, 2013); with a few researchers drawing attention to the need for more research focused on Arabic learning and instruction in Islamic schools (Engman 2015; Selim and Abdalla 2022).

2. Research Questions and Aims

This is the second article reporting findings from a larger study focused on a-MLA learning Arabic at AIS. The study pursued answers to three research questions: (1) how do a-MLA make sense of Arabic learning; (2) what do they make of their language learning experiences; (3) and how do they want their language learning experiences improved? The first article explored students’ motivation and engagement. This article aims to identify (1) what a-MLA expect of their Arabic learning; (2) what their learning experiences are like; and (3) their reactions to learning experiences. The article will subsequently discuss the implications of these findings.

3. Methodology

This research used a basic interpretive qualitative approach (BIQA). This qualitative research approach has also been described as noncategorical, descriptive, inductive, or generic (Caelli et al. 2003; Kahlke 2014; Liu 2016; Merriam and Tisdell 2015). The BIQA design relied primarily on semi-structured interviews to solicit the learners’ perspectives. The interviews included a form-filling activity through which students outlined the languages they knew, self-assessed their skills in the listed languages, and ranked the listed languages according to importance. Self-assessments are subjective and unreliable as a measure of proficiency, and may contain inconsistencies, but can be used to serve certain purposes (Blanche 1988; Oscarson 1989; Papanthymou and Darra 2019; Ramezanzadeh 2015; Tina and Peter 2009). These self-assessments were used to position learners as experts on their own experiences and to gain insight into how they perceived their abilities. To achieve triangulation, the interviews were complemented by classroom observations. The classroom observations were loosely structured, and the researcher was a nonparticipant observer. The observations provided supplementary insights into observable aspects of engagement, learning, and classroom dynamics.

Following approval by the human research ethics committee, a two-phase pilot study refined the research instruments and techniques. The pilot data were not included in the data set. In the main data collection phase, interviews lasted around 40–45 min. With a few of the older girls, they lasted around 60 min, and with a few of the younger boys, they were slightly shorter than 30 min. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The data were analysed thematically. The NVivo software was used to help with analysis. The thematic analysis was not preoccupied with frequency counts, but with the contribution, an emergent theme makes to our overall understanding of the phenomenon in question. The data presented use words like “majority” or “some” to guide the reader. For readability and explanation, additional text is sometimes inserted into quotes and is shown in square brackets. Pauses (long or short) and shortened excerpts are indicated by an ellipsis.

3.1. Participants

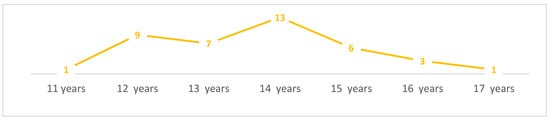

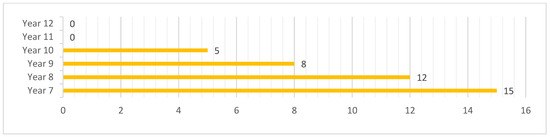

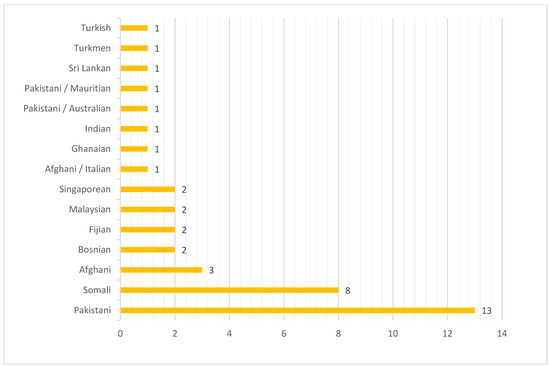

Information-rich participants were recruited using a purposive sampling approach (Lawrence 2014; Merriam 2009). This approach does not seek statistical generalisability but develops research-related criteria for participant selection (Merriam 2009). In this study, participants had to be non-Arab Muslims, in Years 7–12 at AIS. Being a non-Arab Muslim was defined in terms of access to spoken Arabic. Participants needed not to have access to spoken Arabic through one or both parents. Forty-nine (49) students volunteered, however, as nine participants did not meet the established selection criteria, only forty (40) participants’ data were analysed. The interview data of 18 males and 22 females were analysed. All participants were 11–17 years old and from diverse backgrounds. The majority were of Pakistani descent. Except for one student of Ghanaian descent who only used English, all participants reported using English alongside their home language/s. These included Urdu, Somali, Malay, Farsi, Dari, Turkish, Bosnian, Hindko, Italian, Punjabi, Sindi, Sinhala, and Tamil.

Figure 1.

The ages of the participants.

Figure 2.

The Year of study the participants were enrolled in.

Figure 3.

The diverse backgrounds of participants.

3.2. Research Sites

The participating schools were selected from larger and smaller Australian cities to gain a variety of perspectives and experiences. The pilot and main study data were collected from four comparable Islamic schools in three Australian state capitals: Brisbane, Melbourne, and Adelaide. The focus on state capitals was informed by statistics that show that the members of the Muslim community tend to reside in state capitals (Hassan and Lester 2018). Main study data were collected from three schools in Melbourne and Adelaide. Melbourne is home to a large Muslim community (Hassan and Lester 2018), with fewer Arabs than Sydney (Mazbouh-Moussa and Ohtsuka 2017). Adelaide is home to a small rapidly growing Muslim community (Hassan and Lester 2018).

All the schools taught a language in Years 7–9. Three offered Arabic only, and one offered Arabic and Turkish. Only one of the schools offered Arabic until Year 12. In terms of the variety of Arabic being offered, all the schools taught Modern Standard Arabic. However, they structured their programs in slightly different ways. For instance, two of the main study schools offered two 45 min lessons per week for a total of 90 min of Arabic learning per week in Years 7–9, while the other school offered one 75 min lesson per week for a total of 75 min of Arabic learning per week in Years 7–9. Table 1 shows more information about the research sites used in the main study, as well as the pilot study.

Table 1.

The main research sites.

4. Findings

This research yielded many rich findings about (1) students’ expectations; (2) program structure; (3) core learning experiences; as well as (4) students’ reactions to their learning experiences.

4.1. Expectations

Understanding L2 learning expectations provides insight into the benchmarks students use to assess their progress, quality of experiences, and outcomes (Tina and Peter 2009).

The overwhelming majority of a-MLA expected Arabic learning to yield the acquisition of all the Arabic macro-skills (reading, writing, speaking, and listening). For instance, a male student defined learning as “a combination of all things” and a female student said: “I feel like you have to have the whole, you know?” Several students described what they wanted out of their learning, for instance, a male student said: “I would like to learn everything about Arabic”. Some students perceived a connection between the skills, for instance, a female student explained that language skills are interdependent, saying that “without learning to read it, you won’t be able to speak it”, and another female student said: “knowing one skill isn’t gonna help you as much as knowing all of them”. A minority of students further emphasised effective communication as a goal. For instance, a male student said: “they’re all important. But, like, the thing is … I still need to progress on to the stage where I can actually speak it nicely myself, understanding the words, what I say and stuff”. He added: “I want to be able to, like, be one of those Arabs, you know, just talk naturally”.

In terms of reading, most learners’ expected reading would entail successfully decoding the script, reading text fluently, and understanding its meaning. For instance, according to a male student, reading is to “say them and understand them” and according to a female student defined reading is, “Arabic letters, and understanding what I’m reading, and everything!” Many students underscored comprehension as a critical outcome of learning to read. For instance, one female student said: “it’s not really reading if you can’t understand what you’re reading”, while another female student said, “there’s no point of me reading then if I don’t understand the text”. The students recognised the concept of liturgical literacy that is void of comprehension (Rosowsky 2006, 2008), but they wanted more than this. A male student said: “I don’t like it … I wanna learn. I want to understand it.” Many students compared their literacy goals to their actual progress. For instance, a male student said: “I want to read and understand … I can read some, and I can’t understand it”. Another female student: “I want to … translate stuff on my own, not the teacher translating it for me.”

From an instructional perspective, a female student believed oral skills should be introduced first. She said, “when I think of learning a language, I think of speaking and understanding it. Not more so reading and writing. That’s the next step.”

4.2. Program Structure

Three structural aspects of programs were salient in students’ discussions; (1) poor lesson allocations and timetabling; (2) incorrect language-level assessments; and (3) learning with Arabic-speaking peers.

4.2.1. Poor Lesson Allocations and Timetabling

Many students were dissatisfied with the number of lessons allocated to Arabic and with how they were timetabled. It was suggested that allocations were inadequate for meaningful language learning to take place. For instance, a male student said:

to be honest; you don’t really learn the whole language [because] it can’t be done at school. There’s not enough lessons … there’s not really enough time for Arabic.

He said that they took Arabic for 45 min twice a week,

you can’t learn like that! … If you come, and you don’t know any Arabic, [then] I think it’s impossible for you to leave, just from the school, knowing Arabic.

Likewise, a female student said,

Out of all, like, seven lessons a day, five days a week. We only have two lessons [out] of all those lessons!

4.2.2. Incorrect Language-Level Assessments

Where schools attempted to stream students, many felt that levels were incorrectly assessed. A female student said, “in Year 7, I struggled a lot … I don’t know why the teacher put me into the highest group … I didn’t understand a word they were saying”. Another female student in the intermediate level said: “I think I need to be in beginners”. A male student said: “I’m struggling hard … it would make sense for me to be in beginners”. Yet, another female student felt that the beginner level was pitched at a higher level than she expected, she said:

In Year 9, I went back to like, the beginners’ level where like they teach you simple stuff, like conversations and all that. So, that was a bit better. But like, I still feel like that was not ‘beginner’. Like, it was ‘beginner’ for Arab people, you hear me?

Where schools did not stream students, significant disparities were notable in the same class. A female student said:

some are fluent. They understand. They know how to speak, like, have a conversation [in] Arabic. Some of them just know how to read. And then, like, then there’s us, that like, don’t know that much about reading or speaking or any of that.

Another male student confirmed, “yes, three different levels”. He explained that:

some of them still don’t know their alphabets [whereas] some of them can speak Arabic like, fluently.

4.2.3. Learning with Arabic-Speaking Peers

Learning with Arabic-speaking peers was mostly seen as problematic. Many students perceived significant differences in ability between Arabic speakers and themselves. For instance, a male student said, “everyone can understand it, except me, because they’re Arabs”. These notions influenced self-efficacy beliefs. For instance, a female student said:

because I’m not Arabic-speaking, I find myself asking Arabic speakers, like, ‘can you help me out with this?’ … So, I think it is clear who’s higher than who…. Arabic speakers, obviously, are much better than me.

Another female student explained that learning with Arab peers was intimidating:

Every time the teacher talks, they translate it … when the teacher says, ‘do a sentence’, they will write it … like an English sentence for me. And, I’m there, still haven’t written my first sentence yet … Homework is really easy for them, while we take a while to understand it. So, it’s kind of intimidating.

Another male student felt that learning unfairly privileged Arabs, he said:

what kind of annoys me a bit [is that] sometimes, if I don’t do well, in that class like, they would do well … They’re more advanced. But like, if you think about it, they speak the language at home, so it’s like ten times easier.

Tragically for some students, these disparities can be distressing and result in the use of distanced self-talk. Distanced self-talk is sometimes used to regulate emotions when talking about negative experiences of varying levels of emotional intensity (Orvell et al. 2020). A male student described his class of 20 students, saying there are “three non-Arabs, including myself, and the rest are Arab”. Using distanced self-talk (indicated by a shift to third person pronouns), he added:

Non-Arabs, they don’t really take the learning seriously [because] they can’t learn it. Maybe, I think that it’s just too hard for them.

A small minority felt that sharing lessons with Arabs could be useful. For instance, a male student said, “if you need help like, you can just get [an] advanced student to come beside you and help you with some activities in the book”.

Interestingly a small minority felt that the differences between spoken dialects and Modern Standard Arabic (diglossia), reduced the head start Arab students might have. For instance, a female student explained that many Arabic speakers were in the beginner group because:

they don’t know how to write or speak [and if] they can speak it, they just don’t know fuS-ḥa Arabic [Modern Standard Arabic], they speak slang.4

4.3. The Core Learning Experiences

Learners described their experiences in detail. The essence of their experiences is outlined in a sequence of subsections detailing (1) accounts of typical lessons; (2) the nature of prescribed readings; (3) the lack of activities and resources; (4) lenient or problematic assessments; and (5) disrupted learning.

4.3.1. Accounts of Typical Lessons

Firstly, an overwhelming majority described lessons predominantly focused on reading, writing and translation. For instance, a male student said, “[he] gives us like booklets, and then we normally … read that, and then we translate it together.” Another female student said:

every student gets to read a sentence out [from] the booklet yeah? And then the teacher like word by word, she starts like explaining what it means. And then we write it down.

Secondly, some students described an emphasis on grammar, vocabulary, and spelling. A female student explained:

let’s say I have a sentence of ‘she was walking to the park’. Like, she would like, tell us each word, if it’s like, a noun, [or] a verb, how you use it in different sentences for male, [or] for a female. And then we would like, she would make us … make our own sentences using those words. And then she’d explain the sentence to us and how to use it in … our paragraphs. Stuff like that, and yeah. And we would learn, like, the meaning of the word, and the origin of the word, and a word similar to it, and stuff like that.

Another female student said, the teacher will:

read at least one or two lines, then she will translate it back to English, and where she thinks that we should know about this word, vocabulary, or grammar, she will point it out.

Students also indicated that they were not learning well this way. A female student elaborated,

So, she gives us the booklets, and then she tells us to read. … like, half of us don’t know how to read. So, she starts reading herself. And then, she starts writing what she’s reading on the board and explaining what it is. But no one really understands, and she’ll be like, ‘this is’, I don’t know, ‘feminine words thing’. And we don’t really understand what that means!

4.3.2. The Nature of Prescribed Readings

Students described the nature of their prescribed texts. These were provided in two formats depending on the school in question.

- Booklets.

A male student said they, “get booklets … this thick [gestures] … I don’t know. 10 sheets, 20 sheets, like that” and a female student explained, “they print it off textbooks … they give us the black and white [copies], but then during the lesson, our teacher, he puts the coloured image on the board.” However, the students found the content irrelevant. For instance, a female student said, “it’s just random stuff”, and another female student elaborated:

it doesn’t relate to you. You’d learn the conversation. You’d learn … how to order food. But like, you wouldn’t really do that … Like buying and selling things, or like ordering food, that could be helpful, but you wouldn’t remember it. Like you want to learn something that you remember like later on.

Another female student provides greater depth by suggesting that the content of readings does not cater to religious interests. She said,

I feel like they don’t teach…using the Qur’an and the words in it. … I feel they just teach you, it’s like only one part of it. Like, just to speak it and read it, but not like the way the Qur’an is like, read and written.

A few students found the process unstructured. For instance, a female student said, “it feels like everything is, jumbled up, especially studying for exams for Arabic exams or tests. It’s just … It makes me grow white hair on my head.” Others found keeping track of all the sheets cumbersome. For instance, a female student said, “I would always lose those booklets, and I would never be able to find them. So, I would always be so annoyed.” Additionally, some found using such worksheets ineffective.

A female student said:

I don’t feel like worksheets help me. I feel like practising, like, separate words help. ‘Cause, I get so confused in Arabic, like, putting sentences ‘cause it’s all jumbled up.

Finally, many found the readings too difficult and relied on the teacher’s translations. For instance, a female student said, “[the] lesson is 45 min, and as I said, half of it goes towards our translating the words and translating the questions.”

- 2.

- Textbooks.

One school prescribed a textbook called: Ta-’al-lam Al-‘Arabiy-yah [Learn Arabic: ICO]. The series was considered hard. A male student said, “It’s a good textbook. You will learn from it. But I reckon it’s too hard for our level, to be honest.” Another male student focused on the plain nature of the textbook, saying “they’re not really interactive books. They’re just like plain old textbook[s].” The students knew that the books were printed overseas. For instance, a male student said, “the books that we have, for example, this one [shows the book]. We actually researched it. They’re, they’re from Saudi Arabia.” Another male student had mixed views of the book:

It says a number one on them. They show us that it’s the first book. It’s beginner. So, maybe next year we might have different books, I hope. Yeah, I don’t like pink! … Like, the teacher grabs information from the book to teach us in class. And technically, without the books, we’d be like, doomed all right!

4.3.3. Lack of Activities and Resources

Students described learning as lacking in supplemental resources, activities, and collaboration. For instance, a female student said that beyond the reading and translation, “we don’t do any other activities or anything”, and a male student said, “No pair work. No fun games. No presentations. He doesn’t even prepare slides!” Another female student said the teacher provided, “just verbal explanation, sometimes on the board, but not videos and PowerPoints and stuff.” Another female student hinted at a lack of preparation saying, “We don’t, really, play games, and she doesn’t, really, have a PowerPoint. She will just say it on the spot.” Another male student said, “two terms ago, we had a conversation, that you would speak conversation, between you and a partner.”

Unfortunately, the aim of occasional supplementary resources or activities was sometimes lost on students. A female student explained,

We had to watch this Arabic video [and] explain the difference … [there are] many kinds of Arab people, apparently. And we needed to find the difference of the speaking and the difference of Arabic people. But I didn’t find the purpose of it … It was in English first of all, and secondly, watching the video, I couldn’t differentiate anything. But if there was [were] two videos [of] the same thing [but] different, you know, words, then I would have [understood]. ‘Cause like, I’m not an Arab I don’t understand anything that’s going on.

4.3.4. Lenient and Problematic Assessments

A few students explained that teachers ‘taught to the test’ or leniently assessed them. Some learners expressed surprise at their results. A male student said, “he, basically, gave the test from the book … He told us what’s gonna be on the test and memorise that and that’s all”. He emphasised, “he, basically, does the test in front of you on the board. And you take notes down like, everything … after like one week, he gives you the test and that’s it!” Another male student expressed surprise at his results, saying: “I don’t know, I don’t fail on the tests … I don’t understand why I got an A.”

A female student also elaborated on the problematic nature of assessments. She said:

We had a story, and it was in Arabic, and she said, ‘to learn this and the last paragraph, and we’ll do [them] on the test’. So, all I thought was, ‘I’ll just and try and memorise… [and] copy it down in the test’ … but it didn’t work out, because I didn’t know what I was writing, and the translation was on the paper, but I still didn’t know, and I got most of them wrong … during the tests … like, it’s in Arabic … she translates it for us, but it’s confusing.

4.3.5. Disrupted Learning

Students described often disrupted learning. A male student said in primary, “like, grade 3, grade 4 [Arabic lessons] were rowdy. Everyone was just reckless, and the teacher’s trying to get attention … Sometimes they spent the whole lesson trying to get attention.” However, secondary lessons were not much better. A female student said laughing: “I think you know the answer to that already. I’m gonna be straight out. Like, let’s be honest! There was a lot of mucking around!” A male student described unruly lessons in which “most of the students [were] yelling in Arabic”, and a female student alluded to the teacher’s futile effort to control the class, “some of them just start talking and laughing with each other, but then Ustaz [teacher] moves us. So, they still talk across the room.”

Several students complained that frequent disruptions compromised their learning. For instance, one male student said: “I couldn’t learn much ‘cause [there are] a lot of disruptions” and another male student said, “half the time, the people that wanna learn they don’t really get to learn because the teachers … are telling the other people off for being too noisy or disrupting the class.”

Students emphasised boredom and the apparent pointlessness of learning as the main causes of these disruptions. For instance, a male student reflected on himself and his peers, saying:

I’ll be middle disruptive if I was in class. ‘Cause I get bored a little bit … [His peers act up because] they find the subject boring so, they want to create some drama.

Another female student confirmed this, and included herself saying,

[We] don’t enjoy Arabic, but we just enjoy like, talking to one another.

Likewise, a male student explained,

I used to [be disruptive] ‘cause, I just felt like talking … I felt, as I wasn’t learning anything, there wasn’t any point of paying attention. Because I wasn’t learning anything, even when I was paying attention!

4.4. Students’ Reactions to Learning Experiences

Most students found their Arabic programs ineffective. A female student said: “I still haven’t learned anything” and a male student said: “I just don’t learn anything from it. Nothing!” Another male student reflected on classroom inefficiencies, saying: “I would be in that classroom for a week, and we don’t learn anything, to be honest … We didn’t learn anything”. Many students felt that their goals remained elusive. A female student said they were not taught language “you would use in your everyday conversations and stuff. So, it doesn’t really like, help me”. Others expressed disappointment, for instance, a male student said, “the Qur’an meaning, that’s the … main reason I’m doing Arabic. But I’m not getting anything out of it.” A female student said, “[learning] didn’t really direct me towards like, any other goals”. Additionally, negative experiences of learning appeared to foster ‘helplessness’ in some students. For instance, a female student disparaged herself, saying “every year I go dumber in Arabic, ‘cause I don’t understand” and a male student said that Arabic was “hard to learn ‘cause I do not understand it, and I don’t know how [to]”. Another male student said Arabic was: “hard because we don’t know how to learn it properly”. Interestingly, a male student also explained that “[Arabic is] simpler than English” [but] “I think the way it’s taught … makes it difficult for the students to learn”.

4.4.1. Disengagement or Resistance

Within this cohort of participants, disengagement was prevalent and resistance was emergent (Selim and Abdalla 2022). Disengagement, both internal and external, was captured in students’ statements about themselves and their peers (Selim and Abdalla 2022, pp. 11–12). Resistance emerged in a small minority of students and entailed a student explicitly stating at some point in the interview that they did not want to learn Arabic at all (Selim and Abdalla 2022).

4.4.2. Reactions to Lessons

An overwhelming majority of learners found lessons very boring. A male student said that “It gets boring, and then I just doze off sometimes” and a female student said, “so boring! She just talks the whole time! And like, we get so annoyed, so we like, start talking too and she gets angry”. Another female student emphasised, “Last year, the teacher was, like, beyond! … She would just stand there, and talk, and talk, and talk.” Another male student that they use, “just the book, it’s boring, [we] just have to keep reading off it”. Another male student said:

We haven’t done much of acting, role-plays, PowerPoints, we haven’t done much of any of those. It makes it, the lesson, if I could say, a bit boring [and] it doesn’t have that excitement of going to Arabic.

Another female student stressed the repetitive and ineffective nature of lessons.

she’s doing everything daily, like, the same thing, writing down, and just reading. So, I think they’re just like getting kind of bored of it; we’re not doing any activities like speaking to each other. [Lessons are] not really helping me with my learning. They help me learn little words, that’s basically all. We just learnt feminine [and] masculine words in Arabic. And I don’t understand it.

Another female student suggested that L2LE left students with mixed feelings about the subject:

I feel like, everyone has mixed feelings about Arabic, because they all wanna learn [but are like] what if I can’t do it?

4.4.3. Appraisals of teachers

A male student aptly said: “the teacher forms the class. If, if you have a good teacher, then you would have a good class. If you have a bad teacher, then you have a bad class”. The students revealed that they appraised their teachers’ teaching abilities (Table 2) and that they were also influenced by their perceptions of teachers’ approaches, attitudes, and personalities (Table 3). Students’ impressions of teachers were generally negative. However, one teacher (referred to here as Teacher X) was described positively.

Table 2.

Appraisal of teachers.

Table 3.

Perceptions of teachers’ approaches.

Teacher X

One teacher who taught a few boys in this cohort of participants was viewed favourably. Teacher X was a registered teacher with qualifications suited to the teaching of Arabic. Some of the registered teachers were prepared to teach other topics but were assigned Arabic teaching. Teacher X was perceived to be efficient, serious, professional, organised, and supportive. This teacher was said to use engaging activities like, Kahoot! quizzes as well as PowerPoint slides. Disruptions were minimal in this teacher’s classroom, according to students’ accounts and classroom observations.

About this teacher, one student said,

if you need help or anything, he will help you straight away! And he will tell you like how to do. And he’ll discuss it with you … he even finds time for us. Like … maybe a lunch session or a recess. And he says he’ll ‘come a few minutes’, ‘I’ll explain it to you’. Yeah, that’s what I like, Alḥamdulilah [praise be to God] … that’s making my Arabic better.

He added,

We stand up for him, already, and he greets us, we greet him. We sit down, he marks the roll, and we get into it. No yelling … so, we start in a good manner, not grumpy, like uhh, not yelling.

He also explained that this teacher did not belittle or shame students:

if you don’t understand anything, he will tell us to raise your hand, like, ‘so don’t, don’t be afraid to like raise your hand, say what you don’t understand’. So, I feel like confident, like putting my hand up, and I don’t feel ashamed or anything.

Another student explained that Teacher X,

is not the type of guy to like, joke around and stuff [rather teacher X] just walks in and starts doing stuff … I can tell he prepared the lessons pretty well. And then he, he taught it to us pretty well. And for those who tried to, you know, misbehave, they didn’t.

4.4.4. Perceptions of Ability

A self-assessment form-filling activity was part of the semi-structured interviews. Students gave themselves a score from 0 to 10. A score of 10 indicated the highest possible outcome. Averaged self-assessments provided insight into the overall mood and sense of self-efficacy among participants (see Table 4). The average overall score was 3.8, which suggests a generally poor perception of ability. Poor self-efficacy beliefs can lead to the abandonment of activities (Bandura 1983) or language learning (Dörnyei and Ushioda 2011), and the dropping of Arabic in Years 11–12.

Table 4.

Averaged self-assessments of Arabic skills.

4.4.5. Attrition in Senior Years

Negative learning experiences and poor acquisition outcomes contributed to students’ decisions to drop Arabic in Years 11–12, or as soon as Arabic was no longer compulsory.5 A male student felt Arabic was unlearnable at school, “whatever you do, like, as hard as you work at school, I don’t think you can come out learning Arabic.” Another female student said:

After a few lessons, I’m just like, ‘I’m never gonna learn this language!’, ‘It’s gonna be so hard for me to learn it!’, ‘There’s so much to do!’ and I just kind of gave up.

A male student explained:

I don’t know if it’s the way they taught it to me, that I started to not like it … I kind of got bored of it. So, why do I want to keep doing it when I have the choice to stop? … Many of my mates dropped it. Not many of my mates, everyone!

Additionally, students felt that pursuing Arabic as a matriculation subject was ill-advised. For instance, a female student explained that “I was like, ‘I’m not learning that much, and if I continue with it in Year 10, I’m gonna have to do the VCE6 [in Arabic]. I’m already poor in it, and I don’t want to do VCE’…”

Except for one Year 9 girl, all the students interviewed from Years 9 and 10, had either dropped Arabic or intended to do so. As for this girl, she mentioned that she selected Arabic as an elective but that the course had not been offered due to low selections.

5. Discussion

The findings revealed that students had conceptions of what Arabic learning should entail. The data also suggested that many a-MLA reflected on L2LE concurrently and retrospectively (Csizér and Kálmán 2019) and that they evaluated aspects of their immediate learning experiences, as well as internally, appraised past successes and failures (Ryan 2019). Students self-assessed their levels of proficiency poorly and indicated that overall L2LE were ineffectual and disappointing. L2LE disengaged learners and made some believe that Arabic was unlearnable (Selim and Abdalla 2022). L2LE reduced the perceived plausibility of acquiring Arabic . Students discontinued Arabic study in Years 11–12 (Jones 2013) because of poor self-efficacy beliefs, concerns that taking Arabic would be detrimental to their academic plans, and boredom. The following discussion will interpret the key findings and their implications.

5.1. Expectations

A-MLA wanted Arabic learning to build proficiency in all the macro-skills (listening, speaking, reading, writing) and to develop their capacity for reading with comprehension. This indicates that students wanted to ‘communicate’ and ‘understand’. These expectations appear consistent with the two organisational strands of the Australian languages curriculum: communicating and understanding (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority 2022). Conceptions of literacy are complex, evolving and socially constructed (Rintaningrum 2009), however, given these students’ overwhelming interest in reading and understanding the Qur’an (Selim and Abdalla 2022), ‘reading literacy’ is important. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) defines reading literacy as “understanding, using, evaluating, reflecting on and engaging with texts in order to achieve one’s goals, to develop one’s knowledge and potential, and to participate in society” (Mo 2019, p. 2). A-MLA wanted to engage with the Qur’anic text and understand it.

Some participants emphasised the desire to understand texts without relying on the teachers’ translations. This suggests a desire to be autonomous readers. There are no comprehensive definitions of autonomous reading (Huang 2019), but Ping (2011) explains that a reader’s ability “to read autonomously is evidenced by their use of particular reading strategies, as well as by the relationship between student and teacher during the reading task” (p. 74). Therefore, teachers of Arabic at Australian Islamic schools need to use instructional approaches that are likely to foster autonomy in Muslim learners of Arabic (Selim 2022), and develop their comprehension skills. This conception of Arabic literacy may conflict with some Muslim conceptions of literacy that do not emphasise comprehension (Selim 2017) or focus on ‘liturgical literacy’ for devotional purposes only (Rosowsky 2006, 2008). Liturgical literacy entails reading Arabic religious texts fluently but without comprehension of their content (Rosowsky 2019). Rather, the meaning of the texts is explained in the community language (Rosowsky 2008).

Most a-MLA participants expected Arabic learning to yield an ability to comprehend texts and deemed learning that did not produce comprehension ‘pointless’. This finding echoes Rosowsky’s (2008) observation “that liturgical literacy, on its own, will not fulfil the needs of the new generations of Muslim youth” (p. 221), in EDMM contexts. When learners’ expectations are not understood or managed, they can become barriers to learning (Bell 2005). This literacy gap can become a barrier because it creates dissonance. Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011) explained that in educational contexts dissonance “between the student’s own motivational goals and preferences (e.g., to develop communicative skills in a learner-centred environment) and the teacher’s instructional goals and methods (e.g., teacher-controlled drill and practice)” can lead to the emergence of resistance to learning (p. 147). With these participants, disengagement was prevalent and resistance was emergent (Selim and Abdalla 2022). The concern here is that if learners think that their lack of competence in the liturgical language impedes “active participation in the religion”, they might disidentify with the liturgical language (Jaspal and Coyle 2010, p. 29).

Interestingly, one student expected instruction to begin by focusing on listening and speaking skills, before reading and writing skills. This astute perception indicates that teaching a child to read a language they have not mastered speaking can have serious implications for their literacy trajectory (Hansen 2014). The need for having some communicative ability in the language one seeks to be literate in seems implicitly embedded in statements about needing to speak and understand the words one says. Several students’ statements suggest consciousness of the interdependence between skills and thus a more implicit expectation that learning will scaffold the acquisition and development of all skills. In connection with this point, it is worth noting that a small minority mentioned that differences between standard and spoken Arabic minimised the head start Arabic-background learners could have. This suggests that diglossia (Alsahafi 2016; Ferguson 1959) can challenge Australian Arab-background learners (Campbell et al. 1993; Selim 2019).

5.2. Experiences

Students discussed various structural aspects of Arabic learning programs. They generally found the time allocated to Arabic learning inadequate. Similarly, in a review of languages retention from middle to senior years in South Australia, Curnow et al. (2014) identified structural issues related to “when and for how long languages are taught at schools” and “timetabling against other subjects” (p. 28). The a-MLA attending Years 7–9 at the main study research sites, took 75 min (1 h and 15 min—one lesson)—90 min (1 h and 30 min—two lessons) of Arabic a week per week. This means that in an average school year of 40 weeks, the greatest amount of exposure to Arabic students might have is 60 h (about 80 lessons).7 The maximum number of hours that a student may have learning Arabic from Years 7 to 9 would be 180 h (or 240 lessons). The acquisition of decent proficiency in Arabic with this allocation, as students suggested, is unlikely. The literature suggests thatit takes adult native speakers of English between 480 and 2760 h to acquire Arabic proficiency levels between 0+ and 3+, respectively (Stevens 2006, p. 37). Such a disadvantage is amplified by other negative learning experiences.

Learners felt that their levels were poorly assessed, and a few suggested that beginner-level classes were pitched at too high a level. Students described significant differences in levels when they were not streamed by level. For instance, students who had not mastered the script shared classes with fluent readers and speakers. While a small minority saw a benefit in potential support from Arabic-speaking peers, many perceived disparities in abilities and found learning with Arabic speakers challenging. Some deemed learning ‘intimidating’. Struggling a-MLA doubted themselves, and anticipated failure or despaired of learning altogether. As Oyserman and Fryberg (2006) explained, the accumulation of failure feedback causes us to “give up on becoming those aspects of our desired selves that are too painful to keep striving for in the face of repeated failures” (p. 18). Taylor (2013) stated that the language-learning classroom “can be either a curse or a blessing for an adolescent’s emerging sense of self” (p. 2). For these a-MLA, the Arabic language classroom seemed to be more of a curse.

Discussions also revealed the impact teachers can have on students. Students reflected on their teachers concurrently and retrospectively. Teacher X had a positive impact, however, overwhelmingly teachers appeared to impact, or have impacted, a-MLA negatively. Language teaching methods, planning and control of classrooms were lacking. Teachers were generally perceived to be unsupportive, insensitive, uninvested and overly strict. Lessons focused on reading, translating, grammar and vocabulary suggest that aspects of the grammar-translation method (GTM) were used to teach Arabic.8 The GTM is not based on a particular theory of learning and is known to frustrate learners (Richards and Rodgers 2001). The overwhelming dislike for lessons corroborates suggestions that this approach is not suited to teaching children Arabic (Berbeco 2018; Selim 2018a). L2LE rarely involved the use of supplementary resources, audio-visual content, activities, conversations, or collaborative work. Additionally, teachers taught to the test and were too lenient in assessments. The literature explains that the (1) “teacher’s attitude towards the course or the material, including lack of enthusiasm, sloppy management and close-mindedness”; (2) “teacher’s personal relationship with the students, including a lack of caring, general belligerence, hypercriticism and patronage/favouritism”; and (3) the “nature of the classroom activities, including irrelevance, overload and repetitiveness” are key causes of demotivation (Dörnyei and Ushioda 2011, p. 143). Further to this, “both too much and too little control by the teacher was perceived to be demotivating, impacting negatively on students’ feelings, self-efficacy and sense of control” (Dörnyei and Ushioda 2011, p. 144).

Learning with booklets was very unstructured, however, more generally prescribed texts were deemed hard and irrelevant. The generally areligious nature of readings and learning troubled a few students. Statements like “the Qur’an meaning, that’s the … main reason I’m doing Arabic. But I’m not getting anything out of it” can mean that overall goals are not realised. However, they can also indicate that program content does not reflect learners’ interests. As Husseinali (2012) suggests, Muslim learners seek Islamic identity connectors and these need to “be given equal weight” in teaching (p. 109). The fact that Arabic materials were mostly secular, resonates with the findings about the secular nature of Arabic programs at Irish Muslim schools (Sai 2017). Reasons for this might transcend school boundaries. For instance, the Australian national curriculum for Arabic is pitched to Arab-background learners and caters for their cultural and linguistic needs (Selim 2019, 2022). This means that in addition to its difficulty, the content of the curriculum might not engage religiously oriented a-MLA (Selim 2022). In the USA, a study found that a young non-Arab Muslim learner found cultural Arabic learning content (e.g., famous Arabs) boring (Temples 2013).

Overall, L2LE were disengaging and demotivating. Students connected their boredom to their disruptive behaviours. The prominence of disruptions begs reflection. Disengaged or disruptive behaviours are often framed from the adult educator’s perspective as disinterest in learning (Kim 2010) or as misbehaviour (Harshman 2013). However, they could be a means of resistance used to communicate with their educators (Abowitz 2000; Kim 2010) around problems and inequalities (Abowitz 2000). These behaviours can be used in several ways. Firstly, as a self-defence mechanism so learners do not think of themselves as lacking in ability (Kim 2010). Failing because one did not study has a different impact on the self than failing despite having studied. Secondly, to demand meaningful instruction (Kim 2010). Students whose needs are systematically ignored in the classroom and curriculum, sometimes have no option but to react by acting out (Harshman 2013). Thirdly, to affirm self-agency and empowerment, whereby students might want to counterbalance what they perceive to be an oppressive context, an unfair teacher, or to find their voice (Kim 2010).

5.3. Implications

The current situation has various psychological and motivational implications. Repeated failures battered self-efficacy beliefs and self-worth in students. Self-efficacy relates to one’s belief that one possesses the ability to produce a specific outcome or deal with a prospective situation (Bandura 1983, 2006). Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011) explained that one’s efficacy beliefs determine the “choice of activities attempted, along with a level of aspiration, amount of effort exerted and persistence displayed” (p. 16). Due to the compulsory nature of learning in Years 7–9, students who did not believe they could learn Arabic or excel in the subject became disengaged. The concept of self-worth in this context relates to students’ desire to protect their sense of ability even at the expense of getting good grades (Covington 1992). School students’ self-worth is often tangled with their abilities (Covington 1992). This entanglement can lead students to intentionally “handicap themselves by not studying” because to try hard and then fail anyway reflects poorly on their ability (Covington 1992, p. 17). Poor self-efficacy beliefs also led students to drop Arabic.

The most alarming implication of these findings is that repeated failures have serious emotional impacts, as demonstrated by the emergence of distanced self-talk. A student identified themselves as one of three non-Arab students in the class using the ‘first person’ and then started speaking about non-Arab students’ challenges and disengagement in the ‘third person’. This strategy is used to increase one’s psychological distance from the negative experiences they are about to describe to reduce their emotional impact (Orvell et al. 2020). Orvell et al. (2020) listed seven types of worries that invite distanced self-talk. Three of these are relevant in the case of this student; (1) achievement, (2) appearance and self-worth, and (3) morality and religion (Orvell et al. 2020). The third concern suggests that the religious need to learn Arabic could create a sense of guilt or religious failure in students. This could have implications for learners’ connections with the language of their faith. This perhaps explains why students’ feelings about Arabic were mixed.

It is perhaps at this junction that the motivational implications of the gap between expectation and L2LE emerges. In the first article published from this data, Selim and Abdalla (2022) outlined that conceptualising Arabic learning motivation in terms of “possible selves with a tentative capacity to motivate is useful” (p. 17). Students’ motivational orientations mostly aligned with the Ought-to L2 Self but this self’s “motivational capacity was contingent upon perceptions of the affordances/constraints of the L2LE and the wider context/s within which a-MLA were embedded’ (p. 17). In the context of this article’s focus, data suggest that L2LE did not provide learners with strategies for the realisation of goals. Goals or strivings must be attached to specific strategies if they are to motivate learners (Oyserman et al. 2004). An ideal or ought-to L2 self must “contain strategies for both personal goal-focused action and for dealing and engaging with the social context in which the goal is to be achieved” (Oyserman et al. 2004, p. 133). That is, it should provide a clear roadmap that connects the actual self with the desired future self (Oyserman et al. 2004).

In a formal context of compulsory learning, such as schools, there is a need to assist students in developing strategies that facilitate the attainment of the possible L2 self. Current learning does not “direct” learners towards their goals. AIS programs imposed learning but the experiences they created suggest Arabic acquisition was extremely unlikely. It is, therefore, not surprising that amotivation emerged (Lucas et al. 2016). Deci and Ryan (1985) explained that when a context neither permits “self-determination nor competence” for a given behaviour, people become amotivated (p. 71). Amotivation is “characterised by alienation and helplessness, resulting from lack of choice and control over one’s actions” (Taylor 2013, p.12). Amotivated students are likely to be listless, helpless, depressed, and self-disparaging (Deci and Ryan 1985, p. 71). The hallmarks of learned helplessness were evident in the cohort and suggested that learners believed “that effort or self-responsibility cannot aid outcome” (Weiner 1972). In this state, “learners give up trying because they come to believe, often rightly so, that they have no control over their destiny” (Covington 1992, p. 48). Learned helplessness involves hopelessness and the “belief that no matter how hard or how well one tries, failure is the evitable outcome” (Covington 1992, p. 65).

6. Conclusions

This article is the second in a sequence of articles interrogating data from exploratory research focused on understanding adolescent non-Arab Muslim learners of Arabic (a-MLA) enrolled in Australian Islamic schools (AIS). This article provided the first in-depth examination of these students’ perspectives on learning Arabic in Islamic schools. The article identified (1) what a-MLA expected of their Arabic learning; (2) the nature of their L2LE; and (3) their reactions to their L2LE. It subsequently discussed the implications of these findings. Students expected Arabic learning to yield the acquisition of all Arabic skills and an ability to read independently with comprehension. However, the dissonance between learners’ expectations and experiences impacted a-MLA self-efficacy and self-worth and led to amotivation; learned helplessness; and the use of distanced self-talk. These findings suggest that L2LE greatly reduced the plausibility of acquiring Arabic. Reasons for this related to structural aspects of programs as well as core learning experiences. The overhaul of these negative learning experiences is necessary and urgent. Such learning experiences batter adolescent learners’ delicate psychologies. A continued failure to help non-Arab Muslim learners realise their Arabic learning and literacy goals could lead to alienation from the language and faith9.

Funding

This research paper draws on data generated in the context of PhD research. The PhD research was supported through a scholarship and a small research grant from the Centre for Islamic Thought and Education at the University of South Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the University of South Australia’s Human Research Ethics. Approval number 200067. Approval date 27 July 2017.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available for the public.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Sydney Southeast Asia Centre for the opportunity to work on this article at the early and mid-career researcher writing retreat of November 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | AIS are neither madrasas, that graduate specialists in Islamic sciences (Mabud 2018), nor are they after-hours community schools linked to mosques or community-run Islamic centres (Diallo and Lockyer 2016). |

| 2 | The acronym L2 is used to refer to learning a second language. In this article it is used to refer to the learning of a second or additional language. |

| 3 | EDMM contexts are characterised by their multiculturalism and the superdiversity of their Muslim minorities (Selim and Abdalla 2022), and an emphasis on English that could create language learning pressures for some Muslim families that potentially force them to choose between Arabic and their ethnic language (Sai 2017; Selim and Abdalla 2022; Temples 2013). |

| 4 | This is how students referred to dialects. |

| 5 | Arabic was compulsory from Years 7 to 9. |

| 6 | VCE is the Victorian Certificate of Education students in the state of Victoria receive upon the satisfactory completion of their secondary education. |

| 7 | (((90 min * 40 week = 3600 min)/60 min = 60 h)/0.75 [45/60] = 80 lessons). |

| 8 | GTM, as its name suggests, focuses on grammar and translation, and emphasises reading and writing, with “little or no systematic attention” being given to speaking and listening (Richards and Rodgers 1986, p. 6). Vocabulary selection tends to be based on the text and words are often taught through bilingual word lists (Richards and Rodgers 1986, p. 6). Additionally, the sentence is often the basic unit of teaching (Richards and Rodgers 1986, p. 6). |

| 9 | This research paper draws on data generated in the context of PhD research (Selim 2021). |

References

- Abdalla, Mohamad. 2018. Islamic studies in Islamic schools: Evidence-based renewal. In Islamic Schooling in the West: Pathways to Renewal. Edited by Mohamad Abdalla, Dylan Chown and Muhammad Abdullah. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 257–83. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, Mohamad, Dylan Chown, and Nadeem Memon. 2020. Islamic studies in Australian Islamic schools: Learner voice. Religions 11: 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, Mohamad, Dylan Chown, and Nadeem Memon. 2022. Islamic Studies in Australian Islamic Schools: Educator Voice. Journal of Religious Education 70: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Muhammad. 2018. A pedagogical framework for teacher discourse and practice in Islamic schools. In Islamic schooling in the West: Pathways to renewal. Edited by Mohamad Abdalla, Dylan Chown and Muhammad Abdullah. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 195–226. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, Muhammad, Mohamad Abdalla, and Robyn Jorgensen. 2015. Towards the formulation of a pedagogical framework for Islamic schools in Australia. Islam and Civilisational Renewal (ICR) 6: 509–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abowitz, Kathleen Knight. 2000. A pragmatist revisioning of resistance theory. American Educational Research Journal 37: 877–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawary, Mohammad T. 2018. Empirical directions in the future of Arabic second language acquisition and second language pedagogy. In Handbook for Arabic Language Teaching Professionals in the 21st Century. Edited by Kassem M. Wahba, Liz England and Zeinab A. Taha. New York: Routledge, pp. 408–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Jan A. 2018. Muslim schools in Australia: Development and transition. In Islamic schooling in the West: Pathways to Renewal. Edited by Mohamad Abdalla, Dylan Chown and Muhammad Abdullah. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 35–62. [Google Scholar]

- Alsahafi, Morad. 2016. Diglossia: An overview of the Arabic situation. International Journal of English Language and Linguistics Research 4: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. 2022. F-10 Curriculum Languages: Aims. Available online: https://australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/languages/aims/ (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Bandura, Albert. 1983. Self-efficacy determinants of anticipated fears and calamities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45: 464–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2006. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. Edited by Frank Pajares and Timothy C. Urdan. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing, pp. 307–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Christine. 2005. Managing learner’s expectations: Developing learner-centered approaches. Development and Learning in Organizations 19: 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbeco, Steven. 2011. Effects of Non-Linear Curriculum Design on Arabic Proficiency. Ph.D. thesis, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Berbeco, Steven. 2018. Teaching Arabic in elementary, middle and high school. In Handbook for Arabic Language Teaching Professionals in the 21st Century. Edited by Kassem Wahba, Liz England and Zeinab A. Taha. New York: Routledge, pp. 162–74. [Google Scholar]

- Blanche, Patrick. 1988. Self-assessment of foreign language skills: Implications for teachers and researchers. RELC Journal 19: 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, Zann, Zoltán Dörnyei, and Stephen Ryan. 2015. L2 motivation research 2005–2014: Understanding a publication surge and a changing landscape. System 55: 145–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Melanie C., and Agus Mutohar. 2018. Islamic school leadership: A conceptual framework. Journal of Educational Administration and History 50: 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caelli, Kate, Lynne Ray, and Judy Mill. 2003. ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Stuart, Bronwen Dyson, Sadika Karim, and Basima Rabie. 1993. Unlocking Australia’s Language Potential: Profiles of 9 Key Languages in Australia. Volume 1—Arabic. Canberra: National Languages and Literacy Institute of Australia Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, Irene D. 2001. Educating Muslim children in Australia. In Muslim Communities in Australia. Edited by Abdullah Saeed and Shahram Akbarzadeh. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, pp. 116–37. [Google Scholar]

- Covington, Martin V. 1992. Making the Grade: A Self-Worth Perspective on Motivation and School Reform. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Csizér, Kata. 2017. Motivation in the L2 classroom. In The Routledge Handbook of Instructed Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Shawn Loewen and Masatoshi Sato. New York: Routledge, pp. 418–32. [Google Scholar]

- Csizér, Kata. 2018. Some components of second language learning experiences: An interview study with English teachers in Hungary. In UPRT 2017: Empirical Studies in Applied Linguistics. Edited by Magdolna Lehmann, Réka Lugossy, Marianne Nikolov and Gábor Szabó. Pécs: University of Pécs, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Csizér, Kata. 2019. The L2 motivational self system. In The Palgrave Handbook of Motivation for Language Learning. Edited by Martin Lamb, Kata Csizér, Alastair Henry and Stephen Ryan. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Csizér, Kata, and Csaba Kálmán. 2019. A study of retrospective and concurrent foreign language learning experiences: A comparative interview study in Hungary. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9: 225–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnow, Timothy Jowan, Michelle Kohler, Anthony J. Liddicoat, and Kate Loechel. 2014. Review of Languages Retention from the Middle Years to the Senior Years of Schooling: Report to the South Australian Department for Education and Child Development. Adelaide: University of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Diallo, Ibrahima, and Keith Lockyer. 2016. The Role and Importance of Islamic Studies and Faith in Community Islamic Schools in Australia: A Case Study of Adelaide (SA) and Darwin (NT). Adelaide: University of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2009. The L2 motivational self system. In Motivation, language identity and the L2 self. Edited by Zoltán Dörnyei and Ema Ushioda. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2005. The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2010. Researching motivation: From integrativeness to the ideal L2 self. In Introducing Applied Linguistics: Concepts and Skills. Edited by Susan Hunston and David Oakey. London: Routledge, pp. 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2014. Future self-guides and vision. In The Impact of Self-Concept on Language Learning. Edited by Kata Csizér and Michael Magid. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2019. Towards a better understanding of the L2 learning experience, the Cinderella of the L2 motivational self system. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán, and Ali H. Al-Hoorie. 2017. The motivational foundation of learning languages other than global English: Theoretical issues and research directions. The Modern Language Journal 101: 455–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán, and Ema Ushioda. 2011. Teaching and Researching Motivation, 2nd ed. Edited by Christopher N. Candlin and David R. Hall. Applied Linguistics in Action Series; Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán, Kata Csizér, and Nóra Németh. 2006. Motivation, Language Attitudes and Globalisation: A Hungarian Perspective. Edited by David Singleton. Second Language Acquisition. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 1985. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior, 1st ed. Edited by Elliot Aronson. Perspectives in Social Psychology. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Engman, Mel. 2015. “Muslim-American identity acquisition”: Religious identity in an Arabic language classroom. Heritage Language Journal 12: 221–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, Frederick, and Jeffrey Shultz. 1992. Students’ experience of the curriculum. In Handbook of Research on Curriculum: A Project of the American Educational Research Association. Edited by Philip W. Jackson. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, pp. 465–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Charles A. 1959. Diglossia. Word 15: 325–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, M. A. Abdel. 2005. The Qur’an. Oxford: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Gunna Funder. 2014. Word recognition in Arabic: Approaching a language-specific reading model. In Handbook of Arabic Literacy: Insights and Perspectives. Edited by Elinor Saiegh-Haddad and R. Malatesha Joshi. New York: Springer, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Harshman, Jason R. 2013. Resistance theory. In Sociology of Education: An A-to-Z Guide. Edited by James Ainsworth. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 654–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Riaz, and Laurence Lester. 2018. Australian Muslims: The Challenge of Islamophobia and Social Distance. Adelaide: University of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E. Tory. 1987. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review 94: 319–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yi. 2019. The Application of Autonomous Reading in English Reading Classroom. Journal of Simulation 7: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Husseinali, Ghassan. 2012. Arabic heritage language learners: Motivation, expectations, competence, and engagement in learning Arabic. Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages 11: 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Schools Australia. 2022a. Independent Schools Snapshot 2022. Available online: https://isa.edu.au/snapshot-2022/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Independent Schools Australia. 2022b. Debunking Common Myths about Independent Schools. Available online: https://isa.edu.au/about-independent-schools/debunking-common-myths-independent-schools/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Independent Schools Australia. 2022c. Independent Schools Overview. Available online: https://isa.edu.au/about-independent-schools/about-independent-schools/independent-schools-overview/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Jaspal, Rusi, and Adrian Coyle. 2010. “Arabic is the language of the Muslims–that’s how it was supposed to be”: Exploring language and religious identity through reflective accounts from young British-born South Asians. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 13: 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Peter. 2012. Islamic schools in Australia. The La Trobe Journal 89: 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Peter. 2013. Islamic Schools in Australia: Muslims in Australia or Australian Muslims? Ph.D. thesis, University of New England, Armidale, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlke, Renate M. 2014. Generic qualitative approaches: Pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 13: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jeong-Hee. 2010. Understanding students resistance as a communicative act. Ethnography and Education 5: 261–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanieh, Khuloud. 2019. Heritage Language Learners of Arabic in Islamic Schools: Opportunities for Attaining Arabic Language Proficiency. Ph.D. thesis, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lanvers, Ursula. 2016. Lots of selves, some rebellious: Developing the self discrepancy model for language learners. System 60: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, Neuman W. 2014. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 7th ed. Pearson New International. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Lepp-Kaethler, Elfrieda, and Zoltán Dörnyei. 2013. The role of sacred texts in enhancing motivation and living the vision in second language acquisition. In Christian Faith and English Language Teaching and Learning: Research on the Interrelationship of Religion and ELT. Edited by Mary Shepard Wong, Carolyn Kristjansson and Zoltán Dörnyei. New York: Routledge, pp. 171–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Lisha. 2016. Using generic inductive approach in qualitative educational research: A case study analysis. Journal of Education and Learning 5: 129–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]