Abstract

Some contemporary social phenomena, despite secularization, are still linked to religion. However, this same secularization seems to have accompanied a progressive process of religious illiteracy. Therefore, the capacity to address religious inspired issues is lower than the magnitude of the problems at work, be violent right-wing movement and Islamist terrorism or ethical debates on the beginning and end of life, to name but a few. Hence, this paper aims to fulfil three goals: to revisit secularism and some liberal assumptions that might prevent a correct understanding of these phenomena, to assess some of the consequences of the critique of ideologies and to propose an alternative approach to address religious inspired social phenomena.

1. Introduction

Secularization theory which tried to explain the move from traditional to modern societies forecasted the end of religion. The pattern observed in Europe seemed to be that as societies became more modern, religion appeared to be more absent from public life. However, religions and religiosity did not disappear, as has been shown. For example, some analysis based on the World Values Survey and the European Social Survey (Kaufman et al. 2012) highlight the need to consider rates of religion change and demographics (i.e., migration, fertility rates, etc.) showing that, in some considered high secularized countries, figures on secularization have reached floor showing a shift in trends in religiosity now and in the upcoming years. However, not only that; many pressing challenges affecting both modern and traditional societies throughout the world are connected to religion and so require religious sensitivity in order to address them effectively: some forms of terrorism, religious inspired political parties, the ban of hijab in French schools, the use of religious language in public debates and political campaigns, and some right-wing movements, to name a few.

Despite that, the capacity to deal with religion has not grown accordingly for two reasons. First, modernization predictions on religion were taken for granted. If religion is going to disappear, why keep paying attention to it? The second reason has to do with the triumph of liberalism as the only framework for public debate and analysis (García-Magariño 2018). Its success has been so compelling that it is difficult to adopt a critical standpoint toward the values inherent to liberalism. This intellectual tradition emphasizes individual freedom and autonomy and tends to overlook the collective dynamics of social life. Religion is more than individual beliefs; it is a social phenomenon with a strong collective dimension (Berger 1974). Thus, liberalism might not be the best framework to approach religion and religiously inspired phenomena in all their complexity.

Within the context described above, this paper tries to achieve three interrelated goals: (a) to offer a perspective on how secularism and liberalism limit our capability to address religious inspired phenomena which are prevalent nowadays, (b) to define possible boundaries of the “critique of ideologies” applied to understand religion and (c) to propose an alternative approach to tackle religion and social issues related to it.

2. The Limits of Secularism and Liberalism

This section will address the following sequence of ideas: (a) secularization is not a linear, universal and inexorable process; (b) the very notion of secularization needs to be revise; (c) religion or at least religion linked social phenomena emerge in modernity and the liberal and secular framework make it difficult to address them.

2.1. Secularisation and Secularism

Secularization theory is part of a great sociological trend that tried to explain the different social phenomena linked to the movement from traditional, rural societies to modern, urban ones. Max Weber proposed that, as societies moved along that path, a citizen’s loyalty towards traditional religious institutions would progressively weaken (Weber [1905] 2012; Estruch 2015). When the interdisciplinary field of Development Studies1 emerged after the Second World War, this descriptive theory, however, became a prescription to “modernize” countries, as it was assumed that modernization would bring development and social progress automatically. Thus, secularization moved from being a social process that seemed to have occurred in several countries—especially European—, to a desirable outcome to be fostered through political and civil action.

In the American case, though, was considered a special one within the Western world, as it was one of the first and most modern countries, but its religious life was still very vibrant (Riesebrot 2014). Further, religious symbols, practices, narratives, references and collective rituals were introduced into the life of secular institutions such as laws, tribunals and National feasts (Sánchez-Bayón 2016b). In order to explain the apparently exceptional phenomenon of American society in relation to its people’s religiosity, the concept of American civil religion was devised, being a kind of fusion among Jewish, Catholic and Protestant traditions into a non-sectarian spiritual tradition that generates social cohesion (Bellah 1967; Sánchez-Bayón 2016a).

It was mentioned that secularization theory changed into a normative ideology. Scholars such as Berger, Habermas or Casanova did not make such a big claim. However, all of them agreed upon the idea that other theorists took the secularization for granted (Berger and Luckmann 1995; Casanova 1994, 2009b; Habermas 2011). Thus, important transformations at the level of people’s religiosity went unperceived. In this line, the problem was not only one of theoretical neglect—as a result of taking secularization for granted—but also methodological and empirically untenable. In the last years of his life, Berger recognized the need to abandon the secularization paradigm and replace it with new theoretical developments connected to the idea of pluralism (Berger 1999, 2012, 2014). Casanova (2019), for example, followed his steps in affirming that “global humanity is becoming simultaneously more religious and more secular, but in different types of regimes, different religious traditions and in different civilizations” (p. 41). This statement is connected to variations in religiosity across regions (Duplessy [1955] 1959). For example, the “majority of people in Sub Saharan Africa, in South Asia, in the Middle East and in the United States consider themselves more religious than before” while in the rest of the regions the trend is softly decreasing (Deneulin and Rakodi 2011, p. 47).

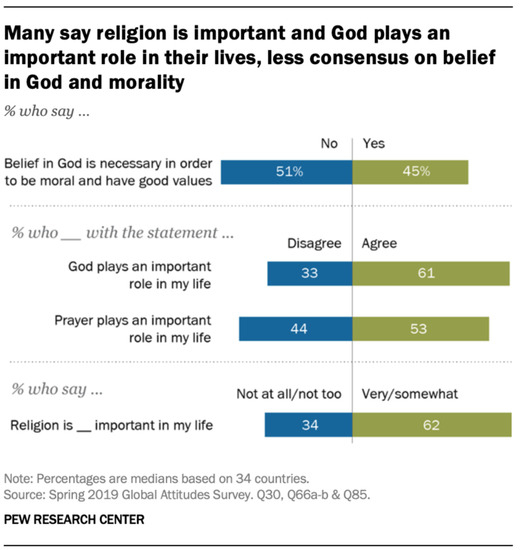

The Pew Research Center offers a good glimpse of these trends too. Pew’s analysis shows that the vast majority of people believe in God. In addition, the total number of people who believe in God is constantly increasing, but probably as a result of the planet’s increase in the total population. These estimates, though, are not definitive as it seems that, depending on the question asked, the responses could suggest other trends. However, it can be confidently said that religion is still present and plays an important role in the life of the population, as it can be seen in the following figure (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage on how religion and God plays an important role in the life of population. Source: Global Attitudes Survey (Pew Research Center 2019).

Nevertheless, how religiosity is experienced and manifested might not be exactly the same as in the past (Huntington 2002). There are new religious groups, there are new forms of spirituality and traditional religions which have evolved to incorporate new elements coming whether from spiritual or secular traditions (Díaz-Salazar et al. 1996).

Thus, secularization should not be taken for granted or, at least, naive notions of secularization should be overcome in order to open the path for more sophisticated theories. As Casanova (2009b), Joan Estruch (2015) and other scholars of the theory of secularization have posed, it should not be assumed that religion has turned into a private issue or a secularized set of sacred rituals: religion still has a collective imprint which aspires to contribute to facing the challenges of current global modern society.

The conceptualization of Western countries, especially the European ones, as “post-secular”—Habermas also includes Australia, Canada and New Zealand (Habermas 2009, p. 64)—, tries to capture the transformations taking place at the level of people’s religiosity (Berger 2012). However, the case of the United States, which was formerly considered the exception, seems to be the pattern: religion is not declining, indeed the global trend is that religion is growing—with the exception of European countries, where society is secularized but the persistence of religion in public life is still prevalent (Roldán Gómez 2017; Moghadam 2003; Pew Research Center 2017).

According to Berger (1999), the theory of secularization has two complementary dimensions. First: an institutional approach, as “the process by which sectors of society and culture are removed from the domination of religious institutions and symbols” (Berger 1967, p. 107). Additionally, second, at an individual level, the increasing number of people living “without the benefits of religious interpretations (Berger 1967, p. 108).

In a similar sense, Casanova (1994) distinguishes three different aspects/meanings. in the process of secularization: (1) the “decline of religious practices and beliefs in modern societies”, (2) the “privatization of religion”, and (3) the “distinction of secular spheres or emancipation of religious norms and institutions from them (state, science, economy)”. These three processes do not necessarily go the same path. The differentiation of spheres and the retreat of religion to the private realm does not necessarily imply a decrease of people religious belief (Casanova 1994; Taylor 2007). Furthermore, from the logic of functional differentiation just the contrary is to be expected: The purification of the religious from other elements that are alien to it could lead to a greater commitment to religiosity itself.

From this point, the three criteria commonly used to consider a society as “secular” are (a) the progressive differentiation of social spheres and, in particular, the separation between the State and the Church; (b) the replacement of magical thinking by technoscientific rationality and the achievement of technical progress; and (c) the reduction in society’s theological beliefs (Gómez 2017).

European societies seem to be the only ones which meet previous criteria but, despite that, religions in Europe still have an impact on public sphere, whether because of Jihadist terrorism and its use of modern technology or the Catholic Church’s efforts to influence public morality (Habermas 2009) or the demands of Islam for a place in the public space, and that is why they (European societies) deserve the term “post-secular”.

The question here should be, why has religion persisted in spite of the social theory based on secularization? Here is a tentative response.

At the level of the elites—comprising policy makers, international donors, heads of development banks, development scholars—during the second half of the twentieth century, a materialist conception of existence has been consolidated. This philosophy found expression in at least four visible spheres: historical materialism, capitalism, the emergence of the interdisciplinary field of Development Studies and postmodern consumerist society. However, the promises of these four trends, as the century came to the end, appeared unfulfilled.

First, the fall of the Soviet Union, together with the cruelties that occurred during certain communist regimes which had been hidden for decades, reduced the appeal of Communism and the confidence in the transformative utopia that it contained (Gershman 2000, p. 170). Second, global liberal capitalism did not bring the prosperity and social justice that it was supposed to; on the contrary, it widened the gap between the wealthiest and the poorest. The unfulfilled forecast of Fukuyama in “The end of history” (Fukuyama 1989) symbolizes this point.

Third, the promising enterprise of development, whose explicit purpose was to eradicate poverty, but which departed from the same materialistic assumptions, did not fulfil its goals and was not even able to instill in those whom the projects had to serve the motivation to participate in them (World Bank Group 2016).

Finally, as a result of the loss of confidence both in the possibility to change the world and in the very rational capacity to make universal rational statements, postmodern thinking paved the path for the conclusion that the only feasible proposal was to forget those aspirations and to focus on trying to be happy by travelling, enjoying cultures and, ultimately, by consuming (Harvey [1989] 1998). Given the prevalence of depression, anxiety, general sense of dissatisfaction and mental problems within the most consumerist societies (González et al. 2010, p. 3), it could be said that an existential vacuum seems to have pervaded many countries in the world.

In sum, global integration (Albrow 2012) and the breaking of the “materialistic enterprise” have stimulated a new search and interest in religion or at least in transcendental and “spiritual issues”. Some indicators of this renewed interest are (a) the number of publications, undergraduate and graduate programs in “religious studies” that appeared over the twenty-first century; (b) the upsurge of many conflicts connected to religion; (c) the concern with Islam and more particularly with political Islamism; (d) the proliferation of practices such as travels to India to visit certain “gurus”; the emergence of aboriginal rituals and group “experiences” in Western countries where ceremonies are held; (e) the use of drugs in search for “spiritual experiences”; (f) the renewal of the Interfaith international movement; (g) the connection between politics and religion in different countries; (h) the expansion of fundamentalisms of different kinds in different regions; (i) the appearance of new political movements in Europe which either have religious foundation or use slogans against specific religious groups; (j) the enhancement of awareness at the level of public institutions on the potential conflict of religious and cultural clashes when diversity is not correctly managed; to name a few (Díaz-Salazar et al. 1996, pp. 72–82).

In order to analyze the presence of the religious in our societies, it is useful to turn to Taylor’s characterization of the meaning of secularization (Taylor 2007). This means, along the same lines as Casanova and Berger, not only the emptying of the public sphere of any reference to transcendence (economy and politics have their own autonomous rationality), but also a decline in religious practices. However, Taylor adds and underlines a third, closely related, meaning: a secular society is one in which belief in God is not unquestioned but becomes one option among others. In other words, what is important is not belief or not, but the “conditions of belief”. In this sense, the return/remaining of religion is to be understood:

- (1)

- First, not as a moral imperative but as an individual choice, having given way therefore to a “pluralistic situation” (Berger 1967, p. 107). The return or permanence of religion is therefore necessarily plural.

- (2)

- Second, in a non-organisational way. Participation in traditional religious practices might have decreased, while maintaining relatively high levels of private individual belief. Consequently, we might talk of “unchurching of the European population and religious individualization, rather than secularization” (Casanova 2009b, p. 143). This non-institutional form of religion has been considered as a “believing without belonging” (Davie 1994).

- (3)

- At the same time, it is a “belonging without believing” (Hervieu-Lèger 2004). This is to say that religion remains in the collective memory, regardless of actual observance Religion remains in the collective memory, regardless of actual observance and regardless of its original transcendent meaning. These religions endure “as significant cultural systems and as imagined communities in competition with other imagined national communities” (Casanova 2004, p. 30).

- (4)

- As a “deprivatization of religion” (Casanova 2009b, p. 141), aiming for public recognition, especially of non-European religions, more specifically Islam, practiced by immigrant population.

What is equally surprising, as it was mentioned, is that the traditional channels of these transcendental impulses—organizational religion—are not being used. Moreover, new narratives, apparently secular but containing features of the “sacred ones”, such as the one that is going to be analyzed in the following section are being multiplied. In other words, the new search for meaning and spirituality, the new interest in religion, is not being channeled by the institutions that traditionally have been the focal point of this impulse towards transcendence. Some authors, such as Juan José Tamayo, interpret this new trend as a sign of democratization: spirituality is not the monopoly or religion anymore (Tamayo 2011). Others consider that this is a distortion of the spirit of religion and the consequence of religions not considering the requirements of the modern world (Bahá’í World Center 2005).

In any case, it might be said that modern—or highly industrialized—societies contain a sort of existential vacuum that was filled by religion in the past and that propels the constant production of sacred narratives (Philpott et al. 2011). This vacuum is related to Weber’s “disenchantment”, to Hartmut Rosa’s theory of resonance (Rosa 2019), to Joas’ explanation of why we need religion to strengthen values commitments (Joas 2008), and Madsen’s forecast of a potential new Axial Age (Madsen 2012). The upsurge of so-called Silicon Valley’s messianism will be interpreted under this lens. Some institutions discovered the use of religious claims to justify hidden agendas, eliminated all the positive effects of religion. For instance, its power to collectively identify “false idols” and to avoid the development of “transcendent” attachment to material objects such as money, race, nation, fame or power seems to have disappeared from society. Hence, it is extremely difficult to unmask secular movements with particular agendas but disguised with apparent pure motives (Grames 2011).

2.2. Liberalism

Another reason why social problems linked to religion are difficult to be fully understood is the assumption of the liberal framework as a neutral value framework.

For a characterization of liberalism as it relates to the topic proposed here, it is useful to draw on Gray’s (2000) distinction between the two faces of liberalism. (1) That which seeks an ideal way of life; (2) that which seeks a peaceful compromise between different ways of life. For the former, liberal institutions would be the application of universal principles (individual autonomy, secularism), for the latter, the means to achieve peaceful coexistence. For the former, liberalism prescribes a project of social organization around the individual rights of the citizen and aspires to a rational consensus in relation to liberal rights and values. For the second, liberalism is a project of coexistence that can be developed in different regimes. The first is the liberalism proposed by Locke, Kant and, more recently, by Rawls and Hayek. The second is that of Hobbes, Hume, Berlin and Oakeshott.

From the first form of liberalism, the diversity of ways of life, the pluralism of convictions about the good life is tolerated because it is destined to disappear. Or, at any rate, to be relegated to the private sphere. It is the predominance of this understanding of liberalism that makes it difficult to deal with religion. An example of this is embodied in French republicanism and its idea of secularism. France understands itself as a political project based on individual rights, which aspires to the emancipation of the individual from the dictates of any particular identity, such as religious identity, to assimilate republican universal values. This is the “tyranny of the secular, liberal majority” (Casanova 2009a, p. 147) based in the secularist teleological assumption built into theories of modernization that one set of norms is reactionary, fundamentalist and anti-modern, while the other set is progressive, liberal and modern” (Casanova 2009a, p. 147).

The republican project therefore demands the expulsion of religion from the public space (Portier 2018), that space of equality and universal rational consensus. Thus, the pressure for the privatization of religion, seen, not only as an institutional arrangement to achieve equality, but as an essential feature of Western self-understanding as a modern, secular society, makes it difficult to recognize any kind of role for religion in social life (Innerarity 2022).

This is the reason why the demands of Islam are perceived, not only as claims of a religion alien to Europe, but, above all, it is religiosity itself that is perceived as the otherness with respect to the secularity that defines us: the other of western liberal, secular modernity. This leads to an “Illiberal secularism”: the use of secularism as an argument to justify restrictions in religious freedom, such as the banning of the veil (Innerarity 2018).

MacIntyre, in the chapter of competing rationalities of Whose Justice? Whose rationality? (1988), posits that, since the Enlightenment, a tradition of inquiry has established its logic in public debate without making explicit its assumptions. Any kind of actor that enters the debate unconsciously assumes these logics (Garcés 2017). MacIntyre does not go against liberalism but tries to show that modern public debate seems to lack the capacity to establish rational dialogues about the assumptions underpinning different traditions and different notions of the common good.

One of the most striking facts about modern political orders is that they lack institutionalized forums within which these fundamental disagreements can be systematically explored and charted, let alone there being any attempt to made to resolve them. The facts of disagreement themselves frequently go unacknowledged, disguised by a rhetoric of consensus. And when on some single, if complex issue, as in the struggles over Vietnam war or in the debates over abortion, the illusion of consensus on questions of justice and practical rationality are for the moment fractured, the expression of radical disagreement is institutionalized in such a way as to abstract that single issue from those background contexts of different and incompatible beliefs from which such disagreements arise. This serves to prevent, so far as it is possible, debate extending to the fundamental principles which inform those background beliefs.(MacIntyre 1988, pp. 2–3)

MacIyntire finds the roots of this problem in the Enlightenment, as “the Enlightenment made us for the most part blind” (MacIntyre 1988, p. 4) to traditions and, so, proposes to recover the capacity to accept different traditions from which a rational debate on justice and other topics, that includes assumptions on what the common good is, may take place. Thus, liberalism was one the most important traditions that after that period became prevalent and established the logics, limits, language and possibilities of public debate (García-Magariño 2016d). Some of the premises that have been naturalized under the liberal approach, and that are addressed by both Gill (1992) and Martín-Lanas (2021)2, are the following:

- —

- Liberal partisan democracy is the best system of government.

- —

- The individual is the main entity of social life and political and civil individual rights are the key for progress.

- —

- The separation between the public and the private.

- —

- The relevance of the individual over the community and individual identity over collective identities, which are sometimes considered oppressive.

- —

- There has to be tension between institutions and citizens.

- —

- The notion of power as domination.

- —

- Economy as the axis of social life.

- —

- Competition as the articulation principle for social organization and as the key for excellence.

- —

- The split between religion and politics, faith and reason, mind and heart, rational and emotional.

In addition, there are other assumptions that, to be precise, are not part of liberalism but tend to go accompanying liberal democracies. Here are some examples:

- —

- Instrumental rationality as the highest form of rationality.

- —

- Economic growth as the key for social progress.

- —

- Nature as a resource to be exploded.

- —

- National interest as the main principle for international relationships.

A short clarification may be necessary before continuing with the strand. Previous set of notions linked to liberalism does not pay honor to such a rich, important and nuanced intellectual, political and economic trend coined under the category of liberalism. However, given that the purpose of this paper is not to elaborate on liberalism, but to underline certain contemporary trends associated with liberalism and secularism that might be preventing scholars and policy makers, first, to understand social phenomena linked to religion and, second, to approach those religious inspired issues effectively.

Once said that, nonetheless, it is recognized that different ideologies and religious groups come from other traditions of inquiry and depart from different assumptions. The case of the political dimension of Islam is paradigmatic in showing these tensions. The liberal interpretation of what should be done to integrate Islam in Europe, for instance, is related to the idea that Islam must experience a modernization process and renounce the political dimensions of its traditional theology. In this regard, the religious practice is seen to be deployed in the private sphere rather than in the public. Therefore, we have witnessed tensions and conflicts in recent decades on whether religious practices, rituals and symbols should be kept out of the public domain (García-Magariño 2016c) and what the role of the State is in the governance of religious diversity (Modood and Sealy 2022).

One significant case, for example, is the French law on secularity and conspicuous religious symbols in schools approved in 2004 banning the hijab as well as symbols from other religious communities. Another case in the opposite direction is Erdogan’s proposal to have a referendum for changing the Turkish Constitution on the right to wear the hijab in 2022. The point proposed here is that, as Peter L. Berger (2014) elucidated beyond the more personal question “how can I be a Muslim and a modern person” there is also the political question “how should and could Islamic modernity be”. The answers to these questions depend on many factors but, probably, they should come, in first instance, from Muslim communities and, in second, as from Social Sciences. Thus, what can be done?

3. The Boundaries of the Critique of Ideologies

As it was pointed out above, secularism even influenced approaches and methods of social sciences. A popular trend that emerged from Marxist studies and that has been amply used to understand religion is the so-called critique of ideologies or unmasking rhetoric. The assumption informing this approach is that behind any religion or political view, there are hidden motives, particular agendas disguised by them. In addition, religion and ideology were considered legitimizing mechanisms to justify social order, oppression and the status quo.

The critique of ideologies has been extremely effective to reveal diverse social phenomena linked to religion; however, it has also contributed to an atmosphere where the benefits brought by religion in the past were left aside (MacIntyre 1985). For instance, the connection between some religious institutions and power, the use of certain religious interpretations to maintain dominant relations amongst social groups were unveiled. Nonetheless, along this process to unmask hidden oppressive dynamics, the manifold vitalizing dimensions of religion were forgotten: its capacity to generate collective identity, social cohesion, a sense of mission, a transcendent perspective to afford difficulties, moral codes, altruistic action for future generations, sacred attitudes towards fundamental aspects of social and natural life that need to be preserved, a language to describe ethical, moral and spiritual issues, a complex form of rationality and others.

One of the relevant capabilities associated with religion that has been weakened has to do with the notion of “false idols”, as it was pointed out above. This concept is prevalent in many religious traditions although stronger in Judeo-Christian ones (Linford and Megill 2020, pp. 498–502). The collective capability to identify false idols protected communities from people who used religious symbols and narratives to promote hidden agendas (Dawes 1996, p. 90). It can be said that this function was replaced by the secular critique of ideologies; however, the critique of ideologies approach has not been effective enough to deal with secular narratives that resemble religious worldviews and that are being harnessed to justify the expansion of economic enterprises such as the Silicon Valley’s economic model based on technology, algorithms, artificial intelligence and the reduction of human will to make decisions (Borroughs [1970] 2009).

The situation becomes more serious when it is recognized both that religion has not disappeared from the public sphere and that many of the main issues affecting societies, as it was said before, are linked to religion.

Concerning the disappearance of religion, some indicators show the opposite. First and foremost, the global demographic data presented above are telling. In addition, the connection of religion and political conflicts, revolts and revolutions within the last four decades is quite clear: Iran’s Islamic revolution, Global Jihadism, some extreme right-wing movements, the upsurge of Christian fundamentalism and its influence on politics, whether in the United States, Bolivia and Brazil are just a few examples. Moreover, public debate on issues such as abortion, identity or surrogate motherhood are religiously and morally charged. Migration and the movement of populations are also definitively linked to religion in many different ways: some minorities abandon their countries as a result of persecution, big groups of migrants come from countries where religion has a great imprint in the popular culture so cannot be neglected by integration policies. On another note, research has shown that some religions contributed to modernize and to democratize certain countries (Conversi 2015) and helped to introduce modern medicine (Micklethwait and Wooldridge 2019; Van der Veer 2015). In addition, issues revolving around collective identity in Europe have brought explicitly religion as a source of values (Innerarity 2015). The role of religions in the development field, in the efforts to alleviate poverty and in the provision of social services has been recently underlined too. Finally, Western countries have experienced the birth of new religions, a renewed search for spirituality manifested in the growing trips to India or an important increase of practices such as yoga and meditation, and so, the religious diversity is much higher than decades before (Philpott et al. 2011).

In brief, it might be said that the persistence of religion in both modern (high industrialized) and traditional societies does not match the capacity to deal with it in most Western countries. This capacity has meaningfully declined over the last decades as a result of taking for granted the inexorable advance of secularization as well as of assuming the liberal framework as a value free framework. Therefore, in order to successfully address the myriad of social problems linked to religion and to design innovative approaches for policy, this capacity needs to grow. The next and last section of this paper contains a draft of a proposal on how to respond to this necessity.

The critique of ideologies can discover relations of power and interests between religions and other organizations and agendas. However, its lack of sensitivity towards religion prevents it from playing the important role of distinguishing valid religious claims from other narratives that try to legitimize, by using religious features, illegitimate motives. The case of the philosophy of progress revolving around the expansionist economic model of Silicon Valley—called into question by Eric Sadin in Siliconization of the world—is one of these examples (Sadin 2018).

4. Towards an Alternative Approach

The questions, then, are the following. If the capacity to tackle religiously inspired social phenomena is weak, how are we going to deal in Europe with migration and integration policies, of collective identities and intersubjective agreements, with the prevalence of Islam, with religious inspired terrorism, with issues related to contested notions of common good, justice, fairness and progress, with the connection between religion and politics, with the extreme individualism threatening social cohesion, if all of them are, to certain extend, connected to religion?

At the core of the approach proposed here to address these kinds of problems lies a premise. Religiously linked phenomena need to be explored from two different angles:

(a) Understanding the logic and sensitivity of religion. First, the optics and keynotes of religion need to be deployed in order to properly interpret the meaning of the dynamics of such a phenomenon. This goes beyond the anthropological or interpretative approaches in social sciences that advocate for revealing the meaning with which actors endow their actions. It is not just an emic, an immersion into the reality of those involved in the problem; neither a sociological analysis of religion. It requires understanding the language, sensitivity and logic of religion to make sure that the interpretation as well as the policies designed to respond to the phenomenon at issue brings positive outcomes and not unexpected consequences. For instance, although security issues are highly sensitive, measures cannot overlook their potential harm and feelings of grievance that might serve a justification for terrorist recruiters or radicalization agents (García-Magariño 2016a). What do the veil, the body, and inter-gender relation mean from the point of view of the religion held by the population which will be affected by a specific policy?

(b) Connecting religion to other social dimensions. The second feature of the premise underpinning the approach being described is that, after religious logics are assumed, scientific categories, such as identity, social class, nationality, ethnicity, gender, exclusion, reification, values changes or ideology are needed to capture the multiple dimensions of the issue at play (García-Magariño 2016b). Social phenomena cannot be detached from their social, political and economic nature, although religion is involved.

Jihadist terrorism could be taken as an example. Firstly, it has to be understood from a religious perspective. Terrorists claim to be following the commands of their interpretation of Islam. Hence, this interpretation, motives and religious organization cannot be excluded both from the analysis and the policy design to respond to it. However, it would be a mistake to stop there and to address the phenomenon just from the religious point of view: radicalization processes do not affect everyone; there are certain profiles more susceptible to be radicalized; there are certain economic, political and social conditions associated with the emergence of groups and individual terrorists; there are features in common with other sorts of crime; etc. (García-Magariño and Talavero Cabrera 2019).

In addition to what has been said, it has to be recognized that the sort of phenomena we are naming as “social problems linked to religion” are not just technical, scientific issues. Their nature is political, ethical, practical, so debate and dialogue about the problem, the different assumptions entailed, and the possible solutions and consequences of each solution are required. As Habermas states, practical problems require practical solutions and practical solutions demand ethical and political debate through communicative action, and not only scientific and technical inquiry (Habermas [1981] 2004). In some cases, the solution even requires making new intersubjective agreements, a kind of a new social contract.

Apart from the direct approach and particular measures to understand and address specific problems, it seems that certain cultural conditions need to be fostered in order to create deep social foundations to respond more effectively to general problems linked to religion.

Promoting religious literacy as well as scientific training appear paramount. Religious literacy prevents the expansion of prejudices, stereotypes and false images that hinder a good management of each issue. A sound scientific culture, on the other hand, permits a rigorous approach and acts as a protective bell to avoid conflicts grounded into misunderstandings. However, fostering a scientific and religious sound culture entails transcending positivist and reductionist conceptions of science as well as purifying religion from dogmas and superstitions.

Once the previous is achieved, new local structures for deliberation, dialogue and exchange of knowledge are needed to create the capacity, at the grassroots level, to address this kind of social issues progressively and effectively. In these structures, expert knowledge, traditional and religious insides and experiences coming from practices need to interact within consultative enclaves. Furthermore, the methods to facilitate these interactions, participation and deliberation need to be refined and improved over and over.

Finally, the most appropriate social space to articulate this learning process on how to deal with these phenomena effectively might be the local community. Hence, efforts to strengthen and empower this sort of dialogical, deliberative, learning local communities might be crucial, especially in the Western world, where the traditional geographically located communities were diluted and replaced by non-oppressive virtual communities and communities of adscription such as clubs and associations. Experience has shown, though, that these modern communities are not enough to enable collective-transformative action. Moreover, the coronavirus crisis has revealed that the stronger and more autonomous the local community, the better the response to face the sanitary, social and economic challenges associated with it. However, these communities need to harmonize three apparently opposing trends: the individual desire of freedom, the communitarian need to channel individual action towards the common good and the necessity for institutional direction. The notion of interdependence, cooperation and reciprocity might be the guiding principle to establish the sort of relations among these three actors conducive to the learning process described before.

5. Conclusions

In order to effectively address social issues linked to religion we need to revisit both the secularization theory, testing it against data, and the liberal framework within which current debates take place. In the case of the liberal framework, the values and premises on which it is grounded need to be made explicit and to be discussed.

An approach to address religious issues that emerged from secularization was the critique of ideologies. This approach has been very fruitful to unmask the connection between religion and power, and religion narratives and hidden particular agendas. However, along this process, vitalizing aspects of religion were abandoned from the analysis.

Given that religions and social phenomena linked to religion are still prevalent in the world but the capacity to deal with them has declined, innovative approaches are required in order to address them effectively. The approach proposed here departures from the perspective that social issues inspired or connected to religion need to be addressed, firstly, from the logics and perspectives of religion and, secondly, by using heuristic, scientific categories.

Finally, in order to achieve the above goal, certain cultural features need to be fostered. From among the manifold features, the need to advance towards an expanded rationality, to increase the collective capability to debate on assumptions and premises in search of intersubjective agreements and to forge sound religious and scientific capacities throughout social sectors stand out. Religious literacy together with new structures for learning in the context of local, geographical, deliberative local communities seem to be the appropriate social space and the best arena to generate knowledge on how to deal effectively with these pressing issues and to systematize the insights gained in the process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.-M.; methodology, S.G.-M.; validation, C.I.G. and O.P.-F.; investigation, S.G.-M., O.P.-F. and C.I.G.; resources, S.G.-M.; data curation, S.G.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.-M.; writing—review and editing, C.I.G. and O.P.-F.; supervision, S.G.-M.; project administration, S.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Project: “Smart War. Old wars and new technologies: a critical test for the regulation of political violence”. Code: PDC2021-121472-I00. Public University of Navarre. “Gender, identity and citizenship in far-right parties”. Principal researcher: Carmen Innerarity Grau. Code: PID 2020-115616RB.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Development studies emerged as a new scientific discipline that combined different fields, such as economics, education, agriculture, engineering and social work. Its main focus was how to assist a population to overcome poverty and to generate prosperity. In addition, the interdisciplinary field included both practitioners and scholars as the area of research was linked to the generation of new practices and knowledge. |

| 2 | One of the authors (Sergio García-Magariño) has approached these same assumptions in other works, such as: “Un cuestionamiento de las bases conflictuales del debate contemporáneo” (García-Magariño 2016d); and “Secularisation, liberalism and the problematic role of religion in modern societies” (García-Magariño 2018). |

References

- Albrow, Martin. 2012. Global Age. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Globalisation. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bahá’í World Center. 2005. One Common Faith. Universal House of Justice. Available online: https://www.bahai.org/library/other-literature/official-statements-commentaries/one-common-faith/ (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Bellah, Robert. 1967. Civil Religion in America. Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 96: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 1967. The Sacred Canopy. Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Garden City: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 1974. Some second thoughts on substantive versus functional definitions of religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 13: 125–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter. 1999. The Desecularization of the World. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 2012. Further Thoughts on Religion and Modernity. Society 49: 313–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity. Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. 1995. Modernity, Pluralism and Crisis of Faith. The Orientation of Modern Man. Washington: Bertelsmann Foundation Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Borroughs, Williams. 2009. La Revolución Electrónica. Buenos Aires: Caja Negra Editora. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2004. Religiones Públicas en el Mundo Moderno. Madrid: PPC. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2009a. Immigration and the new religious pluralism. In Secularism, Religion and Multicultural Citizenship, 1st ed. Edited by Geoffrey Brahm Levey and Tariq Modood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 139–63. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2009b. Religion, politics and gender equality: Public religions revisited. In Report for the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Washington: Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs, p. 5. Available online: https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/publications/religion-politics-and-gender-equality-public-religions-revisited (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Casanova, José. 2019. Global Religious and Secular Dynamics: The Modern System of Classification. Washington: Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Conversi, Daniele. 2015. Globalisation, Ethnic Conflict and Nationalism. In Handbook of Globalization Studies, 1st ed. Edited by Bryan S. Turner and Robert J. Holton. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis, Chp. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 1994. Religion in Britain since 1945: Believing without Belonging. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, Gregory. 1996. The Danger of Idolatry: First Corinthians 8: 7–13. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 58: 82–98. [Google Scholar]

- Deneulin, Séverine, and Carole Rakodi. 2011. Revisiting Religion: Development Studies Thirty Years On. World Development 39: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Salazar, Rafael, Ferbabdi Velasco, and Salvador Ginés. 1996. Formas Modernas de Religión. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Duplessy, Lucien. 1959. El Espíritu de la Civilización. Barcelona: Taurus. First published 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Estruch, Joan. 2015. Entendre les Religions: Una Perspectiva Sociològica. Barcelona: Mediterránea. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1989. The end of history? The National Interest 16: 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, Marina. 2017. Nueva Ilustración Radical. Barcelona: Anagrama. [Google Scholar]

- García-Magariño, Sergio, and Víctor Talavero Cabrera. 2019. A Sociological Approach to the Extremist Radicalization in Islam: The Need for Indicators. The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs 21: 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Magariño, Sergio. 2016a. Desafíos del Sistema de Seguridad Colectiva de la ONU: Análisis Sociológico de las Amenazas Globales; Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

- García-Magariño, Sergio. 2016b. El riesgo de no entender las lógicas de la religión y el fundamentalismo. Revista Actualidad Criminológica, UCJC 3: 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- García-Magariño, Sergio. 2016c. Gobernanza y Religión. Madrid: Delta. [Google Scholar]

- García-Magariño, Sergio. 2016d. Un cuestionamiento de las bases conflictuales del debate contemporáneo. Journal of the Sociology and Theory of Religion 5: 171–90. [Google Scholar]

- García-Magariño, Sergio. 2018. Secularization, liberalism and the problematic role of religion in modern societie. Cuadernos Europeos de Deusto 59: 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershman, Carl. 2000. Explaining Communism’s Appeal. Journal of Democracy 11: 169–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Emily. 1992. MacIntyre, Rationality and the Liberal Tradition. Polity 4: 433–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Hector, William Vega, David Williams, Wassim Tarraf, Brady West, and Harold Neighbors. 2010. Depression care in the United States: Too little for too few. Archives of General Psychiatry 67: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grames, Carlos. 2011. El puño Invisible. Barcelona: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, John. 2000. Two Faces of Liberalism. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2004. The Theory of Communicative Action. Reason and the Raitonalization of Society. Cambridge: Polity Press. First published 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2009. Ay Europa. Madrid: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2011. The political. The rationale meaning of a questionable inheritance of political theology. In The Power of Religion in Public Sphere, 1st ed. Edited by Eduardo Mendieta and Jonathan Van Antwerpen. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, David. 1998. La Condición de la Posmodernidad. Translated from the Original of 1989. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu. First published 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu-Lèger, Daniéle. 2004. Religion und sozialer Zusammenhalt. Transit: Europäische Review 26: 101–19. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, Samuel. 2002. El Choque de Civilizaciones. Schertz: Tecnos. [Google Scholar]

- Innerarity, Carmen. 2018. Illiberal Secularism. Fake Inclusion through Neutrality. Cuadernos Europeos de Deusto 59: 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innerarity, Carmen. 2022. La protección de lo sagrado en Francia: De las caricaturas a la ley para reforzar el respeto a los valores de la república. Revista de Estudios Políticos 195: 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innerarity, Daniel. 2015. Política en Tiempos de Indignación. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Joas, Hans. 2008. Do We Need Religion? On the Experience of Self-Transcendence. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Eric, Anne Goujon, and Vegard Skirbekk. 2012. The End of Secularization in Europe? A Socio-Demographic Perspective. Sociology of Religion 73: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linford, Daniel, and Jason Megill. 2020. Idolatry, indifference, and the scientific study of religion: Two new Humean arguments. Religious Studies 56: 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1985. Marxism and Christianity. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1988. Whose Justice? Which Rationality? Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, Richard. 2012. The Future of Transcendence: A Sociological Agenda. In The Axial Age and Its Consequences, 1st ed. Edited by Hans Joas and Robert Bellah. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, pp. 430–46. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Lanas, Javier. 2021. La posición original de Rawls: Crítica al desinterés mutuo de las partes. Anales de la Cátedra Francisco Suárez 55: 209–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micklethwait, John, and Adrian Wooldridge. 2019. God Is Back. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Modood, Tariq, and Thomas Sealy. 2022. Developing a framework for a global comparative analysis of the governance of religious diversity. Religion, State & Society 50: 362–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, Assaf. 2003. A Global Resurgence of Religion? 3rd ed. Cambridge: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2017. The Religious Typology: A New Way to Categorize Americans by Religion. Report on Religion and Public Life. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2018/08/29/the-religious-typology/ (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Pew Research Center. 2019. Global Attitudes Survey. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/07/20/global-religion-methodology/ (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Philpott, Daniel, Mónica Toft, and Timothy Samuel. 2011. God’s Century: Resurgent Religion and Global Politics. New York: WW Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Portier, Philippe. 2018. Le trournat substantialiste de la laïcité francaise. Horizontes Antropológicos 24: 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesebrot, Martin. 2014. Religion in the Modern World: Between Secularization and Resurgence. European University Institute, Max Weber Program. Fiesole: European University Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Roldán Gómez, Isabel. 2017. Lo postsecular: Un concepto normativo. Política y Sociedad 54: 851–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, Hartmut. 2019. Teoría de la resonancia como concepto fundamental de una sociología de la relación con el mundo. Revista Diferencias 7: 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sadin, Eric. 2018. La Siliconización del Mundo: La Irresistible Expansión del Liberalismo Digital. Buenos Aires: Caja Negra. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bayón, Antonio. 2016a. Religión Civil Estadounidense. Madrid: Sindéresis. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Bayón, Antonio. 2016b. Una historia filosófica de la identidad estadounidense. Bajo Palabra, II Época 18: 209–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo, Juan José. 2011. Otra Teología es Posible: Pluralismo Religioso, Interculturalidad y Feminismo. Barcelona: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Harvard: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Veer, Peter. 2015. Introduction to the Modern Spirit of Asia. Cultural Diversity in China 1: 115–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 2012. La ética Protestante y el Espíritu del Capitalismo. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. First published 1905. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. 2016. Community Driven Development: A Vision of Poverty Reduction through Empowerment. World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25787 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).