Abstract

This article seeks to shed light on the doctrinal meanings of the closed garden included in some Renaissance paintings of the Annunciation. To justify the iconographic interpretations that we will give of these paintings, we will base them on the analysis of many medieval liturgical hymns that poetically designate the Virgin Mary through the metaphorical expression hortus conclusus (closed garden) with which the Husband or Bridegroom requisites the Wife or Bride in the Song of Songs. We will divide our article into two parts as a strategy for analysis. First, we will analyze an extensive series of fragments of liturgical hymns that repeatedly praise Mary through this biblical metaphor. In the second part, we will examine some artistic representations of the Annunciation that, in the Italian Renaissance, depict a closed garden in the scene. From this double comparative analysis, textual and iconic, we will conclude that, in direct and essential correlation, those hymnic texts and those paintings clearly illustrate that the hortus conclusus is an eloquent symbol of the virginal divine motherhood of Mary and her perpetual virginity, as well as the excellence and fullness of her supernatural virtues and privileges.

1. Introduction

To justify various crucial Mariological dogmas, the Church frequently resorted to interpreting some Old Testament texts as explicit prophetic references to the Virgin Mary. This is especially evident in the dogmas of her virginal divine motherhood and her perpetual virginity, which several Old Testament passages foretell clearly, according to the millenary, consistent interpretive tradition of the Fathers and theologians of the Eastern and Western Churches. Among those precursors biblical texts, we are interested in highlighting in this article the quote from the Song of Songs, in which the Bridegroom or Husband (Sponsus) praises the Bride or Wife (Sponsa) in these lyrical terms: Hortus conclusus, soror mea sponsa, hortus conclusus, fons signatus. (Song 4, 12). “A garden shut up is my sister, my bride; A spring shut up, a fountain sealed.”1

We have explained in another article (Salvador-González 2023) the interpretations given to this passage of the Song of Songs by some Church Fathers and medieval theologians, such as Proclus of Constantinople,2 Hesychius of Jerusalem,3 John of Damascus,4 Ambrose of Milan,5 Jerome of Strido,6 Just of Urgell,7 Isidore of Sevilla,8 Ildephonse of Toledo,9 Paschase Radbert,10 Peter Damian,11 Hugh of Saint Victor,12 Honorius of Autun,13 Bernard of Clairvaux,14 Peter of Blois,15 and Bonaventure of Bagnoregio.16

Now, based on that millenary, coherent patristic, and theological tradition, numerous medieval writers composed countless antiphons, chants, and liturgical hymns in Latin using with poetic variations the metaphor hortus conclusus, and other expressions alluding to flowering and enclosure to extol Mary’s perpetual virginity and her virginal divine motherhood.

In this order of ideas, in the second section of this article, we will present an abundant series of fragments of medieval liturgical hymns that refer to the perpetual Virgin Mary through the hortus conclusus metaphor or other similar poetic expressions. We will give the pieces of hymns in chronological order, grouping them by centuries, to better perceive the eventual evolution of the conceptual variants given by hymnographers to these metaphorical proclamations.

Similarly, in the third section, we will analyze the iconography of ten paintings of the Annunciation depicted by some Italian Renaissance artists that in various ways illustrate the Mariological symbol hortus conclusus.

This double analysis of hymnic texts and visual images will allow us to infer to what extent we could justify the eventual direct relationship between those hymns and those images.

2. The Hortus Conclusus in the Medieval Liturgical Hymnography

We have found many hymns and liturgical chants that developed and poetically strengthened various tropes derived from the Biblical figure hortus conclusus and other analogous metaphorical expressions throughout the Middle Ages. Now, to better appreciate the eventual evolution in medieval hymnographers’ treatment of these metaphors, we will present these fragments of hymns in chronological order, grouping them by centuries.

Hymns from the 11th–12th century

From an approximate date between the 11th and 12th centuries, we have only found the Hymnus 98. Ad Beatam Mariam Virginem, which addresses Mary requesting her protection in the following terms:

Enclosed, irrigated garden, abundant in crops,Pure, sealed source that floods the riverSource that springs, inexhaustible, that exudes goodness,I ask you, merciful Virgin, grant me your protection.17

12th-century hymns

From the 12th century, we have documented these two hymns:

The Hymnus 326. De conceptione sanctae Mariae virginis pleads for the protection of the mother of God with these verses:

Oh, Mary, enclosed garden,port of the world that is shipwrecked,appease us [before] who made youhis chosen mother.18

The Hymnus 516. De sancta Maria praises the Virgin with these lyrical concepts:

Hail, blooming garden of the Sun,Star of the sea, safe harbor,The best draught always.19

13th-century hymns

From the 13th century, we have found these three hymns:

The Hymnus 260. De sancta Maria celebrates the perpetual virginity of the mother of God the Son with these short verses:

Garden blooming by the blow of the south wind,Closed door before and after [delivery],Road impassable for men.20

A few stanzas later, the Hymnus 260 pleads for the saving help of the Virgin with these warm statements:

Star of the sea, calm the sea,So that the storm does not envelop usnor the wild storm,but you lift us upto the heavenly palaceOur consolation,Oh, merciful Queen of heaven.21

The Hymnus 524. Prosa de beata Virgine celebrates the perpetual virginity of Mary in these rhetorical figures:

Closed door, fountain of the gardens,compartment that keeps ointments,perfume container.22

The Hymnus 136. De Beata Maria Virgine extols the perpetual virginity of the mother of God with these lyrical metaphors:

1a. Hail mother of the Lorddouble-scented flower,single mother virgin

1b. Sealed fountain of grace,garden of modesty,You are designated as a closed door.23

Hymns of the 13th–15th centuries

From some imprecise date between the 13th and 15th centuries, we have found these two hymns alluding to the subject under study:

The Hymnus 49 greets the virginal mother of God, helper of Humanity, in the following way:

Oh savingport of the poorflourishingAnd closed garden,The sun was born from youYou give birth to God as a virgin.24

The Hymnus 186 expresses several concepts relatively similar to those of the preceding Hymn 49, singing the universal protection of the mother of the Savior with this outstanding stanza:

Mary, flower of wonderfulBeauty,And tower of the fortressOf the prisoners,Garden of delights,Harbor for the shipwrecked,Through you the supreme Son was born.25

14th-century hymns

From the 14th century, we have documented these fourteen hymns:

The Hymnus 593. Ad eandem [beatam Virginem Mariam] greets the mother of the Redeemer with these eloquent analogies:

Hail, gloriouswell of living waters,graceful light,fountain of delights,Virgin artery of forgiveness,seal of virginity,Hope of our conscience,Mother of the Saviour.26

The Hymnus 472. Ad nonam qualifies the Virgin Mary with these poetic figures:

Closed and pleasant garden,Always full of all the flowers,To whom singularly the south windGently breathed.27

The Hymnus 541. De sancta Maria greets the perpetually virgin Queen of Heaven through these warm compliments:

Illustrious advocate,Garden of the Trinity,Empress of Heaven,temple of deity,shining sky starWith great clarity,Please be for me, Madam.28

The Hymnus 548. Ad vesperas. Hymnus exalts the virginal mother of God, whose protection it pleads in every trial, with these moving verses:

Wife, sister, dowry, and daughterof the supreme Creator,who begets the Father, born of her offspring,the first among the virgins,blooming garden, source of sweetness,great hope of the world,hear the cry of your children,fountain of mercyconsoling the orphans,grant us the gifts of graceand add us to the chorusof the heavenly host.29

The Hymnus 507. Oratio, quae dicitur crinale beatae Mariae virginis praises the ever-virgin Mary, begging for her saving help, with this vibrant stanza:

Oh, Mary, closed door,Enclosed garden, comfort usYou, who are the first of the virgins,born of a line of kings,Take us to Paradise.30

In the long Hymnus 5. Hortulus Beatae Virginis Mariae, entirely devoted to the metaphor hortus conclusus, its author Konrads von Haimburg (Conradus Gemnicensis) celebrates Mary’s perpetual virginity and her divine virginal motherhood with these ingenious stanzas:

1. Oh, Mary, Paradise,Garden of joy,Full of all the goods,An undivided source,And a quadruple river irrigates youWith the gifts of grace.[…]4. You are the closed gardenthat the Supreme architect of the universe,planted with flowers.This favorite [Son] of yours,Who has his head covered in dew,Is not excluded in any way.31

In a new stanza, the hymnographer Konrads von Haimburg assumes the role of Christ to address the Virgin with these poetic expressions:

7. Entering you, who were dedicatedFor me as a virgin, daughter.My sister, wife,I will pick the lilieshidden in your gardenDelicate with the breath of the south wind.32

Finally, in a new stanza, Konrads von Haimburg insists on similar tropes, stating:

8. The garden of your chestBlown by the south wind of the [Holy] SpiritWill sprout with flowers.God, hidden and veiledWith the veil of your body,Will germinate in you.33

The Hymnus 53. De conceptione Beatae Mariae Virginis sings to the ever-virgin Mary, mother of the Saviour, with these verses:

Sealed fountain, enclosed garden,An indication of this is the fact thatthe present birth of Maryis the destruction of death,which [Mary], being the port of salvation,starts life.34

The Hymnus 12. De conceptione Beatae Mariae Virginis, in Pars 3. Nocturne. Ad Laudes. Antiphonae, addresses the mother of God as follows:

This is that sealed fountain,The closed garden, breathedFrom Heaven by the breath of the south wind,With whose covering shadow she conceived.35

The Hymnus 59. In Annunciatione Beatae Mariae Virginis glorifies the virginal mother of the divine Redeemer with these epithets:

4a. Rejoice, earth, that through the dewYou conceived the SaviorAt the same time with joy.4b. Fountain of the gardens, enclosed garden,Distilling honey, port of life,Open Heaven’s gate.36

The Hymnus 83. De beata Maria Virgine greets the Queen of Heaven with this stanza:

You are the sunStar of the sea,Enclosed garden,Harbor of life,Virgin Mary.37

The Hymnus 58. In Assumptione Beatae Mariae Virginis glorifies the mother of God with these lyrical effusions:

The name of the mother is a star of lightOr an alabaster jar for scentsVery soft for the sense,The body of God, the castle of the WordThe closed garden, the rake of the FatherThat produces optimal fruit.38

The Hymnus 90. Jubilus de singulis membris Beatae Mariae Virginis extols the power of help and protection of the ever-virgin Mary, by expressing:

You are the star of the seahealthy medicineOf bodies and hearts,You are the sealed source, the closed garden,The path of peace, the port of life,The refuge of the poor.39

Probably from the 14th century is also the Hymnus 531. Alia sequentia, which offers these brilliant lines about the virginal mother of God:

Blooming garden, pleasant to the sick,sealed source of purity,That gives the currents of grace.Throne of the true Solomon,To whom the King of gloryAdorned with the illustrious gifts of heaven.40

15th-century hymns

We have documented these ten hymns from the 15th century on the subject under analysis.

The Hymnus 600. Laudes Mariae repeatedly praises the virtues and supernatural attributes of the ever-virgin Mary with these splendid rhetorical figures:

Queen of mercy,Called Mary,designated in antiquityWith various modes:You are rod, you stem,you sealed virgin,You bed, you bedchamber,You gifted spouse.41

Then this Hymn 600 goes on to express with even greater brilliance this splendid string of poetic tropes:

You [are] temple, you chamber,you closed doorYou ship, you anchoryou called starYou sun, moon, balm,armed army,you shining dawn,You proven gem.

You fountain, garden, plantain,raised cedar.You palm, you olive tree,planted cypress,most chosen myrrh,burning bush;You glass windowirradiated by the sun.42

The Hymnus. 515. De sancta Maria sings the perpetual virginity and the divine virginal motherhood of Mary with these brief but dense verses:

You are the door that became accessible only to the Lord,the garden in which the divinity was hidden,the star, which brought the Sun into the world.43

The Hymnus 21. Historia de Domina in sabbato. Ad Laudes. Antiphonae eulogizes the sublime perpetual virginity of the mother of God with these illustrative rhymes:

You are the garden of aromas,What delights the beloved,The sweet source of charismasThat sweetens affection.You are the enclosed gardenBlossomed by the breath of the south wind,The placid sealed fountain,The port in storms.44

The Hymnus 24. Centinomium Beatae Virginis. Secunda Pars. Capitulum quartum sings the perpetual virginity of Mary with these concepts:

As [Solomon in Song of Songs] himself said,You are the enclosed gardenthat germinates variousherb species,with which a beautiful matteris done,by which the flood of the mindIs repelled.45

The Hymnus 38. Abecedarius XIII praises the ever-virgin Mary with these eloquent words:

You are the flowery gardenthat produces delights,and shines with the variousflowers of virtues.46

Several stanzas later, it follows:

You are designated as the gardenventilated by grace,that provides the wonderful fruit of heaven,please give us the remedyto the wretched,and to the defeatedin the darkness of purgatory.47

The Hymnus 50. Rosarium exalts the virginal mother of God with this stanza:

Oh Mary, closed gardenAnd little casket (?) from the garden,From which a flower [Christ] grew for us,whom you cared for diligently,And who, when he was tormented on the cross,Absolved all wrongdoing.48

The Hymnus 14. In Nativitate Domini Nostri sings of the virginal mother of God by these poetic words:

Seed of Zion, root of David,Enclosed garden, which he enteredThe heavenly splendor of the Father.49

The Hymnus 100. Ad Beatam Mariam Virginem praises the ever-virgin Mary with these idyllic analogies:

Pure sealed source,Enclosed and fenced garden,Full of sacred fruitAnd fertilized with perfumes.50

Finally, the Hymnus 113. De Beata Maria Virgine sings to the always virginal mother of God and helper of humanity with these lyrical metaphorical figures:

Hail, venerablemother of mercy,admirable Maryform of holiness,incomparable flower,virginity garden,ineffable splendor,Temple of the deity.51

As a summary

From what we have been able to see in this second section, all the medieval liturgical hymns we have brought here focus on designating the Virgin Mary through the well-known metaphors “closed garden” and “sealed fountain” (hortus conclusus, fons signatus), with which the Bridegroom praises the Bride in Song of Songs. Now, although the various hymns given assume these two biblical metaphors with different approaches and expressive modes, all unanimously agree in interpreting both metaphorical expressions as clear references to Mary in two of her exclusive privileges: her virginal divine motherhood and her perpetual virginity (virgo ante partum, virgo in partu, virgo post partum: virgin before childbirth, virgin in childbirth, virgin after childbirth).

On the other hand, from the comparative analysis of the verses and stanzas presented here, one can deduce that many of these hymns relate the concepts hortus conclusus and fons signatus to the eastern porta clausa (closed door) of Jerusalem temple foretold by the prophet Ezekiel (Ez 44:1–4) during the exile of the Jews in Babylon. Such relationship is wholly coherent since, as we have shown in other works (Salvador-González 2020b, 2021d, 2021e), this Ezekiel’s porta clausa is also an eloquent metaphor of the perpetual virginity and virginal divine motherhood of Mary in the Christian exegetical tradition.

In addition, many hymns analyzed here highlight Mary’s privilege as virginal mother of God when they state that she is the fertile “closed garden” that, irrigated by heavenly dew and receiving the breath of the south wind (that is, when fertilized by the Holy Spirit), produces an admirable heavenly fruit (sometimes, it also says a flower), which is Christ, the Savior. For this reason, some hymns say that Mary is the “closed garden” in which the deity was hidden, or they designate her as the “garden of the Trinity” and the “temple of the deity”.

In a similar way, many fragments of the hymns exposed here associate the closed garden with the exclusive virtues of Mary: The Virgin is the flowery or flourishing hortus conclusus that, like an exuberant garden of delights, produces, preserves, and is filled with the flowers and perfumes of the Virgin’s virtues, especially her purity, her charity, her goodness, her sweetness, and her mercy.

As if that were not enough, several of these liturgical hymns take advantage of the homophony between the words hortus (garden, orchard) and portus (port, harbor), to highlight the mercy, the help, the protection, and the consolation that Mary grants to human beings (navigators and shipwrecked), thanks to her sublime privilege of being the Mediatrix, Helper and Co-redemptrix of Humankind.

3. An Iconographic Analysis of Some Renaissance Paintings of the Annunciation with a “Closed Garden”

We will now analyze chronologically ten representations of the Annunciation painted by some Italian artists of the 14th and 15th centuries that include an enclosed “garden” in their scene. It is convenient to specify that the iconographic motif of the hortus conclusus is not limited to the images of the Annunciation but also extends to other Marian representations, among them, the iconographic type of The Virgin of Humility. On the other hand, we have chosen ten significant representations of The Annunciation of the Italian Renaissance to better focus the research on a relatively homogeneous country and era. However, we do not mean by this that these ten paintings we have chosen are the only ones–and not necessarily the most important ones–on the subject; considering that, together with those from Italy, we could have studied other Annunciations painted by artists from Flanders, France, Spain or Germany. Even without leaving Italy, we could have analyzed other equally relevant Annunciations, such as the one already mentioned by Fra Angelico in the altarpiece of San Giovanni Valdarno, c. 1430–1432, that of Benedetto Bonfigli (c. 1445) from the Thyssen Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, or two others by Fra Filippo Lippi, The Annunciation with Two Donors, 1450, from the Galleria d’Arte Antica in Rome, and The Annunciation with Two Angels, 1450, from the Church of San Lorenzo in Florence.

Fra Angelico (c. 1396–1455) painted six different versions of the Annunciation: the first three on altarpieces (today preserved in museums in Madrid, San Giovanni Valdarno, and Cortona), two more as fresco murals in the Convento di San Marco in Florence–we will soon analyze the most important of them–and one more on a small table that is one of the many scenes that make up the Armadio degli Argenti, which we will also analyze later.

From the outset, it is interesting to note that, in almost all these representations of the Annunciation, Fra Angelico brought to light, with greater or lesser emphasis, the theme of the hortus conclusus. The only exception is the small fresco mural in the Convento di San Marco because the painter staged the episode in a bare, cramped convent cell. In turn, in his Annunciation of the altarpiece in the Prado Museum in Madrid, the artist, despite having included in the composition a flowery garden through which Adam and Eve wander, leaves in suspense the enclosure of the hortus conclusus; however, this could be subtly suggested by the thick forest that closes the garden at the bottom of the scene.

The Annunciation from the Museo Diocesano di Cortona, c. 1433 (Figure 1) is the third representation of this Marian episode that Fra Angelico shaped as an altarpiece, after the first, preserved in the Prado Museum, c. 1426, and the second, housed in the Museum of Santa Maria delle Grazie Basilica in San Giovanni Valdarno, c. 1430–1432. In this third version of Cortona, the painter makes a narrative and compositional approach quite like the two previous versions of Madrid and Valdarno, with more remarkable similarities to the latter. In fact, after changing the vanishing point in a linear perspective, the Cortona’s Annunciation resembles Valdarno’s in these four elements: the representation of the house like a loggia open towards the flowery garden and covered by a flat roof; a similar bust of the prophet Isaiah in the tondo over the central column; the resplendent dove of the Holy Spirit flying over the head of the Virgin, without the usual ray of light descending from above; an analogous scene of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden in the upper left corner of the composition, to illustrate the antitheses between Eve and Mary, and between Adam and Christ, who is being conceived in Mary’s womb at the final moment of the Annunciation.

Figure 1.

Fra Angelico, The Annunciation, c. 1433. Museo Diocesano di Cortona.

However, the most relevant detail for our interests is the wooden fence that, although small (almost imperceptible), closes the garden in the median plane, to signify the Mariological metaphor hortus conclusus. The cultured Dominican friar Fra Angelico put up this fence enclosing the garden to signify the dogmas of the divine virginal motherhood of Mary and her perpetual virginity, so unanimously proclaimed by some theologians and composers of medieval liturgical hymns, many of whose stanzas we exposed in the second section.

To better manifest the mystery of the supernatural human conception/incarnation of God the Son in the virginal womb of Mary, Fra Angelico has made the dialogue between the two protagonists visible through several inscriptions in gold letters that flow from their mouths. Gabriel’s speech appears in two separate lines: the upper line, curving upwards, expresses Sp[iritu]s S[anctus] sup[er]ve[n]iet i[n] te; the lower line, descending rectilinearly, enuncia virt[us] Alti[s]si[mi] obu[m]brabit tibi. Mary’s response, Ecce ancilla Do[mi]n[i fiat mihi secundum] v[er] bu[m] tuum, appears in the middle line with its letters inverted from bottom to top: with this rather naive reversal of the statement of Mary, Fra Angelico intends to make the ignorant faithful understand that God can read it from the heavenly heights.

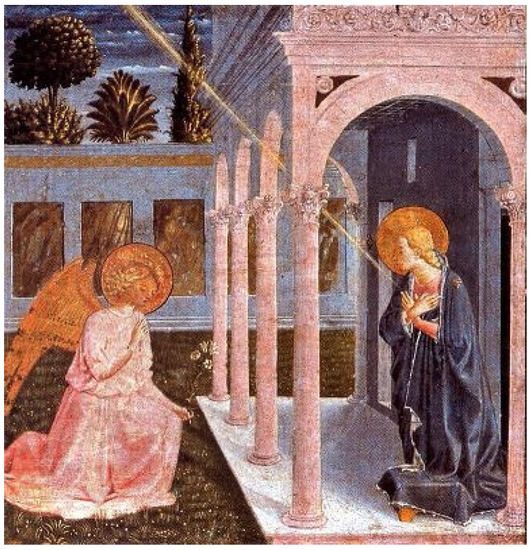

In the large fresco of The Annunciation, c. 1440–1450, painted in the first-floor corridor of the Convent of San Marco in Florence (Figure 2), Fra Angelico re-enacts the Marian episode in a house shaped like a vaulted loggia. Inside this classical setting, Gabriel and Mary dialogue with reverent attitudes: the angel respectfully announces the heavenly message to the Virgin; she humbly accepts the divine design like the submissive “slave of the Lord.” Surprisingly Fra Angelico does not incorporate any symbolic feature of the godhead in this fresco, not including either the (more or less aniconic) figure of God the Father, the beam of light (God the Son), or the dove of the Holy Spirit.

Figure 2.

Fra Angelico, The Annunciation, c. 1440–1450. Convento di San Marco, Florence.

However, in front of his other Annunciations, Fra Angelico depicts in this fresco with a strong emphasis the wooden fence that encloses the flowery garden of the Marian abode. In that way, this erudite Dominican friar wants to highlight the profound Mariological meanings of the hortus conclusus, according to the firmly established theological tradition.

Therefore, it is outstanding that the commentators we know of this work (Pope-Hennessy 1952; Argan 1955; Berti 1966; Baldini 1970; Bonsanti 1984; Guillaud and Guillaud 1986; Hood 1993; Bartz 1998, 50; Zuccari et al. 2009) leave unexplained with patristic and theological arguments the Mariological meanings of this hortus conclusus, proclaimed by countless medieval liturgical hymns.

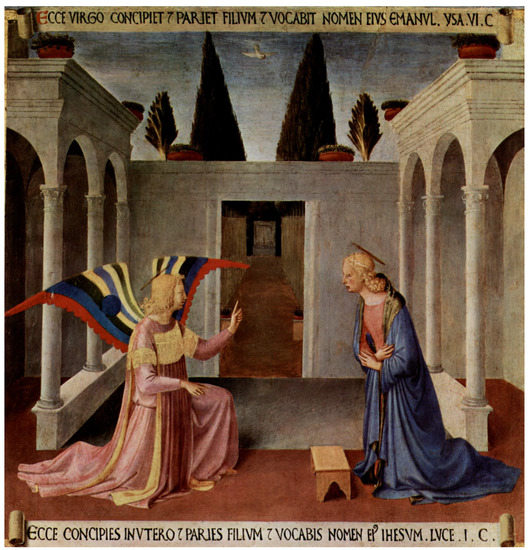

In The Annunciation, c. 1451–1453, which is one of the scenes that decorate the Armadio degli Argenti in the Museo del Convento di San Marco in Florence (Figure 3), Fra Angelico sets the composition according to a rigid monoaxial symmetry, in which characters, architectural elements and components of the natural landscape are perfectly balanced.

Figure 3.

Fra Angelico, The Annunciation, c. 1451–1453. A scene from the Armadio degli Argenti, Museo Convento di San Marco, Florence.

In this geometric setting, the angel Gabriel, with his right knee on the ground and his left index finger pointing heavenward to indicate the celestial origin of his message, communicates the divine plan to the humbly kneeling Mary. This is specified in the message Ecce concipies et paries filium, et vocabis nomen eius Iesus (Lk 1:31) (“Behold, you will conceive and give birth to a son whom you will name Jesus”), inscribed in a band at the bottom of the painting. To highlight the prophetic background of this announcement by Gabriel, the artist places the prophecy of Isaias on the upper edge of the painting: Ecce virgo concipiet et pariet filium, et vocabit nomen eius Emmanuel (Is 7:14) (“Behold, a virgin will conceive and give birth to a son and will call him Emmanuel.”)

It is interesting to note that, right on the axis of the compositional symmetry, the painter reveals, through the doorless entrance, a garden whose enclosing wall appears in the background. Once again, the erudite Dominican painter Fra Angelico highlights this hortus conclusus to illustrate that in the event of the Annunciation, two fundamental Mariological dogmas are condensed: Mary’s virginal divine motherhood and her perpetual virginity.

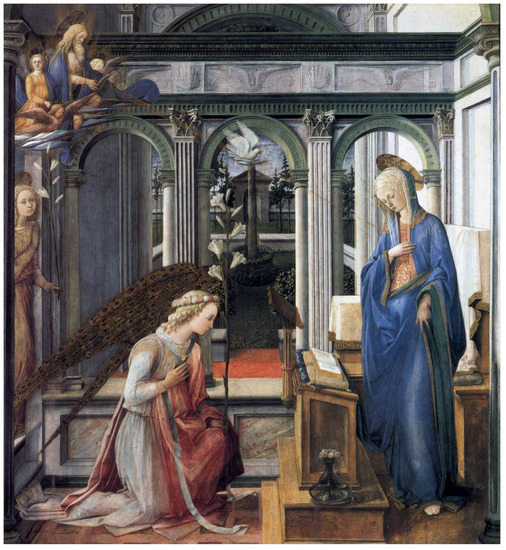

Fra Filippo Lippi (1406–1469) painted this Annunciazione delle Murate, 1443, from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich (Figure 4) for the convent of the suore murate (enclosed nuns) in Florence. The artist has represented here Mary’s humble house in Nazareth as a splendid palace to symbolize the particular Mariological and Christological meanings we have highlighted in other articles (Salvador-González 2021a, 2021b). Escorted by angels in the upper left corner, God the Father sends towards the Virgin the fertilizing ray of light (symbol of God the Son), in whose wake the Holy Spirit’s dove flies. In the middle of the room, the archangel, holding a lily stalk in his left hand, kneels reverently before Mary, while a second angel stands with another lily stalk on the door lintel on the left side. The standing Mary listens to the celestial announcement, humbly showing her submission like the “slave of the Lord” by lowering her head and putting her right hand on her breast.

Figure 4.

Fra Filippo Lippi, L’Annunciazione delle Murate, 1443. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

It is relevant to note that Lippi wants to highlight in this painting the double enclosure of the garden (hortus conclusus), perceivable through the three arches: the first enclosure is a low white wall in the mid-ground; the second one, more strong and high, is the heavy wall stretching out on both sides in the background, with a wide door under a triangular pediment.

Megan Holmes (1999, pp. 239–40) has rightly suggested that both walls of the garden may allude to the suore murate (enclosed nuns) for whom the painting was intended. Nonetheless, it seems clear that the cultured Carmelite painter who was Fra Filippo Lippi decided to make visible with both closing walls of this garden the Mariological symbolisms we have explained following the long-lasting doctrinal tradition embodied in the numerous medieval liturgical hymns we have exposed.

Therefore, it is pretty disappointing that most commentators on this outstanding painting by Lippi (Marchini 1979; Ruda 1993; Christiansen 2005; Fossi and Pinci 2011) have forgotten to mention the hortus conclusus, or, if mentioned, to justify documentarily its deep dogmatic meanings. Instead, in her well-documented monograph on Fra Filippo Lippi, Megan Holmes (1999, pp. 239–40) is, as far as we know, the only one who, when commenting on this painting, alludes to the Marian symbolism of the hortus conclusus, although without justifying it through primary sources.

Domenico Veneziano (1410–1461) framed this Annunciation, c. 1445, from the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK (Figure 5), with a relatively symmetrical composition (with a marked offset to the left), which is quite reminiscent of the compositional approach given by Fra Angelico in the just analyzed panel of the Armadio degli Argenti. Although housed today in an English museum in Cambridge, this small painting by Domenico Veneziano is a scene from the predella of the famous Pala di Santa Lucia de’ Magnoli (also called Sacra conversazione coi santi Francesco, Giovanni Battista, Zanobi e Lucia), c. 1445, preserved today in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence. In this small panel at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Domenico Veneziano—as did Fra Angelico in the panel just analyzed—stages the episode in a sizeable porticoed patio. Kneeling on the ground with a lily stem in his left hand, the archangel points his right index finger up to indicate the heavenly origin of the message he is addressing to Mary. Standing on the right side of the painting, she shows her obedience to God’s will, bowing her head and crossing her hands on her chest.

Figure 5.

Domenico Veneziano, The Annunciation (predella of the Pala di Santa Lucia de’ Magnoli), c. 1445. The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK.

Even if avoiding the physical or symbolic representation of the godhead—God the Father, God the Son (the ray of light), and the Holy Spirit (the dove) are absent in this panel—Veneziano highlighted the dogmatic meanings of the biblical metaphor hortus conclusus. That is why he places in prominent centrality, at the back of the scene, a wooden door, with a heavy security bar—an explicit reference to Ezekiel’s porta clausa, whose Mariological and Christological meanings we have explained in other articles (Salvador-González 2021e, 2021d, 2020b)—that closes the flowery garden in the central corridor.

Furthermore, Benozzo Gozzoli (1420–1497), in The Annunciation that is part of the predella of the famous altarpiece La Madonna della Cintola, c. 1445, from the Vatican Pinacoteca (Figure 6), reflects the same dogmatic meanings of the virginal divine motherhood of Mary and her perpetual virginity symbolized by the metaphor hortus conclusus. For this reason, in the foreseeable context of the dialogue between the two protagonists of the episode, the painter places the Virgin in the portico of a symbolic palace, while the angel Gabriel is in the nearby garden. It is important to emphasize here that this garden is enclosed (not to say walled) by a high marble wall, which shows the enclosure and impassability of this symbolic Marian garden.

Figure 6.

Benozzo Gozzoli, The Annunciation, c. 1445. A scene of the predella of the Madonna della Cintola altarpiece. Pinacoteca Vaticana.

Fra Filippo Lippi poses The Annunciation (L’Annunciazione Doria), c. 1445–1450, from the Galleria Doria-Pamphilj in Rome (Figure 7), with some compositional novelties: for example, the inversion of the position of the two protagonists, with Gabriel on the right side and Mary on the left, the double stem of lilies, one carried by the angel, the second in a vase on the floor. While Gabriel, beginning to kneel before the Virgin, greets her reverently, she turns her head toward the angel, raising her open right hand in a gesture of unconditional obedience to the will of the Most High. Behind Mary’s back, her impollute marriage bed stands out, a bed whose Mariological and Christological meanings we have shed light on in other articles (Salvador-González 2021c, 2020a, 2019).

Figure 7.

Fra Filippo Lippi, The Annunciation (L’Annunciazione Doria), c. 1445–50, Galleria Doria-Pamphilj, Rome.

However, the most interesting for our purposes is the exuberant enclosed garden seen through the opening in the center of the painting. Once again, the cultured Carmelite friar that was Fra Filippo Lippi visualized through the symbol of this enclosed garden the dogmatic meanings of the divine virginal motherhood of Mary and her perpetual virginity, and even her sublime virtues and supernatural privileges, on which many of the liturgical hymns analyzed here insist.

Zanobi Strozzi (c. 1412–1468) stages The Annunciation, c. 1453, from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Figure 8) on the outside of a building, whose “courtyard” is enclosed by a high wall. Still descending from heaven with his colorful wings outstretched and almost about to touch the ground with his feet surrounded by clouds, Gabriel blesses the Virgin while carrying a lily stem in his left hand. Seated under a baldachin-balcony, Mary expresses her obedience to God’s design by the gesture of crossing her hands on her chest. The painter depicts the presence of the godhead through the fertilizing beam of light (symbol of God the Son) and the dove of the Holy Spirit.

Figure 8.

Zanobi Strozzi, The Annunciation, c. 1453, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA.

It suits our purposes to highlight in this painting the high wall that closes off the vast courtyard (an analogy of “garden”). It sounds evident that, through this high wall, Strozzi seeks to communicate the idea of the hortus conclusus, as a symbol of Mary’s virginal divine motherhood, her perpetual virginity, and the fullness of her sublime virtues and privileges, as the medieval liturgical hymns celebrate.

Alessio Baldovinetti (1427–1499) stages The Annunciation, c. 1457, from the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence (Figure 9) in the vaulted portico of a Renaissance palace, to whose dogmatic meanings we have already drawn attention. With his arms crossed on his chest, the angel Gabriel begins to kneel before the Virgin, who stands up after rising from her seat due to the unexpected arrival of the heavenly messenger. She expresses her unconditional acceptance of the divine will with the gesture of raising her right hand and humbly lowering her head and eyes. Apart from the foreseeable compositional and narrative details in this Marian scene, it is interesting to highlight the high marble wall that closes the garden surrounding the palace. It seems evident that the intellectual author of this painting wants to convey the Mariological symbolism of this hortus conclusus, with the multiple doctrinal projections that medieval liturgical hymns gave to this eloquent metaphor.

Figure 9.

Alessio Baldovinetti, The Annunciation, c. 1457. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510) shapes the Cestello Annunciation, 1489–1490, from the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence (Figure 10), with some impressive narrative novelties, primarily through the highly expressive gestures and attitudes of both protagonists. Even if it would be beneficial to interpret this bodily expressiveness, however, we are more interested in emphasizing the simple garden enclosed by a low white wall that one can see through the door before an extensive landscape of a river and a town. Undoubtedly, Botticelli brings in this Cestello Annunciation a fine example of hortus conclusus to underline its Mariological meanings, following the poetic tropes expressed by many medieval liturgical hymns.

Figure 10.

Sandro Botticelli, The Cestello Annunciation, 1489–1490. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

That is why it is surprising to note that, as far as we know, none of those who have commented on this outstanding painting (Schneider 1911; Argan 1957; Mandel 1967; Horne 1986, 1980; Meltzoff 1987; Lightbown 1989; Grömling and Lingesleben 2000; Magaluzzi 2003; Cecchi 2005) has highlighted this hortus conclusus and, even less, has justified its true Mariological meanings from primary sources of Christian doctrine. A partial exception to this embarrassing silence is Ronald Lightbown (1978), who, when analyzing this Cestello Annunciation in his monograph on Botticelli, does mention the enclosed garden without any further doctrinal explanation.

4. Conclusions

We could synthesize the main results of this double analytical survey over texts and images through these four brief conclusions:

- Numerous medieval liturgical hymns repeatedly insist on extolling the Virgin Mary, designating her through the biblical metaphor hortus conclusus (enclosed garden) and fons signatus (sealed source)—its correlative twin expression in Song of Songs—or even with other relatively similar rhetorical figures, such as porta clausa (Ezekiel’s closed door) or florens hortus (flowering garden), emphasizing both its enclosure and its splendid fecundity.

- For more than a millennium, countless Fathers and theologians of the Eastern and Western Churches unanimously interpreted the biblical expression hortus conclusus as an eloquent symbol of the Virgin Mary in her double privilege as the virginal mother of God and perpetual virgin. Although we have not analyzed it, because it was not the objective of the current article, this ancient patristic and theological tradition constituted the legitimizing doctrinal source in which medieval hymnographers got inspiration and arguments when writing the liturgical hymns alluding to the analyzed biblical metaphor.

- Some paintings of the Annunciation from the Italian Renaissance show a garden—or an equivalent domestic space—enclosed by a fence or a wall. In this sense, it seems logical to conjecture that the different intellectual authors of these paintings, who coincide in including this enclosed garden in the representation of the decisive episode of the Annunciation, want to transmit through this metaphorical figure the conceptual content shared by all of them: the one expressed by the millenary doctrinal tradition on the Mariological meanings of the biblical trope hortus conclusus. We deliberately use the term “intellectual author of the painting”, because, except for the few privileged ones, such as Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi or Lorenzo Monaco, who, due to their position as clerics, had a vast theological culture, most artists lacked it. That is why it is logical to suppose that, when executing important commissions of Christian art, artists of a lesser cultural level would have at their side an ecclesiastic or scholar who would indicate to them the characters, situations, attitudes, dresses, attributes, objects, and symbols that they should include in the religious scene to be represented.

- Therefore, this double analysis of liturgical texts and pictorial images allows us to infer that both hymnographers and painters, based on the same millenary patristic and theological tradition, assume the metaphor of the hortus conclusus as an expressive Virgin Mary’s symbol in her double privilege of virginal mother of God and perpetual virgin, as well as in the excellence and fullness of her supernatural virtues and attributes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I want to express my warm and sincere gratitude to the Academic Editor of Religions for the useful and pertinent corrections that he/she suggested to me to improve the English writing of my article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Song of Songs 4,12. American Standard Version (ASV). https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Song+of+Songs+4%2C12&version=ASV (accessed on 21 September 2022). |

| 2 | Proclus Constantinopolitanus, Oratio VI. Laudatio sanctae Dei genitricis Mariae. PG 65, 758. |

| 3 | Hesychius Hierosolymitanus, Sermo V. Ejusdem de eadem [de sancta Maria Deipara Homilia]. PG 93, 1460–1461, y 146. |

| 4 | Iohannes Damascenus. Homilia II in Nativitatem B.V. Mariae. PG 96, 691. |

| 5 | Ambrosius Mediolanensis, De Institutione Virginis et S. Marie virginitate perpetua. Liber Unus. PL 16, 321, and 335–336. |

| 6 | Hieronymus Stridonensis, Epistola XLVIII, Seu Liber apologeticus, ad Pammachium, pro libris contra Jovinianum, 21. PL 22, 510. |

| 7 | Justus Urgellensis, In Cantica Canticorum Salomonis. Explicatio Mystica, 91. PL 67, 978. |

| 8 | Isidorus Hispalensis, De ortu et obitu Patrum, 111. PL 83, 148. |

| 9 | Ildefonsus Toletanus. Liber de virginitate perpetua S. Mariae adversus tres infideles. Caput X. PL 95, 93–99; De Partu Virginis, PL 96, 214–15. |

| 10 | Paschasius Radbertus, Expositio in Matttheum. Liber II, Caput 1. PL 120, 106. |

| 11 | Petrus Damianus, Sermo XLVI. PL 144, 760–61; Petrus Damianus, Carmina et preces. LXI. Rythmus de S. Maria virgine. PL 145, 938. |

| 12 | Hugo de S. Victore, De Bestiis et aliis rebus Libri Quatuor. Liber Quartus. De Proprietatibus et Epithetis rerum serie litterariae in ordinem redactis. Caput II. PL 177, 138–39. |

| 13 | Honorius Augustodunensis, Sigillum Beatae Mariae ubi exponuntur Cantica Canticorum. Caput IV. PL 172, 492. |

| 14 | Bernardus Claravaellensis, Sermones sobre El Cantar de los Cantares. Sermón 47, 3–5. In Obras completas de San Bernardo. Edición bilingüe promovida por la Conferencia Regional Española de Abades Cistercienses, vol. V. Sermones sobre El Cantar de los Cantares, Madrid, La Editorial Católica, Col. BAC, 1987, 619. |

| 15 | Petrus Blesensis. Sermo XXXVIII. In Nativitate Beatae Mariae. PL 207, 673. |

| 16 | Bonaventura de Balneoregio, De Assumptione B. Virginis Mariae. Sermo IV: Q IX, 695b–698b. |

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

|

| 42 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

|

| 45 |

|

| 46 |

|

| 47 |

|

| 48 |

|

| 49 |

|

| 50 |

|

| 51 |

|

References

Primary Sources

AHMA, 1. Dreves, Guido María. 1886. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, 1. Cantiones Bohemicae. Leiche, Lieder und Rufe des 13., 14. und 15. Jahrhunderts nach Handschriften aus Prag, Jistebnicz, Wittingau, Hohenfurt und Tegernsee. Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland).AHMA, 3. Dreves, Guido María. 1888. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, 3. Conradus Gemnicensis. Konrad von Hainburb und seiner Nachahmer und Ulrichs von Wessobrunn, Reimgebete und Leselieder. Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland).AHMA, 4. Dreves, Guido María. 1888. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, 4. Hymni inediti. Liturgische Hymnen des Mittelalters aus handschriftlichen Breviarien, Antiphonalien und Processionalien. Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland).AHMA, 5. Dreves, Guido María. 1892. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, 5. Historiae rhythmicae. Liturgische Reimofficien des Mittelalters. Erste Folge. Aus Handschriften und Wiegendrucken. Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland).AHMA, 6. Dreves, Guido María. 1889. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, 6. Udalricus Wessofontanus. Ulrich Stöcklins von Rottach Abts zu Wessobrunn 1438–1443 Reimgebe und Leselieder mit Ausschuss der Psalterien. Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland).AHMA, 9. Dreves, Guido María. 1890. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, 9. Sequentiae ineditae. Liturgische Prosen des Mittelalters aus Handschriften und Wiegenbrucken. Zweite Folge. Leipzig: O. R. Reisland.AHMA, 10. Dreves, Guido María. 1891. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, 10. Sequentiae ineditae. Liturgische Prosen des Mittelalters aus Handschriften und Wiegenbrucken. Dritte Folge. Leipzig: O. R. Reisland.AHMA, 15. Dreves, Guido María. 1893. Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, 15. Pia dictamina. Reimgebete und Leselieder des Mittelalters. Erste Folge. Aus Handschriften und Wiegendrucken, Leipzig: O.R. Reisland.Biblia Sacra. 2005. Biblia Sacra iuxta Vulgatam Clementinam. Nova editio (logicis partitionibus aliisque subsidiis ornata a Alberto Colunga et Laurentio Turrado). Madrid: La Editorial Católica.Bonaventura de Balneoregio. 1901. Doctoris seraphici S. Bonaventurae opera omnia. Tomus IX, Sermones de Tempore, de Sanctis, de B. Virgine Maria et de diversis. Quaracchi: Typographia Collegii S. Bonaventurae. Cited with the abbreviation Q IX.Bonaventura de Balneoregio. Sermones de B. Virgine Maria. De Assumptione B. Virginis Mariae. Sermo IV, 1: Q IX, 695b–698b.Hesychius Hierosolymitanus. Sermo V. Ejusdem de eadem [de sancta Maria Deipara Homilia]. PG 93, 1460–1465.Hieronymus Stridonensis. Epistola XLVIII, Seu Liber apologeticus, ad Pammachium, pro libris contra Jovinianum, 21. PL 22, 493–511.Honorius Augustodunensis. Sigillum Beatae Mariae ubi exponuntur Cantica Canticorum. Caput IV. PL 172, 495–518.Hugo de S. Victore. De Bestiis et al.iis rebus Libri Quatuor. Liber Quartus. De Proprietatibus et Epithetis rerum serie litterariae in ordinem redactis. Caput II. PL 177, 138–39.Hymnus 2. Crinale B. M. V. AHMA, 3, 25.Hymnus 5. Conradus Gemnicensis. Konrads von Haimburg. Hortulus B. V. M. AHMA, 3, 30.Hymnus 12. De conceptione BMV. In 1. Vesperis. Antiphonae. AHMA, 5, 47.Hymnus 12. De conceptione BMV. In 3. Nocturno. Ad Laudes. Antiphonae. AHMA, 5, 58.Hymnus 14. In Nativitate DN. AHMA, 10, 69.Hymnus 21. Historia de Domina in sabbato. Ad Laudes. Antiphonae. AHMA, 5, 74.Hymnus 24. Centinomium Beatae Virginis. Secunda Pars. Capitulum quartum. 118. AHMA, 6, 81.Hymnus 38. Abecedarius XIII. AHMA, 6, 132–33.Hymnus 49. AHMA, 1, 86.Hymnus 50. Rosarium III. AHMA, 6, 161.Hymnus 53. De conceptione BMV. AHMA, 4, 40.Hymnus 58. In Assumptione BMV. AHMA, 15, 86.Hymnus 59. In Annuntiatione BMV. AHMA, 9, 51.Hymnus 83. De beata Maria V. AHMA, 9, 69.Hymnus 90. Jubilus de singulis membris BMV. AHMA, 15, 110.Hymnus 98. Ad B. Mariam V. AHMA, 15, 125.Hymnus 100. Ad B. Mariam V. AHMA, 15, 132.Hymnus 113. De B. Maria V. AHMA, 15, 139.Hymnus 136. De Beata Maria V. AHMA, 10, 104.Hymnus 186. AHMA, 1, 170.Hymnus 260. De s. Maria. Mone, 1854, 53.Hymnus 326. De conceptione s. Mariae virg. Mone, 1854, 12.Hymnus 507. Oratio, quae dicitur crinale beatae Mariae virginis. Mone, 1854, 271.Hymnus 515. De s. Maria. Mone, 1854, 297.Hymnus 516. De s. Maria. Mone, 1854, 298.Hymnus 524. Prosa de beata Virgine. Mone, 1854, 310.Hymnus 525. Sequentia de b. v. Maria. Mone, 1854, 312.Hymnus 531. Alia sequentia. Mone, 1854, 187.Hymnus 541. De s. Maria. Mone, 1854, 333.Hymnus 548. ad vesperas. hymnus. Mone, 1854, 343.Hymnus 593. Ad eandem [b.v. Mariam]. Mone, 1854, 407.Hymnus 600. Laudes Mariae. Mone, 1854, 411.Ildefonsus Toletanus. Liber de virginitate perpetua S. Mariae adversus tres infideles. Caput X. PL 95, 93–99.Ildefonsus Toletanus. De Partu Virginis. PL 96, 214–215.Iohannes Damascenus. Homilia II in Nativitatem B.V. Mariae. PG 96, 691.Isidorus Hispalensis. De ortu et obitu Patrum, 111. PL 83, 148.Justus Urgellensis. In Cantica Canticorum Salomonis. Explicatio Mystica, 91. PL 67, 963–69.Migne, Jacques-Paul, ed. 1844–1864. Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Latina, Paris, Garnier, 221 vols. This collection of Latin Patrology is cited with the abbreviation PL.Migne, Jacques-Paul, ed. 1857–1867. Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Graeca. Paris: Garnier, 166 vols. This collection of Greek Patrology is cited with the abbreviation PG.Mone, Franz Josef. 1854. Hymni Latini Medii Aevi. E codd. Mss. Edidit et adnotationibus illustravit Franc. Jos. Mone. Tomus Secundus. Hymni ad. B.V. Mariam. Friburgi Brisgoviae: Sumptibus Herder.Paschasius Radbertus. Expositio in Matttheum. Liber II, Caput 1. PL 120, 106.Petrus Blesensis. Sermo XXXVIII. In Nativitate Beatae Mariae. PL 207, 672–677.Petrus Damianus, Sermo XLVI. PL 144, 760–761.Proclus Constantinopolitanus. Oratio VI. LaudatioSecondary Sources

- Argan, Giulio Carlo. 1955. Fra Angelico. Étude Biographique et Critique. Genève: Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Argan, Giulio Carlo. 1957. Botticelli. Étude Biographique et Critique. Genève: Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, Umberto. 1970. L’opera Completa dell’Angelico. Milano: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Bartz, Gabriele. 1998. Guido di Piero, Llamado Fra Angelico, Hacia 1395–1455. Colonia: Könemann. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, Luciano. 1966. Fra Angelico en San Marcos. Granada and Firenze: Sadea. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsanti, Giorgio. 1984. Florence, Fra Angelico au Musée de Saint-Marc. Paris: Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi, Alessandro. 2005. Botticelli. Milano: F. Motta. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, Keith, ed. 2005. From Filippo Lippi to Piero della Francesca. Fra Carnevale and the Making of a Renaissance Master. Milan: Edizioni Olivares. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fossi, Gloria, and Eliana Pinci. 2011. Filippo e Filippino Lippi. Firenze: Scala. [Google Scholar]

- Grömling, Alexandra, and Tilman Lingesleben. 2000. Alessandro Botticelli, 1444/1445–1510. Colonia: Könemann. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaud, Jacqueline, and Maurice Guillaud. 1986. Fra Angelico. Lumière de l’âme. Peintures sur bois et Fresques du Couvent San Marco de Florence. Paris: Guillaud Éditions. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Megan. 1999. Fra Filippo Lippi. The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, William. 1993. Fra Angelico at San Marco. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, Herbert P. 1980. Botticelli, Painter of Florence. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, Herbert P. 1986. Alessandro Filipepi Commonly Called Sandro Botticelli, Painter of Florence. London: George Bell & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lightbown, Ronald William. 1978. Sandro Botticelli. Vol. I. Life and Work, Vol. II. Complete Catalogue. 2 vols. London: Elek. [Google Scholar]

- Lightbown, Ronald William. 1989. Botticelli. Life and Work. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Magaluzzi, Silvia. 2003. Botticelli. The Artist and His Works. Florence: Giunti. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, Gabriele. 1967. L’opera Completa del Botticelli. Milano: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Marchini, Giuseppe. 1979. Filippo Lippi. Milano: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff, Stanley. 1987. Botticelli, Signorelli and Savonarola. Theologia Poetica and Painting from Boccaccio to Poliziano. Firenze: L.S. Olschki. [Google Scholar]

- Pope-Hennessy, John. 1952. Fra Angelico. London: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruda, Jeffrey. 1993. Fra Filippo Lippi. Life and Work with a Complete Catalogue. New York: Harry N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2019. The Symbol of Bed (Thalamus) in images of the Annunciation of the 14th–15th Centuries in the Light of Latin Patristics. International Journal of History 5: 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2020a. The bed in images of the Annunciation of the 14th and 15th centuries. A dogmatic symbol according to Greek-Eastern Patrology. Imago. Revista de Emblemática y Cultura Visual 12: 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2020b. Haec porta Domini. Exegeses of some Greek Church Fathers on Ezekiel’s porta clausa (5th–10th centuries). Cauriensia 15: 615–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2021a. Greek-Eastern Church Fathers’ interpretations of Domus Sapientiae, and their influence on the iconography of the 15th century’s Annunciation. Imago. Revista de Emblemática y Cultura Visual 13: 111–35. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2021b. The house/palace in Annunciations of the 14th and 15th centuries. Iconographic interpretation in the light of the Latin patristic and theological tradition. Eikón Imago 10: 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2021c. The bed in images of the Annunciation (14th-15th centuries): An iconographic interpretation according to Latin Patristics. De Medio Aevo 10: 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2021d. The symbol of the door as Mary in images of The Annunciation of the 14th-15th centuries. Fenestella. Inside Medieval Art 2: 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2021e. Christian exegeses on Ezekiel’s porta clausa before the Councils of Ephesus, Constantinople, and Chalcedon. Konstantinove Listy (Constantine’s Letters) 14: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-González, José María. 2023. Hortus conclusus. A Mariological metaphor in some Quattrocento Annunciations according to Church Fathers and theologians. Scripta Mediaevalia 16. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, René. 1911. Botticelli: Biographie Critique. Paris: Henri Laurens, Librairie Renouard. [Google Scholar]

- Zuccari, Alessandro, Giovanni Morello, and Gerardo de Simone. 2009. Beato Angelico. L’alba del Rinascimento. Roma: Musei Capitolini. Ginevra and Milano: Skira. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).