1. Introduction

The study of religious values is as old as the sociological study of religion. The research of the relationship between religious belief and values (already present in the work of Durkheim and Weber) has led to countless research directions and has enriched our knowledge of the religious worldview with many fundamental insights. However, little has been explored about how social spaces affect the values of religious people. We do not know enough about the extent to which particular social spaces offer opportunities for, or inhibit, the emergence of the specific religious values. A related question is the relationship between the use of space and religious values in some historical regions of Europe. This study seeks to better understand the role of social spaces in the emergence of religious values in the Central and Eastern European region after the communist era through a comprehensive study of values spanning nearly three decades.

The analysis focuses on the differences between the values of religious and non-religious people in different social spaces during this period. We explore social spaces in which the values of the religious are more separate from the non-religious, and the spaces where the values of the religious are inserted into the values of those who do not have faith. In this way, we interpret which social spaces offer opportunity for the emergence of specific religious values. This is a completely new direction in the sociological study of religion, which is based on the spatial turn, and which analyses the impact of social spaces on religiosity. The novelty of our analysis is therefore that we draw on the insights of spatial sociological analyses to examine how the social spaces within a society provide the opportunity for the development of specific religious values. As these theoretical changes have been little reflected in the study of religion, it seems worthwhile to briefly discuss the shift in perspective that the spatial turn has brought about.

2. Theoretical Part

Highlighting the importance of social spaces has become one of the most important research topics in cultural and social sciences in recent decades. This is linked to the recognition that previous social theories focused too much on changes over time and paid little attention to the important role that social spaces play in shaping social relations. Although the use of the term “spatial turn” first appears in Edward Soja’s Postmodern Geographies (

Soja 1989), the theoretical foundations of this new perspective can be traced back to the work of

Foucault (

2004),

Lefebvre (

1991) and

De Certeau (

2011). They were the first to describe the constitutive role of social spaces in social processes. For the purposes of our current analysis, the work of Lefebvre is worth highlighting in particular, as he has convincingly shown that space is not an external endowment but a social construction that is not only the arena of society but also shapes social relations. Social spaces thus also play a key role in shaping the preferences, strategies of action and values that the people who operate in them can display. He also states that social spaces can also be understood as spaces of power, insofar as the various spaces also represent relations of domination that are capable of influencing the actions of the actors in the spaces. Thus, for Lefebvre, the spaces of society are seen as domains of power that also influence the values of the people in each space.

Among the authors who rethink the role of space, we highlight the work of De Cer-teau, who also emphasises the constitutive role of spaces. There is also a similarity between these two authors in that he also sees social spaces as a factor of domination that can influence the actions and preferences that take place in them. De Certeau’s theory, on the other hand, is also a kind of praxis theory, concerned with the ways in which social actors can evade the power order imposed on them and how they can express their own values in their actions and choices. Translating this insight into our present research, we can thus also examine which social spaces, instead of those determined by the relations of domination of production, will be the social spaces that offer the possibility of a religious cosmology and a specific religious value system.

These considerations also bring us closer to sociological research on religion, insofar as they also lead us to research on the social expression of religious values. Here, we refer to Linda Woodhead, building on Certeau’s theory, who also analyses the emergence of a particular religious perspective as a tactical religiosity, as a perspective that seeks to live out its own values in a milieu defined by secular domination (

Woodhead 2016). However, the analyses of Woodhead and others (

McGuire 2008,

2016) have examined the relationship between religiosity and religious values using essentially qualitative methods. There has been no meaningful attempt to analyse the relationship between social spaces and the emergence of religious values using quantitative data. Our study is related to the analytical tradition of spatial sociology, which investigates the influence of social spaces on the emergence of specific religious values and thus analyses which social spaces enable their expression and which spaces marginalize it.

In this way, our analysis also reflects the process of secularisation. Its theorists (to quote them) have identified modernity with the spread of secular values and the decline of a value system expressing a religious cosmology. Perhaps one of the most prominent theorists in this field, Charles Taylor, has spoken of a secular age outright, and has identified the modern moral order expressing secular values as the main feature of this age (

Taylor 2007). As a consequence, the privatisation of religion (

Luckmann 2003) has been highlighted, but little reflection on aspects of spatiality has been made in their analyses. In our view, this trend is only evident to Bryan Wilson, who draws on Parsonian social theory to account for the impact of secularism on the spatial role of religion (

Wilson 1966,

1982). Although Wilson makes no attempt to prove this thesis empirically, his approach will be an important starting point for our recent empirical analysis. The novelty of our study, then, lies primarily in the fact that it seeks to verify, over a longer time span and using representative samples, that the emergence of specific religious values is fundamentally influenced by the opportunities offered by particular social spaces for their development.

In the framework of this analysis, we rely on three theoretical premises which, although they capture the characteristics of modern society from different perspectives, can be drawn together into an interpretative framework for the study of the social spaces of religious values. The starting point of the research is the perspective of the spatial turn, which points to the role of social spaces in the value systems of actors. We also built on the insights of Bryan Wilson’s earlier research in the sociology of religion, which showed different social spaces for the assertion of secular values. Thirdly, we draw on Jürgen Habermas’ communicative theory of action, which depicts two fundamentally different spaces in modern society. These theories have provided the impetus to examine the spatial aspects of religiosity in the Central and Eastern European region.

Our study starts from the insight of the author of spatial turn that people’s material environment plays a role in the attitude of actors to the world and thus to values (

Soja 1989,

1996). Thus, the spatial characteristics of society are seen as a social construction that affects their creators (

Lefebvre 1991;

Giddens 1995;

Löw 2001;

Knoblauch and Löw 2017). Different social spaces can result in different systems of relationships and different value orientations. In our analysis, we assume that different social spaces offer opportunities for different interpretations. They can be interpreted as representational spaces that express different social values, traditions, collective experiences, experiences, and desires (cf.

Schmid 2005;

Knoblauch and Löw 2020).

The analysis examines the extent to which social spaces offer opportunities for religious people to have a different worldview from non-religious people. In this respect, we explore the relationship between the use of space and values, i.e., we apply the perspective of the spatial turn in sociological research on religion. On the other hand, the study of the use of space and values has its antecedents in the study of religion. First of all, Bryan Wilson’s analyses (

Wilson 1966,

1982) have assumed that in the process of secularization, secular values appear in society with different weights, and this process has a fundamental impact on the social spaces in which religious people’s own worldviews may appear. Wilson’s research not only found that the transformation of society has given more space to secular values, but also addressed the fact that the two different spheres of society, the ‘societal system’ and ‘community life’, are characterised by different value traits (

Wilson 1982, pp. 148–79). Wilson’s theory distinguished between the different value orientations of the ‘rational society’ and the ‘moral community’, pointing out that the emergence of a particular religious value system is more likely to occur in the ‘moral community.’ To this extent, he pointed out that social spaces have an influence on the values of the religious. He did not, however, reflect on the insights of the spatial turn, and no empirical verification of this theoretical thesis was provided. The novelty of our analysis is that we attempt to analyse the relationship between social spaces and religious values over a longer time span in the Central and Eastern European region.

In operationalising the social spaces, we started with Wilson’s categories (rational society and moral community), but we felt justified in including a more complex social theory to capture the different social spaces. Here, we relied on Habermas’ communicative theory of action, which perceived a dichotomous structure in the interpretation of modern society (

Habermas 1995). This conception, which is very similar to Wilson’s analysis, distinguishes between social spaces organised by modern rationality and the largely independent personal space of social actors. On the other hand, Habermasian theory also offers the possibility to capture the spheres of the lifeworld in a more differentiated way than the Wilsonian model. Indeed, the Habermasian concept of the lifeworld, with its focus on intersubjectivity, described the structure of personal relationships and the influence of this on values (

Habermas 2018). This is the basis for distinguishing the relationship of the personal sphere to other people and to God in a more detailed analysis of the lifeworld.

Building on this theoretical framework, and thereby also reflecting the perspective of the spatial turn, in this paper, we distinguished in every society the social spaces designated by the system and the lifeworld, which evoke diverse value orientations in our interpretation. Focusing on social spaces with different structures, we examine the distinct structure of the values of religious people in the systematic organizations of modernity (in the social spaces of economy, work, and administration) and in the lifeworld, which represents direct human relationships. In this study, we explore which social spaces where the particular values of the religious worldview manifest and which are the ones where religious people’s values is close to non-religious people’s. Through all of this, we have sought to capture the constant and the changing features of religiosity in the Central and Eastern European region in a more nuanced way by incorporating new analytical aspects.

There are two different ways of looking at the values of religious people. On the one hand, following Schwartz and Inglehart, religious values are analysed on the basis of different value orientations (

Schwartz and Huismans 1995;

Schwartz 2012;

Norris and Inglehart 2004). This research direction tries to capture the value orientation of religious people on the basis of their relationship to certain values. On the other hand value orientations are interpreted concerning violations of norms. Different forms of norm violation provide an opportunity to examine the correlation between religiosity and norm violations. Thus, it can be answered which types of violations religiosity is a structuring factor in the countries of the region (

Finke and Adamczyk 2008;

Halman and van Ingen 2015): which norm violations are judged differently by religious and non-religious people. This line of analysis thus examines the values of religious and non-religious people in terms of their relationship to norm violations and interprets the differences between the two groups. Our current research is related to this analytical tradition. This perspective offers the possibility to obtain results that cover several countries in the region and trace the changes in values over three decades.

Before further analyses, it is worth briefly touching on the relationship between the notions of value and norm. Our use of the notion is based on insights from the sociological literature on value and empirical research that also reflects on it. For the former, we have relied above all on the analyses of

Hans Joas (

2019). Joas argues that, although the terms value and norm have different meanings, they represent two sides of the same phenomenon. Norms are restrictive in that they consider certain means of action to be morally or legally unacceptable and prohibit certain ends of action. Sociological studies of values in relation to norm violations focus on this aspect. On the other hand, the relationship with certain norms and norm violations also reveals which values are considered attractive by actors and which extend the scope of action. (For example, the rejection of abortion as a restrictive norm expresses, on the other hand, the value of following divine command as an attractive value for the religious person.) This distinction is validated in more recent sociological research on religion (

Finke and Adamczyk 2008;

Adamczyk 2022), when the relation to norm violations is used to refer to the values of religious and non-religious actors. This explains why, in this study, we consider norms and values as two sides of the same phenomenon and infer people’s values from the relations to norm violations.

In studying the religious values in the Central and Eastern European region, we included the countries that belong to the core area of a region. Our choice was that we wanted to compare the data and changes of countries with more or less related traditions, i.e., similar social development. Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, and Croatia belong to the intermediate region of Europe where the medieval social development created the social orders (cf.

Szűcs 1985;

Maczak et al. 1985). In the Central and Eastern European region, the dawn of modernity reacted to the influence from the West with some delay and with other structural features (cf.

Gerschenkron 1962;

Berend 1996;

Janos 2000). The six Central and Eastern European countries also have in common that the slower process of civic development was broken in each of them by forty years of Soviet rule. However, since the fall of communism, they have all joined the European Union. Another common feature of the six countries in the region, that they all represent Western-type Christianity; largely Roman Catholic, but with some Protestant influence. In other words, the main reason for including these countries in the analysis is that similar social historical development and similar social experiences have shaped a more or less similar value orientation. Hence, the parallels are stronger than in comparisons with countries outside the region. This does not mean that the degree of religiosity is the same in these countries (see later analysis), but the role of social spaces in the development of religious values is more similar. Our analysis focuses on the latter, the influence of social spaces on the emergence of religious values.

3. Hypotheses

By operationalizing the theoretical starting point, in this paper we investigate which social spaces of society affects the values of religious people. Which will be the social spaces where the specific perspective of religious persons can be better expressed or even strengthened? Previous research has shown that in Europe, the once important role of the religious worldview in moral judgement (

Lenski 1963;

Rokeach 1969a,

1969b;

Schwartz and Huismans 1995) was increasingly pushed into the background (

Storm 2016), and the hard indicators of a secularized society (such as education, family status, and age groups) have become more important in the transmission of values (

Scheepers et al. 2002a,

2002b;

Sieben and Halman 2014). We hypothesize that the traits of the secularized public (

Taylor 2007), which overshadow religious values, are most pronounced in the case of violations of norms that are related to the systematic organization of society. Here, the world of work has a special role which is determined by the rationality of production. This represents the most secularized social space of modernity, where economic rationality leaves little room for the expression of transcendent contents, which play such a significant role in the religious worldview.

Here, the research interpreting the value system examines the violations of the norms related to the economy, or in a broader sense to production, redistribution and administration. We examine the value aspects of this social space with the related norm violations (illegal use of state benefits, tax fraud, bribes, fare evasion). We assume that the fundamentally secularized medium of production determines the relationship of individuals to norms (and their violation). Especially in a region where the socialist manufacturing industry, which characterized the earlier era of the region, and the omnipotent state power further “desacralized” these social spaces. Thus, the first hypothesis of the research is that the values of religious people will not show major difference in terms of violations of the norms (illegal use of state benefits, tax fraud, bribes, fare evasion) related to the systematic organization of society, production and administration (Hypothesis 1).

On the other hand, the complex system of modern society can also be characterized by social spaces where there are significantly different relations from the social space of economy and administration. These are the social spaces where cultural traditions that are relatively independent of the production process, individual or group alternative social interpretations are more likely to appear (

Habermas 2018). This also gives rise to privatized forms of religiosity (

Luckmann 2003;

Davie 2002,

2005). We think that religious transcendence and specific religious values can be found primarily in this social field. Based on this, we assume that the specific religious worldview is more pronounced in the social space of privacy, in everyday life.

We assume, this is the social space that allows more space for the survival of the Judeo-Christian religious tradition, as well as for the stricter ethical-moral principles, for whose enforcement the social space of production leaves little room. These structural features, which also exist in the development of Western European societies, are especially valid in the Central and Eastern European region. This is because the communist period made the practice of religion largely semi-formal and emphatically pushed the experience of religious experience back into the space of private life (

Tomka and Zulehner 1999;

Zrinščak and Nikodem 2009). Thus, in this region, in addition to the desacralized nature of production, political ideology also confirmed that religious values could unfold primarily in the realm of lifeworld.

Since our study is based on the assumption that the specific religious worldview and values appear primarily in the social space of the lifeworld, it seemed reasonable to examine this social space in more detail. In order to grasp the idea of the religious values of Central and Eastern Europe in a more complex way, we have separated the different dimensions of lifeworld. Our research, therefore, categorized issues related to personality, relationships, the sphere of intimacy (cf.

Habermas 1995;

Halman and Pettersson 1999) and issues related to the sanctity of life. In our interpretation, the sphere of intimacy has emerged as a key ethical issue in both Jewish and Christian traditions, and as such, it may express the particular value of religious people that is less affected by the instrumental rationality of modern society. Based on this, we assume that the specific value system of religious people is much more likely to appear in connection with the value orientation measured by the violation of the norms of privacy in private relationships and relationships (divorce, casual sexual relations, prostitution). We formulated the hypothesis that religious people will judge these violations of norms related to privacy and personal life more strictly in their answers than non-religious people (Hypothesis 2).

Another group of violations related to the lifeworld are decisions related to life and death (cf.

Scheepers and Van Der Silk 1998). Here, those ethical issues are articulated that do not directly affect the activities of production or even those of everyday life, however, they may be more important to a person who assumes a transcendent. In this perspective, decisions related to life and death are outside the competence of the human actor and are closely related to respect for life. In this dimension, we have included the value-related questions that by religious people are interpreted as the questions of the sanctity of life. Given that in these contexts, a transcendent-oriented religious person is more likely to face the idea of his own finality and limited freedom (against God), we assume that in the case of violations of the norms of respect for life (abortion, euthanasia, suicide), religious people formulate a stricter judgment than non-religious ones (Hypothesis 3).

Our study analyzes the changes of nearly three decades from the fall of communist rule to the present. An important research question for us is how the impact of religion on norms changes during this period. In our view, since the fall of communist power, a dual effect has been observed in the region, which has the opposite effect on the role of religion. On the one hand, with the change of regime, the role of Western societies was strengthened, which increases the secularization effects in the region. On the other hand, the regime change provides a greater opportunity for the open representation and participation of religious values in public life. The former reduces the impact of religion on values, while the latter strengthens it. We, therefore, assume that the two opposing tendencies balance each other out, and thus we do not expect a significant restructuring in the impact of religion on any of the analysed norms (Hypothesis 4).

Our analysis focuses on the impact of social spaces on the emergence of religious values, but we also analyse the impact of the strength of religiosity. The need to do so is supported by the fact that the degree of religiosity varies across countries, so that it is assumed that this characteristic also influences the emergence of specific religious values in different social spaces. We expect the role of the strength of religiosity to manifest itself differently in different social spaces. Nevertheless, we also hypothesize that the different degrees of religiosity in the systematic organization of society, production and administration in the countries of the region under study will not result in significant differences between the values of religious and non-religious individuals (Hypothesis 5a). We expect that differences in religiosity between countries may be more strongly reflected in the social space of the lifeworld (Hypothesis 5b).

4. Data and Methods

We used 4 waves of the European Values study (EVS) data in our analysis. The first EVS round was conducted in 1981, but none of the East-Central European countries were participated in that round. The first wave we used in this paper were the surveys from 1990–1993 (referred to later as 1990). The next wave was conducted between 1999–2001 (referred to as 1999), then 2008–2010 (referred to as 2008) and the last one in 2017–2020 (referred to as 2020)

1. We included 6 countries: Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia and Hungary, but Croatia was not included in the 1990–1992 wave

2. The smallest sample size was 987 and the largest was 2109. All the surveys were nationally representative ones. The data were collected through face-to-face interviews. The 1990–1999–2008 waves were already available in a joint file with unified variable names. We added the 2017 surveys to this file with harmonized variable names, so we had all the data available in one integrated file.

We had one main independent variable—religiosity; and 3 groups of dependent variables: sanctioned norm violations, which relate to the systematic organisations of society, and defence of life and private life and sexuality variables, which relate to the social domain of the lifeworld. We first tried to fit confirmative factor models to create the indices, but the fit statistics were quite low in all the cases. Although this made the empirical analysis more difficult from a theoretical point of view, this is not surprising. We cannot assume that our indices can build up in the same way in 6 different countries through 4 waves. It is especially true in a time period, when rapid changes happen.

To create our measures, we chose a simple method here. We created the indices by averaging the selected indicators. We calculated Cronbach alpha statistics to measure the validity of our indices. The first dependent variable was the sanctioned norm violations. The state-sanctioned norm violations were calculated by three variables, all measured in a 1–10 scale. Lower value means the rejection of the norm violation.

The average CA value was 0.69. In most countries the CA value was lower in 1990 than in later waves. The worst value was 0.42 in Poland in1990 (see

Appendix A Table A1).

The second dependent variable was about the defence of life. We used three variables to calculate this index, all measured in a 1–10 scale. Lower score means stronger defence of life.

Abortion

Euthanasia

Suicide

The average CA value was 0.68. The CA varied between 0.53 and 0.83 (see

Appendix A Table A1).

The third group of dependent variables was about private life and sexuality. We planned to include the following variables all measured in 1–10 scales:

casual sex

prostitution

divorce

However, the casual sex question was not asked in the 1990 surveys and the prostitution question was not asked in 1999 in three countries: Hungary, Slovakia and Poland. So, we decided to fit separate models to all the dependent variables in this dimension and did not create a joint index.

The main independent variable was religiosity. We created a complex variable to measure it, which encompasses several dimensions of religiosity: religious practice, religious self-classification, and religious belief. First, we calculated a belief index by averaging the following 4 items (measured in 0–1 scale)

We recoded the “Are you a religious person” variable into the following 3 categories:

Additionally, we also standardized the “Pray to God outside of religious services” question to have a min. value 0 and a max. value 1.

After this standardization process, we calculated the average value of the belief index, the religious person question and the praying variable. The min. value of the final religious index is 0, the max value is 1.

In the regression models we used three additional socio-demographic variables: gender (1: female, 2: male), age category (1: under 25, 6: above 65+) and education. We measured education with the following variable: “At what age did you complete your education”.

We applied linear OLS regression models in the case of all dependent variables. We fitted two models for all dependent variables. In the first model, we added religiosity, gender, age, education as a continuous and a year and country as a factor variable. In the second model we added the interaction term of religiosity with the year and the country variable. With the interaction term we measured the variation of religiosity index between waves and countries. For easier interpretation of the results, we calculated the predicted marginal means of the dependent variable per waves and countries on different level of religiosity.

5. Research Results

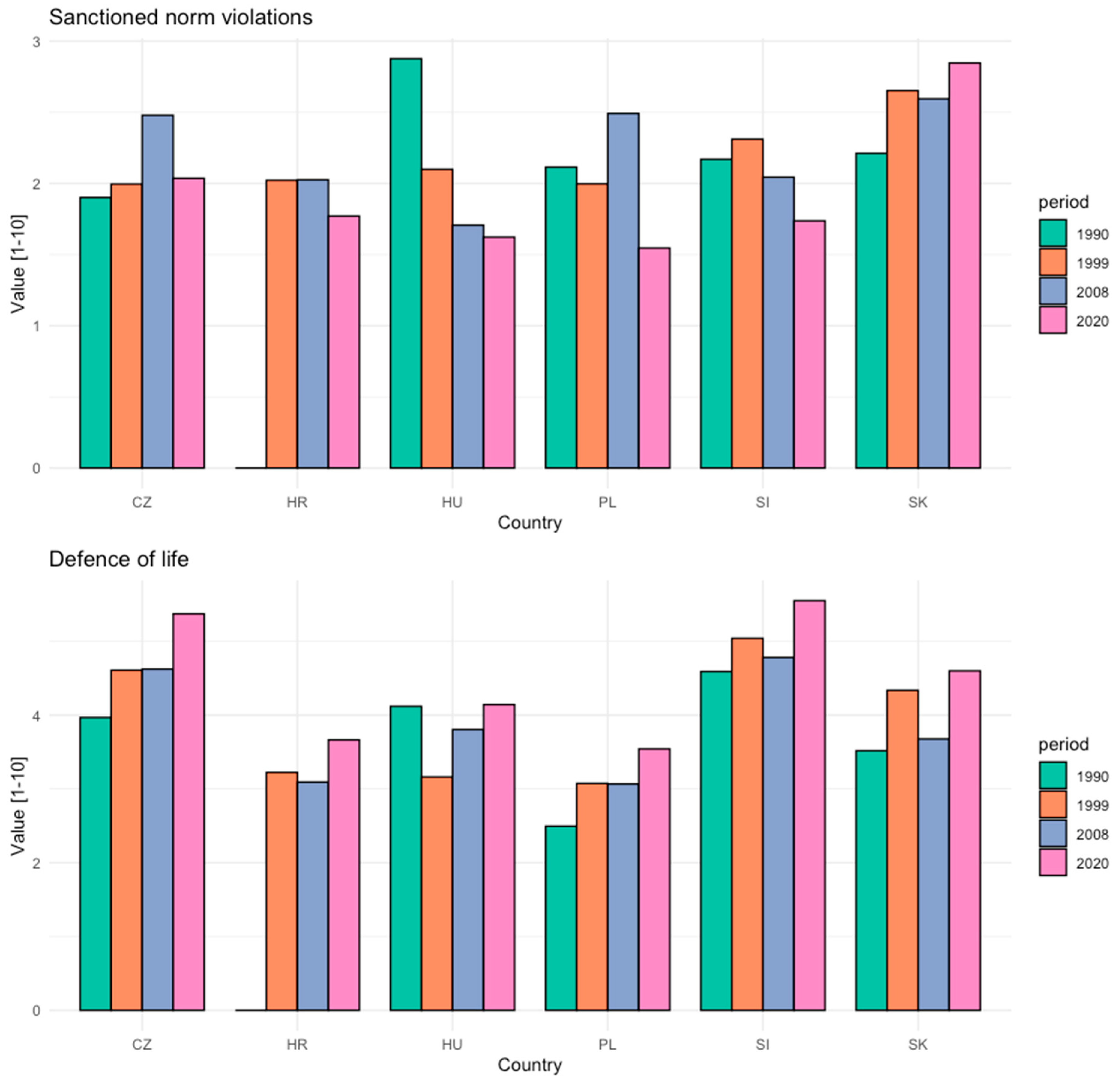

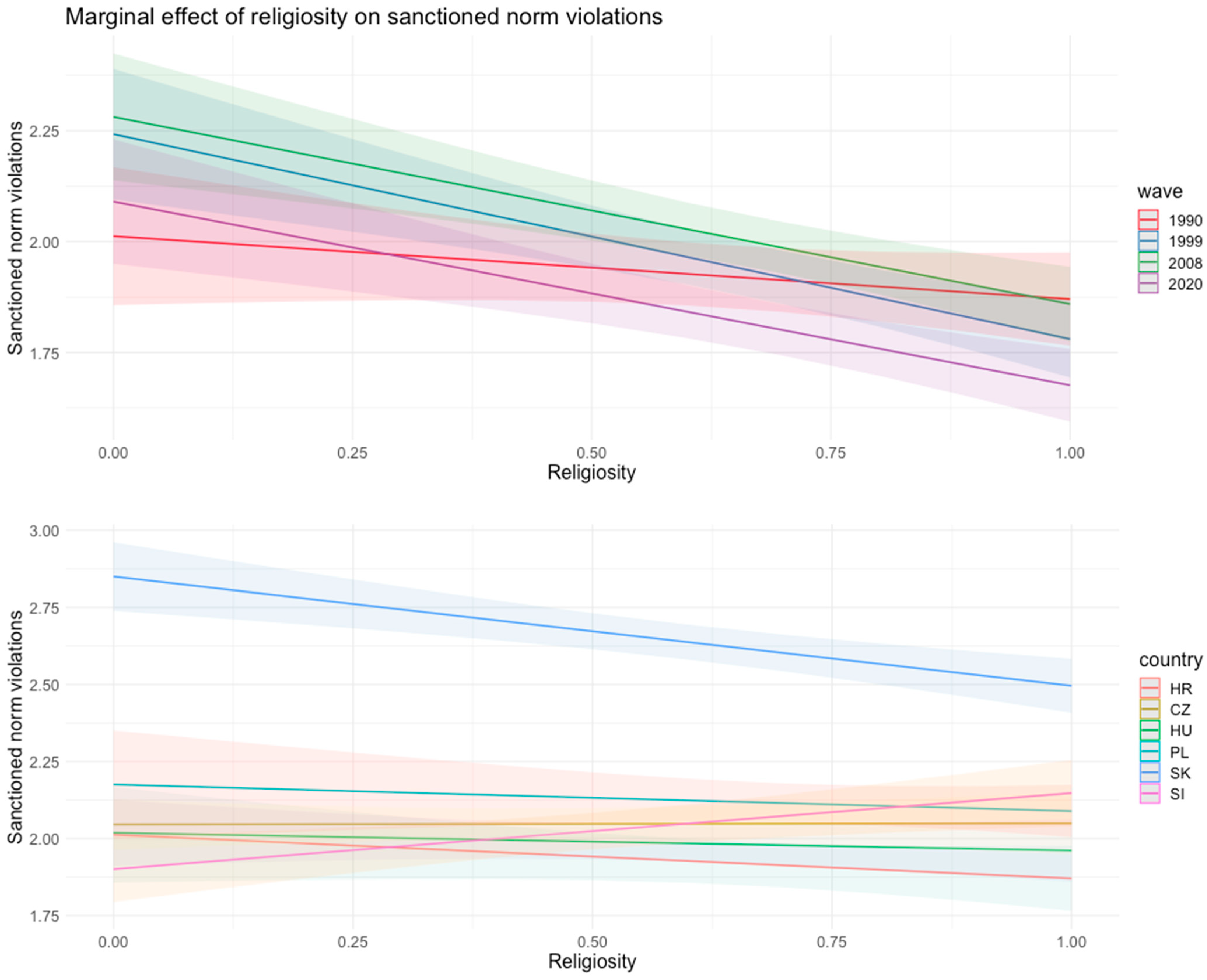

The research results showed that in the Central and Eastern European region, the role of religiosity in people’s value judgments differs significantly in each social space. In the case of violations of norms like the illegal use of state benefits, tax fraud, bribe, which are all related to the space of the economy and administration (systematic organization of society), religiosity had very little influence on the answers of respondents, the standardized beta value just 0.06 (see

Table 1).

The B value for religiosity was −0.3, so on the scale of 1–10, there was a total of 0.3 difference between non-religious and religious people. In this social space, religious people follow the value judgment of the secularized society with little difference, and their values differ only slightly from the those of non-religious people. This confirms our Hypothesis 1, which assumed that the values of religious people would not show a significant difference in the case of violations of norms related to the systematic organization of society. This social space, therefore, does not allow the emergence of a specific religious values, since the norms of the religious are essentially the same as those of the non-religious. The effect sizes were similar when we repeated the analysis with the three initial religiosity variables (see the

Supplementary Materials).

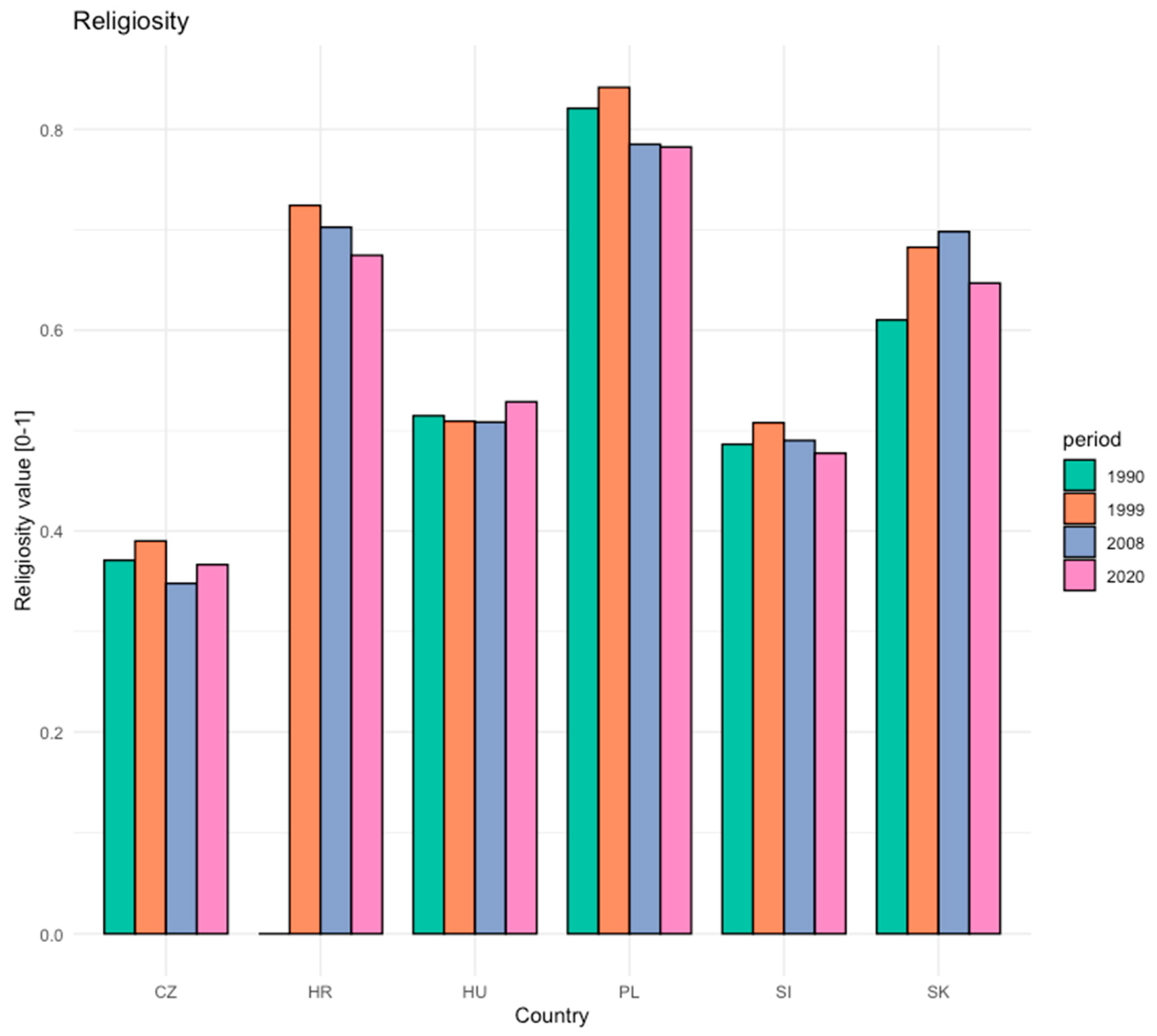

It should be emphasized that the countries of the Central and Eastern European region with different degrees of religiosity (see

Figure A1 in the

Appendix A) share a close to similar pattern in their perceptions of violations in the space of production and administration, based on the detailed analysis of the interaction effect of religiosity and country and year (see the predicted marginal means per country and year in

Figure 1). This shows how strong the influence of this social space is for all the countries in the region. It is also evident from the fact that, although the degree of religiosity varies between countries, there is only little variation in the characteristics of religious values in this social space.

The Poles, being the most religious (cf.

Pawlik 2017) show essentially the same pattern as the most secularized Czechs, or (in terms of religiosity) the Slovenes in the middle of the scale (cf.

Flere and Lavrič 2007) or the less religious Hungarians (see

Figure A1 in the

Appendix A). It is virtually true of every country and of the whole period that religiosity has a small negative or even a small positive effect (see Slovenia) on the perception of state-sanctioned violations. Some difference is observed only in the case of the Slovaks, whose value judgement is markedly different from that of non-religious people’s, in the recent EVS waves. This is explained by the fact that in addition to the liberalization of violations (see

Figure A2 in the

Appendix A) in recent years, religious people in Slovakia have better retained their stricter judgment for these violations (cf.

Tižik 2017). Overall, in the Central and Eastern European region, religiosity typically has a very little role in shaping people’s value judgements about the violations of norms related to the system defined by instrumental rationality, although the correlations became somewhat stronger after the 1990 wave.

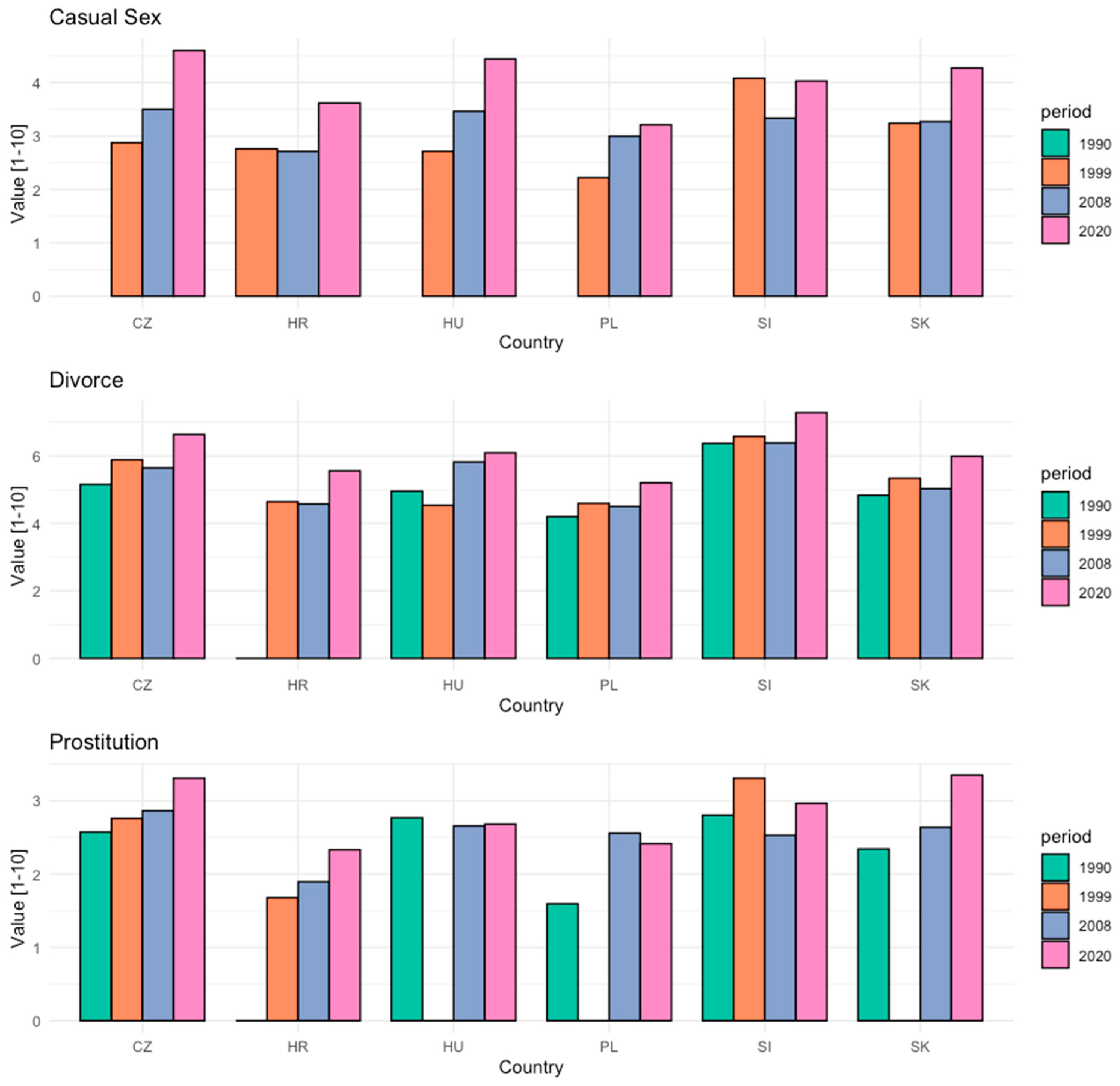

The value system of religious people shows a completely different picture in the case of violations of norms that are related to privacy, and to sexuality, in the social space of lifeworld (see

Table 2).

The research results reveal that in all the three sub-questions examined separately, religious people judge these violations more strictly. This confirms Hypothesis 2. In their answers, religious people tend to (strongly) disapprove of violations of norms related to privacy and personal life. This provides convincing evidence for our hypothesis that, largely irrespective of the degree of religiosity, in all the countries studied, a particular religious norm, different from the perception of non-religious persons, is manifested in the social space of the lifeworld. This in turn shows the influence of social spaces on the emergence of values.

An interesting trend has emerged in relation to the three variables examined here. In all the three issues (prostitution, casual sexual relations, divorce) the view of religious people was stricter than that of non-religious people. Of these violations of norms, it was divorce—the failure of relationship in the sphere of personality—where the value judgements of religious people diverged sharpest from those of non-religious respondents. However, they were relatively less strict in the assessment of prostitution (see the Beta values in

Table 2). We repeated the analysis with the three initial religiosity variables. We found similar effect directions with minor differences between the effect sizes. The effect size was slightly larger in the case of self-evaluation of religiosity level compared with the belief index. This tendency was similar in the case of all the above sub-questions.

In the assessment of prostitution, religious people are fairly united in the countries of the region. Over the three-decade period under study, this type of misdemeanor is uniformly judged more severely than norm violations in the space of production and administration (see

Figure 2). As in the aforementioned social space, there are few differences between the countries, although the least religious Czechs and Hungarians have slightly smaller differences compared to non-religious ones. In the region, however, religious people represent their values diverging from non-religious people’s values in a constant and uniform way. The difference was small between the waves, but we found a slightly stronger effect in the case of last EVS wave.

The different values of religious people are noticeable in the assessment of casual sexual relations (see

Figure 3).

According to available data for the last two decades, in Central and Eastern Europe, the divergence of opinion between religious and non-religious respondents is even more substantial about casual sex than in the case of prostitution. Thus, besides the unified and one-way liberalization of the overall social perception of casual sexual relation (see

Figure A3 in the

Appendix A), it is the religious people who retain a stricter judgement expressing social traditions in this regard. Here, it should also be emphasized that religiosity of different intensity in the region results in few differences in the values of the countries in the region. In terms of religiosity measured along our indicators, deeply religious countries like Poland and Croatia (cf.

Marinovič and Ančić 2014;

Zrinščak 2017), the difference between religious and non-religious people is slightly more significant than in the case of the less religious Czechs or Hungarians. However, the data for the six countries are surprisingly consistent over the two-decade period of the three EVS surveys, although the correlations were slightly stronger in 2020. They show the same different values from those of non-religious people as the ones that can be seen in other violations of norms related to the lifeworld.

Divorce—breaking the norms of relationship—belongs to the most personal space of life. Of all the dimensions examined, research findings show the largest difference between religious and non-religious respondents in this issue (see

Figure 4). In the Central and Eastern European region, this violation is much more severely judged by religious people. The greater rejection of divorce among religious people is reflected in an social space that is less and less disapproved of by society (see

Figure A3 in the

Appendix A). However, the specific value system of religious people is the most evident here, in the personal aspect of the lifeworld. The data clearly illustrate that also in this respect, we can speak of a fairly constant difference related to social traditions and deep structures that go beyond the history of events. On the other hand, the different traditions of the countries in the region also influence the extent to which religious values affect the moral judgement of the actors. The different historical tradition presumably determines the fact that the divergent religious value judgement present in the most secularized Czech Republic in the region (cf.

Hamplová and Nespor 2009) differs more significantly from the characteristics of other countries in the region. On the other hand, the stronger presence of religious tradition also explains that the most religious Poland (cf.

Ramet and Borowik 2017) has the largest difference in perceptions of divorce between religious and non-religious respondents. Despite these differences, it can be concluded that in each of the countries studied, it is the social space of the lifeworld where the values of religious persons are expressed.

There is also a stronger religious value system in the field of lifeworld in the case of violations of norms related to the protection of life (see

Table 3).

In the Central and Eastern European region, religious people uniformly condemn abortion, euthanasia, and suicide more strongly than non-religious people. Based on the regression model, there is a 2.3 point difference between the two groups on a 0–10 scale. This confirmed our Hypothesis 3. The distinctive religious worldview in the space of lifeworld is also constantly present during the thirty-year period under study

3.

Differences between the countries are similar to those experienced in questions concerning privacy (see

Figure 5).

Regardless of the degree of religiosity, the Croatian, Slovak, and Slovenian responses show a similar pattern that are different from non-religious ones for the entire period. On the other hand, the difference is smaller in the case of the most securalized Czech Republic and the less religious Hungary while in Poland, which has the most religious and strictest abortion laws in the region (cf.

Czerwinski 2004), the religious values are the strongest.

Our results examining the different dimensions of violations of the norms also proved that the effect of religion on norms shows a relatively high consistency in the studied period. Still, we could also measure a difference between the 1990 and later waves. During the transition period, the effect of religiosity on different norm violations was slightly weaker than in the following period, but we did not find differences between the later waves. This result weakly confirms our H4 hypothesis. It seems like the combined effect of the secularization of Western societies and the now overt presence of religiosity does not seem to have brought much rearrangement to the role of religion in values after the transition period.

Thus, we can see a double trend in the examined time frame. Our research thus also draws attention to the fact that these two social phenomena are linked in the different order of values of religious people and non-religious people. The reason for this is that in the Central and Eastern European region, the values of religious people are becoming liberal in a similar way to non-religious people’s. In other words, the values of religious people are also aligned with the “modern moral order” (

Taylor 2007) and this also creates a more tolerant value system for violations of norms related to the lifeworld. On the other hand, this liberalization in the order of values does not dissolve the stricter values of religious people, which are so different from non-religious people’s value system. This explains the fact that in the Central and Eastern European region, religiosity of unchanged strength is constantly associated with a different order of values from that of non-religious ones. It shows a deep-structural feature that expresses a value system that is invariably present and different in intensity from that of non-religious people’s.

Our last hypothesis was about the differences between countries. The overall tendencies were quite similar in all the studied dimensions. The effect of religiosity on different norms was weaker in less religious countries, like Czech Republic and Hungary, and in some cases Slovenia, and more robust in more religious countries, especially in Poland and Croatia. These tendencies were strong in the case of norms about privacy and personal life and the norms of respect for life, which is an explicit confirmation of the H5b hypothesis. We found minor but still measurable differences in the case of norms related to the systematic organization of society, production, and administration, where we did not expect such a difference, which is a rejection of the H5 hypothesis.

6. The Religious Lifeworld of Central and Eastern Europe—Conclusions

The values of religious people of the region are thus separated from the values of non-religious people in a society with a changing value structure. The main feature of this religiosity is that it does not appear equally in different social spaces of society. Our study proved that in the space of production and administration, in the systematic organization of society, religious people do not have a different order of values, but mostly follow the perceptions of non-religious people. In this we see the effect of a dual process, the desacralizing feature of Western instrumental rationality and the communist past. The space of production and redistribution of social goods has thus been secularized to such an extent that the once so important values (present above all in the command not to steal) in the Judeo-Christian religious tradition are perceived almost equally by religious and non-religious people.

The reason for this Is presumably to be found in the fact that bureaucratic rationality deeply interweaves the world of these social spaces (

Lefebvre 1991, pp. 258–60) and pushes the appearance of values related to the transcendent into the background. This reinforces our hypothesis that social spaces are fundamental to the representation of values. Thus, social spaces also have a significant influence on where specific religious values are more likely to manifest themselves. Thus, for the first time, our research is able to empirically verify the influence of social spaces on the emergence of religious values through quantitative database analysis. Another novelty of the study is that the impact of social spaces is similar in countries with more or less the same social history and that differences in the degree of religiosity have only a minor impact. In this connection, our research has shown that this feature, which is present throughout the region and spans the entire period under study, is not substantially affected by the different degrees of religiosity in the individual countries. As the latest research (

Bognár and Kmetty 2020), we perceive the marginalization or even the cessation of a specific religious value system in the Central and Eastern European region in terms of the values related to the social spaces of production and administration.

On the other hand, our research also revealed that this feature of religious values does not mean that religiosity, defined through several dimensions, has lost its significance. In the individual differences between the countries in the region (cf.

Polak and Rosta 2016), a religiosity of unchanged intensity has been observed throughout the entire period. Additionally, the main feature of this religiosity is that its order of values, which is different from that of non-religious people’s, appears in the values related to the realm of lifeworld. The lifeworld, a social space different from the space of production and administration, is the social space where a specific religious value system appears. This includes the realm of personality, intimacy, and the possibility of subjective interpretation of the world and our fellow human beings. In this system of relations, the actors themselves are able to actively shape the spatial conditions, and this may offer an opportunity for everyday actors subjected to different systems to come up with new interpretations against expectations (

De Certeau 2011;

Shields 2013). It is the social space of the lifeworld separated from the system that provides an opportunity for the development of religious experience and values. As a result of previous actions, this is the social space that makes it possible to reinforce and encourage types of actions different from the system (

Lefebvre 1991;

Löw 2001;

Knoblauch and Löw 2017). The effect of religiosity on lifeworld was somewhat different in the analyzed countries; we found a more substantial effect in the case of more religious countries and a weaker one in the more secularized countries. This is a clear sign that not only individual religiosity is essential, but also the national context. In more secularized countries, religion lost its role in defining the norms and values of people.

The research results revealed that personal space plays a crucial role in the emergence of a specific religious value system. Religious values, thus have a focus on internal and personal experiences, which can be compared to the spiritualization of religion across Europe in recent decades (

Davie 2002,

2005,

2006;

Lyon 2000;

Heelas and Woodhead 2005;

Houtman and Aupers 2007;

McGuire 2008,

2016;

Voas 2009;

Storm 2009,

2016;

Cortois et al. 2018). The striving of the ego for wholeness, the increased role of personal cosmology also explains why religious values can emerge not in the spaces of production and administration but in the social spaces of intimacy and the protection of life. Our research showed that in the Central and Eastern European region, a specific order of values of religious people appeared in the values related to relationships, intimacy and the sanctity of life. The strength of this religiosity is shown by the fact that in contrast to the trend in other regions of Europe (

Storm 2016), the correlation between religiosity and the abovementioned values does not decrease here.

The lifeworld is the main social space for the expression of specific religious values. This is also reflected in the fact that, of all the factors examined, the religious factor has the greatest explanatory power for the norm violations linked to this social space: religiosity is more strongly correlated than gender, age and education (see

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3). All this shows the strength of the religious lifeworld that preserves its values even in changing social circumstances. All this shows that the process of secularisation has had different effects on the possibility of representing particular religious values in different social spaces. We have seen that the social space which is dominated by modern rationality has offered little scope for these specific values, while the much more traditional social space of the lifeworld (cf. Wilson’s ‘morality community’) has offered more scope for these values. This again points to the role of social space in influencing religious values.

We can get a more nuanced picture of the features of religiosity in the region if we examine the role of values related to the lifeworld in more detail. Our research has shown that religious values have two main characteristics. On the one hand, a set of values different from that of non-religious people appears primarily in those social spaces that directly affect the personal sphere of religious people, and which means stronger personal involvement and emotional commitment. This explains that the markedly different values of religious people do not necessarily appear in relation to acts deeply condemned in the Judeo-Christian tradition (prostitution, casual sexual relations), but where the violation affects the privacy including the relationship of the religious person. This religious order of values was expressed in the strongest rejection of divorce.

Another major feature of the religious lifeworld in the Central and Eastern European region is that it is much more sensitive to violations related to the sanctity of life than to violations related to sexual behaviour (prostitution, casual sex) condemned in the religious tradition. This order of values shows that the religious point of view does not necessarily manifest itself in a set of values more rejected by society. According to our research results, the religiosity of this social space does not mean that religious people would generally judge violations of norms that are socially condemned more severely or would be more tolerant of violations of norms that are less socially condemned. In the case of this kind of traditionalism the strongest difference between religious and non-religious people would have been in the case of prostitution, which is more rejected in society, and we would have had the smallest difference in divorce. Instead, we see a set of values that displays traditional religious cosmology and at the same time it also responds to the changed relational system of modernity.

This religious point of view retains the attitude present in the Judeo-Christian tradition, in which making a decision on the question of life is not up to man, but it depends on the transcendent. According to this conception taking life cannot be our personal decision, and it cannot fit in with the “modern moral order”, which in this regard is increasingly permissive and prefers an attitude that emphasizes personal freedom. Our research findings suggest that those believing in religious cosmology do not seek consensus with other social actors in this regard, but in line with their worldview, they deviate more markedly from the values suggested by the secular public. That is, they enforce less cost–benefit type of thinking. As a result, in the case of violations of norms related to the protection of life in the Central and Eastern European region, religious people take a more markedly different point of view from non-religious ones. Again, this is linked to the fact that the social space of the lifeworld offers the possibility of expressing specific religious values.

This religious cosmology also appears in the concept of modernity. It explains why religious people’s judgements are not so strict concerning other violations of norms related to the lifeworld. It also explains why they do not differ as much from non-religious people’s judgements as in the case of violation of norms related to the protection of life. We think, it is because this religious cosmology assumes a transcendent over man, which restricts his decisions making in the case of the final, great decisions concerning life. This hierarchical cosmology explains the large differences in the protection of life between religious and non-religious respondents. On the other hand, by focusing on the issue of life, this hierarchical religious cosmology greatly relativizes the weight of violations of norms that are not directly related to the issues of existence-non-existence. It follows from our approach that religious people are less likely to take a strong view of violations of sexual norms that have no direct impact on life. Here, the stricter judgement of religious people about violations of norms is also preserved, but it cannot be compared to the values that appear either due to direct personal involvement (divorce) or—as a result of religious cosmology—in behaviours that restrict an individual’s personal freedom (e.g., in the assessment of euthanasia, abortion, suicide).

Religiosity in the Central and Eastern European region cannot be interpreted within the interpretive frameworks that link religiosity to traditionalism. Religious life in the region has features in which both the stricter value judgements of the Judeo-Christian tradition and the personality-focused religiosity, which is definitely the result of modern development, are present. This shapes a value system that does not follow strictly the beliefs of denominational religiosity anymore, but it interprets phenomena also within the framework of personal cosmology. This is reflected in a specific assessment that focuses on personal mental hygiene, which can best be seen in the context of the religious lifeworld. Thus, the novelty of our research was that we were able to empirically prove that the emergence of a specific religious value in modern secular society depends on the influence of social spaces. A religious cosmology and value system different from the non-religious can prevail in the social space of the lifeworld, where modern rationality is less able to extend its power.

7. Discussion

Our novel analysis is the first attempt to examine the impact of social spaces on the emergence of specific religious values over a longer time span and across a whole region. In our view, the research results provide convincing evidence of the impact of social spaces on attitudes towards norms. On the other hand, the results of our research, which focuses on the role of social spaces in a novel way, may open up further research questions and directions. Looking at the characteristics of the secularisation process, it can be assumed that the impact of social spaces on specific religious values can be observed in other regions. This suggests that social spaces in other regions of Europe offer different opportunities for the emergence of specific religious values. This may inspire further quantitative research to extend the scope of investigation to other regions.

In addition, our research has pointed out that it is the social space of the lifeworld that offers a wider range for the emergence of specific religious values. The personal world of everyday life is the social space that is further away from the reach of the secular public space and where the value system expressing the religious cosmology is expressed. Research in recent decades (

Heelas and Woodhead 2005) has shown that the main social space of the so-called spiritual revolution is also linked to the social space of the lifeworld. However, a more detailed mapping of the religiosity that emerges here requires, first and foremost, qualitative research that can draw more differentiated features of this particular religious value system by involving field research, in-depth interviews and focus group analyses. These analyses could also lead to the emergence of the characteristics of tactical religiosity mentioned in the theoretical introduction, now also involving insights from the sociology of space. This may also provide an answer to the question of how religious persons, as a counterpoint to secular dominance, develop everyday practices to preserve their own values. Our analysis of the impact of social spaces on the emergence of specific religious values will hopefully provide an impetus for further studies and contribute to a greater focus on the role of social spaces in sociological analyses of religion.