Abstract

Śrī Nāth is one of the most important images of Krishna being worshipped at the temple of Nathdwara in Rajasthan. His devotees consider him to be a living god, he appears in their dreams, and according to their sayings they are in direct contact with him. Śrī Nāth, originally a local deity, is equated with the major Hindu god Krishna. However, while Krishna may be one of the most important gods in India, he is also ambiguous through his acts and words, if not bluntly unreliable. This double nature of Krishna is reflected in the cult of Śrī Nāth. There is an interesting interaction between Śrī Nāth (implying Krishna himself), the main gurus of his cult, i.e., Vallabha (Vallabhācārya) and the latter’s son and main successor Viṭṭhalnāth and his devoted disciples. At times, Śrī Nāth feels the need to stick to the official Brahmanical cult of the temple rituals, on other occasions, there is no problem in transgressing any given official rule. The same is true for the primary teachers, who are often put on par with Krishna himself or one of the celestials closely connected to him. Additionally, the disciples can apparently do anything in their frenzies. All of this reinforces the idea that this entire cult belongs to another world (alaukik). It is part of the everyday world (laukik) of Hindu India, but meanwhile, each and every rule can be ignored if the supernatural breaks through. Even the distinction between Hinduism and Islam at times simply does not seem to be of importance anymore. Muslims can become addicted to the passionate love for Krishna through the form of Śrī Nāth, so it is sometimes stated. Each and every partaker in the cult may share the visions of the initiated devotee, at times even without proper initiation. This all adds to the experience of the supermundane and supernatural in this particular cult.

Keywords:

Krishna; Śrī Nāth; vārtā literature; Brajbhāṣā; hagiographies in Hinduism; Vaiṣṇava; Vallabha; Viṭṭhalnāth; puṣṭimārga 1. Introduction

My friend Sanjay Gupta sends a picture daily of the Hindu god Śrī Nāth, the god worshiped in the temple of Nathdwara, to all of his friends. For him, Śrī Nāth is the prime manifestation of the great Hindu god Krishna. His friends will respond to his message, as good as daily as well. For them too, the divine implies above all the image of Śrī Nāth. Sanjay lives in Udaipur in Rajasthan, in fact very close to Nathdwara, where Śrī Nāth is worshipped in an impressive temple site. For him and all of his friends, Śrī Nāth is not just an image in a temple. They live their lives with him. He is a living god. Śrī Nāth appears in Sanjay’s dreams, and he talks to him.

I once visited Nathdwara with Sanjay. We entered the temple grounds. Hundreds of devout pilgrims were there with us. It was in the afternoon, so the temple was still closed. Śrī Nāth lives there as if he were a king in his palace, and during the midday heat he takes a nap. Voices were raised, eyes were staring at the porch. Sanjay was excited, as was everybody, with sweat on his brow. Suddenly the doors opened. Everybody rushed inside, and in no time, we were surrounded by a pushing and tearing crowd that chaotically moved as one. I was crushed between the heated bodies of all those excited Hindus, sweat running over my body, my sweat or anybody else’s, it did not matter anymore. We were one flowing movement. We came in front of the image. We had a quick look. Then we went on, and went outside where we could relax. Sweat dropping.

This is not unique; it happens just about every day. It can even happen several times a day. It is part of the daily routine of Nathdwara, of ‘living Krishna’, who resides there. It is in fact common practice in many Hindu temples all over India. I knew this already, but I saw it once more reinforced that day. For his devotees, Śrī Nāth is not a stone image. He is alive. He is the playful god Krishna himself, taking this shape for the benefit of his devotees, for their enjoyments. Once in front of the image, everything changes to another level, or so it seems.

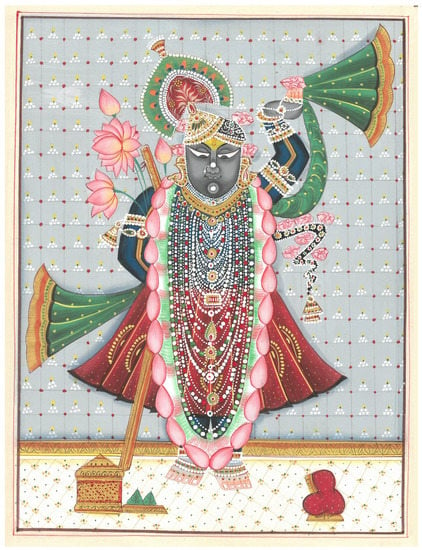

In this contribution, I want to pay attention to the complicated relations between Śrī Nāth (Figure 1), as a form of Krishna, his devotees, and the acts of gurus in the cult of Vaiṣṇavism. Śrī Nāth is considered by most of his devotees to be equal to Krishna, one of the most playful gods of the Hindu pantheon. However, Krishna is a paradoxical god. On the one hand, he teaches humanity the Hindu dharma, for instance in the form of the highly authoritative Bhagavadgītā. On the other hand, he creates the world for his own amusement. The god becomes bored and desires to play. He wants to enjoy his own beauty reflected in the universe and its beings. While he is so keen on the importance of dharma for humans, if there is one god who transgresses the selfsame rules with ease, it is Krishna himself. This turns him into a paradoxical figure; a figure that is loved and hated, at times by the same historical or mythological figures. Meanwhile, his behavior remains incomprehensible, at least from a ‘human’ viewpoint. Krishna always seems to ‘be beyond’.

Figure 1.

Śrī Nāth, modern painting from Nathdwara (private collection).

However, it is not only Krishna who acts thus. His mystical devotees can get to a similar level of awkwardness as the god himself in their frenzies. At times, the leading gurus of these devotees even feel the need to explain their follower’s strange behavior to other Hindus. However, transgression of the fixed rules almost seems to be a basic ingredient for fervent participation in Krishna’s games, his līlā. This does not detract from Śrī Nāth’s position, nor do they see him as an ‘uncivilized, irresponsible’1 god. On the contrary, for his devotees, this only reinforces his uniqueness, his ‘otherworldliness’.

In this article, we will mainly concentrate on the interactions between the playful god, his teachers, and the devotees, as we find reflected in hagiographical accounts. The main source in this contribution consists of saints’ stories from two important medieval collections of mystics’ stories, the Caurāsī vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā and, above all, the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā.

This article consists of two parts. First there will be an inventory of what vārtā literature encompasses; then an exploration of the positions of the two collections mentioned within the works of the puṣṭṭimārga, the main Hindu denomination (saṃpradāya) connected to the cult of Śrī Nāth. The present image of Śrī Nāth was, according to the puṣṭimārga, discovered by farmers, but the cult was brought to its greatest peak by teachers such as Vallabhācārya (1479–1531) and his son and main successor Viṭṭhalnāth (1516–1576). Time and again, devotees search for parallels between the lives of these saints and Krishna himself. Interaction with other competing groups also plays a part here.

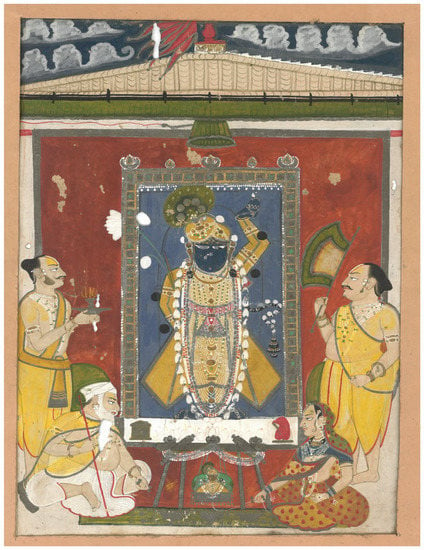

The setting in which this all takes place is the Braj area, a sacred area roughly surrounding the sacred city of Mathura in Northern India. The devotees of Śrī Nāth always try to connect their daily life to that of Śrī Nāth. Śrī Nāth lives through a set of daily, fixed rituals (Figure 2). His devotees visit the temple in Nathdwara and persistently try to be aware of what the playful god is doing each moment of the day. The devotees live in likeness to the eternal timeless līlā. They will even do so if they are far removed from the Braj area or Nathdwara in Rajasthan, where the image is presently under worship. The devotees try to identify with his games and there is a deep awareness of a mutual interpenetration; a mutual interaction between the devotee’s daily life and the timeless life of Śrī Nāth.

Figure 2.

The image of Śrī Nāth under worship. In front of the image, there is a small cradle or swing with an image of young Krishna. Worshippers pull the string to rock young Krishna. The priest on the left offers an āratī light. Rajasthan late 18th century (private collection).

The main question here concerns the unpredictability of this young god. He always seems to elude each and every rule at will. It is his own choice if he obeys whatever instruction or ordinance, or so it seems. However, it is paradoxical that on the one hand he may escape from the ritual institutions, while on the other hand he may suddenly decide to obey them. The first part of this article will, thus, concentrate on this strange character and the strange acts which comprise Vaiṣṇavism. They reinforce that Krishna, his gurus, and devotees do not belong to only this world—they are certainly not restricted to this world. They have access to another world as well, the world of the unpredictable living stories of the young, playful god who is beyond time and space. Within Vaiṣṇavism, we often find a distinction made between the common everyday world and the world beyond: Krishna’s world. The everyday world is named laukik, ‘worldly’. Krishna’s world is beyond time and space, and therefore, it is not of this world. It is named alaukik. This alaukik world, at times, shines through the laukik everyday However, what is quite remarkable is that when this happens, it seems as though it happens for the first time. All those present, even the head gurus who should be aware of these events, are overwhelmed by an experience which one would think happens quite often; at least, it happens often in stories. That is remarkable, although friends of mine in Rajasthan, such as Sanjay, with whose quotation I began this article, will tell similar stories. According to devotees, it seems to happen all of the time.

The second part of this article consists of examples from saints’ hagiographies; saints’ stories in which these unpredictable aspects of the interplay between Krishna, his gurus, and devotees are illustrated. At times, the devotee needs an explanation from their guru for Krishna’s behavior. On other occasions, the devotee needs to explain to the guru what Krishna wants. As Vallabha and Viṭṭhalnāth even accepted Muslims as their disciples, Hindus from other denominations at times ask for explanations for this. That the devotees act so strangely is accepted to a certain extent. Very often, they belong to lower castes than the head gurus. However, Vallabha and Viṭṭhalnāth are high caste Brahmins. They embody the Vedic lore. Vallabha is even equated to the god Agni, the purifier of the world who directly communicates with the gods (Barz 1976, p. 28). They then question how they can accept the strange and often impure acts of their disciples. Explanations are naturally needed at times. However, the persistent capriciousness of Krishna oozes through in the frenzies of the devotees, in the passion of the teachers, and the sometimes childish actions of Śrī Nāth.

Interesting to note is that strange acts of a Hindu god that require explanation are not unique to Krishna. I will just mention a few examples here. Similar acts are done by Jagannāth, the main deity of the temple city of Puri in East India. South India is full of stories of the strange actions of gods, such as Śiva and Viṣṇu. Their devotees are frequently astonished, and so are their gurus. There is a local collection of the deeds of Śiva, for instance, in Madurai in Tamil Nadu, the Tiruviḷaiyāṭal Purāṇam.2 Hagiographical accounts of devotees of Śiva can be found in Tamil texts, such as the Periyapurāṇam.

The three main actions from the hagiographies on which we will concentrate in the second part are: (1) the miracles surrounding Śrī Nāth, his teachers, and disciples, (2) the transgression of the temple rules and subsequent unexpected obedience to the rules by Śrī Nāth, his devotees, and the teachers; and (3) the complicated acceptance of followers of other creeds. In many cases, this implies the acceptance of Muslims. On the one hand, they may be deeply devoted to Krishna, while on the other hand, they embody impurity.

2. Vārtā Literature, the Caurāsī Vaiṣṇavana kī Vārtā, and the Do sau Bāvana Vaiṣṇavana kī Vārtā

In this contribution, we will mainly focus on the so-called vārtā literature.3 Vārtās are a particular class of texts within the Vallabhasaṃpradāya or puṣṭimārga, the Vaiṣṇava denomination founded by the main gurus of the Vallabhasaṃpradāya, Vallabhācārya and his son and main successor Viṭṭhalnāth. The word ‘vārtā’ means ‘account’. Within the Vallabhasaṃpradāya, several of these texts are held in high esteem, e.g., the Nija vārtā, the Gharū vārtā, the Bhāvasindhu, the Śrī Nāth Jī prākaṭya kī vārtā, and the Śrī Mahāprabhu prākaṭya kī vārtā (Vaudeville 1980, p. 16). These texts are attributed to a very prolific and, as tradition has it, long lived writer: Śrī Harirāy Jī (1590–1715 CE).

Two other vārtās are the Caurāsī vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā and the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā. The first one, the ‘Account of the 84 Vaiṣṇavas’ deals with the 84 main disciples of Vallabhācārya himself. The second collection, the ‘Account of the 252 Vaiṣṇavas’ deals with the 252 main disciples of Viṭṭṭhalnāth, the second son and main successor of Vallabhācārya. Both these collections are attributed to either Gokulnāth (1551–1640 or 1647), one of the sons of Viṭṭhalnāth or to his nephew, the same Śrī Harirāy just mentioned. In that case, maybe Harirāy based his account on stories Gokulnāth told him. Harirāy is said to have lived from 1590 to 1715, and thus, reached an unprecedented age, certainly for that period. This supposed long life adds to his legendary status. McGregor (1984, p. 209) assumes that this Harirāy was active in the 17th century. Harirāy has also written two commentaries on the two collections of saints’ lives; these commentaries are named Bhāvaprakāśa. In these commentaries, he links the incidents of the saints’ lives with the specific theological doctrines of Vallabha.

The Caurāsī vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā and the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā4 are very popular even today in the Braj area. It is important to notice that there are various printed editions of the works. These often show many variations in readings and episodes. The texts are composed in prose and its language is Brajbhāṣā. The Brajbhāṣā of both collections is quite simple; no complicated grammatical constructions nor strict poetical conventions. The accounts reflect popular story telling as if one were listening to a traveling artist who tells these accounts every evening in another dusty village in northern India. In some of the vārtās, one may come across Sanskrit verses. These are also quite simple, and from the perspective of classical Sanskrit, one might notice grammatical mistakes or variations.

It is important to note that very often if a devotee of the Vallabhasaṃpradāya tells you a saint’s history, they will often claim that it is part of one of the vārtās. In many cases, however, such an episode cannot be found in an edited volume. The word ‘vārtā’ in such a case simply seems to imply a traditional account of a mystical saint or poet-saint. In this contribution, we will mainly focus on the accounts of the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā, the stories on the disciples Vitṭhalnāth.

A vārtā usually consists of various prasaṅgas, or episodes. Very often, they start with the words: ‘Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī kā sevak [name of the disciple] tinakī vartā’: ‘The servant of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī, [name] his/her account’. Śrī Gusāīṃ (Brajbhāṣā for Sanskrit: Śrī Gosvāmī) is the usual title of Viṭṭhalnāth in the stories. After this, in the first prasaṅga, the background of the impending saint is given. He or she lived a common life, sometimes even as a criminal (the great saint Chītsvāmī even lived as a thug who killed people for the goddess Kālī). Their caste may be mentioned, or the village where the saint lived or originated from, and so on. These accounts share an initial exposure to Krishna, one of his exemplary devotees, or a confrontation with Viṭṭhalnāth himself.

The first view of Viṭṭhalnāth is often described in deeply sensual, erotic terms. As a teacher, he must have had quite some impact on his disciples. It seems as if his bodily presence was overwhelming and charismatic. This last theme is found in nearly all of the vārtā accounts. Viṭṭhalnāth is as attractive as is Śrī Nāth himself. He looks like Kāmadeva or Kandarpa, the god of love. However, more often, it is stated that he embodies the charm of ‘ten million Kandarpas’.

The following, for instance, from the account of Nanddās (though these words can be found in many vārtās): ‘Then Nanddās Jī came and had the darśana of Śrī Gusāīm Jī (i.e., Viṭṭhalnāth); it was the darśana of the complete highest person with the charm of ten million Kandarpas (koṭi-kandarpa-lāvaṇya-pūrṇa-puruṣottama) in his selfsame shape’.

Śrī Nāth and Viṭṭhalnāth, thus, share the same sensuality. The images of Krishna himself and his main guru coincide. Sensuality in whatever form deeply pervades Krishnaism more generally. Within these life histories, however, they concentrate on the relation of the devotee to Krishna himself, and the relation to the initiating or confronting teacher. Each and every relationship is characterized by this kind of mutual longing.

The ritual of darśana plays an enormous role. The very act of ‘seeing’, and thus, taking part in Krishna’s games is extremely important. Sensory, even passionate experiences exhibit the utmost communion, not the repression of the senses.

After this confrontation, an initiation into the puṣṭimārga will follow, in which the overall forces of devotion and bhakti are shown. The so devoted and beloved saints, Śrī Nāth and Viṭṭhalnāth, each play their part here. They do so by performing miracles, by extreme acts of devotion, by transgression of ritual restrictions and rules, or, in other cases, by strictly adhering to these rules. Each prasaṅga ends in a number. Sometimes, songs or poems are inserted into the text. These poems are then very often connected to that particular incident in that vārtā and appreciated with reference to it. At the end of a vārtā, we often find sentences such as: ‘He/she was such a vessel of grace of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī, how much further can his fortune possibly grow? The vārtā is completed’.

There are many variations in these final sentences, however. Sometimes, the saint simply enters the eternal games of Krishna (līlā). This implies that they disappear from this world. This would be the alaukik interpretation of the event; they die, one would say from a mundane (laukik) viewpoint.

Viṭṭhalnāth was not the eldest son of Vallabha, but he was his most important successor. Viṭṭhalnāth succeeded Gopīnāth, Vallabha’s eldest son. Within the Vallabhasampradāya, Gopīnāth was considered to be an incarnation of Balarāma or Baladeva, Krishna’s elder brother. Gopīnath was, thus, his wordly (laukik) form, and Balarāma his ‘other-worldly’ form (alaukik). However, Gopīnāth became an ascetic after the ‘disappearance’ of his son Puruṣottamadās, who, according to tradition, was incorporated into the eternal līlā by Krishna himself. Puruṣottamadās disappeared in one of the caves of the sacred hill of Govardhannāth. Gopīnāth then withdrew from the Braj area and went to Jagannāth Puri in Odisha. The story has it that there, he mysteriously merged into the image of Balarāma. Thus, he returned to his place of origin and Viṭṭhalnāth took over his position. The fact that Gopīnāth disappeared in the image of Balarāma has important implications for the position of Viṭṭhalnāth. It shows that Gopīnāth is in fact another form of Balarāma, Krishna’s elder brother. Viṭṭalnāth can, thus, be considered a full incarnation of Krishna, because now, Balarāma was in fact Viṭṭhalnāth’s eldest brother in the form of Gopīnāth. This parallels the relationship of Krishna himself, with Balarāma as his elder brother (Entwistle 1987, p. 151).

Viṭṭhalnāth is named after Viṭṭhala, a form of Viṣṇu under worship in the temple of Pandharpur in Maharashtra. Tradition has it that this form of Viṣṇu advised Vallabha to get married as he wanted to be incarnated as a son of Vallabha. Thus, Viṭṭhalnāth was born (Barz 1976, pp. 29, 38). In the eyes of the disciples of Viṭṭhalnāth, he was as good as equal to Krishna, if not one and the same. There are many songs of praise in which Viṭṭhalnāth’s powers, virtues, charisma, and beauty are put on a par with those of Krishna. The poet-saint Nanddās5 sings about him in his songs in Padāvalī no. 6 and 7 in following words:

Let me praise the feet of Śrī Vallabha’s sonHe is so tender, singing of him gives good fortune, I praise him because he purifies the downfallen ones. I praise him because he expounds the firm rules of the Veda and removes the evil of the kali time. His glory is incomparable. I praise him as the beauty of the earth, he has removed evil, suffering and crimes. O praise him, he has expounded the puṣṭimaryādā (puṣṭimrajāda), he is the utmost of the fortune of singing, he completes the upkeeping of his own family. The Lord of Nanddās is manifest in two forms, Śrī Viṭṭhala and Giridhara, I praise both.(pada 6)

Hail! Lord of Rukmanī and Padmāvatī6, dear as life-breath, umbrella for the groups of Brahmins, you who cause bliss (ānanda)! Torch for the family of Vallabha, savior of the world! You shine like ten million moons! Lord, who gives devotion (bhakti) to those who seek liberation, capable of anything, full of countless virtues! May the Lord of the devotees conquer! Who purifies the fallen! Who fulfills the wishes of those who crave, all pilgrimages come to their fulfillment by just remembering your name! A life eternal with him who gratifies Gokul (i.e., Krishna). For Nanda and the servants the Lord is the father of Giridhara and the others [i.e., Viṭṭhalnāth]. He is the visible incarnation (avatāra) of the bearer of Girirāja (Krishna).(pada 7)

In pada 7, Viṭṭhalnāth’s sons are mentioned as ‘Giridhara and the others’. They were seen as partial (aṃśa) incarnations of Krishna (Barz 1976, pp. 54, 55). In pada 6, the word ‘Giridhara’ refers to Krishna himself or to Giridhara as Viṭṭhalnāth’s son. The sons were all named after Krishna or Rāma. The main gurus of the Vallabhasaṃpradāya in the line of Vallabha, Gopīnāth and Viṭṭhalnāth, are even presently considered to be aṃśa incarnations of Krishna.

2.1. Discovery of Śrī Nāth and Braj as a Sacred Area

Śrī Nāth is considered by his believers to be a living being with a personality of his own. Nowadays Śrī Nāth is in Nathdwara, which is a typical Hindu pilgrimage site located in a small village with some 50,000 inhabitants. Pilgrims come and go in great masses, especially on festive days. Very often, they combine their pilgrimage with a visit to the Śiva temple of Ekaliṅg Jī and the Jain temples of Ranakpur.

In fact, Śrī Nāth originates from the Braj area.7 The entire Braj area is nowadays connected predominantly to Vaiṣṇavism and Krishna. This was different in the past. Research proves that up to around the 16th/17th century C.E., Braj was more oriented towards Śiva and Pārvatī (Vaudeville 1976, 1980; Entwistle 1987). In the 16th/17th century, new Vaiṣṇava movements arose and prominent teachers came to the Braj area. Braj was ‘rediscovered’, so to say, as a Vaiṣṇava area (Vaudeville 1976). Ever since, it has become a prominent pilgrimage site, but mainly for devotees from other areas of India. The original Brajvāsīs still prefer Śiva and his consort. There is even one place where Śiva is stated to have dressed up as a cowherd girl, a gopī, in order to witness Krishna’s nightly dance (Entwistle 1987, pp. 58, 59; Padmalocandas n.d., pp. 53, 54).8 This can be interpreted as an initiative of the newly arrived Vaiṣṇavas to integrate the original Śaiva worship within Vaiṣṇavism. It can be seen as an attempt of appropriation. Many local Śaiva names of areas were also adjusted to better suit Vaiṣṇavism.

It is stated in the Braj region that Vajranābha, one of the great-grandsons of Krishna himself, indicated all the places where Krishna had walked, lived, and resided in the region. In accordance with his instructions, palaces and temples were constructed. Due to the sinful religions of Buddhism, Jainism, and Islam, these sacred sites had disappeared. They were absorbed by the goddess earth herself. When it comes to the embodiment of Krishna himself, there are descriptions, so tradition states. The last human who could remember exactly what he looked like was princess Uttarā. She was married to Abhimanyu, one of the sons of Arjuna and Krishna’s sister Subhadrā. As Uttarā was the last to have seen him alive, her descriptions were crucial in forming images of Krishna. She gave much advise concerning the bodily features of these images. Tradition will even say it was according to her instructions that the image of Śrī Nāth was made. However, these images had also disappeared due to the harmful religions mentioned above, vanquished into the earth. It was only when righteous devotees returned to the Braj region that the sacred sites once more revealed themselves.

The Braj text Śrī nāth jī prākaṭya kī vārtā describes how Śrī Nāth made himself manifest in stages, and how his image was discovered inside a hill. Charlotte Vaudeville has analyzed the text and the imagery of it at length in her studies (Vaudeville 1976, 1980). The image was discovered when a cow leaked out all of her milk every day on a particular spot. Later, a hand and a mouth were discovered, and in stages, the entire image of Śrī Nāth became manifest. Similar stories at times play elsewhere in India on the discovery of liṅgas of the god Śiva, for instance. Very important here is that it is the image of Śrī Nāth itself that makes the choice to become manifest, as by now, these virtuous Vaiṣṇavas were born and were about to visit Braj.

Vaudeville (1980, p. 20) mentions how the moment Śrī Nāth’s mouth became manifest, Vallabha was born. This simultaneity is not coincidental. Vallabha, as a pure high caste Brahmin, embodied the mouth of Viṣṇu or Krishna, he embodied the Veda, and even the god Agni, as stated above. As a high caste Brahmin, he embodied the power of the manifested divine sounds of the śruti. Therefore, his words are supposed to be true. Vallabha later came to the Braj region and the sacred sites simply popped up from their hiding. In some accounts, it is the river Yamunā itself who manifested as a goddess and took Vallabha around.

Meanwhile, other Vaiṣṇava communities also claimed the discovery of Braj and the images of Krishna. The great ecstatic mystic Caitanya (1486–1533) departed from Bengal, came to Braj, and discovered the sacred site Rādhākuṇḍ. Within the tradition, it is better to say Rādhākuṇḍ manifested itself when the pure devotee Caitanya appeared there. At a certain moment Vallabha went on a parikramā, a tour around the universe. The daily worship of Śrī Nāth was then handed over to Caitanyaite Brahmins from Bengal (Vaudeville 1980, p. 39). However, they applied sandal paste on Śrī Nāth’s body, which he did not like. Moreover, the Caitanyaites would at times put an image of Bṛndādevī, a manifestation of the local goddess, next to the image of Śrī Nāth. Within the Vallabhasampradāya, Krishna is very young; he is of an age at which ‘girls are [frequently] stupid’. Therefore, Śrī Nāth was not too fond of playing with girls. That would only change later on. Within the Gauḍīyasampradāya of Caitanya, Krishna is a little older and his love games with his beloved gopīs are central. However, young Krishna was not fond of the rituals of the Caitanyaites.

Vallabha passed away in Varanasi. As mentioned, his son Gopīnāth succeeded him, but he disappeared in Puri. Viṭṭhalnāth succeeded Gopīnāth and had the Caitanyaite Brahmins removed from the temple service. The main priest of the Caitanyaites, Mādhavendra Purī, was sent to South India to get a very special type of sandal paste from there. However, it was Śrī Nāth’s intention that he would never come back. It was indeed for this very reason that Śrī Nāth had demanded that particular type of rare sandal paste. Thus, the devotional duties came back to the hands of the Vallabhites, and the Caitanyaites were out of the picture.

Within the Vallabhasampradāya, several images of Krishna are worshipped. The main ones are Śrī Nāth, Śrī Navanītapriya, Śri Mathureśa, Śrī Viṭṭhalanāth, Śrī Dvārakānāth, Śrī Gokulnāth, Śrī Gokulcandra, Śrī Bālakŗṣṇa, and Śrī Mukundarāya (Barz 1976, p. 55). They are called mūrtis or svarūpas; ‘ímages’ or ‘embodiments’. For the nine mentioned here, the term svarūpa is preferred within the Vallabhasampradāya. A distinction is made between mūrtis and svarūpas, the svarūpas being considered as superior embodiments of the god, and thus, within the Vallabhasampradāya, the term mūrti is avoided (Barz 1976, p. 9). Each of the embodiments have their own particularities and characteristics. The most important one is Śrī Nāth; however, the image of Nathdwara (Figure 3). It is in black stone and measures 1.40 m. The image shows the god standing with his left hand directed upwards. This perhaps refers to the episode where he lifts Govardhan hill to protect the area against the rains of the god Indra. His right hand touches his hip. He has peacock feathers on his head, which are often considered to be a connection to his life as a cowherd boy in the forests of the Braj area, which are full of peacocks. Furthermore, he has three lotuses on his right side. On his left side, he has a type of shawl that curves as if it were a snake.9

Figure 3.

The image of Śrī Nāth is installed. Rajasthan 18th century (private collection).

Śrī Nāth is shown in a mountain cave. The mountain itself has depictions of two cows, two peacocks, one snake, one parrot, and sometimes a lion. In the temple itself, the image is elaborately decorated. The cult of Śrī Nāth is so popular that his outfit is changed several times a day. He is never given the same garment or jewel to wear, at least so it is stated locally. Behind his image, there are large depictions of Krishna’s games in the pasture fields of Braj. Festivals are sometimes depicted as well. These colorful paintings, usually on cotton cloth, are named picchvai which are sold after the ritual darśanas. Therefore, there are thousands of these, and they are often found in the houses of richer Vaiṣṇavas and in museum collections. Sometimes, they are elaborately painted with gold-infused paint.

Another connection between Krishna and Śrī Nāth consists of the following. Krishna was born, according to the myth, in the prison of his uncle, the evil king Kaṃsa of the demonic city of Mathura. Kaṃsa wanted to kill the newborn baby Krishna, since it had been predicted that the child would eventually kill him. Miraculously, Krishna was saved by his father Vasudeva, who transported him to the cowherd settlement of Gokul. Later on, Krishna and his family had to flee because Kaṃsa had heard that Krishna was still alive. He, therefore, wanted to kill all boys in Gokul up to approximately three years of age. Krishna was then brought to Brindavan where he grew up. Once the image of Śrī Nāth was discovered, it was worshipped in the Braj area, but later on, just like in the case of Krishna, the image had to be transported elsewhere because the Moghul emperor Aurangzeb (1556–1605) wanted to destroy it. The image was carried away in a bullock cart, and after various events, it ended up in Nathdwara, where it is under worship now. It was the will of the image itself to remain in Nathdwara, so tradition has it. Once more, a parallel between Krishna and Śrī Nāth.

The god himself is truly worshipped as if he were a living person, which Śrī Nāth definitely is for his devotees. He lives in his temple as a king in his royal court. The temple is named a haveli, or mansion. It has various chambers and rooms as if it were a palace where a royal or noble ruler lives.

In the temple, there is a strict order for the day. There are particular moments during which the devotees throng together to have the visionary experience of their god, to see the living deity. These moments are the so-called darśanas, and for each of these, his outfit is changed. Having a darśana is one of the most profound rituals of Hinduism more generally (Eck 1985). Devout Hindus enter their temple to be in the living presence of the god. They see the living god, and the living god sees them. Vaiṣṇava tradition purports that when Krishna was still very young and crawled in the courtyard of the house of Nanda and Yaśodā, the girls and women of the village would come to play with him, not giving him a moment’s rest. Yaśodā noticed how her little son got extremely tired and did not even have the opportunity to eat properly, constantly caressed as he was by these women. She decided that her son should be given moments to sleep, moments to eat, and to be by himself for some time. Therefore, the ritual darśanas were instituted, so tradition has it. These are the moments that the playful god belongs to the world. The other moments are his.

2.2. Śrī Nāth and the Daily Life of the Devotees

The devotees are well aware that their god passes through a perfectly arranged and ordered cycle of daily rituals. These are usually performed by skilled professionals, in most cases Brahmins. These ritualists (bhītariyā) are trained in these ritual services, they originate from proper family lines and from specific Brahmin castes. When they serve in the shrines, they are in a condition of utmost ritual purity. The devotees can see their god at various times each day in the shrine, while he is in fact performing his manifold games. He is pure because his Brahmins, their rituals, and their ritual implements are pure. Seeing the god thus, ’having his darśana’ on various moments of the day, is one of the main rituals of Vaiṣṇavism. The confrontation with the specific acts of the deity at these moments once more reinforces the devotee as a participant of the games of Śrī Nāth. Throughout the year, the daily rituals may naturally differ in detail. They can be different on festive occasions, for instance10, but in Nathdwara, Śrī Nāth passes through the following ritual cycle essentially every day:

At around five o’clock in the morning, the maṅgaladarśana takes place. Krishna is awakened by blowing a conch shell. He is given breakfast; in summer, he wears light clothing, in winter, his clothing is somewhat warmer. Songs are sung of Paramānanddās11 and the vīṇā is played.

The next darśana, the śṛṅgāradarśana, is at six in the morning during summer and at seven-thirty in winter. Krishna wears rich clothes and ornaments in accordance with the seasons. Songs of Nanddās are sung, the tanpura, the sarangi, and the mridanga drum are played.

The gvāladarśana takes place at around one hour after the previous darśana. This is the moment Krishna goes out to herd the cows in the forest and the pasture fields. A light-offering, āratī, is performed and incense is offered. Govindsvāmī’s compositions are sung, accompanied by shennai and nakkara drums.

The rājbhogadarśana is held at midday. It is the most elaborate of all. Krishna is clothed in his most beautiful outfit and he gets several top-quality dishes to eat. Songs of Kumbhandās are sung and music is played on various instruments. After this ceremony, Krishna rests.

At two o’clock in the afternoon, Krishna is awakened with conch shells during the utthāpan ceremony. Songs of Sūrdās are sung.

At around three in the afternoon, the bhogadarśana takes place. Krishna gets his afternoon meal. Songs of Caturbhujdās are sung and Krishna gets cooling water in the summer, or a warm stove for his feet in winter.

The sandhyā āratī is held at five o’clock in the afternoon. In the eyes of the devotees, Krishna now returns home from the pasture fields. Lamps are waved in front of the image and Krishna receives a light meal. Compositions of Chitsvāmi are sung.

The śayanadarśana is the moment Krishna goes to sleep. A tray with small snacks and a vessel of water from the Yamunā are left at the side of his bed, and songs of Krishnadās are sung. The temple remains empty until the next morning.12

For the devotees performing the ritual service, (sevā) Śrī Nāth is a living being to such an extent that he is considered to attend the śṛṅgāradarśana; just before the devotees get the chance to share in his darśana, they may even offer a mirror for him to inspect his own beauty now that he is dressed in his most exquisite outfit. The mirror is considered to be a manifestation of Rādhā, as he can, thus, experience his own beauty reflected in Rādhā. That he is given a stove for his feet in wintertime makes him even more ‘human’. Some devotees state that in the warm months of the year, Śrī Nāth rushes back to Braj after the śayanadarśana to play with his friends and the cowherd girls in the forest of Brindavan. In the colder months, he remains in Nathdwara, because the trip to Braj is too hard in that season.

Within the saṃpradāya, special songs have been composed to remind the devotees concurrent to each moment of the day what the young god is doing. As an example of this, I want to present the aṣṭayāma13 song of the renowned poet Raskhān (also: Rasakhāna 16th/17th century CE.):

- Aṣṭayāma

- In the morning Gopāla Jū gets up, he bathes in the river and arranges his hair. I constantly look at that treasure of rasa (rasakhāna).

- There, Śrī Nandalāla performs his pūjā and worship while he sits. On the flute, a sweet tune resounds14, hearing it everyone is joyful.

- As soon as you see the crown with the mirror and the beautiful crest jewel, the beautiful garland, there is beauty. Hail! Hail! Gopāla!15

- Then, a group of bhaktas arrives there, each of them bringing his own plate. The Lord eats from them, it hardly takes any time.

- Thus, two pahars (i.e., two periods of three hours) pass. Then there is the border of the forest. He takes the cows and goes to the forest, while he plays music on his flute.

- Then, all the bhaktas go as well, they all run from behind. They play and go there where the fluteplayer makes them joyful.

- When they arrive in the forest, where there is always the abode of Madana,16 the skilled dancer performs there all types of rāsa dances.

- One pahar he roams in the forest, Śrī Madana Gopāla. He makes a trip in his own dhāma17. Altogether they are a great group.

- Then, when the excellent dancer returns and takes his food, they take their prasāda with devotion (bhakti) and all sit down after washing their hands.

- Then, the flute of Gopāla resounds there, a treasure of rasa (rasakhāna18); hearing this, all forget their memories; mind and life-breaths are joyful.

- The Lord next gives a good sermon and he makes all glad, all minds are delighted when they hear it, they are made tender and full of enjoyment.

- The Lord always gives a sermon of three gharīs (ghaŗī i.e., 3 × 24 min) to the bhaktas. Lust, anger, pride, and greed do not arise then anymore.

- Then, when he sees that it is time to milk the cows, the clever boy, dark as a raincloud, calls all his friends by their beautiful names.

- Then, he looks with his curved eyes there as he always does. All the milk, excellent because of its taste, the glorious and divine Śyāma (i.e., the ‘Dark one’) milks.

- Then, all the sakhīs (girlfriends), always with love, take the milk, by signs they delight the excellent dancer because of the love in their minds.

- Then, as soon as the lamps burn, all the bhaktas run gladdening, each taking their own light, expressing their love.

- Rādhā19 and Krishna are seated there with the other eight queens. The clever one (sujāna) sings a song while an offering of light (āratī) with incense goes up.

- Thus, there are two there: enjoyment and passion (rasa and raṅga). Thus, a pahar passes by. When they have got permission then, the bhaktas go to their own houses.

- Then, all the bhaktas go to their own houses, holding in their heart the beauty of the couple at night. They have a pleasant sleep.

- Śyāma always sleeps a few pahars, then he wakes up. When a melody of the flute resounds then, the bhaktas get up, taking his name [in their mouth].20

- Since Rasakhāna has seen the beauty of Mohana, the eyes are not his own anymore. If he pulls (his eyelids) they come like from a bow, released they go like arrows.21

- This son of Nanda! This thief of my mind! He stole the jewel of my mind. Now he settled in my mind. What can I do now without my mind? I fell into the noose of love.

- The beloved took my mind, when he looked, but gave nothing in return!22Where did you learn this manner! That you keep your riches with you?

- Oh Friend! I have seen the beautiful boy near the house of Nanda. He stared sweetly smiling.Each and every memory of my body is stolen.

- I have seen the incomparable beauty of the enticing beautiful Śyāma. He is the son of the headman of Braj. He settled in my mind, soul… eyes…

- Friend! The skilled beloved has become a stranger, while I know him. He has given up knowing me, although he knows me as his beloved.

Several accounts of the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā show how devotees keep this daily order of rituals in their mind even when they are far removed from the image of Śrī Nāth. This is found for instance in the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā account of Mādhovdās Kṣatrī (no. 19), also named Mādhavadās Kṣatrī. He was a disciple of Viṭṭhalnāth, but he lived in Kabul in Afghanistan. Another Vaiṣṇava named Rūpamurārī goes on a tour with a king and comes to Kabul, where they recognize each other. Śrī Nāth himself even responds to Mādhavadās’ devotion by appearing in Kabul, which is far removed from Braj. Śrī Nāth even protects them later on against robbers. Śrī Nāth makes them miraculously reach the company of the king who traveled many days ahead of Rūpamurārī. This is just another miracle of Krishna, of which there are so many in the vārtās.

The servant of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī Mādhovdās Kṣatrī, his account. That Mādhavadās lived in Kabul. One day Bhaiyārūpamurārī [another Vaiṣṇava, also named: Rūpamurārī] came to Kabul together with the king. When he saw a tilaka on the forehead of Mādhavadās on the market there, he asked: ‘Who are you and why do you have that tilaka?’. Then, Mādhavadās said: ‘We are servants of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī.’ When Rūpamurārī then said: ‘We are also servants of Śrī Gusāīṃ jī’, Mādhavadās was very joyful. In the meantime, Mādhavadās got up and started to spread his shawl. Then, Rūpamurārī asked him: ‘What is this?’ Then he said: ‘Śrī Nath Jī now enters Braj in order to let the cows graze, therefore I spread out my shawl’. Hearing this, Rūpamurārī was very astonished. There was such an amazement that Śrī Nāth Jī here gave him a darśana [this means so far from the Braj area]. In his mind, he praised him a lot. And whatever Mādhavadās said about the outfit of Śrī Nāth, his brother Rūpamurārī wrote that down. Then, after they had gone to the house of Mādhavadās, they had the darśana of Śrī Ṭhākur Jī (i.e., Krishna or Śrī Nāth). It was truly the darśana of Śrī Govardhannāth Jī [another form of Krishna]. Then, he said in his mind: ‘It is my good fortune that Śrī Gusaīm Jī even in this land of foreigners (mlecchadeśa) still gives me the company of Vaiṣṇavas’. When after thus staying a few days, they prepared for leaving, then Mādhavadās said: ‘You should stay a few more days. When the king will go twenty more stages, I will make you reach there in one day’. Then, Rūpamurārī stayed. Twenty days later, Mādhavadas sat on a horse together with Rūpamurārīdās, and following some other road of eighty kośas through the mountains, they reached there in one night. On the road, there were many thieves, but nobody saw Mādhavadās and Rūpamurārī. And the entire night on the road, they were talking on the deeds of the Lord. When Mādhavadas said: ‘I have become the servant of Śrī Gusāīm Jī in Haridvar’, then Rūpamurārī was greatly astonished that Śrī Nāth Jī gave him there [i.e., in Haridvar, so far from Braj] the darśana together with the līlā of Braj. Śrī Gusaīm Jī has a great deal of compassion over them. Then, Mādhavadās said goodbye to Rūpamurārī and he went to his own house. Such a vessel of grace is Mādhavadās that Śrī Nāth Jī gives him ever again the darśana in Kabul. The essence is that the Lord is only subject to the emotion bhāva), and not subject to the method. Nanddās has said this:dohā:Although he, whom they call the Veda (nigama), is not accessible through the āgamas,He is subject to passionate love, Hari is extremely close then,They call him the Veda (nigama).The vārtā is completed. Vaiṣṇava 19.

3. The Wondrous Interactions between Śrī Nāth, Viṭṭhalnāth, and the Disciples

In the second part of this article, we will concentrate on particular episodes from a number of vārtās from the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇavana kī vartā. The main focus will be the mysterious interaction between Śrī Nāth, the primary guru of that period, Viṭṭhalnāth, and the devoted disciples. The interaction will concentrate on these aspects: (1) the miracles that surround Śrī Nāth, his gurus, and devotees, (2) the transgression of rules or the attempts to stick to these rules, and finally, (3) the attitude towards those considered ‘others’, especially towards Muslims who desire to take part in the service of Śrī Nāth. In many of these hagiographies, it becomes clear that worldly existence (laukik) and Krishna’s eternal timeless world (alaukik) interact. In this context, ordinary phenomena are not what they seem to be at first view. In the alaukik world, devotees are different from the humans they might look like. Some mystics are even identified with figures from the alaukik world, including associations with a name and family. Above, we have already seen how Vallabha was put on par, if not equated to, Viṣṇu’s mouth and the god Agni. However, he is also sometimes identified with Svāminī, a title of Rādhā. Rādhā is Krishna’s most important consort; though in the Vallabhasaṃpradāya, emphasis is laid on Krishna as a small child, Rādhā is still present. Viṭṭhalnāth is identified with Kāmadeva and also with Krishna himself, but additionally with another cowherd girl named Candrāvalī (Ambalal 2004, p. 87). Multiple identifications are often found within these Vaiṣṇava circles.

The priests in the Vallabhasaṃpradāya sometimes even dress up as Krishna’s and Rādhā’s girlfriends (sakhīveś).23

There are many occasions in the hagiographies of the saints, which make it clear that things are really different from ordinary daily life if regarded on the alaukik level. All of the time, Krishna’s timeless world manifests itself. Within the Gauḍīyasaṃpradāya founded by the followers of Caitanya, there are texts in which the various saints are clearly identified with the characters of Krishna’s alaukik world. Two of these are the Kŗṣṇagaṇodeśadīpikā and the Gauragaṇodeṣadīpikā. Both are attributed to Kavikarṇapura of the 16th or 17th century C.E.

3.1. The Miracles of Śrī Nāth, His Gurus, and His Devotees

Śrī Nāth performs miracles. This is typical of Hindu gods. Krishna can do whatever he wants. In many cases, we can see that, on the one hand, there is a practical reason why he performs miracles. This is required because a suffering being needs to be delivered from suffering or saved from an enemy, for instance. Krishna lifts Mount Govardhan to protect his villagers against the rains of Indra. Even as a small child, he miraculously kills demons or delivers others from curses inflicted on them. As an incarnation of Viṣṇu, he kills the evil king Kaṃsa. That was the primary reason why Viṣṇu incarnated on earth as Krishna. On the other hand, many miracles are performed as part of a game, a play (līlā). This play is performed by Krishna to enjoy his own character, his own powers, to experience his own beauty, the beauty of others and of the world. When it comes to his play, he eschews all restrictions unless they suit him.

However, performing miracles is not restricted to the gods. Devotees sometimes do exactly the same. We can find this, for instance, in the account of Nanddās, number 4 in the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā. According to this account, Nanddās was the younger brother of the famous poet Tulsīdās, the composer of the Rāmcaritmānas. In Nanddās’ account, we find several episodes depicting interactions between the two brothers. Tulsīdās apparently does not accept Nanddās’ choice to remain in the Braj region, and for choosing Krishna instead of Rāma. One day, Tulsīdās comes to Braj to take his younger brother back to Ayodhya and to live there as a proper devotee of Rāma. Nanddās convinces Tulsīdās with his songs that he truly belongs to Braj and to Krishna. Both brothers then go to visit several temples. Nanddās, however, understands that Tulsīdās will only bow his head for Rāma, not for Krishna. Nanddās then requests Krishna, in this case in his form of the local svarūpa of Govardhannāth under worship in Gokul, to show himself as Rāma. Only then would Tulsīdāsbow his head. The result is there. Nanddās requests that Govardhannāth shows himself in the shape of Rāma. Govardhannāth obeys. He does so out of respect for a disciple of Viṭṭhalnāth.

Next to that, Raghunāth, one of the sons of Viṭṭhalnāth, is depicted when he is about to get married. Tulsīdās longs for a similar darśana he just experienced of Govardhannāth in the shape of Rāma. At the request of Nanddās and Viṭthalnāth, once more a miracle takes place. Raghunāth shows himself as Rāma, and his newly-wed wife takes on the form of Sītā. Only then does Tulsīdās bow down:

Hearing this pada, Tulsīdās remained silent. Nanddās Jī then went to have the darśana of Śrī Nāth Jī. Tulsīdās also went after him. When they had the darśana of [the image of] Śrī Govardhannāth Jī, Tulsīdās Jī did not bow his head. Then, Nanddās understood: ‘He does not bow for anyone else than Śrī Rāmacandra Jī’. Nanddās thought this in his mind here: ‘Let me make him have the darśana of Śrī Rāmacandra Jī in Śrī Gokul’. Then, as he (=Tulsīdās) should know the power of Śrī Krishna, Nanddās Jī made this request to Śrī Govardhannāth Jī. That dohā is:How can I describe the beauty of today, the Lord shines radiant.Tulsī will only bend his head, if you take bow and arrow in the hand.24Hearing this, a thought came to Śrī Nāth Jī out of respect for Śrī Gusāīm Jī: ‘What a servant of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī is saying, that I have to do’. Then, Śrī Govardhannāth Jī gave Tulsīdās Jī a darśana in the form of Śrī Rāmacandra Jī. Then, Tulsīdās Jī fell down for Śrī Govardhannāth Jī like a stick with the eight parts of the body25. After Tulsīdās Jī had had the darśana and he came outside, Nanddās Jī went to Śrī Gokul. Tulsīdās Jī also came with him. Once he had come there, Nanddās Jī had the darśana of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī and he bowed with the eight body parts stick-wise and Tulsīdās Jī also bowed down stick-wise with the eight body parts. And Tulsīdās said to Nanddās: ‘Let me have such a darśana here like the one you let me have over there’. Then, Nanddās Jī made a request to Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī: ‘This is my brother Tulsīdās. He does not bow for anyone else than Śrī Rāmacandra Jī’. Then, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī said: ‘Tulsīdās Jī, please have a seat!’. Now, Śrī Raghunāth Jī, the fifth son of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī, was standing there, and that day the marriage of Śrī Raghunāth Jī was celebrated. Then, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī said: ‘Raghunāth Jī! Your servant has arrived. Give him a darśana!’ Then, Śrī Raghunāth Lāl Jī and the bride Śrī Jānakī let him have a darśana in the form of svarūpas of Śrī Rāmacandra Jī and Śrī Jānakī Jī in their own person. Then, Tulsīdās Jī bowed down with the eight body parts like a stick. Therefore, Śrī Dvārakeśa Jī has sung in the Mūlapuruṣa:The reason for your high name became manifestWhen you obeyed the order of your father.And Tulsīdās became very happy after he had this darśana and he sang this pada:I will describe the village Āvadhigokul.After he had sung this pada, Tulsīdās took his farewell and he went back to his own country. Nanddās Jī was such a vessel of grace of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī, such a bhagavadīya (=devotee), that by his words, Śrī Govardhannāth Jī and Śrī Raghunāth Jī were ready to give darśanas wearing the shape (svarūpa) of Śrī Rāmacandra Jī.(prasaṅga 5)

In the case of this episode from the vārtā of Nanddās, it was Krishna who performed miracles at the request of Nanddās in the shape of the svarūpas of Govardhannāth and Śrī Nāth. Meanwhile, Krishna had a human shape in the form of Viṭṭhalnāth. As a result, Tulsīdās even understands in the pada he sings at the end that Avadh (another name for Ayodhya, the city of Rāma, and Gokul, which is connected to Krishna, are in fact the same, as Rāma and Krishna are the same.

However, as stated above, not only Krishna performs miracles. Miracles are also performed when Krishna is not directly present in the form of a mūrti or svarūpa. In the vārtā of the saint Cācā Harivaṃś (no.7), we come across the theme of walking on water owing to the immeasurable powers of faith. Cācā Harivaṃś can walk on water, and a Vaiṣṇava can follow him until he loses faith, a story resembling that of Christ and Saint Peter.

And one day Cācā Harivaṃś Jī went out to bring sāmagrī26 from Śrī Gokul for Śrī Nāth Jī. He loaded the sāmagrī on the head of a Vaiṣṇava and he went from Śrī Gokul. When he came to the stairs (ghāṭ) of the Yamunā then there was no boat. As it had become evening Cācā Jī thought: ‘It will be night till the sixth ghaŗī tomorrow morning and they will need this sāmagrī but the night needs to be passed first, and Gopālapur is ten kośas away. How can we reach it now?’ Thinking thus he said to that Vaiṣṇava: ‘I will walk on the Yamunā. Where I will put my feet and stand, on that very spot you should also put your feet and come’. Then, Cācā Harivaṃś began to walk on the Yamunā Jī and he started to say the name of the Lord. Then, that Vaiṣṇava came after him also saying the name. Then, that Vaiṣṇava thought in his mind: ‘Cācā Jī is taking the name of the Lord and I am taking the name of the Lord. Why should I put my feet on his footprints?’ When he started to put his feet on another spot then he started to sink into the Yamunā. Then, Cācā Jī came and took his hand and brought him to the other shore. Then, Cācā Jī said: ‘Why did not you put your feet on the spot where I put down my feet?’. Then, he said: ‘I was taking the name of the Lord and you were taking the name of the Lord’. Then, Cācā Jī said: ‘He listens to my words, he will now also listen to your words’. Such a vessel of grace was Cācā Jī that the Lord even listens to him.(prasaṅga 5)

The wondrous magical powers are indeed not restricted to the Hindu devotees of Śrī Nāth and Viṭṭhalnāth; even Muslim followers develop these abilities. In vārtā 17 on Alīkhān Paṭhān, we find proof of this. Alīkhān Paṭhān has become the governor of an area named Tavīsā. He comes to Mahāban in the Braj region and remains there. He was very strict in his ruling; anyone who harmed even a simple tree in Braj would be punished. One day, an oil-seller accidentally broke the trunk of a tree with his wagon. He was punished: all of his oil leaked out over the broken tree trunk. This theme is frequently found in India. It may be an attempt to heal the broken tree. Sometimes it is done with cowmilk or ghee. From that day onwards everybody understood the rigidity of Alīkhān Paṭhān’s rules and laws. Nobody dared to harm even a leaf of a tree in the Braj area (prasaṅga 1). However, Alīkhān’s rule continues. A thief is tested with oil:

One day a thief was brought before Alīkhān and that thief swore an oath saying: ‘I will put my hand in cooking oil and when the oil will become cold then you will believe that my word is true’. Then, Alīkhān had oil ordered and said: ‘The highest Lord (parameśvar) can make oil cold. He can make cold oil warm. Therefore, you should put your hand into cold oil. When that thief put his hand into the cold oil then his hand was burnt. Such a strong faith Alīkhān had in the highest Lord (parameśvar).(prasaṅga 2)

On another occasion Alīkhān wanted to donate a beautiful horse to Viṭṭhalnāth, as the latter had praised the horse’s beauty and speed. However, Viṭthalnāth refused to accept the horse. Alīkhān decided to become a disciple of Viṭṭhalnāth hoping that Viṭṭhalnāth would perhaps then accept the horse. However, there was a miraculous outcome to this: Śrī Nāth started to dance with Alīkhān’s daughter:

Then, Alīkhān understood in his mind: ‘If I will be his servant, then he will accept it [i.e., the horse]’. Then, Alīkhān became a servant and when Alīkhān started to do service, then Alīkhān’s daughter started to do service as well. Then, Śrī Ṭhākur Jī let Alīkhān’s daughter have an experience and he would dance with her. When Alīkhān heard this news and the priest (bhītar) said that there was the sound of dancing, and Alīkhān looked at it secretly, then Śrī Ṭhākur Jī entered and he would dance. Seeing this he very much started to praise his daughter.(prasaṅga 3)

Devotion to Viṭṭhalnāth and Śrī Nāth embodies particular powers as we have seen before: Madhavdās and his companion can safely pass through an area full of evil robbers. The power of devotion spreads. It radiates, and even non-Vaiṣṇavas and non-Hindus can become aware of this. It is portrayed in the account of Gaṇeśvyās (no. 31). He converts an aggressive, blood-demanding goddess to Vaiṣṇavism and vegetarianism.

The servant of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī, Gaṇeśvyās, his account

Now this Gaṇeśvyās knew the experience of Śrī Nāth Jī. One day, this Gaṇeśvyās brought the implements for Śrī Nāth Jī when on the road the rain burst out. He took shelter in a temple of Devī outside the village. However, the people said that if a man would stay there in the night, the goddess would eat him. Then, Gaṇeśvyās cleaned the temple of the goddess and whispered the eight syllabe mantra27 in her ear and slept there. Then, that goddess said in a dream to the Rājā of that village: ‘Now I am a Vaiṣṇava. You always send two goats to me, do not send these anymore. You should all become Vaiṣṇavas, otherwise I will cause harm to all of you!’. This matter the goddess told the Rājā in a dream. Then, that Rājā came to Gaṇeśvyās in the morning and asked him the entire matter. Then, Gaṇeśvyās came together with the Rājā. He had him made into a servant of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī. Such a vessel of grace that Gaṇeśvyās was that by contact with him the goddess and the Rājā became Vaiṣṇavas.(prasaṅga 1)

Another devotee, Gopāldās Segalakṣatrī (no.14), entered into the service of a foreigner (mleccha). However, Gopāldās would steal from his master and spend the possessions of that foreigner on Vaiṣṇava services, preaching (kathā), and the singing of songs and hymns (kīrtana). Yet his master is sure about Gopāldās Segalakṣatrī, and contrary to advice of others, he does not dismiss him. He is convinced that Gopāldās brings him good luck. The mind of this mleccha is eventually purified because of the presence of Gopāldās. Gopāldās embodies fortune and good luck according to that mleccha:

The servant of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī Gopāldās Segalakṣatrī, his account

That Gopāldās lived in Śrī Nandgāma. Now Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī came one day to Śrī Nandgāma. Then, Gopāldās let Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī come to his own house and everything that was inside the house that all he surrendered to him. Then, he started to do service to a mleccha and the riches of that mleccha Gopāldās would constantly spend on Vaiṣṇavas. Then, the servants of that mleccha said: ‘Throw him out of service, he is always spending money on kathās and kīrtanas!’ Then, that mleccha said: ‘Because of his good luck my riches constantly grow from day to day and he does not spend anything in worldly affairs. Therefore, how can he be removed from service?’. That Gopaldās was such a vessel of grace. Because of contact with him the mind of a mleccha became spotless. The vārtā is completed.(Vaiṣṇava 14)

3.2. Krishna and His Devotees Transgress the Ritual Rules

Śrī Nāth seems to be a completely autonomous god. He can do anything; whatever pleases him, so it would seem. Meanwhile, Vallabha and Viṭṭhalnāth typically have to stick to traditional instructions. They are high-caste and pure Brahmins. They have to defend Krishna and his miraculous acts. This is especially the case if he transgresses the regulations. These regulations and ritual instructions were often institutionalized by these gurus themselves. At times, they have to defend highly complicated situations. This makes their position paradoxical and their choices intriguing and complex. Some of Śrī Nāth’s devotees get so deeply involved in his games (līlā) that they misbehave in the eyes of the common Hindus. This may be so even in the eyes of Vaiṣṇavas, though they should be acquainted with Krishna’s games and the strange acts of his closest devotees. In the account of Govindsvāmī (no. 1, also named Govinddās), we see how Śrī Nāth plays horseback riding with Govindsvāmī, as any child could do with a parent or an uncle or so. Govindsvāmī goes very far in his role as a horse or elephant. He even urinates like an animal. When asked about this open misbehavior, Viṭṭhalnāth gives an explanation as he truly must defend his devotee:

Now Śrī Nāth Jī would always play together with Govindsvāmī in the forest and one day he would make Govinddās into as a horse, the other day into an elephant. Such games he would always play. One day Śrī Nāth Jī had changed Govinddās into a horse and he was sitting on him as a horseman. Now Govinddās urinated as a horse does. A Vaiṣṇava saw this, went to Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī and told him this. Then, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī gave the order: ‘Govindsvāmī is a horse or an elephant. How can it be that he would not imitate a horse or an elephant the entire way? Do not intervene in these matters’. Hearing this, that Vaiṣṇava remained silent. Such a vessel of grace was Govinddās.(prasaṅga 16)

Apparently, Govindsvamī plays with Śrī Nāth in the alaukik mode, but this is not recognized by the others. They can only see a urinating devotee. The above quotation explains what it may have looked like from the laukik side.

There are other examples of transgression of the rules by both Krishna and his devotees. The following two examples are also from the vārtā of Govinddās, who had developed a profound friendship with Krishna. The particularities of this episode may generally characterize close friendships between young boys. One day Viṭṭhalnāth was preparing the śṛṅgāra darśana, the elaborate ritual of midday in the temple. Śrī Nāth himself, however, would always play with Govinddās. Govinddās was singing in the temple now, but Śrī Nāth and Govinddās were so close that they enjoyed teasing each other. Śrī Nāth threw stones at Govinddās. Then, Govinddās threw a stone back at the image of Śrī Nāth. Even Viṭṭhalnāth was shocked now but Govinddās was able to explain what he did. It was Śrī Nāth who started the throwing even though the others present perhaps did not see this.

One day, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī was doing the śṛṅgāra of Śrī Nāth Jī. In the meantime, Govindsvāmī was singing kīrtana songs in the jagmohan temple hall. Then, Śrī Nāth threw eight stones at Govinddās. When Govinddās threw one stone back then Śrī Nāth Jī was startled. Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī then said: ‘Govinddās! What have you done?’. Then, Govinddās said: ‘He Mahārāj! You did not say anything when that complete idiot threw eight times stones at me!’ Hearing this, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī remained silent. Such a sakhābhāva [emotion of friendship] had Govinddās developed.(prasaṅga 8)

On another occasion, Śrī Nāth is afraid that Govinddās will beat him up, like small boys will do. Govinddās is thrown out of the temple by a priest but apparently Śrī Nāth still wants to see him. Śrī Nāth communicates this to Viṭṭhalnāth.

One day, Śrī Nāth Jī was playing with Govinddās. Then, Śrī Nāth Jī understood it was his turn, but then it became time for the utthāpan ceremony and Śrī Nāth Jī ran away and snuck into the temple. Then he (=Govinddās) also entered the temple and threw stones at Śrī Nāth Jī. Then, the servant Ṭahelbāna pushed Govinddās and threw him out and held the utthāpanbhoga ceremony. Govindsvāmī went away and sat down on the road and said: ‘Now Śrī Nāth Jī will come on this road together with the singers and I will give him a blow!’ Later, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī came into the temple after he had taken a bath and he saw that Śrī Nāth Jī was dejected and that the sāmagrī of the utthāpan was not healthy. Then, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī asked Śrī Nāth Jī how he was. Then, Śrī Nāth Jī said: ‘As long as you will not settle the memory to Govinddās for me, nothing will please me! Therefore, let me go on that road and without playing with him nothing can go on. However, if I go on that road now, he will give me innumerable blows. Out of this concern nothing pleases me. If Govinddās comes then it will please me’. Hearing these words and seeing the affection of Śrī Nāth Jī towards his devotees (bhaktavatsalatā), Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī’s heart ran over. He had Govinddās called over and conciliated and he made the request to Śrī Nāth Jī saying: ‘He is present now, he has come’. Then, Śrī Nāth Jī became healthy again. Such a vessel of grace was Govindddās.(prasaṅga 19)

In the vārtā of Cācā Harivaṃś Jī (no. 7), we find yet another proof of the transgression of the ritual rules by both Śrī Nāth and his devotee. On the other hand, we also see here the visionary powers of an important poet-saint. In this case, it is the renowned Sūrdās. Sūrdās is considered within the puṣṭimārga to have been one of the most important disciples of Vallabha.28 In the story, it is time to blow the conch shell in order to wake up Krishna. All the temple priests, the bhītariyās, are waiting for Cācā Harivaṃś to blow the conch shell. Cācā Harivaṃś, however, realizes that Krishna is still in deep sleep. After two hours, Viṭṭhalnāth comes there and wonders why Krishna is not awake yet. Then, the conch is blown. Still Krishna does not wake up. It is only after the great saint Sūrdās’s sings a pada that Krishna gets up. It is no exaggeration to state that the poet-saint Sūrdās is the most famous of the Brajbhāṣā Krishna poet-saints. According to the legendary accounts, he was blind since childbirth. Therefore, it is often stated that what he sees is the direct result of his seemingly unlimited powers of poetic sight. It is the result of his ability to take part in the līlā. What Sūrdās sees is a direct revelation that can be compared to the Veda. According to the Bhāvaprakāśa commentary on the Caurāsī vaiṣṇavana kī vārtā of Harirāy, Sūrdās was a manifestation of a celestial being that during the daytime took part in the līlā as a sakhā, a cowherd boy who went to the forest with Krishna. At night, he was a sakhī, a female companion of Krishna (Barz 1976, p. 106). As a sakhā, he was named Krishnasakhā, as a sakhī, his name was Campakalatā. For this reason, he was able to have such a complete and overall view of the līlā. Once more, his laukik form was that of a blind poet-singer. His alaukik form was that of a gopī at night, and a gopa during the day. Both Sūrdās and Cācā Harivaṃś understood why Śrī Nāth was still sleeping. Both the god and his close devotees transgress the rules here:

One day, Cācā Jī went up on Girirāja (i.e., the mountain Govardhana) and prepared for blowing the sound of the conch. However, Cācā Harivaṃś found that Śrī Nāth Jī was in deep sleep. Then, he did not blow the conch. All the bhītariyās stood there. After two hours, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī came, but when he had the sound of the conch produced, still Śrī Nāth Jī did not wake up. Then, Sūrdās sang a pada. That pada is:Son of Nanda, what habit is this?It is dawn, at the moment of awakening,Pītāmbara29 stretches out and sleeps’.Hearing this pada, Śrī Nāth Jī woke up. Such a vessel of grace was Cācā Jī that Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī would listen to him and that he had all memory of the fame of Śrī Ṭhākur Jī (i.e., Krishna).(prasaṅga 7)

3.3. Krishna Is Subordinate to the Ritual Rules of Viṭṭhalnāth and the Saṃpradāya

Meanwhile, in other cases, Śrī Nāth tries to behave as properly as possible. He even tries to return to his temple so the ritual order is not disrupted. We already saw this in prasaṅga 19 of the account of Govinddās. Apparently, he snuck out to play with his devotees, but is still subordinate to the daily ritual structure of the darśanas. This is of course quite paradoxical. Is it Krishna who sets the rules or is it to the Brahmin ritualists? Or is it rather Vallabha and Viṭṭhalnāth who do this? Of course, the powers of the ritualists are basically unlimited. They speak the divine Sanskrit to which every god obeys. Yet, it is paradoxical. Who rules whom? This theme of obeying the Brahmin institutions can be found for instance on another occasion in the account of Govinddās:

One day, Śrī Nāth Jī had climbed a sāma tree (sāmaḍāk) and shone there and he played his flute. Govinddās was sitting on another hill and watched him. At that time, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī had bathed and he came on Śrī Girirāj to perform the utthāpan ceremony. Śrī Nāth Jī was looking from the sāma tree and quickly jumped from there. The cloth of his garment got torn and a piece of cloth remained in the bushes. When Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī opened the door and looked in order to perform the utthāpan, he saw that the cloth of the garment was torn. He asked the people whether anyone had entered there, but all said that was not the case. When he started to think on this matter then Govinddās said: ‘Why do you think about this matter, don’t you know what boys are like? They are naughty. He jumped from the sāma tree and got the cloth of his garment torn. If you come I will show you that a piece of cloth is still hanging’.

Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī came there and took that piece. Then, Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī asked Śrī Nāth Jī: ‘Why were you in such a hurry?’ Then, Śrī Nāth Jī said: ‘It had become time for the utthāpan and you had taken a bath and you came in. Therefore, there was such a rush’. From that day onwards such an arrangement was made that the utthāpan would only be performed after the bell resounded three times, the conch would be blown three times, and then, only after waiting twenty seconds, they would open the doors of the temple. Such a vessel of grace was Govinddās.(prasaṅga 14)

It is remarkable from these accounts that on the one hand Śrī Nāth transgresses the rules, and on the other hand rigidly sticks to them. This same tension can be seen in Krishna himself, who on the one hand preaches the dharma to Arjuna in his renowned Bhagavadgītā and on the other hand, he seduces young girls into leaving their families and enjoy his company in the forest. Thus, on the one hand, there is protection of the dharma, while on the other, there is severe transgression of it. Krishna can do whatever pleases him so it seems. He sticks to rules if he desires to do so, but just as easily leaves them behind. All for the fun, the līlā aspects of it. Yet, at times, he takes obedience to the rules so seriously, one could consider it to be extreme. Meanwhile, he has to save the universe. Regardless of these paradoxes, his transgression has as the result that the rituals are adjusted to accommodate his playful acts.

This type of transgression is not exceptional within Vaiṣṇavism. It can at times be observed among Vaiṣṇavas even today. The Brahmin ritualists sometimes have difficulties explaining the odd acts of their disciples. Meanwhile, they have to interpret the strange acts in light of official Vaiṣṇava doctrines. I have noticed this several times during my fieldwork in the Braj area.

In the account of Ajabakuṃvara Bāī (no. 47, we see how Śrī Nāth on the one hand surely understands the importance of the ritual order of the day. He must be present in the Braj area for the worship by Viṭṭhalnāth and his sons. This ritual order may not be disrupted. However, meanwhile, he knows how to escape from it in order to be with a devoted woman, Ajabakuṃvara Bāī.

The servant of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī, her account

That Ajabakuṃvara Bāī lived in Mevāṛ. One day when Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī came there, it was for Ajabakuṃvara Bāī the darśana of the complete highest person in his own shape. Then, Ajabakuṃvara Bāī became Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī’s servant, and all eight watches of the day, her mind was stuck in the lotus feet of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī. When Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī was about to leave then Ajabakuṃvara Bāī fainted. When Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī saw her in such state, he shone there for four days longer and he had for Ajabakuṃvara Bāī his wooden sandals (pādukā) installed [in her private shrine for instance]. Then, Ajabakuṃvara Bāī started to do service according to the ways and standards of the pure puṣṭīmārga.

Now Śrī Nāth Jī always played caupaŗ (chess) with Ajabakuṃvara Bāī. And in the mind of Ajabakuṃvara Bāī came such a thought: ‘If Śrī Nāth Jī would always shine here it would be good’. One day, Śrī Nāth Jī was pleased with Ajabakuṃvara Bāī and said to her: ‘Whatever you ask!’. Then, Ajabakuṃvara Bāī asked ‘Shine here forever!’. Then, Śrī Nāth Jī said: ‘Śrī Gusaīṃ Jī and seven sons of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī will perform my service here directly on the earth; therefore, I cannot directly leave the mountain Govardhan, but afterwards I will come here and I will always straightly continue to come!’. Hearing such words, Ajabakuṃvara Bāī was very happy in her mind. Therefore, for making the words to Ajabakuṃvara Bāī true, Śrī Nāth Jī is now naturally shining in Mevāṛ. How can her vārtā be told? The vārtā is completed.(Vaiṣṇava 47)

Śrī Nāth respects the temple rituals, but after these, when he is supposed to sleep inside his temple, he escapes, goes to Mewar (Mevāṛ) and is present there to play chess with Ajabakuṃvara Bāī. He obeys the rules and yet transgresses them.

Similar stories play in other Vaiṣṇava temples, where Krishna or Viṣṇu in fact desire to see each and every devotee, but the Brahmin rules can be so strict that they must be adhered to instead. In Jagannāth Puri, the god Jagannāth, equated to Krishna, longs to see anyone who visits the site. Yet, entrance to the temple is restricted. This mainly has to do with ritual purity. There are many stories how Jagannāth escaped from his temple and his Brahmin ritualists. He does so, for instance, to see a low-caste person who wants to pay homage to him. Jagannāth and his brother and sister even come out of their temple for the car festival (rathyātrā) out of this desire to see those who cannot enter. Close to the Jagannāth temple, there is a small temple that is accessible to anyone, irrespective of caste or origin. In another adjacent village, Jagannāth remains inside the temple, but his hands one day reached out to an impure low-caste devotee through the walls.

3.4. Śrī Nāth, Viṭṭhalnāth, and Muslims

Among the stories in the Do sau bāvana vaiṣṇvana kī vārtā, several accounts can be found depicting how Śrī Nāth and Viṭthalnaṭh dealt with Islamic beliefs, or Muslims who came to visit Braj, or who tried to contact, for instance, Vaiṣṇava singers and other artists. On the one hand, the Vallabhasampradāya is open to foreigners. This is more often the case with Vaiṣṇava denominations. On the other hand, there are always the concerns of purity and impurity. Sometimes, Śrī Nāth is touched by the devotion of a foreigner (mleccha), usually a Muslim. In these cases, indeed, the purity/impurity paradox plays a part. This may even be the case for Śrī Nāth personally. If he accepts devotion from a Muslim, he might not be pure enough anymore for confronting Viṭṭhalnāth himself. Solutions must be found. In other cases, the visions and experiences of a foreigner can be so intense that everybody is impressed, pure or not.

An example of this Is the account of Raskhān (no. 218). According to his vārtā, Raskhān was a Muslim, a Paṭhān from Delhi. He fell in love with the son of a banker. He would go so far in his love for this boy that he would even eat the leftovers of his meal, abhorrent in orthodox Hindu eyes. One day, he hears a few Vaiṣṇavas preach on Krishna. One should be as concerned about Krishna as Raskhān is for the banker’s son. Raskhān’s attention is drawn and he asks for the Vaiṣṇavas to show him a picture of Śrī Nāth. He sees a picture and immediately leaves for Gopālapura. There, he changes his clothes, most probably in favor of Vaiṣṇava clothing, and visits various temples. He is disappointed, however. Afterwards, he goes to see Śrī Nāth, but he is recognized as not being a Hindu. He is thrown out of the temple:

Now follows the account of the disciple of Śrī Gusāīṃ Jī, Raskhān, a Paṭhān who lived in Delhi. In Delhi lived a banker. The son of this banker was very handsome. Raskhān’s mind was deeply attached to that boy. He would follow him and eat his leftovers30 and serve him all day long. Earning a salary was not there, day and night he remained attached to him. The other people of high birth slandered Raskhān in many ways, but Raskhān did not listen to anybody and all the time his mind was attached to the son of that banker.One day, four Vaiṣṇavas had come together and they were telling the story of the Lord. Whilst doing so, a word fell that one should attach the mind to the Lord as Raskhān’s mind is attached to the banker’s son. Meanwhile, Raskhān emerged on that road. He heard these words. Then, Raskhān said: ‘What are you saying about me?’ Then one of the Vaiṣṇavas spoke the word that had been said.Then, Raskhān said: ‘If I see an image of the Lord, my mind will be attached’. Then, the Vaiṣṇavas showed him a picture of Śrī Nāth. As soon as Raskhān saw it, he took the picture with him, and in his mind, he made a decision to see that image (svarūpa). He took a meal and came from there in one night to Brindavan, seated on a horse. He changed his clothes31 and the whole day he lingered in all the temples. And in all the temples he had a darśana, but when there was not such a darśana (i.e., such a darśana as he longed for), he went to Gopālapura and after changing his clothes one more time he went to have the darśana of Śrī Nāth Jī. Then, the guardians recognized the mark of a highborn one32 according to the will of the Lord. They gave him a stroke and threw him out. They did not allow him to enter. He left and remained on Govind Kuṇḍ.33 He lay there for three days. He did not pay any attention to taking food or drinking.

Poor Raskhān lies outside the temple, but Śrī Nāth understands the purity of his intentions. He shows himself to Raskhān. Raskhān runs after Śrī Nāth who feels threatened by this overflow of passionate devotion. He flees and tells Viṭṭhalnāth to initiate Raskhān. Raskhān is pure as a being, but impure because he is not a Vaiṣṇnava. He is a foreigner (mleccha). Viṭṭhalnāth must initiate him, otherwise Śrī Nāth cannot accept anything from Raskhān due to his impurity as a foreigner.