Abstract

The purpose of this article is to study the Romanian Orthodox place of worship of Lunghezza in Rome, utilizing the expression ‘shared religious place’ and thus referring to the shift from secular to religious and asserting that it is now a camouflaged religious place. Using GIS mapping and Digital Humanities methods and tools, the paper analyses the geographical presence of Orthodox Romanians in the Metropolitan City of Rome territory and the architectural typologies of their places of worship. The history and geography of the church in Lunghezza, a former stable converted into a house of worship, reveals the form of the resilience of the Romanian Orthodox parishes, forced to find various and compelling solutions in order to survive as places of worship.

1. Introduction

This article is framed in the re-contextualisation of the notion of ‘sacred space’ on which this monographic session focuses: it analyzes within an interdisciplinary framework the history and the geography of a ‘religious place’—the Romanian Orthodox Church of Lunghezza in the City of Rome (Municipio Roma VI), Italy. In relation to this space, we wish to demonstrate the effectiveness of the expression ‘shared religious place’ as a manifestation of diachronic sharing—from secular to religious (having never been considered sacred). Moreover, this place is camouflaged because it has become religious but maintained its secular nature both legally and formally: we consider the camouflage a hybrid form between visibility and invisibility, sometime the result of a top-down process that induces communities to retire in a condition of ambiguity in order not to attract media and political attention; hence, the form between religious and secular is a good example of camouflage. It also expresses a mode of resilience that manifests itself in the possibility of surviving despite difficult external conditions, as we will illustrate in the paper, be they social, political or material, that undermine the solid religious collective dimension of the community that has chosen this place as its home.

After this introduction, in the Section 2, we analyze the meaning of the expression ‘shared religious place’, highlighting the heuristic potential of this label in the historical-religious analysis of space. In the Section 3, we illustrate the multi-disciplinary methodology on which this article is based, highlighting, in particular, the novelty of the use of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) mapping and Digital Humanities. The Section 4 focuses on the spatial analysis of the Romanian Orthodox presence on the territory of the Metropolitan City of Rome. This was achieved through the support of GIS mapping. By starting with ad hoc cartographies elaborated through the superimposition of different quantitative and qualitative georeferenced data, it was possible to reveal two specific geographies. The distribution of the Romanian Orthodox places of worship is followed, in Section 5, by a classification of the architectural typologies of places of worship (parish churches, monasteries and hermitages) on the basis of two dynamics: (1) from secular to Orthodox substitution; (2) from Catholic to Orthodox substitution.

In the Section 6, we then undertook a description of the history of the parish of Lunghezza, dwelling on its peregrinate on different sites. This determined its identity as a diachronic shared place but also as a camouflaged place. In the Section 7, this quality is particularly apparent as the interior furnishings which characterize this space as a place of worship are in dialectical opposition to its external shell and its non-legal recognition as a church. Onsite digitization enabled us to study its volumes, in particular its plan, elevation and section, which otherwise would not have been readily available. This reflection on camouflage is developed in the conclusions in which new research perspectives are also outlined, starting from the methodological insights that this text makes apparently promotes.

3. Methodological Sketches

Our paper employs multiple research methods from various disciplines (i.e., Religious Studies, Geography of Religions, Sociology, and Digital Humanities) and also relies on ethnographic tools (on-site visits and interviews with the main actors involved).

In particular, in addition to the geo-historical approach already used elsewhere by the authors in the study of religious places (Cozma and Giorda 2020, 2022; Federici 2022; Giorda 2020, 2022; Omenetto and Giorda 2021), through the methods of historical–critical reading of sources and social sciences, based on fieldwork and interviews, the perspective provided by GIS and Digital Humanities is added here.

GIS is a term introduced in the latter half of the 1960s by Roger Tomlinson, and it is defined in different ways by different authors (Smith and Tomlinson 1992; Tomlinson et al. 1976). A database system in which most of the data are spatially indexed and upon which a set of procedures operates in order to answer queries about spatial entities in the database (Smith et al. 1987, p. 13). An information technology that stores, analyses and displays geographic data and not geographic data (Parker 1988, p. 1547). The adjective ‘geographic’ indicates that the information entered always has a spatial reference, a georeferencing; ‘Informative’ means that a series of information can be associated with the data. The noun ‘system’ indicates an integration between the user of the software and the hardware in order to obtain information that supports the analysis, data management and implementation of strategies. A system includes processable digital images, a database, geostatistical software, and tables with associated functions (Meijerink et al. 1994). In other words, a GIS is a computer-based information system that provides tools for collecting, integrating, analyzing, modeling and visualizing data related to an accurate cartographic representation of objects in space. The system is capable of processing spatial (maps, aerial photos, etc.) and descriptive (names, tables) data, storing them, analyzing them spatially and statistically and visualizing them both on the computer screen and on paper in the form of graphs or maps.

Despite the initial diffidence with which some geographers greeted the use of this technology (Macchi Jánica 2019), GIS has been providing numerous opportunities for spatial analysis for 30 years now. This tool is adopted, for example, in environmental studies, in the geographical analysis of historical events, in the survey of new economic infrastructures, in the context of sustainable economic development, in the analysis of tourism potentials and criticalities, in the involvement of local communities in environmental governance, in land management and planning, in geo-sanitary and medical issues, in geopolitical and electoral issues, and in geography teaching. As already pointed out elsewhere (Omenetto 2019), its use still remains limited in the study of religions and restricted to the localization of the religious object in geographical space despite the fact that some works have shown that the potential of GIS goes beyond mapping alone (Kwan 2008).

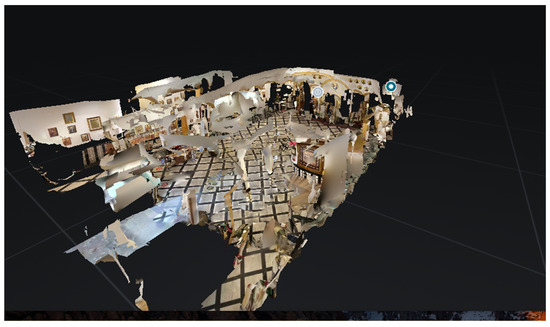

The study of Sacred Sites can greatly benefit through the use of a Digital Humanities perspective. Indeed, the latter have challenged all disciplines to engage with new interdisciplinary methodologies, innovative technologies, and original approaches to pedagogy. Digital visualization technologies, including laser printers, 3D modeling and virtual/augmented reality, revolutionize our critical engagement with the study of sacred sites. The transformation of physical spaces over time was originally approached through traditional building design, largely reliant upon two-dimensional technical drawings (plans, elevation, sections). The study of the transformation of places from secular to sacred can greatly benefit from the volumetric analysis of existing structures, as the architectural choices both in the refurbishments of the sites, but also of the liturgical apparatuses are indicative of the use of space by the community either lay or religious. With these considerations in mind, we have decided to use a software called Matterport that is traditionally used in the real estate industry.

Matt Bell founded Matterport after the release of Microsoft Kinect and saw its potential to create 3D environments to give users an immersive feeling of space in virtual reality.2 In the same way that photography became an instant automated process to capture moments, Bell and cofounder Dave Gausebeck achieved this for entire 3D spaces.3 Ultimately, the challenge was represented by getting in color and depth data, and as you move the camera from spot to spot, the software stitches together all of the data into a coherent 3D model. Through the combination of 360-degree panoramic photographs, the system renders a reproduction of spaces and environments that are surprisingly real, whether indoors or outdoors.4 Ultimately, Matterport technology aims to break down the barriers between the physical and digital worlds creating digital twins that can be used in virtual reality.5 The added value of VR is that it enables the study of space in 3D, enhancing a deeper understanding of space. Immersion motivates understanding of building structures, and information is processed more effectively by offering a deeply immersive sense of place and time. While the sustainability of Digital Humanities is at the forefront of current debates, we aim to use 3D and VR technology to study architecture and the changes in space over time.

4. The Distribution of the Romanian Orthodox Places of Worship between Rome and Its Metropolitan Area

According to data provided by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), as of 1 January 2022, Romanian citizens in the Metropolitan City of Rome constituted the first foreign collectivity with 152,076 persons (out of a total of 1,076,412 in the whole of Italy) out of a total of 516,297 foreigners residing in the same area (out of a total of 5,171,894 in the whole of Italy).6

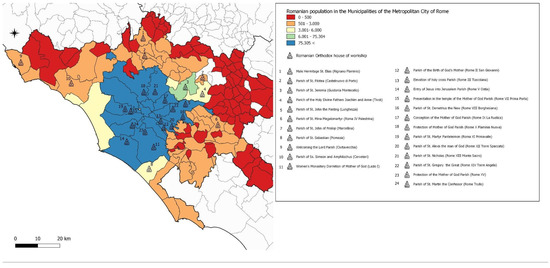

However, we are aware that not all Romanians are Orthodox and that, at the same time, there are non-Romanian Orthodox (Guglielmi 2022). Thus, with due care in the transposition of the statistical data (Bossi 2018), we focus here on the Romanian Orthodox Diocese of the Patriarchate of Romania in the territory of Rome and its province. Founded in 2007 in Italy, the Romanian Diocese has today around 291 permanent places of worship (i.e., 287 parish churches, 6 monasteries, 2 hermitages, and 6 diocesan chapels) and 138 temporary places of worship (missions).7 According to the Romanian Diocese’s website, the Metropolitan City of Rome is home to twenty-four parishes, a monastery, and a hermitage (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the Romanian resident population in the municipalities of the Metropolitan City of Rome (1 January 2021) and mapping of Romanian Orthodox places of worship (churches, monasteries, and hermitages). Source: Cartographic elaboration by SO on data from the website of the Romanian Orthodox Diocese of Italy.

On the same territorial area, the Diocese is structured on three main jurisdictions that overlap only partially with the administrative boundaries of Rome and its province.8 As for the Orthodox parishes in the Capital, apart from Rome I, which is the headquarters of the Romanian Orthodox Diocese in Italy on Via Ardeatina (n. 1741), these are managed by the Lazio I deanery (which includes Rome II San Giovanni, Rome III Tuscolana, Rome V Ostia, Rome Ostia II, Rome VIII Borghesiana, Rome IX La Rustica, Rome XI Primavalle, Rome XII Torre Spaccata, Rome XIV Torre Angela and Rome Trullo) and by the deanery Lazio II, which corresponds to Rome IV Palestrina, Rome VI Tor Lupara, Rome VII Prima Porta, Rome X Flaminia Nuova, Rome XIII Monte Sacro and Lunghezza. The remaining municipalities in the metropolitan area are also divided between the deaneries Lazio I (Ciampino, Civitavecchia, Fiumicino and Marino), Lazio II (Fiano Romano, Guidonia, Marcellina, Riano, Rignano Flaminio and Tivoli) and Lazio III (Albano, Anzio, Ardea, Monte Compatri, Nettuno, Pavona, Rocca di Papa, Valmontone, Velletri and Zagarolo).

By superimposing the data on Romanian residents provided by ISTAT and the mapping of Orthodox realities made available by the Romanian Diocese, we may observe that the geography of places of worship is characterized by a relatively uniform distribution in the Municipi of Rome, with a greater concentration in the south-east quadrant of the Capital and the metropolitan area. On 1st January 2021, Rome alone housed 75,305 Romanian residents and no less than fifteen Romanian Orthodox places of worship. The latter are distributed in ten of its fifteen municipalities. In particular, they predominate in Municipi VI, VII and IX, where between two and three places of worship are active.

Widening our gaze to the Metropolitan City (Figure 1), in second and third place in terms of the number of residents of Romanian nationality, with a not inconsiderable gap, are Guidonia Montecelio and Tivoli, with 6138 and 4403 inhabitants of Romanian nationality, respectively. There is a parish in both municipalities: Guidonia Montecelio is home to the Romanian Orthodox parish consecrated to St. Jeremiah, and in Tivoli, there is the parish dedicated to Sts. Joachim and Anne. Next is Pomezia, the seat of the St. Sebastian Romanian Orthodox parish and residence of 3831 Romanians; Cerveteri seat of the Sts. Simeon and Amphilochios Romanian Orthodox parish of and residence of 1680 Romanians; Civitavecchia seat of the Welcoming the Lord Romanian Orthodox parish and residence of 1620 Romanians; Palestrina seat of the St. Mina Megalomartyr Romanian Orthodox parish (Roma IV) and residence of 1489 Romanians; Rignano Flaminio where the men’s hermitage of St. Elijah and the parish of St. Elijah operate in the same place, for a potential catchment area of 1087 Romanian residents.

In addition to a prevailing distribution in the south-eastern area, a second element emerges from the cartographic analysis: the Orthodox communities belonging to the Romanian Orthodox Diocese of Italy are also located in those municipalities with a population of Romanian nationality below one thousand. This is the case of Marcellina, with 897 residents and Castelnuovo di Porto with 612 residents. In these two municipalities, the St. John of Prislop parish and the St. Philothea parish are active, respectively.

5. A Classification of the Architectural Typologies of the Romanian Orthodox Places of Worship in the Metropolitan City of Rome

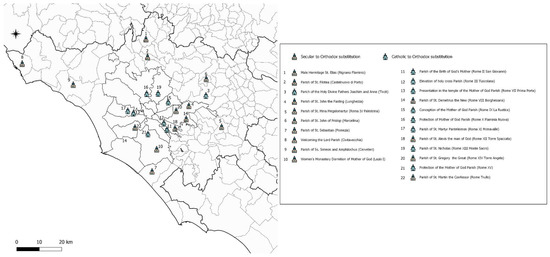

On the basis of the classification already made by Maria Chiara Giorda (Giorda and Longhi 2019; Cozma and Giorda 2020, 2021; Giorda 2023), the territory of the province of Rome presents a preponderance of religious places that change from one religion to another, and secular places converted into religious places (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Classification of architectural typologies on the basis of (1) secular to Orthodox substitution; (2) Catholic to Orthodox substitution in the Metropolitan City of Rome. Source: Cartographic elaboration by SO on data of Cozma and Giorda (2020).

On the Capitoline territory, the use of facilities—or parts of them such as parish halls and theaters—made available by Catholic parishes predominates. As Maria Chiara Giorda highlights (2023), out of the fifteen Romanian parishes present in Rome’s Capital, eight of them—Rome II (The Birth of the Mother of God), Rome III (The Elevation of the Holy Cross), Rome IX La Rustica (The Conception of the Mother of God), Rome X (The Protection of the Mother of God), Rome XI (St. Martyr Panteleimon), Rome XIII (St. Nicholas), Rome XV (Protection of the Mother of God) and Roma XVI9—have spaces for worship within a Catholic church. This hospitality is guaranteed and made easier by the number of Catholic structures, which open up and offer portions of space to other Christians, creating a city that is increasingly, even in disguised or invisible form, plural. Also part of this dynamic of substitution is the architectural conversion of Catholic churches to Orthodox places of worship. For example, the Presentation in the Temple of the Mother of God parish (Rome VII Prima Porta) purchased a privately owned Catholic church in 2021, not used for Catholic celebrations since 2000.10

Secular buildings converted into places for Orthodox worship prevail in the southeast quadrant of Rome and its metropolitan area (Figure 2). Six of these are located in the Municipalities bordering the Capital: the parish’s church/hermitage of St. Elijah in Rignano Flaminio; the St. Philothea parish’s church in Castelnuovo di Porto; the St. Mina Megalomartyr parish’s church in Palestrina (Roma IV); the St. John of Prislop parish’s church in Marcellina; the St. Sebastian parish’s church in Pomezia; the Welcoming the Lord parish’s church in Civitavecchia; and the Sts. Simeon and Amphilochios parish’s church in Cerveteri. The remaining five are located in Rome—Rome I (Dormition of the Mother of God Monastery), Rome VIII Borghesiana (St. Demetrius the New), Rome XII Torre Spaccata (St. Alexis the Man of God), Rome XIV Torre Angela (St. Gregory the Great), Rome Trullo (St. Martin the Confessor) and Lunghezza (St. John the Faster), the subject of our research. These are often the transformation of buildings previously used for residential or commercial, public or private use.

The Dormition Monastery was a villa used as a private residence by a family purchased in 2008 by the Romanian Diocese and converted into its administrative residence and a female monastery (Giorda 2019b). Another building type is the one used by the St. Martin the Confessor parish, founded in September 2020 in the area Trullo-Magliana, in Rome. The place of worship is, in fact, located in a building that used to be a nursery school that remained unused for more than ten years, undergoing a major renovation financed entirely by the Romanian Orthodox congregation. The parish of Sts. Simeon and Amphilochios opened in Cerveteri in 2016, folded into a basement space of an apartment building previously used as a car workshop, while the parish and hermitage of St. Elijah in Rignano Flaminio was previously an industrial shed. The parish of St. John the Faster in Lunghezza has changed its places of worship several times, always opting for a building of a secular nature. First in a 120 square meters shed, today in a former farm building. The latter not only falls into the category of buildings that have moved from the secular to the religious but shows how substitution can take place without losing the legal and physical/material status of a secular place. We are thus faced with a hybrid typology of substitution from the secular to the religious.

6. A Stable Becomes a Place of Worship: The Case Study of Lunghezza

The St. John the Faster (Parohia Sfântul Ierarh Ioan Postitorul) Romanian parish in Lunghezza has been distinguished by the reuse of secular spaces since its foundation in 2013. The creation of the parish was preceded by the mission of Benedict Firulescu, ordained by Bishop Siluan and tasked with the mission to organize the parish in Lunghezza.

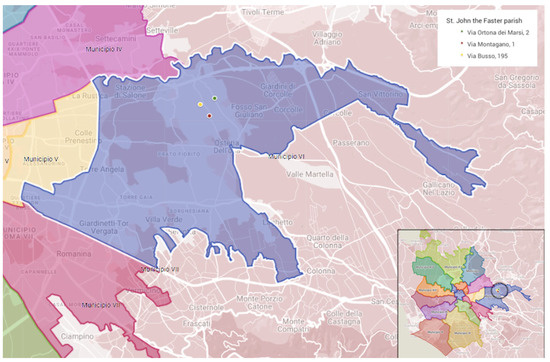

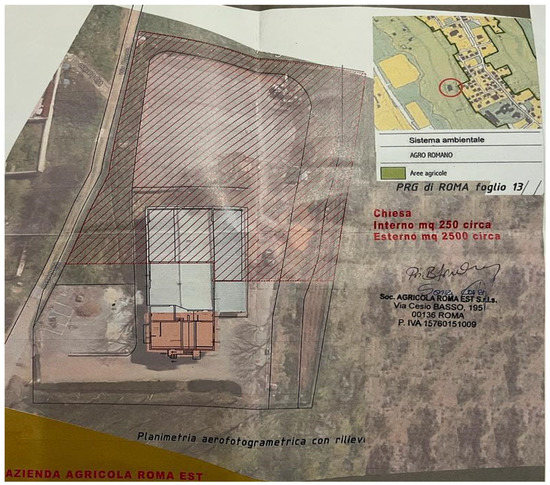

The first place of worship of the parish was in a rented warehouse of 120 square meters, located in Via Ortona dei Marsi 2 in Lunghezza, which was converted into an Orthodox place of worship (Figure 3). Due to financial difficulties (the parish could no longer afford to pay the increased rent), the parish was forced to move to another location in 2016, this time a garage of about 160 square meters on Via Montagano 1 in Prenestino. In his recent interview (15 November 2022), Fr. Benedict explained that the place was not suitable for a church since it was flooded several times. In the summer of 2020, two Romanian entrepreneurs (brothers Teodor and Nicolae Blendea) from the parish offered their help to move to another location. Upon Fr. Benedict’s suggestion, Teodor Blendea bought a 2500 square meters property in September 2020, located on Via Busso 195, in Valle Longa-Lunghezza (only a few streets from Benedict’s house), which also included an abandoned stable of 250 square meters and an annexed building.

Figure 3.

Displacement of the parish seat. Source: Elaboration on Google Maps by SO.

The Blendea brothers decided to transform the stable into an Orthodox place of worship and the annexed building into a residence for Teodor, but without modifying the exterior of the whole building.

As Fr. Benedict told us (15 November 2022), the works of conversion of the stable into a place of worship were made and financed by Blendea’s brother’s construction company and were completed in three months, from October to December 2020, for a total sum of 180,000 euros, which also included the purchase price of the property. The conversion process also relied on the work of volunteers, including the parish priest, who regularly works on construction sites to support his family. At the end of the works, the parish signed a six years rent agreement with the Blendea family’s agricultural company (Società Agricola Roma Est Srls) to use the house of worship and the whole property, except Teodor Blendea’s house (delimited by a high fence), for a monthly lease of 1,000 euros. Benedict said Teodor promised after the end of the six-year-long rent agreement, all the property, except the house, would be donated to the parish. Moreover, Teodor has underlined many times his plan to build a real Orthodox church on the property, following the Romanian Orthodox tradition (Benedict, 15 November 2022).

Religious services are held every Sunday morning from 9 AM to noon, on Friday and Saturday evenings at 6 PM, and on all Orthodox feast days during the week.

7. Inside the Place of Worship

The place of worship originally consisted of a large rectangular hall measuring 20 × 11 m (Figure 4) and was divided across the middle by a water trough for the cattle occupying a surface area of approximately 250 square meters (Figure 5). Although the renovations drastically changed the interior of the stable, this artificial watering point was left as it functioned as a symbolic reminder that “Christ too was born inside a stable,” as Fr. Benedict pointed out in the interview (15 November 2022). The gable roof covering and the exterior whitewash of the church reveals nothing of its interior furnishings—which stand in stark contrast with the modest shell that envelops them (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Plan of the church.

Figure 5.

The church of Lunghezza during construction works.

Figure 6.

The church of Lunghezza during construction works.

The large rectangular hall is divided into two rooms. The first one measures 6.31 by 11.7 m and is framed on the two short sides by three arches sustained by pillars (Figure 7). These create two adjacent rectangular rooms that are, respectively, used as a shop for candles, incense, icons and other ecclesiastical items and a space to host small religious services (i.e., memorial services, thanksgiving prayers) and ceremonies. In Orthodox Byzantine architecture, this room corresponds to the so-called ‘narthex.’ Access to the second larger room, which measures 12.99 by 11.7 m, is given by three arches (the central one larger than the adjacent ones), always supported by pillars. This main room is the space for the laity, the so-called ‘naos,’ or nave (Marinis 2013) and is characterized by two small aisles; on the eastern end of the left aisle, relics of different saints can be venerated. There is also the place where the priest makes the confessions. On the east end of the main room is the sanctuary (or the altar), separated by a plaster wall called ‘iconostasis’ and filled with various icons according to the liturgical tradition.

Figure 7.

Church interior with matter tags.

The iconostasis has three sets of doors (called ‘holy doors’ or ‘royal doors’) in the center, exclusively used by the clergy, and two side doors (called ‘deacon’s doors’), also used by those who help the clergy inside the altar (except women, who are not allowed to enter into the altar in the Orthodox tradition). On the opposite sides of the holy door are the icons of Christ and the Virgin Mary; toward the ends of the iconostasis, next to the deacon’s doors, are placed two wood aedicula, used to carry the icon of St. John the Faster (on the north) and the icon of the Virgin Mary (on the south), respectively. At the top of the iconostasis are icons of the apostles. It should be outlined that the architecture of the Orthodox places of worship carefully distinguishes the three areas of the space within the church (i.e., narthex, nave, and altar) and implies a specific orientation: churches are built to face east, and all religious rites are oriented toward the sanctuary (Gschwandtner 2019, p. 60). All spaces and objects within are arranged to create a specific ‘reality’ in between the material and the spiritual.

A set of blind arches, two on the respective sides of the central niche, decorates the eastern portion of the room. Two alcoves adjacent to the central niche are framed by said arches; this portion of the church is accessed via two raised steps. The central portion of the ceiling houses a small dome (which is not visible from the outside) interrupted by the supporting metal beams of the roof structure, reminiscent of the building’s original design.

The church is lavishly decorated with a printed tile geometric motif which unfolds circa 1.5 m from the ground onto the wall and all the existing pillars. This decoration is characterized in the first smaller room by octagonal polygons with gray and black borders with an interlaced pattern of geometrical shapes and a dark green-black border around it (Figure 8). This aniconic pattern melds together to create a continuous succession of interlacing crosses. The same motif also defines the pillars in the larger room. However, the scale of colors is different, and the use of gray, white and gold prevails. The gold color is also used to define the geometry of the arches from the height of the tiled decoration. The entire perimeter of the church (namely the external walls and the ones adjacent to the lay house) is instead dressed with a simpler ceramic tiling outlined by gray rectangles within black borders. This black and white decoration is also present on the floor, which displays a geometrical pattern of white squares inside black borders.

Figure 8.

A 3D model of the church space looking towards the altar.

The digital twin of the Romanian house of worship of Lunghezza was created during our site visit to the church (16 November 2022). Before scanning, we ensured that all lights were turned on, that mirrors were covered and that the entrance door was kept open. Using an iPhone iOS 16.1.1, we took eight scans of the interior of the church space using the 360° camera feature. The new iPhone also features Lidar sensors which enable the scan to have a single rotation with the simple scan feature turned on. This creates a more accurate scan, and therefore measurements inside the 3D model can be taken with greater precision (Figure 8). Given that the ceilings were not extremely high, we opted for this scan typology instead of the Complete Scan method, which uses two 360° full rotations (2-rings) to capture the space. This would have been advised if there were details in the roof and if the height was superior to 5 m. We used the Matterport Axis 3D system to create a more stable scan of the surroundings and mimic the use of a Tripod. The 3D structure was synthesized using Matterport’s Cortex AI, giving the model depth, height and width. Finally, we used the Matterport measurement tool to identify and measure landmark features like doorways, windows, ceiling heights, length and width of the church plan. With the Mattertag feature, we highlighted points of interest (e.g., Icon of the Virgin Mary) to illustrate how the model can be enriched with semantic data.

8. Conclusions

As we envisaged in the Introduction, the Lunghezza case helps us to focus empirically on the category of ‘shared religious place’ since it is a place that, from being secular through a process of spiritual conversion but also of material furnishings, has become religious. It is the religious place of reference for the activities of the Orthodox group living in Lunghezza and nearby, which is necessary for the spiritual needs expressed by its members. The community finds itself, meets and binds itself to the religious dimension through the religious and social activities performed there. The material and spatial approach help to focus on the empirical experience of people who attend this place, which is considered a church, but at the same time, keeps the features of a secular place; in this sense, it is a diachronic shared religious place.

This diachronic sharing results in long-term survival, despite changes in use, internal and external modifications, and conversion interventions; one can therefore speak of a religious resilience of this place that is guaranteed by its camouflage between recognition and non-recognition, the visible and the invisible. Thus, we are dealing with a camouflaged religious place since the current parish residence does not have its own house number; the parish address number (n. 195)—posted on the Romanian Orthodox Diocese of Italy site11—is that of the Blendea family house and of the agricultural company to which the parish pays rent, whose entrance is the first one from the main street. From the outside, the building looks more like an agricultural warehouse than a place of worship. The only visible signs of a house of worship in that place are a small cross on top of the building and the iron gates, on which a cross and the words “Chiesa Cristiana Ortodossa” (Orthodox Christian Church) are engraved. The uncertainty around its future also derives from the fact that this place of worship has never been consecrated but only blessed by Fr. Benedict. According to him, the main reason for not being consecrated is that the parish is not the owner of the building, and it is not known for sure what will be the destination of the building after the end of the contract.

Moreover, in this case, we can also see an instance of both legal and opportunistic camouflage. The place is not registered as a church with the city hall of Lunghezza but as an agricultural farm. We deduced from the interview with the parish priest that they have never offered to help the Romanian parish community in Lunghezza with a place of worship or with land on which to build a church. Any relationship is now regarded with utmost suspicion for fear of being prevented from functioning as a place of worship. Therefore, according to the parish priest, the less the local authorities know about the final destination of this ‘agricultural’ site, the better for the parish.

The specially created mapping and the specific analysis of the Lunghezza case also reveal the complicated material and legal situation of the Romanian Orthodox parishes on the territory of the Metropolitan City of Rome, forced to find different solutions to have a place of worship. This condition mirrors what happens on a national scale. Adapting to concrete realities has led to architectural forms of resilience, ranging from Catholic buildings to garages, residential or commercial basements, warehouses, and stables converted into Orthodox houses of worship. This silent resilience and opportunistic camouflage are also reflected in its architectural forms. The external shell of the church maintains nothing of its interior furnishing: even the dome that dominates the central portion of the church is cleverly concealed inside the roof structure. Through the onsite digitisation of the building structures, we were able to recover volumetric data, plans, elevations, and sections, which otherwise would not have been readily available. This fostered a deeper understanding of religious space and of its transformation from a secular to a religious place of worship. The interior furnishings reveal nothing of its ambiguity except for the water trough aptly hidden under the new floor ceramic tiling. The outer and inner shells of the church come together in one tiny structural detail of the roofing, namely the iron beam inside the circumference of the dome. All in all, the Romanian parish in Lunghezza underscores the potential of studying the secondary, lesser-known sites as they reveal innovative methodological practices and hopefully new agendas for research.

The resilience of the place also consists in the resilience of the priest and the community that runs that place: it is, in fact, a group of believers, a minority and minoritised compared to a Catholic Christian majority, who have migrated from one place to another following the priest and the church project implemented and eventually realized by the institution. It is a resilient community despite being one of the youngest groups of Orthodoxies in Italy (Guglielmi 2022; Giorda 2023), despite the lack of legal recognition, despite the discrimination often accorded to Romanians in Italy (Cingolani 2008), and despite the precarious conditions in which they have been able to structure their presence and missions over the years.

On a final note, we wish to focus these conclusions on the methodological advantage acquired in the course of this study, subjecting its validity to the scrutiny of possible future research. The experimental and innovative approach lies in the strong plurality of disciplines utilized to observe the research object in question, adapting techniques and contaminating approaches. This modality is possible only within the framework of a team. This will hopefully lead to holistic and effective interdisciplinary research protocols in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; methodology, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; software, A.F. and S.O.; validation, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; formal analysis, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; investigation, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; resources, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; writing—review and editing, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; visualization, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O.; supervision, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O. Project administration, I.C., A.F., M.C.G., and S.O. Funding acquisition, no external funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The ShaRP LAB (Sharing Religious Places) is an international network of scholars interested in inter-religious interaction, devoting special attention to its spatial dynamics. It is, by definition, a multi-disciplinary network, as it brings together historians of religions, geographers, art historians, Islamicists, theologians and anthropologists, among others. |

| 2 | Hayim Pinson, Q&A With Matt Bell: How Matterport Started Capturing The Real Estate Market In VR, 9/11/16. https://uploadvr.com/matterport-matt-bell/. When the first Oculus DK1 (Developer Kit 1—the first iteration of the Oculus headset) came out, the founders realised that they had created the perfect software to bring real spaces into VR. (Accessed on 29 November 2022). |

| 3 | About Us, Matterport. https://matterport.com/about-us (Accessed on 29 November 2022). |

| 4 | Capture on your terms, Matterport. https://matterport.com/cameras (Accessed on 29 November 2022). |

| 5 | There is an ongoing debate which we do not wish to cover in this article on what virtual reality is. We have therefore opted for the most widespread definition of VR, namely: virtual reality is a simulated experience that employs pose tracking and 3D near-eye displays to give the user an immersive feel of a virtual world. Source: Virtual Reality, Wikipedia: The free encyclopaedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtual_reality (Accessed on 29 November 2022). |

| 6 | See: Stranieri residenti al 1 gennaio, http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCIS_POPSTRCIT1 (Accessed on 23 November 2022). |

| 7 | See: https://episcopia-italiei.it/index.php/ro/parohii-filii-si-paraclise (Accessed on 23 November 2022). |

| 8 | The organisation of the four deaneries in Latium does not correspond to the municipal administrative boundaries of Roma Capitale or to those of the municipalities of the metropolitan city. For further information, see the interactive online map of the organisation of the Romanian Orthodox Diocese in Italy: https://episcopia-italiei.it/index.php/ro/2-uncategorised/7382-mappa (Accessed on 28 November 2022). |

| 9 | Rome XVI is in the process of formation and currently has no permanent place of worship. |

| 10 | See: https://episcopia-italiei.it/index.php/ro/parohii-filii-si-paraclise/108-roma-nord-prima-porta (Accessed on 28 November 2022). |

| 11 | https://episcopia-italiei.it/index.php/ro/parohii-filii-si-paraclise/2831-lunghezza (Accessed on 25 November 2022). |

References

- Agnew, John. 2005. Space: Place. In Spaces of Geographical Thought: Deconstructing Human Geography’s Binaries. Edited by Paul Cloke and Ron Johnston. London: SAGE, pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Biddington, Terry. 2021. Multifaith Spaces. History Development, Design and Practice. London: Hachette. [Google Scholar]

- Bossi, Luca. 2018. La ricerca qualitativa. Sfide, limiti e opportunità per lo studio della diversità religiosa nello spazio urbano. In Roma città plurale. Le religioni, il territorio, le ricerche. Edited by Carmelo Russo and Alessandro Saggioro. Roma: Bulzoni, pp. 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bossi, Luca, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2021. The “Casa delle religioni” of Turin: A Multi-Level Project Between Religious and Secular. In Geographies of Encounter: The Making and Unmaking of Multi-Religious Spaces. Edited by Marian Burchardt and Maria Chiara Giorda. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 205–29. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, Marian. 2021. Multi-Religious Places by Design: Space, Materiality, and Media in Berlin’s House of One. In Geography of Encounters: The Making and Unmaking Spaces. Edited by Marian Burchardt and Maria Chiara Giorda. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 231–52. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, Marian, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2021. Geographies of Encounter: The Making and Unmaking of Multi-Religious Spaces—An Introduction. In Geographies of Encounter: The Making and Unmaking of Multi-Religious Spaces. Edited by Marian Burchardt and Maria Chiara Giorda. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani, Pietro. 2008. Romeni d’Italia: Migrazioni, vita quotidiana e legami transnazionali. Bologna: Il Mulino and Ricerca. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke, Paul, and Ron Johnston. 2005. Deconstructing human geography’s binaries. In Spaces of Geographical Thought: Deconstructing Human Geography’s Binaries. Edited by Paul Cloke and Ron Johnston. London: SAGE, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cozma, Ioan. 2021. The Interreligious Complex at Vulcana-Băi in Romania: A Multi-Religious Place Between Idealism and Pragmatism. In Geography of Encounters: The Making and Unmaking Spaces. Edited by Marian Burchardt and Maria Chiara Giorda. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- Cozma, Ioan, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2020. Sostituire, condividere, costruire: Le parrocchie ortodosse romene nel tortuoso cammino del riconoscimento. Religione e Società 35: 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cozma, Ioan, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2021. Diaspora ortodoxă română în Italia: Strategii și dinamici în crearea și folosirea lăcașurilor de cult. Altarul Reintregirii 3: 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozma, Ioan, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2022. Luoghi di culto della Chiesa ortodossa romena in Italia: Dinamiche di insediamento. In Le Chiese romene in Italia. Percorsi, pratiche e identità. Edited by Marco Guglielmi. Roma: Carocci editore & Biblioteca di testi e studi, pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Della Dora, Veronica. 2018. Infrasecular geographies: Making, unmaking and remaking sacred space. Progress in Human Geography 42: 44–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, Angelica. 2022. Digital Humanities in the Study of Multifaith Prayer Rooms in Airports: Theoretical aspects and a case study. Historia Religionum 14: 143–55. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2019a. Geografia delle religioni. In Manuale di Scienze della religione. Edited by G. Filoramo, M. C. Giorda and N. Spineto. Brescia: Morcelliana Scholé, pp. 201–22. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2019b. Monaci e monache presso le sedi vescovili. Alcuni casi di convivenza nel monachesimo ortodosso romeno. Studi e materiali di Storia delle Religioni 85: 244–69. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2020. Territori, Spazi e Luoghi Religiosi/Territories, Spaces and Religious Places. Metamorfosi, Quaderni di Architettura 8: 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara. 2022. Sharing Space Beyond Dichotomies: A Geo-History of Italian Religious Places. In Religion and Urbanity Online. Edited by Susanne Rau and Jörg Rüpke. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara Giorda. 2023. La chiesa ortodossa romena in Italia. Per una geografia storico-religiosa. Roma: Viella. [Google Scholar]

- Giorda, Maria Chiara, and Andrea Longhi. 2019. Religioni e spazi ibridi nella città contemporanea: Profili di metodo e di storiografia. Atti e Rassegna Tecnica della Società degli Ingegneri e degli Architetti in Torino 73: 108–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gschwandtner, Christina M. 2019. Welcoming Finitude: Toward a Phenomenology of Orthodox Liturgy. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi, Marco. 2022. The Romanian Orthodox Diaspora in Italy: Eastern Orthodoxy in a Western European Country. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hazard, Sonia. 2013. The Material Turn in the Study of Religion. Religion and Society: Advances in Research 4: 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervieu-Léger, Danièle. 1993. La Religion Pour Mémoire. Paris: Éditions du Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Houtman, Dick, and Birgit Meyer, eds. 2012. Things: Religion and the Question of Materiality. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, Tim, and Joanne McKenzie. 2017. Materiality and the Study of Religion: The Stuff of the Sacred. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2010a. Religion, Space, and Place. The Spatial Turn in Research on Religion. Religion and Society: Advances in Research 1: 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, Kim. 2010b. Geography, Space and the Sacred. In The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. Edited by John Hinnells. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 476–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Lily. 2001. Mapping ‘New’ Geographies of Religion: Politics and Poetics in Modernity. Progress in Human Geography 25: 211–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Lily. 2010. Global Shifts, Theoretical Shifts: Changing Geographies of Religion. Progress in Human Geography 34: 755–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, Mei-Po. 2008. From oral histories to visual narratives: Re-presenting the post-September 11 experiences of the Muslim women in the USA. Social & Cultural Geography 9: 653–69. [Google Scholar]

- Macchi Jánica, Giancarlo. 2019. GIS, Critical GIS e storia della cartografia. Geotema 58: 179–87. [Google Scholar]

- Marinis, Vasileios. 2013. Architecture and Ritual in the Churches of Constantinople: Ninth to Fifteen Centuries. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink, Allard M.J., Hans de Brouwer, Chris M. Mannaerts, and Carlos R. Valenzuela. 1994. Introduction to the Use of Geographic Information Systems for Practical Hydrology: IHP—IV M 2.3. Enschede: International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation, ITC Publication, vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David. 2021. The Thing about Religion. An Introduction to the Material Study of Religions. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Omenetto, Silvia. 2019. Geographic Information Systems and Geography of Religions: An International Review of Research. Historia Religionum 11: 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Omenetto, Silvia, and Maria Chiara Giorda. 2021. Seppur informali: L’invisibilità urbana dei gruppi religiosi. Un’ipotesi esplorativa per un centro culturale Sikh a Roma. Archivio di Studi Urbani e Regionali 132: 177–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, H. Denisson. 1988. The Unique Qualities of a Geographic Information System: A Commentary. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 54: 1547–49. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Douglas A., and Roger F. Tomlinson. 1992. Accessing Costs and Benefits of Geographical Information Systems: Methodological and Implementation Issues. International Journal of Geographical Information Systems 6: 247–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Terence R., Sudhakar Menon, Jeffrey L. Star, and John E. Estes. 1987. Requirements and principles for the implementation and construction of large-scale geographic information systems. International Journal of Geographical Information Systems 1: 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, Roger F., Hugh W. Calkins, and Duane F. Marble. 1976. Computer Handling of Geographical Data: An Examination of Selected Geographic Information Systems. Paris: The Unesco Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).