How Can Islamic Primary Schools Contribute to Social Integration?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Defining ‘Social Integration’

3. Results

3.1. Diversity within the School Population Leading to Internal Dialogues

3.2. Examples of Internal Dialogues: Music Education and the Dutch King’s Games

During one of the performances [in an occasion where several Islamic schools were united] a pupil picked up an electric guitar and sat down to play it. Some adults then stood up and walked away. They were like: this is not okay. […] We have now said that no musical instruments should be used during similar occasions. Otherwise, we would be excluding certain people. […] Also, for example, with photos at the national Islamic knowledge quiz: we have a location that also has a balcony, so people who don’t want to be in a picture can stand on the balcony for a while.(board director, convert, born in The Netherlands)

Principal: Parents have difficulty with the fact that the King’s Games are organized because of a birthday. That applies to some, maybe half [of our parents]. And other [parents] have a hard time with it because the celebration may seem royalist. But you are in the Netherlands. […] These parents object because they say that the only one you must answer to is Allah. […] As a principal I respect their point of view. I took the point on celebrating the king’s birthday more serious because that is a point of view that half of the [Islamic] movements recognize. I [then] have to discuss that with the identity committee, regardless of what I think about it myself.

Interviewer: How many parents have difficulty with the King’s Games?

Principal: 2 out of 250, and trouble with birthdays: 10 out of 250. But within the identity committee, which represents all schools, it’s really been 50/50.(principal, convert, not born in The Netherlands)

We think it is very important to celebrate the King’s Games together with the rest of the country and to stimulate healthy behaviour, with the school breakfast and the exercise like on a Sports Day. The King’s Games are not about the king’s birthday and a birthday celebration is not the intention with the King’s Games. We really have to emphasize that to the parents, that you do not celebrate the king’s birthday. And also, for example, that starting the day with a dance to music is not a disco but a joint opening that is designed in the same way in all schools throughout the country.(principal, Muslim, not born in The Netherlands)

3.3. Increasing Influence of the Dutch Context

3.4. Using the Sense of Safety to Consiously Address Sensitive Topics

We are very much aware of the fact that the children will soon be working and studying in Dutch society. We feel that we must prepare them well for this, that everything we do should be dominated by the thought that they will soon be part of and must maintain themselves in society. [So, we tell the children:] ‘When you start applying for a job, you know that in the Netherlands you have to shake hands, you know that you have to look the person in the eye and start a conversation’.(principal, convert, born in The Netherlands)

3.5. Sensitive Topics at Non-Islamic Primary Schools

4. Methods

5. Conclusions

6. Suggestions for Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Faruqi, Lois Lamya. 1989. The shari’ah on music and musicians. In Islamic Thought and Culture. Herndon: International Institute of Islamic Thought, pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Banning, Bill. 2021. Polyfoon katholiek! Diepgaande dialoog op de scholen in lijn van katholieke visie. Nederlandse Katholieke Schoolraad. Available online: https://www.nksr.nl/polyfoon-katholiek/ (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Bedford, Ian. 2001. The Interdiction of Music in Islam. Australian Journal of Anthropology 12: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beemsterboer, Marietje. 2014. Heemskerkers Tegen Komst Islamitische School? Leiden Islam Blog. Available online: http://www.leiden-islamblog.nl/articles/heemskerkers-tegen-komst-islamitische-school (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Beemsterboer, Marietje. 2018. Islamitisch basisonderwijs in Nederland. Almere: Parthenon. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Derrick A. 1980. Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma. Harvard Law Review 93: 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Derrick A. 2005. The Unintended Lessons in Brown v. Board of Education. NYLS Law Review 4: 1053–67. [Google Scholar]

- Boersema, Wendelmoed. 2020. Bijzondere school kan straks geen kind weren. Trouw, November 13. [Google Scholar]

- Bron, Jeroen, Sigrid Loenen, Martha Haverkamp, and Eddie van Vliet. 2015. Seksualiteit en seksuele diversiteit in de kerndoelen. Een leerplanvoorstel en voorbeeldlesmateriaal. Enschede: Stichting Leerplan Ontwikkeling. [Google Scholar]

- Bucx, Freek, and Simone De Roos. 2015. Opvoeden in niet-westerse migrantengezinnen: Een terugblik en verkenning. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau. [Google Scholar]

- Budak, Bahaeddin. 2021. Waarom stichten jullie niet een eigen school?: Religieuze identiteitsontwikkeling van islamitische basisscholen 1988–2013. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij IUA. [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, Frank J. 2009. Muslims in the Netherlands: Social and Political Developments after 9/11. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35: 421–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Simon, Deborah Wilson, and Ruth Lupton. 2005. Parallel Lives? Ethnic Segregation in Schools and Neighbourhoods. Urban Studies 42: 1027–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Simon, Ellen Greaves, Anna Vignoles, and Deborah Wilson. 2011. Parental choice of primary school in England: What types of school do different types of family really have available to them? Policy Studies 32: 531–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

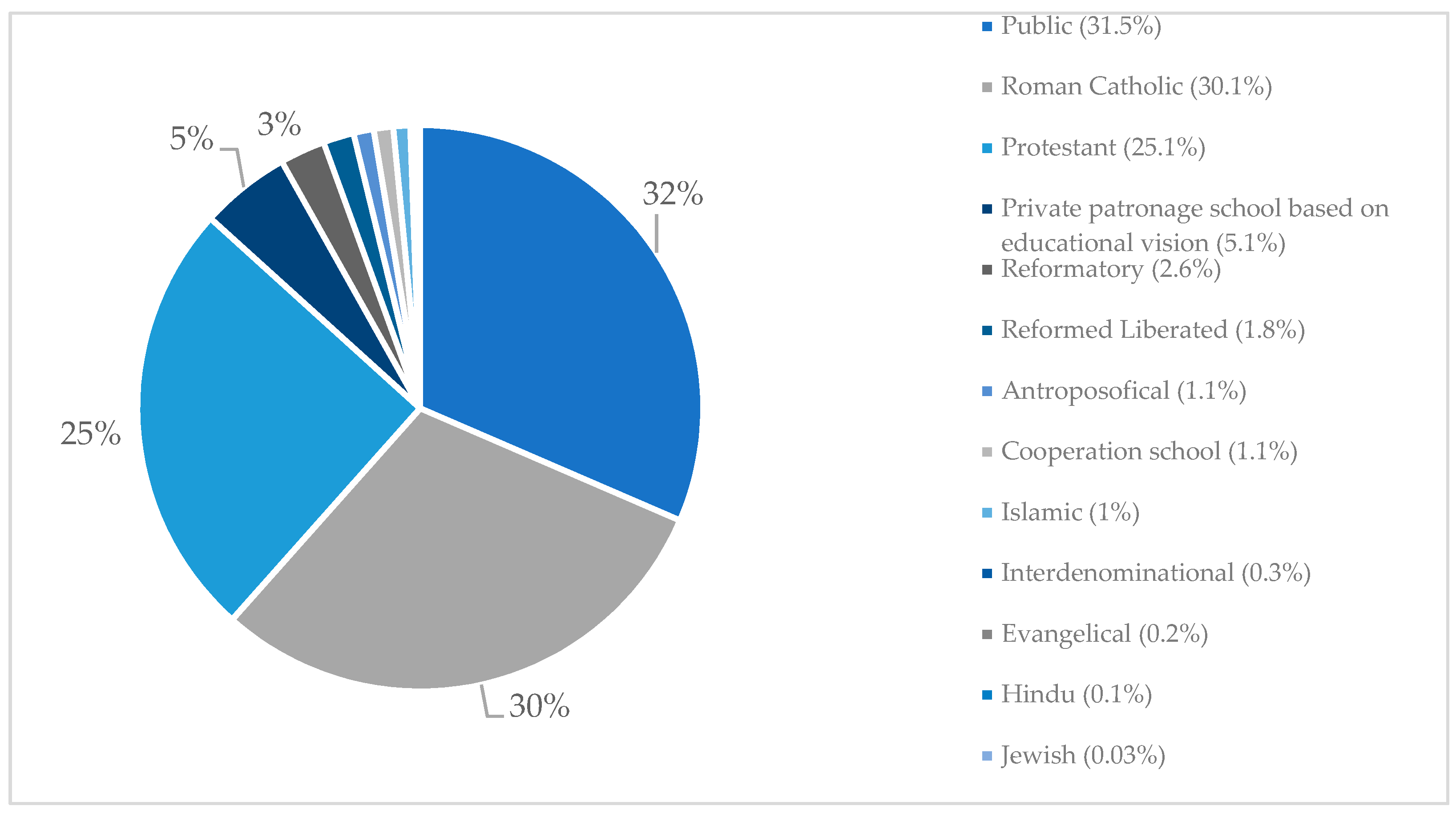

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2021. Onderwijsinstellingen; grootte, soort, levensbeschouwelijke grondslag. The Hague: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/03753/table?fromstatweb (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Chenoweth, Karin. 2007. It’s Being Done: Academic Success in Unexpected Schools. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Darity, William. 2005. Stratification economics: The role of intergroup inequality. Journal of Economics and Finance 29: 144–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, Martijn. 2008. Zoeken naar een ‘zuivere’ islam. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker. [Google Scholar]

- Dienst Uitvoering Onderwijs. 2022. Hoofdvestigingen basisonderwijs. Den Haag: Ministerie van Onderwijs. Available online: https://duo.nl/open_onderwijsdata/primair-onderwijs/scholen-en-adressen/hoofdvestigingen-basisonderwijs.jsp (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Dijkstra, Anne Bert. 2012. Sociale opbrengsten van onderwijs (Oratiereeks). Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Distelbrink, Marjolein, and Trees Pels. 2012. Pedagogische ondersteuning en de spil-functie van het CJG. Pedagogiek 32: 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbie, Will, and Roland G. Fryer. 2011. Are High-Quality Schools Enough to Increase Achievement Among the Poor? Evidence from the Harlem Children’s Zone. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3: 158–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, Geert. 1997. Islamic Primary Schools in the Netherlands: The Pupils’ Achievement Levels, Behaviour and Attitudes and Their Parents’ Cultural Backgrounds. The Netherlands’ Journal of Social Sciences 33: 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, Geert, and Jeff Bezemer. 1999. Islamitisch Basisonderwijs. Schipperen tussen identiteit en kwaliteit. Nijmegen: ITS. [Google Scholar]

- Driessen, Geert, Orhan Agirdag, and Michael S. Merry. 2016. The gross and net effects of primary school denomination on pupil performance. Educational Review 68: 466–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dwyer, James G. 2001. Religious Schools v. Children’s Rights. New York: Cornell University Press. Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.7591/9781501723834/html (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Eldering, Lotty. 2006. Cultuur en opvoeding: Interculturele pedagogiek vanuit ecologisch perspectief. Rotterdam: Lemniscaat. [Google Scholar]

- Enthoven, Mascha, Colleen Clinton, and Marietje Beemsterboer. 2021. Kansen in context: Contextbewust onderwijs en onderzoekend vermogen om als leraar pedagogisch betekenis te kunnen geven aan sociologische analyses van kansenongelijkheid. Tijdschrift Voor Lerarenopleiders 4: 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Entzinger, Han, and Edith Dourelijn. 2008. De lat steeds hoger. Assen: Van Gorcum. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, M. 2009. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaikhorst, Lisa, Jeffrey Post, Virginie März, and Inti Soeterik. 2020. Teacher preparation for urban teaching: A multiple case study of three primary teacher education programmes. European Journal of Teacher Education 43: 301–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, Terri E. 2007. Immigrant Integration in Europe: Empirical Research. Annual Review of Political Science 10: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goffman, Erving. 2018. Stigma: Notities over de omgang met een geschonden identiteit. Utrecht: Erven J. Bijleveld. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, J. Mark. 1997. Muslims and sex education. Journal of Moral Education 3: 317–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, Michael. 2004. The problem with faith schools: A reply to my critics. Theory and Research in Education 2: 343–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inspectie van het Onderwijs. 2018. Technisch rapportage onderwijskansen en segregatie. De staat van het onderwijs 2016/2017. The Hague: Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap. [Google Scholar]

- Inspectie van het Onderwijs. 2020. Themaonderzoek burgerschapsonderwijs en het omgaan met verschil in morele opvattingen. The Hague: Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap. [Google Scholar]

- Khaddari, Raounak, and Bas Soetenhorst. 2021. Amsterdam: Nieuwe scholen versterken segregatie en lerarentekort. Algemeen Dagblad, November 4. [Google Scholar]

- Klarenbeek, Lea M. 2021. Reconceptualising ‘integration as a two-way process’. Migration Studies 9: 902–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinig, John. 1982. Philosophical Issues in Education. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kunst, Jonas R., Hajra Tajamal, David L. Sam, and Pål Ulleberg. 2012. Coping with Islamophobia: The effects of religious stigma on Muslim minorities’ identity formation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36: 518–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmullen, Ian. 2016. Faith in Schools? Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maussen, Marcel, and Floris Vermeulen. 2015. Liberal equality and toleration for conservative religious minorities. Decreasing opportunities for religious schools in the Netherlands? Comparative Education 51: 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael. S. 2007. Should the State Fund Religious Schools? Journal of Applied Philosophy 24: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael S. 2013. Equality, Citizenship, and Segregation. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael S. 2018. Indoctrination, Islamic schools, and the broader scope of harm. Theory and Research in Education 2: 162–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael S. 2020. Educational Justice: Liberal Ideals, Persistent Inequality, and the Constructive Uses of Critique. Berlin: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Michael S., and Marcel Maussen. 2018. Islamitische scholen en indoctrinatie. Tijdschrift Voor Religie, Recht En Beleid 9: 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metselaar, Toine. 2005. Een zwarte of een witte school? Een onderzoek naar de opvattingen van ouders over etniciteit bij de keuze van een basisschool voor hun kind (Doctoraalscriptie). Tilburg: Universiteit van Tilburg. [Google Scholar]

- Neeleman, Annemarie. 2019. The scope of school autonomy in practice: An empirically based classification of school interventions. Journal of Educational Change 20: 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2011. School autonomy and accountability: Are they related to student performance? In PISA in Focus. Paris: OECD, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ogretici, Yusuf. 2021. Bridging Theory, Experiment, and Implications: Knowledge and Emotion-Based Musical Practices for Religious Education. Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Onderwijsraad. 2021. Grenzen stellen, ruimte laten. Artikel 23 Grondwet in het licht van de democratische rechtsstaat. Onderwijsraad. Available online: https://www.onderwijsraad.nl/binaries/onderwijsraad/documenten/adviezen/2021/10/05/grenzen-stellen-ruimte-laten/OWR+Grenzen+stellen%2C+ruimte+laten.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Otterbeck, Jonas. 2004. Music as a useless activity: Conservative interpretations of music in Islam. In Shoot the Singer! Music Censorship Today. London: Zen Books Ltd., pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Otterbeck, Jonas, and Anders Ackfeldt. 2012. Music and Islam. Contemporary Islam 6: 227–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pels, Trees. 2000. De generatiekloof in allochtone gezinnen: Mythe of werkelijkheid? Pedagogiek 2: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pels, Trees. 2010. Oratie: Opvoeden in de multi-etnische stad. Pedagogiek 3: 211–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pels, Trees, M. Distelbrink, and Lisette Postma. 2009. Opvoeding in de Migratiecontext. Utrecht: Verwey-Jonker Instituut/NWO. [Google Scholar]

- Philipsen, Stefan. 2018. Meer ruimte voor nieuwe scholen? Tijdschrift Voor Religie, Recht En Beleid 9: 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld-van Wingerden, Marjoke, J. C. Sturm, and Siebren Miedema. 2003. Vrijheid van onderwijs en sociale cohesie in historisch perspectief. Pedagogiek 23: 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Hugo. 2019. Moslimscholen. Leidsch Dagblad, July 23. [Google Scholar]

- Shadid, Wasif A., and Pieter Sjoerd Van Koningsveld. 1992a. Islamic Primary Schools. In Islam in Dutch Society: Current Developments and Future Prospects. Kampen: Kok Pharos, pp. 107–23. [Google Scholar]

- Shadid, W. A., and P. S. Van Koningsveld. 1992b. Islamitische scholen. De verschillende scholen en hun achtergronden. Samenwijs 12: 227–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shadid, Wasif A., and Pieter Sjoerd Van Koningsveld. 1997. Moslims in Nederland. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum. [Google Scholar]

- Smeekes, Anouk, Maykel Verkuyten, and Edwin Poppe. 2011. Mobilizing opposition towards Muslim immigrants: National identification and the representation of national history: Representations of national history. British Journal of Social Psychology 50: 265–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, Frederik, Geert Driessen, and Jan Doesborgh. 2005. Opvattingen van allochtone ouders over onderwijs. Tussen wens en realiteit. Nijmegen: ITS Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, Frederik, Geert Driessen, Roderick Sluiter, and Mariël Brus. 2007. Ouders, scholen en diversiteit: Ouderbetrokkenheid en-participatie op scholen met veel en weinig achterstandsleerlingen. Nijmegen: ITS, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. [Google Scholar]

- Sözeri, Semiha. 2021. The Pedagogy of the Mosque: Portrayal, Practice, and Role in the Integration of Turkish-Dutch Children. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Stekelenburg, Richard. 2021. Beverwijk zegt nu officieel ‘nee’ tegen komst islamitische middelbare school. Noordhollands Dagblad, October 27. [Google Scholar]

- Strabac, Zan, and Ola Listhaug. 2008. Anti-Muslim prejudice in Europe: A multilevel analysis of survey data from 30 countries. Social Science Research 37: 268–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Broeke, Lara, Willem Bosveld, Marije Van de Kieft, Liesbeth Gerritsen, Cindy Koopman, Chantal Kuhnen, and Bart Eijken. 2004. Schoolkeuzemotieven. Onderzoek naar het schoolkeuzeproces van Amsterdamse ouders. Amsterdam: Gemeente Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Avest, K. H. (Ina), and Marjoke Rietveld-van Wingerden. 2017. Half a century of Islamic education in Dutch schools. British Journal of Religious Education 39: 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Laan, Nina. 2016. Dissonant voices. Islam-inspired Music in Morocco and the Politics of Religious Sentiments. Zutphen: CPI Koninklijke Wöhrmann. [Google Scholar]

- Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal. 2019. Memorie van toelichting 35352 nr. 3. Available online: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-35352-3.html (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Van Baars, Laura. 2016. Islamitische school krijgt geen deld van Dekker. Trouw, December 21. [Google Scholar]

- Van Baars, Laura. 2021. Nieuwe zorgen om het Haga, net nu het extra geld krijgt. Trouw, October 13. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Werfhorst, Herman G. 2019. Early Tracking and Social Inequality in Educational Attainment: Educational Reforms in 21 European Countries. American Journal of Education 126: 65–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gool, Rosa. 2017. Stop de indoctrinatie van kinderen, weg met de onderwijsvrijheid. De Volkskrant, September 24. [Google Scholar]

- Van Keulen, Anke, and Annemie Van Beurden. 2010. Van alles wat meenemen: Diversiteit in opvoedingsstijlen in Nederland. Bussum: Coutinho. [Google Scholar]

- Van Roosmalen, Marcel, dir. 2020. Schaf de vrijheid van onderwijs af, stop de indoctrinatie van kinderen. In BNN/VARA: De Druktemaker. Available online: https://www.bnnvara.nl/joop/artikelen/schaf-vrijheid-van-onderwijs-af-stop-de-indoctrinatie-van-kinderen (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Van Schie, Patrick. 2017. Particuliere ‘binnenkamer’ en openbaar klaslokaal. Nederlandse liberalen over religie in de politiek en het bijzonder onderwijs. Tijdschrift Voor Religie, Recht En Beleid 3: 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaste commissie voor Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap. 2020. Verslag voorbereidend onderzoek wetsvoorstel 35352 nr. 5. Available online: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-35352-5.html (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Verkuyten, Maykel. 2013. Justifying discrimination against Muslim immigrants: Out-group ideology and the five-step social identity model: Justifying discrimination. British Journal of Social Psychology 52: 345–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, Maykel, and Jochem Thijs. 2002. Racist victimization among children in The Netherlands: The effect of ethnic group and school. Ethnic and Racial Studies 2: 310–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, Fred. 2020. Lokale Westlandse partijen blijven zich verzetten tegen komst van islamitische school Yunus Emre. Algemeen Dagblad, July 9. [Google Scholar]

- Verstraelen, Fred. 2013. Fel debat islamitische school. De Limburger, June 13. [Google Scholar]

- Zuidhof, Martin. 2009. ‘Kinderen maken uitsluiting mee’. Trees Pels over opvoeden in de multi-etnische stad. Zorg En Welzijn 7/8: 1–4. Available online: https://www.zorgwelzijn.nl/hoogleraar-opvoeden-kinderen-maken-uitsluiting-mee-zwz014232w/ (accessed on 3 September 2022).

| Number (N = 75) | ||

| Group teacher | 39 |

| 4–8 year-old children | 20 | |

| 8–12 year-old children | 21 | |

| Principal | 17 | |

| Religion teacher | 12 | |

| Special needs coordinator | 5 | |

| Other | 5 | |

| 13 years | |

| 7 years | |

| Female | 47 |

| Male | 28 | |

| 41 years | |

| Muslim | 46 |

| Converted Muslim | 9 | |

| Christian | 15 | |

| Agnostic | 6 | |

| Other (including atheist/Hindu) | 8 | |

| The Netherlands | 47 |

| Morocco | 11 | |

| Turkey | 5 | |

| Suriname | 6 | |

| Other/unknown | 6 | |

| The Netherlands | 30 |

| Morocco | 16 | |

| Turkey | 18 | |

| Suriname | 6 | |

| Other/unknown | 5 |

| Background Characteristics | Group Teachers | N = 38 | Principals | N = 17 | Religion Teachers | N = 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 years | 19 years | 8 years | |||

| 7 years | 6 years | 8 years | |||

| Male | 6 | Male | 8 | Male | 11 |

| Female | 32 | Female | 9 | Female | 2 | |

| 38 years | 47 years | 45 years | |||

| Muslim | 17 | Muslim | 9 | Muslim | 13 |

| Converted Muslim | 4 | Converted Muslim | 3 | Converted Muslim | 1 | |

| Christian | 12 | Christian | 3 | Christian | ||

| Other | 9 | Other | 5 | Other | ||

| The Netherlands | 27 | The Netherlands | 12 | The Netherlands | 4 |

| Morocco | 5 | |||||

| Other | 11 | Other | 5 | Other | 4 | |

| The Netherlands | 19 | The Netherlands | 10 | The Netherlands | 1 |

| Morocco | 4 | Morocco | 8 | |||

| Turkey | 9 | |||||

| Suriname | 5 | |||||

| Other/unknown | 1 | Other/unknown | 7 | Other/unknown | 4 |

| Background Characteristics | Total Number of Islamic Schools at the Time of Fieldwork | N = 49 | Research Group | N = 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suburban area | 30 | Suburban area | 10 |

| Rural area | 19 | Rural area | 9 | |

| Small (<100) Medium (100–250) Large (>250) | 11 22 16 | Small (<100) Medium (100–250) Large (>250) | 4 7 8 |

| SIPO | 3 | SIPO | 1 |

| SIPOR | 4 | SIPOR | 1 | |

| SIMON | 11 | SIMON | 5 | |

| El Amal | 5 | El Amal | 1 | |

| El Amana | 5 | El Amana | 2 | |

| Noor | 4 | Noor | 0 | |

| 15 smaller school boards | 17 | 15 smaller school boards | 9 | |

| 1985–1990 1991–1995 | 11 18 | 1985–1990 1991–1995 | 4 6 |

| 1996–2000 | 1 | 1996–2000 | 1 | |

| 2001–2005 | 9 | 2001–2005 | 5 | |

| 2006–2010 | 3 | 2006–2010 | 1 | |

| 2011–2015 | 7 | 2011–2015 | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beemsterboer, M. How Can Islamic Primary Schools Contribute to Social Integration? Religions 2022, 13, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090849

Beemsterboer M. How Can Islamic Primary Schools Contribute to Social Integration? Religions. 2022; 13(9):849. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090849

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeemsterboer, Marietje. 2022. "How Can Islamic Primary Schools Contribute to Social Integration?" Religions 13, no. 9: 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090849

APA StyleBeemsterboer, M. (2022). How Can Islamic Primary Schools Contribute to Social Integration? Religions, 13(9), 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090849