Zen Philosophy of Mindfulness: Nen 念 according to Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō

Abstract

1. Introduction

アメリカのマインドフルネスはもともとは仏教のコンセプトであるサティ(パーリ語)由来するものだが,「現在の瞬間に対する,判断を入れない注意のスキル」としてあまりにも仏教の文脈から切り離され,世俗化・メソッド化されてしまったために,サティが本来持っていた広がりと深さが失われているように思われる.たとえばそれは「思い出す」という重要な働きや,戒や他の修行法との密接な関連性であり,主客二元を超えた無我行への深まりの方向性である.日本が今後マインドフルネス・ムーヴメントに貢献できるとすれば,あらためてマインドフルネスを仏教の中にもどしてとらえなおし,より広がりと深さを備えた新しいマインドフルネスとして更新していくことではないだろうか.

Mindfulness in the U.S. is derived originally from the Buddhist concept sati (Pāli). It seems that the width and the depth of sati have been lost because it got separated far away from the context of Buddhism when it was secularized and defined as “skill of paying attention to the very present moment non-judgmentally”. For example, that is the significant function of “recalling”, its close connections with precepts or other forms of training, or the attitude towards the depth of the state of no-self beyond the dichotomy of subject and object. If there is a way for Japan to contribute to the mindfulness movement from now on, it might be to put mindfulness back into Buddhism and then grasp it again and to update it as new mindfulness with further width and depth.

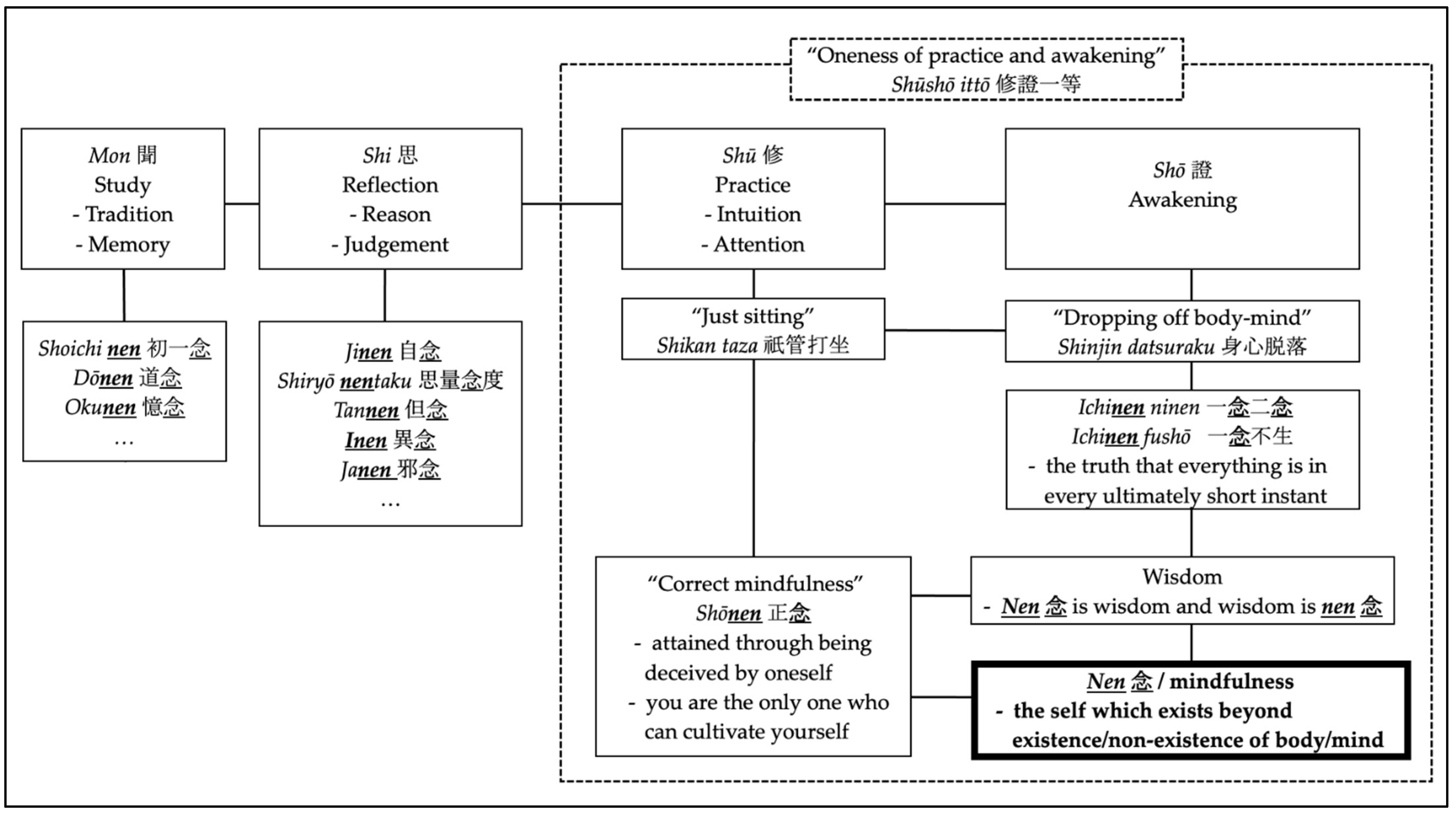

七者修智惠。起聞思修證爲智惠。3

The seventh means to awakening is attaining wisdom. Wisdom is the realization of “study” (mon 聞), “reflection” (shi 思), “practice” (shū 修), and “awakening” (shō 證).

2. Nen 念 in the Traditions of Japanese Buddhism after Smṛti and Nian 念

2.1. Nian 念 and Mindfulness

念: 常思也. 從心今聲.

Nian: Have in mind, constantly think of someone or something. Compiled from the heart-mind and the present.

念: 思也. 又姓西魏太傅念賢.

Nian: Think of, think. Also the pronunciation of the surname Xian.

2.2. Nen 念 in the Traditions of Japanese Buddhism

- Remembering. Memorizing. The function of memory. Functions of memorizing and keeping an object in mind. The mental function of memorizing and keeping something in mind. Recollection. Recalling and thinking back to the past.[P] sati, [S] smṛti, [S] smṛti, [S] ālambana-asaṃpramoṣa, [S] smaraṇa, [S] saṃ-√smṛ

- Focusing on something. One of the virtues.[P] sati

- Saying something into oneself (often without speaking out).[S] manasi-kāra, [P] samanāhāro hoti

- Conceiving.[P] so evaṃ pajānāti, [P] cetaso parivitakka, [S] atarkika, [P] dhammavicaya (one of satta bojjhaṅgā)

- Wisdom that is observing.

- Correcting one’s thoughts in mind.

- Function of memory as one of mahā-bhūmika dharma.[S] smṛti

- In Vijñānavāda, memory as one of five mental factors of vibhāvanā. Not losing or forgetting something acquired.[S] smṛti, [T] dran(pa)

- The function of intention.[P] cetanā

- Mind.[P] manas

- Feelings. Mind longing for something.[S] citta

- Delusion

- An ultimately short moment.[S] kṣaṇa

- Nenbutsu 念仏[S] buddhānusmṛti.

- Enduring.

- Secondary scriptures in Brahmanism, compared to [S] Śruti, the revealed texts.

3. Nen 念 in SBGZ, according to Each Step of the Threefold Wisdom

3.1. “Study” and Nen 念 in SBGZ: The Teachings and Traditions Buddhist Monks Should Keep in Mind

しるべし、佛法は初一念にも大意あり、究竟位にも大意あり。その大意は不得なり。發心修行取證はなきにあらず、不得なり。その大意は不知なり。修證は無にあらず、修證は有にあらず、不知なり、不得なり。またその大意は、不得不知なり。聖諦修證なきにあらず、不得不知なり。聖諦修證あるにあらず、不得不知なり

You should understand that the essence of Buddhism lies in the first thought of starting life as a Buddhist monk as well as the ultimate state of awakening. You cannot attain the essence. Although there exists (the steps of) this determination, practice, and awakening, you cannot attain the essence. The essence cannot be grasped. Practice-awakening is not nothingness; it is not existence, it cannot be grasped, and it cannot be attained. The essence cannot be grasped or attained. Although there exist Noble truths and practice-awakening, they cannot be grasped or attained. There do not exist Noble truths and practice-awakening, and they cannot be grasped or attained.

(…) しばらく雲遊萍寄して、まさに先哲の風をきこえむとす。ただし、おのずから名利にかかはらず、道念をさきとせん眞實の參學あらむか。いたづらに邪師にまどはされて、みだりに正解をおほひ、むなしく自狂にゑうて、ひさしく迷鄕にしづまん。(…)これをあはれむゆゑに、まのあたり大宋國にして禪林の風規を見聞し、知識の玄旨を稟持せしを、しるしあつめて、參學閑道の人にのこして、佛家の正法をしらしめんとす。これ眞訣ならむかも。

(…) I was aiming to leave myself free from everything like a drifting cloud and just listen to the winds of the legacy of ancient wisdom. However, even a person who, regardless of fame or profit, aspires after a genuine study based on the mind to pursue the path to awakening is to be taught incorrectly by a wrong mentor, to lose correct interpretations of Buddhism teachings, to be self-satisfied in vain, and to be lost for a long time. (…) As I feel pity for this, I gather and articulate the atmosphere and rules of the Zen tradition that I saw and listened to in the Song dynasty and the essence of knowledge that I was given and have maintained, in order to leave these for the people studying Buddhism as renouncers and let them grasp the true Dharma of Buddhism. I believe these must be the genuine essence of Buddhism.

釈迦牟尼佛、告普賢菩薩言、若有受持読誦正憶念修習書写是法華経者、当知是人則見釈迦牟尼仏如従仏口聞此経典10。

Śākyamuni Buddha told Samantabhadra “If one receives and maintains this Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra, reads it aloud, remembers it in mind all the time correctly, practices it, and transcripts it, you should just know that this person then sees Buddha just as if listening to this Sūtra from the mouth of Buddha”.

3.2. “Reflection” and Nen 念 in SBGZ: Mental Traps to Be Avoided

父母固止之。遂終日不食。乃許其在家出家、號僧伽難提、復命沙門禪利多、爲之師。積十九載、未甞退倦。尊者毎自念言、身居王宮、胡爲出家。11

His parents held back this (his becoming a Buddhist monk) firmly. Then, he did not eat anything all day long. Therefore, they permitted him to become a Buddhist monk at their home. They named him Samghanandi, and ordered the Śramaṇa Dhyanalita to become his mentor. Nineteen years after, he did not get fed up. He always reflected on himself and said to himself, “I am living in a royal palace. How can I regard this as a renouncer’s life?”

又、讀經念佛等のつとめにうるところの功德を、なんぢしるやいなや。ただしたをうごかし、こゑをあぐるを、佛事功德とおもへる、いとはかなし。佛法に擬するにうたたとほく、いよいよはるかなり。又、經書をひらくことは、ほとけ頓漸修行の儀則ををしへおけるを、あきらめしり、敎のごとく修行すれば、かならず證をとらしめむとなり。いたづらに思量念度をつひやして、菩提をうる功德に擬せんとにはあらぬなり。

Also, do you know or not what the virtue you can attain is through devoting yourself to reading sūtra aloud and remembering Buddha. It is very superficial to regard just moving your tongue and reading sūtra aloud as Buddhis practice and to believe you can attain virtue through this. These are very far from the essence of Buddhism. Also, studying sūtra is clarifying and grasping the teachings of Buddha about rules towards both sudden awakening and gradual awakening, and if you practice just based on the teachings you will surely attain awakening. It is not a correct way to regard thinking and assuming various things at the mercy of your mental functions in vain as the virtue leading to attaining bodhi.

しばらく功夫すべし、この四生衆類のなかに、生はありて死なきものあるべしや。又、死のみ單傳にして、生を單傳せざるありや。單生單死の類の有無、かならず參學すべし。わづかに無生の言句をききてあきらむることなく、身心の功夫をさしおくがごとくするものあり。これ愚鈍のはなはだしきなり。(…)いたづらに水草の但念なるがゆゑなり。

You should contemplate for a while whether there is even just one that has birth but not death among these four types of living things (all types of living things), or, whether there is one that you hear only about its death but do not about its birth. You have to study whether this is the case or not, for sure. Some people do not clarify the significance of teachings about no-birth or pause digging into this question through exerting their body and mind. This is such a stupid case. (…). This is because they are just thinking about their waterweeds in vain.

いまの人は、實をもとむることまれなるによりて、身に行なく、こころにさとりなくとも、他人のほむることありて、行解相應せりといはん人をもとむるがごとし。迷中又迷、すなはちこれなり。この邪念、すみやかに抛捨すべし。

Since it is rare for people today to seek for the truth, it is as if they want to be praised as a person whose practice and understandings correspond entirely, even if they do not practice physically or attain awakening in their mind. That is, they are lost within delusion. You should throw away this disturbing thought.

曾聞、有人自謂成佛。待天不曉、謂爲魔障。曉已不見梵王請說、自知非佛。自謂是阿羅漢。又被他人罵之、心生異念、自知非是阿羅漢。乃謂是第三果也。又見女人起欲想、知非聖人。此亦良由知敎相故、乃如是也。それ佛法をしれるは、かくのごとくみづからが非を覺知し、はやくそのあやまりをなげすつ。しらざるともがらは、一生むなしく愚蒙のなかにあり。生より生を受くるも、またかくのごとくなるべ し。

I have heard one story. A person thought he had become Buddha. But the sun did not rise, although he waited for a long time. Then he knew this was due to a devil. Brahma did not appear to pray for preaching at dawn, and he thought he had not become Buddha but Arhat. Then his mind produced a wrong thought when he was rebuked, and he knew he had not become Arhat. Then he thought his state was the third one. However, when he was aroused by seeing a woman, he knew he was not a saint. He realized it by himself as he knew the teachings of Buddha. That is, attaining Dharma is perceiving one’s own drawbacks by oneself like this and throw them away promptly. Those who do not know (the teachings of Buddha) would be in ignorance for a lifetime in vain. Even after receiving birth after birth, life would be just like this again.

3.3. “Practice” and Nen 念 in SBGZ: Towards Awakening through Zazen

宗門の正傳にいはく、この單傳正直の佛法は、最上のなかに最上なり、參見知識のはじめより、さらに燒香禮拜念佛修懺看經をもちゐず、ただし打坐して身心脫落することをえよ。

The correct tradition of our school says: “This Dharma, succeeded directly and correctly since Buddha, is the best among the best. Immediately after grasping the true knowledge, do not practice thurification (burning incense), praying, remembering Buddha, confessing, or reading sūtra. Just do zazen and reach the state of dropping off body-mind”.

一念二念は一山河大地なり、二山河大地なり。山河大地等、これ有無にあらざれば大小にあらず、得不得にあらず、識不識にあらず、通不通にあらず、悟不悟に變ぜず。

Moment by moment, there exists one mountain-river-earth and two (or all) mountains-rivers-earths. Mountains-rivers-earths-others are not existence or nothingness, big or small, attained or not, grasped or not, or connected or not. This would not change even before and after awakening.

念念一一なり。これはかならず不生なり、これ全體全現なり。このゆゑに一念不生と道取す。

Every single moment is one thing. Every single moment is necessarily eternal and absolute, and everything appears entirely in every single moment. Therefore, I have grasped the truth that an ultimately short instant is unborn.

4. Nen 念, “Oneness of Practice and Awakening”, “Just Sitting”, and “Dropping off Body-Mind”

それ、修證は一つにあらずとおもへる、すなはち外道の見なり。佛法には修證これ一等なり。

That is, if you believe that practice and awakening are not one thing, that is a heretical comprehension. In Buddhism, practice and awakening are one thing.

弄精魂とは、祗管打坐、脫落身心なり。佛祖となり祖となるを精弄魂といふ、著衣喫飯を弄精魂といふなり。

Devoting all of oneself to practice (rōshōkon 弄精魂) is just sitting (shikan taza 祇管打坐), and is dropping off body-mind (datsuraku shinjin 脫落身心). Becoming Buddha is devoting all of oneself to practice (rōshōkon 弄精魂), and wearing clothes and eating food is (also) devoting all of oneself to practice (rōshōkon 弄精魂).

(…) 心の打坐あり、身の打坐とおなじからず。身の打坐あり、心の打坐とおなじからず。身心脫落の打坐あり、身心脫落の打坐とおなじからず。旣得恁麼ならん、佛祖の行解相應なり。(…)

(…) there is the zazen of mind, which is not the same as the zazen of body. There is the zazen of body, which is not the same as the zazen of mind. There is the zazen of dropping off body-mind, which is not the same as the zazen of dropping off body-mind. But if one has already attained the state like this, the practice and the theory that Buddha teaches would completely correspond to each other. (…)

摸索當の自己、これ念なり。有身のときの念あり、無心のときも念あり。有心の念あり、無身の念あり。

The self that one finally finds after long seeking for is mindfulness (nen 念). Mindfulness (nen 念) exists when body exists, and mindfulness (nen 念) also exists in (the state of) no-mind. Mindfulness (nen 念) exists when mind exists, and mindfulness (nen 念) also exists in (the state of) no-body.

正念道支は、被自瞞の八九成なり。念よりさらに發智すると學するは捨父逃逝なり。念中發智と學するは、纏縛之甚なり。無念はこれ正念といふは外道なり。また地水火風の精靈を念とすべからず、心意識の顛倒を念と稱ぜず。まさに汝得吾皮肉骨髓、すなはち正念道支なり。

The branch of the path to the correct mindfulness is to be eighty/nighty-percent attained while being deceived by oneself. Studying that wisdom emerges from mindfulness (nen 念) again is (a wrong idea just like) abandoning one’s father and running away (from a threat). Studying that wisdom emerges within mindfulness (nen 念) is an extremely prejudiced idea. Regarding the state of no-mind (munen 無念) as correct mindfulness is a heresy. Also, you must not regard spirits of earth, water, fire, and wind as mindfulness (nen 念), and must not call the state of mind and consciousness with the wrong comprehension about the truth (tentō 顛倒) mindfulness (nen 念). (Just as Bodhidharma told his four disciples), when one attains my skin, muscle, bone, and marrow (hiniku kotsuzui 皮肉骨髓), that is the correct mindfulness.

5. Conclusions

諸藝にしましても、よく藝に成り切れというようなことをいいます。剣道、柔道にしましても、スポーツにしましても、本当に上達するためには成り切らなければならない。お茶の方でもお茶になり切るということがお茶の道に達するということの大事な条件でもあり、お茶のなかに入り込んでいるということの大事な条件でもあるわけです。以上のことから、「主客合一」ということの意味の見当がおつきだろうと思います。

When it comes to any form of Japanese traditional arts (gei 藝), it is often said that one must become an art thoroughly. When it comes to Japanese fencing (kendō 剣道), Judō (柔道), or other sports, one must become an art thoroughly in order to progress genuinely. In Japanese Tea ceremony, it is an important condition to become tea thoroughly, for attaining the ultimate path of Japanese Tea ceremony; integrating (oneself) into tea is an important condition for that (ultimate path). From the above, you may grasp the meaning of “the unification of subject and object phenomena” (shukyaku gōitsu主客合一).

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn recollects the origin of MBSR in the article entitled “Some reflections on the origins of MBSR the skillful means, and the trouble with maps” as follows: “The early papers on MBSR cited not just its Theravada roots (Kornfield 1977; Nyanaponika 1962), but also its Mahayana roots within both the Soto (Suzuki 1970) and Rinzai (Kapleau 1965) Zen traditions (and by lineage, the earlier Chinese and Korean streams), as well as certain currents from the yogic traditions (Thakar 1977) including Vedanta (Nisargadatta 1973), and the teachings of J Krishnamurti (Krishnamurti 1969, 1979) and Ramana Maharshi (Maharshi 1959). My own primary Zen teacher, Seung Sahn, was Korean, and taught both Soto and Rinzai approaches, including the broad use and value of koans and koan-based ‘Dharma combat’ exchanges between teacher and student (Seung Sahn 1976)”. |

| 2 | This succeeded in articulating the nature of Dōgen’s paradox as follows: “Dōgen, unlike Laozi, Zhuangzi, or even his Chinese Buddhist predecessors, argues that not only is reality inconsistent, issuing in paradoxes of ontology, and not only is it impossible to characterize reality discursively, leading to paradoxes of expressibility, but that our experience itself is paradoxical”. |

| 3 | Following this passage, Dōgen directly quotes Chapter 15 of The Sūtra of Buddha’s Last Instruction (Butsu yuikyō gyō 仏遺教経): 汝等比丘 若有智慧 則無貪著 常自省察 不令有失 是則於我法中 能得解脱 若不爾者 既非道人 又非白衣 無所名也. 実智慧者 則是度老病死海 堅牢船也 亦是無明闇黒 大明燈也 一切病苦之良薬也 伐煩悩樹之利斧也 是故汝等 當以聞思修慧 而自增益 若人有智慧之照 雖是肉眼 而是明見人也 是為智慧. |

| 4 | “It seems to have been T. W. Rhys Davids (1881), one of the pioneers of the Western study of Pāli texts, who first translated the Buddhist technical term sati by the English word mindfulness”. |

| 5 | This article historically explains how MBSR has played a significant role in diffusing the concept of mindfulness (Japanese: マインドフルネス) in Japan: a variety of religious traditions and medical approaches were gradually integrated into what is called マインドフルネス today. On the other hand, we should be careful about the usage of this katakana マインドフルネス; Deroche (2018) explains this point as follows: “In Japan (and elsewhere as well), we shall avoid talking about “mindfulness” in katakana マインドフルネス by implying the sense of a new tradition or method, as opposed to traditional Buddhism. The reason is that “mindfulness” is the now commonly accepted English translation for the Pāli sati. It refers thus to a core term for all Buddhist traditions, including for Japanese Buddhism (following the classical Chinese nian/nen 念, which translated –among different terms- the Sanskrit smṛti, equivalent of the Pāli sati). So if by mindfulness in katakana マインドフルネス, we intend to refer to scientific and secularized programs, we shall then be more explicit, and refer to them as ‘mindfulness-based interventions,’ and as much as possible try to specify which protocol, since there are now many”. |

| 6 | “The need to supplement a particular definition of mindfulness with an exploration of its actual function requires shifting from the question ‘What is mindfulness?’ to ‘What does mindfulness do?’. The need for such a shift can be illustrated by turning to early Buddhist definitions of mindfulness as a mental faculty (Pāli indriya, Sanskrit indriya, Chinese 根, Tibetan dbang po). One of these definitions relates mindfulness to the ability to remember what has been done or said long ago. Another definition mentions the four establishments of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna, smṛtyupasthāna, 念處, dran pa nye bar gzhag pa). Thus, the first definition describes a quality of mindfulness; the second outlines its actual application”. |

| 7 | “It is quite common today for the word sati to be translated as ‘mindfulness’, despite the fact that its pedigree derives from the Old Indic (OI) word smṛti, ‘remembrance‘, ‘memory’, ‘the whole body of sacred tradition or what is remembered by human teachers (distinguished from śruti, or what is directly heard) (MW)’”. |

| 8 | The author offers some examples, such as sati pamuṭṭhā in Majjhima Nikāya I 329, meaning “forgotten”, and sati udapādi in Dīgha Nikāya I 180, meaning “remembering”. |

| 9 | |

| 10 | Dōgen directly cites this teaching of Śākyamuni Buddha from Chapter 28 of Hokke kyō 法華経 (Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra): “Encouragement of Samantabhadra”. |

| 11 | Dōgen directly cites this passage from Keitoku dentō roku 景徳傳燈録 (The Jingde Record of the Transmission of the Lamp), vol. 2. |

| 12 | “Dōgen speaks of this ‘forgetting’ most radically in terms of his own enlightenment experience of ‘dropping off the body-mind’ (shinjin-datsuraku 信心脱落). Note that Dōgen does not speak dualistically of freeing the mind from the body. In fact, he explicitly rejects the mind–body dualism of the so-called Senika heresy and speaks of the. ‘oneness of body-mind’ (shinjin ichinyo 身心一如) along with the nonduality of the ‘one mind’ with the entire cosmos”. Please note that “信心脱落” should actually be written as “身心脫落” based on Dōgen’s original texts, just as in this paper. |

| 13 | 修行(坐禅)と証り(身心脱落)はひとつであり、(...) 修行のところに証りが現れており、修行の他に証りはない、と言えるのである。 “Practice (zazen) and enlightenment (dropping off body-mind) is one thing, (...), it can be said that enlightenment is to be embodied in practice, and there is no enlightenment other than practice”. |

| 14 | 祗管打坐、辨道功夫、身心脫落。”Just sitting, devoting all of yourself to Buddhism and contemplating, and then (you will reach the state of) dropping off body-mind”. |

| 15 | 遍參はただ祗管打坐、身心脫落なり。”Traveling to study Buddhism is nothing but just sitting, and thus dropping off body-mind”. |

| 16 | たとひ春風ふかく桃花をにくむとも、桃花おちて身心脫落せん。 “Even if you detest a peach blossom in a embracing spring wind, you will attain dropping off body-mind after it falls”. |

| 17 | See the second quoted passage in p. 12. |

| 18 | See the first quoted passage in p. 10. |

| 19 | Putney explains as follows: “(...), shikan taza is not ‘just sitting in meditation to the exclusion of other Buddhist practice,’ but rather ‘when meditating throw your whole ‘self,’ body and mind, into Zazen’”. |

| 20 | 念が智であり、智が念なのである。 “Nen 念 is wisdom, and wisdom is nen 念”. |

| 21 | Mizuno explains this concept of nyotokugo hiniku kotsuzui 汝得吾皮肉骨髓 in the commentary as follows: 汝と呼ばれる誰もが、達磨と同じ皮肉骨髄を自己としている。“Everyone who is called thou forms the self with the same body parts of Bodhidharma”. This means that everyone has the potential to attain the awakening as Bodhidharma did, for everyone has the same body parts as Bodhidharma; therefore, the only thing one should do towards awakening is devoting all of oneself to self-cultivation and practice. |

| 22 | 仏法の前では四人は等価値なる存在ではなかろうか。 “It seems that the four are just equal existences in front of dharma, doesn’t it?”. |

| 23 | See Footnote 12. |

| 24 | “Nishida develops a philosophical system and, more concretely, a philosophy of self which is not only based on Zen notions such as satori, ‘no-self’ (Jap.: muga), ‘no-mind’ (Jap.: mushin), etc. but, furthermore, either coincides with or expands on Dōgen’s notions of selfhood, alterity, continuity, and temporality”. |

| 25 | “In Japanese philosophy of the twentieth century Dōgen seemed finally to have found his audience. Several major thinkers such as Watsuji Tetsurō, Tanabe Hajime, Nishitani Keiji, Ueda Shizuteru, and Yuasa Yasuo wrote significant works about Dōgen, citing him as a major philosopher of premodern Japan”. |

| 26 | “Although his principal reference points are Linji and Dōgen, he draws on numerous Chinese and Japanese Zen writings to offer an overview of Zen philosophy that includes its epistemology, ontology, linguistic theory, and aesthetics”. |

| 27 | See Footnote 22. |

| 28 | 純粋で絶対的な主体性の状態にある自己を実現するためには、単にそれを”知る”代わりに、それに”なる”ことが必要なのである。しかし、これに達するためには、”身心”が-前述の同元の表現が示すように-”脱落”しなければならない。”坐禅”は、禅が考えているように、まず”身心”の統一へと達し、それから統一そのものが”脱落”するところへと達するための、唯一の、あるいはそうでなければ最良の可能性なのである。 “In order to realize the self in a state of pure and absolute subjectivity, it is necessary ‘becoming’ it, instead of merely ‘comprehending’ it. But, in order to reach this state, the ‘body-mind’ must—as the above-mentioned expression of Dogen indicates—“drop off”. ‘Zazen,’ as Zen philosophy sees it, is the only or otherwise the best possibility to reach the unification of body-mind first, and then the ‘dropping off’ of this unification itself”. |

References

- Anālayo, Bhikkhu. 2010. Satipaþþýána: The Direct Path to Realization. Kandy: Buddhist Puublication Society Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Anālayo, Bhikkhu. 2019. Adding historical depth to definitions of mindfulness. Current Opinion in Psychology 28: 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Warren, David Creswell, and Rechard Ryan, eds. 2015. Handbook of Mindfulness: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chihara, Tadashi 茅原正. 2018. Dōgen Zen to Mindfulness (1): Sono ronri to jissen 道元禅とマインドフルネス(Ⅰ): その論理と実践. Komazawa daigaku shinrigaku ronshū 駒澤大学心理学論集 20: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chihara, Tadashi 茅原正. 2019. Dōgen Zen to Mindfulness (2): Sono dōri to jissen 道元禅とマインドフルネス(Ⅱ): その道理と実践. Komazawa daigaku shinrigaku ronshū 駒澤大学心理学論集 21: 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Bret, ed. 2019. The Oxford Handbook of Japanese Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deroche, Marc-Henri. 2018. Rectifying Mindfulness (念) according to the Three Wisdoms (三慧): A Buddhist Philosophical Framework and Cross-Cultural Discussion. Paper presented at the 5th Japan Mindfulness Conference (日本マインドフルネス第5回大会 Nihon Mindfulness Dai Gokai Taikai), Kyoto, Japan, December 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Deroche, Marc-Henri. 2021. Mindful wisdom: The path integrating memory, judgment, and attention. Asian Philosophy 31: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dōgen 道元. 1975–1983. A Complete English Translation of DŌGEN ZENJI’S SHŌBŌGENZŌ. Translated by Kōsen Nishiyama 西山広宣. Tokyo: Nakayama Shobo, 4 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Dōgen 道元. 1990–1993. Shōbōgenzō 正法眼蔵. Edited by Yaoko Mizuno. Tokyo: Iwanami Bunko, Iwanami Shoten, 4 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Dōgen 道元. 2004–2005. Shōbōgenzō: Zenyakuchū 正法眼蔵 全訳注. Translated by Fumio Masutani 増谷文雄. Tokyo: Kōdansha Gakujutsu Bunko, Kōdansha, 8 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Dōgen 道元. 2021. Master Dōgen’s Shobogenzo. Translated by Gudo Nishijima 西嶋愚道, and Cross Chod. London: Windbell Publications, 4 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, Shūhei 藤井修平. 2017. Mindfulness no yurai to tenkai: Gendai ni okeru bukkyō to shinrigaku no musubitsuki no rei toshite マインドフルネスの由来と展開: 日本おける仏教と心理学の結びつきの例として. Chūo Gakujutsu Kenkyujo kiyō 中央学術研究所紀要 46: 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Isshō 藤田一照. 2014. Nihon ni okeru “mindfulness” no tenbō: “nihon no mindfulness” ni mukatte 日本における「マインドフルネス」の展望: 「日本のマインドフルネス」に向かって. Ningen fukushigaku kenkyū 人間福祉学研究 7: 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Funayama, Toru 船山徹. 2013. Butten ha dou kannyaku saretanoka: Sūtra ga kyōten ni naru toki 仏典はどう漢訳されたのか: スートラが経典になるとき. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, Jay, and Graham Priest. 2021. Dining on Painted Rice Cakes: Dōgen’s Use of Paradox and Contradiction. In What Can’t Be Said. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 105–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hareyama, Shunei 晴山俊英. 1997. Dōgen zenji ni okeru hinikukotsuzui ni tuite道元禅師における皮肉骨髄について. Indogaku shūkyōgaku kenkyū 印度學仏教學研究 46: 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Heisig, James, Thomas Kasulis, and John Maraldo, eds. 2011. Japanese Philosophy: A Sourcebook. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hisamatsu, Shinnichi 久松真一. 2003. Geijutsu to cha no tetsugaku 芸術と茶の哲学. Kyoto: Toueisha. [Google Scholar]

- Izutsu, Toshihiko 井筒俊彦. 2014. Zen bukkyō no tetsugaku ni mukete 禅仏教の哲学に向けて. Translated by Munehiro Nohira 野平宗弘. Tokyo: Puneumasha. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 2011. Some reflections on the origins of MBSR, skillful means, and the trouble with maps. Contemporary Buddhism 12: 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasulis, Thomas. 1978. The Zen philosopher: A review article on Dōgen scholarship in English. Philosophy East and West 28: 353–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, Eigen 古賀英彦. 1973. Zenroku ni mieru nen no ji ni tsuite 禅録に見える念の字について. Zenbunka kenkyūjo kiyō 禅文化研究所紀要 5: 179–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kopf, Gereon. 2012. Beyond Personal Identity: Dogen, Nishida, and a Phenomenology of No-Self. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Levman, Bryan. 2017. Putting smṛti back into sati (putting remembrance back into mindfulness). Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies 13: 121–49. [Google Scholar]

- Minowa, Kenryō 箕輪顕量. 2015. History of Buddhism in Japan (Nihon Bukkyō Shi 日本仏教史). Tokyo: Shunjū-sha. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Hajime 中村元. 1975. Bukkyō go dai jiten 佛教語大辞典. Tokyo: Tokyo Shoseki, 3 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Putney, David. 1996. Some problems in interpretation: The early and late writings of Dōgen. Philosophy East and West 46: 497–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rošker, Jana. 2016. Mindfulness and Its Absence–The Development of the Term Mindfulness and the Meditation Techniques Connected to It from Daoist Classics to the Sinicized Buddhism of the Chan School. Asian Studies 4: 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharf, Robert. 2014. Mindfulness and mindlessness in early Chan. Philosophy East and West 64: 933–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunoda, Tairyū 角田泰隆. 1995. Dōgen zenji no shinjin datsuraku ni tsuite 道元禅師の身心脱落について. Komazawa tankidaigaku kenkyū kiyō 駒澤短期大学研究紀要 23: 111–30. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nomura, M. Zen Philosophy of Mindfulness: Nen 念 according to Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō. Religions 2022, 13, 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090775

Nomura M. Zen Philosophy of Mindfulness: Nen 念 according to Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō. Religions. 2022; 13(9):775. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090775

Chicago/Turabian StyleNomura, Masaki. 2022. "Zen Philosophy of Mindfulness: Nen 念 according to Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō" Religions 13, no. 9: 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090775

APA StyleNomura, M. (2022). Zen Philosophy of Mindfulness: Nen 念 according to Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō. Religions, 13(9), 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090775