Religion-Related Intangible Cultural Heritage Safeguarding Practices and Initiatives of the Contemporary Chinese State

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Religion-Related Cultural Heritage Management before 2004

3. Nationwide Recognition of Religion-Related ICH since 2004

4. Local Authorities’ Initiatives and Motivations

5. State-Sponsored Academic Efforts

6. State–Religion Interactions

7. Discussions

7.1. The Absence of Explicit Mention of Religion

7.2. Regulating Religious and Cultural Affairs through ICH Safeguarding

7.3. ICH Safeguarding as a Vehicle to Advance Economic and Political Agendas

7.4. Limits and Uncertainties in the State-Centric Approach to Safeguarding Religion-Related ICH

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this article, we follow relevant academic and practical conventions to use the term “folk religion” to describe the many diffused religions prevalent in Chinese society but not officially recognised by the Chinese state. The Chinese word for this term is minjian zongjiao (民间宗教), in which minjian literally means “among the people” and zongjiao means “religion”. For more detailed discussions on the concept and some recent practices of minjian zongjiao, please see, for example, Guo et al. (2022). |

| 2 | Quyi 曲艺 is a genre of traditional Chinese oral performing arts. |

| 3 | The пасха 巴斯克节, also called Basque Festival, celebrated by China’s Russian ethnic minority located in the Erguna City of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, was listed in The Third Inventory of National Representative Intangible Cultural Heritage Projects in 2011. It is a holiday established by Orthodox Christians to commemorate the resurrection of Jesus, which remains the only nation-level ICH item inscribed in five inventories so far. |

| 4 | Since the 15th century, Nyingma, the oldest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, gradually adapted and developed a system of “five understandings” wuming 五明. The “five understandings” consists of da-wuming 大五明 (the five grand understandings) and xiao-wuming 小五明 (the five minor understandings). Da-wuming includes neiming 内明, yinming 因明, shengming 声明, yifangming 医方明, and gongqiaoming 工巧明, referring to the understanding of Buddhist doctrines, reasoning, music, medicines, and handicraft skills and techniques, respectively (Xie and He 1994). The ghee flowers handicraft knowledge and techniques come under gongqiaoming. Flowers are one of the seven offerings to the Buddha. However, the variety of flowers in Tibet is limited due to the cold local climate, and the flowering period is extremely short. Therefore, making ghee into flowers and offering them in Buddhist rituals is a method developed by Tibetans. The earliest form of ghee flowers was literally “flowers”, a kind of flower made of ghee. However, as Tibetan Buddhism evolves, ghee is increasingly used as a raw material to create artistic sculptures and landscapes. As a result, the skills of making ghee flowers evolved to make sculptures in various patterns, colours, designs, and techniques to satisfy the religious ritual’s requirements (Qingcuo and Lamu 2010). |

| 5 | Model bases are originally established to preserve and showcase specific ICH practices. However, many model bases are increasingly devoted to profit-making exercises such as producing and selling commodities to embody ICH and organising paid training sessions. |

| 6 | In this article, the term “UNESCO ICH lists” refers to the following three lists administrated by the UNESCO: (a) the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, (b) Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and (c) Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. For more information, please refer to the relevant sections on UNESCO’s official website. |

References

- Anonymous. 2011. Zhongguo Zongjiaolei Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan Baohu Xianzhuang Yu Duice Yantaohui Juxing 中国宗教类非物质文化遗产保护现状与对策研讨会举行 [The Seminar about the Status Quo and Countermeasures of China’s Religious Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection is Held]. Available online: https://www.daoisms.org/article/sort028/info-2791.html (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Anonymous. 2012. Xizang Jiada Feiyi Baohu Rang Gulao Wenhua Huanfa Xinsheng 西藏加大非遗保护让古老文化焕发新生 [Tibet’s Increased Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage has Revitalised Its Ancient Culture]. Available online: http://iwr.cssn.cn/xw/201211/t20121106_3049581.shtml (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Anonymous. 2014. Maoshan Daojiao Yinyue Ruxuan Guojiaji Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan Tuijian Xiangmu Mingdan 茅山道教音乐入选国家级非物质文化遗产推荐项目名单 [Maoshan Taoist Music was Selected as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage Recommended Project List]. Available online: https://www.daoisms.org/article/sort028/info-12887.html (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Anonymous. 2021a. Cong Yichuan Dao Caichan: Xizang Chuancheng Feiyi Zhuli Xiangcun Zhenxing 从“遗产”到“财产”: 西藏传承“非遗”助力乡村振兴 [From “Heritage” to “Property”: Tibet Inherits “Intangible Cultural Heritage” to Promote Rural Revitalization]. Available online: http://www.zytzb.gov.cn/szgzxw/358807.jhtml (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Anonymous. 2021b. Jiading Chenghuangmiao Juxing Chuantong Chenghuang Huadan Qingdian 嘉定城隍庙举行传统城隍华诞庆典 [Jiading Traditional City God’s Birthday Celebration was Held in Jiading Chenghuang Temple]. Available online: http://www.taoist.org.cn/showInfoContent.do?id=7450&p=%27p%27 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Anonymous. 2021c. Zhongyang Yinyue Xueyuan Guojiaji Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan Baohu Yu Yanjiu Zhongxin Diaoyanzu Dao Chengdushi Daojiao Xiehui Diaoyan 中央音乐学院国家级非物质文化遗产保护与研究中心调研组到成都市道教协会调研 [The Research Team of the National Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection and Research Center of the Central Conservatory of Music Visited the Taoist Association of Chengdu]. Available online: https://www.daoisms.org/article/sort028/info-46298.html (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Chao, Emily. 2012. Lijiang Stories: Shamans, Taxi Drivers, and Runaway Brides in Reform-Era China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, Adam Yuet. 2010. Religion in Contemporary China Revitalization and Innovation, 1st ed. Florence: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Digital Archive of China’s Intangible Cultural Heritage 中国非物质文化遗产数字博物馆. 2021. Database of Five Inventories of National Representative Intangible Cultural Heritage Projects. Available online: https://www.ihchina.cn/project.html#target1 (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Feng, Yongtai 冯永泰. 2014. Minjian Xinyang Yu Hexie Shehui de Goujian—Jiyu Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan Shijiao 民间信仰与和谐社会的构建—基于非物质文化遗产视角 [Folk Belief and Construction of Harmonious Society: From the Perspective of Intangible Cultural Heritage]. Dongyue Tribune 35: 171–75. [Google Scholar]

- GOSC (General Office of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China). 2005. 国家级非物质文化遗产代表作申报评定暂行办法 [Declaration and Assessment of Representative Items of National Intangible Cultural Heritage]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2005-08/15/content_21681.htm (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Guo, Chao, Huijuan Hua, and Xiwen Geng. 2021. Incorporating Folk Belief into National Heritage: The Interaction between Ritual Practice and Theatrical Performance in Xiud Yax Lus Qim (Yalu wang) of the Miao (Hmong) Ethnic Group. Religions 12: 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Huanyu, Canglong Wang, Youping Nie, and Xiaoxiang Tang. 2022. Hybridising Minjian Religion in South China: Participants, Rituals, and Architecture. Religions 13: 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Lihe 韩立鹤. 2016. Fojiao feiwuzhi wenhua yichan yantaohui zai nanjing dabaoensi yizhiboshiguan longzhong zhaokai 佛教非物质文化遗产研讨会在南京大报恩寺遗址博物馆隆重召开 [The Symposium on the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Buddhism was Held in the Museum of Da Bao’en Temple in Nanjing]. Available online: https://www.chinabuddhism.com.cn/special/jlkjc/ycyt1/2016-07-06/10941.html (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- He, Limin 和力民. 1995. Lijiang dongbajiao xianzhuang yanjiu 丽江东巴教现状研究 [Study on the Quo Status of Dongba Religion in Lijiang]. Journal of Yunnan Minzu University (Social Sciences) 2: 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- He, Daojun 何道君. 2011. Qingcheng gongfu zhenhan disanjie guoji feiwuzhi wenhua yichan jie 青城功夫震撼第三届国际非物质文化遗产节 [Qingcheng Kongfu Shocked the Third International Intangible Cultural Heritage Festival]. Available online: https://www.daoisms.org/article/sort028/info-3303.html (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Hetmanczyk, Philipp. 2015. Party Ideology and the Changing Role of Religion: From “United Front” to “Intangible Cultural Heritage”. Asiatische Studien—Études Asiatiques 69: 165–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Yufu 胡玉福. 2018. Feiyi baohu biaozhun yu wenhua duoyangxing de maodun yu tiaoxie 非遗保护标准与文化多样性的矛盾与调谐 [The Contradiction and Harmony between the Standards for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage and Cultural Diversity]. Cultural Heritage 57: 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Zhiguo 鞠志国. 2013. Zengfu caishen liguizu chuanshuo bei lieru ziboshi feiwuzhi wenhua yichan minlu 增福财神李诡祖传说被列入淄博市非物质文化遗产名录 [The Legend of Li Guizu, a Taoist Immortal of Wealth and Fortune, has been Included in the Intangible Cultural Heritage List of Zibo City]. Available online: https://www.daoisms.org/article/sort028/info-9498.html (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Kang, Xiaofei. 2009. Two Temples, Three Religions, and a Tourist Attraction: Contesting Sacred Space on China’s Ethnic Frontier. Modern China 35: 227–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Ming-chun. 2018. ICH-isation of popular religions and the politics of recognition in China. In Safeguarding Intangible Heritage: Practices and Politics. Edited by Natsuko Akagawa and Laurajane Smith. London: Routledge, pp. 187–99. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fan 李凡. 2015. Shenling xinyang de biaozhunhua yu bentuhua 神灵信仰的标准化与本土化 [The Standardisation and Localisation of Deity Beliefs]. Folklore Studies 15: 139–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Wenqi. 2016. Legal Protection for China’s Traditional Religious Knowledge. Religions 7: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Jie 刘杰. 2019. Feiyi fupin de zuoyong jizhi, shijian kunjing yu lujing youhua 非遗扶贫的作用机制、实践困境与路径优化 [The Mechanisms, Practical Dilemmas and Route Optimization of Poverty Alleviation through Intangible Cultural Heritage]. Fiscal Science, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Rongna 刘蓉娜. 2019. Chuxiong yixiang huobajie: Wenhua zhanshi de wutai chengshi fazhan de zaiti 楚雄彝乡火把节:文化展示的舞台 城市发展的载体 [Chuxiong Yi Torch Festival: A Stage for Cultural Display and Carrier of City Development]. Available online: http://news.cctv.com/2019/07/30/ARTIC6OrXqMfdGQHLyrYzlhJ190730.shtml (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Mathisen, Stein R. 2020. Souvenirs and the Commodification of Sámi Spirituality in Tourism. Religions 11: 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MC (Ministry of Culture, the People’s Republic of China). 2006. 文化部关于申报第一批国家级非物质文化遗产代表作的通知 [Notice of the Ministry of Culture on Recommending and Applying for the First Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage Representative Projects]. Available online: http://zwgk.mct.gov.cn/zfxxgkml/fwzwhyc/202012/t20201206_916787.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- MC (Ministry of Culture, the People’s Republic of China). 2007. 文化部关于申报第二批国家级非物质文化遗产名录项目有关事项的通知 [Notice of the Ministry of Culture on Recommending and Applying for the First Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage Representative Projects]. Available online: http://zwgk.mct.gov.cn/zfxxgkml/fwzwhyc/202012/t20201206_916789.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- MC (Ministry of Culture, the People’s Republic of China). 2009. 文化部关于申报第三批国家级非物质文化遗产名录项目有关事项的通知 [Notice of the Ministry of Culture on Applying for the Third Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage Representative Projects]. Available online: https://www.mct.gov.cn/whzx/bnsj/fwzwhycs/201111/t20111128_765093.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- MC (Ministry of Culture, the People’s Republic of China). 2013. 文化部关于推荐申报第四批国家级非物质文化遗产代表性项目有关事项的通知 [Notice of the Ministry of Culture on Recommending and Applying for the Fourth Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage Representative Projects]. Available online: http://zwgk.mct.gov.cn/zfxxgkml/fwzwhyc/202012/t20201206_916828.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- MCT (Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the People’s Republic of China). 2019. 文化和旅游部关于推荐申报第五批国家级非物质文化遗产代表性项目的通知 [Notice of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism on Recommending and Applying for the Fifth Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage Representative Projects]. Available online: http://zwgk.mct.gov.cn/zfxxgkml/fwzwhyc/202012/t20201206_916886.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Meng, Xu 孟旭. 2021. Shengtang Miaohui Ruxuan Suzhou Guojia Ji Feiyi Xiangmu Zengzhi 33 Xiang “圣堂庙会”入选苏州国家级非遗项目增至33项 [Shengtang Miaohui becomes Suzhou’s 33rd ICH items listed into the five Inventories of National Representative Intangible Cultural Heritage Projects]. Available online: https://jnews.xhby.net/v3/waparticles/1206/erUiFSfkotieJLQJ/1 (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Nakano, Ryoko, and Yujie Zhu. 2020. Heritage as soft power: Japan and China in international politics. International Journal of Cultural Policy 26: 869–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, Tim, and Donald S. Sutton. 2010. Faiths on Display Religion, Tourism, and the Chinese State. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Qingcuo 青措, and Lamu 拉姆. 2010. Zhongguo feiwuzhi wenhua yichan-taer si suyou hua 中国非物质文化遗产——塔尔寺酥油花 [Chinese Intangible Cultural Heritage-Tar Temple Ghee Flower]. The Voice of Dharma, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Roszak, Piotr. 2020. Mute Sacrum. Faith and Its Relation to Heritage on Camino de Santiago. Religions 11: 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schreiber, Hanna. 2017. Heritage as soft power-Exploring the Relationship. International Journal of Intangible Heritage 12: 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shefferman, David A. 2014. Rhetorical Conflicts: Civilizational Discourse and the Contested Patrimonies of Spain’s Festivals of Moors and Christians. Religions 5: 126–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simone-Charteris, Maria T., and Stephen W. Boyd. 2010. The Development of Religious Heritage Tourism in Northern Ireland: Opportunities, Benefits and Obstacles. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal 58: 229–57. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Laurajane, and Natsuko Akagawa. 2008. Intangible Heritage, 1st ed. Chichester: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Qi 宋琦, Guojun Wang 王国军, and Duruo Zhou 周杜若. 2017. Meishan wenhua shiyu xia zhumei taigushi zhanyan ji wenhua bianqian-yige fei shaoshu minzu jujidi de shaoshu minzu minsu huodong tanxun 梅山文化视域下珠梅抬故事展演及文化变迁—一个非少数民族聚集地的少数民族民俗活动探寻 [Zhumei Taigushi Performance and Cultural Change: An Exploration of Ethnic Folk Activities in a Non-minority Region from the Perspective of Meishan Culture]. 贵州民族研究 [Guizhou Ethnic Studies] 38: 123–27. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, Theo, and Yu Tao. 2022. The Emergence of Transcultural Humanistic Buddhism through the Lens of Religious Entrepreneurship. Asian Studies Review 46: 312–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China 国务院. 1997. Chuantong gongyi meishu baohu tiaoli 传统工艺美术保护条例 [Regulations on the Protection of Traditional Arts and Crafts]. Available online: http://www.ihchina.cn/zhengce_details/11546 (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Su, Junjie. 2019. Understanding the changing Intangible Cultural Heritage in tourism commodification: The music players’ perspective from Lijiang, China. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 17: 247–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Xiangming 孙翔鸣. 2011. Shijie feiwuzhi wenhua yichan jinling kejing jiyi xiang shiren zhanshi 世界非物质文化遗产金陵刻经技艺向世人展示 [The World Intangible Cultural Heritage Jinling Sutra Carving Skills Displays to the World]. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/shipin/2011/04-17/news36439.html (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Tan, Hao 谭浩, and Qian Wang 王茜. 2009. Baohu he chuancheng fojiao feiwuzhi wenhua yichan yiyi zhongda 保护和传承佛教非物质文化遗产意义重大 [It Is of Great Significance to Protect and Inherit Buddhism’s Intangible Cultural Heritage]. Available online: http://news.sohu.com/20090329/n263077960.shtml (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Tao, Yu. 2012. A Solo, a Duet or an Ensemble? Analysing the Recent Development of Religious Communities in Contemporary Rural China. London: Europe China Research and Advice Network. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Yu. 2015. Unlikely Friends of the Authoritarian and Atheist Ruler: Religious Groups and Collective Contention in Rural China. Politics and Religion 8: 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tao, Yu. 2017. The Historical Foundations of Religious Restrictions in Contemporary China. Religions 8: 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tao, Yu. 2018. Agitators, Tranquilisers, or Something Else: Do Religious Groups Increase or Decrease Contentious Collective Action? Religions 9: 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tao, Yu. 2019. Protest and Religion: Christianity in the People’s Republic of China. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion. Edited by Paul A. Djupe, Mark J. Rozell and Ted G. Jelen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1041–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Yu. 2021. An Introduction to Confucius, His Ideas and Their Lasting Relevance. Available online: https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-an-introduction-to-confucius-his-ideas-and-their-lasting-relevance-160708 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Tao, Yu, and Ed Griffith. 2018. The State and ‘Religious Diversity’ in Chinese Dissertations. Religions 9: 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tao, Yu, and Ed Griffith. 2019. Religious Diversity with Chinese Characteristics? Meanings and Implications of the Term ‘Religious Diversity’ in Contemporary Chinese Dissertations. In Religious Diversity in Asia. Edited by Jørn Borup, Marianne Qvortrup Fibiger and Lene Kühle. Leiden: Brill, pp. 169–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Yu, and Mingxing Liu. 2013. Intermediate associations, grassroots elites and collective petitioning in rural China. In Elites and Governance in China. Edited by Xiaowei Zang and Chien-wen Kou. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 110–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Yu, and Cheng Yen Loo. 2022. Chinese Identities in Australia amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Backgrounds, Challenges, and Directions for Future Research. British Journal of Chinese Studies 12: 129–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Yu, and Theo Stapleton. 2018. Religious Affiliations of the Chinese Community in Australia: Findings from 2016 Census Data. Religions 9: 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tao, Yu 陶郁, Linke Hou 侯麟科, and Mingxing Liu 刘明兴. 2016. Zhangchiyoubie: Shangji kongzhili, xiaji zizhuxing he nongcun jiceng zhengling zhixing 张弛有别:上级控制力、下级自主性和农村基层政令执行 [The Control, Discretion, and Policy Implementation of Local Authorities in Rural China]. Society 36: 107–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Yu 陶郁, Mingxing Liu 刘明兴, and Linke Hou 侯麟科. 2020. Difang Zhili Shijian: Jiegou yu Xiaoneng 地方治理实践:结构与效能 [The Practice of Local Governance in China: Structures and Effects]. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Qing 田青. 2019. Zhongguo Zongjiao Lei Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan de Xianzhuang yu Baohu Yanjiu 中国宗教类非物质文化遗产的现状与保护研究 [Research on the Status Quo and Protection of China’s Religious Intangible Cultural Heritage]. Beijing: Culture and Art Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, Dallen, and Daniel Olsen. 2006. Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tsivolas, Theodosios. 2014. Law and Religious Cultural Heritage in Europe. New York: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- UNESCO. 1977. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide78.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- UNESCO. 1993a. Establishment of a System of “Living Cultural Properties” (Living Human Treasures) at UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000095831 (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- UNESCO. 1993b. International Consultation on New Perspectives for UNESCO’s Programme: The Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/events?meeting_id=00223 (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- UNESCO. 2018. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2018 Edition. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/2003_Convention_Basic_Texts-_2018_version-EN.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Urien-Lefranc, Fanny. 2020. From Religious to Cultural and Back Again: Tourism Development, Heritage Revitalization, and Religious Transnationalizations among the Samaritans. Religions 11: 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Zeijden, Albert. 2014. Spiritual Renewal and the Safeguarding of Religious Traditions in the Netherlands. Available online: http://www.ichngoforum.org/spiritual-renewal-and-the-safeguarding-of-religious-traditions-in-the-netherlands/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Wang, Xiaoyi 王晓易. 2014. Disanjie Zhongguo Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan Bolanhui Kaimu, Laoshan Daojiao Wenhua Shengtai Baohu Shiyanqu Canzhan 第三届中国非物质文化遗产博览会开幕,崂山道教文化生态保护实验区参展 [The Third China Intangible Cultural Heritage Expo Opened with Laoshan Taoist Cultural and Ecological Protection Experimental Zone Participating in]. Available online: https://www.163.com/news/article/A8E5CVER00014Q4P.html (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Wang, Xiaobing 王霄冰. 2015. Jikong liyi de biaozhunhua yu zaidihua 祭孔礼仪的标准化与在地化 [The Standardisation and localisation of the Rituals for Worshipping Confucius]. Folklore Studies 15: 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chongdao 王崇道. 2021. Wuhan Dadaoguan Juban Wuhanshi Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan Daojiao Quanzhenpai Yinyue Zhanyan Huodong 武汉大道观举办武汉市非物质文化遗产道教(全真派)音乐展演活动 [Wuhan Taoist Temple held Wuhan Intangible Cultural Heritage Taoism (Quanzhen Faction) Music Performance Activities]. Available online: https://www.daoisms.org/article/sort028/info-44447.html (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Wang, Jing 王静, and Jianhua Liang 梁建华. 2019. Zhonghuo Zongjiao Xuehui Dangdai Shehui yu Zongjiao Yishu Zhuanye Weiyuanhui Ji Dangdai Shehui yu Zongjiao Yishu Jiangzuo Diyiqi Zai Jing Juxing 中国宗教学会当代社会与宗教艺术专业委员会成立暨“当代社会与宗教艺术讲座”第1期在京举行 [The Establishment of Contemporary Society and Religious Art Professional Committee of China Religious Society and the 1st Session of “Contemporary Society and Religious Art Lecture” was Held in Beijing]. Available online: http://www.zytzb.gov.cn/zgzj/304300.jhtml (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Wang, Zongda 汪宗达, and Chengguo Yin 尹承国. 1994. Xiandai Jingdezhen taoci jingji shi 現代景德鎮陶瓷经济史(1949–1993) [Modern Economic History of Jingdezhen (1949–1993)]. Beijing: 中国书籍出版社 [Zhongguo Shuji Publications]. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Tong 吴彤. 2019. Shui keneng touzi feiyi 谁可能投资非遗 [Who Is Likely to Invest in Intangible Cultural Heritage Undertakings]. Available online: https://apich.net/newsinfo/1213213.html (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Wuhan Ethnic and Religious Affairs Commission 武汉市民族宗教事务委员会. 2018. Wuhan Daojiao Yinyue Chenggong Shenyi 武汉道教音乐成功申遗 [Wuhan Taoist Music Successfully Registered for World Heritage]. Available online: http://mzw.wuhan.gov.cn/XWZX_13631/MZXW_13635/202001/t20200108_678833.shtml (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Xie, Zuo 谢佐, and Bo He 何波. 1994. 藏族古代教育史略 [The History of Tibetan Ancient Education]. Xining: Qinghai People Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yawen. 2022. Craft Production in a Socialist Planned Economy: The Case of Jingdezhen’s State-Owned Porcelain Factories in the Mid to Late Twentieth Century. The Journal of Modern Craft 15: 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Yawen, and Yu Tao. 2022. Cultural Impacts of State Interventions: Traditional Craftsmanship in China’s Porcelain Capital in the Mid to Late 20th Century. International Journal of Intangible Heritage 17: 214–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yawen, Yu Tao, and Benjamin Smith. 2021. China’s emerging legislative and policy framework for safeguarding intangible cultural heritage. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, Smita. 2019. Heritage Tourism and Neoliberal Pilgrimages. Journeys 20: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2011. Religion in China: Survival and Revival under Communist Rule. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Zhejun 郁喆隽. 2018. Jiangnan miaohui de xiandaihua zhuanxing: Yi shanghai jinze xiangxun he sanlin shengtang chuxun weili 江南庙会的现代化转型:以上海金泽香汛和三林圣堂出巡为例 [Modernizing Temple Fairs in Jiangnan Area: Pilgrimage Festival in Jinze and Folk-religious Procession in Sanlin as Examples]. 文化遗产 [Cultural Heritage], 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Fengjian 翟风俭. 2020. Woguo de Zongjiao Lei Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan 我国的宗教类非物质文化遗产 [China’s Religious Intangible Cultural Heritage]. Available online: http://www.ihchina.cn/luntan_details/20810.html (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Zhang, Lan 张兰. 2014. Xizang Minzu Chuantong Shougongyi Zhaxijicai: Zai Diaoke yu Qiaoda Zhong Zhanfang Meili 西藏民族传统手工艺扎西吉彩:在雕刻与敲打中绽放魅力 [Tibetan Traditional Craftsmanship of Zhaxi Jicai: The Charm Shines in Carving and Beating]. Available online: http://news.cntv.cn/2014/03/18/ARTI1395115216407309_3.shtml (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Zhang, Qingyuan 张清源, and Lin Lu 陆林. 2019. Zongjiao lvyoudi liyi xiangguanzhe quanli-liyi guanxi geju yu xingcheng jizhi-yi jiuhuashan weili 宗教旅游地利益相关者权力-利益关系格局与形成机制—以九华山为例 [Study on the power-interest relationship in religious tourism destination: A case study of Jiuhua Mountain]. 旅游学刊 [Tourism Tribune] 34: 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Junjie 赵俊杰. 2019. Miaobi Shengjin, Regong Wenhua Chanye Chuanshou 7.5 Yi Yuan 妙笔生金,热贡文化产业创收7.5亿元 [The cultural industry of Regong has generated 750 million yuan in revenue]. Available online: http://www.qinghai.gov.cn/mzfw/system/2019/02/27/010325012.shtml (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Zhou, Zhiwen 周志雯. 2021. Daojiao Taoci Wenhua Zuotanhui Zhaokai 道教陶瓷文化座谈会召开 [Symposium on Taoist Ceramic Culture was Held]. Available online: http://www.taoist.org.cn/showInfoContent.do?id=7343&p=%27p%27 (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Zhu, Yujie. 2016. Heritage Making of Lijiang: Governance, Reconstruction, and Local Naxi Life. In World Heritage on the Ground, Ethnographic Perspectives. Edited by Christoph Brumann and David Berliner. Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Yujie. 2018. Heritage and Romantic Consumption in China. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Yujie. 2020a. Heritage and Religion in China. In Handbook on Religion in Contemporary China. Edited by Stephan Feutchtwang. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Yujie. 2020b. Ethnic Religion After Disasters-Intangible Cultural Heritage in China. In Heritage and Religion in East Asia. Edited by Shu-Li Wang, Michael Rowlands and Yujie Zhu. London: Routledge, pp. 88–102. [Google Scholar]

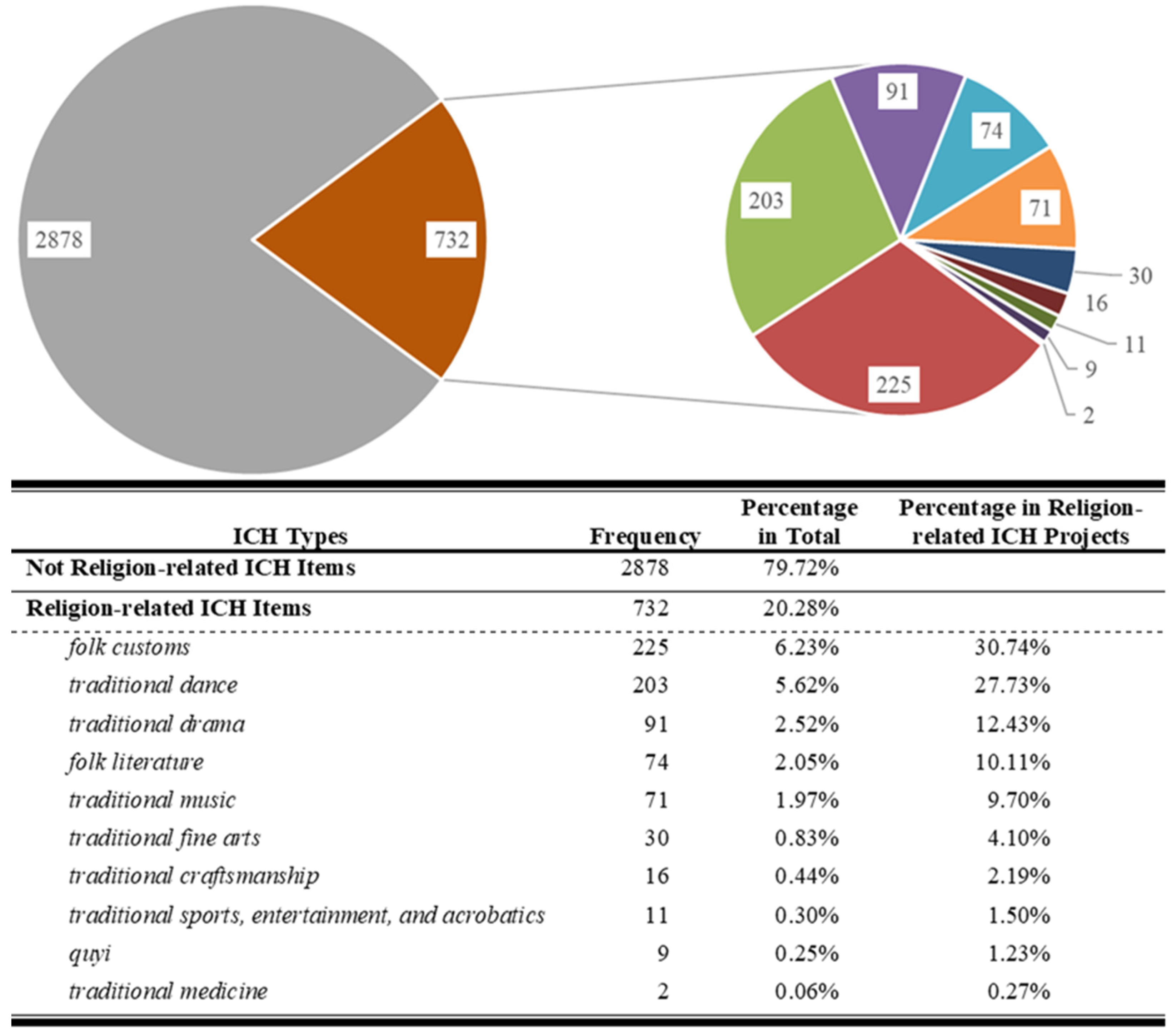

| ICH Types | Folk Customs | Traditional Dance | Traditional Drama | Folk Literature | Traditional Music | Traditional Fine Arts | Traditional Craftsmanship | Traditional Sports, Entertainment, and Acrobatics | Quyi | Traditional Medicine | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Religion | |||||||||||

| Han | Folk religions | 121 | 123 | 57 (a) | 23 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 340 |

| Buddhism | 4 | 0 | 38 (b) | 11 | 33 (d) | 0 | 4 | 6 (f) | 0 | 1 | 97 | |

| Taoism | 19 | 0 | 42 (c) | 2 | 26 (e) | 0 | 0 | 6 (g) | 5 | 0 | 100 | |

| Islam | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Christianity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 144 | 123 | 74 | 36 | 62 | 9 | 4 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 471 | |

| Tibetan | Folk religions | 6 | 13 (h) | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Buddhism | 4 | 16 (i) | 13 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 64 | |

| Taoism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Islam | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Christianity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 10 | 26 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 19 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 91 | |

| Miao | Folk religions | 10 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 |

| Buddhism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Taoism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Islam | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Christianity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 10 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | |

| Yao | Folk religions | 5 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Buddhism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Taoism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Islam | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Christianity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 5 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | |

| Mongolian | Folk religions | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Buddhism | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |

| Taoism | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Islam | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Christianity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Tao, Y. Religion-Related Intangible Cultural Heritage Safeguarding Practices and Initiatives of the Contemporary Chinese State. Religions 2022, 13, 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080687

Xu Y, Tao Y. Religion-Related Intangible Cultural Heritage Safeguarding Practices and Initiatives of the Contemporary Chinese State. Religions. 2022; 13(8):687. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080687

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yawen, and Yu Tao. 2022. "Religion-Related Intangible Cultural Heritage Safeguarding Practices and Initiatives of the Contemporary Chinese State" Religions 13, no. 8: 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080687

APA StyleXu, Y., & Tao, Y. (2022). Religion-Related Intangible Cultural Heritage Safeguarding Practices and Initiatives of the Contemporary Chinese State. Religions, 13(8), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080687