The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Interest in Prayer and Spirituality in Poland According to Google Trends Data in the CONTEXT of the Mediatisation of Religion Processes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To investigate whether the trend of increased interest in the topic of prayer on the Internet, as indicated by Bentzen, is reflected in the Polish-language Internet.

- To examine specific queries on Google referring to a selection of specific prayers and religious practices.

- To analyse the factors that may have created information overload and influenced the results shown in Google Trends.

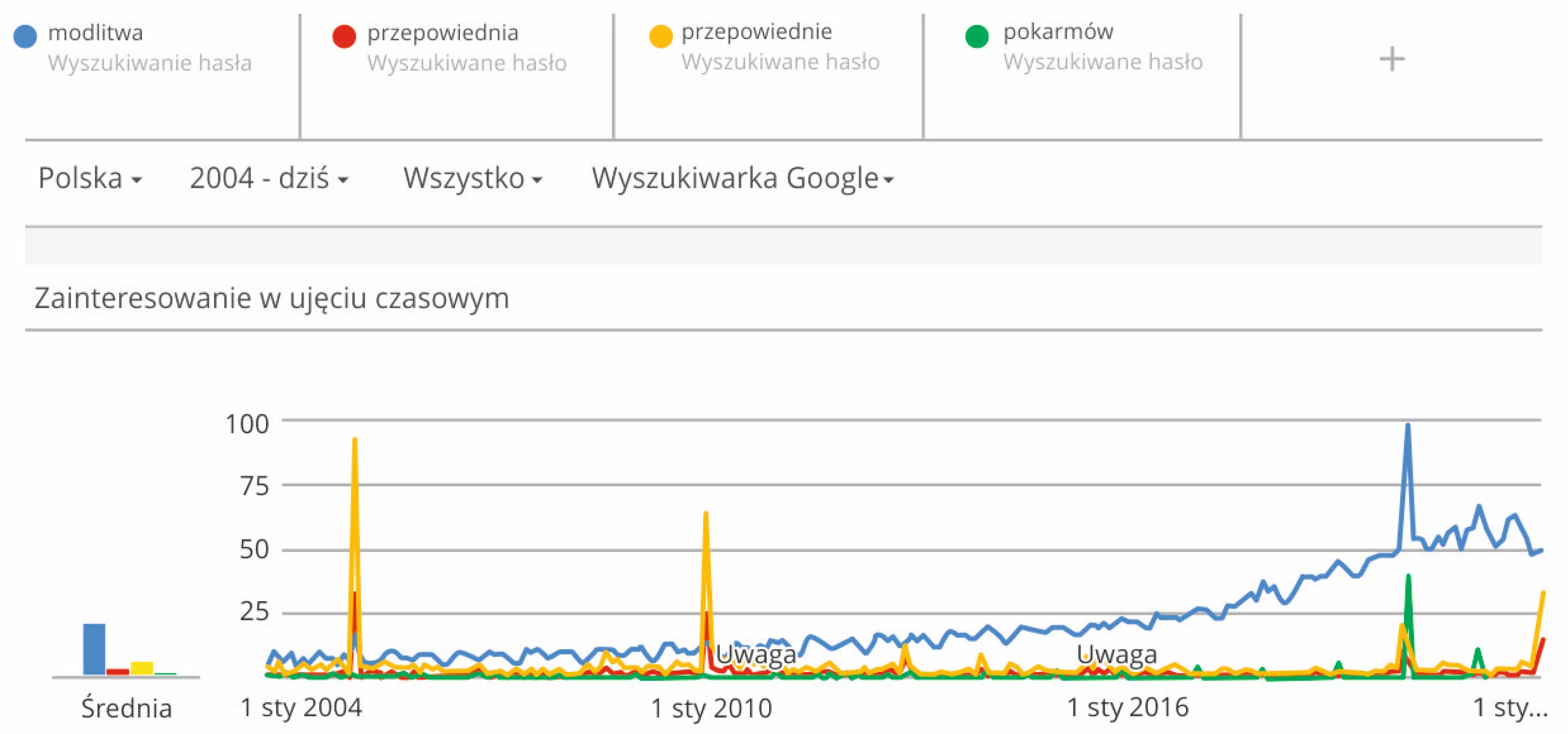

- To examine whether an interest in prayer also means an increased interest in predictions and prophecies.

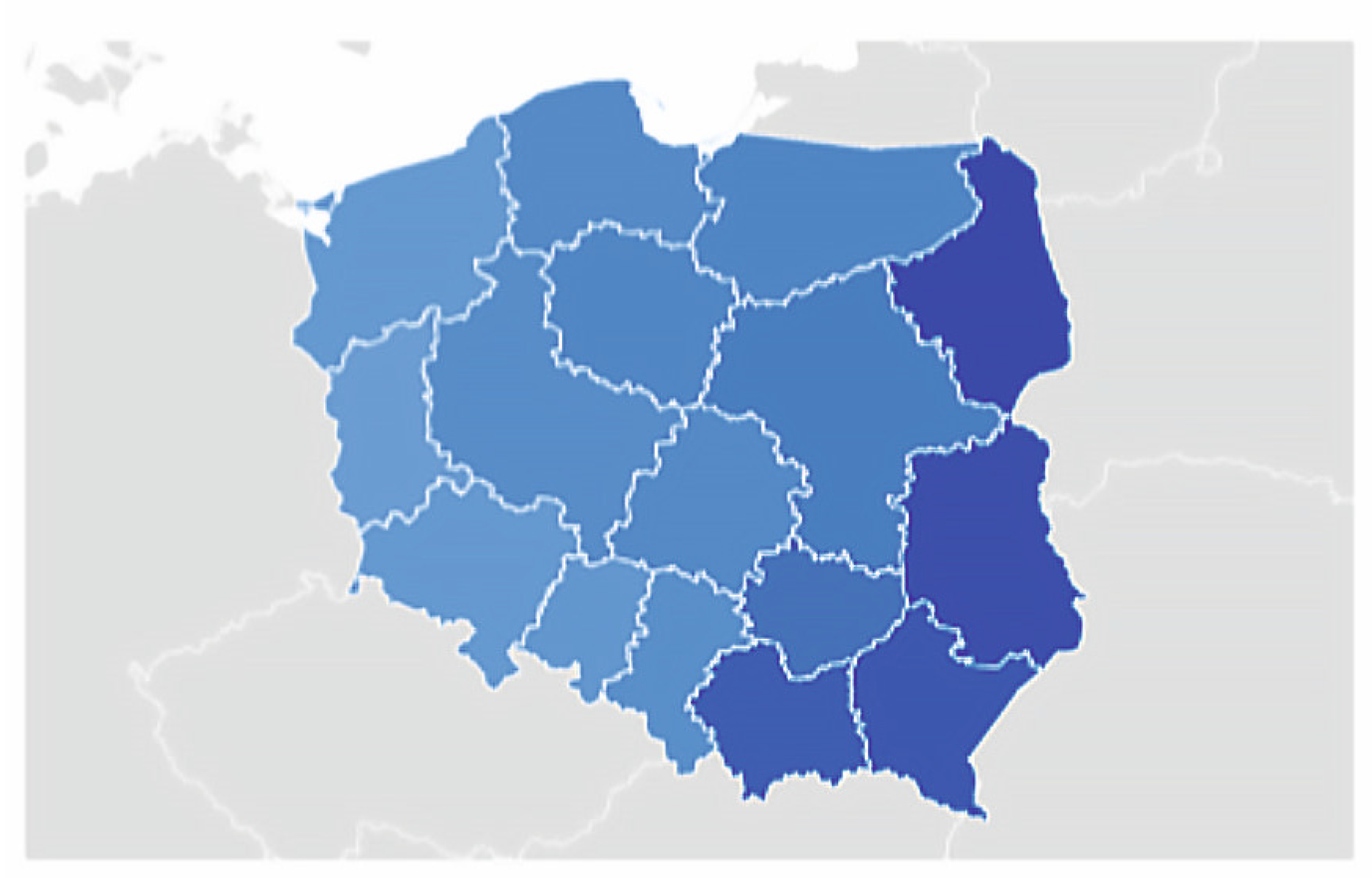

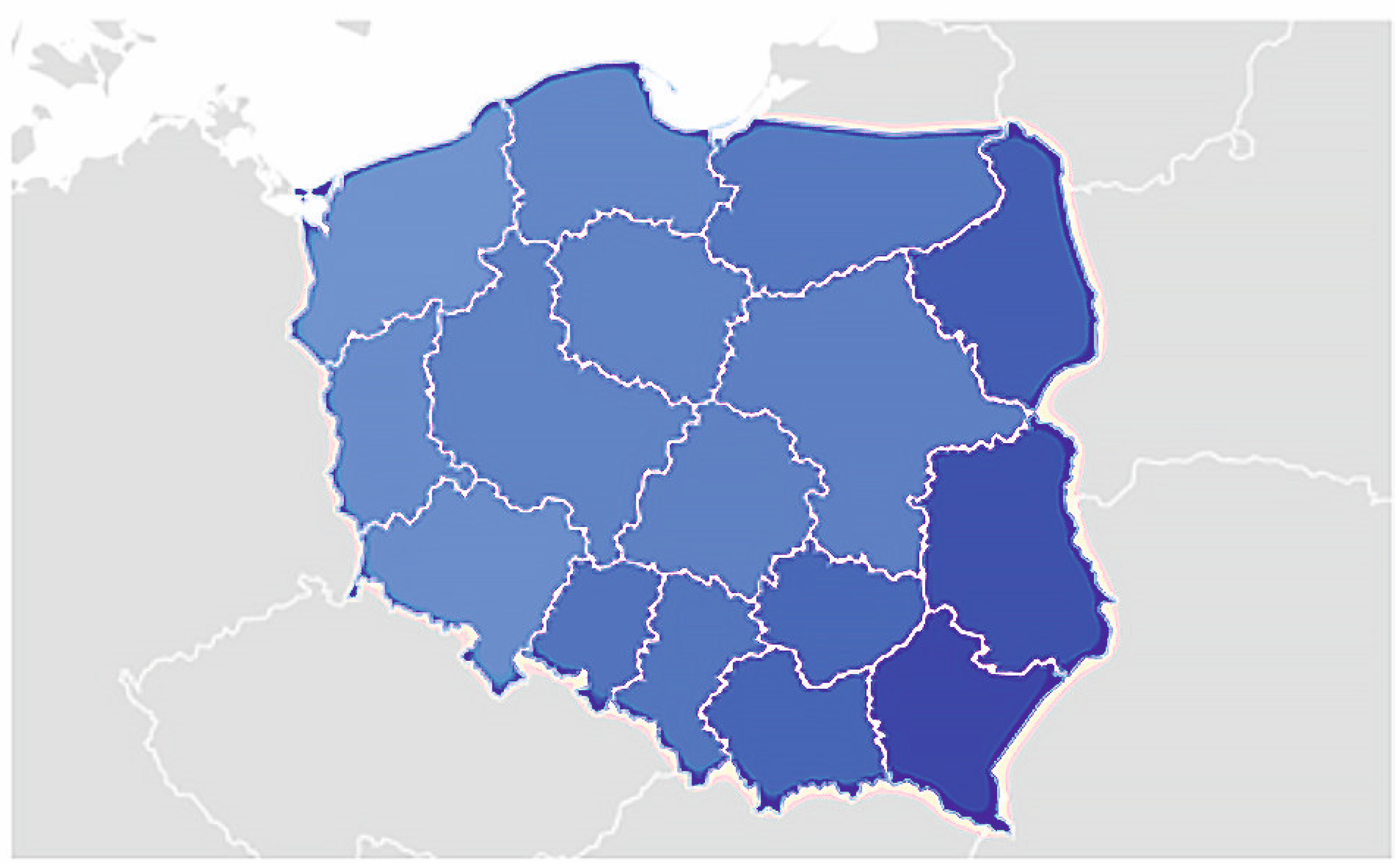

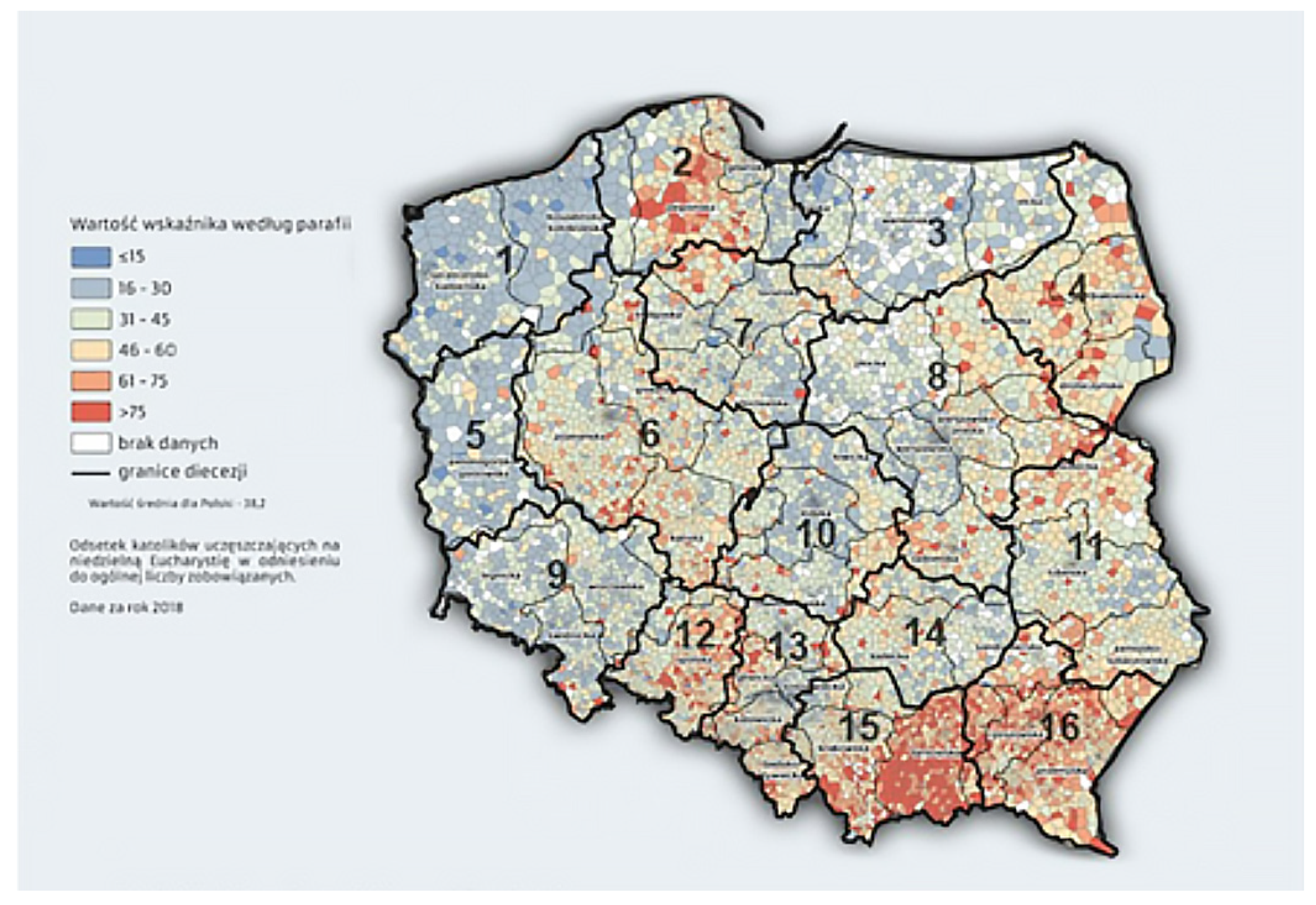

- To investigate whether there is a noticeable connection between the popularity of particular queries and religiosity in a given region of Poland, as reflected in secondary data (annual surveys conducted by the Institute of Catholic Church Statistics in Poland—ISKK).

1.1. Crisis Situations and Interest in Religion and the Supernatural

1.2. Religiosity and Level of Religious Knowledge among Poles

1.3. Mediatisation of Religion

1.4. The Internet as a Source of Information

1.5. Internet Users in Poland

1.6. The Google Group and Google Trends

2. Method

Characteristics of the Research

- Real-time data are samples covering the last seven days.

- Non-dynamic data are separate samples that cover the period from 2004 to 36 h before the search.

- Each data point is divided by the total number of queries in that region and period to assess its relative popularity. Otherwise, regions with the most queries will always be ranked highest.

- The result is then scaled from 0 to 100 based on the proportionality of the topic to all queries of all topics.

- If the search interest for a selected keyword is the same in different regions, it does not mean that the total number of queries is also the same in those regions.

3. Research

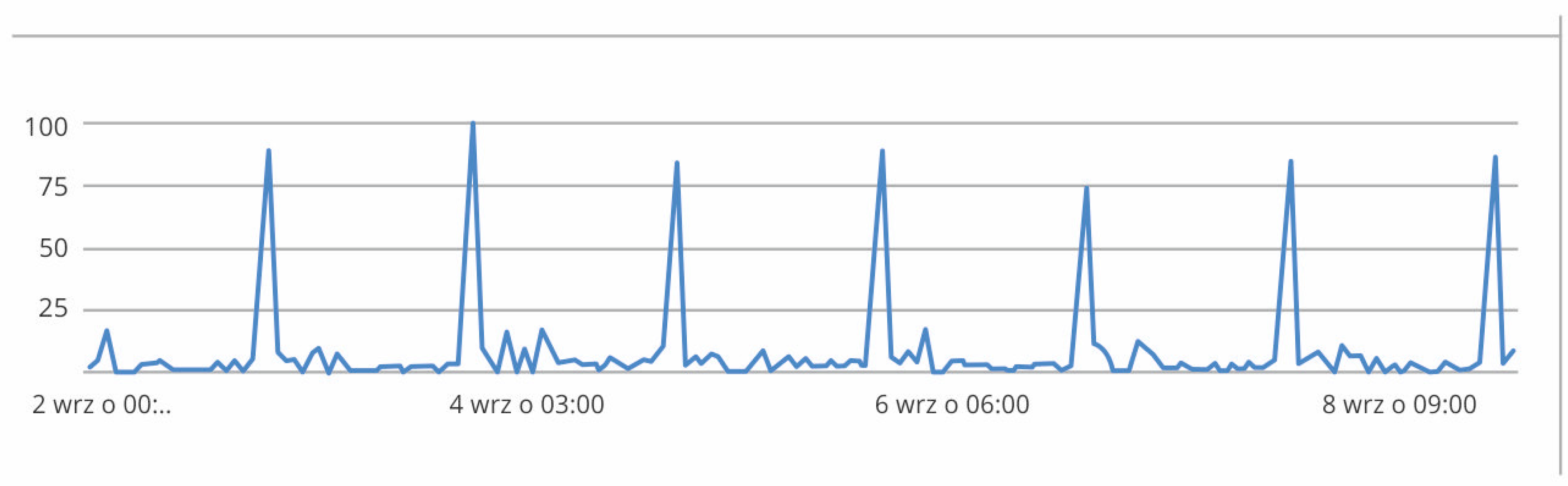

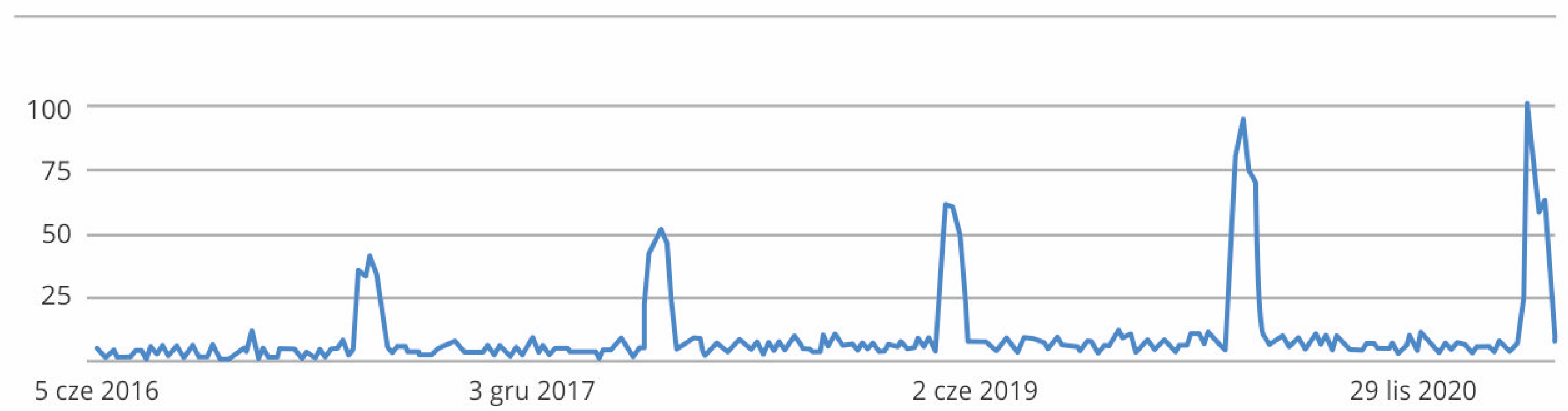

3.1. Keyword Observation: “The Call of Jasna Góra” (Polish: “Apel Jasnogórski”)

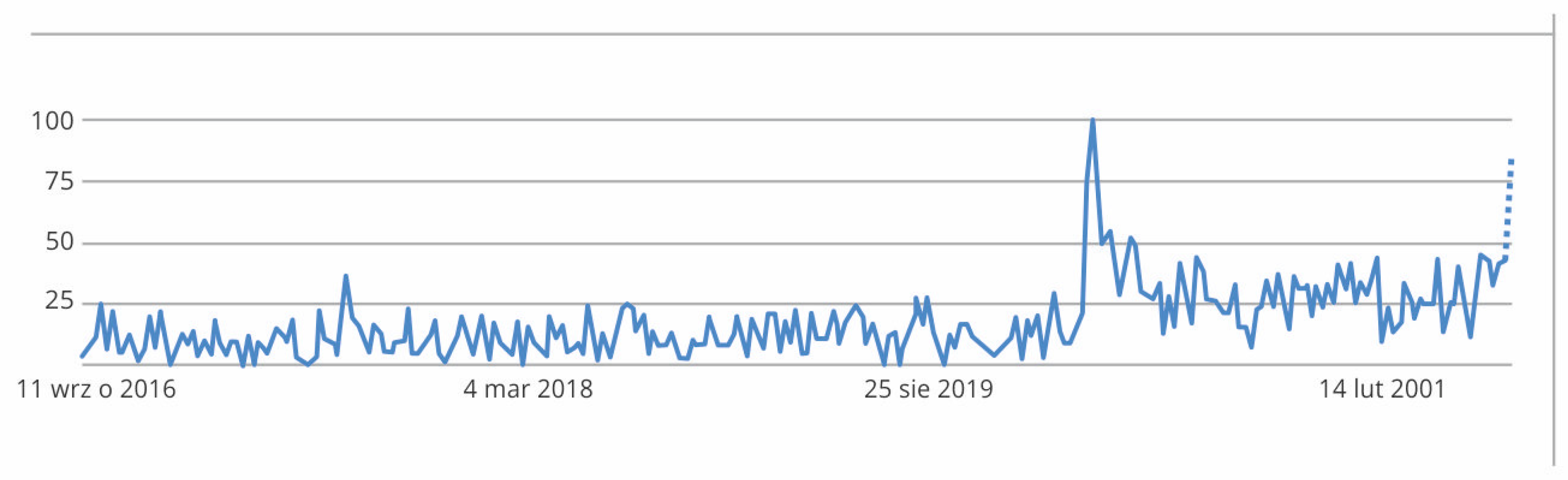

3.2. Keyword Observation: “litany” (Polish: “litania”)

3.3. Keyword Observation: “Litany of Loreto” (Polish: “Litania Loretańska”)

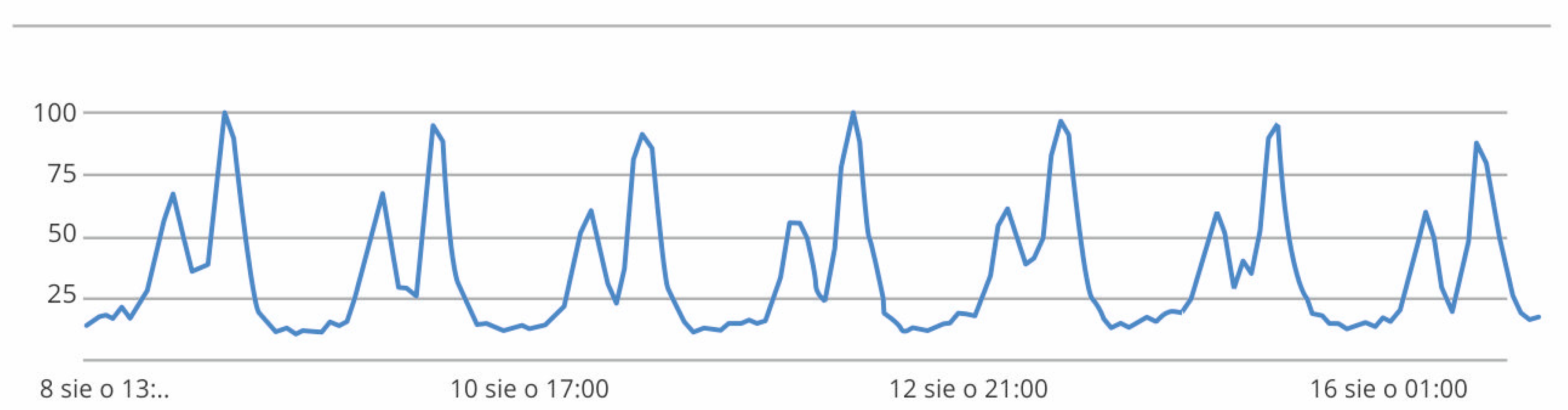

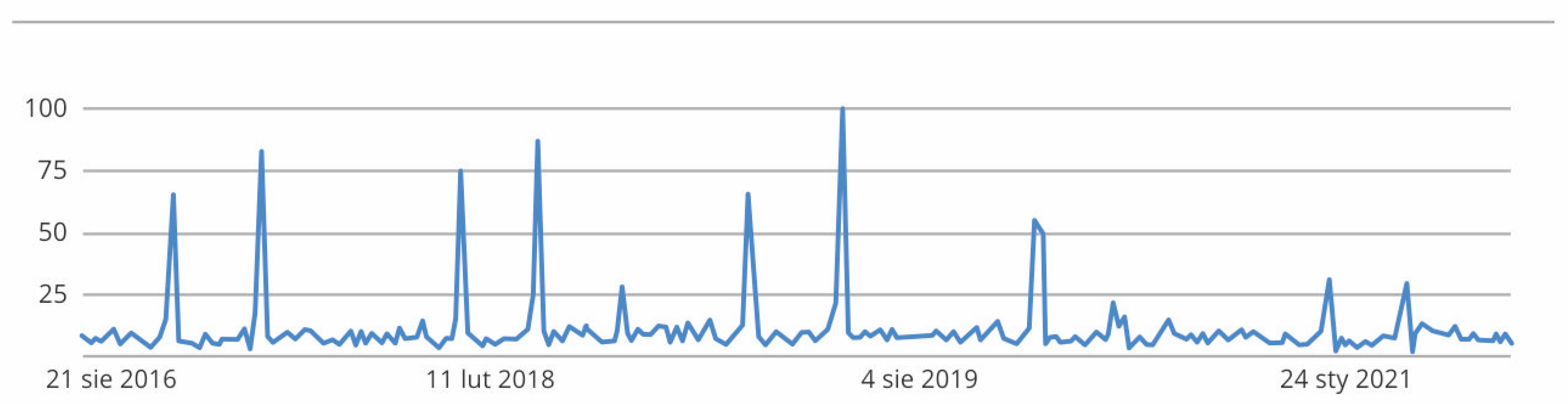

3.4. Keyword Observation: “prayer” (Polish: “modlitwa”)

3.5. Keyword Observation: “confession” (Polish: “spowiedź”)

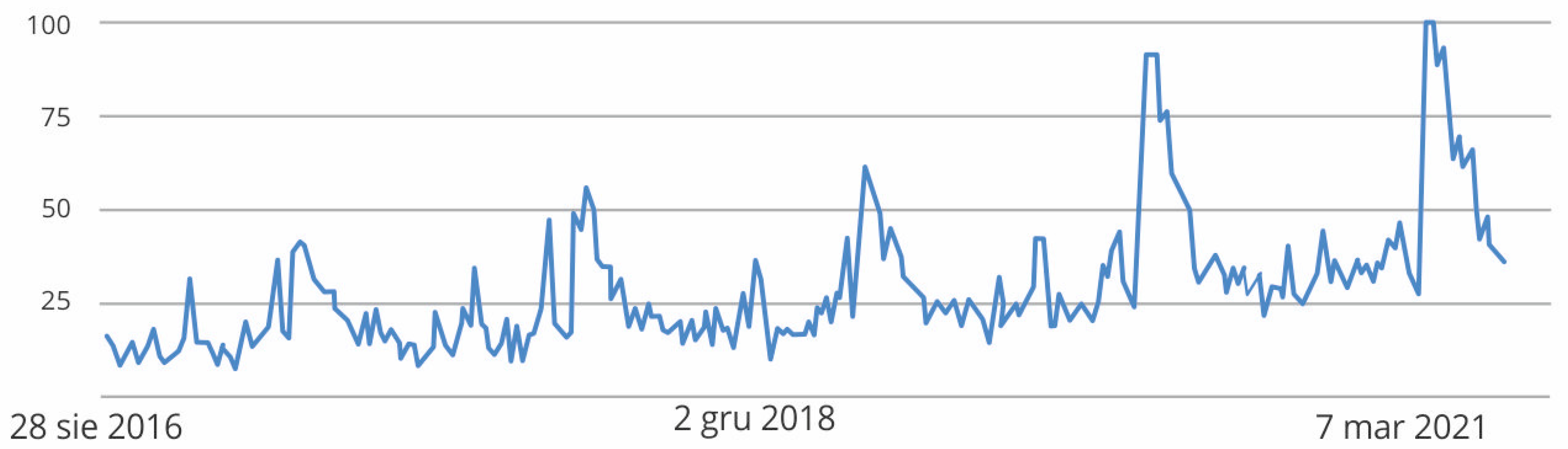

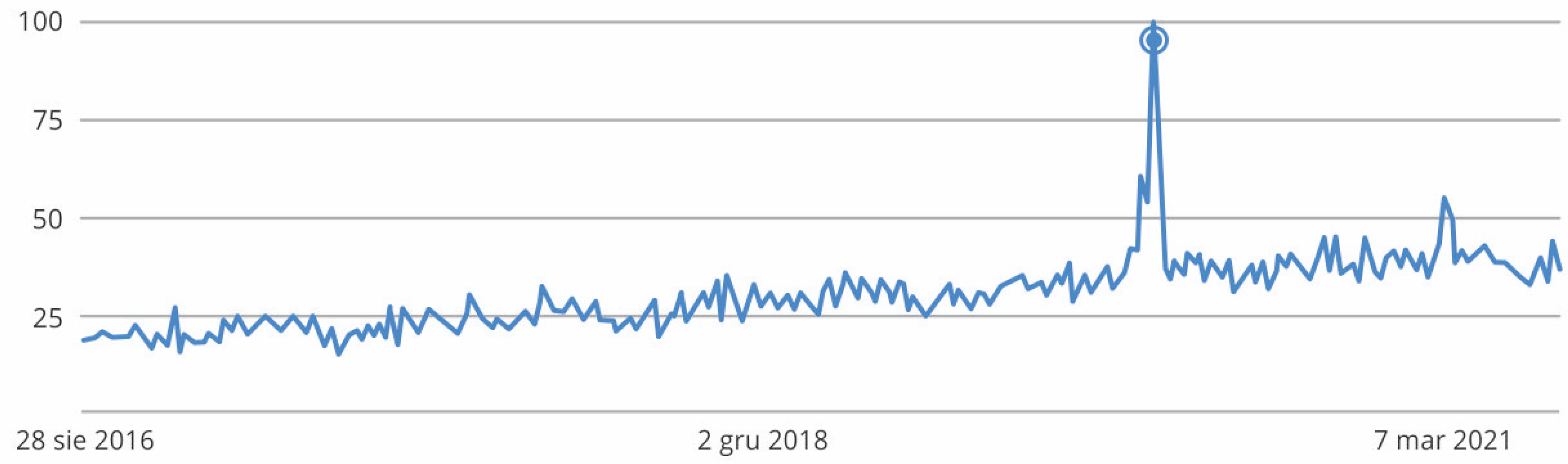

3.6. Keyword Observation: “prophecy” (Polish: “przepowiednia”)

4. Conclusions

- The tendency for increased interest in the topic of prayer on the Internet, indicated by Bentzen (Bentzen 2020; Bentzen 2021), is reflected in the Polish-language Internet. The results essentially overlap with those obtained by Bentzen.

- The study shows that in addition to general queries such as “prayer”, Internet users also made specific, detailed searches. This can be seen in the increased interest in queries such as “litany” or “The Call of Jasna Góra”. On the other hand, we can see less interest in confession, probably due to its non-availability but also, perhaps, because of a fear of infection. This area is open to possible in-depth research.

- Certain factors may have created information overload and influenced the results shown in Google Trends; this can be seen in the increased frequency of the search for the food blessing prayer—the question is whether it was more a result of an attachment to tradition or the need to pray.

- The interest in prayer during the COVID-19 pandemic did not mean increased interest in prophecies and predictions. While moments of collective trauma, such as the death of John Paul II or the Smolensk disaster, have generated such interest, it was hardly evident in the initial phase of the pandemic.

- Although it is difficult to put into statistical models, there is a noticeable connection between the popularity of particular queries and religiosity in a given region of Poland, which is reflected in secondary data (annual surveys conducted by the Institute of Catholic Church Statistics in Poland—ISKK). The frequency of search queries about prayer coincided geographically with the data on the religiosity of Poles. In contrast, interest in prophecies and predictions was higher in areas with lower levels of religiosity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamczyk, Amy, Yu-Hsuan Liu, and Jacqueline Scott. 2021. Understanding the role of religion in shaping cross-national and domestic attitudes and interest in abortion, homosexuality, and pornography using traditional and Google search data. Social Science Research 100: 102602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aten, Jamie D., Wendy R. Smith, Edward B. Davis, Daryl R. Van Tongeren, Joshua N. Hook, Don E. Davis, Laura Shannonhouse, Cirleen DeBlaere, Jenn Ranter, Kari O’Grady, and et al. 2019. The psychological study of religion and spirituality in a disaster context: A systematic review. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 11: 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babich, Lyubov. 2019. Internet as a Source of Information and Knowledge: Reality and Prospects. Koper, Izola, and Portorož: University of Primorska Press, pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Barreau, Jean Marc. 2021. Study of the Changing Relationship between Religion and the Digital Continent—In the Context of a COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 12: 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloc, Marianna, Francesco Drago, and Roberto Galbiati. 2016. Earthquakes, religion, and transition to self-government in Italian cities. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 1875–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding. 2019. Acts of God? Religiosity and natural disasters across subnational world districts. The Economic Journal 129: 2295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, Jeanet. 2020. Rising Religiosity as a Global Response to COVID-19 Fear. Available online: VoxEU.org (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding. 2021. In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 192: 541–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boguszewski, Rafał, Marta Makowska, Marta Bożewicz, and Monika Podkowińska. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Religiosity in Poland. Religions 11: 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożewicz, Marta. 2020a. Raport CBOS Religijność Polaków w ostatnich 20 latach. Available online: https://cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2020/K_063_20.PDF (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Bożewicz, Marta. 2020b. Raport CBOS Wpływ pandemii na religijność Polaków. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2020/K_074_20.PDFcbos.pl (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Bożewicz, Marta, and Rafał Boguszewski. 2021. The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Catalyst for Religious Polarization in Poland. Religions 12: 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabak, Joanna. 2020. Nowe wspólnoty religijne na Instagramie. Studium przypadku wybranych profili. Media i społeczeństwo, Akademia Techniczno-Humanistyczna, Bielsko-Biała 12: 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Całek, Grzegorz. 2020. Google Trends jako narzędzie użyteczne dla badaczy niepełnosprawności. Studia Humanistyczne AGH 19: 177–192. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=942994 (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2005. Spiritualising the Internet. Uncovering Discourses and Narratives of Religious Internet Usage. Online-Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 1: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office. 2021. Społeczeństwo informacyjne w Polsce w 2021 roku. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/nauka-i-technika-spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne-w-polsce-w-2021-roku,2,11.html (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Chester, David K., and Angus M. Duncan. 2010. Responding to disasters within the Christian tradition, with reference to volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. Religion 40: 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Public Opinion Research. 2011. Poles towards Some New Age Views. Report from Research BS/135/2011. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2011/K_135_11.PDF (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Center for Public Opinion Research. 2018. What the Future Brings—About Horoscopes, Fortunetellers and Talismans. Report from Research 103/2018. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2018/K_103_18.PDF (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Elhussein, Mariam, Samiha Brahimi, Abdullah Alreedy, Mohammed Alqahtani, and Sunday O. Olatunji. 2020. Google trends identifying seasons of religious gathering: Applied to investigate the correlation between crowding and flu outbreak. Information Processing and Management 57: 102208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhruroji, Moch. 2019. Muslims Learning Islam on the Internet. In Handbook of Contemporary Islam and Muslim Lives. Edited by Woodward Mark and Ronald Lukens-Bull. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Matthew, Mariel K. Goddu, and Frank C. Keil. 2015. Searching for explanations: How the Internet inflates estimates of internal knowledge. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 144: 674–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, Matthew, Adam H. Smiley, and Tito L.H. Grillo. 2021. Information without knowledge: The effects of Internet search on learning. Memory 8: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Michael. 2017. Big Data, Ethics and Religion: New Questions from a New Science. Religions 8: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Głowacki, Antoni. 2019. Raport CBOS Oceny sytuacji Kościoła katolickiego w Polsce. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2019/K_101_19.PDF (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Gonera, Marcin. 2020. Funkcjonowanie Kościoła katolickiego w Polsce w czasie pandemii koronawirusa. Com.pess 2: 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gralczyk, Aleksandra. 2021. COVID 19 Online Learning Experience as Starting Point for Media Competence Development. Kultura-Media-Teologia 48: 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Elliot D. 2018. Using Google trends to measure ethnic and religious identity in sub-Saharan Africa: Potentials and limitations. Africa at LSE 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg, Jeremy, Matthew H. Mohebbi, Rajan S. Patel, Lynnette Brammer, Mark S. Smolinski, and Larry Brilliant. 2009. Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature 457: 1012–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, Damian. 2015. Mediatyzacja religii: Analiza pojęcia″. In Przestrzenie Komunikacji: Technika, Język, Kultura. Edited by E. Borkowska, A. Pogorzelska-Kliks and B. Wojewoda. Gliwice: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej, pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Guzek, Damian. 2016. Media Katolickie w Polskim Systemie Medialnym. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Hongping, Li Tang, Shuhua Zhang, and Haiyan Wang. 2018. Predicting the direction of stock markets using optimized neural networks with Google Trends. Neurocomputing 285: 188–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAB Polska. 2021. Raport Strategiczny INTERNET 2020/2021. Available online: https://www.iab.org.pl/baza-wiedzy/raport-strategiczny-internet-2020-2021/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Institute for Catholic Church Statistics. 2020. Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia AD 2020. Warsaw: Institute for Catholic Church Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Janc, Krzysztof, Konrad Czapiewski, and Marcin Wójcik. 2019. In the starting blocks for smart agriculture: The internet as a source of knowledge in transitional agriculture. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 90: 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffres, Leo W., Kimberly Neuendorf, and David J. Atkin. 2012. Acquiring Knowledge From the Media in the Internet Age. Communication Quarterly 60: 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Seung-Pyo, Hyoung Sun Yoo, and San Choi. 2018. Ten years of research change using Google Trends: From the perspective of big data utilizations and applications. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 130: 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek-Śliwińska, Monika, Gabriela Piechnik-Czyż, Anna Jupowicz-Ginalska, Iwona Leonowicz-Bukała, and Andrzej Adamski. 2022. Social Media Marketing in Practice of Polish Nationwide Catholic Opinion-Forming Weeklies: Case of Instagram and YouTube. Religions 13: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Simon. 2021. Digital 2021: Poland. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-poland (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Kimhi, Shaul, Yohanan Eshel, Hadas Marciano, Bruria Adini, and George A. Bonanno. 2021. Trajectories of depression and anxiety during COVID-19 associations with religion, income, and economic difficulties. Journal of Psychiatric Research 144: 389396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, Orhan. 2021. How Does Religious Commitment Affect Satisfaction with Life during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Examining Depression, Anxiety, and Stress as Mediators. Religions 12: 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Oliver. 2004. The Internet as Distributor and Mirror of Religious and Ritual Knowledge. Asian Journal of Social Science 32: 183–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, Didem, and Ahmed C. Kurt. 2021. Does Religion Have Relevance for Individual Tax Behavior in the U.S.? Evidence from Online Search and Chatter Activity. The Journal of Consumer Affairs 55: 821–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonowicz-Bukała, Iwona, Andrzej Adamski, and Anna Jupowicz-Ginalska. 2021. Twitter in Marketing Practice of the Religious Media. An Empirical Study on Catholic Weeklies in Poland. Religions 12: 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Mac Zewei, and Shengquan Ye. 2021. The role of ingroup assortative sociality in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multilevel analysis of google trends data in the United States. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 84: 168–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, Józef, and Marta Kokoszczyńska. 2020. Religia-Media–Popkultura. Warszawa: Towarzystwo Więź. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, Mateusz. 2021. Wykorzystanie Google Trends do modelowania stopy bezrobocia rejestrowanego w Polsce. Wiadomości Statystyczne. The Polish Statistician 66: 45–61. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=945476 (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Mavragani, Amaryllis, and Gabriela Ochoa. 2019. Google Trends in Infodemiology and Infoveillance: Methodology Framework. JMIR Public Health Surveill 5: e13439. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.1207745 (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Micó-Sanz, Josep-Lluís, Miriam Diez-Bosch, Alba Sabaté-Gauxach, and Verónica Israel-Turim. 2021. Mapping Global Youth and Religion. Big Data As Lens to Envision a Sustainable Development Future. Tripodos 48: 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadali, Noor Azizah. 2015. Exploring awareness and perception on palliative care—Internet as source of knowledge. Advanced Science Letters 21: 3367–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccarato, Alessia, Stefano Falorsi, Silvia Loriga, and Andrea Pierini. 2018. Combining official and Google Trends data to forecast the Italian youth unemployment rate. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 130: 114–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzielska, Ewelina. 2018. Wykorzystanie Google Trends do predykcji stopy zwrotu indeksu WIG20. Ekonomia XXI Wieku. p. 19. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=765537 (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald F. Inglehart. 2008. Existential Security and the Gender Gap in Religious Values. Available online: https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/fs/pnorris/Acrobat/SSRC%20The%20gender%20gap%20in%20religiosity%20Norris%20and%20Inglehart%20%233.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Pace, E. 2021. Religious Minorities in Europe: A Memory Mutates. Religions 12: 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2021. More Americans than People in Other Advanced Economies Say COVID-19 Has Strengthened Religious Faith. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2021/01/27/more-americans-than-people-in-other-advanced-economies-say-COVID-19-has-strengthened-religious-faith/ (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Piasecki, Paweł. 2021. Kantar zbadał, jak uczymy się za pomocą YouTube’a. Available online: https://mmponline.pl/artykuly/254210,kantar-zbadal-jak-uczymy-sie-za-pomoca-youtube-a (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Pirutinsky, Steven, Aaron D. Cherniak, and David H. Rosmarin. 2020. COVID-19, Mental Health, and Religious Coping Among American Orthodox Jews. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preis, Tobias, Helen Susannah Moat, and H. Eugene Stanley. 2013. Quantifying Trading Behavior in Financial Markets Using Google Trends. Scientific Reports 3: 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Przywara, Barbara, Andrzej Adamski, Andrzej Kiciński, Marcin Szewczyk, and Anna Jupowicz-Ginalska. 2021. Online Live-Stream Broadcasting of the Holy Mass during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland as an Example of the Mediatisation of Religion: Empirical Studies in the Field of Mass Media Studies and Pastoral Theology. Religions 12: 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P. Clint, and Scott L. Howell. 2009. Religion and Online Learning. In Encyclopedia of Distance Learning, 2nd ed. Edited by Patricia Rogers, Gary Berg, Judith Boettcher, Caroline Howard, Lorraine Justice and Karen Schenk. Hershey: IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, Betsy, Jenny Liu, and Daniel M. Wegner. 2011. Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science 333: 776–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stachowska, Ewa. 2017. Mediatyzacja religii w Polsce. Wybrane aspekty w koncepcji S. Hjarvarda. Uniwersyteckie Czasopismo Socjologiczne 2017: 41–55. Available online: http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-bc1b8968-e8aa-481b-8863-4b78df80e7e2 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Świtoniak, Marcin, Dawid Augustyniak, and Przemysław Charzyński. 2018. The internet as a source of knowledge about soil cover of Poland. Bulletin of Geography. Physical Geography Series 14: 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tkachenko, Nataliya, Sarunkorn Chotvijit, Neha Gupta, Emma Bradley, Charlotte Gilks, Weisi Guo, Henry Crosby, Eliot Shore, Malkiat Thiarai, Rob Procter, and et al. 2017. Google Trends can improve surveillance of Type 2 diabetes. Scientific Reports 7: 4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Topidi, K. 2019. Religious Freedom, National Identity, and the Polish Catholic Church: Converging Visions of Nation and God. Religions 10: 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vishal, S. Arora, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler. 2019. Google Trends: Opportunities and limitations in health and health policy research. Health Policy 123: 338–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, Abigail, Claire Hopkins, and Pavol Surda. 2020. Use of Google Trends to investigate loss-of-smell–related searches during the COVID-19 outbreak. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology 10: 839–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wanat, Gabriela. 2022. Leading Internet Search Engines in Poland in January 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1086209/poland-leading-search-engines (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Wanner, Philippe. 2021. How well can we estimate immigration trends using Google data? Qual Quant 55: 1181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Adrian F. 2021. People mistake the internet’s knowledge for their own. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118: e2105061118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzała, Paweł. 2016. Google Trends jako narzędzie badawcze w dziedzinie edukacji specjalnej. In Specjalne potrzeby edukacyjne. Wspomaganie rozwoju – wielość obszarów wspólnota celów. Edited by Barbara Grzyb and Gabriela Kowalska. Gliwice: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324170730_Google_trends_jako_narzedzie_badawcze_w_dziedzinie_edukacji_specjalnej (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Yelowitz, Aaron, and Mathew Wilson. 2015. Characteristics of Bitcoin users: An analysis of Google search data. Applied Economics Letters 22: 1030–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeung, Timothy Yu-Cheong. 2019. Measuring Christian Religiosity by Google Trends. Review of Religious Research 61: 235–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yuzhou, Hilary Bambrick, Kerrie Mengersen, Shilu Tonga, and Wenbiao Hu. 2018. Using Google Trends and ambient temperature to predict seasonal influenza outbreaks. Environment International 117: 284–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stańdo, J.; Piechnik-Czyż, G.; Adamski, A.; Fechner, Ż. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Interest in Prayer and Spirituality in Poland According to Google Trends Data in the CONTEXT of the Mediatisation of Religion Processes. Religions 2022, 13, 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070655

Stańdo J, Piechnik-Czyż G, Adamski A, Fechner Ż. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Interest in Prayer and Spirituality in Poland According to Google Trends Data in the CONTEXT of the Mediatisation of Religion Processes. Religions. 2022; 13(7):655. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070655

Chicago/Turabian StyleStańdo, Jacek, Gabriela Piechnik-Czyż, Andrzej Adamski, and Żywilla Fechner. 2022. "The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Interest in Prayer and Spirituality in Poland According to Google Trends Data in the CONTEXT of the Mediatisation of Religion Processes" Religions 13, no. 7: 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070655

APA StyleStańdo, J., Piechnik-Czyż, G., Adamski, A., & Fechner, Ż. (2022). The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Interest in Prayer and Spirituality in Poland According to Google Trends Data in the CONTEXT of the Mediatisation of Religion Processes. Religions, 13(7), 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070655