Abstract

This paper attempts to examine the formation path of the United Temple. Since research on the United Temple has focused more on its organization and religious practice in contemporary Singapore, the paper looks at the sub-temples under the Singapore United Temple, analyzing their paths toward unification from a more extended historical perspective. The authors divide sub-temples into three categories: ancestral temples (血缘庙), geographic temples (地缘庙), and deity-related temples (神缘庙) and compare their flexible strategies. This paper tries to explain how the formation of the United Temples was influenced by multiple spatial, social, and cultural factors. The blood lineage, religion, and regional ties from the homeland could still be essential when the localized, community-based social links beyond the boundaries play an equally crucial integrative role in forming United Temples. It is the contention of the authors of this paper to study the United Temple—the unique religious space in Singapore—as the potential syncretic field of the present and the past.

1. Introduction

The United Temple is a temple form with Singaporean characteristics, and the creation of the United Temple is closely related to the urban re-development planning and land policy of Singapore in the 1970s.

Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, the population proliferated. Problems such as housing shortages and employment difficulties arose. The Housing and Development Board (HDB) for housing and the Economic Development Board (EDB) for industrial development were set up to address these two problematic issues. The most fundamental step in implementing their policy is the “expropriation of land”. In 1966, the Land Acquisition Act gave the government the right to acquire private land, including Chinese temple sites. Temples facing demolition can apply to the government for land for redevelopment; however, the price difference between the compensation and the new land is significant,1 and not only that, but most of the land leases are also only valid for 30 years and renewing the leases will pose a predictable challenge to the temples.

Most United Temples in Singapore are formed when a new temple gathers at least two old temples with a good believers’ base, financial means, and a desire to integrate, and jointly applies to the Housing and Development Board or the Jurong Town Council for a 30-year lease of land to build a new temple and raises funds to build the temple together after the land is acquired. As a result, the building pattern is generally one large temple on a jointly acquired site to accommodate the two or three participating temples (Ning 2016, p. 173).

However, the current scholarly research on joint temples is not comprehensive. Hue Guan Thye (Hue 2016, pp. 7–39; 2012, pp. 157–74) has dealt more systematically with the history and policy background of the development of the United Temples in Singapore and the main types. Soo Khin Wah (Soo 2008, pp. 205–23) explored the formation pattern of United Temples, starting from the naming characteristics of United Temples. Professor Kenneth Dean’s team at the National University of Singapore developed the SHGIS system to provide an efficient search platform for scholars of United Temple studies based on inscriptional literature and GIS as a framework (Yan et al. 2020, pp. 1–23). Most of the other studies are case studies: either from individual United Temples, such as Soo Khin Wah’s more basic overview of the development model of Tampines Chinese Temple: each temple adheres to its subjectivity and respects the dominance of Fu An Dian. Scholars have likewise made preliminary remarks on more typical temples such as Sengkang Joint Temple and Leng Hup San Chee Chea Temple. Alternatively, starting from the perspective of specific deity beliefs, they explore the religious networks of the Chinese original villages and temples, e.g., Zeng Ling (Zeng 2006a, pp. 97–127)2 explores the six surname temples in Peng Lai Si and discusses their links with Anxi in China, summarizing three features of the process of ‘sharing of incense’. More often than not, the discussion of joint temples is often attached to other Chinese faith issues. Zeng Ling (Zeng 2018, pp. 97–127) focuses on the relationship between ancestral deity worship and identity in United Temples. Lai Yu-Ju (Lai 2018, p. 126) focuses on the relationship between the surname temples of the Hokkien immigrants and the ancestral deity beliefs behind them and proposes three types of unions.3

As can be understood from the studies mentioned above on United Temples, most of the previous studies on the United Temple have focused on its type and composition, which are dominated by a single type of case study, lacking a more holistic long-term perspective. However, the United Temples are made up of different temples or shrines, and these once-independent units have their historical evolution and different ethnic and religious identities. Therefore, this article proposes research questions on the basis of previous research and based on the overall data of the United Temple in Singapore, hoping to increase the historical depth of the United Temple research. This article will start from the historical development and characteristics of each sub-temple unit, understand the process of different types of temples moving towards union, and the flexible changes and different strategic choices presented in this process, so as to give a richer and more comprehensive discussion on the study of United Temples.

For discussion, this article divides the temples under the United Temple into three main categories: the three main types of temples are broadly classified as ancestral temples (血缘庙), geographic temples (地缘庙), and deity-related temples (神缘庙). In this article, the term “ancestral temples” refers to temples that worship the “ancestral deity” of the ancestral hometown and maintain the same clan relationship with the ancestral hometown and the same family name.4 Scholars also use the term “surname temples” (姓氏庙) because their core members come from the same geographic area as their ancestral hometown and use the temple as a platform to unite their clansmen in the name of the “ancestral deities (祖神)” (Lai 2018, p. 126). There is no shortage of surname temples in Singapore established to unite the clansmen, and this article will follow the previous view and define temples that have formed the belief in ancestral deities through blood ties as “ancestral temples”.

Compared to ancestral temples, there is no clear definition of geographic temples. However, it is agreed that early Chinese immigrants had a strong identity with their place of origin and established their communities based on the geographic principle of their ancestral hometown and built their temples to worship the deities from their ancestral hometown to strengthen the territorial identity and unity of their communities (Chong 2007, pp. 110–11; Yen 1991a, pp. 33–35; Lawrence 1967, pp. 190–91). While the definition of geographic community formation among overseas Chinese can be broadly based on dialectal groups of provincial identity, most scholars use the county, town, or village of Chinese origin as the unit of distinction for a geographic community, as many geographic organizations and temples were founded at the county-level geographic identity community (Mak 1990, pp. 84–93; Soon 2016; Lawrence 1967, pp. 190–91). Thus, like ancestral temples, these geographic communities evoke a group identity with their ancestral hometowns by worshipping and sharing incense temples from their ancestral hometowns. In this paper, these temples are regarded as geographic temples linked by geographic temporal ties through the county level or below China.

As for deity-related temples, less attention has been paid to this concept in academic circles. Soon Hoh Sing points out that deity-related is the bond that links groups together in the form of religious or deity beliefs (Soon 2016). The definition is too broad, as all Chinese temples have the function of worshipping the deities, and they can all be called ‘deity-related organizations’, as Soo Khin Wah notes when summarizing the types of United Temples in Singapore, some temples are integrated through the relationship of the deity-related (the deities worshipped) (Soo 2008, pp. 215–16), indicating the deity-related dimension of the temple is also one of the elements that can impact the grouping of United Temples. However, the concept of the term “deity-related” should not be defined too loosely. Within the Chinese community in Singapore, there exist temples that do not exist to unite ancestral or geographic groups. These temples, which have the deities they worship as their core mission and use this as a link to unite their followers, can be referred to as deity-related temples. In Singapore, for example, the belief in Matsu has gained the devotion of people of all origins, and the temples dedicated to Matsu have formed a network of incense distribution beyond dialectal groups, clans, and occupational organizations (Hue 2017, pp. 6–8). Matsu temples (妈祖庙) are the most typical of these temples in that the primary deity they worship serves as the unifying link between the people and the temple’s mission, which is to serve the “deity”.

It is also important to note that the above distinction between ancestral, geographic, and deity-related origin for temples is not absolute. This is because many of the ancestral temples also have a certain degree of geographic relatedness, and some of the geographic temples are associated with deity-related by their dedication to specific deities. Therefore, the above distinction is not intended to be a rigid classification of sub-temples within the United Temples. More importantly, this article seeks to understand the specific role and influence of the different geographic, ancestral, and deity-related colors of the temples on the combination and changes in the United Temples. To better implement this study, a comparative study of different case studies will be conducted to show the diverse integration strategies and development choices of different types of temples according to their ancestral, geographic, and deity-related affiliations to understand how the formation of the United Temples was influenced by multiple historical factors such as indigenous-local, faith-based-secular and community network–cross-community network.

2. Ancestral Temple

The agnatic clanship system is an essential part of the local social structure of southern China, and with the migration chain from the southeastern coast of China, the lineage organization based on blood has become one of the primary forms of social organization among the overseas Chinese community.Yen Ching-Hwang suggests that the core difference between the localized lineage organizations and simplex dialectal, regional, and non-regional clan groups exists in the specific qualification of genealogy, ancestry, and villages of origin (Yen 1991a, pp. 67–86).5 The “ancestral temple” discussed in this article is also identified as the “surname temple,” which refers to temple worship “ancestral deity” branched from the hometown village, and the member maintains alliance based on the same village (or district) and blood lineage tie.6

In the context of Singaporean and Malaysian Chinese studies, the meaning of “ancestral deity worship” is more inclusive than that of Min (闽) and Taiwanese societies. However, it still represents the “blood commonality” of local clan members and their cultural connection to their ancestral homeland from a fundamental point of view. As a place of practice of ancestral worship, the ancestral temple is not only a symbol of clan identity but also a spatial entity that carries the historical and cultural memories of both the village of the ancestral homeland and the life of the local community.7 In response to Singapore’s urbanization, some ancestral temples have also undergone re-integration or chosen to create new unions, and the multiple socio-cultural elements inherent in ancestral temples—such as clan formations and belief systems in the villages of origin, localized communities, and social networks—can influence the unification strategies of ancestral temples and together shape their outcomes. The following section focuses on three clan group ancestral temples, and by presenting their development in their native villages and local societies, we understand the different paths ancestral temples took towards union.

2.1. Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan: Weng Shan Hong (翁山洪) Clan Ancestral Temple towards the Merger

Established in 1983, the “Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan” (水沟馆葛岸馆) in Singapore is a joint temple formed by several ancestral temples belonging to “Weng Shan Hong”. The “Weng Shan Hong” refers to the patriarchal lineage with the surname ‘Hong’, whose ancestral home is Ying’du Township (英都镇), Nan’an County (南安县), Quanzhou (泉州), and the Ying’du Hong is called “Weng Shan Hong” because of the cousin name “Wu Rong Weng Shan” (武荣翁山). According to Weng Shan Genealogy (《翁山谱志》), Hong’s lineage in Ying’du was divided into East and West Wings (xuan轩) and from which eight sub-branches (fang房) were derived.

After the early Ming dynasty, The East Xuan and West Xuan of the Hong Clan of Weng Shan began to scatter in the different natural villages of Yingdu, gradually becoming the most dominant population in Yingdu town (Hong 2006). The town of Yingdu is a basin with a dense distribution of natural villages; thus, creating an integral space for lineage settlement. The different sub-branches of Weng Shan Hong have built their ancestral hall in their settlement village, while still maintaining close ties as a whole. In 1993, the Hong’s biggest ancestral hall in Yingdu was rebuilt, with the Hong clan temple dedicated to the first ancestor in the center and the East Xuan and West Xuan ancestral halls on the left and right, and the clan still participated in the spring and autumn festivals.8

Similar to the clan system, the temple system of Weng Shan Hong manifests itself as one center and several clan branches. In the late Ming dynasty, the Hong Clan built Swee Kow Kuan in Rongxing Village, Ying Du Town in the present day, to worship the four kings of Liu, She, Lei, and Pan, and used it as a village school for the whole Hong clan, and Swee Kow Kuan later became not only the combined temple of the Hong clan in Weng Shan but also the area temple in Yingdu Town.9 In addition to the Swee Kow Kuan, which was built as a United Temple, each clan branch built its house-head or corner-head temples in the natural villages where they lived. One such temple is the Kueh Hua Kwan at Kueh Hua Fang (葛岸坊), Min Shan Village (民山村), Yingdu Town. The temple was built during the Kangxi (康熙) period and is dedicated to the princes of the three provinces of Zhu, Guillermo, and Li. It is located next to the ancestral house of Kueh Hua and belongs to the 15th generation of the West Second Branch of the Hong Clan Clan of Weng Shan (Nan’an: Yingdu Kueh Hua Kwan Tekan Bianweihui 2006, p. 7).

Before the 1980s, several ancestral temples were built by the Hong Clan in East and West Huan Weng Shan in Singapore, namely: He Sheng Guan (和升馆) (later renamed Swee Kow Kuan) in Chua Chu Kang; Swee Kow Kuan in Lao Ba Village (老芭村), 11th mile from Yio Chu Kang; “Kueh Hua Kwan” in Wu Xian Dian Village (无线电村), 9th mile from Yio Chu Kang, and “Swee Kow Kuan” in Bah Soon Pah Village, 11th mile from Yishun Sembawang Road (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Hong Clan Ancestral temple at Weng Shan, Singapore.

The earliest Swee Kow Kuan in Singapore was the He Sheng Guan Wu Wang Fu Ye Qing Miao, built in 1905 in North Buona Vista. It was relocated to Holland Road later in 1920 and renamed after the original village ancestral temple. In 1967, the Holland Road Swee Kow Kuan was again moved to the village of Nei Dong Cheng village, 12½ miles from Chua Chu Kang. In 1992, a temple called the Swee Kow Kuan in Nei Dong Cheng village, Chua Chu Kang, together with the nearby Choa Chu Kang Tao Bu Keng, Chua Chu Kang Chin Long Kong, Tian Yun Miao, and San Zhong Gong, purchased the temple on Teck Whye Lane and established the Chua Chu Kang Lian Sing Keng, although there is no conclusive evidence of a direct link between the two Swee Kow Kuan.

It is noteworthy that there was also a Swee Kow Kuan in Jurong West, 10th Mile from Ying Du Town, where the incense was distributed. It was established in 1949, and in 1985 it joined forces with the Ling Jin Tang, Xi Shan Gong, Long Xu Yan, Guan Shan Dian, and Qiong Yao Jiao Di, located in Jurong 10th Mile, to establish Jurong Combined Temple. There are indeed two ancestral temples in Jurong Combined Temple (Table 2), but the Swee Kow Kuan is not one of them. According to the Brief History of Ling Jin Tang (《灵晋堂简史》) inscribed in the Jurong Combined Temple, the early directors of the Swee Kow Kuan in Jurong were Nan’an residents Cai De Lai and Toh Ya Cai, and after their deaths, the two temples were dedicated to Lord Jin, who is now under the management of the same council. The Ling Jin Tang originated from Dongshan Village, Xiangun Town, Nan’an County (adjacent to Ying Du Town), and the Council was composed of immigrants from Xiangun Town with the surnames Liang, Wang, and Toh and was not owned by the Hong Clan of Weng Shan. In the case of Jurong Combined Temple, the dual nature of the original township Swee Kow Kuan’s ancestral temple and the geographic temple is another expression of the complexity of the overseas Chinese ancestral temple system.

Table 2.

Jurong Combined Temple ancestral temple.

There were two of Hong’s ancestral temples in Yio Chu Kanm, namely Swee Kow Kuan and Kueh Hua Kwan, the two temples are located less than two kilometers away from each other. The founders of the two temples remain unknown, but they respectively belonged to a different branch of Wengshan Hong immigrants—Swee Kow Kuan was identified under the East branch and Kueh Hua Kwan under the West.

In 1976, the government expropriated the land of both Swee Kow Kuan and Kueh Hua Kwan in Yio Chu Kang, and the two temples decided to merge. In 1978, members of the Hong Clan in Yio Chu Kang jointly purchased a house at 47 Joon Hiang Road to house them, and in the following year, the company was registered as a joint-stock company, Weng Shan Society Limited, to manage the Swee Kow Kuan and Kueh Hua Kwan. However, the government soon informed them that the house at 47 Joon Hiang Road could not be used as a temple. In 1980, the land at Ang Mo Kio 67 was granted to “Swee Kow Kuan,” and the hall was registered as a society under “Swee Kow Kuan Temple”. In 1985, when Swee Kow Kuan in Sembawang district was also affected by the land policy, it donated all the funds to join Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan. At this point, the only two ancestral temples of the Weng Shan Huang remained in Singapore, they were Swee Kow Kuan and Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan in Choa Chu Kang Nei Dong Cheng village.

In May 1983, ANG Keong Lan, the Chairman of the Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan, said in his instructions that “the dates of the performances in this temple must be determined in advance, and if there are any performances in other temples, they must contact us.” It can be seen that at the early stage of its establishment, Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan maintained contact with other Hong Clan’s ancestral temples in Singapore (Singapore: Shuigou Ge’an’guanmiao 1986, pp. 47, 56, 143).

ANG Keong Lan, the prominent merchant and the chairman of the temple, made a vital contribution to the consolidation and development of Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan. In 1978, ANG Keong Lan’s contribution of Singapore Dollars 180,000 enabled the Hong Clan clan to purchase a house on Joon Hiang Road in Yio Chu Kang as the site for Yio Chu Kang’s Swee Kow Kuan and Kueh Hua Kwan. In 1979, the Hong clan established the “Weng Shan Society Limited,” with 334 people subscribing for shares (one dollar per share) totaling 471,604 shares, of which ANG Keong Lan alone accounted for 180,000 shares.10 At the same time, ANG Keong Lan was an essential member of the Nanyang Ang Clan Guild and built the link between Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan and Nanyang Ang Clan Guild.

Nanyang Ang Clan Guild is a cross-dialect group association based on a virtual common ancestor, with members from all parts of the Quanzhou, including Nan’an, Jinjiang, and Tong’an. At the same time, Nanyang Ang Clan Guild also traces its common ancestry to the “Liu Kwee origins” (六桂渊源) and has a Liu Kwee Tang with five other surnames (Jiang, Weng, Fang, Gong, and Wang) (Singapore: Nanyang Ang Clan Guild 1973, p. 134). Nowadays, the office of Liu Kwee Tang is located in a multi-story building behind the main hall of Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan. As Khee Heong Koh and Chang Woei Ong argue, the “Nanyang Ang Clan Guild” was not an exclusive clan organization, and the lineage identity of the Weng Shan Hong was still nested within the temple (Khee and Chang 2014, pp. 3–32). However, the connection with the Guild House still extends the influence and social network of Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan.

The distinction between the East and West Houses has been maintained within Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan, and in Singapore, Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan has been divided between the “East Xuan” and “West Xuan” clans of the Weng Shan Hong.11 However, as a whole, Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan has become the most representative clan identity symbol of the Weng Shan Hong clan in Singapore and an essential link between the Weng Shan Hong clan and their ancestral clan in Singapore.

In 1983, the Weng Shan Hong in China completed their renewal lineage genealogy as the Weng Shan Hong clan (《翁山谱序》), the genealogy included both the East and West Wings in China and overseas (Singapore: Shuigou Ge’an’guanmiao 1986, p. 51). In 2005, the Singapore National Archive excavated the stone stele of the “He Sheng Guan Wu Wang Fu Ye Qing Miao” in North Buona Vista, which details the reasons for the Hong clan’s donation to build the “He Sheng Guan” in Guangxu (光绪), 31st year (1905). The stone tablet is now in the custody of Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan.12

2.2. Teong Siew Kuan (长秀馆) and Hong Leng Yien Temple (云龙院): Two Paths of Yun Feng Toh’s Ancestral Temple

According to the genealogy of the Yun Feng Toh lineage (云峰卓), the ancestors of the Toh Clan moved to Yuntou (now Yunshan Village, Xiangyun Town, Nan’an County) with their family during the Hongwu period and obtained a household registration, while Yuntou was located at the northern foot of Yun Feng Mountain in Nan’an, so it was called the ‘Yun Feng TohClan’ (Nan’an Futing Village 1893).

During the Hongzhi period of the Ming Dynasty, the fourth longhouse of the Yun Feng TohClan moved to Fuyouting (福佑庭) (now Fu’ting Village福庭村), and then the various house lines of the Yun Feng TohClan went through complex divisions due to internal differences. In the early years of the Qing dynasty, the Yun Feng Tohclan not only had “their ancestral shrines” but also had “different clans” and “different ancestors but one clan”. In the 45th year of the Kangxi era, the Yun Feng Tohclan’s ancestral shrine was the subject of a dispute over its grave, which lasted until around the fifth year of the Jiaqing (嘉庆) period (Nan’an Futing Village 1893; Nan’an: Fujian Nan’an Xiangyun Yunfengclan Branch 2001). Eventually, the Yun Feng Toh was gradually divided into two main branches, the “Yuntou Yangshi” (also called “External Toh外卓”), which lived in the natural villages of Xiangshan, Yuntou, and Yunshan in Xiangyun town, and the “Futing Yangshi” (called “Internal Toh内卓”), which lived in Futing village. The Yun Feng Toh has Three Lords Toh (‘Toh Fu San Wei Da Ren’卓府三位大人, also known as the Three Ancestors, divided into the Great Ancestor, the Second Ancestor, and the Third Ancestor) as its ancestral deities (known as the Ancestor Deity),13 and the two clans have their ancestral shrines, genealogies, and temples.

In the 1930s, the Yun Feng Toh clansman came south to Singapore and built ancestral temples to worship Toh Fu Da Ren, including Yun Feng Kuan in Yio Chu Kang, Soon Huat Toh Hoon Leng Yien in Keng Lee Road, Hock San Yuan Hoon Leng Yien in present-day Yishun District, Jurong West Toh Fu Hall and Teong Siew Kuan in Jalan Hwi Yoh.14 Teong Siew Kuan was distinct from the rest as it is the only temple that belonged to the Internal Toh ‘内卓’ (Table 3).

Table 3.

Toh Clan Ancestral temple, Yun Feng, Singapore.

After combinations, the only surviving buildings are Hoon Leng Yien and Teong Siew Kuan in Keng Lee Road.

The Hoon Leng Yien on Keng Lee Road was built in the early 20th century, dedicated to the ancestors of Qing Shui Zu Shi and Toh Fu San Wei Da Ren (Ancestor Deity). Its construction site was donated by Toh clan merchant Toh Kehe (卓克盒). In 1984, Keng Lee Road Hoon Leng Yien was approved by government to register as “Hoon Leng Yien (Temple) Co., Ltd.” in original adress in order to manage temple’s fund. (Singapore: Nanyang Toh Clan Association 1999, p. 55). In 1991, the land of Yio Chu Kang (Liu Xun) Yun Feng Kuan, and Hock San Yuan Hoon Leng Yien (Chia Chwee Kang 淡水港) were requisitioned by the government and disbanded.

The affected temples soon combined with Hoon Leng Yien instead in Ang Mo Kio (Lianhe Zaobao 1991, p. 20). Hoon Leng Yien mainly worships two groups of deities: one is the ancestor of Qing Shui Zu Shi, and the other is Toh Fu San Wei Da Ren (Ancestor Deity). It is the only temple to be worshipped by the External Toh (外卓) clansman.15

Teong Siew Kuan used to be called Yun Quan Kuan (云泉馆). It was built in early 1913 in the village of Jalan Hwi Yoh (now the second Ang Mo Kio Industrial Park) by the Fu Ting Internal Toh clansman of Xiang Yun Town, who shared the incense with their ancestral temple “Yun Mei House”. In 1986, Teong Siew Kuan applied to the Government for registration as an independent society, and the temple site was acquired in December of the same year. The Government allocated a new temple site in Yishun to the Teong Siew Kuan and shared the land purchase cost with the two Fujian temples, Wei Ling Keng and Dong Shan Temple. In 1988, it was registered with Wei Ling Keng and Dong Shan Temple as “Teong Siew Wei Ling Dong Shan Temple” to prepare for the construction of the joint temple. The joint temple was completed in 1990, with the three temples sharing the land but each having its building (Singapore: Nanyang Toh Clan Association 1999, p. 56). At present, Teong Siew Kuan is still the center of the clan activities of the Futing Clan of the Yun Feng Toh Clan: Toh Fu San Wei Da Ren is the principal deity, and the ancestral tablets of the Toh Clan from the Futing village (“Lotus tablets of the ancestors of the West River Clan of the Toh Clan”) (“卓氏门中西河衍派历代祖考祖妣莲位”) are also enshrined. In 1992, Teong Siew Kuan also took the lead in restoring the genealogy of the Futing Clan.

Unlike the case of the Weng Shan Hong Clan, Yun Feng Toh’s ancestral temple in Singapore is clearly defined as “internal” and “external,” with the two clan branches choosing two different paths of development to maintain their separate clan spaces.

In 1939, Toh Kim Soo (卓金树), the merchant and the leading member of Yun Feng inYio Chu Kang initiated organizing Nanyang Toh Clan Association at Beach Road (美芝路). Additionally, in 1958, External Toh formed Hoon Hong Hiap Chin Sia (云峰协进社) in the Yio Chu Kang for neighboring clansmen. In 1991, two clan associations belonging to the same Yun Feng Toh merged and were officially registered as Toh Clan General Association Singapore in 1997 (Singapore: Nanyang Toh Clan Association 1999, p. 28).

When Teong Siew Kuan was faced with land acquisition, the heads of Teong Siew Kuan and Hoon Leng Yien had discussed merging the two temples into one, but this eventually did not materialize due to the consideration of the division of the house faction of the clan in the original village. However, some members of Hoon Leng Yien and Teong Siew Kuan were involved in the operation of the Association and participated in the activities of the Association in the name of the temple. For example, in 1995, Nanyang Toh Clan Association elected representatives to raise SGD 140,000 for the renovation of the Toh’s Ancestral Hall in Quanzhou, and the Singapore Hoon Leng Yien and Teong Siew Kuan donated SGD 5000 and SGD 3000, respectively, to help fund the renovation (Singapore: Nanyang Toh Clan Association 2001, pp. 47–71). The year of 2019 saw the establishment of a scholarship for Toh clan members funded by the Hoon Leng Yien and Teong Siew Kuan at the Nanyang Toh Clan Association. In general, the two Toh ancestral temples are not directly affiliated with Toh Clan General Association Singapore and have limited cooperation.

2.3. Longxuyan Jinshuiguan (龙须岩金水馆) and Long Quan Yan (龙泉岩): The Reorganization and Respective Union of the Xiangyun Ong (象运王氏) Ancestral Temples

The Xiangyun (象运) Wang clan’s ancestral home in Singapore is Xiang Yun Township (翔云镇), Nan’an County (南安县), Quanzhou. According to Nan’an Xiangyun Ong Shi Jia Cheng (《南安象运王氏家乘》) records, during the Ming Dynasty Jingtai (景泰) period, the first-generation ancestor, Wan Xun Gong (万逊公), led his sons to settle in Anzhong village (安中村) in Xiangyun town; during the Zhengde (正德) period, some members moved to Huangtian Village (黄田村) and built a clan temple. Since then, the Ong clan has mainly lived in Anzhong (or Jinbing (金炳), the present-day Jin’an village (金安村) and Huangtian (the present-day Huangtian village), known as the Anzhong and Huangtian clan branches. The two groups of Wang clan members lived in similar natural villages and always maintained the clan identity of the Xiangyun Ong clan. From the Kangxi (康熙) period and the early 20 century, the two sub-lineage branches of the Huangtian and Anzhong collaborated on five occasions to rebuild their genealogies and ancestral halls (Nan’an: Xiangyun Ong Shi Zupu Xiuzhuan Weiyuanhui 2017). At the same time, the Huangtian branch continued to revise the genealogy of the “Nan’an Xiangyun Huangtian Wang Clan” (南安象运黄田王氏), and the two branches of Ong lineage had their genealogy and temple system.

Huangtian Village is a single surname village of the Wang clan. In Guangxu (光绪) 31st year (1905), the ancestors of the Wang clan built the “Long Quan Yan” at the highest point of Huangtian village to worship the ancestors of Qing Shui Zu Shi (清水祖师) and Zhang Gong Sheng Jun (张公圣君).16 The Jin’an village, on the other hand, is a multi-surnamed village with a lineage group under different surnames: Ong, Toh, Liang, and Lin. The Anzhong Ong (安中王) branch, who lived in Jin’an village (金安村), built their temple, Houchi Hall (后池厅), to worship the Pu’an Ancient Buddha (普庵古佛) (Qing Shui Zu Shi), and built Jinshuiguan (金水馆) with the Lin clans to worship Lords Five (Wu Fu Wang Ye五府王爷).17 At the same time, the villager in Jin’an also paid worship to Master Puti (菩提祖师) of Longxuyan, which was built against the backdrop of Xiangyun Mountain. The religious sphere of Longxuyan is territorial, it was not controlled by a single lineage or village.18

If the ancestral temples Weng Shan Hong(翁山洪) and Yun Feng Toh(云峰卓) show two very different, or even opposite patterns of lineage relationship, then the Xiangyun Ong is more likely to be in the middle of the spectrum. This close lineage relationship and the interdependent temple system also shaped the shape and subsequent development of the Xiangyun Ong’s ancestral temples in Singapore.

In Singapore, there were several ancestral temples of Xiangyun Ong, established by the Huangtian and Anzhong (Jin’an) clan branches, namely Long Quan Yan at 11th Rural Road (十一乡道) (Lao Ba Village) in Yio Chu Kang, Longxuyan Jinshuiguan at 10th Mile (Liu Xun Village) in Yio Chu Kang, Jinshuiguan established in Jurong and then relocated to Choa Chu Kang Nei Dong Cheng village, and Houchi Hall at 8th Mile in Tampines (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Ancestral temples of Xiangyun Ong clan.

It is worth noting, however, that there are a number of temples that bear the name “Longxuyan” in Singapore but owned by different lineage groups. For example, Neo lineage from Xiang Yun Town established the Longxuyan temple in Jurong East and is now united into Jurong Combined Temple (Table 4). Additionally, Nanyang Neo Clan Association built Longxuyan as the ancestral temple (Singapore: Nanyang Neo Clan Association 1984).

When faced with relocation, the Wang Clan ancestral temples scattered in different village communities underwent limited reorganization, but eventually, they collaborated with neighboring village temples to establish different joint temples. One of these temples, Liu Xun Village Longxuyan Jinshuiguan and Nei Dong Cheng Jinshuiguan, was chosen to be combined, probably because of the close association between these two Wang Clan ancestral temples in Xiangyun from the very beginning of their construction. According to the documents preserved in the Longxuyan Jinshuiguan, Wu Fu Wang Ye of Jinshuiguan originated from the Jinshuiguan in Jinbing village (二十八都金柄社) of Nan’an (i.e., the present-day Jin’an village). In 1937, Lin Jiaxi (林嘉禧), a Daoist master who established the Daoist altar of Nanshan Puji (南山普济坛), arrived in Hougang (后港), Singapore, with incense Five lords (五王府) from Jinshui Kuan. Later in the 1940s, Ong Ketong (王可通) and Ong Kechuan (王可传), who lived in Jurong, and Ong Wengui (王文贵), who lived in Liu Xun Village, Yio Chu Kang, branched the incense from Lin Jiaxi to build Jinshuiguan in their settlement village. The two temples in Lak Xun and Jurong maintained a close relationship based on both lineage and religious ties, and set a stage for the later unification of the two ancestral temples.19

After the temple was built, the Jurong Jinshuiguan was relocated to Nei Dong Cheng village in Choa Chu Kang and was renamed Nei Dong Cheng Jinshuiguan. Jinshuiguan in Liu Xun then expanded into a double temple and gradually covered the different belief systems of Jin’an Village in the original village. After the expansion, the front hall remained as the Jinshuiguan and was dedicated to Wu Wang Fu Da Ren. In contrast, the back hall was added to the temple to enshrine several deities from the ancestral hometown, including Master Puti (Longxuyan), Pu An Gu Fo (普安古佛) (Houchi Hall), and Da De Chan Shi (大德禅师) (Longyun Tang龙云堂), and the name was changed from Jinshuiguan to “Longxuyan Jinshuiguan”. In 1983, when Longxuyan Jinshuiguan in Liu Xun was faced with the land acquisition by the government and Nei Dong Cheng Jinshuiguan was in a difficult situation, it was decided to donate all the funds to merge with Longxuyan Jinshuiguan.

After the furnace at the back of Longxuyan Jinshuiguan, two temples located in the same area of Liu Xun Village in Yio Chu Kang co-operated to purchase land and establish the joint temple “Liuxun Sanhemiao”.20 Located in the present-day Ang Mo Kio Industrial Park, the three temples each have their separate shrines, and the temple’s management is relatively independent. Apart from participating in the registration of Liuxun Sanhemiao, Longxuyan Jinshuiguan is also registered as a separate society, and the temple has its own space for religious activities and has always maintained the exclusivity of its consanguineous clan.

The other two Xiangyun Ong clan ancestral temples, Long Quan Yan and Houchi Hall, have chosen to form a United Temple with the neighboring village temple and are gradually being integrated into the new whole of the United Temple while maintaining the clan boundary of the ancestral temple.

Long Quan Yan was given incense at Long Quan Yan, Huangtian Village (Huangtian clan branch). It was built in 1920 at Lao Ba Village, 11th mile from Yio Chu Kang. In 1981, the government expropriated the land at Lao Ba Village, so Long Quan Yan, together with Hua Tang Fu and Ji Fu Gong (集福宫), both located in Lao Ba Village, established the United Temple “Chu Sheng Temple”.21 In 2011, 2016, and 2018, more than 150 members of the temple organized the “Jushengmiao Quanzhou/Anxi/Nan’an pilgrimage group” (“聚圣庙泉州/安溪/南安进香团”) to visit the ancestral villages and clans of the temples, including Huangtian Village, as a group. During the reconstruction of Longxuyan Jinshuiguan, the temple also made a collective donation of SGD 5000 to the temple, an ancestral temple of the Xiangyun Ong clan.22

Although Long Quan Yan is mainly used as a United Temple for temple services, its ancestral temple nature has not disappeared, and Long Quan Yan is still the ancestral temple of Huangtian Wang clan. With Long Quan Yan as the center, the Huangtian Wang Clan Organisation of Singapore participated in the genealogical renewal of the original township Xiangyun Huangtian Wang Clan Jiacheng (《象运黄田王氏家乘》). In 2018, Long Quan Yan, in its dual capacity as a temple under the Chu Sheng Temple and as the ancestral temple of Huangtian Wang Clan, hosted the genealogy ceremony for the completion of Xiangyun Huangtian Wang Clan Jiacheng and invited members of Seh Ong Charity (Kyban Congsee) and the Houchi Hall (An Zhong clan branch) to join in. The development of the Houchi Hall followed a similar path to that of Long Quan Yan, as in 1992, the Houchi Hall, located at 8th Mile, Tampines Road, also formed a “Tampines Chinese Temple” with neighboring temples (Singapore: Tampines Chinese Temple 2001).

2.4. Summary

The establishment of Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan and the combination of Wengshan Hong’s temples in Singapore was not achieved occasionally but the result of various factors: firstly, the integrated and cooperated relationship between different sub-branches of the hometown lineage. Secondly, the location of two main temples that contributed to the establishment of Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan is geographically close. As a consequence, the two were affected by the Government’s land acquisition program simultaneously. Thirdly, the overseas lineage group has influential leaders.

The temples of Yun Feng Toh, Teong Siew Kuan, and Hong Leng Yien Temple also reveal the lasting impact of homeland lineage in overseas communities and their temples, but in a different way. It may facilitate the unification of ancestral temples (in the case of Hong Leng Yien Temple) but could also result in the ‘non-unification of temples’ (Teong Siew Kuan). The ancestral temples of Xiangyun Ong Clan seem to have a more general pattern of development and transformation. In Ong’s case, the blood lineage ties play an important role in their choices of combination strategies; however, the distinction between different lineage branches may not be eliminated easily. The combination of temples would still require other external conditions.

Most of the ancestral temples in Singapore were united with temples of other social groups, and the reasons were diverse. The regional bonding of hometowns may have a lasting impact. For example, the six ancestral temples from Anxi (安溪)–Zhong Ting Miao, Xiang Fu Ting and Pu An Gong, were united into Peng Lai Si, a temple belonging to the Anxi community. However, with the settlement of immigrants, a new village alliance developed overseas, and it could drive the combination in many cases. The ancestral temples in Chu Sheng Temple, Liuxun Sanhemiao, and Jurong Combined Temple chose to unite with other temples in their local villages.

Under the United Temple, the ancestral temples also operate in a different pattern: temples such as Teong Siew Kuan and Longxuyan Jinshuiguan were able to maintain their independent architectural and worship space in the United Temple, while ancestral temples such as Long Quan Yan, Hua Tang Fu, and Houchi Hall maintained their temple bloodline in the common temple space of the United Temple, with the United Temple as a whole as a premise.

The ancestral temple is a syncretic field that contains multiple historical times and spaces. On the one hand, the ancestral temple is outstretched from local social history in southeast China. The lineage organization and worship system in the home villages have been re-localized in overseas ancestral temples. Overseas Chinese lineage is not just a simplified, weakened pattern of Chinese lineage as claimed by scholars such as Maurice Freedman. On the contrary, the lineage genealogy could still exist in the temple, even if it was dismantled or reorganized. On the other hand, ancestral temples also record the development of lineage in overseas society. Most Chinese ancestral temples were primarily located in rural areas of Singapore. They witnessed the transformation of a rural society which is an important supplement for Singapore’s urban-centric history narrative.

The above cases illustrate that the researcher cannot use a single dimension of historical and cultural elements to elaborate on the development of ancestral temples, let alone interpret the different paths and strategic choices in the process of moving towards the union of ancestral temples.

3. Geographical Temples

The differences in social customs and religious beliefs in native China have cultivated a strong sense of regional identity, whereas, in Southeast Asian settlements, the “Pang” (帮 league) formed by different dialect groups are a feature of the social structure of Singapore and Malaysia.23 As stated by Yong Ching Fatt (杨进发) and Lim Xiao Sheng (林孝胜), immigrants from the same dialect group may form geographical, consanguineous, or occupational organizations.24 The “geographical temples” discussed in this paper are the temples which are assembled by the geo-relationship of homeland and settlement, based on the people who have the background of similar dialects, or the same dialects, similar dialects but divided into different boundaries, or being in the same industry since sharing the same dialects. Compared with the consanguineous temples, the dialect group of the “geographical temples” has specific restrictions on genealogy, ancestors, and native land. The geographical temples break through the boundaries of blood relationships and neighborhoods. They are based on the belief in the local deities of their native land and have a wider range of believers. Compared with the deity-related temples, which were found in Singapore, the geographical temples have the inherent advantage of connecting the two spatial entities of the original place and the local community in Singapore, making it easier to re-integrate or re-strengthen Singapore’s regional immigration network.

According to Yen Ching-Hwang in A Social History of the Chinese in Singapore and Malaya, although many dialect groups have a general religious concept, that is, belief in Buddhism, upholding Confucianism or Taoism, or worshiping local deities, they disdain other groups’ customs since they generally have a mindset that their customs are more elegant and noble than others. Eventually, worship of different deities reinforces this prejudice (Yen 1991b). When the government expropriated the land of the temples, these geographical temples had to let go of their prejudices and build new alliances based on the belief network of the ancestral deities of the original geography or the new community network constructed by the local geography. This article figures out the different paths of different geographical temples to achieve a union through introducing the development of different geographical temples in the original places and local society and analyzing and evaluating the development status after different paths.

3.1. The Geographical Temples United by the Belief of Common Ancestral Deities

This paper selects the Anxi (安溪) ethnic group as the main object of discussion. Since the beginning of Chinese immigrants in Singapore in the 19th century, Anxi immigrants have settled in Jalan Cherah, Singapore, and built many temples, including Hoo Leong Keong (阜龙宫), Chee Chea Temple (七寨庙), Kong Siew Temple (广寿堂), Hong Lai Sze Temple, Leang San King Temple (龙山宫), Jiu Feng Yan (九峰岩), Tien Nam Shi Temple (镇南寺), Zhong Ting Miao (中亭庙), etc., most of which have the sub-joss (分香, the joss from the deities in a certain original temple) of Qing Shui Zu Shi(清水祖师) in Anxi, Fujian, China, making the geographical feature apparent.

Qing Shui Zu Shi also known as Penglai Zhushi (蓬莱祖师), Pu’an Zhushi (普庵祖师), etc., commonly called Zhushi Gong (祖师公), was originally a sage in the Song Dynasty. In the sixth year of Yuanfeng (元丰), he was invited to Penglai, Anxi to pray for rain, and the place rained heavily as soon as he arrived at Penglai. He became famous in Anxi, and the people raised funds to build a temple for him to stay. With the expansion of the Anxi people’s demand for praying, the vocational capability of Qing Shui Zu Shi has been enriched, too, and he has become the local patron saint of Anxi after his death. The influence of Qing Shui Zu Shi has gone beyond Anxi with the continuous development and has become a deity worshiped by all counties in Quanzhou—even people in Changtai (长泰) in Zhangzhou (漳州), Youxi (尤溪) in Nanping (南平), and other places have begun to believe in Qing Shui Zu Shi, and his influence has expanded to the entire southern Min area (Lin and Lyu 1999, pp. 1 and 7). Qingshuiyan (清水岩), the first temple in China, is located at the foot of Penglai Mountain in Anxi County, Quanzhou City, Fujian Province. With the continuous migration of believers to all parts of Southeast Asia, the worship culture of Qing Shui Zu Shi has flourished all over the world; there are currently about 300 branches of Qingshuiyan Temple all over the world, China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Singapore. The Anxi people carried the joss ash (香火, symbols/carriers of a temple or deity) of Qing Shui Zu Shi and immigrated southward to Singapore, making the Qing Shui Zu Shi belief rooted and grow in Singapore, and became a symbol of bonding Chinese immigrants and their ancestral home (Zeng 2006a, p. 14).

In the early days of Singapore’s opening as a port, the Anxi people immigrated to the south to make a living to avoid war. Apart from operating businesses of hardware, tea, grocery, and other industries in the urban area, many Anxi immigrants lived in the rural areas of Singapore to engage in agricultural reclamation, forming a huge Anxi immigrant community. The community was represented by its general organization, Ann Kway (Anxi) Association, which was established in 1922. In 1953, the overseas Chinese leaders of the Ann Kway Association mobilized immigrants to raise huge sums of money to build a temple dedicated to Qing Shui Zu Shi in the rural area of Jalan Cherah in Singapore, making Hong Lai Sze Temple a geographical temple worshipped by Anxi immigrants, and a community center outside of Ann Kway Association after years of development (Zeng 2006a, p. 14).

Along with the immigration to the south, the Anxi immigrants moved the joss ash香火 of the Qing Shui Zu Shi of Qingshuiyan in China to Hong Lai Sze Temple. In 1980, they brought some cultural relics and statues of the Qing Shui Zu Shi in China to Singapore, such as the photos of Qingshuiyan in Anxi and the statue of Qing Shui Zu Shi, etc. Hong Lai Sze Temple was modeled on the Bunrei (分灵, same as 分香, the act of asking for the joss ash from the deity in a certain temple and taking it back to worship) ceremony held in China on the birthday of Qing Shui Zu Shi (the sixth day of the first lunar month) and took it as Qing Shui Zu Shi to participate in the Deity Pageant Ceremony (游神) in the Singapore branch temple (Ang n.d.).

Due to the development plan of the Singapore government in 1986, Hong Lai Sze Temple, which was the liaison center of the Anxi community, became the shelter of all Anxi temples (Zeng 2006a, p. 15). The clan temples of six clan communities in different villages in Penglai Town (蓬莱镇) of Anxi merged with it to form the new Hong Lai Sze Temple, which was completed in 新加坡后港第一大道. These six clan temples are, Xiang Fu Ting (祥福亭) of the Kua (柯), Shui Kou Gong (水口宫) of the Leow (廖), Ming Shan Gong (名山宫) of the Lieu (刘), Pu An Gong (普庵宫) of the Lee (李), Ci Ji Tang (慈济堂) of the Chang (张), and Zhong Ting Miao (中亭庙) of the Lim(林).

According to Zeng Ling’s research, the joss ash of these clan temples was successively brought to Singapore by immigrants from Anxi in various ways and were enshrined and worshipped by the nearby Anxi immigrants who raised money to build temples. For instance, the mother of Mr. Kua, the former vice president of the Singapore Kua Clan Association, brought the “duplicate” of Lord Zhou (周府大人) from Xiamen to Singapore by the sea in the late 1940s and Lord Zhou was enshrined in Xiang Fu Ting; the Zhang San Xiang Gong (章三相公) enshrined in Pu An Gong, was the “golden statue” carried by the uncle of the current chairman of Hong Lai Sze Temple, Mr. Lee, from his hometown to Guangzhou, and taken by another uncle of his from Guangzhou to Singapore by plane; as for Zhong Ting Miao, the enshrined Lord Xing (邢府大人) was initially a pack of joss ash brought by Mr. Lim’s grandfather, who was nearly 80 years old, from the temple in his hometown and to Singapore in the early years of the Republic of China; Lords Zhu Xing and Li (朱,邢,李大人) in Ming Shan Gong, was the “duplicate” brought by the clansman by carrying in a wooden box on the back during the immigration (Zeng 2006a, p. 15). Since Shui Kou Gong and Pu An Gong were later closed, the Hong Lai Sze United Temple, which is a combination of five temples today, was formed (Table 5).

Table 5.

The Main Deities Worshipped in Hong Lai Sze United Temple.

Most of the above-mentioned “ancestral deities” originating from various villages in Anxi were rarely known, and even fewer were worshipped after the southward immigration. After the merger with Hong Lai Sze Temple, their influence gradually expanded, but the Qing Shui Zu Shi is still the main deity in the Hong Lai Sze Temple United Temple. The main hall of the Hong Lai Sze United Temple has seven altars, which are dedicated to the deities of the five temples that make up the United Temple, and they, from right to left, are Xiang Fu Ting, Ming Shan Gong, Hong Lai Sze Temple (hold three shrines), Ci Ji Tang, and Zhong Ting Miao. The statue of Qing Shui Zu Shi placed in the main hall of Hong Lai Sze Temple has only a history of about 45 years old, while the statues on the left and right sides have a history of about 200 years, which is different from the arrangement of other temples where the oldest statue is placed in the center of the main hall. It reflects the leading role of the geographical temple and the ancestral deities in the Hong Lai Sze United Temple.

Although Qing Shui Zu Shi is enshrined as the top among all main deities in the Hong Lai Sze United Temple, the belief and worship culture of the ancestral deities of each temple are still valued. Since the five branch temples from the same village have the same date and time for prayers, the management distributes the prayer dates fairly by asking the deities with “Jiaobei” (筊杯, used in pairs and thrown to seek divine guidance in the form of a yes or no question) and representatives of each temple take turns throwing the Jiaobei to determine the date of prayer (Ang n.d.). These different ancestral deities in various villages in Anxi County reunited in Singapore overseas under the same roof of the Hong Lai Sze United Temple, forming the so-called “new confederation” of home deities, and uniting the villagers of various villages in Anxi under the common worship.

To sum up, the belief of Qing Shui Zu Shi became the carrier of the common consciousness of the Anxi immigrant ethnic group in Singapore. The social network of Anxi and the belief in the ancestral deities caused by the geography broke the estrangement between the six clan temples from different clans, worked together to solve the problem of land acquisition, and promoted the “re-communalization” of Anxi people from various villages.25

In addition to the local deity Qing Shui Zu Shi, other deity beliefs popular in Chinese local society may also become carriers for integrating geographical communities and continue to develop to meet local needs.

The Chee Chea Temple (七寨庙) at Ama Keng Road off Lim Chu Kang Road (阿妈宫路林厝港) and Leng Hup San Gong龙合山宫at Mandai Road (万礼路) are both Anxi geographical temples, in which the joss ash of the deity, Guan Di Sheng Jun (关帝圣君), was brought by different Anxi immigrants. In the 1930s, Mr. Su An (苏安) brought the joss ash of Guan Di Sheng Jun from the Tong Zhun Guan Di Miao (通准关帝庙) in Anxi County, Quanzhou, Fujian to come to his home in the Mandai Village’s Hu Tou Shan to worship. Later, Mr. Su An and the villagers built a simple temple and named it Hu Tou Shan Gong (虎头山宫), which was not changed to Leng Hup San (龙合山) until the 1960s. In 1937. The Chee Chea Temple brought the joss ash of Guan Di Sheng Jun from Anxi County, Quanzhou, Fujian to worship on an altar at Ama Keng Road in Lim Chu Kang. Because of land acquisition, the Chee Chea Temple moved into the unused Qihua School (启化总校) in Tong He Village (通和村). In 1988, the Chee Chea Temple moved to Hu Tou Shan and merged with Leng Hup San (龙合山), becoming Leng Hup San Chee Chea Temple (龙合山七寨庙).

In 1991, because the land of Hu Tou Shan was also requisitioned, the Long Shan Gong Chee Chea Temple purchased the land at Teck Whye Land in Choa Chu Kang (蔡厝港) to build a new temple. In 1992, the temple even temporarily moved into a container at its current address until the new temple was completed in 1996 (Long Shan Gong Chee Chea Temple New Temple Completion and Opening Ceremony Special Issue, p.7). The two geographical temples are united because of the common native deity they serve, Shanxi Fuzi (山西夫子) (namely Guandi (关圣帝君) and Xie Tian Da Di (协天大帝)). However, unlike the Hong Lai Sze Temple’s integration of Anxi ancestral deities, although the Longhe Mountain Qizhai Temple has Anxi geographical factors, no huge network of Anxi believers is formed and is more dependent on the development of local believers in Singapore. Therefore, it had to consider promoting the “localization” of deities to gain more local believers. In 1988, the Long Shan Gong Chee Chea Temple started enshrining the deities of Confucius and Yue Lao (Soo 2008). Students would be given school bags on the Birthday of Confucius for the blessing of getting good academic results; and the belief in Yue Lao is praying for “red thread” (红线, the legendary red thread connecting marriage) to the youths, to soon find a partner and get married, producing the next generations for Singapore. The addition of these study-related and marriage-related deities has undoubtedly increased the number of believers and prayers in the Long Shan Gong Chee Chea Temple.

Overseas immigrants are known as tending to achieve self-integration through local deities with geographical colors. Whether or not a geographical temple can integrate a huge network of believers through ancestral deities affects the degree of its “localization”. The influence of the ancestral deities on the development path of the geographical temples is visible.

3.2. The Geographical Temples United by Proximity Factors

Affected by the temporary changes in land acquisition by the Singapore government, many geographical temples had to quickly select new sites and unite with other temples to build a new temple, while there were not many opportunities to consider and decide. Therefore, most of them chose to “speed-match” with the neighboring temples.26 There were no factors of historical origins or ancestral deities but just a quick response to the compulsory acquisition policy.

3.2.1. The Combination of Geographical Temples and Geographical Temples

Although the belief in ancestral deities from the original hometown is an important factor in condensing the geographical dialect group, the “geography” may not become an opportunity to promote the combination of temples. In some cases, temples will consider the actual situation of their local development and break the geographical boundaries, uniting with a nearby temple in the same rural community.

Take the Jurong Road 10th milestone as an example, there used to be six geographical temples of the Xinghua (兴化) and Nan’an (南安) communities, which were Qiong Yao Jiao Di (琼瑶教邸), Ling Jin Tang (灵晋堂), Guan Shan Dian (观山殿), Shui Gou Guan (水沟馆), Xi Shan Gong, and Long Xu Yan (龙须岩).

Qiong Yao Jiao Di has derived from the Kiew Lee Tong (九鲤洞) sect. The Kiew Lee Tong sect was founded by the Shiting (石庭) Ng (黄) clan, known as “the foremost clan of Henghua (兴化) overseas Chinese immigrants”.27 There are three types of transnational cultural networks for the Shiting people in China and overseas: one is a family network marked by ancestral halls (祠堂) and ancestral houses (祖厝); the second is a network of fellow villagers marked by Lishe (里舍, places where the deity of the land is worshipped) and village temples; the third is a sect network marked by Tanban (坛班) and Sanyi teaching (三一教). “Qiong Yao Jiao” is one of its three major sects, the full name is “Qiong Yao Da Fa Yuan” (琼瑶大法院), referred to as “Xian Jiao (仙教)”, of which the most influential is the Kiew Lee Tong system known as Qiong Yao Jiao.28

During the Japanese occupation of Singapore, Kiew Lee Tong believers began to raise funds to build temples, forming a relatively independent missionary system, and officially relocated to Tiwari Street (弟哇哩律) in 1941. Since then, “Feng Jia Pu Du” (逢甲普度) has been held every 10 years by Singapore Kiew Lee Tong, and the ceremony of “Su Tan Chi Jie” (肃坛持戒) has been held regularly, leaving a wide range of influence in the local Chinese community.29 However, on this basis, the cross-national cultural network of overseas Shiting (石庭) people has been expanding, and it was difficult to maintain the family settlement in the hometown. Therefore, more attention was paid to the network beyond the family. Since the 1950s, the followers of Kiew Lee Tong in Singapore began to split up. In 1952, Huang Ya Bing (黄亚彬), a member of the Shiting Huang clan, joined forces with taxi drivers and barbers from Xinghua, Putian, to initiate the establishment of Qiong Yao Jiao Di, which was built at Jurong Road 10th milestone in the 1980s, forming new temples and branches under the Kiew Lee Tong sect (Zheng and Zheng 2012, pp. 89–128).

The creation process of the other five Nan’an temples in the Jurong Combined Temple is completely different from that of Qiong Yao Jiao Di, which in most cases, the villagers brought the deity’s “duplicate” to Singapore. For instance, the Ling Jin Tang originated in Pengchuang Village, Xiangyun Town, Nan’an County, Quanzhou, Fujian Province, China. In 1915, Huang Zhang Dun (黄章盾) brought Lord Sun (孙府大人), Lord Yu (余府大人), and Lord Chi (池府大人) from his ancestral home to Singapore. Later, the local philanthropist provided funds for Ling Jin Tang to build the temple, and Zuo Chao Zhi (卓潮枝) donated his private land at Jurong Road to Ling Jin Tang as the construction site. Guan Shan Dian originated from Guanyin Mountain in Guangdecun (光德村), Anxi County, Quanzhou, Fujian, China. In the late Qing Dynasty, an Anxi native brought the joss ash of Guanshan Tang (观山堂), the ancestral temple, to Singapore and enshrined it in his home. In 1943, Wang (the specific name is not recorded) donated his real estate as the construction land for the Guan Shan Dian, hoping to worship the ancestral deities on the 13th and 14th of the lunar month every year. Furthermore, the joss ash of Shui Gou Guan, Xi Shan Gong (西山宫), and Long Xu Yan come from Yingduzhen (英都镇), Shishanzhen (诗山镇), and Xiangyunzhen (翔云镇) in Nan’an County, respectively.30

Evidence shows that the vicinity of Jurong Road is the gathering place of immigrants from Putian in Fujian and Nan’an in Quanzhou. As the joss ash came to the south, a very dense network of geographical temples was built near the place with active support and sponsorship by the local early immigrants, laying the foundation for the later combination nearby. With the issuance of the expropriation order in the 1980s, Qiong Yao Jiao Di and five surrounding temples raised funds to purchase land and built the Jurong Combined Temple at No. 42–741 Jurong West Street, Singapore.

The newly built Jurong General Palace consists of two buildings with similar scales, adopting the pattern of six temples divided into two halls (六庙分两殿), in which the Qiong Yao Jiao Di occupies one, and the other five temples share the other one. The shrines of the five Nan’an temples occupy basically the same space; from left to right, they are Guan Shan Dian, Shui Gou Guan, Ling Jin Tang, Xi Shan Gong, and Long Xu Yan. Moreover, the two buildings are connected by a public car park. The layout of the Jurong Combined Temple may be due to two reasons: first, only the Qiong Yao Jiao Di is a geographical temple of the people of Putian, Fujian, and the other five are from Quanzhou, Fujian; second, Qiong Yao Jiao Di, as one of the branches of the Kiew Lee Tong Sect, the Shiting Ng clan has a long history and has its own belief network and groups of believers, which is rather strong. The other five Nan’an Temples are mostly brought to Singapore by a single immigrant, which is less influential.

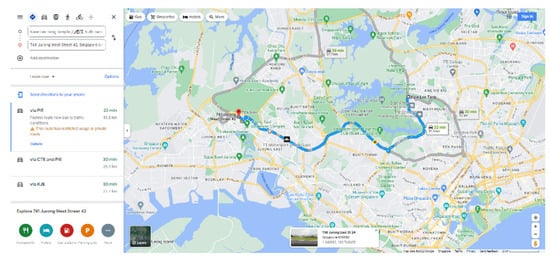

In addition to the geographical proximity factor that made Qiong Yao Jiao Di choose to combine with the five Quanzhou geographical temples, the independence of its own belief model is the original factor. As mentioned above, the Qiong Yao Jiao Di (琼瑶教邸) is derived from the Kiew Lee Tong (九鲤洞) sect, founded by the Shiting Ng clan in 1952. Additionally, the Singapore Kiew Lee Tong Temple stopped moving in 1979 and is located at Jalan Tambur after several relocations.31 According to the temple building history of Qiong Yao Jiao Di, it happened to be moved 10 miles away from its original site at Jurong Road 10th milestone in 1980, which coincides with the timing. The distance between the two locations at the relocation node is searched and revealed that they are quite close, with less than 30 min of driving time (Figure 1 and Figure 2). This tells that, as the only two Qiong Yao Xian Jiao (琼瑶仙教) temples in Singapore with the same geographical location, the Qiong Yao Jiao Di and the Kiew Lee Tong Temple should have combined with each other, but the Qiong Yao Jiao Di chose to move to the Jurong Combined Temple, which is one mile away from the original site. After interviewing members of the Kiew Lee Tong sect, Zheng Li believes that this phenomenon was due to the formation of a self-contained sect network within the Kiew Lee Tong sect. In the 1960s, the Qiong Yao Jiao Di split into Qiong Yao Xian Jiao (琼瑶仙教), Qiong San Tang (琼三堂), and Qiong Yao Fen Zhen (琼瑶分镇) in Ayer Itam, Johor, Malaysia. Additionally, the ritual group of the Tanban (坛班) started having disputes, the Qiong Yao Jiao Di derived from the same belief system, forming new temples and branches under the Kiew Lee Tong sect.32

Figure 1.

Driving distance between Kiew Lee Tong (九鲤洞) and Qiong Yao Jiao Di (琼瑶教邸) in 1979.

Figure 2.

Satellite distance between Kiew Lee Tong (九鲤洞) and Qiong Yao Jiao Di (琼瑶教邸) in 1979.

It can be seen that Qiong Yao Jiao Di and Kiew Lee Tong, which are in the same geographical location or even in the vicinity, refused to combine because of differences in the sectarian network system, but instead, combined with the five Quanzhou geographical temples of which their deity beliefs are completely different. When these six geographical temples with different regions, different belief systems, and different scales of believer networks are combined, their worship content, ritual traditions, and management models rely on the original hometown yet integrate with the local, reflecting the differences in geography and the collaborative color of cross-regionalization.

The construction of Qiong Yao Jiao Di is a sectarian network marked by ritual groups such as the Tanban (坛班) and the Sanyijiao (三一教). The so-called Tanban is a kind of institutionalized Jitong (乩童, spirit medium) organization, in which the basic members are divided into Shentong (神童) and Futong (扶童) and Fuji (扶乩) and Chijie (持戒) are the main ritual activities (Zheng and Zheng 2012, pp. 89–128). In the overseas Putian and Xinghua communities, the Tanban and the Sanyijiao are the most active ritual groups; thus, forming a sectarian network at home and abroad. The believers of Qiong Yao Jiao Di also inherit the sect rituals, sending their children to the temple for training, learning carols (颂歌) and Nuo dance (傩舞), reciting mantras, writing amulets (护身符), and ways to communicate with the deity and spirit, in the hope that their children will become Shentong (神童) and gain participation qualifications for the ceremony of “Su Tan Chi Jie”, thereby the family will be blessed by the deities.

Although there is less contact with the Singapore Kiew Lee Tong, Qiong Yao Jiao Di has always maintained close contact with their fellow villagers. This international connection is rooted in and fed back to the construction of a transnational cultural network by the long-standing local cultural tradition. Meantime, the prayers and sacrifices of the Qiong Yao Jiao Di also promote inheritance and renewal in accordance with the actual situation. Xinghua has had a tradition of praying for blessings through opera performances since ancient times. However, due to the small number of Xinghua people in Singapore and the lack of opera troupes, the cost of hiring a Xinghua opera troupe is extremely high. With the original intention of retaining the traditional form as much as possible, Qiong Yao Jiao Di changed to the puppet show that is more common in Singapore and improved the classical drama script of Xinghua into a puppet drama to celebrate the birthday of Nan Xun Tian Zun Shi Yuan Lu Xian Zhang (南巡天尊士元卢仙长), on the fourth to the sixth day of the fifth lunar month. The puppet performances will be held in the Jin Ling Tang as well in the celebration on the 12th and 13th days of the eighth lunar month, when offering sacrifices to the main deity, Lord Sun, showing that the Xinghua tradition breaks the geographical restrictions and assimilates the Nan’an, Quanzhou’s sacrificial ceremonies.

On the other hand, the five Nan’an geographical temples shared the same sacrificial space to worship the deities of each temple, and even organized a set of the same sacrificial procedures. The management committee would mark the blessing procedure near the incense burner and reminded the believers of the order of prayer and the number of joss sticks required (Table 6). Moreover, the Shui Gou Guanpostponed the birthday celebration of their major deity, Lord Jin (金府大人) on the ninth day of the eighth lunar month to the sacrificial ceremony of Lord Sun, the major deity of Ling Jin Tang on the 12th day of the eighth lunar month and worshipped together with Ling Jin Tang. The five Nan’an temples have formed a trans-geographic fusion while maintaining their respective main deities (Tan n.d.) (Table 7).

Table 6.

The order of prayers in the five Nan’an(南安) temples.

Table 7.

Deities enshrined in the Jurong Combined Temple(裕廊总宫).

3.2.2. The Combination of Geographical Temples and Temples of Other Properties

There were not many considerations for the “speed-match” combination of some geographical temples under the pressure of the government’s mandate, and most of them can only be combined with other nearby temples in a hurry. Compared with the United Temples having the same ancestral deities and the same region, the combination of this kind of complexity undoubtedly faces a more difficult belief gap.

As mentioned above, the Hong Lai Sze United Temple is based on the common deities, making the different consanguineous temples combined and the reinforced “new confederation”. Similarly, the geographical temple, Peng Lai Dian (蓬莱殿) in the Sembawang United Temple (三巴旺联合宫) is also dedicated to Qing Shui Zu Shi and is united with the consanguineous temple and the Shenyuan Temple, but its development is widely divergent from the former.

Unlike Hong Lai Sze Temple which was directly distributed from Qingshuiyan by immigrants from Anxi, the joss ash of Peng Lai Dian in Sembawang United Temple came from the secondary transmission. In 1978, Mr. Oh (胡) who was weak and sick, went to Genting Highlands to ask Qing Shui Zu Shi in the temple to cure his illness. After returning, he behaved strangely and his temperament changed greatly. The psychic believed that Mr. Oh (胡) was possessed by Qing Shui Zu Shi and his family members and neighbors have been worshipping Qing Shui Zu Shi since then. Afterwards, Mr. Hu (胡) brought the temple joss ash in Genting Highlands back to his home in Choa Chu Kang, set up a special shrine to worship Qing Shui Zu Shi, and named it after Peng Lai Dian. Then, urbanization in 1988 forced the temple to undergo several relocations, from the rural area to HDB and then to a construction site somewhere (Chen n.d.). In the end, Dato Wang Qiang Ni (拿督王强尼) (Mr. Hu’s nephew), the current head of the temple, won the bid for the location of the Sembawang United Temple, and combined with the Sembawang Tian Ho Keng and the Sembawang Deity of Wealth Temple. They were not familiar with each other since the bidding was only the reason they met.

The Sembawang Tian Ho Keng was established by the Lin family, based on the introduction of Mr. Lin Caidong, the head of the temple.33 In 1947, the Lin clan who lived in Yishun and Sembawang founded a clan association, called “Sai Ho Koo Kay (西河旧家)” in Cia Cui Kang (汫水港) (Seletar 10th milestone, today’s Up Thomson Road). The Lin family placed a shrine called the Sai Ho Koo Kay Tian Ho Keng (西河旧家天后宫), in the building. In 1962, Sai Ho Koo Kay Tian Ho Keng moved to Chong Pang, and to Yishun Industrial Park A later in 1988, and finally bid for the current site. The Sembawang Deity of Wealth Temple obtained “joss ash” from a temple in China and brought it to Singapore in 1998. The location of the original temple is unknown, only a simple shrine is known to enshrine the statue of the Deity of Wealth. However, since then, many neighboring believers have come to worship in order to seek the blessing of the Deity of Wealth, which has rapidly expanded its popularity. Soon after, a simple temple was built with donations from believers, and SGD 500,000 was spent to custom make the world’s tallest golden statue of the Deity of Wealth in Fujian, China. This 8.5-m-high, four-metric-ton statue of the Deity of Wealth, affixed with 120,000 pieces of gold leaf, is open 24 h for believers to offer incense. Sembawang Deity of Wealth Temple is one of the few temples that is open 24 h for believers to offer incense, the others are Chong Ghee Temple (万兴山崇义庙), Loyang (洛阳), Jurong Hong San See (裕廊凤山寺), and Po Chiak Keng (保赤宫) (Beokeng 2022).

It can be seen from the above that the composition of the Sembawang United Temple is complex, and each temple has no similarity in religious beliefs or social functions. Although the three are under the same temple, they are independent, and even in architectural styles. Under the blow of the Sembawang Deity of Wealth Temple, which worships material wealth, and the Sembawang Tian Ho Keng, which serves the children-related matters, the Peng Lai Dian is gradually in decline. Most of the believers who come to worship are asking for lottery poetry (求签, Kau Chim, fortune-telling practice) for guidance, ask for holy water to cure diseases, and bathe the Buddha on Vesak Day by convention (Chen n.d.). It does not have a clan community like Sembawang Tian Ho Keng and the cult of ancestral deities, nor does it bring new deities to expand its influence according to the needs of local Singaporeans like the Sembawang Deity of Wealth Temple. Since the temple failed to find its advantages and positioning, it has gradually gone into decline.

3.3. Summary

Geographical temples are often brought by pioneers from China to share the joss ash, which is different from the ties and attachments of consanguineous temples and deity-related temples in terms of clans, deities, etc., to attract residents of immigrant areas to worship together. The geographical temples that rely on regional community organizations to build a huge network of believers like the Hong Lai Sze United Temple are the minority, and most of the geographical temples are based on the geographical temples from China or the deities, trying to attract local villagers or residents of different races to complete settlement in the foreign land. Through the process of local development of temples, the social network of “geography” and “dialect groups” can still exert a huge influence. However, in the process of localization, temples may establish new social links in the communities in which they are located, providing multiple strategic options for local temples in the face of survival challenges. The development and union of the geographical temples are disintegrated or crumbled and involve strong contingency and variability, but also show a better reflection of the tenacious response of Chinese religious beliefs to urban development and policy changes.

4. Deity-Related Temple

A deity-related temple (神缘庙) is centered on the belief in one or more deity (deities) and can gather followers across differences in ancestral home, geography, and race, with the main task of worshipping the deity (deities). In the dual context of a multi-racial immigrant society and a multi-ethnic Chinese community, the process and influence of the interpenetration of Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, and folk beliefs in Singapore are fully reflected in the composite nature of Chinese religious beliefs and the miscellaneous nature of the deities worshipped in the temples in Singapore. In the following part, we will focus on several temples under the Jade Emperor (玉皇大帝), Huang Lao Xian Shi (黄老仙师), and Tua Pek Kong(大伯公). By tracing the trajectory of their establishment and development, we will examine the strategic choices, dominant differences, and systematic reconfigurations of the temples in the path toward a United Temple.

4.1. Tee Kong Toa (天公坛) and Yu Huang Tian (玉皇殿): The Difference between the Dominant and the Dominated under the Belief in the Jade Emperor

The Jade Emperor is commonly known as Tee Kong, the Deity of Heaven, and the full name is the “Haotian Jin Que Zhi Zun Yu Huang Da Di” (昊天金阙至尊玉皇上帝). The belief in the Jade Emperor can be traced back to the belief in the deity of heaven in the primitive beliefs of ancient times (Liu 2003, p. 3). Later, due to the flourishing of Taoism and the advocacy of the rulers, the Jade Emperor, the supreme deity who governs the deities of heaven, earth, and man, came into being. On the 25th day of the lunar month, the Jade Emperor himself, inspects the world, investigating the good and evil of all beings, rewarding good and punishing the evil. The ninth day of the first month is the birthday of the Jade Emperor, commonly known as the “Yu Huang Hui”(玉皇会), heaven and earth will hold a celebration event.34 The “Tong An Literature and history Material” (同安文史资料) recorded: this day “the folk prepared three animals (beef, lamb, pork), Pastry, fruits in 12am of the ninth day, open the door to honour the sky, burning special ‘heavenly gold’ (天公金), the firecrackers sounded for all night long, the event was very grand (Xiamen Literature and History Information Committee 2009)”. The most intuitive form of expression of folk beliefs is they worshipped to the temple, palace, altar, niche, etc. The Jade Emperor faith in Singapore is no exception, and the Hokkien dialect calls the Jade Emperor Deity “Tee Kong”, so the Jade Emperor faith temples are often named “Tee Kong Toa” or “Yu Huang Tian”. They either maintain independent operations or become United Temples (Table 8).

Table 8.

The Jade Emperor faith temples.

Locally in Singapore, the most famous Jade Emperor Temple is the Or Kio Tow Geok Hong Tian, built solely by the leader of the Hokkien Gang, Cheang Hong Lim (章芳琳). This is a typical temple where the three religions merge with folk beliefs. The temple is dedicated to the Buddhist Guanyin (观音菩萨), the Bodhisattva of Earth (地藏菩萨), the Buddha of Sakyamuni (释伽佛), Amitabha (阿弥陀佛), and Maitreya (弥勒佛); the Confucian Confucius (孔子) and ancestral tablets; the Taoist Jade Emperor, the Lord of the South Dipper (南斗七星), Lord of the North Dipper (北斗七星), the 24 Celestial Generals (二十四天将) and the San Yuan Da Di (三元大帝); and the folk Tua Pek Kong, Kitchen Deity (灶君), Mazu (妈祖), the Sun Deity (太阳神), the Moon Deitydess (太阴神), and the Madam Zhu Sheng (注生娘娘) (Yuan 2017, p. 85). Another temple dedicated to the Jade Emperor as the main deity was Yu Huang Tian which was established in the early years in Zheng Hua Village, and after years of development, it also has an extraordinary faith base and financial capacity, and the Jade Emperor’s statue in its temple is probably the largest in Singapore. Some of the more famous Tian Kong Altars in Singapore are Kheam Hock Road Tian Gong Tan, Tampines Tian Gong Tan, Tian Gong Tan (Jurong West United Temple), Hai Lam Sua Tee Kong Toa and Tien Kong Thun Temple. The first three altars were chosen to join the United Temple under the pressure of land acquisition, with Tian Gong Tan (Jurong West United Temple) being the most representative.

The current location of the Tian Gong Tan on Jurong West Street is a wooden temple built by villagers in 1917 inside the Clementi Park (Sunset Grove), dedicated to the Jade Emperor and the Thousand-Handed Guanyin. In 1943, it was first united with the Zhao Ling Gong Temple (昭灵宫), a geographic temple, and the deities of Zhao Ling Gong were invited to sit on the Tian Gong Tan altar for the villagers to worship, with the aim of providing a more convenient and comfortable place of worship for Zhao Ling Gong.35 After the union, the main beliefs of the temple are the Jade Emperor, the Thousand-Handed Guanyin (千手观音), and the Jiutian Xuannu (九天玄女), and the secondary deities are the Five Generals (五将军) and the Tai Sui Ye (太岁爷). In terms of temple furnishings, the temple is relatively simple in terms of architecture and decoration, with a simple rectangular layout and only one auditorium for the deities, the Jade Emperor is enshrined at the high point of the main auditorium, while the main deities of the Zhao Ling Gong temple, the Thousand-Handed Guanyin, and the Jiutian Xuannu, are placed on the lower altar in front of the Jade Emperor. As the incarnation of the supreme deity and a symbol of Taoism’s “reverence for heaven”, this placement represents that people start worshipping “heaven” before worshipping other deities. In terms of temple activities, the two temples have also unified, holding three grand festivals together each year: the Dagong’s Birthday on the 9th day of the first month of the lunar calendar, the Jiu Tian Xuan Nui’s Birthday on the 15th day of the 4th month, and the Zhong Yuan Festival (Yu Lan Festival) on the 1st day of the 7th month.