Abstract

This article reviews the first twelve months of the civil disobedience movement in Myanmar following the 1 February 2021 coup d’état and its many dynamics and manifestations. Myanmar’s ‘Spring Revolution’ generated a shared sense of national unity—overcoming gender, ethnic, religious and class boundaries, but raising questions about the long-term sustainability of nonviolent civil resistance in a state where the military has for decades wielded political and economic power. Since the coup, Myanmar has been in turmoil, paralysed by instability which escalated after the military’s deadly crackdown on pro-democracy activists. The article charts the growth of the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), its multiple methods of strategic resistance and non-cooperation, and the radicalisation of the resistance agenda. It analyses the formation of the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), the creation of the interim National Unity Government (NUG), the founding of the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC) and the inauguration of the People’s Defence Force (PDF). It examines the implications for Myanmar when the crisis reached a more complex phase after the military’s open use of force and terror on the broader civilian population prompted the NUG to declare war on the junta, and to urge ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) and newly formed anti-junta civilian militias (PDF) to attack the State Administration Council (SAC) as a terrorist organisation. The NUG now opposes the military junta by strategic and peaceful non-cooperation, armed resistance, and international diplomacy. This paper considers whether the predominantly nonviolent civil resistance movement’s struggle for federal democracy and inclusive governance is laying the foundations for eventual transition to a fully democratic future or whether the cycles of violence will continue as the military continues to control power by using intimidation and fear. It notes that the coup has destroyed the economy and expanded Myanmar’s human rights and humanitarian crises but has also provided the opportunity for Myanmar’s people to explore diverse visions of a free, federal, democratic and accountable Myanmar. It finally examines the possibilities for future peaceful nation building, reconciliation, and the healing of the trauma of civil war.

1. The Scholarly Literature: Nonviolent Civil Resistance

For Gandhi and those who followed him, the only way to secure a culture of peace, tolerance, understanding, and nonviolence was through the absolute renunciation of violence as a means of social change or conflict transformation. Nonviolence became more than an ethical or religious principle; it became a self-conscious method of social action with its own logic and strategy (Kosek 2005). In 1993, political scientist Gene Sharp sought to support the resistance movement in Burma by writing an essay on the generic problem of how to destroy a dictatorship and prevent the rise of a new one. From Dictatorship to Democracy (1994) originated in his work with the Burmese opposition and ethnic groups in the early 1990s and was intended as a blueprint for the liberation of the country from military rule.1 Sharp’s emphasis on strategic nonviolent struggle arose out of his realisation that every dictatorship leaves a legacy of death and destruction in its wake, and his belief that human beings should not be dominated or destroyed by such regimes. He points out that the literature on military coups largely ignores the role of civil society, nonviolent mobilisation, and civil resistance. Drawing on the ideas of Thoreau and Gandhi, he argues that peaceful campaigns against established oppressive forces are more likely to succeed than those that involve violence (Sharp 1990; [1994] 2012; Sharp and Jenkins 2003). Sharp listed nearly two hundred methods of nonviolent resistance, which he further divides into methods of social non-cooperation, persuasion, and intervention. The generic character of Sharp’s text resulted in the booklet making its way to numerous other countries, and Sharp emerged as one of the world’s most influential promoters of nonviolent resistance to repressive regimes. His theories have been widely adopted and adapted and incorporated into popular training manuals for nonviolent activism. From Dictatorship to Democracy has been circulated worldwide and cited repeatedly as influencing movements such as the Arab Spring of 2010–2012. Michael Beer et al. (2021) has recently revised, expanded, and recategorised Sharp’s list of civil resistance methods.

Political theorists have followed Sharp in arguing on pragmatic rather than ethical grounds that strategic nonviolence is more likely to achieve regime change, lead to peace settlements and foster democracy than violence. During the last two decades, a growing scholarly literature has developed the theory that nonviolent movements are more effective and less detrimental to the long-term peaceful transformation of a country plagued by civil war. Many political scientists now argue for the power of strategic nonviolent civil resistance, a method which Chenoweth (2021) describes as a method of conflict through which unarmed civilians use a variety of coordinated methods (strikes, protests, demonstrations, boycotts, barricades, and many other tactics) to prosecute a conflict without directly harming or threatening to harm an opponent. Stephen Zunes (2017) writes that, ‘Nations are not helpless if the military decides to stage a coup. On dozens of occasions in recent decades, even in the face of intimidated political leaders and international indifference, civil society has risen up to challenge putschists through large-scale nonviolent direct action and noncooperation’. Recent publications in this tradition of cross-over scholarly activism include Celestino and Gleditsch (2013), Bayer et al. (2016), Chenoweth and Stephan (2008, 2011), Chenoweth (2021), Dudouet (2011, 2013, 2017), Pinckney (2016, 2018, 2021), Abbs (2021) and Wanis-St. John and Rosen’s (2017) USIP report.

Gene Sharp and other seminal thinkers have been instrumental in changing attitudes about violence, in clarifying the power and value of nonviolence, and in helping us to understand how humans can build a global culture of peace. Peace is the condition for human flourishing and what is good for human beings as a species, and whole disciplines are now dedicated to peace studies, to dialogue and reconciliation. This paper seeks to contribute to the emerging literature on civil resistance movements, particularly to coup d’états, by reviewing current scholarly arguments for successfully counteracting the seizure and overthrow of a government and its powers in relation to events in Myanmar, where the military takeover of 1 February 2021 gave rise to a country-wide civil disobedience movement. Originally nonviolent, it was nominated for the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize in March 2021. The nomination recognised the CDM’s role ‘in forging a positive agenda for substantive democracy and peace’. One of the nominators declared that the CDM members ‘are risking arrests, torture and death, yet have chosen to fight for their freedom through labour strikes, peaceful assembly and non-violent resistance’.2 This paper explores the circumstances in which large-scale civil resistance can have impact on a military coup and regime change, and examines the relationship between popular nonviolent mobilisation, democratisation, social politicisation and the defence of human rights and freedoms. However, it also analyses the escalation of Myanmar’s civil conflict when the national unity government (NUG) declared war on the military; civilians began to form civilian defence forces (CDFs), while some of the EAOs (ethnic armed organisations) supported the pro-democracy movement by launching offensives against military and other security bases. Mathieson (2021a) warns us against prescriptive or generalised models, ‘While contemporary scholarship pushes the idea of a neat resistance complex, Myanmar is a country with a kaleidoscope of ethnicities, religious communities and different political views’. ‘By definition, it’s going to be incredibly complicated, messy, and dysfunctional because that’s just the reality of the situation’. Other critics also note that what have been called the moral–humanitarian approaches to Myanmar’s conflicts can ‘dehistoricise’ and ‘deculturise’ the conditions in which events take place, and that the fluidity of power relations in Myanmar, their inherent contradictions and the mix of cultural and political legitimacy that sustains these power relations may evaporate in description and analysis. This paper therefore seeks to understand the circumstances that have enabled Myanmar’s armed forces to crush peaceful resistance, and which have led to civil war and the widespread and rapid erosion of order and security. It examines the reasons that have led many pro-democracy activists to believe that justice and other virtues may require them to fight or even to sacrifice their own lives and considers wider questions of our own responsibility as citizens of one interdependent world to protect the security and peace of others. (See Appendix A, Figure A1.)

2. The Military Coup d’état of 1 February 2021, and Its Immediate Consequences

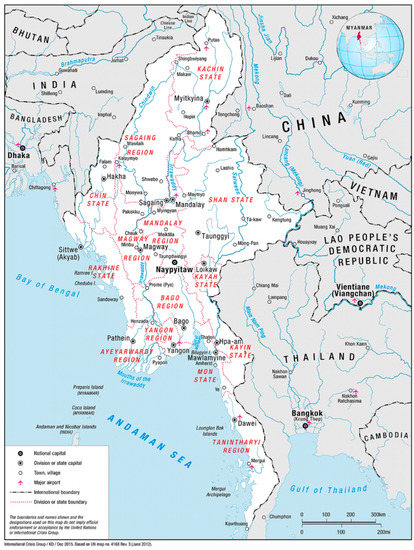

On 1 February 2021, the Tatmadaw3 staged a coup in the name of democracy, detaining State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, President U Win Myint and other government ministers. It took control of the government and instituted a one-year state of emergency, with the Commander-in-chief of the Myanmar Armed Forces, Min Aung Hlaing, serving as the Chairman of the State Administrative Council (SAC) and the country’s de facto leader.4 In August 2018, the UN Human Rights Council stated that: ‘Myanmar’s top military generals, including Commander-in-Chief Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing, must be investigated and prosecuted for genocide in the north of Rakhine State, as well as for crimes against humanity and war crimes in Rakhine, Kachin and Shan States’. In 2021, Min Aung Hlaing assumed all state power in his capacity as commander-in-chief and brought back full military rule following years of quasi-democracy.

The Tatmadaw had dominated Myanmar for six decades and in February 2021 was a well-equipped force commanding some 300,000 to 350,000 troops, relatively modern foreign military equipment, and a range of allied small militias and Border Guard Forces. Its troops are indoctrinated to regard themselves as the guardians of the unity, stability and sovereignty (the three ‘national causes’) of the nation, and Myanmar’s many ethnic minorities, who make up roughly a third of Myanmar’s population, have faced decades of military repression, Although the military shared power with democratically elected representatives during the five years preceding the coup, it continued to enjoy many privileges and retain its vast business interests and conglomerates, particularly Myanma Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL) and Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) and their vast stakes across the economy. The internal workings of the Tatmadaw are opaque, but researchers increasingly recognise that the latest generation of men and women in the security forces have grown up in a different cultural environment than their predecessors and have a range of opinions. It is known for example that some men and women and their families in the services supported the NLD in the November 2020 elections. Moeller (2022) suggests that the coup d’état can best be explained in terms of factional power struggles within the military and argues that mainstream commentaries tend to forego deeper engagement with Myanmar’s complex and heterogenous history, often reinforcing uncomplicated narratives about the monolithic nature of the Tatmadaw in particular.

Myanmar emerged from decades of military dictatorship in the early twenty-first century and in 2011 began a gradual transition to democracy and towards a market economy. The 2008 Constitution created an uneasy balance between military and civilian authority which guarantees the army’s control of three powerful ministries (home affairs, defence, and border affairs), a quarter of the seats in parliament and a veto over constitutional change. In 2010, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), then closely aligned with the head of the Myanmar military government, General Tan Shwe, won the national election. Although the main pro-democracy party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), boycotted the poll and other opposition groups alleged widespread fraud, the election represented a degree of liberalisation. Aung San Suu Kyi’s victory in the 2015 general election raised hopes for constitutional reform and Myanmar’s successful transition to full democracy. On 8 November 2020, Myanmar held its third general election since 2010. The electorate voted overwhelmingly for the NLD and brought to a crisis the unresolved power struggle between the government’s civil and military wings.5 The NLD won by a landslide in the Upper and Lower Houses of the Union Parliament and in Regional and State legislatures. General Min Aung Hlaing, who has throughout the post-coup period claimed legitimacy by presenting the Tatmadaw as the guardian of the peace and stability of Myanmar, justified the military takeover by allegations of vote-rigging.6 The Union Election Commission (UEC) denied these claims, and international observers, such as the Carter Centre and the Asian Network for Free Elections, found no evidence of significant fraud. The generals allege that the Myanmar 2008 Constitution provides them with the legal channel to impose military rule under certain conditions and allows them to take power to prevent any situation that may threaten national solidarity or sovereignty (Regan 2021). However, the Constitution provides that only the President can effectively end civilian rule and transfer the legislative, executive, and judicial powers of the Union to the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services.

Immediately after the coup, General Min Aung Hlaing pledged to schedule free and fair elections after a year and to practise ‘a genuine, discipline-flourishing multiparty democracy’. Aung San Suu Kyi was charged with an array of politically motivated offences which came to include multiple charges of corruption, violations of a state secrets act and a telecoms law.7 Soldiers were stationed in government offices, airports were closed, and, in the cities, the internet was shut down. About four hundred newly elected MPs were placed under house arrest, and the armed forces rounded up chief ministers from all the country’s fourteen states in addition to democracy activists, writers, a filmmaker, and several Buddhist monks who had led the 2007 Saffron Revolution.8

The coup came at a time when Myanmar’s leaders were still grappling with the consequences of British colonial rule and six decades of civil war and military dictatorship. Myanmar has inherited an administrative framework in which ethnicity is central to citizenship, basic rights, politics, and armed conflict, evidenced most powerfully in the violence inflicted since 2017 on the Rohingya minority in Rakhine State which led to 700,000 people fleeing into neighbouring Bangladesh. Military campaigns against other ethnic nationalities along Myanmar’s borders have also created humanitarian crises that continue to be largely ignored by the international community. Recently, there had been armed clashes between Myanmar’s security forces and the Arakan Army (AA) in Rakhine, while years of conflict in Kachin had resulted in widespread food insecurity, disruption of government services, economic stagnation, drug addiction and HIV infection, and protracted displacement. Armed clashes, human rights violations, and landmine contamination continued to pose a significant protection risk, especially in northern Shan. Myanmar therefore had many problems—widespread poverty, transnational criminal networks, illicit economies, rampant methamphetamine production, conflicts involving dozens of armed groups and entrenched humanitarian emergencies. The Burmese people have also been facing medical, economic, and social hardships during the global COVID-19 pandemic. A third wave of COVID-19 infections hit the country, and Myanmar was overwhelmed by the virus after the healthcare system collapsed, along with its COVID-19 testing and vaccination process. Myanmar’s doctors have been under violent attack from the junta as the COVID-19 pandemic rages from a belief that medical staff are the principal exponents of the civil disobedience movement (Krishna and Howard 2021).

3. International Reactions to Myanmar’s Military Coup

Peacebuilding has become a guiding principle of international intervention in the periphery since its inclusion in the United Nations (UN) Agenda for Peace in 1992, and among the many factors that influence the success or failure of nonviolent resistance, the ability to leverage global and regional diplomatic support is often regarded by activists as key. The Myanmar coup sparked immediate outrage from the international community, demands for a return to democracy, the release of Aung San Suu Kyi and other government ministers and targeted attempts to prevent aid reaching the generals. The response from the US, UK and EU was robust, with all three adopting measures designed to pressure the Tatmadaw to reverse course. The USA, followed by other Western democracies, imposed sanctions, and cut financial links with the military junta.9 On February 1 António Guterres, the UN secretary-general, ‘strongly condemned’ the detention of Myanmar’s civilian leaders. The 15-member United Nations Security Council held an emergency meeting on 2 February to discuss Myanmar’s security but stopped short of condemning the military’s actions, releasing instead a press statement on 4 February expressing ‘deep concern’. China, Russia and Vietnam blocked stronger language, and in an interview with The Washington Post Live on 3 February, Guterres acknowledged the disunity in the Security Council. He vowed however to mobilise the international community to put enough pressure on Myanmar to ensure that the military coup failed.

China’s unwillingness to take concrete measures against the military was in line with its long-standing policy of non-interference in what are deemed to be the ‘internal affairs’ of other sovereign states. On the day of the coup d’état, Chinese state media referred to what happened as a ‘major cabinet reshuffle,’ and China’s reluctance to sign off on any criticism of Myanmar or the Tatmadaw led to accusations that China supported the military takeover, a claim which Beijing vehemently denied. Nevertheless, hundreds of protesters demonstrated at the Chinese embassy in Yangon on 11 February accusing Beijing of supporting the military junta (Reuters 2021). China, the country’s largest trading partner and its closest diplomatic ally in recent years, has significant strategic and commercial interests in Myanmar and has funded infrastructure and energy projects throughout the country as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. It blocked UN efforts to address the crisis, instead pushing for the international response to be managed by ASEAN. It has since tried to hedge its bets on the coup regime by supporting efforts of the most powerful actors, including both the junta and the EAOs to safeguard its investments. However, it has traditionally been viewed with suspicion in Myanmar, and it has been argued that one of the factors that initially spurred the move toward civilian rule and quasi-democracy was the army’s concern that the country was becoming isolated and dependent on China (Abnett 2021). Russia has served as a key security partner to the junta and has sold the military sophisticated weapons: jet fighters, helicopters, drones and heavy weapons that they are using against their own people. Regional countries such as India, Japan, Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam were slow to protest against the military takeover. India has followed a twin-track policy—carrying on diplomatic engagement with Myanmar’s military and simultaneously pushing for the country’s return to democracy. Its explicit goal is to ensure security in its northeastern provinces and implicit one is to counterbalance China’s growing influence across South Asia.10 As the fighting has escalated, the governments in Bangkok, Beijing and New Delhi are monitoring events closely. Their concerns relate to influxes of refugees, the spread of COVID-19, cross-border organised crime and increased traffic in drugs, guns, and people.

ASEAN countries, officially the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, at first adhered to the policy of non-interference into the domestic affairs of Member States, a cardinal principle of a regional norm known as the ASEAN Way (Acharya 1998). In recent years, ASEAN has carefully avoided commenting on Thailand’s military coups in 2006 and 2014 and the jails housing political activists in Vietnam, Cambodia, and other member states, as well as on other regional crises. Growing pressure from the West on the junta and mounting violence against pro-democracy protesters prompted several ASEAN foreign ministers to condemn the violence. On 24 April, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing joined heads of state at an ASEAN meeting. Critics feared that this would give him the appearance of legitimacy. However, the leaders in their five-point consensus statement called for (1) the immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar; (2) constructive dialogue among all parties concerned to seek a peaceful solution in the interests of the people; (3) mediation to be facilitated by an envoy of Asean’s chair, with the assistance of the secretary-general; (4) humanitarian assistance provided by Asean’s AHA Centre; and (5) a visit by the special envoy and delegation to Myanmar to meet all parties concerned. The call for a dialogue between all parties was interpreted by some as an attempt to negotiate talks between the junta and the NUG (Wongcha-um and Johnson 2021). The UN, Western countries, and China all backed the ASEAN effort, but the Myanmar military have disregarded the plan, promoting instead their own five-step plan towards a new election (Global New Light of Myanmar 2021).

Immediately after the coup, Myanmar’s citizens repeatedly appealed to the international community to stand in solidarity with them in: (1) asserting their democratic rights, including through nonviolent civil disobedience; (2) upholding the rule of law; (3) protecting democratic process and results, including the 2020 elections; (4) ensuring the preservation of civic space and freedom of journalists and activists; (5) condemning the coup and military violence, and aligning themselves with carefully targeted sanctions against the military and its cronies—not against the people and (6) continuing their humanitarian funding and investment. The hopes and expectations of many Burmese of UN intervention and international protection were gravely disappointed. The international community has provided technical and other forms of nonmilitary support to the NUG and the CDM. offered humanitarian assistance through nongovernmental organisations and UN agencies, and sanctioned military leaders and businesses associated with the junta but has failed to recognise the legitimacy of Myanmar’s pro-democracy leaders. International diplomatic efforts and media reports often focused on the plight of Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD government without comprehending the scale of human rights violations in Myanmar and the fact that a radical agenda charting a more inclusive future for the country had emerged under the CDM and NUG. The NUG has therefore walked a tightrope between domestic and foreign audiences. Its declaration of war against the junta was welcomed domestically, but democratic nations sympathetic to the anti-coup movement such as Britain and the United States expressed concern and called for peaceful efforts to restore democracy. As a result, many CDM activists concluded that the future of Myanmar lies with its people, unconsciously echoing Gene Sharp’s words in 1973, that ‘No outside force is coming to give oppressed people the freedom they so much want. People will have to learn how to take that freedom themselves’ (Sharp 1973). The NUG’s Foreign Minister Daw Zin Mar Aung declared in September 2021 that the international pressure and sanctions on the regime had proved to be ineffective. ‘Therefore, we have to put some momentum into the resistance movement. This is not a shift from a non-violent movement to violence. It is just that we will use all possible means to restore democracy’ (The Irrawaddy 2021b). Many Burmese pro-democracy activists felt that the world was happy to wash their hands of the Myanmar crisis and give ASEAN the responsibility to sort it out. Meanwhile, ASEAN frustration with the Myanmar military grew, and there were even suggestions that the Malaysian government might consider directly engaging with the civilian NUG on a bilateral basis if the five-point consensus remained stalled. In an unprecedented move, ASEAN agreed to exclude the Myanmar’s junta leader from a Brunei summit in 26–28 October 2021, inviting instead a permanent secretary from the regime’s foreign affairs ministry. In a statement the night before the summit, the ministry responded that it had ‘full rights to participate’ and would only accept representation by Min Aung Hlaing or a junta minister.11

4. Civilians as Agents of Change: Tactics of Popular Resistance

Myanmar has suffered decades of repressive military rule and poverty due to years of isolationist economic policies and civil war. It has a history of violent suppression of pro-democracy movements, and its people have lived through three previous coups over the past six decades, in 1958, 1962 and 1988. In 2007, the so-called Saffron Revolution resulted in widespread anti-government protests. News of the 2021 coup therefore provoked a sense of déjà vu (Ducci and Lee 2021). Yet Myanmar was very different from what it had been under military dictatorship. It had undergone a rapid transformation, politically, socially, and economically, a process demonstrated most clearly in Yangon. The Myanmar kyat had become Asia’s best-performing currency, and the World Bank was predicting economic growth in the country despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Although China remained Myanmar’s largest trading partner, its biggest foreign investor in 2020 was Singapore. Japan, South Korea and Thailand had also poured money into the country. Aung San Suu Kyi’s popularity in Myanmar was at an all-time high even though her international reputation was irreparably damaged when she decided to cooperate with the same generals who later ousted her and lead the defence against charges of genocide of Rohingya Muslims at the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

The NLD, in Aung San Suu Kyi’s name, called on Myanmar’s public not to accept the military coup and ‘to respond and wholeheartedly to protest against the coup by the military’. Many Burmese watched the events unfold in real time on Facebook, the country’s primary source of information and news. Within days, however, hundreds of thousands of people from almost every ethnic group, including the Rohingya, gathered in the streets nationwide to denounce the coup and demand the restoration of the democratically elected government.12 Their unity was symbolised by the three-finger salute, a gesture, originating in the Hunger Games film series, which has become a symbol of resistance and solidarity for democracy movements across southeast Asia. From 2 February, Yangon residents began to bang pots and pans every night and honk car horns, practices which became widespread throughout Myanmar. These forms of protest facilitated the broader participation of civilians during the ongoing pandemic and enabled women, young people, the elderly and disabled to make their voices heard. On the same day, organised resistance to the coup started with healthcare workers announcing their decision to boycott state-run hospitals, medical institutes and COVID-19 testing centres. They led the first street protests, calling it the ‘white coat revolution’. This put doctors on a collision course with the junta and resulted in much of Myanmar’s healthcare system going underground. They also established a national civil disobedience movement (CDM) designed to cripple the military’s administrative mechanism.13 This inspired a countrywide refusal of hundreds of thousands of people to work for the military. The CDM Facebook campaign group attracted 150,000 followers within 24 h of its launch (The Irrawaddy 2021c; Frontier Myanmar 2021b). By 3 February, healthcare workers in over 110 government hospitals and healthcare agencies had joined the movement with strikes spreading to other parts of the civil service. They also launched the red ribbon campaign. The colour red is associated with the NLD but also symbolises social disobedience in the face of a military dictatorship (AFP News Agency 2021). The coup threw the country’s economy into crisis as millions abandoned their jobs in protest, including doctors, civil servants, teachers, university lecturers, engineers, bank staff, electricity workers and railway employees. The strikes by government medical personnel and teachers created huge gaps in healthcare and state education that striking colleagues working in private institutions struggled to fill. On 3 February, the ‘Stop Buying Junta Business’ campaign emerged, calling for the boycott of military-owned and military-linked businesses, products and services (Hein 2021).

By 7 February, thousands had taken to the streets to protest, with the largest demonstrations taking place in Yangon, Mandalay and Naypyidaw. Nonviolent tactics included mass protests, street performances, barricades, sit-downs, candlelit vigils, nationwide silent strikes, the use of women’s sarongs (htamein) as flags, painted murals, banners, leaflets, and posters. Symbolic creativity and connectivity were demonstrated by slogans and memes of defiance, the sounding of horns and banging of pots, the three-fingered salute, the red ribbon campaign, and the singing of Kabar Makyay Bu, a song first popularised as the anthem of the 8888 Uprising or the People’s Democracy Movement. Incidents of extraordinary bravery also inspired protesters. On 28 February, photographs of Sister Ann Roza Nu Tawng, under the caption, ‘the Burmese Mother Theresa,’ showing her interposing herself bodily between armed police and nonviolent protesters went viral.14

5. The Military Response

Myanmar’s security apparatus is large, consisting of an army of about 350,000–400,000—most of whom are ethnic Bamar Buddhists, another 80,000 police (who have been relied on heavily to confront protesters), as well as state intelligence service members. The military regime was in the past feared for its readiness to crack down brutally on popular protests, but immediately after the 2021 coup, it exercised unusual restraint. This changed as widespread public protests and mass desertions of the civil service led to the collapse of the economy. Security forces, the police and military, responded at first with water cannons, rubber bullets, tear gas, catapults, beatings and batons. They clamped down on press freedom, arrested reporters, closed news outlets, and drove journalists underground or into exile. Despite intimidation, local and international media continued to find ways to report live events. The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) gave daily briefings on the number of those killed, injured and arrested, while Myanmar Now’s LIVE Timeline: ‘Myanmar’s 2021 Democratic Uprising Against the Military Coup’ captured film and video footage of the use of live ammunition and lethal force, arbitrary detentions and intimidation, threat to the media, and instituting of regulations and laws that systematically stripped away rights and access to information and privacy (UN News 2021). Police and security forces targeted an ever-increasing number of activists and demonstrators, arresting political officials, civil society members, journalists, lawyers, and medical professionals. Stories of horrific abuse relayed by former detainees were later confirmed when the Associated Press published the results of their investigation into the systemic policy of torture across the country (Milko and Gelineau 2021; See also Teacircleoxford 2021). Methods of torture include beatings, mock executions with guns, burning with cigarettes, and rape and threatened rape.

On 8 February, SAC imposed a curfew on major towns and cities across the country and restrictions on public gatherings. By 9 February, there were reports of police shooting water cannon, rubber bullets and live rounds at unarmed crowds in Yangon, Mandalay, and Naypyidaw. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN Human Rights) reported that the police and military confronted peaceful demonstrators using disproportionate force with deaths reported in Yangon and major cities. 20-year-old, Mya Thwe Khaing, was shot in the head when police tried to disperse anti-coup protesters in Naypyidaw’s Zabuthiri township. Two more people were killed when police used live ammunition to disperse protesters in Mandalay (BBC News 2021a). On 28 February, the UN reported that at least 18 people were killed after security forces used lethal violence against protesters.15 On 3 March, a day of protests that was among the deadliest in Myanmar since the coup, it recorded the deaths of 38 people.16 As anti-coup protests continued throughout Myanmar in defiance of military orders forbidding large gatherings, a new element entered the picture: pro-military groups seeking to provoke violence.

Protesters used Facebook to organise the civil disobedience campaign’s labour strikes and the boycott movement, to appeal to international communities and to share photo and video evidence of military brutality. On 4 February, telecom operators and internet providers across Myanmar were ordered to block Facebook until 7 February to ensure the ‘country’s stability’. MPT, a state-owned carrier, blocked Facebook, Facebook Messenger, Instagram and WhatsApp services, while Telenor Myanmar blocked Facebook.17 Following the Facebook ban, Burmese users flocked to Twitter, popularising hashtags such as #RespectOurVotes, #HearTheVoiceofMyanmar, and #SaveMyanmar. On 5 February, the government extended the social media access ban to include Instagram and Twitter. On 6 February, the military authorities initiated an internet outage nationwide and repeated this on 14 February 2021 for 20 days. Meanwhile, a police cybersecurity team worked with state- and military-owned mobile operators to use surveillance drones, iPhone-cracking devices and hacking software. The team also monitored phone users in real time to identify and track regime opponents online.

On 12 February, Union Day, a festival celebrating the unification of the country, the SAC granted amnesty to 23,314 Myanmar prisoners and 55 foreign prisoners. Among those released were supporters of the assassin who killed Ko Ni, the NLD’s legal advisor. From 10 February, the SAC conducted late-night raids to arrest senior civilian politicians and election officials throughout the country. Public fear and insecurity intensified as the military were believed to be using ex-prisoners to carry out nightly acts of violence. Phil Robertson, the deputy director of HRW’s Asia division, told the BBC that there were ‘more and more night-time raids’ taking place in Myanmar, in which people were dragged from their homes in the middle of the night. AAPP also voiced concern about overnight arrests. ‘Family members are left with no knowledge of the charges, location, or condition of their loved ones. These are not isolated incidents, and night-time raids are targeting dissenting voices’.18

6. Myanmar’s Generation Z: “We Want Democracy! Reject Military Coup! Justice for Myanmar!”

We are making our voices heard through our uprising. We hold hands firmly and are working together to end the dictatorship and fulfil our own destiny.We create a battle symphony with the sound of pots and pans!We raise our three-fingered salute!We march!We stage creative uprisings through various forms of collaborative performance!We help each other and show global solidarity!We support the Civil Disobedience Movement!Driven by our strong determination, we remain resilient against the deadly attacks.(Khine and Peter 2021)

Driven by young Burmese who came of age with internet access and the comparative freedoms of the last decade, the civil disobedience movement was organised online, particularly on Facebook. Fear of the past, ‘the dark old days,’ drives young people who had experienced what is possible under a more democratic, liberalised, and globally integrated Myanmar, with many feeling that their parents and grandparents lived their lives feeling fear, not speaking out. Veteran activists from the 1988 uprising talk of the new educated generation (self-portrayed as Generation Z or Gen-Z) as leading a revolution using Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter timelines. They developed a vibrant post-coup digital culture that challenged the SAC’s repressive tactics and surveillance capacity (Loong 2021). Protesters posted live videos on Facebook, and tens of millions of people offered their support online, a stream of hearts and likes for each city’s display of defiance (Nachemson and Mahtani 2021). The Conversation observed that, ‘As a new generation of protesters take to the streets of the country’s towns and cities in growing numbers, they are drawing on a range of internet memes, slogans, cartoons, and cultural symbols to make themselves heard and mobilise support within the country and across the region’ (Dolan 2021). In the first weeks, the atmosphere was carnivalesque. Euronews reported on 10 February that, ‘As they flood streets across the country in opposition to the military coup, a younger generation of Myanmar protesters have dressed up for the occasion in cosplay and Marvel heroes cracking jokes at the military’s expense and winning fans on social media with their colourful and witty signage’. On February 11, news reports showed shamans, shirtless bodybuilders, and ukulele performers among demonstrators in Yangon.19 Protesters also employed culturally gendered and generationally driven tactics. Videos and images were posted of women demonstrating in ballgowns and COVID masks.20 Some carried posters that read: ‘I don’t want a dictatorship. I just want a boyfriend’. ‘Ah shit, here we go again’ and ‘You fucked up with the wrong generation’. The use of humour, satire, and laughter as a way of defying the generals became a general trope.21 The demonstrations were also inspired by celebrities, actors, artists, journalists, film directors, musicians, performers, bloggers, influencers, digital rights activists and tech entrepreneurs, and the military began to target what the media called the ‘creatives’ (Ebbighausen 2021).

Young people in Myanmar and neighbouring Thailand began adopting the Milk Tea Alliance (MTA) in a show of solidarity, and Chia and Singer argue that this regional pro-democracy movement based on Twitter, and not ASEAN, offers a vision for a democratic and federalist Myanmar, and that it has been a central force in shaping the way Myanmar’s youth understand the current battle between pro-democracy protesters and their vastly better armed opponents, ‘a predicament faced by other youth in neighboring countries’ (Chia and Singer 2021). Across Asia, activists held rallies to support protesters, revealing the growing influence of cross-border youth movements pushing for democracy with the rallying cry ‘Milk Tea Alliance’. Pro-democracy campaigners in Taipei and in Bangkok, Melbourne and Hong Kong took to the streets waving #MilkTeaAlliance signs and flags. The hashtag, which originated as a protest against online attacks from nationalists in China, has been used millions of times. Its name originates from the shared passion for the milky drink in Thailand, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Activists in Indonesia and Malaysia held online protests and thousands more, from Southeast Asia and elsewhere, took part in a social media campaign, posting messages and artwork. 22 Young people from the Burmese diaspora also rallied in support. In the US, they staged demonstrations, lobbied the US government, and fund-raised. The Support the Democracy Movement in Burma donated money to striking civil servants who in many cases had lost their income or been evicted from government housing, to representatives of the civilian government and to those displaced by conflict (Nachemson 2021).

As the violence and arrests increased, the crowds on the streets disappeared. In Yangon, groups of mostly young people appeared briefly, shouting slogans and flashing the three-finger salute. Many were forced to return to their home states where resistance was more difficult. Some still found creative ways to inspire revolutionary change and carry on the fight through groups such as the Wired Youth Connecting Myanmar, Twitter Team for Revolution and Federal FM underground radio station. Chiu (2022) reports however that the coup both unites and divides Myanmar’s youth, and that although many young people continue to engage in more direct activities, such as armed resistance, flash protests, or cyber warfare, others have shifted to everyday resistance, such as non-compliance or boycotting military-related businesses. She also found that many young people in Myanmar feel ambivalent towards their disrupted futures and aspirations amid widespread political violence and that the concerns of those who have become more subtle in their resistance have also shifted from being targeted and threatened by the military to being mistakenly targeted and shamed for supporting the military, and from worrying about physical safety to concerns about a lack of progress in their lives. She observes that while the current coup has in one sense united people in the fight against the military, regardless of ethnicity or religion, it also divides them by reducing life decisions to a strict dichotomy between pro-military and pro-democracy.

The political crisis in Myanmar has also demonstrated how the digital world is now an integral part of civil conflict, and that whereas previously social media were places of discussion and debate, they are now linked to many cases of violence.

Whether in Syria, Hong Kong, Thailand, or the United States, online interactions are interwoven with real-world protest, resistance, and violence. Following the military coup of February 2021, protesters organised online and used social media to spread and amplify their voices. The military responded with network shutdowns, control over telecoms, online surveillance, and stop and search of mobile phones. Youth in Myanmar faced an existential crisis. The country’s brief experiment with democracy and an open media environment had seen social media emerge as a place of outspoken discussion and free expression—including the challenging rise of online hate speech and social punishment. Now, that online environment is linked to many cases of arrest, torture, and even death.(Anonymous 2021)

7. Gender Diversity: Women and Girls on the Frontline

Political scientists have long noted that the more inclusive civic resistance is, the more pro-democratic movements are likely to succeed, and that women’s civil rights and democracy go hand in hand. Chenoweth and Marks (2022) maintain that the former is a precondition for the latter. They argue that aspiring autocrats and patriarchal authoritarians have good reason to fear women’s political participation: when women participate in mass movements, those movements are both more likely to succeed and more likely to lead to more egalitarian democracy. Women’s large-scale participation helps movements achieve nonviolent discipline and resilience, and the likelihood of loyalty shifts within pro-government segments of the populations (Codur and King 2015; Principe 2017; Chenoweth 2019). It also promotes the empowerment of women that can be integrated into the peace process and lead to a more inclusive post-conflict society.

In Myanmar, from the beginning, women and girls have been at the heart of the CDM, defying the army’s assault on women’s rights and democracy. In the 2020 November elections, 20% of NLD candidates were women, and women’s organisations were among the first to issue statements condemning the coup and reaching out to the UN and the international community for support. The military takeover threatened the advances made by women in every aspect of the economy, and many CDM protesters represented striking unions of teachers,23 garment workers and medical workers24—industries all dominated by women. The NYT reported (3 March) that, ‘Despite the risks, women have stood at the forefront of Myanmar’s protest movement, sending a powerful rebuke to the generals who ousted a female civilian leader and reimposed a patriarchal order that has suppressed women for half a century’ (The New York Times 2021b). Women have braved teargas and bullets, as equal partners with men. The youngest were often on the front lines. Three young women were among those killed on 3 March, ‘the biggest one-day toll since the February 1 coup’ (The New York Times 2021c). When Kyal Sin, aged eighteen, was shot in the head by the security forces, Ma Cho Nwe Oo, her close friend, declared, ‘She is a hero for our country. By participating in the revolution, our generation of young women shows that we are no less brave than men’ (The New York Times 2021d).

Many women have taken part in anti-junta movements since the coup. However, whereas the majority practise non-cooperation, others are playing an important role in the armed struggle. Myanmar’s women have always been essential in maintaining the support mechanisms that are necessary in warfare, but the reactions of many women reveal that for them, fighting on the front line is a feminist issue. Activists in Myanmar’s Sagaing region formed the country’s first women-only anti-junta militia, a collection of students, teachers, farmers, and white-collar workers fighting to take back the country from well-armed government troops. Amera, a member of the Myaung Women Guerrilla Group (MWGG), told Radio Free Asia’s Myanmar Service that the group was launched to empower women who might otherwise be preyed upon by raiding troops. She said that ‘It is assumed that women’s hands are meant for the rocking the cradle, but we want to show to the people that our hands are also capable of armed resistance to the military regime’. Another protest leader who organised daily actions against the military coup in Monywa told RFA that the formation of an all-women militia was a significant milestone in the resistance movement. ‘The situation [since the coup] has led us to demonstrate that women can do the same jobs as men. I think these resistance movements bring more equality and may help to eliminate discrimination in the future’ (Radio Free Asia 2021).

Women’s determination is all the more extraordinary since they have been disproportionately impacted by the violence. They make up 54% of the 230,000 people internally displaced by internal conflict. Women have also been taken hostage, tortured, and killed in the targeted offensives, and their cases are another stark reminder of entrenched military impunity and longstanding violence against women and girls in Myanmar’s conflict zones. Sexual violence including rape has long been used as a weapon to terrorise victims and their families, and reports of violence against women have become almost normalised (Quadrini 2021).

8. Ethnic Nationalities: From ‘Other’ to Allies?

‘Ever since the Union of Burma was established in 1948, the supposed goal was to create a federation of semi-autonomous democratic states in accordance with the Panglong Agreement. The perceived failure of the Bamar majority and the Tatmadaw to abide by that goal led to the outbreak of Myanmar’s long-lasting civil war and the first military coup in 1962 (Martin 2021). Since independence, discrimination has been engrained in Myanmar’s laws and political system. For decades, the state has waged military campaigns against ethnic nationalities, notably the Rohingya, a mostly Muslim minority group indigenous to Rakhine State. The Rohingya crisis led to a broader spike in anti-Muslim sentiment, raising anew the spectre of communal violence that could endanger the country’s transition to democracy. After the coup, many ethnic minorities feared that military rule would bring even greater oppression.

Among the most positive signs of the growing resistance movement was the presence of Kachins, Karens, Chin, Shan and Rohingya in the early street protests. Myanmar’s ethnic groups hoped that by protesting side by side against the junta, it would be possible to build a more equitable and federal Myanmar. The coup, and the violent crackdowns on protesters that ensued, turned out to be something of a game-changer.25 Many Bamar, Kachin, Chin, Shan, and Karen put aside their differences to focus on a common enemy, and as the army’s crackdowns on pro-democracy protesters reached into the Bamar-dominated central regions, many Bamar experienced the kind of oppression that ethnic and religious minorities had endured for decades. Bamar-majority communities became more conscious of the atrocities and injustices suffered by ethnic nationalities. This ‘awakening’ was welcomed by many young Bamar. Thi Zinh, for example, declared, ‘Today, everyone is living with Tatmadaw’s brutality. Bamars realise what other ethnic groups experienced daily during all these years’ (Cabot 2021). Although Myanmar’s resistance movement might have begun with the demand for the restoration of the democratically elected government, ethnic minorities renewed their call for a new constitution which would finally give them the rights they have been demanding for the past 70 years.26

On 31 March 2021, the government in exile, the CRPH, hoping to woo the country’s armed ethnic militias to ally themselves with the mass protest movement, announced that it considered the 2008 constitution void and that it was drafting a new charter, guaranteeing the creation of a federal state and handing more power to minorities. In June 2021, the NUG issued a new policy on the Rohingya promising to end human rights abuses against them and grant them citizenship. It declared its intention to repeal laws, including the 1982 Citizenship Law, which discriminate against the Rohingya and other ethnic groups deemed non-indigenous. It made a commitment to abolish the National Verification Card process. NUG policy now states that “This new Citizenship Act must base citizenship on birth in Myanmar or birth anywhere as a child of Myanmar citizens’. The NUG’s determination to extend citizenship rights has been welcomed by many NUG supporters but is proving divisive, particularly in Rakhine.27

Even though many ethnic groups were represented in the nonviolent protests, they have competing views of federalism and extremely diverse interests and motives. EAOs have chosen different political and military positions despite the widespread belief that the coup has unified different forces against a common enemy (Hmung 2021). EAOs who did not sign agreements with the government, particularly the nationwide ceasefire agreement (NCA) in 2015, feel that their ‘armed/violent’ approach towards the military has been vindicated. Ong points out that the EAOs have ‘vastly different worldviews, military capabilities, and working languages, some leaning politically towards China and others towards Western countries’ (Ong 2021). Mathieson observes that there was always the likelihood that some EAOs would resort to defensive violence while others would seek accommodation with the Tatmadaw (Mathieson 2021b). Several of the major groups—including the Kachin in the north, the Karen in the east and the Rakhine Arakan Army in western Myanmar—publicly denounced the coup and stated that they would defend protesters in the territory they control (ABC News 2021b). This shift became even more significant at the end of March 2021 when a number of ethnic rebel groups announced that they were joining the pro-democracy fight against the junta, calling the country’s youth to join them. Ten of the country’s main rebel groups stated that they would ‘re-examine’ the ceasefire deal they entered with the army in 2015.

Martin (2021) notes that a major role for the EAOs in the post-coup period is providing protection for thousands of activists and civilians fleeing the oppressive conduct of the military junta—including many of the members of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH). An undisclosed number of the CRPH members reportedly have fled to KNU-controlled territory to avoid detention. Activists and civilians have also relocated into EAO-controlled areas of the States of Kayin, Mon, and Shan and some EAOs began to provide limited weapons, training, and tactics to the PDFs and CDM resisters. In an interview with the English-language newspaper Frontier, a young KIA recruit said that dozens of Kachins and non-Kachins had joined the group and that most new recruits were in their 20s, and between 20% and 30% were women (Fishbein et al. 2021). The Irrawaddy reported (October 2021) that the junta-controlled Burmese-language newspaper, Myanma Alinn, accused six EAOs of aiding and abetting so-called ‘terrorist’ attacks in Myanmar, and that the Karen National Union (KNU), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), the Chin National Front (CNF), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP) and the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) were taking advantage of the political turmoil in the country and providing military training to the PDFs for their own advantage. Although some EAOs are providing military training to hundreds of young dissidents who have fled to areas under their control for sanctuary, these groups are not organised by the NUG and are not under its command, although they may share its objectives. The same is often true of the hundreds of militias which have popped up across the country, many identifying themselves as PDFs.28 Mcpherson and Naing (2021) write that this is a fight that in a few months made guerrilla fighters of university lecturers, day laborers, I.T. workers, students and artists and forced countless young men and women into a life on the run. The Myanmar Study Group reports (2022) that several EAOs, such as the Arakan, Kachin, Karen, Shan, and Wa forces, have used the situation to expand their territorial control in defiance of military domination, gaining significantly greater autonomy over their own administration. PDF fighters have gained battle experience by joining EAOs in fighting the military. However, although all EAOs hold in common a bottom line that the military’s actions have deeply damaged their security and economic prospects, they are far from having a shared vision of Myanmar’s future.

9. Weakening the Enemy from Within: Defections and Desertions

Lacking any popular mandate, the generals rely entirely on the state’s coercive apparatus to exercise power and maintain controls over the civil population (Selth 2021). One of the reasons often given for the success of strategic nonviolent civil resistance is that members of the army or police develop sympathy with unarmed civilians and refuse to fire on them. A key part of campaign success is to shift the loyalty of the military away from the dictator and toward the opposition. Political analysts argue for example that the military’s decision to remain loyal to the regime or to side with civil resisters heavily shaped the outcomes of the Arab Spring uprisings. In Myanmar, Generation Z calls soldiers planning to defect ‘watermelons’. The green skin of the fruit recalls the colour of the military uniform, while the red flesh is the colour of the NLD. Soldiers are often sequestered in military compounds without good internet access and acquire their information from military-dominated media. (On 25 February 2021, Facebook and Instagram banned the Myanmar military and its businesses from using its platforms because of the deadly violence.) However, a steady increase in defections and desertions since the coup amid plunging morale had some observers questioning whether unity can be maintained within the Tatmadaw. Many defectors claim that the soldiers are tired and demoralised, and some count on a damaging split within the military high command, with one faction going over to the pro-democracy side. As the protests continued, defections from the Myanmar Police Force increased. On 5 March 2021, a group of eleven officers crossed the India–Myanmar land border to Mizoram state with their families because they refused orders to fire rubber bullets and tear gas shells at the protesters (BBC News 2021c). As a result, the Assam Rifles were ordered to tighten security along the India–Myanmar border. By 5 March 2021, more than 600 police officers had joined the anti-regime movement (The Irrawaddy 2021e). From 10 March, the border was closed after 48 Burmese nationals crossed. Some military personnel also abandoned their posts to stand in solidarity with the people, citing corruption among the high-ranked military officers and the lack of will to kill their own people as the main reasons.

Although political strategists maintain that nonviolent resistance encourages the defection of military and police personnel, evidence from Myanmar shows that any serious attempt to divide the army or to create a split between the army and police force could result in more bloodshed, and that any breakdown in discipline would be rapidly crushed (Selth 2021). Defectors put themselves, their families, and associates in mortal danger. There are no safe spaces to hide, and defectors are often forced to flee to India or join the PDF. A team of Myanmar activists is using social media and messaging apps to encourage junta soldiers to defect from the military, and there are now ex-military associations that seek to topple the military by weakening it from within. People’s Embrace which is run by the NUG claims to have facilitated the defections of a group of 2000 security forces personnel while a non-military organisation, People’s Soldiers, encourages, facilitates, and supports defections by the national soldiers of Myanmar (Bociaga 2021a). Its website (https://www.peoplesoldiers.org/) states that only when the national soldiers of Myanmar stand for justice and join the people will this revolution have the least blood spilled and the highest chance of victory. The People’s Soldiers Production Team has also begun an arms manufacturing operation known as Project A-1 to support the PDF’s resistance efforts. By 15 February 2022, it was reported that over 16,000 soldiers and police officers had joined the CDM to fight against the military.

10. Civil Society and Democratisation

The resistance movement of civil society has been channelled through institutional channels and grassroots movements. Initially, the responses of international peace organisations including the 2000-strong UN contingent in Myanmar were uncoordinated. The two most senior UN officials, the Resident Coordinator and Humanitarian Coordinator (Ramanathan Balakrishnan) and the UN Special Envoy (then Christine Shraner Burgene) had previously been based outside Myanmar, and civil society organisations (CSOs) were at first uncertain whether to engage in mediation attempts with the generals or distance themselves. Their responses became increasingly robust and united. Human Rights Watch (2021) demanded a tough approach, ‘Coordinated international and multilateral actions in response to the coup should include targeted economic sanctions on the military itself, its leadership, and its vast economic holdings, which provide the military with its revenue, as well as embargoes on military arms and equipment’. An HRW spokesperson stated, ‘The military’s outrageous assault on democracy, following atrocities against the Rohingya, should be a clarion call for the world to act as one to finally get the military out of politics and put the interests of Myanmar’s people ahead of all other considerations’.

Myanmar’s civil society and ethnic organisations also issued joint statements condemning the coup and urging action by the international community. Many cited the principle, Responsibility to Protect (R2P or RtoP), a global political commitment which was endorsed by all UN member states at the 2005 World Summit to address its four key concerns to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. Since the coup, women’s rights and women-led civil society organisations have played a leading role in supporting the national response. The Organizations/Networks Working for Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, a network of more than thirty organisations set up to support community women’s groups across Myanmar, released an early joint statement on 4 February 2021. It declared that the current political situation, during the period that the whole country was facing the COVID-19 pandemic, was threatening the economic, physical and emotional security and stability of all people, including women and children, as well as critically undermining the ongoing process of peace building, democratisation and federalism in Myanmar (Alliance for Gender Inclusion in the Peace Process 2021). On 12 February, 177 Myanmar CSOs signed a joint open letter to the UN Security Council pleading with it to dispatch an urgent enhanced monitoring and intervention mission to Myanmar to monitor the fast-evolving situation on the ground and mediate between parties. The letter urged the Council to ‘support Myanmar to achieve a roadmap that establishes a federal democratic union, ensuring a long-term sustainable peace, ethnic equality, and protection of the human rights of all peoples, and implements constitutional change that is in line with the will of the people’ (177 Myanmar Civil Society Organizations 2021). On 17 February, 219 CSOs signed a joint letter to the international community, and in particular to International Financial Institutions (IFIs) and State Donors, asking them to freeze loans and comprehensively reassess their lending relationship with Myanmar, respect calls to condemn the coup and military violence, and align with strong targeted sanctions against the military and its cronies (Forum Asia 2021). Forum-Asia also released statements calling upon ASEAN to block Myanmar’s military junta participation from all its platforms and engage with the National Unity Government.29

11. Religious and Moral Leadership

Close to 90% of the population of Myanmar identify as Buddhists, and many thousands have participated in the resistance movement. Monks, collectively known as the sangha (community), are venerated members of Burmese society who possess supreme moral authority and considerable political power. Monks led demonstrations against the generals in 2007 but have been far less prominent in 2021–2022, and some reports speak of a schism within the sangha. Many senior monks have been silent or have given their blessing to the Tatmadaw whereas more junior monks, particularly in Mandalay, the traditional centre of Burmese Buddhism, have been more likely to join the protests. Immediately after the coup, videos and tweets showed groups of Buddhist monks and thilashins (nuns) demonstrating in Yangon and Mandalay. On 15 February, a group of monks were filmed carrying signs and banners saying, ‘reject military coup’ and ‘monks who don’t want a military dictatorship.’30 A few Buddhist monasteries and educational institutions denounced the coup, among them the Masoyein monastery in Mandalay and the Mahāgandhārāma monastery in Mamarapura. Some monks and thilashins have organised protest marches and campaigns against the military or offered aid and shelter to victims of violence. Others have refused alms from soldiers, their families, and supporters, thus denying them the opportunity to accrue good karma. Hundreds of lower-ranking monks have been jailed for protesting, and a few have disrobed to join the PDF.

Since the start of the political liberalisation in 2011, Myanmar has been troubled by an upsurge in extreme Buddhist nationalism, anti-Muslim hate speech and deadly communal violence, not only in Rakhine state but across the country. Nationalist monks and nuns were among the fiercest champions of the violence that drove nearly a million Rohingya into Bangladesh and neighbouring countries in 2017. They promote a radically cohesive national identity and sense of belonging based on a longstanding Buddhist heritage (Borchert 2014, p. 603) and preach that Buddhism and the Buddhist way of life are threatened by an internationally resurgent Islam. The fusion of ethnocentric nationalism and religion led U Ashin Wirathu and monks associated with the 969 Movement and Ma Ba Tha (Association for the Protection of Race and Religion) to fuel fears about Islam and Muslims (Walton 2013; Walton and Hayward 2014; Borchert 2007, 2014; Schonthal and Walton 2016; Fuller 2021). In 2019, Ashin Wirathu was charged with inciting ‘hate and contempt’ against the NLD civilian government but significantly was released by Myanmar’s military junta in September 2021. Sitagu Sayadaw, Myanmar’s most influential monk, participated in the Saffron Revolution but is also known for his support for the military. His narrative of a Buddhism justified in suppressing the Muslim community has been the dominant narrative within Myanmar. He stayed silent after the coup even as security forces killed unarmed demonstrators. Finally, Sitagu International Buddhist Academy released a statement urging the government to act in accordance with the principles of the Dhamma and welfare of the people (Insight Myanmar 2021a). In line with Buddhist teachings, it mentions principles only and does not offer public guidance. As the military violence intensified, Shwekyin Nikāya, Burma’s second largest monastic order, sent a letter to General Min Aung Hlaing expressing dismay and concern about the current situation in Myanmar. Its leading monks, who include Sitagu Sayadaw, ask the general to behave with mettā (lovingkindness) and according to the ten moral practices of the king/ruler of Buddhist tradition (see also Insight Myanmar 2021b).

Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN’s) Executive Director Kyaw Win urged the Burmese military to release the three monks, Ashin Ariya Vansa Bivansa (Myawaddy Sayadaw), Ashin Sobitha, and Shwe Nya Warand, who had been imprisoned for opposing toxic religious nationalism. He noted that ‘Burma’s military has long fostered a relationship with violent nationalist monks and silenced those seeking peace and harmony in the society’ (Kartal 2021). Buddhist nationalism often manifests as a kind of ethnocentrism in which protecting the Myanmar–Buddhist identity is highlighted in propaganda and Islam is portrayed as an existential threat to the faith and the nation. The army’s support of nationalist monks has often been apparent, and many observers feared that the regime would seek to weaponise religion and mobilise support by appealing to Buddhist nationalist sentiment (Ford and Oo 2021). Hardig and Sajjad argued that the military coup presented opportunities to Buddhist nationalists which might exacerbate Buddhist nationalism and extremist religious ideals (Härdig and Sajjad 2021). Artinger and Rowand (2021) reported that days before the February coup, Buddhist monks marched through the streets of Yangon, carrying banners claiming election fraud, and proclaiming the military as the protector of the state. They comment that such scenes are not uncommon in Myanmar, where Buddhism is deeply intertwined with the country’s culture,

For the Buddhist nationalists who backed the army and its crackdown on Muslims, the coup may seem like an opportunity. Westerners rarely associate Buddhism with extremism or violence, but Buddhist movements in Asia have often raised few qualms about the use of force. Buddhist authorities have, at times, justified violence against the faith’s enemies and supported authoritarian regimes. Myanmar is no exception. Since at least the end of British rule, the Buddhist monastic community (or sangha) has played an instrumental role in the political landscape of Myanmar.

In Myanmar, the mobilisation of national or ethnic identity based on religion has often served as a source of social division. However, after the coup, religion also functioned as an institutional and ideological connection with the international order. Burmese community groups within the country’s diaspora and international Buddhist organisations sprang into action. Partnering with vetted intermediaries in Thailand and Myanmar, these groups continue to disperse aid in grants and in-kind support on the ground within Myanmar (Aung 2021).

The Catholic Church played a particularly impressive role immediately after the coup. On 7 February 2021, Pope Francis declared: ‘In this very delicate moment, I want to again assure my spiritual closeness, my prayers and my solidarity with the people of Myanmar’. Priests, nuns, and seminarians in Myanmar demonstrated their support for the protesters by holding placards and banners in front of churches. On 3 February, Cardinal Charles Maung Bo, the Catholic archbishop of Yangon, appealed to the people of Myanmar to remain calm and not resort to violence. He promoted dialogue and mediation as the only way forward.

I share deep fellowship with all of you in this moment as you grapple with the unexpected, shocking events that are unfolding in our country. I appeal to each one of you, stay calm, never fall victim to violence. We have shed enough blood. Let not any more blood be shed in this land. Even at this most challenging moment, I believe that peace is the only way, peace is possible. There are always nonviolent ways for expressing our protests. The unfolding events are the result of a sad lack of dialogue and communication and disputing of diverse views. Let us not continue hatred at this moment when we struggle for dignity and truth. Let all community leaders and religious leaders pray and animate communities for a peaceful response to these events. Pray for all, pray for everything, avoiding occasions of provocation.(Catholic Archdiocese of Yangon 2021)

The archbishop also addressed the international community. He thanked them for their concern and ‘compassionate accompaniment’ but implored them not to adopt violent measures:

…history has painfully shown that abrupt conclusions and judgements ultimately do not benefit our people. Sanctions and condemnations brought few results, rather they closed doors and shut out dialogue. These hard measures have proved a great blessing to those super powers that eye our resources. We beg you do not force concerned people into bartering our sovereignty. The international community needs to deal with the reality, understanding well Myanmar’s history and political economy. Sanctions risk collapsing the economy, throwing millions into poverty. Engaging the actors in reconciliation is the only path.

Religions for Peace-Myanmar (RfP-M), which includes all Myanmar’s major religions, employed its many transnational links to appeal for the immediate release of political detainees, the restoration of civilian governance, and the promotion of peace and reconciliation efforts. RfP leaders continue to issue joint statements expressing interfaith solidarity against violence, urging peaceful negotiation and warning that pursuing military solutions leads only to endless war and endless misery. However, many now despair that Myanmar’s serious civil conflict can only be healed by deep dialogue and reform. Al Haj U Aye Lwin, the chief convener for the Islamic Centre of Myanmar and founding member of RfP-M (Lwin 2021), emphasised in a webinar on 11 June 2021 that religious leaders must keep trying to mediate in a way that is nonpartial but show an absolute commitment to democratic principles and a zero tolerance for militarism or totalitarianism. RfP statements are often coded in the language of human rights and ‘inclusive citizenship,’ which has reoriented religious support in favour of religious freedom, religious pluralism, and full and equal citizenship between religious communities.

12. The CRPH and NUG: ‘Taking Back the People’s Power’

Many Burmese believe that the outcome of the Myanmar Spring Revolution now largely depends on the capacity of institutional leaders to consolidate opposition forces. The elected members of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (Union Parliament), mostly from the NLD, attempted to provide Myanmar’s institutional leadership by forming the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH). It offered key positions in its council to minority politicians, including representatives from the Kayah State Democratic Party, the Ta’ang (Palaung) National Party and the Kachin State People’s Party. The formation of an alternative government-in-exile, the NUG, by the CRPH was widely welcomed. Often called the ‘shadow’ or ‘underground’ government because its ministers are in hiding, either in areas controlled by ethnic armed groups or in exile abroad, its radical programme calls for a federal democratic union with an army accountable to the civilian government and a government that respects the human rights of all citizens. It is constituted as a coalition of democratic forces in Myanmar, including representatives from the country’s ethnic groups, formed under the terms of the Federal Democracy Charter, which the CRPH made public in March 2021.

On 5 March 2021, the CRPH announced its political vision, declaring its commitment to end military dictatorship; ensure the unconditional release of all unlawful detainees including President U Win Myint and State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi; achieve fully fledged democracy; rescind the 2008 Constitution and write a new federal Constitution. The CRPH stated that it would work steadfastly with all ethnic nationalities and strive for the full realisation of this vision. To pave the way for broader participation in the Spring Revolution, the CRPH removed all the ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) from the ‘unlawful organization list‘ while designating the Tatmadaw a ‘terrorist organization‘. On 31 March 2021, the CRPH abandoned the 2008 Constitution and presented a Federal Democracy Charter (2021) as an interim constitution which aims to end Myanmar’s long history of military dictatorship as well as meeting the longstanding demands of its ethnic minority groups for greater autonomy in their regions. The Charter states,

To bring an end to the conflicts and problematic root causes in the Union, to ensure all ethnic nationalities—population can participate and collaborate and to build a prosperous Federal Democracy Union where all citizens can live peacefully, share the common destiny and live harmoniously together; a Federal Democracy Union where democracy is exercised and equal rights and self-determination are guaranteed, all ethnic nationalities of the Union, all citizens enjoy mutual recognition and respect, mutual friendship and support and solidarity based on freedom, equality and justice, we intend to carry out the following activities:

The anti-junta movement’s determination in the face of the Tatmadaw’s escalating violence resulted in the growing belief that the people had the right to defend themselves and that military conflict might be necessary to defeat the coup (Reuters Asia Pacific 202131; Regan et al. 2021). The NUG declared on 5 May 2021 its intention to establish a ‘People’s Defence Force’ to protect civilians as a prelude to establishing a Federal Union Army and called for unity and pan-ethnic solidarity. On 8 May, the junta responded by adding the NUG, PDF and CRPH to its list of ‘terrorist organizations’. The notice accused them of inciting the Civil Disobedience Movement to commit ‘violent acts’, including riots, bombings, arson and ‘manslaughter’. ‘We ask the people not to … support terrorist actions, nor to provide aid to the terrorist activities of the NUG and the CRPH, which threaten the security of the people’. Previously, the junta had declared these groups ‘illegal associations’ and warned that any contact with them would be considered high treason. But this new classification as a ‘terrorist organization’ means that anyone who communicates with its members, including journalists, could be prosecuted under the country’s anti-terrorism laws which carry heavy prison sentences.