Abstract

Kippbild hermeneutics, developed on the basis of Wittgenstein’s model of Kippbilder, can be understood as a specific postmodern method of coping with (religious) conflicts by relativizing their differences as different ways as seeing as. While it would at first seem that Kippbild hermeneutics enables a relativistic understanding of religious differences, I would like to show that it entangles us ever deeper in the moment in which we understand that the hidden assumption of our (“humanist”, “liberal”, “postmodern”) tolerant superiority towards other groups (e.g., religions) is precisely the moment when we conform to the image we have of the other group. This uncanny experience is what I call a negative aha-moment, and I claim that it could be a means to anticipate the very need for what Paul Mendes-Flohr calls “dialogical tolerance”.

1. Introduction

In his text “Dialogue and the Crafting of a Multi-Cultural Society”, Paul Mendes-Flohr explored the following problem: On the one hand, (monotheistic) religions may engender intolerance. On the other hand, both a “laissez-faire conception of tolerance” (based on an “easy acceptance of a heterogeneity of values and ways of life”) and an “ad hominem tolerance” (where it is the “human being hidden beneath the façade or exterior of particular faith and cultural affiliations who is to be tolerated”) tend toward relativism and the playing down of religious differences. Mendes-Flohr pleads instead for dialogue and “dialogical tolerance” (Mendes-Flohr 2017, p. 313).

This essay addresses a similar topic but departs from Mendes-Flohr in three ways: First, I start from a specific postmodern form of coping with religious conflicts by relativizing their differences, one that does not operate with a universal notion of the human being or of a universal religious experience, but with what I call a Kippbild hermeneutics seen as a method for understanding differences as different ways of seeing as. Second, I focus not on dialogue, but on disagreement as an expression of a limit of dialogue. Third, while Mendes-Flohr refers to Buber and the journal Die Kreatur (1926–1929/30), my approach is substantially inspired by Wittgenstein’s elaboration of the Kippbild (ambiguous image) from 1930.

It would at first seem that a Wittgensteinian model of Kippbilder enables a relativistic understanding of religious differences. I would like to show, however, that his approach entangles us ever deeper in the moment in which we understand that the hidden assumption of our (“humanist”, “liberal”, “postmodern”) tolerant superiority towards other epistemic approaches or groups (e.g., religions) is precisely the moment when we conform to the image we have of the other group. This uncanny experience is what I call a negative aha-moment. By reinforcing what can be called intellectual or epistemic humility, this negative aha-moment can help counteract an arrogance which seems to be inherent in (non-dialogical notions of) tolerance and provide a basis for the encounter with the Other in dialogue.

I proceed in three steps. Step one discusses Mendes-Flohr’s understanding of dialogical tolerance and its strength as well as, using the example of a prominent contemporary Christian-Jewish dialogue, its limit. Step two turns to (political) Kippbild hermeneutics and its application to inter-religious conflicts, more precisely, to so-called aspect-blindness, that is, the inability to see something as something, and the (interreligious) conflicts that (allegedly) arise from it as well as the ability to see aspects as the (alleged) solution to these conflicts. After problematizing this understanding, I conclude in step three that the distinction between “seeing” and “seeing as” has a hidden political dimension that is inscribed in it from the outset. Based on Wittgenstein’s radical-self-enlightening movement of thought, it is possible to develop a model that shows how a reductive Kippbild hermeneutics is already at work when we devalue others and valorize ourselves. The negative aha-moment confronts us not only with our attitude of superiority towards others, but more radically with the non-otherness of the image we made of the Other and thus deconstructs an obstacle to the encounter with the Other. The very problem of (non-dialogical) tolerance (i.e., its attitude of superiority) that the concept of dialogical tolerance addresses by means of dialogue and by emphasizing the otherness of the Other is therefore addressed in political Kippbild hermeneutics in a different, a negative or deconstructive way.

2. Dialogical Tolerance and Its Limits

In his text “Dialogue and the Crafting of a Multi-Cultural Society”, Paul Mendes-Flohr addresses some problems of the relationship between religions and multicultural societies. Religious faith, especially of biblical or theistic inspiration, may engender intolerance. However, humanistic essentialism, as well as a universal phenomenology of religious experience, easily leads to cultural and religious relativism by downplaying religious differences. Starting from this tension between intolerance and relativism, Mendes-Flohr emphasizes the importance of the notion of dialogue, or, more precisely, of “dialogical tolerance”, (Mendes-Flohr 2017, p. 312) which he understands as a “theological virtue” (Mendes-Flohr 2017, p. 315).

It is this very understanding that, according to him, became a programmatic part of the interfaith journal Die Kreatur between 1926 and 1929. The very term “Kreatur” (creatureliness) reveals the connection between “dialogical tolerance” and “theology” (Mendes-Flohr 2017, p. 316):

“Hence, within the sphere of theistic faith, dialogical tolerance finds in the concept of creatureliness a theological ground analogous to the humanistic notion of our universal humanity. But creatureliness is not to be construed as a mere synonym or metaphor for the humanistic notion of a common humanity. By virtue of a consciousness of one’s creatureliness, one assumes a bond with one’s fellow human beings—or divinely graced creatures. One is thus bonded to the others not only by dint of common anthropological features, but also because of a sense of shared origins, destiny and responsibility before the transcendent source of life.”

Despite the lofty concept of “dialogical tolerance” we find in Die Kreatur, dialogue was not for all that perceived as, for example, love is in Christianity, that is, as a value in itself. As Mendes-Flohr indicates, Die Kreatur was first going to be called Greetings from the Lands of Exile, with the assumption being that each of the monotheistic faiths were locked in doctrinal and devotional exile from one another, an exile that would be overcome only with the eschaton (Mendes-Flohr 2017):

“Until that blessed hour, however, they could only graciously greet one another from across the cultural barriers that separate them. ‘But what is permissible’, the inaugural editorial of Die Kreatur noted, ‘and at this point in history mandatory, is dialogue: the greeting called in both directions, the opening or emerging of one’s self out of the severity and clarity of one’s self-enclosedness, a dialogue (Gespräch) prompted by a common concern for created being’.”

In other words, dialogue between monotheistic faiths is limited twice over. It is limited temporally, owing to what one might call the fallen condition of the world, and it is limited in terms of content. The dialogue revolves around a “common concern for created being”. As far as matters of faith are concerned, however, no dialogue is possible, but instead only friendly “greetings” over the precipice by which monotheistic traditions are strictly separated.

The strength of the concept of dialogical tolerance lies in the fact that it combines the acknowledgment of a common ground (the idea of our creatureliness as common feature of the Abrahamitic traditions) with the acceptance of true (religious) differences, an alterity that cannot even be bridged by interreligious dialogue. This recognition of genuine alterity represents an important advance because it provides a more symmetrical relationship between different (religious) perspectives and overcomes the attitude of superiority for which tolerance was already criticized by Immanuel Kant when he spoke of the ‘arrogant name of tolerance‘ (Kant 1996, p. 21).

However, this strength also displays the weakness of the concept. Firstly, the presupposed notion of creatureliness in Die Kreatur does not unite all religious traditions, let alone all non-religious traditions. Its recognition, therefore, can only be assumed in specific, e.g., Abrahamic traditions. The same applies, secondly and more importantly, to the question of how interreligious dialogue can and cannot be conducted. This question is not religiously neutral, and it cannot be assumed that different religions have a common understanding of it, not even the Jewish and the Christian traditions.

This was shown most recently in a debate between Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict and Rabbi Arie Folger, which I have analyzed more closely elsewhere (Di Blasi 2020). In this debate, Folger emphasizes from the outset the mutual recognition of each other’s religious autonomy. Ratzinger replies to Folger by emphasizing that, “as far as humans can foresee”, this dialogue within an ongoing history would “never lead to an agreement between the two interpretations: this is God’s business at the end of history”. (Benedict 2018b). Folger received this statement very positively, because to him it signified that “dialogue is for understanding and friendship but it should not be thought of as a missionary quest or as being about the negotiation of theological points” (Folger 2018).

Ratzinger, again, seemed to agree by underscoring the dialogical character and the specific relationship between Christianity and Judaism. While the Christian mission to all the nations was universal, the Jews were the exception, because “they alone among all peoples knew the ‘unknown god’”. As a result, there could be no mission concerning Israel, but instead “a dialogue about whether Jesus of Nazareth is ‘the Son of God, the Logos’, who is expected by Israel—according to the promises made to his own people—and, unknowingly, by all of humanity. Resuming this dialogue is the task that the present time sets before us” (Benedict 2018a).

Precisely because this exchange might, at first glance, appear as a good example of “dialogical tolerance” between Christianity and Judaism, it indicates its very limit. Indeed, a closer look reveals a hidden or tacit disagreement of whether a dialogue on “theological points” can and should take place was not resolved and thus remained the subject of potential conflicts. This disagreement was not addressed by the dialogue partners, and it therefore remains open to what extent they were aware of this. The question arises, however, whether this disagreement could have been resolved through dialogue. If there is no consensus on the question of the content and modality of an interreligious dialogue, indeed if even the concept of logos, which is presupposed in the dialogue, is disputed,1 how then can an interreligious dialogue help us resolve this fundamental disagreement? If such deep dissent underlies the dialogue and if, more generally speaking, conflicts can be understood as clearings, in which the absence of tacitly assumed commonalities becomes first and foremost apparent, then conflicts have a special heuristic significance and it seems advisable to focus attention on the disagreement.

3. Political Kippbild Hermeneutics

Kippbilder, a term rendered in English as ambiguous images, offer a good hermeneutic means to analyze a hidden disagreement like that between Benedict and Folger, one in which the root of the disagreement is difficult to see because both sides seem to share a common assumption (here: a dialogical approach), but for this very reason run the risk of overlooking an underlying disagreement (in this case: about the question of what can and cannot be the subject of a dialogue).2

It is through Kippbilder that the difference between “seeing” and “seeing as” becomes apparent (Wittgenstein 1984, 1953). Insofar as “seeing as” is related to “interpretation”,3 an intimate connection results between Kippbilder and hermeneutics. I have proposed to call it Kippbild hermeneutics.4 If limitations on the play of interpretations present excellent sites of potential conflict and politicization (Di Blasi 2021), then the basic limitation formed by aspect-blindness, or the inability to see different aspects, seems particularly pertinent to the nature of political conflicts (Wittgenstein 1953, p. 213). This also applies to political theological or political epistemological conflicts.

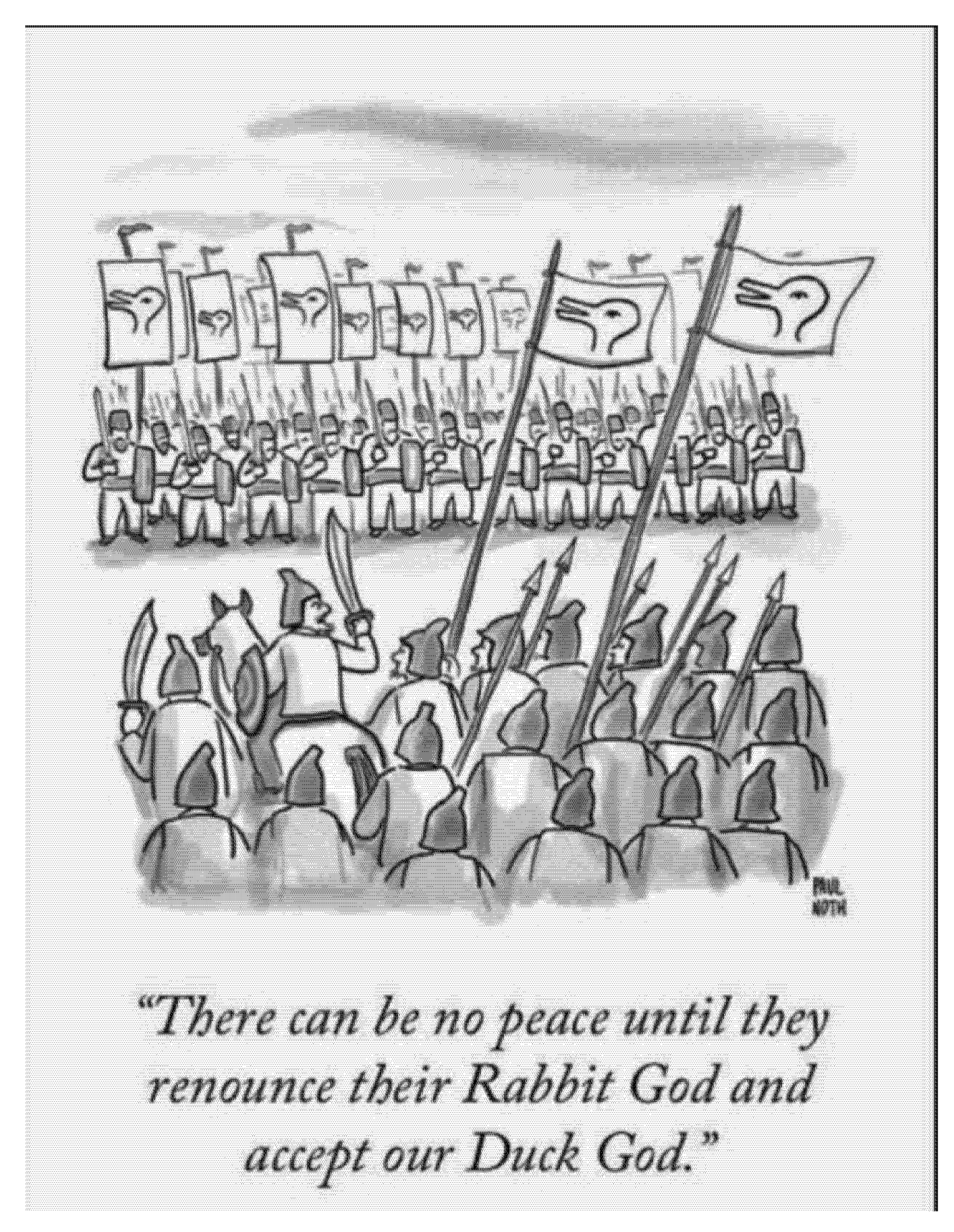

A well-known cartoon by Paul Noth published in the New Yorker in 2014 (Figure 1) is a case in point:

Figure 1.

Paul Noth, “There can be no peace until they renounce their Rabbit God and accept our Duck God”. The New Yorker, 1 December 2014, p. 78.

Here, [Figure 1] the ambiguous image serves to represent a political-theological conflict between two disputants as an epistemological political one. The connection made to the field of religion is striking; one is tempted to think of medieval crusaders and Islamic holy warriors, and to see them each as representatives of the current conflicts between Christian and Islamic “fundamentalists”. Both sides seem to conflict with each other because they do not see what the observer can see, because they each see only one aspect, one viewpoint. Because they do not see what the observer can see, they overestimate the difference and thereby idolize a one-sidedness which turns them into the intolerant God-warriors of their absolutized aspect. The picture thus seems to belong to a long Enlightenment tradition in which “religious” is quickly equated with “dogmatic” and “fanatical”.

According to Jacques Rancière, disagreement “is not the conflict between one who says white and another who says black. It is the conflict between one who says white and another who also says white but does not understand the same thing by it”. (Rancière 1999, p. x) While there are significant differences, there is at least one similarity to the cartoon: Both parties to the dispute say “duck-rabbit” (Wittgenstein 1953, p. 194), have written this on their banner, but they seem to understand something quite different by it. If we look at the problem from the point of view of a Kippbild hermeneutics, does it not consist exactly in the fact that, as Wittgenstein would say, two diametrically opposed forms of “aspect blindness” collide with each other here, whereby one side cannot see the picture-object “rabbit”, the other the picture-object “duck”?

Paul Noth also seems to suggest a solution to the conflict by citing in the cartoon the duck-rabbit from Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations (Wittgenstein 1953) and thus drawing our attention to this text. It was the aspect change contained in ambiguous images that served the Viennese philosopher to distinguish “seeing” from “seeing as”. As he put it (Wittgenstein 1953, pp. 194–95):

“I may, then, have seen the duck-rabbit simply as a picture-rabbit from the first. That is to say, if asked ‘What’s that?’ or ‘What do you see here?’ I should have replied: ‘A picture-rabbit.’ If I had further been asked what that was, I should have explained by pointing to all sorts of pictures of rabbits, should perhaps have pointed to real rabbits, talked about their habits, or given an imitation of them. I should not have answered the question ‘What do you see here?’ by saying: ‘Now I am seeing it as a picture-rabbit.’ […] Nevertheless someone else could have said of me: ‘He is seeing the figure as a picture-rabbit.’”

Yet “seeing” also sees only one aspect, but because this seeing is continuous, it cannot see that a second-order observer, who seems to correspond to the viewer of the cartoon, can recognize this seeing as “seeing as”. That our “seeing” was a “seeing as” can become recognizable to ourselves exactly when a new aspect appears in an ambiguous image (Wittgenstein 1953, p. 194). And because a subjective experience appears in this sudden illumination, an experience that is not thematized in any continuous “seeing”, a subjective dimension becomes recognizable in “seeing as”, the inseparable relation between subject and object, cognition and perception. Precisely this can loosen a strict and naive identification of a “fundamentalist” or “dogmatic” seeing with “objective perception”, without the two being able to be separated from one another. Entanglement is just the condition of possibility of recognizing a change of aspect at all as such: “The expression of a change of aspect is the expression of a new perception and at the same time of the perception’s being unchanged” (Wittgenstein 1953).

Accordingly, a political Kippbild hermeneutics would conceptualize the conflict between the disputants in Paul Noth’s cartoon as being about two instances of aspect blindness, as a consequence of two limitations. It would try to show to each of the parties their inability to recognize their “seeing as” as such and thereby attempt to relativize it; it would try to demonstrate their failure to recognize that what they dogmatically misunderstand as seeing an objective fact actually involves thought and interpretation, inseparably but distinguishably. On the other hand, as soon as relativization is achieved, the way to an affirmation of diversity is opened in which the other’s “seeing as” is recognized as not threatening one’s own “seeing as”, but instead as enriching it.

This indicates a possible solution to the conflict. Neither of the two parties to the dispute is right, nor is a possible third party. The solution might rather lie in the fact that the disputing parties change aspects and thereby realize that they confused and absolutized their respective relative “seeing as” with an objective perception. The solution here seems to be the relativization of the respective aspects, just as Bohr (1928), in a famous lecture from 1927 (published a year later), tried to settle wave-particle dualism through the principle of complementarity.

But is this a satisfactory answer in relation to the cartoon? A problem to this solution consists in the fact that something which takes place involuntarily is the precondition for the solution. An arbitrary aspect change is required of the very people for whom it is said not to have even occurred involuntarily. But is not the involuntary aspect change just the precondition for the fact that this change can sometimes occur arbitrarily? And would not the disputants, especially if they were aspect-blind, then have to rely on a belief? Would not they simply have to believe the Kippbild hermeneutician blindly, because without their own sight, who can assure them that they can see only one aspect at a time? And would not they then have to learn to distrust their own clear and distinct seeing at the same time? Would not they have to replace their knowledge based on the visual appearance with a belief, i.e., become the very blind believers that they were hastily said to be by the observer, in order thus to be able to gain more complex “knowledge”?

But if we take a closer look, we see that the basis of this interpretation is wrong. The issue here is not the clash between two sides each with aspect blindness, between two sorts of aspect blindness. For the cartoon, whether or not the author intended it, obviously goes beyond such a self-satisfied relativism or pluralism. If there were indeed two forms of complementary aspect blindness here, how could the armies recognize that the others were fighting under the banner of another god? Would they not necessarily recognize their own god in the banners of the others and thus be unable to recognize the others as enemies?

Indeed, as the viewer of the cartoon, (at least) the general of the army in the foreground knows very well that the others worship another god under the same banner and see the duck-rabbit as something different. He is therefore by no means more stupid in this than the aspect-seeing cartoon viewer. The obvious aggressiveness is expressed from exactly one who is without doubt capable of aspect change! Would aspect blindness, in turn, not prevent conflict from breaking out? And does the real problem lie not in aspect blindness, but rather in the assumption that one’s own way of seeing is correct and the other’s way is wrong? And does this not even include the assumption that the other is aspect blind and that one is therefore superior in being able to see (both) aspects? Is the apparent solution not the real problem, then, and how might this problem be solved?

Against this background the use of Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit in the cartoon appears even more ambiguous. It is more than a simple reference to Wittgenstein and more than a kind of paragon, a competition between cartoon and philosophy.5 It can also be read in such a way that the insight into the aspectuality of one’s own seeing does not protect one from being perceived as hostile by the other side or from seeing this other side itself as hostile. Even when one holds up Wittgenstein’s flag, as postmodernists do, one is not immune from getting into intractable political conflicts with another—and the growing identity-political polarizations within Western societies seem to confirm this. So, does the problem ultimately lie with Wittgenstein?

4. Political-Existentialist and Reductive Kippbild Hermeneutics

In his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein illustrates the difference between reporting and expressing an experience, that is, between a report (I see) of a rabbit and a (thought) expression, “A rabbit!” In so doing, he symbolically leaves the image-hermeneutics of the picture-rabbit in the ambiguous image and goes out into nature, so to speak: “I see a landscape; suddenly a rabbit runs past. I exclaim ‘A rabbit!’” (Wittgenstein 1953, p. 197). As in the work of Dilthey and Heidegger, here too, hermeneutics in a sense leaves the framework of texts and books and extends into the realm of life.6

Wittgenstein’s use of the term expression “experience” (Erlebnis) already suggests a connection to life (Leben). Indeed, this exclaiming of the experience of “A rabbit!” is not only embedded in another situation (“landscape”), but—just as the apparent movement of the aspect change had aroused Necker’s attention—can be traced back to the fact that here a movement in space had attracted one’s attention in involuntary fashion. This, again, can be traced back to the fact that something moving can be vital, just like a sudden noise in our vicinity, which exactly for this reason involuntarily attracts our tense attention. Depending on the context, the exclamation “a rabbit!” may thus also express relief (ah, it’s only a rabbit, not a snake or some other dangerous creature), or the hunter’s joy at finally having the rabbit in front of the shotgun.

Behind the experiential appearing of a new aspect, an underlying instinct, that is an existential or vital dimension, can be seen. A related possibility can be delineated. It consists of the fact that the appearance of an aspect can immediately interrupt the game of interpretations. A spot on a CT scan can mean an infinite number of things, but as soon as it might also mean “malignant tumor”, the free play of interpretations, of possibilities of seeing something as something (already set in motion by the possibility of danger anyway), abruptly changes its character. Here, one aspect takes the upper hand, interrupting the “free play”. This is not because the other possibilities no longer exist or because one suddenly becomes aspect-blind, but because one kind of “seeing as” gains so much more existential weight than all others, which thus fade away, so to speak, as the perception narrows down and fixes itself on the possibility that seems most dangerous and therefore pertinent.

It goes without saying that many apolitical conflicts are rooted in such an occurrence: for one person, a given sign may not mean anything special at all, where for another it is associated with threat and fear. Even if both sides recognize and acknowledge that both possibilities are forms of “seeing as”, both of which can be justified (e.g., that the rise of temperatures can, but does not have to, indicate an imminent irreversible heating of the planet), does not mean that for those who are alarmed by this possibility, the reference to the other possibility must lead to a relativization of their own “seeing as”.

Another example: the swastika can be seen either as an ancient religious symbol, as a symbol of luck in Hinduism, Jainism, or Buddhism. Or it can be seen as marking the NSDAP and the flag of the Third Reich. But even if one knows both, this does not mean that the reference to these different possibilities is apt to defuse the threatening and therefore politicizing force that emanates from this sign for many.

Here we seem somewhat imperceptibly to have moved away from the ambiguous image in the narrower sense. This is because the differing interpretations of the swastika do not seem to go hand in hand with different forms of “seeing as”. The “swastika” design itself does not look any different if I interpret it in this way or in that. But this is not necessarily so. In Ludwig Wittgenstein no less, a kind of swastika ambiguous image appears already in 1930, and it does so precisely in a passage in which he introduces “seeing as” in a terminological way for the first time (Wittgenstein 1984, p. 253).

“Rather, this seeing it as a face must be compared […] with the seeingthis ‘as a square with diagonals’ or ‘as a swastika’, that is, as limiting case of this drawing:

[…] The case of ‘seeing

as a swastika’ is of special interest because this expression might mean being, somehow, under the optical delusion that the square is not quite closed, that there are the gaps which distinguish the swastika from our drawing”.

Wittgenstein thus presents us with a figure in which against neutral possibilities of “seeing as” (a two-dimensional square with diagonals, a pyramid from above, a stylized hourglass, etc.), another possibility is distinguished through minimal reductions/alterations to the corners of the figure. More than the others, this possible aspect evokes an experiential appearing, precisely because it refers to a sign that, back in 1930, was just beginning to become politically explosive. At the same time, this “seeing as” is described as deficient, is compared to an “optical delusion”, and considered an incomplete seeing (gaps). With this, however, a political subdimension seems to be inscribed in the distinction between “seeing” and “seeing as” from the very beginning, and a Kippbild hermeneutics based on it would thus be a political one from the very beginning!

This interpretation may seem a bit hasty insofar as the context does not readily suggest a political reading. But this changes when we look at the first part of the Philosophical Investigations, written between 1936 and 1946.

Here, too, a very similar example appears, one in which the political aspect can hardly be overlooked (Wittgenstein 1953, p. 126):

”But can’t I imagine that the people around me are automata, lack consciousness, even though they behave in the same way as usual?—If I imagine it now—alone in my room—I see people with fixed looks (as in a trance) going about their business—the idea is perhaps a little uncanny. But just try to keep hold of this idea in the midst of your ordinary intercourse with others, in the street, say! Say to yourself, for example: ‘The children over there are mere automata; all their liveliness is mere automatism.’ And you will either find these words becoming quite meaningless; or you will produce in yourself some kind of uncanny feeling, or something of the sort. Seeing a living human being as an automaton is analogous to seeing one figure as a limiting case or variant of another; the cross-pieces of a window as a swastika, for example”.

In this case, “seeing as” must also be supplemented by a specific reduction, for one must actively be prevented from seeing something in order to be able to see the window cross as a swastika. Rupert Read has derived a possibility of political interpretation from this (Read 2010, p. 606):

“Seeing a living human being as an automaton is not simply an error, not simply an upshot of stupidity or cant; nor is it quite a complete and utter existential impossibility, an idle fantasy. It is something that one can lead oneself toward doing. For instance, by bracketing oneself, placing oneself in a position of complete spectatoriality to the reality of others (as philosophers do when they are attempting to consider skepticism about other minds as a live possibility). One might say: the Nazi placed himself as a spectator to the cries of his victims. He didn’t truly hear them as cries. He didn’t hear them as containing a call to respond to, as manifesting a shared humanity”.

Somewhat later, Read emphasizes that “to be able to see one’s victims as automata, it helps to see as an automaton sees” (Read 2010). And may we assume that Wittgenstein experiences his own observing as uncanny, exactly because this observing comes so close to this specific reduction? In the observation of this “reductive Kippbild hermeneutics”, as I propose to call it, a double aspect change takes place, similarly to the case of a Rubin vase (Di Blasi 2018, pp. 42–47): Not only are people reduced to automata by other people and thus dehumanized but, as Wittgenstein clearly emphasizes here, there is the uncanny fact that this dehumanization includes those who see other people as automata. More accurately, it is by seeing other people as automata that I transform myself into an automaton (at least in relation to them). The reduction thus concerns people as they appear to those who view them as automata, as well as those who dehumanize them and who thereby become automata themselves, just as windows become swastikas.

Such a double “aspect change”, which is inherent to a reductive Kippbild hermeneutics, might be called a negative aha-moment. While in the field of ambiguous images, the (positive) aha-moment indicates the appearance of a new aspect (oh, now, I see the duck as rabbit!), I would suggest calling negative aha-moment the disappearance of an (alleged) difference, or more precisely: the uncanny encounter with the devalued Other as one’s own double, the discovery of an Oedipus-like “terrible truth”.

A negative aha-moment in which we can recognize that our ability to see both aspects does not put us in a superior position. Conversely, the assumption of superiority is precisely the moment when we deny something to others, reduce them, and in a sense dehumanize them (“aspect-blind foundationalists”, “automatons”, “Nazis”, etc.). It is as if the smiling observer of Paul Noth’s cartoon, who had been enjoying his supposed superiority over the limited and stubborn religious or political idiot, not only suddenly finds himself in the middle of the battlefield, but must recognize his similarity to the others in the drawing, precisely because he has portrayed these others as he has.

Resulting from the negative aha-moment, this insight goes beyond Bohr’s principle of complementarity, where already the independence of the observer’s position with respect to the phenomena is questioned, and even beyond the recognition of one’s own “eccentric positionality” (Plessner 1975, p. 292).7 Following Wittgenstein, it can be recognized how an observer, qua reductive Kippbild hermeneutics, proves that she is exactly what she thought she had observed in others. She thus comes to recognize herself exactly as that Other at whom she had just smiled in a superior and mocking fashion, that is, as the other’s double.8 This is what makes this insight uncanny. It is in this negative aha-moment, this moment of uncanny self-insight, that the radically (self-)enlightening potential of a political Kippbild hermeneutics could lie.

Let us bring the different threads together. Tolerance is an ambivalent term; it includes a dimension of power and hierarchy (Brown and Forst 2014). Tolerating means, as Wendy Brown puts it, “regulating aversion”, and ”in this activity of management, tolerance does not offer resolution or transcendence, but only a strategy for coping”. (Brown 2006, p. 25).

Tolerance involves, as already Goethe famously said, an insult, an incomplete recognition of the Other (Goethe 1998, p. 116). Mendes-Flohr’s notion of dialogic tolerance is based on a fundamental recognition of the difference of the Other. Following a radical concept of dialogue inspired by Buber, it succeeds in remedying a basic problem of the concept of tolerance.

However, this concept of dialogue, especially regarding inter-religious and inter-epistemic relations, seems to presuppose too much: a shared understanding of what an interreligious dialogue should and should not be about. But as the Christian-Jewish dialogue in general, and, most recently, the dialogue between Benedict XVI and Rabbi Folger demonstrated, this is not self-evident.

A political Kippbild hermeneutics inspired by Wittgenstein with the notion of a negative aha-moment at its core does not assume a shared commonality, but rather unmasks a problematic complicity. It shows how close we ourselves are to those negative images we make of other groups. It thereby offers the possibility of becoming aware of (and deconstructing) implicit assumptions of superiority over others (e.g., epistemic approaches or religious traditions), assumptions that are inherent to the concept of tolerance as well. The negative aha-moment addresses this problem not through dialogue or a face-to-face encounter, as Mendes-Flohr does. Instead, it tries to solve the problem through challenging (implicit) claims of an alleged epistemic superiority of one’s own position. Hence, Kippbild hermeneutics offers a counter design to what has been called “epistocracy” (Brennan 2016, p. 14) or epistemic paternalism.

While Kippbilder do not represent an encounter with the Other, they nevertheless include in a sense a “responsive” dimension. Neither the aha-moment (when a new aspect suddenly appears) nor the negative aha-moment (when a difference between me and the image of the Other disappears) can be generated intentionally without further ado. They happen to one, and the reaction to it can be understood as a response to this experience. In place of an encounter with the Other, the negative aha-moment provides a model for an encounter with the limitations of the image we have made of the Other. Kippbild hermeneutics does not replace dialogue. But it makes us aware of our possible epistemological assumptions of superiority and of the possibility that those pejorative images we make of others may say more about us than about the Other. In this way, by deconstructing an obstacle, it can indirectly contribute to such an encounter and thus also to a productive dialogue.

But does Kippbild hermeneutics also help in the face of escalating conflicts like the current one in Ukraine? Does epistemic modesty not ultimately support the aggressor? Given that a middle between two contradictory opposites is excluded, we must accept that in case of specific conflicts, political Kippbild hermeneutics (as well as dialogue, tolerance, and pacifism) are reaching their limits. Nevertheless, in political conflicts we rarely must deal with a mere juxtaposition of contradictory opposites; whereas war can bring such contrasts clearly to light, part of the” fog of war” (Carl von Clausewitz) is perhaps the fact that in the course of such conflicts, the parties tend too easily to see each other as representatives of such principles and to fail to recognize that the principled opposites are not so clearly distributed. On the contrary, the same conflict that brings contradictions to light also leads usually to an alignment of the two parties and the opposites become confused. Karl Barth paid attention to both dimensions when in a situation which was not very different from the current one in the Ukraine, he wrote: “Dieses System [the German Nazism] kann die Kirche—es kann aber auch die Kirche dieses System nur verneinen. […] Es wäre aber gut, wenn Sie sich als Christen und Theologen nun auch dafür interessierten, daß Europa, indem es vor der Diktatur des Mythus Schritt für Schritt zurückweicht, indem es sich ihren Methoden beugt und sie sich zu eigen macht, im Begriff steht, zum Irrenhaus zu werden.” (Barth 2001, pp. 162–63.)

Kippbild hermeneutics does not offer a sufficient answer to the emergence of fundamental contradictions but at least it might help to counter the danger that, as happens in such conflicts, the two conflict partners align themselves with each other. Especially in conflict situations in which the image of the Other is easily distorted into a caricature, political Kippbild hermeneutics can be a corrective since it can help to resist the temptation to identify the Other all to clearly with the opposing principle and thus counteract the inherent tendency of conflicts and of wars to escalate. And if the escalation in conflicts has to do with the fact that in conflicts, there is a tendency toward what René Girard called a “violent imitation, which makes adversaries more and more alike” (Girard 2010, p. 10), and, at the same time, a dwindling willingness and/or ability to recognize or acknowledge this increasing similarity, the negative aha-moment might be an effective antidote to such escalation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1. | It is safe to say that for Pope Benedict, the notion of logos was crucial for his struggle against a contemporary relativism. Shortly after he became Pope, he held his famous “Regensburg Lecture,” which he based on the assumption that God and the logos were not completely separated, and that faith and reason belonged together. Religions, being oriented toward God, should thus be able, and prepared, to struggle for truth, instead of constituting enclosed or autonomous realms of relative truths. This close relationship between God and (Greek) logos, however, was undoubtedly formative for the mainstream of Orthodox and Catholic Christianity, but not for other relevant traditions inside Christianity (Nominalism, Voluntarism, significant currents within Protestantism) nor outside it, such as Islam or Judaism. It was certainly no coincidence that an excellent representative of a (Jewish) “Hellenization” of the Biblical tradition, who very early on related God and the logos, namely Philo, became relevant for the Christian tradition, but was ignored by (Rabbinic) Judaism. |

| 2. | This section is largely based on my text “Politische Kippbildhermeneutik” (Di Blasi 2021). |

| 3. | As Heidegger puts it: “The ‘as’ constitutes the structure of the explicitness of what is understood; it constitutes the interpretation.” (Heidegger 2010, p. 144). |

| 4. | On the term Kippbild hermeneutics, see also (Di Blasi 2018, esp. chp. 1). |

| 5. | Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit comes from a caricature published in the magazine Fliegende Blätter in 1892. See Fliegende Blätter. 1892. Available online: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/fb97/0147; (accessed on 31 December 2021). Therefore, we are dealing here with a reappropriation of a caricature previously hijacked by the philosopher into a new caricature. |

| 6. | Interestingly, this movement is the exact opposite one to that of the natural scientist Louis Albert Necker, who is often regarded as the scientific “discoverer” of the ambiguous image and began his famous text on Kippbilder with observations about natural phenomena in Switzerland and–via the figure of the crystal—arrived at the geometric figure of the “Necker cube” or glass cube (see Necker 1832). Wittgenstein starts chapter XI of his Philosophical Investigations with the glass cube, proceeds from there to the duck-rabbit, and finally goes from there to the rabbit in the landscape. |

| 7. | In this context, the extent to which Plessner uses Kippbild-hermeneutic terminology to describe the eccentricity characteristic of man is striking. |

| 8. | Politics, it might be claimed, is a machine that always invents new ways to see other groups reductively, and in so doing to reduce one’s own group as the other face of the others that one has reduced. It is a provider of possibilities to outsource our collective self-contradictions; it constructs a connection through which we can regress, through which we can abandon ourselves to the death drive. In this sense, negative aha-moments, as moments of Tat Tvam Asi, stand at the border of the political: they are clearings that give insight in the conflictual political machine and thereby immediately open new possibilities to politicize these insights—for example against “politics”. |

References

- Barth, Karl. 2001. An die Studenten der reformierten Theologie in Budapest, 1938. In Offene Briefe 1935–1942. Gesamtausgabe Volume 3 36/Abt. V. Zurich: Theologischer Verlag, pp. 156–65. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI. 2018a. Not Mission, but Dialogue. Translated by CCJR. Available online: https://www.ccjr.us/dialogika-resources/themes-in-today-s-dialogue/emeritus-pope/not-mission-but-dialogue (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Benedict XVI. 2018b. Reply to Rabbi Arie Folger. Translated by CCJR. August 23, Available online: https://www.ccjr.us/dialogika-resources/themes-in-today-s-dialogue/emeritus-pope/benedict-2018aug28 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Bohr, Niels. 1928. The Quantum Postulate and the Recent Development of Atomic Theory. Nature 121: 580–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brennan, Jason. 2016. Against Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Wendy. 2006. Regulating Aversion. Tolerance in the Age of Identity and Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Wendy, and Rainer Forst. 2014. The Power of Tolerance. A Debate. Edited by Luca Di Blasi and Christoph F. E. Holzhey. Vienna and Berlin: Turia + Kant. [Google Scholar]

- Di Blasi, Luca. 2018. Dezentrierungen: Beiträge zur Philosophie der Religion im 20. Jahrhundert. Vienna and Berlin: Turia + Kant. [Google Scholar]

- Di Blasi, Luca. 2020. Resuming Conflict: Benedict’s ‘Grace and Vocation’ and the Limit of Dialogue. The Philosophical Journal of Conflict and Violence 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Di Blasi, Luca. 2021. Politische Kippbildhermeneutik. Hermeneutische Blätter 27: 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folger, Arie. 2018. Reply to Emeritus Pope Benedict. Translated by CCJR. September 4, Available online: https://www.ccjr.us/dialogika-resources/themes-in-today-s-dialogue/emeritus-pope/folger-2018sept4 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Girard, René. 2010. Battling to the End. Conversations with Benoît Chantre. Translated by Mary Baker. East Lansing: Michigang State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. 1998. Maxims and Reflections. Translated by Elisabeth Stopp. Edited by Peter Hutchinson. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2010. Being and Time. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. 1996. An Answer to the Question: What Is Enlightenment? In Kant, Practical Philosophy. Translated and Edited by Mary Gregor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Flohr, Paul. 2017. Dialogue and the Crafting of a Multi-Cutural Society. In Responsibility and the Enhancement of Life. Essays in Honor of William Schweiker. Edited by Günter Thomas and Heike Springhart. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, pp. 309–17. [Google Scholar]

- Necker, Louis Albert. 1832. LXI. Observations on some remarkable optical phænomena seen in Switzerland; and on an optical phænomenon which occurs on viewing a figure of a crystal or geometrical solid. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 1: 329–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plessner, Helmuth. 1975. Die Stufen des Organischen und der Mensch. Einleitung in die philosophische Anthropologie. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, Jacques. 1999. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Read, Rupert. 2010. Wittgenstein’s ‘Philosophical Investigations’ as a War Book. New Literary History 41: 593–612. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophische Untersuchungen/Philosophical Investigations. English and German. Translated by Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1984. Das Blaue Buch. Eine philosophische Betrachtung (Das Braune Buch). Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).