1. Introduction

Since 11 March 2020, when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the highest risk level for infectious diseases (

World Health Organization 2020), the world has been affected across all aspects of politics, the economy, society, culture, and religion. There is a popular debate over whether the division of the times should be newly divided into pre-COVID-19 (B.C.) and post-COVID-19 (A.C.) (

Friedman 2020), as mankind is experiencing a new way of life for national and individual preventive measures in an era that has not been seen before. In particular, and without exception, religious organizations, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, and temples that gather worshippers for prayers, religious gatherings, or events, have also been affected in the post-COVID-19 era. The growth of Christianity in Korea has been growing through group-oriented activities based on relationships. However, religious activities, including regular worship services, social activities, and volunteer work are facing a serious crisis following the government’s policies of “high-intensity social distancing” and “administrative order to restrict gatherings.” Moreover, while church members continued to maintain worship and sociality to maintain existing religious principles, the church has often been pointed out as a source of mass infection of COVID-19. These events suggest that a new approach is needed to promote the spirituality of church members, along with a reevaluation of existing religious values and principles.

1.1. Spirituality and Religion

Spirituality is not an abstract concept that only religious people have, rather it is developing as a concrete concept that directly interacts with human health (

Lucchetti et al. 2012;

Meador and Koenig 2000). The WHO includes spiritual well-being under the definition of human well-being (

K.-H. Kim 2013). Walker and Hill-Polucky proposed a health-promoting lifestyle and included nutrition and physical activity as well as mental growth as important sub-factors (

Walker and Hill-Polerecky 1996). Recently, even in various academic fields such as medicine and psychology, research is recognizing the importance of spirituality in the treatment of patients, and personal growth is on the rise (

K.-A. Kang et al. 2021;

Yoon et al. 2021;

Yong et al. 2011). In particular, it has been reported that more than 90% of the world’s population is involved in various forms of religious or spiritual practices (

Koenig 2009), which confirms that spirituality is an inseparable, major factor in human life. Despite this importance, research on human spirituality is developing very slowly in comparison to studies on psychological factors such as emotions. Moreover, the spiritual crisis caused by the restriction of religious activities in the reality of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic is gradually increasing the need for more research on spiritual health.

Spirituality is the relationship between a transcendent being and an individual or group that is seeking to find transcendental meaning (

Kim and Moon 2021). Spirituality is expressed through various methods, including nature, music, and artistic activities, but most people express their spirituality through religious activities. This is closely related to the relationship presented in the definition of spirituality mentioned above. For example, according to a survey related to religious beliefs and behaviors, about 83.7% of the world’s population follows a specific type of religion and is consistently engaged in certain religious activities like worship (

PEW Research Center 2012). In addition, a reinvestigation conducted five years later predicts that the proportion of religious people worldwide will continue to increase (

PEW Research Center 2017).

This can be interpreted as an indicator of the relational characteristics of spirituality. The biblical teaching that worship is used as a meeting place and for sociality, at the heart of the Christian community, is in line with this claim (

Kwon 2010). In other words, worship can be understood as a relational concept in which both vertical communion with God and horizontal encounters with church members occur (

Foster 1978).

1.2. Spirituality and Interpersonal Trust

In Christianity, absolute faith and trust in God are the most important factors within the church as a concept identified with the Christian faith itself (

C.-S. Kim 2012). This is the act of being a Christian (Acts 20:21), and it means being a Christian (1 Corinthians 2:5). Although this personal level of faith is the key to salvation according to Christianity, the Bible offers another principle. It is a union of interpersonal relationships based on the relationship with God (

K. Lee 2021). Christian spirituality can be said to be at the level of “individual” and also at the level of “community” because it has the key characteristic that a relationship with God must be connected to the formation of a relationship with other people. The etymology of the word “church” is ecclesia (ἐκκλησία), meaning “those who are called out” (

Berkhof 2017). Considering the original meaning of “church,” it is impossible to think of ruling out interpersonal relationships, and it is necessary to realize that the purpose of the Christian community is not focused on the singular concept of a single member, but rather on the plural concept of members. In other words, it emphasizes the importance of forming a horizontal relationship between people as much as a relationship of trust in spiritual development (

Habermas and Issler 1992). Just as the relationship with God is an important part of spirituality, it suggests that the relationship with people is an important part of the composition of the church. The first step in the development of spirituality begins with the vertical relationship with God and is accomplished through the horizontal relationship with others (

Forde et al. 1989), through which true humanity can be completed.

Christians experience God through personal prayer and meditation on the Word of God and experience God through the image of other good Christians. The mystery of the Trinity in the Christian faith is based on the relational property that different persons can coexist for a long time through the perfect and absolute love that existed within God (

M. K. Lee 2003). This means that the different Persons lived for completely different Ones and through their relationship they became a perfect one, showing the essence of the most perfect interpersonal relationship that coexisted. Through this, just as the Holy Trinity was united with each other in a relationship of love, it was planned that human beings would have the opportunity to live for others in this relationship. Therefore, true Christian faith must be realized through relationships, and growth as a true Christian, that is, spiritual maturity is possible based on these relational attributes. Spirituality in this contextual dimension begins with a personal relationship with God, and it should be an experience that can be felt, rather than as a simple abstract concept. Therefore, considering this concept of Christian spirituality, it is reasonable to measure spirituality in this study with The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) (

Underwood and Teresi 2002), which is considered to measure the degree to which we feel and experience God’s presence every day.

1.3. Trust and Spiritual Experience in the Church

Trust within an organization is a key factor necessary for forming, maintaining, and developing the organization (

Lee and Han 2004). This is a major variable that enables members to promote commitment within the organization, facilitates positive interactions among members, and functions as an adhesive to unite the organization (

Shaw 1997). In addition, it is a key element for successfully performing tasks within an organization based on mutual dependence among members, and is an essential factor for minimizing conflicts within an organization (

De Dreu 2010). In fact, in a previous study conducted on church organizations, it was found that interpersonal trust in the church partially mediates when the devotion of church members is lowered due to the experience of conflict in the church (

Jeong and Lee 2020). This shows that, as in general social organizations such as corporations, interpersonal trust within the church is an important factor in organizational management. Therefore, being spiritually trustworthy within the church is an important model for promoting individual spirituality.

K. Lee (

2021) suggested the characteristics of three sub-factor dimensions, by studying the characteristics of church members trusted by church members. Characteristic-based trust means trust based on the psychological and external characteristics of a trust object. Interaction-based trust is the trust that is formed based on the process of interaction between the trusting subject and the object and includes the experience that the trusting subject directly encounters through the trustworthy object. Institution-based trust is based on the trust object’s observance of social and church norms, and it shows that both God’s law and human law are properly observed. When interpersonal relationships based on trust are established in the church, it becomes an important foundation for maintaining personal spirituality. Therefore, trust within the church should reflect the relationship with God, not the interpersonal relationship formed through general communication. This can be seen as a paradigm that can sustain relationships based on trust even if the frequency of face-to-face worship decreases due to COVID-19. Church members must have the experience of meeting God indirectly through interpersonal relationships within the church, which can lead to the enhancement of the spiritual experience of meeting God every day.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the personal and religious characteristics and interpersonal trust variables in the church that explain the daily spiritual experiences of church members. This study was significant in identifying important personal and relational factors in the life of faith and identifying factors necessary for church growth and the spiritual growth of members.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study was conducted to analyze the influence of personal and religious environment and interpersonal trust on the spiritual experience of Christians by using a data mining method for decision tree analysis. Data from the doctoral dissertation of

K. Lee (

2021) was used as the primary data for this study. It is difficult to assume normality as an individual’s demographic characteristics or measurement of religious activities, such as prayer and Word meditation, consisting of a nominal scale. In addition, in the case of regression analysis, if there are many predictor variables, it would be difficult to avoid mutual interference. Therefore, this study used the decision tree analysis method, one of the data mining techniques. Decision tree analysis is a non-parametric statistical analysis method that does not require the assumption of normality and is suitable for analyzing a model with a large number of predictors. Therefore, in this study, several personal and religious characteristics and church interpersonal trust were set as predictors, and meaningful explanatory variables were explored with spiritual experience as the target variable.

2.2. Study Participants and Data Collection

Primary data were collected through an online survey conducted between 22 March and 4 April 2021 which targeted adult Christian men and women (regardless of their denomination) in their 20s and older from across Korea. Of the data collected from 626 people, responses from non-Christians or unfaithful responses were excluded, and responses from 600 participants were used for secondary data analysis. The questionnaire was produced using Google Forms, and the questionnaire was designed so that only those who read the researcher’s explanation and agreed to voluntary participation would start. The link to the online questionnaire was posted to the pastor’s community or sent individually to the elders and the pastor in charge to ask for help for the church members to respond to the survey.

Among study participants, 276 (46.0%) were men and 324 (54.0%) were women. By age, those in their 40s accounted for 174 participants (29.0%), followed by 128 (21.3%) in their 60s, and 111 (18.5%) in their 50s and under 30. With respect to the position of church duties, there were 131 elders (21.8%) including senior deaconesses, 294 deacons (49.0%), and 175 laypersons (29.2%). Those with more than 41 years of faith accounted for the largest group with 202 participants (33.7%), followed by 144 (21.0%) with 21–30 years of faith. An overwhelming majority of 549 participants (91.5%) were leading a religious life with their families. As for the size of the church, 161 participants (26.8%) attend small churches of 51–100 members and 123 (20.5%) attend large churches with 301 or more members. There were also 126 participants (21.0%) who attend very small churches with less than 50 members. As a result of the survey on the number of weekly worship services attended, 241 participants (40.2%) attended twice a week, while 190 (31.7%) attended once a week. With regard to Bible reading, 218 participants (36.3%) consistently read the Bible more than five days a week and 386 participants (64.3%) prayed more than five days a week.

2.3. Tools

2.3.1. Spiritual Experience

For spiritual experience, the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) as validated by

Underwood and Teresi (

2002) was used. In the process of validating this scale in the Korean version, the construct validity was confirmed using factor analysis, and the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s α) was high at 0.92 (

Kim and Jeong 2015). Spiritual experience refers to an individual’s awareness of the transcendent God in daily life and the interaction or connection in life and consists of a total of 16 items. The scale is measured using a 6-point Likert scale (6 points = several times a day, 1 point = none). However, the last question (number 16) was rated on a 4-point Likert scale as in the original scale, which pertains to a question expressing the subjective sense of distance between oneself and God. It was interpreted that the higher the score, the greater the degree of connection with God, the more transcendent the individual was, and the higher the perception of daily spiritual experiences was. In this study, Cronbach’s α value was found to be 0.95.

2.3.2. Church Interpersonal Trust

The Church Interpersonal Trust (CIT) scale, developed and validated by

K. Lee (

2021) which considers the environment and characteristics of the church organization, was used to measure church interpersonal trust (

K. Lee 2021). Interpersonal trust is defined as a “psychological state where one wants to trust and cooperate with one another while taking risks,” where there is “will or confidence formed based on the characteristics of the trust object, emotion and evaluation formed through the interaction between the trust subject and the object, and the compliance with the system that defines the social action of the trust object” (

K. Lee 2021). The scale consists of 36 items and three sub-factors: characteristic-based trust, interaction-based trust, and institution-based trust. This scale is measured on a 5-point Likert scale, and a higher score is interpreted as having a higher level of interpersonal trust in the church. Cronbach’s α value in this study was 0.95.

2.3.3. Demographic and Religious Practice

Participants’ characteristics were divided into three areas based on previous studies (

K. Lee 2021). The demographic characteristics included gender and age, while the religious practices included church duties, periods of faith, religious affiliation with family members, church size, worship attendance frequency, prayer frequency, and Bible reading frequency. Interpersonal characteristics were measured using the CIT scale.

2.4. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Sahmyook University (IRB no. SYU 2022-02-013) on 4 March 2022.

2.5. Data Analysis

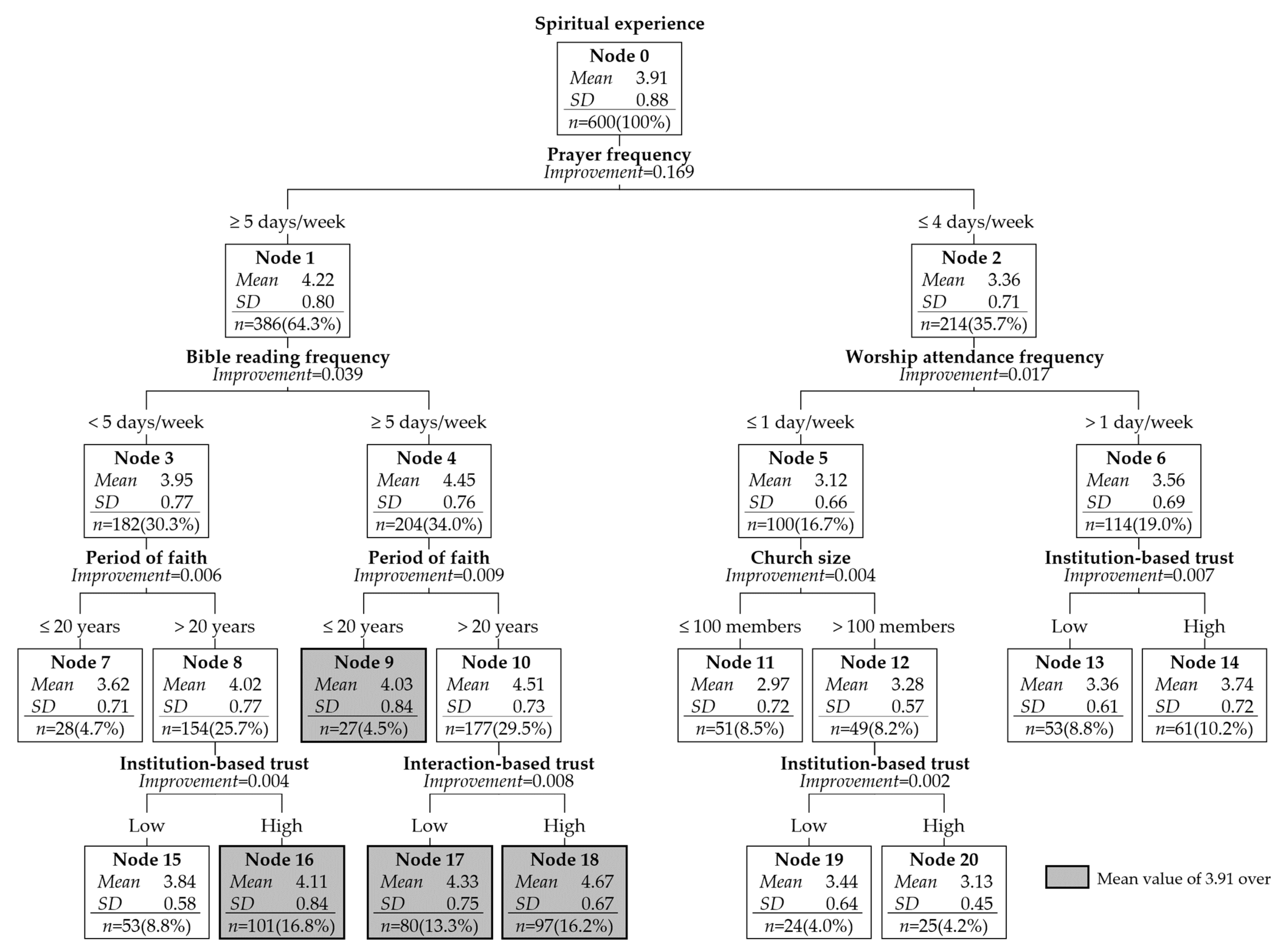

The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics program for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A frequency analysis was performed on the general and spiritual characteristics of participants. The reliability of the CIT scale was presented by calculating Cronbach’s α value. The difference in spiritual experience according to general characteristics was analyzed by variance analysis, and the post hoc test was analyzed using Scheffé’s method. Decision tree analysis was used to search for variables that explained spiritual experiences. As there were many categorical scales for study variables and ease of interpretation, the interpersonal trust scale was also divided into upper and lower groups centered on the mean and used for analysis. Decision tree analysis is a nonparametric statistical analysis method and has the advantage of being free from the assumption of normality. Statistical analysis of the data of this study was analyzed using decision tree analysis. CART (classification and regression tree) was used as the algorithm for decision tree analysis, and a regression tree was calculated and analyzed. Decision tree analysis has advantages in that it does not require the assumption of normality, confirms the interaction between variables, and makes it easy to interpret the results visually. A total of 12 predictors were inputted, with the target variable as spiritual experience. The model was segmented using a depth of four, a parent node with a minimum size of 30, and a child node with a minimum size of 20. To validate the decision tree analysis, we calculated the risk estimate and performed a k-fold evaluation (k = 10) for cross validation.

4. Discussion

Through this study, the influence of personal and religious characteristics and interpersonal trust in the church on the daily spiritual experience of Christians were explored and analyzed. The strongest predictor of improving daily spiritual experiences was personal prayer. It was reported that the spiritual experience of the group who consistently prayed for more than five days a week, except for routine prayers such as meal prayers, was very high (Node 1). The results of this study can be understood in the same context as the traditional Christian teaching that prayer is the main key, means, and function for the spiritual growth of Christians (

Cho 2017). Prayer is the best way to establish and maintain the vertical relationship with God beyond a simple religious act or a means of fulfilling the desires of the heart (

Forde et al. 1989). Furthermore, it seems that the individual’s spiritual experience is enhanced by understanding God’s will through prayer and experiencing the realization of that will through daily life. In particular, prayer is a variable frequently used recently along with spirituality in various academic fields such as medicine and psychology; thus, it is necessary to use it as a more practical tool in research in fields related to spirituality and mental health in the future (

Gross and Rutland 2021;

Naghi et al. 2012;

Selman et al. 2007).

For those who read the Bible more than five days a week in addition to practicing daily prayer, the average spiritual experience rose even higher (Node 4). The act of reading the Bible was used for spiritual training for different purposes in different times, but it was a key theme that did not change along with prayer in religious life (

Shin 2009). As the Christian scripture, the Bible fully reveals God and provides certain knowledge that leads to salvation. Therefore, the way to know God in a relationship with God is through the Bible, and only the act of reading the Bible is the surest way for a religious encounter and sociality with God (

McGrath 2012). True spiritual growth can be achieved when reading the Bible goes beyond simply knowing the knowledge and is connected to a series of processes of experiencing, analyzing, and interpreting the Word (

Fowler 1995); if the condition of prayer is added to this, a higher expected effect can be achieved. Early monks not only prayed but also read the Bible for several hours a day, known as “Lectio Divina.” “Lectio Divina” was the most important devotional method considered by early religious scholars; they were able to discover the subject of prayer while reading the Bible, and by praying they were able to find their own guidelines for living in harmony with God (

Yoo 1999). Although these research results were a topic that was mainly discussed and practiced in the field of theology, the functional relationship between the two factors was investigated by applying the social science research method. Through this, the practical basis for the biblical principle discussed thus far was provided and the possibility of a new application to this topic was suggested.

The longer the period of faith of those who prayed and read the Bible every day, the higher the spiritual experience was (Node 10), and it was found that even the group who rarely read the Bible had a higher spiritual experience when the period of faith was long (Node 8). These results explain the benefits of attending church over a long period. A long religious life has been shown to bring about continuous spiritual growth, even if there is a slight lack of exercise in religious activities. This suggests that it is necessary to continue to maintain relationships with the church even if daily religious practices are insufficient, and based on this, it is necessary to prepare specific application plans for the spiritual growth of members.

Long-term attendance members who practice daily prayer and Bible reading showed the highest spiritual experience score in this study when the interaction-based trust was high (Node 18). The proportion of this group with the highest average spiritual experience was 16.2%. Interaction-based trust shows characteristics that are formed based on trustworthiness identified through experience after experience is accumulated through interaction between trusting subjects and objects in the church (

K. Lee 2021). This has significant implications in that it proves the value of fellowship based on relationships with others in addition to prayer and the Word in personal spirituality. It is also meaningful in that it provides a scientific basis for the religious principles presented in the Bible. The Bible emphasizes that a vertical relationship with God is the basis of spiritual development and emphasizes the union of horizontal interpersonal relationships based on trust in God (

Sanders 2017;

Pink 2014). “As you are in me and I in you, so they may all be one in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me” (John 17:21). Through John 17:21 in the Bible, Jesus Christ emphasizes the love and unity that should consolidate the members of the saved community. Love and unity cannot exist without mutual trust, but love and unity can be achieved through trust at the level of interpersonal trust and faith. Therefore, church members can form interpersonal trust based on their faith in God. Unlike general social organizations, such as companies that share economic interests, the church can be viewed as a community that builds strong mutual trust even with the exclusion of private interests. This can be said to be an essential characteristic of a church organization that distinguishes it from other general social organizations.

Moreover, even in the group who did not read the Bible every day, it was found that personal spiritual experience increased when there was a trustworthy person (based on institution-based trust criteria) in the church who showed desirable characteristics of life by obeying social and church rules (Node 16). People with high institutional-based trust show the characteristics of thoroughly complying with social and church norms so that the appearance of the church and society is consistent (

K. Lee 2021), and the person they are inside is the same as the person seen on the outside. Through this, the standard for life as a desirable believer is set to become an example from which one can learn.

On the other hand, the group with the lowest spiritual experience appeared to attend small and medium-sized churches while praying and reading the Bible infrequently (Node 11). Compared to the group with the highest spiritual experience (Node 18), these were younger individuals, more likely to hold duty positions in the church, and were more likely to lead a religious life. These results suggest that special attention is needed for young people who do not have the religious support of their families and who lead a religious life alone. Considering that spiritual experience was lower in the case of attending small and medium-sized churches, it seems that this is because there is a limit to discovering and taking care of risk groups due to the limited manpower of small churches. Therefore, it is necessary to identify church members with these characteristics and educate them on the importance and method of prayer and Bible reading and pay attention to them so that they can continue to participate in worship. Moreover, it is necessary to provide practical help to meet their needs as well as emotional exchange for them to feel personal warmth. Through this, it is anticipated that it will be possible to promote spiritual health in the long term.

While the Christian’s spiritual experience means a relationship with the transcendent God, interpersonal trust means a relationship with others who have a relationship with God. The Christian worldview is the totality of these relations with God and interpersonal relationships, and can be understood in a larger context called “relationship.” In Christian belief, the attribute of God is the Trinity, which is based on the relational attribute in which three different Persons coexist in unity (

M. K. Lee 2003). Human beings are created according to these attributes of God, and through interpersonal relationships, humanity that follows the image of God is realized. In order to increase mutual trust through interpersonal relationships within the church, it is necessary to increase the emotional experience of feeling warmth and comfort in the process of interpersonal relationships rather than compliments based on personal reputation. Moreover, it should be able to help solve personal difficulties in practice. Specifically, emotional factors such as feeling comfortable when working together or providing sincere advice and comfort were very important parts in the characteristics of the interaction-based trust sub-factors of the church interpersonal trust scale used in this study. In addition, benefit-based factors such as taking an active role in resolving the individual’s immediate difficulties, giving practical help, and telling good stories to those around them that enhances his or her reputation can be said to be concretely practicable.

In other words, the Christian position is that an individual’s healthy life and happiness are completed by maintaining an amicable interpersonal relationship based on the relationship with God (

K. Kang 2010). From this point of view, the results of this study lead to a new recognition of the importance of interpersonal relationships and trust within the church as much as the importance of religious belief. In addition, it emphasizes the need for various studies, such as program development based on interpersonal trust factors as well as spirituality in terms of church organization management. Moreover, the functional relationship between spirituality and interpersonal trust in the church is the basis for establishing standards and guidelines for Christian relationships and role theory based on biblical teachings. This is expected to be useful for counseling, guidance, and education.

The limitations and suggestions of this study are as follows. First, since this study was conducted only on Christians, there is a limit to generalizing and interpreting the study results to all religions. Therefore, we propose a follow-up study to explore the main causes that affect the spiritual experience in various religions such as Catholicism. Second, there is a limit to generalizing the study results to all Christians because the survey was conducted using a bias sampling rather than a random survey targeting various denominations. Therefore, there is a need to generalize the results through repeated studies that expand the subject of the study. Third, since the COVID-19 pandemic has caused many changes in individuals’ lifestyles, we propose a follow-up study to measure changes in personal religious activity and church interpersonal trust after the COVID-19 pandemic is over.