1. Introduction

Over the last forty years, the number of Christians in China has significantly increased, attracting the interest of various researchers. In this growing scholarship on Chinese Christianity, recent studies have explored the various types of church–state relationships (

Yang 2012;

Koesel 2014;

Reny 2018), the entrepreneurial “Boss Christians” (

Chen and Huang 2004;

Cao 2011), the Chinese Pentecostal movements (

Yang et al. 2017;

Inouye 2019), and relations between Christians and broader Chinese culture (

Harrison 2013;

White 2019). To depict this diversification of Chinese Christians, some scholars advocate for the notion of Chinese Christianities and argue that “there are so many variations in meaning and social function that from a sociological point of view it is best to talk of Christianities […] It is best to see them as a separate religion” (

Madsen 2017, p. 320;

Vala 2019). In fact, the Chinese administration itself institutionalizes this division by recognizing Catholicism and Protestantism as two distinct religions (

Goossaert and Palmer 2011, p. 58).

1 However, outside of China, Catholicism and the many forms of Protestantism—as well as Eastern and Orthodox traditions—are usually presented as one religion. So, in China, is there one or many Christianities?

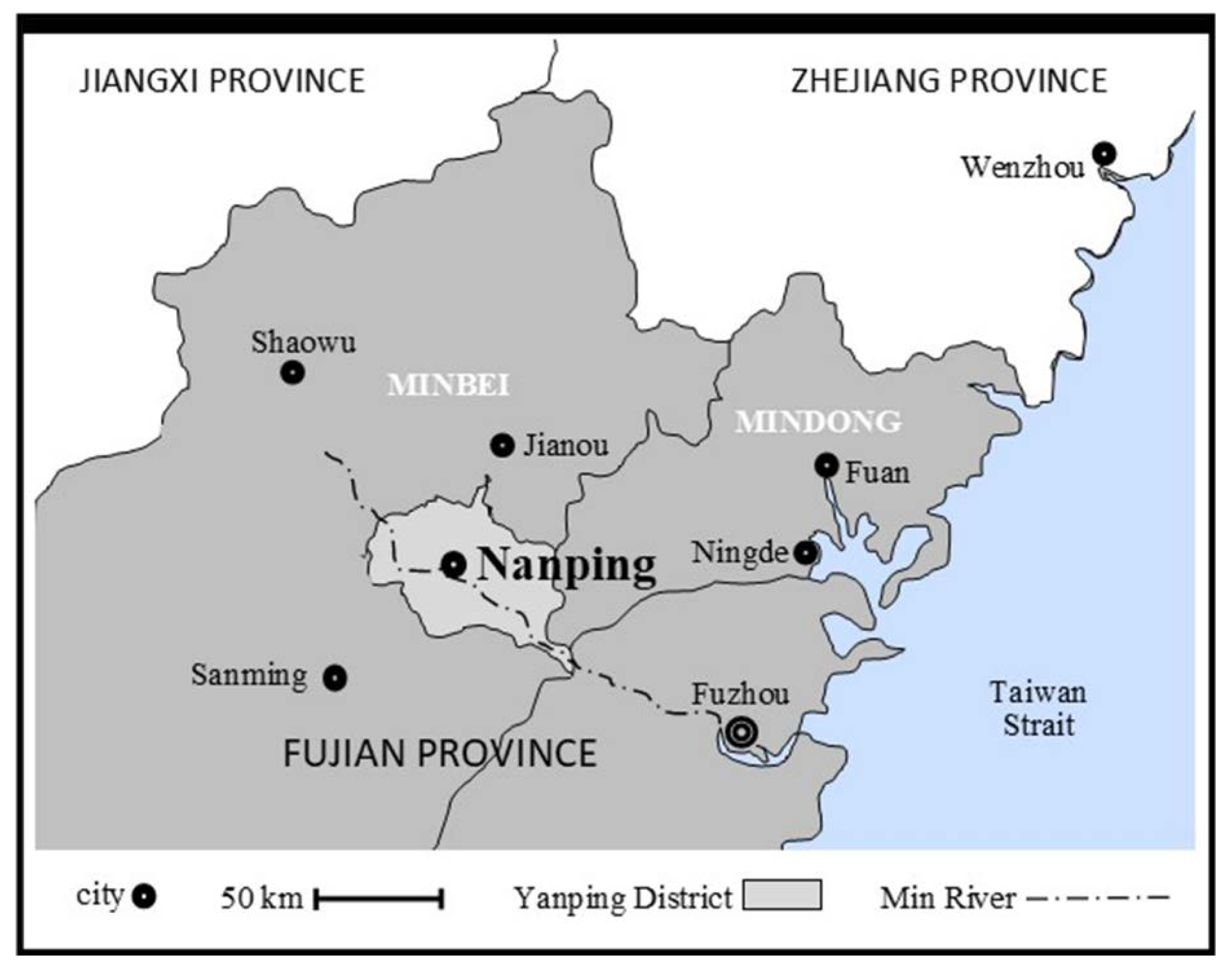

2To discuss scholarly ways to portray religious diversity, this article explores six Christian networks in one small city of southern China and investigates the ways in which churchgoers draw boundaries among themselves. It argues that, first, local Christians have constantly reshaped the ways in which they produce their religious communities, identities, and boundaries. Second, in this evolving landscape inscribed in socio-political changes, Nanping Christians operate in relation to two peculiar entities that stand beyond their own communities and transcend their interdenominational borders, namely, Christ and the Church. Although they each have different understandings of and relationships to those entities, they also consider that Jesus Christ and his Church exceed their own congregation. Consequently, their concerns about those two entities impact the ways in which they define their religious organization and negotiate interdenominational boundaries. Thus, Christianity in Nanping should not be reduced to the mere juxtaposition of six self-sufficient Christian groups, but should be apprehended through a more complex model wherein religious commitment is deployed through communal belonging and inter-personal relations to various understandings of Christ and the Church.

In addition to annual visits to Nanping between 2013 and 2019, data were collected during ethnographic fieldwork conducted from January 2015 to May 2016. Through participant observation, I stayed at the elderly home of the Gospel church and repeatedly joined the religious services of each Christian network as well as their other social gatherings and charities. In addition to countless formal and informal conversations, I conducted over 40 semi-structured interviews with leaders and participants of the different churches, asking approximately 30 structured and unstructured questions about socioeconomic status, personal Christian journey, modes of participation in church, views on other churches, and relationships with non-Christian believers and practices. Additionally, I collected observations made on Christian material artifacts such as churches’ cornerstone (dianji), buffered hymnals, and named and dated pews. Over these years, I also had recurrent opportunities to question five local state officials and 15 non-Christian religious specialists of Nanping. Finally, I consulted archives and library resources abroad when they were available.

The study focuses on the city of Nanping, the seat of the Minbei prefecture, but also includes observations from its surrounding district, Yanping. This territory counts 504,500 inhabitants, with a large majority of them living in the city (see

Figure 1).

3 Local Christians organized six autonomous networks and a few other informal groups. Local Catholics form two different networks, one willing to collaborate with the administration (also called the Patriotic Catholic Church, ±150 churchgoers) and one rejecting any kind of cooperation (also called the underground Catholic Church, ±400 churchgoers).

4 Other Christians are divided into four networks that are comparable to denominations. They are the Adventist community (±100 churchgoers), the Christian Assembly (±1000 churchgoers), the Gospel church (±4000 churchgoers), and the True Jesus church (±600 churchgoers). Although five of these networks are officially registered—which does not necessarily mean that they intensely collaborate with the administration—the city also hosts at least two unregistered groups of 10 Christians each, which regularly worship outside of any pastoral and political regulation. While the literature would recognize them as “House Churches” (

jiating jiaohui), they claim they are too few and too informal to be called so, and prefer the term “house gathering” (

jiating juhui).

5In the following section, the article lays out the history of Nanping Christians and explores how their different networks and traditions have been translated over time. For a matter of clarity, I use the term “church” (lowercase) for places and communities, and “the Church” (uppercase) for the peculiar entity, a semi-transcendent being, that Christians constantly refer to in various ways.

2. Nanping Christians before 1979: A Brief Historical Overview

2.1. The First Christian Presence: The Catholic Church

It was Father Wu, the official Catholic priest of Nanping, who first mentioned to me the long history of local Catholicism. Research confirms that the Jesuit Giulio Aleni through his acquaintance with state officials founded a Catholic mission in Nanping in 1625 (

Lippiello and Malek 1997). By 1703, the mission counted about 600 to 1000 Catholics with 100 baptisms per year (

Dehergne 1961, p. 360). With the proscription of Christianity in China in 1717, Chinese Catholics faced persecution, deportation, and decline. However, new religious institutions (Dominicans, Paris Foreign Missions Society) were successively in charge of this mission, and supported its survival. With the Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860) and the Unequal Treaties, a missionary presence was re-authorized, and in 1897, a church was rebuilt in Nanping, before being expanded again in 1926. By 1949 and the victory of the Chinese Communist Party, the Nanping Catholic church had become a part of the Archdiocese of Fuzhou, and therefore, was supervised by Spanish Dominicans. Yet, the rest of the actual Minbei and Sanming prefectures were not yet a formal and single Catholic diocese. They were two distinct Apostolic prefectures (Jianou and Shaowu), each supervised by different missionary congregations (the German Salvatorians and the American Dominicans of the Province of St. Joseph) with their own traditions and history (

Tiedemann 2008, p. 34).

6Today, elderly parishioners recall how, at the end of the 1930s, the war with Japan and the recurrent bombing of the Fujian seacoast pushed many Catholic fishermen—the Tanka—to migrate toward the upper Min River. Speaking their own dialect and living sparingly on the river with their distinct lifestyle, those believers did not merge with the Nanping land-based Catholic population, but created their own sub-community visited by Nanping Spanish missionaries. Nanping Catholicism was divided by ethnicity and social class.

2.2. An Alternative Christian Presence: The Methodist Mission

With the Unequal Treaties of 1842, Protestant missionaries also began to penetrate Fujian more permanently. Two large marble platforms present in the entrance of the Nanping Gospel church explain that in 1866, the American doctor Nathan Sites visited Nanping for the first time (

Sites 1912, p. 78). Soon, a Chinese convert established a local mission and opened a Christian bookstore. In 1901, the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society sent two American female missionaries to support the recently established schools and dispensaries. In 1924 at the peak of the American presence, 30 missionaries lived in Nanping and served the mission (

Overholt 1980). Hand-in-hand with local Christians, they operated a modern hospital, a leprosy hospital, several rural dispensaries, Christian bookstores, two boarding middle schools, and forty-seven rural primary schools. Yet, during the 1930s–1940s, the rise of communal violence and the war with the Japanese empire, as well as the post-1929 financial depression of American missionary societies, caused the number of American Methodist missionaries to decline drastically. However, the strong involvement of local Christians allowed the Nanping Methodist church (the Gospel church) to maintain its various social institutions and to attract a wide range of converts.

2.3. Missions, War, and Migrations: The Arrival of Other Protestant Denominations

In the 1920s–1930s, while armed conflicts and factional violence spread across the region, several other Protestant denominations took root in Nanping. According to today’s Nanping Adventist churchgoers, their first missionaries passed by the city as early as 1921. Then, John Sung, an influential itinerant missionary who inspired the Little Flock Movement, visited Nanping several times in the early 1930s (

Ireland 2016). With the Japanese bombing of Fujian’s coastal areas in 1937–1938, many people fled inland toward mountainous regions. Among those unfortunate refugees, some were Christians rooted in various Protestant traditions. Hence, the conjunction of migrations and missionary efforts brought three new groups of Christians to gather in Nanping: the Christian Assembly (also named the Little Flock

juhuichu), the Adventist church (

anxirihui), and later, the True Jesus church (

zhenyesu jiaohui).

7Similar to Tanka Catholics, Protestant refugees had more limited access to local and international resources, and ended up in a lower social position compared to the better-established and educated Methodists. Therefore, before 1949, Nanping Catholics and Protestants were neither homogenous nor unified communities. They witnessed religious differentiations fueled by migrations, ethnic belonging, social class, theological disagreement, and missionary work.

2.4. The Maoist Era and Its Effects on Nanping Christians

The end of the Sino-Japanese war and the victory of the Communist Party brought a new order into the region. Yet, remaining tensions between Communist China and Nationalist Taiwan prevented new provincial authorities from building important infrastructures and factories on the coast. Instead, they favored inland territories such as Nanping. In the 1950s, a few large-scale factories were built in its vicinity and brought new inhabitants into the city. This also diversified the traditional economy of the region that was until then rooted in tea, wood production, and river trade. During the 1960s, Nanping became the key node of the entire Fujian rail network and one of the main industrial sites of the province, allowing its population to escape from the deepest deprivations of the Maoist era (

Lyons 1998, p. 411).

However, the new religious policy of the Chinese Communist Party gradually forced the remaining foreign missionaries to leave the region (

Overholt 1980). Soon, all Christians had to withdraw from the public sphere while losing their foreign connections and external support (

Bays 2012). By the end of the 1950s, Nanping Methodist schools and hospitals were taken over by the state, and Christian social involvement appeared virtually impossible.

This anti-religious policy had different effects on local Christian groups. For instance, Catholics found themselves without a priest. Maintaining access to the sacraments and communicating with the head of the Fuzhou archdiocese became difficult. Additionally, the Party prohibited them from following the authority of the Holy See, creating a split between those promoting accommodation with the new regime and those advocating for antagonistic resistance (

Madsen 1998). In northern Fujian, most of the Catholic clergy went underground, and a new type of division emerged within Catholic communities. Political positioning became a more salient discriminating factor than ethnicity and social status. However, during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), all forms of religious life were actively proscribed and the political division lost parts of its significance. In Nanping, local Catholics explain that they relied on just a few nuns to gather and pray secretly (

Chambon 2019). Once again, Nanping Catholicism became a family-based religion surviving outside of governmental and clerical oversight. Being a Catholic was part of the filial piety transmitted by parents to their children and grandchildren. Decades later, many Catholics continue to underscore how their faith “

comes from [their] ancestors (

jiazu)”.

The situation was different for other Christians. Since the end of the nineteenth century, Methodist missionaries had encouraged the training of local pastors and missionaries, as well as the creation of a wide range of responsibilities among fellow Christians. Elderly Christians explain that this dense network of ministers allowed the Gospel church to temporarily maintain some collective activities. Similarly, other local Protestant denominations were not dependent on foreign missionaries, and many members claim that they continued to privately practice their faith. Still, when the anti-religious policy became stronger, men tended to unmark themselves from any Christian affiliation in order to avoid political stigma. Interviews suggest that it was mostly women who clandestinely continued to pray and sing hymns.

Today, Nanping Christians recall stories of secret gathering for Catholic rosaries and hidden Protestant worship for the Lord’s supper (

shengchan). “

When someone was sick, some would go and pray for them (…)” recalls an 85-year-old member of the Christian Assembly.

8 However, like elsewhere in China, churches disappeared from Nanping public life and only a few Catholics and Protestants continued to secretly maintain their Christian commitment. Unlike other parts of China where underground Christians were actively proselytizing (

Cao 2008;

Goh et al. 2016), interviews suggest that both Nanping Catholics and Protestants did not try to proselytize. Local Catholicism turned into family-based identity and devotions. Protestantism became an individual practice, a cultivation of the self, performed mostly by women. Unlike in other deprived regions, the relative prosperity of Nanping during the Maoist period seemed not to have generated a sense of despair, or a need for miraculous healing. Without a broader search for salvation and an incentive for a religious quest, there was no apparent growth of Christianity within the Maoist Nanping.

Significantly, the same social and political environment did not generate the same Catholic and Protestant responses. If both types of Christians restrained from proselytism and disappeared from the public sphere, Catholics found themselves divided along new political lines and reorganized around kin relations. Protestantism evolved toward a more privatized, individualized, and ritualized practice predominantly performed by women. In both cases, ways of being Christian, expressions of religiosity, and modes of bonding had been deeply remodeled. In these historical circumstances, some individuals found new ways to cultivate their faith, but most of their pre-existing “religious communities” disappeared.

3. The Reform Era and the Reshaping of Christian Communities

With the Deng Xiaoping reforms at the end of the 1970s, the socio-economic reality of Nanping quickly evolved. With the “opening” of the People’s Republic of China, urban hubs of the Fujian coast allowed new forms of entrepreneurship and attracted investments. While these zones modernized quickly and attracted people and resources, the mountainous Nanping prefecture began to stagnate. Soon, Nanping, which was a place of relative prosperity, began to lose its appeal.

At the end of the 1980s, the Min River that connects Nanping to Fuzhou was also redesigned. The construction of a dam to produce electricity flooded the majority of agricultural lands and stopped most of the river traffic. The traditional wood transport and the fluvial economy that Nanping oversaw gradually disappeared. In this period of national economic boom, Nanping faced economic decline.

In terms of social mobility and migration, many people from poorer Fujian districts left their hometowns to migrate toward large cities and foreign countries in search of economic opportunities. Over the years, those migrants have created worldwide networks of collaboration and prosperity (

Pieke 2004;

Chu 2010). However, people from the relatively wealthier Nanping district followed their own migratory pattern. Many moved either to Nanping, Fuzhou or Xiamen. However, they mostly remained inside the province, operating under their regional migratory networks quite distinct from the rest of the Fujianese diaspora. Today, the relative lack of international connection keeps Nanping Christians away from major international connections and political suspicion. During interviews, several officials insisted that in Nanping, unlike in nearby places, Christianity was “

all a local thing (

dou shi bendi de).”

In terms of religious evolution, the 1980s–1990s did not leave the religious sphere untouched, and Chinese society went through a major religious revival (

Goossaert and Palmer 2011). In Nanping, individual actors and family clans rebuilt ancestral halls around every single village, while religious entrepreneurs, lay faithful, and religious experts invested in the reconstruction–creation of numerous temples and rituals that nourished the rebirth of Chinese popular religion.

9 By the early 2000s, Nanping had recovered a robust religious life that continues to shape the local culture and sociability (

Ma 2002). Over the past years, new and large temples keep appearing in the vicinity of the city, large-scale village festivals attract worshippers from the entire province, and religious expertise stays under high-demand.

In this general trend of socio-religious transformation, Nanping Christians were not less committed and creative than their fellow citizens in reforming their religious life and its public visibility. Yet, during the 1980s–1990s, local Catholics and Protestants followed several reforming paths that we now need to present.

3.1. The Complications of the Catholic Rebirth

In the early 1980s, when the Chinese state re-allowed the public existence of Catholic communities, the two strongest Catholic hubs of Fujian—Fuzhou and Fuan

10—began to send more underground priests across the mountains to firmly reconnect with local Catholics. Although Nanping Catholics were few in number and isolated, underground networks slowly revived. The city of Nanping found itself part of the Fuzhou underground network, while the rest of the prefecture became a part of the Fuan one (see map). Civil authorities responded by encouraging the establishment of a local official church. To overcome the absence of clergy, the Bureau for Religious Affairs (BRA) encouraged consensual priests and nuns from the official dioceses of Fuzhou and Mindong (Fuan) to relocate to Minbei. In March 1995, the young Nun Shi agreed to move from Fuzhou to Nanping where the old Nanping Catholic church was reopened and liturgies were rescheduled by a young Father Wu from Ningde (

Chambon 2019). But in 1999, the provincial BRA reorganized the map of Fujian Catholic territories and, without papal approval, created a unique diocese for the entire Minbei and Sanming prefectures. This new official “Minbei-Nanping Diocese” includes parts of four pre-1949 ecclesiastical territories that each had different Catholic heritages and populations (

Cassidy 1948). Simultaneously, the senior leader of the Nanping United Front

11 supported the reconstruction of the old church with the hope of strengthening the registered community. With the financial support of various benefactors, including the Nanping Gospel church, a newer and larger church was completed in 2000. Nonetheless, Fuzhou and Fuan underground clergy continued to secretly visit local Catholics, encouraging them to not collaborate with the patriotic community.

Whereas the new church was inaugurated in Nanping, the Chinese authorities pressured a priest from the Mindong prefecture, Father Vincent Zhan Silu, to become the new official bishop of the Mindong Diocese. His episcopal ordination occurred without a papal mandate in Beijing on 6 January 2000, while the pope was simultaneously consecrating twelve bishops from around the world in Rome’s Saint Peter Basilica to mark the Great Jubilee of 2000. In response to the Chinese illicit ordination and its puzzling timing, the Holy See excommunicated

latae sententiae Mgr. Zhan Silu (

Chan 2012). The underground clergy of Mindong Diocese, as well as many Catholics across China, interpreted this rather strict and rapid decision as a clear papal signal encouraging Chinese Catholics to not collaborate with the state-sanctioned “patriotic church”. Subsequently, tensions between Nanping’s registered and unregistered Catholics increased, the bourgeoning official community found itself under intense suspicion, and most Catholics decided to remain “faithful to the Pope”, and therefore “underground”.

In sum, the rebirth and assertion of Catholic ecclesial boundaries in Nanping during the 1980s–2000s occurred through the convergence of multiple actors and factors. In addition to the multidirectional involvement of local and regional Catholics, the non-necessarily coordinated actions of local, provincial, and national state officials, as well as the involvement of the Vatican, were crucial in redefining ecclesial boundaries between overlapping Catholic territories, but also between what will become underground and official communities. By the beginning of the 21st century, regional and international dynamics had deeply reshaped the religious status of Nanping Catholics and their communal differentiations.

3.2. The Rebirth of Nanping Protestant Churches

In the early 1980s, Nanping Protestants were also allowed to publicly reappear and to recover some former properties. Three pieces of land progressively returned to the Protestant

lianghui (a church-state entity englobing and supervising all Protestant communities across the prefecture): the former main church of the Methodist mission, the former land of the Little Flock group, and later, a piece of hill-top land owned in the past by Methodist missionaries.

12 In 1980, Christmas was publicly celebrated at the Gospel church, and then, religious services were held in the two churches around a local elderly Christian who was ordained pastor for the occasion. Today’s Christians from the Gospel Church and the Christian Assembly recall that, during the 1980s, Bible study groups multiplied (

Chen and Li 1998) and “

more and more people came and believed in Jesus.” Some were moved by the example of their Christian grandmother who had secretly kept her faith, some were in search of healing or ways to cultivate themselves and their society. However, as a woman in her mid-fifties describes, “

I was used to going back and forth between the Bayi [today’s Christian Assembly] and Gospel churches (…)

Our activities were at one or the other. But my Bible group was mostly in my district where we would meet at home. Back then, we couldn’t buy a district meeting point (

juhuidian) (…).” In fact, inter-denominational boundaries stayed unmarked and cornerstones of buildings erected during this early period refer to “Christians of the city of Nanping” as the constructors.

However, the 1980s–1990s also brought several waves of apocalyptic fears and millenarian movements across the district. Interviewees still recall how the imminent end of the world and the destruction of earth were common concerns at that time. On the one hand, these popular anxieties drove many to embrace the Christian salvation message. On the other hand, they questioned and challenged the rather undefined post-1979 Christian teachings on the end of the world, the power of Christ, and eternal life. These millenarian movements encouraged different Protestant approaches on healing, biblical teaching, and ecclesial traditions to reemerge.

Among new local converts, Thomas Sun,

13 a young man who wanted to become a historian and who developed a passion for Christian scriptures, began to study theology in Fuzhou and then at the Nanjing Union Theological Seminary. In 1986, he was back in Nanping and served on a remote edge of the district. In 1987, though, the old pastor was murdered by someone mentally unstable. Thus, Sun became the only theologically trained leader of the growing local Protestantism, and on 5 January 1992, he was ordained pastor in Beijing.

The emergence of a young, legitimate, and assertive leader pushed those in favor of a more equalitarian approach to revisit the Little Flock heritage. Subsequently, the expanding Protestant population of Nanping reorganized itself into two increasingly distinct traditions: the hierarchical but socially engaged Gospel church re-claiming a Methodist heritage, and the egalitarian and apolitical Christian Assembly at the smaller building. Nanping Protestants who were used to circulating between the two places of worship slowly identified with one place and one tradition.

It is also in this context of millenarian concerns and numerical growth that a few Christians adhered more closely to the Adventist teaching and its strict dietary rules. Others were more inspired by the distinct Pentecostal input of the True Jesus church tradition. A leader of the True Jesus community explains: “You know, traveling became easier. It was [legally] possible to go to Fuzhou and Fuqing in order to visit [Christian] brothers and sisters and join their activities. (…) The [True Jesus] church is very strong there. It is impressive. (…)” Through those circulations, some Christians found the strength to locally reaffirm the superiority of the Adventist and True Jesus traditions, and to gradually become self-sustainable and distinct communities outside of the Gospel church.

Yet, during the first half of the 1990s, people interested in the True Jesus church did not have their own building. Since they were becoming too numerous to gather within private homes, they used the Gospel church for their service. Christians of the two communities explain that since the True Jesus church worships on Saturday mornings, it did not interfere with the Sunday services of the Methodist tradition. However, it is important to highlight that such a sharing of space would have been unthinkable with other religious traditions. Nanping Christians will never gather and worship within a Buddhist or Taoist temple. This suggests that there is something beyond their own community, and its buildings, something that allows proximity in diversity and that we must consider in order to explain how local Christians navigate between inter-denominational closeness and separation.

Nonetheless, in 1997, churchgoers of the True Jesus church were able to gather enough funding and political support to complete their own building in a suburb of Nanping. In this period of re-denominationalism, the cornerstone specifies: “

Set apart for Jehovah, True Jesus church, Nanping hall, 1997, March 30th.” Soon after, this indigenous Pentecostal community distanced itself from the locally dominant Gospel church. This was accelerated by the fact that Pastor Sun had embraced Pentecostalism at the end of 1999 after encountering Dennis Balcombe in Singapore. Followed by other local leaders and churchgoers, the Gospel church then became a pioneer in integrating Pentecostalism within national Three-Self Protestantism.

14 This trinitarian Pentecostalism, though, differs from the oneness Pentecostalism of the True Jesus church. Additionally, speaking in tongues was no more the reassuring marker of the True Jesus tradition alone.

15 Thus, True Jesus churchgoers reasserted physical and discursive distance from the Gospel church in order to highlight how their Pentecostal tradition was radically distinct and uniquely true. Leaders claim that “

when they speak in tongues [at the Gospel church], it’s people who speak, not the Holy Spirit.” Today, these two networks have limited institutional relations. Yet, I met some churchgoers who continue to circulate between the two like they did in the past.

In summary, it was during the 1990s that Protestant denominations were firmly reestablished in Nanping, as they were in Fuzhou (

Guest 2003, p. 107). Besides the increasing number of Protestants that allowed alternative traditions to become financially and logistically self-sufficient, the emergence of strong Protestant leaders with specific ecclesiological and theological views, correlated to a milder political control, facilitated this differentiation process. This was also fueled by broader non-Christian socio-religious movements, such as apocalyptic fears, which theologically challenged post-Maoist pan-Protestantism and generated a plurality of Christian answers. The continuous improvement of transportation infrastructures also increased the provincial and national connectedness of Nanping Christians, helping smaller Christian movements to regain religious capital and collective confidence to the point of differentiating themselves from more dominant traditions. Similarly, the reformation of property rights with its partial privatization of ownership, as well as the progressive replacement of the Maoist work-unit system by individualized wages, allowed churchgoers to sponsor and expand their own places of worship. It was during this global transformation of the Chinese society that Nanping Christians were able to reform their religious practices, rebuild visible Christian denominations, and assert new boundaries among themselves.

3.3. The One Present beyond Nanping Christians

Up to this point, we have seen how the establishment of religious boundaries among Nanping Christians has been a contingent process, within which time, socio-political factors, and theological concerns play a central role. In other words, inter-ecclesial boundaries are not as permanent, rigid, and self-evident as they may be depicted. During the Maoist era, many Christians survived without their religious community. Later, True Jesus churchgoers in search of space were able to borrow the Gospel church sanctuary for worship. Similarly, the Gospel church made financial donations for the reconstruction of the Catholic church. Within some families, some members identify as Adventist while some go to the Gospel church. In Nanping, examples of implicit proximity and inter-denominational circulations are countless. At the same time, local Christians will never finance Buddhist and Taoist temples, nor worship there. There are some boundaries that are not negotiable. The difference between Christians and non-Christians is obviously not the same as the difference among Christians. So, what makes inter-ecclesial boundaries special?

To justify why Nanping Christians sometimes sponsor other Christian communities, interviewees consistently refer to the fact that ultimately, they all worship the same God, Jesus Christ. They may belong to different communities, favor dissimilar beliefs about God, or promote strange dietary restrictions or Marian devotions, and yet, they all identify with Christ. For them, this entity is not just an abstract idea to argue about, it is someone who lives among them and supersedes their human rules, opinions, and claims. During a follow-up interview with underground Catholics, one who was used to join the Christian Assembly explained how the blood of Christ is shared there. Surprised by the use of individual spoons to drink from a collective cup, the Catholic priest asked: “What if they let some drops of the precious blood fall on the floor? (…) It’s not very safe, they should be more cautious.” It is interesting that this rather nuanced reaction, made by an underground priest who promotes an uncompromising commitment to the papacy, focused first and foremost on the presence of Christ. Although this priest would not recognize this Protestant service as a “valid” sacrament, he was still concerned by the ways in which the blood of Christ was treated and honored—and this needs to be considered.

Scholars advocating for the recognition of a plurality of Chinese Christianities have rightly noticed that “

the very term for the deity differs in the Chinese Catholic and Protestant scriptures” (

Vala 2019, p. 2). The Chinese term for God is not the same among Catholics and Protestants. Those scholars consider this as an additional sign of a radical division among Chinese Christians. However, this approach gives rather questionable importance to vocabulary per se, and overlooks the fact that, linguistically, the Chinese naming of Jesus Christ is exactly the same across all Christian groups, i.e.

yesu jidu. Furthermore, Chinese Christians see Jesus of Nazareth as the unique way to approach their deity.

16 They may disagree on how to follow his historical example—and even argue within a single denomination—but in Nanping, they still agree that he is the only one way to God. This Christ-centered identity is even recognized by Nanping non-Christians who oppose the diversity of those who “

xin yesu” (believe in Jesus) from those who “

xin fo” (believe in “Buddha”—and the many gods of the Chinese popular religion).

In short, an understanding of Nanping Christians and of their diversified “us” requires one to acknowledge what and who motivates them. Surely, many concerns and socio-political constraints co-shape their behavior, and their perceptions and understandings of Christ vary as well. However, in the middle of their disagreements and distinctive practices, the difficult to grasp—yet deeply present—Jesus of Nazareth remains the key figure to apprehend their religious enterprise. Thus, a sociology of Chinese Christians cannot systematically ignore the particular entity to whom they keep referring. The point is not to speculate on the ontological existence of this figure, nor to supposedly portray a collective definition of Christ that all local Christians would endorse, but to map out the network of relationships within which Nanping churchgoers construct themselves and their differentiated sociability. I argue that one cannot appreciate Nanping Christians’ ability to generate separated communities, as well as their ability to sometimes ignore those separations, without integrating their particular relations to Jesus Christ. Even though investigating the wide diversity of those relations exceeds the scope of this paper, we still need to acknowledge the structuring role that the presence of this God implies. All Christian communities are “centered” on a unique and exclusive historical figure who stands beyond their distinct groups.

4. The Current Dissymmetric Equilibrium

The history of Nanping Christians does not end with the 1990s’ recreation of denominations though. In fact, they continue to evolve with and beyond the communities they have produced. Thus, this section presents the current Christian landscape of Nanping, as well as its recent changes. It points out that local Christians operate not only in relation to their communities and Christ, but also to another non-human entity, the Church, a semi-transcendental being which exceeds their specific groups and impacts their many ways of defining a congregation.

4.1. The Dominant Gospel Church

Today, the most prominent local church is the Gospel church. It is a network of Christian communities within the different townships of the district. Most of their buildings are named a Gospel church (

fuyintang). Throughout its 20 official places of worship, including 5 in the city itself, some 4000 Christians congregate on a weekly basis (

Chambon 2017). This church is socially diverse and theologically moderate. Its pastors have a rather conservative biblical approach combined with a strong social involvement. Pastor Sun is the head-pastor of the Gospel church, assisted by a pastoral team of 10 pastors, professors, and evangelists. The network is also supported by a dozen hired “co-workers” (

tonggong),

17 and 20 elected deacons who volunteer for specific ministries with elderly, young, and sick people. In its multiple churches, worship halls, and meeting points, the Gospel church organizes regular youth camps for children and teenagers, annual art performances for Christmas, Easter, and Thanksgiving, as well as weekly choir rehearsals and Christian calisthenics. Three training centers (two in a rural environment and one downtown) can accommodate a few hundred people for various activities, as well as bi-annual DTD seminars, a nationwide training program for already committed Christians that attracts people from the entire country.

18A key feature of the Gospel church is its social involvement. For years, the church has owned and run two kindergartens, each hosting a few hundred children and about two dozen educators. Although these kindergartens have a certain level of autonomy and no formal religious education, pastors monitor them closely, which is unusual in China and reveals the rather relaxed political climate of Nanping. Additionally, the Gospel church owns one large and modern home hosting a few hundred elderly residents. Most are not Christian. From 1997 to 2016, the Gospel church—like the True Jesus church—directly owned and operated a smaller Christian home for the aged. In 2015, though, the church, in partnership with private actors, opened a larger structure that meets the most recent legal requirements on hygiene, well-being, management, and fire safety. In 2018, this nursing home was the largest and finest in town, offering Christian activities without being a religious institution per se.

Overall, the Gospel church appears significantly larger than every other local Christian community. At the district level, it represents more than half of the total number of Catholics and Protestants added together. This gap in size, visibility, financial resources, and networking capacities impacts the ways in which other denominations look at the Gospel church and vice versa. Pastors and Christians from the Gospel church appear as relatively more self-confident and eventually condescending toward other Christian groups. Those, in return, appear more critical and distant toward the locally dominant Gospel church, a network that some perceive as driven by business interests and a search for power. While Nanping Christians often compare the rituals and social impact of their churches, local ecclesial boundaries and ecumenical relationships are indeed affected by the current power balance and size gap among their networks.

4.2. The “Little Rest” of Protestant Churches

The second-largest Protestant church in Nanping is the Christian Assembly. In 2019, this community hosted some 1000 churchgoers. They gather on Sunday mornings on the second floor of a modern building downtown. This multi-story edifice, erected on land returned in the 1980s, is mostly filled with apartments rented by local officials who work across the street. The Christian Assembly occupies only the two bottom floors, and signifies its presence with a large red cross on the front of the building. In town, the Christian Assembly is known for its “bonnets” because married women come to the sanctuary with their heads covered with a small black bonnet (see 1 Co. 11:5). While the Gospel church and Christian Assembly share similar views on biblical teaching, they diverge in terms of church leadership and social involvement. The Christian Assembly operates under the guidance of one ordained elder and seven deacon/evangelists who are reelected on a regular basis. One of these deacons emphasizes: “In our church, the leadership is equalitarian, no hierarchy! (…) Everyone is responsible.” Additionally, the Christian Assembly does not seek highly visible social involvement; it only visits sick and isolated people in need, without institutionalizing an elderly home.

The third-largest Protestant network is the True Jesus church. Some 600 people form this community and gather on Saturdays within the large building they own in the suburb of the city. Besides distinctive rituals, such as feet washing, speaking in tongues, and baptism in a living body of water (river, sea), these churchgoers identify as Pentecostal (

Inouye 2019). The female preacher explains: “

When we pray, it is the spirit of Christ who speaks through us”. Yet, they do not believe in the Trinity, but refer to Jesus as the visible appearance of the only person of God, a statement perceived as heretical (

yiduan) by many other Nanping Christians.

Unlike at the Gospel and Adventist churches where women are numerically more prevalent, the True Jesus church has a rather balanced gender ratio. This community counts relatively more families, with their multiple generations. It also promotes fairly strict teachings against gambling and the consumption of alcohol and cigarettes. From 1997 to 2017, the True Jesus church had run a small home for its own elderly churchgoers in need. However, a recent inability to afford a new fire safety system caused the church to close it down.

Finally, the smallest Christian community in Nanping is the Adventist church. About 100 people gather every Saturday morning within a large apartment located at the top of an old building downtown. Additionally, a dozen worshippers also meet in Zhanghu, a township on the edge of the district (

Chambon 2017;

Ma 2002). Nanping Adventists consider dietary rules such as vegetarianism as an extremely important part of their religious practice. A 62-year-old member who converted ten years ago after various health issues explains: “

We respect the prescriptions given by God. They are good for your health. (…) Look at our elderly sisters! They walk six flights of stairs up to the sanctuary without short breath! (…)”. If all Nanping denominations promote some dietary restrictions (all Protestants prohibits the consumption of blood and Catholics do not eat meat on Fridays), many Nanping Christians point out the dietary rigor of the Adventists and mock the poor quality of their wedding and funeral banquets (

Chambon 2020).

Nanping Adventists operate under the supervision of an ordained evangelist, a young Tibetan man, who cooperates with a pastor based in Sanming. Together, they recently received the authorization to build a church in Nanping, and a piece of land has been purchased and formally reassigned for religious use.

19 Yet, without any budget left, construction work has not started. Nonetheless, Nanping has reached its legal quota of land used for Christian constructions, and this generates tensions with leaders of the Gospel church who argue that the small Adventist community has neither the need nor the funding to fully use this new land. Therefore, Pastor Sun has offered to trade financial and material support for the construction of a proper Adventist church in exchange for their current land and its rights. By the end of 2019, these negotiations were still unsettled.

4.3. Nanping Protestants beyond Nanping Territory

Before looking at the current situation of Nanping Catholics, we must notice that limiting the study of Nanping Protestants to the city itself would disregard how much they network beyond the borders of their administrative unit, and how their regional and national connectedness shapes the life of their local communities. We already mentioned how True Jesus churchgoers and Adventists benefited from interactions with fellow Christians living along the Fujian coast. At the Gospel church, university students who study in Shanghai join one specific House church recommended by Nanping fellow Christians. Additionally, Pastor Sun spends an average of one week out of four traveling outside of Nanping, visiting church leaders in Fuzhou, Nanjing, or Beijing, and gathering information and connections.

These transregional circulations are not only induced through individual initiatives, but also through formal institutions like schools of theology. All Nanping Protestant leaders, pastors, and evangelists must have studied theology at a state-sanctioned institution such as the Fujian Theological Seminary, the Nanjing Union Theological Seminary, or the East China Theological Seminary. Clergy members of the Adventist church and of the True Jesus church must also join these institutions before attending any supplementary training. In 2018–2019, the Fujian Theological Seminary hosted 140 students among, which 7 were from the True Jesus church and 4 from the Adventist church.

20 In this context of forced-ecumenism, where state officials closely monitor the curriculum, professors tend to be cautious when they discuss topics of inter-denominational disagreements, such as the Trinity, the proper day and style of worship, and Christian dietary restrictions.

21 Nevertheless, during their time at schools of theology, Nanping ministers learn not only to interact with Christians from other denominations, but also to build alternative networks of belonging that exceed their local communities and allow transregional interactions and circulations. For instance, when Pastor Sun travels outside of Fujian, he often visits his former classmates whom he met 30 years ago at the Nanjing Union Theological Seminary.

Another example of these transregional circulations is the annual provincial tour of the music band of the Gospel church. Over the past 10 years, some university students who study far away have gathered during the summer to create and repeat a two-hour-long concert made of contemporary Christian music. Then, during September’s weekends, they travel across Fujian to perform at local churches. The selection of places willing to provide the necessary support depends on the network of the junior evangelist who ministers the band. Since she studied theology in Fuzhou, she knows many young Fujianese ministers who are willing to mobilize their local community in order to properly prepare the coming of the band, the related logistics, and the pre-advertisement so indispensable to a successful concert.

Clearly, the investigation of Nanping churches must be apprehended within and beyond the boundaries of their city. Through travel, study programs, and networks of classmates, Christians construct various forms of exchange and connection, and these extra relations impact in return the dynamism and style of their home church.

4.4. Catholic Internal and Regional Struggles

On the Catholic side, two communities continue to operate side by side. On the one hand, the unregistered community counts some 400 people who discreetly gather on Sunday mornings under the porch roof of an old building. They identify as being a parish of the archdiocese of Fuzhou. Their meetings are illegal and face the risk of a police raid. A few lay patrons organize the financial and logistical support necessary to secure the hosting of a priest and a nun, both coming from Fuzhou underground networks and who serve their community. At their unauthorized masses, the presence of children, young adults, and older churchgoers suggests that entire families remain the backbone of this network. Unlike Protestant churches that have recently grown quickly by attracting middle-aged women who often are the only Christian of their family, most underground Catholics continue to live their faith not only as an individual matter, but as a resilient loyalty toward their family heritage.

On the other hand, the registered community counts some 100 regular worshippers, supported by one priest from Ningde and one nun from Fuzhou (

Chambon 2019). This parish is part of the official diocese of Minbei, an ecclesial territory not recognized by the Holy See and without a bishop. The parishioners’ average age is higher than among unregistered Catholics, and despite the presence of a few converts, churchgoers are concerned by the fragile and aging nature of their community. Nun Shi does not hesitate to explain: “

We are not like the Gospel church. We don’t have money to organize new activities (…) And our youth have left Nanping.”

However, the boundary between these two Catholic communities remains unstable. On 22 September 2018, Pope Francis suddenly lifted the excommunication of Mgr. Vincent Zhan Silu, the official bishop of the Diocese of Mindong.

22 He was then formally reintegrated into the communion of the Catholic church and the local unregistered bishop, Mgr. Vincent Guo Xijin, became—in the eyes of the Vatican only—his auxiliary bishop. The Holy See also signed a Provisional Agreement with the People’s Republic of China to clarify the selection process of bishops in China (

Madsen 2019). In April 2019, local authorities turned blind eyes when the two bishops celebrated Easter together, suggesting that officials were willing to implicitly acknowledge the episcopal status of Mgr. Vincent Guo. Later, though, things worsened, and Mgr. Guo stepped down. These different events and their significance were heavily commented by international observers and Chinese Catholics. Nonetheless, while these regional and international developments remain fragile and under debate, they impact relationships between registered and unregistered Nanping Catholics. Again, local ecclesial boundaries and reconfigurations are not pre-defined, but are correlated to many non-local factors that impact the way in which Nanping Catholics divide or unite.

4.5. Belonging to One Church

Despite their binary separation, Nanping Catholics refuse to present their division as the formation of two Catholic churches. A 50-year-old layman of the underground community who grew up as Catholic explains: “We are two communities (tuanti) of the only Church. My family and I, we don’t want to follow the Patriotic association. It doesn’t bring any good to the Church”. However, each Catholic community envisions itself as the better one. These discursive nuances that assert distinctions between a community, a church, and “the Church” (jiaohui) are also present among Nanping Protestants who often talk about the Church as if an entity is standing beyond their specific community. Indeed, the Church is not the mere network of a pastor nor an association gathered around a spiritual tradition. Even if it may take the appearances of a filial family clan, or of a group of common interest, Nanping Christians depict the Church as an ideal entity that exceeds social contingencies and belongs to Jesus Christ. During interviews, churchgoers often referred to the Church as a source of agency and decision to explain Christian rules and collective actions. Expressions like “the Church says” (jiaohui shuo) are common across the six Nanping Christian networks. In an exemplary case, a male member of the Gospel church in his mid-forties, who converted ten years ago after the sudden death of his girlfriend, referred to “our Church” (women de jiaohui) while explicitly talking about all local Christians, Catholics and Protestants, in opposition to non-Christians.

Thus, the notion of the Church is paradoxical. Each community, network, and local church sees itself as the Church, and yet, they agree that the Church is not limited to a specific congregation or group. For True Jesus churchgoers and Adventists, their local assemblies are clearly a part of a more global entity, the worldwide True Jesus church or Adventist church. Similarly, Christians of the Gospel church consider most mainline Protestant churches—Chinese and not Chinese—as being the Church.

Therefore, a sociology of Nanping Christians needs to distinguish between specific local communities formed by churchgoers and the ideational entity named the Church that exceeds those formal groups. It is not to say that all Christians claim to belong to the same and unique Church. For instance, leaders of the Nanping True Jesus church do not consider that members of the Gospel church and Catholic communities are part of the true Church. For these leaders, the path of those “Christians” toward Jesus Christ is incomplete. On the other side, the Christian Assembly and the Gospel church consider each other as being parts of the same fundamental Church, the same body of Christ. Consequently, the exact scope and implications of the Church vary. When Nanping Christians generate communities, though, they all reproduce this dialectical tension between their specific congregation and the semi-transcendent Church. There is a pattern of belonging within which something else than their God exceeds and relativizes their local congregation. They all relate to an acting semi-transcendent being that offers communal belonging and moral models while exceeding spatial and temporal limits. While understandings of the Church differ, its structuring and paradoxical presence remains.

In conclusion, a socio-anthropological analysis of Nanping Christians requires we acknowledge the multiple levels of belonging and identification that Christians generate. Individuals who create and identify with Christian communities have various ways to articulate their religious commitment to Christ, their congregation, and the Church. Nonetheless, an understanding of inter-ecclesial borders cannot reduce Nanping Christians to the juxtaposition of pre-existing, self-reproducing, and distinct religious communities. Rather, it must integrate how Christians engage with properly Christian entities—Christ and the Church—in negotiating their socialization and differentiation processes.

5. Conclusions: One or Many Christianities?

In Nanping, local Christians create a limited number of ecclesial communities with distinctive features, but also cultivate inter-ecclesial relations, share organizational patterns, and acknowledge those who relate to Jesus Christ. Side by side, they produce a vivid, diversified, eventually divided, and yet channeled Christianity. The ways they generate and transform their communities are informed by various factors and actors, such as historical legacy, missionary action, ethnicity, migration, economy, and religious policies shaped at local and non-local levels. At the same time, these multidimensional networks of relationships with changing boundaries and identities strive to relate to the historical Jesus Christ and his Church. Therefore, they are not only made of human monads, but also of these two distinct beings, which remain a common feature of Christian communities.

These findings invite us to further question the theoretical and methodological approaches that one applies in discussing the unity and diversity of Chinese Christians. Which kinds of entities, factors, and actors do we explicitly include—and implicitly exclude—in our analysis? Nanping Christians suggest that we should not limit our investigation to human beings alone, as if they could exist independently from the material needs, social forces, and virtual entities that they rely upon. Thus, socio-anthropological analyses of religious groups need to develop their own models of investigation in order to fully consider the variety of inter-acting entities they engage with.