Abstract

This ethnographic research on the territory of Palermo is a comparison between the old immigrant Tamil generations, coming from Sri Lanka, and the new, native residents of Palermo. There are two points of generational convergence in the community: the cult during the festive rituals of Santa Rosalia, and the territorial symbolism of Mount Pellegrino. This peculiarity, qualitatively analysed through the NVivo software, is revealed by two specific and organized events: the first by the archbishop’s curia and the second by the community itself. The first consists of the participation in the day dedicated to interreligious dialogue (from 2014 until today), and the second is the night of the “acchianata” (ascent) on 3 and 4 September. The day dedicated to “interreligious dialogue” involves the meeting of all confessions/religious communities in Palermo, creating an annual meeting ritual under the sign of Santa Rosalia.

1. Introduction

This sociological study of qualitative and ethnographic research has as its object of analysis the new generations of the Tamil community who were born and raised in the city of Palermo, and that of the older generations, mostly from Sri Lanka. The point of convergence is found during the festive rituals linked to the cult of Palermo’s patron saint, Saint Rosalia.

The two most important events are the day dedicated to “interreligious dialogue”, created with a view to a “mutual sharing” of the festive cycle, and 3 and 4 September each year, which is dedicated to the pilgrimage to Mount Pellegrino.

The analysis of the religious socialisation of the new Tamil generations was carried out during these two major events in the festive cycle dedicated to the Saint.

The study took place through ethnographic fieldwork, on the night of the pilgrimage, and textual analysis of the speeches and messages that Archbishop Lorefice delivered on the day dedicated to interreligious dialogue.

The ethno-qualitative research methodology made use of participant observation and was supported by NVivo software. In addition, video and photographic documentation of the messages addressed to the Saint and written in Tamil and Sicilian were also studied (Appendix A).

The active participation of the religious communities in the day dedicated to the meeting of the different religions present in the city of Palermo has produced the ritual of an annual meeting under the sign of Saint Rosalia. The special features of the pilgrimage, distinguished by the presence of the Tamil community, thus creates a meeting between the Hindu and Christian religions.

Of all the foreigners living in Palermo, the first generation of Tamils have a special story: they are refugees who, after being granted political asylum, have gradually tried to rebuild a dignified and peaceful life in the city of Palermo. What motivates the Tamil community to share the Saint Rosalia festive cycle? What “tradition” linked to the “holy mountain” pushes them to create and maintain a close link with the territory of Palermo and its patron saint? Why do they “climb up” to the sanctuary, not only during the pilgrimage in September, but every Sunday?

Over the years of research, I have been given various explanations and answers to these questions. One explanations interprets the devotion to the Saint as a request for the protection of the city and its children. Yet another sees a similarity between such a colourful and flowery woman, and the equally flowery and colourful oriental deities.

If Saint Rosalia is sung in Italian, Shiva is sung in Hindu. Moreover, the sanctuary of Palermo’s patron saint has become a temple in which, for the Tamils, Rosalia represents their divinity. Inside the cave, in the sanctuary on Mount Pellegrino, the central altar is dedicated to the “Virgin Mother of God”, and the “Conception”. The Tamils find the “Great Mother” in her, she who protects marriage and children. Similarly, in the Hindu religion, Durga, identified as Shiva’s wife, represents feminine energy, the “archetypal woman”, or the dynamic element in the creation of the world.

What induces Tamils to participate during the day of interreligious dialogue is a territorial attachment and the sense of identity attributed to it. The feeling of belonging experienced by the second generation is revealed in the same devotion to Saint Rosalia, no longer just a Christian saint, but also their deity. It is precisely along the path of the “acchianata” (the ascent, in Sicilian dialect, ndt) that the sense of identity and the bond of belonging to the territory is expressed. This explains the reason for the pilgrimage each Sunday, and not only on the night of 3 September during the shared “acchianata”.

In the research analysis of life stories by the scholar Burgio, we read that: “Every Sunday morning it is possible to observe many Tamils at the shrine of Palermo’s patron saint on Mount Pellegrino. Many Tamils who work in private homes ask for Sunday mornings as a period of rest in order to make this pilgrimage. Often the ascent to the Mount is done on foot, as is the custom of the faithful who go there to ask for her blessings. At first, I thought it was a kind of religious “parasitism”. I thought that something of the Saint’s iconography might remind the Hindu Tamils of the characteristics of some deity and that they would therefore use the shrine by giving a new meaning to its symbolism. I thought, for example, that the presence of the Saint’s skull (the memento mortis) could be reconfigured as a characteristic of the goddess Kali, who is often depicted with a necklace of skulls. In reality, the motivation is typically Hindu: “God is one but has many names, one of which is Saint Rosalia”. The Catholic Saint can be included in the Hindu pantheon precisely because she is a Catholic Saint. To venerate her one has to follow the rites that everyone dedicates to her: Catholic rites. That is why Hindus pray to the Saint, not by reciting a mantra or offering an incense stick, but by making the sign of the cross! This use of the veneration of the Palermitan Saint is widespread among all Hindus, not only Tamils (Burgio 2003, p. 9).

Moreover, the scholar notes that the life stories show a lifestyle of identity and “adaptation” whereby “venerating the same deities worshipped by the Palermitans would be a sort of ‘duty of hospitality’: these are like geni loci, protective entities of the place that one must ingratiate oneself with. There is also a practical reason for this: displaying the image of Christ can be a sort of captatio benevolentiae, a way not only of preventing the xenophobia of the people of Palermo towards them, but also and above all, a way of not making Catholics feel uncomfortable. The Palermitans who enter Tamil restaurants will recognise a symbol of their religion and not feel like outsiders” (Burgio 2003, p. 9).

Therefore, it is not just a matter of sharing rituals exclusively to ingratiate yourself with the divinity or to share the Saint of the Christian Palermitans in a “communitarian” way: the intention is to integrate not as “foreigners”, or “immigrants”, but as “welcome guests”.

2. A Box for Tools

The celebrations of Saint Rosalia in Palermo during the days of the festive cycle take on different structural forms, especially with regard to the participation of social actors. New lifestyles and new forms of traditions are associated with what is called the “Feast”, and new social actors are present along the route of the pilgrimage on the night of the 3 September.

An analysis of the festival of Saint Rosalia implies recourse to a number of concepts: the “Feast”, the “Pilgrimage”, and the “Annual Meeting” with representatives of other religions on the day the patron saint is celebrated.

The Feast: the calendar cycle of the festival of Saint Rosalia in Palermo does not follow the pattern of celebrations spaced twelve months apart, rather it is characterised by repeated performances over a few weeks in the summer. This temporal rapprochement makes it possible to intervene during the celebrations in order to revise times, methods, and content according to the needs of the moment, the events that have taken place, and those which are spontaneous. In this regard, official speeches and other ritual pronouncements, as well as posters and programmes, become valuable and illuminating clues and indicators that help us understand ongoing dynamics and changes.

The festival of Saint Rosalia has been held in Palermo on separate days between July and September every year since 1625. My intention, however, is not to stop at the famous Feast on 14 July, but to look at the three official celebrations dedicated to the Saint, thus including both the procession of the reliquary urn on 15 July and the pilgrimage on 4 September.

Obviously, such an interpretation is purely exploratory and is especially valid on a methodological level. It can only be reasonably practised to the extent that it allows a more in-depth reading of the relationship between the sacred, through the rite that is celebrated, and the territory, understood not only as a socially inhabited space, but also as the set of cultural and social requests that are made on it.

The Pilgrimage: the relationship with the territory is not only limited to the comparison and the incessant interaction between an institutional and a popular interpretation of the event. It acquires a physical dimension in which the logic is reversed: the sacred that passes through the city is counterbalanced and almost “returned” by a city who goes to the sacred and passes through its space.

The nocturnal pilgrimage on the 3 September sets in motion another dynamic, that of the “irremovable sacred”, where the subject, the devotee, moves according to a specific ritual expression, for example, praying or singing, barefoot or on their knees, in silence or reciting the rosary.

Thus, one observes the use of specific symbols such as the torch kept burning during the (nocturnal) pilgrimage to Mount Pellegrino, the rosary chaplet used for prayer, and the symbolic presence of the Saint Rosalia flag (which is not only symbolic in itself, but also spiritual, since it shows the devotional images of the Saint on one side and the Madonna on the other). It should also be noted that the use and movement of the flag also takes on an apotropaic form and function.

Indeed, the festival brings together different expressions and proves to be a real vessel in which religious devotion, penitential rites, local identity, ecclesiastical commitment, and institutional presence converge.

The Annual Meeting: another identifying and significant moment used for analysing the feast is the annual meeting with representatives of other religions, which, since 2014, has taken place in the Archbishop’s Palace, during the celebrations in honour of Palermo’s patron saint.

3. The Tamil Community in Palermo

The metropolitan city of Palermo is home to the largest Tamil community in Italy, which has grown to about 8000 people since the 1980s, some of whom embrace the Hindu faith and others, just under half (an estimated 3500 individuals for the year 2003), the Catholic faith. As of 2020, the majority of Tamils live in the historic center of Palermo; the Tamil community is very active in Palermo and often organizes events to make itself visible and reveal the Tamil culture and related problems.

The prevalent type of work activity for the Tamils is assistance with housekeeping, but in recent years, some young Tamil entrepreneurs have started commercial ventures such as grocery stores or ethnic restaurants.

The reference church for Tamil Christians is San Nicolò da Tolentino (in Via Maqueda), where mass is celebrated in Tamil.

The scholar Burgio, referring to the territorial presence of the Tamil community notes that “the identity of Sri Lankan Tamils today is constituted by a relationship based on three pillars: the diaspora communities, their host countries, and the homeland. Tamil identity appears as a complex entity, composed of several layers. Sri Lankan Tamils identify with this global Tamilness and yet, at the same time, differ in some linguistic, cultural, and historical respects. Their diasporaisation has resulted in a strengthening of identity, and Tamils in the diaspora tend to build—within the global Tamil—distinct communities. Community identity is constantly nurtured through active, collective, and cultural reproduction. At the same time, each Tamil individual is connected—through family and friendship networks—to various nodes in the diaspora and to the homeland. And transnational practices—which are political, economic and cultural—link the homeland to diasporic communities. In short, to speak of Tamils is to include them in the theoretical framework of transnationality” (Burgio 2016, p. 116).

The first generations of immigrants immediately found a guiding figure and a deity to refer to in the patron saint of Palermo.

The community based in Palermo, although different from an ethnic, linguistic, and religious point of view, has been able to integrate well with the indigenous population by transmitting trust and participating actively and increasingly in the expressions of the Palermo tradition.

The Saint was put on the same level of personal protection, through transmigration and transfiguration of the sacred Hindu protectors from evil, such as the figure of Durgai (avatar of Amman, with skull and roses, symbols shared with Saint Rosalia) or Ganesh (resident in the sacred mountain).

Hinduism is a religion that is inclined towards acceptance and contemplates a multitude of gods, while being aware of the presence of a single god.

There are two types of Tamils in Palermo: the first always turn their thoughts to the land of origin, and the second considers the city as its own; these two types are easily recognisable to the people who live here.

It is also necessary to take into great consideration the role of the school as a laboratory for social inclusion, since the long stabilization process of the Sri Lankan community, since the presence of Sri Lankans, whether Tamil or Sinhalese, is now functional to the host society.

On the other hand, the disaggregated data on the foreign population clearly highlight that the decision-making and demographic processes that favor the presence of immigrants’ children have existed for some time. These children, if born and educated in Italy, give rise to the so-called “second generation”. The second generation has fewer economic, linguistic, and socialisation problems; the presence of foreign students represents an opportunity for growth in the name of sharing values and respecting and appreciating cultural diversity.

The spiritual leader of the Sri Lankan Catholics in Palermo is Father Vimal Omi, who participates in the festive celebrations of Saint Rosalia every year.

The Tamil Catholics in the city of Palermo see Saint Rosalia as “a saint and a mother” who lives in the mountains.

In fact, the presence of the Tamil community in the pilgrimage that leads to the sacred figure “who keeps evil away” takes place not only in September each year, but on every Sunday of the year: this is the true rite or ritual of the Tamil community living in the city of Palermo.

The very fact that the sanctuary of Saint Rosalia is located high up in the air explicitly recalls the expression “looking up” and evokes in the Tamil community memories of their home territory of Sri Lanka.

The very action of wandering towards the sanctuary at the top of Mount Pellegrino, “walking on the cobbles barefoot”, with hands clasped in the sign of prayer and closure to the world, and in connection with the sacred to be encountered, denotes the mystical, private, personal, and intimate devotion of each pilgrim.

The slow pace, alone or in a group, represents a kind of direct link with the traditions of the first generation and the country of origin. The action of “acchianare”, climbing up, and “returning down” creates an identity with the place where one lives without dissociating it from the place from which one comes.

According to Burgio, “inside Tamil restaurants, and inside the few houses I have visited, one can admire a small altar where the image of Ganesh, the elephant-faced Hindu god, stands next to the Sacred Heart (the image of Jesus̀ Christ showing his own exposed and bleeding heart) or the image of Saint Rosalia (the patron saint of Palermo) lying with her crown of roses and holding a skull” (Burgio 2003, p. 7).

Recently, sociology has approached the subject of religious festivities and popular piety by creating an extension of the “vessel” of the “festive cycle” of Saint Rosalia in Palermo (Salerno 2013).

In her study on Mauritian communities in Palermo, anthropologist Viani highlights the temporal dimension of Tamil and Mauritian rituals in conjunction with Sicilian rites and traditions: “the first evident discrepancies concern the perception itself (unfortunately often distorted) of migration, the worsening disquiet on the part of public opinion combined however with a greater interest in the increasingly significant and stable presence of migrant groups visible in the territory through “ethnic” shops and restaurants, but also through rituals and processions that now represent a fixture and are becoming “traditionalised” alongside Sicilian festivals”. Furthermore, “there is a lot of interest and curiosity on the part of the local population (even if perhaps with an “exotic take”), but knowledge of the cults and ceremonial practices of migrants—and their meanings—still seems scarce: typical problems of the contemporary “multi-religious global city”, where the symbols of religions coexist, but do not enjoy mutual knowledge and are not included in a common cultural heritage”.

She also questions the “confusion” that can be created between different ethnic groups and their “religiosity”, analysing the case of the Mauritians, who are present as a large community in Palermo the 2.5% (844 of 34.143 foreigners in the province of Palermo), but in a minority compared to the Tamils: “the multiplicity of Hindu festivals and calendars reproduces, therefore, the complexity of the Mauritian and Hindu world in particular” (Viani 2011, p. 73). Moreover, “the absence of a suitable place for the needs of the community is a leitmotif of the interviews with migrants, for whom the search for a “place” for the community probably responds to the need to recreate that space, first of all physical, which was lost as a result of migration. In Palermo, the Mauritians do not have a real temple and were forced to rent a garage to use as a place of worship. The “temple” plays a fundamental role as social glue, highlighted by the fact that Mauritians’ participation in rituals is sometimes greater in the migratory context than in their place of origin”. The Tamil and Mauritian second and third generation Palermitans (the third generation of Tamils have fewer economic, linguistic, and socialization problems, moreover, the procreation among young people is greater than among the natives) come together, not only in their own communities, but also in the association derived from them. At the same time, however, the identity factor is not necessarily public, but private. The anthropologist Viani attempts to make sense of this: “the festivals considered most important by the groups in Palermo do not necessarily correspond to those listed among the public holidays in the national calendar of Mauritius. The Tamils, for example, are said to be more devoted to Mourouga, worshipped in the Cavadee rite. The ritual practices of this feast are, however, extremely complex and there are very few officiants who are able to perform it, especially outside their context of origin. In Sicily, it is only celebrated in Catania, where the largest Mauritian community in Italy resides. In order to have an anniversary that would represent them in the community they belong to, the Tamils of Palermo chose Govinden” (Viani 2011, p. 74).

In the seminar “Religious Rites and Territorial Transformations: the Case of Saint Rosalia in Palermo”, which took place on 18 April 2016 at the Antonio Pasqualino Museum in Palermo, I compared the rituality and plurality of religions that converge within the festive cycle of Saint Rosalia. In Palermo, specifically in the historic centre and particularly at the “Four-Corners” (the four corners, ndt) (the central convergence point between several religions present in the area, namely Piazza Villena, and the crossroads between Via Maqueda and Via Vittorio Emanuele) there are “ritual synchronies” that create an association of representations in which the cultural traditions of the various professions of faith that characterise the city centre are manifested. This is why the Archbishop’s curia created the “Day of Interreligious Dialogue”.

The theme of identity has recently been addressed by Piraino and Zambelli, who in their article “Saint Rosalia and Mamma Schiavona”, reconstruct the ritual interconnections that concern both the territory “the Mount” (as a spatial/temporal reference), and above all, forms of “spiritual interconnection” and “identity” that intertwine inside “pietas religiosa”. Indeed, according to scholars, “this devotion cannot be reduced to the categories of syncretism, absorption, and appropriation of worship, nor to a strategy of adaptation or an individual reworking; it would be better described as a specific porosity innate to Hindu religiosity, as a coherent and collective action of religious and social reworking, based on the permeability of Hinduism and Tamil Catholicism. Indeed, the religiosity of the Tamil people, irrespective of their actual religion, shows an exploratory dimension towards other religions. The boundaries between religions are more blurred than in Western theological and sociological categories” (Piraino and Zambelli 2015, p. 275).

In this case the religious communities present in Palermo are represented during the day of interreligious dialogue not only to participate in the dialogue, but to build solidarity between religions. This initiative was started in 2015 by the Catholic Church and has been fundamental in establishing a climate of mutual trust and the opportunity for creating a meaningful dialogue between different cultures. These meetings are based on a mutual determination to listen to each other. The physical presence of the religious leaders shows their willingness to collaborate for a common purpose—peace and mutual respect. It has become an open and respectful exchange of cultural views between groups and members of different communities.

The most important condition of this meeting is giving and receiving: it is fundamental that those who participate believe that there are truths and values on all sides which are equally important. The day of interreligious dialogue is dedicated to Saint Rosalie, as the Saint has become a beacon to whom those communities present turn to in times of need. Everyone prays in their own language, not only to their own God, but also in the name of Saint Rosalie.

The festival of Saint Rosalie has significant and symbolic elements that enable us to understand the importance of the sacred passage in different areas of the city. Over the years, different generations have made changes to how the festival is organised. As a consequence, the relationship that exists between a religious ceremony and the territory where it takes place can be found in the many factors that are rooted in the idea that devotion to the sacred leads to transformation and/or adaptation. Both the religious ceremony and the territory react according to a dynamic in which the changing of one necessarily involves changing the other.

To attempt to split (often introduced as an anthropological observation) between sacred time and profane time, or between the sacred and the profane festival celebrations, is fruitless.

4. From the Ethnographic Diary (Until 2020)

During my ethnographic research, before the pandemic, I noted the presence of the faithful and foreign pilgrims who traveled the cobbled road leading up the hairpin bends to the sanctuary on the slopes of Mount Pellegrino.

I should also mention the young scouts who gathered together in prayer to start the journey to the summit. Another group of devotees, standing in a clearing not far from the entrance, on the right side of the old road, waited for all the members of the group to arrive before starting to “acchianare”.

Around 8 p.m., devotees with the somatic features that characterise the Tamil community began to arrive. I didn’t ask where they came from. They could have even been Sinhalese. They joined those already present (men, women, and children) and set out on their journey with wax candles, lighting them one by one, starting with the first flame that lit the next. They formed a semicircle to light the votive candles and then, in rows of three, they formed a procession.

The Hindu Tamil community of Palermo prays to Saint Rosalia. This is not “religious syncretism”, but a real transfer: the mother of the mountain in Sri Lanka also inhabits Mount Pellegrino, just as she inhabits Mount Kataragama in Sri Lanka. Ritual pilgrimages must be made to the mountain for nine consecutive days, and these pilgrimages are paved with suffering and doubts, relationship difficulties, desires, integration, and social disintegration. The prayers to Saint Rosalia are written down and delivered to the sanctuary on the mountain, and as a whole, they are a testimony that is sometimes distressing, sometimes funny, but always moving and full of feelings, unmediated and expressed confidentially in a language (Tamil), which should not be read by foreign eyes.

The Tamil devotion to Saint Rosalie began with a miracle performed on a Tamil woman who climbed up to the shrine on her knees, crying for her little girl who was in a coma. After her mother’s plea, the girl woke up and is still alive today. Another blessing was granted to a childless couple who now have three children. Among the Tamil people, there are girls who bear the name of Rosalia as a sign of gratitude, and among the votive gifts are photos of Tamil children and prayers written in Tamil.

It may be difficult to understand how a Hindu community could pray to the Santuzza (Saint Rosalia in Sicilian dialect, ndt) who saved Palermo from the plague in 1624, but if one enters into the spirit of Hinduism, an ethnically based religion that has gradually incorporated different cults, their devotion does not seem so difficult to understand.

Hinduism is easily open to other religious manifestations. Deeply diversified according to the different regions and cultures in which it has developed, it presents a religious landscape that is both welcoming and sensitive to other cults. The Tamils seek a relationship with the natural elements and to harness this energy. Thus, also on Mount Pellegrino at the sanctuary of Saint Rosalia, they are able to perceive a cosmic force. The sanctuary represents a place of union with their homeland, the space in which they live out their hope for peace, for liberation from war and death, their deepest feelings for their loved ones, and their desire to reunite their dispersed families. The Santuzza welcomes them and listens to them, and their prayers are renewed as they wait for a miracle.

The Tamil devotees are becoming more numerous: there are about four thousand Hindu Indian Tamils from Sri Lanka for whom the Saint seems to grant wishes and answer prayers. The president of the Italian Tamil community in Palermo, Mr. Metha, designated the sanctuary of Saint Rosalia as a point of reference that brings back memories of the temples of Sri Lanka because of its geographical position and location on the highest peak of Mount Pellegrino.

The Tamils who have lived in Palermo since the 1980s do not have a place to practise their religion and celebrate their rites, so the sanctuary on Mount Pellegrino overlooking the sea has become their temple and Rosalia, their Saint.

Every Sunday throughout the year, at the crack of dawn, Tamil families in their traditional dress meet at the foot of the mountain to climb up together, immersed in the festive atmosphere of those going up to reach the Saint.

They walk lightly, in religious silence, barefoot. There are also numerous children with large dark eyes. When they reach the foot of the sanctuary of Mount Pellegrino, their heads bowed, they continue on their knees along the steps leading to the cave; slowly, they light a candle in the open area of the sacred spot designated for votive candles, enter the cave, which has been transformed into a chapel, and pray in front of the altar.

For the Tamil community, the natural elements of water, air, earth, and fire are manifestations of the divine on earth. Saint Rosalia is also a manifestation of the divine on earth for the Tamil community, who see her as a personification of cosmic energy. Of the foreigners who live in Palermo, the Tamils have a special story: they are refugees, and after the granting of political asylum, they have tried to rebuild, little by little, a life that is dignified and peaceful. They meet on the premises of a school near Via Dante, where in the afternoons, volunteers spend time teaching children aged between 3 and 13 about their traditions, language, and culture.

Among the events that involve all the Tamil people, the most important is the festival of 27 November, which celebrates the anniversary of Shangar’s death. This is a long celebration with traditional dances, songs, and shows—very similar to our Christmas celebrations.

The presence of new social actors and a new culture in the city was seen, for example, with the inclusion of the sacred elephant Shiva in the procession preceding the traditional float in honour of the Saint on the night of the Feast di Saint Rosalia on 14 July 2012.

The cards on which the requests for blessings are written are taken from a work entitled La diaspora Tamil a Palermo, by G. D’Alia and G. Fiume (Maniscalco 1998, p. 65), which, through the translation by Nancy Triolo, represents a sort of breach of the wall of linguistic mystery, opening a window into an immigrant population that has turned to Saint Rosalia to request spiritual support.

In the notes left at the sanctuary, one can read about suffering caused by love, lack of social acceptance, and ethnic difficulties; they are honest confessions because the writer does not expect them to be read by anyone other than the “Mother of the Mountain”. They contain all the pain, humanity, and passion of someone who lives life in a difficult land, but who has come to terms with this fact because it is where he must live.

5. Here Are Some Requests

“Dear Saint Rosalia, I would like peace to come to our country forever. There is no one here with me. Then I would like a job and bless my children and my wife”.

“Mother of the Mountain, I come to you, bow my head before you and fall at your feet asking you to solve my problems. I do not know if my relatives are well. In our country. Motherless girls are suffering. Can I ask you something? Why aren’t you a mother? Excuse me for asking. Answer my questions. Now I purify my heart and hope not to soil it again”.

“Mother Saint Rosalia, we have no children and we are desperate. We have lost hope, give us a way to have children”.

“Mother of the Mountain, this woman and I love each other, please let us get married without the problems that our family gives us. Mother lead my beloved woman to me. Thank you. If you do me this favour, I promise to give food to the poor”.

On the 4 September 2013, the newspaper Giornale di Sicilia, in the chronicle of Palermo, wrote: “Mount Pellegrino—It is the traditional barefoot climb and not the shrine that attracts hundreds of people every year. The Acchianata between faith and folklore—Lining up with a lit candle not only to ask for blessings from the patron saint but also to seal unions”.

The climb to the place where Rosalia Sinibaldi found refuge lasted about an hour. The event attracted experts and onlookers from all over Italy:

A lit candle in their hand, the boiling wax falling on the stones that become increasingly smooth and slippery, the light illuminating the steep and long uphill path. Some people wear white socks, who knows why. Some, on the other hand, have already taken them off; in the past few years they have seen someone doing it and now they are doing it. Perhaps they have a good reason for doing so. Some people are even carrying their babies in swaddling clothes in their arms, in prams, or on their shoulders, a “piggyback”. Or they give them their hand to make sure they don’t fall, leading them up to the top of the mountain. Different faces, different looks, different moods. People for one night united by a journey of faith and devotion that leads them to undertake that steep and tiring climb together, kilometres and kilometres, about an hour’s walk to reach the place where the young Rosalia Sinibaldi found a silent refuge: Mount Pellegrino. A place that has been sacred ever since, in memory of Rosalia, who later became a saint and then patron saint of the city for having saved Palermo from the plague in 1624 […]. A tradition that is repeated every year on the night of the 4 September, the date on which Rosalia was found dead by pilgrims inside the mountain. Today, it is said that a sanctuary has been erected here in her memory. Many people come to the shrine every year to ask for a “blessing” from the Saint to cure a family member of a severe illness, to bring serenity to the family for a child who is late in arriving, or even for a job that cannot be found. In fact, the tradition of silver votive offerings brought by the faithful to the sanctuary as a sign of thanksgiving, depicting the blessing received, is an ancient one. “I haven’t brought a votive offering, but for three years now I have been walking up this slope on the night of the 4th”, says I.M., who lives in Castellammare del Golfo. “I asked Santuzza for her blessing when I was in hospital and had to undergo a difficult bowel operation and she helped me. I will come here every year as long as I have the strength”. But there are also those who see this day as a real day of celebration to crown and seal their dream of love […] “The Saint blessed us with love, she brought us together”, they say happily, “and for three years now we have been doing this journey together every year as a token of our gratitude. If one day we ever get married, we will certainly think of the sanctuary”. The first barefoot climb by P. L. He prefers not to reveal the blessing he is about to ask for, it is a secret: “I am sure she will listen to me, I am sure”” he says with conviction […] Shortly before embarking on the climb he also says: “It will be tiring but for the Santuzza, I’m willing to do this and more”. At his side was R.P., also barefoot, hand in hand with her two small children. “They are my blessings”, she said. “Eight years ago, I went barefoot on this journey because the babies were late in arriving and I couldn’t get pregnant. On the morning of the fifth, I took a pregnancy test and it was positive. Now they are with me”.

According to Lanternari, we must refer to folklore from an anthropological-cultural perspective, as “the set of traditions of pre-bourgeois origin, which as such imply any custom—attitude, behaviour, lifestyle, cultural product linked to a culture prior to the bourgeois classes—bringing it back to a peasant class (Lanternari 1983, p. 86). Alberto M. Cirese describes folklore not only as “a trace of a cultural product of a time that has already passed” (Cirese 1973, p. 24), but also as a component of behaviour and attitude in the present.

Burgio, on the other hand, based on a 2003 study of the Tamil community, argues that juxtaposing Saint Rosalia with Vishnu is irreligious; for a Hindu it is absolutely natural.

While this has historically influenced the conversion of many Tamils to Catholicism, it also gives precise connotations to this conversion. Hindus have no difficulty in coming to terms with Catholic spirituality; it is also true that Tamil Catholics do not feel that the symbols, deities and spirituality of Hinduism, which they share on a cultural-historical and folkloric level, are antagonistic to their Catholic faith. This naturally leads to a great tolerance towards the religions of others, which is not, as it might seem, indifference, but a profound awareness of non-opposition. What has been said accounts for the religious reasons S. Rosalia and Shiva share the same altar but does not explain why it actually occurred (Burgio 2003, p. 10).

6. Methodology

The techniques of qualitative analysis are not particularly distinguishable from each other from a conceptual and terminological point of view: “for example, the terms ethnographic research, field research, community studies, participant observation, and naturalistic research are all more or less synonymous; just as in-depth interviews, free interviews, unstructured interviews, clinical interviews, oral history, life stories, and a biographical approach, indicate survey techniques that sometimes differ from each other only slightly” (Corbetta 1999, p. 365).

The detection techniques of qualitative research can be grouped into four main categories: direct observation, in-depth interviews, document analysis, and computer-assisted content analysis (as in the NVivo software). The actions related to the first three categories are those of observing, questioning and reading.

The action of the participant observer is rather selective: “they cannot observe everything. Participant observation cannot be an all-encompassing snapshot of the whole of reality; on the contrary, some social objects must be brought into focus, others remain in the background, and still others remain completely excluded from the researcher’s lens” (Corbetta 1999, p. 380).

In particular, the use of documents means analysing a certain social reality starting from material, in written form, from individuals in that society, such as in autobiographical accounts, letters, and documents kept at institutions, for example, in minutes and records.

Community studies are those most affected by the ethnographic model. They are researches conducted on small social units that involve the physical transfer of the researcher into the social context analysed, in a specific territory in which to live for a certain period of time.

The social context is of substantial importance, as the researcher is engaged in giving a detailed account of their investigations, observing and reporting in an adequate and structured manner the essential elements of the social actions examined.

An analysis of the social context is not to be given with evaluative descriptions. Instead, it is a question of describing the human environment, i.e., the people who frequent the analysed area, the way they dress, the purpose of their movements, and their customs and habits.

The possibility of studying the dynamics of a specific public meeting is given, in the first place, by a description of the physical and human environment, for example, the size of the place, the number of visible characteristics of the people present, and their typology (in our case the Tamil community or the leaders of the other religions present in the Palermo area). It is also possible to identify the social classes involved by observing the clothing of the religious communities present.

The study of a formal organisation can be performed by making specific choices, i.e., deciding, for example, whether to observe a religion, particularly in our case the Tamil religion in relation to the Catholic context of reception. We can therefore examine the interaction of all the social and institutional actors within a process of shared solidarity, cultural socialisation, peaceful coexistence, and mutual aid.

The communication channels used also have characteristics that should not be underestimated, namely formal and official interactions. Informal interaction involves a myriad of different cases, so it is not easy to provide specific operational rules. For instance, at the beginning, one may notice a large influx of institutional and non-institutional social actors, with hundreds of acts that seem to be devotional, but in fact, are not. Moreover, the main feature is the traditional use of clothing used on a public holiday (bright colours), as opposed to the usual pilgrimage attire (muted and dark). These actions seem to be regulated by time, almost as if it were a dance or simply a ritual.

Observation means detecting an ordinary behaviour by distinguishing it from a non-ordinary one, within a time frame that seems to be constructed by a series of mechanical acts of which the social actor is largely unaware. In fact, capturing people’s interactions is not easy because the very choice of the place in which to observe them is an important process in order to focus on meaningful relationships and interactions.

The characteristics of the social actors have specific parameters that can be focused on within the analysed phenomenon. The interpretation of other social actors is not immediate: the organisation of the environment, clothes, and gestures in general help to provide an overall view of the analysed phenomenon.

Participating and observing also implies asking oneself what the motivation is for choosing a certain social actor, a certain moment, or a certain place rather than another to observe. Basically, the questions are those typical of qualitative methodology, according to the following specifications.

1—When: as close as possible to the phenomenon under observation; for example, finding oneself inside the Archbishop’s Palace and waiting for the civil and religious institutional actors to make their entrance; or waiting and observing the ordinary movements during statements made by representatives of other religions. Observation is always complicated, but it can be resumed and reviewed not only through written impressions, but also through recorded photos and videos. Being close means being unfailingly present, trying to capture the behaviour, the gesture, the word, the symbolic act that will perhaps be the main key to interpretation.

2—What: the description of events that are divided into specific and detailed moments. The interpretation is not only given by an emotional reaction, but also by a theoretical reflection to be associated with the observed phenomenon. In this case, the sharing of the messages of “hope”, “solidarity”, and “the sharing of bread” is the focus of a whole series of observations made at a specific time and not in an ordinary place. The analysis is also the reconstruction of the dynamics that took place during the observation of the phenomenon.

3—How: the advantages generated by audio-visual recording tools offer more support than traditional methods. For example, through a video camera, it is possible to observe, even in slow motion, the gestures and postures of the social actors, i.e., the devotees during the celebrations. The description of participant observation takes on the character of a scientific product based on the account of what is seen and heard. Above all, it is a description enriched with meanings and interpretations in a precise cultural and historical frame. With the NVivo software, it is possible to manage ethnographic observations through the use of photos and videos, and to insert qualitative data such as, in our case, the documentation of all the sermons.

The use of software for qualitative analysis was made available thanks to researchers who believed in the possibility of the electronic processing of qualitative information through “NVivo […] capable of responding to the various needs of the qualitative researcher: importing texts, coding by means of node concepts, managing memos together with attributes related to subjects, creating intersection matrices and different matrices, analysing texts by means of the operators—and, or, not, less—conducting proximity searches and creating occurrence and inclusion matrices, graphically visualising theory building from factual feedback” (Cipriani 2008, p. 187).

From my ethnographic diary: “In the hall of the archbishop’s palace, I can see some flyers on the chairs that show the importance of this day. I cannot help but notice the various colours of the people in costumes. There are still only a few people, but the room is filling up slowly. There are children who are trying to sing a few songs and their teacher is encouraging them. On the right side of the room there is a group of dancers from Sri Lanka. Slowly more representatives of other religions begin to arrive: the rabbi stops to chat with a few people. The priest browses the brochures on chairs and sits up on a bench not far from the centre of the head table. Shortly after entering the imam, he has a friendly attitude and heads directly to the event organizer. Many people are foreign; others are from the old Palermo. Everyone takes their place, almost at random, but the authorities are stationed in the front row. The presence of the Mayor of Palermo is just as important as the presence of other religious authorities. It is the city itself that welcomes all religions within its territory. The civil power and the religious powers. The mayor: “This morning meeting with representatives of all faiths, promoted by Archbishop Don Corrado Lorefice, who, on the occasion of the Feast, has opened the doors to everyone, Christians, Jews, Muslim imams and other religious denominations, for a meeting of fraternal joy. The remembrance of the lives of the saints, teachers and prophets is a way to ask us about our day, our inner man and the relationship that exists between the inner man and his brother in faith. I wish Palermo years and centuries of strength and joy, found in the ability to live together with the diversity of our neighbour and of his brother, to feel and to be Christians, but also Hindus, Jews, Muslims. To be Italians and Sicilians, but also Africans, and Asians. Starting the teaching of the Jubilee of Mercy year, which asks not only the ability to listen to others, but the ability put ourselves in the shoes of the other”.

Cardinal Corrado Lorefice opened the doors of the archbishop’s palace for a meeting of “fraternity” with representatives of other religions—imams, rabbis, pastors, priests, spiritual guides—and the presence of the state institution.

“Dear Friends, Dear Friends, I am happy that you are here today, to share the joy of this eve of the Feast—a first for me—in which our entire City is plays a part. We hear—we hear it in the air—that ours is not a diplomatic meeting, an exchange of courtesies between so-called “authorities”. For my part, therefore, I welcome you here as a man called to this land Palermo, among these people, and next to it, to witness and announce the Gospel of Jesus. And the deeper meaning of this Gospel is the acceptance of all, open to all, peace with all” (Cardinal Corrado Lorefice).

Dialogue, the exchange of words—and before that, sounds, gestures, emotions, visual expressions, contacts—all this constitutes the human being.

Every social actor is built as a house of words he has learned from someone else, from the people closest to him to those furthest away; he listens to the voices in books, education, work, religious communities, or political affiliations. Brick by brick, stone by stone, word by word, the person is built as a house. Education for dialogue should not be thought of as a description of views, but as growth, maturation, and exchange—a form of education open to change, transformation, and the continuous learning of reciprocity. Dialogue is a prerequisite for the growth of the human condition, and is also the perfect tool to end any conflict.

Human conflict, each intimate aspiration to the depth of existence, every authentic look at the past is my fellow, and is our companion of the road, because we are all together, one beside the other, in the same boat of life, watched and guarded according to the measure of makrothumìa, the big heart. Today, the biggest issue for all women and men who practice any faith: make of their experience not separation, opposition, or a cause for war, but a push to be together, to seek peace, to try to make the world more welcoming to all.

Participant observation (in the field—qualitative method with NVivo), the connection between “body and dialogue” showed the testimony of the other religious faiths and the ethnic dance of the Mauritian Hindu community. The goal is not to give up their faith, but to create a “convenient” time (through the sharing of food) in which the different believers meet and try to get to know each other better, to appreciate the positive values and recognise them in others. Common values can encourage dialogue and collaboration.

Thanks to the NVivo software, it is possible to examine the distinct moments that mark the day of the community meeting and analyse the contents of the written messages, as well as the progress of the pilgrimage, through images.

The creation of nodes follows a methodological criterion aimed at identifying the sociological conceptual categories par excellence, so as to be able to scientifically read the documents with the help of the nodes (or sensitising concepts) identified, guiding the research towards the construction of a theory.

In this case, the following nodes emerged (20 in all) (Table 1):

Table 1.

NVivo made it possible to analyse terminological frequencies by means of procedures called Query and Word Frequency.

The data obtained show, for example, that in 2018, there were 20 nodes and that the word with the highest frequency was “God”, with 3.57% of the first 100 words, for a total of 1327 times, while the last two were “fight” and “oblivion” with 0.17% and 0.12%.

The resulting data for 2019 also showed the presence of 20 nodes and that the word with the highest frequency was “community”, with 5.03% of the first 100 words, for a total of 273 times, while “world” and “expectation” stood at 1.18% and 1.16%, respectively.

The 2020 data obtained through the frequency variable highlights the words “pandemic” and “prayer” in a constant and strongly symbolic way (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Word Cloud.

The data found the word “gospel” with 0.21%, after the 100 words not inside at the cloud, is present in the text count 136 times, and the word “procession”, with 0.28% count, 153 times.

This “institutionality” of interreligious dialogue in the territory of Palermo was established in 2016 by Archbishop Corrado Lorefice (from the Christian-Catholic religion) who opened a window to the world of other religions present in the territory itself, thus creating the possibility of study and reflection on the importance of the terminologies of “solidarity”, “sharing”, “respect for the environment”, etc. It is not merely a question of encouraging religious leaders to act as instruments of peace and peacemaking, but above all, a question of considering the concept of dialogue combined with the concept of peace as “necessary”. Therefore, it is no longer a question of terminology, but above all, of awareness that dialogue builds bridges of solidarity to break down the walls of indifference.

Furthermore, from my ethnographic diary, one note is very important because it is very difficult to talk with the other persons during the day of interreligious dialogue. On this day, dedicated completely to the dialogue, the participants talk about their values and the importance of the solidarity inside at the community.

In this case, the words inside the cloud express everything found in the messages read during the celebration. Every religious representative expounds his own ideas about the dialogue established among all the communities within the territory.

During the exchange of the messages, I note that the presence of the female gender is made superior to the male gender. Saint Rosalie is a central beat; the fulcrum, of a dialogue. At the beginning of this dialogue is her name, Rosalia. Everything revolves around her, and the participants are aware of her “presence”.

Many years have passed since that research, and the creation of an interreligious day for all religions has laid the foundation for fraternal cooperation and structured identity inclusion in the area. Moreover, the community reality is quite different from that of an individual reality. This reasoning is applicable to almost all religions.

In the first article “Solidarity Actions Based on Religious Plurality”, the authors highlight that: “The argument of religion as a source of solidarity is well documented in studies that analyze expressions of solidarity in current situations. And quote the author Gustafson beyond the impact of religion on solidarity towards others regardless of their religious denomination, scientific literature also acknowledges the positive impacts of interreligious dialogue” (Gustafson 2020). Another author of the first article, Sen (2019), argues that: “the spaces of solidarity that are created between women of different religious traditions. Despite their religious differences, the author states that they create bonds of solidarity and mutual aid through dialogue and respect. Consequently, these women acquire an interreligious perspective when they discuss fundamental aspects of their existence, such as gender or social class”. The scholar Miles-Tribble (2020) reflects on the strength of interreligious discourse in social transformation, thanks to the values of justice and shared ethical actions to reduce existing social inequalities.

The scholar Berger claims that: “Interreligious dialogue provides answers to the difficulties posed by a narrow concept of the neutrality of public space as homogenization or assimilation” (Berger 2014).

In this article, the scholars highlight both cases, beyond the fact that there are people of different religions, there are conditions of equal dialogue between them, based on claims of validity (Habermas 1987).

Furthermore, the authors claim that this dialogue has promoted bonds of friendship and complicity, contributing to the management of religious diversity in the public sphere. Beyond mutual understanding and coexistence, these solidarity initiatives have achieved other social impacts, such as language learning.

The sociologist Habermas and pope emeritus Benedict XVI believe that: “the understanding of religious plurality and interreligious dialogue as a driver of solidarity has implications for social policies and the management of civil society organizations” (Habermas and Ratzinger 2006).

The author and scholar Gustafson defines the dialogue as “a conversation on a common subject between [and among] two or more persons with differing views, the primary purpose of which is for each participant to learn from each other so that s/he can change and grow”.

The scholar Panikkar proposes an intrareligious dialogue to refer to the conversation that takes place within oneself in a move towards deepening his or her faith in light of encounters with persons of other religious traditions.

The scholar Grung recognizes that this interreligious dialogue opens up the possibility for the dialogue, not only to change the broader society, but also to create new interpretations of the religious traditions themselves and possibly transform them.

In the article “Aesthetics as Shared Interfaith Space between Christianity and Islam”, the authors question the particularities of the two monotheistic religions: “Due to its immediate message, religious aesthetics is prone to various kinds of instrumentations in the contemporary world. In this context, the aesthetic fundamentals shared by different religious traditions or scriptures must be rediscovered. The focus of this article was the interreligious potentialities of religious aesthetics, in the case of (Eastern) Christianity and Islam, conceived as a resonance chamber for similar sensibilities in the two religions. Furthermore, the Christian understanding of God becoming human engages various forms of visibility both in the representation of God and in religious practice. In contrast, Islam is marked from its very beginnings by inflexible aniconism in sacral space, a reliance on word and geometry. Despite these, in both religions, imagery has an exceptional place in arming and confirming specific religious truths”.

In the article, “The Anti-Mafia Movement as Religion? The Pilgrimage to Falcone’s Tree, the author Puccio”,compares the pilgrimage of Santa Rosalia with the manifestation in memory of Judge Giovanni Falcone; in my opinion, it cannot be defined as a pilgrimage. It is not a ritual, it is not a devotion, it is not a votive altar. The author shared her idea of pilgrimage with that of the “tree” symbol. The sacral dimension of Santa Rosalia cannot be compared to the day of 23 May. I believe that the appropriate term for the event is not “pilgrimage to the Falcone tree”, but rather a symbol of a memory. The author and scholar Puccio argues that the pilgrimage is becoming less and less an exclusively Catholic phenomenon, and that more and more interreligious and other forms of pilgrimage can be distinguished. Shrines and pilgrimages have characteristics that enable them to generate, stimulate, or revitalize religious devotion and religious identity. In the reality of this city, the perceptions of devotion to Saint Rosalia are very different. It is not comparable.

In the last article “Beyond Interreligious Dialogue: Oral-Based Interreligious Engagements in Indonesia”, the interreligious dialogue is a way to understand other religions and a vehicle for bringing religious followers to peaceful interactions. Openness to learning from other religious teaching creates avenues for mutual understandings and social engagement with different traditions.

According to the scholar Swidler, the primary aim of interreligious dialogue is for the dialogue partners to learn something about the ultimate meaning of life that they did not know solely from their religious perspective. Therefore, interreligious dialogue requires a social-scientific study of religion “to understand the other” (Lattu 2019, p. 6).

Another scholar, Ayoub, believes that dialogue has to go beyond mutual recognition and acceptance to create a sense and reality of good neighbours. Indeed, the author claims, “Muslims and Christians must accept each other as friends and partners in the quest for social and political justice, theological harmony and spiritual progress on the way to God, who is the ultimate goal” (Lattu 2019, p. 71). Furthermore, the scholar Lattu claims that “interreligious dialogue has touched on the problem of feelings in human relationships” (Lattu 2019, p. 72).

7. Conclusions

Compared to usual times, the festive season stands as a dialectical completion, as being rather than doing and, in religious festivals, as the sacred compared to the profane. The division, often introduced in anthropological analysis, between the sacred time and the profane time, between sacred festivals and profane festivals, seems all the more difficult to apply when one is faced with the countless contaminations and transformations that have taken place over the years and centuries.

According to traditionalists, after more than three centuries, it would be a crime to interrupt a historical and cultural continuity that has catalysed the religious enthusiasm of the majority of the people of Palermo, year after year.

The process of secularisation does not legitimise the thesis that post-modern society is moving towards the cancellation of festivities by standardising the days and hours; the climate of emotional involvement and collective identification during the days of the festival of Saint Rosalia in July and September is enough to disprove this.

The cycle of festivities has its own role, incorporating elements of conservation and transformation. The use of symbolic language in the rituals that make up Palermo’s festival structure makes it clear that the existential cycle referred to can be traced back to a much broader framework in which the figure of Saint Rosalia acts as a simple vessel.

There remains, however, the dimension of the permanent reorganisation of religious sensibility and therefore, of reaction to transformation. The specialisations of the festival, both civil (feast) and religious (procession) are followed by the neighbourhood festivals and the alley altars; a veritable operation of popular recovery of a festival whose dimensions are now so big that it can no longer organised using only volunteers.

The use of the NVivo software helps us to understand how from 2017 to 2019, during the days when the religious communities of the area met, the line linking the words “God”, “Prayer”, and “Community” highlights “Faith”, and the consequent capacity of the cult to be potentially legitimised to authorise any community to retrieve its own festival and rebuild it on its own territory.

The frequency of certain words justifies and encourages the implementation of a dialogue and the development of social inclusion and contributes to maintaining a stable balance between political and religious institutions operating in the territory. At the same time, contemporary popular religion maintains some elements of both pre-modern and modern piety, guaranteeing a certain independence from institutional religion due to a “creative energy” (Isambert 1977, p. 179).

In this case, the possibility of being able to observe, analyze, and research results that lead to responses of sharing of the faith help studies open more avenues of research hypotheses and scientific sharing. The data collected can be used to show how necessary the value of sharing and comparison is in social research. Being able to of attending dialogue meetings for a long time has allowed me to tiptoe into the beliefs of others and thus discover the tangible solidarity and the sense of shared humanity.

It is also necessary that we study different religious beliefs and develop a high esteem and respect for them. What people seek anywhere in the world is the experience of the Divine, a true God experience which they accept in any person, whatever religion he/she belongs to. It is necessary that we step into their lives with availability, whenever possible, to exchange the hospitality and then remain united with them through all their joys and sorrows. This is the dialogue of life we can always have, with the reciprocity of ideas and values.

Ultimately, popular piety is used as a tool for collective memory through the prominence of body language and symbolism. Moreover, it is a means of affirmation in opposition to official religiosity/religion. However, while being a means of preserving collective memory, popular religiosity, the bearer of ancient traditions, also becomes an important source for religious innovations that reflect the changes in society.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

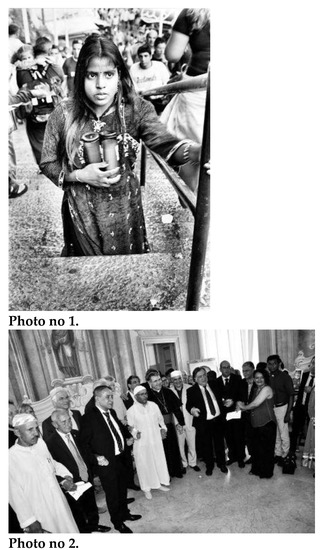

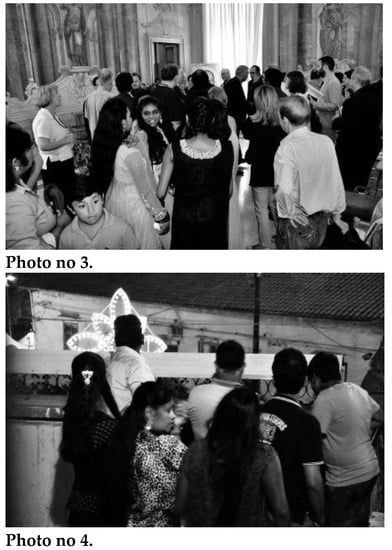

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Photographic Appendix. Source: The photos were taken by the author in collaboration with Antonio Ferrante, who has authorised their publication.

References

- Berger, Peter. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity: Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Burgio, Giuseppe. 2003. Tra Ganesh e S. Rosalia, la comunità dei Tamil a Palermo. In F. Cultrera (a cura di), Religione popolare in Sicilia. Palermo: Provincia Regionale di Palermo, pp. 119–41. [Google Scholar]

- Burgio, Giuseppe. 2016. When Interculturality faces a Diaspora. The Transnational Tamil Identity. Encyclopaideia 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, Roberto. 2008. L’analisi Qualitativa: Teorie, Metodi, Applicazioni. Roma: Armando. [Google Scholar]

- Cirese, Alberto. 1973. Cultura Egemonica e Cultura Subalterna. Palermo: Palumbo. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta, Piergiorgio. 1999. Metodologia e Tecniche Della Ricerca Sociale. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, Hans. 2020. Defining the Academic Field of Interreligious Studies. Interreligious Studies and Intercultural Theology 4: 131–54. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jurgen. 1987. Teoría de la Accion Comunicativa. Vol.I: Racionalidad de la Accion y Racionalizacion Social. Vol. II: Critica de la Razon Funcionalista. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Júrgen, and Joseph Ratzinger. 2006. Dialéctica de la Secularización. Sobre la razón y la Religión. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Isambert, François. 1977. Religion populaire, sociologie, histoire et folklore. Archives des Sciences Sociales des Religions 42: 161–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanternari, Vittorio. 1983. Crisi e Ricerca di Identità. Folklore e Dinamica Culturale. Napoli: Liguori. [Google Scholar]

- Lattu, Izak Y. M. 2019. Beyond Interreligious Dialogue: Oral-Based Interreligious Engagements in Indonesia. In Volume 10: Interreligious Dialogue. Leiden: Brill, pp. 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, Basile G. 1998. “La Madre Della Montagna” in “Santa Rosalia” Numero Monografico in Nuove Effemeridi ed. Guida slr Palermo. Available online: https://www.maremagnum.com/libri-antichi/nuove-effemeridi-anno-xi-n-42-1998-ii/162180784 (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Miles-Tribble, Valerie. 2020. Change agent teaching for interreligious collaboration in Black Lives Matter times. Teaching Theology & Religion 23: 140–50. [Google Scholar]

- Piraino, Francesco, and Laura Zambelli. 2015. Santa Rosalia and Mamma Schiavona: Popular Worship between Religiosity and Identity. Critical Research on Religion 3: 266–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, Rossana. 2013. La devozione a Saint Rosalia attraverso il pellegrinaggio e l’“incubatio”:“l’acchianata”. In La Religione Popolare Nella Società Post-Secolare Nuovi Approcci Teorici e Nuovi Campi di Ricerca. Edited by Luigi Berzano, Alessandro Castegnaro and Enzo Pace. Padova: Edizioni Messaggero, pp. 261–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 2019. Gods, gurus, prophets and the poor: Exploring informal, interfaith exchanges among working class female workers in an Indian City. Religions 10: 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viani, Giulia. 2011. Comunità confuse. I Mauriziani a Palermo tra induismo e induismi. Antrocom, Antropologia Culturale 7: 69–83. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).