1. Introduction

In August 2014, The School of Sufi Teaching set out to create a meeting place in London, UK, for the students of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Sufi Order under Shaykh Hamid Hasan in New Delhi, India.

1 This would be the transformation of an existing building into the first purpose-designed centre outside of India that would reflect and support specific rituals and practices performed by Sufi aspirants with the aim to attain nearness to God. The design aimed to reflect the qualities of Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual practices by cultivating a contemplative state that supported Sufi aspirants to turn away from the world and to encourage a gradual movement of consciousness towards the realm of the inner self and to what is beyond the self. It was important for the project to also navigate the challenges associated with the site’s commercial, urban environment and wider non-Muslim community. The new centre, the School of Sufi Teaching in London, successfully opened to the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi community in the presence of Shaykh Hamid Hasan on February 2020. Similarly to classic Islamic religious architecture, the Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī Centre brings together a space for spiritual practice used primarily by members of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Order (male and female) attending various weekly spiritual gatherings and annual retreats and includes a multifunctional community space for more public use.

The practice-as-research project explored the possibility of drawing on the wisdom of the past in smaller-scale, contemporary projects, whilst navigating the challenges that arose with reclaiming traditional forms in contemporary contexts. It addressed the contrast between transformative experiences of classic Islamic sacred architecture, defined as historic masterpieces that modelled the use of traditional Islamic aesthetic philosophy, with contemporary examples, where the transformative quality has often been lost. The research methodology underpinning the study of historic buildings combined analytic and synthetic, conventional and unconventional modes of research to reveal, apply and evaluate key principles for the design of Islamic sacred space, including a literature review, academic/historical research, textual analysis and field research including phenomenological analyses of Islamic sacred space. Case studies were selected according to personal transformative experiences, in some cases occurring years earlier, which were reviewed during subsequent visits as per the spiral process of Action Research. The process of discerning underlying principles utilised Grounded Theory to compare analyses of historic buildings and to generate theory, which was tested and evaluated in practice in relation to the Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī Centre. The Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project also explored how Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi teachings, spiritual practices and shared experiences of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi community, as part of a wider Islamic tradition, informed the design of a contemporary Islamic sacred space and recognised the challenges that this approach presented in synthesising different types of knowledge. An ontological hermeneutic approach was developed that examined the relationship between theory, built form, creative practice and spiritual practice. By going beyond the study of physical form, metaphysical and ontological dimensions became integrated into the understanding and design of Islamic sacred space. Qualitative and experiential aspects of Islamic sacred space were expressed in terms of spatial sensibility and were considered fundamental for a more integrated view of the subject. Central to this approach was the belief that studying design cannot be separated from practising design. Similarly, design practice cannot be separated from a reflection on design processes (

Herr 2015, Vol. 1, No. 1). The project recognised the importance of both research and design to architectural practice and drew on studies of design as research which explored themes such as the synergy of design and research practice; the individual and collective knowledge that can be gained from design practice; and the creative and intuitive processes underlying design practice which continuously challenge research conventions (

Schön 1983, p. 49;

Downton 2003, p. 110;

Fulton Suri 2008, pp. 53–57;

Rodgers and Yee 2016, p. 17). The subjective nature of spiritual experience and creative practice was recognised. Studies suggested that by consistently reflecting on the process, a researcher may evaluate whether subjective values facilitate or impede objectivity and systematically replace any distorting values. In this manner, objectivity was observed to rely on active and sophisticated subjective processes (

Ratner 2002, pp. 1–5). The impressionism common to qualitative research was, therefore, avoided by consistently evaluating meaning, experiences and theories in relation to the principles emerging from the research as a whole.

Discourse on contemporary Islamic sacred architecture in the non-Muslim West has identified a lack of architectural coherence that reflects complex issues of Muslim identity and visibility (

Nasser 2003, pp. 7–21;

Akšamija 2009, pp. 129–39;

Göle 2011, pp. 383–92;

Roose 2012, pp. 280–307;

Avcioğlu 2014, pp. 57–68). Islamic sacred architecture has been viewed as a feature of ‘immigrant Islam’ that seeks to reconcile tradition and modernity in a foreign context (

Kahera et al. 2009, p. viii & p. 17), resulting in what have been called ‘new geographies of cultural displacement’ (

Nasser 2003, p. 7). These issues are considered a legacy of globalisation and post-colonialism, which have marginalised and eroded Muslim culture (

Ozkan 2002, pp. 85–87;

Akkach 2005, p. xxii;

Van Toorn 2009, pp. 1–6). The creation of Islamic sacred spaces in the non-Muslim West is largely community driven, organised by elected committees and trustees who are often reluctant to stray from conventional forms and functions in order to ensure the satisfaction of their congregations and to maintain their positions (

Saleem 2018, p. 3). In contrast, the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project, although community-driven and organised by a management committee and group of trustees, prioritised the experiential qualities of the architecture as a support for spiritual practice. Such a priority was also evidenced by other examples of contemporary Islamic sacred architecture in Britain that reflected the transformative quality of classic Islamic sacred architecture (

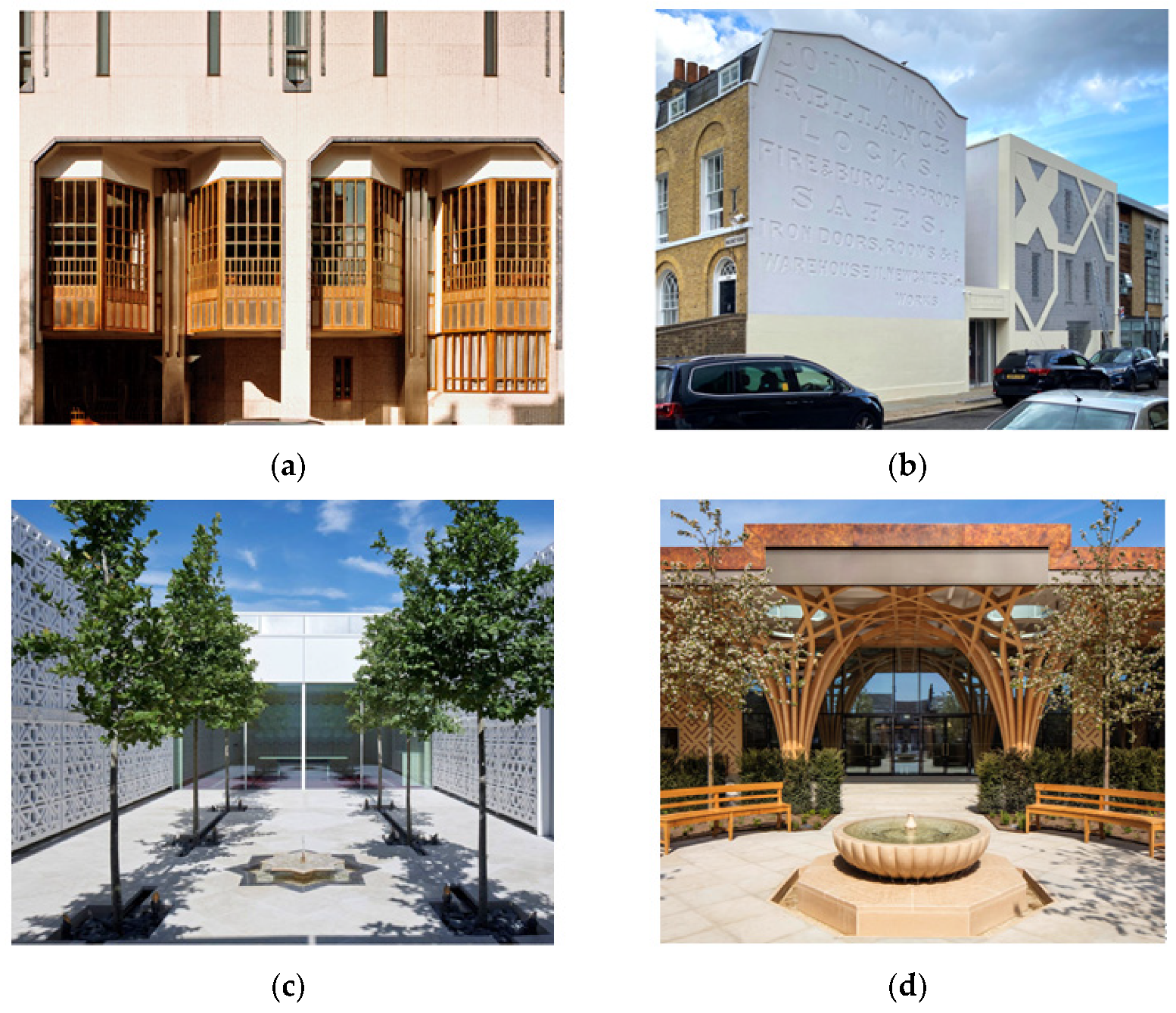

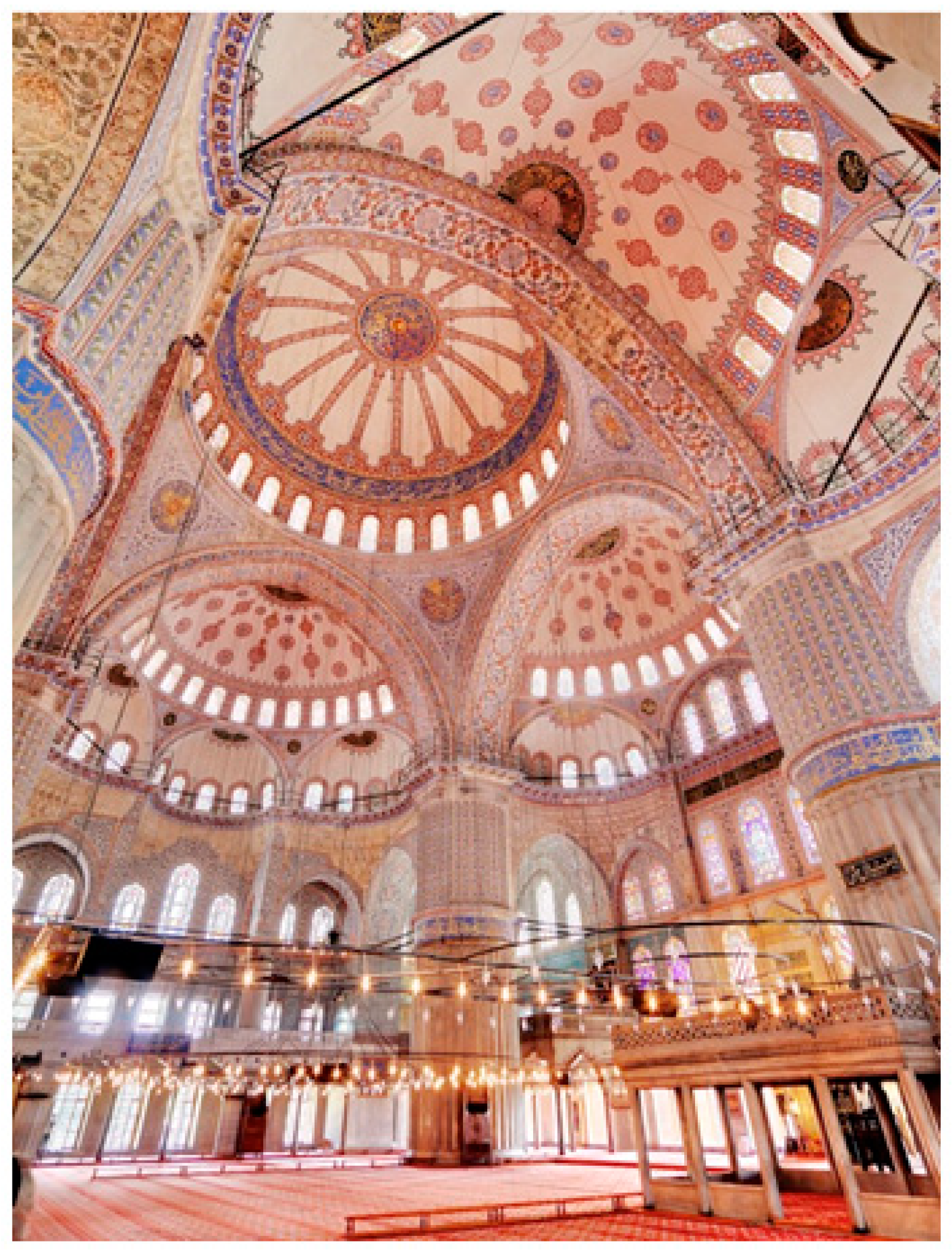

Figure 1): for example, the Ismaili Centre in London, completed in 1985 by Casson Conder Partnership; the Shahporan Mosque and Islamic Centre in London, completed by Makespace Architects in 2016; the Agha Khan Centre in London, completed in 2018 by Fumiko Maki; and the Cambridge Mosque project, completed in 2019 by Marks Barfield Architects, which has recently received the prestigious 2021 RIBA Stirling Prize. This study continues that conversation and attempts to articulate and provide structure to what others may already be experimenting with.

In the context of the practice-as-research project, rather than having a fixed identity experienced in a collective and political form, the experience of Muslim identity was considered to be a more personal process. This more personal process was related to the pursuit of spirituality and involved spiritual training to discipline the nafs (self) and awaken the qalb (spiritual heart), which is the aim of Sufism that has been described as a path to knowing the heart of Islam. Thus, the problematic of identity was redefined through an understanding of the spiritual principles, behaviours and aesthetic forms of religious life, which in non-Muslim contexts are acknowledged as often creating tension in various cultural, artistic and commercial domains (

Göle 2013, p. 6). In the context of the practice-as-research project, such tensions gave rise to a transformed approach to creative practice that allowed professional and spiritual practice to become more aligned, which was seen as an important objective for many spiritually inclined creative practitioners working in secular environments today.

The theoretical context that underpinned research on classic Islamic sacred architecture attempted to draw from various established approaches to the study of Islamic sacred art and architecture, which are often considered incompatible. These included the Traditionalist approach, where the subject is viewed in relation to its spiritual origins and creative unity, drawing largely on Sufi sources.

2 The Art Historical approach, which has dominated scholarship since the 1970s and views the subject in terms of its multiplicity, disassociating it from its spiritual roots in favour of more contextualised and historicised analyses.

3 The Theoretical approach

4 to a certain degree addresses the discrepancy between Art–historical, positivist historiography and Traditionalist, essentialist metaphysics by following multidisciplinary approaches that studied the effect of specific theoretical, political and spiritual contexts.

5 The Phenomenologist approach, concerned with interpretive studies of human experiences of sacred space that moved away from the separation of knowing subject and known object towards a view of its immersive experience and creative processes.

6 The theory underpinning the practice-as-research project aimed to integrate elements from these diverse perspectives by assigning each to its correct level of enquiry in relation to a hierarchical model of existence derived from the Quran.

In relation to developing a new framework for understanding and designing Islamic sacred space, the research identified existing design frameworks that studied the morphological and spiritual principles underlying the design of historic Islamic sacred architecture (

Ardalan and Bakhtiar 1973;

Akkach 2005) but which failed to explore contemporary design practice. Other frameworks, which did explore contemporary practice, excluded in-depth spiritual theory and focussed on quantitative and programmatic aspects related to site, budget and regulatory challenges (

Kahera et al. 2009). The Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī Centre practice-as-research project addressed this gap and attempted to reconcile quantitative and qualitative aspects of design by bridging the physical and spiritual aspects of Islamic sacred architecture. Work on the project followed a relational approach to practice which considered empirical research, types of knowledge associated with conventional research and also intuitive, more personal and even spiritual experiential knowledge that considered individual understanding and subjective interpretations to be interrelated and useful (

Barrett and Bolt 2007, p. 5). The interplay of different areas of knowledge in creative research allowed new analogies, metaphors and models of understanding to emerge that included other disciplines beyond the creative field. Practice was recognised as an actual method of knowledge production and thinking (

Barrett and Bolt 2007, pp. 7–11). Working on the Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī Centre enabled a gradual movement beyond conventional objective/subjective and empirical/hermeneutical binaries which underly the separation between the arts and humanities and the sciences. The developed framework offers a platform for examining the correlation between spiritual, imaginal and physical principles that gives rise to transformative Islamic sacred architecture specifically in the context of contemporary practice which the other frameworks failed to address. The process prioritised non-physical aspects of design where practice involved multiple transformations and intuitive insights, often in response to obstacles, problems or failures, from which the final design unfolded. The developed approach contrasted with the conventional approach that creates fixed architectural solutions that are then executed on site.

In order to relink with the wisdom of the past and the contemplative spirit of the Islamic tradition, the research drew on the spiritual principles of the Quran, believed by Muslims to be the timeless, immutable and revealed word of God. These timeless and immutable qualities aided an understanding of Islam as a global paradigm that transcends local conditions, endowing it with a universal quality (

Nasr 1987, pp. 3–4;

Ramadan 2002, pp. 53–55). On the other hand, the comprehensiveness of the Quran allowed for the infusion of localised meanings (

Hodgson 1974, p. 79;

Metcalf 1996, pp. 1–27;

Nasser 2002, pp. 173–86). These seemingly paradoxical attributes were reconciled when viewed in relation to a dynamic and hierarchical worldview that is both universal and exclusive. Architecturally, this implied a unified palette of universal principles underlying the built form, capable of manifesting infinitely diverse forms that all reflected transcendent spiritual qualities. This approach allowed for long standing debates regarding the definition of Islamic art and architecture

7 to come together and resulted in a redefinition of Islamic art and architecture as embodying the forces and principles of the Islamic Revelation, which transformed the creative expressions of cultural, geographical and temporal localities, resulting in multiplicities of form that all capture the unity and spirit of Islam.

Created by a team of initiated Sufi disciples of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Order,

8 the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project provided an ideal opportunity to explore the creative processes and issues involved in bringing transformative contemporary Islamic sacred architecture into being in a particular spatial and temporal context. In the course of working on the project, a transformed approach to creative practice emerged and the classic Islamic sacred buildings and their creative and communal contexts were seen differently, which allowed for a better appreciation of how they were inspired by a view of the physical world as a symbol and image of the spiritual world (

Nasr 1987, p. 296). The research allowed deeper understandings of the physical, experiential and spiritual dimensions of those classic buildings, which inspired a more comprehensive approach to architectural practice and a more integrated understanding of the relationship between creative and spiritual practice and of the creative and spiritual needs of others. The framework developed through the practice-as-research process potentially offers Muslim creative practitioners a method to overcome what has been described as ‘the effects of Western intellectual colonialism’ that continue to affect Muslim culture into the present age (

Ozkan 2002, pp. 85–87) but which may also be relevant to other spiritual contexts. Traditional and contemporary approaches to sacred architecture have been considered reconcilable by viewing creative originality in terms of ‘evolving vocabularies of form’ that reclaim and renew traditional models (

Nosyreva 2014, pp. 50–51).

Considering the metaphysical and ontological roots of Islamic sacred architecture when designing contemporary spaces was considered to be of particular importance. By remaining firmly rooted in principles from the Quran, new views of existing principles unfolded in the act of interpretation, which reflected existing research into the relationship between historic notions and issues of interpretation, reproduction and representation (

Snodgrass and Coyne 2006;

Barrie 2010;

Barrie et al. 2015;

Bermudez 2015). This more integrated approach shed new light on understanding how symbolism, geometry, light and sound were used in the design of transformative examples of classic Islamic sacred buildings. The efficacy of this renewed framework in creating physical forms, spatial sensibilities and spiritual meanings, specifically related to the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi tradition, was explored by constructing the new Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre in London.

The practice-as-research project as a whole explored key notions such as the imaginal realm, fayḍ (Divine energy), khayāl (imagination), qalb (spiritual heart) and ta’wīl (spiritual interpretation) and their role in understanding and designing Islamic sacred space. It also examined the efficacy of the developed framework in addressing issues arising from conventional building and planning processes through immersive experience and intuitive insight. This transformed approach to creative practice emerged as a contemplative process intimately related to spiritual practice, a relationship shown to have historically informed the inner dimensions of making in the Islamic tradition (

Ibish 1979, pp. 570–73;

Nasr 1987, pp. 3–13;

Hamdani 2002, pp. 157–76;

Michon 2008, pp. 84–86;

Ridgeon 2010, pp. 106–8;

Nosyreva 2014, p. 201;

Nasrollahi 2015, pp. 86–99). Finally, the study explored whether Islamic sacred architecture designed according to a Divine order and purposely attuned to the flow of fayḍ (Divine energy) potentially creates spatial sensibilities

9 that support and inspire transformative experiences of the Divine Presence or Tawḥīd (Oneness).

2. Spiritual Principles Underpinning the Design of Islamic Sacred Space

Historically, Islamic religious architecture brought diverse typologies together under one roof to serve a community (

Frishman and Khan 2002, p. 30;

Buğdaci and Erkoçu 2009, p. 137). With progressive secularisation in the Muslim and non-Muslim world, these functions were separated and Islamic religious architecture was used mainly for spiritual practice and became classified as 'sacred space’. The term ‘Islamic sacred space’ is, therefore, a necessary divergence from the classic Islamic view that does not classify space in terms of ‘sacred' or ‘profane’ but rather considers all the earth to be sacred (

Frishman and Khan 2002, p. 267). Indeed, in Islam, the entirety of existence forms a space for God to reveal Himself (

Mahmutcehajic 2006, p. 29). The Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project, through practice-as-research, adapted the functional diversity of the past, drawing on examples of classic Islamic architecture that represented diverse forms, functions, locations and historic periods. In doing so, it reflected on this functional diversity and how spaces may be brought together to go beyond notions of typology, location, time, style and scale.

The relationship between sacred space and spiritual experience, where the physical and spiritual realms meet, was explored in relation to the notion of the barzakh (liminal space) from the Quran.

10 Macrocosmically, the barzakh is the intermediary realm that separates the physical and spiritual worlds and reflects both of their attributes. Microcosmically, the barzakh is the nafs (self) mediating between rūh (spirit) and jism (body) (

Chittick 1989, p. 17). Alternatively, it is the qalb (spiritual heart) mediating between ‘ālam al khalq (the created realm) and ‘ālam al amr (the realm of God’s Command) (

Dahnhardt 2002, pp. 130–38). Sacred space as barzakh highlighted the ontological relationship between physical and metaphysical dimensions of Islamic sacred space and the analogous relationship between macrocosm and human microcosm. In this context, exploring the realm of human experience became fundamental for understanding and for design.

The research drew primarily on Traditionalist and Phenomenologist sources to aid a movement away from third-person observer towards a first-person experience of architectural space, which was considered essential to understanding its transformative dimensions (

Mahmutcehajic 2006, p. xvii;

Bermudez 2009, p. 48). Art–historical sources, considered useful in contextualising Islamic sacred architecture, were seen to largely hinder this ability to access transcendent experiences of sacred space.

11 The spaces of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre aimed to reflect its function as a barzakh that supported visitors in turning away from the world, as inspired by interpretations of classic Islamic sacred buildings.

The transformative power of Islamic sacred space was found to originate from the ḥaqā’iq (inner realities) of the Quran, which are also the primary realities of the cosmos, and from the Prophetic Substance from which flows al-barakāt al-muḥammadiyyah (the Muḥammadan grace). Al-barakāt al-muḥammadiyyah was seen to inspire the creative act and allow the ḥaqā’iq to crystallise in the corporeal world (

Nasr 1987, p. 6). In Sufism, al-barakāt al-muḥammadiyyah is described as fayḍ or barakah, Divine energy or spiritual light that emanates from God. It is the enabling energy utilised to travel from human microcosm to macrocosm causing spiritual transformation (

Buehler 2008, pp. 117–202).

The ultimate aim of spiritual practice and of Islamic art and architecture was considered to be dhikr Allāh (remembrance of God). When viewed in a contemplative state, sacred space potentially inspires and actualises dhikr Allāh, connecting human beings to God (

Nasr 1987, p. 4). The Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project explored how Islamic sacred space may be designed to purposely attune to the flow of Divine energy by conforming to an order that reflected the inner realities of the Quran and the primary realities of the cosmos. It examined the nature of such contemplative designs and their potential to create spatial sensibilities that affect the spiritual heart and support the transformation of the self by reflecting Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual transmissions.

In Islam, symbolism was found to be fundamental to understanding the transformative quality of Islamic sacred space. Symbolism was considered to reveal spiritual meaning and to support spiritual experience (

Akkach 2005, pp. 30–32). It was defined in relation to the original Greek verb symballein (to agglomerate or throw together), where symbols in different cosmological and ontological realms are joined together, forming an integral unity (

Corbin 1971, p. 28). In the Quran, existence is described in terms of hierarchical cosmological realms with corresponding ontologies leading from al-Dhāt (The Divine Essence) to the physical realm (

Chittick 1982, pp. 107–28). The cosmological realms were defined as al-mulk (the physical world), al-malākūt (the intermediary or angelic world), al-jabārūt (the archangelic world), al-lāhūt (the world of Divine Names and Qualities) and al-Dhāt (the Divine Essence) or al-Hāhūt (Ipseity) (

Nasr 1987, pp. 180–81). Each realm is a reflection or shadow of the one ‘above’ it so that, for each symbol in the physical world, a sequence of amthāl (archetypes) exists that culminate in the Divine Essence (

Lings 2005, pp. 12–13).

12 Through this inherent hierarchy of existence, symbols intended as conduits to higher, subtler realms can actualise communion with God (

Akkach 2005, pp. 30–32).

The word ‘amthāl’ (sing. mīhāl) highlighted the importance of ‘ālam al-mīhāl (the world of similitude) of which Plato’s archetypal world is a part. It is associated with al-malākūt (the intermediary or angelic realm), which is also referred to as the world of imagination (

Nasr 1987, pp. 180–81) or the imaginal realm (

Corbin 1964, pp. 3–26). This intermediary world possesses form and jism-i-latīf (subtle matter) and does not constitute physical matter (

Nasr 1987, pp. 180–81). The imaginal realm begins beyond the cosmic sphere of sensory perception and is reached only by internalising or travelling inwards (

Corbin 1964, p. 6). This ontological nature of symbolism indicated that symbolic forms play a fundamental role in activating the link between the physical and spiritual realms and in unifying various levels of meaning. This view provided the basis for a more integrated view of the physical world and of sacred space as encompassing transcendent metaphysical and ontological dimensions. In order to create the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre, an understanding of the use of symbolism in classic examples of Islamic sacred architecture was deemed necessary to connect to transformative levels of meaning in design and to reveal the nature of the relationship between sacred space and spiritual experience.

The Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual path provided a framework for studying and reflecting on spiritual experience. In Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi conceptions, the spiritual heart is considered the locus of God’s light, capable of understanding symbols (

Rasool 2010, pp. 130–33). Spiritual practices are designed to awaken the spiritual heart and to transform the self, resulting in greater awareness of the Divine Presence (

Rasool 2003, pp. 86–87).

13 The Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project explored how far forms designed to symbolise the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual path could be meaningfully developed in contemporary contexts.

Existence was considered a manifestation of the integral unity of Tawḥīd (Oneness). In this context, Tawḥīd was understood as the experience in the innermost kernel of the heart (lubb) of Divine Unity. It is the central premise of Islam (

Schimmel 1994, p. xiv). Macrocosmically, Tawḥīd gives rise to the spiritual principle ‘multiplicity in Unity’ seen as the basis for creation, as God’s Presence radiates through the levels of existence to the physical level, which has been referred to as the ‘arc of descent’ in Sufism. Microcosmically, the spiritual principle ‘Unity in multiplicity’ was found to be fundamental to the design of Islamic sacred space, as the contemplation of symbolic forms and their archetypes follows an ‘arc of ascent’ through the levels of existence potentially leading to God’s Presence, a process that reflects the spiritual path (

Ardalan and Bakhtiar 1973, pp. 7–9).

The relationship between macrocosm and human microcosm was simplified in terms of three key cosmological realms—the physical world, the imaginal world and the spiritual world, with their respective organs of perception—the senses, khayāl (imagination) and the spiritual heart. Khayāl has been described as, ‘The epiphanic place for the images of the archetypal world’ which allows each realm to symbolise with each other by virtue of real corresponding subtle or spiritual forms. Khayāl provided the foundation for an analogical knowledge that overcomes the limitations of rationalism (

Corbin 1964, p. 9) and enables a gradual movement beyond conventional binaries.

The analogous relationship between the physical and spiritual realms mediated by the imagination was further understood in relation to the principle zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen) from the Quran (10:25), where every manifestation has an outward visible existence (zāhir) and a hidden inner reality (bātin) that sustains it. This principle derived from a conception of God denoted by the Divine names al-Bātin (the Unmanifest), utterly unknowable and beyond being, and al-Zāhir (the Manifest), creating the universe in an act of Self-disclosure in order to become known (

Chittick 1984, pp. 47–48). Al-Zāhir is represented by the Divine Names and Attributes that describe the relationship between God, the cosmos and human beings and which only human beings have the capacity to understand (Quran 2:31–32). The Divine Names and Attributes are anthropomorphic, understood in light of self-knowledge, which also reveals the theomorphic nature of human beings, who God fashioned and breathed His own Spirit into (

Chittick 1998, pp. xvii–iii). This brought to light a relationship between human beings and God where the Divine Names and Attributes are experienced in one’s own mode of being, which further unraveled the nature of spiritual experience (

Corbin 1998, pp. 144–45).

The Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project explored how zāhir wa bātin, viewed through the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi lens, informed the creative process that gave rise to sacred space and which also affects a visitor’s experience of it. To this end, the design of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre explored ways to inspire and gradually deepen an embodied awareness of the hidden inner reality underlying outward visible forms, in order to prepare a visitor for participating in the spiritual practices and to sustain the spiritual states achieved through them. A view of zāhir and bātin as two ends of one continuum emerged that helped alleviate some of the challenges that the project faced. For example, allowing dichotomies such as contemporary/traditional, worldly/spiritual and public/private to be reconciled. It also informed a more intuitive and responsive approach to design where challenges and setbacks allowed the design to become further refined.

Directly related to this process of making and experiencing Islamic sacred architecture was ta’wīl (spiritual interpretation), where the literal appearance of something was viewed, interpreted and referred back to the hidden principle or archetype that determined its nature (

Corbin 2013, p. 38). Ta’wīl was considered the means by which the multilevelled nature of symbols was revealed, which was dependent on the interpretative level from which they were viewed and experienced, as well as the spiritual state and capacity of the viewer. The process of spiritual interpretation emphasised the imaginal realm and the imagination, which translates sensory data into symbols (

Corbin 1998, p. 80). This was due to the relationship between

khayāl (imagination) and Khayāl mutlaq (absolute unconditioned imagination), where all forms were considered to exist in a state of latent potentiality. Divine creation was understood as the passage from bātin (hidden) to zāhir (manifest) in a process of tajjali illāhi (Divine theophany), understood as the act of primordial Divine imagination (

Corbin 1998, pp. 185–86). Divine imagination veils and unveils hidden inner realities whilst the imagination discriminates between hidden and manifest. The analogous relationship between the imagination and the absolute unconditioned imagination allows human beings to gain nearness to God through understanding His symbols using spiritual interpretation. In this respect, the imagination became fundamental in understanding and designing Islamic sacred space, where the physical world reflected the spiritual world, human microcosm reflected macrocosm, human imagination reflected Divine imagination and human creativity reflected Divine creation.

In the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project, the process of spiritual interpretation was explored in relation to the intuitive and transformative dimensions of Islamic creative practice as well as a visitor’s transformative experience of space. The process of seeking meaningful interpretations of phenomena through spiritual interpretation became essential in overcoming difficulties encountered through the design process, allowing them to be seen as opportunities for personal spiritual growth and for further refinement of the design.

As mentioned, the relationship between human beings and God, where the Divine Names and Attributes are experienced in one’s own mode of being, emphasised the importance of self-knowledge in attaining God consciousness and the importance of spiritual practice as a means to self-knowledge (

Chittick 1998, pp. 7–8). The relationship between self-knowledge and awareness of God was described as having two aspects; tanzīh (transcendence) and tashbīh (immanence) which related to the doctrine of wujūd (being, existence or finding). Wujūd unfolds from the Oneness of God and enfolds the multiplicity of creation (Ibn 'Arabi 13thC/

Chittick 1998, pp. 7–12).

14 Wujūd was also described as a hierarchical order possessing gradations of intensity or light, where an important distinction was made between wujūd understood as ‘being’, equated with the unknowable Divine Essence, and wujūd understood as ‘existence’, described as the essence of all unmanifest or manifest entities. The relationship between wujūd as ‘existence’ and wujūd as ‘being’ was compared to waves on the sea (Shāh Wali Allāh 18thC/

Baljon 1986, p. 59).

In this context, the multileveled notion of wujūd assisted a conceptual framework for understanding how Islamic sacred space inspired spiritual experience, where spiritual experience was wujūd understood as ‘finding’ (

Chittick 1989, p. 5). Transcendence posited that wujūd (being) belongs solely to the Divine Essence, which cannot be known, upholding the transcendence of God and the incomparability of human beings viewed as ‘abd (servant). On the other hand, God is al-Wujūd al-Muṭlaq (Absolute Being), denoted by the name Allāh, and the created realm shares in wujūd by virtue of existing and is, therefore, a manifestation of God, upholding the immanence of God and a view of human beings as khalīfa (vicegerent) (

Chittick 1998, p. 8). Transcendence and immanence were considered two sides of one coin, God as unknowable Essence and a more personal God who reveals His closeness through self-knowledge and spiritual experience.

3. Reclaiming the Wisdom of Classic Islamic Sacred Architecture

The relationship between physical, imaginal and spiritual dimensions of Islamic sacred space was explored through a framework that was articulated in terms of symbolism, geometry, light and sound, which were considered archetypal languages that forged the link between the physical and spiritual realms, operating through the agency of the imaginal realm. These archetypal languages were integrated to create designs that aimed to align human microcosm and macrocosm. The physical manifestations of symbolism, geometry, light and sound were explored by conducting textual analysis and case studies that examined the architectural techniques utilised to create physical forms that functioned as conduits to higher spiritual realities.

In researching how the features and qualities of classic Islamic sacred architecture could be reclaimed, the efficacy of the framework was examined in view of Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual principles and practices through the process of creating the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre. The process revealed that examining the spiritual principles and archetypal languages embodied by classic examples of Islamic sacred space and conforming to a hierarchical order of existence enabled the ontological nature and metaphysical roots of Islamic sacred space to be expressed in form. Islamic sacred architecture designed according to a Divine order and purposely attuned to the flow of fayḍ (Divine energy) in this manner potentially creates transformative spatial sensibilities that support and inspire experiences of Divine Presence or Tawḥīd (Oneness).

3.1. Symbolism

Symbolism was considered the common thread underlying expressions of spatiality, geometry, light and sound in classic Islamic sacred architecture. The analogous relationship between spiritual experience and sacred space, expressed using symbolism, is mediated by the spiritual heart and enhanced by contemplative practice. Symbolism was found to be the corner stone of the transformative quality of sacred space, connecting the realm of human experience to deeper ontological spiritual realms.

The conception of transcendence and immanence aided an understanding of transformative experiences of classic sacred Islamic architecture, as well as a transformed approach to creative practice. It was through immanence that the outer and inner symbols were found to potentially unlock spiritual experience. Sacred space was understood as a direct symbol of wujūd (being), which bridged the gap between the spiritual and physical realms. Sacred space was likened to the spiritual heart, as the place of submission and the locus of knowing that is experienced as love (

Mahmutcehajic 2006, p. 25). The capacity to experience existence as a symbol of God, which potentially actualises an experience of the Divine Presence, was directly related to the degree that the spiritual heart was awakened through spiritual practice and was at the core of the synthesis between spirituality, religious practice, creativity and professional practice.

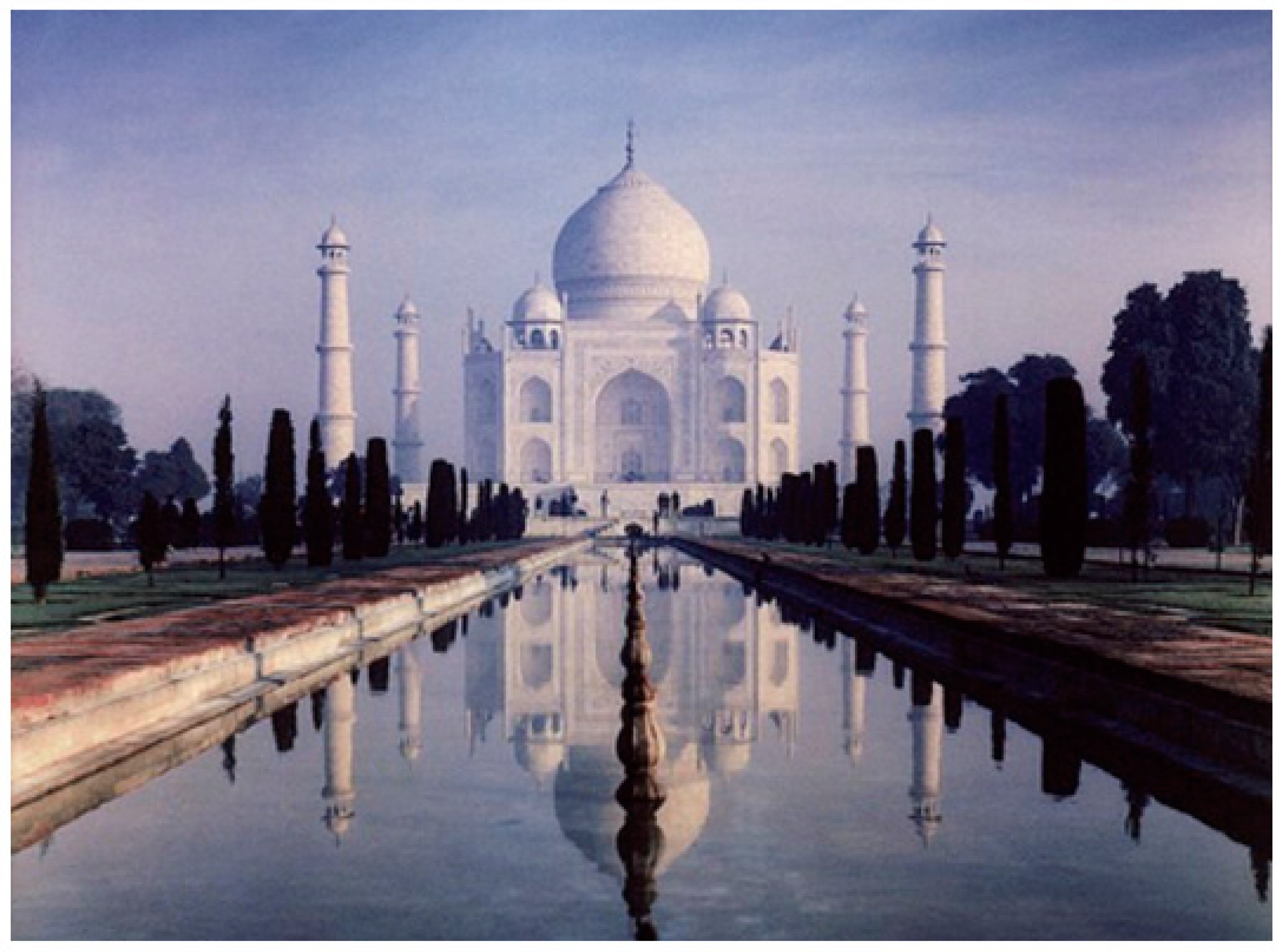

The use of symbolism was further articulated in terms of symbolic narratives that unfolded as a visitor moved through space. The notion of unfolding symbolic narratives was explored from a cosmological standpoint through research on the Taj Mahal complex in Agra, India (

Begley 1979) and the Alhambra in Granada, Spain (

Avendano 1994). In the case of the Taj Mahal, several levels of meaning were revealed by moving through the complex that suggested it was intended as an allegory of the Day of Resurrection, not only as a mausoleum as popularly believed (

Begley 1979, pp. 10–25). Three levels of meaning were identified: physical, with direct correspondences between architectural forms and inscriptions from the Quran; imaginal, represented by a thematically unified program for the inscriptions; and spiritual, by comparing mystical depictions of the Day of Judgement in paintings and manuscripts with the architectural plan and layout (

Begley 1979, p. 13;

Akkach 2005, p. 128). From an ontological standpoint, the architecture was found to powerfully appeal to the imagination, awakening the spiritual heart by evoking an experience of the principle zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen), as the visible form appeared to unfold from a field of light (

Figure 3).

The symbolic narrative unfolded as each space was experienced independently and as part of a whole. The interpretative process unfolded ‘horizontally’ moving through physical space and ‘vertically’ as deeper layers of meaning were unveiled inwardly. This horizontal and vertical movement was compared to ‘the journey to God’ and ‘the journey in God’ from Sufi conceptions of the spiritual path that proceeds in four stages, which also underpins the conception of the four circles of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual path; the journey to God that negates all other than Him, the journey in God that contemplates the essence of Unity, the journey with God that contemplates the Absolute Essence and, finally, the journey from God that returns to the world of contingency (

Shihadeh 2007, p. 93).

3.2. Geometry

A geometric order is considered to underlie the cosmic order and the order of nature and was utilised throughout history to align the human realm to a Divine order through made objects (

Critchlow 2011, pp. 291–92;

Azzam 2013, p. 8;

Marchant 2013, p. 34). The discipline of geometry and its use in Islamic art and architecture demonstrated an interpretation of the Quran underpinned by the belief that the world unfolded from God in a knowable manner (

Marks 2010, pp. 153–59). The historical development of geometry indicated that it was utilised as a hermeneutical tool to elucidate metaphysical notions that reflected the cosmological and ontological qualities of existence (

Akkach 2005, p. 64). The combination of architectural form and geometric pattern was considered a practical, visual dialogue between art and science, where geometry expressed experimentation with mathematical and philosophical theories (

Critchlow 1976, pp. 42–70;

Chorbachi 1989, pp. 751–89;

Özdural 2000, pp. 171–201;

Bier 2009, pp. 827–51;

Bier 2012, pp. 251–73).

The contemplative, symbolic and potentially transformative natures of number and geometry were widely considered to have played an important role in Sufi metaphysics in describing the order of existence and the nature of creation as a manifestation of God (

Ardalan and Bakhtiar 1973, pp. 21–27;

Burckhardt 1976, p. 12;

Nasr 1987, pp. 47–50;

Jones 2000, pp. 225–27;

Akkach 2005, pp. 56–57;

Marks 2010, p. 159;

Azzam 2013, p. 13;

Nosyreva 2014, p. 110). The role of the spiritual heart in the perception of geometry was also emphasised and was thought to have resulted in a rational but subjective approach to aesthetics (

Marks 2010, pp. 153–59).

Historically, the knowledge embodied by geometry was upheld by craft guilds that were linked to Sufi Orders, indicating a connection between creative and spiritual practice that alluded to geometry’s transformative quality (

Critchlow 1976, p. 8;

Ibish 1979, pp. 570–73;

Hamdani 2002, pp. 157–76;

Ridgeon 2010, pp. 106–8;

Azzam 2013, p. 13). Contemplating geometry was seen to be capable of inspiring intuitive connections to the spiritual realm mediated by

khayāl (imagination) (

Marks 2010, pp. 161–62). Practising geometry was found to potentially lead to higher states of being (

Andreola 2014, p. 222). For these reasons, geometry surpassed its use as a design tool and became a vehicle for the realisation of metaphysical truths that supported spiritual experience, a process reflected by the design project.

The process of spiritual interpretation revealed levels of meaning embodied by the unfolding layers of a geometric design that symbolised the hierarchy of existence. In enfolding the dimensions of a geometric pattern back through an understanding of their inner nature, it became possible to return to the source or point of unity (

Critchlow 1976, p. 7;

Andreola 2014, p. 184). This process of unfoldment and enfoldment was seen as a reflection of the principle zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen) and recalled the notion of the arc of descent and the arc of ascent previously described.

Geometry was described as an intermediary space or state of being that extended beyond object and subject, unifying the physical and spiritual realms, comparable to the notion of the barzakh (liminal space) previously discussed (

Andreola 2014, p. 221). It was, therefore, capable of bringing about new knowledge or new states of being, affecting both designer and viewer, even if there was no conscious understanding of its symbolic meanings (

Marks 2010, pp. 151–56). Geometry embodied higher qualities experienced by the designer, which were radiated and externalised through the created work to be experienced by others, which completed the circle of communication (

Ardalan and Bakhtiar 1973, p. 10;

Andreola 2014, p. 208). In this manner, the union of knower, knowing and known satisfied the primary function of sacred space as a bridge between the physical and spiritual realms.

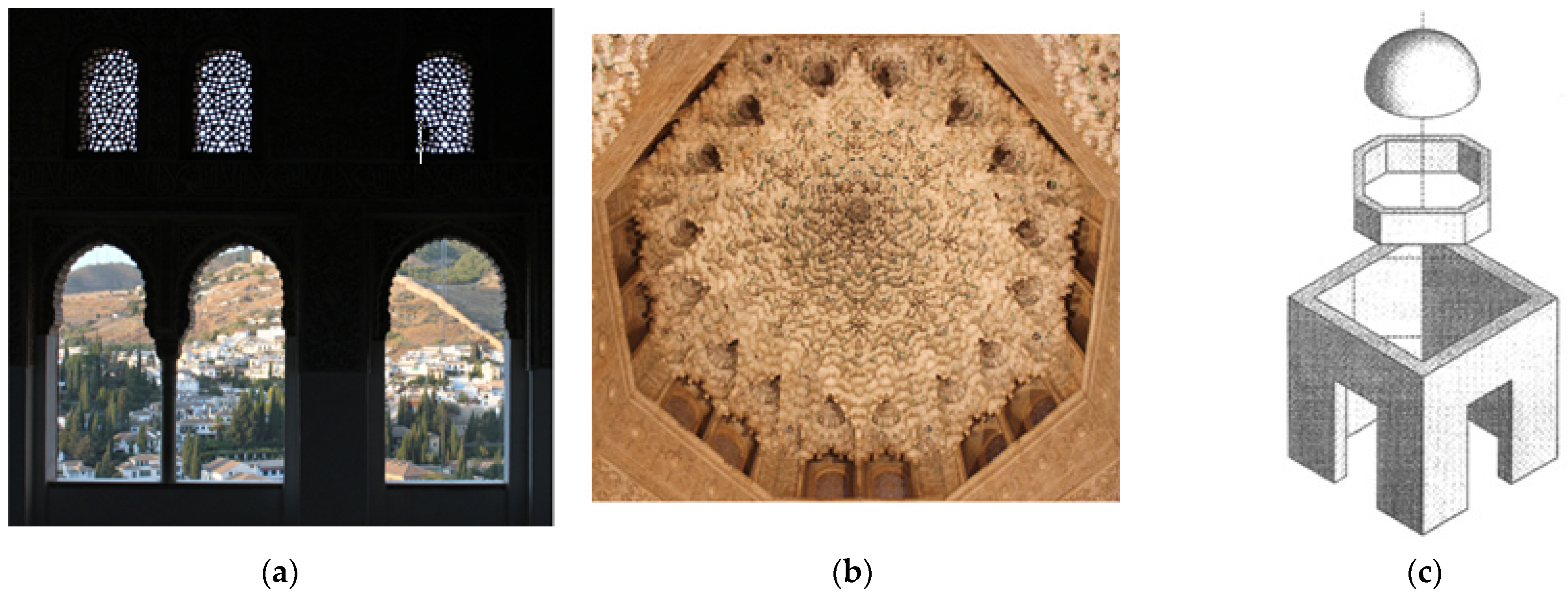

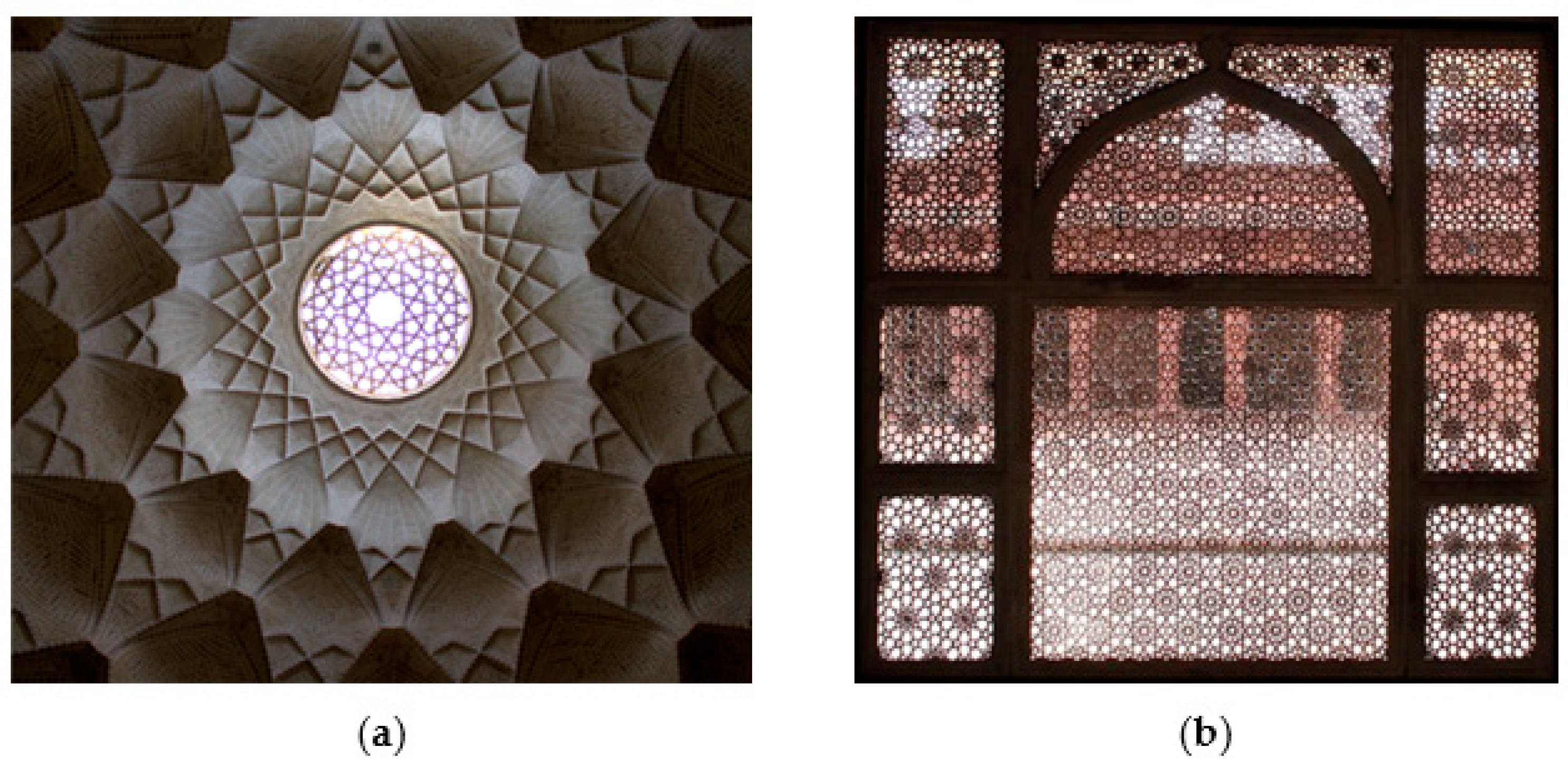

In the design of Islamic sacred space, geometry was found to operate at different stages and scales of an architectural design to create conformity with the Divine order and had visible and hidden dimensions. It was utilised to position and proportion architectural elements such as doors, windows and screens to create two-dimensional surface patterns and also informed the structure of epigraphic calligraphy. Three-dimensional applications hidden from view played a fundamental role in spatial ordering, structural solutions and for designing elements such as arches, vaults and domes. Visible three-dimensional applications informed the design of sculptural elements such as muqarnas (stalactites) and crenellations. Cosmograms were important organising geometries which symbolised the hierarchy of existence through the three key cosmological levels, al-mulk (physical realm), al-malākūt (the intermediary or angelic world) and al-jabārūt (spiritual realm), depicted in terms of a circle, octagon and square and organised over an underlying eightfold geometry of interlocking squares. This basic structure informed the composition of traditional domes that transferred structural loads from a circular dome, through octagonal squinches, to a square base (

Figure 4).

In the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project, geometry was instrumental in visually depicting the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual path in ways that attempted to unlock the transformative qualities of space.

3.3. Light

In Sufism, light expressed a metaphysics of essences emanating from the Divine Essence (

Corbin 1998, p. 22). In the Quran, light gave rise to sight and denoted belief or faith. In its outward aspect (zāhir), light symbolised Unity; in its inward aspect (bātin), it symbolised faith, the vehicle for reintegration to Unity. These aspects reinforced understandings of the correlation between macrocosm and human microcosm. The notion of alternations of darkness and light was found to be a recurrent theme in the Quran (

Schimmel 2011, p. 12).

15 In Sufi understandings of the Quran, the use of light and darkness represented the principle zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen) but often interchanged, which supported an understanding of this principle as two poles of one continuum revealing the illusion of polarity that is characteristic of the physical realm and which can be transcended in an experience of Tawḥīd (Oneness) (

Pott 2009, pp. 101–16).

The research revealed a correlation between architectural light and metaphysical light based on the inherent symbolism of the universe (

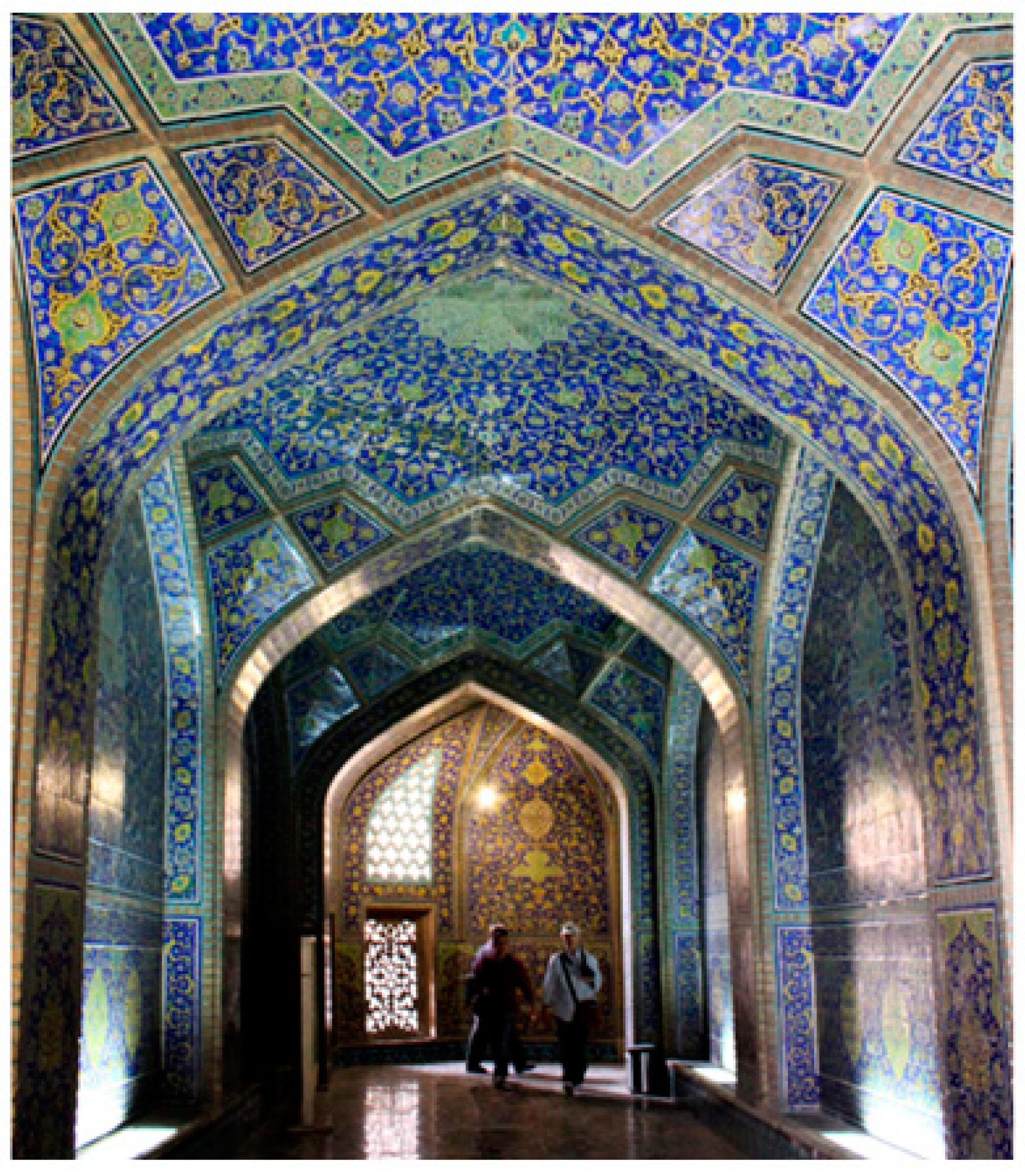

Nasr 1987, p. 54). In classic examples of Islamic sacred architecture, light was used to manipulate the perception of form and to inspire particular experiences of space by stimulating khayāl (the imagination) and potentially awakening the spiritual heart, leading to states of contemplative interiority that were a foundation for ta’wīl (spiritual interpretation). Alternations of darkness and light were used dynamically to direct attention and movement in subtly nuanced sequences that corresponded to experiential narratives. By alternating darkness and light to direct attention and movement in this manner, it was found that it gradually affected a visitor’s spiritual state, inspiring them to gradually turn their attention inwards towards their spiritual heart. For example, it was common to enter into darkened vestibules and to follow bending corridors, finally emerging into a space flooded with light. This process encouraged a series a physical pauses that gradually increased self-awareness and a sense of detachment from the outside world and culminated in a dramatic experience of blinding light that induced an equally dramatic ontological shift. The Shaykh Lutfalla Mosque in Isfahan (

Figure 5) and the Sultan Hassan Mosque and Madrassa in Cairo (

Figure 6) were particularly good examples of this use of light to direct attention and movement. They incorporated several significant changes in lighting levels as a visitor travelled through, significantly deepening their contemplative state in anticipation of what lay beyond.

The Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre sought to reclaim something of the role that light played in creating embodied experiences that change a visitor's conscious state, which was so dramatically expressed in these classic examples. In the design, lighting played a significant role in creating spatial sensibilities that inspired ontological shifts as part of an experiential sequence that prepared a visitor to undertake spiritual practices.

In relation to spiritual practice, moving sequentially through spaces that alternated between darkness and light was compared to periods of ‘darkness’, denoting spiritual hardship or contraction, followed by periods of ‘light’, denoting spiritual growth and expansion, which are experienced at various stages of spiritual development. This suggested that both darkness and light were necessary aspects of the spiritual path. In working on the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre, spiritual experiences of the alternation between darkness and light became an important aspect of the transformed approach to creative practice, where challenges and setbacks became viewed as opportunities for spiritual growth.

The static use of light to inspire powerful ontological shifts, either as a visitor emerged into an open courtyard or entered a prayer hall flooded with light, was seen to symbolise being in the presence of God, evoking the Divine name al-Nūr (the Light) (

Schimmel 1994, p. 12). These were spaces of unity and peace (

Kreuz 2008, p. 66), evoking the infinite nature of God as well as the joy of communal worship (

Kuban 1999, p. 30). Courtyards were considered the physical centre or heart of a building and symbolised God’s omnipresence as well as the infinitude of the self’s inward dimension (

Nasr 1987, pp. 50–51;

Lings 2005, p. 108) (

Figure 7). This was understood to signify the correlation between macrocosm, denoted by the courtyard open to the sky, and human microcosm, denoted by the spiritual heart illuminated by spiritual light. Enclosed, brightly lit prayer spaces were found to have a similar effect (

Kuban 1999, p. 30) (

Figure 8). An analogous relationship between interior and exterior emerged, which was understood to symbolise the correlation between zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen) and sacred space and spiritual experience and was emulated in the design of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre.

In the Quran (33:45–46), light and luminosity were also associated with the Prophet Muḥammad (S), where Divine light was described as radiating through him (

Schimmel 2011, pp. 12–13). The Prophet’s (S) pre-eternal light, al-Nūr al-Muhammadī (The Muhammadan Light), was understood as the primary manifestation of the Divine Essence and the source of all creation (

Rubin 1975, pp. 62–119;

Buehler 2012, p. 115). It was found to be equivalent to fayḍ (Divine energy), which was considered the source of Islamic art and architecture, previously identified in relation to the inner realities of the Quran and the realities of the cosmos and which underpinned the creative act and permeated corporeal matter, endowing it with sacred qualities. An aim of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre was to attract and cultivate the flow of Divine energy by reflecting cosmological and ontological aspects of Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual practice, thereby actualising its transformative qualities.

Creative success was explored in relation to accessing the archetypal world by personally cultivating the flow of Divine energy through the spiritual heart or being instructed by a master who has done so (

Nasr 1987, pp. 7–8). Sufi practices were formulated for this purpose, in a process that has been described as a descending of lights that is experienced like rain or subtle rays (

Rasool 2003, p. 94;

Buehler 2012, pp. 117–18). These ideas and experiences developed a view of the nature of Islamic sacred space as characterised by a continuum between spiritual truths, creative process, physical form and human experience, all interlinked by the illuminating flow of Divine energy.

The design of artificial lighting often reflected the same tendency for spaces to be flooded with light. It was typically achieved by hanging numerous lamps at equal intervals or on circular structures at low level creating a human scale within the overall monumental scale of a space (

Figure 9). This approach influenced the lighting design of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre, which incorporated bright and even indirect lighting on the ceilings as well as wall lights at a lower level to create a human scale within a more lofty space.

Interplays of light that interacted with geometric forms to create complex patterns and textures of solid and void, light and shadow, were another significant use of light in classic examples of Islamic sacred architecture. These interplays of light provided a sense of depth, expansion and immateriality that appeared to disperse and dissolve matter from zāhir (seen) to bātin (unseen). The textured surfaces, often arranged in layered planes, symbolised the hierarchical nature of existence and God’s absolute and infinite nature, reflecting the understanding of light previously described in terms of an emanation of essences from the Divine. Perforated screens composed of geometric patterns directly reduced the mass and solidity of surfaces. Indirectly, they cast shadows that interrupted the continuity of interior surfaces. This recalled the notion of the veil that separates human beings from God, which in Islamic thought conceals the underlying unity of existence, an effect often achieved quite literally using astounding interlacements of stone (

Figure 10). A prophetic saying stated that were the veil to be withdrawn, God’s light would be all-consuming.

16The notion of the veil influenced the design of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre and helped resolve the tensions between dichotomies such as private/public, spiritual/worldly aspects of the design. Light was either used directly or interplays of light were created by perforating contiguous surfaces in order to break up their mass.

3.4. Sound

In Islamic thought, the correlation between human microcosm and macrocosm that was described by principles of mathematical harmony reflected a conceptual continuity, traceable to the Pythagorean tradition, and directly related to Islamic spirituality and the symbolic nature of the Quran (

Moore 1976, pp. 34–35;

Nasr 1987, p. 47;

James 1995). The mathematical language of musical harmony gave rise to musical proportions which corresponded to the geometric proportions that were embodied by Islamic sacred architecture as previously discussed. These proportions also described the relationship between numerous phenomena in the physical realm and the cosmos (

Tame 1984;

Burger 1997, pp. 143–47;

Helmholtz 2007;

Critchlow 2011;

Marchant 2013).

17 Sound was believed to have cosmological connections, elucidating the relationship between Divine creation, nature and human beings. The proportional relationship between musical harmony, the human body and sacred geometry was considered the foundation for designing Islamic sacred space (

Ikhwān as-Ṣafā 1978, pp. 54–56).

In the Quran, hearing, similarly to sight, was considered a function of the spiritual heart.

18 The highest function of sound was to make the spiritual heart present with God (

Hujwiri 1985, p. 405). Islamic texts on audition illustrated the powerful ontological function of Quran recitation and sacred sounds, shown to be capable of inducing states of spiritual ecstasy and even death, depending on the aptitude of each soul (

Ikhwān as-Ṣafā 1978, pp. 71–73;

Hujwiri 1985, pp. 394–407). Sounds were believed to possess modulation, quality and spiritual form, perceived by the auditory faculty and transmitted to the imagination. They had the ability to soften the spiritual heart and awaken the self (

Ikhwān as-Ṣafā 1978, p. 39). These ideas supported an understanding of a symbolic nature of sound that linked the physical and spiritual realms through the intermediary imaginal realm.

The Quran states that the entire universe came into being through the primordial sound Kun! (Be!).

19 It also stated that sound, in the form of a single trumpet blast, will end all existence at the end of time. This understanding of the nature of sound as an active force and an ontological reality allowed for a deeper engagement with the words of the Quran that are recited in Islamic sacred spaces, which have been described as ‘beings, powers or talismans’ (

Schuon 2004, p. 60). Quran recitation was considered the origin of the Islamic traditional arts, functioning as a spiritual vibration that determined its modes and measures (

Burckhardt 1976, p. 45;

Nasr 1987, p. 17).

Meaning in the Arabic language was derived primarily through auditive intuition through a phonetic formula that traced the root of words to a simple three-letter verb that had physical, psychological and intellectual dimensions. This root verb expressed a fundamental action which made the identification of sound and act immediate and spontaneous, whilst the symbolism of the language resulted in meaning being revealed dynamically ‘in the act of becoming’ (

Burckhardt 1976, pp. 41–42). The ontological effect of this active mode inspired a contemplative state where unity was revealed through rhythm, which was described as, ‘A reflection of the eternal present in the flow of time’ (

Burckhardt 1976, p. 44). The balance of active and passive modes of perception was externalised in spatial sequences of Islamic sacred architecture in a similar manner as shown previously in relation to light, creating a continuous flow of alternating, harmonious experiences (

Ardalan and Bakhtiar 1973, p. 19). This interplay of static and dynamic modes was expressed architecturally in the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre through compositional variations that created visual highlights in a manner analogous to musical composition, where intonation, pitch and modulation expressed the meaning, feeling and attitude of the music (

Tonna 1990, pp. 182–97;

Helmholtz 2007, p. 370). It was also suggested that the musical poles of tone and interval corresponded to the rhythmic interplay of solid and void in the forms of Islamic sacred architecture (

Burckhardt 1976, pp. 45–46), which played an important role in the design of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre.

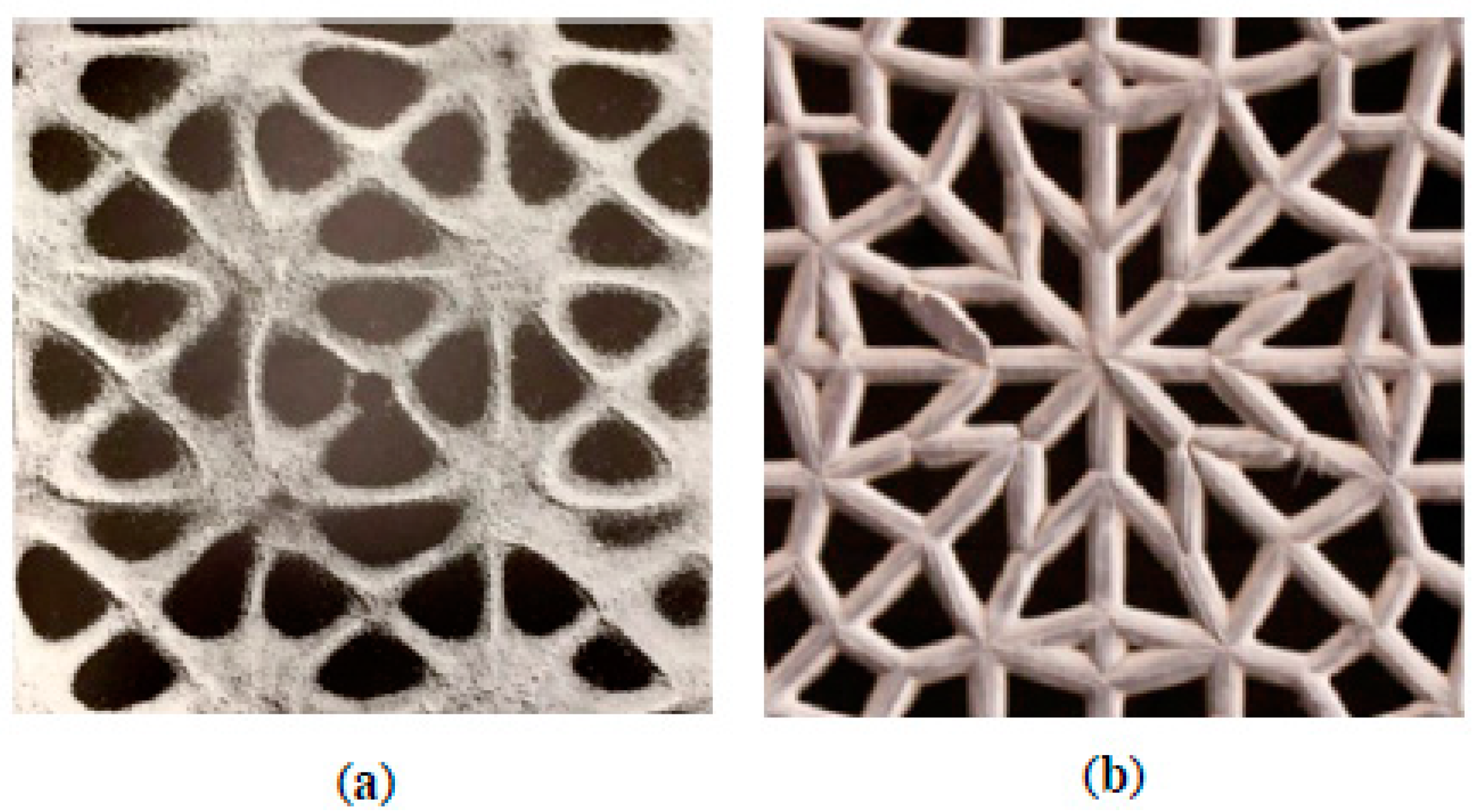

Correlations between properties of vibration and the structure of physical matter were examined by conducting experiments which demonstrated the physical effects of sound vibration on a variety of mediums (Hooke 17thC, Chladni 18-19thC,

Jenny 2013), resulting in three-dimensional geometric patterns that were found to be similar to the geometry observed in Islamic sacred spaces (

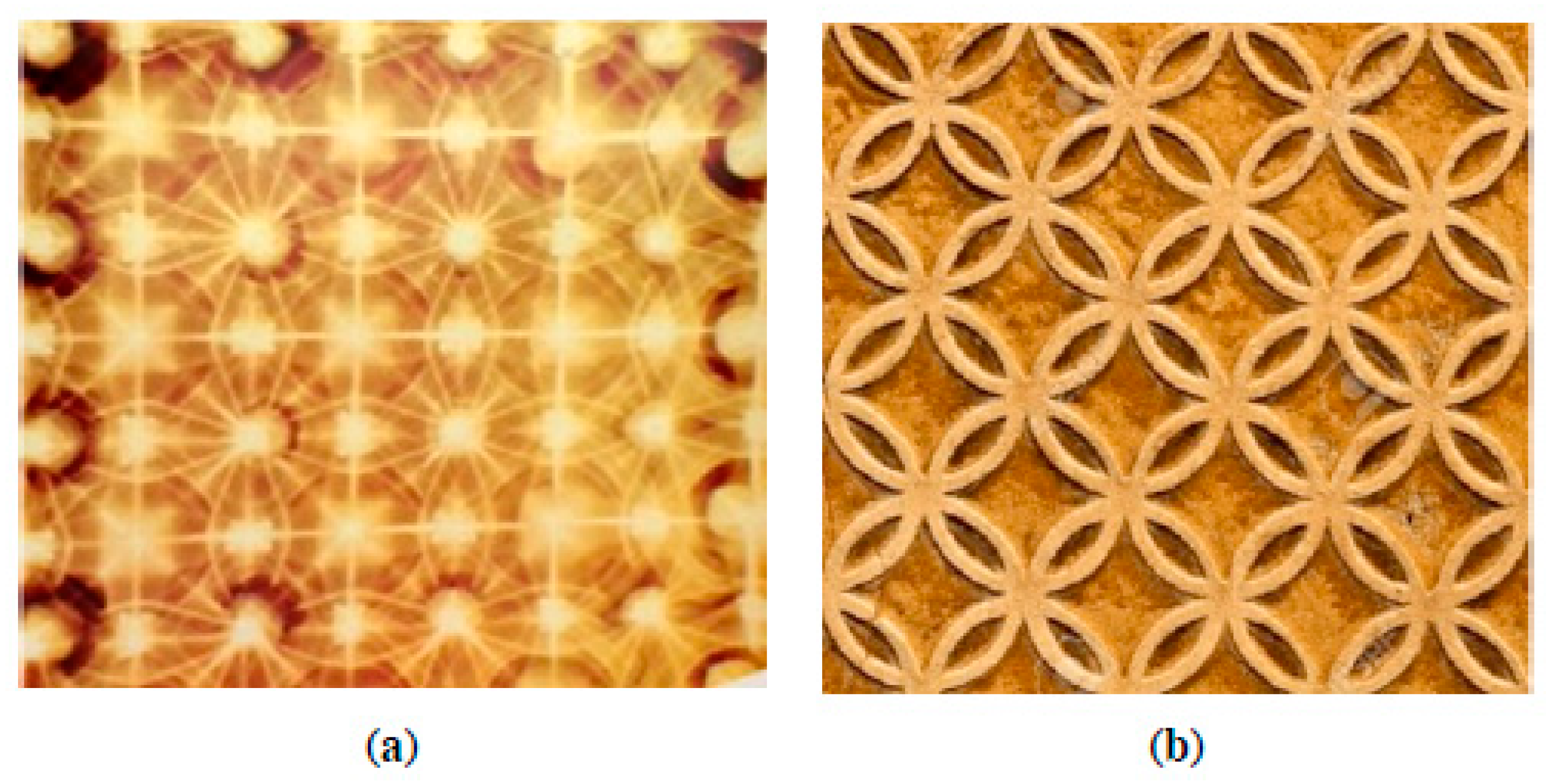

Figure 11). Light refracting through water showed sound vibrations that produced complex geometric lattices, which demonstrated harmonic qualities in number, proportion and form (

Jenny 2013, pp. 121–66) that also recalled examples of geometry from classic Islamic sacred architecture (

Figure 12). Other results proved that the ordering effect of sound influenced the air in empty space to such a great extent that solid matter began to display ‘anti-gravitational properties’, suggesting an underlying unity between sound vibration and energetic processes (

Jenny 2013, pp. 141–46) (

Figure 13). The results of these experiments raised further questions around how sound vibration and energy may affect matter, form and space in designs that approach sacred space as a ‘container’ for Divine energy.

At the opposite end of the continuum, silence was seen as an important aspect of spiritual experience. Silence has been described as the ‘void’, the transcendent power at the root of every sound and at the source of all sacred art, which recalled the principle zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen). Macrocosmically, the relationship between sound and silence symbolised creation unfolding from the Divine Essence. Microcosmically, silence related to the periods before birth and after death and, similarly, the void denoted pure being (

Nasr 1987, p. 163). Silence also related to the Sufi principle ‘being in the world but not of the world’, which described a state of unity with silence in every living moment (

Rasool 2003, p. 53). Becoming aware of this aspect of silence in private spiritual practice and as a source for spiritual creativity was an important aspect of the transformed approach to architectural practice that was developed.

These understandings of the transformative nature of sound and silence as part of an integrated, multi-sensorial and intuitive experience of space were particularly significant in the design of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre, where audible recitations of the Quran are performed, as well as silent Sufi practices. Translating the experience of the silent practices in the design involved creating spatial sensibilities that attempted to cultivate a state of inner quietude and centeredness. Rather than focussing only on the acoustic design of the physical space, the design concentrated on creating architectural forms in proportional harmony with the sacred words of the Quran using geometry. This was an attempt to align human microcosm and macrocosm through an integrated experience of space that preconditioned one’s awareness of the hidden realm (bātin) that potentially inspires an experience of Tawḥīd (Oneness).

Sound in the design of classic Islamic sacred space was found to be both quantitative, in providing an effective acoustic environment for the auditory activities taking place, as well as qualitative in its symbolic and ontological function to activate the spiritual heart and transform the self. When integrated, they resulted in transformative spatial auditory experiences that reflected the principle zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen). Historically, acoustic designs were concerned with the perception of sound and the intelligibility of speech, primarily as a function of sound reverberation within particular spatial geometries and absorption or reflectivity of surface materials (

Abdou 2003, p. 39;

Elkhateeb and Ismail 2007, p. 109;

Ismail 2013, pp. 30–41;

Momin 2014). For example, in the Sultan Hassan Mosque in Cairo, the traditional geometric form of the mihrāb (prayer niche), composed of a semi-circular niche with a quarter-spherical top and amplified by the use of smooth and hard materials, optimised sound reflected from the imām’s (leader) voice back towards the congregation (

Ismail 2013, pp. 30–41). The perception of sound and intelligibility of speech throughout the space was successfully enabled, together with higher reverberation times, which inspired transcendent experiences that reflected the grandeur and majesty of the architectural space (

Elkhateeb and Ismail 2007, pp. 128–29) (

Figure 14).

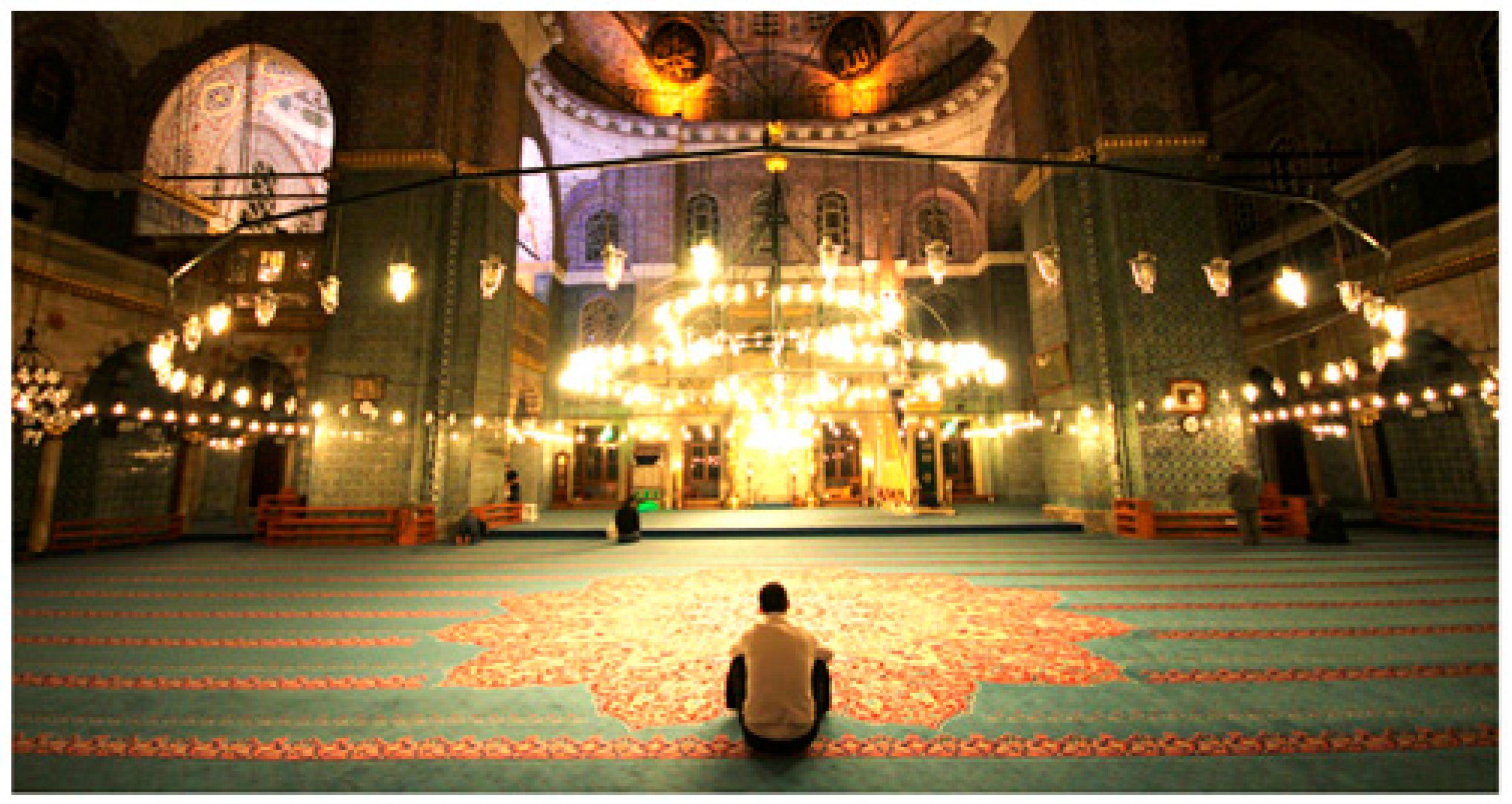

Studies of Ottoman mosques suggested that their primary function was to invoke spiritual experience through a spatial experience of Quran recitation, which resulted in an understanding of these mosques as universal, all-embracing art forms to be experienced with the entire sensorium (

Ergin 2008, pp. 204–21). This conception of multi-sensorial experiences of space was fundamental to the design of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre.

4. Creating the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre

The Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project constituted a search for a contemporary architectural representation of Islam and specifically the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi tradition in the context of contemporary British culture. The two-story building occupied a corner site on Globe road, a conservation area in Bethnal Green, a central London borough neighbouring the City of London (the financial district). It is located at one end of a Victorian terrace block comprising a row of commercial units at ground level with residences above, with the London Buddhist Centre located at the other end of the block. The building as a corner site was significant as it reflected the Arabic word for Sufi Centre ‘zawiya’ which literally means ‘corner’. The building’s location presented a principle challenge—to create an Islamic sacred space in the heart of a commercial urban environment. The commercial urban locality of the building and local conservation policies presented a tension between sacred/commercial and public/private space, which was interpreted as a manifestation of the principle zāhir wa bātin and played a crucial role in how the design developed. The project was entirely community funded, both from within the London-based group and from the wider Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī Order around the world. Progress of the project was, therefore, subject to incremental donations which meant the design developed gradually according to the availability of funds.

Spiritual aspects of the design were prioritised and viewed in light of the cosmological and ontological hierarchy of existence derived from the Quran. This hierarchy provided the basis for an integrated and transcendent view of sacred space and unlocked its metaphysical and ontological dimensions through symbolic forms and ritual acts. An understanding of space emerged associated with its ontological quality and transformative capacity as a symbol of wujūd (being, existence or finding), which became the primary aim of the design and the source of its meaning.

At the outset, the niyyah

20 (intention) of the project was clarified: to attempt to represent the spiritual essence of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi practices in the form of the building. Starting with this intention marked the beginning of a longer process of reflection on the relationship between creative practice and spiritual practice, as intention implied both a practical and spiritual purpose. Intention lies at the core of Islamic spiritual experience and is considered the first step taken towards experiencing Tawḥīd (Oneness), as it links human consciousness and actions with their archetypes, which enables the fulfilment of spiritual duties (

Arjan 2014, pp. 14–16). In relation to Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual practices, intention makes transformation conscious and harnesses intuition. During meditation, aspirants begin by stating an intention to turn their attention towards their heart, as their heart turns towards the Divine Essence. Here, intention is the force that enables transcendence, although attaining transcendent states was recognised to occur only through God’s grace and to rely on personal spiritual capacities. Activating the relationship between mind, spiritual heart and spiritual essence through contemplative practice, correlated with the role that khayāl (imagination) and the imaginal realm played in transformative experiences of sacred space.

The qualitative focus of the design relied on imaginal creative processes to give form to spatial sensibilities that were informed by desired spiritual states and which reflected the notion of spiritual transmission. The designs integrated the use of symbolism, geometry, light and sound to reflect a hierarchical cosmological and ontological order that was also reflected in the spatial order of the architecture and which shaped the physical forms. In this manner, the resulting design attempted to bridge physical and spiritual realms. It was through these integrating qualities that the transformative aspects of Islamic sacred architecture came to the fore.

By moving away from the conventional approach towards a transformed approach to creative practice, the design unfolded through a process of multiple transformations and intuitive insights, as though recalling an already existing archetypal state, which was seen to be somewhat analogous to practices of spiritual remembrance. The physical fabric of the building unfolded from an imaginal process by following an unfolding experience through space. The design developed the use of symbolic narratives specific to the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual path, which was demonstrated by a sequence of ground floor spaces which followed on from a hierarchical approach sequence into the building.

4.1. The Approach Sequence

The design of the exterior followed a hierarchical approach sequence, where the nature of the activities taking place within the building was gradually revealed, beginning with an expression of the non-Islamic context on the front facade and ending with an expression of the Islamic function of the building on the side façade. The main entrance was relocated to the furthest end of the building, away from the main road, rather than facing it, as would conventionally be the case. This choice was symbolic of the intention to turn away from the world towards the inner realm, retreating into sacred space that was set back from the hustle and bustle of the outside world.

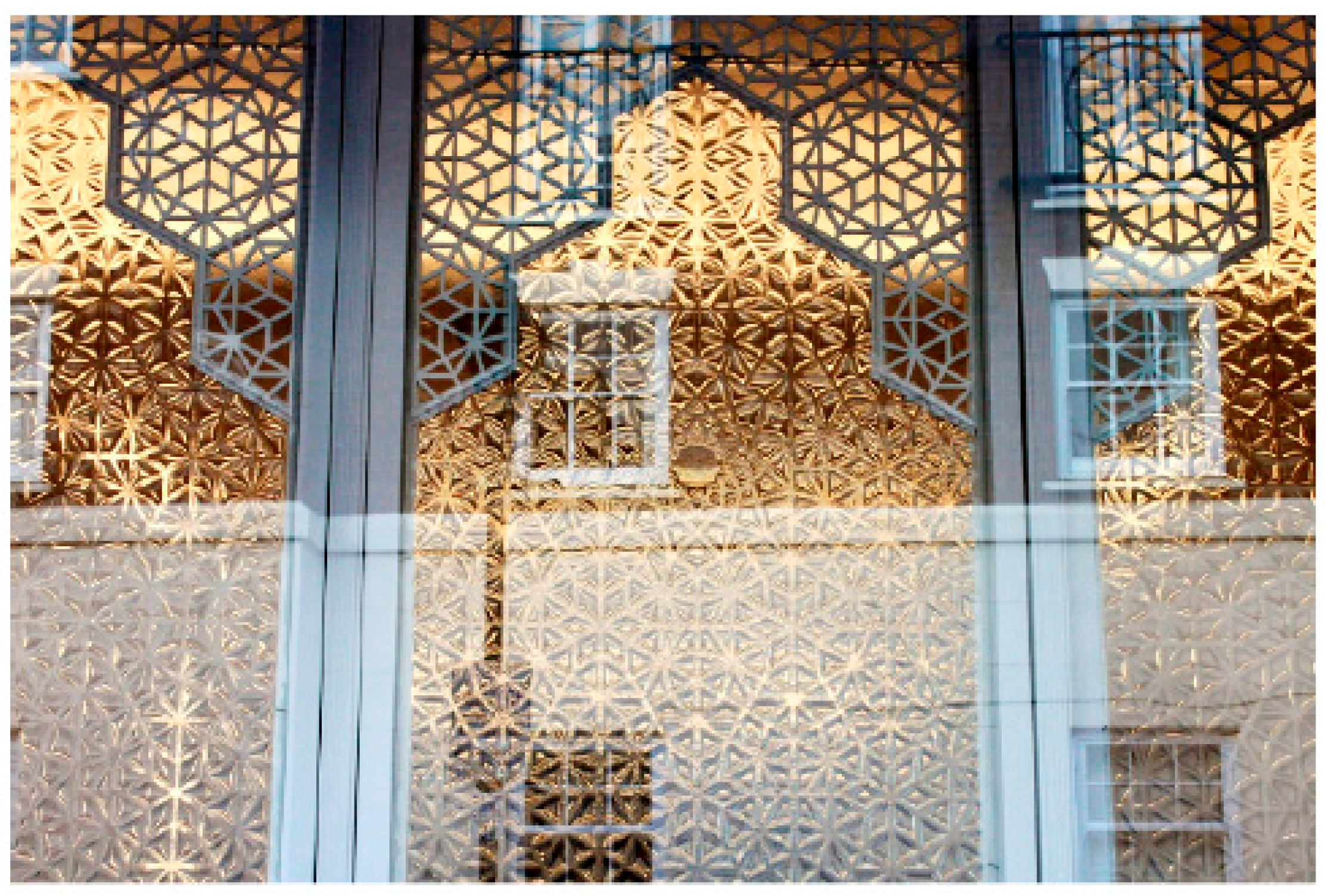

From a distance, the front façade emulated a Victorian timber-panelled shopfront in keeping with the street aesthetic. On nearing the building, geometric latticework embedded in the high-level fenestration became visible (

Figure 15). The geometric pattern that was used to inform the latticework symbolised the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual path and was used throughout the building. The latticework also symbolised the principle zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen) as light streaming through the voids of the geometric pattern represented fayḍ (Divine energy) transmitted through the laṭā'if (subtle centres of consciousness) from al-Dhāt (the Divine Essence).

Moving closer, the details of an ‘internal screen’ that was set back from the shopfront became visible, which mediated between the interior and the exterior and obscured the view inside the building. The space created between the two planes of the façade recalled the notion of the barzakh (liminal space) that mediates between the physical and spiritual realms. Symbolism, geometry and light were integrated using combinations of timber latticework and refracting cast-glass that incorporated the same geometric pattern, which by virtue of its symbolism sought to unlock the façade’s transformative quality, potentially inspiring more subtle states of being to begin to emerge, even before entering the building.

The internal screen directly represented the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Order and gave a fuller expression of the activities taking place inside, which reflected the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi doctrine of inclusivity and represented an aim of the spiritual practices to support aspirants in reconciling their inner and outer lives.

The process of designing the front façade encapsulated the tension between the commercial urban locality and the spiritual nature of the project. A solution was required that bridged specific needs for privacy and lighting in the meditation room facing the street with the limitations imposed by local conservation policies, which specified an ‘active-front’ in Victorian style.

21 The design that emerged allowed Victorian and Islamic architectural styles to visually but not physically merge, using layering, transparency and refraction (

Figure 16).

The hierarchical movement continued to the side façade, where a vertical garden represented a departure from the physical world (al-mulk) towards the heavenly realm (al-malākut), followed by an intermediate window that incorporated geometric latticework and culminating at the main entrance which directly represented the Islamic function of the building (

Figure 17). Developed collaboratively, the design of the main entrance was informed by shared understandings of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual practices, which constituted an important part of the transformed approach to practice that was developed. The entrance as whole symbolised the analogous relationship between macrocosm and human microcosm and the potential for spiritual ascension that have been described in terms of the arc of descent and the arc of ascent.

The calligraphy panel depicted a verse from the Quran which represented the inner realities of the Quran originating in al-jabārut (the spiritual world). The verse translated, ‘Lo! Those who ward off (evil) are among gardens and water springs. (And it is said unto them): Enter them in peace, secure’ (Quran 15:45–46) conveyed a view of Islamic sacred space as a gateway to the heavenly realm (al-malākut). The spandrel panel represented the five subtle centres of consciousness from the world of command. The elements of the entrance were framed by the border tiles which incorporated a geometric pattern informed by an underlying cosmogram that represented the hierarchy of existence (

Figure 18).

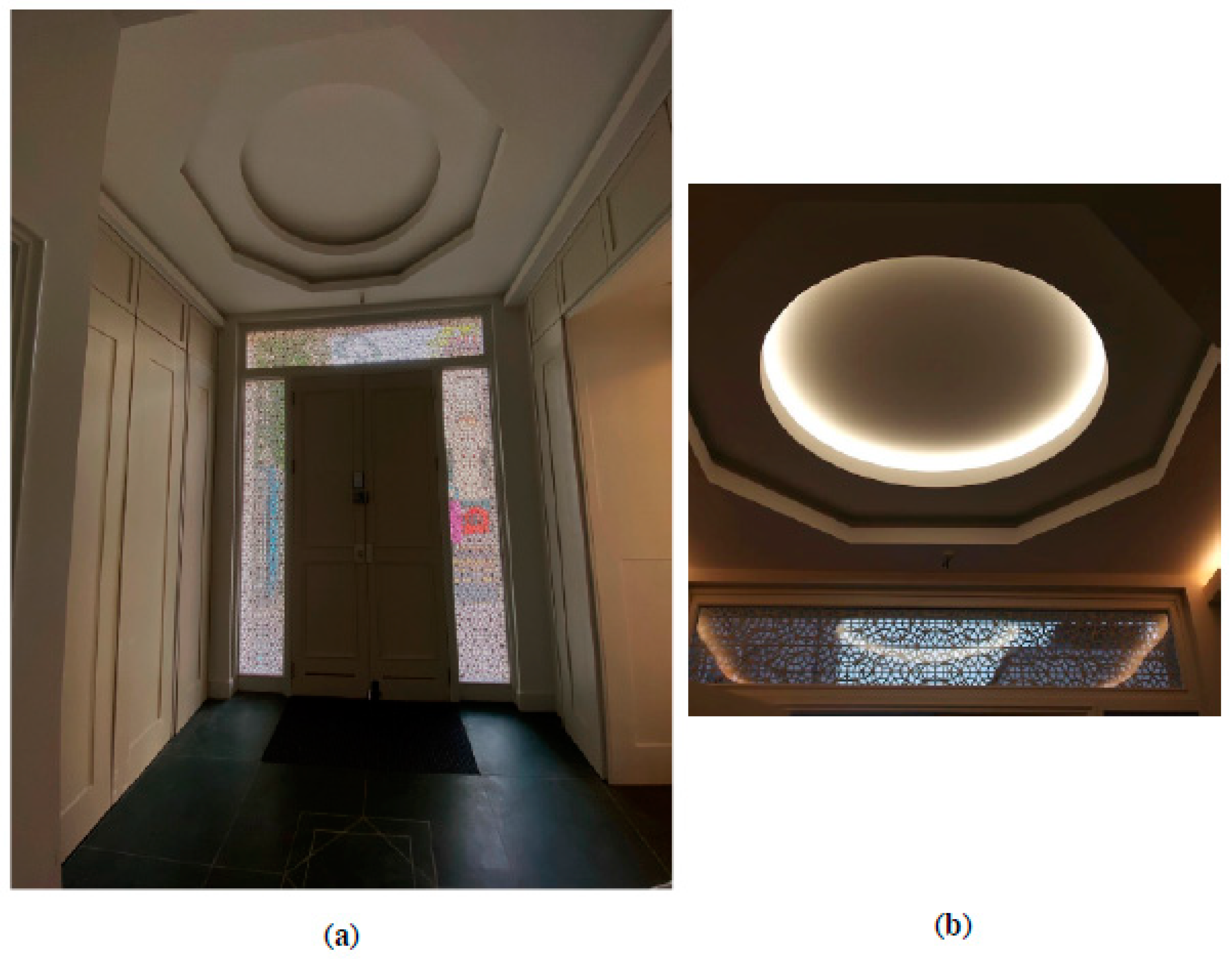

4.2. The Entrance Sequence

The experiential sequence of the ground floor spaces aimed to reflect the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual journey that enables spiritual purification and regeneration. The spatial sensibility of the entrance space incorporated integrated applications of symbolism, geometry and light that were inspired by the notion of the barzakh (liminal space) as expressed in classic Islamic sacred buildings (

Figure 19). The design aimed to inspire ontological shifts and to support acts of purification through haptic perception. In Islam, acts of purification such as removal of shoes and ritual washing (wudū) have a spiritual purpose. In the Quran, the removal of shoes symbolises the invocation of a state of humility, composure and respect and upholds the sanctity of the place, which precondition receiving spiritual bounties (

Al-Tabari 1987, vol. XVI, pp. 143–144 and vol. IV, p. 39).

22 Performing ritual washing has been observed to induce ontological shifts by potentially providing a sense of corporeal and psychological awareness that allows internal paradoxes to be resolved, which enables a sense of the sacred (

Hoyne 2009, p. 2). At higher, non-physical levels, it represents the beginning of spiritual regeneration (

Schimmel 1994, pp. 94–96). By considering the metaphysical and ontological dimensions of the symbolic acts taking place in the entrance spaces of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre, simple acts of purification became overlaid with added dimensions of ritual intention that cultivated the potential for transformative experiences.

In a renewed state of ritual purity, aspirants then enter the meditation space, arranged on two levels. The spatial sensibility, magnified by the monochromatic colour scheme, aimed to reflect the silent nature of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual practices. The bright space expressed the joy of communal prayer, inspired by historic examples and reflected the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi principle suhbat (companionship) that is considered essential for spiritual progress (

Buehler 2008, pp. 84–85).

Through a process of khayāl (imagination) that elucidated the desired spatial sensibility, the design details, materials, colour scheme, lighting and auditory nuances emerged as though an image was gradually coming into focus. The design aimed to balance practical auditory functioning with qualitative experiences of space by retaining the traditional semi-circular form of the mihrāb (prayer niche) as well as achieving higher reverberation times and utilising a system of geometric proportioning to inform architectural elements.

The meditation space reflected the principles tanzīh (transcendence) and tashbīh (immanence), where the loftiness of the lower-level space expressed transcendence which would potentially set the stage for a more intimate, immanent encounter with God through spiritual practice, reflected also by the positioning of wall lights at low level giving a human scale (

Figure 20).

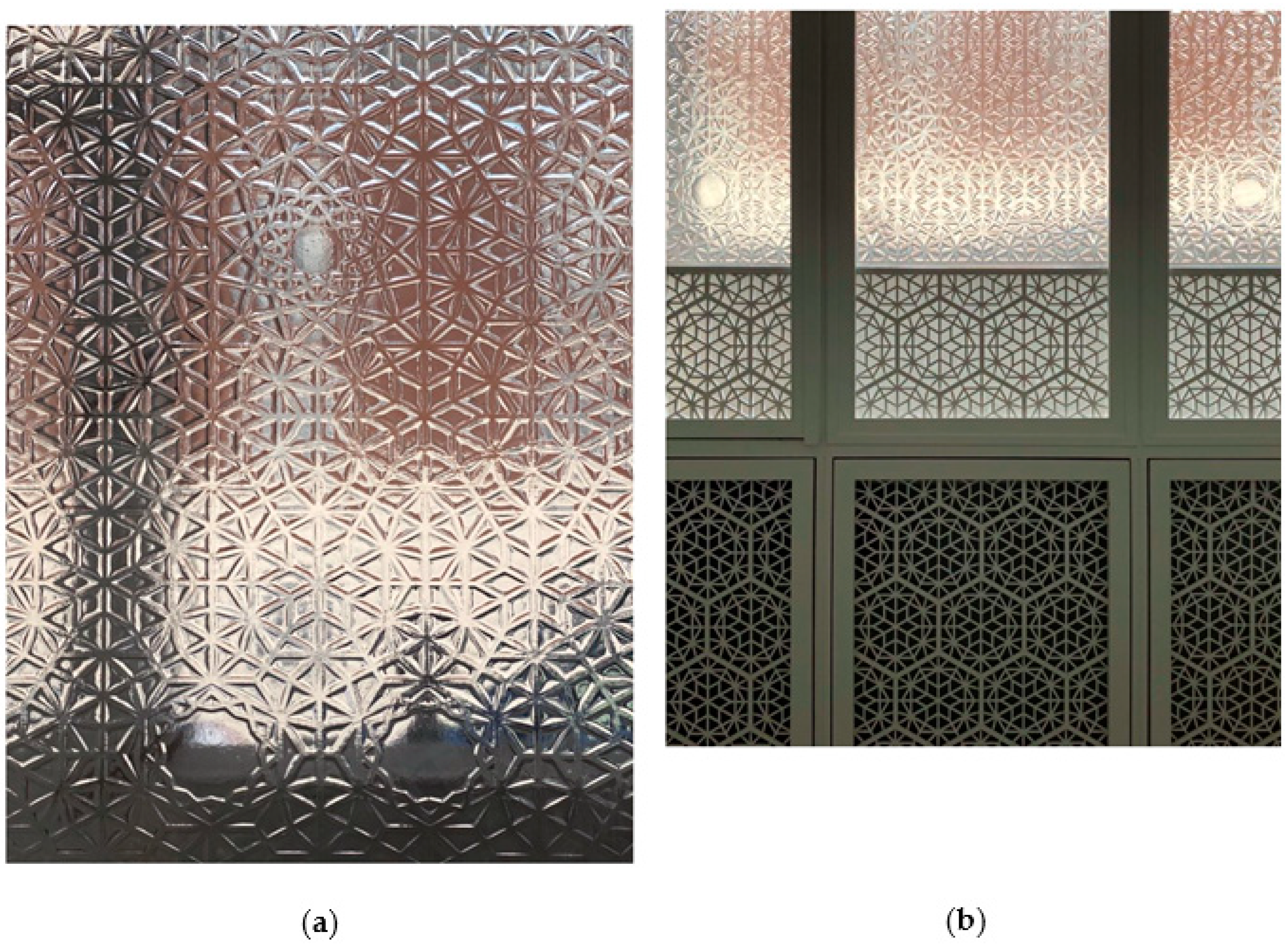

The design also aimed to create a dynamic, rhythmic quality through the geometry informing the internal screen which appeared to vibrate through the use of repetitive wall lights. On the other hand, for elements such as the prayer niche, the ceiling lighting designed according to an underlying cosmogram, the intermediate window with geometric latticework and the hand-drawn calligraphy panel that depicted the words that informed the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi practice of durūd (invocations of blessings on the Prophet (S) and his family) were intended as static visual highlights. These compositional variations were inspired by examples of classic Islamic sacred architecture that created visual highlights in a manner that was observed to be analogous to musical compositions that expressed various meanings, feelings and attitudes (

Figure 21).

The internal screen, which extended the full height and width of the space, constituted the main vista and the visual focal point of the building’s interior as a whole. It was inspired by the notion of alternations of light and darkness from the Quran and was divided into two parts; one above street level in cast-glass and one below street level in backlit latticework (

Figure 22). The space was transformed according to levels of natural or artificial light which also gave the screen the impression of a veil, which recalled the notion of the veil that separates human beings from God. The veil was intended to stimulate an aspirants’ khayāl (imagination) and to evoke an experience of the principle zāhir wa bātin (seen and unseen).

The geometric pattern that informed the internal screen was developed years earlier as a visual representation of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi spiritual path (

Nosyreva 2014). Over the years, the pattern became synonymous with the School of Sufi Teaching and was used in several other contexts. The pattern aimed to visually depict the dynamic process of spiritual progress through the latā’if (subtle centres of consciousness) drawing on diagrammatic representations of Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi cosmology attributed to key Shaykhs of the Order. It depicted the main laṭā’if as units incorporated within an overall hexagonal grid which formed a finite panel (

Nosyreva 2014, pp. 24–26).

In the context of the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi Centre project, the pattern was extended to become suitable for architectural use. The hexagonal grid represented the subtle centres of consciousness in a manner that recalled descriptions of them as ‘subtle fields’ (

Buehler 2008, pp. 111–13). The stars that lay within the hexagonal grid symbolised the manifestation of an individuals’ subtle centres of consciousness.

The vertical grid running through the centres of the stars symbolised the flow of fayḍ (Divine energy) that was previously described as a descending of lights experienced like rain, which enabled the arc of ascent (

Buehler 2008, pp. 117–18). In this orientation, the stars were static, which represented the passive state of the aspirant awaiting blessings during meditation. When the pattern was used in the design of the latticework that was incorporated within the external fenestration, it was rotated, with the lines now running horizontally, which symbolised the state of latent possibility. In this orientation, the stars were dynamic, reflecting the intense effort required to pursue the Sufi path and to transcend the worldly realm (

Rasool 2003, p. 16) (

Figure 23). An alternative interpretation focussed on the diagonal grid which intersected at the centre of each star, which was interpreted as the union of vertical and horizontal aspects experienced in the spiritual heart as Tawḥīd (Oneness).

The process of receiving guidance from the spiritual realm through meditation, which harnesses intuition, was represented by the translucency of the upper part of the screen that mediated a view to the outside world. The lower part of the screen represented the courser physical realm with the intermediate panel between them representing the imaginal realm as barzakh that separates the physical and spiritual realms whilst reflecting both of their attributes (

Figure 24). This functionality of the screen and the symbolic interpretations of the geometry encapsulated the correlation between sacred space and spiritual experience and exemplifies the process of ta’wīl (spiritual interpretation).

5. Reflections on Practice