1. Introduction

In a recent article, Didier Pollefeyt reflected on the worrisome observation that the Catholic education offered in primary schools does not seem to survive the growing or maturing of children in secondary schools: young children who would seem to be successfully raised in the Christian faith have lost this faith by the end of their education trajectory (

Pollefeyt 2021). For all concerned with the project of the Catholic school and religious education, this is a serious issue—if Christian identity construction of the young Christians in Catholic schools in the long run fails, and even seems to function counterproductively, this may invalidate the project of Catholic education altogether.

After shortly presenting Pollefeyt’s analysis and proposed solution (to complement/interrupt all-too-positive theologies with theologies of vulnerability and responsibility), I will argue that a more fundamental analysis is to be made to solve the issue at hand. A theological recontextualisation in dialogue with the current context will show us that the interruption of (all too) positive theologies urges these theologies to change from within, into theologies of interruption. In this regard, I will propose that only theologies fostering a negative theological sensibility at their very core, and thus cultivating a theologically motivated radical critical hermeneutical consciousness, may offer both a contextually plausible and theologically legitimate answer to the problem at hand.

In order to make this point, after summarising Pollefeyt’s argument, I will analyse the current context of detraditionalisation and pluralisation, and point to the challenges it poses for all identity construction (including Christian identity construction) which is to be interrupted by difference and otherness. Afterwards, I will shed light on the precise way in which the dynamics of negative theology fosters a radical critical hermeneutical consciousness at the heart of the Christian faith, challenging any attempt at solidifying it within closed, self-securing narratives, and thus opening up these narratives to be interrupted. I will illustrate my point with a short reflection on the Gospel of Mark as a Gospel for our times. In the conclusion, I will apply the insights gained to the project of the Catholic dialogue school in order to prevent the counterproductive outcome of self-securing identities.

2. “Too Much Good Is Bad”: Why Catholic Education Seems to Fail

The Christian identity construction, which is fostered in primary schools, does not remain a long-term success and even leads to entrenched secularisation by the end of secondary education. This conclusion is drawn by the KU Leuven-based theologian, Didier Pollefeyt, from the comprehensive empirical research he has been undertaking for more than 15 years now in Australia (

https://www.ecsi.site/au/, accessed on 1 February 2022). Empirical data show that this happens in two ways: first, youngsters end up as unbelievers, or at least score highly on factors of literal unbelief; and secondly, they also mark high on degrees of relativism. In any case, the end result of 12 years of Catholic religious education is strong disaffiliation from Church and the Catholic faith.

How, then, does one explain that, at the end of their school careers in the Catholic education system, the Christian faith seems to have lost almost all of its plausibility and attractiveness for young people? Pollefeyt hypothesises that there is a causal relationship between the way in which religious education is handled in Catholic primary schools and the massive secularisation that happens in secondary schools. In his analysis, it is the ‘mono-correlational’ bond between ‘all too positive’ theologies and positive psychology that leads to a kind of confessional values education, encompassing what happens in primary school and turning it into a rather undisturbed ‘safe Catholic haven’. The effects of such a kerygmatic approach fade away once children enter secondary school. “The ‘kerygmatic balloon’ of the Catholic primary [school] gradually deflates, so to speak, in the course of secondary education. The monological use of ‘dialogue’ is

interrupted by other voices. When teenagers and adolescents open up to the complexities of the world around them and accumulate real life experiences, the traditional and predictable mono-correlation of ‘one’ question with ‘one’ answer is broken” (

Pollefeyt 2021, p. 7). As already mentioned, this happens all the more since, in primary schools, this monological approach is combined with a unilateral link between an exaggerated positive theology (a too-literal belief in an all-good and -powerful God) and positive psychology (fostering basic trust, well-being, and a positive attitude to life): “When the ‘balloon’ deflates and the reality of life pours in, with all its complexity, multiplicity, ambiguity, difficulties, suffering, and pain, it is as if the Catholic faith no longer can be a relevant dialogue partner. Religious faith is something naive and sweet for children. [...] Students graduate from Catholic education as well-educated, responsible, and reliable citizens, but they have left faith behind in (primary) school. The presupposition is mistaken that creating solid basic trust in young people using positive psychology, ‘Gospel values’, and Christian virtues would

automatically lead to the creation of convinced, robust, and resilient adult Catholic believers in the long term” (

Pollefeyt 2021, p. 9). What is more, such an approach is highly counterproductive, and the more successful it appears to be in primary education, the higher the price paid in secondary education. In other words, fostering a literal belief in an overly benign God, within a harmonious and safe Catholic haven offering high levels of certainty and undisturbed by the outside world, does not develop into a mature and reflective symbolic faith. Instead, it seems to end up in either relativism, or worse, literal unbelief.

As a solution, Pollefeyt advises, with regard to religious education, not only to link positive theology with positive psychology, but also to theologically deal with disturbing themes such as conflict, negativity, and otherness by invoking theologies of vulnerability and responsibility (Levinas). “Theologies of vulnerability and responsibility stress that God remains hidden from direct human experience. Human beings primarily can only meet the Other through their encounter with the human other (responsibility), or by being confronted with the ‘un-experience’ of God (vulnerability)” (

Pollefeyt 2021, p. 11). The otherness of God interrupts the ‘all too positive’ theologies. Both theologies of vulnerability and responsibility, Pollefeyt adds, “refer to religious experiences where people start looking for God in times and places where things seem desperate and ‘godforsaken’. […] In these negative moments, people feel an astringent desire for fullness of life and divine redemption—but they just cannot see or experience it. It is as if, in that crucial moment in their lives, God has been ‘eclipsed’” (

Pollefeyt 2021, p. 12). Religious education should enable youngsters to (also) deal with these kinds of interruptions from (their) Christian faith.

In his article, Pollefeyt acknowledges that he does not develop this theological point in depth, as it is his purpose to reflect on the “pedagogical implications for Catholic school identity”. In this contribution, however, I will take it upon myself to engage in such an in-depth fundamental theological discussion of Pollefeyt’s hypothesis. In doing so, I will radicalise his analysis and proposed solution, with the aim of showing that complementing positive theologies with theologies of vulnerability and responsibility will not be enough to deal with the problem at hand. I will argue that it is positive theology itself that must be interrupted and recontextualised. In order to make my point, I will refer to the new role the age-old tradition of negative theology may play in this regard, not as a complement to positive theology, but to change this theological approach from within.

3. Interrupting Christian Identity Construction in a Post-Christian and Post-Secular Context

In order to do so, I will start with the issue of Christian identity construction in relation to our contemporary current context, and how the category of interruption leads us to another way of framing such identity construction (

Boeve 2007).

3.1. A Post-Christian and Post-Secular Context Marked by Detraditionalisation and Pluralisation

When we characterise our current western religious contexts as post-Christian and post-secular, we must take into account that the ‘post’ in both terms does not mean a simple ‘after’. Christianity is still around, and the consequences of the secularisation process are very visible in our societies. What is different, however, is that our relationship with both Christianity and secularisation has changed. This is also true for Christians in our societies: inasmuch as they are also a part of the current context, so, too, their relationships to Christianity and secularisation have changed—and thus also the way in which they construct their Christian identity today.

More specifically, the term ‘post-Christian’ refers to the process of detraditionalisation, which has changed our relationship with Christian tradition. As a matter of fact, detraditionalisation concerns all traditions, regarding their potential as resources for identity construction. All of them, Christian or not, have lost their self-evident nature. They still exist but are no longer self-evidently passed on from one generation to the next. Paradoxically, as resources for identity construction, they function post-traditionally. This implies that whoever holds to a tradition today does not merely grow into this tradition as a pre-given and unquestioned reality, but more than before actively chooses to belong to that tradition, being aware that there are other options available. As a matter of fact, detraditionalisation leads to growing individualisation: when identity is no longer a given, it becomes an assignment, something to be constructed. This holds particularly true for Christian identity construction today—when this identity is not consciously assumed, it is hardly acquired.

Analysing our context as post-secular implies that secularisation, as part of the modernisation process, has not resulted in a shift from a commonly shared Christian context to one that is generally secular(ist). In this regard, the secularisation thesis, holding that the more modern society has become, the less religious it remains (and the opposite), has not been proven right. Rather, we have shifted to a context characterised by (religious) pluralisation, with the secular(ist) position being a component of that plurality. As well as detraditionalisation, this pluralisation also constitutes the context in which the identity construction of students at school takes place.

3.2. Fostering a Playground for Reflexive Identity Construction

It is the purpose of (Catholic) schools to assist students in constructing their identity. Because of these processes of detraditionalisation and pluralisation, for all concerned (Christian or other), identity has become much more of an assignment. It is now a process of making choices (for identity is no longer self-evident or pre-given), dealing with insecurity (because there are always other choices questioning the choice one makes), and involving more reflexivity (answering the question of why one chooses this rather than something else). In the current context, a more reflexive identity construction at least requires the student to be able to cope with insecurity and otherness.

As secularisation does not lead to secularism per se, the same holds true for detraditionalisation, individualisation, and pluralisation—processes (-isations) should not be confused with their possible outcomes (-isms); in this case, these include nihilism, individualism, pluralism, and relativism, amongst others. The same must also be observed when it comes to the counterreactions to these ‘-isms’, such as neo-traditionalism, fundamentalism, and ethnocentrism. All of the ‘isms’ are ways to cope with, or attempts to escape from, the changed reality to which the processes of the ‘-isations’ have led. Nevertheless, it would seem that responses to this reality are structured in binary ways: either nihilism or fundamentalism, either relativism or ethnocentrism. On a societal level, insecurity and confrontation with otherness seem to lead to opposite reactions, i.e., to dynamics of polarisation and identity politics. Even more so, the opposition itself seems to be constitutive for such kinds of identity construction.

Looked at more closely: both binary structured sets of reactions, in the end, do away with the challenge of otherness, as well as the insecurity that comes along with it for one’s individual and communal identity construction. Framed from the perspective of narratives (identity is constructed as a narrative, answering the questions of who I am, or where I come from and intend to go to), they are self-securing, closed narratives. They evacuate the challenge of otherness, either by exclusion or inclusion. Otherness is excluded in the case of fundamentalism or ethnocentrism, and often even scapegoated or made the enemy. Identity here is secured by opposing oneself to the other. In pluralism and relativism, precisely the opposite happens: otherness is made harmless because it is immediately integrated within the plurality of things in which we find ourselves. For the relativist position, otherness no longer really make a difference, but is more of the same, thus resulting in indifference. To be sure, both relativism and fundamentalism are the extremes of a continuum, in between which there are many positions possible.

As already mentioned, the intention of education may well be to foster playgrounds where young people are challenged and accompanied in constructing more reflexive, open identities. An identity construction that is able to cope with insecurity, difference, and the challenge of otherness is the kind of identity construction that might enable our students to find meaning in their lives and take up responsibility for themselves, others, and society. Through such identity, they can cope in a world that is marked by plurality, conflicts, and insecurity, as well as escape the binary opposition of both fundamentalism and relativism, not to mention all of the other truncated positions dominating cultural and political discussions today. The narrative structure of such identity, therefore, is not closed or self-securing. Rather, it is conceived of as an open narrative: on the one hand, able to account for one’s own choices, being conscious of their often-contingent nature, wrapped as they are in particular stories and traditions; and, on the other hand, coping with the challenge of otherness without reducing it to more of the same or scapegoating it in the function of securing one’s own identity. In other words, identity and its interruption by otherness foster a process of identity construction, which enables one to deal with the challenges of our contemporary context (

Boeve 2003).

3.3. Self-Securing Identities and the Catholic School

Let us now apply this to the case I presented above. Would it be appropriate to claim that all of the positions that have been empirically recognised by Pollefeyt, i.e., literal faith in primary schools, and either literal unbelief or relativism in secondary schools, are without exception examples of ‘too easy modes of identity construction’? Looking more closely at the literal belief in a benign God, coupled with positive psychology, it is precisely the challenge of otherness that is ruled out. The primary school as a safe haven is a school untouched by otherness. However, the resistance to it and the shifting of older students to the position of literal unbelief also represents a safe position, secured by absolute truth, in its own way a closed narrative without any hermeneutical consciousness. The same holds true for the position of relativism: formally equating all positions, and thus disregarding the difference one position implies for the other (in other words, giving up the confrontation with otherness that marks a situation of plurality), is also a self-securing position. In all three cases, identity construction results in forming a self-securing narrative, untouched by the interrupting challenge of otherness.

The question follows, then: which kind of Christian identity formation, considered with respect to the whole process of this formation (i.e., through primary, secondary, and tertiary education), may result in a Christian open narrative? This implies an identity construction that consciously embraces Christian particularity, while at the same time being open to dealing with insecurity, otherness, and interruption. An identity, in other words, that prevents one from falling into the pitfalls of self-securing narratives as they present themselves in the binary opposition of both fundamentalism and relativism.

This is the challenge for Christian identity construction at Catholic schools today: between relativism and fundamentalism, a Christian open narrative consciously opts for the best the Christian tradition has to offer, while at the same time remaining open to the particularity of this option and the challenge it engages of inviting a confrontation with plurality and otherness. Even more so, engaging the process of recontextualising in the present context may result in the consciousness that precisely the challenge of otherness, as well as the interruption of one’s own narrative by it, can be privileged places to rediscover what the Christian faith is about—God interrupting history. The latter statement indicates that this is not only a pedagogical question but especially also a theological one.

3.4. Thesis: The Interruption of All Too Self-Securing Christian Identities Leads to a Christian Identity Construction Engendered by Interruption

Therefore, this is the thesis I would like to put forward: the interruption of all too self-securing Christian identities leads to a Christian identity construction engendered by interruption. I develop this thesis in two steps.

(1) How well intended religious education at Catholic primary school may be, when Catholic schools teach an overly self-securing Christian narrative, students growing older cannot relate the Christian identity they have formed with the challenge of otherness, and develop identities marked by either literal unbelief or relativism. The way in which young children integrated the Christian faith is not only of no help to cope with otherness but precisely turns out to be just what is objected to in the positions of unbelief and relativism that are characteristic for older students. This is at least what the empirical data appear to teach us, that such religious education is counterproductive. This conclusion should seriously interrupt the way in which Catholic schools perceive their pedagogical projects, and the religious education that goes along with these. Teaching self-securing Christian narratives provokes self-securing counterreactions.

As already mentioned, identity construction framed within such binary structured, self-securing narratives is definitely not alien to our present-day context of polarisation and identity politics. The insecurity brought by otherness leads to reactions that are equally self-securing. This is obvious in the case of fundamentalism, scapegoating, extreme right-wing politics, populism, fake news, alternative facts, and victim-blaming. However, this is also true for the opposite reactions of relativism, nihilism, amoralism, high levels of individualism, etc. The polarisation between these positions shows that, at the societal level, we are not well-equipped at this moment to deal with the insecurity and challenges of otherness that identity construction, whether individual or communal, involves.

(2) However, at the present time, it is not the societal question that concerns us the most, but the theological one: is it theologically legitimate for the Christian narrative to be a closed, self-securing narrative? A self-securing narrative neutralising the interrupting challenge of otherness? Perhaps the interruption caused by the analysis of more than 12 years of Catholic education, witnessing the transition from literal belief to unbelief and relativism, may challenge Catholic schools to conceive of Christian identity construction differently, not only on contextual grounds but also on theological ones. The interruption of present-day religious education at Catholic schools then leads to a conception of Christian identity construction in which the interruption of otherness not only fosters more reflexive identities but also offers the opportunity to recontextualise the Christian faith. The result thereof would be a Christian open narrative, conscious of its own particularity and open to interruption when it risks becoming self-securing. This not only makes it is contextually relevant, preventing it from falling prey to the pitfalls of fundamentalism and relativism, but also theologically founded because it is in such interruptions that God might reveal Godself today in history.

As already mentioned, this exercise is not only pedagogically important but even much more theologically pertinent. That is the reason why I will argue that it is necessary to radicalise, from a systematic theological perspective, the proposed solution of Didier Pollefeyt. It is not enough to merely balance (all too) positive theology with theologies of responsibility and vulnerability—we must interrupt that kind of theology altogether. In the following sections, I reflect on how a contemporary retrieval of the tradition of negative theology, and the way this theological approach affects positive theology from within, may assist us in answering this question.

4. Negative Theology at the Heart of Christian Identity Construction

If (all too) positive theology is the problem, what then about negative theology as the solution? In the following paragraphs, I first express a double caveat regarding the nature of negative theology, explaining that it should be understood as a kind of radical critical hermeneutical consciousness at the heart of the Christian faith, before illustrating how negative theology from the very beginning, in Scripture and tradition, affects how Christians cope with God’s revelation in history. Finally, I will refer to some contemporary examples of negative theology, both in theology and philosophy, showing the affinity of our context with what is at stake in the negative theological tradition, while at the same time accentuating the particularly Christian approach stemming from such negative theological dynamics.

4.1. A Radical Hermeneutical Consciousness within Christian Faith

With regard to negative theology, a double caveat is necessary. First, it is not by counterbalancing (all too) positive theology with negative theology that its self-securing mechanisms are suspended. Even more so, it is a mistake to consider negative theology as just another strand of theology, next to positive theology. The dynamics of negative theology are something happening within all theology. It is what prevents positive theology from being trapped into all-too-positive theology. In other words, negative theology should be active at the heart of all Christian identity construction.

Secondly, it is also incorrect to reduce negative theology to merely a methodological maxim, as it tends to be understood in the ‘tres viae’ (three ways) of classical Thomistic theology. The first way, then, is the ‘via affirmativa’ positively speaking about God, as in: ‘God is good’. As a complement to the first way, the second way is the ‘via negativa’, holding that our positive God-talk, in fact, does not reach God; therefore, it is better to say, ‘God is not good’ because we misunderstand what being good for God is about, as we cannot use the human category of goodness to say of God that God is good. We, therefore, need a third way to approach God, going beyond the ‘via affirmativa’ and the ‘via negativa’, and this is the ‘via eminentiae’. In this third way, the scope of our language is enlarged, so that we may refer to God without enclosing God within the limits of our human language: ‘God is eminently good’. With the latter statement, we refer to God in a way that is ambiguous, as we predicate of God a goodness that is beyond the human understanding of goodness. Here, we touch upon a paradox to which we will have to come back: this third way of speaking works at the same time with that human understanding of goodness, in attempting to go beyond it.

Although negative theology is not just about the method, its methodological use reveals its fundamental theological intuition in the same way the mystical tradition—a tradition in which negative theology has been prominently present—has done. Negative theology, in this respect, stands for a sensibility of what Christian faith is about, a kind of spirituality that implies Christians are on their way to God but never reaching God. It is a kind of critical consciousness at the heart of the Christian faith, opening up the narrative from within, resisting attempts to fall back into self-securing, self-enclosing narratives.

Negative theology, therefore, does not abolish positive theology but radically changes it from within. In other words, it is the motor of a radical hermeneutical consciousness within the Christian faith. It interrupts (all too) positive theology, challenging it when it becomes too harmonious, too all-reconciling, and when it tries to escape from otherness, history, and the world by attempting to create a safe haven unbothered by what happens in the world out there. This motor was already active in the Old Testament and is later radicalised in the New Testament. Also, in the history of Church and theology, this radical critical hermeneutical consciousness appears in what has been recognised as the tradition of negative theology.

4.2. Paradigmatic Narratives from the Old and New Testament

To illustrate my point, I now shortly elaborate on some paradigmatic narratives bearing witness to the negative theological dynamics at work in the understanding of (Jewish) Christian faith, respectively from the Old and New Testament.

In the book of Exodus, God’s revelation on Mount Sinai goes hand in hand with the prohibition of images. In Exodus 3:14, we read: “I’m there for you”, followed by Exodus 20:4, “you will not make idols of me”. The reason why no images can be made is to be found in Exodus 20:2, “I am the Lord your God who has led you out of Egypt, the house of slaves”. The prohibition of images is intrinsically linked to the fact that God liberated God’s people from slavery, out of Egypt. God’s revelation does not lead away from history but offers a theological interpretation of it. Christian faith, therefore, is the attempt to read history from God’s perspective. That, precisely, is why no images can be made of God, because God can only be a God active in history and in the world when God is radically different from history and world. Reading history from a God’s eye perspective runs the risk of ideological distortion when human beings really think they can take that epistemological position. When that happens, they make an idol of God: God becomes enclosed in history, limited to one particular reading of it—in the case of Exodus, God is turned into a “golden calf” (Exodus 32).

A double sensitivity is revealed by the event of Exodus: (Jewish–) Christian faith in God is about what happens in history and the world, but its understanding of God’s relationship to history and the world cannot be contained in history and the world. Only a God who is different from history and the world, and whose difference is respected at all times, can be active in that history and the world. Whenever Christians think they have a stable, unproblematic position to interpret history as such, let alone to condemn it, at that very moment they have lost the God’s eye perspective. Even more so, at that time God reveals Godself as a God who interrupts such idolatry. It is not by constructing self-securing, enclosing narratives but by the struggle against such narratives in the name of God, that Christians respect God revealing Godself in history and the world. Respecting God’s difference leads to interrupting narratives when they are self-enclosing. As a matter of fact, this radical critical hermeneutical consciousness has not only epistemological consequences (no images) but also political ones (interrupting history), because self-securing narratives, excluding otherness, make victims in the end.

Also from the New Testament, we learn that Christ cannot be contained in the images and interpretations we use to bear witness to what the Christ event stands for. The Emmaus story (Luke 24:13–33) is a fine example of this. It is through the narratives and interpretations of narratives that the two disciples learn of the Christ event (24:27: “beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he expounded unto them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself”), but whenever they think they understand and sense the fullness of the event in the breaking of the bread, in that moment, Christ disappears. The two disciples cannot take hold of the event, they must go back to continue the story, to tell the story to the others. A similar, and even more telling illustration is presented in the transfiguration narrative, available in all three of the synoptic Gospels, when Jesus, together with three of his disciples, goes onto Mount Tabor and “was transfigured before them; and his garments became glistering, exceeding white, so as no fuller on earth can whiten them” (Mark 9:2–3). The language itself here hints at its own limits when it refers to a whiteness whiter than white to describe the transfigured colour of Jesus’ garments. Moses and Elijah, representing the Law and Prophets respectively, join their company, revealing the culmination of what is foretold in the Old Testament in the person of Jesus Christ. Not really knowing what he says, according to Mark, Peter then proposes to build three tents, after which a voice from heaven reveals Jesus Christ’s identity and the event abruptly ends. The attempt of Peter to hold on to this moment of revelation (by building three tents and staying on top of the mountain) is in vain. They have to go down again. The Ascension narrative also ends in the same way: “Men of Galilee, why do you stand here looking into the sky?” After the resurrection, the disciples experience that the resurrected Christ is the Jesus of history they accompanied before his death. But, once resurrected, this same Jesus of history can no longer be contained by history.

4.3. The Tradition of Negative Theology

It is a reiterated phenomenon in Church history that whenever the Christian narrative tends to close, at that very moment, there often emerges a dynamic within the church that opens up the Christian discourse. This dynamic, one could say, can be defined as a negative theological dynamic, an interruption of ecclesial or theological discourses when they become too self-securing and self-secured.

The tradition of negative theology sensu stricto bears witness to this. One of the more famous representatives of this tradition is the author named after Denys the Areopagite, the Athenian disciple of Paul from Acts (17:34), therefore known as Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita, who lived and worked at the end of the 5th century. Recontextualising the Christian faith in dialogue with the Neoplatonic categories of his day (Proclus), he left us, in addition to ten letters, with four books of which the last and smallest one is of special concern for our argument:

Mystical Theology. In this work, Pseudo-Dionysius deals with apophatic (or negative) theology and, in so doing, had a major influence in later centuries up to this day (

Carabine 1995). All the names and the language we use to speak about God is necessarily symbolic—they refer to God but never touch God’s essence nor make God knowable to us. All names and titles that are predicated of God—representations of the experiential world, such as sun, rock, water, wind; intelligible or conceptual names such as the good, one, beauty, truth, life, love; theological names such as Trinity, Father, Son, Spirit—are names referring to what is beyond them, beyond all naming. In the end, the negation of the name is truer than its affirmation. Therefore, Pseudo-Dionysius engages in a never-ending process of negating, starting with the sensible names and ending with the abstract conceptual names in order to speak about God; his intention is not the negating of God, but the affirmation of the impossibility of naming and conceiving God. In the negation, and in the negation of the negation, Pseudo-Dionysius attempts to evoke what is not permitted evocation through language. God is beyond affirmation and negation. To be sure, for Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita, this process is not just a method or a way of using theological language but is fundamentally linked to mystical experience.

This tradition developed further in the Middle Ages with mystical authors such as Meister Eckhart, Jan van Ruusbroec, Therese of Avila, etc. It is no coincidence that while theology is taught at universities, turning into a more rationally constructed discourse, mystical and negative theologies have become marginalised. Nevertheless, this has not prevented that such theologies occasionally interrupted, from the margins, the ‘all too positive’ theology at the centre.

4.4. More Recent Accounts of the Negative Theological Intuition

More recently, some theologians have shared similar negative theological impulses (

Boeve 2003, chp. 8). The American theologian and philosopher of religion, David Tracy, for example, reflects on the incomprehensibility of God (

Tracy 1994). This incomprehensibility should not be understood as something negative, because it is not based on a lack or insufficiency, but rather on the incapacity to deal with excess: the awareness of God’s ungraspability originates in the experience of God’s excessive love—there is too much of God, there is too much of God’s love. It is its transgressing abundance that makes us speechless. Our experience of human love may be very similar, as can be seen with the phrase ‘I have no words to tell you how much I love you’, which bears witness to excess rather than lack.

The German political theologian Johann Baptist Metz and the Flemish–Dutch theologian Edward Schillebeeckx speak about the hiddenness of God in situations of suffering and conflict. For Metz, this hiddenness is linked to the dangerous memory of the passion, crucifixion, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and portrayed at best in the cry for God at the Cross (

Metz 2006). Schillebeeckx, for his part, claims that God is not to be located within suffering, but in our resistance to it. God is to be found in the face of the victim, in the fact that we experience the suffering of the other as suffering. Our ability to recognize this suffering as suffering is our ability to see God hidden within the world (

Schillebeeckx 1989). These approaches are very much related to what Didier Pollefeyt referred to as theologies of vulnerability and responsibility. It is in engaging responsibility that God can be encountered. The parable of the Last Judgement (Matthew 25:31–46) offers a paradigmatic account hereof: even the ones who were saved, because they fed the hungry, clothed the naked, etc., did not know that they had encountered Jesus before he responded to them, that whatever they had done for one of the least of these brothers and sisters, they had done for Jesus. God’s hiddenness in history and the world is pre-eminent and is only revealed post factum by interpreting what happens from within a God’s eye perspective.

The British specialist in negative theology, Denys Turner, for his part, recontextualises the kernel of the mystical tradition, not as the awareness of the absence of God, but rather as the absence of the experience of God (

Turner 1995). God exceeds human experience. The French philosopher and theologian Jean-Yves Lacoste refers to the concept of liturgical experience in this regard, which he designates as a

non-expérience (and

non-événement). As a matter of fact, it concerns an experience that escapes from the experience of and in the world, an experience that does not occur without the world but at the same time tears it open and reminds one of the gulf between history and the Absolute (

Lacoste 1994). Liturgical experience is not simply an experience of God that resonates with our general human world of experience and lends cogency to our religious narratives and theories, an experience to which we can then appeal for religious truth claims. Precisely the opposite is true: such non-experience is characterised by perpetual ambiguity and is in need of perpetual interpretation.

Furthermore, the French Catholic philosopher Jean-Luc Marion bears witness to this negative theological intuition at the heart of all thinking and speaking about God, when he, following Heidegger’s crossing of the word

![Religions 13 00170 i001]()

to refer to what escapes ontotheological thinking patterns, literally crosses the word

![Religions 13 00170 i002]()

(

Marion 1982). In fact, in my account, the way Marion uses the crucifix not only bears witness to the consciousness that God never can be grasped, but also to the very particularity of such a negative theological attempt to overcome language: in the end, it is the word God that is crossed by a crucifix. We need language to refer beyond language, and our language changes in that process. At another place, Marion profiles his own approach as the realization of negative (or, better yet, mystical) theology’s fullest reach (

Marion 2002): Christian God-language is not grasped between the ‘saying’ and the ‘unsaying’ of what is proper to God, but involves a third way, going beyond ‘kataphasis’ (affirmation) and ‘apophasis’ (negation). This third way is radically different and hyperbolic, undoing language from its referential function.

4.5. Lessons from the Retrieval of Negative Theology in Contemporary Philosophies of Difference

A theological assessment of the retrieval of Christianity’s tradition of negative theology by contemporary continental philosophy underscores also our thesis that negative theology, rather than an alternative to positive theology, is to be conceived as a radical critical hermeneutical consciousness at the heart of all theology. Indeed, a lot of so-called philosophers of difference have rediscovered negative theology as a discourse strategy to refer to the other without undoing it of its otherness, a way of speaking about difference without hegemonically encapsulating it (

Boeve 2012). Negative theology allows them to decentre the modern subject, to criticise ideologies and unmask master narratives, to bear witness to religious pureness, to refer to otherness as escaping language and thought. For most of them, however, its rediscovery also turns itself against Christianity. Jacques Derrida, for example, writes that the negation in negative theology is not radical enough and is finally undone because, despite all negation, God remains affirmed (negation thus implies de-negation) (

Derrida 1987). Jean-François Lyotard unmasks the Christian narrative as the master narrative par excellence because it succeeds in re-narrating whatever otherness happens within the confines of its own narrative, thus undoing it of its very otherness. As the master narrative of love, by loving from the outset what happens in the event, Christianity seamlessly integrates the event in its narrative structure (

Lyotard 1983). Other philosophers of difference, such as Jack Caputo, turn to the tradition of negative theology in reaching a pure religious sensibility, ‘pure prayer’, uncontaminated by the particularity of religious traditions, in his case certainly also including the Christian tradition (

Caputo 2002). ‘Pure religion’, or ‘religion without religion’, strives to cherish that moment of undecidability or difference that is both underlying and forgotten in concrete religions. For all of them, moreover, it is especially the incarnation in Jesus Christ, thus God revealing Godself in a particular language and history, which inescapably aggravates the problem. Such incarnational dynamics very inescapably contaminate from the outset all attempts at respecting religious otherness, difference, etc. Richard Kearney, for example, is very outspoken in this regard: the messianic structure of the anteriority of otherness is to be distinguished from any particular messianisms. The Christological claims of Christianity are always already too confessionally partisan (

Kearney 2003).

At this point, one could conclude that these philosophical attempts to retrieve negative theology as a discourse strategy to bear witness to radical otherness all lead to discrediting the narrative dimension of the Christian faith, bound as it is to a concrete history, narratives, and their interpretation. In that regard, the philosophical retrieval forgets one of the two constitutive elements that characterise a Christian open narrative—it is not only about faith in God as the Other of history, qualified by the constitutive difference between God and humanity, but also about the inscription of the involvement of God with human beings and history, an involvement that can only be concretely shaped and read in the very particularity of history. Both these characteristics belong intrinsically together: they concern (a) God’s otherness, and (b) the way in which we come to know about God in the particularity and contingency of history. It is to these two elements that the living Christian tradition bears witness, in narratives and praxis, prayers and rituals, doctrines and reflections. Combined, they give rise to a specifically Christian critical hermeneutical consciousness. Christian faith does not primarily concern the human search for God but is ultimately a human answer to God in search of human beings. Faith, then, is the option to look at history and society from the perspective of this God and to interpret them accordingly. It is faith in a God who reveals Godself as and in concrete love—faith in the God who, as Love, becomes the key for reading the very particularities and contingencies of history.

The Christian negative theological intuition, therefore, implies that only in the all too concrete, in the all too historical, in the all too contingent—and in an interpretation thereof—does God engage history in an irreducible and definitive way, without, however, coinciding with it. Incarnation never implies the neutralisation or cancellation of the historical-particular in terms of the universal, or of the contingent-historical in terms of the absolute. The latter is always irreducibly inscribed in the former, without discrediting the former, but at the same time, without isolating the latter from the former. Only in the all too human is God revealed, not without it—only in the all too historical can Christians read God’s presence and activity.

God’s ineffability, witnessed to in negative theology, has nothing to do with vagueness, nor with something that leads away from the concrete. On the contrary, it leads immediately back to history itself. God as the Other of history is involved in it as determinate love, as a prophetic challenge to all to make visible God’s invisible presence and activity. In this regard, it is like the love between two human beings. Such love is not an indeterminate given. It is only realised and can only survive as something very concrete, tangible, and life-giving, inscribed in particular events and stories, even when the language of love cannot find the words to express it, and even when all determination ultimately falls short and never succeeds in grasping its mystery.

When engaging the Christian faith’s negative theological intuition, theology’s task is not to leave all language, narrative, or particularity behind, but to search for a kind of narrative that does not revert into a closed narrative structure. It should find a way of speaking where God does not simply confirm and secure the narrative but realises precisely the opposite: a narrative in which the God who can only be spoken of in the narrative, at the same time, and repeatedly, interrupts this same narrative. Thus, a narrative where God does not neutralise difference but makes the difference. A narrative that is constantly aware of the fact that the other is threatened with being forgotten, that tries at least not to forget this forgetting (

Boeve 2014). Such an open Christian narrative does not think of God in the centre, but from the margin; it sees God, not as the guarantee of its own grand narrative, but as the continual critique of this. Such an open Christian narrative challenges Christians in the name of the God who ‘makes a difference’, to ‘make a difference’, even when they are confronted with closed narratives or with narratives that have no regard for the other and make victims. This structure of interruption offers a fitting reading key for reading Jesus’ speech and actions, on the one hand, and Jesus’ life story, on the other, as interruptions on God’s behalf: narratives of sin, religious closeness, and death upon the Cross are broken open in the name of an interrupting God (

Boeve 2003, chp. 7).

5. A Gospel for Our Times: Mark’s Open Narrative about Jesus Christ

To illustrate my point more concretely, I now turn to the Gospel of Mark. I hope to show that the way in which this Gospel narrates about the trajectory Jesus follows with his disciples is marked by a constant interruption. In this regard, it is perhaps no coincidence that this Gospel has, in the course of history, been marginalised, often thought of as a poor summary of what the Gospels of Matthew and Luke express in a much more elaborate and clearer way, and is, of course, seen as being in no way comparable to the wisdom Gospel of John. Aldo in this case, one might say that it is often from the margin that interruption happens.

It is also worthwhile to remember that the Gospel of Mark was written in a time of upheaval and insecurity, when Christians really needed direction, shortly before or after the year 70 CE, at the time of the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem. Exegetes still discuss whether it was written in Rome, Syria, or Galilee, thus making it very difficult to speculate on the Markan community, the initial readers for whom the Gospel was written. Nevertheless, the perspective of the reader, and the way in which the reader is taken along in the Gospel narrative, offers an interesting point of access to the Gospel.

When asked whom Mark wants the reader to identify with, the answer is clearly the position of the disciples accompanying Jesus from Galilee up to Jerusalem (

Van Oyen 2001). At first, the disciples are portrayed quite positively, they are called, they receive private instruction, are made to be privileged witnesses of special events, i.e., the bread miracles, the storm at the lake, etc. However, as the Gospel continues, Mark portrays the disciples in a more negative way: they do not recognise Jesus, they do not understand his teachings, they are afraid, and they have little faith. In the second part of the Gospel, the portrayal of the disciples even gets worse—they not only fail to understand but resist Jesus. They are afraid of the idea of suffering and crucifixion; they fall asleep when Jesus asks them to stay awake with him. One of them is a traitor and another claims not to know him when pressed after Jesus’ arrest. They all flee in the end and leave Jesus alone.

Reading Mark’s Gospel as a Gospel for our times, we cannot start from the position of the all-knowing narrator. On the contrary, Mark challenges us to identify with the position of the disciples, to let ourselves be involved in what happens in the Gospel from the position of the disciple. In several instances, readers are pressed, with the disciples, to ask serious questions: who is this Jesus? What does it mean to follow him, to become a real disciple of Jesus? In the following, I point to two of the most telling instances through which Mark proceeds to make this happen: the messianic secret and the original, open ending of the Gospel.

(1) The reading key of the messianic secret very specifically sheds light on the difficult process of following Jesus and really understanding who he is and what he is about (

Lambrecht 1985;

Tuckett 1983). In Mark, whenever Jesus is recognised as the Son of God, the Messiah, he himself asks the disciples not to tell anybody else who he is. There is too big a risk of misunderstanding who Jesus is and what he is about—a risk that contemporary readers of the Gospel may also run.

This risk becomes very obvious in the incomprehension of the disciples at each of the three times after Jesus announces his suffering. (Mark 8:33: following Jesus implies suffering; 9:33–34: the discussion about the best place at the table; 10:35–37: who can sit at the left- and the right-hand side of Jesus). As readers, we are confronted with the reactions of the disciples to Jesus, which may reflect our own reaction, or at least are a warning to us that we are in the same position. The example of Peter in Mark 8 is particularly telling in this regard. He perfectly answers the question about Jesus’ identity: “you are the Christ”, upon which Jesus gives the strict order not to tell anyone about him, thus maintaining the Messianic secret. But why? We read the answer a few lines further because Peter seems to have missed the point when he recognised Jesus as the Christ: he protests Jesus’ announcement that the Son of Man is to suffer, resulting in Jesus’ famous ‘vade retro Satan’: “He rebukes Peter and says, ‘Get behind me Satan! You are thinking not as God thinks but as humans think’. He then calls to his disciples and says ‘If anyone wants to be a follower of mine, let him renounce himself and take up his cross, and follow me. Anyone who wants to have his life will lose it, but anyone who loses his life for my sake and the sake of the Gospel will save it’” (Mark 8:33–35).

Also, the transfiguration narrative, which I already presented as a paradigmatic narrative illustrating how the negative theological intuition is at work, pressing language to go beyond language in bearing witness to Jesus Christ, illustrates in two ways the risk of misunderstanding Jesus: first, the disciples accompanying Jesus are afraid of what they witness and Peter indeed does not know why he proposes to build three tents; and second, when going down from the mountain, Jesus warns them to tell no one what they have seen “until the Son of Man had risen from the dead”. After this, the disciples discuss what it would mean to rise from the dead.

(2) What happens when the Son of Man rises from the dead in the Gospel of Mark? Here again, we are called to identify with the position of the disciples. Most exegetes think that the Gospel of Mark ends at Mark 16:8, just before the appearance narrative we have in Mark (

Gnilka 1979). They have discovered that the (canonically accepted) last appearance narrative is written in a style different from the rest of the Gospel, and moreover, there is a tradition of manuscripts that present Mark’s Gospel with a shorter, different ending. What, then, do we read at the end of Mark’s Gospel? “On entering the tomb, they saw a young man in a white robe seated on the right-hand side. They were struck with amazement, but he said to them ‘there is no need to be amazed, you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has risen and is not here. Here is the place where they have laid him, but you must go and tell his disciples and Peter, that he is going ahead of you to Galilee, and that is where you will see him, just as he told you.’” Then the last sentence reads, “and the women came out and ran away from the tomb because they were frightened, saying nothing to anyone, because they were afraid”. According to exegetes, this is the last sentence of the Gospel of Mark, leaving us then with the question: what to do now? How do we think about this? How can we go into history, go into the world, go to Galilee where we will meet him? Mark’s Gospel does not end with a reassuring message, but with a challenge, with insecurity, with a lot of questions. So many questions, seemingly, that this original ending has not been maintained in tradition and a ‘proper ending’ has been added to the Gospel.

However, it is the original ending that challenges Christians not to make a self-securing narrative of their Christian faith. On the contrary, Christians today are in need of Markan spirituality. We are not to stay on the mountain, we must go to Galilee, into the world. It is in the world, with its joy and hope, and fear and anger, that we encounter God—most probably where we never would have thought to find God.

6. Conclusions: Interrupting Catholic Dialogue Schools

The project of the Catholic dialogue school is a response to the call for a new, contextually relevant, and theologically legitimate recontextualisation of the Catholic identity of schools in a post-Christian and post-secular context (

Boeve 2019). In a detraditionalised and pluralised society, its assignment is to foster a playground for an open reflexive identity formation, both for the Christians and others at school, as an alternative to the self-securing, too-easy answers of relativism, secularism, ethnocentrism, and fundamentalism. Only when the dialogue at school really engages with the interruption of otherness, this project may succeed in doing so. The least one can say is that the monological use of dialogue used to construct a self-securing Christian narrative—as analysed by Pollefeyt with regard to religious education in primary schools—resolutely stands in opposition to this.

Whether a Catholic school really constitutes a dialogue school depends on whether the dialogue in no way functions as self-securing and self-enclosing, but makes room for interruptions to happen. Accepting the current context of detraditionalisation and pluralisation as a new context to foster identity, dialogue offers a critical–constructive way to deal with plurality and to engage otherness in view of one’s own identity construction. In a context of religious and ideological plurality, the assignment of constructing identity is what binds us together in a common quest for identity, as well as what distinguishes us from each other. Despite our differences, we all have in common the challenge of dealing with these differences, even if our answers in doing so may be very different. Fostering a dialogical sensibility within the different identity constructions, as well as drawing from different resources and traditions, therefore, creates communality, not despite but from within our being different.

A Catholic dialogue school is Catholic in two ways. First, it is Catholic because it starts from a relational Christian anthropology and worldview which grounds the dialogue at school. Secondly, because, within the dialogue itself, the school brings the Christian voice into the dialogue from its own institutional identity. From our reflections on the radical critical hermeneutical consciousness at the heart of the Christian faith (its negative theological intuition), it follows that the Christians at school are not the self-secured bearers of that voice, but its primary addressees—challenged by it in the same way the disciples in Mark’s Gospel are questioned time and again by its interruptive otherness. The only condition allowing them to speak the Christian voice, is remembering that they are first spoken to by the Christian voice. The Christian voice puts their identity at risk, in the way accompanying Jesus does to the disciples in the Gospel of Mark. The Christian voice interrupts all too easy ways of securing identity, both from Christians and others at school.

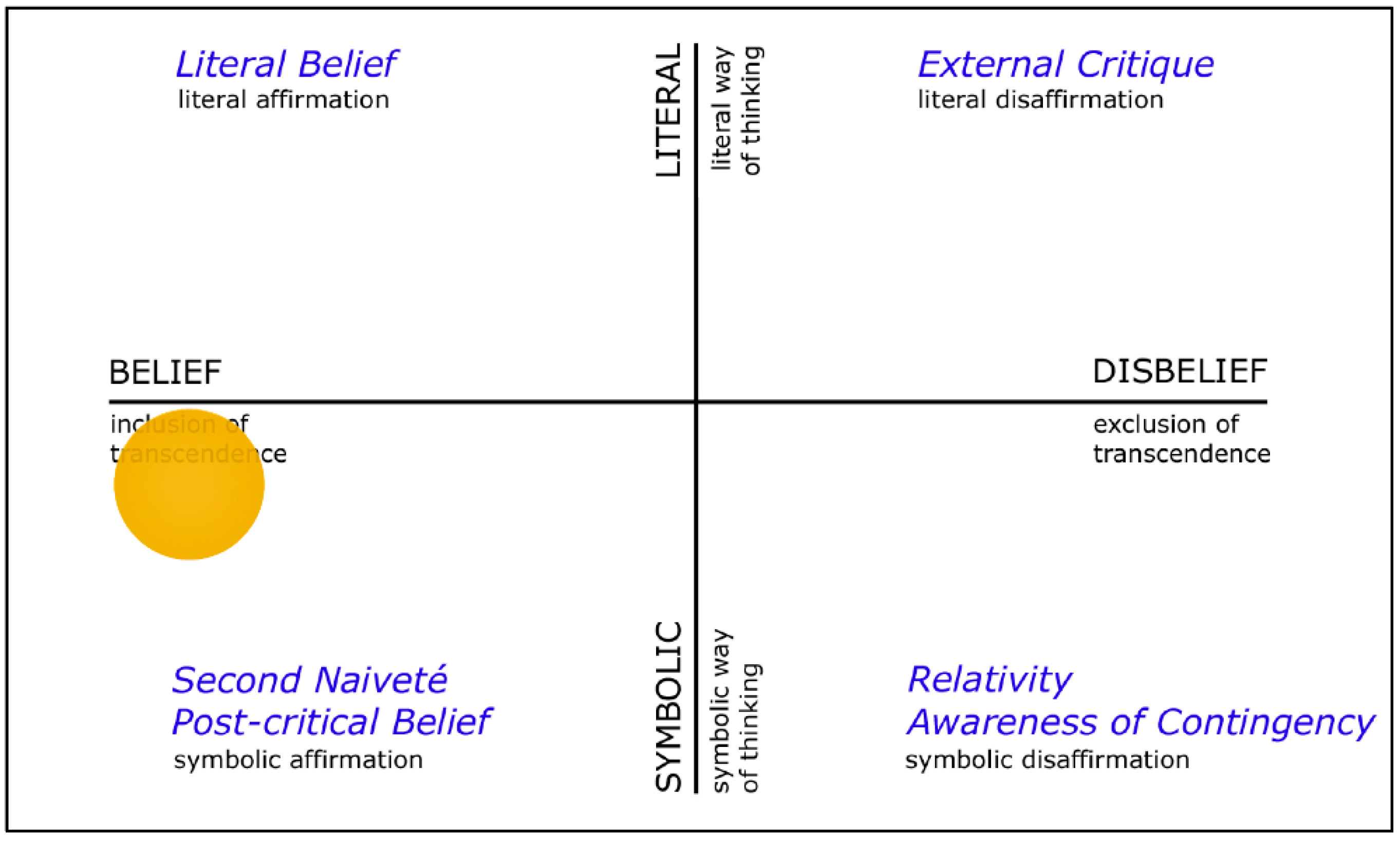

Before concluding with another paradigmatic narrative from the Gospel of Mark, I would first like to apply my theological conclusions to the ECSI-research with which we started this contribution. As seen in the post-critical belief scale, Didier Pollefeyt indicated the normative belief position with the so-called ‘golden dot’ (see

Figure 1,

Pollefeyt 2021, p. 2).

This golden dot is situated in between literal belief and post-critical belief, slightly at the side of the latter. In view of Pollefeyt’s own analysis of the implementation of the Catholic dialogue school in Australia and our own theological reflections presented above, we may seriously wonder whether this normative position is correctly situated. With regard to Pollefeyt’s analysis, the problem at hand is precisely that the shift from literal to post-critical belief is not realised in religious education, and that the faith position acquired in primary schools remains too literal. In view of the fact that youngsters in secondary education opt for the equally self-securing positions of literal unbelief and relativism rather than developing a mature, reflexive Christian (or other) identity, a more explicit downwards location of the golden dot is needed, resolutely situating it in the left-hand corner of second naivety and post-critical belief. As already mentioned, my plea to do so is not only based on pedagogical arguments but is first and foremost theological, assessing the radical critical hermeneutical consciousness at the heart of Christian faith, the negative theological dynamics at work in all theological language and thinking.

I conclude with a last paradigmatic example from the Gospel of Mark which very well illustrates what happens in dialogue, how identities can be challenged, and how God may reveal Godself in unknown, surprising, and interrupting ways: the story of the Syrophoenician woman asking Jesus to cleanse her daughter from an unclean spirit (Mark 7:24–30). This time it is not Peter and the other disciples who are interrupted, but Jesus himself is challenged by the voice of the other. Jesus’ original attempt to reserve God’s salvation exclusively for the children of Israel (“it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to little dogs”) is interrupted by the Syrophoenician woman’s response: “‘but little dogs under the table eat the scraps from the children”. Upon this, Jesus changes his mind and cures her daughter. The challenging question here is the following: where did God reveal Godself in this little dialogue? In Jesus’ voice, or in the Syrophoenician woman’s? Is it not the case that Jesus’ understanding of God’s salvation is interrupted, and that he learnt about the excess of God’s love, not be limited to one particular group but addressed to all? And is not the interruption by the other which called him to do so? If even Jesus can be challenged by meeting the other to broaden his own views and to include everyone in God’s love, how all the more should we?

to refer to what escapes ontotheological thinking patterns, literally crosses the word

to refer to what escapes ontotheological thinking patterns, literally crosses the word  (Marion 1982). In fact, in my account, the way Marion uses the crucifix not only bears witness to the consciousness that God never can be grasped, but also to the very particularity of such a negative theological attempt to overcome language: in the end, it is the word God that is crossed by a crucifix. We need language to refer beyond language, and our language changes in that process. At another place, Marion profiles his own approach as the realization of negative (or, better yet, mystical) theology’s fullest reach (Marion 2002): Christian God-language is not grasped between the ‘saying’ and the ‘unsaying’ of what is proper to God, but involves a third way, going beyond ‘kataphasis’ (affirmation) and ‘apophasis’ (negation). This third way is radically different and hyperbolic, undoing language from its referential function.

(Marion 1982). In fact, in my account, the way Marion uses the crucifix not only bears witness to the consciousness that God never can be grasped, but also to the very particularity of such a negative theological attempt to overcome language: in the end, it is the word God that is crossed by a crucifix. We need language to refer beyond language, and our language changes in that process. At another place, Marion profiles his own approach as the realization of negative (or, better yet, mystical) theology’s fullest reach (Marion 2002): Christian God-language is not grasped between the ‘saying’ and the ‘unsaying’ of what is proper to God, but involves a third way, going beyond ‘kataphasis’ (affirmation) and ‘apophasis’ (negation). This third way is radically different and hyperbolic, undoing language from its referential function.