The Construction of Sacred Landscapes and Maritime Identities in the Post-Medieval Cyclades Islands: The Case of Paros

Abstract

:1. Introduction

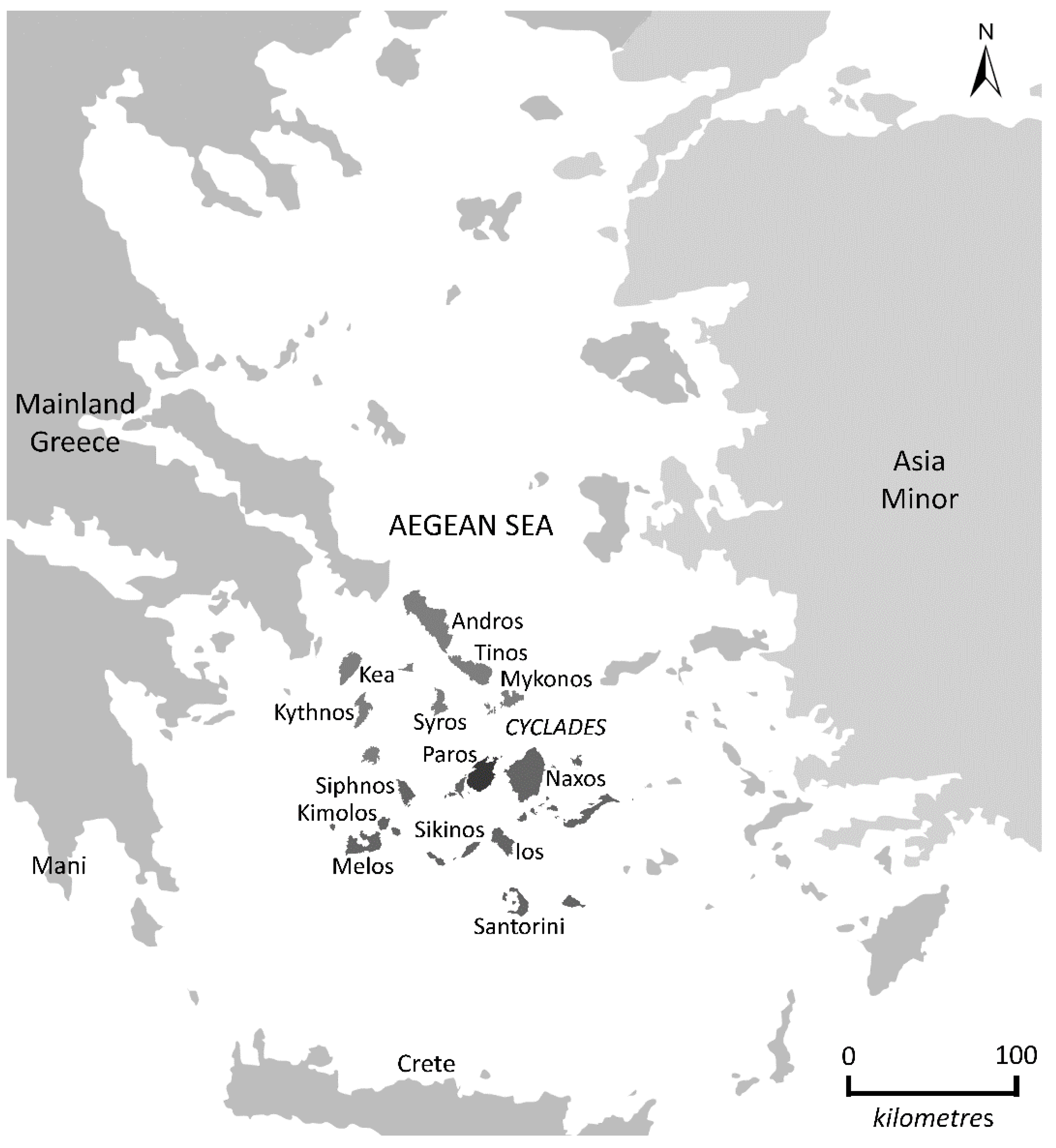

2. The Cyclades Islands: A Special Historical Reality

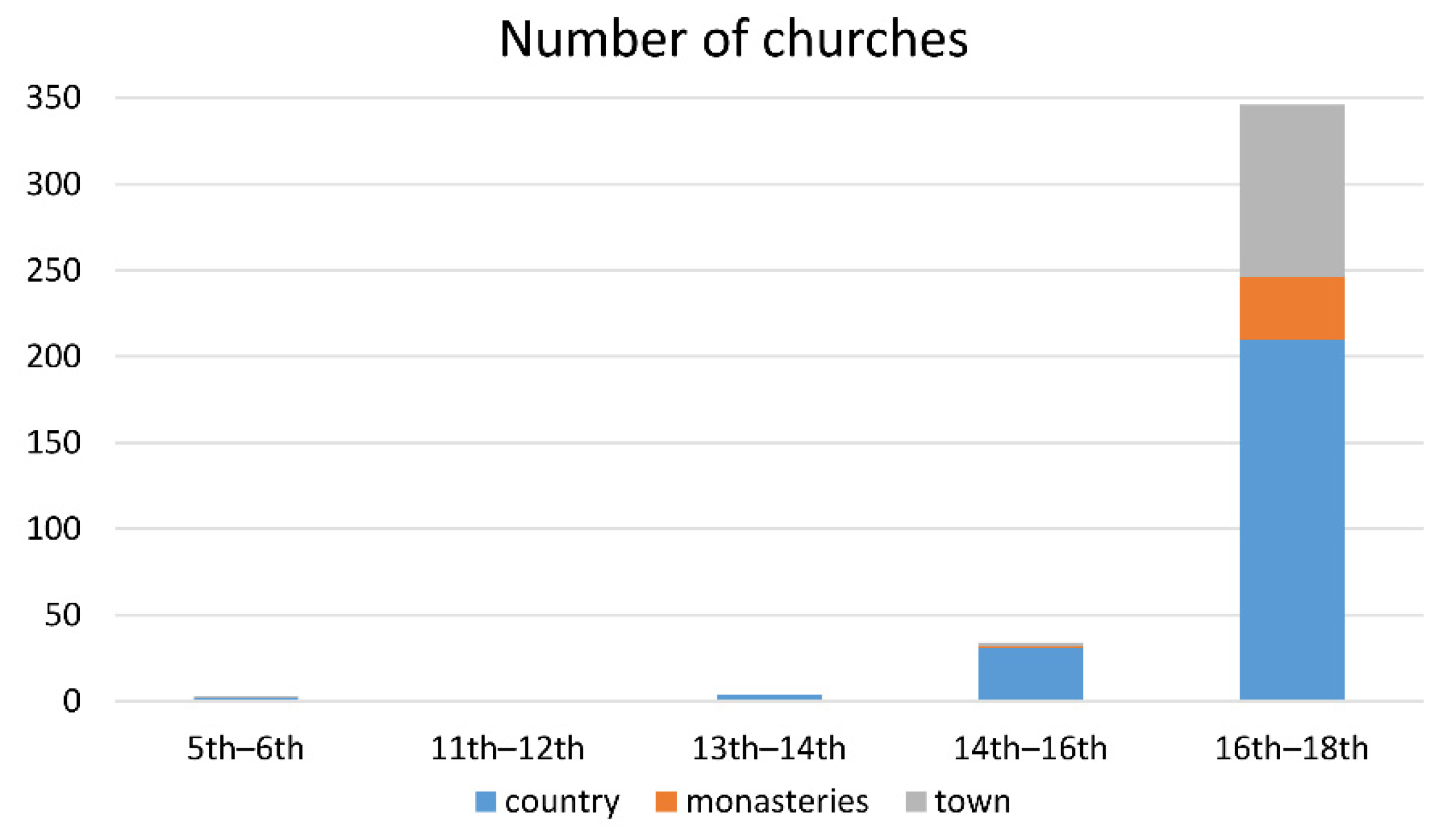

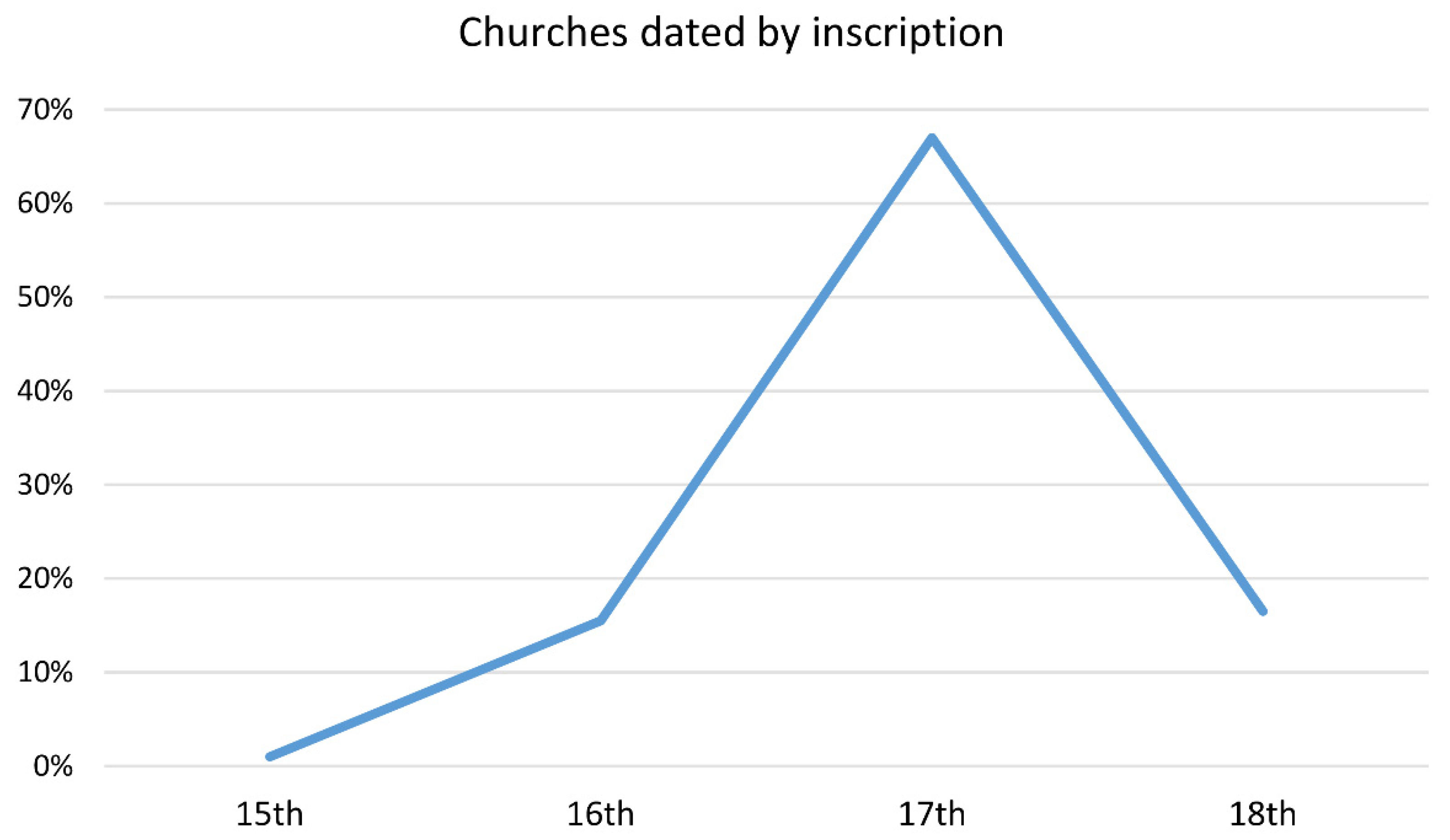

3. The Post-Medieval Churches of Paros

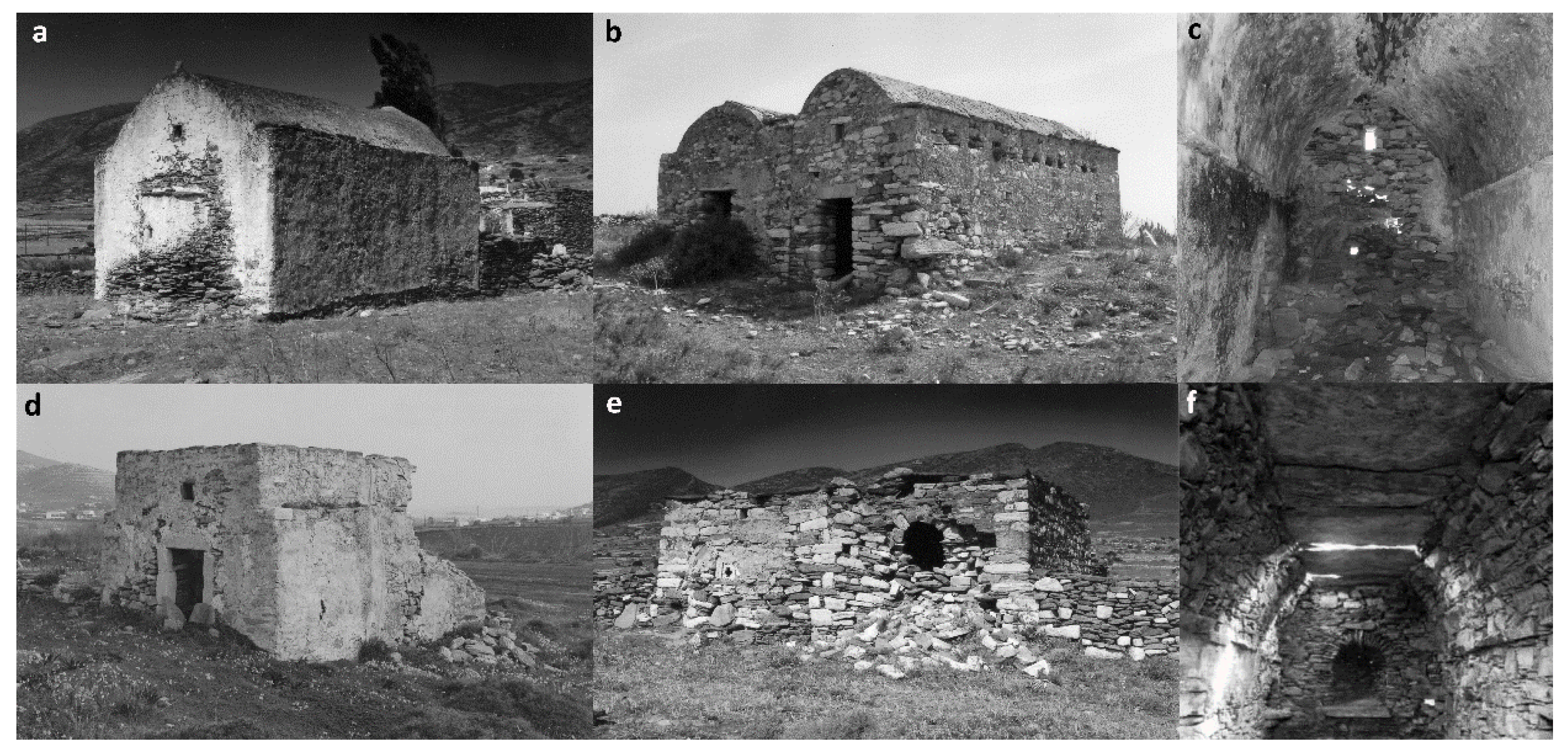

3.1. Churches with Vaulted Roof (Barrel Vault and Pointed Barrel Vault)

3.2. Churches with Pseudo-Vaulted Roof

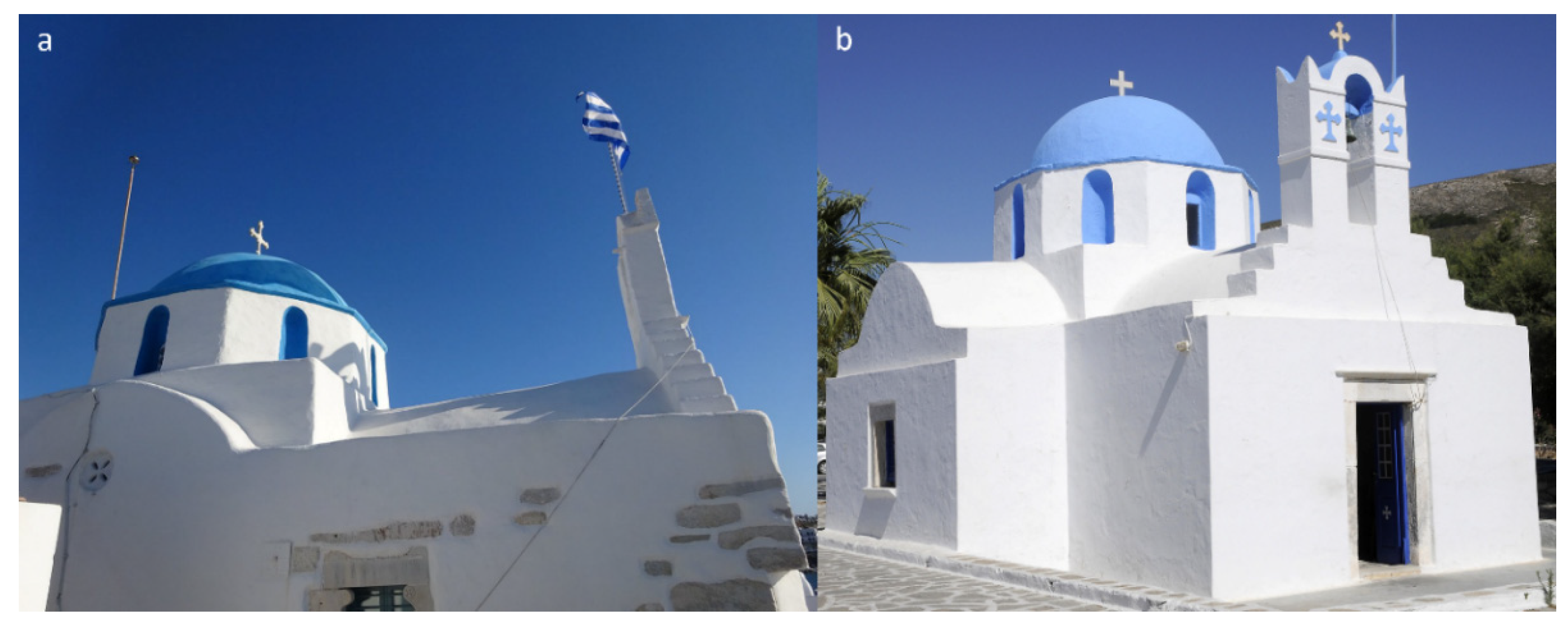

3.3. Churches with Dome (Single-Aisled, Free Cross and Cross-in-Square)

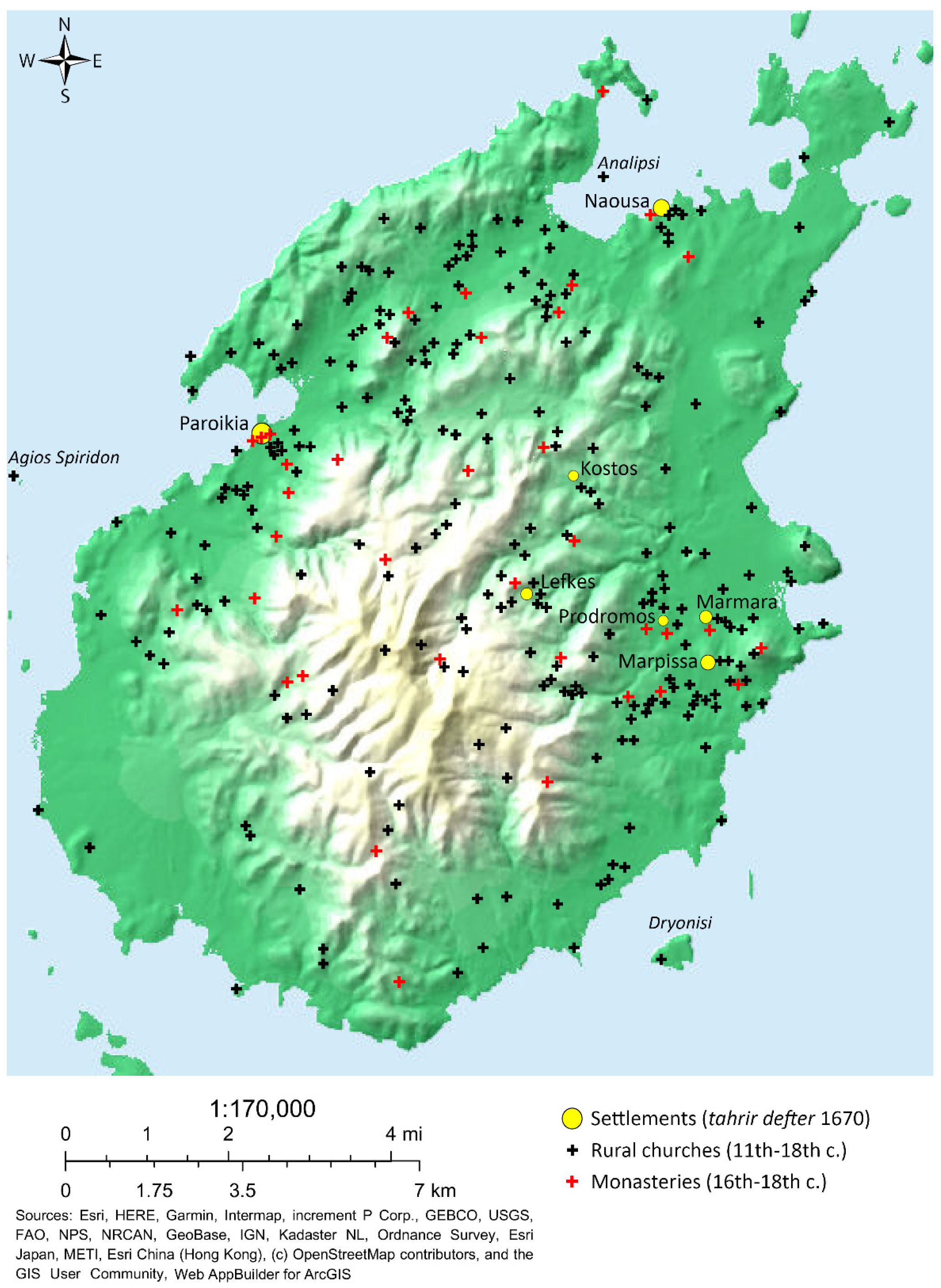

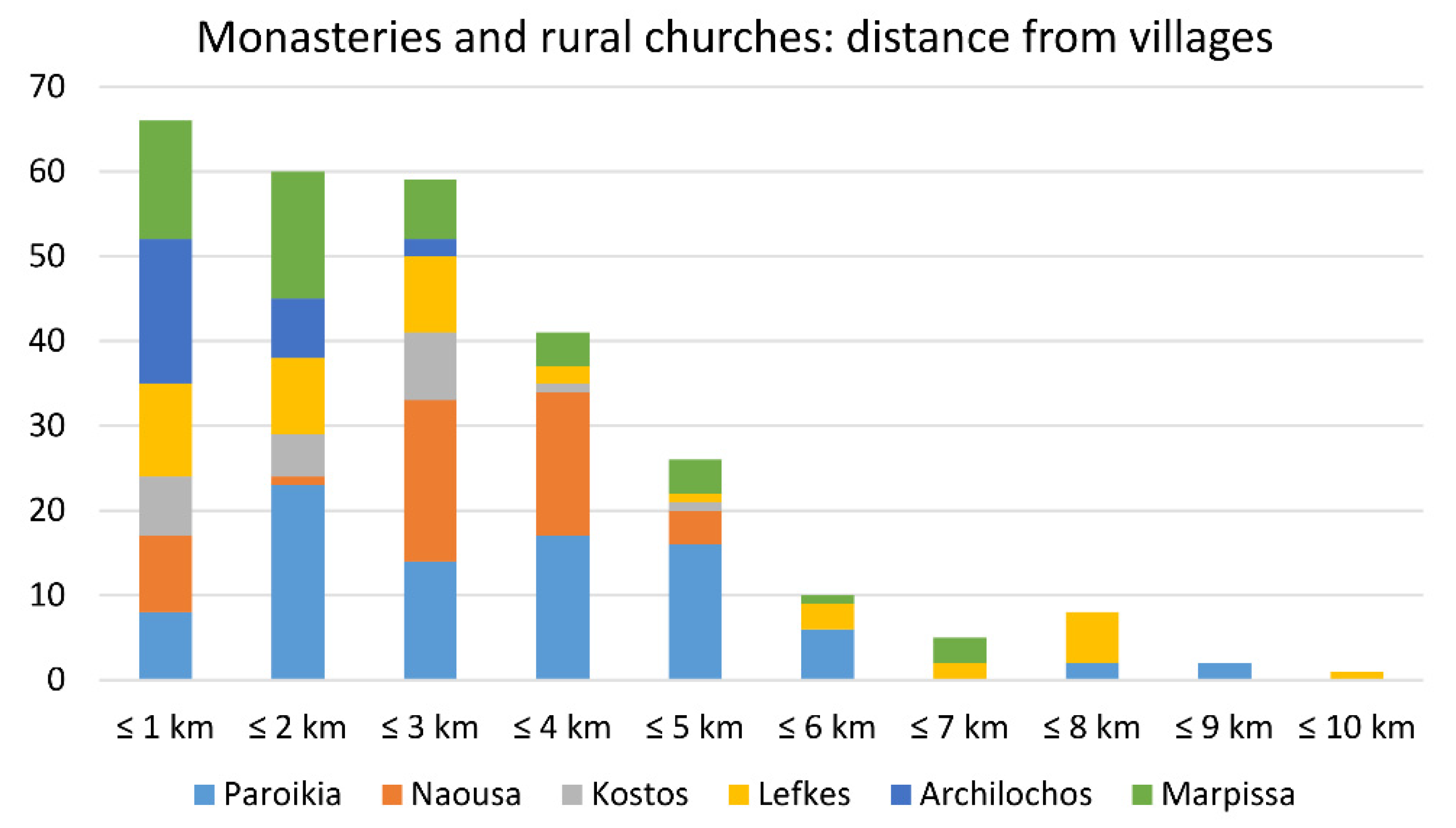

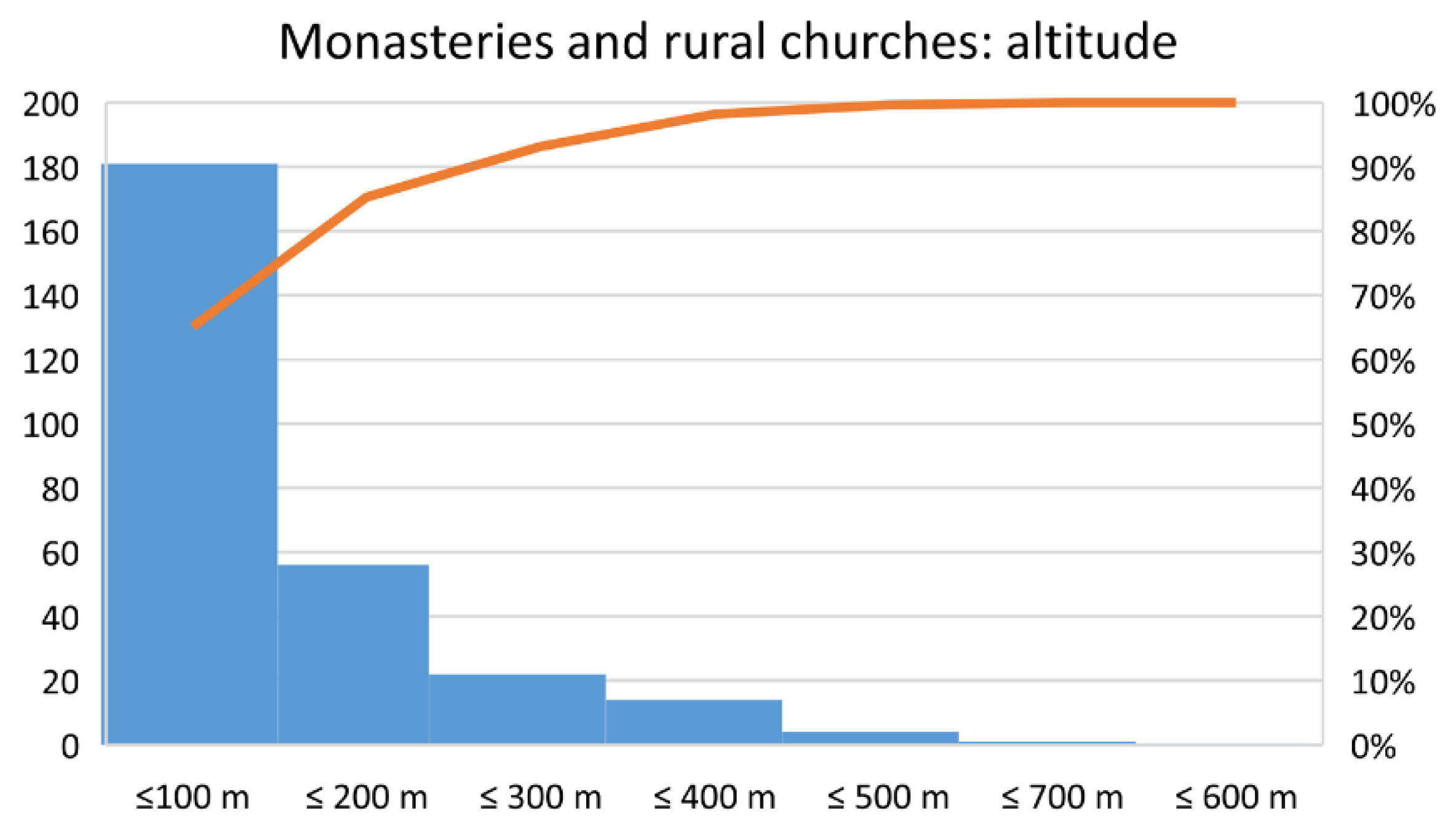

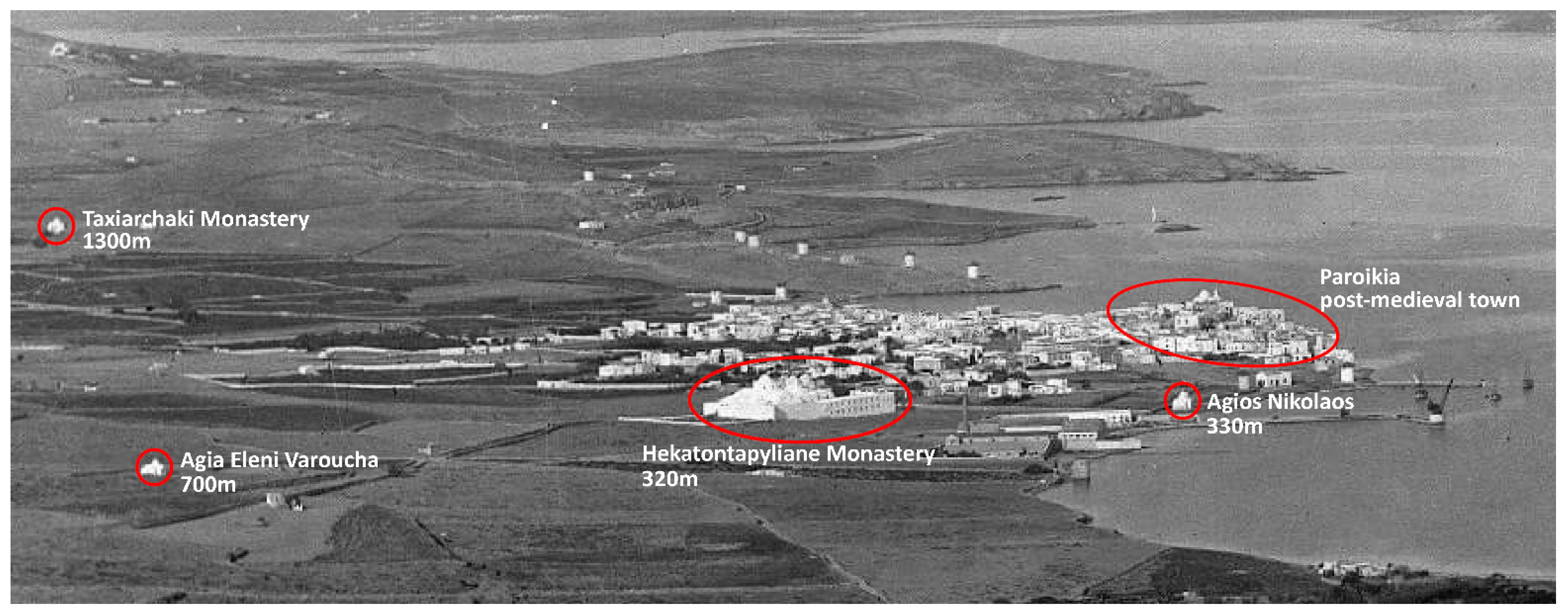

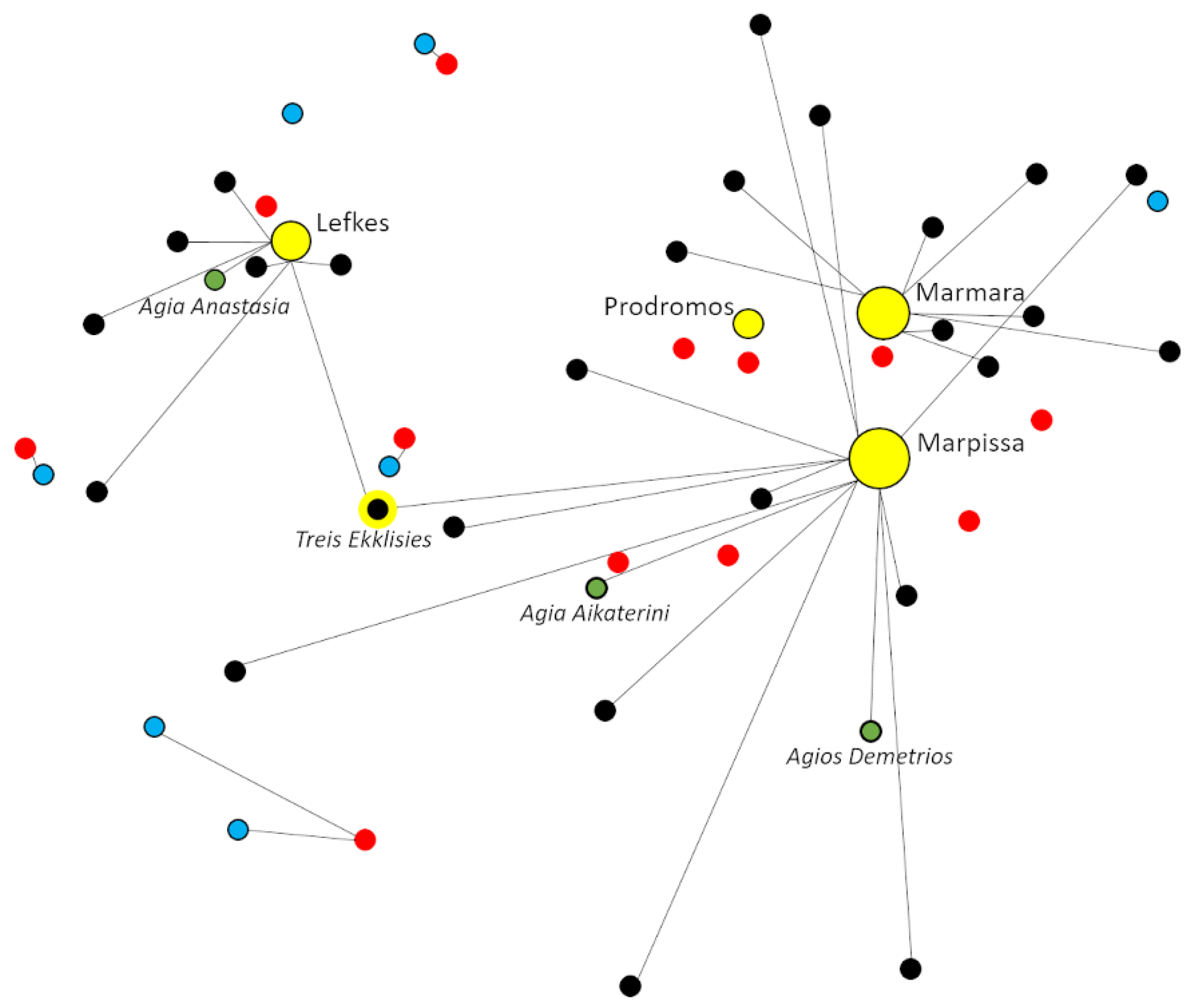

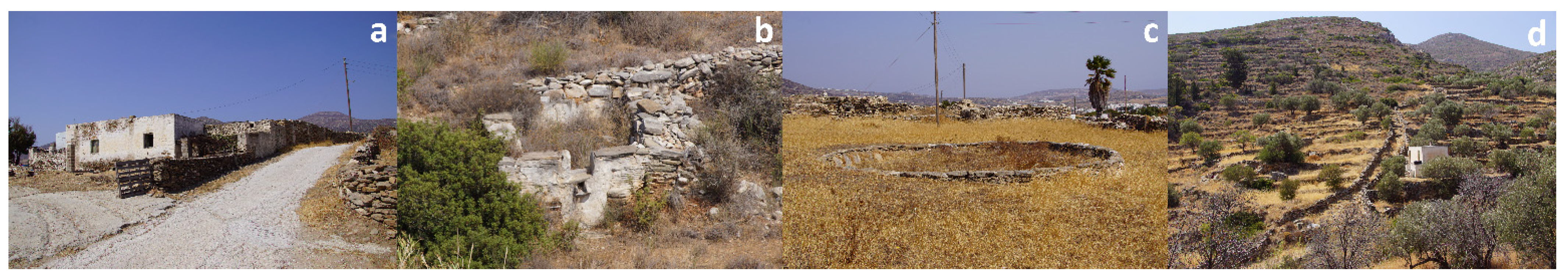

4. An Island Topography of Post-Medieval Churches

5. Discussion: Proskynesis and Kinesis

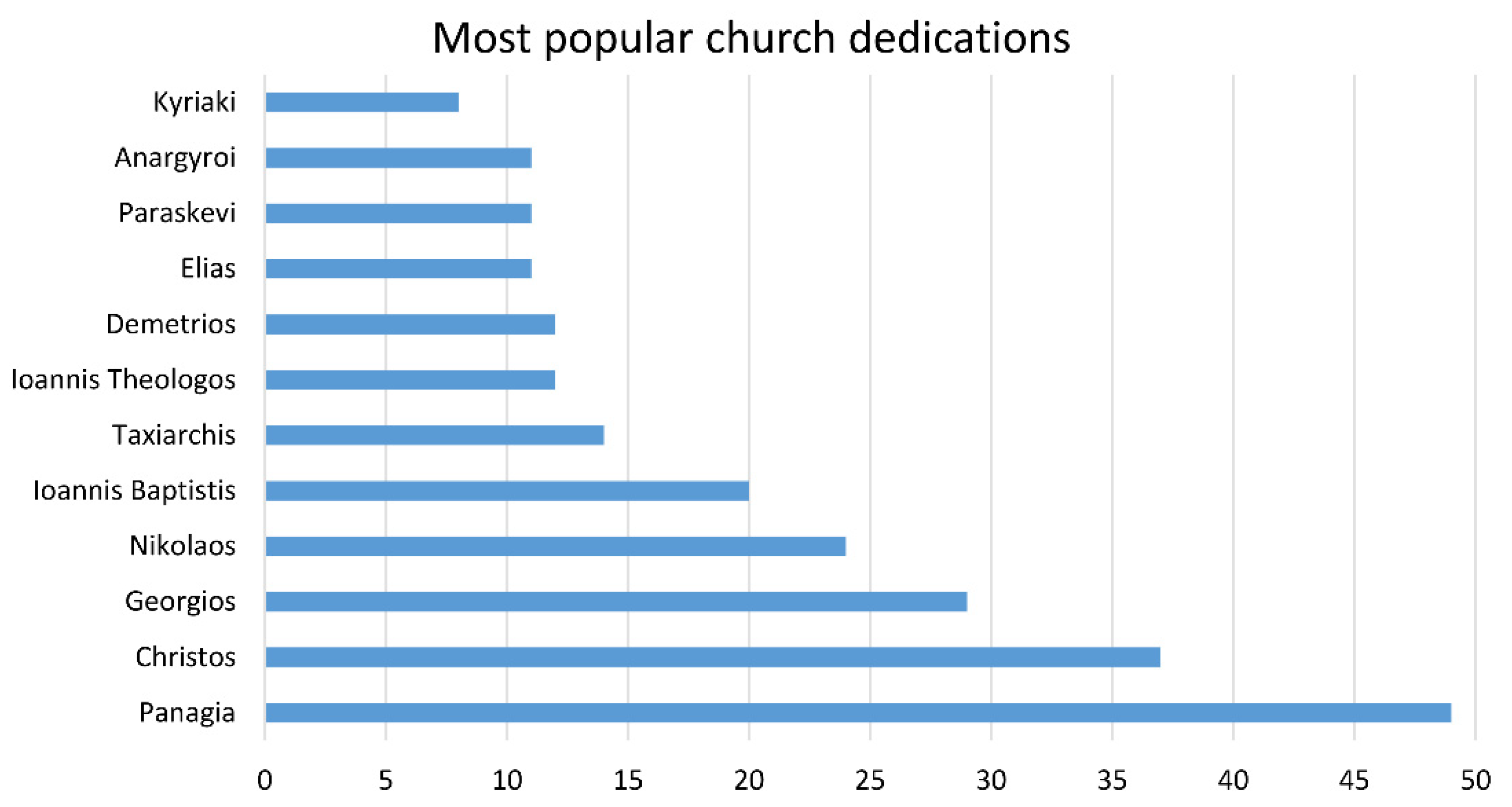

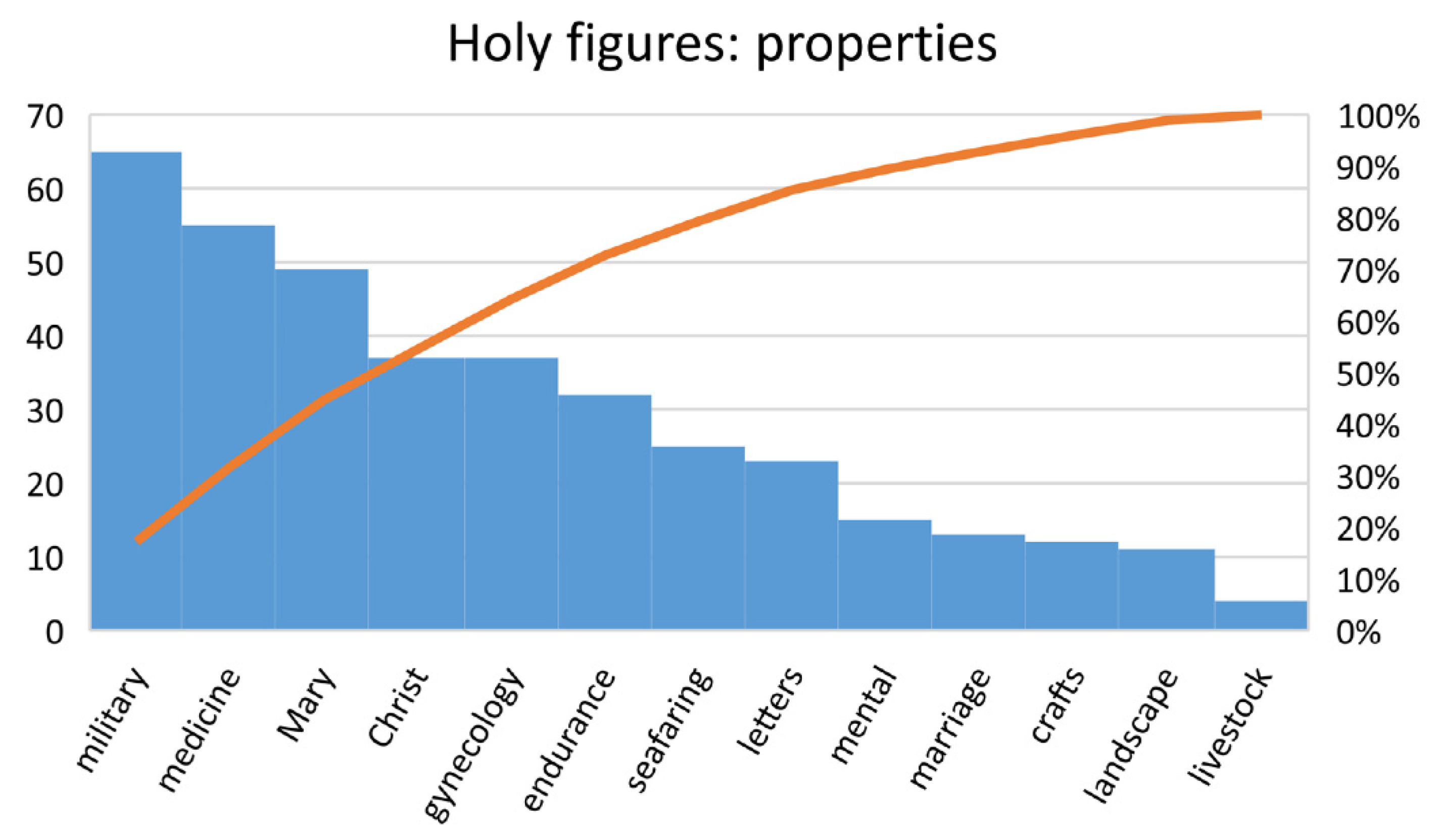

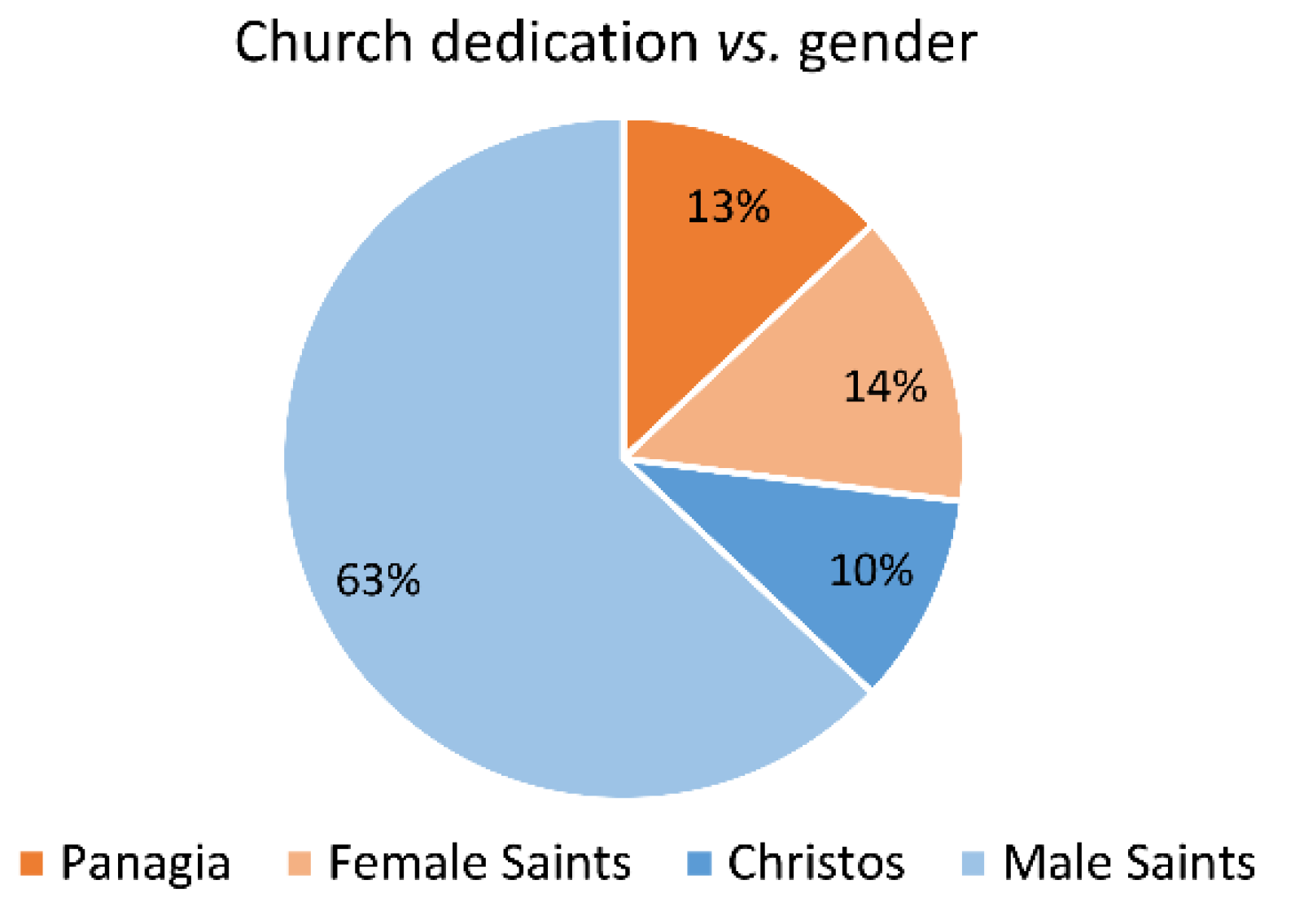

5.1. The Veneration of Saintly Figures

5.2. Kinetic Rituals and Paths of Local Pilgrimage

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abulafia, David. 2019. Islands in Context, A.D. 400–1000. In Change and Resilience: The Occupation of Mediterranean Islands in Late Antiquity. Edited by Miguel Ángel Cau Ontiveros and Catalina Mas Florit. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow, pp. 285–96. [Google Scholar]

- Aliprantis, Nikos C. 1970. Μεταβυζαντινά μνημεία της Πάρου. Επετηρίς Εταιρείας Κυκλαδικών Μελετών 8: 412–83. [Google Scholar]

- Aliprantis, Nikos C. 2020. Προσκυνητές στα Ιερά Σεβάσματα της Λατρείας των Παριανών Προγόνων. H Συμφωνία των Ερειπίων, 13ος-18ος αι. Athens: Pariana. [Google Scholar]

- Andriotis, Konstantinos. 2009. Sacred Site Experience: A Phenomenological Study. Annals of Tourism Research 36: 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asdrachas, Spyros I. 1985. The Greek Archipelago: A Far-Flung City. In Maps and Map-Makers of the Aegean. Edited by Vasilis Sphyroeras, Anna Avramea and Spyros Asdrachas. Athens: Olkos, pp. 235–48. [Google Scholar]

- Asdrachas, Spyros I. 2018. Observations on Greek Insularity. In Islands of the Ottoman Empire. Edited by Antonis Hadjikyriacou. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Aspray, Barnabas. 2021. How Can Phenomenology Address Classic Objections to Liturgy? Religions 12: 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baun, Jane. 2016. Apocalyptic Panagia: Some Byways of Marian Revelation in Byzantium. In The Cult of the Mother of God in Byzantium: Texts and Images. Edited by Leslie Brubaker and Mary B. Cunningham. London: Routledge, pp. 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, James Theodore. 1885. The Cyclades or Life among the Insular Greeks. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bintliff, John L. 2007. Considerations for Creating an Ottoman Archaeology in Greece. In Between Venice and Istanbul: Colonial Landscapes in Early Modern Greece. Edited by Siriol Davies and Jack L. Davis. Princeton: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, pp. 221–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bintliff, John L. 2013. Contextualizing the Phenomenology of Landscape. In Human Expeditions: Inspired by Bruce Trigger. Edited by Stephen Chrisomalis and Andre Costopoulos. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Boomert, Arie, and Alistair Bright. 2007. Island Archaeology: In Search of a New Horizon. Island Studies Journal 2: 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, Charalampos. 2001. Βυζαντινή και Μεταβυζαντινή Aρχιτεκτονική στην Ελλάδα. Athens: Melissa. [Google Scholar]

- Braudel, Fernand. 1972. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Translated by Siân Reynolds. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Broodbank, Cyprian. 2000. An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Peter. 1981. The Cult of the Saints. Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Peter. 2000. Enjoying the Saints in Late Antiquity. Early Medieval Europe 9: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham, Nicolas. 1981. Medieval Greece. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, John F. 1981. Pattern and Process in the Earliest Colonization of the Mediterranean Islands. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society USA 47: 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, John F., and Thomas P. Leppard. 2015. A Little History of Mediterranean Island Prehistory. In The Cambridge Prehistory of the Bronze and Iron Age Mediterranean. Edited by A. Bernard Knapp and Peter van Dommelen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantakopoulou, Christy. 2007. The Dance of the Islands: Insularity, Networks, the Athenian Empire, and the Aegean World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cormack, Robin. 1985. Writing in Gold: Byzantine Society and Its Icons. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, Jim, Sam Turner, and Athanasios K. Vionis. 2011. Characterizing the Historic Landscapes of Naxos. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 24: 111–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurčić, Slobodan. 1991. Architecture. Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium 1: 157–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ćurčić, Slobodan. 2010. Architecture in the Balkans: From Diocletian to Süleyman the Magnificent. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Jack L. 1991. Contributions to a Mediterranean Rural Archaeology: Historical Case Studies from the Ottoman Cyclades. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 4: 131–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrokallis, Georgios. 1993. Τυπολογική και μορφολογική θεώρηση της μεταβυζαντινής ναοδομίας των Κυκλάδων. In Εκκλησίες στην Ελλάδα μετά την Άλωση (1453–1830). Athens: National Polytechnic University Publications, vol. 4, pp. 185–12. [Google Scholar]

- DiNapoli, Robert J., and Thomas P. Leppard. 2018. Islands as Model Environments. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 13: 157–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dubisch, Jill. 1995. In a Different Place. Pilgrimage, Gender, and Politics at a Greek Island Shrine. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eade, John. 2020. The Invention of Sacred Places and Rituals: A Comparative Study of Pilgrimage. Religions 11: 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, John D. 1973. Islands as Laboratories of Culture Change. In The Explanation of Culture Change: Models in Prehistory. Edited by Colin Renfrew. London: Duckworth, pp. 517–20. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, Hamish. 2007. Meaning and Identity in a Greek Landscape: An Archaeological Ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, Mark. 2012. Oral Tradition, Landscape and the Social Life of Place-Names. In Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England. Edited by Richard Jones and Sarah Semple. Donington: Shaun Tyas, pp. 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparis, Charalambos. 2016. O λοιμός και το τάμα: Oι εκκλησίες του Aγίου Aθανασίου στον μεσαιωνικό Χάνδακα. In Μαργαρίται. Μελέτες στη Μνήμη του Μανόλη Μπορμπουδάκη. Edited by Manolis S. Patedakis and Kostas D. Giapitsoglou. Siteia: Panagia Akroteriane Foundation, pp. 411–27. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadi, Anastasia. 2014. Θολωτές κατασκευές στους μεταβυζαντινούς ναούς της Πάρου. In Ιστορία Δομικών Κατασκευών, 2ο Διεπιστημονικό Συνέδριο. 5–7 Δεκεμβρίου 2014, Ξάνθη. Conference Proceedings. Xanthi: Department of Architectural Engineering and City Council of Xanthi. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel, Sharon E. J. 1998. Painted Sources for Female Piety in Byzantium. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 52: 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstel, Sharon E. J. 2005. The Byzantine Village Church: Observations on its Location and on Agricultural Aspects of its Program. In Les Villages dans l’Empire Byzantin, IVe–XVe Siècle. Edited by Jacques Lefort, Cécile Morrisson and Jean-Pierre Sodini. Paris: Lethielleux, pp. 165–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Erin. 2007. The Archaeology of Movement in a Mediterranean Landscape. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 20: 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, Roberta. 2012. Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist, Roberta. 2020. Sacred Heritage: Monastic Archaeology, Identities, Beliefs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Given, Michael. 2000. Agriculture, Settlement and Landscape in Ottoman Cyprus. Levant 32: 215–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Given, Michael, Oscar Aldred, Kevin Grant, Peter McNiven, and Tessa Poller. 2019. Interdisciplinary Approaches to a Connected Landscape: Upland Survey in the Northern Ochils. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 148: 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Jody Michael. 2018. Insularity and Identity in Roman Cyprus: Connectivity, Complexity, and Cultural Change. In Insularity and Identity in the Roman Mediterranean. Edited by Anna Kouremenos. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow, pp. 4–40. [Google Scholar]

- Grehan, James. 2014. Twilight of the Saints. Everyday Religion in Ottoman Syria and Palestine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjikyriacou, Antonis. 2014. Local Intermediaries and Insular Space in Late-18th Century Ottoman Cyprus. Osmanlı Araştırmaları/The Journal of Ottoman Studies 44: 427–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hadjikyriacou, Antonis. 2018. Envisioning Insularity in the Ottoman World. In Islands of the Ottoman Empire. Edited by Antonis Hadjikyriacou. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, pp. vii–xix. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Mark A. 2010. Wo/men Only? Marian Devotion in Medieval Perth. In The Cult of Saints and the Virgin Mary in Medieval Scotland. Edited by Steve Boardman and Eila Williamson. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, pp. 105–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hartnup, Karen. 2004. On the Beliefs of the Greeks. Leo Allatios and Popular Orthodoxy. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Holst-Warhaft, Gail. 2008. Death and the Maiden: Sex, Death, and Women’s Laments. In Women, Pain and Death: Rituals and Everyday Life on the Margins of Europe and Beyond. Edited by Evy Johanne Håland. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Imber, Colin. 2002. The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650: The Structure of Power. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- İnalcık, Halil. 1972. The Ottoman Decline and its Effects upon the Reaya. In Aspects of the Balkans, Continuity and Change, Contributions to the International Balkan Conference held at UCLA, Oct. 23–8, 1969. Edited by Henrik Birnbaum and Speros Vryonis. Paris: Mouton, pp. 338–54. [Google Scholar]

- İnalcık, Halil. 1973. The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300–1600. New York: Praeger Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- İnalcık, Halil. 1991. The Emergence of Big Farms, Çiftliks: State, Landlords and Tenants. In Landholding and Commercial Agriculture in the Middle East. Edited by Çağlar Kayder and Faruk Tabak. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kalas, Veronica. 2009. Sacred Boundaries and Protective Borders: Outlying Chapels of Middle Byzantine Settlements in Cappadocia. In Sacred Landscapes in Anatolia and Neighboring Regions. British Archaeological Reports International Series 2034; Edited by Charles Gates, Jacques Morin and Thomas Zimmermann. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kasdagli, Aglaia E. 1991. Gender Differentiation and Social Practice in Post-Byzantine Naxos. In The Byzantine Tradition After the Fall of Constantinople. Edited by John J. Yiannias. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, pp. 61–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kenna, Margaret E. 1976. Houses, Fields, and Graves: Property and Ritual Obligation on a Greek Island. Ethnology 15: 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, Machiel. 1990. Byzantine Architecture and Painting in Central Greece, 1460–1570: Its Demographic and Economic Basis According to the Ottoman Census and Taxation Registers for Central Greece Preserved in Istanbul and Ankara. Byzantinische Forschungen 16: 429–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kiel, Machiel. 1997. The Rise and Decline of Turkish Boeotia, 15th–19th Century. In Recent Developments in the History and Archaeology of Central Greece. British Archaeological Reports International Series 666; Edited by John L. Bintliff. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 315–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kiel, Machiel. 2007. The Smaller Aegean Islands in the 16th–18th Centuries According to Ottoman Administrative Documents. In Between Venice and Istanbul: Colonial Landscapes in Early Modern Greece. Edited by Siriol Davies and Jack L. Davis. Princeton: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, Bernard A. 2008. Prehistoric and Protohistoric Cyprus: Identity, Insularity, and Connectivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kolovos, Elias. 2006. H Nησιωτική Kοινωνία της Άνδρου στο Oθωμανικό Πλαίσιο. Πρώτη προσέγγιση με Bάση τα Oθωμανικά ‘Eγγραφα της Καϊρείου Βιβλιοθήκης (1579–1821). Andros: Kaireios Vivliothiki. [Google Scholar]

- Kolovos, Elias. 2007. Insularity and Island Society in the Ottoman Context: The Case of the Aegean Island of Andros (Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries). Turcica 39: 49–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolovos, Elias. 2018. Introduction: Across the Aegean. In Across the Aegean: Islands, Monasteries and Rural Societies in the Ottoman Greek Lands. Edited by Elias Kolovos. Istanbul: The Isis Press, pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantellou, Theodora. 2020. Saint John the Baptist Rigodioktes. A Holy Healer of Fevers in the Church of the Panaghia at Archatos, Naxos (1285). Deltion of the Christian Archaeological Society 41: 173–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kontogiorgis, Giorgos D. 1982. Κοινωνική Δυναμική και Πολιτική Aυτοδιοίκηση: Oι Eλληνικές Κοινότητες της Τουρκοκρατίας. Athens: Ekdoseis Livani. [Google Scholar]

- Krantonelli, Alexandra. 1991. Ιστορία της Πειρατείας στους Mέσους Xρόνους της Τουρκοκρατίας, 1538–1699. Athens: Estia. [Google Scholar]

- Krausmüller, Dirk. 2016. Making the Most of Mary: The Cult of the Virgin in the Chalkoprateia from Late Antiquity to the Tenth Century. In The Cult of the Mother of God in Byzantium: Texts and Images. Edited by Leslie Brubaker and Mary B. Cunningham. London: Routledge, pp. 219–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lape, Peter V. 2004. The Isolation Metaphor in Island Archaeology. In Voyages of Discovery: The Archaeology of Islands. Edited by Scott M. Fitzpatrick. Westport: Praeger, pp. 223–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Legrand, Emile. 1889. Notice biographique sur Jean et Théodose Zygomalas. In Recueil de Textes et de Traductions Publié par les Professeurs de l’Ecole des Langues Orientales Vivantes (VIIIe Congrès International des Orientalistes, Stockholm 1889). Paris: E. Leroux, pp. 69–264. [Google Scholar]

- Magennis, Hugh. 2001. Warrior Saints, Warfare, and the Hagiography of Aelfric of Eynsham. Traditio 56: 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamut, Elisabeth. 1988. Les îles de l’Empire Byzantin: VIIIe-XIIe Siècles. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. [Google Scholar]

- Manolopoulou, Vicky. 2019. Processing Time and Space in Byzantine Constantinople. In Unlocking Sacred Landscapes: Spatial Analysis of Ritual and Cult in the Mediterranean. Edited by Giorgos Papantoniou, Christine E. Morris and Athanasios K. Vionis. Nicosia: Astrom Editions, pp. 155–67. [Google Scholar]

- Margry, Peter J. 2008. Secular Pilgrimage: A Contradiction in Terms? In Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World: New Itineraries into the Sacred. Edited by Peter J. Margry. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- Meri, Yousef. 2015. The Cult of Saints and Pilgrimage. In The Oxford Handbook of the Abrahamic Religions. Edited by Adam J. Silverstein and Guy G. Stroumsa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, William. 1908. The Latins in the Levant: A History of Latin Greece (1204–1566). London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Robert S. 2011–2012. ‘And So, with the Help of God’: The Byzantine Art of War in the Tenth Century. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 65/66: 169–92. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, Lucia. 2006. Making a Landscape Sacred: Outlying Churches and Icon Stands in Sphakia, Southwestern Crete. Oxford: Oxbow. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandos, Anastasios K. 1961. Oι Mεταβυζαντινοί Nαοί της Πάρου. Aρχείον των Βυζαντινών Μνημείων της Ελλάδος 9. Athens: Estia. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandos, Anastasios K. 1964. Oι Mεταβυζαντινοί Nαοί της Πάρου. Aρχείον των Βυζαντινών Μνημείων της Ελλάδος 10. Athens: Estia. [Google Scholar]

- Ousterhout, Robert G. 2019. Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Papaconstantinou, Arietta. 2007. The Cult of Saints: A Haven of Continuity in a Changing World? In Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700. Edited by Roger S. Bagnall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 350–67. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, Chryssanthi. 2010. Aphrodite and the Fleet in Classical Athens. In Brill’s Companion to Aphrodite. Edited by Amy C. Smith and Sadie Pickup. Leiden: Brill, pp. 217–33. [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannaki, Anthousa. 2010. Aphrodite in Late Antique and Medieval Byzantium. In Brill’s Companion to Aphrodite. Edited by Amy C. Smith and Sadie Pickup. Leiden: Brill, pp. 321–46. [Google Scholar]

- Papantoniou, Giorgos. 2012. Religion and Social Transformations in Cyprus: From the Cypriot ‘Basileis’ to the Hellenistic ‘Strategos’. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Papantoniou, Giorgos. 2013. Cypriot Autonomous Polities at the Crossroads of Empire: The Imprint of a Transformed Islandscape in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 370: 169–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papantoniou, Giorgos, and Christine E. Morris. 2019. Kyprogenes Aphrodite: Between Political Power and Cultural Identity. In Gods of Peace and War in the Myths of the Mediterranean People. Edited by Konstantinos I. Soueref and Ariadni Gartziou-Tatti. Ioannina: Ministry of Culture and Sports—University of Ioannina, pp. 147–73. [Google Scholar]

- Papantoniou, Giorgos, and Athanasios K. Vionis. 2020. Popular Religion and Material Responses to Pandemic: The Christian Cult of the Epitaphios during the COVID-19 Crisis in Greece and Cyprus. Ethnoarchaeology 12: 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patelis, Panagiotis I. 2004. Παρεκκλήσια και Eξωκλήσια της Πάρου. Paros: Holy Pilgrimage of Panagia Hekatontapyliane. [Google Scholar]

- Pouqueville, François Charles Hugues Laurent. 1821. Voyage dans la Grèce. Paris: Chez Firmin Didot, père et fils. vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Rackham, Oliver. 2012. Island Landscapes: Some Preliminary Questions. Journal of Marine and Island Cultures 1: 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rainbird, Paul. 2007. The Archaeology of Islands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, Colin, and Malcolm Wagstaff. 1982. An Island Polity: The Archaeology of Exploitation in Melos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roussos, Konstantinos. 2017. Reconstructing the Settled Landscape of the Cyclades: The Islands of Paros and Naxos during the Late Antique and Early Byzantine Centuries. Leiden: Leiden University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seifreid, Rebecca, and Tuna Kalaycı. 2019. An Exploratory Spatial Analysis of the Churches in the Southern Mani Peninsula, Greece. In Unlocking Sacred Landscapes: Digital Humanities and Ritual Space. Edited by Giorgos Papantoniou, Apostolos Sarris, Christine E. Morris and Athanasios K. Vionis. Open Archaeology 5. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 519–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, Ben J. 1982. Archipelagus turbatus: Les Cyclades entre Colonisation Latine et Occupation Ottomane, c. 1500–1718. 2 vols, Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. [Google Scholar]

- Slot, Ben J. 2001. H Σίφνος: μία ειδική νησιωτική οικονομία (15ος-17ος αιώνας). In Πρακτικά A΄ Διεθνούς Σιφναϊκού Συμποσίου. Σίφνος 25-28 Ιουνίου 1998. Βυζάντιο, Φραγκοκρατία, Νεότεροι Χρόνοι. Athens: Etaireia Sifnaikon Meleton, vol. 2, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Smyrlis, Kostis. 2020. Monasteries, Society, Economy, and the State in the Byzantine Empire. In The Oxford Handbook of Christian Monasticism. Edited by Bernice M. Kaczynski. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollars, Luke. 2005. Settlement and Community: Their Location, Limits and Movement through the Landscape of Historical Cyprus. Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Spiridonakis, Vasilis G. 1977. Essays on the Historical Geography of the Greek World in the Balkans during the Turkokratia. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Julian. 2001. Archaeologies of Place and Landscape. In Archaeological Theory Today. Edited by Ian Hodder. Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 165–86. [Google Scholar]

- Thouki, Alexis. 2019. The Role of Ontology in Religious Tourism Education–Exploring the Application of the Postmodern Cultural Paradigm in European Religious Sites. Religions 10: 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tilley, Christopher. 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Tournefort, Joseph Pitton de. 1718. A Voyage into the Levant Performed by Command of the Late French King. London: D. Browne, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiadis, Dimitrios V. 1962. Aι επιπεδόστεγοι μεταβυζαντιναί βασιλικαί των Κυκλάδων. Επετηρίς Εταιρείας Κυκλαδικών Μελετών 2: 318–645. [Google Scholar]

- Vatin, Nicolas, and Gilles Veinstein. 2004. Insularités Ottomanes. Paris: Institut Français d‘ études Anatoliennes. [Google Scholar]

- Vidali, Maria. 2009. Γη και Χωριό. Τα Εξωκλήσια της Τήνου. Athens: Futura. [Google Scholar]

- Vionis, Athanasios K. 2012. A Crusader, Ottoman, and Early Modern Aegean Archaeology: Built Environment and Domestic Material Culture in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Cyclades, Greece (13th–20th Century AD). Leiden: Leiden University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vionis, Athanasios K. 2014. The Archaeology of Landscape and Material Culture in Late Byzantine-Frankish Greece. In Recent Developments in the Long-Term Archaeology of Greece. Edited by John L. Bintliff. Pharos 20.1. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 313–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vionis, Athanasios K. 2016. A Boom-Bust Cycle in Ottoman Greece and the Ceramic Legacy of Two Boeotian Villages. Journal of Greek Archaeology 1: 353–84. [Google Scholar]

- Vionis, Athanasios K. 2017. Imperial Impacts, Regional Diversities and Local Responses: Island Identities as Reflected on Byzantine Naxos. In Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule. Edited by Rhoads Murphey. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 165–96. [Google Scholar]

- Vionis, Athanasios K. 2019a. The Spatiality of the Byzantine/Medieval Rural Church: Landscape Parallels from the Aegean and Cyprus. In Unlocking Sacred Landscapes: Spatial Analysis of Ritual and Cult in the Mediterranean. Edited by Giorgos Papantoniou, Christine E. Morris and Athanasios K. Vionis. Nicosia: Astrom Editions, pp. 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vionis, Athanasios K. 2019b. The Materiality of Death, the Supernatural and the Role of Women in Late Antique and Byzantine Times. Journal of Greek Archaeology 4: 252–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vionis, Athanasios K., and Giorgos Papantoniou. 2019. Economic Landscapes and Transformed Mindscapes in Cyprus from Roman Times to the Early Middle Ages. In Change and Resilience: The Occupation of Mediterranean Islands in Late Antiquity. Edited by Miguel Ángel Cau Ontiveros and Catalina Mas Florit. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow, pp. 257–84. [Google Scholar]

- Vogiatzakis, Ioannis N., Maria Zomeni, and Antoinette M. Mannion. 2017. Characterising Landscapes: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges Exemplified in the Mediterranean. Land 6: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, Joshua M. 2018. Piracy and Law in the Ottoman Mediterranean. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, Robert J. 1998. Island Biogeography: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Christina G. 2021. Urban Rituals in Sacred Landscapes in Hellenistic Asia Minor. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Zerlentis, Pericles G. 1913. Ιστορικαί ‘Eρευναι περί τας Εκκλησίας των Nήσων της Aνατολικής Μεσογείου Θαλάσσης. Hermoupolis: Nicolaos G. Freris, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vionis, A.K. The Construction of Sacred Landscapes and Maritime Identities in the Post-Medieval Cyclades Islands: The Case of Paros. Religions 2022, 13, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020164

Vionis AK. The Construction of Sacred Landscapes and Maritime Identities in the Post-Medieval Cyclades Islands: The Case of Paros. Religions. 2022; 13(2):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020164

Chicago/Turabian StyleVionis, Athanasios K. 2022. "The Construction of Sacred Landscapes and Maritime Identities in the Post-Medieval Cyclades Islands: The Case of Paros" Religions 13, no. 2: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020164

APA StyleVionis, A. K. (2022). The Construction of Sacred Landscapes and Maritime Identities in the Post-Medieval Cyclades Islands: The Case of Paros. Religions, 13(2), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020164