Abstract

The issue of the use of marketing tools by religious organisations is a research problem because for moral reasons, churches declare that they do not use marketing communication explicitly. In religious circles, marketing tends to be associated with unethical practices, especially public relations, which in practice can be associated with propaganda. A careful analysis of the activities carried out by churches shows that many marketing communication methods and tools are used by religious organisations. To be successful, companies must identify the basic elements determining customer satisfaction and meet them more effectively than their competitors. At the same time, it is not about one-off transactions, but about building long-term relationships. This model is also slowly finding acceptance in religious circles, despite arguments that satisfying individual needs will be at the expense of church doctrine or will result in long-standing church traditions being abandoned and replaced by pop-cultural attitudes. The article discusses the specificity of building the brand image of the Catholic Church in Poland and the use of modern marketing tools in this process. It also presents the results of the authors’ research, which leads to the final conclusions verifying the research hypotheses set out in the research methodology. The article aims to initiate a wider discussion on the controversial topic of implementing commercial marketing tools into the image management processes of the Catholic Church. The conducted research results indicate the need for a change in the perception of the Catholic Church in Poland of the communication processes leading to the building and strengthening of its image. A major challenge for the Catholic Church in Poland seems to be changing the attitudes of non-believers towards the Catholic Church.

1. Introduction

No well organised company that wants to remain in a demanding and competitive market can afford not to have marketing and public relations specialists within its structures. Today, they help not only companies but also a wide range of institutions and social organisations, such as trade unions, government agencies, charities, foundations, hospitals, educational and religious institutions. All institutions, in order to achieve their goal, need to develop positive relationships with a wide range of actors, such as employees, members, customers, local communities, stakeholders and, in general, the general public (Heath 2013). Thus, in view of the numerous issues currently faced by religious organisations, including churches and religious associations, the question arises whether specialised public relations groups should not be an essential element, well embedded in their structures. A positive answer to this question was given many years ago by many churches of the Protestant tradition. It is difficult not to find public relations teams in their organisational structures today. Wherever a vacancy exists, offers of employment are made in order to hire a specialist in this field.

The need for specialised public relations teams in religious structures is due to a number of reasons. Churches enjoy less and less recognition and trust in secularising societies. There is also a growing body of research about management and marketing treating churches as type of NGO (Ojo and Nwankwo 2020; Haustein 2011; Pfang 2015). As far as the Catholic Church in Poland is concerned, according to numerous surveys conducted in 2020, a decline in trust in it is noticeable. In January of that year, only 39.5% of Poles declared trust in the Catholic Church. The same level of trust concerned the judiciary system (public level of trust in selected authorities and institutions in Poland in 2020). According to a report released in 2021 by the Catholic News Agency, the level of religious practices of young people in Poland has halved over the past thirty years (Gawroński et al. 2021). A report compiled by the Institute for Catholic Church Statistics found that the number of practitioners at Sunday Mass decreased slightly in 2018, only to hold steady thereafter (Boguszewski et al. 2020). In addition, all church denominations, including those that enjoy a high level of recognition despite a decrease in the number of believers, must always take care of their followers, since membership in a church is not something given permanently. Members of religious associations change their place of residence, become less and less interested in religion or simply wish for a change. Ageing communities lose believers due to deaths. Some members of churches may be inactive, some consider themselves alienated, and others may not feel the need to belong to a particular community. In other words, some will be ready to join a community and others will abandon it. For these reasons, churches must constantly be concerned about retaining current members or be concerned about attracting new ones.

It was already proven many years ago that using the tools necessary to build an organisation’s brand or using the means the most commonly used in public relations serve religious organisations in a positive way. Indeed, many years ago, research showed that a church that enjoys a good name in the community (which means to the end that it has a good brand) is very likely to enjoy the commitment of its members, who will rarely leave it. A positive image is also a key element of an effective strategy for the future and an affirmation of the purposefulness of conducted activities (Stevens et al. 1992).

The need for public relations teams emerged as the discussion about the possibility of using marketing tools in practice began. When thinking about church marketing, it is important to consider not only the issue of brand identity, product offerings, diversity of target audiences and the theological dimension of conflict (Horne and McAuley 1999). It will be akin to service marketing, which seeks to promote intangible product offerings such as healthcare or travel, as opposed to tangible product offerings such as motor vehicles or clothing (van der Merwe et al. 2013). Thus, already in 1960, when talking about the functioning of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in American society, it was pointed out that the task of public relations was to present the positive side of church activities (Michael 1960). A dozen years later, in the 1980s, a survey was conducted among Protestant and Catholic clergy in North Carolina on major marketing categories and techniques such as sales, public relations and advertising. All of these categories were positively received by the clergy surveyed (Dunlap et al. 1983; Rezaei 2020). Research conducted in Ghana with clergy belonging to one of the Pentecostal Churches shows that there is a positive relationship between public relations conducted on radio and an increase in the number of believers (Appiah et al. 2013). Let us clarify that both the Seventh-Day Adventist Church and the Pentecostal Churches derive from the Reformation, whose main foundations of ecclesiology and spirituality were formed as a result of the renewal carried out in Protestantism between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries (Schwartz and Greensleaf 2000; Mehl 2002; Yrigoyen and Warrick 2013).

The appreciation of the importance of public relations is directly linked to the attention given to marketing in the life of churches. It gains recognition in ecclesiastical spheres as long as it is well understood. More specifically, as long as it is properly planned, designed and used, it does not contradict the core values of religion and may bring important benefits to the activities of a religious organisation. The use of marketing techniques in some American Protestant churches has led to an increase in the involvement of believers in the life of the community. Moreover, it has been possible through these techniques to identify and address the needs of communities, not only in the United States. Research conducted in Hong Kong on community communication, provided information on the church’s ministry and the growth of donors to the church itself. Research conducted in Catholic Indonesian dioceses highlighted the need to strengthen communication with the faithful and to be sensitive to the needs of the people who gather for the Eucharistic service (Junianto 2018).

Marketing activities are not only used by Christian churches. For example, in New York City, a rabbi from the Makor Jewish Religious Center commissioned a marketing study to identify needs in order to persuade its members to attend services. In response to the results, the rabbi decided to drastically reform his religious ministry (McGrath 2009). Let us point out that churches have always used public relations in some sense. They have also created marketing plans. Most churches can run long-term promotions to fill sanctuaries and increase budgets, but such events are short-lived and lack lasting inspiration (Conrad 2008).

Paying attention to the possibilities of using marketing tools in the life of religious communities also affects the functioning of the business itself. Namely, along with drawing the attention of churches to the issues related to marketing and the possibilities of their use in church activities, the need for honest use of the tools used by employees of companies and enterprises engaged in activities undertaken to create and maintain a good reputation of the company was emphasized. It was recalled that mutual understanding between a company and the recipients of its activities requires the provision of true and complete information, thus the professional and ethical use of public relations. Of course, public relations is not the same as marketing. The issue of public relations primarily concerns communication tools, while marketing also includes needs assessment, product development, pricing and distribution. Public relations tries to influence attitudes, while marketing tries to influence specific consumer behaviour. Public relations does not define the organisation’s objectives, whereas marketing is closely involved in defining the organisation’s target audience and its products (Fawkes 2020).

2. Marketing in Churches, Doubts and Proper Understanding

Churches have always applied certain techniques and used tools that we can today describe as marketing. However, in a strict sense, the use of marketing techniques in religious organisations was first recommended by Harvard professor and later dean of the College of Commerce at the University of Notre Dame James Culliton, who in 1959 accused churches of not using proper marketing practice in their activities. He also found no research conducted on marketing by religious organisations and suggested that using better tools would increase church membership (Culliton 1959). Since then, numerous studies have been conducted on this topic. While noting that each such study must take into account the specifics of the church, its current problems and its financial situation.

The proposal to use marketing techniques in the practice of the churches has met with much appreciation, but also with some criticism. The arguments put forward in the initial phase of the discussion on this subject are still repeated today and can be summarised as follows: money that should be spent on religious activities is wasted, marketing uses manipulation and marketers want to invade people’s personal lives, it is incompatible with the spirit of leadership, it takes away the sacred meaning of religion, it contradicts biblical precepts. Finally, the use of marketing would be useful if churches had unnecessary money (Shawchuck et al. 1992; Wrenn 1994; Newman and Benchener 2008; Gavra 2016). Citing these objections, Norman Shawchuk wrote figuratively that “metaphorically, a lack of understanding as to the true nature of marketing can be linked to the individual who has seen a hammer being used only as a tool of destruction and who, upon being handed a hammer when asking for a tool to use in construction, wonders if the other person has taken leave of his senses. In the same way, if marketing has been perceived as only deceptive advertising by dishonest salespersons and as efforts to manipulate demand (tool of destruction), it will be dismissed by individuals or religious institutions when faced with problems that it might help them solve” (Shawchuck et al. 1992, p. 43).

The difficulty of using marketing in the activities of churches may be due to the fact that it is sometimes misunderstood and evokes associations that are not compatible with the activities of religious associations. We can therefore see that the definition of marketing is important in this respect. As early as 1994 Bruce Wrenn pointed out that if it is conceived as “marketing the church”, such a concept would not be well received. It would be more readily accepted if it were conceived as “being responsive to people’s needs” (including current members as well as a well-defined segment of society)”. The reason is that it is “at the heart of why churches exist” (Wrenn 1994, p. 24).

The positive approach of churches to marketing is related in some way to the work of non-profit organisations. It was them who started to use marketing tools in the 1970s in the United States. When using marketing, they did not pay attention, as business does, to optimising profits, but to stable cooperation with stakeholders and target consumers of products (McGrath 2009, p. 130; Iyer et al. 2014). Considering the most important marketing activities undertaken in the area of non-profit organisations, it must be stated that they are focused on the promotion of the organisation itself. The managers of these organisations have a mentality focused on the organisation itself. A small number of employees are trained in marketing activities (Dolnicar and Lazarevski 2009). Non-profit organisations generally do not compete with each other and evaluation of their activities is difficult because their goals are not defined around financial objectives, but rather focus on the mission they perform. A leader has an important place in the activities of non-profit organisations. Quite different from profit-oriented organisations, the leader in a non-profit organisation is service-oriented, which has a positive impact on the ultimate performance of the organisation he or she leads (McMurray et al. 2012; Hernández-Perlines and Araya-Castillo 2020). In this context, we must also not forget the volunteers working within the ministry of churches and carrying out charitable activities (Wymer 1998; DiGuiseppi et al. 2014). Regardless of the fact that Christian charities are not the same as secular non-profit organisations, the activities they carry out, reaching out to marketing means, have always met with a positive reception among community members. (Kotler and Levy 1969; Sargeant et al. 2002; Lumpkins et al. 2015, vol. 43, pp. 381–88; Abreu 2006). Church institutions are closer to non-profit organisations than to strictly business activities (van der Merwe et al. 2013). While bearing in mind that the rapid proliferation of social media is opening up new opportunities for non-profit organisations and for church charities. Like other organisations, they have realised the need to use social media as a tool to keep in touch with their own members and with the society in which they operate. They use Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Flicker, Bloggers, Word Press, Delicious, etc. without much restriction. (Uchechukwu and Eke 2019).

There are many definitions of marketing that could be used by churches (Sherman and Devlin 2000; Prehn 2004; Stevens et al. 2005; Horne and McAuley 1999). A convincing definition, which is still valued today, has already been given by Norman Shawchuck who believes that church marketing is a tool by which concrete decisions are taken (regarding what religious organisations can or cannot take in order to fulfil their mission” (Shawchuck et al. 1992, p. 41). We can say that the marketing that churches use is therefore not selling, advertising or promotion, although it may contain all of these elements. Marketing is “the analysis, planning, implementing and control of carefully formulated programs, in order to determine voluntary exchange with specific target groups, in order to accomplish the missionary objectives of the organization” (Appiah et al. 2013, p. 11). In other words, marketing can help a religious organization fulfill its mission by interacting with different groups.

The highly regarded definition of marketing used by churches is “the analysis, planning and management of voluntary exchange between a church or religious organisation and its constituents for the purpose of satisfying the needs of both parties. It concentrates on the analysis of constituents’ needs, developing programs to meet these needs, providing these programs at the right time and place, communicating effectively with constituents, and attracting the resources needed to underwrite the activities of the organization” (Stevens et al. 2005).

The cited definitions show that the main constituents (i.e., church members, clergy and members of the public) are the primary target of church marketing activities. In other words, church marketing aims to identify the needs of potential target audiences and guide the design of appropriate products and services to meet those needs (Mulyanegara et al. 2011).

Modern marketing offers the necessary tools to fill in and complete the process, and the results are useful to the organisation that uses them. It is for this reason that in the 1980s Christian churches of the Protestant tradition began to use marketing strategies similar to those used in business. Research shows that 82 per cent of churches operating in the city of Phoenix (AZ, USA) used advertising, articles in the religious sections of newspapers, writing e-mail letters and issuing newsletters. Research shows that at the same time 80% of Protestant as well as Catholic clergy used some advertising tools and 70% used advertising. In 1986, 93% of Protestant pastors in Texas used advertising, which included Yellow Pages, daily newspapers and direct emails (Rodrigue 2002). In the early 1990s, positive attitudes also began to be seen in the Catholic Church, despite the fact that as recently as the mid-1990s, many Catholic dioceses in the United States were not using marketing strategists to consider marketing issues (Webb et al. 1998; McGrath 2009; Appiah et al. 2013).

Marketing-like activities are not only used by Christian churches. However, they gain approval when they use the social activities of churches as their tool (Lumpkins et al. 2015). This is also reflected in the research work conducted on this topic. Let us list some important areas:

- General understanding of marketing and its use in practice for church growth, whether youth, adult or elder (Mulyanegara et al. 2011; DiGuiseppi et al. 2014).

- Church branding in the context of increasing the number of believers belonging to different denominations (Abreu 2006; Dover 2006; Einstein 2011; Gargiulo et al. 2011; Casidy 2013; Odia 2014; Woelke 2014; Adebayo 2015; Valaskivi 2019; Wijaya et al. 2019; Baster et al. 2019; White 2019; Coman 2019; Ignatowski et al. 2020).

- The use of strategies, methods and tools with particular attention to advertising as a means to promote the gospel message and increase the number of believers (Webb et al. 1998; Newman and Benchener 2008; Appah and George 2017; Anyasor 2018).

- Examination of the marketing communication tools used by numerous denominations and their evaluation of their effectiveness by pastors to retain current believers and attract new ones (Webb et al. 1998).

- Promoting traditional family values in the context of marketing (Gavra 2016).

- The issue of public relations in church life (Michael 1960; Weeks 1960; Craig 1977; Nwosu 1996; Day et al. 2001; Coleman 2002; Ukah 2003; Ojomo 2007; Hendrix and Hayes 2007; Conrad 2008; Anghelutǎ et al. 2009; Okae-Anti 2011; Tilson 2011; Sundstrom 2012; Mathew and Ogedebe 2012; Appiah et al. 2013; Nwosu and Uffoh 2016; Okon 2017; Junianto 2018; Wiesenberg 2020).

3. The Importance of Public Relations for the Life of Churches

Despite the existence of works about the possibility of churches using marketing tools, it is important to remember that there is still a serious debate about whether religions should use indiscriminately all the techniques used in promotion. These include advertising, public relations, sales force, sales promotions, direct marketing, word of mouth marketing. Each religious organisation should therefore decide which tools it will use, bearing in mind its moral and ethical principles. Some tools may not be accepted and will be contested by fellow believers associated with churches. The right methods to communicate with particular groups in society can allow for an effective promotional campaign (Anghelutǎ et al. 2009). This is particularly important in the case of public relations, where it is not only about choosing or having the right tools, but also about how to approach a religion (Tilson 2011).

The ambivalent approach to the possibility of using the tools of public relations in the activities of any organisation, as well as by church institutions, is essentially due to the fact that they have tended to be used usually in crisis situations. They were resorted to when specific threats arose or the image of the local church deteriorated. Public relations was used in circumstances where the image of a given community had to be improved. Indeed, through public relations in the broadest sense, the image of the church can be restored, which is associated with the original sanctity, i.e., holiness and purity. However, they should not be used only in situations of drastic image deterioration. It is about the constant use of tools in monitoring and nurturing the good image of the organisation (Conrad 2008; Nwanganga 2017). A second aspect that cannot be ignored in this context is the legacy of history, namely that public relations is sometimes associated with propaganda (Weaver et al. 2006).

There is a reticence towards public relations not only on the part of organisations, but also on the part of researchers who study the issue. In general, we can say that there is still a certain distance between public relations researchers and religious organisations. The reason for this is the constantly growing negative image of religions themselves and of religious organisations. Public relations textbooks generally do not deal with religious organisations in detail (Tilson 2011; Wiesenberg 2020).

Irrespective of the cautious comments made and the need to take into account the peculiarities of the church when examining public relations, we also encounter downright enthusiastic approaches to the potentials inherent in marketing tools used by public relations. As Olusegun Ojomo states, public relations should be regarded as a “magic pill” that can help churches gain a good reputation in society and facilitate the process of evangelism. Conducted in a scientific manner, it can support a church in self-discovery, attracting new supporters and members, creating goals and its vision. In other words, to give pride to members, “to open doors to yet unexplored possibilities in immediate and distant segments of church communities” (Ojomo 2007, p. 16).

It should also be noted that at the time when marketing in the church was beginning to be discussed among researchers, Shawchuck et al. (1992) wrote that sooner or later religious communities would recognise the advantages that could arise from having a manager (drawn from among qualified parishioners) in charge of public relations. He or she should attend all meetings of the congregation that concern the communication of information relevant to its image. It is not for him to formulate the development strategy, but he is to be responsible for the tactics of its presentation to the public. Among the benefits that may arise from such a position, the authors included dealing with and anticipating emerging problems as well as a common professional policy in dealing with the public.

In the 1980s, research was conducted among Protestant and Catholic clergy in North Carolina on the main categories of marketing techniques such as sales, public relations and advertising. All of these categories were positively received by the clergy surveyed (Dunlap et al. 1983). A study conducted in Ghana with clergy belonging to a Pentecostal church shows that there is a positive relationship between public relations conducted on radio and an increase in the number of believers (Appiah et al. 2013).

Taking a historical perspective, public relations has always played an important role in the activities of churches (Okae-Anti 2011). Generally, public relations “is the shape of communication that occurs in every type of organisation, rather in commercial or non-commercial, government or private. The role of public relations is to present the organisation in the best light, meaning that the other party can understand about the organisation in the best way” (Runtuwene et al. 2018, p. 1350). Public relations, then, is nothing more than the use of tools designed to nurture the prestige and image of the church as a whole among groups whose attitudes can influence the outcomes and goals the church seeks to achieve in a planned manner. The success that churches enjoy in their activities depends on how well they manage public relations not only for their own benefit, but also for the benefit of their future members. It is worth noting at this point that in such considerations the church is categorised as a non-profit organisation (Acheampong 2014; Sundstrom 2012).

The list of activities that should concern the public relations manager could include all matters related to enhancing the positive image of a congregation. While presenting issues related to congregational life, that is material matters such as outreach to religious facilities, are important in this regard, for public relations managers their responsibilities should include presenting issues of broad media relations and publishing their own publications, as well as using modern technology to communicate with community members and the outside world (Shawchuck et al. 1992).

It should be noted at this point that the issue of public relations in the life of churches was taken up as early as the 1960s, i.e., at a time when the issue of marketing was not well established in the discussion about the possibilities of using specific marketing techniques in the life of churches. Thus, according to the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, the information function is important in public relations. Ignorance of the facts in the life of the churches is the source of prejudice and even hostility. At the same time, it is not enough to disseminate information alone. The facts should be shown from the perspective of long-term goals and the barriers which prevent information from reaching the public consciousness. Public relations should also fulfil a “creative function”. It is about influencing and shaping public opinion, its attitudes and reactions. The activities undertaken in this respect must be accompanied by absolute fidelity to the truth (Michael 1960, p. 19).

Among the objectives of public relations in the perspective of the activities of churches is the building of a positive image of the church, which entails the consolidation of a good reputation in society. However, building a positive image in the environment in which churches operate does not only take place at the level of media contacts, but also includes the provision of facilities that serve the environment, such as schools or hospitals. Such activities, carried out in a professional manner, can lead to an increase in the number of believers (Mathew and Ogedebe 2012).

At the same time, it should not be forgotten that the use of public relations cannot ignore the fundamental purpose of churches. From the Christian point of view, the main purpose of the churches’ use of public relations is to convey the knowledge about Jesus Christ to people outside the communities. This can be done through both words and deeds. The Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences’ Office of Social Communication made recommendations (after a meeting in Taiwan between 23 and 28 November 1998) that “in the context of current “mediated” society, we recommend that every bishops’ conference and diocese appoint as part of “a pastoral plan” a public pastoral office”. It was stressed that “the officer’s key role is to make a presence of the church felt more in society” (Communication Challenges in Asia III 1998, p. 13). A year earlier, the Asian Bishop’s Institute for Social Communication issued a statement after a meeting in Singapore, which read that public relations is primarily about ‘giving of self in love’. The document reads that public relations as proposed by Christians is fundamentally different from business practices. Namely, public relations should be seen not only from a business point of view, but rather as the giving of witness to Christian values by individual Christians and by specific communities. Bearing witness is paramount and remains at the heart of Christian action.

This specific aim of communicating religious content, which is important for Christians, using marketing tools, was pointed out many years ago by the Seventh-Day Adventist church mentioned above. Namely, public relations must be the work of the whole church and not of some selected office. The Adventists emphasized that all available means should be used, thus also the possibility of speaking in churches of other denominations. This is not about seeking publicity, but about building up a good reputation in the environment in which one lives. All initiatives in this area stem from a basic attitude to every human being, that is, addressing them with love. Activities are to be planned and not limited to single speeches, meetings with significant personalities of social life. Public relations is not a “front” operation, it is not a cloak to put on in order to present oneself well from time to time. It is a part and share of what they really are and how we relate to the people around us (Weeks 1960).

Thus, while a specific staff member or public relations department is necessary to run a specialized office, public relations itself is based on the action of the entire community, every official and member radiating out in all its social associations. Public relations is nothing more than sending “signals” of Christian love and presenting a constructive interest in those signals (Weeks 1960).

We can therefore conclude that, despite serious reservations, the churches themselves for many years did not question the possibility of using marketing tools, they generally paid attention to public relations and its importance in their functioning. From the very beginning representatives of these churches emphasized the strictly religious nature and purpose of the use of marketing tools. These postulates are still relevant today. It is about using public relations to preach the Christian message while respecting all Christian values and ethical principles.

The analysis of the literature on the importance of public relations tools in the activities of the Catholic Church indicates a strong need for research in this field. The dynamics of changes occurring in the process of social communication forces changes in the policy of contact between the Church and society. Commercial experience shows that a good communication policy of individuals has a direct impact on the growth of the organisation’s image.

4. Research Methodology

The issue of building the brand image of the Catholic Church in Poland is poorly recognized in the literature. There is a lack of qualitative and quantitative research in this area. The research conducted so far focuses on the use of individual marketing in the marketing activities of the Church. The research results presented in the article are based on the results of quantitative studies. It should be noted that the controversial topic of the research significantly hindered the research process. Therefore, the article identifies five main research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The image of the Catholic Church in Poland is rated higher in comparison to Protestant and Orthodox churches.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The perception of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland depends on the age of respondents.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Poles expect greater involvement of the Catholic Church in Poland in building its image.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Expectations regarding the extent to which social media are used to build the image of the Catholic Church in Poland depend on the age of respondents.

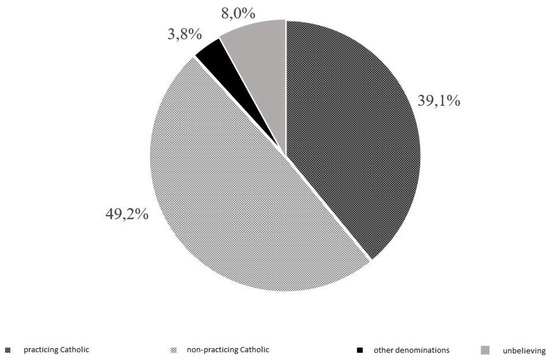

The basis for the development of conclusions in this article was the methodology of qualitative desk research analysis. In order to verify the hypotheses posed in the article, a survey research methodology was carried out. The empirical material was obtained from primary sources, which were people from different age groups and of a different faith. In the quantitative study devoted to the evaluation of the image of the Catholic Church, 425 people took part, 88.3% of whom were Catholics (see Figure 1). The survey was conducted during the COVID 19 pandemic which made access to respondents difficult. In total, 74% of the respondents were women, among the respondents in terms of the place of residence, the largest number of respondents came from the countryside (39%). Taking into account the age structure, the study group consisted of people aged 18–30 (35%). Most of the respondents had secondary/vocational education (58%) (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4).

Figure 1.

Structure of respondents by religion. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

Table 1.

Gender structure.

Table 2.

Abode.

Table 3.

Age structure.

Table 4.

Structure of education.

In terms of basic demographic characteristics, the sample was characterised by the following structure:

- Women constituted almost 75% of the respondents;

- Two thirds of the sample were people aged 19–30, 17.2% aged 31–40, 15.5% people aged 41–64;

- The sample was dominated by people with secondary education (62.5%), people with higher education constituted 35.3%;

- In total, 38.1% of the respondents live in the countryside, 16.9% live in small towns (up to 20 thousand inhabitants), 20.9% live in big cities (over 100 thousand inhabitants).

5. Verification of Hypotheses

The results of the quantitative study were subjected to statistical analysis using descriptive statistics, but also methods of statistical inference, i.e., chi-square independence tests, non-parametric Spearman’s coefficient significance tests, tests of significance of mean values and proportions for independent samples.

Assessment of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland

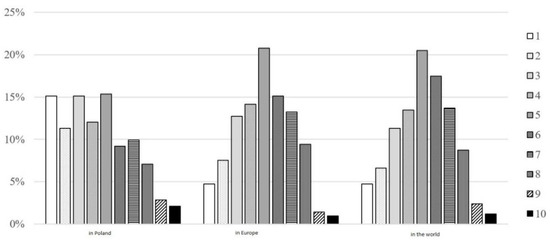

The respondents were asked to rate the image of the Catholic Church in Poland on a scale from 1 to 10 (see Figure 2). The average response was 4.36 with a standard deviation of 2.42, which means that 2/3 of the respondents rated it between 2 and 7. Half of the respondents rated it no higher than 4. It should be noted that the distribution of ratings does not depend on either gender of respondents (p = 0.852 in the chi-square independence test), age (p = 0.369) or education (p = 0.533). However, the analysis showed that image evaluation depended on the size of the locality of residence (p = 0.002 in the chi-square independence test). Moreover, the larger the locality, the lower the mean image score (Spearman rank correlation coefficient equal to −0.258); the highest score was given by inhabitants of rural areas (mean 5.1).

Figure 2.

Assessment of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland, Europe and worldwide. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

Assessment of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland is strongly dependent on the religion of the respondents (p < 0.001 in the chi-square test of independence), with practising Catholics rating the image highest (mean 5.6), non-practising Catholics much lower (mean 3.8) and non-believers the lowest (mean 2.15).

6. Results

This section may be divided into subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

The assessment of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland was accompanied by an assessment of the Catholic Church in Europe and worldwide (see Figure 2). These assessments were strongly correlated with each other (see Table 1). The distributions of the results of the assessments in Europe and worldwide are characterised by a much weaker asymmetry and lesser variation—2/3 of the assessments fall within the range of 3–7, extreme assessments appeared much less frequently than in the case of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland. The non-parametric test for the three dependent samples indicates statistically significant differences between the distributions of the scores of the Catholic Church in Poland, Europe and worldwide (p value < 0.001 in the Friedman two-way variance test). On the other hand, parametric tests for means in the dependent samples (see Table 5) indicate that the mean scores for the image of the Catholic Church in Poland are significantly lower than the mean scores for the image of the Catholic Church in Europe and the world.

Table 5.

Comparison of ratings of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland, Europe and worldwide.

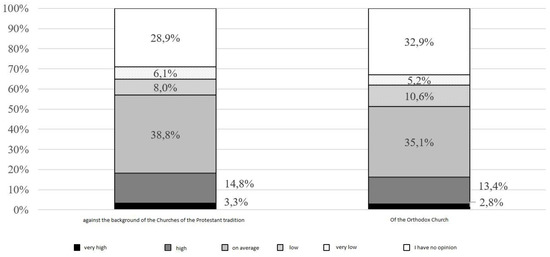

The image of the Catholic Church in Poland was also assessed against the background of the Churches of the Protestant tradition and the Orthodox Church (see Figure 3). More than 1/3 of respondents assessed the image of the Catholic Church in Poland as average, a large part of respondents (almost 1/3) have no opinion on this issue. Only 18.1% gave a high or very high mark as compared to the Protestant tradition churches, even less—16.2%—as compared to the Orthodox Church. The distribution of ratings does not depend on gender, age or education of respondents (p > 0.05 in chi-square independence tests). High or very high ratings of the Catholic Church in Poland compared to the Churches of the Protestant tradition were significantly more frequent among inhabitants of rural areas and small towns (this regularity does not occur in the case of the Catholic Church in Poland compared to the Churches of the Protestant tradition). What is rather obvious, the evaluation of the Catholic Church in Poland against other churches depends on the religion of the respondents, practicing Catholics rated highest (27.1% of respondents from this group rated the Catholic Church in Poland highly or very highly against the churches of the Protestant tradition and 22.3% against the Orthodox Church).

Figure 3.

Assessment of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland as compared to other churches. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

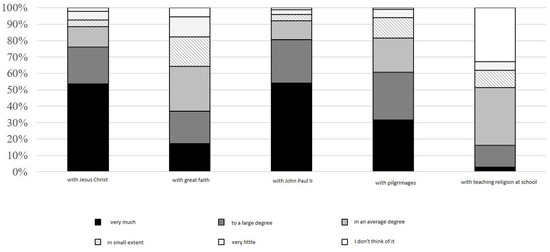

The study has shown that the Catholic Church in Poland is mainly associated with Christian values, i.e., Jesus Christ, deep faith, John Paul II, pilgrimages, religious instruction at school (see Figure 4). Most frequently, respondents associate the Catholic Church in Poland with John Paul II (80.7% associate it to a great or very great extent), Jesus Christ (76%), pilgrimages (60.7%), much less with deep faith (36.9%) or religious instruction at school (16.2%). These associations do not depend on the age or education of the respondents. In the case of some Christian values, differences can be observed in relation to gender and place of residence. Women significantly more often than men associate the Catholic Church in Poland with deep faith (38.7% of women associate it to a great or very great extent), with John Paul II (84%), with Jesus Christ (79.2%). Residents of rural areas and small towns are significantly more likely than residents of medium and large towns to associate the Catholic Church in Poland with John Paul II (86.6% of respondents living in rural areas and 90.3% of respondents living in small towns), and with Jesus Christ (85.8% and 80.5%, respectively).

Figure 4.

Association of the Catholic Church in Poland with main Christian values. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

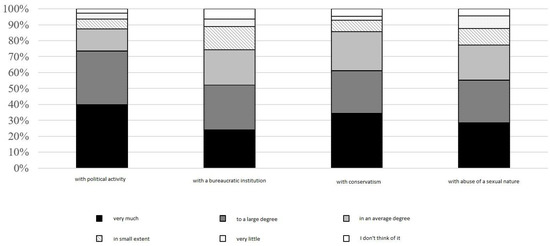

Negative elements of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland, i.e., conservatism, political activity, the bureaucratic nature of this institution, sexual abuse, also appear relatively frequently in associations with the Catholic Church (see Figure 5). Most often, respondents indicated associations with political activity (73.6% associate it to a great or very great extent) and conservatism (61.2%). The intensity of negative associations does not depend on gender, age, or education. In the case of associations with political activity and conservatism, it can be noted that they occur significantly more often among residents of large cities.

Figure 5.

Negative associations with the Catholic Church in Poland. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

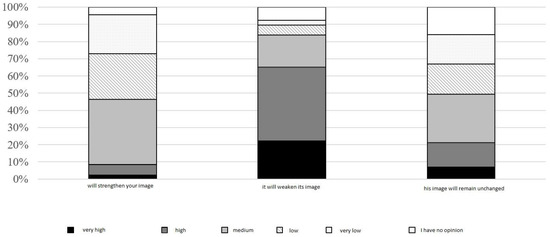

The results of the study clearly indicate that the respondents are not optimistic about improving the image of the Catholic Church in Poland (see Figure 6). Only 8.5% of respondents rated the chances of improving the image as high or very high, with those living in rural areas being the most optimistic (11.1%). On the other hand, as many as 65.2% of respondents assess the chances for image weakening as high or very high. Relatively few people predict the status quo to remain unchanged—only every fifth respondent assesses as high or very high the chances that the image of the Catholic Church in Poland will remain unchanged.

Figure 6.

Expectations regarding the image of the Catholic Church in Poland in the future. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

6.1. Building the Image of the Catholic Church in Poland

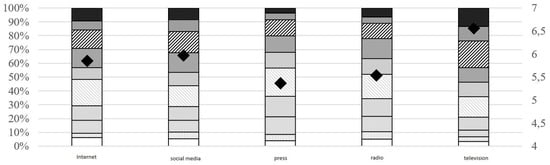

The survey results indicate that the Catholic Church in Poland should carry out activities aimed at image building. The results of the study indicate that the Catholic Church in Poland should carry out activities aimed at image building. 82.6% of the respondents believe so, with 44.8% believing that these activities should be carried out to a high or very high degree. The respondents were asked to assess the role of various means supporting image building. They assigned the highest role to television, half of the respondents rated it at least 7, the highest number of ratings was 8, the average exceeded 6.5 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Assessment of the role of various means supporting image building. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

In the case of most media, i.e., the Internet, social media, press, radio, respondents most often marked a value of 5 on a scale of 1–10, and the average oscillated between 5 and 6. Perhaps surprisingly, the highest average in this group was obtained for social media. Half of the respondents rated the role of the Internet and social media no lower than 6, while in the case of the role of radio and press the median was 5. Moreover, 66.7% of those who expressed their opinion on the use of social media in building the image of the Catholic Church in Poland believe that the Catholic Church should increase the degree of its use in building its image. Statistical analysis showed no statistically significant differences in opinions on the role of various media in assisting image building in the subgroups of the study sample distinguished by gender, age, place of residence, education or religion.

6.2. Features and Brand Identifiers of the Catholic Church in Poland

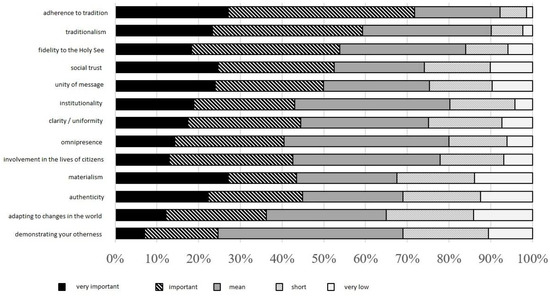

The following characteristics are attributed to the Catholic Church in Poland: attachment to tradition, traditionalism, faithfulness to the Holy See, social trust, unity of message, institutionality (large organisational structure), clarity/uniformity, omnipresence, involvement in the lives of citizens, materialism, authenticity, adapting to changes in the world, demonstrating its distinctiveness (the order results from the survey). It is worth noting the particularly high importance of issues related to tradition indicated by the respondents—71.8% of the respondents regarded attachment to tradition as an important or very important feature of the brand of the Catholic Church in Poland (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Branding characteristics of the Catholic Church in Poland. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

Statistical analysis showed that age may influence opinions on the importance of social trust, authenticity, unity of the message (the young assess the importance of these features higher), and materialism (the young assess the importance of this feature lower). On the other hand, the size of place of residence may influence opinions on the importance of such features as: faithfulness to the Holy See, adapting to changes in the world, authenticity (inhabitants of rural areas and small cities assess the importance of these features higher), institutionalism (inhabitants of medium-sized and large cities assess the importance of this feature higher). Of course, opinions in this regard depend on the religion of the respondents—practising Catholics rated the importance of most of the analysed features of the brand of the Catholic Church in Poland significantly higher.

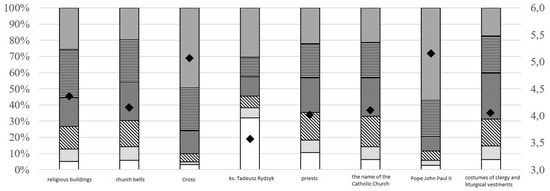

The respondents quantified the brand identifiers of the Catholic Church in Poland. They rated their importance on a scale from 1 to 6—see Figure 9. The respondents rated the person of Pope John Paul II and the Cross as the strongest brand identifiers (mean score of 5.1, about half of the respondents rated the strength of these identifiers maximally). The respondents rated the power of the person of Father Rydzyk as the lowest identifier.

Figure 9.

Branding characteristics of the Catholic Church in Poland. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

Ratings of the power of such identifiers as the Cross, the person of Pope John Paul II and Father Rydzyk depend on the place of residence of the respondents—inhabitants of rural areas and small towns rated the power of the Cross and Pope John Paul II higher than inhabitants of medium and large towns, the opposite in the case of the identifier in the form of Father Rydzyk. Moreover, women rated the power of Pope John Paul II significantly higher. The importance of the three identifiers mentioned above, as well as the name Catholic Church, also depended on the religion of the respondents. Practicing Catholics rated the power of the Cross (mean score of 5.3), the name Catholic Church (mean score of 4.3) and the person of Pope John Paul II (mean score of 5.3) higher, and Father Rydzyk lower (mean score of 3.2, significantly higher than non-believers and non-Catholics).

7. Research Conclusions and Discussion

Although many people may see public relations in the church as a narrow part of its activities, it should in fact be one of the most important aspects of its activities. Combining professional communication with the ministry of the church can help it grow effectively and spread a message that is inherently filled with the message and fulfilment of its mission. Rather than asking why a church needs public relations, it would be better to inquire how it is planned and to whom it is directed. There are many reasons why a church needs planned public relations. Planned public relations in its deepest sense is, in practice, telling and living the truth in a group of people in order to get a full beneficial response. Of course, the issue is related to other marketing activities, such as advertising (Conrad 2008, p. 9).

The analysis of the results of the quantitative study allows us to draw the following conclusions:

- Poles are divided on the issue of the evaluation of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland, one can notice a great diversity of these evaluations.

- The assessment of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland is significantly lower than the average assessment of the image of the Catholic Church in Europe and in the world.

- Respondents are not optimistic about the improvement of the image of the Catholic Church in Poland.

- In the opinion of the respondents, television is the most important medium for building the image of the Catholic Church in Poland.

- Respondents indicated attachment to tradition, traditionalism and faithfulness to the Holy See as the most important features of the brand of the Catholic Church in Poland.

- The person of Pope John Paul II and the cross were considered the strongest identifiers of the Catholic Church in Poland.

Studies show that public relations has a positive impact on the growth of faithful communities belonging to the Pentecostal Church (Ukah 2003; Okon 2017)—it may be confused with our research. This is fully understandable as public relations is a management tool that uses a series of well researched, planned, systematic and sustained activities, among them communication, to build and sustain mutual understanding, respect, acceptance both within the religious group and with the social environment. However, it must be made clear that building and maintaining a solid image and reputation is based on truth, no matter whether the sector is related with manufacturing and service companies, the military, the police or charities and churches (Nwosu 2003). This is fully understandable since, as Michael (1960) has already written, it is about influencing public opinion, attitudes and reactions. In any institution, but especially in churches, such activities must be accompanied by absolute fidelity to the truth (Michael 1960; Nwanganga 2017). Influencing local families, friends and neighbours, building religious community cannot be done at any cost. Public relations in its greatest sense is to be the communication of information based on truth (Conrad 2008). As Craig (1977) writes, the purpose of public relations is not to promote lies, fraudulent actions or intentions. In fact, public relations is about promoting issues that provide truthful answers. It must be accompanied by questions such as whether we are dealing with the truth, actions based on goodwill, serving understanding and the public.

Looking from the perspective of the image-building activities of the Catholic Church, it can be said that public relations has three functions that are identical to those for commercial institutions. Firstly, public relations has an integrative function, which in the case of the Catholic Church is to bond, to integrate the faithful with the Church as an institution and the idea of faith it communicates. The second function is public relations communication, i.e., planned two-way activities that aim to explain the church’s principles. It seems that in the case of the Catholic Church, this function is not completely fulfilled and requires more involvement and understanding of the changes in the communication process of the public. The last function is the coordination of all activities so that they form a coherent and unified message.

It can therefore be concluded that public relations is a multidimensional process with quite a large scope. This reach translates not only into activities of an external nature, but also into internal activities. The key for the Catholic Church seems to be the internal function of public relations, whose aim is to build and strengthen links within the institution itself. In this case, the relational nature of the activities may be important. The ethical dimension of the activities carried out is also important (Hunt 2019). The need to reorient the communication between the Catholic Church and society is forced by the changing trends in the communication of societies, the development of information technologies and the internal problems of the church, which significantly affect its image and perception by society (Rashid and Barron 2019). An important and at the same time essential element of public relations that plays an important role in the functioning of a company or an organisation is cooperation with stakeholders, regulators and lobbying. By stakeholders (Hax 1990), we can understand the collective entities that form relationships with the company or organisation relevant to its functioning. Theoretical considerations classify lobbying as a public relations tool. The literature on the subject also specifies the addressees of lobbying activities, which are: persons responsible for making decisions, e.g., MPs, ministers, national and world press, public opinion (Mastromarco et al. 2005). It is also stated that rule-based lobbying is natural and should not be so controversial. In the case of the Catholic Church, lobbying activities are very influential. To a large extent, church leaders should care about maintaining positive relations with central and local authorities. It should be emphasised, however, that church authorities can and should lobby on issues that are socially important for all citizens, and not only for their followers.

In the direction of tactical actions which the Catholic Church should use in the process of building its brand image, it is necessary to point to a number of media relations tools which can significantly support the process of building the church’s brand image. The main objective of media relations is to form the right relationship with journalists. These relations should make it possible to convey specific information through journalists, which would be directed to an appropriately designated target group. It should be noted that media relations is a specific form of public relations. This specificity results from the possibility to communicate with all target groups. The media themselves are an independent source of information for the recipient. Church leaders, on the other hand, must pay special attention to providing the media with the right information and to the relations between the church and the media (journalists).

The smooth operation of the Catholic Church in the area of contact with journalists is based on a system of current information for the press. This system may be manifested in the following forms: articles, studies, photo services or press releases. Press releases are one of the most effective forms of contact. They should contain brief information on the indicated topic. This information should bear the heading “press release” and should not exceed one page. Therefore, it is important that each curia has a professional press department which, on the one hand, should have a coherent overall information policy and, on the other hand, should keep abreast of events in its own area of activity.

Nowadays, it can be said with certainty that the Internet has had a significant impact on social and economic processes and on the way societies communicate in particular. When looking at the economy, one can also see a clear impact of the Internet’s development on its processes. Therefore, in order to be in constant contact with all parts of society, the Catholic Church should use the latest digital technology tools for communication.

In conclusion, the internet should be a significant tool in the process of communication conducted by the Catholic Church with its recipients (believers) and the society. The Catholic Church should use the internet for public relations activities, in particular to strengthen the brand image of the church. The tool through which it can build its brand image is social media. Of course, they exist because of the internet. These are often tasks that fall under social media marketing, otherwise known as social media public relations. They can provide a huge opportunity for the church in conducting two-way communication. For many audiences, well-run communication has a very high impact on image ratings. An important role is played by social media in crisis situations, and consequently, the Catholic Church should be very keen to disseminate the right information to the largest possible audience. It can be concluded that social media is a platform where Catholics can demonstrate their religious affiliation, share experiences and opinions and engage with the Catholic Church (Baraybar-Fernández et al. 2020).

The discussion of truth in public relations leads to the belief that false or misleading information cannot be disseminated (Day et al. 2001). Being truthful in public relations is also emphasised in the Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) Member Code of Ethics (n.d.). The code does not explicitly mention truthfulness, but we can find it among the values that should accompany all people professionally involved in public relations. Namely, talking about professional ethical values, which should be present in practical actions. These values include responsible advocacy, honesty, expertise, independence (objective and responsible counsel to clients), loyalty to clients while serving the public interest, and fairness in dealing with clients, employers, competitors, the media, and the general public (Public Relations Society of America 2000; Hendrix and Hayes 2007).

8. Conclusions

As the literature shows, the issue of public relations in church life is not new and was already addressed in the 1960s. The discussion on this topic, although with some resistance, continued in the following years mainly in Protestant circles. One of these resistances, although not the most important, was the fact that public relations in practice could be associated with propaganda (Weaver et al. 2006). Among other reasons, we should mention the issue of information flow between churches of different denominations, i.e., mainly Protestant, which effectively use marketing tools in dealing with the environment and are able to take care of their own image, and those denominations, which had to struggle with the problem of acceptance and benevolence towards their activities in the social environment. It is regrettable that this situation has not changed for many years despite the existence and promotion of the ecumenical movement, which emphasises the need for mutual cooperation for the life of the churches (Kasomo et al. 2012). Another reason why the use of public relations, and especially marketing tools, in the life of churches to promote their own image does not gain widespread acceptance is the distance to marketing as such. It must also be acknowledged that the issue of public relations is less and less taken up by scholars who see the continuing marginalisation of religion in highly developed countries in economic terms. However, the research shows that there is a need for the Church to strengthen its public relations activities. A major challenge seems to be changing the attitude of non-believers towards the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church in Poland should in its image-building actions pay more attention to the process of communication with the society. The research results indicate social media as a modern form of information transfer. The authors of the article are aware of certain limitations of the research. Undoubtedly, the research results were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly limited the number of respondents.

The lack of comparative international research should also be pointed out. The authors of the article point to the need for in-depth quantitative research, which will show the complexity of the topic. There is a need for a research programme which will monitor the public relations of various churches, it will also show how the marketing communication of churches develops, and on the other hand it will give a hint to church managers how and in what direction to conduct marketing communication.

Of course, one has to bear in mind the limited scope of the research and therefore the results obtained. Further research should include members of communities that have experienced a much greater crisis of acceptance of religion than in Poland.

This does not change the fact that critical considerations should not be overlooked in further research. Namely, that a marketing perspective that focuses on the individual needs of the client may lead to a diminution of the importance of church doctrine or will result in church traditions rooted in doctrine and practice being abandoned and replaced by pop-cultural attitudes (Coleman 2002; Odia 2014; Nwanganga 2017). Paradoxically, the use of the tools that marketing uses, including to promote one’s own image, finds favour during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sułkowski and Ignatowski 2020; Wildman et al. 2020; Adichie 2021). The use of these tools is particularly important in the context of conducted research, which shows that the assessment of the image of the Catholic Church is not satisfactory and that it should conduct activities aimed at building its own image. Obviously, the conducted research has its limitations, as it was restrained to the territory of Poland. One may hope, however, that public relations and the use of its preferred tools will gain wider recognition in the religious life of many other religious communities.

Author Contributions

G.I., L.S. and R.S.; methodology: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; software: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; validation: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; formal analysis: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; investigation: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; resources: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; data curation: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; writing—review and editing: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; visualization: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; supervision: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; project administration: G.I., L.S. and R.S.; funding acquisition: G.I., L.S. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The research results are available from the Department of Science of the University of Social Siences in Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abreu, Madalena. 2006. The brand positioning and image of a religious organisation: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 11: 139–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, Victoria. 2014. The Effects of Marketing Communication on Church Growth in Ghana. Available online: http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/21722/The%20Effects%20of%20Marketing%20Communication%20on%20Church%20Growth%20in%20Ghana_2014.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Adebayo, Rufus Olufemi. 2015. The Use of Marketing Tactics by the Church in Fulfilling Its Social Mandate in KwaZulu-Natal. Available online: http://openscholar.dut.ac.za/bitstream/10321/1362/1/ADEBAYO_2015.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Adichie, Gloria. 2021. Examining the Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on the Roman Catholic Church in Southeastern Nigeria. Journal of Multidimensional Research & Review 1: 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Anghelutǎ, Alin V., Andreau Strâmbau-Dima, and Zaharia Rǎzvan. 2009. Church Marketing—Concept and Utility. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 8: 171–97. [Google Scholar]

- Anyasor, Okwuchukwu M. 2018. Advertising motivations on church advertising in Nigeria. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development 5: 192–99. [Google Scholar]

- Appah, George Obeng, and Babu P. George. 2017. Understanding Church Growth through Church Marketing: An Analysis on the Roman Catholic Church’s Marketing Efforts in Ghana. Journal of Economics and Business Research 23: 103–22. [Google Scholar]

- Appiah, Sarpong, Gabriel Dwomoh, and Lynda A. Kyire. 2013. The Relationship between Church Marketing and Church Growth: Evidence from Ghana. Global Journal of Management and Business Research 13: 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Baraybar-Fernández, Antonio, Sandro Arrufat-Martín, and Rainer Rubira-García. 2020. Religion and Social Media: Communication Strategies by the Spanish Episcopal Conference. Religions 11: 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baster, Dominic, Shirley Beresford, and Brian Jones. 2019. The “brand” of the Catholic Church in England and Wales: Challenges and opportunities for communications. Journal of Public Affairs 1: e1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguszewski, Rafał, Marta Makowska, Marta Bożewicz, and Monika Podkowińska. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Religiosity in Poland. Religions 11: 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, Riza. 2013. How great thy brand: The impact of church branding on percevied bemefits. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 18: 231–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Barbara C. 2002. Appealing to the Unchurched: What Attracts New Members? Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing 10: 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, Diana. 2019. Branding Elements in the Romanian Orthodox Church. Romanian Journal of Journalism and Communication 14: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Communication Challenges in Asia III. 1998. FABC-OSC Bishops’ Meet 1998 Taoyuan, Taiwan, November 23–28. Available online: http://www.fabc.org/offices/osc/docs/pdf/bm98.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Conrad, Bethany. 2008. Church Marketing: Promoting the Church Using Modern Methods. Available online: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1070&context=honors (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Craig, Floid A. 1977. Christian Communicator’s Handbook: A Practical Guide for Church Public Relations. Nashville: Broadman Press. [Google Scholar]

- Culliton, James W. 1959. A Marketing Analysis of Religion: Can businesslike methods improve the “sales” of religion? Business Horizons 2: 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Kenneth D., Quingwen Dong, and Robins Clark. 2001. Public Relations Ethics: An Overview and Discussion of Issues for the 21st Century. In Handbook of Public Relations. Edited by Robert L. Heath. Thousand Oaks, London and New Delhi: SAGE Publications, pp. 403–10. [Google Scholar]

- DiGuiseppi, Carolyn G., Sallie R. Thoreson, Lauren Clark, Cynthia W. Goss, Mark J. Marosits, Dustin W. Currie, and Dennis C. Lezotte. 2014. Church-based social marketing to motivate older adults to take balance classes for fall prevention: Cluster randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine 67: 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, Sara, and Katie Lazarevski. 2009. Marketing in non-profit organizations: An international perspective. International Marketing Review 26: 275–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dover, Graham. 2006. Branding the Local Church: Reaching Out or Selling Out? London: The London School of Economics and Political Science. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, Bertnard J., Patricia Gaynor, and W. Daniel Roundtree. 1983. The Viability of Marketing in a Religious Setting: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Professional Services Marketing 8: 153–64. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, Mara. 2011. The Evolution of Religious Branding. Social Compass 58: 331–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawkes, Joanna. 2020. What is public relations? In The Public Relations Handbook. Edited by Alison Theaker. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, Danielle, Gowen Kirby, Shar’Niese Miller, and Josanna Schoeff. 2011. A Study of the Branding of Denominations. Undergraduate Research Journal for the Human Sciences 10: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gavra, Ciprian. 2016. Promoting traditional family by the Church—Religious marketing strategies. Ecoforum 5: 171–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gawroński, Sławomir, Dariusz Tworzydło, and Bajorek Kinga. 2021. Determinants for the Development of the Activity of the Catholic Church in Poland in the Field of Social Communication. Religions 12: 845. [Google Scholar]

- Haustein, Jörg. 2011. Christianity, Politics and Public Life in Kenya. Pneuma 33: 134–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hax, Arnoldo C. 1990. Redefining the concept of strategy and the strategy formation process. Planning Review 18: 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Robert L., ed. 2013. Encyclopedia of Public Relations, 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, Jerry A., and Darell C. Hayes. 2007. Public Relations Cases, 7th ed. Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Perlines, Felipe, and Luis Andrés Araya-Castillo. 2020. Servant Leadership, Innovative Capacity and Performance in Third Sector Entities. Fronties in Psychology 11: 623036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horne, Suzanne, and Andrew McAuley. 1999. Church Services. A Conceptual Case for Marketing. Journal of Ministry Marketing and Management 4: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Shelby. 2019. The ethics of branding, customer-brand relationships, brand-equity strategy, and branding as a societal institution. Journal of Business Research 95: 408–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatowski, Grzegorz, Łukasz Sułkowski, and Seliga Robert. 2020. Brand Management of Catholic Church in Poland. Religions 11: 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, Sriya, Chander Velu, and Abdul Mumit. 2014. Communication and Marketing of Services by Religious Organizations in India. Journal of Business Research 67: 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junianto, Pilifus. 2018. Congregations as Consumers: Using Marketing Research to Study Church Attendance Motivations in the Diocese of Bandung Indonesia. Journal of Economics and Business 2: 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kasomo, Daniel, Nicolas Ombachi, Joseph Musyoka, and Niapoo Naila. 2012. Historical Survey of the Concept of Ecumenical Movement its Model and Contemporary Problems. International Journal of Applied Sociology 2: 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, Philip, and Sidney L. Levy. 1969. Broadening the concept of marketing. Journal of Marketing 33: 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkins, Crystal L., Priya Vanchy, Tamara A. Baker, Daley Christine, Ndikum-Moffer Florence, and Greiner Allen. 2015. Marketing a Healthy Mind, Body, and Soul: An Analysis of How African American Men View the Church as a Social Marketer and Health Promoter of Colorectal Cancer Risk and Prevention. Health Education & Behaviour 43: 452–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mastromarco, Dan, Saffer Adam, Zieliński Mirosław, Biedrzycka Urszula, and Hryciuk Konrad. 2005. Sztuka lobbingu w Polsce. Warszawa: USAID/GEMINI Small Business Project. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, James, and Peter M. Ogedebe. 2012. The Role of Public Relations in a Non-Governmental Organization: A Case Study of Ten Selected Christian Churches in Maiduguri. Academic Research International 3: 202–9. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, John. 2009. Congregations as Consumers: Using Marketing Research to Study Church Attendance Motivations. The Marketing Management Journal 19: 130–38. [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, Adela J., Mazharul Islam, James C. Sarros, and Andrew Pirola-Merlo. 2012. The impact of leadership on workgroup climate and performance in a non-profit organization. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 33: 522–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mehl, Roger. 2002. Protestantism. In Dictionary of the Ecumenical Movement. Edited by Nicholas Lossky, Bonino José Miguez, John Pobee, Tom Stransky, Geoffrey Wainwright and Pauline Webb. Geneva: World Council of Churches, pp. 942–49. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Darren L. 1960. Perspective in Public Relations. Ministry. Official Journal of the Ministerial Association of Seventh-Day Adventists 33: 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyanegara, Riza Casidy, Yelena Tsarenko, and Felix Mavondo. 2011. Church Marketing: The Effect of Market Orientation on Perceived Benefits and Church Participation. Services Marketing Quarterly 30: 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Cynthia M., and Paul Benchener. 2008. Marketing In America’s Large Protestant Churches. Journal of Business & Economics Research 6: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nwanganga, Princewell A. 2017. Church Commwercialization in Nigeria: Implications for Public Relations Practice. Journal of Philosophy, Culture and Religion 28: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu, Ikechukwu E. 1996. Public Relations Management: Principles Issues Applications. Aba: Dominican Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu, Ikechukwu E. 2003. Environmental Public Relations Management: Implementation, Models, Strategies, and Techniques. The Nigerian Journal of Communications 2: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu, Ikechukwu E., and Vincent O. Uffoh. 2016. Environmental Public Relations Management: Principles, Strategies, Issues & Cases Paperback. Enugu: Institute for Development Studies, University of Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Odia, Edith. 2014. Operationalizing Marketing in the Church. Nigeria Journal of Business Administration 12: 48–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, Sanya, and Sonny Nwankwo. 2020. God in the marketplace: Pentecostalism and marketing ritualization among Black Africans in the UK. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 14: 349–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojomo, Olusegun. 2007. Public Relations Challenges of the Christian Church in Nigeria. Contemporary Humanities 1: 180–92. [Google Scholar]

- Okae-Anti, Asare. 2011. A History of Public Relations Practice in the Presbyterian Church of Ghana. Available online: http://ir.uew.edu.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/1007/A%20history%20of%20public%20relations%20practice%20in%20the%20Presbyterian%20Church%20of%20Ghana.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Okon, Patrick E. 2017. The Impact of Public Relations on Church Growth in the Redeemed Christian Church of God in Cross River State. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 7: 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pfang, R. 2015. Management in the Catholic Church: Corporate governance. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 12: 38–58. [Google Scholar]

- Prehn, Yvon. 2004. Ministry Marketing Made Easy: A Practical Guide to Marketing Your Church Message. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) Member Code of Ethics. n.d. Available online: https://www.prsa.org/docs/default-source/about/ethics/prsa_code_of_ethics.pdf?sfvrsn=c9b66a6b_2 (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- Public Relations Society of America. 2000. PRSA Code of Ethics. Available online: https://www.prsa.org/about/prsa-code-of-ethics (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Rashid, Faisal, and Ian Barron. 2019. Why the Focus of Clerical Child Sexual Abuse has Largely Remained on the Catholic Church amongst Other Non-Catholic Christian Denominations and Religions. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 28: 564–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, Hamed. 2020. Investigating the Acceptance of Religious Propaganda in Religious Communities with Marketing Tools. Strategic Management Thought 14: 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue, Christina S. 2002. Marketing Church Services: Targeting Young Adults. Services Marketing Quarterly 24: 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtuwene, Kitara, Joyce Lapian, and Merinda Pandowo. 2018. Church Marketing: The Effect of Promotional Strategies on Church Growth in Manado. Journal EMBA 6: 1348–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, Adrian, Susan Foreman, and Mei-Na Liao. 2002. Operationalizing the Marketing Concept in the Nonprofit Sector. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 10: 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Richard, and Floyd Greensleaf. 2000. A History of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. Tellico Plains: Pacific Press Publishing Association. [Google Scholar]

- Shawchuck, Norman, Kotler Philip, and Wrenn Bruce. 1992. Marketing for Congregations: Choosing to Serve People More Effectively. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, Ann, and James F. Devlin. 2000. American and British clergy attitudes towards marketing activities: A comparative study. Service Industries Journal 20: 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Robert, Jeff O. Harris, and Gregory J. Chachere. 1992. Increasing member commitment in a church environment. Journal of Ministry Marketing & Management 2: 69–95. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Robert, David L. Loudon, Henry Cole, and Bruce Wrenn. 2005. Concise Encyclopedia of Church and Religious Organization Marketing. New York: Haworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sułkowski, Łukasz, and Grzegorz Ignatowski. 2020. Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Organization of Religious Behaviour in Different Christian Denominations in Poland. Religions 11: 254. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom, William J. 2012. Public Relations among Christian. Multi-National, Non-Profit Organizations in Europe. Available online: https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/handle/10355/15379 (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- Tilson, Donn J. 2011. Public Relations and Religious Diversity: A Conceptual Framework for Fostering a Spirit of Communitas. Global Media Journal—Canadian Edition 4: 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Uchechukwu, Victoria, and Catherine Ch Eke. 2019. Use of Social Media by Religious Organizations in Nigeria: Lessons for Libraries and Information Centres. Journal of Applied Information Science and Technology 12: 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ukah, Asonzeh. 2003. The Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), Nigeria. Local Identities and Global Processes in African Pentecostalism. Available online: https://epub.uni-bayreuth.de/968/ (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Valaskivi, Katja. 2019. Branding as a Response to the ‘Existential Crisis’ of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland. In On the Legacy of Lutheranism in Finland. Social Perspectives. Edited by Kaius Sinnemäki, Anneli Portman, Jouni Tilli and Robert H. Nelson. Helsinki: Studia Fennica Historica, vol. 25, pp. 309–25. [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe, Michelle C., Anské F. Grobler, Arien Strasheim, and Lizré Orton. 2013. Getting young adults back to church: A marketing approach. HTS Theological Studies 69: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C. Kay, Judy Motion, and Juliet Roper. 2006. From Propaganda to Discourse (and Back Again): Truth, Pawer, the Public Interest and Public Relations. In Public Relations. Critical Debates and Contemporary Practice. Edited by Jacquie L. Etang and Magda Pieczka. Mahwah and London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Marion S., W. Benoy Joseph, Kurt Schimmel, and Christopher Moberg. 1998. Church Marketing: Strategies for Retaining and Attracting Members. Journal of Professional Services Marketing 2: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, Howard B. 1960. What Is Church Public Relations? Ministry. Official Journal of the Ministerial Association of Seventh-Day Adventists 33: 6–7. [Google Scholar]