Abstract

This article tries to highlight the deep doctrinal meanings underlying the vase that is often included in artistic depictions of the Annunciation. This apparently banal everyday object has been deliberately placed there in a prominent position to symbolize the Virgin Mary in her condition as the virginal mother of God the Son, and the bearer of all virtues to the highest degree. As methodological resources to justify our iconographic interpretations of that symbol in these images, our study is based on the analysis of texts by several Church Fathers and medieval theologians, as well as numerous liturgical hymns, which for more than a millennium agreed to designate the Virgin Mary as a “vase”, “vessel”, and other types of containers. Thus, this ancient patristic, theological and hymnographic tradition legitimizes our iconographic interpretation of the “vase” included in fifteen paintings of the Annunciation produced by artists from Italy, Flanders and Spain during the 14th and 15th centuries.

1. Introduction

Before undertaking the exploration in the patristic-theological and liturgical writings that constitute the essential core of this article, it is useful to draw attention to a symptomatic fact: in the famous Lauretan Litanies, a set of invocations and supplications directed in honor of the Virgin Mary, there are three that acclaim her as Vas spirituale (Spiritual Vessel), Vas honorabile (Vessel of honor) and Vas insigne devotionis (Singular vessel of devotion). Indeed, it is surprising that the Church has officially legitimized this triple designation of Mary as a “vessel” or “vase”, additionally qualified as “spiritual”, “of honor” and “of devotion”. What could be the doctrinal bases that would justify this strange triple reference to a vase or vessel to signify the Virgin?

Bearing in mind that these Litanies of Loreto began to take shape in various parts of Christianity as early as the 7th century, until they were almost completely expanded during the 12th century, it seems reasonable to conjecture that they were gradually structured, inspired by the exegetical doctrine that, as we will see later, many Church Fathers, theologians, and liturgical hymnographers had been producing since the 4th century around the metaphor of the vase or vessel as a symbol of the Virgin Mary.

On the other hand, from the 13th century and, above all, from the 14th, many artistic representations of the Annunciation include in the scene a vessel or vase in which a stem of lilies frequently stands.

In view of the apparent correlation between these texts and these images, we will try to explain the possible doctrinal meanings that the vase could have in the context of the Annunciation to Mary. It is not in vain that the History of the Salvation of Humanity begins in this decisive Marian episode, when the human conception/incarnation of God the Son, coming into the world as a man to redeem the fallen humankind, takes place at that moment.

Now, to achieve a correct iconographic interpretation of this vase in the images of the Annunciation, we need to investigate the primary sources of Christian doctrine—especially in the patristic and theological writings, and in the liturgical prayers and hymns—, which are the primary sources that inspire and support the works of Christian art.

On the other hand, we must point out a linguistic precision: since all texts in primary sources that we have found on this subject use the Latin word “vas”, which means “vase”, “vessel”, “jar”, and other forms of “container”, in our article we will translate it almost always, for terminological simplicity, as “vase” or “vessel”.

2. Analyzing Some Patristic-Theological and Liturgical Texts

In this section, we will begin by exposing some exegetical texts of the Church Fathers and medieval theologians that praise the Virgin symbolically designating her as a vessel or an especially valuable vase. In the second part of the section, we will present numerous fragments of medieval Latin liturgical hymns that allude to Mary as a vessel or some other similar container.

2.1. Some Interpretations of Fathers and Theologians Designating Mary as a Vase

Without pretending to be exhaustive, we will present some testimonies from the Church Fathers and medieval theologians who interpret this metaphor of the vase referring to the Virgin from a Mariological perspective. We will first mention some texts of the Greek Patrology, before exposing other similar quotes from Latin Church Fathers and theologians.

Towards the middle of the 4th century, the influential St. Athanasius (295–373), Bishop of Alexandria, in a sermon on the Virgin and her cousin St. Elizabeth, praises Mary for her incomparable greatness, superior to all other greatness, for having been the domicile of the Word of God. He then praises her for being “the ark of the Covenant” covered with gold, an ark which keeps the golden vessel containing the true manna, which is the flesh of Christ in which the godhead of God the Son resides. St. Athanasius establishes here the parallelism—later assumed by many other Christian thinkers—between the ancient Ark of the Covenant, containing the vessel of manna, and the new ark/Mary, whose womb contained the new manna/Christ (the manna in essential relationship with the Eucharist). St. Athanasius of Alexandria is even more explicit in this symbolic allusion to the vessel in a homily on the Virgin, stating: “this glorious and virginal jewel remained totally immaculate: this vessel, which contained the Most High God, was not stained according to heaven, nor was it profaned.”1

Some three decades later, St. Epiphanius of Salamis (310–403) in an apologetic book against heretics reproaches them for attacking this incorrupt Virgin who deserved to be the domicile of God the Son, who was the only one among the infinite number of the Israelites who was chosen to become the containing vessel and the habitation of her divine Son.2 In another passage of this apologetic treatise, St. Epiphanius corroborates that Mary was the true mother of God the Son, from whom he received flesh (human nature) and to whom she gave birth, perpetually preserving her virginity; she is his mother so that the body of God the Son was received from her, and the wonderful vessel of her body received no stain.3

In the first half of the 6th century, the exquisite Byzantine hymnographer St. Romanos the Melodist (c. 485/90–c. 555/62) states in a hymn that the Holy Scriptures call Jesus the manna and the vessel that contains it, others call him the flower that sprouted from the root (of Jesse), while his mother Mary is called a flower, a stem, a door closed forever, who gave birth as a virgin and after childbirth remained a virgin in perpetuity (Cantor 1979). As you can see, Romanos the Melodist prefers to slide towards Christ the symbolic parallelism of the vessel of manna, instead of doing it directly towards Mary, of whom he highlights her virginal divine motherhood, which is what the symbol of the vessel referring to the Virgin means.

Probably around the same 6th century, an anonymous Greek writer assumes several similar ideas in a homily on the Annunciation. After specifying that the angel Gabriel was sent to the most chaste Virgin Mary, whom he honored with the greeting “Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with you” (Lk 1, 28), he praises her as the full of grace, because she is the vessel and the receptacle of supracelestial joy, since she gestated the Creator of the universe in her entrails.4

Towards the end of the 6th century or the beginning of the 7th, Theotecnos, bishop of Livias, in his well-known and prescient writing on Mary’s Assumption to Heaven, declares that no one should distrust the miracle that the most holy body of the Mother of God remained virginal and incorrupt, since that was what was convenient for the one who had been the spiritual ark that contained Aaron’s budded dry rod and the manna (that is, Christ) (Theotecnos 1979). A few lines later, he goes on to say that Mary is the ark, the vessel, the throne and heaven, for which she deserved to see the glory of God face to face. It is interesting to note that Theotecnos, as many other Christian thinkers will do later, uses here the simile of the “ark” as a synonym for “vessel”, in the sense that, just as the ancient Ark of the Covenant contained the tables of the law, the manna and the flowered rod of Aaron (all objects directly linked to God), with even greater reason the Virgin Mary can be designated as an “ark”, for having been a “vessel” or “container” that housed (conceived, gestated, and gave birth) to God the Son incarnate as a man.

In the second half of the 7th century or in the first decades of the 8th, St. Germanus, Patriarch of Constantinople (c. 634–733/40), in a sermon on the Presentation of Mary to the temple, extols her with these praises: “God save you, urn forged with pure gold, and containing the sweetest sweetness for our souls, which is the manna [Christ].”5 In another homily on the Annunciation, he expresses similar praises, noting: “God save you, full of grace, urn all of gold containing the manna, and tabernacle really made of purple.”6 In his third sermon on the Dormition of the Virgin, Germanus of Constantinople imagines Jesus telling his dying mother Mary that death will not boast with her, because she conceived him in her womb, and was made the vessel containing God the Son, so neither death nor darkness would affect her. With these sentences, St. Germanus of Constantinople indistinctly shuffles the metaphorical figures “urn”, “tabernacle”, “vessel”—all of them container instruments of a sacred nature and function—as alternative symbols to designate Mary, who, as the Mother of God the Son incarnate, contains/houses/protects the divine Christ in her entrails.

In the first half of the 8th century, the famous apologist St. John Damascene (675–749), in his second homily on the Nativity of Mary, praised her with these lyrical terms: “God save you, urn, vessel made of gold, secret of every vessel, and with which the whole world received for itself the manna, that is, the bread baked with the fire of divinity.”7 In his first homily on Mary’s Dormition, the Damascene insists on praising the Virgin with these words:

God save you, candelabrum, golden and solid vessel of virginity, whose wick is the grace of the Spirit, and the oil of that holy body, which was assumed from your immaculate flesh; from which Christ [was born], light that knows no sunset; which you kindled to everlasting life for those who once sat in darkness and in the shadow of death.8

Again, the Damascene moves between the synonyms “urn”, “vessel” and even “candelabrum” to metaphorically designate Mary as “container” or “sustainer” of the deity.

Around the middle of the 9th century, the fine Greek-Byzantine poet St. Joseph the Hymnographer (c. 816–886) proclaimed in a canticle in honor of the Virgin: “Oh, Mary, the purest tabernacle of the Word, purify my heart from all evil affections, and, the vessel of the divine Spirit, make this world praise you and magnify you, who are the worthiest of all praise.”9

Perhaps around the same decades, George of Nicomedia (9th century), in his fifth sermon on the Presentation of Mary to the Temple, affirms that when her parents took her to the temple at the age of three, they were carrying this supreme and cleanest vessel of the treasure of grace, the spotless vessel, the receptacle of light, from which the rays of salvation (Christ) shone for the whole world.

Analogous to these Greek-Eastern interpretations, we now present another selection of exegetical statements by Latin writers who coincide in interpreting the metaphors under study.

In the second half of the 6th century, the Italian poet St. Venantius Fortunatus (c. 530–c. 607/9), Bishop of Poitiers, praises the Virgin in a hymn in her honor with these verses:

- Image of the model, decorum on all vessels,

- and gleaming mass of the new creature.

- Pure candelabrum, containing the lamp of the Word,

- To whom the Maker carved a form so superior to the stars,

- Gracious beauty that adorns the holy Jerusalem,

- Vessel standing in front of the temple in honor of God.10

Around the middle of the 7th century, St. Ildefonsus (607–667), bishop of Toledo, in an apologetic book on the perpetual virginity of Mary, after stating that “Certainly her virginity is always incorrupt, always whole, always unharmed, always inviolate”, asserts that “This woman is the vessel of sanctification, the eternity of the virginity [the perpetual virginity], the mother of God, the tabernacle of the Holy Spirit, the singularly unique temple of her Creator.”11

In the second half of the 11th century, the Benedictine St. Anselm of Aosta (1033–1109), Archbishop of Canterbury, in a prayer imploring the love of Mary and of Christ, praised the Virgin with these poetic concepts:

The hall of universal propitiation, the cause of general reconciliation, the vessel and the temple of life and of the salvation of everybody, I certainly collect your merits, when I review your benefits singularly on me, a little man, which the world that loves enjoy, and claim enjoying being his.12

In a hymn in honor of the Virgin St. Anselm proclaims:

- The heaven of heaven, the house of God,

- The vessel of mercy.

- But it exists for you prone

- and completely easy.13

In the first half of the 12th century, St. Amadeus, bishop of Lausanne (c. 1110–1159), in his third homily on the conception and incarnation of Christ, designates the Virgin Mary as “the most precious and holiest vessel in which the Word of God was conceived.”14

At the beginning of the 13th century, the distinguished Franciscan thinker St. Anthony of Padua (1195–1231) expressed in a sermon in honor of the Virgin Mary:

Blessed Mary is called a “vessel” because she is “the bedchamber of the Son of God, the special shelter of the Holy Spirit, the triclinium of the Holy Trinity.” That is why she says in the book of Wisdom: “He who created me rested in my tabernacle”.(24, 14. In Nocilli 1995, p. 157)

This “vessel” of Mary was an admirable work of the Most High Son of God, who made her more beautiful than all mortals, holier than all saints: in her “the Word became flesh and came to dwell in our midst”.(John 1:14)15

Approximately half a century later, the also Franciscan St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio (c. 1217/21–1274), an influential theologian and philosopher who, due to his pure mysticism, was known as the Seraphic Doctor (Doctor Seraphicus), brings some similar concepts in his fourth sermon on the Annunciation. After quoting St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who said that the Virgin Mary had been blessed by God with a supreme sanctification at her birth and in her later life, immune from all sin, St. Bonaventure points out:

This was well symbolized in the last chapter of Exodus, in the figurative tabernacle, when Moses is told: You shall anoint the tabernacle and its vessels; and goes on to say later. And when all these things were finished, a cloud covered the tabernacle of the testimony, and everything was filled with the glory of the Lord. This tabernacle is the Virgin Mary, and the vessels are the receptacles of the virtues. The Son of God anointed them when, sanctifying the Virgin, he filled her with grace, and after sanctifying her, he covered her with his shadow and protected her with glory, so that neither in soul nor in body part remained that was not full of the grace of the Deity.16

In his Sermon 5 in honor of Mary, St. Bonaventure states: “That is why the flesh of the Virgin is designated as the purest vessel, because in her flesh neither sin reigned, nor did the flesh rebel against the spirit, nor did the flesh retard the spirit; and for that reason she was not only pure, but the purest.”17 In another Marian sermon, the Seraphic Doctor insists on similar concepts about the Virgin symbolized as a vessel, with a series of ingenious disquisitions that it is not possible to comment on in this brief article. As a synthesis of the approach of the Franciscan master in this last sermon, we can only present this quote:

But the royal maiden [Mary] was an admirable vessel because of her matter; because of its form, and because of its content. Because of the matter it was an admirably precious vessel; because of its shape it was an admirably beautiful vessel; but because of its contents it was an admirably abundant vessel.18

2.2. Invocations to the Virgin Mary as a Vase in Some Medieval Liturgical Hymns

As expected, this solid and multi-secular exegetical tradition established by the Fathers and theologians of the Eastern and Western Churches, by unanimously interpreting the metaphor of the “vase” as a clear symbol of the Virgin Mary, will take shape too in the Middle Ages in countless devotional prayers and liturgical hymns. We will now give some examples of these liturgical testimonies.

In this regard, we are fortunate that from 1853 to 1922 the conspicuous German historians Franz Josef Mone, Guido María Dreves and Clemens Blume compiled, transcribed and published in critical editions many of these Latin liturgical hymns in two monumental collections of indispensable reference. A pioneer in this field was Franz Josef Mone, who between 1853 and 1855 collected and edited many hymns in the three volumes of his collection Hymni Latini Medii Aevi: the first of them, dedicated to God (Mone 1853); the second, to the Virgin Mary (Mone 1854); the third, to the saints (Mone 1855). For this reason, in our article we will consider the second volume, dedicated entirely to Mary.

Immediately after Mone, Guido Maria Dreves edited between 1886 and 1898 the first 28 volumes of the impressive collection Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi (AHMA 55 volumes in all), the next 22 volumes of which he published from 1898 to 1907 alone or co-authored with Clemens Blume. Blume then continued this collection until 1922 with its last 5 volumes.

Thus, these two great collections of medieval liturgical hymns serve us to compose the sequence of stanzas that we present below, in which Mary appears designated as “vase”, “vessel”, “container”, “urn”, or some other analogous type of receptacle. We will cite these liturgical hymns with the numbering and the title with which they appear catalogued in the collections Hymni Latini Medii Aevi (Mone 1854) and Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi (AHMA). On the other hand, we will present these stanzas in chronological order, grouping them by centuries, to try to appreciate any possible evolution in the symbolic treatment applied to Mary over the centuries.

2.2.1. Hymn of the 10th Century

From the 10th century, we have only been able to document Hymnus 3. De nativitate Beatae Mariae Virginis, which in one of its stanzas poetically expresses the role of Mary as Mother of the Redeemer, stating:

- Merito debuerat

- Benedicta scribi,

- Qua deletus fuerat

- Morbus primi cibi,

- Deus hanc voluerat,

- Ut maneret ibi,

- Vas generale suis.

- vas speciale sibi.

(Hymnus 3. AHMA 2, Dreves 1886, 123)

- Deservedly should

- Be blessed to the scribe

- The one with which

- The sickness of the first meal [Adam and Eve’s apple]

- would be eliminated,

- God would like that

- She stayed there

- As a general vessel for yours,

- And as a special vessel for him.

2.2.2. Hymn of the 11th Century

From this century, we have only found, in reference to the analyzed subject, Hymnus 68. In Assumptione Beatae Mariae Virginis, which in brief verses praises the mother of God as follows:

- 6a. Genus regale,

- Vas spiritale.

- 6b. Templum virginale,

- Donum speciale.

(Hymnus 68. AHMA 9, Dreves 1890, 56)

- 6a. Royal lineage,

- Spiritual vessel.

- 6b. Virginal temple,

- Special gift.

2.2.3. Hymns of the 10th–12th Centuries

From an uncertain date in the interval between the 10th and 12th centuries, we have found Hymnus 82. De Beata Maria Virgine, which acclaims in these terms the favorite of the divine Trinity, the mother of God the Son:

- 11a. Tu vas imbutum nectare

- Virtutum, sine compare

- Tu trinitatis templum.

- 11b. Tu aequitatis semita,

- Humilitatis orbita,

- Munditiae exemplum.

(Hymnus 82. AHMA 9, Dreves 1890, 68)

- 11a. You are the vessel full of nectar

- Of the virtues, you are the incomparable

- Trinity Temple.

- 11b. You are the path of equity,

- The orbit of humility,

- The example of purity.

2.2.4. Hymns of the 12th Century

Dated from the 12th century, we have found these two hymns.

Hymnus 145. De Beata Maria Virgine exalts the Virgin with various symbols, among them that of the “vessel”, when pointing out:

- 7a. Porta clausa, fons hortorum,

- In qua sedit rex coelorum

- Nulli viro pervia.

- 7b. Nardus spirans, flos odorum,

- Odor floris, vas decorum,

- Cella pigmentaria.

(Hymnus 145. AHMA 10, Dreves 1890, 110)

- 7a. Closed door, source of the orchards,

- In which the King of heaven sat,

- And it is not passable for any male.

- 7b. Nard exhalant of smell, flower of smells,

- Smell of flower, honorable vessel,

- Aroma cell.

Hymnus 150. De Beata Maria Virgine praises the mother of God the Son, designating her as a “vessel” of various kinds and qualities, saying:

- 4a. Dextra Dei vas politum,

- Vas purgatum, vas ambitum

- Castitatis circulo.

- 4b. Ut prophetae praedixere,

- Vas electum continere

- Deum matris gremio.

(Hymnus 150. AHMA 10, Dreves 1890, 113)

- 4a. Vessel polished by the right hand of God,

- Purified vessel, vessel circled

- by the circle of chastity.

- 4b. As the prophets foretold,

- The chosen vessel contains

- To God in the mother’s womb.

2.2.5. Hymns of the 13th Century

Dating from the 13th century, we have found the following four hymns alluding to the subject under study:

Hymnus 5. In Adventu pleads with the mother of the Redeemer in these warm stanzas:

- 8a. O Maria, vas pudoris,

- Nostri mater salvatoris

- Hac in die tu Messiae

- Servos reconcilia;

- 8b. Ut quos ipse jam redemit

- Et cruore suo emit,

- Prece tua nos ad sua

- Reducat palatia.

(Hymnus 5. AHMA 8, Dreves 1890, 14)

- 8a. Oh, Mary, vessel of modesty,

- mother of our Savior,

- On this day reconcile your servants

- With the Messiah.

- 8b. So that he leads to his palaces

- by your prayers

- those whom he has already redeemed

- And he ransomed with his blood.

Hymnus 365. De beata Maria virgine extols Mary for her virginal divine motherhood that way:

- Rubus urens,

- Non comburens,

- Vas signatum,

- Vas ditatum,

- vas imbutum

- melle et balsamo:

- non te laedit,

- dum procedit

- sol de stella,

- rex de cella,

- virginalis sponsus

- de thalamo.

(Hymnus 365. Mone 1854, 58)

- Burning bush,

- that is not consumed,

- Sealed vessel,

- Enriched vessel,

- Vessel full

- of honey and balm:

- It doesn’t hurt you

- as long as the sun

- proceeds of the star,

- the king [leaves] the royal hall

- and the virginal husband

- [comes out] of the nuptial bed.

In the Hymnus X. Psalterium Beatae Mariae Virginis, auctore Edmundo Cantuariensi. Secunda Quinquagena, its author, Edmund of Canterbury, celebrates the Virgin as the mother of the Redeemer in these expressive terms:

- Ave, per quam

- fit Deo subdita

- Gens aeterno

- tormento dedita,

- Per te gentes

- salvavit perditas

- Calceata

- carne divinitas,

- O vas deitatis.

(Hymnus X. AHMA 35, Blume, Dreves 1900, 141)19

- Hail, by whom

- the human people,

- Delivered to torment,

- became a subject of God,

- For you, O vessel of the Deity,

- The Deity

- coated with flesh

- saved the lost people.

Hymnus I. Psalterium beatae Mariae Virginis. Secunda Quinquagena sings to the mother of God the Son with these poetic concepts:

- Ave, verbi vas arcanum

- Mundo ferens caeli granum,

- Cuius odor reddit sanum,

- Cuius sapor ius profanum

- Prorsus tollit, quod per manum

- Primae matris hausimus.

(Hymnus I. AHMA 36, Blume, Dreves 1901, 20)

- Hail, arcane vase of the Word,

- That brings to the world the grain of heaven,

- whose smell heals,

- Whose taste completely removes

- the profane right we extracted

- By the hand of our first mother [Eve].

2.2.6. Hymns of the 12th–15th Centuries

Datable approximately to some imprecise date of this long interval of three centuries, we have found two hymns:

Hymnus 101. De Beata Maria Virgine, c. 12th–13th centuries, applauds the excellence of the Virgin thus:

- Tu vas mannae sanctioris,

- Vas dulcoris et honoris

- Habens privilegium.

(Hymnus 101. AHMA 8, Dreves 1890, 81)

- You are the vessel of the holiest manna,

- the vessel of sweetness and honor,

- who has privilege.

Hymnus 53, datable to some dubious date between the 13th and 15th centuries, celebrates Mary’s virginal divine motherhood with this lyrical stanza:

- Pudoris signaculum,

- Servans illibatum

- Et quem virgo concipit,

- Virgo parit natum.

- Non decet vas flosculi

- Esse defloratum,

- Neque inde tollere

- Matris coelibatum.

(Hymnus 53. AHMA 1, Dreves 1886, 92)

- Preserving immaculate

- the seal of virginity,

- The Virgin gives birth to a Son,

- Whom she conceives while a virgin.

- It is not convenient that the vase of the little flower

- be deflowered,

- Nor that, therefore, it is removed

- The celibacy of the mother.

2.2.7. Hymns of the 14th Century

Dated to the 14th century we have found numerous hymns alluding to the subject.

An untitled hymn acclaims Mary with these metaphorical figures:

- Ave sidus clarissimum,

- templum dei sanctissimum,

- virtutum vas mundissimum,

- Maria mater Christi.

(Untitled hymn. Mone 1854, 108)

- Hail, very clear star,

- the Holiest Temple of God,

- the clean vase of virtues,

- Mary, the mother of Christ.

Hymnus 401. Ave Maria commends the Virgin through these terms:

- Gratia plena te perfecit

- spiritus sanctus, dum te fecit

- vas divinae bonitatis

- et totius largitatis.

(Hymnus 401. Mone 1854, 111)

- The Holy Spirit perfected you

- Like the full of grace, while he made you

- The vessel of divine goodness

- And of total generosity.

Hymnus 465. De gaudiis beatae virginis Mariae celebrates the glory of the mother of God the Son with this stanza:

- Gaude splendens vas virtutum,

- cujus pendens est ad nutum

- Tota coeli curia,

- Te benignam et felicem,

- Jesu dignam genitricem,

- venerans in gloria.

(Hymnus 465. Mone 1854, 176)

- Rejoice, splendid vessel of virtues,

- From whom all heavenly curia

- is pending at the slightest sign,

- Worshiping you in glory

- Like the benign and happy

- Worthy mother of Jesus.

Hymnus 325. Conceptio beatae Mariae virginis exalts the divine motherhood of Mary by stating:

- Aurora lucis oritur,

- conceptio recolitur

- Mariae, quae verbigenae

- Vas est provisae gratiae.

(Hymnus 325. Mone 1854, 7)

- The dawn of light is born,

- the conception of Mary is considered,

- who is the vessel that begets the Word

- who provided the grace.

Hymnus 2. Crinale Beatae Mariae Virginis pleads for the repairing help of the Virgin with these lyrical verses:

- Gaude schola disciplinae,

- Glossa legis, fons doctrinae,

- Vas coelestis medicinae,

- His, quos culpae pungunt spinae,

- Funde medicamina.

(Hymnus 2. AHMA 3, Dreves 1888, 24)

- Rejoice, school of discipline,

- Gloss of the law, source of the doctrine,

- Vessel of heavenly medicine,

- To these, whom the thorns of guilt pierce,

- Produce medicines.

Hymnus 5. De Beata Maria Virgine et Sancto Johanne evangelista celebrates the mother of God the Son with these inspired praises:

- Salve, mater Salvatoris,

- Vas electum, vas honoris,

- Vas coelestis gratiae,

- Ab aeterno vas provisum,

- Vas insigne, vas excisum

- Manu sapientiae.

(Hymnus 5. AHMA 3, Dreves 1888, 117)20

- Hail, mother of the Savior,

- Chosen vessel, vessel of honor,

- Vessel of the heavenly grace,

- Vessel prearranged from eternity,

- Insigne vessel, vessel chiseled

- By the hand of Wisdom.

Hymnus 49. De Beata Virgine Maria glorifies the Virgin with these imaginative compliments:

- O regina regni Dei,

- O coelestis vas diei,

- Verbi Dei felix aula,

- Coeli melos et coraula.

(Hymnus 49. AHMA 4, Dreves 1888, 38)

- Oh, Queen of the kingdom of God,

- Oh, vessel of heavenly day,

- the happy throne room of the Word of God,

- the song and the choir of heaven.

The Hymnus 34. De sancta Anna. In 1 Nocturno. Antiphonae applauds the birth of the Virgin Mary with these verses:

- Hinc nascitur de gratia

- Vas juste plenum gratia,

- Pro cujus abundantia

- Mensuram transit copia.

(Hymnus 34. AHMA 5, Dreves 1892, 106)

- From here the vessel just full of grace,

- is born by grace

- for whose abundance

- Pass the measure abundantly.

Hymnus 86. De Beata Maria Virgine glorifies the mother of the Savior with these eloquent metaphors:

- 1a. Salve, stella, mundi lumen,

- Salve, cella celans numen,

- Salve, decus gloriae;

- 1b. Splendor rerum et cacumen,

- Vas sincerum, pons, et flumen

- Aromatum gratiae.

- 2a. O coelestis figuli

- Vas desiderabile,

- 2b. Vas medelae saeculi,

- Vas decens, vas utile,

- 3a. O Maria, gratia

- Plena sancti spiritus,

- 3b. Dux in via praevia,

- Lux praefulgens coelitus.

(Hymnus 86. AHMA 9, Dreves 1890, 70)

- 1a. Hail, star, light of the world

- Hail, cell that hides the Godhead,

- Hail, honor of glory;

- 1b. Splendor and summit of things,

- Sincere vessel, bridge and river

- Of the aromas of grace.

- 2a. Oh, desirable vessel

- Of the celestial modeled [Christ].

- 2b. World Medicine Vessel,

- Convenient vessel, useful vessel,

- 3a. Oh Mary, full

- Of the grace of the Holy Spirit,

- 3b. Guide on the previous path,

- Light that shines the heavenly.

Hymnus 89. De Beata Maria Virgine celebrates the virginal divine maternity of Mary with these eloquent metaphors:

- 4a. Tu puella sola prolem,

- Sola paris stella solem

- De Jacob egrediens;

- 4b. Tu figulum contra ritum

- Concepisti, vas politum,

- Vas laesuram nesciens.

(Hymnus 89. AHMA 9, Dreves 1890, 73)

- 4a. You are the only virgin who gives birth,

- The only star that gives birth to the Sun,

- Which proceeds from Jacob;

- 4b. You, clean vessel,

- Vessel that knows no injury,

- You conceived a child against the norm.

Hymnus 91. De Beata Maria Virgine highlights the virginal divine motherhood of Mary through these expressive symbolic figures:

- 2a. Summi regis palatium,

- Thronus imperatoris,

- Sponsi reclinatorium,

- Tu sponsa creatoris.

- 2b. O pauperum solatium,

- Remedium languoris,

- Dignum Dei sacrarium,

- Vas aeterni splendoris.

(Hymnus 91. AHMA 9, Dreves 1890, 74)

- 2a. Supreme King’s Palace,

- Emperor’s Throne,

- husband’s kneeler,

- You are the wife of the Creator.

- 2b. Oh, consolation of the poor,

- Remedy of the weakness,

- worthy tabernacle of God

- Vase of eternal splendor.

The Hymnus 73. From Gaudiis Beatae Mariae Virginis commemorates the divine motherhood of Mary, whose saving help it begs in these verses:

- Gaude, florens virgo Jesse,

- Ecce Deus fecit esse

- Florem et amygdalum,

- Vas insigne plenum melle,

- Omne malum procul pelle,

- Aufer omne scandalum.

(Hymnus 73. AHMA 15, Dreves 1893, 100)

- Rejoice, flourishing Virgin of Jesse,

- Behold, God made you to be

- flower and almond,

- Distinguished vase full of honey,

- Throw away all evil,

- Eliminate all scandal.

Hymnus 103. Ad Beatam Mariam Virginem extols the Virgin with these praises:

- Ave, Jesse flos pudoris,

- Pia proles, vas honoris,

- Fons dulcoris, stilla roris.

(Hymnus 103. AHMA 15, Dreves 1893, 129)

- Hail, modest flower of Jesse,

- Pious offspring, vessel of honour,

- Source of sweetness, drop of dew.

Hymnus IX. Psalterium beatae Mariae Virginis, auctore Engelberto Admontensi. Oratio praeambula ad secundam Quinquagenam expresses the sublimity of the Mother of God with these lyrical verses:

- O vas mellis expers fellis,

- Cinnamomo et amomo

- Nomen habens dulcius,

- Post tuorum unguentorum

- Vel odorem vel dulcorem,

- Fac, ut currem citius.

(Hymnus IX. AHMA 35, Blume, Dreves 1900, 135)21

- O vase of honey devoid of gall,

- who has a sweeter name

- than cinnamon and balm,

- make me run faster

- after the smell or after the sweetness

- of your ointments.

2.2.8. Hymns from between the 14th and 15th Centuries

Related to the topic we are studying, we have found these three hymns written between the 14th and 15th centuries:

Hymnus 52. Salutationes Beatae Mariae Virginis sings to the virginal mother of the Son of God with these eloquent metaphors:

- Salve, nostri vas salutis,

- Arca vere, vas virtutis,

- Vas coelestis gratiae;

- Vas ad unguem levigatum,

- Vas decenter fabricatum

- Manu sapientiae.

(Hymnus 52. AHMA 15, Dreves 1893, 69)

- Hail, vessel of our salvation,

- Ark truly, vessel of virtue,

- Vessel of heavenly grace;

- vessel levigated with the greatest care,

- decently made vessel

- By the hand of Wisdom.

Hymnus XIV. Psalterium beatae Mariae Virginis. Tertia Quinquagena praises the mother of God with these expressive verses:

- Ave, virgo virginum,

- mater salvatoris,

- Vas electum Domini,

- titulus amoris,

- Vas Dei altissimi

- nostri redemptoris,

- Angelorum domina,

- sponsa creatoris.

(Hymnus XIV. AHMA 35, Blume, Dreves 1900, 216)

- Hail, Virgin of virgins,

- Mother of the Savior,

- Chosen vessel of the Lord,

- love title,

- Vessel of the Most High God

- Our Redeemer,

- Lady of the angels,

- Creator’s Wife.

An untitled hymn, from around the 15th century, states:

- Ave, virgo, vas ornatum,

- Soli Deo vas sacratum,

- Lingua mea te laudabit,

- Os extollet, cor cantabit.

(Untitled hymn. Mone 1854, 249)

- Hail, Virgin, ornate vase,

- sacred vessel only for God

- my tongue will praise you,

- my mouth will praise you, my heart will sing to you.

Hymnus 522. De Beata Maria, datable to the 15th century, enounces:

- Salve, mater Salvatoris,

- Vas electum creatoris,

- Decus coeli civium;

- Salve, virgo benedicta,

- Per quam terra maledicta

- Meruit remedium.

(Hymnus 522. Mone 1854, 307)

- God save you, mother of the Savior,

- Creator’s chosen vase,

- Honor of the heavenly citizens;

- God save you, blessed Virgin,

- For whom the earth cursed

- He deserved remedy.

2.2.9. Hymns of the 15th Century

As expected, most hymns we have found related to our topic date from the 15th century.

Hymnus 507. Oratio, quae dicitur crinale beatae Mariae virginis proclaims the virginal divine motherhood of Mary with these suggestive metaphorical figures:

- Vale, urna, manna, merum,

- panem coeli portans verum,

- Qui conservat cor sincerum

- Et in finem est dierum

- Omnibus sufficiens.

(Hymnus 507. Mone 1854, 269)

- Be well, urn, manna, pure wine,

- That you carry the true bread from heaven,

- that keeps the sincere heart

- And it’s enough for everyone

- At the end of time.

Hymnus 509. Deliciae Mariae virginis hails the immaculate mother of God with these warm notions:

- Salve, tantae puritatis

- Vas, ut regem majestatis

- De supernis traheres,

- Gabriele nuntiante

- Inaudita post et ante

- Nuntia susciperes.

(Hymnus 509. Mone 1854, 280)

- Hail! vessel of such great purity,

- As for you to bring from heaven

- To the King of majesty [Christ],

- And with Gabriel’s announcement

- receive some good news

- Never heard before or after.

Hymnus 510. Ad beatam Mariam virginem praises the Virgin with these lyrical tropes:

- Ave, vas sinceritatis,

- Lux lucens in tenebris,

- Ave stella claritatis,

- Luna sine nebulis.

(Hymnus 510. Mone 1854, 284)

- Hail, vessel of sincerity,

- Light that illuminates in the darkness,

- Hail, star of clarity,

- Moon without fog.

Hymnus 511. Salutationis beatae Mariae virginis celebrates the mother of the Son of God with these illustrative metaphors:

- Ave, vas clementiae,

- gratiae piscina,

- Radix innocentiae

- Stella matutina,

- Palmaque victoriae,

- vitae medicina,

- vitis abundantiae,

- Coelorum regina.

(Hymnus 511. Mone 1854, 289)

- Hail, vessel of mercy,

- grace pool,

- root of innocence,

- Morning Star,

- And palm of victory,

- medicine of life,

- vine of abundance,

- Queen of heaven.

Hymnus 525. Sequentia de beata virgine Maria rejoices the greatness of the mother of God the Son with this eloquent figure:

- Tu auri vas solidum,

- Vas ornatum fulgidum,

- Quod decore praeeminet.

(Hymnus 525. Mone 1854, 312)

- You, solid vase of gold,

- Ornate and shining vase,

- Which stands out for its beauty.

Hymnus 539. Ad eandem [Mariam] glorifies the Virgin with these imaginative metaphors:

- Apellaris maris

- Fulgens stella, cella

- Regis, legis

- Novae speculum;

- Tu vasculum

- Aromaticum,

- Coeli tripudium.

(Hymnus 539. Mone 1854, 329–30)

- You are told shining

- Star of the sea, room

- of the King, mirror

- Of the new law;

- you are

- the aromatic little vase,

- The favorable omen from heaven.

Hymnus 601. Hortus rosarum Dei genitricis Mariae praises and supplicates the Virgin in these warm verses:

- Tu panis vas et olei,

- Columna nostrae fidei,

- Nos dulcora sine mora

- Poli roris cellula.

(Hymnus 601. Mone 1854, 415)

- You are the container of bread and oil,

- the column of our faith,

- Sweeten us without delay

- with the abundance of heavenly dew.

Hymnus 604. De laudibus beatae virginis Mariae proclaims the saving help of the mother of God in this stanza:

- Vas electum Creatoris,

- medicina peccatoris,

- Super choros angelorum

- Exaltata, spes lapsorum.

(Hymnus 604. Mone 1854, 421)

- Creator’s chosen vessel,

- sinner’s medicine,

- exalted above the choirs of angels,

- hope of the fallen

- Oh, vessel of honey, exempt from gall,

- Which has a sweeter name

- That cinnamon or amomo:

- make me run faster

- After the smell and the sweetness

- Of your ointments!

Hymnus 607. Laus Mariae acclaims the excellence of the virtues of and the divine motherhood of Mary with these verses:

- Vas decoris et honoris,

- Vas coelestis gratiae,

- Templum nostri Redemptoris,

- Forma pudicitiae.

(Hymnus 607. Mone 1854, 426)22

- Vessel of virtue and honor,

- Vessel of heavenly grace,

- Temple of our Redeemer,

- form of modesty

Ulrich Stocklins von Rottach (Udalricus Wessofontanus), in his Hymnus 45. Abecedarius 5, calls for the saving aid of the virtuous Mother of God the Son with these expressive words:

- Vas coelestis gratiae

- Vasque pietatis,

- Semper omni specie

- Carens foeditatis,

- Onus et tristitiae

- Nostrae gravitatis

- Oleo laetitiae pelle

- Cum peccatis.

(Hymnus 45. AHMA 6, Dreves 1889, 148)

- Vessel of heavenly grace

- And vessel of mercy,

- always lacking

- of all forms of ugliness,

- expel the load of our gravity

- of sadness

- with the oil of joy

- with the sins.

Ulrich Stocklins von Rottach, in his Hymnus 17. Acrostichon super Ave Maria, requests the protection of the merciful Mother of the Savior with this stanza:

- Ave, mater gratiae,

- Mater pietatis,

- Vas misericordiae,

- Vas divinitatis,

- Evae prolem respice,

- Fons benignitatis,

- Mundans nos a crimine

- Nostrae pravitatis.

(Hymnus 17. AHMA 6, Dreves 1889, 49)

- Hail, mother of grace.

- Mother of mercy,

- vessel of mercy,

- Vessel of Deity,

- Look at the offspring of Eve,

- Source of kindness,

- clearing us of crime

- of our wickedness.

Again, Ulrich Stocklins von Rottach, in his Hymnus 25. Laudatorium Beatae Virginis Mariae. Pars tertia. Ad Primam, extols the merciful mother of God, whose saving help he beseeches in those moving verses:

- Salve, vas clementiae

- Ac benignitatis,

- Vas coelestis gratiae,

- Vas divinitatis,

- Da misericordiae

- Manum tribulatis,

- Per donum laetitiae

- Et prosperitatis.

(Hymnus 25. AHMA 6, Dreves 1889, 95)

- Hail, vessel of mercy

- And kindness,

- Vessel of heavenly grace,

- Vessel of Deity,

- Give to the troubled

- the hand of mercy,

- Through the gift of joy

- And prosperity.

Once again Ulrich Stocklins von Rottach, in his Hymnus 25. Laudatorium Beatae Virginis Mariae. Sexta pars. Ad Nonam, celebrates the virginal divine motherhood of Mary with these poetic expressions:

- Salve, vas mirabile

- Minime extensum,

- Tamen ineffabile

- Verbum es immensum

- Continens, id nobile

- Carmen sic expensum

- Tibi acceptabile

- Sit velut incensum.

(Hymnus 25. AHMA 6, Dreves 1889, 104)

- Hail, admirable vessel

- minimally extended,

- And yet ineffable,

- You are the one that contains

- To the immense Word, this noble

- Poem so carefully weighed

- be acceptable to you

- Like incense.

Lastly, Ulrich Stocklins von Rottach, in his Hymnus 25. Laudatorium Beatae Virginis Mariae. Septima pars. Ad Vesperas, commends the privileged dignity of the mother of the Lord, whose intercession before her divine Son requests in these terms:

- Gaude, vas mirabile,

- Continens immensum

- Verbum nec sensibile

- Hominis per sensum,

- Melos istud sedule

- Tibi sic impensum

- Mihi placet frivole

- Dominum offensum.

(Hymnus 25. AHMA 6, Dreves 1889, 108)

- Rejoice, admirable vessel,

- which contains the immense

- Verb not perceivable

- By the sense of man,

- This song is for you

- carefully vehement

- And please me frivolously

- To the offended Lord.

Hymnus 13. In Nativitate Domini Nostri sings of the virginal divine motherhood of Mary with these illustrative expressions:

- 6a. Vas insigne, vas probatum,

- Templum Deo dedicatum,

- In quo Deus clausit natum,

- Sicut docet litera.

- 6b. Templum intus adornatum

- Talem habet principatum,

- Quod non fuit violatum

- Et parit puerpera.

(Hymnus 13. AHMA 10, Dreves 1891, 17)

- 6a. Insigne vessel, proven vessel,

- Temple dedicated to God,

- In which God shut himself up at birth,

- As the [Holy] Scripture teaches.

- 6b. Ornate temple inside

- Has such principality,

- that was not raped

- And gives birth as a parturient.

Hymnus 137. De Beata Maria Virgine praises the divine motherhood of Mary with these affectionate metaphors:

- 1a. Ave, mater genitoris.

- Via vitae, vas decoris,

- Lilium munditiae,

- 1b. Stella maris, sol splendoris,

- Veri virgultum amoris,

- Paradisus gratiae.

(Hymnus 137. AHMA 10, Dreves 1891, 105)

- 1a. Hail, mother of the Father,

- Path of life, vessel of decorum,

- lily of purity

- 1b. Star of the sea, sun of splendor,

- Stem of true love,

- paradise of grace

Hymnus 48. De Conceptione Beatae Mariae Virginis. Ad Vesperas extols the virginal divine motherhood of Mary with these illustrative verses

- Ut infractum perforatur

- Radio vas vitreum,

- Nec in partu reseratur

- Conclave virgineum,

- Et chaos tartareum.

(Hymnus 48. AHMA 11, Dreves 1891, 36)

- Just like the vase

- is pierced without breaking

- by the ray of light,

- That way the closure of virginity

- doesn’t open at birth

- And the emptiness of hell.

Hymnus 94. Acrostichon super “Ave Maria” glorifies the Virgin as the beloved mother of God through these poetic analogies:

- Summus artifex omnium

- Te providet, vas nobile,

- Vas dignum, vas egregium,

- Vas gratum, vas laudabile,

- Vas cunctis venerabile.

(Hymnus 94. AHMA 15, Dreves 1893, 118)

- The Supreme Creator of the universe

- organizes you in advance, noble vessel,

- Worthy vessel, egregious vessel,

- Pleasant vessel, laudable vessel,

- Venerable vessel for all.

Hymnus 110. Ad Beatam Mariam Virginem exalts the virginal divine motherhood of Mary with these poetic symbolic expressions:

- Verbi patris atrium,

- Vas provisum carum,

- Pneumatis palatium,

- Trium personarum

- Simplex hoc triclinium.

(Hymnus 110. AHMA 15, Dreves 1893, 138)

- Atrium of the Word of the Father,

- dear vessel arranged in advance,

- Palace of the [Holy] Spirit,

- This is the simple triclinium

- Of the three [divine] Persons.

The Hymnus 36. In Conceptione Virgnis Mariae Beatae. Ad Vesperas sings of Mary as the virginal mother of God the Son through these vivid rhymes:

- 1. Ave, fluens mella,

- Trinitatis cella,

- Melos et laus oris,

- Flos fragrantis floris.

- 2. Alvo senectutis

- Conceptae virtutis

- Vas et lucis via,

- Genitrix Maria.

(Hymnus 36. AHMA 16, Dreves 1894, 44)

- 1. Hail, flowing honey,

- Trinity Room,

- Song and praise of the mouth,

- Flower of fragrant flower.

- 2. From the womb of old age

- Conceived of virtue,

- Vessel and path of light,

- Mother Mary.

2.2.10. Hymns with No Documented Date

We have also found these three hymns, whose dating we could not specify:

Hymnus 597. Laudes Mariae applauds to the Virgin with these delicate verses:

- O Maria, maris stella

- plena gratiae,

- mater simul et puella,

- vas munditiae.

(Hymnus 597. Mone 1854, 409)

- Oh, Mary, star of the sea

- Full of grace,

- Mother and at the same time virgin,

- Vessel of purity.

Hymnus 42 exalts the Virgin for her eximious virtues that way:

- O vas deitatis,

- Tu fons pietatis,

- Manans largiter.

(Hymnus 42. AHMA 1, Dreves 1886, 87)

- Oh, vessel of divinity,

- You are the source of mercy,

- That you flow with abundance.

Hymnus 90. Jubilus de singulis membris Beatae Mariae Virginis begs for the protective assistance of the mother of God with these expressive verses:

- Vas repletum cunctis donis,

- Patens malis atque bonis,

- Dans pacis beneficia,

- In hoc vase me conclude,

- Dulcis mater, nec exclude

- A tua grata gratia.

(Hymnus 90. AHMA 15, Dreves 1893, 111)

- Vase full of all gifts,

- available for the bad and the good,

- that you give the benefits of peace,

- enclose me in this vase,

- sweet mother, don’t exclude me

- of your grace.

3. An Iconographic Analysis of Some Pictorial Annunciations with Vase

After this extensive exploration of patristic, theological, and liturgical texts related to the metaphor of the “vase” as a symbol of Mary in her privileged condition as the virginal mother of God, and the sublime holder of virtues and supernatural privileges, it is now time to analyze some artistic images of the Annunciation that include a vase, vessel or container in its scene. Such an iconographic analysis is necessary to try to determine whether there is any relationship between these doctrinal texts and these images.

Among the multiple representations of the Annunciation from the 14th and 15th centuries that we could choose for the iconographic analyses around the symbol of the “vase”, we have chosen fifteen important works painted by artists from Italy, Flanders and Spain, perfectly representative for the topic at hand.

In collaboration with his brother-in-law Lippo Memmi, Simone Martini (1284–1344) elaborates the altarpiece of the Annunciazione con i Santi Ansano e Margherita, 1333 (Figure 1) with a still quite medieval approach. You can see this medieval treatment above all in the central panel, since the figures of the angel Gabriel and Mary are cut out on an abstract background of gold leaf, omitting all scenic elements, except for the throne where the Virgin sits and the vase with the stem of lilies placed on the ground. Kneeling reverently before the enthroned Mary, Gabriel offers her an olive branch with his left hand as a sign of peace, while pointing his right index finger towards heaven to indicate the origin of the message he is announcing to her. This heavenly message guarantees Mary the supernatural privilege of being the mother of God the Son incarnate preserving her virginity, thanks to the power of the Most High who “will cover her with his shadow”: virtus Altissimi obumbrabit tibi (Lk 1, 35. Biblia Sacra 2005, p. 1011). Such is the meaning of the introductory greeting of the angel Ave, gratia plena, Dominus tecum (Lk 1, 27. Biblia Sacra 2005, p. 1011), which appears written in golden letters in the inscription that comes out of the angel’s mouth and reaches up to Mary’s ear. The Virgin shows her unrestricted obedience to the design of the Most High as “slave of the Lord” (ancilla Domini) by humbly bowing her head, placing the right arm on her chest.

Figure 1.

Simone Martini (with Lippo Memmi), L’Annunciazione con i Santi Ansano e Margherita, 1333. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Apart from that eloquent gesture of Mary, it is interesting to highlight in this altarpiece the large vase from which several flowered lily stems emerge. Now, we have shown in other articles that the stem of lilies in the artistic images of the Annunciation is a symbol of the virginal divine motherhood of Mary, in the sense that the stem represents the Virgin, while the flower (the lily) represents her divine Son Jesus. We have justified such an iconographic interpretation based on the ancient and concordant tradition of the Church Fathers and medieval theologians when interpreting three texts from the Old Testament: Isaiah’s prophecy about the flowering of a stalk sprouting from the root of Jesse (Is 11, 1–2) (Salvador-González 2013); the miraculous flowering of Aaron’s dry rod (Salvador-González 2016), and the phrase from the Song of Songs in which the Bridegroom declares to be “the flower of the field and the lily of the valleys” (Song 2, 1) (Salvador-González 2014).

From this interpretive perspective, the close relationship/continuity between the stem (the Virgin) and the vase where it stands allows us to affirm the symbolic identity, doubly reinforced, of Mary as stem and as vase. As if that were not enough, the shape of an inverted uterus that this vase presents in this altarpiece further reinforces this symbolic identification of Mary as a vessel or vase, which so many Fathers, theologians and hymnographers brought to light in perfect agreement for more than a millennium. In addition, the clear protagonist position of this vase, isolated in the center of the altarpiece scene, as an element that connects Gabriel and Mary, reinforces the conjecture that the intellectual author of this Annunciation had in mind the Mariological symbolism of the metaphor of the vase, according to the unanimous patristic-theological exegesis and the countless invocations of medieval liturgical hymns.

That is why it is surprising that the commentators we know of this altarpiece, such as Maria Cristina Gozzoli (1970), Marco Pierini (2002), Enrico Castelnuovo (2003), Pierluigi Leone de Castris (2003) and Pietro Torriti (2006), have not documented the Mariological symbolism of this vase in primary sources.

For the rest, everything that we have explained in this altarpiece by Simone Martini about the continuity/identity between the vase and the stem of lilies as two symbols of the virginal divine maternity of Mary applies to all images of the Annunciation that we will analyze in this article. Therefore, we will not repeat these explanations in each of the tables that we will analyze.

Andrea di Bartolo Cini (c. 1360–1428) performs his Annunciation Diptych, c. 1383, from the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts (Figure 2), with two compositional details similar to Simone Martini’s Annunciation. The first is that di Bartolo also places the angel kneeling before the seated Virgin, although distancing himself from Martini by incorporating Mary in a stylized house in the form of a porch. The second and most important detail—copied from Simone Martini—is to place a large vase with stems of lilies on the floor as a narrative-symbolic link between the Virgin and the angel, who also, as in the case of Martini, carries an olive branch in the left hand. Thus, given the solid patristic-theological tradition and the abundant liturgical hymnody around 1383 (probable date of execution of this painting), it is very likely that the intellectual author of this Budapest diptych was inspired by the multiple exegetical texts referring to the vase as a symbol of Mary.

Figure 2.

Andrea di Bartolo, Diptych of the Annunciation, c. 1383. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

For the rest, Andrea di Bartolo adds the surprising detail of representing the godhead not with the usual figure of God the Father like an adult man, but through the little head of Christ as a child, surrounded by a mandorla of cherubs at the top of the left panel. Such an unusual detail of the little head seeks to illustrate that the Annunciation episode concludes with the human conception/incarnation of God the Son in Mary’s womb at the very moment that she accepts the divine plan announced by Gabriel.

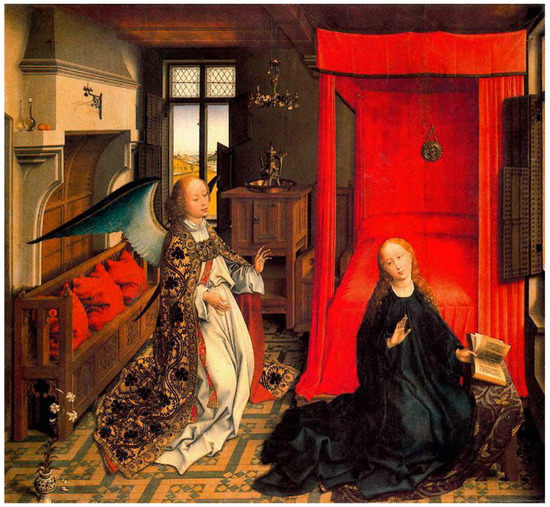

Robert Campin (c. 1376–1444)—helped, according to experts, by his workshop assistants—places The Annunciation of the Mérode Triptych, c. 1427–1432, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Figure 3), inside an elegant bourgeois room, equipped with exquisite furniture and precious domestic utensils. Despite their apparent insignificance, many of these everyday objects—a vase with stems of lilies, a cauldron of water, a towel, candlesticks with or without candles, books—condense several interesting doctrinal meanings, interpreted by some historians with variable accuracy.

Figure 3.

Robert Campin’s workshop, The Annunciation, central panel of the Mérode Triptych, c. 1427–1432. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

On the other hand, it should be noted that the intellectual author of this Annunciation “complemented” the conventional ray of light coming from the (here invisible) Most High with the figure of Christ like a tiny naked child carrying a cross on his shoulder: as already said commenting on the previous painting by Andrea di Bartolo, this figurine of the child Jesus illustrates the thesis of the immediate human conception/incarnation of God the Son when the Virgin declared her absolute obedience to the plan of the Most High at the conclusion of the Annunciation event.

Without stopping now to interpret the other symbols, we are interested in highlighting in this Mérode Annunciation the porcelain vase with its stem of lilies, placed on the table right in the center of the composition, fully visible (with no other overlapping objects), and as a narrative-symbolic link between Gabriel and Mary. It is reasonable to infer that the intellectual author of this Mérode Annunciation has arranged this vase with great visual relevance to evidence its Mariological symbolism according to the concordant interpretations of the Fathers and theologians, and the acclamations of the liturgical hymns.

For these reasons, it seems strange that, apart from Patricia Platgett-Lea (2022), none of the commentators we know of this Mérode Triptych has documented the Mariological symbolism of the splendid vase depicted here. You can see such an omission in Max J. Friedländer (1924, pp. 61–66; 1967, pp. 36–41), David M. Robb (1936, pp. 500–25), Millard Meiss (1945, pp. 178–79), Meyer Schapiro (1945, pp. 182–87), Erwin Panofsky ([1953] 1966, pp. 142–43, 164–67, 304–5), Margaret B. Freeman (1957, pp. 130–39), Théodore Rousseau, Jr. (1957, pp. 117–29), Charles Ilsley Minott (1969, pp. 267–71), Carla Gottlieb (1970, pp. 65–84), Martin Davies (1972, pp. 257–60), Lorne Campbell (1974, pp. 638–45), Barbara G. Lane (1984, pp. 42–45), Shirley Neilsen Blum (1992, pp. 46–47), Albert Châtelet (1996, pp. 93–113), Stephan Kemperdick (1997, pp. 77–104, 181–86), Felix Thürlemann (2002, pp. 65–76), and Kemperdick and Sander (2009, pp. 150–52), to name just a few of the leading experts.

The Sienese painter Sassetta, whose real name was Stefano di Giovanni (c. 1400–1450), depicted The Annunciation, c. 1437–1444, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Figure 4), originally as the central pinnacle of the reverse of the double-sided altarpiece painted between 1437 and 1444 for the Franciscan church of Borgo San Sepolcro in Arezzo. Although it has suffered many deteriorations and repaintings, and has even been cut down in size—which explains why both protagonists, especially the angel, are cut—, we are interested in highlighting the vase with the lily stems: fully exempt and prominently placed between Gabriel and Mary it conveys all Mariological meanings already explained.

Figure 4.

Sassetta, The Annunciation, c. 1437–1444. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

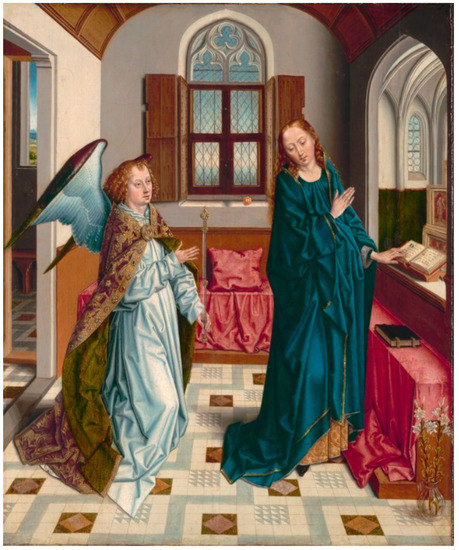

Rogier van der Weyden (c. 1399/1400–1464) stages The Annunciation, c. 1434–35, central panel of the Triptyc of the Annunciation, in the Musée du Louvre in Paris (Figure 5), in a luxurious living room plenty of refined furniture and utensils, open to the outside through the large windows at the back and on the right side. In this elegant setting, the angel Gabriel, clad in a precious embroidered cope, begins to kneel before the seated Virgin, who, surprised by the appearance of the unexpected visitor, interrupts reading the book she is holding open with her left hand, while slightly turning her head towards the heavenly messenger.

Figure 5.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Annunciation, c. 1434–1435, central panel of the Triptyc of the Annunciation, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

In that living room, van der Weyden has surprisingly placed a neat marriage bed to illustrate its profound dogmatic meanings that we cannot detail here, since we have already explained them extensively in other works (Salvador-González 2019, 2020a, 2021d). The angel has entered this living room by the closed door—barely visible on the left side, suggested by its jamb—without opening it, a closed door whose Mariological and Christological symbolisms we have elucidated in another study (Salvador-González 2020c).

However, more than these two connoted symbols and other no less significant elements present in this painting, we are now interested in underscoring the three vessels that appear in it: the vase with the stem of lilies placed on the ground in the foreground, the crystal vessel with water placed on the ledge between the fireplace and the door, and the pitcher of water from the ewer located on the sideboard attached to the back wall. In this regard, it does not seem necessary to repeat now that these three vessels, each in its own way, symbolize the virginal divine motherhood of Mary and the fullness and sublimity of her virtues and supernatural privileges, as many Fathers, medieval theologians, and liturgical hymnographers unanimously manifested for more than a millennium.

That is why it is surprising that the commentators we know of this Annunciation by van der Weyden have not justified, based on primary sources, the Mariological symbolism inherent in these three vessels. Erwin Panofsky ([1953] 1966, vol. I, pp. 250–56), Martin Davies (1972), Odile Delenda (1987, pp. 33–36), Albert Châtelet (1999a, p. 43; 1999b, pp. 97–99), and Dirk De Vos (1999, pp. 98, 195–99), among others, incur in that omission.

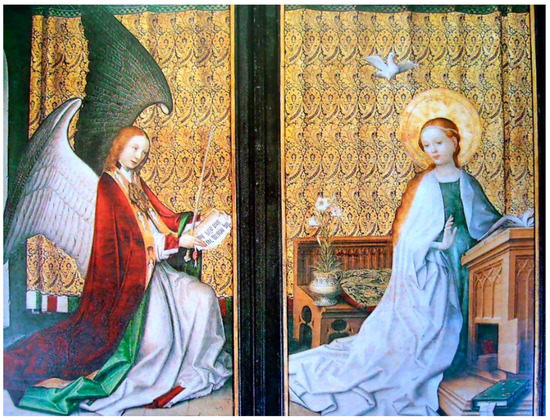

Stefan Lochner (c. 1400/10–1451), in representing The Annunciation, in two panels of the closed Magi Altarpiece, 1440, from the Cologne cathedral (Figure 6), opts for a relatively conventional composition: the angel beginning to kneel in the left sector, carrying a herald’s staff and showing a wide phylactery with the message of the Most High; the Virgin kneeling to the right before a kneeler on which she has her prayer book open. Nevertheless, the painter surprises us with some other symbolic details, such as the closed book placed on the platform in the foreground in the right angle, or the open piece of furniture, on which we cannot stop now. We just intend to highpoint once again the voluminous vase from which a lily stem emerges in the center of the scene, as a narrative-compositive link between the heavenly messenger and the Annunziata.

Figure 6.

Stefan Lochner, The Annunciation, two panels of the closed Magi Altarpiece, Cologne cathedral, 1440.

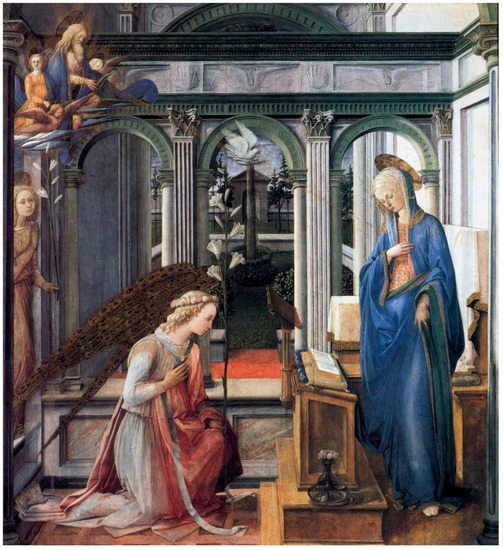

Fra Filippo Lippi (1406–1489) structures with great originality The Martelli Annunciation, c. 1440, from the Martelli Chapel in the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence (Figure 7). From the outset, he stages the episode in an ostentatious and complex Renaissance palace, with a long perspective. In addition, he surprisingly adds two other angels as companions of the archangel Gabriel, who fill the left half of the composition, while in the right half he places Gabriel and Mary.

Figure 7.

Fra Filippo Lippi, The Martelli Annunciation, c. 1440. Cappella Martelli, Basilica di San Lorenzo, Florence.

Without dwelling now on interpreting the doctrinal meanings of the house of Mary shaped as a palace, which we have explained in other articles (Salvador-González 2021a, 2021c), nor those of the closed garden (hortus conclusus) that one can see in the intermediate planes, we are interested in emphasizing a very significant detail: after placing the stem of lilies in the hand of the genuflected Gabriel, Lippi includes in the very foreground—as a linking element between the heavenly messenger and the Virgin—a transparent glass vase, half full of clear water.

It seems completely evident that the cult Carmelite monk who was Fra Filippo Lippi has introduced here in a leading role that brilliant glass vase to symbolically signify Mary as the virtuous mother of God the Son, drawing inspiration from the numerous patristic-theological testimonies and medieval hymns on the symbol of the “vase”, which Lippi seems to know firsthand, given his careful ecclesiastical training and his practical life as a friar.

Therefore, it is surprising that the commentators we know on this Martelli Annunciation, such as Giuseppe Marchini (1979), Jeffrey Ruda (1993, pp. 163–65, 428), Megan Holmes (1999), and Glossi and Pinci (2011), have avoided to explain with convincing documentary arguments the Mariological symbolism of this exceptional glass vase.

In the L’Annunciazione delle Murate, c. 1443 (Figure 8)—originally painted for the Suore Murate convent in Florence, and today at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich—Fra Filippo Lippi places the episode inside a luxurious Renaissance palace, with elegant marble arches, pilasters, and entablatures.

Figure 8.

Fra Filippo Lippi, The Murate Annunciation (L’Annunciazione delle Murate), 1443. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

In that sumptuous palace, open onto a walled garden (hortus conclusus), the archangel Gabriel, bearing a large stem of lily in his left hand, kneels reverently before his heavenly Sovereign. Behind Gabriel, a second angel appears through the door with another stem of lilies. The Virgin remains standing, modestly lowering her head and her eyes, while placing the right hand on her chest in an attitude of humble obedience in accepting the divine plan announced by Gabriel.

In the upper left corner of the painting, the Most High, surrounded by angels, opens his hands to send towards the Virgin the fertilizing beam of light—symbol of God the Son, as we have shown in other articles (Salvador-González 2021a, 2021c)—, in the middle of whose wake appears the Holy Spirit flying in the form of a white dove.

Apart from these foreseeable elements at the time in these representations of the Annunciation, it is worth underlining in this work the bulky glass vase located in the foreground, which contains roses and other flowers. Undoubtedly, the erudite Fra Filippo Lippi wanted to illustrate through this crystalline vase with flowers the virginal divine motherhood of Mary and the fullness of her virtues and supernatural attributes, drawing inspiration from the centuries-old exegetical tradition of Fathers, theologians, and hymnographers, which he must have known perfectly, due to his condition as well-trained Carmelite friar.

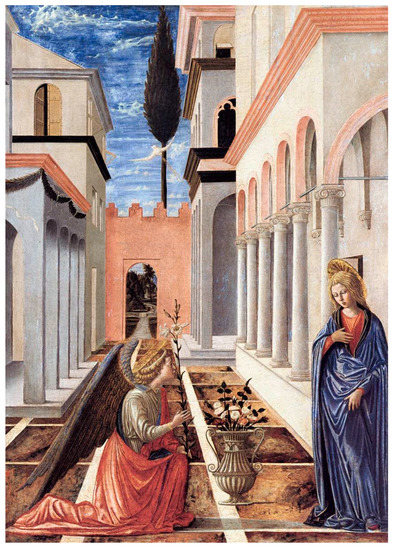

Fra Carnevale, stage name of Bartolomeo di Giovanni Corradini (c. 1429/25–1484), places The Annunciation, c. 1448, from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC (Figure 9) in the narrow arcaded courtyard of a monumental palace, which reveals a distant landscape in the background through the open door in the wall. In the foreground of that courtyard, the angel, who carries in his left hand a long stem of lilies, kneels reverently before his heavenly Lady, while she, standing, places her right hand on her chest, as if wondering if she is the very recipient of the design of the Most High. Once again, it is important to highlight in this painting the huge vase full of roses and other flowers, as a link between both protagonists. It seems evident that Fra Carnevale placed this great vase here as an eloquent symbol of Mary as the virginal mother of God and the sublime model of all virtues, in perfect harmony with the centuries-old exegetical tradition of Fathers, theologians and hymnographers, which he undoubtedly knew for his status as a learned Dominican friar.

Figure 9.

Fra Carnevale, The Annunciation, c. 1448. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Rogier van der Weyden stages The Annunciation on the left wing of the Altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi (St. Columba Altarpiece), painted around 1450–1456 for the high altar of the parish church of St. Columba in Cologne, and today in the Alte Pinakothek from Munich (Figure 10), in a comfortable bourgeois room in Flanders. The painter places the angel standing here blessing Mary, who prays on her knees before a book, while extolling her with his initial greeting ave gratia plena dominus tecum, made visible in an epigraphic inscription that comes out of his mouth towards the ear of the Virgin.

Figure 10.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Annunciation, left wing of The St. Columba Altarpiece, c. 1455, Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

In addition, van der Weyden introduces several symbolic elements in this painting, such as the large, canopied marriage bed, the closed door through which the archangel has entered without opening it, and the fertilizing ray of light coming from the Most High that passes through the crystals of the window without breaking or staining them. We have explained the doctrinal symbolism of this ray of light in another article (Salvador-González 2020b). However, without reiterating here the doctrinal meanings of these and various other symbolic details of this painting, which we have already analyzed in other works, we are now interested in highlighting the metal vase that contains the lily stem in the foreground between Gabriel and Mary. In such leading circumstances, it is undeniable that this shiny vase, with its complementary lily stem, constitutes a clear symbol of Mary as the virginal mother of God, as the incomparable possessor of all virtues, and the holder of some exclusive divine privileges: this is confirmed by the already explained patristic and theological texts, and the hymnic acclamations that designate the Virgin as “vase”, vessel, ark, urn, or other analogous expressions alluding to some valuable container.

Therefore, it is unfortunate that the commentators we know of this important Annunciation by van der Weyden do not justify the Mariological symbolism of that vase based on primary sources. You can find such an omission in Max Julius Friedländer (1924, 1967), Erwin Panofsky ([1953] 1966, vol. I, pp. 203–4, 249–51, 284–88), Martin Davies (1973, pp. 268–70), Odile Delenda (1987, p. 54), Paul Philippot (1994, p. 40), Albert Châtelet (1999a, pp. 112–17; 1999b, pp. 97–99, 195–200), Dhanens and Dijkstra (1999, pp. 35–36), Dirk De Vos (1999, pp. 276–84; 2002, p. 83), Kemperdick and Sander (2009, pp. 96, 100–1), and Campbell and van der Stock (2009, p. 351).

Hans Memling (c. 1433/40–1494)—or, according to other experts, a presumed disciple of Rogier van der Weyden, whose design the disciple would have used to execute this painting—organizes the scene of The Clugny Annunciation, c. 1465–1470, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Figure 11) in an elegant bourgeois residence, equipped with precious furniture, through whose window a large walled garden can be seen.

Figure 11.

Hans Memling or Rogier van der Weyden’s workshop, The Clugny Annunciation, c. 1465–1470. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The painter places the two protagonists of the episode in this splendid setting. Dressed in luxurious clerical clothing embroidered in gold, and carrying a herald’s staff in his left hand, the Archangel Gabriel announces the divine plan to the Virgin. Kneeling on her prie-dieu, Mary extends her right hand over the book of hours, as in a gesture of swearing before the Bible, to show her compliance with the will of the Most High. More than the eloquent elements of the bed and the closed door (porta clausa), whose dogmatic meanings we have already explained in other studies, it is convenient to highlight again the shiny metallic vase that, standing out in the foreground, holds the stem of lilies upright.

It seems indisputable that the intellectual author of this painting includes this vase in such a prominent position as a symbol of Mary in her condition as virginal mother of God, and as the exalted holder of sublime virtues and supernatural privileges. For this reason, it is shocking that none of the commentators that we know of this Clugny Annunciation have documented the Mariological meanings of this vase. In this surprising silence fall, among others, Max Julius Friedländer (1967), Martin Davies (1973, pp. 271–72), Odile Delenda (1987, pp. 54–57), Dirk de Vos (1994), Dhanens and Dijkstra (1999, p. 47), Albert Châtelet (1999a, p. 124), and Alfred Michiels (2007).

Dirk Bouts (1410–1475) poses The Annunciation, c. 1475–1487, from the Muzeum Czartoryskich in Krakowie (Poland) (Figure 12), with a certain originality regarding conventional models. He places the Virgin sitting on the floor, instead of kneeling on a prie-dieu or sitting on a seat, which are the most common positions for her in representations of the Annunciation. In addition, he reverses the usual position of both protagonists, now placing the Virgin on the left of the scene, and on the right the angel, who carries the herald’s staff in his left hand. Dirk Bouts repeats here the attitude of Mary placing her right hand on the prayer book, as if in an attitude of confirming the will to tell the truth in an act of official oath through the gesture of pronouncing the oath after placing the right hand on the Gospel.

Figure 12.

Dirk Bouts, The Annunciation, c. 1475–1487. The Muzeum Czartoryskich, Krakowie.

However, now ignoring this and other significant details in this painting, we are interested in highlighting the vase carrying a large stem of lilies that, located at the back of the scene on a piece of furniture between two cushions, constitutes the visual center and axis around which the figures of Gabriel and Mary counterbalance. By placing this vase in such a relevant situation, it seems logical to think that the author of this painting wanted to emphasize its strong symbolic charge, in line with the already explained approaches of the Fathers, theologians and medieval liturgical hymnographers.

Aelbrecht (or Albert) Bouts (c. 1452–1549), son of the painter Dirk Bouts, stages The Annunciation, c. 1480, from the Cleveland Museum of Art (Figure 13) within an elegant Gothic chapel or small private temple, as revealed by its tracery windows and ribbed vault. In this regard, the artist represented here the humble house of Mary in Nazareth shaped like a splendid temple to illustrate certain Mariological and Christological symbolisms that we cannot explain in this article, since we have already explained them in other works (Salvador-González 2017, 2020d, 2020e, 2020f, 2021b).

Figure 13.

Aelbrecht Bouts, The Annunciation, c. 1480. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland.

In this ambiance of ecclesial intimacy, the angel Gabriel, covered with a luxurious embroidered cope, and carrying the herald’s sceptre, points his right hand at the Virgin indicating that she has been designated by the Most High to become the virginal mother of his divine Son. Mary manifests her unrestricted obedience to the will of God the Father by holding the book of hours in her left hand and raising her right hand over it, as if to take an oath on the Bible.

Now, among the various objects of this refined furniture, it is convenient to emphasize the transparent glass vase that in the foreground in the lower right corner holds a pair of lily stems. In this regard, the hypothesis sounds reasonable that the author of this Annunciation has considered the underlying Mariological meanings under this gleaming glass vase, according to the already explained interpretations of the Fathers and theologians, and the acclamations of the liturgical hymns on the Mariological metaphor of “vase” or vessel.

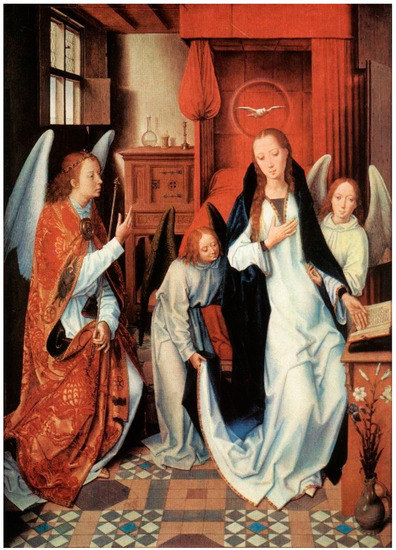

Hans Memling brings in The Annunciation with angelic attendants, 1482, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Figure 14), a quite original approach. He continues to introduce here the usual conventions of the 15th century Flemish painters. For this reason, he stages the Marian episode in a luxurious bourgeois residence with precious furniture and fine utensils, among which a clean marriage bed stands out in the middle of the living room, and dresses the Archangel Gabriel with a sumptuous cope, making him also wear the herald’s staff in his left hand.

Figure 14.

Hans Memling, The Annunciation with angelic attendants, 1482. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Aside from these predictable elements in the 15th century Flemish iconography, Memling presents two major novelties in the treatment of the Virgin Mary: first, because, while standing, she begins to bend her knees and fall backwards, as if she were fainting; second, because at her side are two angels, companions of Gabriel, one of whom holds her by the arm to prevent her from collapsing, while the other grabs the lower end of her long tunic, as in the gesture of a page or as a bridesmaid lifting the long train of a queen or a bride at the marriage ceremony. In addition, Memling represents the Virgin with a swollen belly, as a sign of advanced pregnancy (which is in accordance with her fainting), as if to illustrate that at the concluding moment of the Annunciation—when Mary declared her unrestricted obedience to the plan of the Most High—the immediate human conception/incarnation of God the Son occurs in the virginal womb of Mary.

However, we will not dwell now on the undoubted symbolism that the marriage bed, the closed door on the left edge of the painting, and the fainting and pregnancy of the Virgin have in reference to the virginal divine motherhood of Mary.

Instead, we are interested in stressing the polyvalent Mariological symbolisms offered by the two vessels that appear in this painting: the ceramic vase with the stem of lilies placed on the floor in the foreground, and the glass vase or bottle with water placed on the sideboard attached to the back wall. Memling thus adopts a duplication of vessels like the one used by Rogier van der Weyden in his already analyzed Louvre Annunciation, with the difference that the latter put a glass vessel and a metallic jug in the Paris one, while Memling puts a bottle or glass vessel in that of the Metropolitan. In any case, with these two very different vases—a ceramic vessel with the stem of a lily, and a glass vessel with water—Memling illustrates the already explained Mariological meanings of the “vase” as a simultaneous symbol of the virginal divine motherhood of Mary, and the fullness of her sublime virtues and exclusive privileges, as manifested in full agreement by innumerable Fathers, theologians, and liturgical hymnographers for more than a millennium.