Abstract

This paper examines Wu Bin’s (c. 1543–c. 1626) Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock (1610) from the perspective of Buddhist epistemological notions in seventeenth-century China. In studying a series of gazes focusing on a single object—a stone with a very complex surface—my discussion posits an act of excessive seeing as a process of making worlds. I take a theoretical cue from contemporaneous intellectual discourses, especially those that flourished with the revival of Yogācāra Buddhism in late Ming China. This paper will show how an art object comes into being in perceivable worlds interconnected by the individual’s sensory experiences. My study aims to inquire into the role of illusion as sensory experiences, phenomenological processes, and even notions of soteriological efficacy beyond formal artistic devices. To that end, this paper is the first attempt to situate Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock alongside Buddhist thoughts and artmaking.

1. Introduction

In 1610, the professional painter Wu Bin (c. 1543–c. 1626) completed a painting of a stone after spending a month examining it. The commission for the painting was from the prominent official, calligrapher, and collector Mi Wanzhong (1570–1628). Currently known as Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, this scroll contains ten near-life-size renditions of one particular stone that Mi acquired sometime between 1608 and 1610, meticulously captured from ten different angles (Figure 1).1 The resultant painting attests to Wu Bin’s painstaking painterly method by revealing schematic configurative lines and masterfully controlled ink tonalities. Every stroke claims truth in reconstructing the object, and yet, at the same time, delves ever further away from naïve realism into the realm of fantasy; while each step of the process burgeons from an association with the rock, the total impression becomes one of fiction rather than faithful representation. Such paradoxical status of the depicted stone is incorporated with a real-time process—observation.

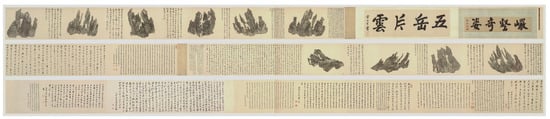

Figure 1.

Wu Bin, Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, 1610. Handscroll, ink on paper, (painting) 55.5 × 1150.0 cm; (colophons) 55.5 × 1387.5 cm. Photo: Courtesy of Poly Art Museum, Beijing (Baoli yishu yanjiuyuan 2020).

Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, created during the late years of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), marks a significant moment in the history of Chinese painting by presenting a moment in which the painterly quest for unobstructed vision becomes an object of critical uncertainty, and hence inquiry, in and of material reality itself. Existing studies on Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, by and large, are built upon notions of the artist’s romantic authorial subjectivity, fetishized eccentricity, and, most of all, the Eurocentric idea of realism.2 What has been lost in the scholarly discussion is attention to objects related to sensory experience and perception, both concerning the pictorial presentation and conceptual construction.3

This paper, therefore, proposes that Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock may be better understood with reference to questions about seventeenth-century notions of reality and illusion, informed by the tension between perceiving selves and perceived objects. In my discussion, illusion will not be limited to its narrow association with verisimilitude, spatial illusionism, or naturalistic mimesis within the European artistic tradition. My exploration of Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock shall inquire into various dimensions of illusion as sensory experiences, phenomenological processes, and even notions of soteriological efficacy in addition to formal artistic devices. In studying a series of gazes focusing on a single object—a stone with a very complex surface—this paper posits an act of seeing as a process of making worlds.4 I take a methodological cue from contemporaneous intellectual discourses, especially those of Buddhist epistemology and metaphysics that flourished with the revival of Yogācāra Buddhism in the late Ming period. This study will show how an art object comes into being in perceivable worlds interconnected by the individual’s experiences.5

1.1. Collective Views

Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock consists of ten pictures of a rock, each paired with Mi Wanzhong’s inscription, and colophons written by Mi himself and eleven others: Ming dynasty elites Dong Qichang (1555–1636), Li Weizhen (1547–1626), Ye Xianggao (1559–1627), Chen Jiru (1558–1639), Zou Diguang (1550–1626), Zhang Shiyi (1575–1633), Gao Chu (jinshi in 1598), Xing Tong (1551–1612), and Huang Ruheng (1558–1626); Manchu officials Saying’a (1779–1857) and Qiying (1787–1858) in the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). With these colophons, the painting comprises a 27-m-long handscroll. Next to each “view” in the scroll, Mi Wanzhong begins his inscriptions by clarifying the direction of the angle from which the stone is viewed: (1) a frontal view from the front (2) a frontal view from the rear (3) a frontal view from the left (4) a frontal view from the right (5) a view from the front left (6) a view from the front right (7) a view from the rear right (8) a view from the rear left (9) a view of the bottom from the front (10) a view of the bottom from the rear.

In the scroll, the rock is meticulously inspected like a subject of scientific study, removed from its natural environment. Each inscription begins with the point of perspective and then inventories the measurement of individual features. For example, the first view begins:

This is the straight frontal view from the front of the rock. The height of the middle peak is one chi seven cun, about two cun lower than the peak behind it. Seven cun from the top, there again forms a small peak; there are over ten small craggy peaks emerging above and below it. …Eight cun below the left flank of the mountain, another peak rises to six cun eight fen high, whose end is flat at its end and branches off into three.6

These inscriptions make each view penetrable by fixing the direction of the gaze. Even within the given view, Mi Wanzhong examines and describes smaller peaks from different angles as forming myriad other views therein. The text and image of each view also carefully delineate how these smaller parts engage with each other and condition their visibility. Minute details simulated by the painting lure the eyes close to the painting surface, a stage of a particular stone. In verbalizing the spectacle, Mi Wanzhong employs stage left and right to define the viewpoint, a common mode of writing for religious images in East Asia, thereby elevating the status of the stone to a subject of worship. The depicted stone stands almost as an icon and as a mirror, reflecting our gazes (Marion 1995, pp. 10–12).

The repetitive act of measuring is one of the unprecedented aspects of Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock. Mi Wanzhong’s thoroughgoing documentation allows us to estimate the rock’s height as one chi nine cun five fen, which is about 63.7 centimeters. The one depicted in the painting is smaller, measuring approximately 51 centimeters high. Wu Bin precisely scaled down the size so that the eyes under the guidance of painstaking measurement can do the computation to complete the stone’s actual overall form. This process is somewhat analogous to current-day photogrammetry.7 On the other hand, Mi Wanzhong shifts his writing mode from a descriptive one to an expressive one. Once his statement on Wu Bin’s painting process is concluded, Mi Wanzhong suddenly starts to negate the corporeality of the stone itself. Then, almost like the picture of Dorian Gray in the eponymous novel by Oscar Wilde, Mi Wanzhong says that the painting seems to be transformed into the rock. Throughout Mi’s close visual perception of his Lingbi rock and the painting, the stone itself ceased to exist as a material entity, while the painting took over the rock’s materiality. After presenting grandiloquent descriptions of the rock, suddenly, Mi clears his mind and concludes the colophon by measuring the stone again and counting the peaks as if the precise measurement was the only way to endorse the rock’s presence.

In his colophon, Mi Wanzhong recounts how Wu Bin endeavored to transfer his fixed gaze onto paper. After examining the rock for a month, Wu proceeded to complete the ten views as follows:

[Wu] examined it so thoroughly from morning to night that his consciousness merged with it. Then, taking up a piece of old paper, he first painted it from the front and back, but he was not done with his painting. He continued portraying the left and right sides, but the painting was still not finished yet. He went around the stone and portrayed the front, back, left, and right sides diagonally. With the bottom from the front and from the back, [Wu completed] ten views in all.8

Striking in Mi Wanzhong’s testimony is that Wu Bin literally “exhausted his skill” in completing the scroll with the tenth aspect of the stone. The unique texture with white veins and twisting morphology in the painting can be compared to the entry on the Lingbi rock, a limestone from the Lingbi township in Anhui Province, in the reputable compendium Stone Catalogue of Cloudy Forest by the Song dynasty polymath Du Wan (active ca. 1130) (Du Wan, shang:1a–2a).9

As Mi Wanzhong’s words suggest, the number ten was not randomly chosen. Yet ten views far exceed what Du Wan considered the ideal number of views for the finest Lingbi rock. In most cases, Du writes, they have one or two displayable sides (mian, literally meaning face), sometimes three, but one or two out of a hundred pieces of them have four.10 Even the tall, awe-inspiring ones owned by the famous Mr. Zhang of Lingbi had two or three views, but one of those was often covered with condensed mud and had to face the wall when displayed. Mi Wanzhong’s Lingbi with ten clear views, despite its smaller size, must have been beyond Du Wan’s imagination. Notwithstanding Mi Wanzhong’s effort to underline the significance of having ten views, recent studies on Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock suggest that the painting initially contained eight views and only later were two more views added (Zhu 2017, p. 106). Such understanding comes from a misreading of an account by Mi Wanzhong’s acquaintance Zhang Nai (1572–1630). In an account composed to praise his friend with the surname Fan and courtesy name Darenzi, Zhang Nai recalls a gathering at Mi Wanzhong’s residence with several other people (Zhang Nai, 11:47b–48b). Zhang describes a painting of a “spiritual rock (lingshi)”, which consists of eight views. As the guest named Yang He (?–1635) in the gathering said it should have ten views, the poet Long Ying (1560–1622) inscribed “not-not real rock (feifei shi)” as if “he was going through ten views with a single brush stroke.”11

Zhang Nai never identified who painted the “spiritual rock”, which could be a generic nomenclature of odd-looking decorative rocks and must be distinguished from the specific type of rock, Lingbi. Nor did he indicate that Long Ying added two more pictures in addition to his inscription. When only the names of the poet and calligrapher are given, what was added to the scroll was more likely to be a piece of calligraphy that corresponded to the existing eight pictures. Furthermore, it should be noted that Wu Bin created multiple paintings of rock in Mi Wanzhong’s collection.12 The painting of a spiritual rock mentioned by Zhang Nai could be one of those paintings. Above all, Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock itself hardly supports the claim that the painting originally had eight views. None of the colophons mentions such a possibility, while the paper and inkwork are consistent throughout the ten views. Moreover, the painting process upon which Mi elaborates in his colophon implies that the scroll contained ten images at the time of its production. The location of Wu Bin’s signature in the last view of the stone (Figure 2) also suggests that he marked the completion of his painting not with the eighth view, but with the tenth, engraving his subjectivity at that point. Looking at the stone, Mi Wanzhong writes, should stop with the tenth view.

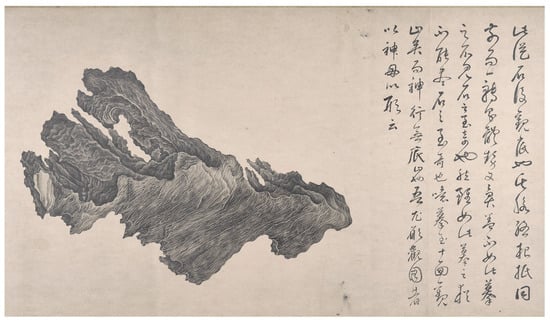

Figure 2.

Wu Bin, Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock (detail), the tenth view with the painter’s signature. Photo: Courtesy of Poly Art Museum, Beijing (Baoli yishu yanjiuyuan 2020).

Nevertheless, Zhang Nai’s writing should not be disregarded as it affords a springboard to understanding the seventeenth-century notion of seeing. In the latter half of his account, Zhang states that the rock he perceives is a view from his consciousness. What he sees is not the truth, he writes, just like a lamp that causes constant changes of light and shadow (Zhang Nai, 11:48a–b). Then he laments that one cannot see every possible view of Mount Lu—a famous literary trope from Su Shi’s (1037–1101) celebrated quatrain Written on the Xilin Temple Wall (Grant 1994, p. 1). Both the impossibility of seeing the true face of Mount Lu described in the poem and Zhang Nai’s phrase about a view from his consciousness allude to the same source. It is Buddhist epistemology expounded in the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, which Su Shi and later writers enjoyed citing (Grant 1994, p. 29), and which, by the late sixteenth century, had become the most widely read Buddhist text (Araki 1984, pp. 245–74). Along with its exceptional quality of literary composition, the meditative methods of taming sensory organs and the soteriological role of illusion introduced in the sutra fascinated late Ming intellectuals and artists (Lo 2016, pp. 107–51; Ryor 2019, pp. 244–66).

The well-educated scholar, Zhang Nai, would not miss this intellectual trend, and it is from the Śūraṅgama Sūtra that he borrowed the metaphor of the lamp. In the pertinent passage, the Buddha admonishes Ānanda for relying on external factors for seeing because immediate visual perception is not true seeing but an ever-transient lamplight (SLYJ, T 945.19:109b). A lamp, like the sun and the moon, refers to a source of light that conditions the visibility of perceivable objects. Ānanda defends himself by claiming that ordinary people see various objects by relying on the light from the sun, the moon, and lamps, and this is what they mean by “seeing” because without these sources of light, they would not be able to see (SLYJ, T 945.19:113a). Then, the Buddha begins his lecture on why he should employ the power of his vision to the fullest extent to see everything in the universe clearly without depending on a lamp and distinguish them from himself (SLYJ, T 945.19:111b).

The increasing awareness of such Buddhist epistemology flourished together with the mid-sixteenth-century revival of Yogācāra Buddhism, a Buddhist philosophy tradition that values the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness (Brewster 2018, pp. 117–70; Chu 2010, pp. 5–26; Struve 2019, pp. 99–103). Although the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, with its apocryphal origin, is not traditionally associated with Yogācāra Buddhism, late Ming commentators utilized Yogācāra doctrines to annotate the sutra, as well as other Mahāyāna texts. Accordingly, the storehouse consciousness (ālāyavijñāna), the critical element in Yogācārin metaphysics, and the Mahāyāna Buddhist idea of the embryo of Buddhahood (tathāgatagarbha), a primary exegesis in the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, arose as underpinning concepts in a wide range of Buddhist writings and practices in the late sixteenth century. Notably, the Four Eminent Monks of the Wanli period (1572–1620), Hanshan Deqing (1546–1623), Zibo Zhenke (1543–1603), Yunqi Zhuhong (1535–1615), and Ouyi Zhixu (1599–1655) had a mutual fascination with doctrines across different Buddhist schools, Yogācāra, and tathāgatagarbha, despite their individual distinctness and sectarian foundations in Chan or Pure Land (Chu 2010, p. 16).13

The pan-sectarian syncretism points to another important philosophical shift. The late Ming period marked a change in intellectual currents involving the discourses led by Yangming School of Mind scholars who emphasized the Mind (xin) in explaining the world. By the early seventeenth century, epistemological interest in the relation between seeing and knowing came to include questions about the metaphysical implications of investigating Things (wu). In reevaluating Things in the lower level of the hierarchy among beings, they noted that perceiving Things perceived as images can be manifestations of their Mind (Bian 2020, p. 78). Under such intellectual currents, some comparable concepts in late Ming Buddhism and Yangming Confucianism catalyzed inter-religious dynamics. As William Chu points out, the newly revived Yogācāra tradition paralleled the concept of consciousness with the Mind in tathāgatagarbha thought, which could be posited as the Mind in the Yangming Confucianist context (Chu 2010, pp. 6–8, 15–16). The emphasis on the physical world as a projection of the Mind was one on which Yangming Confucianists and syncretic-minded Buddhists could agree.

Obsessions with appreciating rocks came at the end of the sixteenth century when the ability to observe and characterize material objects began to serve as a precondition for understanding the physical world.14 The urge for in-depth visual experiences followed amateur interest in horticulture, medicine, mineralogy, and herbology. Empirical impulse had long been in Chinese intellectual spheres, but the late Ming thinkers pushed it further to question the nature of their reality consisting of a perceiving self and perceived things, either in the Confucian or Buddhist senses, or both. The Confucian scholar Luo Wenying (active early 17th century) wrote in a preface to a herbological text that when one sees things as Things, images, vegetal roots, or dim appearances, all these are nothing but the manifestations of his own Nature (xing) (Bian 2020, p. 75). This understanding of human perception resonates with the Buddhist view of the material world that every perceived object is the manifestation of the Mind, as mentioned earlier. The soteriological undertone, however, marks the difference between the two thoughts. In the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, the Buddha says one needs to carefully observe everything as much as possible to realize that all are objects of one’s perception (SLYJ, T 945.19:111b). Therein lies a challenge in which sentient beings cannot easily distinguish illusoriness because perceivable phenomena and reality constantly redefine one another. Hanshan Deqing, the eminent commentator of the Śūraṅgama Sūtra in the Yogācārin context, annotates this phrase that objects one sees here are just dust (chen) floating in the sensory fields (Hanshan Deqing, X 279.12:547c). They are visible because the storehouse consciousness, which is accumulated impressions and experiences from sense data, illuminates these clouds of dust. Realizing that what is visible is just motes of dust requires a meditative practice that may lead one to the ultimate reality beyond sensory perception.

1.2. Seeing as Worldmaking

As a devoted Buddhist praised by Hanshan Deqing (Hanshan Deqing, X 1456.73:736c), Wu Bin was also familiar with the Śūraṅgama Sūtra and the contemporary ethos on sense-perception shaped by Yogācārin phenomenology.15 Around 1600, Wu Bin created an album titled Twenty-five Dharma Gateways of Perfect Wisdom from the Śūraṅgama Sūtra. The album consists of twenty-five leaves, each depicting arhats, bodhisattvas, and a buddha, and two inscriptions written by Chen Jiru in 1620 and Dong Qichang in 1621.16 The twenty-five dharma gateways refer to meditative methods that concentrate on six sense objects, six sense organs, six consciousnesses, and seven elements to reach enlightenment (SLYJ, T 945.19:130a–131b). Among them, the gateway that resonates with what Wu Bin did with the Lingbi rock is Upaniṣad’s contemplation upon visible objects (sechen, literally meaning colorful dust) (Figure 3). This method alludes to a fifth-century early chan practice of visualizing a decaying body, famously known as “white bone contemplation” (Greene 2021, pp. 84–87).17 When presenting his method to reach enlightenment, Upaniṣad explains that he has gazed at bones until they turn to dust, disperse into space, and vanish. Visible objects as he had perceived them no longer exist, but “their wondrousness was revealed to him everywhere (SLYJ, T 945.19:125c).” Wu Bin’s visualization of Upaniṣad captures this meditative process that leads to enlightenment. In the painting, Upaniṣad calmly gazes down at a small skeleton expressing respect to him. The relationship between the see-er and the seen in Wu Bin’s painting is markedly different from one in another depiction of Upaniṣad made by Fu Kun (active 17th century) in 1627 (Lo 2016, pp. 140–42). In Fu Kun’s version, Upaniṣad gazes at scattered bones. The length of time Upaniṣad spent observing them is suggested by the grass growing through the skeleton’s eye sockets. While Fu Kun underscores the process of decaying, Wu Bin presents the “wondrousness” revealed upon Upaniṣad’s enlightenment—a living skeleton wearing a gauzy robe, whose initial form had been disappeared but remained visible to him.

Figure 3.

Wu Bin, “Upaniṣad” from Twenty-five Dharma Gateways of Perfect Wisdom, ca. 1600. Album leaf, ink and color on silk, 62.3 × 35.3 cm. Photo: Courtesy of National Palace Museum, Taipei.

As Mi Wanzhong indicated in his colophon to Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, how Wu Bin chose to visually experience the stone was to “examine (guan)”. In the same piece of his writing, Mi also acknowledges that the true aspect of his rock can be grasped only by the Mind, a sentiment reminiscent of Su Shi’s reflections on Mount Lu. But Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock does not stop at acknowledging the limit of bodily perception. Whereas the eleventh-century poet internalized his inability of true seeing by gazing inward instead of projecting outward, Wu Bin and Mi Wanzhong challenge the limit by pushing the boundaries at full force. The scroll invites the onlookers to leap into the sensorium to materialize their optical experiences. When one reaches close to the level of seeing that which “transcends all external conditioning forces”, there will be the truth (Grant 1994, p. 30). The process of illusion built from an excessive seeing in Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock may demonstrate how one’s fixated gaze onto a single visible object works as a gateway. Consequently, the scroll exhausts all possible operations that involve the optic faculty—observing, painting, measuring, describing, and, to that end, presenting itself as a perpetuating enumeration of illusion and reality, or, in other words, visible things and truth beyond visibility. To that end, even after the physical rock disintegrates, its “wondrousness” would remain perceivable to enlightened minds.

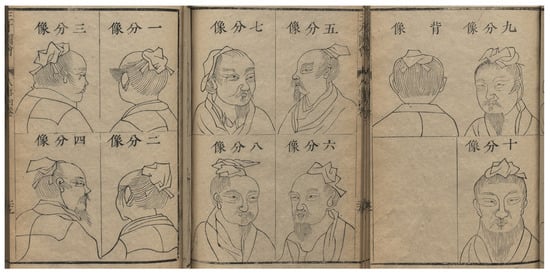

The exploratory role of registering one’s optic faculty onto the stone and the painting scroll suggests that the implication of the number ten to illustrate the stone is not just about excessiveness. Visually, a diagram of a head from eleven different angles in the Pictorial Compendium of the Three Powers published in 1609 might have been a source of inspiration (Wang Qi, renshi 4:29a–30a). The diagram proceeds as “one-tenth view”, “two-tenth view”, and so forth and ends with the “rear view” following the “ten-tenth view (front view)”, a total of eleven views (Figure 4). Nevertheless, each picture in the table was to model a single piece of portraiture, not to unpack all eleven of them onto a handscroll. The Buddhist numerical implication about the number ten may explain why Wu Bin chose to present ten views. The metaphor of the number ten harks back to the Mahāyāna idea of the “ten suchlike aspects of reality (ten tathāta; shi rushi)” elaborated in the Lotus Sūtra (Miaofa lianhuajing, T 262.9:5c), which inspired the Tiantai concept of ten realms of reality (ten dharmadhātu; shi fajie) (Mohe zhiguan, T 1911.46:5b).18 The cosmological overtone of the number ten is incorporated with the epistemological context in the Śūraṅgama Sūtra. The sutra teaches that those free from impediments caused by sense organs, faculties, consciousnesses, and material elements will see everything from ten directions with penetrating accuracy and clarity (SLYJ, T 945.19:109b–119b). More specifically, ten directions account for the four cardinal directions, their four intermediate directions, the top, and the bottom. Wu Bin followed the first eight directions but chose two sides of the bottom instead of one seen from the top. Such a decision was perhaps to overcome the limitations of the eye faculty. In Buddhist epistemology, especially that illustrated in the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, the eye faculty is incomplete because it fails to perceive two corners of the subject’s back (SLYJ, T 945.19:122c). When a rock stands as a perceived object, its bottom is inconceivable in plain sight. The clear-cut, flat bottom also suggests that the depicted rock was initially the topmost part of a bigger piece of rock, consisting of multiple peaks, thus the rarest. To capture the rare piece of rock from angles that no one else can easily see, Wu Bin dared to remove it from the pedestal, flipped, observed, painted, and even inscribed his signature—“Wu Bin writes (Wu Bin xie)”—as if it were permanently engraved on a deep, dark cavity at the bottom of the stone (Figure 2).19 In this unassuming signature, Wu Bin registers his capacity to see this object comprehensively. Through this signature in the tenth view, the metaphoric number ten further underscores the potential to see the true nature of all existence and manifestations.

Figure 4.

Facial angles for portraiture from Pictorial Compendium of the Three Powers, 1609. Woodblock prints on paper. Photo: Courtesy of München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

Wu Bin’s contemporaries did not regard the seeming bizarreness in his paintings as a mere reflection of the painter’s eccentric personality or meaningless imagination. Instead, they appreciated it as the materialization of the transcendental vision of the awakened one. The eminent scholar-official Gu Qiyuan (1565–1628) probes the complex process of truth-making illusion caused by the collision between the object and the Mind, in the colophon he wrote after Wu Bin’s Five Hundred Arhats, consecrated in the Qixia Temple, Nanjing.20 This colophon was written in response to Wu Bin’s request to record what he dreamed before creating the painting. Although extremely lengthy, part of Gu Qiyuan’s colophon is worth discussing here:

A monk named Wujie from Sichuan came to see the master [Wu Bin], soliciting paintings of the Five Hundred Arhats from Wu Bin, to have it as a dharma treasure at Mount Ming [in Sichuan]. As Wu Bin silently rejected [the request] at that moment, the monk wrote a gāthā and left. After ten days, Wu Bin fell asleep and had a sudden dream, in which the monk leads the crowd to venerate the Buddha. When Wu Bin also joined the prayer, there was a thunderous sound and earthquake. Strange creatures with wings were brimming in the sky, with the monk staring down from the platform, the Vajra guardian, and Vināyaka. Everyone revealed different forms with bizarre garments. When Wu Bin panicked and wanted to run away, there was a loud sound saying: “You cannot return until you fully depict our appearances.” Then Wu Bin asked for a brush and painted them. Suddenly there was a troop [of guardians] with blades as if they were trying to cut Wu Bin’s hair. Wu Bin woke up and painted the Five Hundred Arhats from his heart. Because these paintings are from what he saw in his dream, there are winged guardians. …Wu Bin believes all phenomena arise from the mind, [all causes] start from the dream; nevertheless, one cannot verify or refer to the past dreams. [Thus] He asked me to record it.One hears this story and may doubt that it is all fiction. Then I say it is not. In this dream, there are six afflictions and four conditions. In essence, [the dream] returns to the perception, and there is a cause [of all phenomena]. [When one wants to] follow cognitive faculties and their sense objects and runs like a disordered wheel, then [he/she would] waste breath because of habituated tendencies concealed in the repository. The perception changes incessantly; what really follows is the only enlightened mind.Today, people do not comprehend the essence of consciousness. They follow the false reputation of being awakened from the dream. …There is a dream because of a dream; a dream is called a dream because there is an awakening. What is manifest in the dream is the shadow of the awakened status. What you ponder during the awakened status is the cognitive object in the dream. …Water essentially becomes salty as it flows into the sea, so do sense objects when they come into the Mind. How can we ordinary beings know that Wenzhong’s dream bears fruits as illusory objects, and the painting by Wenzhong is real? The real is not the real; the illusion is not an illusion. Thus, no matter the material appearance on paper is exquisitely painted, I am afraid it is so muted that it is difficult to discern. …It is because Wenzhong has long planted good seeds and stored them in depth [of his consciousness] as pure perception. Thus, he can truly investigate the realm of the numinous, in quiet acquiescence with the sage lineage of patriarchs, and also assisted by [the actions in] his past lives, he finally reaps a good fruit (Gu Qiyuan, “Record of the Painting of Dreaming Five Hundred Arhats”, in Ge Yinliang 1607, 4:23b–25b).

As far as Gu Qiyuan is concerned, Wu Bin’s ability to see and to paint is not simply extraordinary. It is a pure or even enlightened form of a perception that emerges from seeds accumulated in the past and present and deposited in the storehouse of his consciousness (Lusthaus 2002, pp. 512–13). When these seeds bear fruit in the form of experience in the next life, they divide the world into phenomena and the physical body; the distinction between the two is an illusion. In this context, the painter’s act of distinguishing the perceiving subject and the perceived object through excessive looking may engender illusion. The Śūraṅgama Sūtra likens this process to staring at objects until the eyes become so tired that they see flowers in the sky. The significance lies in the attempt to push one’s sense faculty to the extreme until it creates an illusion and, to that end, a clearly perceivable material world.21 When one realizes the nature of illusion as reflections of our experiences, behaviors, cognitions, and desires deposited in storehouse consciousness, the perception of ultimate reality occurs. As Lynn Struve suggests, in the late Ming, the soteriological program of dream visions was no longer limited to eminent monks but considered attainable by ordinary minds (Struve 2019, p. 101). Gu Qiyuan believed Wu Bin had grasped this process of enlightenment and obtained a transcendental vision, which could envisage the world indiscernible to eyes of others.

Regarding the interfusion of otherworldly spectacles and what one may call realism in Wu Bin’s paintings, James Cahill proposed a possible influence from the newly imported European pictures (Cahill 1982, pp. 70–94). Chinese viewers, Cahill claimed, considered illusionistic engravings from the West as super-real images of unverifiable visions because they “had no way of knowing where visual reporting ended and fantasy began (Cahill 1982, p. 98).” Cahill’s pitch is certainly appealing when we limit the meaning of illusion—“fantasy” in Cahill’s word—within pictorial illusionism as generated by mimetic representational methods. In fact, Wu Bin’s possible exposure to European artworks is only circumstantial because many works by Wu Bin precede the circulation of the Jesuit illustrated books, such as Jerome Nadal’s (1507–1580) Evangelicae Historiae Imagines.22 Nadal’s illustrated gospel entered China around 1606 and was translated into Chinese by the Jesuit missionary Giulio Aleni (1582–1649) in 1637. Nevertheless, one cannot deny that Wu Bin’s residence in Nanjing briefly overlapped with the Jesuits arrival to the southern capital of the Ming dynasty. What should be noted here is not the potential European “impact” on seventeenth-century Chinese painting but the religio-philosophical discourses on perception that shaped the intellectual landscape proximate to the painter and his audiences. Nanjing and other cultural centers of China in the dawn of the seventeenth century were perhaps the rendezvous of the two emerging interests in embodying optical experiences, which can be further explored in later studies from a comparative perspective.

2. Conclusions

Once Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock became a spectacle, the scroll was exhibited nationwide in the two capitals—Beijing and Nanjing, travelling all the way to the southernmost Fujian province in the following five years. Some of the colophon writers saw the stone; for others, the painting substituted for the presence of the stone. Regardless of whether they saw the stone in person or not, all writers confirmed the presence of the tridimensional stone once they optically experienced the bidimensional representation. Such an effect of make-believe would be possible because Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, as an image, has the capacity to appear to the viewers as if it came into being without their effort by virtue of its ontological autonomy (Morgan 2018, p. 63).23 These temporally and spatially diverse acts of looking and beliefs in the existence of the rock came to be accumulated and assembled on the flat surface of an art object.24 In this way, the Lingbi stone exists in the interrelated sensory spheres experienced by different ocular faculties. Within this shared world, even when the vision of one of the onlookers ceases through death, the presence of the stone would remain in the minds of those living. Mi Wanzhong writes at the end of his inscription to the tenth view, “Since we have portrayed the ten views, the act of looking must stop here, but the mind will perpetuate to cease only at infinity.”

The late Ming collecting culture reflects the practices of self-fashioning through consumerism and materialism, as many scholars have already discussed.25 What has not been noted in this context is that the collectible rocks and paintings or catalogues of them were not merely commodities as objects of aesthetic pleasure. The appreciation of collectibles, “wanshang”, literally meaning playing and appreciating, elicited playing with scale, numbers, various sensory experiences, and even ontological questions. Meticulous documentation of intensive optical experiences constructed the authenticity of the perceived things, which could be a version of personal reality. The quasi-realistic depiction of the rock that Wu Bin achieved, I suggest, cannot simply be reduced to pictorial illusionism. Ten Views of Lingbi Rock triggers an impulse to see beyond “what is nonetheless already there” (Barthes 1981, p. 55).

Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock attests to seventeenth-century perceptual engagement that brought an art object into being. Sensory experiences—particularly optical ones—and questions about the reality of perceivable things were involved in this process of making Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock a work of art in presence. Creators and beholders of the object sought answers from Buddhist epistemological ideas, as this paper probed. One may ask, then, if Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock is a “Buddhist” painting? As Raoul Brinbaum points out, through visual media, seventeenth-century elites with strong Buddhist commitments would articulate concerns directly important to them from Buddhist perspectives (Birnbaum 2016, p. 94). Wu Bin’s social status as a professional painter did not deter him from becoming a scholarly lay Buddhist. Lavishing support from his major patrons, ever-growing lay Buddhist communities, and the proliferation of publications in the late Ming might have provided him with intellectual resources to join the conversation using his own painterly language.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies Graduate Student Associates Research Fund.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Professors Eugene Wang, Yukio Lippit, Melissa McCormick, and Jinah Kim for advising and encouraging me to pursue this study. Thanks should also go to my colleague Isabel McWilliams, who has patiently been reviewing countless versions of my study for many years. Lastly, I would like to extend my thanks to the two anonymous reviewers whose insights have significantly contributed to polishing my manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Ten Views of a Lingbi rock became known to the world through an auction sale in 1989 (Sotheby’s 1989, p. 43). The painting was formerly in a private collection in New York until it was sold at an auction held at Poly Art Museum in Beijing in October 2020. For the first article focusing on Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, see (Hu 1998, pp. 65–81). The advent of a discourse on the “late-Ming sensibility”, a literary framework that refers to blurred borderlines between reality and illusion circa 1600, has elevated the strangeness and eccentricity of the scroll and authors since the 1990s. See (Zeitlin 1993, p. 7), (Zeitlin 1999, pp. 40–47). Recent essays on Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock follow the “late-Ming sensibility” framework, material culture, and late Ming fascination with eccentricity and individuality. See (Huang and Jia 2012, pp. 62–67), (Bloom 2019). I am grateful to Phillip for sharing his conference paper with me in 2019. For more introductory essays, see (Flacks 2017) and (Baoli yishu yanjiuyuan 2020). (Flacks 2017) contains transcriptions and translations of the inscriptions and colophons, which require the reader’s discretion. |

| 2 | In the 1960s, Wu Bin was introduced to the American audience as one of the “fantastic and bizarre masters” of a “frustrated and restless generation.” (Cahill 1967, pp. 28–32). For the discussion on the Cold War discursive component that shaped the notion of eccentricity in the East Asian art studies, see (Lippit 2020, pp. 34–43). For further discussions on Wu Bin’s eccentricity and originality, see (Cahill 1972, pp. 637–98). In a similar context, (Burnett 1995); (Burnett 2006, pp. 2–15); (Burnett 2013, pp. 221–90). For Wu Bin as a lay Buddhist painter, see (Chen 2013, pp. 251–78); (Pawlowski 2019). For a special exhibition that introduced Wu Bin’s works as strange and eccentric, see (He and Chen 2012). For Cahill’s hypothesis on Wu Bin’s possible exposure to European pictures, see (Cahill 1982a, pp. 95–98). A similar perspective is also found in (Fong 1996, pp. 406–7). |

| 3 | John Hay’s discussion on the painterly practice of “seemingly objectified observation” motivated the onset of my research. (Hay 1992, pp. 4-1–4-22). |

| 4 | My methodology is inspired by the mechanism of “seeing as making” proposed by Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison in their remarkable study on the history of scientific objectivity. (Daston and Galison 2007, pp. 363–416). |

| 5 | I regard an art object, Wu Bin’s painting in this case, as a “thing” that is different from a Thing (wu), which can be the Lingbi rock itself, in the Chinese context (Lau 1967, pp. 353–57). The idea of an object as an entity coming into being comes from Heidegger’s exposition on characteristics of Being as substantiality, materiality, and side-by-side-ness. (Heidegger 2010). |

| 6 | The original text is from Mi Wanzhong’s colophon to Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, written in 1610. All translations in this article are mine unless noted otherwise. An alternate translation for this phrase is found in (Lynn 2017, p. 18). |

| 7 | Arnold Chang has introduced that the former owner of Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock, in fact, created a 3D model of the rock based on the painting. See (Chang 2020). |

| 8 | For an alternate translation, see (Lynn 2017, p. 54). But Lynn interprets the process of painting by reading that Wu Bin left some parts unfinished and went back to finish those later. |

| 9 | For partial English translation, see (Schafer 1961, pp. 50–51); (Campbell and Hardie 2020, pp. 106–7). For additional descriptions of Lingbi published in English, see (Scogin 1997, pp. 37–55). |

| 10 | Du writes that even tall, awe-inspiring ones owned by famous Mr. Zhang of Lingbi had two or three views, but one of those was often covered with condensed mud and had to face the wall when displayed (Du Wan, shang:1b). |

| 11 | In Zhu’s essay, “feifei shi” is translated as “Not Not Rock.” I use my own translation as “not-not real rock” to clarify its meaning, which is “a real rock that exists.” The connection between Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock and the name “not-not real rock (feifei shi)” requires reassessment. Many scholars have associated this name with Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock since Mi’s Zhan Garden was known to have the famous “not-not real rock” displayed. However, the description of the “not-not real rock” at Zhan Garden written by the biographer Sun Chengze differs from that in Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock. See (Sun Chengze, 65:17b). |

| 12 | There were more paintings by Wu Bin documenting Mi Wanzhong’s rocks. The Korean scholar-official Bak Jiwon (1737–1805) once met a dealer in Beijing selling a corpus of Wu Bin’s paintings that depict various rocks from Mi Wanzhong’s collections. The batch included pictures of a Lingbi, square platform rock, Ying stone, Chouchi stone, Yan stone, not-not-real rock, blue stone, and a yellow stone, Bak writes (Bak Jiwon, p. 254). There was also an illustrated document of Mi Wanzhong’s collection of twenty-five Lingyan stones, which refer to multicolored, small, pebble-like agate made from the unique geology of the area around Liuhe near Nanjing. The Nanjing-native writer Xu Zemian’s Records on the Illustrations of Lingyan Stones notes that there were corresponding pictures to the eighteen entries that document their colors and patterns with poetic names of individual stones (Xu Zimian in GJTSJC, 8.shibu:45a–49b). For another account about Mi Wanzhong’s Lingyan stone collection and its pictorial catalogue, see (Sun Guomi in GJTSJC, 20.shibu: 45a–51b). |

| 13 | For detailed discussion on Hanshan Deqing’s life and scholarship, see (Hsu 1979); for his syncretic thoughts on Yogācāra and tathāgatagarbha, see (Chen 2001) and (Cui 2001). For a summary of Hanshan Deqing’s commentaries on Daoist texts from the Yogācārin metaphysical perspective, see (Struve 2019, pp. 93–97). For Yunqi Zhuhong, see (Yü 1981). For Ouyi Zhixu’s practices and writings focusing on karmic redistributions, see (McGuire 2014). |

| 14 | For Chinese rock appreciation, among many, see (Hay 1985; Mowry 1997). For various ways of seeing in understanding the physical world in the late Ming period, see (Nappi 2010, pp. 38–41). |

| 15 | As a lay practitioner, Mi Wanzhong participated in major Buddhist enterprises around Beijing and built private temples on his estates. For further discussions, see (Zhang 2016; Huang 2014). |

| 16 | For further discussions on this painting album, see (Chen 2002). For possible reidentification of some deities in the album, see (Lo 2016). |

| 17 | The method of contemplating upon “dust”, as sensory and cognitive objects, had been elaborated in early Chinese Yogācāra text, such as the “Method for the Contemplation of Dust as Empty (Chenkong guanmen)” from the Haneda Dunhuang manuscripts. For further discussion on this Dunhuang manuscript, see (Greene 2017). I thank the reviewer who recommended me to historically contextualize this visualization method. |

| 18 | I am deeply indebted to the reviewer who kindly offered me this reference. The “ten suchlike aspects of reality” indicate characteristics (xiang), nature (xing), substance (ti), efficacy (li), function (yong or zuo), causes (yin), conditions (yuan), effects (guo), retributions (bao), and the totality of all nine suchnesses. The ten realms refer to the realms of hell denizens, hungry ghosts, animals, demigods, humans, celestial divinities, śrāvakas, pratyekabuddhas, bodhisattvas and buddhas. |

| 19 | Lynn reads the signature as “Wu Bin Wenzhong” (Lynn 2017, p. 27). Wenzhong is Wu Bin’s courtesy name. |

| 20 | One of the scrolls is currently housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. |

| 21 | Sense faculties refer to sendriyaḥ kāyaḥ (yougenshen); perceivable material world is bhājanaloka (qishi jian). This epistemological process is probed in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra. See also (Cheng weishi lun T 1585.31:10a; Zongjing lu T 2016.48:565a). |

| 22 | For newly imported European pictures in late Ming China and the Chinese version of Evangelicae Historiae Imagines translated by Gulio Aleni, see (Mateo 2010; Chen 2009; Lippiello and Malek 1997). |

| 23 | I am sincerely grateful to the reviewer for recommending David Morgan’s scholarship. |

| 24 | See (Goodman 1978, p. 8). A similar process is observed in the Yogācārin metaphysics in which collective sensory experiences are materialized and formulated as substance of things (Brewster 2018, p. 158). |

| 25 | To name a few among many, (Li 2022; Clunas 2004). |

References

Primary Sources

Bak Jiwon 朴趾源. Yeora ilgi 熱河日記.Cheng weishi lun 成唯識論. In Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經. Edited by Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡邊海旭. Tokyo: Issaikyō kankōkai, 1924–1932 (hereafter T). 1585.Da foding rulai miyin xiuzheng liaoyi zhupusa wanxing shoulengyan jing (SLYJ) 大佛頂如來密因修證了義諸菩薩萬行首楞嚴經. T. 945.Du Wan 杜綰. Yunlin shipu 雲林石譜.Ge Yinliang 葛寅亮. Jinling fancha zhi 金陵梵刹志.Hanshan Deqing 憨山德清. Hanshan laoren mengyou ji 憨山老人夢遊集. In Manji Shinsan Dainihon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Edited by Kawamura Kōshō 河村照孝. Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai, 1975–1989 (hereafter X). 1456.Hanshan Deqing 憨山德清. Lengyan jing tongyi 楞嚴經通議. X 279.Miaofa lianhuajing 妙法蓮華經. T 262.Mohe zhiguan 摩訶止觀. T 1911.Sun Chengze 孫承澤. Chunmingmeng yulu 春明夢餘錄.Sun Guomi 孫國敉. Lingyan shishuo 靈巖石說. In Gujin tushu jicheng fangyu huibian kunyu dian (GJTSJC) 古今圖書集成方輿彙編坤輿典.Wang Qi 王圻. Sancai tuhui 三才圖會.Xu Zimian 胥自勉. Lingyan shizi tushuo 靈巖石子圖說. In GJTSJC.Zhang Nai 張鼐. Baori tang chuji 寳日堂初集.Zongjing lu 宗鏡録. T 2016.Secondary Sources

- Araki, Kengo 荒木見悟. 1984. Yōmeigaku no kaiten to Bukkyō 陽明学の開展と仏教. Tokyo: Kenbun shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, He. 2020. Know Your Remedies: Pharmacy and Culture in Early Modern China. Princeton: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, Raoul. 2016. When Is a ‘Chinese Landscape Painting’ Also a ‘Chinese Buddhist Painting’?: Approaches to the Works of Kuncan (1612–1673) and Other Enigmas. In 17th-Century Chinese Paintings from the Tsao Family Collection. Edited by Stephen Little. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, pp. 94–129. [Google Scholar]

- Baoli yishu yanjiuyuan 保利藝術研究院編. 2020. Yanhe qizi: Wu Bin “shimian lingbi tujuan” tezhan 岩壑奇姿: 吳彬"十面靈璧圖卷"特展. Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Phillip E. 2019. Medium and Materiality in Wu Bin’s Ten Views of a Lingbi Stone. Unpublished conference paper for the Association of Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, Ernest Billings. 2018. What Is Our Shared Sensory World?: Ming Dynasty Debates on Yogācāra versus Huayan Doctrines. Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies 31: 117–170. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, Katharine P. 1995. The Landscapes of Wu Bin (c.1543–c.1626) and a Seventeenth-Century Discourse of Originality. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, Katharine P. 2006. Travel and Transformation: Wu Bin’s Enjoying Scenery along the Min River. Oriental Art L: 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, Katharine P. 2013. Dimensions of Originality: Essays on Seventeenth-Century Chinese Art Theory and Criticism. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, pp. 221–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, James. 1967. Fantastics and Eccentrics in Chinese Painting. New York: Asia Society. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, James. 1972. Wu Pin and His Landscape Painting. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Chinese Paintings. Taipei: National Palace Museum, pp. 637–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, James. 1982. The Compelling Image: Nature and Style in Seventeenth-Century Chinese Painting. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Duncan, and Alison Hardie, eds. 2020. The Dumbarton Oaks Anthology of Chinese Garden Literature. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Arnold. 2020. Wu Bin’s ’Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock’: Rediscovering a Masterpiece That Was Never Actually Lost, Curator Conversation, Norton Museum of Art, Palm Beach, FL, USA.

- Chen, Hui-Hung. 2009. Chinese Perception of European Perspective: A Jesuit Case in the Seventeenth Century. The Seventeenth Century 24: 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Songbo 陳松柏. 2001. Hanshan Chanxue zhi yanjiu—yi zixing wei zhongxin 憨山禪學之研究—以自性為中心. Dashuxiang: Foguangshan wenjiao jijinhui. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yunru. 2002. Wu Bin <Hua Lengyan ershiwu yuantong ce> yanjiu 畫楞嚴廿五圓通佛像研究. Guoli Taiwan Daxue meishushi yanjiu jikan 13: 167–199. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yunru 陳韻如. 2013. Qihuan zhenru: Shilun Wu Bin de jushi shenfen yu qi huafeng 奇幻真如: 試論吳彬的居士身分與其畫風. Zhongzheng hanxue yanjiu 21: 251–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, William. 2010. The Timing of Yogācāra Resurgence in the Ming Dynasty. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 33: 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Clunas, Craig. 2004. Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Sen 崔森. 2001. Hanshan sixiang yanjiu 憨山思想研究. Dashuxiang: Foguangshan wenjiao jijinhui. [Google Scholar]

- Daston, Lorraine, and Peter Galison. 2007. Objectivity. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flacks, Marcus. 2017. Crags and Ravines Make a Marvellous View: A Study of Wu Bin’s Unique 17th Century Scroll Painting “Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock”. London: Sylph Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, Wen C. 1996. The Expanding Literati Culture. In Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Edited by Wen C. Fong and James C. Y. Watt. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Nelson. 1978. Ways of Worldmaking. Indianapolis: Hackett PubCo. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Beata. 1994. Mount Lu Revisited: Buddhism in the Life and Writings of Su Shih. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Eric M. 2017. The Dust Contemplation: A Study and Translation of a Newly Discovered Chinese Yogācāra Meditation Treatise from the Haneda Dunhuang Manuscripts of the Kyo-U Library. The Eastern Buddhist 48: 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Eric M. 2021. Chan before Chan: Meditation, Repentance, and Visionary Experience in Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, John. 1985. Kernels of Energy, Bones of Earth: The Rock in Chinese Art. New York: China House Gallery, China Institute in America. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, John. 1992. Subject, Nature, and Representation in Early Seventeenth-Century China. In Proceedings of the Tung Ch’i-ch’ang International Symposium. Edited by Wai-ching Ho. Kansas City: The Lowell Press, pp. 4-1–4-22. [Google Scholar]

- He, Chuanxin 何傳馨, and Yunru Chen. 2012. Zhuangqi guaifei renjian: Wu Bin de huihua shijie 狀奇怪非人間: 吳彬的繪畫世界. Taipei: National Palace Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2010. Being and Time. Translated by Joan Stambaugh. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Sung-peng. 1979. A Buddhist Leader in Ming China: The Life and Thought of Han-Shan Te-Ch’ing. University Park, Pennsylvania State: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Philip K. 1998. Porträt eines Steins-Worte und Bilder auf einer Querrolle von Wu Bin und Mi Wanzhong. In Wege ins Paradies Oder die Liebe zum Stein in China. Zurich: Museum Rietberg, pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Wei 黃薇. 2014. Mi Wanzhong ji qi dingzao ciqi yanjiu 米万钟及其订造瓷器研究. Gugong bowuyuan yuankan 174: 134–46. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xiao 黄晓, and Jun Jia 贾珺. 2012. Wu Bin Shimian lingbi tu yu Mi Wanzhong feifeishi yanjiu 吴彬《十面灵璧图》与米万钟非非石研究. Zhuangshi 232: 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, Din Cheuk. 1967. A Note on ‘Ke Wu’. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 30: 353–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Wai-yee. 2022. The Promise and Peril of Things: Literature and Material Culture in Late Imperial China. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lippit, Yukio. 2020. From Kisō to Kijin: Reconsidering Eccentricity in Edo Painting. Orientations 51: 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lippiello, Tiziana, and Roman Malek. 1997. Scholar from the West: Giulio Aleni S.J. (1582–1649) and the Dialogue between Christianity and China. Brescia: Fondazione civiltà bresciana. Sankt Augustin: Monumenta Serica Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Hui-Chi. 2016. Shifting Identities in Wu Bin’s Album of the Twenty-Five Dharma-Gates of Perfect Wisdom. Archives of Asian Art 66: 107–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusthaus, Dan. 2002. Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogācāra Buddhism and the Chʼeng Wei-Shih Lun. New York: RoutledgeCurzon. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, Richard John. 2017. Translating a Scroll: Wu Bin’s Paintings of Mi Wanzhong’s Fantastic Rock. In Crags and Ravines Make a Marvelous View: A Study of Wu Bin’s Unique 17th Century Scroll Painting “Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock”. Edited by Marcus Flacks. London: Sylph Editions, pp. 16–91. [Google Scholar]

- Marion, Jean-Luc. 1995. God without Being. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, José Eugenio Borao. 2010. La versión china de la obra ilustrada de Jerónimo Nadal Evangelicae Historiae Imagines. Revista Goya 330: 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Beverley Foulks. 2014. Living Karma: The Religious Practices of Ouyi Zhixu. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David. 2018. Images at Work: The Material Culture of Enchantment. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mowry, Robert D., ed. 1997. Worlds within Worlds: The Richard Rosenblum Collection of Chinese Scholars’ Rocks. Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museums. [Google Scholar]

- Nappi, Carla. The Monkey and the Inkpot: Natural History and Its Transformations in Early Modern China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Pawlowski, Anna. 2019. Sanctified Commodities: The Buddhist Paintings of Wu Bin (c. 1540–1626) and the Late Ming Buddhist Revival. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ryor, Kathleen. 2019. Style as Substance: Literary Ink Painting and Buddhist Practice in Late Ming Dynasty China. In Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World. Edited by Marco Faini and Alessia Meneghin. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 244–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, Edward H. 1961. Tu Wan’s “Stone Catalogue of Cloudy Forest”: A Commentary and Synopsis. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scogin, Hugh T., Jr. 1997. A Note on Lingbi. In Worlds within Worlds: The Richard Rosenblum Collection of Chinese Scholars’ Rocks. Edited by Robert D. Mowry. Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museums. [Google Scholar]

- Sotheby’s. 1989. Catalogue of Chinese Painting. New York: Sotheby’s. [Google Scholar]

- Struve, Lynn A. 2019. The Dreaming Mind and the End of the Ming World. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yü, Chün-fang. 1981. The Renewal of Buddhism in China: Chu-Hung and the Late Ming Synthesis. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin, Judith T. 1993. Historian of the Strange: Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin, Judith T. 1999. The Secret Life of Rocks: Objects and Collectors in the Ming and Qing Imagination. Orientations 30: 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Dewei. 2016. Where the Two Worlds Met: Spreading a Buddhist Canon in Wanli (1573–1620) China. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 26: 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Liangzhi. 2017. Wu Bin’s Picture Scroll: Lingbi Rock in Ten Views. In Crags and Ravines Make a Marvelous View: A Study of Wu Bin’s Unique 17th Century Scroll Painting “Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock”. Edited by Marcus Flacks. London: Sylph Editions, pp. 102–111. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).