Abstract

It is well-documented that patients’ religious characteristics may affect their health and health care experiences, correlating with better health and psychological well-being. Likewise, health care providers are impacted by religious characteristics that affect their attitudes and behaviors in a clinical setting. However, few of these studies examine non-theist, non-Western, or Indian-based traditions, and none have examined Jainism specifically, in spite of the high representation of Jains in medicine. Drawing upon a quantitative survey conducted in 2017–2018 of Jains in medical and healthcare fields, I argue that Jains physicians and medical professionals demonstrate a “reflexive ethical orientation”, characterized by: (1) adaptive absolutes emphasizing nonviolence, a many-sided viewpoint, and compassion; (2) balancing personally mediated sources of authority that evaluate and integrate Jain insights alongside cultural and legal sources, and clinical experience; and (3) privileging the well-being of five-sensed humans and animals.

1. Paper

In recent years, medical literature has explored how, and to what extent, patients’ and physicians’ religious and spiritual beliefs impact health outcomes, attitudes, or behaviors in health care contexts. It is well-documented, for example, that patients’ religious characteristics may affect their health and health care experiences (Craigie et al. 1988; King and Bushwick 1994; Kurtz et al. 1995; Gartner et al. 1991; Levin and Vanderpool 1987; McCormick et al. 2012; Mickley et al. 1992; Prado et al. 2004; Puchalski 2001b). Patients’ spiritual and religious identity, including personal practices such as prayer or beliefs about healing, is also shown to correlate positively with improved health and psychological well-being in times of illness or end-of-life decisions (Ai et al. 2008; Balboni et al. 2011; King and Bushwick 1994; Jim et al. 2015; Koenig et al. 2004; Pargament et al. 2004; Puchalski 2001b; Puchalski et al. 2009; Ringdal 1996; Sherman et al. 2009; Ai et al. 2009). Conversely, patients undergoing a “religious struggle” may have a greater risk of mortality or adverse health outcomes (Pargament et al. 2001, 2004; Sherman et al. 2009).

A growing number of studies further demonstrate that physicians are also impacted by religious characteristics that affect their attitudes and behaviors in a clinical setting (Curlin et al. 2005; Daaleman and Frey 1999; Hordern 2016; Robinson et al. 2017; Salmoirago-Blotcher et al. 2016). These studies largely explore doctors’ willingness or apprehension to engage in discussions regarding religious beliefs with patients or their surrogate decision makers (Appleby et al. 2018; Curlin et al. 2006; Ellis et al. 2002; Ernecoff et al. 2015; Handzo and Koenig 2004; Koenig et al. 1989; Luckhaupt et al. 2005; Monroe et al. 2003; Olive 2004; Sulmasy 2009) as well as physicians’ attitudes to particular healthcare practices such as euthanasia, aid-in-dying, or withdrawing life support (Baume et al. 1995; Christakis and Asch 1995; Doukas et al. 1995; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al. 1995; Schmidt et al. 1996; Wenger and Carmel 2004). Additional studies explore how providers might integrate spiritual or religious questions into their patient intake forms or other modes of clinical communication (Anandarajah and Hight 2001; Puchalski 2001a; Struve 2002).

However, few of these studies examine non-theist, non-Western, or Indian-based traditions, and none have examined the Jain tradition specifically, in spite of the high representation of Jain practitioners in medicine. Drawing upon a survey conducted in 2017–2018 of Jains in medical and healthcare fields, I address this gap in hopes of contributing to medicine and religion research, cross-cultural medicine, Jain studies scholarship, and the Jain community. Notably, I also hope to illuminate how some global religious adherents such as the Jains may not share certain features typically affiliated with western or monotheist traditions, including belief in a transcendent ultimate deity or minister-mediated communal worship and ritual. Nevertheless, their particular world visions and practices may still constitute a religious influence in medical settings, whether as patients or providers. I argue that Jains medical professionals utilize a “reflexive ethical orientation” characterized by: (1) adaptive absolutes emphasizing nonviolence, a many-sided viewpoint, and compassion; (2) balancing personally mediated sources of authority that evaluate and integrate Jain insights alongside cultural and legal sources, and clinical experience; and (3) privileging the well-being of five-sensed humans and animals.

2. Jainism as a Global Non-Theistic Tradition

Jainism is a religious–philosophical system that has been present in India for over 2500 years, according to historical records. Today, Jains live in over 30 countries outside India with the largest populations in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Kenya, and Belgium. Jains consider their tradition to be eternal. In the Jain Universal History, there is no ultimate deity or founder, but rather a series of 24 great teachers, called tīrthaṅkaras or Jinas, who exemplified a path of attentive knowing and restrained action toward all living beings based on the fundamental principle of nonviolence. The last two of these teachers are considered historical persons who oversaw a community of mendicant monks and nuns—Pārśva (8th–7th c. BCE) and Mahāvīra, meaning “great hero” (5th c. BCE), who was an elder contemporary of the Buddha. Mahāvīra and the Buddha represented distinct communities that challenged the Vedic dominance of the time by rejecting priestly authority, birth caste, and animal sacrifice. Mendicant followers of the Buddha and Mahāvīra were considered “strivers” (śramaṇa) who, through rigorous mental and physical restraints, could overcome their birth condition and pursue liberation without recourse to mediated religious rituals.

Since the tradition’s inception, nonviolence toward all beings—which came to be summarized in the term ahiṃsā—has been the ethical hallmark and the first of five great vows (mahā-vrata) taken by mendicants. The other four vows—truthfulness (satya), taking only what is given (asteya), mendicant celibacy (brahmacarya), and non-accumulation of goods (aparigraha)—are each understood as variations of the first. These vows resulted in iconic practices of Jain mendicants that may be familiar to some readers, such as monks and nuns wearing mouth shields to prevent disturbing organisms in the air, walking barefoot so as not to injure organisms in the earth, or using hand brooms to sweep the ground clear of organisms when walking and sitting. Unlike mendicants, lay Jains—who comprise the majority of the global Jain community today—participate in work, family, and home life. In these social contexts, lay Jains live toward minor vows (aṇu-vrata), or a weaker version of the great vows practiced by mendicants. Most lay Jains do not formally take these vows under the direction of a mendicant as prescribed in early texts devoted to the practices of lay life. Rather, the vows offer an orientation toward daily life—sometimes called the “Jain Way of Life”—that inform lay Jains’ habits of mind, vocational paths, consumer practices, or dietary commitments such as vegetarianism, although some lay Jains do undertake more stringent vows of fasting or meditation (Dundas 2002a, pp. 189–91; Jain 2007; Jaini [1979] 2001, p. 160; Laidlaw 1995, pp. 173–75; Scholz 2012).

3. Jains in Medicine: Survey Method

The complex history of Jainism and medicine is beyond the scope of this paper, though it has been explored elsewhere (Bollée 2003; Granoff 1998a, 1998b, 2014, 2017; Stuart 2014). It suffices to say here, as summarized in Ana Bajželj’s rich analysis of changing Jain views of medicine, that the community attitudes evolved from an occupation deemed unacceptably violent in the earliest texts, to one that was considered an acceptable and less violent occupation for lay people by the medieval period (Donaldson and Bajželj 2021)1.

Today, global lay Jains have high representation in medical fields. The National Health Portal of India lists over 200 Jain-sponsored hospitals and clinics; additionally, there are at least 25 Jain medical colleges in the subcontinent, and the Jain Medical Doctors Association of India has a partial directory of 23,400 Jain physicians.2

This medical presence is significant when considering the relatively small size of the global Jain population, estimated in 2020 at 0.44 percent (6 million) of the Indian population, with 285,000 Jains living abroad, according to the World Religions Database (WRD) at Boston University (Johnson and Grim 2022). A higher representation in medicine is also seen in diaspora countries such as the United States where many Jains arrived through the 1965 Immigration Act, which favored those with advanced training in medicine and allied fields. WRD estimates that 94,000 Jains live in the U.S. as of 20203. Of these, many work in medical or related fields. The Federation of Jains in North America (JAINA) reports a directory of approximately 600 Jain medical professionals in the U.S. and Canada.4

As part of our recently published book Insistent Life: Principles for Bioethics in Jainism, co-authored with Ana Bajželj, we designed an online survey titled “Foundations for Bioethics in the Jain Tradition” in order to assess Jain attitudes toward medicine and medical dilemmas. The survey—which included 130 multiple choice and open-ended questions5—was reviewed by two Jain physicians in order to clarify terminology and/or alter questions. The survey, along with an introductory video6, was circulated by email in 2017, through the assistance of medical associations in India, Jain medical professionals involved with JAINA, and Jain physicians and researchers in the private sector.

Overall, 62 participants interacted with the survey. We discarded any survey less than 10% complete, leaving 48 total respondents. Of these, 35 completed the entire survey, and 13 answered at least ten percent or more of the survey, meaning 35–48 participants interacted with each question. The gender ratio was 19 female/29 male. The age, place of birth, and country of residence for participants is as follows:

- Age (n = 48)

- 18–23 (8%)

- 24–29 (8%)

- 30–39 (8%)

- 40–49 (21%)

- 50–59 (15%)

- 60–69 (19%)

- 70–79 (17%)

- 80–89 (4%)

- Birth country (n = 48)

- India (58%)

- United States (19%)

- Kenya (13%)

- United Kingdom (4%)

- Tanzania (4%)

- Canada (2%)

- Country of residence (n = 48)

- United States (67%)

- United Kingdom (8%)

- India (8%)

- Kenya (8%)

- Canada (6%)

- Australia (2%)

Respondents reported their education levels as: M.D. (55%, n = 48), Ph.D. (4%), master’s degree (14%), four-year college (16%), high school (4%), and other (6%). Participants (n = 21) who optionally listed their M.D. specializations included: Internal Medicine and Surgery (6), Anesthesiology (3), Family Medicine (3), Pathology (2), Urology, Psychiatry, Emergency medicine, Neonatology, Pediatrics, Gastroenterology, and Cardiology. “Other” (n = 3) included: Doctor of Physical Therapy, pharmaceutical development, and three-year bachelor’s degree.

Three-quarters of the respondents identified with the Jain Śvetāmbara sect (and its subsects) (73%, n = 48). A smaller minority identified as Digambara (and its subsects) (25%). Some respondents identified themselves with two different sect identities (6%) or as followers of the Jain philosopher and mystic Śrīmad Rājacandra (6%).7 The primary research question was “Does the Jain tradition influence professional decision-making regarding bioethical dilemmas?; If so, how?” assessed through six secondary questions.8 From analyzing subsets of this data, I assert that Jain medical professionals utilize a “reflexive ethical orientation” characterized by: (1) adaptive absolutes emphasizing nonviolence, a many-sided viewpoint, and compassion; (2) balancing personally mediated sources of authority that evaluate and integrate Jain insights alongside cultural and legal sources, and clinical experience; and (3) privileging the well-being of five-sensed humans and animals.

4. A Jain Reflexive Ethical Orientation in Health Care

“Ethical orientation” is a concept that emerges from the fields of business and professional ethics, with minor crossover into medicine at present. In their review of ethical decision-making literature in business from 1996–2003, O’Fallon and Butterfield characterize the ethical orientation literature as having two main foci—a normative ethics approach to theory and ideals, and a descriptive ethics approach to empirically predicting behavior (O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005, p. 375). The authors note that religious commitment is cited infrequently in the target literature, deducing that it is a minor factor influencing one’s ethical orientation.

The absence of religion commitment as a salient factor may be due to the fact that one source for the concept of “ethical orientation” derives from the Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) developed by American psychologist Donelson R. Forsyth (1980; Forsyth and Berger 1982)9 and later modified by Hunt and Vitell (1986). These survey instruments have been utilized to build profession-specific theoretical frameworks in marketing, accounting, education, corporate ethics, and human resources, among others (de Silva et al. 2018; Douglas et al. 2001; Eastman et al. 2001; Greenfield et al. 2008; Helmy 2018; Pearsall and Ellis 2011; Shim et al. 2017). However, the EPQ makes no mention of religious or cultural influences whatsoever; rather, Forsyth’s original questionnaire invited participants to gauge their level of agreement or disagreement (rating one through nine) with twenty abstract ethical claims about harm, normative rules, and personal-versus-social morality. For example, one statement reads, “People should make certain that their actions never intentionally harm another even to a small degree.” Another reads, “Whether a lie is judged to be moral or immoral depends upon the circumstances surrounding the action.”10 The few researchers who have explored the EPQ in relation to medicine have had to utilize other survey instruments to gauge religious commitments (Eastman et al. 2001; Malloy et al. 2014), or infer religion as an unstated value within the EPQ (Hadjistavropoulos et al. 2003).

Beyond Forsyth’s framework, the concept of ethical orientation appears in decision-making literature that evaluates general core values as they are mediated by factors such as goal setting (Luzadis and Gerhardt 2012), personal temperament (Allmon et al. 2000), competitiveness (Kirby and Kirby 2015), or professional role (Eastman et al. 2001). Chen and Tang (2013) and Chen and Liu (2009) point out that few researchers identify religious identity as a major variable in business and professional ethics literature, including medicine, leaving a gap to which the present analysis of Jain medical professionals can contribute.

Moreover, I call this ethical orientation reflexive by drawing on the work of sociologist Bindi Shah whose research describes Jains living in diaspora as cultivating a “cataphatic reflexivity”, that is, a reflexive process of identity construction among diasporic Jains in the U.S. and the U.K., shaped through continuous reasoned reflection and revision of one’s thoughts and actions (Shah 2014, pp. 515–16).11 Although not all participants in our survey lived in diaspora, 92% lived outside India and all were engaged in professional fields significantly shaped by western medical epistemic frameworks.

Finally, I suggest that this reflexive ethical orientation has precedent within the oft-used phrase “Jain way of life”, described above, by which lay Jains flexibly cultivate certain daily habits of mind, buying practices, or dietary rules such as vegetarianism that reflect Jain ideals without formally taking the minor vows.

5. Reflexive Ethical Orientation 1: Adaptive Nonviolence in Non-Jain Contexts

The first reflexive ethical orientation I identify is that Jain medical professionals adaptively apply fundamental commitments, such as nonviolence, in contexts in which Jainism is lesser known, or unknown.

It is common for medical professionals to routinely interact with patients of different religious orientations (Kagawa-Singer and Blackhall 2001; Carrillo et al. 1999; Crawley et al. 2002; Emanuel and Emanuel 1992; Lawrence 2002; Hall and Curlin 2004). Moreover, U.S. physicians who claim a religious identity are more likely than patients to come from a tradition that is underrepresented such as Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, etc. (Curlin et al. 2005).

The lack of familiarity with Jainism as a global tradition to those outside of India is evidenced in the lack of literature related to Jains in healthcare generally. On one hand, the small size of the global Jain population may warrant this exclusion. However, it is also significant that most studies exploring religiosity among healthcare professionals utilize measurements that are not as applicable to Jainism (or other underrepresented traditions). For instance, one of the more comprehensive studies of religious characteristics of U.S. physicians (Curlin et al. 2005), measure religiosity according to standards that include “religious service attendance” or “belief in God”, which would not apply to a non-theistic tradition such as Jainism that does not posit a universal deity nor is its practice characterized by communal services mediated by a religious leader. Although the authors of this study helpfully concede that the measures of “generic religion” they utilize “incompletely represent the ways in which religious commitments are embodied and experienced in any given individual or community”, the inability to capture non-Western ways of cognizing self, devotion, kinship, and ultimacy likely impact overall results (Curlin et al. 2005).

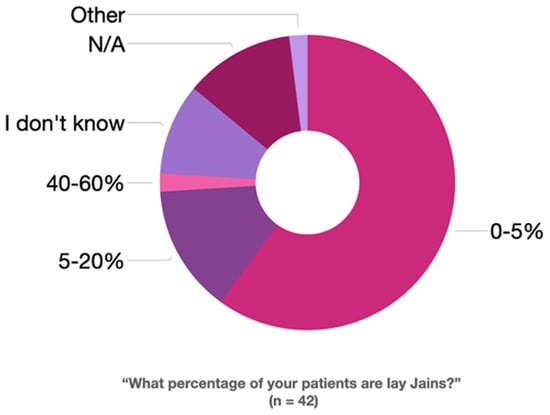

Beyond Jainism being a lesser-known global tradition, the Jain medical professionals who participated in our survey work largely in non-Jain contexts. Sixty percent of respondents stated that 0–5% of their patients were Jain (n = 42; Figure 1). At the same time, fifty-seven percent affirmed it was important for colleagues to know they were Jain (very 33%, moderately 24%; n = 42), while 38% felt it was important for patients or students to know they were Jain (very 17%, moderately 21%; n = 42).

Figure 1.

Survey Question: “What percentage of your patients are lay Jains? (n = 42)”.

I assess the overall commitment of Jain medical professionals to aspects of their tradition utilizing several survey questions. The majority of survey participants considered themselves very committed (57%; n = 42) or somewhat committed (31%) to Jain beliefs. Likewise, participants were very committed (71%; n = 42) or somewhat committed (21%) to Jain ethical practices. Fewer respondents were very committed (14%; n = 42) or somewhat committed (33%) to Jain ritual practices.

The discrepancy between adherence to belief or practice over ritual reflects what some scholars call a “neo-orthodox” turn among modern Jains, especially in diaspora, that emphasizes the tradition’s rational qualities and compatibility with science as taking precedent over ritual (Banks 1991, p. 247; Shah 2014, p. 519; Shah 2017). One scholar describes this as the “scientization” of the tradition (Auckland 2016). In previous work, I have argued that this perceived subordination of ritual to science, reason, or ethics by scholars can be overstated (Donaldson 2019a, 2019b; Miller and Dickstein 202112). Importantly, the belief/ritual split illuminates a persistent discrepancy within current research regarding medical professionals’ religious identity insofar as ritual or communal participation may not be an essential practice of a Jain who is otherwise dedicated to the world vision in their flexible “Jain Way of Life.”

To gain an additional sense of participants’ exposure to and identification with Jain ideals, I utilize survey questions related to temple education, community leadership, and diet. For example, three-quarters of participants had attended Jain temple education (pāṭhaśāla) during their lifetime (75%; n = 36), and over half of those attended for three years or more (53%; n = 36). A significant percentage had also served in a leadership or volunteer position for a Jain organization (42%; n = 36). One hundred percent of respondents practiced some kind of vegetarian Jain-informed diet (n = 42).

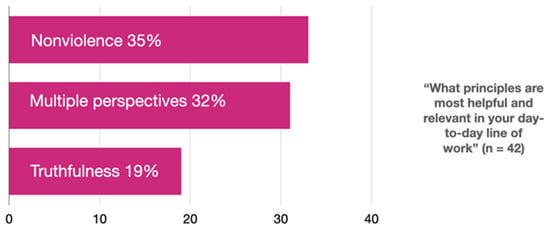

In terms of applicable concepts, eighty percent of respondents felt nonviolence had influenced them in a healthcare context (strongly agree 36%; agree 44%; n = 42) and when asked to identify principles “most helpful and relevant in your day-to-day line of work”, the top three responses included nonviolence (35%; n = 42), as well as two related Jain philosophical terms known as multi-sided viewpoint (anekānta-vāda; 32%) and truthfulness (satya; 19%; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survey Question: “What principles are most helpful and relevant in your day-to-day line of work? (n = 42)”.

In an open-ended question in which respondents were asked, “Have you ever considered Jain principles when trying to solve an ethical question in your work”, some respondents named basic Jain terms such as nonviolence, compassion13, multiple viewpoints, or honesty. Others, however, narrated relevant situations that required particular principles explicitly or implicitly. For instance, one respondent described asking a patient and her daughter to consider the pros and cons of a given choice, a possible implicit reference to anekānta-vāda, or multi-sided view. Another professional detailed ethical dilemmas related to dispensing medication, and the need to inform patients that s/he receives no financial incentive for prescribing particular medications, possibly referring implicitly to the vows of truth and non-stealing.14 Another described discussing “mental resilience and mindfulness techniques” explicitly derived from Jain restraints as part of treating depression with reduced side effects. Over half affirmed the question “Do you feel that being a Jain give you any advantages or insights in your professional field” (54%; n = 42).

It is further noteworthy that these commitments created tensions in some respondents’ professional lives, which speaks to the level of adherence. While only one-tenth of respondents affirmed that, “My commitments to Jain principles has put my professional career at risk at least one time” (10%, n = 42), a significant minority of Jain medical professionals had been chastised for their Jain beliefs or practices in a professional setting. About one-third reported being rarely teased or made fun of (29%; n = 42), with lesser accounts of being frequently teased or made fun of (10%), or being frequently assertively bullied (17%). Those who described the incidents attributed the chastisement as related to “having compassion for animals; viewing them as conscious entities”, “vegetarian diet and avoiding alcohol”, “being told I was short [in stature] because I did not eat meat”, and failing “an Advanced Trauma Life Support class [offered by the American College of Surgeons] when I refused to use animals.”15 Three additional responses referred to the Jain diet or vegetarianism.16

In sum, although the majority of Jain medical professionals surveyed work in non-Jain contexts, many still seek to be identified as Jain, and utilize Jain principles in flexible ways to meet professional ethical dilemmas, even if those principles are unknown to others or, more rarely, open one to ridicule.

6. Reflexive Ethical Orientation 2: Balancing Multiple Sources of Knowledge

The second reflexive ethical orientation involves Jain medical professionals balancing multiple sources of valid knowledge. Namely, survey responses reveal that a commitment to one’s identity as a Jain and as a medical professional pose some conflicts for respondents. A significant percentage of respondents reported having “encountered a conflict between an aspect of the Jain tradition and modern scientific knowledge” (47%, n = 43), as well as “between an aspect of the Jain tradition and [their] clinical experience and/or medical/healthcare education” (53%, n = 39).

Among the various responses describing these conflicts (n = 34), I include a few here to highlight the respondent voice: “When patients are advised to eat non-veg food, the modern scientific knowledge is not looking at holistic approach whereas Jainism emphasizes harmony for all”; “drug testing and testing of experimental drugs/devices on animals”; “animal autopsy”; “how to test new medical treatments without injuring animals or innocent humans”; “I refused to take part in dissection at school anatomy. Now it is better as [students] can have [project-based learning] and computer-based learning”; “[I]n terminally ill patients—I wish people [would] accept the end and practice modified sallekhanā and not have desire to hang onto life when physicians can’t do more”; “I believe in evolution and sometimes Jain principles do not align with the evolution theory”; “giving out flu vaccines cultured in egg yolk to meet corporate goals”; “Abortion. Animal products in drugs. Euthanasia”; “difference in the definition of death: Jainism believes that leaving in vegetative state prevents the liberation of soul when scent wants to prolong that”; “Jain geography and reincarnation”; and “I don’t think Jain principles conflict with modern science. In India, Jains own more pharmaceutical business than any other religion which [is] the point of science.”

How did respondents deal with those conflicts? Presented the statement, “When an aspect of the Jain tradition is at odds with a claim in modern society (choose all that apply)”: many professionals accepted the presence of some discrepancy (43%; n = 42), while significant minorities either adjusted their Jain belief and practices to some degree (31%), or maintained a strong commitment to Jain beliefs and practices even amidst such tensions (26%).

Respondents chose a variety of actions to reconcile conflicting beliefs, with the most significant being: (1) reason it out in my own mind (50%; n = 42), (2) discuss it with friends (43%), (3) read a specific Jain historical text (33%), (4) consult a Jain elder in my family or community (33%), (5) consult a monk/nun (31%), (6) discuss it with parents (24%), discuss it with sibling/s (24%), and explore texts by contemporary Jain authors (24%), among other lesser-selected options such as discussing it with a non-Jain medical/healthcare colleague (19%). Relatively few respondents reported “a professional experience or encounter that forced [them] to abandon a specific Jain belief or practice” (Yes 13%, No 78%, Not considered before 10%; n = 40).

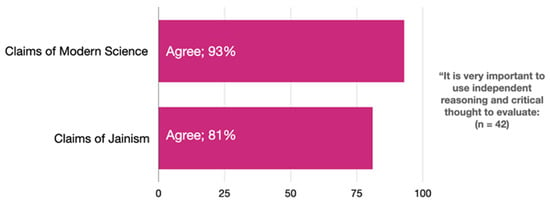

Further, the value of individual reasoning in negotiating conflicting knowledge systems is highly valued among the Jain medical professionals. Respondents believed it was “very important to use independent reasoning and critical thought to evaluate” both the claims of modern science (93%; n = 42) as well as the claims of Jainism (81%, n = 42; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Survey Question: “It is very important to use independent reasoning and critical thought to evaluate: (n = 42)”.

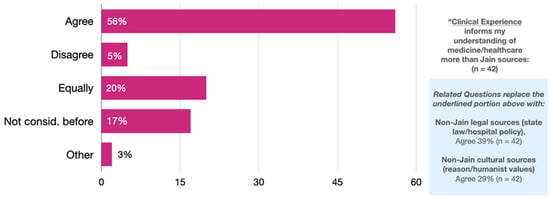

Perhaps reflective of the logic of anekānta-vāda, Jain medical professionals utilized multiple sources of knowledge to inform their understanding of ethical challenges in healthcare. Many respondents claimed to be considerably more informed by clinical experience than by Jain sources, and to a lesser-degree also more informed by non-Jain legal sources and non-Jain cultural sources than by Jain sources (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Survey Question: “Clinical Experience informs my understanding of medicine/healthcare more than Jain sources: (n = 42)”.

Additionally, when asked to freely describe in writing their current ethical framework or the principles they use when evaluating dilemmas in their professional life, about half of participants (47%, n = 36) described diverse concepts. Of those respondents, nearly two-thirds cited Jain principles such as nonviolence, multiple perspectives, pursuing positive karma, truth, non-stealing, and right thought, speech, and conduct (60%, n = 20), but the remainder referenced clinical sources such as medical ethics training, responsibility, or autonomy (25%), or just one’s own individual reasoning (15%).

7. Reflexive Ethical Orientation 3: Privileging Concern for Humans and Animals

The third reflexive ethical orientation involves Jain medical professionals privileging concern for five-sensed humans and animals. In the Jain cosmology, the universe (loka) is described as eternal and packed full of infinite living beings, each with its own core life force (jīva) on a continuous cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, known as saṃsāra. Although each singular jīva is understood to possess innate qualities of consciousness (upayoga; with two aspects of pure knowledge and pure perception), energy (vīrya), and bliss (ānanda), the full expression of these qualities is conditioned by each being’s accumulated karma, which also determines the kind of body a being possesses during a given lifetime.

Bodies are categorized by the number of senses they possess. Minute organisms and plants possess the single sense of touch. Two-, three-, and four-sensed beings, including mollusks, worms, spiders, moths, etc., have the additional senses of taste, smell, and sight, respectively. Five-sensed beings who possess hearing include mammals, birds, fish, humans, as well as divine and infernal beings, the latter of which I will forego for the present discussion; many five-sensed beings are also said to possess mind.17

Karma is uniquely theorized in the Jain tradition as a kind of material particle that accrues to the jīva based on damaging thoughts, speech, or action. That is, karma can be considered a kind of self-inflicted consequence that takes place constantly through the various actions of existence. Additionally, the amount of karma accrued in a given action is also relative to the kind of being injured. For example, one accrues more karma for harming a five-sensed being than a one-sense being, not only because more senses are violated, but because of the mental intention and effort required to injure a higher-sensed being; a careless person may accidentally injure an earth-bodied being when walking, or even two–four-sensed insects, but killing a five-sensed chicken, or supporting one who does, takes many more steps of effort (Donaldson 2022). For this reason, nonviolence, or ahiṃsā, emerges logically as a moral guide to minimize interference with all beings generally, and higher-sensed beings specifically.

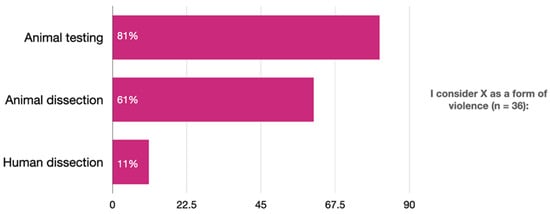

As noted above, all the survey respondents practiced some form of Jain vegetarianism in their dietary commitments, reflecting the tradition’s strong aversion to harming five-sensed beings for food. Respondents also expressed considerable agreement on their discomfort with animals used in medicine. The majority of respondents agreed that animal testing is a form of violence (81%, n = 36). Likewise, a majority considered animal dissection for educational and/or research purposes a form of violence (61%, n = 36)—versus only eleven percent who felt dissection of human cadavers constituted a form of harm (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Survey Question: “I consider X as a form of violence (n = 36)”.

In spite of opposition to dissection, nearly three-quarters of respondents had dissected a deceased animal as part their medical training (72%, n = 36). Animal testing—on live animals—paints a slightly different picture. About one-quarter of respondents had participated in animal testing as part of their medical/healthcare training (25%, n = 36). However, a significantly larger percentage had either “declined to test on animals, advocated against testing on animals, or suggested alternatives to animal testing in [their] medical/healthcare training or work” (39%, n = 36).

This statistic might contribute to an ongoing debate among Jain Studies scholars as to the degree to which Jainism provides “interventionist” ethics as alluded to in the early canonical formulation of three modes of causing harm: “‘I did it;’ ‘I shall cause another to do it;’ ‘I shall allow another to do it’” (ĀS I.1.1.5). Indeed, some scholars have illuminated how the term “allowing” (anumodana or nindā) evolved toward a less interventionist sense of mentally “approving” (Cort 2002, p. 74; Johnson 1995, pp. 10–11). Against the interventionist thesis, James Laidlaw has suggested that Jainism presents an “ethic of quarantine” (Laidlaw 1995, p. 153), while both Paul Dundas and John E. Cort expressed skepticism that the Jain emphasis on liberation (Cort 2002, p. 70) or the wider Jain cosmology, with its “teleology of decline” (avasarpiṇī) could support applied ethics (Dundas 2002b, p. 103). Animal rights activist Charlotte Laws—whose interest in Jainism initially led her to praise the “expanded moral vision” of Jainism as capable of challenging the exploitation of animal life (Laws 2006, p. 146)—ultimately surmised several years later, “No Jain that I met was willing to abandon their composed inner world for direct action” (Laws 2011, p. 58).

Yet, other scholars and Jain practitioners maintain that, especially among diaspora Jains in North America, the interventionist character of not “allowing” remains a strong feature of engaged ethical response. Anne Vallely, apropos to this paper, actually describes a “shift in ethical orientation” from a liberation-centric ethos associated with monks and nuns in India to a the “sociocentric understanding of Jain ethics” of some diaspora Jains characterized by nonviolent animal advocacy, environmental activism, promoting human rights, and other forms of practical engagement (Vallely 2006, pp. 203–9). Joseph A. Tuminello also evaluates distinct ethical responses toward institutionalized forms of violence among mendicant, orthodox, and diaspora Jains, with the latter taking a more interventionist approach. Tuminello concludes, “Many diaspora Jains believe that intervention to prevent or reduce violence and suffering is at least as important as spiritual practices such as meditation” (Tuminello 2019, p. 97). Even JAINA, under the leadership of physician Dr. Jhankhana Jina Shah and the JAINA Ahimsak Eco Vegan Committee, issued the 2019 Jain Declaration on the Climate Crisis containing detailed practical action steps to address climate change, not only for Jains urged to act “beyond tradition”, but also for non-Jain business and government leaders, demonstrating a public-facing ethical intervention focus (Climate Declaration 2019).

The fact that forty percent of Jain medical professional respondents publicly declined to test on animals or advocated alternatives may be suggestive of some forms of interventionist ethics. In light of emerging medical technologies and scenarios absent in early Jain texts, these unique medical responses could also exemplify what Cort calls “recovery scholarship” in which we look at what “Jains can do, might do, or should do in the future based on historical models …” as opposed to “what Jains have done” (Cort 2002, p. 68; emphasis original). It is pertinent here to recall an earlier figure I stated in which ten percent of respondents had felt their career was at risk at least one time due to their commitments to Jain principles (10%, n = 42), as well as the light teasing or aggressive bullying experienced by seventeen to twenty-nine percent of respondents, respectively.

The reflexive ethical orientation I suggest in this analysis leans toward a recovery scholarship model as a space between quietism and socio-political activism, which seems to be supported by ethnographic accounts—such as those conducted by Shah and Vallely above, as well as studies on the content of diaspora Jain religious education (Donaldson 2019a, 2019b; Bothra 2018)18—wherein primarily lay Jains describe living out their values in contemporary contexts for which there is no textual precedent. The JAINA Education Committee recently began a blogsite that provides Jain views of contemporary ethical issues ranging from gender inequality and adapting traditional views about menstruation and impurity, to climate, to military conflicts (JAINA Education Committee n.d.), demonstrating that Jains frequently adapt their worldviews to novel circumstances.

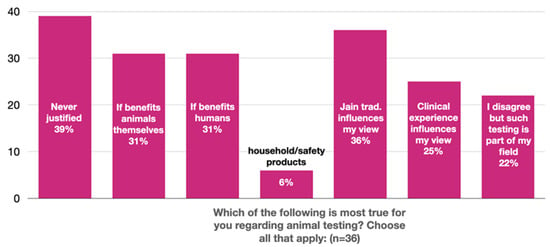

When respondents were asked to elaborate their views regarding animal testing, the greatest number of participants affirmed that animal testing can never be justified (39%, n = 36). However, many also felt it could be justified when the results benefit animals themselves (31%, n = 36), or when the results benefit human medical advancement (31%).19 At the same time, few felt animals could be used for safety tests on household products or cosmetics (6%, n = 36). A greater number of respondents claimed that their view on animal research was more influenced by the Jain tradition (36%, n = 36) than by their clinical experience or medical education (25%). A minority affirmed that though they personally disagreed with animal testing, it was a necessary part of their occupational training or responsibilities (22%, n = 36; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Survey Question: “Which of the following is most true for you regarding animal testing? Choose all apply: (n = 36)”.

This is not to say that respondents had no concern for beings with one through four senses, who are also used in medicine. Both vaccines and antibiotics, for example, utilize living beings in the substance itself and, when effective, destroy living beings deemed harmful to a patient’s health. These beings primarily take the form of bacteria, fungi, or other single-celled beings, which Jains would consider one-sensed (Bothra 2004, p. 17; Sikdar 1964, pp. 354–55; Sikdar 1975, pp. 12–14). Beyond this, vaccines and antibiotics are typically tested on animals prior to approval and may be produced using animal-derived ingredients in growth mediums or preservatives such as gelatin, enzymes, muscle tissue, or blood, among others.

The majority of participants (83%, n = 36) agreed that “the Jain framework of 1- to 5-sensed beings is a meaningful framework to make practical ethical decision in my personal day-to-day life.” A slightly lower percentage (61%, n = 36) of respondents felt that framework was meaningful in making practical ethical decisions in their professional daily life. Still, the majority of Jain medical professionals seemed to have little discomfort when considering vaccination. Almost no respondents felt that vaccinations presented a violation of Jain principles (3%, n = 36).20 In the comments for that particular question (8%, n = 36) respondents did raise concerns about vaccines being tested on animals, containing animal ingredients, or affirmed their value as “a preventative measure necessary for [human] well-being.”

Respondents’ views on antibiotics were more mixed and often centered on the tension between physical harm and mental intent. About one-third of respondents agreed (30%, n = 36) that antibiotics that may kill one-sensed organisms are a form of violence. Others disagreed (42%, n = 36), did not know (6%), had not considered the question before (11%), or selected “Other” (8%). Respondents’ comments fell in three areas: (a) the sacrifice of one-sensed organisms is done to benefit five-sensed beings, (b) the intended goal of healing neutralizes violation, and (c) that there is debate as to what constitutes a one-sensed being.

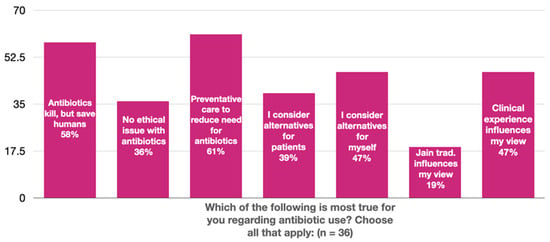

Likewise, when asked to elaborate their position on antibiotics, respondents acknowledged that antibiotics—while killing one-sensed organisms—were sometimes necessary to save human life. A greater number, however, emphasized preventative care to reduce the demand for antibiotics (61%, n = 36) and (58%). Therefore, according to this chart, while a sizeable minority did not see any ethical issues in using antibiotics (36%, n = 36), a greater number of participants considered alternatives to antibiotics when prescribing patient care (39%), as well as in their personal healthcare (47%; Figure 7). Interestingly, more respondents stated that they would accept antibiotics (36%, n = 36) as a form of Life Sustaining Treatment more than all other listed interventions such as blood transfusion (31%), dialysis (28%), and CPR (25%), among others, although this data likewise suggests that more than sixty percent of respondents may not accept antibiotics when the end of life is evident.

Figure 7.

Survey Question: “Which of the following is most true for you regarding antibiotic use? Choose all that apply: (n = 36)”.

On one hand, this hierarchy reflects the sociological fact that lay Jains do not have the burden carried by mendicants to avoid harming subtle beings in all circumstances, as evidenced by the iconic mendicant practices described earlier in this essay. At the same time, these survey respondents are not uniformly indifferent. Privileging human birth form, while maintaining a deep commitment not to harm other living beings, is one of many ways that Jainism exceeds either/or ethical orientations. Valley describes the “co-existence of an ideology of human exceptionalism with the active reverence for all life” (Vallely 2018, p. 15). Rooted in its commitment to not harm, “human privilege”, asserts Vallely, is established through a “fraternal solidarity” with the equality of jīva and the shared experience of suffering (Vallely 2018, pp. 15–16). She states, “Human exceptionalism resides singularly in its demonstration, through ethical behavior and practices of bodily detachment” (Vallely 2018, p. 14), a rare opportunity not to be wasted.

Although Jain medical professionals privilege the well-being of humans, followed by five-sensed animals, this concern is not exclusionary of other life forms, and provides another example of a reasoned “reflexive ethical orientation” by which Jain medical professionals offer notable clinical concern for living beings beyond the human.

8. Conclusions

Jainism is a global non-theistic tradition previously overlooked in the literature on religious influence in clinical medical settings. In this essay, I have drawn upon a recent survey of Jain medical professionals to offer tentative remarks on their reflexive ethical orientation; that is, how the Jain tradition might inform Jain healthcare practitioners’ clinical decisions and outlook. The main attributes identified include (1) adapting key Jain concepts such as nonviolence (ahiṃsā), but also many-sided view and truth telling, to ethical dilemmas in non-Jain contexts, (2) balancing Jain sources of knowledge alongside other authoritative epistemes including clinical and legal guidelines, and (3) a privileged concern for the health of five-sensed humans and animals.

These concerns emerge from the unique Jain worldview, which is not adequately captured in previous studies that equate religion with theistic or worship-based communities. Rather, the Jain reflexive ethical orientation reflects a distinct value framework centered on the importance of avoiding harm in thought, speech, and action without proffering normative rules. Jain medical professionals strive to flexibly activate their identity as healthcare practitioners and Jains through myriad considerations, adjustments, and commitments. In light of the longstanding western commitment to the Hippocratic Oath and its exhortation to “First, do no harm”, the robust Jain commitment to nonviolence in medicine, and its flexible expressions in medical calculations, is a rich arena for further study in contextual medicine and multicultural healthcare.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rice University, Houston, TX (IRB-FY2017-485) 1 June 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data results can be seen in the book: Donaldson, Brianne and Ana Bajželj, Insistent Life: Principles for Bioethics in the Jain Tradition (University of California Press, 2021); available in online open access at https://luminosoa.org/site/books/m/10.1525/luminos.108/.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See especially Bajželj’s overview and original analysis of Jain primary texts in chapter four. |

| 2 | Personal email correspondence with Dr. Sanmati Thole, president of the Jain Medical Doctors Association of India, January 19, 2018. For these and other sources on current Jain medical demographics, see (Donaldson and Bajželj 2021, pp. 3–4). |

| 3 | The World Religions Database estimates the 2020 U.S. Jain population at 94,336, and of Canada at 16,130. JAINA states that it represents over 150,000 Jains in the U.S. and Canada (“JAINA in Action”). |

| 4 | Personal email correspondence with Dr. Manoj Jain, 21 December 2017. |

| 5 | The survey included questions related to demographics (17 questions), professional and religious identity (32 questions), ethical reflection (69 questions), and Jain religious education (12 questions). |

| 6 | The introductory video can be viewed online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tw9joiNJDkU&list=UUgZi8PYp1Mfa6p8dfgwCSiQ&index=3&t=0s (accessed on 21 March 2022). |

| 7 | For a full breakdown of sectarian identity of survey participants, see (Donaldson and Bajželj 2021, p. 111). |

| 8 | The secondary research questions included: (1) Does the Jain tradition influence the kind of profession one takes? (2) What is the relationship between Jain knowledge and modern scientific knowledge? (3) Does the Jain tradition assist in arbitrating ethical dilemmas in a professional context? (4) What is the source of authoritative knowledge within the Jain tradition regarding one’s professional bioethical context? (5) What constitutes a “Jain lens” in a bioethical setting? and (6) Is Jain ethical problem solving inductive (working from concrete situation’s to abstract principles) or deductive (applying abstract principles to concrete situations). |

| 9 | Forsyth noted that his own work was influenced by an earlier conceptual study: Hogan’s Survey of Ethical Attitudes (1970), which was initially developed to interrogate specific aspect of Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development (1963). |

| 10 | The twenty questions are available at Donelson Forsyth’s personal website: https://donforsyth.wordpress.com/ethics/ethics-position-questionnaire/ (accessed on 24 March 2022). |

| 11 | See also Christopher Key Chapple (1993) for his use of the term “flexible fundamentalism” related to Jain practices. |

| 12 | See Sections 5.4 and 6. |

| 13 | “Compassion” is a technical concept in Jain texts; see (Wiley 2006). Consider compassion in relation to bioethics, see (Donaldson and Bajželj 2021), especially chapter three. |

| 14 | “Non-stealing” is the shorthand way of referring to the lay Jain vow of asteya. For mendicants, this vow is often described akin to “not taking what isn’t freely given”, referring to food alms and other basic needs that monks and nuns are provided by the laity. For lay Jains, this vow often takes on a sense of not cheating others in personal and professional contexts. |

| 15 | A related response includes, “A medical school professor once mocked me for not be willing to do experimental testing on animals.” |

| 16 | These responses include: “being vegetarian. People feel I don’t enjoy life!”; “being a vegetarian requires constant explanation”; and “being vegetarian”. |

| 17 | Nathmal Tatia, trans., That Which Is [Umāsvāti, Tattvārtha-sūtra] (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011): 2.8–2.25. |

| 18 | See also Qvarnström (2000) for an historical examination of how Jains adapted to non-Jain or rival environments within the subcontinent in times of social or political instability. |

| 19 | See (Williams 1991, p. 65). “The contention that it is better to kill one higher animal than to destroy a very great number of lower forms of life is refuted by the explanation that the carcass will inevitably be full of minute organisms called nigodas. For this reason perhaps, too, it is forbidden to kill oneself in order to offer one’s body as food for the starving.” |

| 20 | Other responses included, “Little to no violation of Jain principles” (73%, n = 37), or “I don’t know” (16%). |

References

- Ai, Amy L., Crystal L. Park, and Marshall Shearer. 2008. Spiritual and Religious Involvement Relate to End-of-life Decision-making In Patients Undergoing Coronary Bypass Graft Surgery. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine Affiliations 38: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Amy L., Paul Wink, Terrence N. Tice, Steven F. Bolling, and Marshall Shearer. 2009. Prayer and Reverence in Naturalistic, Aesthetic, and Socio-Moral Contexts Predicted Fewer Complications Following Coronary Artery Bypass. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32: 570–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allmon, Dean E., Diana Page, and Ralph Roberts. 2000. Determinants of Perceptions of Cheating: Ethical Orientation, Personality and Demographics. Journal of Business Ethics 23: 411–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandarajah, Gowri, and Ellen Hight. 2001. Spirituality and Medical Practice: Using the HOPE Questions as a Practical Tool for Spiritual Assessment. American Family Physician 63: 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Appleby, Alistair, Philip Wilson P., and John Swinton. 2018. Spiritual Care in General Practice: Rushing in or Fearing to Tread? An Integrative Review of Qualitative Literature. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 1108–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auckland, Knut. 2016. The Scientization and Academization of Jainism. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 84: 192–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, Tracy, Michael Balboni, M. Elizabeth Paulk, Andrea Phelps, Alexi Wright, John Peteet, Susan Block, Chris Lathan, Tyler Vanderweele, and Holly Prigerson. 2011. Support of Cancer Patients’ Spiritual Needs and Associations with Medical Care Costs at the End of Life. Cancer 117: 5383–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, Marcus. 1991. Orthodoxy and Dissent: Varieties of Religious Belief Among Immigrant Gujarati Jains in Britain. In The Assembly of Listeners: Jains in Society. Edited by Michael Carrithers and Caroline Humphrey. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 241–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baume, Peter, Emma O’Malley, and Adrian Bauman. 1995. Professed Religious Affiliation and the Practice of Euthanasia. Journal of Medical Ethics 21: 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollée, Willem B. 2003. Notes on Diseases in the Canon of the Śvetāmbara Jains. International Journal for Asian Studies 4: 163–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bothra, Shivani. 2018. Keeping the Tradition Alive: An Analysis of Contemporary Jain Religious Education for Children in India and North America. Ph.D. dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Bothra, Surendra. 2004. Ahimsa: The Science of Peace. Jaipur: Prakrit Bharati Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, J. Emilio, Alexander R. Green, and Joseph R. Betancourt. 1999. Cross-cultural Primary Care: A Patient-based Approach. Annals of Internal Medicine 130: 829–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, Christopher Key. 1993. Two Traditional Indian Models for Interreligious Dialogue: Monistic Accommodationism And Flexible Fundamentalism. Dialogue & Alliance 7: 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shiou-Yu, and Chung-Chu Liu. 2009. Relationships between personal religious orientation and ethical ideologies. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 37: 313–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yuh-Jia, and Thomas Li-Ping Tang. 2013. The Bright and Dark Sides of Religiosity Among University Students: Do Gender, College Major, and Income Matter? Journal Business Ethics 115: 531–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, Nicholas A., and David A. Asch. 1995. Physician Characteristics Associated with Decisions to Withdraw Life Support. American Journal of Public Health 85: 367–72. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Declaration. 2019. JAINA. Available online: https://www.jaina.org/page/ClimateDeclaration (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Cort, John. 2002. Green Jainism? Notes and Queries toward a Possible Jain Environmental Ethic. In Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life. Edited by Christopher Key Chapple. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Craigie, Frederic C., Jr., David B. Larson, Ingrid Y. Liu, and J. S. Lyons. 1988. A Systematic Analysis of Religious Variables in The Journal of Family Practice, 1976–1986. The Journal of Family Practice 27: 509–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crawley, Lavera M., Patricia A. Marshall, Bernard Lo, and Barbara A. Koenig. 2002. Strategies for Culturally Effective End-of-Life Care. Annals of Internal Medicine 136: 673–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curlin, Farr A., John D. Lantos, Chad J. Roach, Sarah A. Sellergren, and Marshall H. Chin. 2005. Religious Characteristics of U.S. Physicians: A National Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20: 629–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curlin, Farr A., Marshall H. Chin, Sarah A. Sellergren, Chad J. Roach, and John D. Lantos. 2006. The Association of Physicians’ Religious Characteristics with Their Attitudes and Self-reported Behaviors Regarding Religion and Spirituality in the Clinical Encounter. Medical Care 44: 446–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daaleman, Timothy P., and Bruce Frey. 1999. Spiritual and Religious Beliefs and Practices of Family Physicians: A National Survey. The Journal of Family Practice 48: 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva, Viruli A., Henarath H. D. P. Opatha, and Aruna Gamage. 2018. Does Ethical Orientation of HRM Impact on Employee Ethical Attitude and Behavior? Evidence from Sri Lankan Commercial Banks. International Business Research 11: 217–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Donaldson, Brianne. 2019a. Transmitting Jainism in U.S. Pāṭhaśāla Temple Education Part 1: Implicit Goals, Curriculum as ‘Text,’ and Authority of Teachers, Family, and Self. Transnational Asia 2: 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, Brianne. 2019b. Transmitting Jainism in U.S. Pāṭhaśāla Temple Education Part 2: Navigating Non-Jain Contexts, Cultivating Identity Markers and Networks, and Analyzing Truth Claims. Transnational Asia 2: 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, Brianne. 2022. The Hunter, the Bow, and the Arrow: The Development of Intentional Harm as Kriyā in the Early Jaina Canon. In (Non-)Violence in Jaina Philosophy, Literature and Art. Edited by Peter Flügel. New Delhi: Dev Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, Brianne, and Ana Bajželj. 2021. Insistent Life: Principles for Bioethics in the Jain Tradition. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Patricia Casey, Ronald A. Davidson, and Bill N. Schwartz. 2001. The Effect of Organizational Culture and Ethical Orientation on Accountants’ Ethical Judgments. Journal of Business Ethics 34: 101–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukas, David J., David Waterhouse, Daniel W. Gorenflo, and Jerome Seid. 1995. Attitudes and Behaviors on Physician-assisted Death: A Study of Michigan Oncologists. Journal of Clinical Oncology 13: 1055–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dundas, Paul. 2002a. The Jains, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dundas, Paul. 2002b. The Limits of a Jain Environmental Ethic. In Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life. Edited by Christopher Key Chapple. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, Jacqueline K., Kevin L. Eastman, and Michael A. Tolson. 2001. The Relationship between Ethical Ideology and Ethical Behavior Intentions: An Exploratory Look at Physicians’ Responses to Managed Care Dilemmas. Journal of Business Ethics 31: 209–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, Mark R., James D. Campbell, Ann Detwiler-Breidenbach, and Dena K Hubbard. 2002. What Do Family Physicians Think About Spirituality in Clinical Practice? The Journal of Family Practice 51: 249–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Emanuel, Ezekial J., and Linda L. Emanuel. 1992. Four Models of the Physician–patient Relationship. JAMA 267: 2221–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernecoff, Natalie C., Farr A. Curlin, Praewpannarai Buddadhumaruk, and Douglas B. White. 2015. Health Care Professionals’ Responses to Religious or Spiritual Statements by Surrogate Decision Makers During Goals-of-Care Discussions. JAMA Internal Medicine 175: 1662–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsyth, Donelson R. 1980. A Taxonomy of Ethical Ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 39: 175–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, Donelson R., and Rick E. Berger. 1982. The Effects of Ethical Ideology on Moral Behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology 117: 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, John, Dave B. Larson, and George D. Allen. 1991. Religious Commitment and Mental Health: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Journal of Psychology and Theology 19: 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 1998a. Cures and Karma: Attitudes Towards Healing in Medieval Jainism. In Self, Soul and Body in Religious Experience. Edited by Albert I. Baumgarten, Jan Assman and Gedaliahu G. Stroumsa. Leiden and Boston: E. J. Brill, vol. 78, pp. 218–56. [Google Scholar]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 1998b. Cures and Karma II: Some Miraculous Healings in the Indian Buddhist Story Tradition. Bulletin de l’Ecole Francaise d’Extrême-Orient 85: 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 2014. Between Monk and Layman: Paścātkṛta and the Care of the Sick in Jain Monastic Rules. In Buddhist and Jaina Studies: Proceedings of the Conference in Lumbini. Edited by Jayandra Soni, Michael Pahlke and Christoph Cüppers. Lumbini: Lumbini International Research Institute, pp. 229–53. [Google Scholar]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 2017. Patience and Patients: Jain Rules for Tending the Sick. eJournal of Indian Medicine 9: 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, A. C., Jr., Carolyn Strand Norman, and Benson Wier. 2008. The Effect of Ethical Orientation and Professional Commitment on Earnings Management Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics 83: 419–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjistavropoulos, Thomas, David C. Malloy, Donald Sharpe, and Shannon Fuchs-Lacelle. 2003. The Ethical Ideologies of Psychologists and Physicians: A Preliminary Comparison. Ethics & Behavior 13: 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Daniel E., and Farr Curlin. 2004. Can Physicians’ Care Be Neutral Regarding Religion? Academic Medicine 79: 677–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handzo, George, and Harold G. Koenig. 2004. Spiritual Care: Whose Job Is It Anyway? Southern Medical Journal 97: 1242–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmy, Herlina. 2018. The Influence of Ethical Orientation, Gender, and Religiosity on Ethical Judgment Accounting Students. Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research 57: 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hordern, Joshua. 2016. Religion and Culture. Medicine 44: 589–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, Shelby D., and Scott Vitell. 1986. A General Theory of Marketing Ethics. Journal of Macromarketing 6: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Yogendra. 2007. Jain Way of Life: A Guide to Compassionate, Healthy and Happy Living. Fremont: Jaina Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. 2001. The Jaina Path of Purification. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. First published 1979. [Google Scholar]

- JAINA Education Committee. n.d. Jainism: Know It, Understand It & Internalize It. Available online: Jainism-says.blogspot.com (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Jim, Heather S. L., James E. Pustejovsky, Crystal L. Park, Suzanne C. Danhauer, Allen C. Sherman, George Fitchett, Thomas V. Merluzzi, Alexis R. Munoz, Login George, Mallory A. Snyder, and et al. 2015. Religion, Spirituality, and Physical Health in Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Cancer 121: 3760–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, William J. 1995. Harmless Souls: Karmic Bondage and Religious Change in Early Jainism with Special Reference to Umāsvāti and Kundakunda. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Todd M., and Brian J. Grim, eds. 2022. World Religion Database. Boston: Brill. Available online: https://www.worldreligiondatabase.org/wrd/#/homepage/wrd-main-page (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Kagawa-Singer, Marjorie, and Leslie J. Blackhall. 2001. Negotiating Cross-cultural Issues at the End of Life: “You Got to Go Where He Lives”. JAMA 286: 2993–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Dana E., and Bruce Bushwick. 1994. Beliefs and Attitudes of Hospital Inpatients about Faith Healing and Prayer. Journal of Family Practice 39: 349–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, Eric G., and Susan L. Kirby. 2015. Ethical Orientation and Competitiveness: Competitiveness and the Impact of Ethical Orientation. Journal of Strategic Management Education 11: 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G., Lucille B. Bearon, and Richard Dayringer. 1989. Physician Perspectives on the Role of Religion in the Physician-Older Patient Relationship. The Journal of Family Practice 28: 441–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G., Linda K. George, and Patricia Titus. 2004. Religion, Spirituality, and Health in Medically Ill Hospitalized Older Patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52: 554–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, Margot E., Gwen Wyatt, and J. C. Kurtz. 1995. Psychological and Sexual Well-being, Philosophical/spiritual Views, and Health Habits of Long-term Cancer Survivors. Health Care for Women International 6: 253–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, James. 1995. Riches and Renunciation: Religion, Economy, and Society Among the Jains. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, Raymond J. 2002. The Witches’ Brew of Spirituality and Medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24: 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laws, Charlotte. 2006. Jains, the ALF, and the EFF: Antagonists or Allies? In Igniting a Revolution: Voices in Defense of the Earth. Edited by Steven Best and Anthony J. Nocella, II. Oakland: AK Press, pp. 143–55. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, Charlotte. 2011. The Jain Center of Southern California: Theory and Practice Across Continents. In Call to Compassion: Religious Perspectives on Animal Advocacy. Edited by Lisa Kemmerer and Anthony J. Nocella, II. New York: Lantern Books, pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Jeffrey S., and Harold Y. Vanderpool. 1987. Is Frequent Religious Attendance Really Conducive to Better Health? Toward an Epidemiology of Religion. Social Science and Medicine 24: 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckhaupt, Sara E., Michael S. Yi, Caroline V. Mueller, Joseph M. Mrus, Amy H. Peterman, Christina M. Puchalski, and Joel Tsevat. 2005. Beliefs of Primary Care Residents Regarding Spirituality and Religion in Clinical Encounters with Patients: A Study at a Midwestern U.S. Teaching Institution. Academic Medicine 80: 560–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzadis, Rebecca A., and Megan W. Gerhardt. 2012. An Exploration of the Relationship Between Ethical Orientation and Goal Orientation. Journal of Academic and Business Ethics 5: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Malloy, David C., Phillip R. Sevigny, Thomas Hadjistavropoulos, Kevin Bond, Elizabeth Fahey McCarthy, Masaaki Murakami, Suchat Paholpak, N. Shalini, P. L. Liu, and H. Peng. 2014. Religiosity and Ethical Ideology of Physicians: A Cross-Cultural Study. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 244–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, Thomas R., Faith Hopp, Holly Nelson-Becker, Amy Ai, Judith O. Schlueter, and Jessica K. Camp. 2012. Ethical and Spiritual Concerns Near the End of Life. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging 24: 301–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickley, Jacqueline Ruth, Karen Soeken, and Anne Belcher. 1992. Spiritual Well-Being, Religiousness and Hope Among Women With Breast Cancer. The Journal of Nursing Scholarship 24: 267–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Christopher Jain, and Jonathan Dickstein. 2021. Jain Veganism: Ancient Wisdom, New Opportunities. Religions 12: 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, Michael H., Deborah Bynum, Beth Susi, Nancy Phifer, Linda Schultz, Mark Franco, Charles D. MacLean, Sam Cykert, and Joanne Garrett. 2003. Primary Care Physician Preferences Regarding Spiritual Behavior in Medical Practice. Archives of Internal Medicine 163: 2751–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Fallon, Michael J., and Kenneth D. Butterfield. 2005. A Review of the Empirical Ethical Decision-making Literature: 1996–2003. Journal of Business Ethics 59: 375–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, Kenneth E. 2004. Religion and Spirituality: Important Psychosocial Variables Frequently Ignored in Clinical Research. Southern Medical Journal 97: 1152–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Bregje D., Martien T. Muller, Gerrit van der Wal, Jacques van Eijk, and Miel W. Ribbe. 1995. Attitudes of Dutch General Practitioners and Nursing Home Physicians to Active Voluntary Euthanasia and Physician-assisted Suicide. Archives of Family Medicine 4: 951–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, Nalini Tarakeshwar, and June Hahn. 2001. Religious Struggle as a Predictor of Mortality Among Medically Ill Elderly Patients. Archives of Internal Medicine 161: 1881–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, Nalini Tarakeshwar, and June Hahn. 2004. Religious Coping Methods as Predictors of Psychological, Physical and Spiritual Outcomes among Medically Ill Elderly Patients: A Two-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Health Psychology 9: 713–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsall, Matthew J., and Aleksander P. J. Ellis. 2011. Thick as Thieves: The Effects of Ethical Orientation and Psychological Safety on Unethical Team Behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 401–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, Guillermo, Daniel J. Feaster, Seth J. Schwartz, Indira Abraham Pratt, Lila Smith, and Jose Szapocznik. 2004. Religious Involvement, Coping, Social Support, and Psychological Distress in HIV-seropositive African American Mothers. AIDS and Behavior 8: 221–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, Christina M. 2001a. Spirituality and Health: The Art of Compassionate Medicine. Hospital Physician, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski, Christina M. 2001b. The Role of Spirituality in Health Care. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 14: 352–57. [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski, Christina M., Betty Ferrell, Rose Virani, Shirley Otis-Green, Pamela Baird, Janet Bull, Harvey Chochinov, George Handzo, Holly Nelson-Becker, Maryjo Prince-Paul, and et al. 2009. Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care: The Report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine 12: 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qvarnström, Olle. 2000. Stability and Adaptability: A Jain Strategy for Survival and Growth. In Jain Doctrine and Practice: Academic Perspectives. Edited by Joseph T. O’Connell. Toronto: University of Toronto, pp. 113–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ringdal, Gerd Inger. 1996. Religiosity, Quality of Life, and Survival in Cancer Patients. Social Indicators Research 38: 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Kristin A., Meng-Ru Cheng, Patrick D. Hansen, and Richard J. Gray. 2017. Religious and Spiritual Beliefs of Physicians. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 205–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmoirago-Blotcher, Elena, George Fitchett, Katherine Leung, Gregory Volturo, Edwin Boudreaux, Sybil Crawford, Ira Ockene, and Farr Curlin. 2016. An Exploration of the Role of Religion/Spirituality in the Promotion of Physicians’ Wellbeing in Emergency Medicine. Preventative Medicine Reports 3: 189–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Terri A., Andrew D. Zechnich, Virginia P. Tilden, Melinda A. Lee, Linda Ganzini, Heidi D. Nelson, and Susan W. Tolle. 1996. Oregon Emergency Physicians’ Experiences With, Attitudes Toward, and Concerns about Physician-assisted Suicide. Academic Emergency Medicine 3: 938–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, Sabine. 2012. ‘The Jain Way of Life’: Modern Re-Use and Reinterpretation of Ancient Jain Concepts. In Re-Use: The Art and Politics of Integration and Anxiety. Edited by Julia A. B. Hegewald and Subrata K. Mitra. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, pp. 273–87. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Bindi V. 2014. Religion in the Everyday Lives of Second-Generation Jains in Britain and the USA: Resources Offered by a Dharma-Based South Asian Religion for the Construction of Religious Biographies, and Negotiating Risk and Uncertainty in Late Modern Societies. The Sociological Review 62: 512–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Bindi V. 2017. Religion, Ethnicity, and Citizenship: The Role of Jain Institutions in the Social Incorporation of Young Jains in Britain and the United States. Journal of Contemporary Religion 32: 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, Allen C., Thomas G. Plante, Stephanie Simonton, Umaira Latif, and Elias J. Anaissie. 2009. Prospective Study of Religious Coping Among Patients Undergoing Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32: 118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, KyuJin, Myojung Chung, and Young Kim. 2017. Does Ethical Orientation Matter? Determinants of Public Reaction to CSR Communication. Public Relations Review 43: 817–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikdar, Jogendra Chandra. 1964. Studies in The Bhagawatīsūtra. Muzaffarpur: Research Institute of Prakrit, Jainology & Ahimsa. [Google Scholar]

- Sikdar, Jogendra Chandra. 1975. The World of Life According to the Jaina Literature. Sambodhi 4: 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Struve, James K. 2002. Faith’s Impact on Health. Implications for the Practice of Medicine. Minnesota Medicine Magazine 85: 41–4. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, Mari J. 2014. Mendicants and Medicine: Āyurveda in Jain Monastic Texts. History of Science in South Asia 2: 63–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmasy, Daniel P. 2009. Spirituality, Religion, and Clinical Care. Chest 135: 1634–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuminello, Joseph A., III. 2019. Jainism: Animals and the Ethics of Intervention. In The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Animal Ethics. Edited by Andrew Linzey and Clair Linzey. New York: Routledge, pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Vallely, Anne. 2006. From Liberation to Ecology: Ethical Discourses among Orthodox and Diaspora Jains. In Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life. Edited by Christopher Key Chapple. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Vallely, Anne. 2018. Vulnerability, Transcendence, and the Body: Exploring the Human/Nonhuman Animals Divide Within Jainism. Society and Animals 26: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, Neil S., and Sara Carmel. 2004. Physicians’ Religiosity and End-of-life Care Attitudes and Behaviors. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 71: 335–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wiley, Kristi. 2006. Ahiṃsā and Compassion in Jainism. In Studies in Jaina History and Culture: Disputes and Dialogues. Edited by Peter Flügel. New York: Routledge, pp. 438–55. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Robert. 1991. Jaina Yoga: A Survey of the Mediaeval Śrāvakācāras. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).