Meeting of Cultures and Architectural Dialogue: The Example of the Dominicans in Taiwan

Abstract

:1. The Flow of History and the Locus of an Encounter

2. Historical Background

3. Meeting of Cultures: Interpretation, and Alterity

4. A Dialogue between Cultures

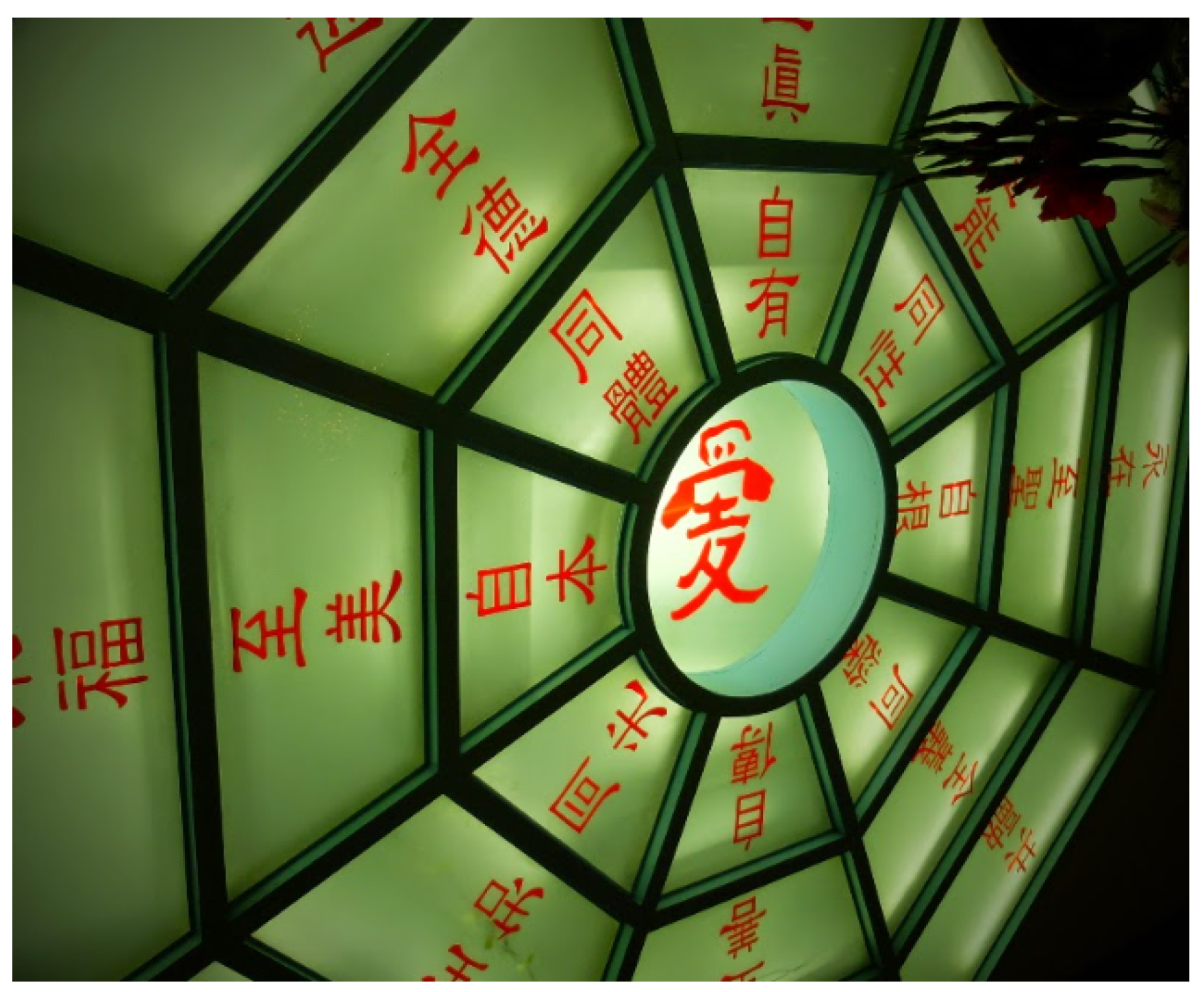

4.1. Architecture as the Locus of Dialogue

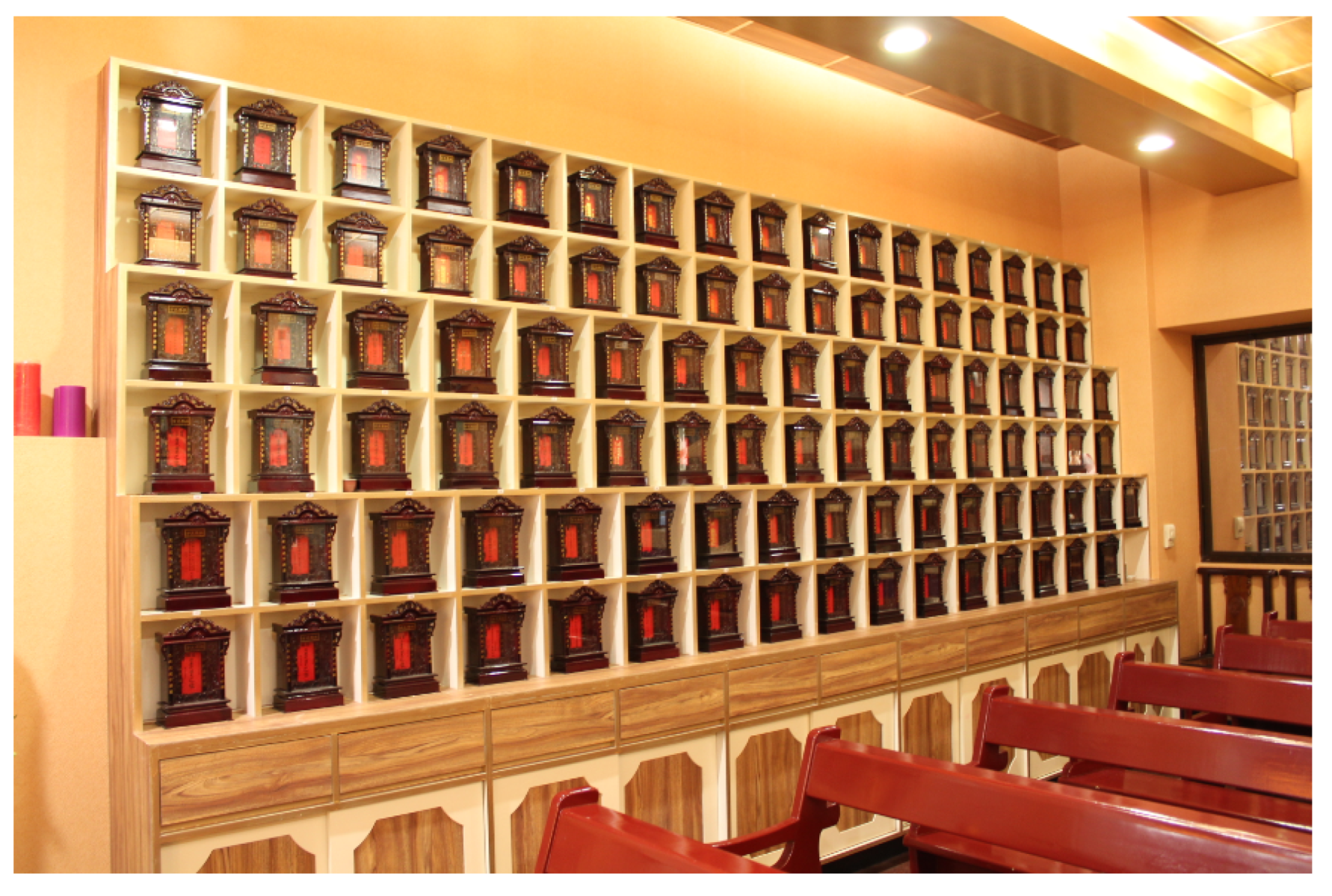

4.2. Private Architecture

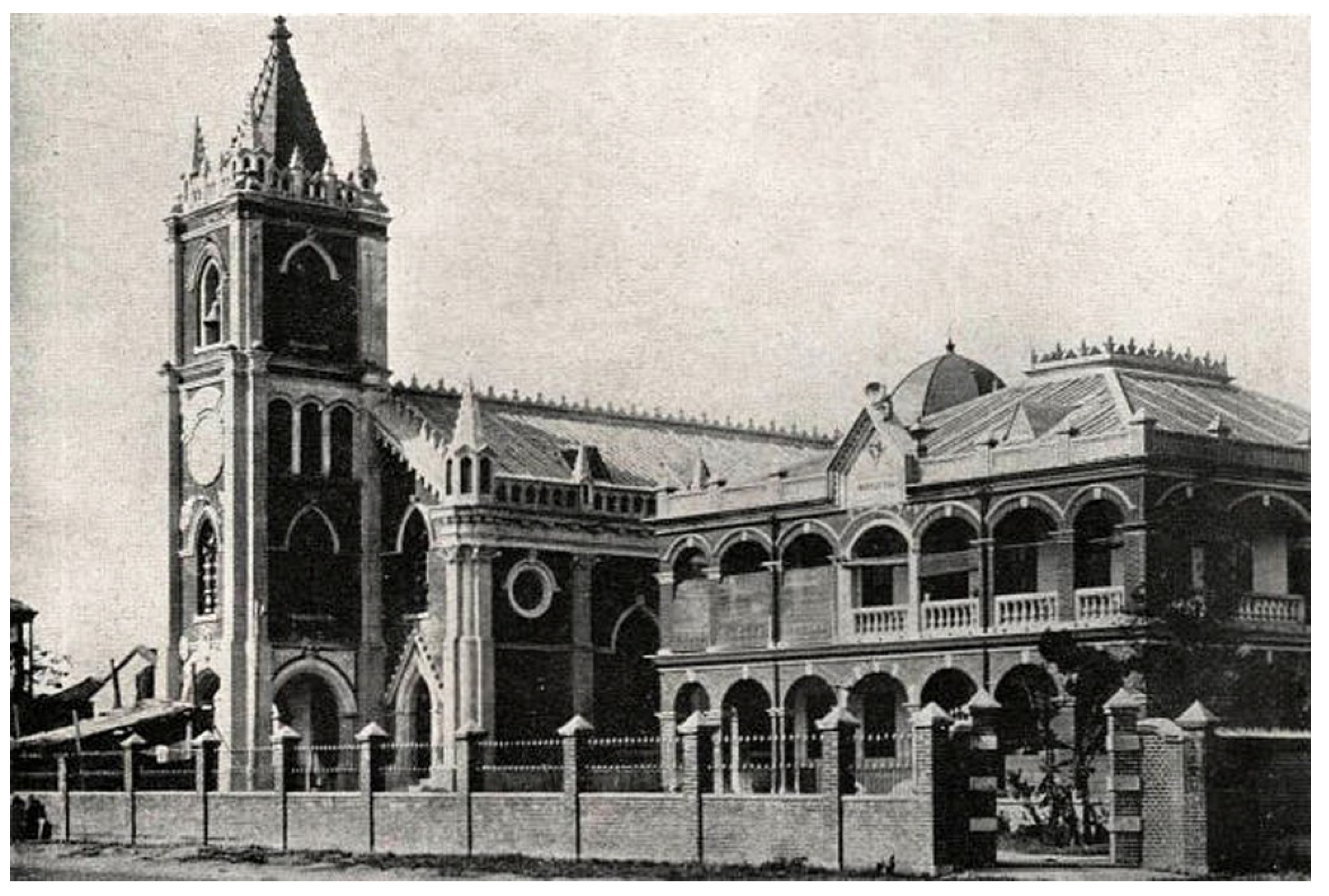

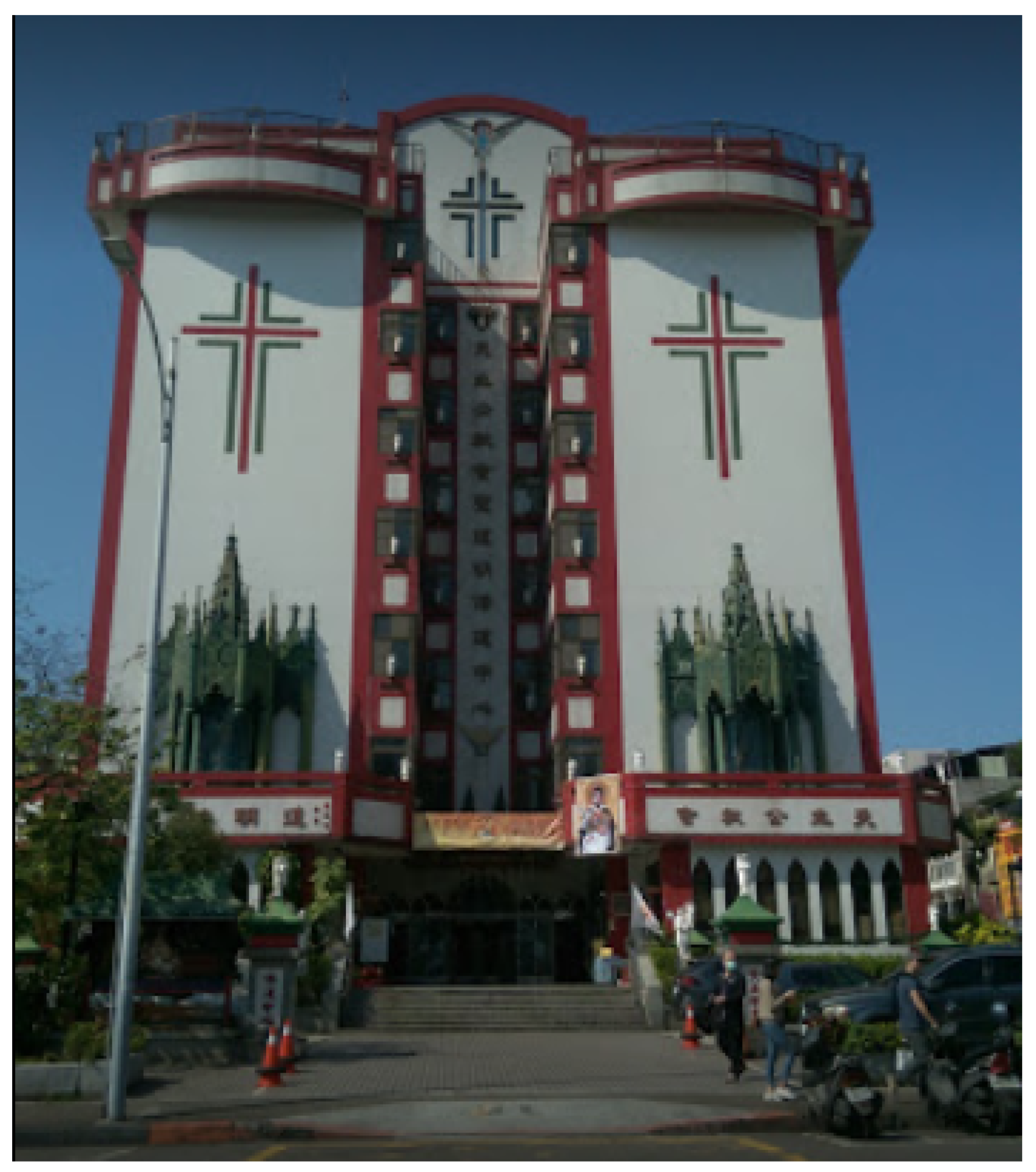

4.3. Public Architecture

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The exact place where the incident occurred is not precisely known but, according to the account of that time, his ship ran aground in Taiwan «in such a way, that few people were able to reach the coast, yet they did so after a great effort. They arrived there without weapons and the barbarians appeared, killing most of them. Among those who were killed was Fr. Juan Cobo. His death was reported in the Philippines in 1595 by the natives of the Philippines and China who escaped from the cruelty of those from Isla Hermosa.» (Santamaría 1986) |

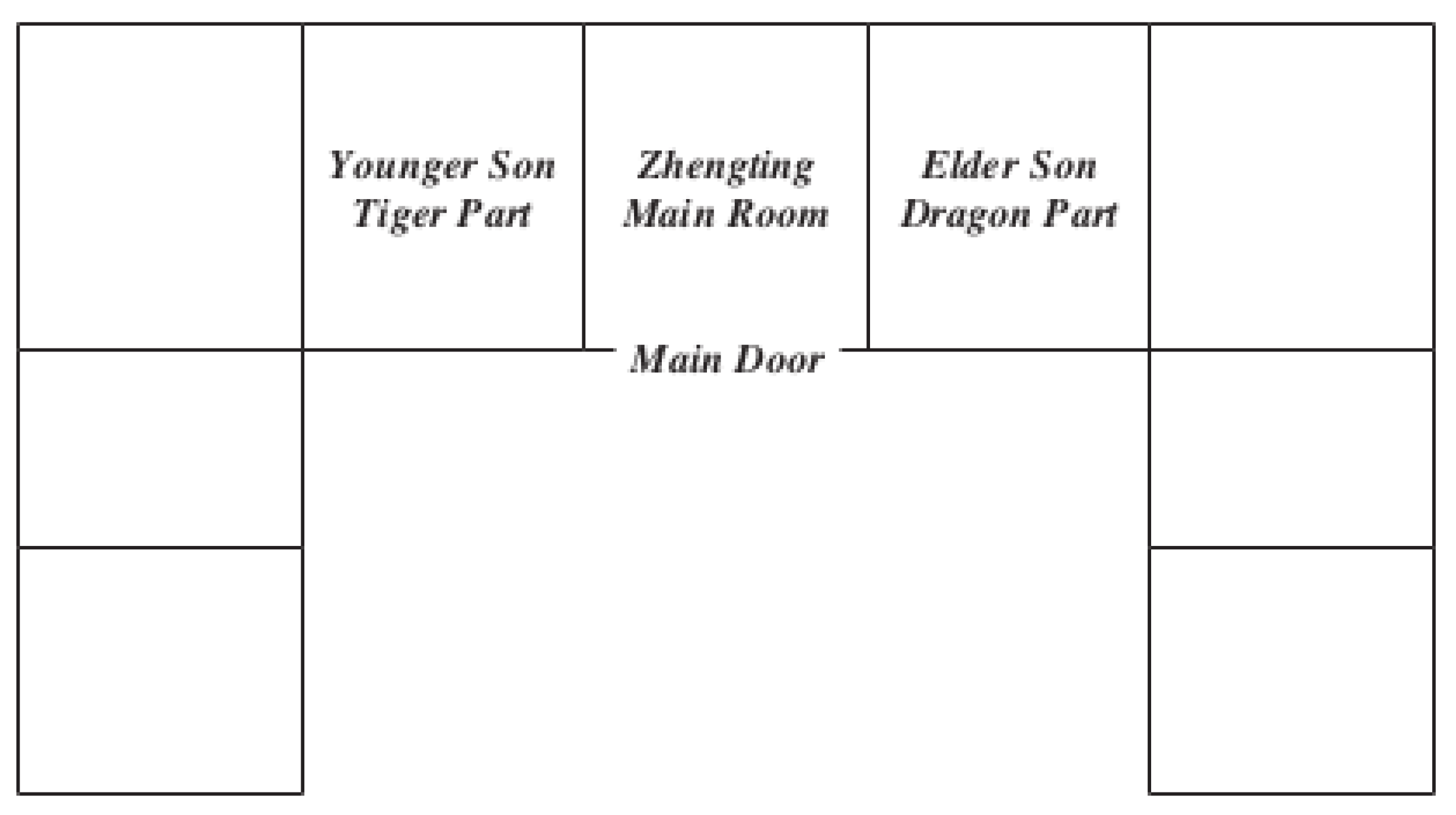

| 2 | According to the Chinese usage, the right and left parts are considered according the perspective of a man standing with his back to the front of the house. |

| 3 | This sentence comes from the very origin of Catholicism in China. It refers to the year 1775 in which the Beijing cathedral built by Jesuits was damaged by fire, and 乾隆帝 the Emperor Qianlong donated 10,000 teals of silver for the restoration work and also bestowed a board with calligraphy made from the Emperor’s own hand, inscribed with the above-mentioned characters 萬有真原 on it, meaning “The true origin of all things”. |

| 4 | First, the world of the Bible presents us with a new image of God. In surrounding cultures, the image of God and of the gods ultimately remained unclear and contradictory. In the development of biblical faith, however, the content of the prayer fundamental to Israel, the Shema, became increasingly clear and unequivocal: “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is one Lord” (Dt 6:4). There is only one God, the Creator of heaven and earth, who is thus the God of all. Two facts are significant about this statement: all other gods are not God, and the universe in which we live has its source in God and was created by him. Certainly, the notion of creation is found elsewhere, yet only here does it become absolutely clear that it is not one god among many, but the one true God himself who is the source of all that exists; the whole world comes into existence by the power of his creative Word. Consequently, his creation is dear to him, for it was willed by him and “made” by him. The second important element now emerges: this God loves man. The divine power that Aristotle at the height of Greek philosophy sought to grasp through reflection, is indeed for every being an object of desire and of love—and as the object of love this divinity moves the world (Benedict 2005) —but in itself it lacks nothing and does not love: it is solely the object of love. The one God in whom Israel believes, on the other hand, loves with a personal love. His love, moreover, is an elective love: among all the nations he chooses Israel and loves her—but he does so precisely with a view to healing the whole human race (Benedict 2005). |

References

- Andrade, Tonio. 2010. How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish, and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. ACLS Humanities E-Book Electronic Edition. New York: Columbia University Press, OCLC: 1241672819. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict, XVI. 2005. Deus Caritas Est. Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Borao Mateo, José Eugenio. 2009a. The Dominican Missionaries in Taiwan (1626–1642). In Missionary Approaches and Linguistics in Mainland China and Taiwan. Edited by Ferdinand Verbiest Foundation and Wei-Ying Ku. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 101–33. [Google Scholar]

- Borao Mateo, José Eugenio. 2009b. Dominicos Españoles en Taiwan (1859–1960): Primer Siglo de Historia de la Iglesia Católica en la Isla. Encuentros en Catay 23: 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bresciani, Umberto. 2006. The Future of Christianity in China. Quaderni del Centro Studi Asiatico 1: 101–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Dy Aristotle S. J. 2000. Weaving a Dream: Reflections for Chinese-Filipino Catholics Today. Quezon City: Jesuit Communications, OCLC: 46643937. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I-Chun 陳怡君. 2011. The Evocation of Religious Experiences and the Reformulation of Ancestral Memories: Memory, Ritual, and Identity among Bankim Catholics in Taiwan 宗教經驗的召喚與祖先記憶的重塑:屏東萬金天主教徒的記憶、儀式與認同. Ph.D. thesis, National Taiwan University 國立臺灣大學, Taipei, Taiwan, January. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comaroff, Jean, and John L. Comaroff. 2008. Of Revelation and Revolution, Volume 1: Christianity, Colonialism, and Consciousness in South Africa. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, Google-Books-ID: M_RaDwAAQBAJ. [Google Scholar]

- Comaroff, John L., and Jean Comaroff. 2009. Of Revelation and Revolution, Volume 2: The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, February, Google-Books-ID: hE_Jr49HJW0C. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Pablo. 1994. One Hundred Years of Dominican Apostolate in Formosa, 1859–1958: Extracts from the Sino-Annamite Letters. Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc, Open Library ID: OL31649977M. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Pablo Emilio. 1958. Dominicos donde nace el sol: Historia de la Provincia del Santísimo Rosario de Filipinas de la orden de predicadores. Barcellona: Gregorio, Google-Books-ID: S8EAAAAAMAAJ. [Google Scholar]

- Feuchtwang, Stephan. 2016. Chinese Religion. In Religions in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations. Edited by Linda Woodhead, Christopher Partridge and Hiroko Kawanami. London: Routledge, Google-Books-ID: CaFeCwAAQBAJ. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973a. Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973b. Religion as a Cultural System. In The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books, pp. 87–125, OCLC: 737285. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973c. Time, Person and Conduct in Bali. In The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books, pp. 360–411, OCLC: 737285. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1980. Negara. Princeton: Princeton University Press, Google-Books-ID: QSUpCecTugkC. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, Wei-Ying 古偉瀛. 2000. Conflicts, Confusion and Control: Some Observations on Missionary Cases. In Footsteps in Deserted Valleys: Missionary Cases, Strategies and Practice in Qing China. Edited by Koen De Ridder. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 11–38, Google-Books-ID: 9r6bPTNQ4LUC. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarotti, Marco. 2013. How the Universal Becomes Domestic: An Anthropological Case Study of the Shuiwei Village, Taiwan. In The Household of God and Local Households: Revisiting the Domestic Church. Edited by Thomas Knieps-Port Le Roi and Gerard Mannion-Peter De Mey. Number 254 in Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium (BETL). Louvein: Peeters Publishers, pp. 301–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarotti, Marco. 2020. Place, Alterity and Narration in a Taiwanese Catholic Village. Asian Christianity in the Diaspora. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarotti, Marco 李克. 2008. The Ancestors’ Rites in the Taiwanese Catholic Church 臺灣天主教的祖先敬拜禮儀. Master’s thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, September Accepted: 2021–06–15T00:48:53Z. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Ruowen 李若文. 1997. A Review and Prospects of the Late Qing Teaching Case Study. 晚清教案研究的回顧與展望. In Secretariat of the Fourth Symposium on the History of the Republic of China 中華民國史專題論文集第四屆討論會秘書處. Taipei City 台北: Academia Historia Office 國史館, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhaoying. 2008. The East meets West in the art of the Taidong Aboriginal Church “Jinlun Catholic Church”. 臺東原住民教會藝術「金崙天主堂」所呈現東西文化差異與融合. In Challenges and Transitions in Anthropology 人類學的挑戰與跨越. Taipei City 台北: The Taiwan Society for Anthropology and Ethnology 臺灣人類學及民族學會主辦. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Maureen O. P. 2002. 101 Questions and Answers on Vatican II. Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlins, Marshall. 1985. Islands of History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Google-Books-ID: ScuTytmgE6MC. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría, Alberto O. P. 1986. Juan Cobo: Misionero y embajador. In Shih-Lu. Edited by Fidel Villarroel. Manila: University of Santo Tomás. [Google Scholar]

- Standaert, Nicolas. 2008. The Interweaving of Rituals: Funerals in the Cultural Exchange Between China and Europe. Washington, DC: University of Washington Press, Google-Books-ID: 9RLH18MQXGUC. [Google Scholar]

- Todorov, Tzvetan. 1999. The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Bühren, Ralf. 2008. Kunst und Kirche im 20. Jahrhundert: Die Rezeption des Zweiten Vatikanischen Konzils. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, Open Library ID: OL21172809M. [Google Scholar]

- van Bühren, Ralf. 2014. Architettura e arte al Concilio Vaticano II. In Nobile semplicità. Liturgia, arte e architettura del Vaticano II. Paper presented at the Atti dell’XI Convegno liturgico internazionale, Magnano, Italy, 30 May–1 June 2013 (Liturgia e vita). Edited by Goffredo Boselli. Magnano: Edizioni Qiqajon, pp. 141–78. [Google Scholar]

- Verbiest Study Note. 2004. Special Issue on the Catholic Church in Taiwan: 1626–1965. Taipei: China Program of the CICM SM Province, vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Sung-Hsing. 1974. Taiwanese architecture and the supernatural. In Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wee, Vivienne. 1976. ‘Buddhism’ in Singapore. In Singapore: Society in Transition. Edited by Riaz Hassan. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, pp. 155–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Jessica Y. 2002. Deadly Dreams: Opium and the Arrow War (1856–1860) in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Google-Books-ID: bJA6gvhGJdwC. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazzarotti, M. Meeting of Cultures and Architectural Dialogue: The Example of the Dominicans in Taiwan. Religions 2022, 13, 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111094

Lazzarotti M. Meeting of Cultures and Architectural Dialogue: The Example of the Dominicans in Taiwan. Religions. 2022; 13(11):1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111094

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazzarotti, Marco. 2022. "Meeting of Cultures and Architectural Dialogue: The Example of the Dominicans in Taiwan" Religions 13, no. 11: 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111094

APA StyleLazzarotti, M. (2022). Meeting of Cultures and Architectural Dialogue: The Example of the Dominicans in Taiwan. Religions, 13(11), 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111094