Explanation of the Trends and Recent Changes in Spanish Society Regarding Belief in God: Atheism, Agnosticism, Deism, Skepticism, and Belief

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Deism, Agnosticism, Atheism and Christianity

1.2. A Sociological Approach to Religious Counterpoints

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Comparative Analysis between 2008 and 2018

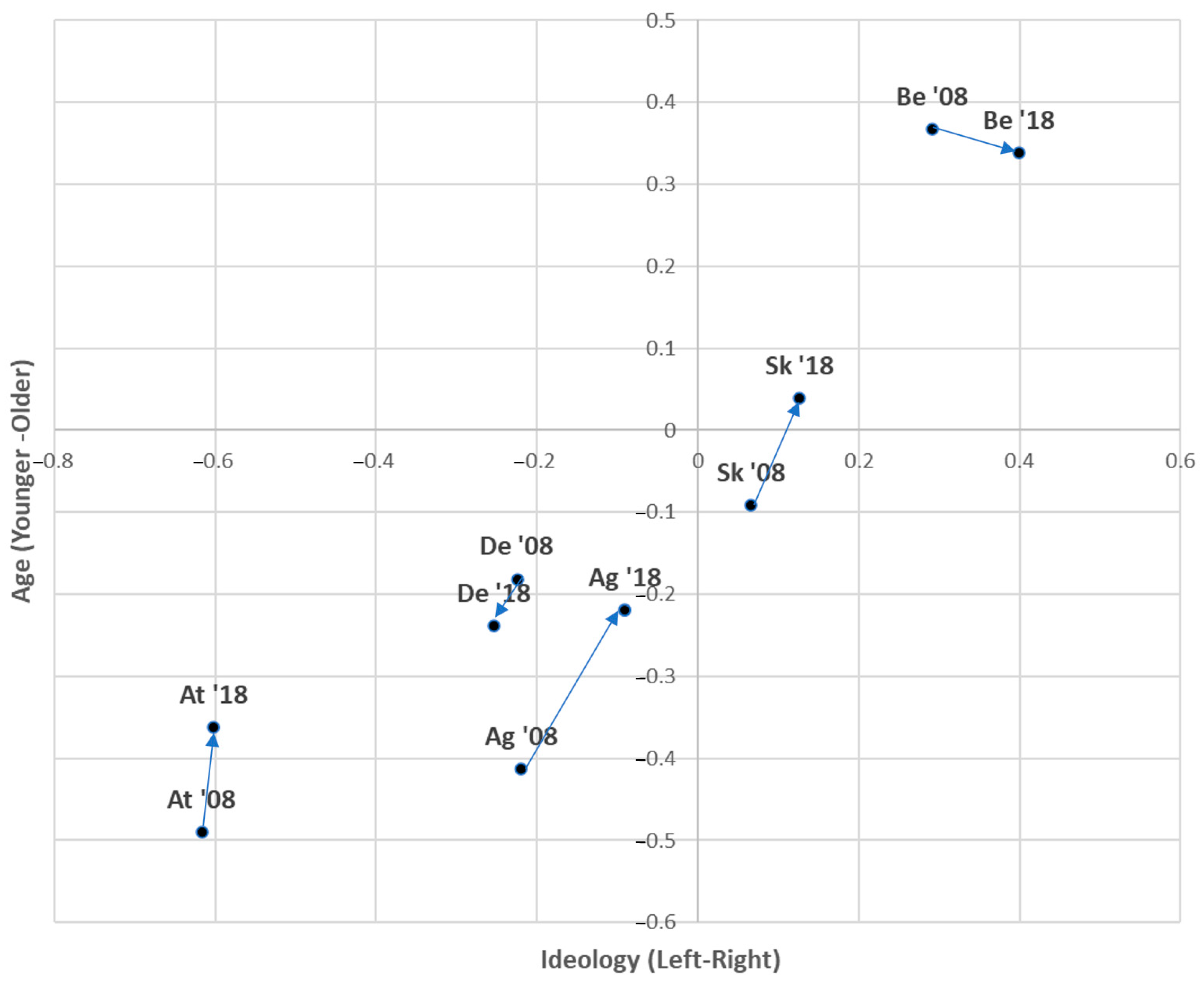

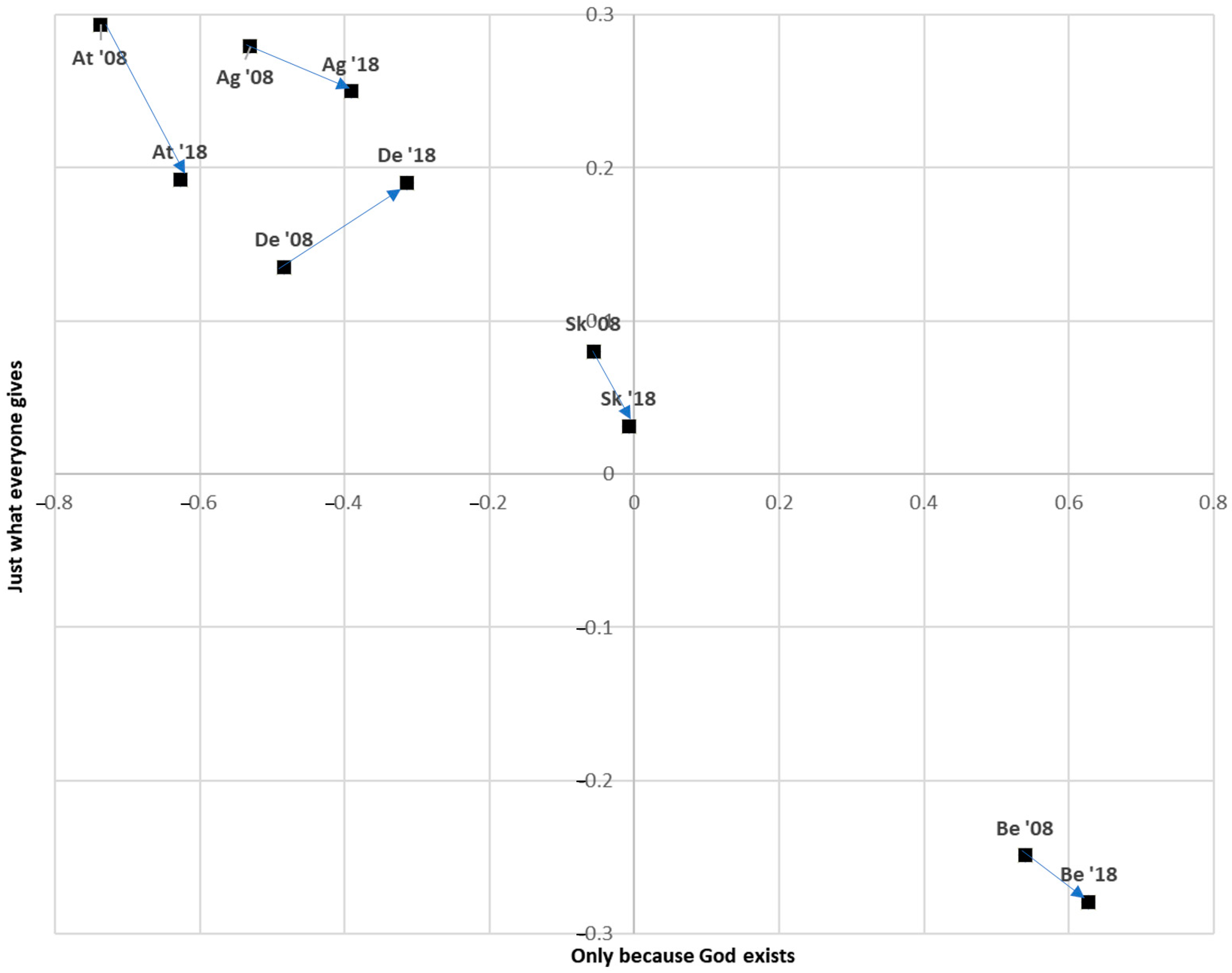

3.2. Explanatory and Comparative Analysis of 2008 and 2018

3.3. Some Trends

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Atheist | Agnostic | Deist | Skeptics/Believer | Believer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Men | 13.3 | 21.7 | 12.7 | 13.8 | 12.0 | 11.2 | 28.9 | 28.5 | 33.1 | 24.9 |

| Women | 6.3 | 12.3 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 29.0 | 30.1 | 44.3 | 36.3 |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 18–35 | 16.4 | 25.1 | 14.6 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 16.8 | 30.7 | 25.4 | 24.7 | 19.3 |

| 36–50 | 9.6 | 18.8 | 12.4 | 12.7 | 14.1 | 11.1 | 31.6 | 30.1 | 32.3 | 27.3 |

| 51–65 | 7.7 | 14.6 | 9.5 | 11.9 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 28.0 | 32.3 | 43.0 | 28.6 |

| 66–94 | 2.8 | 8.7 | 2.8 | 6.3 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 23.2 | 28.8 | 63.9 | 49.7 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| No education | 0.9 | 10.6 | 5.1 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 18.7 | 25.4 | 68.5 | 50.0 |

| Primary | 7.4 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 10.0 | 6.6 | 30.0 | 32.8 | 45.5 | 43.5 |

| Secondary | 14.8 | 17.7 | 13.1 | 12.2 | 14.1 | 10.2 | 31.5 | 26.2 | 26.5 | 33.7 |

| F. Vocational | 13.6 | 17.7 | 13.9 | 13.4 | 17.9 | 12.9 | 31.8 | 32.3 | 22.7 | 23.7 |

| Higher | 13.5 | 21.3 | 16.9 | 12.1 | 13.9 | 15.1 | 28.3 | 29.4 | 27.4 | 22.2 |

| Marital Status | ||||||||||

| Married | 6.6 | 13.5 | 9.9 | 10.6 | 12.3 | 9.7 | 30.0 | 32.1 | 41.2 | 34.1 |

| Widowed | 1.5 | 19.0 | 4.1 | 19.0 | 4.1 | 14.3 | 25.0 | 33.3 | 65.3 | 14.3 |

| Divorced | 5.9 | 18.6 | 7.4 | 5.8 | 14.7 | 18.6 | 36.8 | 29.1 | 35.3 | 27.9 |

| Separated | 16.9 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 15.3 | 7.5 | 25.4 | 28.0 | 37.3 | 52.3 |

| Single | 19.7 | 25.3 | 14.7 | 14.7 | 13.4 | 16.0 | 26.9 | 25.0 | 25.3 | 19.2 |

| Political Ideology | ||||||||||

| Left | 18.6 | 31.3 | 13.2 | 13.6 | 15.4 | 15.5 | 28.2 | 21.2 | 24.7 | 18.4 |

| Centre | 7.2 | 11.0 | 13.1 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 31.6 | 37.4 | 35.9 | 27.3 |

| Right | 3.0 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 10.6 | 8.3 | 4.3 | 30.3 | 29.5 | 51.5 | 48.8 |

| Status (social class) | ||||||||||

| Upper/upper middle | 14.5 | 22.4 | 16.2 | 13.8 | 15.1 | 14.1 | 28.2 | 30.0 | 26.0 | 19.7 |

| New middle | 10.0 | 14.4 | 10.9 | 9.7 | 14.6 | 16.4 | 33.9 | 32.1 | 30.5 | 27.4 |

| Old middle | 7.7 | 15.3 | 9.4 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 27.6 | 24.7 | 46.1 | 39.5 |

| Skilled workers | 12.0 | 19.2 | 10.6 | 11.1 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 28.7 | 30.3 | 37.9 | 29.2 |

| Unskilled workers | 7.0 | 12.7 | 6.4 | 11.9 | 14.0 | 7.1 | 26.8 | 28.2 | 45.8 | 40.1 |

| Total | 9.8 | 17.0 | 10.5 | 11.3 | 12.1 | 11.8 | 28.9 | 29.3 | 38.8 | 30.6 |

| Atheist | Agnostic | Deist | Skeptics/Believer | Believer | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Men | 67.2 | 63.4 | 59.8 | 60.3 | 48.9 | 47.0 | 49.1 | 48.2 | 42.0 | 40.3 | 49.2 | 49.6 |

| Women | 32.8 | 36.6 | 40.2 | 39.7 | 51.1 | 53.0 | 50.9 | 51.8 | 58.0 | 59.7 | 50.8 | 50.4 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 18–35 | 48.7 | 34.0 | 40.5 | 27.5 | 32.5 | 32.7 | 31.0 | 20.0 | 18.6 | 14.5 | 29.1 | 23.0 |

| 36–50 | 27.8 | 33.0 | 33.6 | 33.7 | 33.2 | 28.2 | 31.1 | 30.7 | 23.7 | 26.7 | 28.4 | 29.9 |

| 51–65 | 17.8 | 22.0 | 20.6 | 26.9 | 22.3 | 27.2 | 22.1 | 28.1 | 25.3 | 23.9 | 22.8 | 25.5 |

| 66–94 | 5.7 | 11.0 | 5.3 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 11.9 | 15.8 | 21.2 | 32.4 | 34.9 | 19.7 | 21.5 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education | 0.9 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 17.8 | 13.5 | 10.1 | 8.4 |

| Primary | 33.5 | 8.0 | 29.8 | 11.9 | 36.3 | 9.1 | 45.4 | 17.9 | 51.6 | 22.5 | 43.9 | 15.9 |

| Secondary | 19.4 | 24.6 | 15.9 | 25.4 | 14.9 | 20.8 | 13.9 | 21.1 | 8.7 | 25.8 | 12.8 | 23.6 |

| F. Vocational | 19.8 | 14.2 | 18.8 | 16.1 | 21.0 | 15.2 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 8.3 | 10.5 | 14.2 | 13.6 |

| Higher | 26.4 | 48.1 | 30.6 | 40.9 | 22.1 | 50.3 | 18.6 | 38.6 | 13.5 | 27.7 | 19.1 | 38.5 |

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| Married | 40.6 | 44.8 | 57.3 | 52.6 | 61.8 | 46.8 | 62.8 | 61.8 | 64.1 | 62.9 | 60.4 | 56.4 |

| Widowed | 1.3 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 6.0 | 14.1 | 10.7 | 8.4 | 6.3 |

| Divorced | 1.7 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 8.0 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 4.6 | 2.9 | 5.0 |

| Separated | 4.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| Single | 52.0 | 45.8 | 36.2 | 39.7 | 28.6 | 39.8 | 24.1 | 25.9 | 16.8 | 21.2 | 25.8 | 31.0 |

| Political Ideology | ||||||||||||

| Left | 73.1 | 63.3 | 49.5 | 39.3 | 53.1 | 44.6 | 41.0 | 24.8 | 30.4 | 23.8 | 43.3 | 35.5 |

| Center | 19.8 | 30.8 | 34.5 | 47.6 | 29.5 | 50.0 | 32.1 | 60.6 | 30.9 | 49.2 | 30.3 | 49.3 |

| Right | 7.1 | 5.8 | 16.0 | 13.1 | 17.4 | 5.4 | 26.9 | 14.7 | 38.7 | 27.0 | 26.4 | 15.2 |

| Status (social class) | ||||||||||||

| Upper/upper middle | 24.0 | 26.6 | 26.0 | 24.9 | 20.8 | 24.1 | 16.7 | 20.7 | 12.3 | 13.5 | 17.4 | 20.5 |

| New middle | 21.7 | 20.3 | 22.9 | 20.6 | 26.5 | 33.2 | 26.3 | 26.2 | 19.0 | 22.2 | 22.8 | 24.2 |

| Old middle | 12.7 | 11.5 | 15.0 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 10.6 | 16.3 | 10.8 | 21.7 | 17.2 | 17.3 | 12.9 |

| Skilled workers | 32.1 | 30.4 | 27.8 | 26.5 | 24.2 | 23.1 | 27.6 | 27.8 | 29.2 | 26.7 | 28.3 | 27.2 |

| Unskilled workers | 9.5 | 11.2 | 8.4 | 15.9 | 15.9 | 9.0 | 13.0 | 14.4 | 17.8 | 20.4 | 14.2 | 15.2 |

References

- Baggini, Julian. 2021. Atheism: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Michael H. 2003. In the Presence of Mystery: An Introduction to the of Human Religiousness. Mystic: Twenty-Third Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N. 2011. Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age. London: Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L. 2011. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Open Road Media. [Google Scholar]

- Bericat, Eduardo. 2008. Duda y posmodernidad: El ocaso de la secularización en Europa. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 211: 13–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2003. Politics and Religion. Oxford: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, John. 2019. On Religion, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, John D. 2021. John D. Caputo: The Collected Philosophical and Theological Papers: Volume 3. 1997–2000: The Return of Religion. Edited by Eric L. Weislogel. Lehi: John D. Caputo Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 2008. Selected Letters. Edited by Peter G. Walsh. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, William Kingdon. 1999. The ethics of belief. In The Ethics of Belief and Other Essays. Edited by Timothy J. Madigan. Buffalo: Prometheus, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Randall. 1992. Sociological Insight: An Introduction to Non-Obvious Sociology, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, Richard. 2008. The God Delusion. Boston: Mariner Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, Richard, Sam Harris, Daniel C. Dennett, and Christopher Hitchens. 2019. The Four Horsemen the Four Horsemen: The Discussion That Sparked an Atheist Revolution Foreword by Stephen Fry. London: Bantam Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demerath, N. Jay, III. 2000. The Rise of “Cultural Religion” in European Christianity: Learning from Poland, Northern Ireland, and Sweden. Social Compass 47: 127–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Emile. 2008. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eller, David. 2004. Natural Atheism. Cranford: American Atheist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Euler, Leonhard. 2018. Lettres à une Princesse d’Allemagne, sur Divers Sujets de Physique Et de Philosophie, Vol. 2. London: Forgotten Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Prados, Juan Sebastián, Cristina Cuenca-Piqueras, and María José González-Moreno. 2019. International Public Opinion Surveys and Public Policy in Southern European Democracies. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy 35: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, Paul, and Christopher Bader. 2008. Unraveling Religious Worldviews: The Relationship between Images of God and Political Ideology in a Cross-Cultural Analysis. The Sociological Quarterly 49: 689–718. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40220109 (accessed on 1 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Geertz, Clifford. 2017. The Interpretation of Cultures, 3rd ed. London: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 2017. Interaction Ritual: Essays in Face-to-Face Behavior. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 2022. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life the Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Holbach, Baron. 2014. The System of Nature: Or Laws of the Moral and Physical World. Whitefish: Literary Licensing. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, David. 2021. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. London: Independently Published. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, Thomas H. 2016. Agnosticism and Christianity. North Charleston: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, Thomas H. 2021. Collected Essays, (Volume V) Science and Christian Tradition: Essays. Hamburg: Tredition Classics. [Google Scholar]

- ISSP Research Group. 2018. International Social Survey Programme: Religion III—ISSP 2008. Mannheim: GESIS Data Archive. [Google Scholar]

- ISSP Research Group. 2020. International Social Survey Programme: Religion IV—ISSP 2018. Mannheim: GESIS Data Archive. [Google Scholar]

- Itçaina, Xabier. 2019. The Spanish Catholic Church, the Public Sphere, and the Economic Recession: Rival Legitimacies? Journal of Contemporary Religion 34: 153–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, William. 2014. The Will to Believe: And Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joas, Hans, and Klaus Wiegandt, eds. 2009. Secularization and the World Religions. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Gordon D. 2009. Jesus and Creativity. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Le Poidevin, Robin. 2010. Agnosticism: A Very Short Introduction: A Very Short Introduction. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Llopis, Ramón. 2002. Los españoles ante la religión: Una tipología sociológica. In Religión, Religiones, Identidad, Identidades, Minorías. Edited by Francisco Américo. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid, pp. 223–50. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Michael. 2006. The Cambridge Companion to Atheism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 2015a. Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. North Charleston: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 2015b. The German Ideology. Scotts Valley: Createspace. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, John Stuart. 2019. Three Essays on Religion. Norderstedt: Hansebooks. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, John Stuart. 2020. Autobiography. New York: Bibliotech Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, José Ramón. 1986. Iglesia, secularización y comportamiento político en España. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 34: 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2012. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2015. Are high levels of existential security conducive to secularization? A response to our critics. In The Changing World Religion Map. Edited by Stanley D. Brunn. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 3389–408. [Google Scholar]

- Oppy, Graham. 2009. Arguing about Gods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pascal, Blaise. 2019. Thoughts of Blaise Pascal. Sligo: HardPress. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Agote, Alfonso. 2010a. La irreligión de la Juventud española. Revista de Estudios de Juventud 91: 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Agote, Alfonso. 2010b. Religious change in Spain. Social Compass 57: 224–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratzinger, Joseph. 2006. The God of Faith and the God of Philosophers. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Ribberink, Egbert, Peter Achterberg, and Dick Houtman. 2018. Religious Polarization: Contesting Religion in Secularized Western European Countries. Journal of Contemporary Religion 33: 209–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, William L. 2010. Friendly Atheism Revisited. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 68: 7–13. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40981205 (accessed on 1 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Andrés, Rafael. 2022. Historical Sociology and Secularisation: The Political Use of ‘Culturalised Religion’ by the Radical Right in Spain. Journal of Historical Sociology 35: 250–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater, Fernando. 1989. Lo que yo creo. In Dios como Problema en la Cultura Contemporánea. Edited by José M. Díez-Alegría. Bilbao: EGA, pp. 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Santayana, George. 2015. Pequeños Ensayos Sobre Religión. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 2017. Existentialism Is a Humanism. North Charleston: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, George. 2012. La Religion. Barcelona: Editorial Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Barbara Herrnstein. 2010. Natural Reflections: Human Cognition at the Nexus of Science and Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, George H. 2016. Atheism: The Case against God. Amherst: Prometheus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Tom W., and Benjamin Schapiro. 2021. The International Social Survey Program Modules on Religion, 1991–2018. International Journal of Sociology 51: 337–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, Eva Hamberg, and Alan S. Miller. 2005. Exploring spirituality and unchurched religions in America, Sweden, and Japan. Journal of Contemporary Religion 20: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonawski, Marcin, Vegard Skirbekk, Eric Kaufmann, and Anne Goujon. 2015. The End of Secularisation through Demography? Projections of Spanish Religiosity. Journal of Contemporary Religion 30: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltaire. 2021. Candide: Illustrated Edition. Washington, DC: Independently Published. [Google Scholar]

- Von Haller, Albrecht. 2009. Discours sur la L’irreligion. Oú l´on Examine ses Principes et ses Suites Funestes. Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Von Haller, Albrecht. 2012. Lettres sur les Vérités les Plus Importantes de la Révélation. Charleston: Nabu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1992. The Sociology of Religion. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 2018. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Connecticut: Franklin Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, Phil. 2009. Atheism, Secularity, and Well-Being: How the Findings of Social Science Counter Negative Stereotypes and Assumptions: Atheism, Secularity, and Well-Being. Sociology Compass 3: 949–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, Phil. 2020. Society without God, Second Edition: What the Least Religious Nations Can Tell Us about Contentment. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, Miron, Jordan Silberman, and Judith A. Hall. 2013. The Relation between Intelligence and Religiosity: A Meta-Analysis and Some Proposed Explanations: A Meta-Analysis and Some Proposed Explanations. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology 17: 325–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year (Study) | 2008 (Study 2776) | 2018 (Study 3194) |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 18 and over | 18 and over |

| Sample | 2768 | 1733 |

| Sample error | ±1.9% | ±2.4% |

| Confidence level | 95.5% (2 sigmas), P = Q | 95.5% (2 sigmas). P = Q |

| Realization | CIS | CIS |

| Assignment | ISSP “Religion III” | ISSP “Religion IV” |

| Data availability and legal requirements | https://bit.ly/3Ki2W54 (accessed on 1 October 2022) | https://bit.ly/3vf7DZh (accessed on 1 October 2022) |

| 2008 | 2018 | ∆% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atheist | 9.8 | 17.0 | 73 |

| Agnostic | 10.5 | 11.3 | 8 |

| Deist | 12.1 | 11.8 | −2 |

| Skeptics/believer | 28.9 | 29.3 | 1 |

| Believer | 38.8 | 30.6 | −21 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Atheist | Agnostic | Deist | Skeptics/Believer | Believer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | Men | Women | Women | Women |

| Age | 18–35 | 18–35 | 18–35 | Aged 18–35 to 36–50 | Aged 51–94 to 66–94 |

| Education | Secondary and above | Secondary and above | Secondary and above | From primary and secondary to higher education | From no education and primary to secondary |

| Marital status | Single and separated | Single and separated | From married to divorced, separated and single | Married and divorced | Married and widowed |

| Political Ideology | Left | From Left to Center Left | From Left to Center Left | From Center Right to Center | From Center Right and Right |

| Status | Upper class and skilled workers | Upper class | Upper class and new middle class | From new middle class to upper class. | Workers and old middle classes |

| Atheist | Agnostic | Deist | Skeptics/Believer | Believer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | 2008 | 2018 | |

| Gender (Women) | −0.908 *** | −0.853 *** | −0.557 ** | −0.537 ** | −0.087 | −0.009 | 0.043 | 0.218 ** | 0.573 *** | 0.637 *** |

| Age | −0.019 ** | −0.016 ** | −0.022 *** | −0.007 | −0.013 * | −0.013 * | −0.01 ** | 0 | 0.03 *** | 0.022 *** |

| Education | 0.167 * | 0.076 | 0.17 ** | 0.079 | 0.068 | 0.116 | −0.053 | 0.005 | −0.168 ** | −0.121 * |

| Political ideology | −0.432 *** | −0.402 *** | −0.101 * | −0.034 | −0.143 ** | −0.128 ** | 0.073 * | 0.082 ** | 0.223 *** | 0.275 *** |

| Marital status (Married) | −0.675 *** | −0.444 * | −0.205 | −0.088 | −0.148 | −0.226 | −0.278 * | 0.312 * | −0.064 | 0.331 * |

| Status | 0.018 | −0.07 | −0.041 | 0.001 | −0.038 | −0.153 * | −0.034 | −0.006 | 0.069 | 0.177 ** |

| Constant | −0.914 | 2.083 | −1.329 | −0.986 | −0.708 | −0.802 | −0.324 | −1.7 | −2.522 | −4.595 |

| Log likelihood | 1012.374 | 1074.278 | 1117.497 | 979.876 | 1221.876 | 956.156 | 1963.632 | 1628.658 | 1833.674 | 1352.243 |

| Cox & Snell R2 | 0.09 | 0.121 | 0.032 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.031 | 0.01 | 0.014 | 0.132 | 0.133 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.176 | 0.2 | 0.062 | 0.023 | 0.032 | 0.059 | 0.014 | 0.019 | 0.183 | 0.194 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herranz de Rafael, G.; Fernández-Prados, J.S. Explanation of the Trends and Recent Changes in Spanish Society Regarding Belief in God: Atheism, Agnosticism, Deism, Skepticism, and Belief. Religions 2022, 13, 1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111086

Herranz de Rafael G, Fernández-Prados JS. Explanation of the Trends and Recent Changes in Spanish Society Regarding Belief in God: Atheism, Agnosticism, Deism, Skepticism, and Belief. Religions. 2022; 13(11):1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111086

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerranz de Rafael, Gonzalo, and Juan S. Fernández-Prados. 2022. "Explanation of the Trends and Recent Changes in Spanish Society Regarding Belief in God: Atheism, Agnosticism, Deism, Skepticism, and Belief" Religions 13, no. 11: 1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111086

APA StyleHerranz de Rafael, G., & Fernández-Prados, J. S. (2022). Explanation of the Trends and Recent Changes in Spanish Society Regarding Belief in God: Atheism, Agnosticism, Deism, Skepticism, and Belief. Religions, 13(11), 1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111086