3.1. Government Response to COVID-19 Outbreak

Korea experienced pandemics such as SARS in 2003 and MERS in 2015, but the country has not experienced an infectious disease that stayed for as long a time as COVID-19, affecting various areas such as the economy, society, and culture. Since 2020, the government has been implementing various measures such as social distancing, quarantine, and prohibition of small gatherings to cope with COVID-19. These measures can be divided into restrictive measures such as the prohibition of gatherings and restrictions on the number of people; supportive measures such as online religious activity and medical service; and punitive measures based on the degree of violation of executive orders.

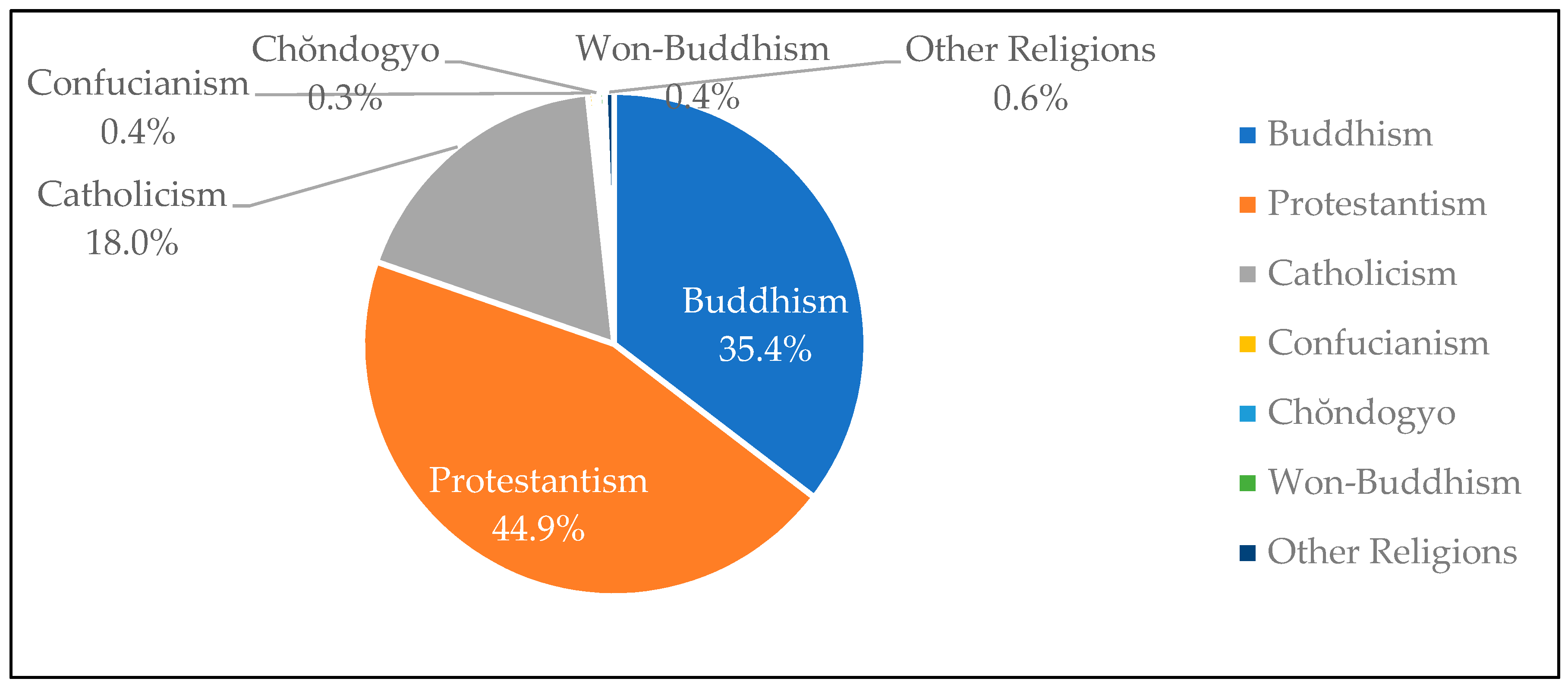

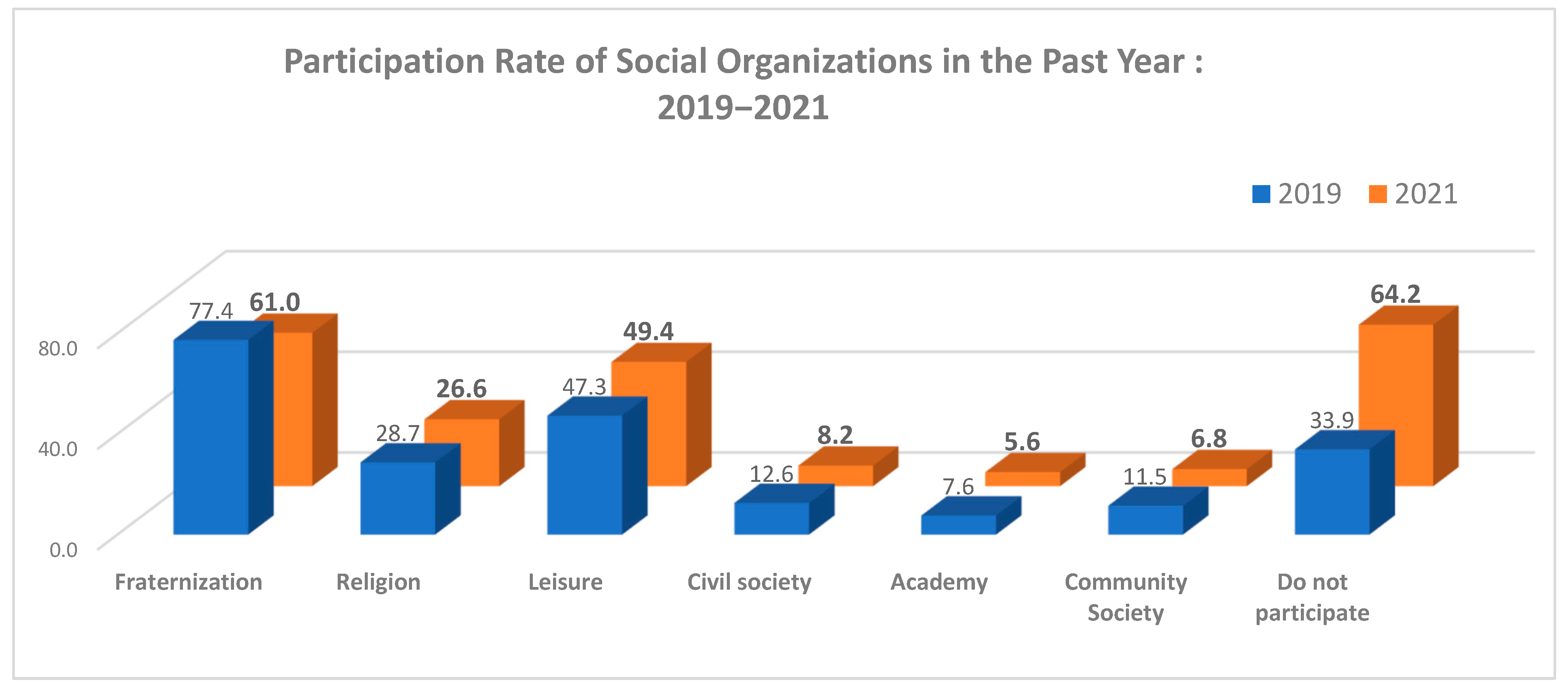

In general, the followers of the various Korean religions, including Buddhists, Protestants, Catholics, Won Buddhists, and Chŏndogyo practitioners, actively cooperated with the government’s quarantine measures. Nevertheless, it has been inscribed on people’s minds that religious gatherings and activities intensify the spread of COVID-19 because religious gatherings and activities at the Shinch’ŏnji Church in Taegu ignited the outbreak of the virus. Along with it, according to the 2020 COVID-19 infection routes reported by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in religions other than Shinch’ŏnji Church and in nursing hospitals and facilities, 33.1% of all confirmed cases were related to religion. For this reason, the Shinch’ŏnji Church and Protestant churches were heavily criticized by society (see

Table 2). However, the flip side of the same token, that most nursing facilities are religious, is ignored. This means that religion is carrying the social burden on behalf of the government.

In addition, religious services in some Protestant churches continue to be held, and some religiously-associated institutions kept going, violating the government’s prevention policies. When news regarding this appeared in the media, it seems that religion was the cause of the outbreak.

3.2. Religions Reported in the Media during the COVID-19 Era

After the outbreak of COVID-19, the image of religion became negative, as the spread of COVID-19 accelerated and conflicts in the religious communities over the government’s quarantine measures continued. The image of religion during the pandemic seemed to be dominated by the news about Shinch’ŏnji Church.

In this study, we collected and analyzed all data on religions reported in the media after COVID-19 using Big Kinds (

BIGKINDS 2022,

www.bigkinds.or.kr, accessed on 15 September 2022), a database provided by the Korea Press Promotion Foundation. To this end, 54 media companies, including national and local daily newspapers, broadcasters, and magazines, were analyzed from January 2020 to December 2021 by searching “religion,” “Christianity,” “Catholicism,” and “Buddhism” (the three major religions in Korea), and “COVID-19” and then analyzing the keywords in each article and setting representative words with a high frequency of appearance. A CONCOR (Convergence of iteration correaltion) analysis was performed to extract topics consistently using UCINET and NetDraw (which are social network analysis software) to understand the relationship between words.

We found that 10,533 articles appeared in the media in 2020 and 5497 articles appeared in 2021, that is, a total of 16,020 articles, with the 2020 articles accounting for 65.8% and the 2021 articles accounting for 47.8%. The most frequently mentioned words for both years are “COVID-19,” “confirmed case,” and “Seoul,” followed by “Taegu,” “Coronavirus,” and “Shinch’ŏnji” in 2020 and “distancing phase,” “religious facilities,” and “Korea” in 2021 (

Table 3). These words are ranked high as per the current situation of the respective years. In 2020, the COVID-19 group infection at Shinch’ŏnji Church in Taegu increased social confusion, and as the COVID-19 situation persisted in 2021, it is believed that the frequency was high because of adjusting social distancing phase to counter the challenge of group infections occurring frequently in religious facilities.

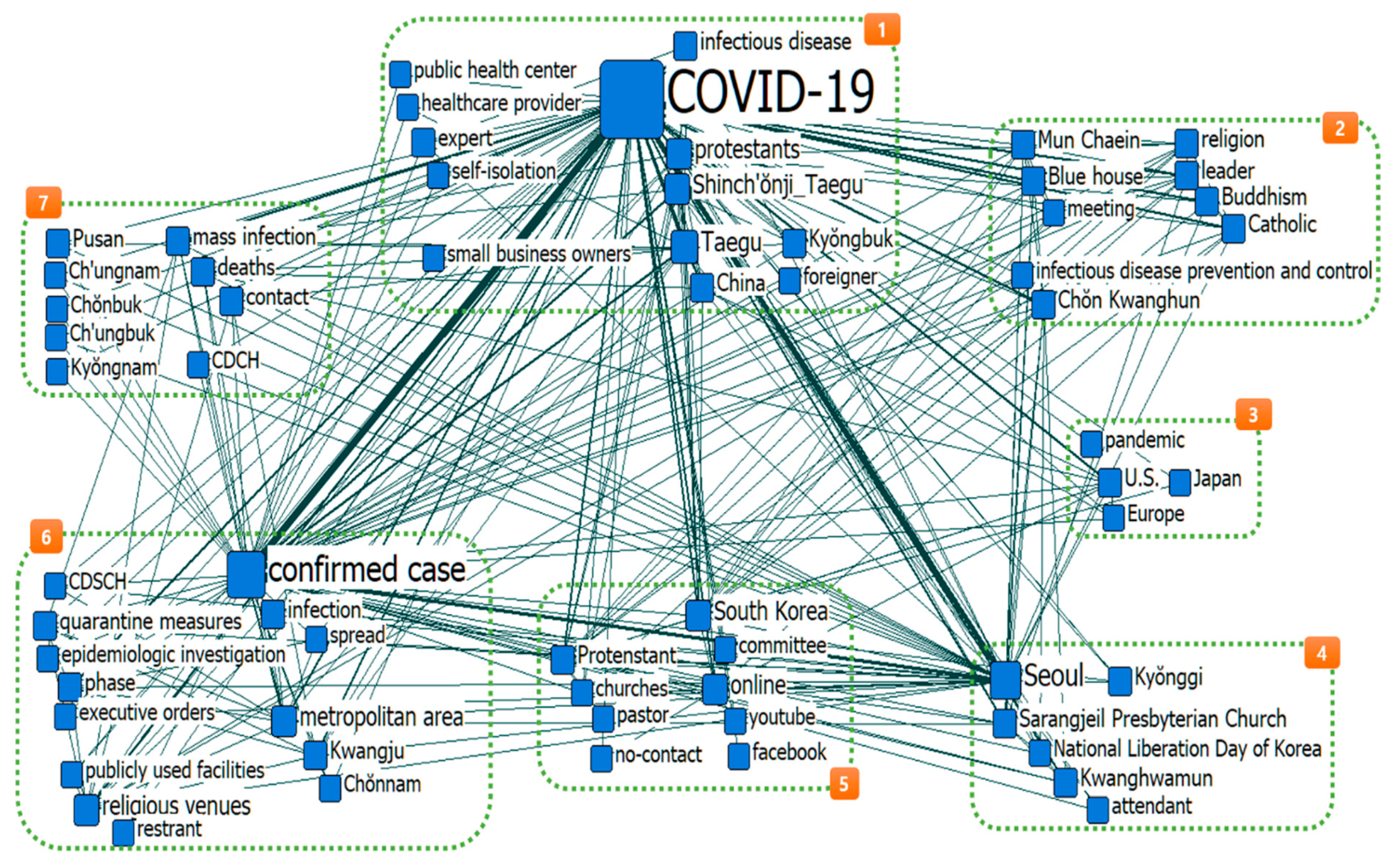

The 2020 data were analyzed using CONCOR and sorted into seven types (see

Figure 3). Type 1 included COVID-19, infectious diseases, Shinch’ŏnji, Taegu, Kyŏngbuk, China, foreigners, health centers, medical personnel, experts, and self-confinement. The outbreak began with foreigners entering from China and included a surge in confirmed cases in Taegu and Kyŏngbuk due to mass infection in Shinch’ŏnji Church in Taegu. It was declared to be at an “outbreak status in Korea” and was classified as “government response,” as it was related to the government’s response through government officials, experts, medical personnel, health centers, and self-confinement. Type 2 was considered to be included in this type because the president met with religious leaders, including the campaign by right-wing leaders in Protestantism (i.e., Chŏn Kwang-hoon) to oust the President of Korea as a response to the government policy. It was called a meeting between the president and the religious community, which is the main content of Type 2. Type 3 was about the current status overseas, and Type 4 was named “Kwanghwamun Assembly” in connection with the mass infection caused by the Kwanghwamun rally on Liberation Day by Love First Church’s opposition to the government’s quarantine measures. For Type 5, as Christianity resorted to non-face-to-face online worship due to the prohibition of rallies and gatherings and as it included content about much fake news originating in Christianity through Facebook and YouTube, “non-face-to-face worship” was selected as the keyword. Type 6 included conducting epidemiological investigations by quarantine authorities in the Seoul metropolitan area, Kwangju, and Chŏnnam—due to the spread of the disease through religious facilities and restaurants—and the issuing of administrative orders in case of violation of the quarantine rules; therefore, it was titled the spread of COVID-19 due to multi-use facilities. Type 7 became an issue because of group infections due to contact with confirmed patients in Pusan, Inch’ŏn, Ch’ungbuk, and Kyŏngnam.

We comprehensively analyzed the 2021 data using CONCOR and classified them into 6 types (see

Figure 4). Based on the keywords, the main issue of Type 1 was titled “payment of COVID-19 emergency disaster support due to COVID-19, Seoul, Kyŏnggi-do, emergency disaster support funds, small business owners, experts, and medical personnel,” and Type 2 consisted of a meeting between president Mun Chae-in and religious leaders and an online Easter joint service and was divided into a “meeting between the president and religious leaders” and “Christian online service.” Type 3 was related to the Kwanghwamun rally against the government’s COVID-19 response, led by Pastor Jeon Kwang-hoon of Love First Church and was classified as “Kwanghwamun rally.” Type 4 included Kwangju, Jŏnnam, quarantine, quarantine authorities, group infection, epidemiological investigations, and quarantine rules and was named “quarantine measures due to group infections.” Type 5 was classified as “multi-use facility management,” as it included multi-use facilities, religious facilities, restaurants, karaoke, Taejeon, Ch’ungbuk, distancing phases, and management. Type 6 included Pusan, Inch’ŏn, Kyŏngnam, Ulsan, Kyŏngbuk, metropolitan areas, schools, nursing hospitals, confirmed patients, spread, and life treatment centers. Due to the increase in the number of confirmed cases in nursing hospitals and schools, tests and treatments at screening clinics and medical services (if confirmed) were provided at residential treatment centers, and this was classified as “increase in the number of confirmed cases and medical services support.”

The CONCOR analysis results on religion in the COVID-19 era, as they appeared in the media, could be divided into the spread of COVID-19, quarantine, government response, cooperation system, and problems. Issues related to the spread of COVID-19 included Shinch’ŏnji Church, religious facilities, and group infections, and these corresponded with quarantine authorities, quarantine rules, and epidemiological investigations. With the government’s response, restrictive measures included distancing, non-face-to-face religious activities, quarantine rules, and administrative orders; support included emergency disaster support and medical services; and the cooperative system included the government, religious circles, experts, and medical personnel.

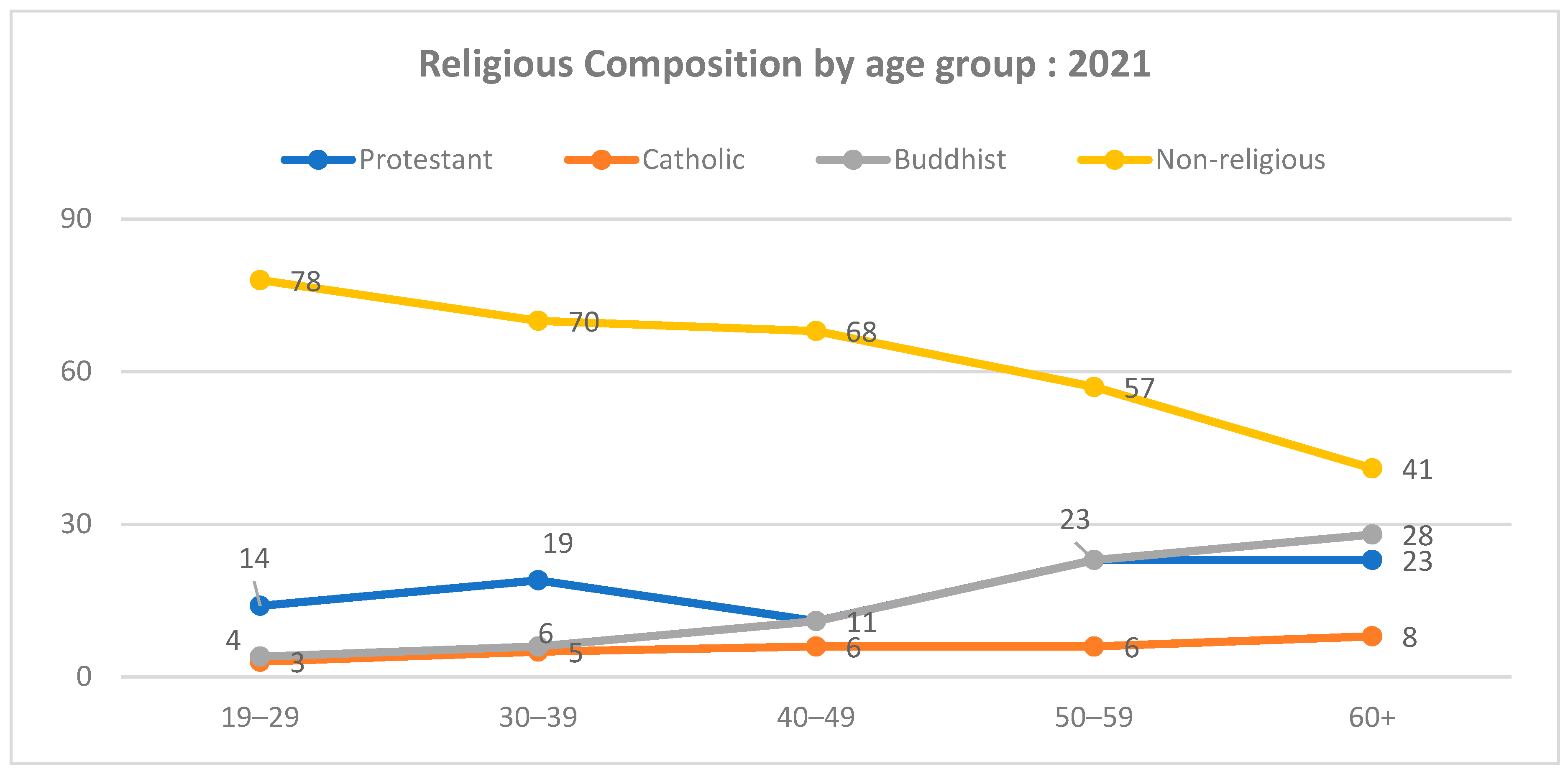

The outbreak of COVID-19 was partly mediated by the Shinch’ŏnji Church and some Protestant churches at its initial stage; accordingly, the government imposed a 15-day suspension on religious gatherings (21 March 2020). From then on, most religious institutions developed measures to support online religious activities, considering the status of COVID-19 and social situations, and issued administrative orders in case of violation of quarantine rules. The government’s strong ban later caused the issue of religious freedom among right-wing religious leaders. However, it should not be ignored that, with regard to the issue of religious freedom, most Koreans including religious ones and even Protestants do not think that religious freedom is a higher priority than public health.

3.3. Freedom of Religious Gathering Issue

Korean Government’s strong policy on the prohibition of gatherings and restrictions on religious gatherings was politicized by the right to discuss the issue of religious freedom. The legal basis for prohibitions was Article 49 of the “Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act,” which is an order to prevent the rapid spread of infectious diseases in Korea (

S. R. Kim 2020). Specifically, Pastor Chŏn, Kwang-Hoon, who was a right-wing political leader, had strongly protested the government-imposed restriction on public gatherings as he mobilized his political campaign against Mun Chae-in’s administration. With political ingenuity, he accommodated the issue of religious freedom in his political campaign, as he continued to demonstrate his opposition to the Mun Chae-in government, thus violating the government’s quarantine measures, resulting in the spread of COVID-19.

Therefore, when the Seoul Metropolitan Government banned Love First Church from holding rallies on the grounds that it violated quarantine rules, the Christian Council of Korea, whose chairman was Chŏn, Kwang-Hoon, issued a statement saying, “The executive order to suspend worship in the church is illegal and is religious suppression” (

TCCK 2020b). He also organized “Free Citizens’ Solidarity for Restoration of Worship” and protested by filing a constitutional petition and an administrative lawsuit, saying that the ban on face-to-face church worship for COVID-19 prevention was unconstitutional (

Nam 2022). Indeed, although the Christian Council of Korea criticized the government’s strong policy suspending worship in Protestant churches as religious suppression and held a series of mass rallies at Kwanghwan in Seoul, the vast majority of Koreans viewed it as a right-wing political campaign against the administration and as a major factor in spreading COVID-19, and it resulted in a cultural disgust toward Protestant churches. This protest may be seen as representing the Protestant church’s position on freedom of religious assembly, but ordinary citizens including lay Christians have developed distrust for religion as a whole, especially Protestantism.

In the academic circle, it triggered a constitutional debate on whether or not the restrictions on basic rights guaranteed under the Korean Constitution for freedom of religion were appropriate (

S. R. Kim 2020). Nam highlighted the possibilities and limitations of restricting religious freedom by executive orders in the COVID-19 context focusing on the precedents of the Federal Court in the United States (

Nam 2022). In contrast, Han explains how the Catholic Church in Korea cooperated with the Government’s prevention measures; they not only faithfully followed the guidelines of the Vatican but also broadly understood the position of the Korean government, without causing unnecessary clashes or conflicts (

Han 2020).

In this process, the role of the media, including mass media and social media, should not be overlooked. They framed this issue as an issue of religious freedom. However, in reality, it was quite politicized because they completely disregarded the majority of Protestant churches participating in the government’s distancing policy, only focusing on the Kwanghwamun rally, which was anti-government and conservative. Unlike the politically inclined right-wing Protestants, most Korean religions actively cooperated to overcome the pandemic, considering that the government’s policy to ban or restrict religious gatherings during the COVID-19 pandemic was critical for the recovery of public health and interests.