Abstract

The setting: 83 reports of healing related to prayer (HP) were evaluated between 2015 and 2020 in the Netherlands. Research questions: What are the medical and experiential findings? Do we find medically remarkable and/or medically unexplained healings? Which explanatory frameworks can help us to understand the findings? Methods: 83 reported healings were investigated using medical files and patient narratives. An independent medical assessment team consisting of five medical consultants, representing different fields of medicine, evaluated the associated files of 27 selected cases. Fourteen of them received in-depth interviews. Instances of healing could be classified as ‘medically remarkable’ or ‘medically unexplained’. Subsequent analysis was transdisciplinary, involving medical, experiential, theological and conceptual perspectives. Results: the diseases reported covered the entire medical spectrum. Eleven healings were evaluated as ‘medically remarkable’, while none were labelled as ‘medically unexplained’. A pattern with recurrent characteristics emerged, whether the healings were deemed medically remarkable or not: instantaneity and unexpectedness of healing, often with emotional and physical manifestations and a sense of ‘being overwhelmed’. The HP experiences were interpreted as acts of God, with a transformative impact. Positive effects on health and socio-religious quality of life persisted in most cases after a two and four year follow-up. Conclusions: the research team found it difficult to frame data in medical terms, especially the instantaneity and associated experiences in many healings. We need a broader, multi-perspective model to understand the findings. Horizontal epistemology, valuing both ‘subjective’ (experiential) and ‘objective’ data, may be helpful. An open dialogue between science and religion may help too. There is an analogy with healing narratives in the Bible and throughout church history. Future studies and documentation are needed to verify and clarify the pattern we found.

1. Introduction

Praying for health concerns has been a common practice throughout history () right up to today (). Despite secularization the topic still gains a lot of interest with people flocking to pilgrimage sites and prayer healing services. However, practices vary a lot. The setting can differ from distant, personal and group prayers, to visiting a prayer healing service or a pilgrimage site. There is also a variety of modes, such as anointing, laying on of hands, the use of a prayer cloth or taking a ritual bath (). Whatever the setting or the mode, the intention remains the same: an appeal to God for healing of a disease.

As a general medical practitioner the first author (DK) was confronted with this when someone in his practice was suddenly healed in a prayer meeting (). The healing sparked nationwide interest in the Netherlands and its aftermath led us to conduct this research. Other experiences and narratives as well as a lack of knowledge further motivated the authors to set up a study.

A number of studies in the field of healing and prayer (HP) can be found in medical literature. Most of them relate to clinical trials comparing groups of patients with a specific disease. One group received prayers for healing (intercessory prayer), while the other group did not receive these prayers. Both groups did not know whether they were prayed for or not. Eventually a Cochrane review in 2009 including 10 such trials with a total of 7646 patients showed inconclusive results for the effects of intercessory prayer (). However, the performing of these studies involves considerable methodological and conceptual difficulties (; ). It is difficult to set fixed background conditions for research on healing after prayer. For instance, friends, family, and members of religious congregations may be praying outside the context of the study. Others find it impossible to investigate prayer as if it were a drug or surgical intervention (; ).

Few publications are about individual case reports, considered to be unexplained by a team of medical consultants. Most of them relate to Lourdes, e.g., a case report about a cure of sarcoma of the pelvis (), or to Rome. () described a miraculous cure of acute myelogenous leukemia leading to the canonization of a saint at the Vatican. The Global Medical Research Institute (GMRI) in the USA adopted a rigorous procedure to assess whether to consider a cure as unexplained or not, operating predominantly in circles of Pentecostal and charismatic Christians. Recently they published about two such cures, one of them from chronic gastroparesis since 16 years and the other one from juvenile macular degeneration blindness (, ). Still, it is an ongoing journey to publish about these cures as there may often be mistrust among church denominations and patients involved, causing reluctance to participate ().

More recently some qualitative HP studies (; ; ) were conducted by mode of semi-structured interviews with individuals who had experienced healing of different illnesses. Experiential and spiritual aspects accompanying the healings were investigated primarily. Reports mentioned sensory manifestations and extraordinary events such as visions or ‘a transformational, powerful touch’. However, these studies focused more on experiential findings rather than medical data.

Additionally, other publications are about theoretical frameworks trying to understand HP experiences (; ). It is beyond the scope of the introduction to reflect upon them extensively, but explanatory perspectives will be further discussed elsewhere in the article.

When reviewing the above literature we concluded that there is gap in our knowledge. HP experiences relate to medical and experiential data, the analysis of the data relates to other disciplines as well such as psychology, philosophy and theology. The authors therefore decided to conduct a transdisciplinary study including the above fields of knowledge simultaneously. It took time to work out an innovative research proposal that combined these disciplinary fields, and to get it approved by both the medical ethics review board as well as the faculty of theology. Eventually it was decided to combine meticulous medical evaluation of individual HP reports with qualitative research pertaining to experiences and individual interpretations as this gives us the opportunity of looking at the subject through different lenses. The perspectives can mutually enrich each other, strengthening the relevance of our findings and conclusions.

A case study research was designed () to explore the following research questions: What do we find when viewing reports of prayer healing against a background of medical and experiential data? Do we find medically remarkable and/or medically unexplained cures? Which explanatory frameworks (multidisciplinary) can help us to understand the findings?

We received 83 individual prayer healing reports, of which 27 were evaluated by a medical assessment team. In 14 cases an in-depth interview was conducted, attempting to understand subjects and their experience, according to a naturalistic approach ().

Finally, it is relevant to realize that this article is part of a thesis together with other publications. The design article was mentioned above (), the other articles are mentioned elsewhere in the text to clarify the connection with this study.

2. Theoretical Background

Praying is a highly personal, context-bound activity and the study of its possible effects on the course of illness and disease has been controversial. From a medical point of view prayer cannot be seen as an intervention in the usual sense. Therefore, standard methods of studying treatment effects do not apply to prayer. This seems to suggest that from a medical point of view, prayer cannot be seen as a proper subject for medical research.

On the other hand, many patients report to have prayed for cure or alleviation of their suffering. Some of the patients tell their doctors that they have experienced improvement of their condition after these prayers, although there is no biomedical explanation for it. They attribute their unexplained improvement to religious factors such as, for instance, acts of God, the healing effect of His spiritual presence, or the mediating role of some religious ritual. Given these reports, what could be appropriate methods to study them? What are relevant theoretical frameworks for the study of patient stories about prayer and subsequent clinical improvement for which there exists no biomedical explanation? There are, obviously, many possible approaches: psychological, social, anthropological, moral, theological, as well as philosophical approaches.

Apart from randomized controlled trials and a Cochrane review () we also found some observational and qualitative modes of research, combined with an overarching more philosophical perspective. (), for instance, used Watson’s concept of transpersonal caring theory in nursing as a theoretical framework (). The term transpersonal acknowledges that individuals are a composite of mind, body and spirit (or soul). Love, faith, compassion, caring, community are as important to healing as conventional treatment methods. The underlying worldview emphasizes the fundamental inter-connectedness of everything that exists. () conducted a qualitative study of extraordinary religious healing experiences in Norway. To understand participants’ healing experiences, they used the concept of the ‘lived body’ as theoretical perspective. This idea is based on the philosophy of () who criticized the pervasive mind–body dualism in medicine and psychology and offered an alternative by viewing mental phenomena as fundamentally ‘embodied’ and bodily phenomena as expressing the tacit meaningfulness of the ‘lived body’ (the body subject). Medical treatment is not understood as ‘fixing the machine’, it addresses the lived body. Life experiences are inscribed in this body and may contribute to health or disease later in life.

() use the term trans-somatic recovery in a qualitative study of prayer healing experiences. Trans suggest the presence of a transformative and transcending dimension in (some) healing experiences. It refers to aspects of healing that go beyond (‘transcend’) the duality of body and mind and include a spiritual (‘transformative’) dimension: an experience of improved wellbeing and a radical change due to an encounter with God, involving each aspect of life.

Qualitative studies on HP seem better able to include the contextual aspects and the multifaceted nature of HP experiences. It is especially challenging to not only report about experiential and contextual data, but also to relate them to well documented medical data. This is the aim of the present article. Helming and Austad et al. do not provide these ‘medical’ details. There exists, in general, a tendency in the literature, to split up objective (‘medical’) facts and subjective (‘experiential’) reports. This article sees it as its challenge to combine these data and to include a clinical perspective. We will therefore address three different perspectives (triangulation): the medical findings, the experiences of the patients and the clinical associations of the doctors. Abma advocates for participatory modes of research (). This type of research values scientific knowledge, but it gives equal weight to practical-professional (clinical) knowledge and existential-experiential knowledge developed by clients/patients (as ‘experts by experience’). The broadening of horizons and greater understanding may be achieved through mutual dialogue and learning. This process of co-creation is difficult and meticulous but offers the promise of new and better understanding ().

We will first present the medical findings, the practitioner’s perspective of the clinicians, and the existential-experiential perspectives of the patients. The combined findings will then be used as starting point for a discussion on what occurs during and after HP. The transdisciplinary model that will be employed, includes inputs from medicine, socio- psychology, phenomenology, theology, and philosophy.

3. Methods

At Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, and Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc, a protocol was developed to facilitate a retrospective, case-based study of prayer healing (HP) reports (). The study took place between 2015 and 2020.

The members of the research team (study, medical assessment) have different ideological and (non-) religious backgrounds.

3.1. Recruitment, Initial Assessment and Selection

Any individual in the Netherlands or neighboring countries who claimed to have been healed through prayer could be included. The perception of the prayer by the individual was pivotal, not the type or sort of prayer. HP reports came via multiple sources: newspaper articles and other media, the research team and their direct vicinities, prayer healers, and medical colleagues. Attention to the study by different media triggered many reports.

Reports of HP were investigated systematically using a step-by-step method. Initially the reports were reviewed by the first author, if need be this was followed by a phone contact to clarify some of the issues. Upon consent medical data was obtained before and after the prayer(s) involved. A case was selected for evaluation by a medical assessment team when complying with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

- -

- Likelihood when compared to the Lambertine criteria (outlined below).

- -

- Completeness of medical data.

- -

- Duration of healing to assess if a recovery is ongoing, in serious chronic diseases or malignancies preferably at least five years.

- -

- Healings before 1990 were excluded because of difficulty in finding medical data (there was one exception in this study).

The first author consulted one of the other assessment team members when in doubt as to select a case or not.

3.2. Medical Assessment

The independent medical assessment team consisted of five consultants (internal medicine, hematology, surgery, psychiatry, neurosurgery). Other medical disciplines were consulted when deemed necessary. With some modifications the procedure of medical assessment was based upon the procedures at Lourdes pilgrimage site (France), after a visit to Lourdes by the first author (DK).

The assessment team carried out a standardized evaluation to determine if a cure was ‘medically unexplained’ or ‘medically remarkable’. ‘Medically unexplained’ indicated that no scientific explanation could be found at the time of assessment. The classification ‘medically remarkable’ refers to a healing that is surprising and unexpected in the light of current clinical and medical knowledge and that has a remarkable (temporal) relationship with prayer. For instance, someone with a chronic debilitating disease is suddenly cured, when the best possible prognosis would be one of gradual regression.

Classification was supported by consulting the ‘Lambertini criteria’ (). These are used by medical committees in Lourdes—and elsewhere within the Roman Catholic Church—to determine if a cure is scientifically unexplained ().

In our study we used the following—slightly modified—versions of these criteria:

- The disease has to be serious.

- The disease is known under medical classifications, and the diagnosis should be correct.

- It must be possible to verify the healing with reference to medical data, such as medical history, physical examination, laboratory and radiology investigations.

- The cure cannot be explained by medical treatment in the past or present, nor by the natural course of the disease, such as spontaneous improvements or temporary remissions.

- The cure is unexpected and instantaneous. Although the recovery may take some time, its onset should be instantaneous and related to prayer.

- The cure is either complete or partial with substantial improvement. The individual is fully or largely returned to his or her original state of health.

- The cure is permanent (by the scope of the study time).

3.3. Qualitative Research, In-Depth Interviews

An in-depth interview by a senior researcher (EB) was taken in those instances when the assessment team considered the possibility of a healing case to be ‘medically remarkable’ or ‘unexplained’. The interviews were face-to-face, mostly at the homes of the participants, lasting 1.5–2 h. The objective was to gain insight into the individual’s experiences, the background history and perceptions of the prayer healing experience(s) and health outcomes as well as outcomes in other spheres of life. It allowed for comparison between medical and experiential data, especially when relating them to the moment of prayer. The approach followed a qualitative research methodology (). A topic list was used. The interviews were initially recorded and written out verbatim. Subsequently a report was made, which was verified with the patient by means of a member check (). A phenomenological interpretative analysis () was completed by the senior researcher and discussed in the assessment team. Based upon the report and the discussion the assessment team re-evaluated their initial decision.

A fully documented case for evaluation thus consisted of information derived from the individual’s personal written entry, the full medical file, a transcript of the interview, the report of the interviewer based on the transcript, the notes of discussions in the medical assessment team, and expert opinions when relevant.

3.4. Level of Expectancy

The level of expectancy ‘to be healed by prayer’ (as a retrospective self-report) was divided into 4 categories: none, low, moderate or high expectancy. The scale was based upon the personal experience of the participant without using numerical parameters. Scoring was done by the first author using written entries, interviews and conversations by phone and by mail.

3.5. Follow-Up

HP reports were received primarily in 2016 and 2017. Two follow-up studies were done by one and the same research student in 2019 and 2021. As many participants as possible were interviewed to obtain actual information about the health status and the socio-religious quality of life. Mostly by phone, occasionally a participant was visited. A topic list was used. Reports of the interviews were made. Positive and negative effects on the socio-religious quality of life were documented.

4. Results

4.1. Highlights

Table 1 reflects that we received 83 HP reports, of which 27 were selected for evaluation by the medical assessment team. In this group of 27 selected participants 14 in-depth interviews were conducted. Eventually eleven cases were considered to be ‘medically remarkable’. None of them was evaluated as ‘medically unexplained’.

Table 1.

categories of cases after selection and evaluation/assessment.

Diagnoses of the diseases in eleven ‘medically remarkable’ cases are listed below:

- Crohn’s disease

- Acute leukemia (temporary healing)

- Chronic herpetic keratitis one eye with low vision

- Iatrogenic aortic dissection

- Psoriasis with chronic arthritis + ulcerative colitis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Anorexia nervosa

- Parkinson’s disease (90% healing, partial relapse after 8–9 years)

- Drug induced hepatitis, Vanishing bile duct syndrome

- Multimorbidity: severe asthma, impaired hearing, inflammatory osteo-arthritis, incontinence

- Ulcerative colitis with debilitating diarrhea (40 times daily)

4.2. Results: Data Were Obtained until 2021

Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 provide basic data: participant characteristics, reasons for limited data, origin of reports, and prayer setting.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics (demographic data).

Table 3.

Reasons for limited availability of data.

Table 4.

Origin of reports, Prayer setting of prayer(s) associated with healing.

Geographically there was a fairly even distribution across the country with the densely populated provinces of South Holland (25) and North Holland (11) having most reports. The ten other provinces were all represented, sharing 43 reports. Additionally three reports were from Belgium and one was from Germany.

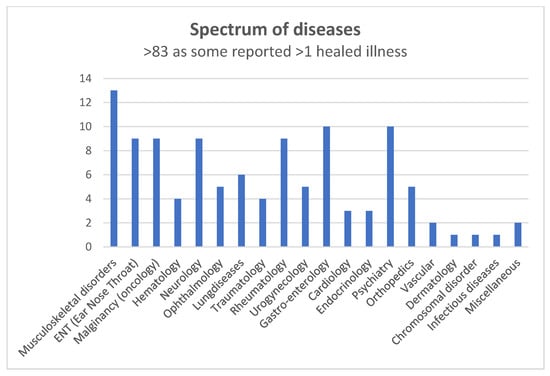

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 and Figure 1 are about the medical data primarily. Table 5 and Figure 1 give information about the spectrum of all diseases reported while Table 6 focuses on the 27 medical evaluations, including data about prayer setting during a healing experience and accompanying manifestations. Seventeen healings could not be labelled as medically remarkable/unexplained, the reasons are listed in Table 7. In some cases mismatches were found between ‘subjective’ and ‘objective data’, this is specified in Table 8.

Table 5.

Spectrum of diseases reported (n > 83 as some report > 1 healed illness).

Table 6.

27 evaluations by the medical assessment team; availability of data until 2021. E = expectancy NE = no expectancy LE = low expectancy ME = moderate expectancy HE = high expectancy N/A = not applicable (e.g., comatose); Age = age category at moment of healing. Duration of healing: time period from healing until 2021 or until relapse/death.

Table 7.

Seventeen healings could not be evaluated as medically remarkable or unexplained by the medical assessment team, reasons are listed below.

Table 8.

Mismatches between subjective and objective data were outspoken in seven cases.

Figure 1.

Spectrum of diseases reported.

The assessment team evaluated 27 cases in the period between 2016 and 2020.

Table 9 reflects data about all reports, which were not evaluated by the assessment team. Data in this group provide us with information about instantaneity of healing, setting of the prayer(s) and accompanying manifestations. No medical conclusions can be drawn since they were not evaluated. The availability of medical data alternated.

Table 9.

Data of 56 reports, which were not evaluated by the assessment team.

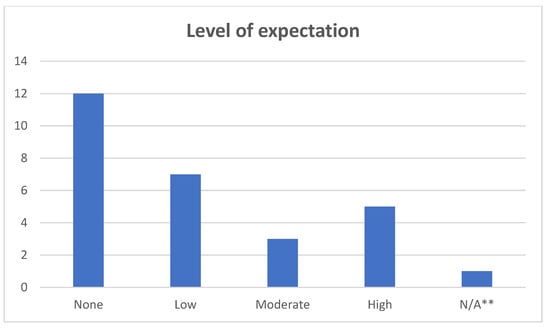

Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12 and Figure 2 focus upon experiential manifestations accompanying reported healings and expectancy. Table 10 lists all reported manifestations including frequencies. A pattern of instantaneity of healing associated with physical and emotional manifestations was found to be dominant, which is reflected in Table 11. This is true both for the subgroup of evaluated healings and for all reported healings. Levels of ‘expectation to be healed’ are indicated in Table 12 and Figure 2.

Table 10.

Reported manifestations (physical, emotional, existential) accompanying all reported healing experiences.

Table 11.

Course of healing and associated manifestations for the subgroup of evaluated healings (EV) and for all reported healings (ALL).

Table 12.

level of expectation to be healed by prayer in retrospective self-report, for all healings (n = 84) and for those evaluated (n = 28).

Figure 2.

level of expectation ‘to be healed by prayer’ (as a retrospective self-report) for 28 healings evaluated. ** Not applicable: comatose state.

Table 13 reflects the explanations which the participants gave for their healings.

Table 13.

Explanation of healing.

4.3. Results of Follow-Up in 2019 and 2021

Table 14.

Health outcome and socio-religious quality of life (QOL).

Table 15.

positive effects mentioned on socio-religious life.

Table 16.

negative effects mentioned on socio-religious life.

In 2019 and 2021 a follow-up was done by re-contacting as many participants as possible, asking them about their actual health status and socio-religious quality of life.

There is a considerable overlap between the 2019 and 2021 follow-up groups, but no complete overlap. In 2021 we managed to contact some people whom we did not contact in 2019 and vice versa. One should therefore be cautious when comparing the two groups.

Additionally we understood that five people had passed away in the meantime: two of them because of a relapse of the disease reported, one because of another disease and in two cases the cause of death is unknown to us.

4.4. A Secondary Result

An intriguing observation of the research was a process developing within the supervisory and assessment teams. Initially the members of the assessment team considered it to be their primary task to make evaluations strictly based on medical grounds. Individual cases were discussed extensively, but in due course there was some discomfort. The team found it increasingly difficult to differentiate between ‘remarkable’ and ‘unremarkable’. When looking at the healings from non-medical angles there were surprising similarities in most of them, whether or not medically remarkable: instantaneity and unexpectedness of healing, associated sensory manifestations and transformative experiences. Just viewing these healings from a medical perspective was not enough. In order to interpret them, it seemed to be necessary to look at them from other perspectives.

5. Discussion

5.1. Major Observations

- When evaluating 27 selected cases out of 83 prayer healing reports, a medical assessment team concluded there were 11 ‘medically remarkable healings’, no ‘unexplained healings’.

- The study population was diverse.

- Diseases reported covered the entire medical spectrum.

- The setting of prayers varied considerably: personal prayers, group prayers, holy communion,

- liturgical prayers, prayer healing services, anointing of the sick, these could all lead to healing experiences.

- Healing experiences took place across all church denominations, and also when there was no church affiliation at all.

- Healing experiences were often unexpected. Expectancy does not seem to play a major role.

- A large majority of the participants reported an instantaneous onset of their healing, very often associated with physical and emotional manifestations at the same time.

- Manifestations varied a lot, but in all cases they were sensed as being positive and meaningful.

- Most healings had a multidimensional character, invariably interpreted as an act of God. Transforming people, often referred to as a healing of ‘mind, body and soul’.

- Due to the multidimensional aspects involved, the assessment team found it increasingly difficult to differentiate ‘medically remarkable’ from ‘a remarkability in a broader sense’.

- Pronounced mismatches were found repeatedly between ‘subjective’ data and ‘objective’ investigations.

- In our follow-up the majority of the participants were still healed 2 and 4 years afterwards with a lasting positive effect on their socio-religious quality of life. It had often triggered a life of benevolence.

- Participants were frequently confronted with negative reactions from outside, in particular from other Christians and from within their churches.

- These observations will now be taken as point of departure for our further discussion.

5.2. The Research Population

In line with known gender differences on religiosity (; ), there is some over-representation of females.

Geographically it is noteworthy that reports were received from all provinces in the country as well as a few from outside the Netherlands.

As is reflected in Table 4 reports came from multiple sources. Media coverage was from different sources such as newspapers, TV channels and social media, with varying ideological backgrounds (liberal, secular, orthodox Christian).

In summary, one may say that the study had access to large parts of society, the study population being sufficiently diverse to allow for the making of conclusions.

5.3. Spectrum of Diseases Reported

The diseases represented the whole medical spectrum (Table 5). Psychiatric disorders were reported in 10 out of 83 cases. Apart from fibromyalgia, which was mentioned 6 times, illnesses of unspecified nature or possibly psychosomatic origin do not appear to be over-represented.

This is contrary to a Dutch study of Van Saane and Stoffels (), who concluded in 2008 that in cases of prayer healing mainly psychosomatic disorders were involved. They did a questionnaire among 900 members of an Evangelical Christian broadcasting organization. Many of them apparently believed that God is able to heal through prayer. A subgroup of 81 reported actual healings. Reports of recovery were from depression, chronic fatigue, backache, headache, fibromyalgia et al. Predominantly illnesses with significant underlying psychological mechanisms, according to Van Saane. However, a list specifying diagnoses in the 81 cases was lacking in their book.

Jacalyn Duffin studied miraculous healings as registered over the centuries in the canonization records of the Vatican. For the period 1950–1999 she listed 134 miracles (). All diseases were serious, often life threatening. Cancer was recorded 25 times.

The studies mentioned above were influenced by study related selection biases: a subgroup of Evangelical Christians (), an advanced medical selection procedure (Duffin) or a request for positive prayer healing reports (ours). We should therefore be cautious when interpreting them. But one may say that both prayer requests as well as healing reports cover wide ranges of illnesses.

5.4. Modes of Presentation and Prayer Settings

In 31 cases a prayer healing service was said to be the setting of a healing experience (Table 4). This picture is distorted as 21 healings were reported by prayer healers themselves. We get a different impression when excluding them: in that case ten healings were reported during a prayer healing service, which is less prevalent than ‘prayers by others’ (20) and equally prevalent to ‘personal prayer’(10). Other settings are common as well: anointing of the sick, prayers by the church community or by a group.

In other words: prayer healing services are not the dominant setting for healing experiences. Rather there is a rich variety of settings.

5.5. Level of Expectation vs. Explanation

Nearly all participants explained their healing as an act of ‘God or a higher power’. From the perspective of the study design this is not surprising when asking people to come forward with prayer healing reports. But something else did surprise us. We expected a positive relationship between expectancy and prayer healing experiences, as a contributing factor explaining such experiences. There is evidence in the literature for the relevance of expectancy. Research by () and a review by () concluded that physical complaints can be altered by placebo and nocebo effects due to induction of positive or negative expectations. This was demonstrated in different medical settings.

However, in our study a vast majority had a low level of expectancy or no expectancy at all prior to their prayers, versus a minority with a moderate or a high level of expectancy (Table 12, Figure 2). This is in line with empirical research by Candy G Brown on HP in the US and Brazil, through written surveys and telephone interviews of people attending Pentecostal healing conferences. In her book ‘Testing Prayer’ () she concluded: ‘Analysis of the available evidence suggests that, for both Brazilians and North Americans, faith and expectancy may be less significant in predicting healing than either Pentecostal or biomedical theories have supposed’. These results differ from our initial assumptions. They also contradict the view of some theological opinions emphasizing the degree of faith as a precondition for healing.

An additional remark should be made about the role of a ‘spiritual journey’. When analyzing 14 in-depth interviews, () notice: ‘at some point in their life they (i.e., the respondents) embark on a quest for faith, for their God’. One wonders about the association of these spiritual quests and the occurrence of a healing experience. Some of our participants, notably the ones with MS (EV14 Table 6) and aortic dissection (EV12 Table 6), had a heightened awareness of the relevance of prayer. There was increased prayer activity coinciding with the intention of visiting a healing service, when they experienced healing very unexpectedly. One of them experienced healing during an afternoon sleep, the other while doing a little job at home. At that specific moment there was no expectancy of healing at all, but they had embarked on a quest. Although the role of such spiritual journeys has not been clarified, it is interesting to take note of it for further investigation.

5.6. Course of Healing

We considered it a noticeable finding that instantaneous onset of healing was reported in 61 out of 84 instances of an HP experience (Table 11), this was emphasized even more when excluding those cases lacking sufficient data about the course of healing (61 out of 73). Gradual recovery, without instantaneous onset, was reported 12 times.

Additionally there was a considerable fraction of 43 participants reporting physical or emotional manifestations (Table 11) in the group of 61 instantaneous healing experiences. This fraction was even higher when excluding those without clear data about accompanying manifestations (43 out of 48). For those with gradual recovery and unknown course of healing (n = 23) eight participants reported manifestations.

The subgroup, which was evaluated by the assessment team, gave the same picture. Even more so, as this subgroup had the advantage of an increased availability of data (Table 11).

A dominant pattern thus evolved of a particularly large group with a sudden onset of their healing experience, very often associated with strong physical and emotional experiences.

The same was found by (), who studied 411 healings at the Lourdes pilgrimage site, France, from 1909–1914 as well as 25 cures acknowledged between 1947 and 1976. They concluded that ‘in two out of three cases the clinical cure was instantaneous, sometimes heralded by an electric shock or pains and, more often, a perception of faintness, or of relief, or of well-being’. And Duffin, who investigated many healings in the Vatican archives, stated: ‘The speed at which patients recovered occasioned many comments of astonishment. When asked if such a cure might have taken place naturally, the doctor would reply—perhaps, but not so quickly’ ().

There is also resemblance with many instantaneous healing experiences, described between 1885 and 1968 in the orthodox Ostrog monastery in Montenegro, Eastern Europe () as well as healings reported by St Augustine in his book the City of God in the 4th/5th centuries AD (see ref., ) and Kathryn (, , ) in the 20th century in North American prayer healing services.

It is interesting to see the same pattern in different eras, at different locations and within varying Christian religious traditions.

5.7. Manifestations

Table 10 lists manifestations accompanying a healing experience during prayer. These occur frequently. Some of them, notably levitation and wind in a closed room, seem to be contradictory to physical laws. In two other cases it was surprising to understand that bystanders had experiences to some extent as well.

All manifestations reported had in common that they were experienced as positive and meaningful, as something which is good. People often felt accepted beyond words, being overwhelmed by a loving power, invariably interpreted as having a divine origin.

() and () also gave examples of HP experiences with manifestations.

Similar experiences are also documented without healing. Poloma and Lee, two sociologists, presented five cases of religious experiences with accompanying manifestations (). All of them reported that they experienced a touch by God, manifested by different phenomena: a gust of wind, an appearance of Mother Mary, a ‘hand’ on the head or in the back, a vision of ‘Angels’ or ‘a rainfall of liquid love’. But none of them described a simultaneous recovery of a disease.

Levin and Steele used the term transcendent experience as an event ‘evoking a perception that human reality extends beyond the physical body and its psychosocial boundaries’ (). Basic characteristics are ineffability, a sense of revelation (or ‘a new sense of life’), positive moods and positive changes in attitudes and behavior. An agenda was proposed for research on the role of transcendent experiences in health. The frequently observed combination of healing with powerful experiences in our study seems to underline the necessity. Clarification and uniformity of terminology should be a starting point, as Levin and Steele indicated.

5.8. Medical Assessment

Eventually 11 out of 28 healings presented were considered to be medically remarkable by the assessment team (Table 6). In 10 cases this was primarily associated with a highly unusual course of the disease: instantaneous healing experiences of serious diseases (Parkinson disease, Multiple Sclerosis, Anorexia Nervosa, Inflammatory Bowel Disease et al.) with gross reduction or complete disappearance of all symptoms. In one case there was a totally unexpected remission of acute leukemia in a terminally ill patient with major complications, which were considered to be incompatible with life. The assessment team could not explain this recovery. However, the relapse after one year did not comply with the requirement of a permanent cure (see Lambertini criteria under Methods).

A separate remark should be made about the assessment team’s evaluation of malignancies. Apart from the case of leukemia the team went through the data of three other patients with reported healing of a malignancy. In all of them there was a medical mode of treatment possibly explaining the recovery. e.g., it is only in rare instances that treatment with chemotherapy can be successful in carcinoma of the stomach (EV 24, Table 6). In malignancies it may therefore be very difficult to find unexplained healings, as the vast majority of them also have parallel medical treatments.

Eventually none of the healings was evaluated as unexplained.

Unexplained cures were assessed elsewhere in rare instances such as in Lourdes (), Rome (), and by (, ). At the medical desk in Lourdes less than 1% of reports received since 1972 was evaluated as being unexplained (). It is therefore understandable not to find such cases in our series of 83.

5.9. ‘Mismatches’ and ‘Matches’

An unexpected finding was the occurrence of repeated mismatches between lasting healing experiences with gross functional improvements on one hand and remaining abnormalities in objective medical investigations on the other (EV 2, 8, 9, 12, 14, 20, 23, all in Table 6). There is an interesting paradox here: in these instances ‘subjective’ data was better at reflecting the patient’s state rather than ‘objective’ investigations. We recently published two articles covering some of these cases (, ). In other cases (EV 3, 10, 11, 27, all in Table 6) we found matches as well: subjective recoveries were accompanied by measurable improvements.

The mismatches evoke a discussion of hierarchical views on medical evidence. In medicine there is a strong tendency for ‘objective’ investigations to prevail over ‘subjective’ data such as patients’ narratives, hetero anamnesis, and clinical experience (). Our cases considered here however, point us in a different direction where both ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ data should be taken seriously and interpreted within their context. A horizontal epistemology (i.e., mode of knowing) would therefore better fit our findings. The term horizontal implies that objective and subjective data are both valued in the assessment of the clinical outcome ().

Huber et al. evaluated a new dynamic concept of health (), addressing people as ‘more than their illness’, covering six dimensions: bodily and mental functions, spiritual dimension, quality of life, social participation, daily functioning. A qualitative study and a survey were held under 140 and 1938 participants respectively. ‘Patients considered all six dimensions as being almost equally important, thus preferring a broad concept of life, whereas physicians assessed health more narrowly and biomedically’. Is this part of the paradox we face?

Could it be that we are overlooking important aspects in medical practice by adopting a hierarchy in our assessment when valuing ‘objective’ data above data from other dimensions?

5.10. Follow-Up: Health Related and Socio-Religious Outcomes

Health-related long term outcomes were positive for most participants (Table 14 and Table 15). A large majority reported complete or partial healing when re-contacting them in 2019 and 2021, which was on average two and four years after registration in our study.

These positive results could be expected to some extent as this study was a retrospective one with many participants who had experienced healing 5 to 20 years previously or even more.

Socio-religious outcomes were favorable as well. Most of the participants experienced improved socio-religious quality of life, being more involved in various religious activities.

At the level of psycho-social outcomes there was a considerable group reporting positive effects: social activities, helping others, restoration of disrupted relationships (relief of bitterness), increased self-confidence. Not only did the healing improve the socio-religious quality of life, people tended to focus more on non-materialist values, starting or participating in social activities, willing to help others.

Lee, Poloma and Post noticed that there is a positive relationship between religious experiences and benevolent activities (): ‘An encounter with a divine energy that is profoundly loving and accepting beyond words, followed by a radical shift in which core values are turned upside down, resulting in insights that appear to rewire the person and their approach to life… It empowers a life of benevolence’.

A separate remark needs to be made concerning negative reactions from within churches and from Christians in general when participants were communicating their healing experience (Table 16). Seventeen of them mentioned this explicitly during follow up. Evidently it is not rare. Corlien Doodkorte, who had a healing experience from Parkinson’s disease (see also ), gave quite a few examples in her book (). It underlines the necessity that we should listen carefully to those having a healing experience without confronting them with our own opinions and it underlines the necessity for churches to develop a balanced view on healing and prayer.

5.11. A Pattern of a Healing Touch with a Spiritually Transformative Impact

In summary, a pattern of healings is emerging accompanied by sensory manifestations, with a strong and lasting transformative impact on life. Extrasensory perceptions such as visions, vivid dreams, a sense of presence were described as well. These healings were found to be medically remarkable in a number of instances. However, the same pattern was also found in a majority of the cases, which could not be labelled as medically remarkable.

It is now interesting to compare our data with those found in other qualitative studies. The conclusion of () was already mentioned above in Course of healing.

In the study of () in-depth interviews were conducted with 25 respondents with a healing experience related to prayer. They found similar sensory and extrasensory manifestations in a variety of settings and contexts, writing: ‘In analyzing the participants’ stories of what happened during their healing events, we found that these moments, in different ways, could be characterized as someone or something touching the lived body’. They also noticed that these powerful touches, ‘hitting the target of the participants’ burden’, had a transformative impact on people’s lives. Finally, they conclude: ‘Based on the stories of these 25 participants, we argue that the experienced healing events, which we have characterized as involving the sense of a powerful touch that is targeted, energetic, emotional and love-providing, can be hermeneutically conceptualized as re-inscriptions that affected the lived body and spurred renewed health and lived meaning’.

() did a qualitative study of HP. Twenty participants were interviewed: ‘Sixteen of the 20 participants felt as though they had experienced spiritual transformation through this prayer and healing experience; they were not the same people thereafter’.

It is fascinating that the above studies and ours all seem to point in the direction of a recurring pattern, moreover occurring in different countries and in different settings. Traces of the same pattern can also be found in our qualitative study by (). Further studies focusing on these findings will be very worthwhile. Is it indeed a recurring pattern? And what will be the relevance of it for churches and society as a whole? And for prayer practices specifically?

5.12. An Explanatory Framework

In this study we observed many healings with prominent non-medical aspects. Apparently there was a form of remarkableness apart from medical remarkability. Also, in some cases there were mismatches between functional and organic improvement while in others there were matches. Eventually we were unable to capture the observations within a biomedical model only. To do so we would require a broader explanatory framework.

When searching for non-biomedical explanations, alternative options can be considered. Unexplained subjective improvements may result from placebo effects. It was argued above that our findings regarding a lack of expectancy and instantaneity of healing, differ distinctly from these effects. A patient who trusts the doctor or a drug may benefit from placebo effects, but usually not in a surprising instantaneous way accompanied with lots of other sensory experiences. The same is true for recoveries in cases of Medically Unexplained Symptoms (MUS) as we indicated in another article (). Moreover, most of the participants in our study had well established diagnoses explaining signs and symptoms. Also, can these healings be considered as spontaneous remissions of serious chronic diseases? Although a lot is still unknown about the nature and the causality of spontaneous remissions, as Radin pointed out, one would expect the clinical course of recovery to be more gradual as well ().

Finally, one may suggest that our patients suffered from psychiatric problems such as somatization, factitious disorder or, even, malingering. But the psychiatrist in the assessment team did not find any indication to that effect. Nor did one of the supervisors and co-author, who is a psychiatrist as well (GG). This observation is also in line with the wide spectrum of diseases (Table 5) in which there was no over-representation of psychiatric or psychosomatic illness.

Beyond this, none of the above models can explain the transformative impact of the HP experiences which were documented. Clinically they were not ‘ordinary healings’, but life events with far-reaching consequences for the rest of life.

() and () positioned HP experiences in a holistic perspective. Biological, psychological, spiritual aspects are all relevant. Body-mind duality and a subjective-objective hierarchy are not helpful when trying to understand participants. Collecting the medical files, which we did initially, was insufficient, as we observed that experiential and existential data were as important.

Although a holistic approach is indicated when studying HP experiences, it is not enough when interpreting them. The manifestations of a ‘touch’ and the resulting ‘transformation’ exceed the holistic perspective, it seems as if something happens beyond the capacities of the persons themselves. Something which is not occurring from within the inside of an individual, but is rather sensed as an interference from outside. An ‘inscription’ from elsewhere. This was indeed invariably the interpretation of the participants, when they attributed their healing and all events surrounding it and after it, to God (Table 13).

Can theology be helpful here when articulating these HP experiences? It is a discipline studying relationships between humans and external dimensions such as a divinity. Biblical narratives relate many healing experiences (), especially by Jesus, with the same ‘ingredients’ of instantaneity and transformation. These narratives are also about radical changes in life, turning-points after prayer and encounters with God. The same is true for accounts throughout church history () and today, a pattern which has been highlighted above in Course of healing. There is indeed an analogy between the HP experiences we observed and healing narratives in the Bible and throughout church history. They are being interpreted as a ‘gift’ or an ‘act from God’. The word ‘charism’ is often used in the New Testament when referring to a ‘gift of grace’. (), a German New Testament scholar, defines a charism as an act of God’s Spirit in favor of the church or the world, working momentarily as a ‘generous and unmerited bestowal’. This would indeed articulate very well the experience of many of the participants, irrespective of religious or non-religious background.

But to some scientists shaking hands with theology is like shaking hands with other people during a pandemic. However, it can be very worthwhile to do so. Ian Barbour presented a famous typology, according to which the relationship between science and religion can be described in terms of conflict, independence, dialogue and integration (). Based upon our findings we would advocate a dialogue between them. The wisdom and narratives of religion and ancient civilizations and modern insights in science and clinical medicine may both be helpful when trying to understand HP experiences.

() conducted a cross-faith study of life-changing religious and spiritual experiences in the US. Such experiences were also encountered in other religious and non-religious settings. Our study was about HP experiences in Christian settings, although there was a group of participants who considered themselves not religious prior to the prayer involved. Future research may include studies of HP experiences in other backgrounds as well.

5.13. Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is its multidisciplinary approach combining medical and experiential data. The subsequent transdisciplinary analysis by different disciplines allows for tri-angulation, viewing the findings from different perspectives. The complexity of the subject requires that it is not approached as just a medical issue, nor as mainly theological, nor in terms of any other discipline solely. HP touches on several fields.

A major limitation relates to the group we studied: all participants experienced a healing which they related to prayer and they decided to report the event. Their self-interpretation determined who was included in the research sample. This is a subgroup of those who pray for healing, therefore the results cannot be extrapolated to all people praying for healing. However, it was our aim to study individuals with positive outcomes and to learn from their medical data and experiences.

We also realize that there can be negative experiences or downsides as well pertaining to HP. Prayer healing practices can be potentially damaging, e.g., if these practices interfere with medical treatment. They can also lead to negative psychological consequences if there is no cure and prospects about cure have been presented too favorably. We intentionally studied a specific group, while remaining aware of other possible effects as well.

6. Conclusions

We will now return to our three research questions.

Firstly, with regard to the medical and experiential findings a wide variety of illnesses were presented, there was no clear over-representation of particular disease categories.

A dominant pattern was found when studying the data: instantaneity and unexpectedness of healing accompanied by physical and emotional manifestations, and a sense of being ‘overwhelmed’ or ‘touched’. These healing experiences were transformative and life-changing. Orientation in life changed, with an increased focus on non-materialist aspects, such as benevolent activities. The healings were invariably interpreted as acts of God. Medically the pattern differed significantly from cures as ‘normally’ seen in medical practice.

The healings and positive socio-religious effects persisted in the majority of cases when followed up two and four years after enrolment in the study.

Secondly, no healings were evaluated as medically unexplained. However, eleven healings were considered to be medically remarkable. The remarkability concerned the unusual course of the disease in most cases. In particular, there were several examples of sudden cures of serious chronic diseases while the best possible prognosis would be one of gradual regression.

Thirdly, when looking for explanatory frameworks trying to understand the findings the research team found it increasingly difficult to capture the observations in biomedical terms. The same was true for psychiatric conditions, placebo effects and models of medically unexplained symptoms. The transformative impact seemed to exceed holistic frameworks as well. The healing experiences involving a divine touch with resulting life-changing impact may very well be articulated by theology and philosophy as an entrance to wisdom and the rich narratives of age-old traditions.

A fruitful dialogue between science and religion will be helpful when interpreting HP experiences (). We may come across an interface between them, or a ‘porosity’ as we have called it elsewhere (). Insights from medicine, biopsychosocial disciplines, theology and philosophy and good cooperation between them may all contribute to the dialogue.

Future studies will be important as well. Although HP attracts a lot of public interest the subject is understudied. The authors of this article believe that such research should preferably be transdisciplinary, case based and qualitative.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, all authors; software, D.K., E.B.; validation, all authors; formal analysis, all authors; investigation, D.K., E.B.; resources, all authors; data curation, D.K., E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, E.B., K.v.d.K., G.G., T.A.; visualization, D.K.; supervision, K.v.d.K., G.G., T.A.; project administration, D.K., E.B.; funding acquisition, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The qualitative part of this research, like the interviews by a senior researcher, was partially funded by Dimence group, Institute for Mental Health care, Zwolle, The Netherlands.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Amsterdam University Medical centre, VUmc, confirmed on 4 June 2015, that the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act does not apply to the study (reference no 2015.192).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from subjects involved in the study. The Privacy Desk of the VU university reported on 22 October 2015, that this study complies with the relevant privacy standards (VU2015-79).

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results can be obtained from the corresponding author: d.kruijthoff@amsterdamumc.nl or d.kruijthoff@solcon.nl. Address (home): Zevenhovenstraat 2, 2971AZ Bleskensgraaf, The Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the article are most grateful to the members of the medical assessment team for their invaluable contributions to the study: C.J.J. Avezaat, MD, PhD, emeritus Professor of Neurosurgery at Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; A.J.L.M. van Balkom, MD, PhD, Professor of Evidence-based Psychiatry; and P.C. Huijgens, emeritus Professor of Hematology; and M.A. Paul, MD, PhD, Thoracic Surgeon; and J.M. Zijlstra-Baalbergen, MD, PhD, Internist and Professor of Hematology, all from the Amsterdam University Medical Centres, location VUmc, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflct of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; or in the decision to publish the result.

References

- Abma, Tineke. 2020. Ethics work for good participatory action research, engaging in a commitment to epistemic justice. Beleidsonderzoek Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abma, Tineke A., and Robert E. Stake. 2014. Science of the Particular: An Advocacy of Naturalistic Case Study in Health Research. Qualitative Health Research 24: 1150–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anonym. 2011. Expliquez Moi: Les Miracles. En Complement du Guide Officiel des Sanctuaires de Lourdes. Lourdes: Imprimerie de la Grotte. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine St. n.d. The City of God. Book XXII Ch 8. Floyd: SMK Books.

- Austad, Anne, Marianne Rodriguez Nygaard, and Tormod Kleiven. 2020. Reinscribing the Lived Body: A Qualitative Study of Extraordinary Religious Healing Experiences in Norwegian Contexts. Religions 11: 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, Ian G. 2000. When Science Meets Religion. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Baumert, Norbert. 2001. Charisma-Taufe-Geisttaufe 1/2. Wurzburg: Echter Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bendien, Elena, Dirk J. Kruijthoff, Cornelis van der Kooi, Gerrit Glas, Tineke A. Abma, and Peter C. Huijgens. 2022. A Dutch study of remarkable recoveries after prayer: How to deal with uncertainties of explanation. Journal of Religion and Health. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Candy Gunther. 2012. Testing Prayer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 182–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Candy Gunther. 2015. Pentecostal Healing Prayer in an Age of Evidence-Based Medicine. Transformation 32: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Aguiar, Paulo Rogério Dalla Colletta, Tiago Pires Tatton-Ramos, and Letícia Oliveira Alminhana. 2017. Research on Intercessory Prayer: Theoretical and Methodological Considerations. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 1930–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doodkorte, Corlien. 2016. Geen Grappen God. Aalten: Stichting Vrij Zijn, pp. 118–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, St John. 1984. Lourdes cures and their medical assessment. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 77: 634–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffin, Jacalyn. 2007. The doctor was surprised; or, how to diagnose a miracle. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 81: 699–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffin, Jacalyn. 2009. Medical Miracles. Doctors, Saints and Healing in the Modern World. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duffin, Jacalyn. 2013. Medical Saints. Cosmas and Damian in a Postmodern World. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, Andrea W. M., Danielle J. P. Bartels, and Antoinette I. M. van Laarhoven. 2014. Placebo and Nocebo Effects in Itch and Pain. In Placebo. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Edited by Benedetti Fabrizio, Paul Enck, Elisa Frisaldi and Manfred Schedlowski. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finniss, Damien G., Ted J. Kaptchuk, Franklin Miller, and Fabrizio Benedetti. 2010. Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects. The Lancet 375: 686–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, Bernard, Esther M. Sternberg, and Elizabeth Fee. 2014. The Lourdes medical cures revisited. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 69: 135–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glas, Gerrit. 2019. Person-Centered Care in Psychiatry. Self-Relational, Contextual and Normative Pespectives. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Judith, and Nicki Thorogood. 2018. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London: Sage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, Ian A., Amy E. Hale, and Crystal L. Park. 2018. Life-Changing Religious and Spiritual Experiences: A Cross-Faith Comparison in the United States. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10: 334–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkenes, Emiel. 2009. De dokter wil wonderen gaan toetsen. Trouw, October 30. [Google Scholar]

- Helming, Mary Blaszko. 2011. Healing through prayer: A qualitative study. Holistic Nursing Practice 25: 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Machteld, Marja van Vliet, M. Giezenberg, B. Winkens, Y. Heerkens, P. C. Dagnelie, and J. A. Knottnerus. 2016. Towards a ‘patient-centred’ operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 6: e010091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, Karsten Juhl, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, and Peter C. Gøtzsche. 2009. Divine intervention? A Cochrane review on intercessory prayer gone beyond science and reason. Journal of Negative Results in Biomedicine 8: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Koelsch, Lori E. 2013. Reconceptualizing the member check interview. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12: 168–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruijthoff, Dirk J., Cornelis van der Kooi, Gerrit Glas, and Tineke A. Abma. 2017. Prayer Healing: A Case Study Research Protocol. Advances in Mind-Body Medicin 31: 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kruijthoff, Dirk J., Elena Bendien, Corlien Doodkorte, Cornelis van der Kooi, Gerrit Glas, and Tineke A. Abma. 2021. “My Body Does Not Fit in Your Medical Textbooks”: A Physically Turbulent Life With an Unexpected Recovery From Advanced Parkinson Disease After Prayer. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine 35: 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kruijthoff, Dirk J., Elena Bendien, Cornelis van der Kooi, Gerrit Glas, Tineke A. Abma, and Peter C. Huijgens. 2022a. Three cases of hearing impairment with surprising subjective improvements after prayer. What can we say when analyzing them? Explore 18: 475–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruijthoff, Dirk J., Elena Bendien, Cornelis van der Kooi, Gerrit Glas, and Tineke A. Abma. 2022b. Can you be cured if the doctor disagrees? A case study of 27 prayer healing reports evaluated by a medical assessment team in the Netherlands. Explore. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, Kathryn. 1992. I Believe in Miracles. Gainesville: Bridge-Logos. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, Kathryn. 1993. God Can Do It Again. Gainesville: Bridge-Logos. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, Kathryn. 1999. Nothing Is Impossible with God. Gainesville: Bridge-Logos. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Matthew T., Margaret M. Poloma, and Stephen G. Post. 2013. The Heart of Religion. Spiritual Empowerment, Benevolence, and the Experience of God’s Love. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Jeff. 2016. Prevalence and Religious Predictors of Healing Prayer Use in the USA: Findings from the Baylor Religion Survey. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1136–58, Erratum in Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeffrey S. 1996. How prayer heals: A theoretical model. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 2: 66–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levin, Jeff, and Lea Steele. 2005. The transcendent experience: Conceptual, theoretical, and epidemiologic perspectives. Explore 1: 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundmark, Mikael. 2010. When Mrs B Met Jesus during Radiotherapy A Single Case Study of a Christic Vision: Psychological Prerequisites and Functions and Considerations on Narrative Methodology. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 32: 27–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselko, Joanna, and Laura D. Kubzansky. 2006. Gender differences in religious practices, spiritual experiences and health: Results from the US General Social Survey. Social Science & Medicine 62: 2848–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, Anne M., David M. Eisenberg, Anna T. R. Legedza, Roger B. Davis, and Russell S. Phillips. 2004. Prayer for health concerns: Results of a national survey on prevalence and patterns of use. Archives of Internal Medicine 164: 858–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. 130–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nikchevich, Vesna, and Ana Smylyanich. 2017. Life and Miracles of Saint Basil of Ostrog (with Brief History of the Ostrog Monastery). Cetinje: Svetigora Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ouweneel, Willem Johannes. 2003. Geneest de Zieken! Over de Bijbelse Leer van Ziekte, Genezing en Bevrijding. Vaassen: Uitg Miedema. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Mart Jan. 1997. Vergeving en Genezing. Ziekenzalving in de Christelijke Gemeente. Zoetermeer: Uitgeverij Boekencentrum. [Google Scholar]

- Poloma, Margaret M., and Matthew T. Lee. 2011. From Prayer Activities to Receptive Prayer: Godly Love and The Knowledge that Surpasses Understanding. Journal of Psychology and Theology 39: 143–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, Dean. 2021. The future of spontaneous remissions. Explore (NY) 17: 483–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Leanne, Irshad Ahmed, and Andrew Davison. 2009. Intercessory prayer for the alleviation of ill health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009: CD000368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romez, Clarissa, David Zaritzky, and Joshua W. Brown. 2019. Case Report of gastroparesis healing: 16 years of a chronic syndrome resolved after proximal intercessory prayer. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 43: 289–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romez, Clarissa, Kenn Freedman, David Zaritzky, and Joshua W. Brown. 2021. Case report of instantaneous resolution of juvenile macular degeneration blindness after proximal intercessory prayer. Explore 17: 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roukema, Riemer. 1989. Van wonderen gesproken. Bulletin voor Charismatische Theologie 24: 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, Michel-Marie. 2000. The Cure of Vittorio Micheli. Sarcoma of the Pelvis. Lourdes: Imprimerie de la Grotte. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, Richard P., and Rajasekhar Ramakrishnan. 2006. Science, medicine, and intercessory prayer. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 49: 504–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Jonathan A. 2011. Evaluating the contribution of interpretative phenomenological analysis: A reply to the commentaries and further development of criteria. Health Psychology Review 5: 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Derek D. 2006. Just another drug? A philosophical assessment of randomised controlled studies on intercessory prayer. Journal of Medical Ethics 32: 487–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Saane, Joke. 2008. Gebedsgenezing. Boerenbedrog of Serieus Alternatief? Kampen: Ten Have. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Jean. 1999. Postmodern Nursing and Beyond. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).